LIFE

OF

ERASMUS DARWIN

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY.

ERASMUS DARWIN.

FROM A PICTURE BY WRIGHT OF DERBY.

ERASMUS DARWIN.

BY ERNST KRAUSE.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY W.S. DALLAS.

WITH A PRELIMINARY NOTICE

BY CHARLES DARWIN.

PORTRAIT AND WOODCUTS.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMERLE STREET.

1879.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

PREFACE.

___

IN the February number, 1879, of a well-known German scientific journal, 'Kosmos,' Dr. Ernst Krause published a sketch of the life of Erasmus Darwin, the author of the 'Zoonomia,' 'Botanic Garden,' and other works. This article bears the title of a 'Contribution to the history of the Descent-Theory;' and Dr. Krause has kindly allowed my brother Erasmus and myself to have a translation made of it for publication in this country.*

As I have private materials for adding to the knowledge of Erasmus Darwin's character, I have written a preliminary notice. These materials consist of a large collection of letters written by him; of his common-place book in folio, in the possession of his grandson Reginald Darwin; of some notes made shortly

* Mr. Dallas has undertaken the translation, and his scientific reputation, together with his knowledge of German, is a guarantee for its accuracy.

after his death, by my father, Dr. Robert Darwin, together with what little I can clearly remember that my father said about him; also some statements by his daughter, Violetta Darwin, afterwards Mrs. Tertius Galton, written down at the time by her daughters; and various short published notices. To these must be added the 'Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin,' by Miss Seward, which appeared in 1804; and a lecture by Dr. Dowson on "Erasmus Darwin, Philosopher, Poet, and Physician," published in 1861, which contains many useful references and remarks.*

* Since the publication of Dr. Krause's article, Mr. Butler's work, 'Evolution, Old and New, 1879' has appeared, and this includes an account of Dr. Darwin's life, compiled from the two books just mentioned, and of his views on evolution.

PRELIMINARY NOTICE.

___

ERASMUS DARWIN was descended from a Lincolnshire family, and the first of his ancestors of whom we know anything was William Darwin, who possessed a small estate at Cleatham.* He was also yeoman of the armoury of Greenwich to James I. and Charles I. This office was probably almost a sinecure, and certainly of very small value. He died in 1644, and we have reason to believe from gout. It is, therefore, probable that Erasmus, as well as many other members of the family, inherited from this William, or some of his predecessors, their strong tendency to gout; and it was an early attack of gout which made Erasmus a vehement advocate for temperance throughout his whole life.

* The greater part of the estate of Cleatham was sold in 1760. A cottage with thick walls, some fish-ponds and old trees, alone-show where the "Old Hall" once stood. A field is still called the "Darwin Charity," from being subject to a charge, made by the second Mrs. Darwin, for buying gowns for four old widows every year.

B

The second William Darwin (born 1620) served as Captain-Lieutenant in Sir W. Pelham's troop of horse, and fought for the king. His estate was sequestrated by the Parliament, but he was afterwards pardoned on payment of a heavy fine. In a petition to Charles II. he speaks of his almost utter ruin from having adhered to the royal cause, and it appears that he had become a barrister. This circumstance probably led to his marrying the daughter of Erasmus Earle, Serjeant-at-law; and hence Erasmus Darwin derived his Christian name.

The eldest son from this marriage, William (born 1655), married the heiress of Robert Waring, of Wilsford, in the county of Nottingham. This lady also inherited the manor of Elston, which has remained ever since in the family.

This third William Darwin had two sons —William, and Robert who was educated as a barrister, and who was the father of Erasmus. I suppose that the Cleatham and the Waring properties were left to William, who seems to have followed no profession, and the Elston estate to Robert; for when

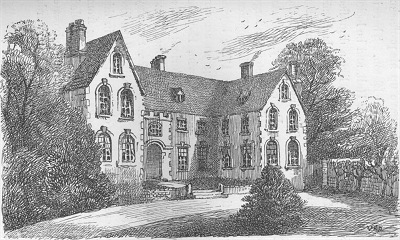

Elston Hall (where Erasmus Darwin was born), as it existed before 1754.

B2

the latter married, he gave up his profession and lived ever afterwards at Elston. There is a portrait of him at Elston Hall, and he looks, with his great wig and bands, like a dignified doctor of divinity. He seems to have had some taste for science, for he was an early member of the well-known Spalding Club; and the celebrated antiquary, Dr. Stukeley, in 'An account of the almost entire Sceleton of a large animal,' &c., published in the 'Philosophical Transactions,' April and May 1719, begins his paper as follows:—"Having an account from my friend, Robert Darwin, Esq., of Lincoln's Inn, a Person of Curiosity, of a human Sceleton impressed in Stone, found lately by the Rector of Elston," &c. Stukeley then speaks of it as a great rarity, "the like whereof has not been observed before in this island, to my knowledge." Judging from a sort of litany written by Robert, and handed down in the family, he was a strong advocate of temperance, which his son ever afterwards so strongly advocated:—

From a morning that doth shine,

From a boy that drinketh wine,

From a wife that talketh Latine,

Good Lord deliver me.

It is suspected that the third line may be accounted for by his wife, the mother of Erasmus, having been a very learned lady.

The eldest son of Robert, christened Robert Waring, succeeded to the estate of Elston, and died there at the age of ninety-two, a bachelor. He had a strong taste for poetry, like his youngest brother Erasmus. Robert also cultivated botany, and when an oldish man, he published his 'Principia Botanica.' This book in MS. was beautifully written, and my father declared that he believed it was published because his old uncle could not endure that such fine calligraphy should be wasted. But this was hardly just, as the work contains many curious notes on biology—a subject wholly neglected in England in the last century. The public, moreover, appreciated the book, as the copy in my possession is the third edition.

Of the second son, William Alvey, I know nothing. A third son, John, became the rector of Elston, the living being in the gift of the family. The fourth son, and the youngest of the children, was Erasmus, the subject of the present memoir, who was born on the 12th Dec. 1731, at Elston Hall.

His elder brother, Robert, states, in a letter to my father (May 19, 1802), that Erasmus "was always fond of poetry. He was also always fond of mechanicks. I remember him when very young making an ingenious alarum for his watch (clock?); he used also to show little experiments in electricity with a rude apparatus he then invented with a bottle." The same tastes, therefore, appeared very early in life which prevailed to the day of his death. "He had always a dislike to much exercise and rural diversions, and it was with great difficulty that we could ever persuade him to accompany us."

When ten years old (1741), he was sent to Chesterfield School, where he remained for nine years. His sister, Susannah, wrote to him at school in 1748, and I give part of the letter as a curiosity. She was then a young lady between eighteen and nineteen years old. She died unmarried, and her nephew, Dr. Robert Darwin (my father), who was deeply attached to her, always spoke of her as the very pattern of an old lady, so nice looking, so gentle, kind, and charitable, and passionately fond of flowers. The first part

of her letter consists of gossip and family news, and is not worth giving.

SUSANNAH DARWIN to ERASMUS.

DEAR BROTHER,

I come now to ye chief design of my Letter, and that is to acquaint you with my Abstinence this Lent, which you will find on ye other side, it being a strict account of ye first 5 days, and all ye rest has been conformable thereto; I shall be glad to hear from you wth an account of your temperance this lent, wch I expect far exceeds mine. As soon as we kill our hog I intend to take part thereof with ye Family, for I'm informed by a learned Divine yt Hogs Flesh is Fish, and has been so ever since ye Devil entered into ym and they ran into ye Sea; if you and the rest of the Casuists in your neighbourhood are of ye same oppinion, it will be a greater satisfaction to me, in resolving so knotty a point of Conscience. This being all at present I conclude with all our dues to you and Bror.

Your affectionate sister,

S. DARWIN.

A DIARY IN LENT.

ELSTON, Feb. 20, 1748.

Febry 8 Wednesday Morning a little before seven I got up; said my Prayers; worked till eight;

yn took a walk, came in again and eate a farthing Loaf, yn dress'd me, red a Chapter in ye Bible, and spun till One, yn dined temperately viz: on Puddin, Bread and Cheese; spun again till Fore, took a walk, yn spun till half an hour past Five; eat an Apple, Chattered round ye Fire; and at Seven a little boyl'd Milk; and yn (takeing my leave of Cards ye night before) spun till nine; drank a Glass of Wine for ye Stomack sake; and at Ten retired into my Chamber to Prayers; drew up my Clock and set my Larum betwixt Six and Seven.

Thursday call'd up to Prayers, by my Larum; spun till Eight, collected ye Hens' Eggs; breakfasted on Oat Cake, and Balm Tea; yn dress'd and spun till One, Pease Porrage, Pottatoes and Apple Pye; yn turned over a few pages in Scribelerus; eat an Apple and got to my work; at Seven got Apple Pye and Milk, half an hour after eight red in ye Tatlar and at Ten withdrew to Prayers; slept sound; rose before Seven; eat a Pear; breakfast a quarter past Eight; fed ye Cats, went to Church; at One Pease Porrage, Puddin, Bread and Cheese; Fore Mrs. Chappells came, Five drank Tea; Six eat half an Apple; Seven a Porrenge of Boyl'd Milk; red in ye Tatlar; at Eight a Glass of Punch; filled up ye vacancies of ye day with work as before.

Saturday Clock being too slow lay rather longar yn usal; said my Prayers; and breakfasted at Eight; at One broth, Pudding, Brocoli and Eggs, and

Apple Pye; at Five an Apple; seven Apple Pye, Bread and Butter; at Nine a Glass of Wine; at Ten Prayers.

Sunday breakfast at Eight; at Ten went to ye Chappell; 12 Dumplin, red Herring, Bread and Cheese; two to ye Church; read a Lent Sermon at Six; and at Seven Appel Pye Bread and Cheese.

Excuse hast, being very cold.

ERASMUS, AETAT. 16, to SUSANNAH DARWIN.

DEAR SISTER,

I receiv'd yours about a fortnight after ye date yt I must begg to be excused for not answering it sooner: besides I have some substantial Reasons, as having a mind to see Lent almost expired, before I would vouch for my Abstinence throughout ye whole: and not having had a convenient oppertunity to consult a Synod of my learned friends about your ingenious Conscience, and I must inform you we unanimously agree in ye Opinion of ye Learned Divine you mention, that Swine may indeed be fish but then they are a devillish sort of fish; and we can prove from ye same Authority that all fish is flesh whence we affirm Porck not only to be flesh but a devillish Sort of flesh; and I would advise you for Conscience sake altogether to abstain from tasting it; as I can assure You I have done, tho' roast Pork has come to Table several Times; and for my own part

have lived upon Puding, milk, and vegetables all this Lent; but don't mistake me, I don't mean I have not touch'd roast beef, mutton, veal, goose, fowl, &c. for what are all these? All flesh is grass! Was I to give you a journal of a Week, it would be stuft so full of Greek and Latin as translation Verses, themes, annotation Exercise and ye like, it would not only be very tedious and insipid but perfectly unintelligible to any but Scholboys.

I fancy you forgot in Yours to inform me yt your Cheek was quite settled by your Temperance, but however I can easily suppose it. For ye temperate enjoy an ever-blooming Health free from all ye Infections and disorders luxurious mortals are subject to, the whimsical Tribe of Phisitians cheated of their fees may sit down in penury and Want, they may curse mankind and imprecate the Gods and call down ye parent of all Deseases, luxury, to infest Mankind, luxury more distructive than ye Sharpest Famine; tho' all the Distempers that ever Satan inflicted upon Job hover over ye intemperate; they would play harmless round our Heads, nor dare to touch a single Hair. We should not meet those pale thin and haggard countenances which every day present themselves to us. No doubt men would still live their Hunderd, and Methusalem would lose his Character; fever banished from our Streets, limping Gout would fly ye land, and Sedentary Stone would vanish into oblivion and death himself be slain.

I could for ever rail against Luxury, and for ever panegyrize upon abstinence, had I not already encroach'd too far upon your Patience, but it being Lent the exercise of ye Christian virtue may not be amiss, so I shall proceed a little furder—

[The remainder of the letter is hardly legible or intelligible, with no signature.]

P.S.—Excuse Hast, supper being called, very Hungry.

Judging from two letters—the first written in 1749, to one of the under-masters during the holidays, and the other to the headmaster, shortly after he went to Cambridge, in 1750—he seems to have felt a degree of respect, gratitude, and affection for the several masters unusual in a schoolboy. Both these letters were accompanied by an inevitable copy of verses, those addressed to the head-master being of considerable length, and in imitation of the 5th Satire of Persius. His two elder brothers accompanied him to St. John's College, Cambridge; and this seems to have been a severe strain on their father's income. They appear, in consequence, to have been thrifty and honourably economi-

cal; so much so that they mended their own clothes; and, many years afterwards, Erasmus boasted to his second wife that, if she cut the heel out of a stocking, he would put a new one in without missing a stitch. He won the Exeter Scholarship at St. John's, which was worth only £16 per annum. No doubt he studied the classics whilst at Cambridge, for he did so to the end of his life, as shown by the many quotations in his latest work, 'The Temple of Nature.' He must also have studied mathematics to a certain extent, for, when he took his Bachelor of Arts degree, in 1754, he was at the head of the Junior Optimes. Nor did he neglect medicine; and he left Cambridge during one term to attend Hunter's lectures in London. As a matter of course, he wrote poetry whilst at Cambridge, and a poem on 'The Death of Prince Frederick,' in 1751, was published many years afterwards, in 1795, in the European Magazine.

In the autumn of 1754 he went to Edinburgh to study medicine, and while there, seems to have been as rigidly economical as at Cambridge; for amongst his papers there is a receipt for his board from July 13th to October

13th, amounting to only £6 125. Mr. Keir, afterwards a distinguished chemist, was at Edinburgh with him, and after his death wrote to my father (May 12th, 1802): "The classical and literary attainments which he had acquired at Cambridge gave him, when he came to Edinburgh, together with his poetical talents and ready wit, a distinguished superiority among the students there. Every one of the above-mentioned Professors [whose lectures he attended], excepting Dr. Whytt, had been a pupil of the celebrated Boerhaave, whose doctrines were implicitly adopted. It would be curious to know (but he alone could have told us) the progress of your father's mind from the narrow Boerhaavian system, in which man was considered as an hydraulic machine whose pipes were filled with fluid susceptible of chemical fermentations, while the pipes themselves were liable to stoppages or obstructions (to which obstructions and fermentations all diseases were imputed), to the more enlarged consideration of man as a living being, which affects the phenomena of health and disease more than his merely

mechanical and chemical properties. It is true that about the same time, Dr. Cullen and other physicians began to throw off the Boerhaavian yoke; but from the minute observation which Dr. Darwin has given of the laws of association, habits and phenomena of animal life, it is manifest that his system is the result of the operation of his own mind."

The only other record of his life in Edinburgh which I possess is a letter to his friend Dr. Okes, of Exeter,* written shortly after the death of his father (1754), when he was twenty-three years old. It shows his sceptical frame of mind whilst he was quite a young man.

ERASMUS DARWIN to DR. OKES.

"Yesterday's post brought me the disagreeable news of my father's departure out of this sinful world.

"He was a man of more sense than learning; of very great industry in the law, even after he had no business, nor expectation of any. He was frugal, but not covetous; very tender to his children, but

* Published by one of his descendants in the 'Gentleman's Magazine,' Oct. 3808, vol. Ixxviii. pt. ii. p. 869.

Still kept them at an awful kind of distance. He passed through this life with honesty and industry, and brought up seven healthy children to follow his example.

"He was 72 years old, and died the 20th of this current November 1754. 'Blessed are they that die in the Lord.'

"That there exists a superior ENS ENTTUM, which formed these wonderful creatures, is a mathematical demonstration. That HE influences things by a particular providence, is not so evident. The probability, according to my notion, is against it, since general laws seem sufficient for that end. Shall we say no particular providence is necessary to roll this Planet round the Sun, and yet affirm it necessary in turning up cinque and quatorze, while shaking a box of dies? or giving each his daily bread? The light of Nature affords us not a single argument for a future state; this is the only one, that it is possible with God, since He who made us out of nothing can surely re-create us; and that He will do this is what we humbly hope. I like the Duke of Buckingham's epitaph—'Pro Kege sœpe, pro Bepublicâ semper, dubius, non improbus vixi; incertus, seel inturbatus morior. Christum advenero, Deo confido benevolent! et omnipotenti, Ens Entiuru miserere mei!'

"ERASMUS DARWIN."

The expression "disagreeable news," ap-

plied to his father's death, sounds very odd to our ears, but he evidently used this word where we should say "painful." For, in a feeling letter to Josiah Wedgwood, the famous potter, written a quarter of a century afterwards (Nov. 29th, 1780), about the death of their common friend Bentley, in which he alludes to the death of his own son, he says nothing but exertion will dispossess "the disagreeable ideas of our loss."

In 1755 he returned to Cambridge, and took his Bachelor of Medicine degree. He then again went to Edinburgh, and early in Sept. 1756, settled as a physician in Nottingham. Here, however, he remained for only two or three months, as he got no patients. Whilst in Nottingham he wrote several letters, some in Latin and some in English, to his friend, the son of the famous German philosopher, Reimarus.* Mechanics and medicine were the bonds of union between them. Erasmus also dedicated a poem to young Reimarus, on his taking his degree at Leyden

* I am much indebted to a son of Dr. Sieveking, who brought to England the original letters preserved by the descendants of Reimarus, for permitting me to have them photographed.

in 1754. Various subjects were discussed between them, including the wildest speculations by Erasmus on the resemblance between the action of the human soul and that of electricity, but the letters are not worth publishing. In one of them he says: "I believe I forgot to tell how Dr. Hill makes his 'Herbal' (a formerly well-known book). He has got some wooden plates from some old herbal, and the man that cleans them cuts out one branch of every one of them, or adds one branch or leaf, to disguise them. This I have from my friend Mr.

"G———y, watch-maker, to whom this print-mender told it, adding, 'I make plants now every day that God never dreamt of.' "It also appears from one of his letters to Reimarus, that Erasmus corresponded at this time about short-hand writing with Gurney, the author of a well-known book on this subject. Whilst still young he filled six volumes with short-hand notes, and continued to make use of the art for some time.

Several of the letters to Reimarus relate to a case in which Dr. Darwin appears to have been much interested. He sent or helped to

send a working man to a London surgeon, Mr. D., for a serious operation. Reimarus and Dr. Darwin appear to have had some misunderstanding with the surgeon, expecting that he would perform, the operation gratuitously. Dr. Darwin writes to Reimarus: "I am very sorry to hear that D. took six guineas from the poor young man. He has nothing but what hard labour gives him; is much distressed by this thing costing him near £30 in all, since the house where he lay cheated him much. ... When he returns I shall send him two guineas. I beg you would not mention to my brother that I send this to him. Why his brother should not be told of this act of charity it is difficult to conjecture. From two other letters it appears that Dr. Darwin wrote anonymously to his friend the surgeon, complaining of his charge; and that when suspected of this discreditable act he did not own the authorship of the letter. He wrote to Reimarus (Nottingham Sept. 9th, 1756): "You say I am suspected to be the Author of it (i.e. the anonymous letter), and next to me some malicious per-

son somewhere else, and that I am desired as I am a gentleman to declare concerning it. First, then, as I am upon Honour, I must not conceal that I am glad there are Persons who will revenge Faults the Law can not take hold off: and I hope Mr. D. will not be affronted at this Declaration; since you say he did not know the Distress of the Man. Secondly, as another Person is suspected, I will not say whether I am the Author or not, since I don't think the Author merits Punishment, for informing Mr. D. of a Mistake. You call the Letter a threatening Letter, and afterwards say the Author pretends to be a Friend to Mr. D. This, though you give me several particulars of it, is a Contradiction I don't understand." In a P.S. he adds that Reimarus might show the letter to Mr. D. The anonymous letter answered its purpose, for the surgeon returned four guineas, and Dr. Darwin thought it probable that he would ultimately return the other two guineas.

In November 1756, Erasmus settled in Lichfield, and now his life may be said to

c 2

have begun in earnest; for it was here, and in or near Derby, to which place he removed in 1781, that he published all his works. Owing to two or three very successful cases, he soon got into some practice at Lichfield as a physician, when twenty-five years old. A year afterwards (Dec. 1757) he married Miss Mary Howard, aged 17-18 years, who, judging from all that I have heard of her, and from some of her letters, must have been a superior and charming woman. She died after a long and suffering illness in 1770. They seem to have lived together most happily during the thirteen years of their married life, and she was tenderly nursed by her husband during her last illness. Miss Seward gives,* on secondhand authority, a long speech of hers, ending with the words, "he has prolonged my days, and he has blessed them." This is probably true, but everything which Miss Seward says must be received with caution; and it is scarcely possible that a speech of such length could have been reported with any accuracy.

The following letter was written by

* 'Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin,' 1801, pp. 11-14.

Erasmus four days before his marriage with Miss Howard.

ERASMUS DARWIN to MARY HOWARD.

DEAR POLLY, DARLASTON, Dec. 24, 1757.

As I was turning over some old mouldy volumes, that were laid upon a Shelf in a Closet of my Bed-chamber; one I found, after blowing the Dust from it with a Pair of Bellows, to be a Receipt Book, formerly, no doubt, belonging to some good old Lady of the Family. The Title Page (so much of it as the Rats had left) told us it was "a Bouk off verry monny muckle vallyed Receipts bouth in Kookery and Physicks." Upon one Page was "To make Pye-Crust," — in another "To make Wall-Crust,"— "To make Tarts,"— and at length "To make Love." "This Receipt," says I, "must be curious, I'll send it to Miss Howard next Post, let the way of making it be what it will." — Thus it is "To make Love. Take of Sweet- William and of Rose-Mary, of each as much as is sufficient. To the former of these add of Honesty and Herb-of-grace; and to the latter of Eye-bright and Motherwort of each a large handful: mix them separately, and then, chopping them altogether, add one Plumb, two sprigs of Heart's Ease and a little Tyme. And it makes a most excellent dish, probatum est. Some put in Rue, and Cuckold-Pint, and Heart-Chokes,

and Coxcome, and Violents; But these spoil the flavour of it entirely, and I even disprove of Sallery which some good Cooks order to be mix'd with it. I have frequently seen it toss'd up with all these at the Tables of the Great, where no Body would eat of it, the very appearance was so disagreable."

Then, follow'd "Another Receipt to make Love," which began "Take two Sheep's Hearts, pierce them many times through with a Scewer to make them Tender, lay them upon a quick Fire, and then taking one Handful———" here Time with his long Teeth had gnattered away the remainder of this Leaf. At the Top of the next Page, begins "To make an honest Man." "This is no new dish to me," says I, "besides it is now quite old Fashioned; I won't read it." Then follow'd "To make a good Wife." "Pshaw," continued I, "an acquaintance of mine, a young Lady of Lichfield, knows how to make this Dish better than any other Person in the World, and she has promised to treat me with it sometime," and thus in a Pett threw doun the Book, and would not read any more at that Time. If I should open it again tomorrow, whatever curious and useful receipts I shall meet with, my dear Polly may expect an account of them in another Letter.

I have the Pleasure of your last Letter, am glad to hear thy cold is gone, but do not see why it should keep you from the concert, because it was gone. We drink your Health every day here, by

the Name of Dulciriea del Toboso, and I told Mrs. Jervis and Miss Jervis that we were to have been married yesterday, about which they teased me all the Evening. I heard nothing of Miss Fletcher's Fever before. I will certainly be with Thee on Wednesday evening, the Writings are at my House, and may be dispatched that night, and if a License takes up any Time (for I know nothing at all about these Things) I should be glad if Mr. Howard would order one, and by this means, dear Polly, we may have the Ceremony over next morning at eight o'clock, before any Body in Lichfield can know almost of my being come Home. If a License is to be had the Day before, I could wish it may be put off till late in the Evening, as the Voice of Fame makes such quick Dispatch with any News in so small a Place as Lichfield.—I think this is much the best scheme, for to stay a few Days after my Return could serve no Purpose, it would only make us more watch'd and teazed by the Eye and Tongue of Impertinence.—I shall by this Post apprize my Sister to be ready, and have the House clean, and I wish you would give her Instructions about any trivial affairs, that I cannot recollect, such as a cake you mentioned, and tell her the Person of whom, and the Time when it must be made, &c. I'll desire her to wait upon you for this Purpose. Perhaps Miss Nelly White need not know the precise Time till the Night before, but this as you please, as I (illegible). You could rely upon her Secrecy, and

it's a Trifle, if any Body should know. Matrimony, my dear Girl, is undoubtedly a serious affair, (if any Thing be such) because it is an affair for Life: But, as we have deliberately determin'd, do not let us be frighted about this Change of Life; or however, not let any breathing Creature perceive that we have either Fears or Pleasures upon this Occasion: as I am certainly convinced, that the best of Confidants (tho' experienced on a thousand other Occasions) could as easily hold a burning cinder in their Mouth as anything the least ridiculous about a new married couple! I have ordered the Writings to be sent to Mr. Howard that he may peruse and fill up the blanks at his Leizure, as it wilt (I foresee) be dark night before I get to Lichfield on Wednesday. Mrs. Jervis and Miss desire their Com pi. to you, and often say how glad she shall be to see you for a few Days at any Time. I shall be glad, Polly, if thou hast Time on Sunday night, if thou wilt favour me with a few Lines by the return of the Post, to tell me how Thou doest, &c.—My Compl. wait on Mr. Howard if He be returned.—My Sister will wait upon you, and I hope, Polly, Thou wilt make no Scruple of giving her Orders about whatever you chuse, or think necessary. I told her Nelly White is to be Bride-Maid. Happiness attend Thee! adieu

from, my dear Girl,

thy sincere Friend,

E. DARWIN.

P.S.—Nothing about death in this Letter, Polly.

It has been said that he soon got into practice at Lichfield, and I have found the following memorandum of his profits in his own handwriting:—

The profits of my business amounted

|

£ |

s. |

d. |

||||

|

From Nov. 12, |

1756 |

to Jan. 1, |

1757 |

18 |

7 |

6 |

|

Jan. |

1757 |

" |

1758 |

192 |

10 |

6 |

|

" |

1758 |

" |

1759 |

305 |

2 |

0 |

|

" |

1759 |

" |

1760 |

469 |

4 |

0 |

|

" |

1760 |

" |

1761 |

544 |

2 |

0 |

|

" |

1761 |

" |

1762 |

669 |

18 |

0 |

|

" |

1762 |

" |

1763 |

726 |

0 |

0 |

|

From Jan. 12, |

1763 |

to Jan. 1 |

1764 |

639 |

13 |

0 |

|

" |

1764 |

" |

1765 |

750 |

13 |

0 |

|

" |

1765 |

" |

1766 |

800 |

1 |

4 |

|

" |

1766 |

" |

1767 |

748 |

5 |

6 |

|

" |

1767 |

" |

1768 |

847 |

3 |

0 |

|

" |

1768 |

" |

1769 |

775 |

11 |

6 |

|

" |

1769 |

" |

1770 |

? |

||

|

" |

1770 |

" |

1771 |

956 |

17 |

6 |

|

" |

1771 |

" |

1772 |

1064 |

7 |

6 |

|

" |

1772 |

" |

1773 |

1025 |

3 |

0 |

Later in life he gave up the good habit of keeping accurate accounts, for in 1799 he wrote to my father that he had been much perplexed what return to make to the commissioners (of income tax?), as "I kept no book, but believed my business to be £1000 a year, and de-

duct £200 for travelling expenses and chaise hire, and £200 for a livery-servant, four horses and a day labourer." Subsequently he informed my father that the commissioners had accepted this estimate. A century ago an income of £1000 would probably be equal to one of £2000 at the present time; but I am greatly surprised that his profits were not larger. All his friends constantly refer to his long and frequent journeys, for his practice lay chiefly amongst the upper classes of society. When he went to live at the Priory, he remarked to my father in a letter that five or six additional miles would make little difference in the fatigue of his journeys. In 1781, eleven years after the death of his first wife, he married the widow of Colonel Ohandos Pole, of Radburn Hall. He had become acquainted with her in the Spring of 1778, when she had come to Lichfield in order that he might attend her children professionally. It is evident from the many MS. verses addressed to her before their marriage, that Dr. Darwin was passionately attached to her, even during the lifetime of her husband, who died in 1780.

These verses are somewhat less artificial than his published ones. On his second marriage he left Lichfield, and after living two years at Radburn Hall, he removed into the town of Derby, and ultimately to Breadsall Priory, a few miles from the town, where he died in 1802.

There is little to relate about his life at either Lichfield or Derby, and, as I am not attempting a connected narrative, I will here give such impressions as I have formed of his intellect and character, and a few of his letters which are either interesting in themselves, or which throw light upon what he thought and felt.

His correspondence with many distinguished men was large; but most of the letters which I possess or have seen are uninteresting, and not worth publication. Medicine and mechanics alone roused him to write with any interest. He occasionally corresponded with Rousseau, with whom he became acquainted in an odd manner, but none of their letters have been preserved. Rousseau was living in 1766 at Mr. Davenport's house, Wootton Hall, and used to

spend much of his time in the well-known cave upon the terrace in melancholy contemplation." He disliked being interrupted, so Dr. Darwin, who was then a stranger to him, sauntered by the cave, and minutely examined a plant growing in front of it. This drew forth Rousseau, who was interested in botany, and they conversed together, and afterwards corresponded during several years. I find a letter written in February 1767 on a singular subject. A gentleman had consulted him about the body of an infant which had apparently been murdered. It was believed to be the illegitimate child of a lady, and to have been murdered by its mother. He kept a copy of this letter, without any address. Omitting all medical details it runs as follows:—

DEAR SIR, LICHFIELD, Feb. 7, 1767.

I am sorry you should think it necessary to make any excuse for a Letter I this morning received from you. The Cause of Humanity needs no Apology to me.

* * * * * *

The Women that have committed this most unnatural crime, are real objects of our greatest

Pity; their education has produced in them so much Modesty, or sense of Shame, that this artificial Passion overturns the very instincts of Nature!— what Struggles must there be in their minds, what agonies!—at a Time when, after the Pains of Parturition, Nature has designed them the sweet Consolation of giving Suck to a little helpless Babe, that depends on them for its hourly existence!—Hence the cause of this most horrid crime is an excess of what is really a Virtue, of the Sense of Shame, or Modesty. Such is the Condition of human Nature! I have carefully avoided the use of scientific terms in this Letter that you may make any use of it you may think proper; and shall only add that I am veryly convinced of the Truth of every part of it. and am, Dear Sir,

Your affectionate friend and servant, ERASMUS DARWIN.

There is, perhaps, no safer test of a man's real character than that of his long continued friendship with good and able men. Now, Mr. Edgeworth, the father of Maria Edge-worth, the authoress, asserts,* after mentioning the names of Keir, Day, Small, Bolton, Watt, Wedgwood, and Darwin, that "their mutual intimacy has never been broken

* 'Memoirs of E. L. Edgeworth,' 2nd ed. vol. i. p. 181.

except by death." To these names, those of Edgeworth himself and of the Galtons may he added. The correspondence in my possession shows the truth of the above assertion. Mr. Day was a most eccentric character, whose life has been sketched by Miss Seward: he named Erasmus Darwin "as one of the three friends from whom he had met with constant kindness; "* and Dr. Darwin, in a letter to my father, says: "I much lament the death of Mr. Day. The loss of one's friends is one great evil of growing old. He was dear to me by many names (multis mihi nominibus charus), as friend, philosopher, scholar, and honest man."

I give below two of his letters to Josiah Wedgwood.

ERASMUS DARWIN to JOSIAH WEDGWOOD.

DEAR WEDGWOOD, LICHFIELD, Sept. 30, 1772.

I did not return soon enough out of Derbyshire to answer your letter by yesterday's Post. Your second letter gave me great consolation about Mrs. Wedgewood, but gave me in most sincere grief

* 'Memoirs of R. L. Edgeworth,' 2nd ed. vol. ii. p. 113.

about Mr. Brindley, whom I have always esteemed to be a great genius, and whose loss is truly a public one. I don't believe he has left his equal. I think the various Navigations should erect him a monument in Westminster Abbey, and hope you will at the proper time give them this hint.

Mr. Stanier sent me no account of him, except of his death, though I so much desired it, since if I had understood that he got worse, nothing should have hindered me from seeing him again. If Mr. Henshaw took any Journal of his illness or other circumstances after I saw him, I wish you would ask him for it and enclose it to me. And any circumstances that you recollect of his life should be wrote down, and I will some time digest them into an Eulogium. These men should not die, this Nature denies, but their

Memories are above her Malice. Enough!

* * * * * *

ERASMUS DARWIN to JOSIAH WEDGWOOD.

DEAR SIR, Lichfield, Nov. 29, 1780.

Your letter communicating to me the death of your friend, and I beg I may call him mine Mr. Bentley, gives me very great concern; and a train of very melancholy ideas succeeds in my mind, unconnected indeed with your loss, but which still at times casts a shadow over me, which nothing but exertion in business or in acquiring knowledge can remove.

This exertion I must recommend to you, as it for a time dispossesses the disagreeable ideas of our loss; and gradually their impression or effect upon us becomes thus weakened, till the traces are scarcely perceptible, and a scar only is left, which reminds us of the past pain of the united wound.

Mr. Bentley was possessed of such variety of knowledge, that his loss is a public calamity, as well as to his friends, though they must feel it the most sensibly! Pray pass a day or two with me at Lichfield, if you can spare the time, at your return. I want much to see you; and was truly sorry I was from home as you went up; but I do beg you will always lodge at my house on your road, as I do at yours, whether you meet with me at home or not.

I have searched in vain in Melmoth's translation of Cicero's letters for the famous consolatory letter of Sulpicius to Cicero on the loss of his daughter (as the work has no index), but have found it, the first letter in a small publication called 'Letters on the most common as well as important occasions in Life:' Newberry, St. Paul's, 1758. This letter is a masterly piece of oratory indeed, adapted to the man, the time, and the occasion. I think it contains everything which could be said upon the subject, and if you have not seen it I beg you to send for the book.

For my own part, too sensible of the misfortunes of others for my own happiness, and too pertinacious of the remembrance of my own [i.e. the death of his

son Charles in 1778], I am rather in a situation to demand than to administer consolation. Adieu. God bless you, and believe me, dear Sir, your affectionate friend

E. DARWIN.

Ten years later he seems to have doubted much about the consolation to be derived from the letter of Sulpicius, for he writes (1790) to Edgeworth:*

I much condole with you on your late loss. I know how to feel for your misfortune. The little Tale you sent is a prodigy, written by so young a person, with such elegance of imagination. Nil admirari may be a means to escape misery, but not to procure happiness. There is not much to be had in this world—we expect too much! I have had my loss also. The letter of Sulpicius to Cicero is fine eloquence, but comes not to the heart; it tugs, but does not draw the arrow. Pains and diseases of the mind are only cured by Time. Reason but skins the wound, which is perpetually liable to fester again.

Amongst the old letters preserved, there is one without any date from Hutton, the founder of the modern science of geology, and I extract its commencement, as proceeding from so illustrious a scientific man. Dr.

* 'Memoirs,' 2nd ed. 1821, vol. ii. p. 110.

D

Darwin seems to have complained to him of having been cheated by some publisher; and Hutton answers:—

If you have no more money than you use, then be as sparing of it as yon please, but if you have money to spend, then pray learn to let yourself be cheated, that is, learn to lay out money for which you have no other use. If this be not philosophy, at least it is good sense; for why the devil should a man have money to be a plague to him, when it is so easy to throw it away; and if thro' a spirit of general benevolence you are afraid of mankind suffering from this root of all evil, for God's sake send it to the bottom of the sea, it there can only poison fish and it will there make in time a noble fossil specimen.

One of his granddaughters has remarked to me, that the term "benevolent" has been associated with his name, almost in the same manner as that of "judicious" with the name of the old divine, Hooker. This is perfectly true, for I have incessantly met with this expression in letters and in the many published notices about him. To the word benevolent, sympathy is generally added, and often generosity, as well as hospitality. Mr. Edgeworth says:* "I have known him intimately

* 'Monthly Magazine '1802 p. 115.

"during thirty-six years, and in that period have witnessed innumerable instances of his benevolence."

His life-long friend, Mr. Keir, wrote to my father (May 12th, 1802) about his character as follows: "I think all those who knew him, will allow that sympathy and benevolence were the most striking features. He felt very sensibly for others, and, from his knowledge of human nature, he entered into their feelings and sufferings in the different circumstances of their constitution, character, health, sickness, and prejudice. In benevolence, he thought that almost all virtue consisted. He despised the monkish abstinences and the hypocritical pretensions which so often impose on the world. The communication of happiness and the relief of misery were by him held as the only standard of moral merit. Though he extended his humanity to every sentient being, it was not like that of some philosophers, so diffused as to be of no effect; but his affection was there warmest where it could be of most service to his family and his friends, who will long remember

d 2

the constancy of his attachment and his zeal for their welfare." His neighbour, Sir Brooke Boothby, after the loss of his child (to whom the beautiful and well-known monument in Ashbourne church was erected), in an ode addressed to Dr. Darwin, writes in strong terms about his sympathy and power of consolation.

But it is fair to state that from my father's conversation, I infer that Dr. Darwin had acted towards him in his youth rather harshly and imperiously, and not always justly; and though in after years he felt the greatest interest in his son's success, and frequently wrote to him with affection, in my opinion the early impression on my father's mind was never quite obliterated.

I have heard indirectly (through one of his stepsons) that he was not always kind to his son Erasmus, being often vexed at his retiring nature, and at his not more fully displaying his great talents. On the other hand his children by his second marriage seem to have entertained the warmest affection for him.

ERASMUS DARWIN to HIS SON ROBERT.

DEAR ROBERT, April 19, 1789.

I am sorry to hear you say you have many enemies, and one enemy often does much harm. The best way, when any little slander is told one, is never to make any piquant or angry answer; as the person who tells you what another says against you, always tells them in return what you say of them. I used to make it a rule always to receive all such information very coolly, and never to say anything biting against them which could go back again; and by these means many who were once adverse to me, in time became friendly. Dr. Small always went and drank tea with those who he heard had spoken against him; and it is best to show a little attention at public assemblies to those who dislike one; and it generally conciliates them.

* * * * * *

Robert seems to have consulted his father about some young man, whom he wished to see well started as an apothecary, and received the following answer:—

ERASMUS DARWIN to HIS SON ROBERT.

DEAR ROBERT, DERBY, Dec. 17, 1790.

I cannot give any letters of recommendation to Lichfield, as I am and have been from their in-

fancy acquainted with all the apothecaries there; and as such letters must be directed to some of their patient?, they would both feel and resent it. When Mr. Mellor went to settle there from Derby I took no part about him. As to the prospect of success there, if the young man who is now at Edinburgh should take a degree (which I suppose is probable), he had better not settle in Lichfield.

I should advise your friend to use at first all means to get acquainted with the people of all ranks. At first a parcel of blue and red glasses at the windows might gain part of the retail business on market clays, and thus get acquaintance with that class of people. I remember Mr. Green, of Lichfield, who is now growing very old, once told me his retail business, by means of his show-shop and many-coloured window, produced him £100 a year. Secondly, I remember a very foolish, garrulous apothecary at Cannock, who had great business without any knowledge or even art, except that he persuaded people he kept good drugs; and this he accomplished by only one stratagem, and that was by loving every person who was so unfortunate as to step into his shop with the goodness of his drugs. "Here's a fine piece of assafœtida, smell of this valerian, taste this album grascum. Dr. Fungus says he never saw such a fine piece in his life." Thirdly, dining every market day at a farmers' ordinary would bring him some acquaintance, and I don't think a little impedi-

ment in his speech would at all injure him, but rather the contrary by attracting notice. Fourthly, card assemblies,—I think at Lichfield surgeons are not admitted as they are here;—but they are to dancing assemblies; these therefore he should attend. Thus have I emptied my quiver of the arts of the

Pharmacopol. Dr. K——d, I think, supported his business by perpetual boasting, like a Charlatan; this does for a blackguard character, but ill suits a more polished or modest man.

If the young man has any friends at Shrewsbury who could give him letters of introduction to the proctors, this would forward his getting acquaintance. For all the above purposes some money must at first be necessary, as he should appear well; which money cannot be better laid out, as it will pay the greatest of all interest by settling him well for life. Journeymen Apothecaries have not greater wages than many servants; and in this state they not only lose time, but are in a manner lowered in the estimation of the world, and less likely to succeed afterwards. I will certainly send to him, when first I go to Lichfield. I do not think his impediment of speech will injure him; I did not find it so in respect to myself. If he is not in such narrow circumstances but that he can appear well, and has the knowledge and sense you believe him to have, I dare say he will succeed anywhere. A letter of introduction from you to Miss Seward, men-

tioning his education, may be of service to him, and another from Mr. Howard.

Adieu, from, dear Robert,

Yours most affectionately,

E. DARWIN.

My father spoke of Dr. Darwin as having great powers of conversation. Lady Charleville, who had been accustomed to the most brilliant society in London, told him that Dr. Darwin was one of the most agreeable men whom she had ever met. He himself used to say "there were two sorts of agreeable persons in conversation parties—agreeable talkers and agreeable listeners."

He stammered greatly, and it is surprising that this defect did not spoil his powers of conversation. A young man once asked him in, as he thought, an offensive manner, whether he did not find stammering very inconvenient. He answered, "No, Sir, it gives me time for reflection, and saves me from asking impertinent questions." Miss Seward speaks of him as being extremely sarcastic, but of this I can find no evidence in his letters or elsewhere. It is a pity that Dr. Johnson in his visits to Lichfield rarely

met Dr. Darwin; but they seem to have disliked each other cordially, and to have felt that if they met they would have quarrelled like two dogs. There can, I suppose, be little doubt that Johnson would have come off victorious. In a volume of MSS. by Dr. Darwin, in the possession of one of his granddaughters, there is the following stanza:

From Lichfield famed two giant critics come,

Tremble, ye Poets! hear them! "Fe, Fo, Fum!"

By Seward's arm the mangled Beaumont bled,

And Johnson grinds poor Shakespear's bones for bread.

He is evidently alluding to Mr. Seward's edition of 'Beaumont and Fletcher's Plays,' and to Johnson's edition of 'Shakespear 'in 1765.

He possessed, according to my father, great facility in explaining any difficult subject; and he himself attributed this power to his habit of always talking about whatever he was studying, "turning and moulding the subject according to the capacity of his hearers." He compared himself to Gil Blas's uncle, who learned the grammar by teaching it to his nephew.

When he wished to make himself disagreeable for any good cause, he was well able to do so. Lady * * * married a widower, and became so jealous of his former wife that she cut and spoiled her picture, which hung up in one of the rooms. The husband, fearing that his young wife was becoming insane, was greatly alarmed, and sent for Dr. Darwin. When he arrived he told her in the plainest manner many unpleasant truths, amongst others that the former wife was infinitely her superior in every respect, including beauty. The poor lady was astonished at being thus treated, and could never afterwards endure his name. He told the husband if she again behaved oddly, to hint that he would be sent for. The plan succeeded perfectly, and she ever afterwards restrained herself.

My father was much separated from Dr. Darwin after early life, so that he remembered few of his remarks, but he used to quote one saying as very true: "that the world was not governed by the clever men, but by the active and energetic." He used also to quote another saying, that "common

sense would be improving, when men left off wearing as much flour on their heads as would make a pudding; when women left off wearing rings in their ears, like savages wear nose rings; and when firegrates were no longer made of polished steel."

Dr. Darwin has been frequently called an atheist, whereas in every one of his works distinct expressions may be found showing that he fully believed in God as the Creator of the universe. For instance, in the 'Temple of Nature,' published posthumously,* he writes: "Perhaps all the productions of nature are in their progress to greater perfection! an idea countenanced by modern discoveries and deductions concerning the progressive formation of the solid parts of the terraqueous globe, and consonant to the dignity of the creator of all things." He concludes one chapter in 'Zoonomia' with the words of the Psalmist: "The heavens declare the Glory of God, and the firmament sheweth his handiwork."

* 'Temple of Nature,' 1803, note, p. 54. See also the striking foot-note (p. 142) on the immutable properties of matter "received from the hand of the Creator," etc.

He published an ode on the folly of atheism, with the motto "I am fearfully and wonderfully made," of which the first verse is as follows:—

1.

Dull atheist, could a giddy dance

Of atoms lawless hurl'd

Construct so wonderful, so wise,

So harmonised a world?

"With reference to morality he says:* "The famous sentence of Socrates, 'Know your-self,' .... however wise it may be, seems to be rather of a selfish nature...... But the sacred maxims of the author of Christianity, 'Do as you would be done by,' and 'Love your neighbour as yourself,' include all our duties of benevolence and morality; and, if sincerely obeyed by all nations, would a thousandfold multiply the present happiness of mankind."

Although Dr. Darwin was certainly a theist in the ordinary acceptation of the term, he disbelieved in any revelation. Nor did he feel much respect for unitarianism, for he used to say that "unitarianism was

* 'Temple of Nature,' 1803, note p. 124.

a feather-bed to catch a falling Christian.

Remembering through what an exciting period of history Erasmus lived, it is singular how rarely there is more than an allusion in his letters to politics. He would now be called a liberal, or perhaps rather a radical. He seems to have wished for the success of the North American colonists in their war for independence; for he writes to Wedgwood (Oct. 17, 1782): "I hope Dr. Franklin will live to see peace, to see America recline under her own vine and fig-tree, turning her swords into plough-shares, &c." Like so many other persons, he hailed the beginning of the French Revolution with joy and triumph. Miss Seward, in a letter to Dr. Whalley, dated May 18, 1792, says: "I should indeed now begin to fear for France; but Darwin yet asserts that, in spite of all disasters, the cause of freedom will triumph, and France become, ere long, an example, prosperous as great, to the surrounding nations."

She remarks in another letter, Darwin "was

'a far-sighted politician, and foresaw and 'foretold the individual and ultimate mischief of every pernicious measure of the late Cabinet."*

In February 1789, he tells Wedgwood that he had been reading 'Colonel Jack,' by De Foe, and suggests that the account there given of the generous spirit of black slaves should be republished in some journal. Again, on April 13th of the same year (1789), he writes: "I have just heard that there are muzzles or gags made at Birmingham for the slaves in our islands. If this be true, and such an instrument could be exhibited by a speaker in the House of Commons, it might have a great effect. Could not one of their long whips or wire tails be also procured and exhibited? But an instrument of torture of our own manufacture would have a greater effect, I dare say."

The following lines on Slavery were published in Canto III. of the 'Loves of the Plants,' 1790:—

* Journals of Dr. Whalley, 1863, vol. ii. pp. 73, 220-222.

"Throned in the vaulted heart, his dread resort,

Inexorable CONSCIENCE holds his court;

With still small voice the plots of Guilt alarms.

Bares his mask'd brow, his lifted hand disarms;

But wrapp'd in might with terrors all his own,

He speaks in thunder, when the deed is done.

Hear him, ye Senates! hear this truth sublime,

He, who allows oppression, shares the crime."

The date of this poem and of the above letter should be noticed, for let it be remembered that even the slave-trade was not abolished until 1807; and in 1783 the managers of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel absolutely declined, after a full discussion, to give Christian instruction to their slaves in Barbadoes.*

He sympathised warmly with Howard's noble work of reforming the state of the prisons throughout Europe, as his lines in the 'Loves of the Plants' (Canto II.) show:—

"And now, Philanthropy! thy rays divine

Dart round the globe from Zembla to the line;

O'er each dark prison plays the cheering light,

Like northern lustres o'er the vault of night.—

From realm to realm, with cross or crescent crown'd,

Where'er mankind and misery are found,

* Lecky, 'Hist, of England in the Eighteenth Century,' 1878, vol. ii. p. 17.

O'er burning sands, deep waves, or wilds of snow,

Thy Howard journeying seeks the house of woe—

Down many a winding step to dungeons dank,

Where anguish wails aloud, and fetters clank;

To caves bestrew'd with many a mouldering bone,

And cells, whose echoes only learn to groan;

Where no kind bars a whispering friend disclose,

No sunbeam enters, and no zephyr blows,

He treads, inemulous of fame or wealth,

Profuse of toil, and prodigal of health;

With soft assuasive eloquence expands

Power's rigid heart, and opes his clenching hands,

Leads stern-eyed Justice to the dark domains,

If not to sever, to relax the chains.

The spirits of the Good, who bend from high

Wide o'er these earthly scenes their partial eye,

When first, arrayed in Virtue's purest robe,

They saw her Howard traversing the globe;

Mistook a mortal for an Angel-Guest,

And ask'd what Seraph-foot the earth imprest.

Onward he moves! Disease and Death retire,

And murmuring demons hate him, and admire."

Judging from his published works, letters, and all that I have been able to gather about him, the vividness of his imagination seems to have been one of his pre-eminent characteristics. This led to his great originality of thought, his prophetic spirit both in science and in the mechanical arts, and to his overpowering tendency to theorise and generalise.

Nevertheless, his remarks, hereafter to be given, on the value of experiments and the use of hypotheses show that he had the true spirit of a philosopher. That he possessed uncommon powers of observation must be admitted. The diversity of the subjects to which he attended is surprising. But of all his characteristics, the incessant activity or energy of his mind was, perhaps, the most remarkable. Mr. Keir, himself a distinguished man, who had seen much of the world, and who "had been well acquainted with Dr. Darwin for nearly half a century," after his death wrote (May 12th, 1802) to my father: "Your father did indeed retain more of his original character than almost any man I have known, excepting, perhaps, Mr. Day [author of 'Sandford and Merton,' &c.]. Indeed, the originality of character in both these men was too strong to give way to the example of others." He afterwards proceeds: "Your father paid little regard to authority, and he quickly perceived the analogies on which a new theory could be founded. This penetration or sagacity by which he was able to discover very remote

E

causes and distant effects, was the characteristic of his understanding. Perhaps it may be thought in some instances to have led him to refine too much, as it is difficult in using a very sharp-pointed instrument to avoid sometimes going rather too deep. By this penetrating faculty he was enabled not only to trace the least conspicuous indications of scientific analogy, but also the most delicate and fugitive beauties of poetic diction. If to this quality you add an uncommon activity of mind and facility of exertion, which required the constant exercise of some curious investigation, you will have, I believe, his principal features. His activity continued to his latest days; and the following letter, written when he was sixty-one years old to my father, shows his continued zeal in his profession.

ERASMUS DARWIN to HIS SON ROBERT.

DEAR EGBERT, DERBY, April 13,1792.

I think you and I should sometimes exchange a long medical letter, especially when any uncommon diseases occur; both as it improves one in writing

clear intelligible English, and preserves instructive cases. Sir Joshua Reynolds, in one of his lectures on pictorial taste, advised painters, even to extreme old age, to study the works of all other artists, both ancient and modern; which he says will improve their invention, as they will catch collateral ideas (as it were) from the pictures of others, which is a different thing from imitation; and adds, that if they do not copy others, they will be liable to copy themselves, and introduce into their work the same faces, and the same attitudes again and again. Now in medicine I am sure unless one reads the work of others, one is liable perpetually to copy one's own prescriptions, and methods of treatment; till one's whole practice is but an imitation of one's self; and half a score medicines make up one's whole materia medica; and the apothecaries say the doctor has but 4 or 6 prescriptions to cure all diseases.

Reasoning thus, I am determined to read all the new medical journals which come out, and other medical publications, which are not too voluminous; by which one knows what others are doing in the medical world, and can astonish apothecaries and surgeons with the new and wonderful discoveries of the times. All this harangue lately occurred to me on reading the trials made by Dr. Crawford.

* * * * * *

My father seems to have urged him, about the year 1793, to leave off professional work;

e 2

he answered, "it is a dangerous experiment, and generally ends either in drunkenness or hypochrondriacism. Thus I reason, one must do something (so country squires fox-hunt), otherwise one grows weary of life, and becomes a prey to ennui. Therefore one may as well do something advantageous to oneself and friends or to mankind, as employ oneself in cards or other things equally insignificant." During his frequent and long journeys, he read and wrote much in his carriage, which was fitted up for the purpose. Nor was travelling an easy affair in those days, for owing to the state of the roads, a carriage could hardly reach some of the houses which he had to visit; and I hear from one of his granddaughters that an old horse named the "Doctor," with a saddle on, used to follow behind the carriage, without being in any way fastened to it; and when the road was too bad, he got out and rode upon Doctor. This horse lived to a great age, and was buried at the Priory.

When at home he was an early riser; and he had his papers so arranged (as I have heard from my father) that if he awoke in

the night he was able to get up and continue his work for a time, until he felt sleepy. Considering his indomitable activity, it is a singular fact that he suffered much from a sense of fatigue. On my once remarking to my father, how greatly fatigued he seemed to be after his day's work, he answered, "I inherit it from my father."

In some notes made by my father in 1802, he states that Dr. Darwin naturally was of a bold disposition, but that a succession of accidents made a deep impression on his mind, and that he became very cautious. When he was about five years old he received an accidental blow on the top of his head, sufficiently severe to give him a white lock of hair for life. Later on, when he was fishing with his brothers, they put him into a bag with only his feet out, and being thus blinded he walked into the river, and was very nearly drowned. Again, when he and Lord George Cavendish were playing with gunpowder at school, it .exploded, and he was badly injured; and lastly, he broke his kneecap.

Owing to his lameness, he was clumsy in .his movements, but when young, was a very

active man. His frame was large and bulky, and he grew corpulent when old. He was deeply pitted with the small-pox.

It is remarkable that in so large a town as Derby, and at so late a period as 1784, there was no public institution for the relief of the poor in sickness. Dr. Darwin therefore at this time drew up a circular, the MS. of which is in my possession, stating that "as the small-pox has already made great ravages in Derby, showing much malignity even at its commencement; and as it is now three years since it was last epidemic in this town, there is great reason to fear that it will become very fatal in the approaching spring, particularly amongst the poor, who want both the knowledge and the assistance necessary for the preservation of their children." He accordingly proposed that a society should be formed—the members to subscribe a guinea each, and that a room should be hired as a dispensary, where the medical men of the town might give their attendance gratuitously. The poor were to be directed to take their prescriptions in due order to all the druggists in the town, apparently to disarm opposition.

The circular then expresses the hope that the dispensary "may prove the foundation-stone of a future infirmary."

In this same year of 1784 he seems to have taken the chief part in founding a Philosophical Society in Derby. The members met for the first time at his house, and he delivered to them a short but striking address, from which the following passages may be given: "I come now to the second source of our accurate ideas. As we are fashioned and constituted by the niggard hand of Nature with such imperfect and contracted faculties, with so few and such imperfect senses; while the bodies, which surround us, are indued with infinite variety of properties; with attractions, repulsions, gravitations, exhalations, polarities, minuteness, irresistance, &c., which are not cognizable by our dull organs of sense, or not adapted to them; what are we to do? shall we sit down contented with ignorance, and after we have procured our food, sleep away our time like the inhabitants of the woods and pastures? No, certainly!—since there is another way by which we may indirectly

"become acquainted with those properties of bodies, which escape our senses; and that is by observing and registering their effects upon each other. This is the tree of knowledge, whose fruit forbidden to the brute creation has been plucked by the daring hand of experimental philosophy."

He concludes the address with the words: "I hope at some distant time, perhaps not very distant, by our own publications we may add something to the common heap of knowledge; which I prophecy will never cease to accumulate, so long as the human footstep is seen upon the earth."

No man has ever inculcated more persistently and strongly the evil effects of intemperance than did Dr. Darwin; but chiefly on the grounds of ill-health, with its inherited consequences; and this perhaps is the most practical line of attack. It is positively asserted that he diminished to a sensible extent the practice of drinking amongst the gentry of the county.*

* The following short history of temperance societies is extracted from Dr. Krause's MS. notes on Dr. Darwin:—"The oldest temperance societies were founded in North America in 1808 by the efforts of Dr. Rush, and in Great Britain in 1829, chiefly at the suggestion of Mr. Dunlop.

He himself during many years never touched alcohol under any form; but he was not a bigot on the subject, for in old age he informed my father that he had taken to drink daily two glasses of home-made wine with advantage. Why he chose home-made wine is not obvious; perhaps he fancied that he thus did not depart so widely from his long-continued rule. He also wrote (Oct. 15, 1772) to Wedgwood, who had feeble health: "I would advise you to live as high as your constitution will admit of, in respect to both eating and drinking. This advice could be given to very few people! If you were to weigh yourself once a month you would in a few months learn whether this method was of service to you." His advocacy of the cause is not yet

See Samuel Couling, 'History of the Temperance Movement in Great Britain and Ireland, from the earliest date to the present time; 'London, 1862. In Germany, indeed, the Archduke Frederick of Austria had founded a temperance order as early as 1439, which was followed in 1600 by the temperance order established by the Landgrave of Hesse, but these were only imitations of the Templars and other orders of knighthood, which sought by vows to suppress the coarse excesses of drinking bouts, as is indicated by the motto of the first-mentioned order: 'Halt Maas! 'The suggestion of the establishment in Germany of true temperance societies on the American and English model was due to King Frederick William III."

forgotten, for Dr. Richardson, in his address in 1879 to the "British Medical Temperance Association," remarks: "the illustrious Haller, Boerhaave, Armstrong, and particularly Erasmus Darwin, were earnest in their support of what we now call the principles of temperance."

When a young man he was not always temperate. Miss Seward relates* a story, which would not have been worth notice had it not heen frequently quoted. My grandfather went on a picnic party in Mr. Sneyd's boat down the Trent, and after luncheon, when (in Miss Seward's elegant language), "if not absolutely intoxicated, his spirits were in a high state of vinous exhilaration, he suddenly got out of the boat, swam ashore in his clothes, and walked coolly over the meadows towards the town of Nottingham. He there met an apothecary, whose remonstrances about his wet clothes he answered by saying that the unusual internal stimulus would counteract the external cold and moisture; he then mounted on a tub, and harangued the mob in an extremely sensible manner on

* 'Memoirs of Dr. Darwin,' pp. 64-68.

sanitary arrangements. But it is obvious that these harangues must have been largely the work of Miss Seward's own imagination. There was, however, some truth in this story, for his widow, who did not believe a word of it, wrote to Mr. Sneyd, whose answer lies before me. He admits that something "similar" did happen, but gives no details, and advises Mrs. Darwin "to take no notice" of this part of her (Miss Seward's) very unguarded and scandalous publication." To show what the gentry of the county thought of her book at the time, I will add that Mr. Srieyd, after alluding in the same letter to her account of the death of his son Erasmus, remarks: "The authoress deserves to be exposed for her want of veracity and every humane feeling." One of Dr. Darwin's stepsons (as I hear from his daughter) used always to maintain that this half-tipsy freak was due to some of the gentlemen of the party, "who were vexed at his temperate habits," having played him a trick; and this, I presume, means that he was persuaded to drink something as weak which was really strong.

The following incident related by Mr. Edgeworth* illustrates the humane side of his character. Mr. Edgeworth had corresponded, as a stranger, with Dr. Darwin, about the construction of carriages, and came to Lichfield to see him, but did not find him at home. He was asked by Mrs. Darwin to stay to supper. "When this was nearly finished, a loud rapping at the door announced the doctor. There was a bustle in the hall, which made Mrs. Darwin get up and go to the door. Upon her exclaiming that they were bringing in a dead man, I went to the hall. I saw some persons, directed by one whom I guessed to be Doctor Darwin, carrying a man who appeared motionless. 'He is not dead,' said Dr. Darwin, 'he is only dead drunk. I found him,' continued the doctor, 'nearly suffocated in a ditch; I had him lifted into my carriage, and brought hither, that we might take care of him to-night.'" Not many men would have done anything so disagreeable as to bring home a drunken man in their carriage. When a light was

* 'Memoirs of R. L. Edgeworth' 2nd edit. vol. i. p. 158.

brought, the man was found to be, to the astonishment of all present, Mrs. Darwin's brother, "who for the first time in his life," as Mr. Edgeworth was assured, "had been intoxicated in this manner, and who would undoubtedly have perished had it not been for Dr. Darwin's humanity." We must remember that in those good old days it was not thought much of a disgrace to be very drunk. After the man had been put to bed, Mr. Edgeworth says that Dr. Darwin and he first discussed the construction of carriages and then various literary and scientific subjects, so that "he discovered that I had received the education of a gentleman." "Why, I thought," said the doctor, "that you were only a coachmaker." "That was the reason," said I, "that you looked so surprised at finding me at supper with Mrs. Darwin. But you see, doctor, how superior in discernment ladies are even to the most learned gentleman."

He was kind and considerate to his servants, as the two following stories show. His son Robert owed him a small sum of money, and instead of being paid, he asked Robert to buy

a goose-pie with it, for which it seems Shrewsbury was then famous, and send it at Christmas to an old woman living in Birmingham, "for she, as you may remember, was your nurse, which is the greatest obligation, if well performed, that can be received from an inferior." This was in the year 1793.

On the day of his death, in the early morning, whilst writing a long and affectionate letter to Mr. Edgeworth, he was seized with a violent shivering fit, and went into the kitchen to warm himself before the fire. He there saw an old and faithful maid servant churning, and asked her why she did this on a Sunday morning. She answered that she had always done so, as he liked to have fresh butter every morning. He said: "Yes, I do, but never again churn on a Sunday!"

That Dr. Darwin was charitable, we may believe on Miss Seward's testimony, as it is supported by concurrent evidence. After saying that he would not take fees from the priests and lay-vicars of the Cathedral of Lichfield, she adds: "Diligently, also, did he attend to the health of the poor in the city

and afterwards at Derby, and supplied their necessities of food, and all sort of charitable assistance."* Sir Brooke Boothby also, in one of his published sonnets, says:—

If bright example more than precept sway

Go, take your lesson from the life of Day,

Or, Darwin, thine whose ever-open door

Draws, like Bethesda's pool, the suffering poor

Where some fit cure the wretched all obtain

Believed at once from poverty and pain.

The gratitude of the poor to him was shown on two occasions in a strange manner.† Having to see a patient—one of the Cavendishes—at Newmarket during the races, he slept at an hotel, and during the night was awakened by the door being gently opened. A man came to his bedside and thus spoke

* 'Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin,' 1804, p. 5.

† These stories appear at first hardly credible, but I have traced them, more or less clearly, through four distinct channels to my grandfather, whose veracity has never been doubted by any one who knew him. The fundamental facts are the same with respect to the jocky story, but the accessories differ to an extreme degree. With respect to the second story even some of the fundamental facts differ, and I feel much doubt about it. It is quite curious how stories get unintentionally altered in the course of years. They were first communicated to me by a daughter of Violetta Darwin, who heard her mother relate them.

to him: "I heard that you were here, but durst not come to speak to you during the day. I have never forgotten your kindness to my mother in her had illness, but have not heen able to show you my gratitude before. I now tell you to bet largely on a certain horse (naming one), and not on the favourite, whom I am to ride, and who we have settled is not to win." My grandfather afterwards saw in the newspaper that to the astonishment of everyone, the favourite had not won the race.

The second story is, that as the doctor was riding at night on the road to Nottingham a man on horseback passed him, to whom he said good night. As the man soon slackened his pace, Dr. Darwin was forced to pass him, and again spoke, but neither time did the man give any answer. A few nights afterwards a traveller was robbed at nearly the same spot by a man who, from the description, appeared to be the same. It is added that my grandfather out of curiosity visited the robber in prison, who owned that he had intended to rob him, hut added: "I thought it was you, and when you spoke I was sure of it. You

saved my life many years ago, and nothing could make me rob you."*

Notwithstanding so much evidence of Dr. Darwin's benevolence and generosity, it has been represented that he valued money inordinately, and that he wrote only for gain. This is the language of a notice published shortly after his death,† which also says that he was very vain, and that "flattery was found to be the most successful means of gaining his notice and favour."

All that I have been able to learn goes to show that this was a mistaken view of his character.

In a letter to my father, dated Feb. 7, 1792, he writes:

"As to fees, if your business pays you well on the whole, I would not be uneasy about making absolutely the most of it. To live comfortably all one's life, is better than to make a very large fortune towards the end of it."

In another letter not dated, but written in

* In one version of this story, the visit of Dr. Darwin to the man is not mentioned, so that there is then no point to the story.

† ' Monthly Magazine,' or 'British Register,' vol. xiii. 1802, p. 457.

F

1793, he remarks: "There are two kinds of covetousness, one the fear of poverty, the other the desire of gain. The former, I believe, at some times affects all people who live by a profession." Again, his son Erasmus, in writing on Nov. 12, 1792, to my father, after remarking how rich he was becoming, adds: "I am not afraid of being rich, as our father used to say at Lichfield he was, for fear of growing covetous; to avoid which misfortune, as you know, he used to dig a certain number of duck puddles every spring, that he might fill them up again in the autumn." How it was possible to expend much money in digging duck puddles, it is not easy to see.

It is probable that the only foundation for the reviewer's statements, and for others of a like kind, was the habit he had—perhaps a foolish one—of often speaking about himself in a quizzing or bantering tone. Mr. Edgeworth, who had known him "intimately during thirty-six years," in answer to the reviewer, writes:*

"I am most anxious to contradict that

* 'Monthly Magazine, vol. ii. 1802, p. 115.