[map]

[page break]

A

CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY

OF THE

VOYAGES AND DISCOVERIES

IN THE

SOUTH SEA

OR

PACIFIC OCEAN.

PART III.

From the Year 1620, to the Year 1688.

ILLUSTRATED WITH CHARTS AND OTHER PLATES.

By JAMES BURNEY, 1750—1821.

CAPTAIN IN THE ROYAL NAVY.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY LUKE HANSARD AND SONS, NEAR LINCOLN'S-INN FIELDS; AND SOLD BY

G. AND W. NICOL, BOOKSELLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, AND T. PAYNE, PALL-MALL;

WILKIE AND ROBINSON, PATERNOSTER ROW; CADELL AND DAVIES, IN THE STRAND;

NORNAVILLE AND FELL, BOND-STREET; AND J. MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

1813.

[page break]

[page break]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME III.

CHAPTER I.

Voyage of the Nassau Fleet, to the South Sea, and to the East Indies.

| Page | |

| Fleet fitted out from Holland against Peru. Commanded by Jacob l'Heremite | 2 |

| Cape de Verde Islands | 3 |

| I. St Vincent, and St Antonio. Sierra Leone | 4 |

| C. Lopez Gonsalvo. Bad water | 5 |

| I. St Thomas. Annobon | 7 |

| In Strait Le Maire | 9 |

| Verschoor and Valentyn's Bay | 10 |

| Chart by Van Walbeck | ib. |

| Nassau Bay | 12 |

| Examination of the Coast round Nassau Bay. Description of the Inhabitants | 13—15 |

| Suarte Theunis | 17 |

| At Juan Fernandez | 18 |

| Failure of Attempt on Callao | 20 |

| Death of Jacob l'Heremite | 23 |

| Isle de Lima or de S. Lorenzo | 26 |

| Herbs found there | ib. |

| Guayaquil burnt | 27 |

| Islands Pescadores | 28 |

| Bay and good Watering place | ib. |

| Coast of New Spain | 30 |

| Occurrence at Port del Marques | 31 |

| Leave the American Coast | 32 |

| Islands and Reefs believed to be of San Bartolomé | 33 |

| At the Ladrones | 34 |

| Islands SW of the Ladrones | ib. |

| The Fleet arrives at the Molucca Islands | 35 |

| Death of Admiral Schapenham | 36 |

CHAP. II.

Of the early intercourse of Europeans with China, and their Settlements on the Island Formosa. Various other events to the year 1638.

| Page | |

| Settlement of the Portuguese at Macao | 39 |

| Formation of the Dutch East India Company | 40 |

| Contests of the Dutch with the Portuguese | ib. |

| The Ponghou Isles | 44 |

| Dutch War with the Chinese | ib. |

| They settle in Formosa | 48 |

| Harbour of Tayowan | ib. |

| Kelang | 49 |

| George Candidius | 50—52 |

| Death of W. Schouten | 53 |

| Spanish Ship wrecked at the Ladrones | ib. |

| Massacre of the Christians at Japan | ib. |

a

[page break]

CHAP. III.

Voyage of Captain Matthys Kwast to the Sea East of Japan.

CHAP. IV.

The Voyage of Captain Abel Jansen Tasman in the year 1642.

| Page | |

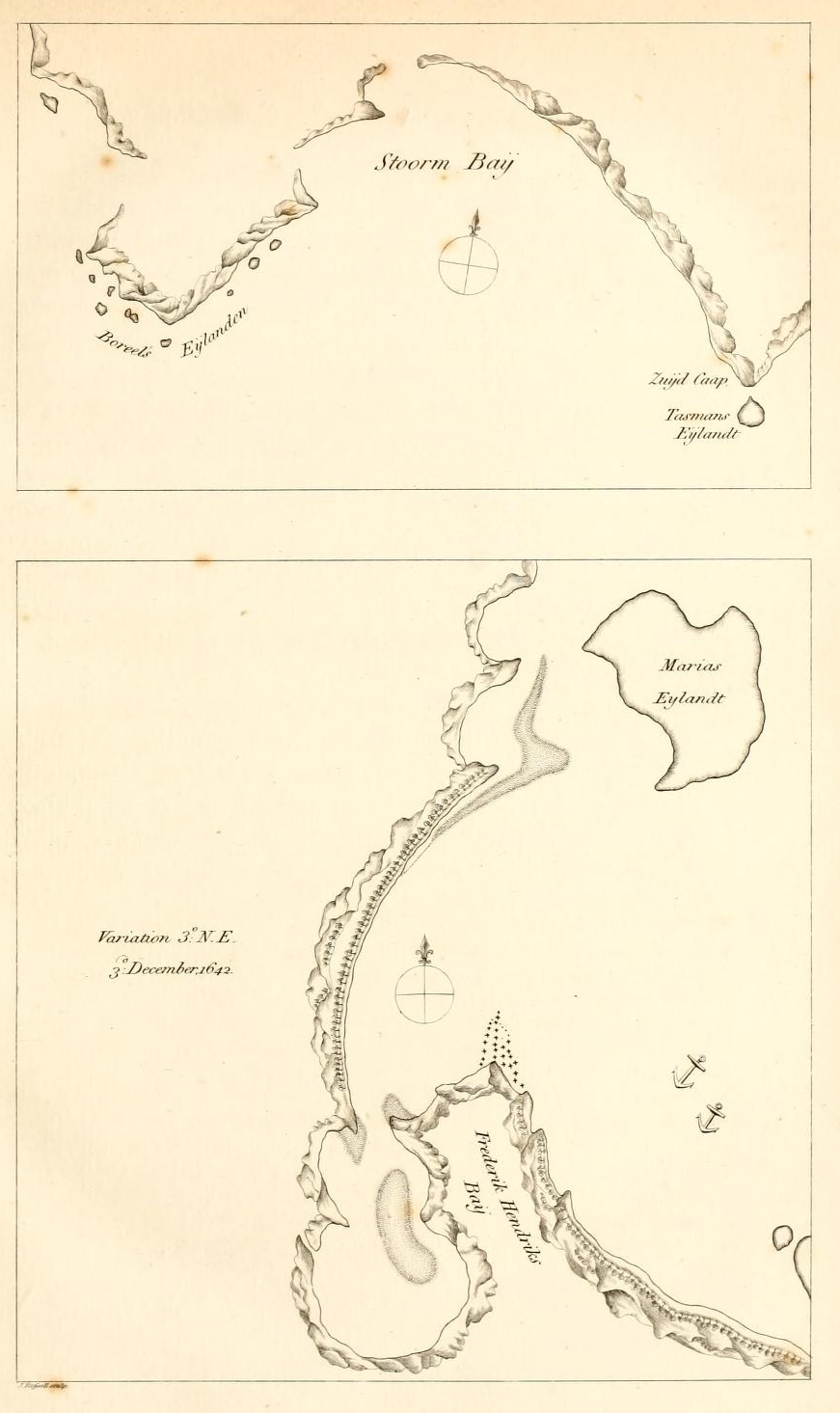

| Manuscript Journal of Captain Tasman's | 60 |

| Tasman sails from Batavia | 63 |

| At the Island Mauritius | ib. |

| Land discovered | 67 |

| Is named Van Diemen's Land | 68 |

| Frederik Hendrik's Bay | 70 |

| Other Land discovered, and named Staten Land [since, New Zealand] | 72 |

| Moordenaar's Bay | 73 |

| Drie Koningen Island | 79 |

| Pylstaart Island | 80 |

| Amsterdam Island | 81 |

| Amamocka Island | 86 |

| Island North of Amamocka | 89 |

| Prins Willem's Islands, and Heemskerk's Shoals | 89 |

| Onthona Java | 93 |

| Marquen Islands | 94 |

| Groehe Islands | 95 |

| Island St Jan | 96 |

| Ant. Kaan's Island. Cape Sta. Maria. Gerrit Denys Island. Vischer's Island | 97 |

| Salomon Sweert's Hoek | 99 |

| Coast of New Guinea | 100 |

| Vulcan's Island. Hooge Bergh | 102 |

| Islands Jamna and Arimoa | 103—4 |

| Islands Moa and Inson | 105 |

| Willem Schouten's Island | 107 |

| Return to Batavia | 110 |

CHAP. V.

Expedition of Hendrick Brouwer to Chili.

| Page | |

| Staten Land discovered to be an Island | 115 |

| Brouwer's Passage Eastward of Staten Island | 116 |

| Valentyn's Bay | ib. |

| At the Island Chiloe | 117 |

| Brouwer's Haven | 118 |

| Carel Mapu. Calibuco | 121 |

| The Llama or Peruvian Sheep | 122 |

| City of Castro | 124 |

| State of Chili | 126 |

| Death of Hendrick Brouwer | 129 |

| Island Donna Sebastiana | ib. |

| Of the name Puerto Ingles | 130 |

| Description of Brouwer's Haven | 131 |

| Inhabitants of Chiloe | ib. |

| Baldivia, City and River | 132 |

| Alliance formed between the Hollanders and People of Chili | 134 |

| Cawaw; a drink of the Chilese | 137 |

| Its similarity to the Kava of the South Sea Islands | 138—9 |

| The Hollanders depart from Chili | 144 |

| Passage East of Staten Land called Brouwer's Strait | 145 |

[page break]

CHAP. VI.

Voyage of the Ships Kastrikom and Breskens to the North of Japan.

| Page | |

| Of the knowledge previously obtained of Yesso and Eastern Tartary | 146 |

| The Ships Kastrikom and Breskens fitted out at Batavia | 150 |

| Publications concerning the Voyage | 151 |

| Instructions to the Commander | 152 |

| Ongelukkig Island | 154 |

| Land of Yesso | 155 |

| Staten Eylant | 156 |

| Compagnies Landt | ib. |

| Strait de Vries | ib. |

| Cape Van Patientee | 158 |

| Bay de Goede Hope | 159 |

| Description of Yesso, and the Inhabitants | ib. —165 |

| The Kastrikom in search of the Rich Islands | 166 |

| Course sailed by the Breskens | 167 |

| Port on the East side of Japan | 169 |

| Adventure of some Hollanders who landed there | 170—176 |

| Of Land seen by J. de Gama | 177 |

| Tristan d'Acunha Isles | ib. |

CHAP. VII.

Notices of a Second Voyage of Discovery by Tasman. Of the Amsterdam Stadt-house Map of the World; and of the Names Hollandia Nova and Zeelandia Nova.

| Page | |

| Second Voyage of Discovery by Tasman | 178 |

| Extract from his Instructions | 179 |

| Of the Name New Holland; on what occasion first applied to the Terra Australis | 181 |

| Amsterdam Stadt house Map of World | 181—182 |

| Zeelandia Nova | 183 |

CHAP. VIII.

Doubtful Relation of a Voyage by Bartholomew de Fonte.

| Page | |

| Time and manner of its first publication | 184 |

| Letter of de Fonte | 185—190 |

| Doubts respecting the reality of de Fonte's Voyage | 191 |

a 2

[page break]

CHAP. IX.

Brief Notice of the First entrance of the Russians into the Sea East of Asia. Narrative of the wreck of a Dutch Ship on the Island Quelpaert, and the captivity of her Crew in the Korea.

| Page | |

| First entrance of the Russians into the Sea East of Siberia | 196 |

| Dutch Ship wrecked on the Island Quelpaert | 197 |

| Narrative by Hendrick Hamel | 199—219 |

| His Description of the Kingdom of Korea | 219—227 |

| Remarks on Hamel's Description | 227 |

| Of the Korean and Chinese written characters | 230—236 |

CHAP. X.

Western Navigation from Europe to the East Indies. The Island Formosa taken from the Hollanders.

| Page | |

| Voyages of Jan Boon | 238 |

| Government of the Hollanders in Formosa | 240 |

| Are attacked by the Chinese | 249 |

| Fort Zealand besieged | 253 |

| Passage from the China Sea Southward against the Southern Monsoon | 254 |

| Succours arrive from Batavia | 256 |

| Fort Zealand surrendered to the Chinese General Koxinga | 261 |

| Of Koxinga and his Successors, Sovereigns of Formosa | 264—265 |

CHAP. XI.

Early instance of the use of Time Keepers at Sea. Of Islands marked in the Charts with the name Santa Tecla. Voyage of Jean Baptiste de la Follada.

| Page | |

| Account of the going of two Watches at Sea | 267 |

| Of the Islands Santa Tecla | 268 |

| J. Baptiste de la Follada | 269 |

| Fr. de Seyxas y Lovera | 270 |

[page break]

CHAP. XII.

Commencement of Missionary Undertakings to the Islands in the South Sea; and Settlement of the Ladrone Islands by the Spaniards.

| Page | |

| Mission to the Ladrones proposed by P. Luis de Sanvitores | 274 |

| Plan for a Mission to the Terra Australis by Abbé J. Paulmier | 275 |

| Of de Gonneville's Voyage | ib. |

| J. Paulmier, a descendant of Essemoric | 277 |

| Mission sent to the Ladrone Islands | 280 |

| Name of the Islands changed to that of the Marianas | 280 |

| The first Church built at Agadna | 284 |

| Pere Gobien; his Protestation | 286 |

| Unwillingness of the natives to be baptised | 288 |

| Forts built and the natives subjected | 289—292 |

| Padre de Sanvitores killed | 295 |

| 200 natives of the Philippines Islands ordered to strengthen the Mission | 297 |

| Severities exercised on the natives | 298 & seq. |

| Guahan abandoned by the greater part of the inhabitants | 300 |

| Don Ant. de Saravia appointed Governor; conciliates the natives and restores order | 300 |

| Death of Saravia | 302 |

| His Successors undertake the conquest of the Northern Isles | ib. |

| Eaton and Cowley, Buccaneers, at Guahan | 304—5 |

| Dampier, his description of the natives | 306 |

| Island named Carolina | 307 |

| Tyranny of the Spaniards. The Northern Isles wholly unpeopled and abandoned | 308 & seq. |

| Character and happy state of the natives at the first arrival of the Mission | 310 |

| Mismanagement of the Spaniards | 313—314 |

| Of the Chart of the Marianas by P. Alonso Lopez | 315 |

CHAP. XIII.

Voyage of Captain John Narbrough to Patagonia and Chili.

| Page | |

| Journals & Narratives of the Voyage | 316—318 |

| Letter from Captain Grenville Collins to M. Witsen | 319 |

| Journal kept by Capt. Narbrough | 320—371 |

| Cape de Verde Islands | 321 |

| Instructions to the Commander of the Bachelour | 323 |

| Seal's Bay. Spiring's Bay | 328 |

| Penguin Island | 329 |

| In Port Desire | ib. —338 |

| Watering places | 330—331 |

| Tower Rock | 336 |

| Bay before Port San Julian | 339 |

| In Port San Julian | 340 |

| Salt Pond | 342 |

| Natives | 343 |

| The Armadillo. The Huffer | 346 |

| Return to Port Desire | 346 |

| Figure of the Ship by the Natives | 347 |

| River Gallegos. Cape Virgin Mary | 348 |

| In the Strait of Magalhanes | 349—358 |

| Island Nuestra Sena del Socorro | 359 |

| Narbrough Island. Chiloe | 360 |

| No-man's Island | 361 |

| At Baldivia | ib. —369 |

| Description of the Port of Baldivia | 370 |

| Return to the Strait of Magalhanes | 371 |

| Tuesday Bay. Island Bay. Batchelor's River | ib. |

| Continuation of the narrative from Lieutenant Pecket's Journal | 372 |

| Remarks on the Voyage | 373—375 |

| Remarks on the different Charts of the Strait of Magalhanes | 376—382 |

[page break]

CHAP. XIV

Trading Voyages from Europe to the South Sea, by Strait le Maire. Attempt by the English East India company to re-establish their Trade with Japan. voyage of Thomas Peche to the Molucca and Philippine Islands, and in search of the Strait of Anian.

| Page | |

| Voyage of two Vessels from Holland to the South Sea | 383 |

| East Coast of Tierra del Fuego | ib. |

| Attempt made by the English to re-establish their Trade with Japan | 384—392 |

| Voyage of Thomas Peche | 392 |

| His search for the Strait of Anian | 393 |

| Publication of his Voyage | 394 |

CHAP. XV.

Voyage of Antonio de la Rochè. Discovery by the Japanese of the Island Bune-sima; with various other matters.

| Page | |

| Voyage of Antonio de la Rochè | 395—398 |

| He sails from Hamburgh | 396 |

| Sails on his return from the South Sea | 397 |

| Discovers Land to the East of Staten Island | ib. |

| La Rochè's Passage | ib. |

| Isla Grande of Ja Rochè | 398 |

| Doubts and conjectures concerning la Rochè's Discoveries | 399 & seq. |

| Island Buna-sima | 403 |

| Romance of a Voyage by Jaques Sadeur | ib. —404 |

CHAP. XVI.

Discoveries made by the Japanese to the North. Attempts of the Portuguese to renew their Trade with Japan. The name Carolinas given to Islands Southward of the Marianas. First Mission of the French Jesuits to China. Islas de 1688. Island Donna Maria de Lajara.

| Page | |

| Discoveries by the Japanese to the North of Japan | 405 |

| Japanese Ship wrecked near Macao | 406 |

| Attempts of the Portuguese to renew their trade with Japan | 407 |

| Carolinas Islands, or new Philippines | 410 |

| First introduction of the French Jesuits into China | 411 |

| Islas de 1688 | 412 |

| Island Donna Maria de Lajara | 413 |

[page break]

APPENDIX.

MEMOIR, Explanatory of a Chart of the Coast of China and the Sea Eastward, from the River of Canton to the Southern Islands of Japan.

(Being the Chart which fronts the Title page to this Volume).

| Page | |

| List of the Authorities on which the Chart is formed | 415 |

| Hessel Gerritz. Joannes Van Keulen | 419 |

| Coast of China | 420—425 |

| Missionary Survey | 420 |

| Chinese Maps of China | ib. |

| Korea | 426 |

| Quelpaert | 427 |

| Japanese Islands | 427 |

| Formosa | 429 |

| Banks of Formosa | 431 |

| Lieou Kieou Islands | ib. |

| Islands between the Lieou Kieou and Formosa | ib. |

| Channel between the Northern Bashee Islands and Formosa | 435 |

[page break]

LIST of the CHARTS and PLATES to VOL. III.

| Chart of the Coast of China and the Sea Eastward, from the River of Canton to the Southern Islands of Japan | To face the Title. |

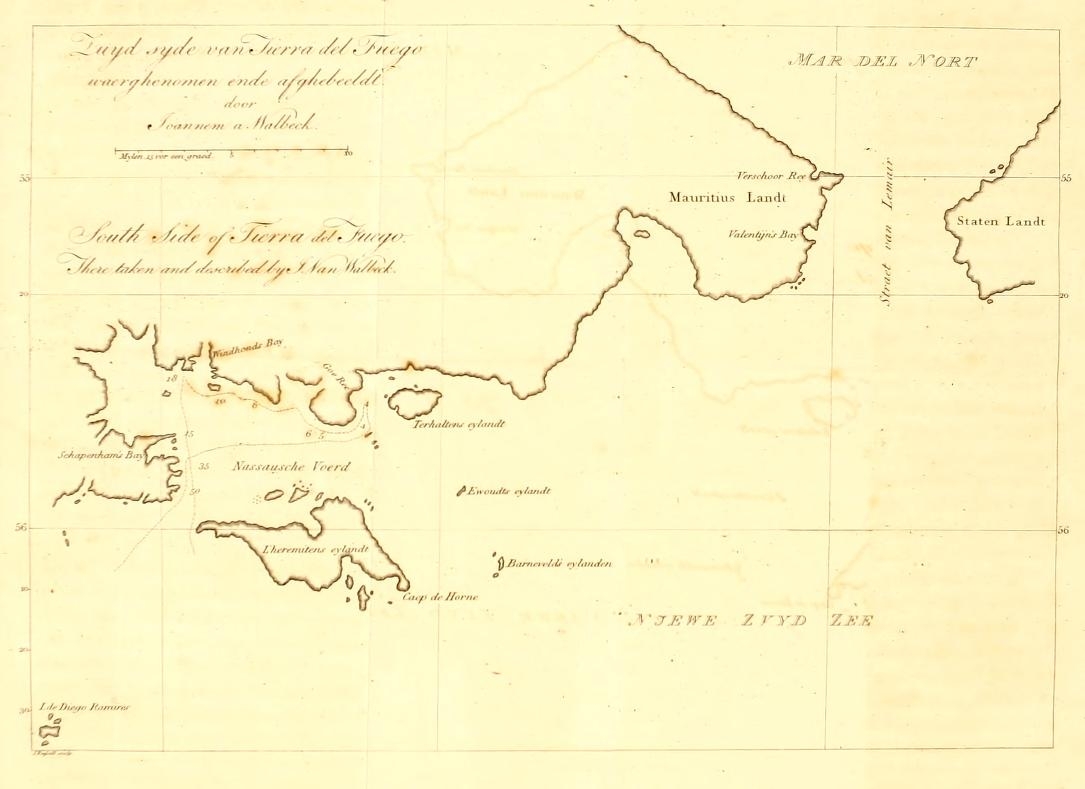

| Chart of the South side of Tierra del Fuego. By J. Van Walbeck. A.D. 1624 | To face page 9 |

| Chart of the Coast from Callao to the North of the Bay behind the Piscadores. From Journael Van de Nassausche Vloot. 1626 | 28 |

| The South East Port at the Island Mauritius. From Captain Abel Tasman's Manuscript Journal. 1642 | 64 |

| Chart of AntonŸ Van Diemen's Land. From the same | 67 |

| Stoorm BaŸ; and Frederik Hendrik's Bay | 70 |

| Chart of State-Land [New Zealand] | 73 |

| View in Moordenaar's Bay | 75 |

| Drie Koningen (or three King's) Island | 79 |

| Chart of Middleburgh, Amsterdam, and other Islands | 81 |

| Maria's Bay in Amsterdam Island | 85 |

| Views of Land near Cape Santa Maria | 97 |

| Appearance of the Coast at Salomon Sweert's Point, and of the Inhabitants | 99 |

| Islands, Moa and Insou | 106 |

| Golfo de Ankaos, or Chart of the North part of Chiloue. From Hendrick Brouwer's Voyagie. Edit. of 1646. | 119 |

| Chart of the Discoveries of the Kastrikom and Breskens. Copied from J. Jansen. 1658 | 155 |

| Views of Compagnies Landt; of Staten Eylant; and of Cape Van Patientie. From N. Witsen's N.& O. Tartarye. Edit. 1692 | 158 |

| The Marianas, or Ladrone Islands. From the Chart of Padre Alanso Lopez, Missionary; published by Gobien. 1700 | 293 |

| Captain John Narbrough's Chart of the Strait of Magalhanes. 1670 | 349 |

[page 1]

A

HISTORY

OF THE

DISCOVERIES

IN THE

SOUTH SEA.

CHAPTER I.

Voyage of the Nassau Fleet, to the SOUTH SEA, and to the. EAST INDIES.

CHAP. 1.

THE twelve years truce which had been agreed upon between Spain and the United Provinces, expired in 1621, and freed the subjects of both countries from the small portion of restraint to which some respect for a convention, never well observed, had made them submit. Vast plans were formed by the States of the United Provinces against the Spanish and Portuguese settlements in South America; Spain and Portugal being then united in subjection under one monarch. The views of the Dutch extended beyond purposes of plunder, to their more permanent aggrandisement in the acquisition of large and valuable territory, and in weakening a powerful enemy by dispossessing him of those sources of wealth which rendered him so formidable in Europe.

VOL. III. B

[page] 2

In the beginning of the year 1623, a Fleet was equipped, by order of the States General and Prince Maurice of Nassau, for an expedition against Peru; and this was closely followed by another against Brazil under the command of Jacob Willekens and Pieter Heyne. If the attack on Peru had been conducted with as much spirit and ability as were displayed in that against Brazil, the whole of South America would probably have been subjected to the dominion of Holland.

1623.

Fleet commanded by Jacob l'Heremite.

The expedition against Peru is the subject of the present chapter. The force destined for the purpose consisted of eleven sail of shipping, under the command of Admiral Jacob l'Heremite, an Officer who had served the Dutch East India Company many years with reputation. A mortal disease which disabled him from exercising command at the most critical time of the expedition, with his subsequent death, is the cause why this voyage has more generally been entitled the Voyage of the Nassau Fleet, than of Admiral Jacob l'Heremite; the appellation of Nassau Fleet being in compliment to Prince Maurice, who was a principal promoter of the design. The early histories of the voyage particularise the name and magnitude of each individual ship; but as their achievements bore no proportion to their force, it seems unreasonable to be so minute.*

* The history of this voyage was first published at Amsterdam, in 1626, by Hessel Gerritz, accompanied with charts and views, under the title of Journael van de Nassausche Vloot. In 1629, a translation of the Journael into the German language, with additional remarks, was published at Strasburg, under the title of Diurnal oder Tagregister der Nassawischen Flotta, i. e. Journal or Daily Register of the Nassau Fleet; by Adolf Decker, a native of Strasburg, who had served as Captain of Troops in the Nassau Fleet on board the ship Mauritius. In 1634, De Bry published a Latin translation of the voyage, in his Hist. Americanæ, Pars XIII. A French translation was published in the Recueil des Voyages de la Compagnie, vol. IX. In all matter of fact which immediately relates to the transactions of the voyage, the Journal has the appearance of being correct, and is closely followed in the present account. M. de Brosses; who has given from Decker's publication a summary of the Expedition, remarks, that it is the work of an intelligent man, who wrote better than mariners do in general, The Journal nevertheless is not to be esteemed a candid narrative; it throws a veil over the conduct of the expedition, attributing every miscarriage to accident or to some secondary cause.

[page] 3

CHAP. I. 1623.

The Admiral's ship, named the Amsterdam, was of 800 tons burthen (400 lasten), mounted 42 guns, and carried 237 men. The ship of the Vice-Admiral was of equal force, and some of the other ships were very little inferior. The number of cannon mounted on board the different ships was 294, and the whole number of persons in the fleet was 1637, of whom 600 were soldiers. Two persons, Johan Van Walbeck and Justus Von Vagelaar, were appointed Mathematicians to the fleet; and among the pilots was Valentin Jansz who had sailed to Strait le Maire, in the voyage of the Lisbon Caravelas in 1619.

April. Departure from Holland.

May.

April the 29th, 1623, the Nassau Fleet departed from Goree, under orders from the States General to sail into the South Sea by the strait which Le Maire and Schouten had discovered, that being esteemed a more certain passage than by the Strait of Magalhanes. A leak breaking out in one of the ships, obliged them to stop at the Isle of Wight, whence they sailed May the 8th. On May the 31st, near Cape St. Vincent, they fell in with a fleet of Barbary corsairs. On board these vessels, they found among the prisoners to the Moors, some Hollanders, whom the Dutch Admiral released from their captivity, and distributed in his own fleet.

June.

June the 4th, being near the coast of Africa, they met and captured four Spanish vessels from Pernambuca bound for Spain, laden with sugar. Two of the prizes, and a ship of the fleet which sailed so slow as to retard the rest, were dismissed for Holland. The other two prize vessels were furnished with crews, and made part of the fleet.

July. C. de Verde Islands.

July the 5th, the fleet anchored at St. Vincent, one of the Cape de Verde islands. At this, and at the neighbouring island of St. Antonio, good refreshment was obtained, except in that most necessary article, fresh water, which was scarce.

B 2

[page] 4

1623. July. Island St.Vincent.

The Island St. Vincent is rocky, dry, and for the most part barren; and was then uncultivated. Some wild figs grew in the middle of the island, and the Colocynthis Silvestris, a plant which is said to possess a strong purgative quality. The ground is exceedingly parched, except in the rainy season, which generally begins in August and ends in February, but is not always regular. The bay, however, is safe and commodious, the anchorage being on a bottom of clear sand, the depth 18 to 25 fathoms: turtle and fish also are here in abundance, and goats were caught on the island which were fat and well tasted. The watering place was at the SSW side of the Bay of St. Vincent, where was a small brook or spring which might have furnished sufficient for two or three ships, and not more; therefore pits were dug, but the water obtained from them was brackish, and was afterwards supposed to be the principal cause of a dysentery with which the crews of the ships were attacked.

Island St. Antonio.

The Island St. Antonio abounded in oranges and other fruits; which were procured for the fleet by traffick with the negro inhabitants, who were computed to be in number about 500. They shewed written certificates of their friendly dealings, given to them by the captains of Dutch ships which had stopped there at different times.

August. Sierra Leone.

From the Cape de Verde Islands, the fleet sailed to Sierra Leone, where they anchored on August the 11th. In this passage they had continual rain, which, joined to the badness of the water, made the ships crews sickly. The journal gives for the latitude of the road, 8° 2′ N. 'The mountain Sierra Leone is on the South side of a river which runs into the Atlantic; it is high, and covered with trees, and is easy to be known by those who come from the Northward, as no other part of the Continent in that route is so high.'

1623. August. Sierra Leone.

Before the Hollanders were admitted to have free communication with the shore, the Admiral was obliged to make

[page] 5

presents to the chief and to the chief's brother, which consisted of two bars of iron, two pieces of cloth, and some things of smaller value. Until this matter was settled, the natives, who are negroes, would not venture on board the fleet without hostages being delivered as sureties for their safe return to the shore.

Some seamen of the fleet who landed here, found and eat of a species of nuts which in appearance resembled the nutmeg, except that they were rather larger; but soon after their return to the ship, one of them died suddenly, and it was evident from an immediate change in his colour, which became violet, that he died of poison. By administering antidotes, the rest escaped.

In careening the ship Mauritius here, by neglecting to stop the lower skupper-holes, she nearly filled, and had 7 or 8 feet water in her hold before it was discovered.

The closeness of the air, and an immoderate use of limes which grow here in prodigious quantities, operated with the causes already mentioned, and increased the dysentery which prevailed amongst the crews, so that during their stay at Sierra Leone, they buried 42 men. The Admiral likewise was taken ill.

September.

October. Cape Lopez Gonsalvo.

September the 4th, they sailed from Sierra Leone, and stood for the Island St. Thomas, with the wind from the South; but the bad sailing of the ship Arend prevented their fetching St. Thomas; therefore they stood in again forth African coast; and on October the 1st, anchored near Cape Lopez Gonsalvo, with intention to water; but the water at that place was found so foul and brackish, that it was determined to sail for the Island Annobon,

Sand bank near Cape Lopez Gonsalvo.

1623. October.

Two ships of the fleet grounded on a sand bank, three quarters of a league WbS from Cape Lopez Gonsalvo. Close to the bank there was 25 fathoms depth. The ships were got off with little damage; but the Admiral, whose health at this time was nearly re-established, suffered so much from anxiety and

[page] 6

fatigue on the occasion, that he relapsed into illness, and from that time his health continually declined.

During the passage to Annobon, complaint was made against Mr. Jacob Begeer, principal Surgeon of the ship Mauritius, against whom it was alledged, that several of his patients, soon after taking the medicines administered by him, had died in a manner which gave cause to suspect there was something extraordinary in his practice. The Vice and Rear Admirals were jointly commissioned to enquire into the truth of this complaint, and October the 12th an examination took place. The Surgeon answered the accusations against him by protestations of innocence; but, says the journalist, ' as there were half proofs against him, torture was applied to make him confess his guilt; nevertheless he persisted in denial, telling the Commissioners they might do with him as they pleased.' This was regarded as insensibility, and created a new suspicion, that he had some protecting charm. On being searched, the skin and tongue of a serpent were found upon him; yet however convincing such a discovery might be to his Judges, ' they could not at the first examination prevail over his obstinacy,' and he was remanded into confinement. On the 16th, this miserable man was again ordered before the Commissioners for examination, when being let out of irons for that purpose, he found opportunity to elude his guard and to jump into the sea, with design to drown himself; but two of the ship's crew leaped after him, and kept him up till a boat went and took them all in. After much resolute denial, the prisoner's constancy was subdued, and he confessed, or was compelled to admit, that he had purposely caused seven men to die, because the care of them gave him too much trouble; also that he had endeavoured to enter into a compact with the Devil, whom for that purpose he had invoked; but notwithstanding his efforts, he had never been able to prevail on the Devil to make his personal appearance.

5

[page] 7

The prisoner, it is said, was suspected of other crimes, ' but as he was reduced to a weak state, his Judges contented themselves with this voluntary confession,' and pronounced sentence of death upon him; according to which, on the 18th, by order of the council, he was beheaded on board the Mauritius, the ship to which he had belonged.

1623. October.

Island St. Thomas.

23d.

The 20th, the fleet came in sight of the Island St. Thomas. On the 22d, the Vice-Admiral went with two boats to examine for anchorage at the small Island of Rolles which is near the SW point of St. Thomas, and to see if fruits or refreshments of any kind could be obtained there. On his return he reported the depth of water near Rolles to be from 7 fathoms to 4½ fathoms, the bottom rocky and the anchorage bad; and that from the lateness of the season, there were very few oranges at Rolles. Upon this representation, the Admiral determined for the Island Annobon, which they made on the 29th, bearing WbS 10 leagues distant; and the next day the fleet anchored in the road.

29th. Island Annobon.

1623. October.

Annobon was subject to the Portuguese, though few of that nation were on the Island. It abounded with fruits, and, notwithstanding what had been said of the lateness of the season, more especially with oranges of excellent taste. Here was a Portuguese Governor, with whom the Admiral came to an agreement, that if the Hollanders were not molested in taking fresh water and oranges, and the inhabitants were allowed freely to supply them in traffick with other refreshments, no hostility or injury should be committed. The number of the black inhabitants at Annobon was said to be 150 males, besides women and children. They were in extreme submission to the Portuguese, though not more than two or three of that nation were left to govern them. When it happened that any among the negroes were refractory, they were transported to the Island St. Thomas, which is distant about 40 leagues from Annobon. This was a punishment so much dreaded, that there was no

[page] 8

occasion to have recourse to any other. Oxen, goats, hogs, poultry, cocoa-nuts, oranges, tamarinds, bananas, sugar canes, and potatoes, were the supplies obtained by the fleet at Annobon. The oranges were so abundant, that in the different ships during their short stay, above 200,000 were taken of large size, full of juice, and of excellent flavour. The governor said many vessels had already in this same season, stopped and taken large supplies of fruits at Annobon. Cotton was collected on the Island, and in the mountains there were civet cats.

' The Island Annobon lies in latitude 1° 20′ S. It is 6 leagues in circuit, and is high land. The road in which the Dutch ships anchored is on the NE side of the Island, and the depth from 16 fathoms, to 7 fathoms very near to the shore and abreast the town or village; the bottom sand. The village had for its defence a stone wall; but when the inhabitants cannot hinder the descent of an enemy, they quit their houses and retire to the mountains. On the SE side of the Island is a good run of water, which descends from the mountains into a valley of orange and other fruit trees; but watering there would be difficult on account of the surf.' *

November.

November the 4th, the fleet sailed from Annobon. On the 11th, being advanced 90 leagues to the WSW, they had the South-east trade wind.

The 20th, three boys who were wrestling on the deck of the Admiral's ship, being close hugged together, by a sudden motion of the ship were all thrown overboard. One only of the three was saved.

The Admiral's instructions directed him not to touch on the coast of Brasil, or on any part of the American coast Northward of the Rio de la Plata. After passing the latitude of that river, the winds were constantly from the westward, and the fleet was not able to approach with in sight of the Continent.

* Journael Van de Nassausche Vloot, p. 31. Rec. des Voy. de la Comp. Vol. IX, p. 29 & seq.

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 9

January the 3d, the latitude was 42° 15′ S; and on the 4th, the variation was found 22 degrees NEasterly.

1624. January.

The 19th and 20th, the sea near them was in many parts discoloured with an infinite number of small red shrimps. The 26th, they were in latitude 51° 10′S. On the 28th, one of the prize barks with a crew of eighteen men, was separated from the fleet, and being unable to rejoin, she bent her course homewards.

February.

Tierra del Fuego.

In Strait le Maire.

February the 1st, the fleet made Cape de Peñas, which is on the Tierra del Fuego about midway between the Canal de San Sebastian and Cape St. Ines; and at 5 leagues distance from the land, had soundings at 25 fathoms depth. The next day they entered Strait le Maire. The Journalist says, 'on February the 2nd, we found we were before the entrance of Strait le Maire, which we should not have known or suspected if the pilot of the ship Eendracht, Valentin Jansz, who had been there in January 1619 with the Lisbon Caravelas, had not recognized the high mountains which are on the Western side. This entrance has nevertheless good marks, because the Eastern shore of the Strait, named Staten Land, is high, mountainous, and broken; whilst on the Western side are seen some round hills close to the sea side.'

On the foregoing extract it may be remarked that there could not be much difficulty or doubt in knowing Strait le Maire, when the land on each side was clearly seen, and a clear open horizon between. Where two or more Straits are in a neighbourhood, as among the Islands near the East end of Java, land-marks will serve to ascertain the particular Strait: but Strait le Maire has no other near it, and the separation of the two lands is a mark not liable to be mistaken for any thing else. It affords a curious specimen of the aptitude of writers of Voyages to imitate each other, that a similar observation respecting this same Strait, has been made more than once in the histories of later voyages.

1624. February.

The wind being variable, and the currents in the Strait rapid

VOL. III. C

[page] 10

and irregular, the ships were much dispersed. The Orangien, which was the Rear Admiral's ship, and another ship, anchored in a Bay of the Tierra del Fuego, near the Northern entrance of Strait le Maire. They trafficked with some natives there for seal-skins, and caught with hook and line a quantity of fish like whiting; also on the shore they found shell-fish. The Bay did not afford shelter for large ships against the East winds; and during other winds they were much incommoded with heavy squalls from the hills. Near the entrance of a small river there was good riding and shelter for small vessels, but not depth for ships. This Bay was named after the Rear Admiral, Verschoor Bay.

Verschoor Bay.

Valentin's Bay.

Another ship, the Griffon, anchored likewise on the Tierra del Fuego side, in a Bay farther to the South, 'which reckoning from the Northward, is between the second and third point on the Western side of the Strait.' This Bay was named Valentin's Bay. The Admiral intended to have gone in there with the other ships, but was prevented by signals made from a boat which had been sent in to sound, of the anchorage being unsafe. Some time afterwards, however, the Admiral was informed by the Captain of the Griffon, that the anchorage in Valentin's Bay was good, also that a fleet might ride there with safety; and that the signals to the contrary purport from the boat were made contrary to his opinion and advice.

Chart by Van Walbeck

Mistake concerning Valentin's Bay, in the later Charts.

1624. February.

The mathematician J. Van Walbeck, made a chart of Strait le Maire and of the SE part of the Tierra del Fuego, which is here copied from the Journael. It furnishes the most authentic geography we have of Nassau Bay, and of the land with in Cape Horne, and bears the marks of having been done with much care and examination. A copy of this Chart given in the Receuil des Voyages de la Compagnie, through the engraver's want of care, has occasioned the name Valentin's Bay to be misapplied to a Bay which is farther South, and not within the Strait le Maire: and so much easier it has been found to consult the

5

[page] 11

French translation than the original publication, that this mistake has been perpetuated to the charts of the present day. The Chart of the Southern parts of America in the 1st Vol. of this work, was like others, constructed without having seen the Amsterdam publication of the Voyage of the Nassau Fleet.

The Valentin's Bay of Jacob l'Heremite's voyage, is evidently the same which, in 1619, the Nodales named the Bay de Buen Suceso,* which name it properly retains. Verschoor Bay seems to be the Port Mauritius of the present charts.

2d.

14th.

Cape Horne.

On the evening of the 2d, all the ships, except the Griffon, had passed Strait le Maire, and were collected; but Westerly winds and a current setting Eastward, prevented their gaining ground. On the 14th, the compasses were observed to differ greatly from each other. The latitude that day noon was 56° 20′ S, and early in the afternoon Cape Horne was seen 7 leagues West from them.

15th.

On the 15th, 'in doubling Cape Horne, a great gulf was seen between that Cape and the next Cape to the West.' The Admiral would have entered it in hopes of finding anchorage, but was disappointed by the weather becoming foggy and the wind dying away.

16th.

17th.

1624. February. Nassau Bay, Tierra del Fuego.

The 16th, the latitude was 56° 10′ S, and Cape Horne bore from them East. This day they had sight of two Islands, ' not marked in any chart, which were estimated to be 14 or 15 leagues to the West of Cape Home.' A boat was put out with a grapnel, or small anchor, and line, to try if there was any current, and according to this experiment, in which there was no bottom within reach of the grapnel line, the stream appeared to be setting to the NW; nevertheless on the next day, the 17th, it appeared that during a fog the fleet had lost ground. The wind was from WNW, and the Admiral, being apprehensive of falling to leeward of Cape Horne, steered

* See Vol. II. p. 460.

c 2

[page] 12

for a great Bay, which was afterwards named the Bay of Nassau, and having run two leagues within it, the fleet anchored in a good clay bottom, with depth from 25 to 30 fathoms.

The passage from Holland to Cape Horne had occupied nine months; which is commented on in the Journal, and accounted for by the departure of the fleet being at so early a season, that it was thought necessary not to proceed expeditiously, lest the arrival off Cape Horne should happen during the Southern winter, a time unfavourable for navigating in a high Southern latitude. Their passage, however, though intended to be made leisurely, was retarded beyond the time proposed, in consequence of their keeping so close to the coast of Africa. The Caravelas, which left Lisbon September 27th (1618) and arrived off Cape Horne early in February, is cited in favour of a later outset. It has indeed of late been contended, that the passage round Cape Horne into the South Sea can be performed with greater case in winter than in summer; * and the facts and arguments advanced in support of this opinion, are such as may encourage single ships to prefer undertaking it in winter, or at least not to be deterred by consideration of seasons; but with a large fleet it would be a hazardous experiment.

18th.

Schapenham Bay.

The day after the fleet anchored, more convenient anchorage was found in a cove on the West side of Nassau Bay, where the ships would lie close to a fall of fresh water, and could supply themselves with wood and ballast. This anchorage was named Schapenham Bay; but though it offered many advantages, one was wanting to make it a good port for refreshment. No fish were found in Schapenham Bay, except shell-fish on the rocks.

1624. February. Nassau Bay, Tierra del Fuego: 23d.

Boats and parties of men were immediately employed on shore to fill fresh water. Some natives came to the watering-place, whose behaviour to the Hollanders appeared friendly. On the 22d, a tempest arose so sudden and violent, that the

* Voyage of Captain Colnet.

[page] 13

boats filling water were obliged to return to their ships, leaving part of the crews behind. On the 23d, the wind having abated, the boats were again sent to the shore, and the business of watering was resumed; but in the afternoon, a sudden renewal of the storm again forced the boats off, and nineteen men belonging to the ship Arend (Eagle) were left on shore, who, by most unaccountable negligence, were unfurnished with arms. The next day (the 24th), the weather having become moderate, the boats were again dispatched to the watering-place, when of the nineteen seamen left on shore only two were found alive. The natives, it seems, without other cause of quarrel than the Hollanders being unprovided with means of defence, had attacked them with clubs and slings, and killed all but two, who had the good fortune to conceal themselves. Five of the bodies were found cut into quarters, and mangled in a strange manner. After this event, a guard of soldiers were constantly sent with every boat; but not a single native was afterwards seen.

24th.

Examination of the coast by the Vice-Admiral.

1624. February. Nassau Bay, Tierra del Fuego.

Schapenham, the Vice-Admiral, had been sent in a yacht named the Windhond (Greyhound), to examine the coast round Nassau Bay. On the 25th he returned, and the report he made to the Admiral was to the following effect: He first went to a part of the coast whence smoke had been seen to rise, which is marked on the chart under the name of Windhond's Bay. He anchored there for the night, and in the morning landed at some huts, where he found inhabitants with whom he spoke. In going to the East, he crossed a large canal, and found himself to the Eastward of Cape Horne. He went still farther, and anchored behind a cape within an island, which he named Terhalten, after one of the officers of the troops. The wind coming from the Eastward, he returned to the fleet. He reported likewise, 'that the Tierra del Fuego is divided into many islands; and that to pass into the South Sea, it was not necessary to double Cape Horne; for that Nassau Bay

[page] 14

' might be entered from the East, leaving the cape to the South. That on every side he saw openings, bays, and gulfs, many of which went into the land as far as the view extended, whence it is to be presumed that there are passages from the great Bay, or rather the Gulf of Nassau, through which vessels might sail into the Strait of Magalhanes.'

The greater part of the Tierra del Fuego seen by the Nassau Fleet, is mountainous land, but with many fine vallies, and meadows watered with rivers. Between the islands are many good harbours, where large fleets might lie sheltered. The mountains were covered with trees, which had all a leaning towards the East, occasioned by the prevalence of strong Westerly winds. In all this part of the Tierra del Fuego there is wood, though the soil is no where more than two or three feet in depth; and on the shore are plenty of small stones for ballast.

Inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego.

1624. February. Nassau Bay, Tierra del Fuego.

The Westerly winds here are extremely impetuous, and get up very suddenly; on which account the Journalist advises navigators bound round Cape Horne, unless they have occasion to put into port, to keep a good distance to the South of the Cape. The Journalist affirms that the inhabitants of this land were as white as the people of Europe, which was discovered only by seeing a young infant; for in others, the natural colour of the skin was no where visible. It is a general practice among the natives to rub the body over with red ochre, or to paint themselves with different colours, and in fanciful manners. Some had the face and limbs painted red, and the body white; some were entirely red on one side, and entirely white on the other. They were a well-proportioned people, in stature differing little from Europeans; they had long thick black hair, and teeth 'as sharp as the blade of a knife.' The men were entirely without clothing, and the women had nothing more than a small piece of skin about the waist, and necklaces made of shells. The women were painted like the men. Their huts or

[page] 15

houses were built with trees, in form circular at the bottom, and terminating nearly in a point at the top, where there was a small opening for the smoke to escape. The floor was two or three feet deeper than the ground without, and the sides were covered with earth. The furniture they possessed consisted of fishing-tackle, and their arms. They had lines, hooks, and harpoons, neatly made. Their arms were bows and arrows, lances headed with bone, clubs, slings, and they had also knives made of stones, very sharp.

The natives were never abroad without their arms, the reason of which, from what could be comprehended of their meaning, was supposed to be, because they were constantly at war; the people of the Western side of Nassau Bay with the Eastern people. The natives seen at Schapenham Bay, and at Windhond Bay, were almost all painted red; whilst the inhabitants to the East of the place marked Goe Ree in the chart, and near Terhalten Island, were painted black.

They had boats or canoes made of the bark of large trees, dexterously curved, so as to give them a shape like the Venetian gondolas. They were strengthened at the bottom, both length-ways and across, with timbers, and these again were covered with bark; by which means the bottom was kept dry and free from water. These canoes were of different sizes, from ten to sixteen feet in length, and about two feet in width.

Of the manners and dispositions of the natives, the Journalist remarks, ' they more resemble beasts than men; for besides that they tear men to pieces, and devour the flesh raw and bloody, there was not perceived among them the smallest indication of a religion or government. On the contrary, they live together like beasts.'

1624. February.Nassau Bay, Tierra del Fuego.

There are several particulars in the foregoing description, which give to the people found in Nassau Bay more the appearance of being settled inhabitants, than any of the people met

[page] 16

with on the Tierra del Fuego by other voyagers. The construction of their houses was in a manner adapted for constant residence; and from their being so well provided with boats, one of two things is to be inferred; either that the Southern part of the Tierra del Fuego was their constant home, or that some inlet or inlets within Nassau Bay afforded them easy communication with the Strait of Magalhanes.

In justice to this voyage it may be acknowledged, that it has communicated more information concerning the Tierra del Fuego than any other since the first discovery. Having noticed a mistake in the French copy of Van Walbeck's chart of the Tierra del Fuego, it is right to defend his chart from misrepresentation in another instance. Decker, or his editor, in the copy given to the German translation, has taken licence to draw a continuation of coast South-westward from Nassau Bay beyond what is laid down in Van Walbeck's chart, as published in the Amsterdam edition of 1626, making thereby the Tierra del Fuego to extend in latitude half a degree farther South than Cape Horne.

The evening of the 25th, it blew a violent storm, in which a boat belonging to the Rear-Admiral's ship was overset, and eight of the crew were drowned.

Departure from Nassau Bay.

The 27th, the fleet sailed from Nassau Bay, going out by the Western passage, the same by which they had entered. As they left the Bay, the wind died away, and a swell of the sea setting from the Westward, carried the ships very near the South-eastern shore of the passage. There was no bottom for anchorage, and they were in apprehension of being driven on the rocks; when the breeze sprung up again in time to carry them clear.

March.

In case of separation, the Island Juan Fernandez was appointed the place of rendezvous.

6th.

1624. March.

For some time after leaving Nassau Bay they had Westerly winds, chiefly from the NW quarter. March the 6th, the Admiral assembled the Council to advise on the most proper

[page] 17

measures to pursue if the wind should continue from the West-ward. The determination of the Council was to persevere two months longer in the endeavour to get into the South Sea; and the Island Juan Fernandez, which was the place prescribed by the States General for meeting in case of separation, was continued the rendezvous.

8th.

20th.

28th.

On the 8th, they were as far South as latitude 61°. The 18th, 19th, and 20th, they were favoured with a fresh wind from the SSE, and afterwards with variable winds, and the air mild. In the course of the month, three ships, the Orangien, the Mauritius, and the David, were separated from the fleet. On the 28th, the Admiral, with the remaining ships, had sight of the coast of Chili, in latitude 42° 10′ S, and in the evening, they were within a league of the land. The coast was elevated, and within were seen mountains of moderate height. It is said, not in the original publication of the Journal, but in a subsequent edition, that 'the Admiral, Jacob l'Heremite, who was then ill in bed, being informed how near they were to the coast of Chili, and to the port in the Island Chiloe, where Suarte Theunis, in the year 1603, had been received by the inhabitants with great affection, he, the Admiral, was of opinion the Chilese would also be willing to join with him against the Spaniards, and he wished his orders had permitted him to go direct to Chili. But he was precisely told by his instructions, that his fleet was destined to undertake the conquest of Peru.'

1624. April. Juan Fernandez. 6th.

The person here called Suarte Theunis is the Anthoine le Noir spoken of in Spilbergen's Voyage*. He is also mentioned in a Description of Peru and Chili which is annexed to the later editions of the Journal of this Voyage, wherein it is said ' Chilue [Chiloe ] is also in the hands of the Spaniards, but the force they have there is so inconsiderable, that a Dutch

* Suarte Theunis, i. e. Swarthy Tony; i. e. Anthoine le Noir, or Black Anthony. See Vol. II. p. 345.

Vol. III. D

[page] 18

Captain named Ant. Suarte formerly made himself master of it with 30 men.'

April the 4th, the Admiral and the ships in his company, arrived at the Island Juan Fernandez.

On the 6th, the ship Griffon, which had been separated from the fleet in Strait le Maire, rejoined the Admiral, as also in a few days after, did the other ships which had lost company. The Orangien had twice made the American coast; the first time in latitude. 50° S, afterwards in 41° S.

At Juan Fernandez the fleet rode in a Bay at the NE part of the island. 'The anchorage was on a steep bank, part rock, ' part sand; and the depth so great that to get ground at 30 or 34 fathoms, it was necessary to come within half musket shot of the shore; but before approaching so near, the ships were incommoded with obliged winds and calms, in such manner, that some were obliged to anchor at first in 80 and in 90 fathoms, and thence to warp into so fathoms, which is the proper anchorage.' At the time l'Heremite's fleet was at Juan Fernandez, the winds were as favourable for entering the Bay from the Northward as from the South.

1624. April. Juan Fernandez.

The vallies on the NE side of Juan Fernandez were covered with herbage, and the fresh water was excellent. In the Bay were good fish of different kinds, and in such abundance, that scarcely was the hook half a foot deep in the water before the fish would fight for the bait. Thousands of sea lions and seals lay in the daytime on the shore to enjoy basking in the sun. The seamen killed great numbers of them, some to eat, and some by way of diversion, which was attended with a merited inconvenience, for in a short time those which were left on the shore became putrid, and infected the air to such a degree, that the people of the ships scarcely dared venture to land. The flesh of the sea lion when cooked, was compared to meat twice roasted. Some of the men thought that when the fat was

[page] 19

cut off, it was not inferior to mutton; others would not eat it. There were goats on the Island, but difficult to approach, and thought not to be so well tasted as those of the Island St. Vincent. Among the trees were some like the elm, very good for making sheaves to blocks; there were other trees fit for carpenter's work; but none were seen tall enough for a ship's topmast. Sandal wood was growing in great quantity, of an inferior quality to the sandal wood of Timor, and near the Bay were some wild quince trees.

It is stated in the Journal, that three soldiers and three gunners of the Vice-Admiral's ship remained on the Island by their own will, refusing to serve longer in the fleet. This is mentioned as if it was an open defection, and seems to imply what is scarcely credible, that the state of discipline, and the nature of seamens engagements, were such as to entitle them to an option of quitting their ship during the performance of a voyage.

The 18th, the fleet left Juan Fernandez, steering North-eastward for the coast of Peru. Wind from the South. The variation of the needle observed in this run to the Continent was from l° ½ to 2° NEasterly.

May. Coast of PERU.

1624. May. Coast of Peru.

May the 3d, in latitude l6° 20′ S, they had sight of the coast of Peru; and on the 8th, were yearly abreast of Callao, at which time they took a small bark with a crew of eleven men, four of whom were Spaniards, the rest Indians and Negroes. From these people the Admiral received the unwelcome intelligence, that on the preceding Friday, the 3d instant, the Treasure Fleet, consisting of five ships richly laden, had sailed from the road of Callao for Panama. The Spanish Admiral in a ship of 800 tons burthen, mounting 40 guns, did not sail with the Treasure Fleet, but with two smaller ships of war, was still in Callao Road, where also a number of merchant vessels were lying. It was likewise learnt that the military force of the Spaniards at Callao was not more than 300 soldiers, for that

D 2

[page] 20

two companies of their best troops had been sent with the treasure; and the Indian prisoners assured the Hollanders, that both the native Indians and the Negroes would declare in their favour as soon as they should become masters of any place that could afford them protection.

Upon this intelligence a Council was assembled to deliberate whether to pursue the galleons bound to Panama, or immediately to land and attack Callao. The latter was resolved upon. Jacob l'Heremite was by this time too ill to command or to give directions, and had resigned the chief management to the Vice-Admiral, Gheen Huygen Schapenham.

Callao. 9th.

10th.

A descent on Callao, being determined on, and the ships having arrived close to the road, during the night of the 9th, troops were disposed in the boats, and with the Vice-Admiral at their head, they departed for the shore. The place proposed for the landing was in the inner part of the Bay of Callao, between the town and the river marked in the chart with the name de Lima, which was the part most protected from the Southerly winds; but on drawing near the shore, the surf was thought too high for landing whilst it was dark, as there would be danger of the arms and ammunition getting wet; they therefore waited till it was day-light, when the Spaniards appeared drawn up on the shore ready to oppose them. After some discharges of musquetry, without any attempt being made to land, Schapenham returned with his troops to the ships, which by this time had anchored in the road.

During the night of the 10th, the Vice-Admiral ordered a yacht of the fleet to be warped near to the shore; that under protection of her cannon, a landing might be attempted. But this was not done without being perceived by the Spaniards, who brought cannon against the yacht, and obliged her to retreat.

12th.

1624. May. Callao Bay

Schapenham gave the Spaniards no disturbance during the two next days; but on the night of the 12th, an attack was

[page] 21

made on the merchant vessels, which were about fifty in number, and drawn close to the shore under the protection of batteries. The boats of the fleet were sent to destroy them, orders being given to set fire to every vessel as soon as boarded, and to proceed to the next. In pursuance of these directions, between 30 and 40 vessels were set in flames, and some Spaniards made prisoners, which was effected with the loss of seven Hollanders killed, twice that number wounded, and one taken prisoner by the Spaniards.

The Journalist admits some want of foresight in this enterprize. He says, ' If we had gone provided with hatchets to cut the cables, instead of setting fire to the vessels, the wind which blew from the shore would have made us masters of them all, and the business would have been done in less time, and with less loss of men.' Instead of benefiting by so obvious a plan, not one prize was made; and after the boats retreated, the Spaniards extinguished the fire in many of the vessels. Nine of those which remained in flames, as the cables burnt, drifted off from the shore towards the fleet, approaching like so many fireships; so that to avoid them, the Hollanders were necessitated to take up their anchors and shift their stations.

1624. May. Callao.

In a Spanish account of the proceedings of the Dutch fleet against Peru, written at the time, it is related that ' when the Spanish ships were burning in the port of Callao, there were great moanings and lamentations at Lima, a rumour being spread that the enemies were marching directly towards the city; and these lamentations did not cease till they learned the truth of the matter.'* The same narrative says, that a Spanish pilot belonging to the bark which the Hollanders captured before they entered the Port of Callao, prevented their pursuing the Silver Fleet by telling them, that it had been gone

* A True Relation of the successe of the Fleet under Jaques l'Heremite towards the Coast of Peru. Translated out of the Spanish. London 1625.

[page] 22

eight days from Callao, and that only a small part of the treasure had been shipped in that fleet; also that two millions of piastres were still in Callao Road, on board a ship that was to follow the fleet. This latter freighted ship is usually called the Recargo. Another circumstance related in the Spanish account is, that a Dutch gunner who was made prisoner by the Spaniards on the night the ships were burnt in Callao Road, being questioned concerning the Commanders of the fleet, said, that the Admiral, Jacob l'Heremite, was a man of much experience, but was not expected to live, his legs being greatly swoln; and that the Vice-Admiral was a haughty young man, and very cruel.

13th.

1624. May. Callao.

It clearly appears from the Dutch Journal, that the Hollanders were not deceived or misled by false intelligence, and so prevented from pursuing the Treasure Fleet. In other particulars, the Spanish account most probably is correct. The failure of the Hollanders in their first attempt to effect a landing at Callao, and the tameness with which it was attempted, relieved the people of Lima from their alarm and apprehensions, whilst it sunk the hopes of the Dutch Commanders. The subsequent inactivity of Schapenham and his Council, gave them an interest in crediting, and in obtaining credit for, the most exaggerated statements of the strength of the Spaniards, as the only apologies to be found for their conduct. The Journal says, it was now understood from the most circumstantial accounts given by the prisoners of every description, that the Spaniards were every where strong; that in Potosi alone were above 20,000 Spaniards, besides Indians and Negroes, all well furnished with arms; that the towns along the coast were well provided with means of defence; that the Viceroy had secured the fidelity of the Indians and Negroes; in short, that there existed not the smallest chance of executing the grand plan of invasion. Accordingly, on the 13th, being the day next after the conflagration of the merchant vessels, and only the fourth of their being at Callao, it was determined

5

[page] 23

in council, that the enterprize against Peru had failed. The plan of a serious invasion was now wholly abandoned, and in its place was substituted one merely depredatory. The fleet was parcelled out into detachments, to scour the coast and to plunder the settlements both Northward and Southward of Lima. Possession was taken of the small Island abreast the road of Callao, named in the Journal Isle de Lima, * and the frames of small vessels which had been brought in separate pieces from Europe, were got on shore to be set up.

The 14th, four ships were sent to the Southward under the command of Captain Cornelys Jacobsz, to attack the towns of Nasca and Pisco. In the night of the 21st, two Greeks belonging to the Vice-Admiral's ship, stole off with a small boat, and deserted to the enemy. The 22d, prize was made of a vessel from Guayaquil laden with wood, with a crew of 30 men, Spaniards and Negroes. On the information of these prisoners, the Rear-Admiral, Verschoor, was dispatched with two ships to make an attack on Guayaquil.

14th.

23d.

All this time, the Recargo galleon lay moored close to the town of Callao, whether freighted or not the Hollanders had not ascertained, for she remained unattempted till the 27th, when the Vice-Admiral sent against her two prize vessels fitted as fireships; but on their arriving within musket shot, it was discovered that the galleon was protected from their nearer approach by a bank too shoal for them to pass.

June. Death of Jacob l'Heremite.

1624. June. Callao. 6th.

June the 2d, the Admiral, Jacob l'Heremite died. His anxiety for the welfare of the fleet trusted to his command hastened his dissolution; and it is due to his memory to remark that no blame attaches to him for the miscarriages of the expedition. On the 4th, he was buried on shore in the Island de Lima. The command of the fleet devolved as a matter of course on the Vice-Admiral, Schapenham; but the flag of the late

* In the present Charts, I. de San Lorenz.

[page] 24

Admiral was kept flying, that his death might not become a subject of rejoicing, or of exultation, to the Spaniards.

On the 6th, another attempt with fireships was made on the Recargo, which was attended with no better success than the former. The 8th, a slight shock of an earthquake was felt on the Isle de Lima.

Whilst detachments from the fleet were employed in expeditions along the coast, Schapenham himself remained stationary at Callao, and during this blockade a few small coasting vessels were taken. Some of the Spanish prisoners solicited and obtained leave of Schapenham to write to the Viceroy, to request that he would enter into treaty for their ransom. On the 13th, a boat with a flag of truce was sent ashore with the letter of the prisoners to the Viceroy, and it being first delivered to the Spanish General, he returned for answer, that the Viceroy had nothing but powder and ball at the service of the Hollanders; that he would not treat with them for the liberation of prisoners; and that if any Hollander again presumed to land at Callao, though with a flag of truce, he should be hanged with the flag about his neck.

13th.

This indiscreet answer proved fatal to the prisoners. Upon receiving it, Schapenham and his Council determined on their death, and on the morning of the 15th, twenty-one Spaniards were hung at the fore-yard of the ship Amsterdam, in which the late Admiral's flag was kept flying. Three aged Spaniards were spared, and put into a small boat, charged with a reproachful message to the Viceroy, which concluded with a declaration, that the Hollanders had no desire to give or take quarter with the Spaniards.

15th.

1624. June. Callao.

The reasons offered in the Journal in justification of this sanguinary execution are, ' that the Hollanders had not provisions to spare, water especially; and could not afford to subsist people from whom they could expect no service, profit, or

[page] 25

ransom; that to have released them gratuitously would have been contrary to all maxims of prudence and might have been productive of many evils; moreover, it would have given the Spaniards occasion to laugh at them; that it was necessary at all events to get rid of their prisoners, and no other certain and ready way offered than to take their lives.'

In the evening of the 15th, the four ships which had been detached Southward under Cornelys Jacobsz, anchored in Callao Road. Captain Jacobsz had landed with a party of men near Pisco, and had marched within musket shot of the town; but finding the fortifications in good condition and well defended, he held council with his officers, and it was concluded to retreat and to re-imbark. In this affair, the Dutch suffered considerably, having five men killed outright, and sixteen wounded; and what was much more discouraging and of worse consequence, thirteen of their men deserted to the Spaniards.

On the 25th, a gunner of the fleet was hanged for attempting to desert.

25th.

State of Chili.

1624. June. Callao.

Schapenham was ashamed of the insignificant part he was acting with his large force, and at the same time seems to have been perfectly at a loss what to undertake. To avoid the appearance of having no plan, perhaps also with some faint meaning, he professed a design to return Southward with his whole fleet to Chili, to join the native Chilese against the Spaniards. The plan is as gravely discussed in the Journal as if its execution had been fully determined. Some of the arguments give information concerning Chili, and are therefore worth inserting. ' The Commander in Chief was well informed of the state of Chili from a native of the country, as well as from the report of many prisoners. The Chilese had been many years in arms against the Spaniards. Baldivia which they had taken in 1599 was still in their possession; and at the close of the year 1623, a troop of 50 Spaniards had been surrounded by

VOL. III. E

[page] 26

them and cut to pieces. In the present year 1624, the necessities of the Spanish troops in Chili were so great as to occasion a mutiny of the men against their officers. The Spanish infantry by their muskets have advantage over the Chilese infantry; but the Chilese are excellent horsemen, and their cavalry is much superior to the Spanish, and so numerous that they often collect in bodies of three or four thousand men. The military employed by the Spaniards in Chili are mostly composed of malefactors taken from the prisons. The reason why the Spaniards do not abandon Chili is, the apprehension they entertain that the Chilese would not long remain contented with their own country, but would penetrate into Peru; and besides, the Indians of the South are wanted to work in the mines of Potosi, those inhabiting to the North of Potosi not being able to stand the labour, and quickly dying of fatigue.'

To make preparation, or at least the show of preparation, for the invasion of Chili, forges and artificers were landed on the Isle de Lima, and set to work to fitting gun carriages and making; other furniture necessary for such an enterprise.

Isle de Lima, or de San Lorenzo.

1624. July. Callao.

In the mean time, the want of fresh provisions and of a supply of fresh water, occasioned the seurvy and other diseases to break out among the ships crews; evils to which the Commander in Chief patiently chose they should be submitted, rather than he would hazard a descent on the main land. Pits had been dug in the Isle de Lima, to try for fresh water, but the ground was stony and they were not able to penetrate sufficiently deep. In this distress however, relief came to them unexpectedly. One of the scorbutic patients, a native of Switzerland, in rambling over the Island, was induced by curiosity or the hope of making some discovery, to ascend to the top of the highest hill, the appearance of which at a distance was naked, and gave no expectation of verdure or vegetation. He there found ' certain herbs with which he was acquainted,' by eating of which he received much

[page] 27

benefit, and the place supplied them in such abundance as to serve the whole fleet. Being eaten in soups and sallads, they proved so refreshing and salutary, that in a short time all the scorbutic patients recovered their health.

In the Western part of the Island de Lima were many burying places of the native Peruvians, which appeared to be very ancient.

During the whole month of July, Schapenham remained as quietly in Callao Bay as he had throughout the month preceding, employed always in making preparation for the proposed Chili expedition. On the 18th, two Spaniards who had killed a Spanish officer in a quarrel, to escape from justice, deserted to the Holland Fleet. One of them was a soldier, the other the principal comedian of the theatre at Lima.

August.

August the 5th, Schapenham was formally installed in his office of Admiral and Commander in Chief; the companies of the nearest ships being ordered in rotation on board his ship, the Delft, to take the oath of fidelity; after which, the Admiral himself went on board the more distant ships, to whose crews the same oath was administered.

Guayaquil taken and burnt.

In the afternoon of the 5th, the two ships which had been sent to the Northward under J. Wilhelm Verschoor, (now become Vice-Admiral) returned to Callao Road. Verschoor had attacked and taken the city of Guayaquil, but with the loss of 35 men who were killed in the landing. Captain Engelbert Schutz, who commanded the Dutch troops, signalized himself much on this occasion. Verschoor had not a force sufficient to enable him to garrison Guayaquil, he therefore set fire to the town, destroyed a large quantity of merchandise, and a galeon with other shipping, and brought with him one prize. About 100 Spaniards were killed in defence of the place, and 17 were taken prisoners, who were afterwards thrown into the sea near the Island Puna, it being laid to their charge that they had endeavoured to act treacherously to the Hollanders.

E 2

[page] 28

1624. August. Callao.

Verschoor in his return from Guayaquil to Callao, had sailed close on a wind across the SE trade till he was 350 Dutch miles (15 to a degree) from the Continent, and in 25⅓ ° S latitude. On standing back to the land, he designed to have visited Arica, but could not fetch farther South on the coast than in 13° S latitude.

13th. 14th.

Island los Pescadores.

Bay, and Watering place.

The 13th, the tents, artificers, their work and effects, were taken off from the Isle de Lima; and on the 14th, Admiral Schapenham, with his whole fleet, sailed from the Port of Callao to a bay 4 Dutch miles distant to the Northward, where he was informed fresh water could be obtained. This bay in the Spanish Atlas is named Porto del Ancon; the Dutch Fleet in sailing to it passed between two of the small islands called los Pescadores, ' having a small rock on their larboard (left) hand; and afterwards hauling close upon a wind to the Eastward, they ran in for the bay, where they anchored.'

It was late in the day when the fleet arrived. Schapenham with unaccustomed celerity, landed the same evening with five companies of soldiers and a large party of seamen. Agreeable to the information he had received, he caused wells to be dug at a place near the sea shore. Good fresh water being found there, the guard was strengthened, works were thrown up during the night, and ten small and six large cannon were landed for protection to the watering parties.

16th.

The wells did not supply water so fast as was desired for so large a fleet, and some eminences not very distant were thought to overlook the intrenchments. The Admiral was apprehensive that the Spaniards would soon be there with artillery, therefore the watering was continued no longer than till the morning of the 16th, when every thing was re-imbarked, and the Hollanders returned to their ships.

Here at length was found a landing clear of difficulty, within twenty geographical miles of the city of Lima: the force of the Hollanders was unbroken by separation, not materially dimi-

5

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 29

nished by sickness or accident, and was in all respects in a better condition than after a passage from their own country could possibly have been calculated upon by those who projected with it the conquest of Peru; but it was now admitted as undoubted fact, that the Spaniards were in too great force to be attacked, and that auxiliary aid was not to be expected from the natives; and Schapenham, with an incomplete supply of water, snatched by stealth and with trepidation, hastened to quit the land for fear of being attacked by those whom he had been sent to subdue. The proposed expedition to Chili came to nothing; but as no circumstance had occurred to excuse the not undertaking it after so much preparation, for the present it was only said to be deferred. Something however it was necessary to do, and as Guayaquil had been proved vulnerable, Schapenham formed the strange resolution to attack it again. With this view he sailed Northward with his fleet, which now, with the prize vessels that were kept and manned, amounted to 14 sail.

25th. Puna.

Guayaquil a second time attacked.

On the 25th, the fleet came to anchor near the Island Puna. Some of the ships were laid aground here to be cleaned; and in the mean time a detachment was sent against Guayaquil, double the force of that which had so recently mastered it: but the genius and fortune of Schapenham denied him under any circumstances to appear a conqueror. This second attack miscarried through the total neglect of discipline in the Dutch troops, who made a disgraceful retreat from the town, with the loss of 28 men.

September.

After many deliberations, on the 9th of September, it was resolved in council, that ' although there was great prospect of succeeding if they went to Chili, they would first go to Acapulco, in obedience to their instructions, there to cruise for the Manila galeons; and afterwards, according to the state of the fleet, they would determine whether or not to go to Chili.'

[page] 30

1624. September.

Before sailing, the town of Puna was burnt, and the church pulled down by the Hollanders. Eight soldiers of the company of Captain Schutz deserted here to the Spaniards. Four of them were Englishmen, and four French. The Journal says, 'To this time they had served well; but the bad success of the second attack on Guayaquil gave them disgust, and made them imagine that every thing would go ill with the expedition.' The many manifest proofs of incapacity and want of enterprize in the Commander in Chief, took from the men all confidence and expectation of success. Desertions naturally followed.

12th.

On the 12th, the fleet sailed from Puna, steering for the Galapagos Islands, where it was intended to stop: but in this they were disappointed by the wind being fixed in the SW quarter, with which they were so unlucky as only to fetch in sight of the Northern Isles, and the breeze was too light to enable them to get to windward: therefore they bore away for New Spain.

October. 20th. 28th.

On the Coast of New Spain.

October the 20th, they arrived in sight of the coast, and on the 28th, anchored before the harbour of Acapulco. At this time, the sea breezes set in about noon, and continued till midnight; after which, till noon again the winds were variable, and frequently accompanied with lightning and rain.

1624. Coast of New Spain.

A petty artifice was practised here by Admiral Schapenham, who tried to get some Spaniard of consequence in his power, with a view to obtain intelligence concerning the Manila ships. He sent a message to the Governor of Acapulco, importing that he had brought many prisoners from the coast of Peru, among whom were officers of rank and persons of consequence: that he was now about to quit the American coast to sail to the East Indies, and would be willing to accept of provisions for their ransom. He proposed to the Governor, as the most convenient method of settling the terms, that hostages should be mutually given. To this proposal the Governor sent answer,

[page] 31

that he would not exchange hostages; but that if the Admiral would release the prisoners for money, he would treat with him. Here the negociation ceased.

A division of the fleet under Vice-Admiral Verschoor, were ordered 20 leagues Westward of Acapulco, where they anchored near the coast. The Admiral with the rest lay at anchor spread along the coast near the Port of Acapulco. In these stations they remained great part of November, looking out for the arrival of galeons from Manila.

November.

The fleet was but indifferently stocked with fresh water. Port del Marques, an unfortified harbour in which was fresh water, lay close at hand, and it would have been easy for Schapenham to have landed a greater force than it is at all probable the Spaniards in that part of the world could have matched: yet, so extreme was his caution, that he would not venture to water his fleet, though on the point of quitting the American coast to sail across the Pacific Occan, Boats however went from two of the ships to Port del Marques, and two following days they returned laden with fresh water: but in a subsequent attempt, they were not so fortunate, the Spaniards having prepared an ambuscade, by which four of the Hollanders were killed, and the rest obliged to reimbark and retreat from the shore as speedily as they could. In the haste made, one man was left behind on the beach; but his Captain, Cornelys de Witte, who had gone himself on this service, returned to the shore in the face of the enemy, and took him into his boat, ' an act of generosity,' as is justly observed by the French translator, worth a wound which he received in his side, and of which he was afterwards cured.*

* A circumstance very strikingly similar to the one above related, occurred at the death of Captain Cook. Four of the Marines of the party on shore with him were killed; and in the hasty retreat made, after the boats had put off, one man still remaind on the shore, who could not swim. His Officer, Lieutenant(now Colonel) Molesworth Phillips of the Marines, though himself wounded at the time, seeing his situation, jumped out of the boat and swam back to the shore, and brought him off safe. The remark so well made by the French translator on the act and wound of Captain de Witte, is equally applicable to this incident.

[page] 32

1624. November. Coast of New Spain.