[frontispiece]

[page i]

NARRATIVE OF VOYAGES

TO EXPLORE THE SHORES OF

AFRICA, ARABIA,

AND

MADAGASCAR;

PERFORMED IN H. M. SHIPS LEVEN AND BARRACOUTA,

UNDER THE DIRECTION OF

CAPTAIN W. F. W. OWEN, R. N.

BY COMMAND OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF THE ADMIRALTY.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to his Majesty.

1833.

[page ii]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Dorset Street, Fleet Street.

[page iii]

ADVERTISEMENT.

IN presenting these Volumes to the world, it may be necessary to make a few observations upon the delay that has attended their publication.

It was the intention of Captain Owen to have arranged his manuscripts for the press shortly after his return from the long and adventurous Voyage which they relate; but he was almost immediately appointed to his Majesty's ship Eden, with orders to take out and establish the settlement of Fernando Po. The active preparations for this expedition prevented him from fulfilling his intentions at that period.

In 1831 he again returned to his native shores; but instead of enjoying that calm leisure which

[page] iv

his arduous services both called for and deserved, his whole time has since been occupied in settling Colonial accounts, and other public matters.

At this period, the Editor was informed that it was still the wish of Captain Owen to prepare his narrative for publication, though he had not sufficient time to devote to that purpose. Under these circumstances, the Journals of Captain Owen and of the officers engaged under him in the expedition, were entrusted to the Editor, and they are now presented to the world in the full conviction that their varied and interesting details will afford both entertainment and information.

HEATON BOWSTEAD ROBINSON.

Montpelier Place, Twickenham, June 1833.

[page v]

INTRODUCTION.

THE intention and extent of this expedition will in some measure be shown by the annexed instructions from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty; in addition to which, Captain Owen had a further power to increase the limits of the survey, if required, by any local information. These instructions, as stating the deficiencies in our hydrographical knowledge of the African shores, were sufficient in themselves to point out the course to be pursued by Captain Owen; and had it been left to his own discretion, he might have obtained the required information without the dreadful sacrifices, which it is the duty of these pages to record; for in a climate subject to such varied and deadly changes, a discretionary power was certainly advisable, in order, by a judicious arrangement and attention to the seasons, to avoid as much as possible its fatal effects upon Europeans. It will be observed that this power was not given to Captain Owen, and in the course of the work it will be seen how melancholy were the consequences.

[page] vi

No. 1.

By the Commissioners for executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, &c.

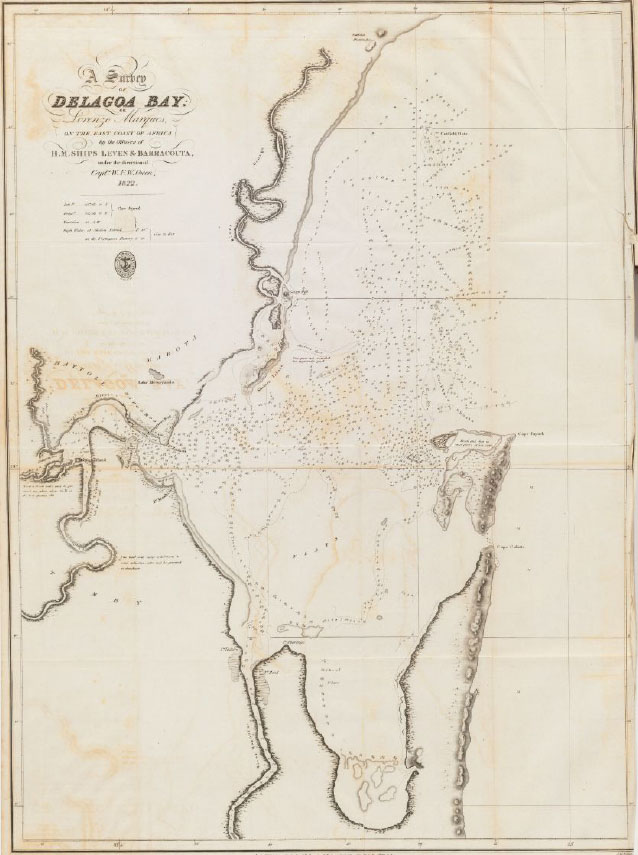

YOU are hereby required and directed to put to sea with his Majesty's ship Leven and Barracouta sloop under your orders, as soon as they shall be in every respect ready, and to proceed with all convenient expedition to the Cape of Good Hope, where you are to communicate with the Astronomer, and regulate your chronometers at the observatory established there, and to receive on board water and such refreshments as you may stand in need of. You are then to proceed to the eastward, and commence your survey either at the mouth of the Keiskamma, the present boundary of the colony of the Cape of Good Hope, and continue it as far as Delagoa Bay, or to commence at this bay and continue it southwesterly to the Keiskamma, according to the season of the year when you shall arrive off that coast, and as the north-west or north-east wind shall be found to prevail. In the latter case it may be advisable to commence with the bay itself, and to make a complete and accurate survey thereof with the two rivers, as far as may be safe and practicable, which are described as falling into it, collecting information of the numbers and character of the natives, their occupations, modes of subsistence, &c. the nature of the soil, and also

[page] vii

of the productions of the surrounding country. By the time that these operations are concluded, the north-westerly winds will have set in, when the interjacent coast between the bay and the Keiskamma may with more safety and convenience be approached. You will ascertain whether any and what bays, harbours, and inlets, may exist on that coast, examining the entrances into all the rivers that may occur, whether they are navigable, and by what description of vessels, and to what extent.

When this part of the coast has been completed, together with Delagoa Bay, which it is to be understood are the first in order to be surveyed, it will probably be found necessary to refresh and replenish the ships, in which case, if Algoa Bay should not afford sufficient means for that purpose, it may be advisable that you should proceed to the Cape of Good Hope, from whence you are to send home the result of your operations to that period, accompanied with whatever information you may have been able to collect.

Having replenished the ships, you are again to proceed to the northward, and, commencing the second part of the survey at Delagoa Bay before-mentioned, continue it along the coasts of Sofala and Mozambique, examining and surveying every bay, harbour, and inlet, and ascertaining the course of all the various rivers that empty themselves into the sea and Mozambique Channel, their size, depth of water, whether navigable or not; and, in short, endeavouring to obtain any information

[page] viii

respecting them that may be practicable, observing that the bay and rivers of Inhamban, the Sofala, and the Quilimaney will require your particular attention; and you are also to survey the several islands which lie near the coasts you shall examine. As this second survey will probably terminate in the Mozambique Channel, or at the farthest at Quiloa, it may be proper to endeavour to replenish your provisions and water at the Portuguese settlement of Mozambique; but failing in this, either from the scantiness of supplies at that settlement, or an unwillingness on the part of the Portuguese authorities established there, it may probably be advisable to try the northern part of Madagascar, where it is stated that the natives are friendly to us, and that cattle is in the greatest abundance. Failing here, the next place that offers itself is the island of Mauritius, where a supply may with confidence be expected. As soon as the two ships shall be in a state to proceed again upon service, you will take up the survey at the point on the coast where it had been discontinued, and carry it on in like manner as before directed to Cape Guadafui, where you are to consider the survey to terminate; but if the ships and ships' companies are in a state to continue in those seas, you may employ them in examining and observing the true position of the numerous islands and shoals between Madagascar and the main and north and north-eastward of Madagascar, and also such parts of the coast of Madagascar as you may conceive not to have been

[page] ix

accurately ascertained; after which you are to return to the Cape, and having there refreshed your crews, make the best of your way to Spithead, reporting your arrival and proceedings to our Secretary for our information. And whilst employed on the service above directed, you are to embrace every opportunity of transmitting to our Secretary an account of your proceedings, and to send to him at such times such results of your labours as the progress you may have made may enable you to furnish.

Given under our hands the 4th of February 1822.

MELVILLE.

G. COCKBURN.

G. CLARK.

To William Fitz William Owen, Esq. Captain of his Majesty's ship Leven, At Spithead.

By command of their Lordships, J. W. CROKER.

Upon the return of the Leven to the Seychelles, in 1824, Captain Owen received the following further instructions from the Hydrographical Office, to continue the survey along the shores of Arabia Felix.

[page] x

No. 2.

Hydrographical Office, May 20, 1823.

DEAR SIR,

The Topaze has lately sent us a sketch of the South Coast of Arabia, from the Red Sea to Dofar, where it joins that made by Captain Smith in the Indian Chart-book, and with which it perfectly agrees. He found some ports, particularly Maculla, forty-five miles out in latitude, but the great error appears to be between Shoal Cliff and Ras-al-Had. Captain Horsburgh in giving the coast the same trending as in other charts, has altered Captain Smith's nearly two degrees more westerly, although that officer's accuracy has been verified by the Topaze and Bacchus. Captain Horsburgh appears to think Ras-al-Had correctly placed in our charts; if so, the coast from Shoal Cliff to Ras-al-Had, must trend north-westerly, instead of north-easterly, which has hitherto been considered the fact. Should your orders permit you to go to Bombay, you might easily settle this to our satisfaction. You will no doubt have the full particulars of Lieutenant West's discovery of the Telemaque shoals, and will be upon the look-out for them. Captain Horsburgh does not believe in their existence; he says, a bank of such extent must have been discovered and examined long before this period,

[page] xi

and as the Lieutenant did not take soundings, he cannot place any confidence in his supposition.

(Signed) P. WALKER.

During the equipment of this expedition, both Captain Owen and his officers were constantly exposed to the frivolous annoyances so often complained of in the administration of our civil departments of the Navy. No office ever defeated the intention of its projectors so perfectly as the Navy Board; for instead of expediting the equipment of his Majesty's ships, they threw every obstacle in the way, either by an ingenious misconstruction or wilful delay. Every application made by Captain Owen to the Admiralty was instantly ordered; while by this Board nothing was granted, however important to the service; every thing obtained from them being after long and constant importunity. Under these circumstances, the Navy in particular, and the public generally, may congratulate themselves upon being no longer burdened with so expensive and unnecessary an establishment; as the duties which they ought to have done are now performed by a branch of the Admiralty.

Upon the second return of this expedition to Seychelles in December 1824, the following letter, together with the annexed memorandum, from the Hydrographical Office, was received by Captain Owen, calling upon him to complete a survey of the west coast of Africa.

[page] xii

No. 3.

Admiralty Office, June 30, 1824.

SIR,

It being the intention of my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, that on your return to England from the surveys in which you have been engaged on the eastern side of Africa, you should employ yourself with the vessels under your orders in making a complete survey of the western coast of Africa, from Cape Mesurado to the River Gambia, and the Bight of Benin; I am commanded by their Lordships to signify their directions to you, to return with the Leven and Barracouta to the Cape of Good Hope, to report their labours in time to enable you afterwards to reach the coast between Cape Mesurado and the Gambia about the middle of November 1825, when you are accordingly to employ yourself in making accurate surveys of the coasts and dangers above mentioned, and having completed the same, you are then to make the best of your way with the said vessels to Spithead, and report your arrival and proceedings for their Lordships' information.

I am further to acquaint you, that a packet containing some charts and a memorandum from the Hydrographical Department of this office for your information, in regard to the surveys above directed on the western coast of Africa, is for-

[page] xiii

warded for you to the naval store-keeper at the Cape of Good Hope, to whom you are to apply for the same.

I am, Sir,

Your very humble Servant,

J. S. BARROW.

MEMORANDUM.

Their Lordships being desirous of having the Coast of Africa, between Sierra Leone, and the River Gambia, with its dangers, completely surveyed, have directed me to give you a detailed account, not only of what we possess, but also of our wants, that you may be the better enabled to fulfil them. I shall also give you a short statement of the whole coast, that you may know what is wanted to complete it.

I should recommend you to begin at Cape Mesurado, a little to the southward of the shoals of St. Ann, where Mr. De Mayne left off. A survey of these shoals lately made by Lieutenant Hagan, will accompany this, which may be of use for you, either to verify or amend if necessary. We know nothing whatever of the river Sierra Leone, as far as is necessary for navigation: it will, therefore, be desirable to obtain the requisite information. The Isles de Loss are frequently resorted to by His Majesty's ships; you have a copy of the only plan we possess, in the first volume of plans you were furnished with, but it is reported to be very erroneous: a survey, therefore, of them, on a good-sized scale, is very

[page] xiv

desirable. The whole coast line from Sierra Leone to Cape Roxa, we know little or nothing about, though it contains the entrances of four large rivers, besides a number of smaller ones, but the most dangerous part is the Bissagos Archipelago, or as they are generally called in the charts, the Shoals of Rio Grande. The French have lately made a survey of the two channels which nearly surround these shoals, the one leading into the Rio Jaba, the other into the Rio Grande, a copy of which accompanies this: you will see they only just touch upon the Islands and Shoals; a more detailed one would be desirable, as far as prudence will allow you to risk your ships.

From Cape Roxo to the River Gambia, being a straight coast and no dangers, you will have little to do, as it was surveyed in a former voyage in the Leven, by Lieutenants Vidal and Mudge, except the entrances of three or four rivers which were thought too insignificant to lose their time about; but the Gambia it will be necessary to survey very minutely, so far up as may be necessary for navigation, it being a place of great trade; and there are said to be many dangers, but which we are totally unacquainted with.

The Coast from the Cape of Good Hope to Benguela, has been fully examined and surveyed by Captain Chapman, of His Majesty's ship Espiegle, and as we have a former survey of that part taken in one of His Majesty's ships, these combined with Mr. De Mayne's survey from Benguela to the Congo, will be fully sufficient for

[page] xv

every purpose of navigation. But from the Congo to the Bight of Benin, we are very defective; it is represented as a straight coast, and I believe no dangers exist on it. Yet it is desirable to have its situation exactly ascertained, and to know what rivers may empty themselves into the sea Within that space. Should you therefore arrive on that part of the coast before the fair weather commences, (about the middle of November,) or be driven away from it before you have completed the survey of that part between Sierra Leone and the Gambia, you might take that opportunity to inspect that between the Congo and the Bight of Benin. When these two objects are accomplished, I conceive the whole western coast of Africa will be sufficiently known for every purpose of navigation.

P. WALKER.

Hydrographical Office,

June 30, 1824.

[page xvi]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

VOL. I.

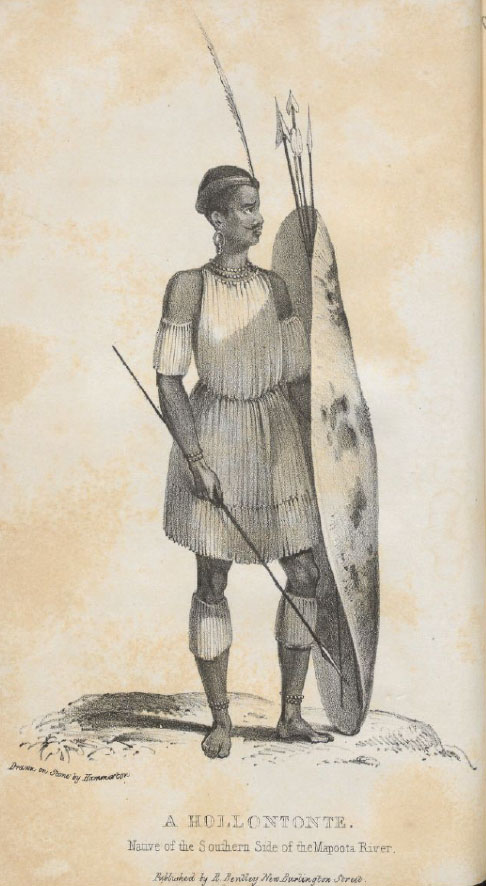

| A Hollontonte | To face the Title |

| Chart of Delagoa Bay | Page 1 |

| Entrance to the Kye River | 75 |

| English Bill | 101 |

| Black Rocks | 281 |

| View of Mombas | 399 |

| Land-Gate, Mombas | 404 |

| Chart of Mombas | 412 |

VOL. II.

| View of Sierra Leone | To face the Title |

| Chart of the Ports of Conducia, Mozambique, and Mokamba | Page 1 |

| Sepulchral Tablet | 78 |

| Native of Madagascar | 87 |

| Radama, King of Madagascar | 119 |

| Chart of the Cape of Good Hope | 224 |

[page xvii]

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Trial of rockets.—The Confiance.—A gale of wind.—Departure from England.—Enter the Tagus.—Chronometers.—Parses over the country.—Astronomical observations.—A man overboard.—Madeira.—Feudal tenure.—Culture of the vines.—Santa Cruz.—A public ball.—St. Patrick.—Deviation of the compass.—Eagles.—Experiment with rockets.—Mr. Forbes's Narrative | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Arrival in Porto Grande.—Joined by the Barracouta.—Tanafal Bay.—Leaving the Bay.—Trinidada.—Geographical falacy.—a French squadron.—The Cockburn steam-boat.—Desertion of seamen.—Country around Rio.—Extracts from the Journal of Mr. John Forbes.—Vegetation at Rio.—Public Garden.—Peculiar oranges.—Boto Fogo.—Botanical garden.— | |

VOL. I. B

[page] xviii

| Excursion by water.—Porto d'Estrella.—Mr. Langsdorff's home.—A little colony.—The Araucanian pine.—Museum of natural history | 28 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| A man overboard.—Towing the Cockburn.—Arrival at the Cape.—Heavy gales.—Survey of the Peninsula.—Desertion.—Dangerous error.—War of extermination.—Kaffer interpreters.—The Cape peninsula.—Barracouta's proceedings.—The Cape Coast.—Bays and harbours.—Insecurity of Table Bay.—Algoa Bay.—Port Elizabeth.—Loss of the Doddington.—Defective charts.—The negro Kaffers.—The Keiskamma River.—Tribes on the coast.—Entrance to English River.—Senhor Oliva.—Native boats.—Boundaries | 51 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Jem of the Water.—Awkward craft.—Personal adornment.—Factory officers.—Intestine war.—Rivers.—Jacket and Fire.—English River.—The River Mattoll.—The River Temby.—Improvidence of the natives.—Traffic with the natives.—A native village.—Termination of the survey.—A hippopotamus.—A night-scene.—A party of natives.—Dress of the chief.—The Hollontontes.—Night-precautions.—Terrific attack.—Defeat of the barbarians.—Return to the boats.—Native warriors | 76 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| English Bill.—Native Secretaries.—Prince Slangelly.—Slangelly's family.—His riches.—Fondness for smoking.—Wretched fugitives.—A group of hippopotami.—A party of natives.—Traps for hippopotami.—Mattoll's people.—Smoking the hubble-bubble.—Infatuation | 101 |

[page] xix

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Quarter-deck market.—Native Liquors.—Death and burial of Mr. Tambs.—Hostilities. A Deserter.—Death of a Seaman.—Portuguese atrocity.—Native feud.—Captain Lechmere's illness and death.—His Servant's illness.—A man lost.—Dangerous situation.—Fresh water.—Trap for Hippopotami | 117 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Fever on board.—Seizure of Roberts.—Mission to King Mayetta.—The royal hut.—Approach of Mayetta.—Interview with Mayetta.—The River Manice.—Parties of Hollontontes.—Interview with them.—Their retreat.—Musquitoes.—Curiosity of the natives.—Two victims to the fever.—Astonishment of the natives.—Timpson's cross.—Increase of fever on board.—Its serious character.—Sufferings of the Sick.—Lieutenant Gibbon's.—Death of Captain Cutfield | 135 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Superstitious fear.—Fatal presentiments.—More victims.—Prudence of the Natives.—Change of Officers.—Track-surveying.—Aspect of the coast.—Naming of places.—Ridge of mountains.—Islands.—French settlements.—Native hair-dressing.—Native costume.—Native dance.—Dexterity of the natives.—Their huts and looms.—Animals and vegetables.—Natural affection.—Laxity of virtue | 155 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The seasons at St. Mary's.—Treatment of fever.—Going on shore.—Landing.—The royal palace.—Interview with the King.—The Prince's-house.—Market on the beach.—Johanna.—Its natives.—Leave Johanna | 175 |

[page] xx

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Mozambique.—Garrison and forts.—The city.—Its population.—Portuguese jurisdiction.—The Governor's house.—Mrs.Guest.—A mutiny.—Senhor Alvarez.—Fraudulent Practices.—A wilful wreck.—Angozha River.—Mohammedan tomb.—Angozha islands.—The coast.—An adventure.—Interior of the country.—Europa Island.—The Cockburn.—Lieutenant Owen's narrative.—The Sincapore.—The Orange Grove.—Unexpected recovery.—Meeting of relatives | 187 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Lieutenant Owen's narrative continued.—Shores of the Mapoota.—Embassy to Makasany.— Interview with him.—His reply.—Hospitality.—Mode of barter.—Exploring party.—Terrific conflagration.—The fatal disorder.—Musquitoes.—Ravages of the fever.—Lieutenant's Owen's illness.—Mr. Tudor, and Cooper.—Fatal result | 212 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The gun-room steward.—Effects of imagination.—Excuses for shipwreck.—Barlow's plate.—English Bill's mimicry.—Superstition.—Natives at dinner.—A native culprit.—Features of the country.—A severe gale.—Algoa Bay.—A mysterious appearance.—The flying Dutchman.—Wreck of the Cockburn.—A Dutch frigate wrecked.—Finishing our charts.—Bill at Cape Town.—Sale of a gift | 229 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Ball on board.—The Albatross.—Missionaries.—Betheldorp and Uitenhage.—Trade with Delagoa.—Perfidy.—Expedition against the Zoolos.—Point Reuben.—Native plants.—An elephant.—A Portuguese Lady.—Cowardly revenge.—Expedition in boats.—Matchakany.—A Portuguese suppliant.—Unburied bodies | 249 |

[page] xxi

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Ascend the Dundas.—Hippopotami.—Imprudence.—The Hunters entrapped.—A liberated Captive.—Seizure of Slaves.—English Merchant-ships.—Shores of the Mapoota.—Hunting Hippopotami.—Regulations for Trading.—Miss the Barracouta.—A new Tribe.—Their Conduct.—A curious Custom.—Traffic | 265 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Meet the Barracouta.—The Black Rocks.—A Critical situation.—Island of Piquena Banca.—Arrival at Quilimane.—Conduct of the Governor.—Origin of the Town.—The Slave-Trade—A gale.—A heavy sea.—Desperate alternative.—Houses in. Quilimane.—Vegetables and Animals.—Mart for Slaves.—Native Marriage.—A bereaved Mother.—Tattooing.—Costume.—Medical treatment | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Anchor recovered.—Bazaruta Islands.—Inhamban.—A rejoicing.—Trade at Inhamban.—Courage of the Natives.—Dance of Women.—A procession.—An oration.—A boat lost.—Shells.—Musical Instruments.—Arrival at Sofala.—The Governor's Deputy.—Ignorant Pilot.—His despondency.—Murderous attempt.—Dr. Guland's wound.—Recover the Guns | 297 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Islands of Boene and Chuluwan.—Rivers of Eastern Africa.—Port of Sofala.—Dr. Cowan.—Early Navigators.—Commandants of Factories.—Whales.—Convivial lizards.—An earth- | |

[page] xxii

| quake.—Sea-birds.—Joys of civilization.—Remarkable meteor.—Naval discipline.—A military officer arrested.—Survey of coast above Zanzibar.—Arrival at Muskat.—The town | 316 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Town of Muskat—The Sultan's horses.—A royal merchant.—Merchant-frigates.—The Sultan's pilgrimage.—Exchange of gifts.—Pearls.—The coast.—A man drowned.—Island of Massera.—Bays.—Islands and reefs.—Erroneous chart.—The north coast.—Abdul Koory.—Its bay | 336 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Cape Guardafui.—Peninsula of Hafoon.—Rocky coast, called Hazine, the Ajan of the maps.—Wreckers.—The Somauli.—The Galla, a wild people.—Mukdeesha.—City of the dead.—Jealousy of strangers.—Treacherous act.—Aspect of the coast.—Devastation.—Tower of Manara.—Rocks and islets.—The Hakeem.—Lamoo.—The Governor's visit.—Arrival at Mombas.—Cession of Mombas and dependencies to Great Britain.—Pemba, or Green Island.—The Perseverance.—Ingratitude.—Ports and Bays.—Bay of Mizimbaty.—Picos Fragos | 353 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Lieut. Boteler's Journal.—Distressed Fugitives.—Steer for Patta.—Native timidity.—Visit from a Chief.—Island of Patta.—Conquest of Patta by the Imaum of Muskat.—Arab Dows. Lamoo.—Buildings and Costume.—Military Weapons.—Arab fortification.—Arab Women.—Education and Food.—Coasting Trade.—The Galla.—Surprise of the Arabs.—A Hog.—Survey to the Southward.—Shooting Elephants.—Dread of Fire-arms.—An accident | 376 |

[page] xxiii

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The Leopard's Bank.—Memorial Pillars.—City of Maleenda.—Its Decline.—Arrival at Mombas.—The Fortress.—Old Portuguese Inscription.—Interior of the Fort.—Decline of Arab Power.—Sheik of Mombas.—Prince of Maleenda.—An of Territory.—The English Flag.—Arab Repast.—Harbour of Mombas.—Commercial Facilities.—History of Mombas.—Going without Arms | 399 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Arrival at Pemba.—Capture of Pemba.—Arrival off Zanzibar.—Harbours.—The Chief's visit.—Deserters.—Unhealthy climate of Zanzibar.—Latham's Island.—Sea-fowl.—Cunning expedient | 425 |

ERRATUM.

For Lieutenant Rozier, read Lieutenant Rogier.

[page break]

[page break]

[page 1]

NARRATIVE OF VOYAGES,

&c.

CHAPTER I.

Trial of rockets.—The Confiance.—A gale of wind.—Departure from England.—Enter the Tagus.—Chronometers.—Parties over the country.—Astronomical observations.—A man overboard.—Madeira.—Feudal tenure.—Culture of the vines.—Santa Cruz.—A public ball.—St. Patrick.—Deviation of the compass.—Eagles.—Experiment with rockets.—Mr. Forbes's Narrative.

AUGUST the 10th, 1821, H. M. S. Leven was commissioned by Captain W. F. W. Owen, who commenced her equipment at Woolwich for a voyage which it was calculated would occupy about four years.

On the 2nd of October a new ten-gun brig, named the Barracouta, was also commissioned by Captain William Cutfield, and placed under the command of Captain Owen; who at the same time had authority to add a smaller vessel to his squadron when on the ground of his operations, as both the Leven and Barracouta drew

VOL. I. B

[page] 2

too much water for many of the services upon which they would be required. As so many operations of surveying are carried on in boats, each vessel was supplied with two additional four-oared gigs expressly fitted for that purpose. It became necessary in consequence of this irregularity in their equipment to distinguish them by proper names. Accordingly they changed their usual appellations of "pinnace, gig, cutter," and "jolly-boat," into Melville, Cockburn, Croker,&c.

Whilst at Woolwich various experiments were made upon the flight of rockets, which had been recommended by Captain Owen to the Admiralty, as a ready and simple method of measuring the difference of longitude between two places not very distant. Sir W. Congreve kindly ordered numerous trials to be made of their efficacy for this purpose; a thirty-two pound rocket sent up from Shooter's Hill was seen at Deal, a distance of about fifty-five geographical miles. It was found that the thirty-two pounders attained a perpendicular height of 6,000 feet, the twenty-four pounders about 4,500, and so in proportion to their magnitude down to the half-pound rocket, which ascended about 2,400 feet, and the quarter-pound 1,500.*

In consequence of the success of these experi-

* We measured these heights by the angle of elevation at Woolwich Warren, the distance from the spot where the rockets were fired being previously ascertained; consequently the correctness of the results depended upon their ascent being perpendicular.

[page] 3

ments, the Admiralty permitted us to embark as many rockets as we could conveniently stow for the proposed purpose.

Both vessels were fitted with Captain Phillips's capstan, to which a fourfold power could be applied if necessary; and also three iron cables instead of one. The equipment and manning the vessels were completed by the 10th of January 1822; when the Leven quitted Woolwich and moored to a buoy at Northfleet; at which place the Barracouta joined her the day following. Here we both took in our guns and powder. The Confiance joined us at this place from Deptford, commanded by Captain Morgan, who was first lieutenant of the Endymion, when she captured the President American frigate. Having fitted out together we naturally felt an interest in one another's fate. The Confiance was on her way to the coast of Ireland, and was not long afterwards wrecked upon the Mizen-head when every soul on board perished. The account of this melancholy event reached us at the Cape of Good Hope in August 1822.

We sailed with a fair wind down the river in company with the Barracouta and Confiance, and took this opportunity to try our sailing properties in smooth water, the Leven having obtained unjust notoriety as a bad sailer; but upon this occasion she beat the Barracouta, and sailed quite as well as the Confiance, much to the disappointment of their respective officers and men.

We remained in the Downs until the 25th,

B 2

[page] 4

during which time we fitted our chain-pumps to work by the capstan, upon a plan suggested by Mr. Edwards, as an economical mode of applying personal labour.

On the 25th we arrived at Spithead, where we experienced a severe gale of wind from the southward, which was so violent as to drive the Euryalus into our hawse. We veered out a whole chain, which being shackled round the main-mast, we endeavoured to clear both at the first and last link, but the joint of the shackle-bolts being rusted in, we were obliged to ride in an extremely dangerous situation with the frigate still driving in our hawse, until the fury of the gale brought our anchor home, much to the joy of all; and when we had drifted far enough from the Euryalus, we brought up in safety by another anchor.

The Horticultural Society, desirous of extending the boundary of human knowledge in natural history, obtained from the Admiralty an order to embark a botanist for this purpose; and here Mr. John Forbes, the gentleman appointed, joined us, with an allowance from the Society of 200l. a year during his absence. After Spithead we anchored in Cowes road, where we were obliged to remain all the next day by a thick fog; but on Wednesday the 13th of February 1822, we passed out to sea by the Needles, and took a farewell of our native shore for some years.

Who can say what varied feelings were stirring at that moment in the breasts of all? Two hundred Britons were leaving the land of their affec-

[page] 5

tions—the soil that had cherished them from infancy, and which was endeared to them by every tie of love, of hope, and of memory—in search of what? Ask the young and thoughtless midshipman, whose tender frame and boyish cheek seem little suited for the adventurous sailor's life, why he leaves his parent's arms to seek a distant, friendless shore? His sanguine imagination will answer—honour, promotion, wealth, and all that fancied something so often seen in the glittering sunshine of romance, but which sad reality so soon blackens into shadow and disappointment. And what says the hardy seaman, as he leaves for so long a time all that he loves—wife—children—friends? he has no romance or hope to light his toilsome course, yet he goes on ever ready and cheerful. But if a tear moisten his eye for those at home—he wipes it from his cheek, and duty calls him to forgetfulness. Had the book of fate been opened to us at that moment, "how many a heart that then was gay" would have seen its fond hopes end, and have shrunk from the distant solitary grave that awaited it! But it was mercifully closed; and curiosity, with the hope of seeing new and strange lands, was the prevailing feeling after we had lost sight of our native soil.

In six days we made Cape Finisterre, and then sailed down the coast of Portugal, passing between the Benling rocks and the main land, taking views of its most interesting features.

[page] 6

The morning of the 23rd we stood into the channel, took a pilot on board, and beat into the Tagus; when, having passed the city, both vessels moored close to the arsenal. Immediately on our arrival, Captain Owen waited on Mr. Ward, our Chargé d'Affaires, through whom he presented to the Minister of Marine, Admiral Quintella, a copy of the Leven's survey of the Cape de Verd islands, made during her former voyage: at the same time requesting directions from the Portuguese ministry to their authorities in Eastern Africa to favour the objects of our present enterprize.

The well-known jealous character of this nation, in regard to her colonies, rendered this proceeding necessary, in order to prevent any misunderstanding whenever we might come in contact with her Colonial officers at places which our orders required us to survey. The Portuguese minister in England had written a letter for the Governor of Mozambique to this effect, but the political changes in the mother country had brought another party into power,—the Cortez at this time reigning almost absolute.

Flattered by the frank manner in which the charts of the Cape de Verd Islands were presented, strong letters to the Governor of Mozambique to render all possible assistance in the prosecution of our labours were furnished us, as well as others to those subordinate to him. The minister Quintella also gave us permission to land our instruments at the arsenal, to make what as-

[page] 7

tronomical observations we required. It was a most important point with us to obtain the rates of our chronometers at this place, as the climate assimilated nearer to that of our future operations, and the extreme precision and care necessary for the required observations could not, in our case, be bestowed upon them in England.

Without considering the great improvements which have taken place in this instrument, and its supposed perfection, Captain Owen felt that, to place implicit confidence in it, might probably be fatal to the correctness and utility of our work: and the result proved the justice of this supposition, for, not one of our nine chronometers kept its rate without fluctuation, produced either by change of weather, climate, or position. In some this variation was very trifling, but in all sufficient to produce much error, unless corrected by a great deal of care and attention. We likewise made daily observations on the deviation of the compass by the vessel's local attraction, the knowledge of which was important, as it was quite a novelty in the practice of navigation: besides, we had not an officer on board who did not require much instruction to obtain the information our future work was likely to demand.

Although we had a great many young officers, yet in astronomical science most of them were mere novices, and almost all were destitute of that elementary knowledge by which it can be acquired. We therefore took advantage of our situation near the arsenal, the liberal permission

[page] 8

of Admiral Quintella, and the polite attentions of Admiral May, the Commissiena, to keep up a continued course of observations, both by day and night, during our stay, principally with a view to acquire the use of the different instruments.

The attentions of Messrs. Ward, the Chargé-d'Affaires, and Jeffereys, the Consul-general, deserve our sincere acknowledgments, as well as those of the Vice-consul, Mr. Phillipps, who was unremitting in his endeavours to meet our wishes in every respect. His brother, Mr. George Phillipps, a young man of twenty, was pilot to our parties over the country in quest of game, plants, scenery, and novelty. In the first, Captain Lechmere and Mr. Forbes were foremost, and the latter forwarded from hence numerous botanical specimens, while Mr. Browne found many subjects for his pencil.

As much of the accuracy with which we hoped to be able to measure the meridian distances, or differences of longitude between the numerous places we were to visit, would depend on the uniformity of the rates of our chronometers, we made a resolution never to fire any of the great guns from the deck on which they were kept, if it could be avoided, nor indeed from either ship any at all, unless in cases where the public service absolutely demanded it; and, immediately on entering the river Tagus, Lieutenant Vidal was dispatched to Mr. Ward, begging him to explain that, being on a voyage of survey, we could

[page] 9

not salute without detriment to our instruments, from which, therefore, we begged to be excused: and, at the same time, obtained the permission we required to make use of the arsenal. It will be seen in the course of this narrative how necessary this precaution was, for we never departed from it without completely deranging our chronometers.

We here obtained the Ephemerides of Coimbra, as far as they were published, as they contain much that is deficient in our own nautical almanack. Having completed our provisions, and obtained all the desired astronomical observations, we sailed from the arsenal on the 4th of March, and beat down the river to Belem, where we anchored for the night, and, on the following morning, at daylight, left the Tagus, taking a long farewell of the coast of Europe.

Whilst at Lisbon the Barracouta was rigged as a bark, on account of the particular service of survey; by removing the main-boom, which would certainly have obstructed those operations, she was rendered more manageable with a reduced crew, which, to us, was a very material consideration, as our boats would very commonly be detached for the critical examination of the coasts and rivers.

By the intercourse of Mr. George Phillipps with our officers a spirit of adventure was awakened, which induced him to solicit Captain Owen to receive him on board, who, finding he was an excellent linguist, and a good scholar in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, acqui-

[page] 10

esced from an anticipation of his utility in the future stages of our voyage.

We had a fair wind to Madeira. The day after our quitting Lisbon, going nine knots, or at the rate of about ten English miles and a half, in an hour, W. Duckett, a seaman, fell from the fore-top-sail-yard; he however swam well and caught hold of the line by which one of Massey's patent buoys was towed. But this giving way, the patent life-buoy was immediately detached from the stern, and the man soon picked up. This adventure excited great admiration amongst some of our English acquaintance at Madeira, and one party, a Mrs. Kerr and friends, whilst taking an evening excursion upon the water, came alongside and requested to see the method by which the poor fellow was saved. The buoy was liberated from the stern of the vessel for their examination, and, when a hundred yards off, the same man Duckett jumped overboard, and swam to it, thus explaining more fully the manner of his escape.

We had a fine run, and on the 8th made Porto Santo by moonlight, at two in the morning, and anchored in Funchall Road at 2 P.M. We took immediate advantage of the kindness of Mr. Veitch, our Consul, by sending the instruments on shore to his garden in the upper part of the town, where he had a neat little cottage; this he gave up entirely to the botanist and officers, who remained there, each being fully occupied in his respective department until the 12th, on

[page] 11

which evening we should have sailed if Captain Owen could have opposed the united solicitations of the English gentlemen and his young officers, for whom a ball and supper had been prepared; but at daylight all were embarked, and both ships were under way.

Madeira is too well-known to require any observations. Many of our officers made excursions into the interior of the island. The botanist, Mr. Forbes, and our second lieutenant, Boteler, set out with several of the younger officers, meaning to visit the highest peak of the island. Their guides, however, misled them, carried them round the Curral, and brought them back again sufficiently fatigued.

The Curral means simply a sheepfold, and is an immense valley, completely surrounded by hills, whose sides are literally perpendicular, in no part being less than 1000 feet high. Round a part of these cliffs is a narrow road, leading to the garden-houses and country plantations, cut out of the rock, about ten or twelve feet wide. Such was the effect of riding along the road over the Curral, which seemed like an unfathomable abyss, filled only by clouds and vapours, rolling in a constant motion over each other, that our party instinctively pressed their horses so close to the rocks to avoid the giddy abyss, that some of them absolutely rubbed the skin off their legs. One only seemed dead to this nervous feeling: this was Captain Lechmere, who skipped from rock to rock on the very edge of the precipice,

[page] 12

with the facility and almost the activity of a goat, to the great terror of the rest of the party, whom the Consul had accompanied to his country house, called the Jardine; a delightful but neglected spot, completely overlooking the part of the coast in the vicinity of Funchall, from which it was distant about nine miles, on an elevation 3000 feet above the sea.

This town is, from its situation on the side of a hill, very clean, and has various marks of opulence and industry. The peasants are an athletic and free race, very laborious and frugal. They hold their lands by a feudal tenure, and cannot be removed from them by the lord, nor can he raise their rent unless he first pay the occupier the full value of every improvement made, such as buildings erected, vines or fruit-trees planted, grounds cleared, &c. which renders it almost equal to copyhold in England, and may perhaps account, in part, for the evident difference in the habits of the Portuguese of Madeira, and of almost every other colony to the southward. Here the meanest subject can acquire and enjoy property; ends never attainable where the wretched system of slavery is established.

The Consul, Mr. Veitch, who was nearly related to the unfortunate Mungo Park, made almost every officer in both vessels grateful for his hospitality. His house was our house in every sense of the word, and his liberality was not singular at this happy little spot, for our merchants all overpowered us with kindness and attention.

[page] 13

In five days no less than three balls were given to us, and every officer who could be spared from duty had invitations daily.

It is seldom expected of sailors to make remarks on the cultivation of land; but one peculiarity in the culture of the vines at Madeira struck us very forcibly, namely, the great depth at which they were planted. The soil is trenched up from three to seven, and even to nine feet, at which depth the roots of the vines are laid and trained thence to the surface. The reason given us was, that some part of the root must be in a moist soil at all times, and the trellis-work, with the vines trained over it, forms a shade for the ground, preventing the exhalation of its moisture, to maintain which seems absolutely necessary to secure a harvest of good grapes. At the Cape of Good Hope the method differs very materially.

We sailed from Funchall Road to the westward, in order to determine the longitude of the extreme western point of Madeira, called Punte del Porgas, which we found to be 17° 15′ 9″. The charts and common plans of the island make it too long from east to west by one third of the actual length of the whole island, and this mistake, considerable as it is, still remains unrectificd. But, although a good survey of the coast of Madeira was evidently wanted, yet, as our orders did not direct it, the Captain was satisfied with obtaining a passing observation for the Iongitude of the above point, to show how much its

[page] 14

magnitude had been mistaken: of which, indeed, he was before partially informed by his brother, Sir Edward Owen, at whose suggestion this inquiry was made.

It being Captain Owen's intention to touch at Santa Cruz to take a stock of wine and cocoa, the opportunity was favourable for measuring the meridian distances to certain points of the Canary Islands. We therefore made all sail with a strong north-east wind for Allegranza, a small island at the north-east end of Lancerote. After beating about these islands for two days, we came to an anchor in the road of Santa Cruz, about 100 yards from the Mole. Our approach was past a line of fishing boats, each of which had a fire of Canary pine at the bow and stern, which produced a beautiful effect; and, as they anchor to fish on the outer verge of the bank, they are good marks for vessels in the night, being sure of soundings when in the same line with the fishermen's lights. Immediately on anchoring they brought their fish alongside for a market. The stock consisted principally of a species of horse-mackerel caught with a rod and line.

It being night when we arrived, we could not land the following morning to take our observations until the health-boat had visited us, which was not until nine o'clock. Lieutenant Boteler was sent to the governor to state our reasons for not saluting, and to obtain his permission to make our observations. Lieutenant Owen and Messrs. Gibbons and Watkins from the Leven,

[page] 15

Lieutenant Mudge and Mr. Hood from the Barracouta, were landed for that purpose with their instruments.

On the following day Mr. Forbes, Lieutenant Boteler, and Mr. Fisher visited Laguna, and picked up some of the curiosities of the island. The next day, being the anniversary of the proclamation of the Constitution, the officers of both vessels were invited to the public ball given on the occasion, many of whom attended. Several of the Spanish gentlemen were in their volunteer uniforms, and seemed highly to value their newly acquired liberties. Many of the ladies were extremely beautiful, and their manners particularly amiable and fascinating, and we all agreed that the Spanish dance was the most rational, pretty, and sociable entertainment of this description we had ever seen. In their manners both sexes are extremely easy and sociable, and so used are all classes to perfect decorum that a master of the ceremonies is unnecessary. The orchestra is composed of amateurs from the company, the ladies taking the piano, and the gentlemen other instruments according to their ability; there seemed to us to be no fixed rule or restraint, yet we did not understand that their harmony was ever disturbed by disagreements among themselves. The ladies were all dressed in the English style, and their strong resemblance to our fair countrywomen in every respect was very striking; and, upon this resemblance being remarked, we were informed that most of them were of English or Irish ex-

[page] 16

traction. The only thing that surprised us was to observe that many of the gentlemen enjoyed their delicious Havannah cigars in the ball-room without offending the ladies' nerves.

In one of the churches may be seen the figure of St. Patrick decked in his original costume of green coat, yellow brogues, blue stockings, covering a purely Irish calf, a small hat stuck on one side of his head so as to leave fair space for a sprig of shillaleh to take effect upon the other; and his hand embellished with as "iligant" a branch of "that same" as ever Donnybrook could boast. His face possessed all the ruby richness so peculiar to his nation; while his sort of "ready-for-anything" attitude conveys an admirable idea of the native activity and archness of a "broth of a boy." It was stated that the ladies of Santa Cruz paid particular attention to this saint, as conveying to them a combined notion of the "sublime and beautiful."

Our gentlemen did not get on board before day-light, and some of them met with trifling losses, such as a sword, a hat, &c. which in those days of general volunteering must have been desirable prizes. The defences of this place, which baffled the daring genius of our Nelson and deprived him of an arm, were at this time in a state of dilapidation; but were it not so, they could never prevent a landing from a good seaforce, because the shores are everywhere approachable within pistol-shot, at which distance no battery can withstand a line-of-battle ship's broadside.

[page] 17

The situation of the town appears badly chosen, as regards anchorage for ships, the communication with the shore, and obtaining water; in all which particulars the next bay, about a mile to the eastward, has great superiority.

All these islands have considerable trade with England, which is much more to their interest than a connection with Spain.

The winds were very light the whole time of our stay, and the last two days the weather was so thick that we could not see the Peak, nor any point sufficiently remote for our observations on the deviation of the compass.

March 20, at four P. M. we weighed, and at five received our officers and their instruments. The Barracouta sailed two hours before us, and proceeded direct for our next rendezvous at the Island of Sal, one of the Cape de Verd islands.

Whenever we were at sea it was our practice to exercise a part of the crew every evening at small-arms, at reefing sails, and to see that every man was clean and sober at his quarters, and as this practice was always continued when circumstances of weather or service did not interfere, it will not be necessary again to make the remark.

In shaping our course for Sal, we steered southwest (a half west), being half a point more to the westward, than the course should have been, had the compass been uninfluenced by the local attraction of the ship, or by what is called deviation. The Barracouta shaped her's without regard to this deviation, which in her was full

VOL. I. C

[page] 18

one point on the south-west: the consequence was, that she was carried considerably to the eastward of her direct course, which prevented her reaching Sal until two days after our arrival. This is mentioned to show the probability that many of the extraordinary currents said to be found in the ocean do not exist; or rather that the discrepancies between the observations and dead reckoning may as frequently be attributed to the unthought-of deviation of the compass as to other occult causes.

On the 25th we were joined by the Barracouta in Mordeira bay of Sal, where we caught a great many most delicious fish. This place is of considerable extent, yet produces little else but salt and orchilla; a few goats contrive to pick up a scanty subsistence, but eagles are particularly abundant.

The means by which these birds obtain their subsistence is strange and apparently an infringement upon the just laws of nature, for, the place being totally devoid of any animal productions suited to their food, they were necessarily much puzzled to make "both ends meet," as our housewives say. They saw the sea-birds enjoying themselves and getting fat by their aquatic excursions. But the lordly eagles could not stoop to fish even for a livelihood; in fact they have an objection to wet feet. Every effort to obtain their winged neighbours was vain on account of their superior fleetness and activity; they soon however discovered that the terror of

[page] 19

their pursuit induced the little divers to relinquish their ocean prey; and now, seated on a rock, they watch them following their finny victims until successful, when they commence their flight to land. The eagle immediately gives chase—the terrified bird drops his spoil, which the piratical pursuer seizes for his own use—thus on this inhospitable spot supporting his lordly character by making the weaker of his own species administer to his will.

Our object in visiting these islands was to verify the longitude of their different points as determined by the Leven during her former survey.

Having landed our astronomers and botanist, an experiment was arranged to be made with the rockets for the purpose of measuring the meridian distance between Sal, St. Nicholas, and St. Vincent, three of the Cape de Verd Islands, to effect which Monte Gardo, eighty geographical miles from Sal and forty from St. Vincent, was fixed upon as the intermediate point for the rockets to be fired; the Barracouta was left in Mordeira bay for three days, and Lieutenant Owen from the Leven remained with her to carry on the astronomical observations.

We sailed in the evening of the 27th, and next morning landed Captain Lechmere, Lieutenant Mudge, who had charge of the party, Mr. Forbes, the botanist, Mr. Ewing, the gunner, Mr. Phillips, the interpreter, and some hands, to proceed to the summit of Monte Gardo, a perpendicular

C 2

[page] 20

height of 4200 feet, about ten miles from the beach where they were landed.

Although the west point of the island is completely sheltered from the prevailing trade winds, yet the rollers and surf were so heavy that our party were obliged to pass through the latter; the only damage they sustained, however, was getting wet, as they contrived to land their instruments, chronometer, provisions, and rockets, uninjured; and they were not long in getting their clothes dry, by stripping and spreading them upon the beach, which was so hot that they could not walk upon it without their shoes.

As soon as the boat returned, we proceeded to St. Vincent, and landed Lieutenant Vidal and Messrs. Gibbon and Browne, at a small cove on the north side of that island, leaving them the jolly-boat to return to the ships in Porto Grande, on the north-west side, where we anchored in the evening before sunset.

As the proceedings of the St. Nicholas party possess some interest, the following account is extracted from the narrative of Mr. Forbes, the botanist:—

As soon as dressed we divided ourselves into two parties to look for asses to carry the baggage. Captain Lechmere and Mr. Mudge found a single hut, under a projecting rock at the bottom of a deep ravine; the only inhabitant seen was a woman, who screamed violently, and ran off at full speed. The news of our landing being thus announced, a negro soon joined the party, who,

[page] 21

being informed of our wants, left us, and in two hours returned with about a dozen asses and as many men to drive them, with whom we agreed to take us to the summit of Monte Gardo, from whence it was intended to fire our rockets.

On our way we passed the village of Praya Branca, (the white plain,) and pitched our tents a little above it, in an enclosure amongst some trees of euphorbium and jatropha. Every creature in the village came forth to see us, and perhaps it was the first time that most of them had ever beheld a white man. It was sunset before we got ourselves in order, when, having eaten a moderate supper from the provisions brought with us, we were all soon asleep.

Praya Branca has about thirty stone-built houses, thatched with reeds: the scenery, being on the side of a stupendous mountain, is both picturesque and magnificent; a small stream of water issues from it near our encampment, and supplies the village: numerous bananas and papayas are planted on the borders of the brook, and cassada and vines on the banks of the valley; these latter grounds are so laid that they can be irrigated, for which purpose the soil is supported on its different levels by stone walls about three feet high. At the spot where irrigation may be required, a temporary dam is made across the brook, and the water trained into it in the rudest manner; being turned into the upper level first, it passes from one to the other, until the whole is saturated. The vines are planted as at

[page] 22

Madeira, and with a similar trellis, about two or three feet above the surface to train them on. Sugar-canes are cultivated in small quantities, but apparently merely to be used in their natural state, as it did not appear that any sugar was manufactured. Bread is made from Indian corn, or maize, and cassada flour.

I had walked out in the morning to collect plants and seeds, and, on my return, found that we could not have asses farther on our journey, nor any assistance from the village, until an order should be received from the Governor. A person had been dispatched to his house, a distance of about twelve miles, to inform him of our arrival and the object of our visit, but was not expected to return for some hours, the road being of the most miserable description, as we afterwards found by experience.

It was intended to fire the rockets from the summit of Monte Gardo in the evening, but the place was still ten miles off, and it was doubtful whether, when the asses came, they could travel the road. We therefore divided the baggage, tent, and rockets amongst us, and resolved upon a pedestrian excursion. Our path lay up a narrow ravine, in many places almost perpendicular, and across bare rocks, where we were obliged to crawl upon our hands and knees. The thermometer was 95° in the shade, and scarcely a breath of wind, so that we had not proceeded far before several of our party found it impossible to carry their loads: seeing two men at work in a vine-

[page] 23

yard we hailed them, and they were induced, for a trifling remuneration, to bear some of our burdens. Still we were obliged to leave many things behind us, with instructions to have them forwarded so soon as the messenger should return with the Governor's permission, of which having no doubt, we had thus far anticipated it.

When we had proceeded about a mile and a half we stopped at a small spring, jetting from the side of the mountain, where I obtained several pretty plants with the assistance of a man that had been gathering orchilla, who had a long stem of reed, (arundo donax,) about sixteen feet long, and a piece of wood at the end, with which he scratched them from the inaccessible parts of the rock.

We reached the top of the first ravine about one o'clock, where we rested after our fatiguing ascent, by a road worse and worse, and the day hotter and hotter, at every step. From the point where we halted the view was magnificent; it overlooked three very considerable valleys, surrounded on every side by stupendous, steep, and rugged mountains, along which it was a novel but pleasing sight to observe the clouds rolling like billows over each other beneath our feet.

From hence the road gradually improved, until our arrival in a village at the foot of Monte Gardo; this place is named Ribeira de Calhao, and consists of about a dozen dwellings, similar to those of Praya Branca. We found the natives extremely civil, poor, and kind; they sold us

[page] 24

milk, eggs, bananas, papaws, and sugar-cane, of which we ate heartily; we also hired two asses to carry the baggage and water.

Our road was now much better than it had been, although the day was hotter; part of it lay through a wood of euphorbium balsamifera: in three hours we reached the summit, and were not a little rejoiced to see a man following with our tent and the baggage we had left behind.

The summit of Monte Gardo does not form a peak like many of the smaller ones on the same island; but, in this last stage, the ascent was tolerably regular and even, and appeared the same on all sides: this circumstance gives it a fuller and more robust appearance, and hence its name, The Fat Mountain.

It is composed entirely of volcanic soil, so fragile and porous that, when taken up in lumps, they fall to pieces with their own weight, like cinders loosely caked together.

It is well clothed with vegetation, even to the summit—the euphorbium balsamifera growing about 3700 feet above the level of the sea and no higher; the bupthalmum sericeum and several others quite to the top. The prospect of the island from this elevated spot is calmly beautiful, a quiet and rustic scene, diversified only by a few humble dwellings, which distance showed in their brightest colours: fancy pictured them the abode of peace and cleanliness, but, like many speculations of that pleasing visio-

[page] 25

nary, the charm was broken upon a nearer acquaintance.

We measured the height by barometer 4380 feet. The tent was pitched upon a little piece of flat ground, under shelter of a rock, but the earth on the summit was so dry, and the wind so strong, that between being nearly blinded and half choked with the dust we got but little sleep: our discomforts were also considerably increased by the thermometer being at 45°.

The sky was too cloudy for the experiments with the rockets, which Mr. Mudge therefore deferred.

During the night our slumbers were most disagreeably interrupted by the sudden disarrangement of our tent; this was occasioned by the soil refusing to hold the pegs with which it was fastened, in opposition to the wind, and in consequence down came the whole construction upon our wearied bodies: with great difficulty we got it again rehoisted, and were enabled to resume our rest.

In the morning we went down to Ribeira de Calhao to breakfast, which consisted of tea, sugar, (which we furnished,) and goat's milk, all boiled together in an iron pot, and drunk out of calabashes, earthenware appearing almost unknown in the island of St. Nicholas. I employed the day in botanizing round the summit of the mountain as far down as the village; but, as this was not the season for flowers, I found very

[page] 26

few specimens which I considered worthy of preserving; in fact, the principal verdure of the island appeared in the euphorbium, which seldom attains a greater height than ten or twelve feet, and is used by the inhabitants for fuel. They here make a soap from the oil of the jatropha, Caucus nuts, and ashes of the burnt papaw-tree leaf; the oil and ashes are mixed in an iron pot, heated over a fire, and stirred until properly blended. When cool it is rolled up into balls, about the size of a six-pound shot, looking much like our mottled soap, and producing a very good lather.

At night, although the atmosphere below us was not altogether so free from clouds as could have been desired, Mr. Mudge thought it sufficiently clear, and we commenced letting off the rockets at one in the morning, which we continued until half-past three. One of them carried a parachute light, which hung suspended above the summit of Monte Gardo, at the height of 6000 feet, upwards of six minutes. But the points from which they were to have been observed were themselves enveloped in the dense haze usual in tropical countries during the dry season, and neither the party at Sal, nor that on St. Vincent's, saw any of these rockets. Although we failed in the object intended, viz. the exact measure of difference of time, they had the effect of terrifying the inhabitants of St. Nicholas, many of whom, at some miles distance, ran from their houses in the belief that a volcano was bursting

[page] 27

forth on the top of Monte Gardo, and even those who had seen our preparations, and were informed of our purpose, were scarcely less terrified. The night was still, and the sound of the large rockets was heard more than twelve miles off.

All our baggage was carried down to Praya Branca in the course of the day, and the tent once more pitched in its valley, under some banana-trees.

In the morning we received a note from the Governor, requesting us to pay him a visit before leaving the island, and most kindly offering any assistance we might require; but, as our time did not admit of this, we requested him to order some asses for our baggage, nine of which joined us at Praya Branca, which we left about eight o'clock in the morning of the 31st, and descended by a much better road than that by which we had come three days before. At eleven o'clock we heard the signal gun for us from the Barracouta, which about noon, upon our arrival on the beach, we answered, and, as the weather was fine and sea smooth, we had little difficulty in our embarcation."

[page] 28

CHAPTER II.

Arrival in Porto Grande.—Joined by the Barracouta.—Tanafal Bay.—Leaving the Bay.—Trinidada.—Geographical fallacy.—A French squadron.—The Cockburn steam-boat.—Desertion of seamen.—Country around Rio.—Extracts from the Journal of Mr. John Forbes.—Vegetation at Rio.—Public Garden.—Peculiar oranges.—Boto Fogo.—Botanical garden.—Excursion by water—Porto d'Estrella.—Mr. Langsdorff's house.—A little Colony.—The Araucanian pine.—Museum of Natural History.

On the Leven's arrival in Porto Grande, we sent on shore to the few houses called a town, at the bottom of the bay, to inform the Governor who we were and what were our wishes. We could only find one miserable Portuguese, the rest being all negroes; but most of them appeared free. The whole population did not exceed a hundred, without any plantations near their houses, as the soil is so very dry and sterile; but on the sides of the mountains, in parts where there is water, they are said to have some good gardens. Indigo grows everywhere wild; and with it they dye the coarse cloths, which they manufacture from cotton which (if ever planted by them)

[page] 29

appears to be left entirely to Nature's cultivation and care.

We pitched a tent upon the beach; cleaned a well in a ravine, which, during the rainy seaaon is a water-course; then landed the woman and a party to wash. During our stay, the sea-breeze every day blew furiously over the hills to the north-east of our anchorage; and although the whole bay is nearly landlocked, yet the surf is very high all round, except in one spot near the town. We therefore only embarked a ton and a half of bad water, and caught a few fish.

Sunday 31st, Lieutenant Vidal, and Messrs. Gibbons and Browne, joined in the hookey from St. Vincent's; and on the following day the Barracouta, from St. Nicholas, with our Monte Gardo party. She brought intelligence of an unfortunate accident which had happened to Lieutenant Reitz, who, whilst standing on an immense mass of rock, taking observations, suddenly found his footing begin to tremble; in some alarm, he attempted to retreat, but before he could do so, the whole fabric fell with him into the abyss beneath. It is surprising that he was not dashed to atoms, although it is true he suffered severely, having a leg dreadfully shattered, and numerous bruises upon other parts of the body. It afterwards appeared that this stone was, by some action of nature, placed upon an exact balance, the one half projecting over the cliff, and the other resting upon the main land. The weight of Lieutenant Reitz was sufficient to give a bias, when the whole fabric "toppled down headlong."

[page] 30

We weighed and followed the Barracouta, coasting the shores of St. Antonio, not more than five hundred yards from the beach, which is a narrow strip of sand, under steep and jutting rocks twelve hundred feet in height. The roadstead is open; but as the wind scarcely ever blows home against the steep cliffs which are so close to the vessels, the anchorage is generally considered safe. Our object here was to obtain water, and to measure the meridian distance.

As this watering place of Tanafal bay is one of the most convenient for that purpose amongst the Cape de Verd Islands, a slight description of it may be desirable. From the high mountains over the bay a small stream descends which is never dry; on the first level spot a large pond has been formed as a reservoir to receive the stream, with a sluice to conduct it to the sands between the flat and the beach, which is a gradual descent: the flat may be about sixty or seventy feet above the level of the sea, and is generally moist and cool. In the vicinity of the pool is a fine plantation of bananas, papayas, &c., and in the lower sandy grounds a cotton plantation, with some trees of the asclepias procera. Just above the beach is a well, and, when the water is let off from the pool, all the soil between it and the well must be saturated before any can arrive at the latter. The reservoir, it appears, was formed with a view to water the plantation only, but the crews of the small trading vessels which take off the orchilla moss dug the well below, rather than

[page] 31

have the trouble of going to the pool. Three huts are used as orchilla stores for Mr. Martinez, who farms that weed.

The negroes at first mistook our vessels for privateers, and would not, therefore, assist us in obtaining water. We were, consequently, obliged to employ our own people to keep it turned into the pool, and to open the sluice to obtain our supplies, which were completed in the course of a day, and the next morning we sailed for St. Jago. In going out of the bay the wind was light, and we warped out by sending a streamanchor a-head, with two hawsers on end, where it was thrown overboard, the boat having had a depth of thirty-five fathoms the instant before; but it appeared to have fallen over a precipitous cliff, similar to that which lined the beach half a mile within it, for the anchor would have carried out cable, seemingly, as long as we would have veered it, and the boat could get no soundings with sixty fathoms: the consequence was, that the hawser was cut through at thirty or forty from the anchor and lost. We inferred from this that the superstructure of this volcanic island was quite similar to that below the surface of the water; in short, that it was but the summit of an immense mountain, whose base may be as far below the surface as if it were an iceberg. As the highest mountain of St. Antonio is eight thousand feet high, and as the mean height of the island may be taken at fifteen hundred, the base may be three or four miles deep. But as

[page] 32

these speculations constituted no part of the object of our voyage, we made the best of our way to Porto Praya.

We were caught between the islands with a calm and thunder squalls, so that we did not get into Porto Praya until the 5th. In the morning we obtained equal altitudes on Quent Island, procured some stock, and at eight o'clock in the evening sailed for Rio Janeiro.

On the 25th we made the rocks of Martin Vas. The Barracouta passed through them, and we made sail for Trinidada. On the 26th, the two vessels coasted that island, which, except at the south-east bay, appeared but a mass of rocks. Many voyagers have described it as having plenty of water and wild hogs, but no good anchorage. We found Peyrouse's longitude near forty-five miles in error: in short, his chronometers must have been bad. The Ninepin Rock, on the west side of the island, appears to be a basaltic column of eight hundred feet in height, and is very remarkable from a slight inclination in its position, which makes it look, from certain points, as if about to fall. A few stumps of euphorbia, and some other shrubs, were scattered over its otherwise barren soil, the neighbourhood of South-east Bay alone bearing an appearance of fertility; but we could not observe any signs of inhabitants.

Several vessels have at different times been wrecked upon this island, and its situation has been laid down with so much uncertainty, that two islands are described near each other under

[page] 33

the names of Aseensao and Trinidada. One object of Peyrouse's voyage appears to have been to establish whether the first-named did exist or not, and he decided clearly in the negative. Captain Owen, however, ran down the parallel to establish the point with more certainty, particularly as it has, since that navigator's time, been positively stated to exist. At Rio he obtained the journal of a whaler, the Swan of Shields, which most decidedly asserted its existence. This ship, during a whaling voyage, had fallen in with an island, at which she watered, in longitude 37° west, or near eight and a half west of Trinidada: a pen-and-ink sketch of the appearance of the island had so striking a resemblance to Trinidada in the point of view assumed, that there could be no doubt of their being the same.

It may be asked what inducement the master of a Whaler could possibly have for such a deception? The answer is easy. He fell in with an island, and his estimated latitude and longitude, carried to Hamilton Moore's table, pointed out Aseensao as that most nearly agreeing with it, and he was himself deceived; but, in making Cape Frio afterwards, and discovering that his longitude differed 8° from that assigned to the Cape, he determined not to permit such a record of his bad reckoning to meet too suddenly the eyes of his owners or others with whom his reputation as a navigator might be of importance.

VOL. I. D

[page] 34

The general appearance of the island is rocky and barren, but we observed in some places symptoms of vegetation. Near the Ninepin Rock are two streams of water, but a tremendous surf was breaking on the shore near them, and the place altogether presented so forbidding an aspect, that we were not tempted to remain for watering or any other purpose.

On the 30th of April we made Cape Frio, when we encountered a heavy gale of wind dead on shore during the night, and the next day arrived at Rio Janeiro, where we found his Majesty's ship Aurora, Captain H. Prescott; also a French squadron, under the command of Commodore the Baron Roussin, consisting of the Amazone, one of the largest class frigates, with a round stern, two other frigates, a store ship, and a schooner. This squadron was employed ostensibly on a survey of the coasts of Brazil, and, as some of their work was published, the Baron presented Captain Owen with a copy. He had also been surveying a part of the coast of Africa, but had overlooked the river Ouro, into which the Leven afterwards sailed; of this river Lieutenant Vidal gave the Baron a copy to add, if he wished, to the French charts.

Our principal object at this place was to purchase a small vessel for a tender and transport, as the Leven could not stow more than sufficient provisions for four months' consumption on full allowance, while the Barracouta had not

[page] 35

stowage for three months, without carrying it upon deck. As the voyages which would be necessary to obtain supplies would very much retard our operations, and as neither of the vessels were calculated for river navigation, Captain Owen purchased an American steam-boat for a trifling sum, which he named the Cockburn, in honour of the Admiral Sir George, one of the Lords of the Admiralty, and she was put under the command of Mr. R. Owen, the junior lieutenant: the equipment of this vessel for sea detained us until the 9th of June. She was 160 tons burthen, and drew under eight feet water, was schooner-rigged, and could be worked with few hands.

The Creole, Commodore Sir Thomas M. Hardy, the Liffey, Commodore Grant, for the East Indies, and the Andromache, Commodore Nourse, for the Cape of Good Hope station, were all here, but the two latter sailed about a week before us.

We employed four boats for a few days to survey a part of the great harbour of Rio Janeiro, and Lieutenant Vidal with great difficulty landed on Raza, where he remained six days to get observations for the situation of the new lighthouse being erected there.

The desertion of seamen at Rio had lately become a great evil; a regular gang of thieves had been long established there, composed principally of desperate English and Irish, who had deserted from different merchant vessels. Some of these

D 2

[page] 36

men were contractors for labour with different planters, who had not sufficient slaves, and indeed could often, by means of these wretches, get what they called free labour much cheaper.

On the arrival of any vessels they find their way on board, paint in glowing colours the wealth and pleasures awaiting free-men on the shores of Brazil, and too commonly succeed in inveigling away most of the crews of merchantmen, and many from ships of war; and the chance of recovering them in so vast a country is but small.

Above twenty of our men, principally the smugglers and malefactors, embarked, by what must be considered a very mistaken policy, on board our ships of war, deserted at different times; but Captain Owen determined if possible to recover them, not so much for their value, as to put a stop to the mischievous display of love of novelty and change so common to British seamen; for which purpose, according to the letter of our treaties, he demanded the aid of the police, which he obtained to cover our proceedings.

Our midshipmen, under the direction of Lieutenant, now Commander Mudge, scoured the whole country for thirty miles in every direction, and from the neighbouring plantations recovered not only our own men, but many others belonging to different ships.

This was effected solely by the enterprize and address of our young officers, who also brought on

[page] 37

board five ringleaders of this gang of desperadoes, nicknamed Robin Hood, Little John, &c. &c. these were punished by our crews, marked by a gallows painted on their clothes, and sent ashore the morning we sailed.

The country around Rio not only presents the most varied and majestic scenery, but is entirely a garden of Nature. Every spot, even of the soil-less rock, is covered with beautiful flowers, very many of which are not to be found enumerated in the general synopsis of botanists. It would appear that botanical science has suffered by the diffidence of travellers in this country, who fearful of multiplying genera, have forced every new plant they found into that to which it appeared to be most nearly allied; for example, there are numerous melastomas, rhesias, tradescantias, &c. differing very materially in the characters which are considered essential to them in the Linnean synopsis.

Our young botanist, Mr. Forbes, was here indefatigable in the service of his honourable employers, the Horticultural Society; he collected about three hundred specimens for his hortus siccus, besides numerous roots and seeds; and his Journal during our stay, which is inserted here, will hardly fail to be read with the interest naturally excited by the untimely death of so young and talented an individual, whose zeal and perseverance would have brought honour upon himself and country.

[page] 38

On entering the harbour of Rio Janeiro, the mind is at once struck with its magnificence and beauty. The vast expanse of water bordered with bright green, the numerous inlets and islands, the rich verdure of the hills, studded with villas, and the lofty chain of mountains, form a dark and distant back-ground, and make altogether a picture more like the poet's fancy than a reality of earth.