[title page]

DOWN

THE HOME OF THE DARWINS

The Story of a House and the People who lived there

SIR HEDLEY ATKINS KBE

Published by PHILLIMORE for

The Royal College of Surgeons of England

Lincoln's Inn Fields London

[page i]

First published 1974

Revised impression 1976

© Sir Hedley Atkins KBE 1974, 1976

ISBN 0 85033 231 1

Designed at The Curwen Press Ltd, London E 13

Printed and bound Photo-litho reprint in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham

from earlier impression

[page ii]

TO MY WIFE

Who has worked so hard to make the house and garden once more a family home

[page iii]

CONTENTS

| List of Illustrations | page 1 | |

| Foreword | 3 | |

| Preface | 5 | |

| Chapter I | The Land, the Village and the House | 7 |

| Chapter II | The House and Garden | 18 |

| Chapter III | Life at Down | 32 |

| Chapter IV | Religion and the Church | 45 |

| Chapter V | Culture and Education | 55 |

| Chapter VI | Illness | 65 |

| Chapter VII | The Staff | 72 |

| Chapter VIII | Animals | 78 |

| Chapter IX | Comings and Goings | 85 |

| Chapter X | Income and Expenditure | 95 |

| Chapter XI | Fate Uncertain | 101 |

| Chapter XII | Downe House School | 106 |

| Chapter XIII | Buckston Browne to the Rescue | 111 |

| Chapter XIV | A National Trust | 120 |

| References | 126 | |

| Index | 128 | |

| Tables | 1. The Owners of Down House | 15 |

| 2. Periods Away from Home | 90 | |

| 3. Annual Income and Surplus | 97 | |

| 4. Annual Household Expenditure | 99 |

[page] 1

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

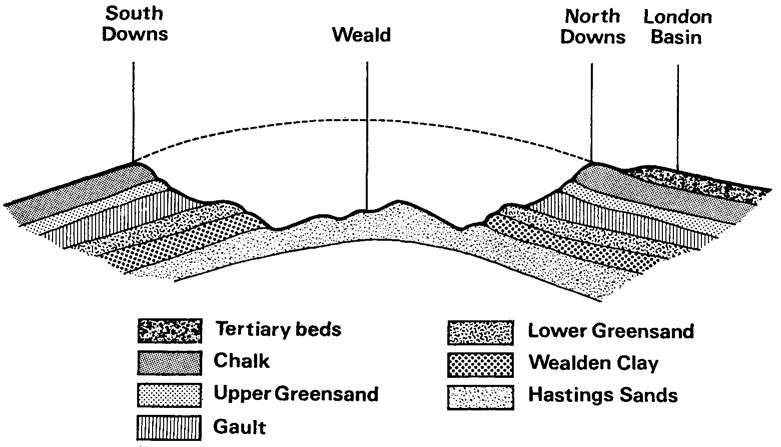

| 1 | Section through the North and South Downs | page 8 | |

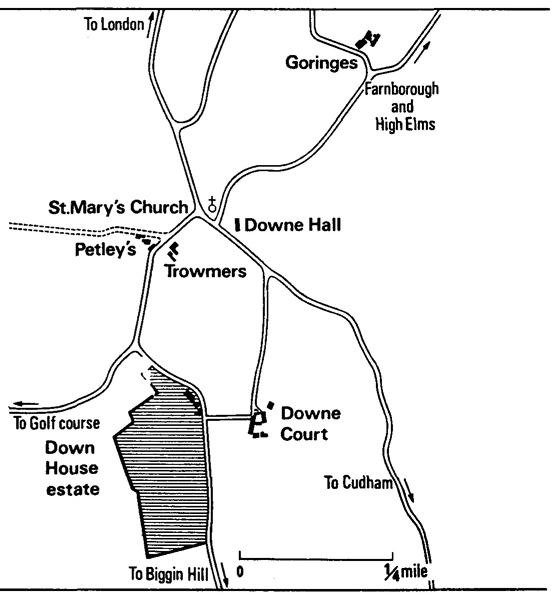

| 2 | Plan of the Village of Down | 11 | |

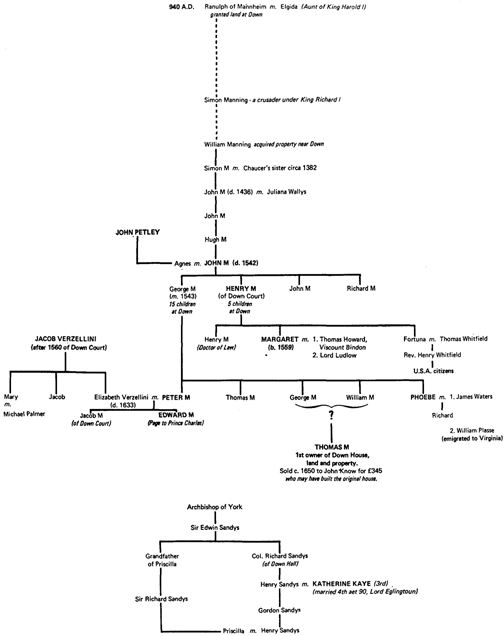

| 3 | Family Tree of some Down notables | 13 | |

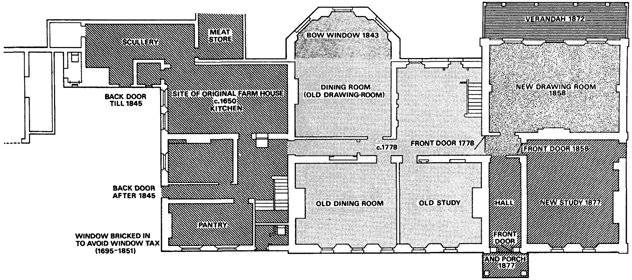

| 4 | Plan of Down House | 23 | |

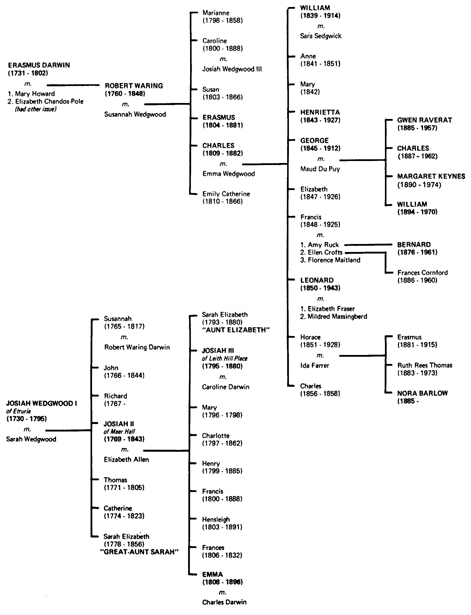

| 5 | The Darwin Family Tree | 33 | |

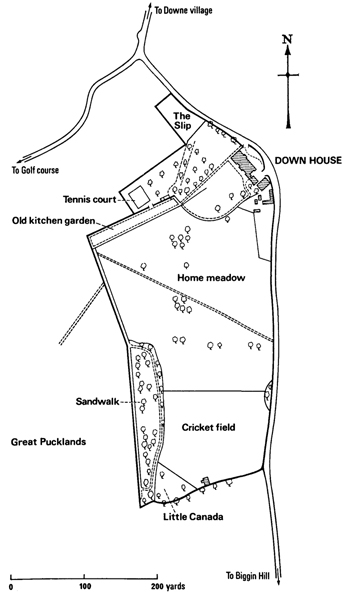

| 6 | Plan of the Estate | 34 | |

| The Plates | I | Down House | facing page 24 |

| (Photo by courtesy of Col. James Creedy) | |||

| II | Down Chapel in 1786, now Downe Church | 25 | |

| (by courtesy of the Rev. Jack Harrison) | |||

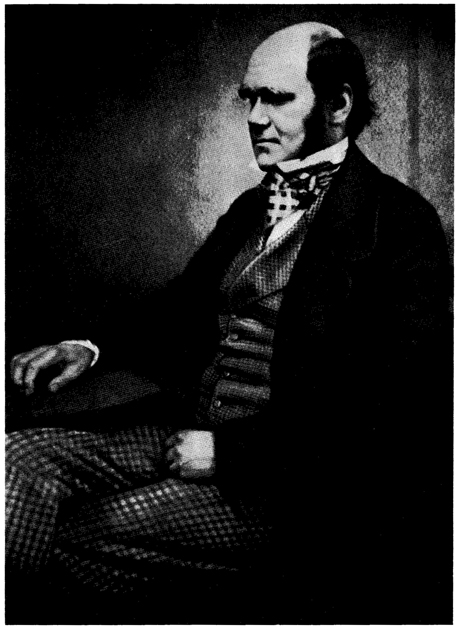

| III | Charles | 40 | |

| IV | Squirrels mistake Mr. Darwin for a tree | 41 | |

| (by courtesy of Messrs. G. P. Putnam) | |||

| V | Emma Darwin | 104 | |

| VIA | Miss Willis' Style of Conducting a Rehearsal | 105 | |

| VIB | Miss Willis swimming at Lerici | 105 | |

| (both by courtesy of Messrs. John Murray) | |||

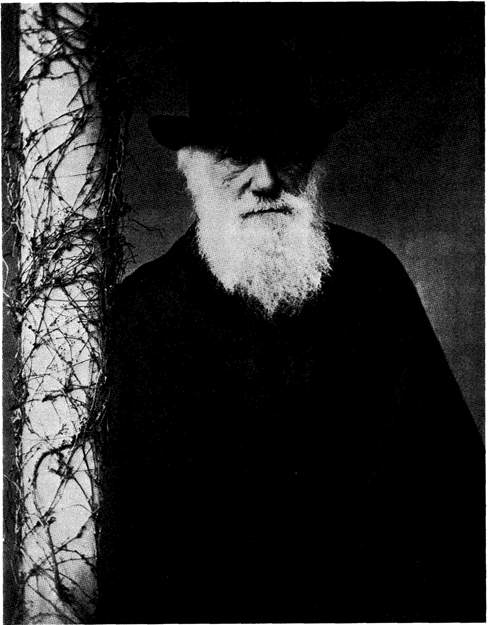

| VII | Charles Darwin, the Last Years | 120 | |

| VIII | Sir Arthur Keith and Sir George Buckston Browne in the Garden at Down House | 121 | |

| (by courtesy of Messrs. Churchill Livingstone) |

[page] 3

FOREWORD

Charles Darwin has always had a fascination for the biographer and many volumes have been written on his life and works. There are probably several reasons for this appeal. One obvious reason is that the principle of Evolution as presented in the Origin of Species has had such a widespread influence throughout the biological sciences. Another reason is that he was a prolific writer of books and letters and lived in an age when letters tended to be kept for posterity. Most of his letters are preserved today and provide a wealth of material for the historian. The facts of Darwin's life also have a natural appeal in that they tend to fit in with the archetype of the ideal scientific life. Starting with a wild voyage of discovery, Darwin's later years were devoted to continuous writing and study, interrupted by the battle against ill-health, and ended with the flowering of worldly fame and success. Whatever the reasons may be for Darwin's appeal to the biographer, a great many books have been written on his life and achievements.

In this context there are several aspects of the present work that make it an interesting addition to the Darwin bibliography. Some of the material used in this book comes from the archives of Down House and is being published for the first time. The original documents have of course been available to scholars in the past, but this is not the same thing as being presented in a published book. The bulk of Charles Darwin's letters are now in the possession of the Cambridge University library, including most of those that are of scientific interest. The letters in the Down House archives are mainly those that are concerned with the social life of the family at Down House. The use of some of this material for the first time adds to our knowledge of Darwin and his family.

The theme of the book is the history of the estate rather than just being a biography of one of its owners and an interesting part of the book is the later history after the departure of the Darwin family. Parts of this story have been recorded elsewhere but the complete story has not been published before as a single narrative. Over this period the history of the estate has had its twists and turns before reaching its present form as the Darwin Museum under the auspices of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

The Darwin Museum at Down House represents a memorial to the life of one of the world's leading scientists and one hopes that it will continue to fulfil this role for many years to come.

George Darwin

1.9.74

[page] 5

PREFACE

The number of books written about Charles Darwin is prodigious and every year new volumes appear dealing with his scientific work, his philosophy or the resounding impact that his writings had on scientific thought in the latter part of the nineteenth century and which they still exert today. These books are written mostly by experts in his particular field of inquiry and help to illuminate the character and personality of Darwin through a study of his work. This book is different; it makes an attempt to reveal the personalities of Darwin and his wife Emma through a study of the house in which he lived for forty years and where he died. This essay constitutes the main body of the book.

It was felt that a brief description of the background of Down House might not be regarded as irrelevant and so Chapter I is devoted to the story of the land upon which the house was built, the village to which it brought fame and the early history of the building before the Darwins came to live there.

In recounting the history of the house a number of other characters emerge unconnected with the Darwin family, many of them striking personalities in their own right, most of whom stride on to the stage in the last four chapters.

The reader may be perplexed by the spelling of Downe Village, as it now appears in the Post Office Directory. Up until the middle of the nineteenth century the village was spelt 'Down' (without an 'e') as the house is still but at that time officialdom fearing, so it is said, that it might be confused with Co. Down in Ireland dictated that it should be spelt "Downe". Darwin resolutely refused to alter the spelling of his home and, whilst we may applaud his sturdy independence of spirit, this leads to endless confusion today in ordering goods from shops and also presents a problem when writing this book. I have attempted to solve this problem by adhering to the old spelling in those parts of the book which deal with the periods when this spelling was in vogue and adopting the present spelling in the last four chapters.

Another question was how to refer to the principal character: Mr. Darwin, Charles Darwin or just Charles. No claim for consistency can be made in this respect and all three ways of referring to him are used. If the setting is formal he is generally referred to as Mr. Darwin or Darwin, but in the intimacy of the family circle I have been emboldened to refer to him as Charles, which is much more friendly.

Much of the source material comes from books and letters published more than seventy years ago which, for most people, are difficult to obtain, and much from original manuscripts which are kept in The Down House Museum and which have not hitherto been published. For permission to use all such material I am grateful to the Royal College of Surgeons of England who have maintained this house and its estate as a memorial to Charles Darwin since 1953. The College has also allocated from the Down House Fund

[page] 6

a grant which has made the publication of this book possible, for which I should wish to record my profound gratitude.

Many people have given unstinting help in the preparation of this book: Lord Zuckerman (anthropology), Dr. P. T. Warren (geology) and Dr. J. N. L. Myers (mediaeval history) have kindly read the first chapter and corrected the more egregious errors. If any remain this is due to my imperfect understanding of these complicated matters and the blame is in no sense to be laid at their door.

Mr. Keith Dalton has written a splendid account of his great-grandfather, Col. Johnson, and has generously allowed me to use this material in relating the story of an interesting owner of Down House who migrated to Canada. Mr. R. S. Handley has given me the most welcome and helpful advice.

Mrs. Gillian Bragg is responsible for the maps, charts and drawings over which she took immense trouble. My particular thanks are due to Miss Marjorie Gardener who not only read the original typescript and made many valuable suggestions and corrections, but also corrected the proofs and helped to compile the index, all with indefatigable energy and care. Once more I must take responsibility for any remaining errors.

I should like to record my gratitude for the generosity of the authors or their executors and the publishers of the following works from which I have been allowed to quote, sometimes in extenso.

Olive Willis and Downe House by Anne Ridler, John Murray; The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, ed. Francis Darwin, John Murray; Emma Darwin, A Century of Family Letters by H. E. Litchfield, John Murray; Sir George Buckston Browne by Jessie Dobson and Sir Cecil Wakeley, Churchill Livingstone; Sir Arthur Keith, Autobiography, C. A. Watts; Period Piece by Gwen Raverat, Faber and Faber; The World That Fred Made by Bernard Darwin, Chatto and Windus; Darwin's Victorian Malady by J. S. Winslow and other MSS., The American Philosophical Society; Darwin's Autobiography, ed. Nora Barlow, Collins; Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle, Everyman ed., J. M. Dent and Sons; Darwin Revalued by Arthur Keith, C. A. Watts; A History of Darwin's Parish by O. J. R. and Eleanor K. Howarth, Russell and Co.; The Old Road by Hilaire Belloc, Constable; A Short History of the English People by J. R. Green, J. M. Dent and Sons; The Reception of Darwin's Origin of Species by Russian Scientists by J. A. Rogers in Isis, The History of Science Society; and the Editor of the New Statesman.

Finally I should like to thank The Curwen Press for their invariable co-operation and valuable advice.

Down House

July 1974

Royalties from the sale of this book will be devoted to the upkeep of The Down House Museum and Estate as a memorial to Charles Darwin

[page] 7

CHAPTER I

THE LAND, THE VILLAGE AND THE HOUSE

Choose one of the first few days of June, the evening is the best time when the sun is setting behind the lime trees; the house-martins are dipping and swerving in their ravenous scoops for insects which hang almost motionless in the still air and the sweet smell of nicotiana drifts across the lawn. Go out by the french windows of the drawing-room, through the verandah and across the lawn to rest on the garden seat under the yews. At the far end of the orchard the tracery of a Scots pine is etched against the evening sky; beyond the garden in the Home Meadow a herd of young bullocks crop lazily at the rich grass; a cuckoo is declaring the close of day and the countryside settles for repose.

Beyond the meadow, and partly hidden by a row of beech and hawthorn, the chalk-hills of the North Downs roll away towards the south, solid, enduring and seemingly as ageless as if they had been there for ever! For ever? This is far from being the case. Let us, as we muse under the yew trees, go back to the beginning. Well, not quite to the beginning, not 4500 million years when the world was first created, but let us undertake a more modest imaginative exercise let us go back a mere hundred and forty million years.

Around us the flat, luxuriant countryside would be covered by conifers, ferns and cycads, and browsing amongst them, together with other reptiles, is the giant Iguanodon squatting on its thick tail and two hind legs which formed a tripod from which it reached up to seize food from the branches of the fir trees with its short fore-limbs. Instead of house-martins we might see the last of the huge, toothed feathered bird, the archaeopteryx, gliding from the treetops and flapping away over the marshy ground towards a great delta with many distributaries flowing where the Weald of Kent now is. This delta was part of a still larger freshwater system draining into a sea which covered the Low Countries of Northern Europe.

In another twenty-five million years the scene has changed; a vast sea covers the land where we have been letting our imagination roam, a sea which spread over Northern Europe and into Russia as far as the Ural mountains.

More than forty million years were to pass before this sea was driven out by an uprising of the land and in the meanwhile, in successive stages, marine deposits were laid down of sand and clay and finally chalk. Thrusting up of the crust of the earth more than fifty million years later, during the Miocene, caused a great elongated mound to arise, the remains of which now run across the counties of Sussex and Kent to form the North and South Downs. In time the summit of the chalk-covered range was gradually eroded exposing successive layers of sand and clay until the old freshwater Wealden deposits, over which the archaeopteryx flew so long ago, were exposed to the light of day.

At some stage, before this erosion had split off the North from the South Downs,

[page] 8

subsidiary valleys running northwards from the North Downs were carved out. Darwin thought that these valleys were the remnants of the bays of some primaeval sea, but it is now almost certain that they were scoured out by torrents flowing down from the snow-covered heights to the south during one of several cold periods. Eventually the summit of the North Downs and its northward running spurs was capped by clay with flint due to the dissolution of the surface chalk and admixture by slow chemical reaction with other materials. The high land between the subsidiary valleys later became covered with brushwood, hawthorn and beech, known locally as "shaws", and it is on one of these spurs that the village of Down came to be built.

But the air is getting chill, the bats have replaced the house-martins; the owl's hooting, the cuckoo's song and, with the lights going on in the house, it is time to return indoors and to pursue a little further the story of this part of the country in the more factual and less fancy-provoking atmosphere of the library. If we assume that every second of the journey from the garden to the library represents the passage of a million years, we would arrive there at the beginning of what is known as the Pleistocene era about one and a half million years ago and very glad we would be to get indoors. The Pleistocene corresponds roughly to the four great ice ages, the last of which ended 10,000 years ago. The British Isles land mass was joined to the Continent and, although the sheet ice stopped short at what is now the Thames Valley, the garden had we lingered there would have been bitterly cold. The appearance of the landscape would have changed to tundra, over which a few species of animals ventured such as elk, wolf, fox and beaver. Man-like creatures, even early representatives of Homo Sapiens, had evolved and the more daring would have approached the very edge of the ice.

Figure 1: Section through the North and South Downs

[page] 9

We do not know when man first came to what is now the county of Kent; perhaps during the first warm interglacial period; certainly in the second of the warm periods known as the Hoxnian there was a migration over these lands, as a cranium has been recovered at Swanscombe within twenty miles of Down which belonged to a 'human' female living over 300,000 years ago in the middle of the Hoxnian period. The countryside then would be dotted with pine, oak and yews, viburnum, hazel and euphorbia; and sharing the living space with Swanscombe man were the straight-tusked elephant, rhinoceros, deer, cave bear, giant beaver, lemming and the rare, massive cave lion. Following the Hoxnian warm period there were two more ice ages separated by another warm period during which the ice advanced and receded, then advanced again to recede finally between 10,000 and 8000 B.C. How far human migration occurred during the third warm period lasting until 55,000 B.C. we do not know. Neanderthal man, with many of the same animals which migrated north during the Hoxnian, now accompanied by bison, hippopotamus and wild cat must have wandered over the countryside amongst the pine, oak, alder, sycamore and hornbeam, because remains of his flint implements can be found to record his presence.

Towards the end of the fourth and last ice age, as the ice melted and the sea-level rose, the British Isles became separated from the Continent.

From about 35,000 B.C. a new race of modern man, Homo Sapiens, migrated northwards probably from Asia or Africa as the climate became progressively more temperate and mingled with Neanderthal man eventually displacing him from his caves and rock ledges so that this race seems to have been entirely obliterated.

It is not, however, until the end of the Pleistocene when, as far as we are concerned, the ice ages were all over that settlements in the county of Kent were established.

In about 10,000 B.C. a new race, Neolithic, or late Stone Age man, spread into Europe and eventually crossed the English Channel into Britain.

Between 2200 B.C. and 1600 B.C. elaborate erections such as those at Stonehenge and Avebury attested an advancing civilisation. A regular traffic by sea from the Continent to link up with the Cornish tin mines and for purposes of trade was established and consequent upon this was the founding of ancient centres at Canterbury and Winchester.

Inevitably a road or track must have existed for many centuries between these two centres of civilisation, and what better pathway than the North Downs which spanned most of the 128 miles between them? This track runs along the site of the present road from Winchester to Farnham and thereafter, until within sight of Canterbury, it takes to the North Downs. Here its course lies just below the summit of the south face, sometimes dipping down to the upper green-sand, but for most of the hundred miles from Farnham to Canterbury on good solid chalk. Since the death and martyrdom of Thomas à Becket this ancient road has been called the Pilgrims' Way because it was along this same path that the pilgrims from the West Country wound their way to the tomb of St. Thomas the Martyr. But for us at this stage it is the road along which Neolithic man trudged with his heavily-laden oxen to the markets of Winchester and Canterbury. At first their load would be the products of the farm, but from about 2000 B.C. they would carry first pots and pans made of bronze and perhaps, nearly a thousand years later, farm

[page] 10

implements made of iron. Only a few miles to the north of this old road and near the top of the more gently sloping north face of the Downs there are the remains of a fine Iron Age earthwork almost on the site of the present village of Down. We may perhaps be allowed to imagine this community living relatively peacefully for a hundred or more years following their various avocations and surrounded by prosperous farms. Like a modern village which has been bypassed by a motorway, they were a secluded community, yet within easy reach of the thoroughfare over the brow of the hill to the south.

The next 3000 years see the Romans come and go; Jutes, Angles and Saxons swarm over the island, and in the early part of the ninth century A.D. the Danes invaded the country. They were at one time sturdily resisted by Alfred, King of the West Saxons.

Alfred was a soldier, a scholar and a fine administrator, so that his Kingdom became settled and prosperous. The Danes, however, finally prevailed over the Saxons early in the eleventh century under their great King Canute, who in 1016 came to rule over all England, Denmark and Norway. At his death the realm of England passed to his son Harold I. This king has some relevance to the story of Down. His great-aunt Elgida married Ranulph of Mannheim, Count Palatine, in the tenth century and Ranulph was granted land at Down. Local tradition has it that he is the first in a line of Mannings (from Mannheim) who, as will presently be related, were holders of the manor of Down until 1560 and were the most important landowners in this part of the county.

In 1066 another race of Norsemen, who in 911 had occupied Normandy under their appropriately named leader, Rolf the Ganger, and had developed their own language over the centuries, crossed the channel and defeated Harold II at the battle of Senlac near Hastings.

The general scene having been set, we must "cone down", as the modern phrase has it, exclusively on that small village which was to be the home of England's greatest biological scientist.

Within a mile south-west of the old Iron Age or Roman Camp four roads meet, those from Bromley, Orpington, Cudham and Biggin Hill. These roads or lanes probably existed for centuries before the Norman Conquest and at their confluence there was a settlement from prehistoric times, the village of Down. Around this settlement as the centre, according to Norman custom, fields radiated to all points of the compass by which they were known. Thus, at Down we still have Westfield orientated in this direction from the centre of the village. The acreage of these fields was measured by the Jugum or yoke, being that amount of land that could be cultivated by a yoke of oxen.

Dr. and Mrs. Howarth, from whose scholarly work1 much of the material in this chapter is taken, picture the scene at this time as consisting of a huddle of one-storey timber huts with walls made of branches mixed with clay. At some distance from the centre would be the common land, shared by the villagers for grazing their cattle and, on the periphery of the clearing in the as yet uncut woods, timber for fuel. Here in season the villagers would shake the oak trees for acorns for their pigs, which were cared for by a communal swineherd.

There is no mention of Down in Domesday Book (1068), but in the monastic Registrum Roffense at Rochester it is related how Anselm (Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to

[page] 11

1109) assigned the title of Duna to the Bishop of Rochester and this was confirmed in the Custumale Roffense about the year 1300.

In 1291 Prior Henry built a new chapel in the manor of Orpington and this was almost certainly the origin of the present church at Down, which for many centuries was a chapel first of Orpington and then of Hayes, becoming "a church" only in the nineteenth century (Pl. II). This chapel was built for £60 and must have been somewhat austere and gloomy.2 It consisted of a single flint structure without aisles and the massive walls were pierced by tiny lancet windows, one of which happily survives to the east of the present porch. Subsequently early English builders put in fresh windows in fourteenth-century style and built the tower. There are now six bells in this tower, the three remaining old bells having been cast by William Dawe of London (1385—1418).

In 1287 there is the first reference to the transfer of land from Henry Southwood to John de la Dune (alias Atte Doune). It will be observed3 that at this date the village was liable to be spelt according to fancy and many references give the name a final 'e' as here. Nevertheless, once the spelling had been formalised, it was spelt Down (without an 'e') until the middle of the nineteenth century, and it is this spelling which will be adhered to until the last section of the book, when the modern spelling of 'Downe' will be adopted. Nevertheless, in accordance with the independent spirit of the Darwin family, the house will still be known as Down House as it is today. The land conveyed to John Atte Doune was almost certainly the piece of land upon which the manor house of the village, Down Court, was built. This house was probably moated as the disposition of the present ponds attests. Other houses as they sprang up were named after their first

Figure 2: Plan of the Village of Down

[page] 12

owners—Petley's, Trowmer's and Goddards, and the first two retain their original names today, but Goddards has been converted into Down Hall. A document in the Chapter library at Canterbury dated about 1470 and headed "Downe Rent and Customys" mention Petle and Trogmere (Trowmer) as rent payers, presumably to the manor (Fig. 2).

A picture of life in the Middle Ages at Down is presented to us by the system of frankpledge, whereby a community was responsible for the misdemeanours of its fellows. Frankpledge was maintained by a sheriff and ten tithingmen of responsibility, and the activities of this little court are preserved in the Public Record Office in Orpington. From there we learn that there was a fight between Richard Ferdying (of Farthing Street, a neighbouring village) and John Upstrete, each accusing the other of assault. Also eight women in Down "broke the assize" by brewing ale.4

In 1503 Mistress Wyndesoner was arraigned pro quarteria brasiatrix et tipulatrix, that is for brewing and selling beer, on four occasions; and Alicia Austen was similarly had up, this time with a fine disregard for gender pro tria tipulator bere, the latin for beer having been too much for the clerk. In the same year Geoffrey Pope stole a bill-hook from William Pettley gesam vocatam a byll.

In 1508 a grand jury made inquisition on one Stephen Gabell because, contra formam statuti, not being in possession of land worth forty shillings, he kept a ferret!5 No doubt the jurors were chiefly concerned with what Stephen did with his ferret.

During the reign of Henry VII frankpledge fell into disuse, although stocks were kept up against the church wall until 1826, so that for the future "goings-on" in the village we turn to the Church Register. All deaths occurring in the parish were entered, together with the cause, if known. Thus, we learn that in 1589 Thomas Doer broke his neck by falling down Mr. Maninge's well, and in 1601 Henry Maninge had the misfortune to be killed by a hatchet. Considering the importance of the Manning family, this must have caused quite a stir in the village; perhaps it was a family affair and was hushed up. Other entries mentioned were "overthrown from a cart", "horse falling on him" and suchlike hazards of the countryside. Suicides were denied a Christian burial and Richard Owsley qui se laqueo (by a noose) suspendebat was interred without ceremony. There is a gravestone in memory of an Owsley now in the village churchyard, but the stone is so badly worn that the date is impossible to decipher. During the Commonwealth the entries in the register were not kept up, but from 1672 they once more constitute an important record. At that time the infant mortality, the classic measure of general health standards in a community, was seventy-three per thousand. As the infant mortality for Great Britain in 1931 was sixty-six per thousand, this argues a good standard of health in the village.

Fig. 3 gives an extract from the family trees of some of the important inhabitants of Down. To have given the complete genealogy would have been unhelpful and, considering that some of the bearers of the names mentioned had up to fifteen children, impossible in the space available. Furthermore, the practice of placing children in the order of their ages has not necessarily been followed, as this is not always known.

It would be tedious to recite what is known about all the samples selected from the family trees, but we may pick out a few of these characters for special mention.

[page] 13

Figure 3: Family Tree of some Down notables

[page] 14

From about 940 A.D., when Ranulph of Mannheim married the Saxon Lady Elgida and was granted land at Down, as has been recorded previously, the Manning family was, until the middle of the seventeenth century, the principal one in the neighbourhood.6

Henry Manning, who lived in the manor house Down Court until 1560, was Knight Marshal or Marshal of the Household under Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth.

Henry's daughter Margaret was baptized at Down in 1559 before Henry moved away and it is thought that Queen Elizabeth herself may have attended the baptism. Elizabeth frequently went "a-maying" in the neighbourhood of Lewisham. She enjoyed the Kentish countryside and she may well have wished to attend a family occasion of her Marshal of the Household; at least the entry in the Parish Register records that this ceremony took place "after ye Queene's visitation".

In the seventeenth century some members of the Manning family emigrated to America and there is a Manning Association in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which exists primarily to trace connections with the Manning family and to exchange Manning gossip.

Jacob Verzellini was a fugitive Venetian who had set up a glass-making factory in Crutched Friars in the City of London, where he was granted a monopoly for the making of drinking glasses. He was the first to use soda ash made from seaweed instead of the crude potash from wood or fern ash. When Henry Manning left for Greenwich in 1560, Verzellini bought Down Court and subsequently came to own much land at Down, Keston and Hayes. Three pieces of Verzellini glass are known to exist. One, the so-called "Queen Elizabeth's glass", is in a leather case at Windsor Castle; a round tankard with silver and enamel mounts which once belonged to Lord Burghley is now in the British Museum, and a third is of unadvertised whereabouts. A fourth was dropped and broken at an auction sale.

Verzellini left £20 for a marble stone, now to be seen on the floor of Down Church embellished with the brass figures of himself and his wife with their family below.

Two other families remain to be mentioned, the Petleys and the Sandys. Richard Petley first came to Down in the thirteenth century and there is a record of a transaction involving the conveyance of land in 1297 to William de Petteleys. From the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries the Petley family rivalled the Mannings in the extent of their domain. Much of this came into the hands of the Manning family when John Manning married Agnes Petley in the early part of the sixteenth century. A John "Petle" is notable in that he was one of the eight inhabitants of Down who took part in Jack Cade's rebellion in 1450.

In the sixteenth century Henry Manning sold Down Hall to Sir Frances Carew and it eventually passed to Colonel Richard Sandys, son of Sir Edwin Sandys, and grandson of an archbishop. Richard Sandys of Down Hall was a colonel in the Parliamentary Army during the Civil War and in 1647 became a Governor of the prosperous Bermuda Company. After his death the Hall passed to his son Henry, who married the remarkable Katherine, daughter of Sir William St. Quentin of Yorkshire. This indomitable lady was successively the wife of Sir George Wentworth, Sir John Kaye (as his third wife), Henry Sandys and, at the age of 90 (some historians say 96), the 8th Earl of Eglingtoun, who was

[page] 15

| 1651 | Thomas Manning | (Property sold to John Know the elder, yeoman for £345) | |

| 1653 | Roger Know (son of John Know; m. 1654) | ||

| Thomas Know (b. 1658, d. 1728) | |||

| Roger Know (d. 1736) | |||

| (Property descended by gavelkind to his cousins) | |||

| 1748 | John Know Bartholomew | ||

| Leonard Bartholomew (d. 1757) | |||

| (brothers) | (Property conveyed by Leonard Bartholomew the surviving brother for £800) | ||

| 1751 | Charles Hayes of Hatton Garden | ||

| (Property descended to wife's family—the Cales) | |||

| 1759 | John Cale (landowner) | ||

| (Property descended to the heirs of his nearest relative, Thomas Prowse, M.P. for Somerset) | |||

| 1777 | Lady Mordaunt | ||

| Mary Prowse | |||

| (sisters) | (Property sold for £780–18–0) | ||

| 1778 | George Butler, esquire (landowner) | (Built the present house; | |

| (and George Richards of New Inn, gentleman) | son sold property for £1230) | ||

| 1791 | Cholmely Dering | ||

| (and Joseph Yates, Foster Brown & | |||

| Hon. Henry Legge) | (Property sold for £1660) | ||

| 1801 | Thomas Askew | ||

| (Property sold for £2280) | |||

| 1818 | Nathaniel Godbold | ||

| (a property speculator of Fulham) | (Property sold for £2750) | ||

| 1819 | Col. John Johnson | ||

| (Property sold for £1425) | |||

| 1837 | Rev. J. Drummond | ||

| (Property sold for £2020) | |||

| 1842 | Charles Darwin | ||

| Table 1 | Thomas Askew and the Rev. J. Drummond are thought to have laid out considerable sums of money on the estate | ||

| The Owners of Down House |

[page] 16

himself over 70. The wedding took place at St. Bride's, off Fleet Street, but the occasion was so unusual that in 1698 it found a place in the records of Down Parish Register as "an interesting event". She died after two more years of connubial bliss and is buried at Down. The Scottish antiquary Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe observes that, "Alas there is no portrait of her known—which is a sad pity, considering her remarkable conquests". After Henry's grandson married a distant cousin, Priscilla Sandys, the family retired to their Northbourne estates and Down knew the Sandys no more.

In 1651 Thomas Manning sold the land upon which Down House now stands to John Know, "Yeoman". The price paid for the property was £345 and it has been argued that this sum was too small if a house had been included and that John Know purchased only a tract of land. However, various pieces of evidence suggest otherwise. In the first place the area of the land involved was little more than ten acres in extent and £34 an acre would have been an absurdly high price to pay for land in those days; furthermore, over a hundred years later the land, together with a house, which may well have been improved, fetched only £780.

We know from the deeds that John Know the elder lived in a house on this property which he gave to his son Roger in 1653, probably as a wedding present, as Roger married the following year. Unless John Know built a house on the land in the short interval between 1651 and 1653, which, from the structure of the oldest part of the present house, seems very unlikely, we must presume that he bought a house with the property.

We can only speculate what this house was like. A small part of the present house is of this period, and in one surviving room a window has been bricked up to avoid the window tax, introduced in 1695.

John Know is described as a yeoman and no doubt his son Roger was a farmer. In various excavations for structural purposes during the last twenty years remains of old farm buildings have been turned up.

For the next hundred years the story of the house was probably a peaceful one, the property passing to various members of the Know family (Table I). The Bartholomew brothers inherited Down by gavelkind, whereby the property of a man dying intestate was divided equally amongst his immediate relatives. This sometimes led to quite awkward situations. For instance, one son or daughter might own the living room and two bedrooms of a house, another the remaining rooms including the kitchen, and a third the entrance hall and garden! Fortunately, at about the time of the transfer of Down House to the Bartholomews, the elder brother, John Know Bartholomew, died and Leonard was left as the sole owner. The system of gavelkind survived in Kent long after it had been abolished by law elsewhere. The system prevailed all over England until the Norman Conquest, when William the Conqueror substituted the feudal system of primogeniture. It is told that immediately after the Battle of Hastings some men of Kent surrounded William with leaf-bearing branches of trees and so behind this moving camouflage he escaped with his life. In return for this the King allowed gavelkind to persist in Kent and it survived until the twentieth century in this county, a doubtful reward one might think!

It is not certain how many of the succeeding owners lived in Down House. Charles

[page] 17

Hayes of Hatton Garden sounds a prosperous sort of person, and we know that John Cale was an extensive landowner, so that they might not have relished living in a humble farmhouse. The Mordaunt and Prowse family handed the property on as soon as they inherited it and so it came into the hands of Mr. George Butler in 1778.

George Butler was a wealthy business man and large landowner. It is almost certainly he who built the present house with the exception of the north-west wing which was added by Darwin, and from then on, except for the speculator Nathaniel Godbold who made a quick sale and tolerable profit, the owners resided in the house.

Thomas Askew is thought to have laid out considerable sums of money on the house and the estate so that in the seventeen years of his occupancy the value of the property increased from £1160 to £2280. After Nathaniel Godbold had made his little 'killing' the house and grounds came into the hands of Lt. Col. John Johnson in 1819.

I am indebted to Lt. Col. Johnson's great-grandson, Mr. Keith Dalton, of Toronto, for an account of this interesting owner of the Down House estate.

"Lieut. Col. John Johnson, C.B., the father of William Arthur Johnson, was of English birth (1768), educated in France, and had gone to India at an early age to join the Bombay Engineers. He had served for many years as a military engineer and surveyor at various posts and in most of the campaigns of that period. For part of this time he was aide-de-camp to the first Duke of Wellington, Sir Arthur Wellesley. Col. Johnson was a capable artist of water-colour painting and sketched well. He married Dederika Memlincke, a member of a famous family of artists of that day.

In 1835 Col. Johnson visited Canada to establish ownership of an area of land he had purchased in the Township of Dunn on the north shore of Lake Erie (and) William, then twenty-one years of age, came with him."

Following the departure of Col. Johnson and his family to Canada, Down House became the property of the Rev. J. Drummond, Vicar of Down, and it was he who sold the property to Charles Darwin in 1842.

[page] 18

CHAPTER II

THE HOUSE AND GARDEN

In 1836 Charles Darwin returned from his epoch-making voyage round the world on the Beagle. He had set off from Plymouth in December 1831, a young man aged twenty-two, having just come down from Cambridge.

The story of how he came to make this voyage has often been told and need not concern us here in any detail except to recall that it was 'touch and go' whether he went at all. First his father, the redoubtable Dr. Robert Waring Darwin, objected to his son wasting any more of his time on such a profitless adventure, an objection which was only overcome by the tactful intervention of Charles' uncle, Josiah Wedgwood; and then by the doubts in regard to his suitability entertained by the master of the Beagle, Captain FitzRoy, who judged a man's character by the shape of his nose and was at first dissatisfied with this feature of Darwin's physiognomy, but later was prepared to take a chance and agreed to allow him to accompany the Beagle as official naturalist.

Professor Henslow, the botanist, originally suggested that Darwin was the man for the job and recognised in the somewhat feckless undergraduate, who spent most of his time at Cambridge collecting beetles and shooting, qualities of mind and character which were to mature and reveal themselves eventually in the person of the greatest natural philosopher of the age.

The voyage of the Beagle about which much has been written brought out the finest qualities in Darwin. As the Beagle ploughed through the chops of the channel towards the Bay of Biscay the hapless young man, unknown to the world with a smattering of knowledge of the coleoptera and an amateur geologist, was prostrated by seasickness, a disability which dogged him for the next five years. Sharing a cabin with Captain FitzRoy, Darwin took with him amongst other books the Bible and the first volume of Lyell's Principles of Geology, which had just been published. As the Beagle crossed the Atlantic and pursued its chequered course down the east coast of South America on its cartographical mission and especially when braving the fury of Cape Horn, the lad became a man. He became a man inspired by the wonder of natural phenomena; physically he was hardened by the rough life of the pampas and he learnt to devote himself unremittingly to the work which he had set himself to accomplish, however much he may have been handicapped by frequent bouts of seasickness.

Then, after the Beagle set sail across the Pacific from the west coast of South America, Darwin visited the Galapagos islands lying on the Equator 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador. There he observed the different species of animals and plants each apparently adapted to the varied conditions on the different islands, and there perhaps was born the idea of Darwin's great contribution to the theory of evolution—the Natural Selection of Favourable Variations—whereby species evolve from the pressures of environmental circumstances.

[page] 19

During the voyage Darwin had collected specimens of plants, insects and fossils, which were sent back to England as the occasion allowed. Prominent among these were the fossil remains of the giant sloth Megatherium, which revealed to his eyes what he had read in Lyell's book, namely the great antiquity of the earth and the extinction of species which had once roamed upon it. So, when the Beagle at last put in to Plymouth in October 1836, Darwin had established for himself a modest reputation in scientific circles. Almost at once he set about the fulfilment of his second great contribution which was to bear fruit twenty-three years later with the publication of The Origin of Species. This was to provide an accumulation of evidence in favour of the theory of evolution such that no reasonable man thereafter could deny the essential probity of the thesis.

At first, after visits to his home in Shrewsbury, to his uncle Josiah Wedgwood at Maer and to Cambridge, he settled in lodgings in Great Marlborough Street in London, where he remained until he got married.

Darwin undertook the adventure of marriage only after great deliberation in which passion apparently played little part and having made a sort of balance sheet "for" and "against" marriage. But if this was a somewhat calculated enterprise it resulted in forty-three years of great marital happiness and a family life of such serenity that he was sustained in his natural tranquillity against the attacks and abuse of the world outside, which at first was unable to digest his advanced scientific views set in opposition as they were to established and hallowed beliefs.

In January 1839 Darwin married uncle Josiah's daughter, his cousin Emma Wedgwood, and they came to live in London in Upper Gower Street in a house which was destroyed by the German bombing in the last war. Here the symptoms of Darwin's illness, which will be described in greater detail later, began to appear in an obtrusive form. He was not exactly lionised by London Society, but at least his considerable reputation meant that he was entertained by numbers of people interested in his adventures and in his work. He met Sir John Herschel the astronomer, the illustrious Humboldt, Sydney Smith, Macaulay, Grote, Carlyle, Babbage, Joseph Hooker, and of course Lyell. He also acted as secretary to the Geological Society, and all these activities as well as the task of writing up his account of the voyage of the Beagle proved too much for him. He became increasingly convinced that he and Emma must move away from London to some quiet place where he would be free from social distractions and the bustle of city life.

So it was that he came to live at Down House in the county of Kent. As early as 1840 Charles and Emma were becoming disenchanted with London life and they were thinking of moving to the country. There were, however, clearly some problems. Charles' father was opposed to the idea of buying a house in the country until the young couple had lived there for some years in order to see whether the neighbourhood suited them, but we find Charles, who was staying with his family in Shrewsbury, writing to his wife, who was visiting hers at Maer Hall, on July 3rd 1841: "…My father seems to like having me here; and he and the girls are very merry all day long. I have partly talked over the Doctor about my buying a house without living in the neighbourhood half-a-dozen years first."1

In the next few months Dr. Darwin clearly capitulated on this issue because Charles

[page] 20

and Emma devoted much time searching first for a suitable small estate in Surrey. The choice of Down, nevertheless, was rather the result of despair—than of actual preference; they were weary of house-hunting and the attractive points about Down seemed to outweigh its somewhat more obvious faults. It had at least one essential quality, quietness. Indeed it would have been difficult to find a more secluded place so near to London.

Charles was delighted with the countryside, so unlike what he had been accustomed to in the Midlands, and still more pleased with its extreme quietness and rusticity. It was not, however, quite so secluded a place as a writer in a German periodical made it out to be when he said that the house could be approached only by a mule-track!

By July 1842 the die had been cast and Charles took Emma down to see the property for the first time, staying the night in the village inn. In a letter to his sister Emily Catherine a day later he writes:

"My dear Cathy,

You must have been surprised at not having heard sooner about the house. Emma and I only returned yesterday afternoon from staying there [at the inn]. I will give you in detail, as my father would like, my opinion on it—Emma's slightly differs. Position about a quarter of a mile from a small village of Down in Kent sixteen miles from St. Paul's, eight miles and a half from station with many trains; which station is only 10 [miles] from London. I calculate we were two hours' journey from London Bridge. Westcroft [another house which they had considered] was one-and-threequarter [hours] from Vauxhall Bridge. Village about 40 houses with old walnut tree in middle where stands an old flint church and three ["roads" crossed out] lanes meet. Inhabitants very respectable; infant school; grown-up people great musicians; all touch their hats as in Wales, and sit at their open doors in evening; no ["thoroughfare" crossed out] high road leads through village. The little pot-house where we slept is a grocer's shop and the landlord is the carpenter. So you may guess the style of the village. There is one butcher and baker and post-office. A carrier goes weekly to London and calls anywhere for anything in London and takes anything anywhere. On the road to this village, on fine day scenery absolutely beautiful: from close to our house, views very distant and rather beautiful, but being situated on rather high table-land, has somewhat of desolate air. There is [a] most beautiful old farm-house [Downe Court] with great thatched barns and old stumps of oak trees, like those at Shelton, one field off. The charm of the place to me is that almost every field is intersected (as alas is our) by one or more foot-paths. I never saw so many walks in any other county. The country is extraordinary [sic] rural and quiet with narrow lanes and high hedges and hardly any ruts. It is really surprising to think London is only 16 miles off. The house stands very badly close to a tiny lane and near another man's field. Our field is 15 acres and flat, looking into flat-bottomed valley on both sides, but no view from drawing room [the present dining-room] which faces due South [S.W.] except over our flat field and bits of rather ugly distant horizon. Close in front [he means on the side away from the road] there are some old (very productive) cherry-trees, walnut trees, yew, Spanish chestnut, pear, old larch, scotch fir and silver fir and old mulberry make rather pretty group. They give the ground an old look, but not flourishing much also rather desolate. There are quinces and medlars and plums with

[page] 21

plenty of fruit and morello cherries, but few apples. The purple magnolia flowers against the house. There is a really fine beech in view in our hedge [the "elephant tree"]. The kitchen garden [not the present one, but probably a strip along the Luxted Road] is a detestable strip and the soil looks wretched from quantity of chalk flints, but I really believe it is productive. The hedges grow well all round our field and it is a noted piece of Hay-land. This year the crop was bad but was bought, as it stood for 2£ per acre. That is 30£, the purchaser getting it in. Last year it was sold for 45£, no manure put on in interval. Does not this sound well, ASK MY FATHER? Does the Mulberry and Majestic show it is very cold in winter, which I fear [?]. Tell Susan it is 9 miles from Knole Park, 6 from Westerham, seven from Seven-Oaks, at all which places I hear scenery is beautiful." (After referring once more to the flat-bottomed valleys and observing that the fields left fallow appear white from a dressing of chalk, the letter continues.) "House ugly, looks neither old nor new; walls two feet thick; windows rather small; lower story [sic] rather low; capital study 18 × 18. Dining room [now the "Erasmus Room"] can easily be added to is 21 × 15. Three stories [sic] plenty of bed-rooms. We could hold the Hensleighs [cousins] and you and Susan and Erasmus [brother Erasmus, not to be confused with Charles' famous grandfather] all together. House in good repair, Mr. Cresy a few years ago laid out for the owner 1500£ and made new roof. Water pipes over house and two bath rooms,* pretty good offices and good stalls … with cottage. House in good repair. I believe the price is about 2200£ and I have no doubt I shall get it for one year on lease first to try so that I shall do nothing to house at first. (last owner kept 3 cows, one horse and one donkey and sold some hay annually from the field). I have no doubt, if we complete purchase I shall at least save 1000£ over Westcroft or any other house.

Emma was at first a good-deal disappointed at the country round the house; the day was gloomy and cold with N.E. wind. She likes the actual field and house better than I; the house is just situated as she likes, not too near nor too far from other houses, but she thinks the country looks desolate. I think all chalk counties do, but I am used to Cambridgeshire which is ten times worse. Emma is rapidly coming round. She was dreadfully bad with toothache and headache in the evening, but coming back she was so delighted with the scenery for the first few miles from Down, that it has worked a great change in her. We go there again the first fine day Emma is able and we then finally settle what to do … The great astronomer Sir J. Lubbock owner of 3000 acres here is building a grand house [High Elms] a mile off. I believe he is very reserved [some illegible words follow] so I suspect he will be no catch and will never know us."2

The rest of the letter is missing.

As it turned out the friendship between Charles Darwin and Sir John Lubbock and with his son (also John), afterwards Lord Avebury, was one of the most agreeable episodes in all of their lives.

The idea of leasing Down House for a trial period of one year, which would have

* There is some confusion here; Gwen Raverat staying in the house at the turn of the century says that there were no bathrooms. There were probably small rooms where a hip-bath could be placed without making a mess. There were certainly no fixed baths and water, which was warmed up on the kitchen range, was carried to them in cans.

[page] 22

appealed to the cautious Dr. Darwin, must have been dropped. One may imagine that with the summer of 1842 lending a more agreeable and inviting aspect to the countryside, the young couple would be eager to enter into their property. Whatever the reason the purchase was completed with the aid of Dr. Darwin's money and the house became theirs for £2020.

On the 24th of September 1842 Charles Darwin and his wife Emma, together with their son William, aged three, and baby Anne, aged one, took possession of Down House, where they lived together for the next forty years and where Charles produced those monumental and seminal works which changed the face of biological science and made Down House famous all over the world.

In 1842 a coach drive of some twenty miles was the only means of access to Down; and even when the railways crept close to it, it was singularly out of the world, with nothing to suggest the neighbourhood of London, unless it were the thin haze of smoke that sometimes clouded the sky. Nowadays, with the operation of the Clean Air Act this disadvantage no longer obtains. The sky is natural, either clear or cloudy, depending upon the weather; and the fact that London is not far away can be completely forgotten. The noises are twentieth-century country noises. To the lowing of cattle and the 'clip clop' of horses from the nearby riding school may be added the sound of the relatively few passing cars and the inevitable aircraft. The latter, except over weekends when aeroplanes from the small flying club buzz around, are sufficiently high by the time they reach Down from Heathrow or Gatwick that their passage is hardly noticed.

Darwin's son Francis, who lived at Down for much of his life, described the village as standing in an angle between two of the larger high-roads of the county, one leading to Tonbridge and the other to Westerham and Edenbridge. It was cut off from the Weald by a line of steep chalk hills on the south, and an abrupt hill formed a barrier against encroachments from the side of London. The village communicated with the main lines of traffic only by stony, tortuous lanes and this still serves to preserve its retired character. Nor is it hard to believe, he tells us, in the smugglers and their strings of pack-horses making their way up from the lawless old villages of the Weald. The village stands 550 feet above sea-level and possesses a certain charm in the shaws or straggling strips of wood capping the chalky banks. The village in 1842 consisted of three or four hundred inhabitants living in cottages close by the small fourteenth-century flint church. It was a place, we are assured, where newcomers were seldom seen, and the names occurring far back in the old church registers were well known in the village and still are today. The smock-frock was not then quite extinct, though chiefly used as a ceremonial dress by the bearers at funerals; on Sundays some of the men wore purple or green smocks at church.3

The house stood a third of a mile from the village and was built, like so many houses of the eighteenth century (circa 1778) as near as possible to the road—a narrow lane winding away to the Westerham high-road. "In 1842 it was dull and unattractive enough; a square brick building of three storeys, covered with shabby whitewash and hanging tiles. The garden had none of the shrubberies or walls that now give shelter; it was overlooked from the lane and was open, bleak and desolate."

[page] 23

Figure 4: Plan of Down House

[page] 24

In 1843 and 1844 Charles surveyed his new domain in a little essay written at different times during those years which he entitled "The General Aspect". The first entry, dated May 15th 1843, concerns itself with the general shape of the countryside and speculation as to the geology of the flat-bottomed valleys, a matter which has been dealt with in a previous section. He very quickly made his acquaintance with the curious quilt of red clay with flints which caps the summit of the hills and coats the depths of the valleys, the origin of which has already been discussed, and he was fascinated by the shapes of these flints "like huge bones". He describes the different kinds of bushes in the hedgerows entwined by travellers' joy and the tree bryonies which distinguished the countryside from that of the country round his old home in Shropshire.

On June 25th he writes: "The clover … fields are now of the most beautiful pink and from the number of Hive Bees frequenting them, the humming noise is quite extraordinary. Their humming is rather deeper than the humming over head which has been continuous and loud during all these last hot days, over almost every field. The labourers here say it is made by 'air-bees' and one man seeing a wild bee in [a] flower, different from the kind, remarked that 'no doubt it is a air bee'. This noise is considered as a sign of settled fair weather."

The September entry once more returns to a consideration of the clay which he found in one place to be fourteen feet deep. The discovery of plants of the gentiana covered with abortive buds prompts an article for the Gardener's Chronicle, a publication to which he remained faithful all his life. He also remarks on the curious behaviour of some of the brambles in the garden where the "leeding" shoot is buried in the grass and covered with knobs, each knob developing a new shoot. He records finding an old nest of a golden crested wren fastened to the lower arm of a small fir tree.

In October the ladybirds invaded the house and gathered together in the corners of the rooms. He declared that he had never seen a swift in this part of the country, though nuthatches were common. Finally, in the section of "The General Aspect" of March 25th 1844 he writes: "The first period of vegetation and the banks are clothed with pale blue violets to an extent I have never seen equalled and with Primroses. A few days later some of the copses were beautifully enlivened by Ranunculus Auricomus, wood anemones and a white Stellaria. Subsequently [is he referring to the previous year or adding this note later?] large areas were brilliantly blue with blue bells [sic]. The flowers here are very beautiful and the number of flowers, together with the darkness of the blue of the common little Polygala almost equalled it to an alpine Gentian."

There were large tracts of woodland which were cut about every ten years, some of which were very ancient. Larks abounded and their songs were most agreeable to him; nightingales were common. "Judging from an odd cooing note, something like the purring of a cat, doves are very common in the woods."

Charles has once more become the true countryman and no doubt merits the entry in Bagshaw's Directory of 1847 under "Householders in Downe", "Darwin, Charles, farmer"!

One of the first undertakings was to lower the lane (which overlooked the house) by about two feet and to build a flint wall along that part of it which bordered the garden.

[Down House]

Plate I: Down House (Photo by Col. James Creedy)

[Down Chapel in 1786]

II: Down Chapel in 1786, now Downe Church (by courtesy of the Rev. Jack Harrison)

[page] 25

The earth thus excavated was used in making banks and mounds round the lawn; these were planted with evergreens, which gave the garden a sheltered character. These banks and mounds are still an interesting feature of the garden, but the energetic gardener who tries to plant shrubs such as azaleas, which now grace one of the banks, to the ruination of many a tine on his garden fork, is soon aware of the material from which the banks were made. The flint wall recently collapsed and has been replaced by one in the same pattern, but two feet higher so as to protect the garden from the bitter northerly winds of which Darwin himself was so conscious.

However, the creation of the banks and mounds and the subsequent modification was undertaken with enthusiasm by the family as a corporate enterprise. Writing to his sister Susan on September 3rd 1845, Darwin relates:

"We are now undertaking some great earthworks; making a new walk in the kitchen garden; and removing the mound under the yews, on which the evergreens we found did badly, and which Erasmus has always insisted, was a great blemish in hiding part of the field and the old Scotch firs. We are making a mound, which will be executed by all the family, viz, in front of the door out of the house [the old front door, see Fig. 4] between two of the lime trees. We find the winds from the N. intolerable, and we retain the view from the grass mound and in walking down to the orchard. It will make the place much snugger, though a great blemish till the evergreens grow on it. Erasmus has been of the utmost service in scheming and in actually working; making creases in the turf, striking circles, driving stakes and such jobs; he has tired me out several times."4

Other work was also undertaken. A grand scheme was the making of a schoolroom and two small bedrooms. The servants had complained to him of the nuisance of everything having to pass through the kitchen; and the butler's pantry was thought to be too small to be tidy. Charles felt that it was selfish making the house so luxurious for themselves and not sufficiently comfortable for the servants, so he was determined if possible to effect their wishes. He was clearly anxious what the 'Shrewsbury Conclave' (meaning, I am sure, his father) would think of all this extravagance, and in a letter to his family he declared that he sometimes thinks they are "following Walter Scott's road to ruin at a snail-like pace".

Other changes had, in the meanwhile, been undertaken. The house had been made to look neater by being covered with stucco, but the chief improvement effected (1843) was the building of a large bow extending up the side of the house. This became covered with a tangle of creepers, and pleasantly varied the south-west aspect.

During the next forty years various alterations were made, not only to the house, but to the garden and to the estate and these really were improvements. Indeed, there is no feature which was added by the Darwins which one could do without. The first of these was the famous Sandwalk round which Charles would walk, in later years accompanied by his dog Polly, and which he termed his "thinking path". The name 'Sandwalk' derived from a sandpit at the far end of the wood, the sand from which was used to dress the path.

The job of planting the trees and making the path was carried out in 1846 on a strip of land at the south corner of the field now known appropriately as the Home Meadow.

[page] 26

Howarth says that this wood was made by enlarging a pre-existing shaw, but this is unlikely as the trees are all about 120 years old and Francis Darwin states that the wood was planted in 1846 on a piece of pasture land laid down as grass in 1840. This piece of land was rented from their neighbour, Sir John Lubbock (the elder), with whom by this time, and contrary to his prediction, Charles had become friendly. It was planted with hazel, alder, lime, hornbeam, birch, privet and dogwood and with a long line of hollies all down the exposed side. Most of these trees are still to be found, including a particularly fine oak tree planted at that time which is an object of admiration by connoisseurs.

As we shall see later, the number of hours which he devoted to writing in his study were modest, but much of the real work, the brain work, was undertaken during these perambulations of the Sandwalk. Around this little wood he would stroll a variable number of times, depending upon his mood and the weather, between midday and one o'clock whenever he was at Down, which was most of the days of his life. The number of turns would be assessed beforehand and, rather like a cricket umpire counting the balls bowled in an over, the requisite number of flints would be placed at one corner of the walk, one being kicked away after each turn, and when all had gone he went back to lunch.

"Sometimes when alone," Francis says, "he stood still or walked stealthily to observe birds or beasts. It was on one of these occasions that some young squirrels, mistaking him for a tree, ran up his back and legs, while their mother barked at them in an agony from a nearby tree. He always found birds' nests even up to the last years of his life, and we, as children, considered that he had a special genius in this direction. In his quiet prowls he came across the less common birds, but I fancy he used to conceal it from me as a little boy because he observed the agony of mind which I endured at not having seen the siskin or goldfinch, or whatever it may have been. He used to tell us how, when he was creeping along in the 'Big Woods', he came upon a fox asleep in the daytime, which was so much astonished that it took a good stare at him before it ran off. A Spitz dog [a forerunner of Polly] which accompanied him showed no sign of excitement at the fox, and he used to end the story by wondering how the dog could have been so fainthearted."5

This feature of the estate, besides affording an opportunity for contemplation together with modest exercise for its creator, was an unending source of delight to his children and grandchildren, although it was rather alarming for little children.

His grand-daughter, Gwen Raverat, writes of her impressions as a little girl:

"Of all places at Down, the Sandwalk seemed most to belong to my grandfather. It was a path running round a little wood which he had planted himself; and it always seemed to be a very long way from the house. You went right to the farthest end of the kitchen garden, and then through a wooden door in the high hedge, which quite cut you off from human society. Here a fenced path ran along between two great lonely meadows, till you came to the wood. The path ran straight down the outside of the wood—the Light Side—till it came to a summer-house at the far end; it was very lonely there; to this day you cannot see a building anywhere, only woods and valleys. In the summer-house faint chalk drawings of diagrams could still be made out; they had been drawn by my father [Sir George Darwin] and uncle Frank as children. That made it romantic; but also, once,

[page] 27

when mercifully my father was there, there was a drunken tramp in the summer-house, and that made it dreadful.

The Light Side was ominous and solitary enough, but at the summer-house the path turned back and made a loop down the Dark Side, a mossy path, all among the trees, and that was truly terrifying. There were two or three great old trees beside the path, too, which were all right if some grown-up person were there, but much too impressive if one were alone. The Hollow Ash was mysterious enough; but the enormous beech, which we called the Elephant Tree, was quite awful. It had something like the head of a monstrous beast growing out of the trunk, where a branch had been cut off. I tried to think it merely grotesque and rather funny, in the daytime; but if I were alone near it, or sometimes in bed at night the face grew and grew until it became the mask of a kind of brutish ogre, huge, evil and prehistoric; a face which chased me down long dark passages and never quite caught me; a kind of pre-Disney horror. Altogether the Sand-walk was a dangerous place if you were alone.

One day Charles boasted that he had been all round the Sandwalk quite by himself; so naturally, as an elder sister, I had got to do so too. I took Billy (the baby brother) in the pram for company, and set off bravely enough; but my heart sank into my boots when the kitchen garden door banged behind me and shut me off from the civilized world. However, by whistling and singing and talking brightly to Billy, I got safely down the Light Side, and there was no tramp in the summer-house. But when I turned back down the Dark Side, the strangest rustlings and whisperings began to flit about all over the wood. I held my head up and walked along briskly, but the sighings and stirrings followed me as I went: and someone seemed to be saying something over and over again, something that I could not quite hear. There was a strange creaking noise too, and certainly footsteps following along behind me. I walked faster and faster until I was fairly running; and then absolutely galloping; the pram swayed madly from side to side, but by a miracle did not upset. At last, the hot breath of the pursuer on my very neck, I reached the blessed garden door; and after a short but most dangerous struggle, managed to wrench it open, got through alive, and fairly slammed it after me. I never told anyone of the perils I had passed through. I was not proud of this adventure.

All the same, when there were grown-ups about to make it safe, I loved the Sand-walk; I used to crawl on all fours through the undergrowth for the whole length of the wood, worshipping every leaf and bramble as I went. In the very middle there was the secret clay-pit where we grubbed up the red clay, and rolled it in our handkerchiefs, and tried to make little pots to bake on the bars of the nursery grate; which were not a success. And, under protection, I would even dare to climb right down inside the hollow ash. There is something extraordinarily moving about a hollow tree."6

Bernard Darwin (Gwen's cousin) says that the awesome quality of the hollow ash was due to a tramp having slept there and set it on fire so that it was all black inside. He says that the giant beech was called "Bismarck" or sometimes "The Rhinoceros". I can see what he means, but "The Elephant Tree" is really more suitable and the name is now sanctioned by universal usage. Alas! fungi with long names which it is easy to forget such as Polyporus Squamosus and Fomes Ulmarius, but which are also called somewhat

[page] 28

gruesomely "heart-rot" and "Brown Butt rot", so riddled this 400-year-old beech that, in 1969, it became dangerous and had to be cut down. It was, however, possible to preserve that part of the trunk containing the elephant's head, or if you like "Bismarck", but the glory of it has departed.

So the Sandwalk entered into the life of the Darwin family, but it was not until 1874 in a letter to Sir John Lubbock (the younger), dated February 23rd, that Charles wrote asking whether Sir John would be prepared to exchange "the little wood which I rent" amounting, as described in his customary precise manner, to "1 acre, 2 rods and 10 perches", for part of a field belonging to the Darwins of exactly the same size. The proffered strip, Lubbock was assured, was of considerably better quality of grazing, a point which one imagined hardly needed labouring as the Sandwalk strip was full of trees. After a bit of sparring between these now old friends and some doubt on the part of Sir John Lubbock as to whether the Sandwalk wood was not part of his marriage settlement, "in which case it would be difficult to deal with it till Johnnie is of age",7 the deal was concluded and the beloved Sandwalk became the property of the Darwins.

Today the Sandwalk is enjoyed by hundreds of visitors each year. In the early spring the ground beside the path on the Dark Side is sprinkled with celandine and later the whole wood is bright with bluebells and wood anemones, some primroses and, in June, occasional wild orchids. If only the children would refrain from picking the bluebells; they must all be nearly dead by the time they reach home, but I suppose the temptation is irresistible. Then, alongside the Sandwalk about four acres have been cut off the Home Meadow for a cricket ground and here on a summer day at the weekend there is the merry sound of bat on ball, punctuated at intervals by a furious "How's 'at".

Charles would have enjoyed that.

In the meanwhile other amenities had been acquired. In a letter to his son William dated May 3rd 1858 from the health centre at Moor Park, to which Darwin repaired from time to time, he writes, "I have been playing a good deal at billiards and have lately got up to my play and made some splendid strokes!"8 Billiards became an important source of recreation for Darwin and the following year (March 24th 1859) he writes to his cousin, W. D. Fox: "We have set up a billiard table, and I find it does me a deal of good and drives the horrid species out of my head"9 [The Origin of Species was published later that year]. This item of information, together with a letter to Hooker dated December 24th 1858, in which he states "My room (28 × 19) with divided room above, with all fixtures (and pointed), not furniture, and plastered outside, cost about £500",10 is the only evidence we have of the date when an important wing of the house was added. This is the drawing-room and the "Divided room" above it. The old drawing-room (Charles Darwin Room) now became the dining-room and the old dining-room was liberated no doubt for the billiard table, which could hardly have been accommodated elsewhere. The shape of the house must now have been somewhat curious with the front door facing north-west in an angle between the original house and the drawing-room (Fig. 4).

In September 1876 Charles is writing to a Mr. Marshall:

[page] 29

"I want some professional assistance in architecture, on a very small scale, if you are inclined to undertake the work. I wish to build this autumn, so as to be ready by early next summer, a billiard room (25ft × 21ft) attached to my house with a bedroom and drawing-room [sic] above." And he adds in a postscript, "As the winter is coming on there is no time to lose."11

So in 1877 the awkward angle in the plan of the house was filled in. The front door had to be moved to the end of the newly-created hall, where it now stands facing north-east and no doubt the portico was erected at the same time.

In 1872 as their daughter Henrietta writes:

"During the stay of three weeks at Sevenoaks they [Emma and Charles] became acquainted with the merits of a verandah, and this led to a large verandah with a glass roof, opening out of the drawing-room being made at Down. So much of all future life was carried on there, it is associated with such happy hours of talk and leisurely loitering, that it seems to us almost like a friend. The fine row of limes to the west sheltered it from the afternoon sun and we heard the hum of bees and smelt honey-sweet flowers as we sat there. The flower-beds and the dear old dial, by which in the old days my father regulated the clock, were in front and beyond the lawn, the field stretching to the South. Polly too appreciated it and became a familiar sight, lying curled up on one of the red cushions basking in the sun. After my marriage she adopted my father and trotted after him wherever he went, lying on his sofa on her own rug during working hours."12

The external form of the house was now complete virtually as we see it today. The kitchen garden, which we have noted was found to be unsatisfactory, was discarded, and a new kitchen garden was made from a strip taken from the Home Meadow. This, however, was not enough for Emma with her love of gardening nor for Charles with his botanical exercises and experiments.

On December 24th 1862 he writes to Joseph Hooker (his lifelong friend and champion, Curator of Kew Gardens): "And now I am going to tell you a most important piece of news!! I have almost resolved to build a small hot-house; my neighbour's first-rate gardener has suggested it, and offered to make me plans, and see that it is well done, and he is a really clever fellow, who wins a lot of prizes, and is very observant. He believes that we should succeed with a little patience; it will be a grand amusement for me to experiment with plants." And on February 5th 1863, "I write now because the new hot-house is ready, and I long to stock it, just like a schoolboy. Could you tell me pretty soon what plants you can give me; and then I shall know what to order? And do advise me how I had better get such plants as you can spare. Would it do to send my box-cart early in the morning, on a day that was not frosty, lining the cart with mats and arriving here before night? I have no idea whether this degree of exposure (and of course the cart would be cold) could injure Stove-plants; there would be about five hours (with wait) on the journey home."13

At about that time he writes to Sir John Lubbock, who died two years later:

"My dear Sir,

My little hot-house is finished and you must allow me once again to thank you sincerely for allowing Horwood to superintend the erection. Without his aid I should

[page] 30

never have had the spirit to undertake it; and if I had should probably have made a mess of it.

It will not only be an amusement to me, but will enable me to try many little experiments, which otherwise would have been impossible.

With sincere thanks,

My dear Sir

Yours sincerely obliged

Charles Darwin."14

Clearly by 1863 relations between Charles and his neighbour were still on a fairly formal basis, but they had known each other only twenty-one years and in those days familiarity blossomed slowly.

One last embellishment needs to be recorded. In the autumn of 1881, the year before Charles died, "a strip of field was bought to add to the garden beyond the orchard". The object was to have a hard tennis court, but the additional ground added greatly to the pleasantness of the gardens.

Emma was more enthusiastic about this than her children, and was "boiling over with schemes about the tennis court."