VOYAGES

OF THE

ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE.

VOLUME II.

C. Martens. T. Landseer.

FUEGIAN.

(YAPOO TEKEENICA)

AT PORTRAIT COVE

Published by Henry Colburn, Great Marlborough Street, 1838.

NARRATIVE

OF THE

SURVEYING VOYAGES

OF HIS MAJESTY'S SHIPS

ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE,

BETWEEN

THE YEARS 1826 AND 1836,

DESCRIBING THEIR

EXAMINATION OF THE SOUTHERN SHORES

OF

SOUTH AMERICA,

AND

THE BEAGLE'S CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE GLOBE.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1839.

LONDON:

Printed by J. L. COX and SONS, 75, Great Queen Street,

Lincoln's-Inn Fields.

VOLUME II.

PROCEEDINGS

OF

THE SECOND EXPEDITION,

1831—1836,

UNDER THE COMMAND OF

CAPTAIN ROBERT FITZ-ROY, R.N.

CONTENTS.

VOLUME II.

CHAPTER I.

PAGE

Explanation—Natives of Tierra del Fuego, or Fuegians—Passages across the Equator (Atlantic)—Letters—Small-pox—Hospital—Boat—Memory — Fuegians in London — At Walthamstow — At St. James's — Beagle re-commissioned — Correspondence with Mr. Wilson—Fuegians reembark 1

CHAPTER II.

Hydrographer's Opinion — Continuation of Survey — Chain of Meridian Distances — Efficient Arrangements — Repair and raise Deck — Outfit — Boats — Lightning-Conductors—Rudder—Stove—Windlass—Chronometers—Mr. Darwin—Persons on board — Changes — List of those who returned—Supplies—Admiralty Instructions — Memorandum—Hydrographer's Memorandum 17

CHAPTER III.

Ready for sea—Detained—Sail from England—Well provided — Bay of Biscay — Compasses — Local attraction — Eight Stones — Madeira — Deception — Squall — Teneriffe—Santa Cruz—Quarantine—Squalls—Cape Verde Islands—Port Praya—Produce—Orchilla—Bad season—St. Paul Rocks—Cross Equator—Fernando de Noronha—Bahia—Slavery—Abrolhos—Cape Frio 42

CHAPTER IV.

Loss of the Thetis—Causes of her wreck—Approach to Rio de Janeiro — Owen Glendower — Disturbance in Rio Harbour—Observations — Chronometers — Return to Bahia — Deaths — Macacu — Malaria — Return to Rio de Janeiro — Meridian Distances — Regatta — Fuegians — Lightning — Leave Rio — Equipment — Santa Martha — Weather—Santa Catharina—Santos—River Plata—Pamperoes — Gales off Buenos Ayres — Monte Video — Point Piedras — Cape San Antonio — River Plata—Currents—Tides — Barometer — Absence of Trees—Cattle 67

CHAPTER V.

Eastern Pampa Coast — Point Medanos — Mar-chiquito — Ranges of Hills—Direction of Inlets, Shoals, and Rivers—Cape Corrientes—Tosca Coast—Blanco Bay—Mount Hermoso—Port Belgrano—Mr. Harris—Ventana Mountain — View—Argentino—Commandant—Major—Situation—Toriano—Indians—Fossils—Animals—Fish—Climate—Pumice—Ashes—Conway—Deliberations—Consequent Decision—Responsibility incurred—Paz—Liebre—Gale — Hunger — Fossils at Hermoso — Fossils at Point Alta — Express sent to Buenos Ayres — Suspicions and absurd alarm—Rodriguez 97

CHAPTER VI.

Beagle sails with Paz and Liebre — Part company — Beagle visits Buenos Ayres—Nautical remarks on the Plata—Sail from Monte Video for San Blas—Lieut. Wickham and tenders—Butterflies—Sail for Tierra del Fuego— White water — Icebergs — Rocks — Cape San Sebastian—Oens men—Cape San Diego—Good Success Bay—Natives—Guanacoes — Cape Horn — St. Martin Cove — Gales—Heavy Seas—Nassau Bay—Goree Road—Prepare to land Matthews and the Fuegians 114

CHAPTER VII.

Southern Aborigines of South America 129

CHAPTER VIII.

Horse Indians of Patagonia:—Head — Physiognomy—Stature—Wanderings—Clothing—Armour—Arms—Food—Chase—Property—Huts—Wizards—Marriage—Children—Health—Illness—Death—Burial—War—Horsemanship—Gambling—Caciques—Superstitions—Warfare—Morality—Disposition—Chups—Zapallos 144

CHAPTER IX.

Fuegians —Form — Paint — Disposition — Food —Doctor—Religious ideas—Superstitions— Marriage —Death—Burial — Cannibalism — Weapons—Women's occupation — Training — Obtaining food — Fire — Language — Sagacity and local knowledge — Battles — Ceremony — Natives in Trinidad Gulf—Obstruction Sound—Potatoes—Dogs 175

CHAPTER X.

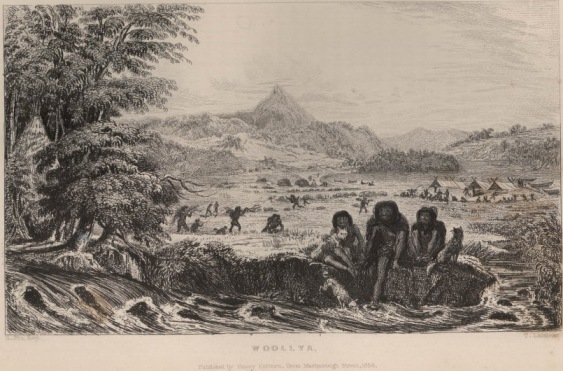

Set out to land Matthews and the Fuegians—Their meeting with Natives—Supposed Volcano—Dream—Oens-men—Scene—Arrival at Woollӯa—Encampment—Concourse of Natives—Jemmy's Family — Wigwams—Gardens—Distrust — Experiment — Westward Exploration — Remove Matthews—Revisit Woollӯa—Gale—Sail for the Falkland Islands 202

CHAPTER XI.

Historical Sketch of the Falkland Islands 228

CHAPTER XII.

First Appearance of Falklands—Tides—Currents—Winds—Seasons—Temperature—Rain—Health—Dangers—Cau-

tions—View—Settlement — Animals — Foxes — Varieties—Seal—Whales—Fish and Fishery—Birds—Brushwood—Peat—Pasture — Potash — Orchilla — Grazing — Corn — Fruit — Vegetables — Trees — Plants — Land—Situation of principal Settlement—Prospective advantages—Suggestions — Vernet's Establishment — Reflections 241

CHAPTER XIII.

Anchor in Berkeley Sound—Le Magellan—British flag hoisted—Ruined Settlement — Mr. Hellyer drowned — Burial—French Whalers—Unicorn—Adventure—Squall—Flashes—Fossils—Killing Wild Cattle—Sail from Falklands—River Negro—Maldonado—Constitucion—Heave down, copper, and refit Adventure — Signs of weather —Sound banks—Los Cesares—Settle with Harris, and part company—Blanco Bay—Return to Maldonado—Monte Video 269

CHAPTER XIV.

Paz and Liebre begin work—Chronometers—Fish—Animals—San Blas—Wrecks—River Negro—Del Carmen—Inhabitants—Indians— Trade— Williams drowned—Port Desire—Gale—Salinas—Lightning—Bones in Tomb—Trees—Dangers—New Bay—Cattle—Seal—Soil—River Chupat—Drift Timber—Fertility—Wild Cattle—Valdes Creek—Imminent danger — Tide Races — Bar of the Negro — Hunting — Attack of Indians — Villarino — Falkner 295

CHAPTER XV.

Beagle and Adventure sail from MonteVideo—Port Desire—Bellaco Rock—Refraction—Port San Julian—Viedma—Drake— Magalhaens — Patagonians — Port Famine — San Sebastian Bay — Woollӯa — Jemmy — Story — Treachery — Oens men — Improvement — Gratitude — Falklands — Events — Capt. Seymour — Search for Murderers — Lieut. Smith —Brisbane —Wreck—Sufferings—Lieutenant Clive—Sail from Falklands 316

CHAPTER XVI.

Soundings — Anchor in Santa Cruz — Lay Beagle ashore for repair — Prepare to ascend river — Set out — View of surrounding country — Rapid stream — Cold — Ostriches—Guanacoes — Indians — Fish — Cliffs — Firewood — Lava Cliffs — Difficulties — Chalia — See Andes — Farthest West — View round — Return — Danger—Guanaco hunters—Puma—Cat—Tides—Sail from Santa Cruz 336

CHAPTER XVII.

Beagle and Adventure sail from Port Famine through Magdalen and Cockburn Channel — Enter Pacific — Death of Mr. Rowlett—Chilóe—Chile— Government — Adventure sold — Consequent changes — Plans — Mr. Low — Chonos—Lieut. Sulivan's party — Moraleda — Ladrilleros — De Vea—Sharp—San Andres—Vallenar — Mr. Stokes — San Estevan—Distressed sailors — Anna Pink Bay — Port Low—Potatoes — Indian names — Huafo — Volcano—Chilotes—Aborigines — Militia — Freebooters— Climate —Docks— Tides — Witchcraft — Alerse — Calbucanos — Cesares — Search for men — Meteors 359

CHAPTER XVIII.

Leave Chilóe — Valdivia — Earthquake — Aborigines — Traditions — Words — Convicts — Tolten — Boroa — Imperial —Mocha — Shocks of Earthquake — Anchor off Talcahuano — Ruins—Account of a great Earthquake, which destroyed the city of Concepcion; and was felt from Chilóe to Copiapó; from Juan Fernandes to Mendoza 396

CHAPTER XIX.

Mocha—Movement of Land — Penco — Ulloa—Shells—Coal—Maule—Topocalma—Aconcagua—Valparaiso—Horcon—Papudo — Pichidanque — Conchali — Herradura — Co-

quimbo— Wreck — Challenger —Blonde—Ride—Estate—Colcura—Villagran—Arauco—Former caciques—Colocolo—Caupolican — Scenery — Quiapo—Night travelling—Leübu—Tucapel—Valdivia—Lautaro—Challenger 419

CHAPTER XX.

Challenger sails—Sounds off Mocha—Wrecked on the mainland—Crew saved—Stores landed—Camp formed—Great exertions, and excellent conduct — Mr. Consul Rouse—Leübu—Plague of mice—Curious rats—Return to Blonde—Ulpu—Araucanian dress—Arauco—'Boroanos'—Tubul—Bar rivers—Apples—Ferry—Blonde sails—Seek for the Leübu — Schooner Carmen — Errors and delay — Embark Challenger's crew — Rescue the Carmen — Talcahuano—New Concepcion — Valparaiso — Coquimbo — Challenger's sail in Conway — Reflections 451

CHAPTER XXI.

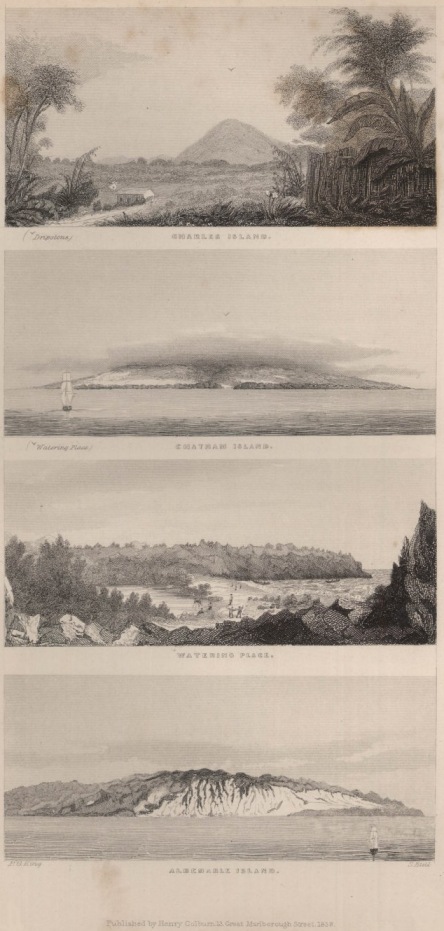

Andes — Aconcagua — Villarica — Islay — Powder—Callao—Rejoin Beagle—Constitucion—Plans—Wilson—Carrasco—'Galäpagos'—Iguanas—Lava Rocks—Land-tortoises—Craters—Turtle—Shells—Dye—Volcanoes—Settlement—Albemarle Island — Cyclopian Scene — Tagus Cove—Tide Ripples—Settlers—Climate—Salt—Dampier—Birds—Transportation of Tortoises — Currents — Temperature of Water 481

CHAPTER XXII.

Dangerous Archipelago of the Low Islands — Krusenstern—Squalls — Discoveries — Otaheite—Matavai—Natives—Houses—Point Venus—Theft—Singing—Pomare—Sugar—Papiete — Church — Mr. Pritchard — Thierry—Shells—Mr. Nott — Bible — Paamuto Natives — Falkner — 'Ua' — Papawa — Relics — Divine Service—Hitote—Henry—Audience—Queen—Missionaries—Roman Catholics—Form-

ing head—Meeting at Papiete—Dress—Behaviour—Eloquence of natives—Honourable feelings — Interesting discussion—Venilia 506

CHAPTER XXIII.

Continuation of the Meeting at Papiete—Questions—Explanation—Meeting ends—Pilotage—Mr. Wilson—Queen's Visit—Fireworks—School—Intelligence—Letters—Inhabitants — Dress — Conduct—Abolition of Spirits—Defect in Character—Domestic Scene—Aura Island — Newton at Bow Island — Pearl Oyster Shells — Divers —Steering—Queen's Letter—Collection—Sail from Otaheite—Whylootacke—Flight of Birds—Navigators—Friendly—Feejee Islands—English Chief—Precautions—La Pérouse 540

CHAPTER XXIV.

New Zealand—Bay of Islands—Kororareka—Fences—Flag—Paihia— Natives — Features — Tattow—Population—Colour—Manner—War-Canoes—Prospects—Mackintosh — Fern — Church — Resident — Vines — Villages — Houses — Planks—Cooking — Church — Marae—First Mission — Settlers — Pomare— Marion — Cawa-Cawa — Meeting — Chiefs — Rats — Spirits— Wine — Nets— Burial — Divine Service—Singing — Causes of Disturbances — Reflections and Suggestions — Polynesian Interests — Resources for Ships in the Pacific 564

CHAPTER XXV.

Waimate — Cultivation — Flax — Apteryx — Gardens — Missionaries — Farm — Barn — Mill — Grave of Shunghi — Horses — Kauri Pine — Keri-keri — Children — Waripoaka — La Favorite — Political condition — Relics — Images, or Amulets—Mats—Leave New Zealand—Remarks—Intercourse — Convicts — Effects of Missionary exertion—Irregular Settlements — Trade — Residents and Consuls —

Missionary Embarrassments — Society's Lands — Discontent of Settlers—Purchase of Land—Influence of Missionaries—Their sphere of action 598

CHAPTER XXVI.

North Cape of New Zealand—Superstitions—Cook's great Lizard — Traditions — Currents — Thermometer — Sydney — Dr. Darwin — Drought — Aqueduct — Position — Disadvantages — Ill-acquired wealth of Convicts, or Emancipists — Hobart Town — Advantages of Van Diemen's Land King George Sound — Natives — Dance—Keeling Islands—Tides — Soundings — Coral formations — Malays — Fish — Weather—Mauritius—Cape of Good Hope—St. Helena — Ascension — Bahia — Pernambuco — Cape Verde Islands—Azores—Arrive in England 619

CHAPTER XXVII.

Remarks on the early migrations of the human race 640

CHAPTER XXVIII.

A very few Remarks with reference to the Deluge 657

DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER

FOR PLACING THE PLATES.

VOLUME II.

| Chart of Tierra del Fuego .. .. .. .. .. | Loose. |

| Chart of Chilóe .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | Loose. |

| Fuegian (Yapoo Tekeenica) .. .. .. .. | Frontispiece. |

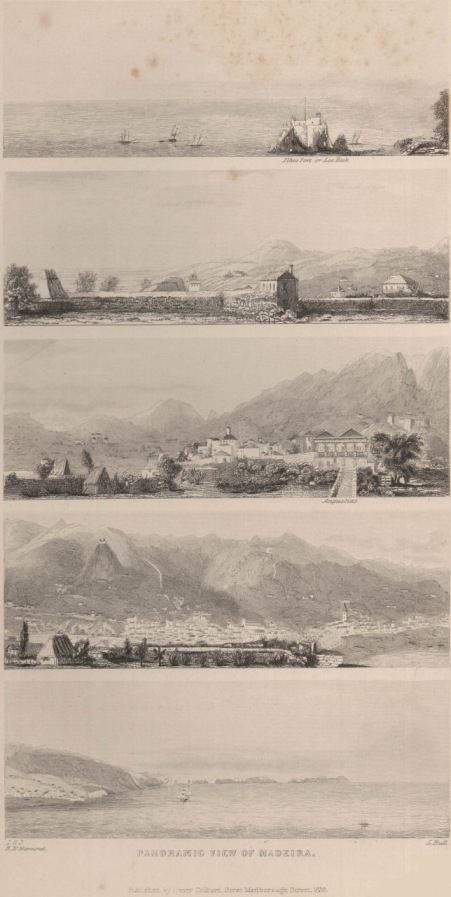

| Panoramic View of Madeira .. .. .. | to face page 46 |

| Crossing the Line .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 57 |

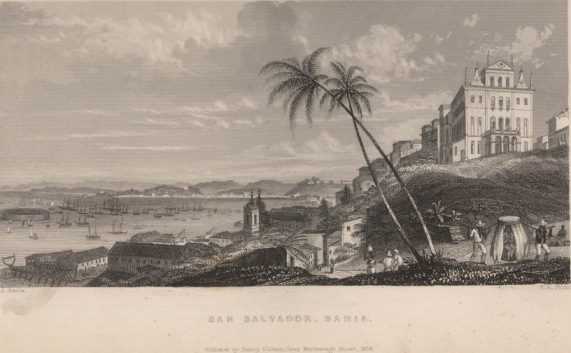

| San Salvador, Bahia .. .. .. .. .. .. | 62 |

| Patagonians at Gregory Bay .. .. .. .. .. | 136 |

| Fuegians— Yacana, Pecheray, &c. .. .. .. .. | 141 |

| Fuegians going to trade in Zapallos with the Patagonians .. | 171 |

| Woollӯa .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 208 |

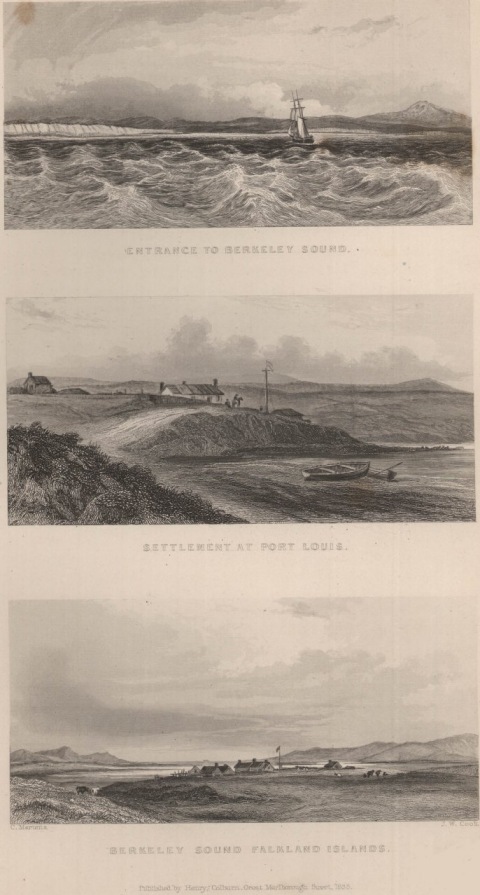

| Berkeley Sound—Falkland Islands .. .. .. .. | 248 |

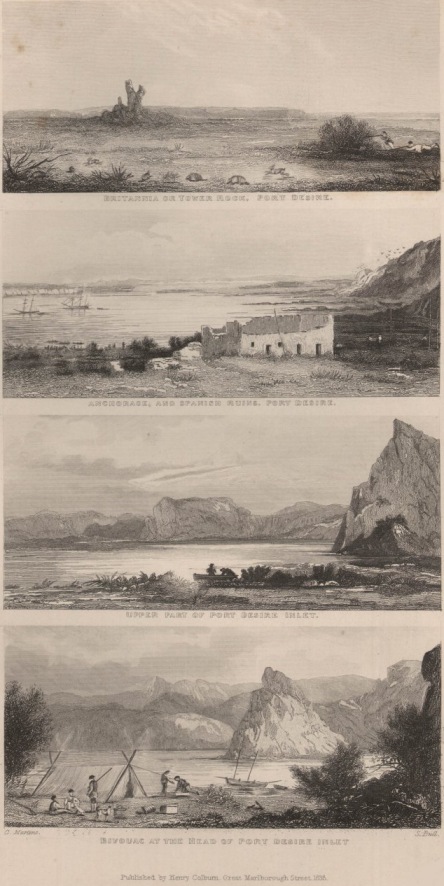

| Bivouac at the Head of Port Desire Inlet .. .. .. | 316 |

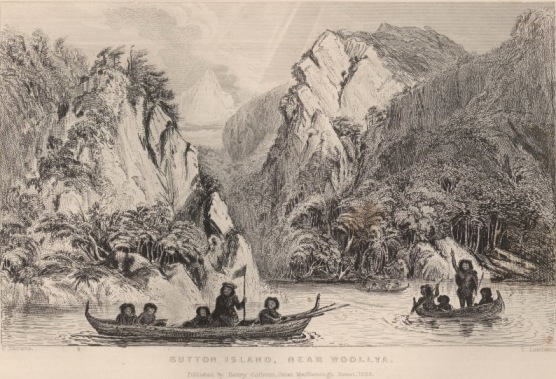

| Button Island, near Woollӯa .. .. .. .. .. | 323 |

| Fuegians—York Minster, &c. .. .. .. .. .. | 324 |

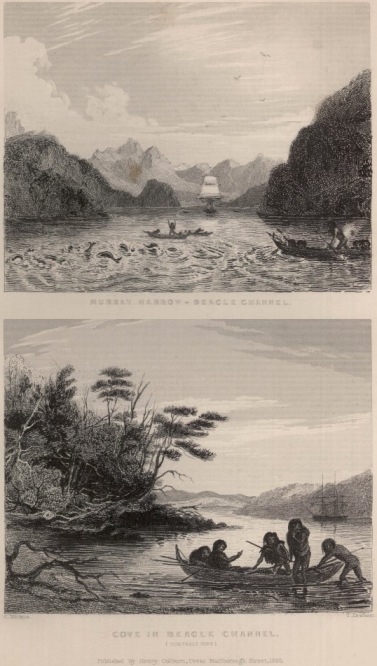

| Cove in Beagle Channel, &c. .. .. .. .. .. | 326 |

| Beagle laid ashore in Santa Cruz .. .. .. .. .. | 336 |

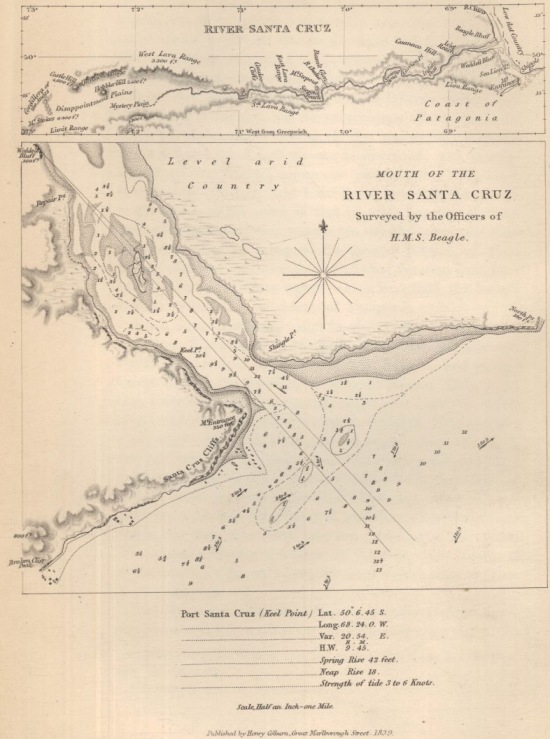

| Santa Cruz—Plan of Port and River .. .. .. .. | 339 |

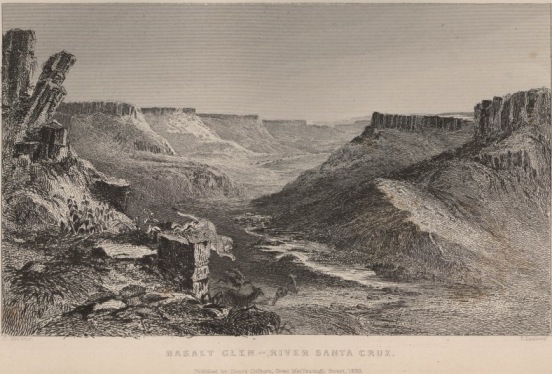

| Basalt Glen — River Santa Cruz .. .. .. .. .. | 348 |

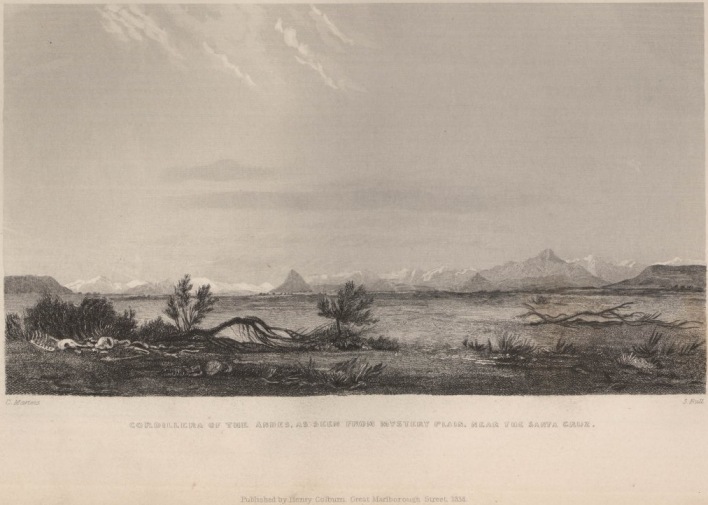

| Santa Cruz River — distant view of Andes .. .. .. | 351 |

| Mystery Plain, near the Santa Cruz .. .. .. .. | 352 |

| Mount Sarmiento, from Warp Bay .. .. .. .. | 359 |

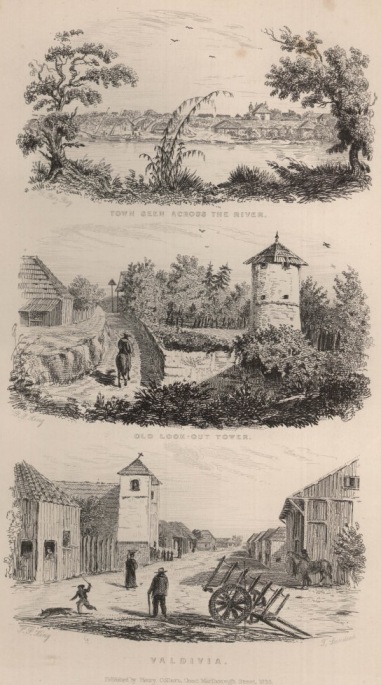

| Valdivia . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. | 398 |

| Remains of the Cathedral at Concepcion .. .. .. | 405 |

| Albemarle Island, &c. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 498 |

| Otaheite, or Tahiti .. .. .. .. .. .. | 509 |

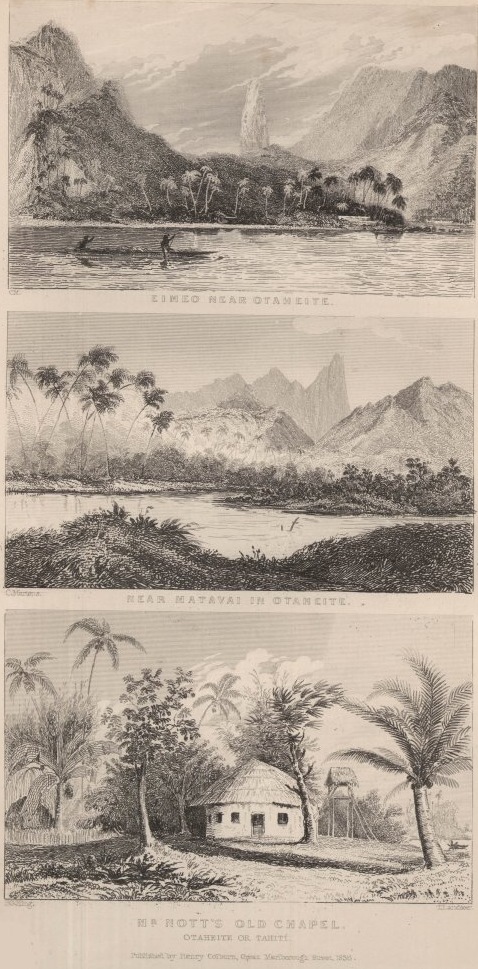

| Otaheite, Eimeo, Matavai, Chapel .. .. .. .. | 517 |

| New Zealanders .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 568 |

NOTE.—The loose Plates are to be folded into pockets in the covers of the volumes.

SURVEYING VOYAGES

OF

THE BEAGLE.

1831 — 1836.

CHAPTER I.

Explanation — Natives of Tierra del Fuego, or Fuegians — Passages across the Equator (Atlantic) — Letters — Small-pox — Hospital — Boat Memory — Fuegians in London — At Walthamstow — At St. James's — Beagle recommissioned — Correspondence with Mr. Wilson — Fuegians re-embark.

As the following narrative of the Beagle's second voyage to South America is a sequel to the "Surveying Voyages of the Adventure and the Beagle," which are related in the preceding volume, it may be advisable that this chapter should contain a sketch of some few incidents intimately connected with the origin and plan of the second Expedition.

Captain King has already mentioned that the two ships under his orders sailed from Rio de Janeiro, on their homeward passage, early in August 1830.

During the time which elapsed before we reached England, I had time to see much of my Fuegian companions; and daily became more interested about them as I attained a further acquaintance with their abilities and natural inclinations. Far,

VOL. II. B

very far indeed, were three of the number from deserving to be called savages—even at this early period of their residence among civilized people — though the other, named York Minster, was certainly a displeasing specimen of uncivilized human nature.

The acts of cannibalism occasionally committed by their countrymen, were explained to me in such terms, and with such signs, that I could not possibly misunderstand them; and a still more revolting account was given, though in a less explicit manner, respecting the horrible fate of the eldest women of their own tribes, when there is an unusual scarcity of food.

This half-understood story I did not then notice much, for I could not believe it; but as, since that time, a familiarity with our language has enabled the Fuegians to tell other persons, as well as myself, of this strange and diabolical atrocity; and as Mr. Low (of whom mention will often be made in the following pages) was satisfied of the fact, from the concurrent testimony of other Fuegians who had, at different times, passed months on board his vessel, I no longer hesitate to state my firm belief in the most debasing trait of their character which will be found in these pages.

At the sea-ports which the Beagle visited in her way from Tierra del Fuego to England, animals, ships, and boats seemed to engage the notice of our copper-coloured friends far more than human beings or houses. When any thing excited their attention particularly, they would appear, at the time, almost stupid and unobservant; but that they were not so in reality was shown by their eager chattering to one another at the very first subsequent opportunity, and by the sensible remarks made by them a long time afterwards, when we fancied they had altogether forgotten unimportant occurrences which took place during the first few months of their sojourn among us.

A large ox, with unusually long horns, excited their wonder remarkably; but in no instance was outward emotion noticed, to any great degree, excepting when they saw a steam-vessel going into Falmouth Harbour. What extraordinary monster it was, they could not imagine. Whether it was a

huge fish, a land animal, or the devil (of whom they have a notion in their country), they could not decide; neither could they understand the attempted explanations of our sailors, who tried to make them comprehend its nature: but, indeed, I think that no one who remembers standing, for the first time, near a railway, and witnessing the rapid approach of a steam-engine, with its attached train of carriages, as it dashed along, smoking and snorting, will be surprised at the effect which a large steam-ship, passing at full speed near the Beagle, in a dark night, must have had on these ignorant, though rather intelligent barbarians.

Before relating occurrences subsequent to our arrival in England, I must ask permission to make the first of a few nautical remarks that will be found in this volume, some of which, I hope, may be useful to young sailors.

Our passage across the Atlantic, from Rio de Janeiro to Falmouth, was unusually long. In order to sail within sight of the Cape Verd Islands, for a particular purpose, we steered eastward from the coast of Brazil, and crossed the equator far east. This course, unavoidable in our case, carried us into that tract of ocean, between the trade-winds, which in August and September is subject to westerly winds—sometimes extremely strong—and we encountered a very heavy gale, although so near the equator. Afterwards, when close to our own shores, we were unfortunate enough to be delayed by what seamen call a hard-hearted easterly wind; and not until the middle of October were we moored in a British port.

As a remarkable contrast, a Falmouth packet, which sailed from Rio de Janeiro some time after our departure, steered northward, as soon as she had cleared the coast of Brazil, crossed the line far to the west, and arrived in England a fortnight before us.

My own humble opinion, with respect to crossing the equator, is, that an outward-bound ship ought to cross near twenty-five — and that one homeward-bound may go even beyond thirty degrees of west longitude—but should not attempt to pass eastward of twenty-five. Ships crossing the line between

B 2

twenty-five and thirty degrees west, are, I believe, far less subject to detention—taking the year through—than those which adopt easterly courses.

Cape St. Roque, St. Paul Rocks, Fernando Noronha, and the Roccas, ought not to be thought of too lightly; but in avoiding them, and the lee current near St. Roque, many ships have encountered the tedious calms, extremely hot weather, frequent torrents of rain, and violent squalls, which are more or less prevalent between the longitudes of twenty and ten degrees west.

To return to the Fuegians. While on our passage home I addressed the following letter to my commanding officer and kind friend, Captain King.

"Sir, Beagle, at sea, Sept. 12, 1830.

"I have the honour of reporting to you that there are now on board of his Majesty's sloop, under my command, four natives of Tierra del Fuego.

"Their names and estimated ages are,

| York Minster | 26 |

| Boat Memory | 20 |

| James Button | 14 |

| Fuegia Basket (a girl) | 9 |

"I have maintained them entirely at my own expense, and hold myself responsible for their comfort while away from, and for their safe return to their own country: and I have now to request that, as senior officer of the Expedition, you will consider of the possibility of some public advantage being derived from this circumstance; and of the propriety of offering them, with that view, to his Majesty's Government.

"If you think it proper to make the offer, I will keep them in readiness to be removed according to your directions.

"I am now to account for my having these Fuegians on board, and to explain my future views with respect to them.

"In February last, the Beagle being moored in 'Townshend Harbour,' on the south-west coast of Tierra del Fuego, I sent Mr. Matthew Murray (master), with six men, in a whale-boat, to Cape Desolation; the projecting part of a small,

but high and rugged island, detached from the main land, and twelve miles distant from Townshend Harbour.

"Mr. Murray reached the place, and secured his party and the boat in a cove near the cape: but during a very dark night, some Fuegians, whose vicinity was not at all suspected, approached with the dexterous cunning peculiar to savages and stole the boat.

"Thus deprived of the means of returning to the Beagle, and unable to make their situation known, Mr. Murray and his party formed a sort of canoe, or rather basket, with the branches of trees and part of their canvas tent, and in this machine three men made their way back to the Beagle, by his directions: yet, although favoured by the only fine day that occurred during the three weeks which the Beagle passed in Townshend Harbour, this basket was twenty hours on its passage.

"Assistance was immediately given to the master and the other men, and a chase for our lost boat was begun, which lasted many days, but was unsuccessful in its object, although much of the lost boat's gear was found, and the women and children of the families from whom it was recovered, were brought on board as hostages. The men, excepting one of them, escaped from us, or were absent in our missing boat.

"At the end of February the Beagle anchored in Christmas Sound; but before this time all our prisoners had escaped, except three little girls, two of whom we restored to their own tribe, near 'Whale-boat Sound,' and the other is now on board.

"From the first canoe seen in Christmas Sound, one man was taken as a hostage for the recovery of our boat, and to become an interpreter and guide. He came to us with little reluctance, and appeared unconcerned.

"A few days afterwards, traces of our boat were found at some wigwams on an island in Christmas Sound, and from the families inhabiting those wigwams I took another young man, for the same purpose as that above-mentioned. No useful information respecting our lost boat was, however, gained from them, before we were obliged to leave that coast, and she remained the prize of their companions.

"Afterwards, when in Nassau Bay, our captives informed us that the natives of that part of the coast, and all to the eastward, were their enemies, and that they spoke a different language. This intelligence was extremely disappointing, and made me anxious to persuade one of this eastern tribe to come on board and stay with us; but I had then no hopes of doing so, and gave up the idea: however, some time afterwards, accidentally meeting three canoes, when away in my boat exploring the Beagle Channel, I prevailed on their occupants to put one of the party, a stout boy, into my boat, and in return I gave them beads, buttons, and other trifles. Whether they intended that he should remain with us permanently, I do not know; but they seemed contented with the singular bargain, and paddled again towards the cove from which they had approached my boat. We pulled on along shore, attended by other canoes, which had been endeavouring to barter with us whenever we stopped; but at dusk they ceased following, us and went ashore.

"When about to depart from the Fuegian coast, I decided to keep these four natives on board, for they appeared to be quite cheerful and contented with their situation; and I thought that many good effects might be the consequence of their living a short time in England. They have lived, and have been clothed like the seamen, and are now, and have been always, in excellent health and very happy. They understand why they were taken, and look forward with pleasure to seeing our country, as well as to returning to their own.

"Should not his Majesty's Government direct otherwise, I shall procure for these people a suitable education, and, after two or three years, shall send or take them back to their country, with as large a stock as I can collect of those articles most useful to them, and most likely to improve the condition of their countrymen, who are now scarcely superior to the brute creation.

"I have, &c.

ROBERT FITZ-ROY,

Commander."

"Phillip Parker King, Esq.

Commander H.M.S. Adventure,

Senior officer of the Expedition."

This letter was forwarded to the Admiralty by Captain King, as soon as he arrived in England; and a few days afterwards the following answer was received.

"Sir, Admiralty Office, 19th Oct. 1830.

"Having laid before my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty your letter and its enclosure from Commander Fitz-Roy, of the Beagle, relative to the four Indians whom he has brought from Tierra del Fuego under the circumstances therein stated; I am commanded to acquaint you that their Lordships will not interfere with Commander Fitz-Roy's personal superintendence of, or benevolent intentions towards these four people, but they will afford him any facilities towards maintaining and educating them in England, and will give them a passage home again.

"I am, &c.

(Signed) JOHN BARROW."

"To Commander King,

H.M.S.V. Adventure."

I was, of course, anxious to protect the Fuegians, as far as possible, from the contagion of any of those disorders, sometimes prevalent, and which unhappily have so often proved fatal to the aboriginal natives of distant countries when brought to Europe; and, immediately after our arrival in England, they landed with me, after dark, and were taken to comfortable, airy lodgings, where, next day, they were vaccinated, for the second time.

Two days afterwards they were carried a few miles into the country, to a quiet farm-house, where I hoped they would enjoy more freedom and fresh air, and, at the same time, incur less risk of contagion than in a populous sea-port town, where curiosity would be excited.

Meanwhile, the Beagle was stripped and cleared out; and the Adventure went to Woolwich for a similar purpose, preparatory to being paid off. On the 27th of October, the Beagle's pendant was hauled down; and on the 15th of November, the Adventure was put out of commission.

Both vessels' crews were dispersed, as usual, unfortunately; and of those who had passed so many rough hours together, but few were likely to meet again. I much regretted the separation from my tried and esteemed shipmates, and from our excellent little vessel.

Soon afterwards, Captain King and Lieutenant Skyring were promoted: a gratifying proof of the good opinion of their exertions and conduct, which was entertained by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

Early in November I received the sad intelligence that the young man, called Boat Memory, was taken ill; and that the symptoms of his disorder were like those of the small-pox. Dr. Armstrong, of the Royal Hospital at Plymouth, whose advice I solicited, suggested that he and the other three Fuegians should be received immediately into the hospital, with the view of preventing further infection, and ensuring the best treatment for the poor sufferer. Dr. Armstrong applied to the physician, Dr. Dickson (now Sir David Dickson), as well as Sir James Gordon, the superintendent, and by their advice and permission the Fuegians were removed into the hospital without delay; and an application was made to the Admiralty, of which the following is a copy.

"Sir, "Devonport, 7th Nov. 1830.

"I have the honour of addressing you to request that the four Fuegians, whom I brought to England in the Beagle, may be received into the Royal Naval Hospital.

"The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty have stated in a letter to Commander King, dated 19th Oct. 1830, that 'their Lordships will not interfere with Commander Fitz-Roy's personal superintendance of, or benevolent intentions towards these four people, but they will afford him any assistance in maintaining and educating them in England, and will give them a passage home again.'

"In consequence of this assurance, I now beg that you will draw their Lordships' attention to the circumstance of an eruption having broken out upon one of the Fuegian men, since he

was vaccinated, which is supposed, by the medical officers of the hospital, to be the small-pox.

"As the other three individuals have been always in company with him, it is to be feared that they also are affected; and as the vaccination has not yet taken a proper effect, it is the opinion of the medical officers that it would be safer to receive them into the hospital, until the present critical period is passed, than to allow them to remain in private care.

"I have further to request, that my late coxswain, James Bennett, may be permitted to accompany, and remain with the Fuegians, in order to attend upon them, in the event of their Lordships allowing them to be admitted into the hospital; and I hope, Sir, that the peculiar nature of the case may be thought to justify this application.

"I have, &c.

ROBERT FITZ-ROY, Commander."

"The Secretary

of the Admiralty.

"Sir, Admiralty-Office, 10th Nov. 1830.

"I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to acquaint you, in answer to your letter of this day's date, that directions have been given for the admission of the four Fuegians therein alluded to, into the Naval Hospital at Plymouth, and that James Bennett be allowed to attend them, agreeably with your request.

"I am, Sir, &c.

"Commander Fitz-Roy. (Signed) "JOHN BARROW."

The Admiralty having thus sanctioned the admission of the Fuegians into one of the best hospitals, and assured that they could not be under better treatment than that of the well-known gentlemen whom I have mentioned, I felt less anxiety in leaving them for a time, as I was obliged to do, in order to attend to duties connected with the survey; but I had hardly reached London, when a letter from Dr. Dickson informed me of the untimely fate of Boat Memory. He had been vaccinated four different times; but the three first opera-

tions had failed, and the last had just taken effect, when the disease showed itself. It was thought that the fatal contagion must have attacked him previously.

This poor fellow was a very great favourite with all who knew him, as well as with myself. He had a good disposition, very good abilities, and though born a savage, had a pleasing, intelligent appearance. He was quite an exception to the general character of the Fuegians, having good features and a well-proportioned frame. It may readily be supposed that this was a severe blow to me, for I was deeply sensible of the responsibility which had been incurred; and, however unintentionally, could not but feel how much I was implicated in shortening his existence. Neither of the others were attacked, the last vaccination having taken full effect; but they were allowed to remain in the hospital for some time longer, until I could make satisfactory arrangements for them. While they were under Dr. Dickson's care, in the hospital, his own children had the measles; and thinking that it would be a good opportunity to carry the little Fuegian girl through that illness, he prepared her for it, and then took her into his house, among his own children; where she had a very favourable attack, and recovered thoroughly.

Of course, I was anxious that no time should be lost in arranging a plan for their education and maintenance; and deeming the Church Missionary Society to be in some measure interested about the project I had in view, I applied to their secretary, through whose kindness I became acquainted with the Rev. Joseph Wigram; to whom I am under great obligations for the friendly interest taken at that time in my wishes with respect to the Fuegians, and for introducing them and myself to the notice of the Rev. William Wilson, of Walthamstow. Mr. Wilson at once relieved my mind from a load of uncertainty and anxiety, by saying that they should be received into his parish, and that he would talk to the master of the Infant School about taking them into his house, as boarders and pupils. In a short time, it was arranged that the school-

master should receive, and take entire charge of them, while they remained in England, and should be paid by me for their board and lodging, for his own trouble, and for all contingent expenses.

Mr. Wilson proposed to keep a watchful eye over them himself, and give advice from time to time to their guardian and instructor. Mr. Wigram also lived at Walthamstow, and as he would have frequent opportunities of offering a useful caution, in case that the numerous calls upon Mr. Wilson's attention should at any time render additional thoughts for the Fuegians an unfair or unpleasant trouble to him—I did indeed think that no plan could be devised offering a better prospect; and immediately made arrangements for conveying them to London.

The inside of a stage-coach was taken, and under the guidance of Mr. Murray (the Beagle's late master), attended by James Bennett, they arrived in Piccadilly, and were immediately carried to Walthamstow, without attracting any notice. Mr. Murray told me that they seemed to enjoy their journey in the coach, and were very much struck by the repeated changing of horses.

I took them myself from the coach-office to Walthamstow; they were glad to see me, but seemed bewildered by the multitude of new objects. Passing Charing Cross, there was a start and exclamation of astonishment from York. 'Look!' he said, fixing his eyes on the lion upon Northumberland House, which he certainly thought alive, and walking there. I never saw him show such sudden emotion at any other time. They were much pleased with the rooms prepared for them at Walthamstow; and the schoolmaster and his wife were equally pleased to find the future inmates of their house very well disposed, quiet, and cleanly people; instead of fierce and dirty savages.

At Walthamstow they remained from December 1830 till October 1831; and during all that time were treated with the utmost kindness by the benevolent men whose names I have mentioned; by their families, and by many others in the

neighbourhood, as well as casual visitors, who became much interested in their welfare, and from time to time gave them several valuable presents.

The attention of their instructor was directed to teaching them English, and the plainer truths of Christianity, as the first object; and the use of common tools, a slight acquaintance with husbandry, gardening, and mechanism, as the second. Considerable progress was made by the boy and girl; but the man was hard to teach, except mechanically. He took interest in smith's or carpenter's work, and paid attention to what he saw and heard about animals; but he reluctantly assisted in garden work, and had a great dislike to learning to read. By degrees, a good many words of their own languages were collected (the boy's differed from that of the man and the girl), and some interesting information was acquired, respecting their own native habits and ideas. They gave no particular trouble; were very healthy; and the two younger ones became great favourites wherever they were known. Sometimes I took them with me to see a friend or relation of my own, who was anxious to question them, and contribute something to the increasing stock of serviceable articles which I was collecting for their use, when they should return to Tierra del Fuego. My sister was a frequent benefactress; and they often talked, both then and afterwards, of going to see 'Cappen Sisser.'

During the summer of 1831, his late Majesty expressed to Colonel Wood a wish to see the Fuegians, and they were taken to St. James's. His Majesty asked a great deal about their country, as well as themselves; and I hope I may be permitted to remark that, during an equal space of time, no person ever asked me so many sensible and thoroughly pertinent questions respecting the Fuegians and their country also relating to the survey in which I had myself been engaged, as did his Majesty. Her Majesty Queen Adelaide also honoured the Fuegians by her presence, and by acts of genuine kindness which they could appreciate, and never forgot. She left the room, in which they were, for a minute, and returned with one

of her own bonnets, which she put upon the girl's head. Her Majesty then put one of her rings upon the girl's finger, and gave her a sum of money to buy an outfit of clothes when she should leave England to return to her own country.

I must now revert to matters more immediately connected with the Beagle's second voyage.

My own official duties, relating to the survey, were completed in March 1831; when my late commanding officer, Captain King, addressed a letter to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty expressive of his approbation of the part I had taken, under his direction, and recommending me to their Lordships.*

From various conversations which I had with Captain King, during the earlier period of my service under him, I had been led to suppose that the survey of the southern coasts of South America would be continued; and to some ship, ordered upon such a service, I had looked for an opportunity of restoring the Fuegians to their native land.

Finding, however, to my great disappointment, that an entire change had taken place in the views of the Lords of the Admiralty, and that there was no intention to prosecute the survey, I naturally became anxious about the Fuegians; and, in June, having no hopes of a man-of-war being sent to Tierra del Fuego, and feeling too much bound to these natives to trust them in any other kind of vessel, unless with myself—because of the risk that would attend their being landed anywhere, excepting on the territories of their own tribes—I made an agreement† with the owner of a small merchant-vessel, the John of London, to carry me and five other persons to such places in South America as I wished to visit, and eventually to land me at Valparaiso.

My arrangements were all made, and James Bennett, who was to accompany me, had already purchased a number of goats, with which I purposed stocking some of the islands of Tierra del Fuego—when a kind uncle, to whom I mentioned

* Appendix.

† Ibid.

my plan, went to the Admiralty, and soon afterwards told me that I should be appointed to the command of the Chanticleer, to go to Tierra del Fuego.

My agreement with the owner of the John was, however, in full force, and I could not alter it without paying a large proportion of the whole sum agreed on for the voyage.

The Chanticleer was not, upon examination, found quite fit for service; and, instead of her, I was again appointed to my well-tried little vessel, the Beagle. My commission was dated the 27th of June, and on the same day two of my most esteemed friends, Lieutenants Wickham and Sulivan, were also appointed.

While the Beagle was fitting out at Devonport, I received the following letter from Mr. Wilson.

"Sir, Walthamstow, 5th Aug. 1831.

"I am informed that the Fuegians who have been lately resident in this place are shortly to return to their native country under your care. Will you permit me to ask whether, if two individuals should volunteer to accompany and remain with them, in order to attempt to teach them such useful arts as may be thought suited to their gradual civilization, you will give them a passage in the Beagle? and whether, upon your arrival on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, you will be able to give them some assistance in establishing a friendly intercourse with, and settlement amongst the natives of that country? Would these individuals be required to pay you for their passage, and maintenance on board? or would his Majesty's Government allow them to be maintained on board at the public expense? Do you think that you would be able to visit them, after their first settlement, supposing so desirable an object should be attained, in order to give them some encouragement, and perhaps assistance; or to remove them if they should find it impracticable to continue their residence among the natives?

"A subscription has been set on foot by gentlemen who are extremely desirous that this opportunity of extending the benefits of civilization should not be lost; and, in consequence of their united wishes, I now take the liberty of asking these questions.

"I am, &c.

(Signed) "WILLIAM WILSON."

"To Captain Fitz-Roy, R.N."

After reading this communication, I wrote to the Secretary of the Admiralty, and enclosed a copy of Mr. Wilson's letter. The answer is subjoined.

"Sir, Admiralty Office, 10th Aug. 1831.

"Having laid before my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty your letter of yesterday's date, with the letter which accompanied it, from the Rev. William Wilson, respecting the natives of Tierra del Fuego who were brought to England in his Majesty's ship Beagle; I am commanded to acquaint you that their Lordships will give the necessary orders for the passage of these individuals, and of the two persons who are to accompany them; and that your request to be allowed to visit these people, after their arrival, will be taken into consideration in preparing your instructions.

"I am, &c.

(Signed) "JOHN BARROW."

"To Commander Fitz-Roy,

"H.M.S. Beagle."

In consequence of this reply, it was wished that two persons should accompany the Fuegians, and endeavour to pass some time in their country: but it was not easy to find individuals sufficiently qualified, and in whom confidence could be placed, who would willingly undertake such an enterprise. One young man was selected by Mr. Wilson, but a companion for him could not be found in time to embark on board the Beagle.

In October the party from Walthamstow arrived, in a

steam-vessel, at Plymouth, and not a few boats were required to transport to our ship the large cargo of clothes, tools, crockery-ware, books, and various things which the families at Walthamstow and other kind-hearted persons had given. In the small hold of the Beagle, it was not easy to find places for the stowage of so many extra stores; and when dividing the contents of large chests, in order to pack them differently, some very fair jokes were enjoyed by the seamen, at the expense of those who had ordered complete sets of crockery-ware, without desiring that any selection of articles should be made.

Instructions were given, by the Secretary of the Church Missionary Society, to the young man who wished to accompany the Fuegians, which will be found in the Appendix; and although he was rather too young, and less experienced than might have been wished, his character and conduct had been such as to give very fair grounds for anticipating that he would, at least, sincerely endeavour to do his utmost in a situation so difficult and trying as that for which he volunteered.

CHAPTER II.

Hydrographer's Opinion—Continuation of Survey—Chain of Meridian Distances—Efficient Arrangements—Repair and raise Deck—Outfit—Boats—Lightning-Conductors—Rudder—Stove—Windlass—Chronometers—Mr. Darwin—Persons on board—Changes—List of those who returned—Supplies—Admiralty Instructions—Memorandum—Hydrographer's Memorandum.

WHEN it was decided that a small vessel should be sent to Tierra del Fuego, the Hydrographer of the Admiralty was referred to for his opinion, as to what addition she might make to the yet incomplete surveys of that country, and other places which she might visit.

Captain Beaufort embraced the opportunity of expressing his anxiety for the continuance of the South American Surveys, and mentioning such objects, attainable by the Beagle, as he thought most desirable: and it was soon after intimated to me that the voyage might occupy several years. Desirous of adding as much as possible to a work in which I had a strong interest, and entertaining the hope that a chain of meridian distances might be carried round the world if we returned to England across the Pacific, and by the Cape of Good Hope; I resolved to spare neither expense nor trouble in making our little Expedition as complete, with respect to material and preparation, as my means and exertions would allow, when supported by the considerate and satisfactory arrangements of the Admiralty: which were carried into effect (at that time) by the Navy Board, the Victualling Board, and the Dockyard officers at Devonport.

The Beagle was commissioned on the 4th of July 1831, and was immediately taken into dock to be thoroughly examined, and prepared for a long period of foreign service. As she required a new deck, and a good deal of repair about the upper works, I obtained permission to have the upper-deck

VOL. II. C

raised considerably,* which afterwards proved to be of the greatest advantage to her as a sea boat, besides adding so materially to the comfort of all on board. While in dock, a sheathing of two-inch fir plank was nailed on the vessel's bottom, over which was a coating of felt, and then new copper. This sheathing added about fifteen tons to her displacement, and nearly seven to her actual measurement. Therefore, instead of 235 tons, she might be considered about 242 tons burthen. The rudder was fitted according to the plan of Captain Lihou: a patent windlass supplied the place of a capstan: one of Frazer's stoves, with an oven attached, was taken instead of a common 'galley' fire-place; and the lightning-conductors, invented by Mr. Harris, were fixed in all the masts, the bowsprit, and even in the flying jib-boom. The arrangements made in the fittings, both inside and outside, by the officers of the Dock-yard, left nothing to be desired. Our ropes, sails, and spars, were the best that could be procured; and to complete our excellent outfit, six superior boats† (two of them private property) were built expressly for us, and so contrived and stowed that they could all be carried in any weather.

Considering the limited disposable space in so very small a ship, we contrived to carry more instruments and books than one would readily suppose could be stowed away in dry and secure places; and in a part of my own cabin twenty-two chronometers were carefully placed.

Anxious that no opportunity of collecting useful information, during the voyage, should be lost; I proposed to the Hydrographer that some well-educated and scientific person should be sought for who would willingly share such accommodations as I had to offer, in order to profit by the opportunity of visiting distant countries yet little known. Captain Beaufort approved of the suggestion, and wrote to Professor Peacock, of Cambridge, who consulted with a friend, Professor Henslow, and he named Mr. Charles Darwin, grandson of Dr. Darwin the poet, as a young man of promising ability,

* Eight inches abaft and twelve forward.

† Besides a dinghy carried astern.

extremely fond of geology, and indeed all branches of natural history. In consequence an offer was made to Mr. Darwin to be my guest on board, which he accepted conditionally; permission was obtained for his embarkation, and an order given by the Admiralty that he should be borne on the ship's books for provisions. The conditions asked by Mr. Darwin were, that he should be at liberty to leave the Beagle and retire from the Expedition when he thought proper, and that he should pay a fair share of the expenses of my table.

Knowing well that no one actively engaged in the surveying duties on which we were going to be employed, would have time—even if he had ability—to make much use of the pencil, I engaged an artist, Mr. Augustus Earle, to go out in a private capacity; though not without the sanction of the Admiralty, who authorized him also to be victualled. And in order to secure the constant, yet to a certain degree mechanical attendance required by a large number of chronometers, and to be enabled to repair our instruments and keep them in order, I engaged the services of Mr. George James Stebbing, eldest son of the mathematical instrument-maker at Portsmouth, as a private assistant.

The established complement of officers and men (including marines and boys) was sixty-five: but, with the supernumeraries I have mentioned, we had on board, when the Beagle sailed from England, seventy-four persons, namely:—

| Robert Fitz-Roy ............... | Commander and Surveyor. |

| John Clements Wickham.......... | Lieutenant. |

| Bartholomew James Sulivan ...... | Lieutenant. |

| Edward Main Chaffers................ | Master. |

| Robert Mac-Cormick ............. | Surgeon. |

| George Rowlett ....................... | Purser. |

| Alexander Derbishire .............. | Mate. |

| Peter Benson Stewart ............. | Mate. |

| John Lort Stokes................ | Mate and Assistant Surveyor. |

| Benjamin Bynoe ................... | Assistant Surgeon. |

| Arthur Mellersh .................. | Midshipman. |

| Philip Gidley King ................ | Midshipman. |

C 2

| Alexander Burns Usborne .......... | Master's Assistant. |

| Charles Musters ....................... | Volunteer 1st Class. |

| Jonathan May ...................... | Carpenter. |

| Edward H. Hellyer ................... | Clerk. |

Acting boatswain: Sergeant of marines and seven privates: thirty-four seamen and six boys.

On the List of supernumeraries were—

| Charles Darwin .................... | Naturalist. |

| Augustus Earle ..................... | Draughtsman. |

| George James Stebbing ................ | Instrument Maker. |

Richard Matthews and three Fuegians: my own steward: and Mr. Darwin's servant.

Some changes occurred in the course of the five years' voyage, which it may be well to mention in this place.

In April 1832, Mr. Mac-Cormick and Mr. Derbishire returned to England. Mr. Bynoe was appointed to act as Surgeon. Mr. Mellersh received a Mate's warrant; and Mr. Johnson joined the Beagle as Midshipman. In May Mr. Musters fell a victim to fever, caught in the harbour of Rio de Janeiro:—Mr. Forsyth took his place.

Mr. Earle suffered so much from continual ill health, that he could not remain on board the Beagle after August 1832; but he lived at Monte Video several months previously to his return to England. The disappointment caused by losing his services was diminished by meeting Mr Martens at Monte Video, and engaging him to embark with me as my draughtsman.

In March 1833, Mr. Hellyer was drowned at the Falkland Islands, in attempting to get a bird he had shot. In September 1833, Mr. Kent joined as Assistant Surgeon. In June 1834, Mr. Rowlett died, at sea, of a complaint under which he had laboured for years: and the vacancy caused by his lamented decease was filled by Mr. Dring.

Mr. Martens left me, at Valparasio, in 1834; and Mr. King remained with his father, at Sydney, in Australia, in February 1836. After these changes, and at our return to England in October 1836, the list stood thus—

| Robert Fitz-Roy ..................... | Captain and Surveyor. |

| John Clements Wickham................ | Lieutenant. |

| Bartholomew James Sulivan ........ | Lieutenant. |

| Edward Main Chaffers............. | Master. |

| Benjamin Bynoe ................. | Surgeon (Acting.) |

| John Edward Dring................ | Purser (Acting.) |

| Peter Benson Stewart .............. | Mate. |

| John Lort Stokes................. | Mate and Assistant Surveyor. |

| Arthur Mellersh ................... | Mate. |

| Charles Richardson Johnson ...... | Mate. |

| William Kent ................ | Assistant Surgeon. |

| Charles Forsyth ................ | Midshipman. |

| Alexander Burns Usborne ............. | Master's Assistant. |

| Thomas Sorrell .................. | Boatswain (Acting.) |

| Jonathan May ..................... | Carpenter. |

And on the List of supernumeraries were Mr. Darwin: George J. Stebbing: my steward: and Mr. Darwin's servant.

Our complement of seamen, marines, and boys was complete at our return, and generally during the voyage; because, although many changes happened, we had always a choice of volunteers to fill vacant places.

Many of the crew had sailed with me in the previous voyage of the Beagle; and there were a few officers, as well as some marines and seamen, who had served in the Beagle, or Adventure, during the whole of the former voyage. These determined admirers of Tierra del Fuego were, Lieutenant Wickham, Mr. Bynoe, Mr. Stokes, Mr. Mellersh, and Mr. King; the boatswain, carpenter, and sergeant; four private marines, my coxswain, and some seamen.

I must not omit to mention that among our provisions were various antiscorbutics—such as pickles, dried apples, and lemon juice—of the best quality, and in as great abundance as we could stow away; we had also on board a very large quantity of Kilner and Moorsom's preserved meat, vegetables, and soup: and from the Medical Department we received an ample supply of antiseptics, and articles useful for preserving specimens of natural history.

Not only the heads of departments exerted themselves for

the sake of our health and safety, but the officers subordinate to them appeared to take a personal interest in the Beagle; for which I and those with me felt, and must always feel, most grateful.

Perhaps no vessel ever quitted her own country with a better or more ample supply (in proportion to her probable necessities) of every kind of useful provision and stores than the little ship of whose wanderings I am now about to give a brief and very imperfect narrative; and, therefore, if she succeeded in effecting any of the objects of her mission, with comparative ease and expedition, let the complete manner in which she was prepared for her voyage, by the Dock-yard at Devonport, be fully remembered.

On the 15th of November I received my instructions from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

INSTRUCTIONS

By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, &c.

"You are hereby required and directed to put to sea, in the vessel you command, so soon as she shall be in every respect ready, and to proceed in her, with all convenient expedition, successively to Madeira or Teneriffe; the Cape de Verde Islands; Fernando Noronha; and the South American station; to perform the operations, and execute the surveys, pointed out in the accompanying memorandum, which has been drawn up under our direction by the Hydrographer of this office; observing and following, in the prosecution of the said surveys, and in your other operations, the directions and suggestions contained in the said memorandum.

"You are to consider yourself under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Baker, Commander-in-chief of his Majesty's ships on the South American station, whilst you are within the limits of that station, in execution of the services

above-mentioned; and in addition to the directions conveyed to you in the memorandum, on the subject of your supplies of provisions, we have signified to the Rear-Admiral our desire that, whenever the occasion offers, you should receive from him and the officers of his squadron, any assistance, in stores and provisions, of which you may stand in need.

"But during the whole time of your continuing on the above duties, you are (notwithstanding the 16th article of the 4th section of the 6th chapter, page 78, of the General Printed Instructions) to send reports, by every opportunity, to our Secretary, of your proceedings, and of the progress you make.

"Having completed the surveys which you are directed to execute on the South American station, you are to proceed to perform the several further operations set forth in the Hydrographer's memorandum, in the course therein pointed out; and having so done, you are to return, in the vessel you command, to Spithead, and report your arrival to our Secretary, for our information and further directions.

"In the event of any unfortunate accident happening to yourself, the officer on whom the command of the Beagle may in consequence devolve, is hereby required and directed to complete, as far as in him lies, that part of the survey on which the vessel may be then engaged, but not to proceed to a new step in the voyage; as, for instance, if at that time carrying on the coast survey on the western side of South America, he is not to cross the Pacific, but to return to England by Rio de Janeiro and the Atlantic.

"Given under our hands, the 11th of November 1831.

(Signed) "T. M. HARDY,

"G. BARRINGTON."

"To Robert Fitz-Roy, Esq.,

Commander of his Majesty's surveying vessel

'Beagle,' at Plymouth."

"By command of their Lordships,

(Signed) "GEO. ELLIOT."

"SIR; Admiralty Office, 11th November 1831.

"With reference to the order which my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty have this day addressed to you, I am commanded by their lordships to transmit to you a memorandum, to be shown by you to any senior officer who may fall in with you, while you are employed on the duties pointed out in the above order.

"I am, Sir, &c.

(Signed) "GEO. ELLIOT."

"To Commander Fitz-Roy,

'Beagle' surveying vessel, Plymouth."

"Admiralty Office, 11th November 1831.

"Memorandum.

"My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty having ordered Commander Fitz-Roy, of his Majesty's surveying vessel the 'Beagle,' to make surveys of various parts of the South American station, it is their lordships' direction that no senior officer who may fall in with Commander Fitz-Roy, while he is employed in the above important duties, do divert him therefrom, or in any way interfere with him, or take from him, on any account, any of his instruments or chronometers.

(Signed) "GEO. ELLIOT."

"Memorandum.

"A considerable difference still exists in the longitude of Rio de Janeiro, as determined by Captains King, Beechey, and Foster, on the one hand, and Captain W. F. Owen, Baron Roussin, and the Portuguese astronomers, on the other; and as all our meridian distances in South America are measured from thence, it becomes a matter of importance to decide between these conflicting authorities. Few vessels will have ever left this country with a better set of chronometers, both public and private, than the Beagle; and if her voyage be made in short stages, in order to detect the changes which take place in all chronometers during a continuous increase of temperature, it will probably enable us to reduce that difference within limits too small to be of much import in our future conclusions.

"With this view, the run to Rio de Janeiro may be conveniently divided into four parts:—

"1st. Touching at Madeira, the exact position of which has been admitted by all parties. Having obtained a four days' rate there, or, if the weather and the exposed anchorage will not permit, at Teneriffe, the Beagle should, 2dly, proceed with the least possible delay to Port Praya, in the Cape de Verde Islands, not only to establish a fresh four days' rate; but that point being the pivot on which all Captain Owen's longitudes turn, no pains should be spared in verifying the position he has assumed for it. From thence, 3dly, she should make the best of her way across the Line to Fernando Noronha. This island, indeed, lies somewhat to the westward of her track, and may retard her progress a little; yet a series of chronometric observations there is essential to the object in view, because it forms the third nearly equal division of the whole run, and because it was the point of junction of Commander Foster's double line of longitudes. If two or three days' delay at either of these two last stations will enable him to obtain satisfactory occultations, and moon culminating observations, which are likely to be seen in this country, the increased certainty of the results will well atone for that loss of time. The Commander will, of course, be careful to adopt, in all those stations, the precise spot of the former observations, with which his are to be compared. The Governor of Fernando Noronha was peculiarly obliging to Commander Foster, and gave up part of his own house for the pendulum experiments. There will be no occasion now for trespassing so heavily on his kindness; but the difference of longitude between that station and Commander Fitz-Roy's must be well measured.

"However desirable it may be that the Beagle should reach Rio de Janeiro as soon as possible, yet the great importance of knowing the true position of the Abrolhos Banks, and the certainty that they extend much further out than the limits assigned to them by Baron Roussin, will warrant the sacrifice of a few days, if other circumstances should enable her to beat down about the meridian of 36° W. from the latitude of

16° S. The deep sea-line should be kept in motion; and if soundings be obtained, the bank should be pursued both ways, out to the edge, and in to that part already known.

"Its actual extent to the eastward, and its connection with the shoals being thus ascertained, its further investigation may be left to more convenient opportunities.

"At Rio de Janeiro, the time necessary for watering, &c. will, no doubt, be employed by the commander in every species of observation that can assist in deciding the longitude of Villegagnon Island.

"It is understood that a French Expedition is now engaged in the examination of the coast between St. Catherine's and the Rio de la Plata; it would therefore be a waste of means to interfere with that interval; and Commander Fitz-Roy should be directed to proceed to Monte Video, and to rate his chronometers in the same situation occupied by Captain King.

"To the southward of the Rio de la Plata, the real work of the survey will begin. Of that great extent of coast which reaches from Cape St. Antonio to St. George's bay, we only know that it is inaccurately placed, and that it contains some large rivers, which rise at the other side of the continent, and some good harbours, which are undoubtedly worth a minute examination. Much of it, however, from the casual accounts of the Spaniards, seems to offer but little interest either to navigation or commerce, and will scarcely require more than to have its direction laid down correctly, and its prominent points fixed. It should nevertheless be borne in mind there, and in other places, that the more hopeless and forbidding any long line of coast may be, the more precious becomes the discovery of a port which affords safe anchorage and wholesome refreshments.

"The portions of the coast which seem to require particular examination are—

"1st. From Monte Hermoso to the Rio Colorado, including the large inlet of Bahia Blanco, of which there are three manuscripts in this office that differ in every thing but in name.

"2dly. The gulf of Todos los Santos, which is studded in the Spanish charts with innumerable islands and shoals. It is said to have an excellent harbour on its southern side, which should be verified; but a minute survey of such an Archipelago would be a useless consumption of time, and it will therefore be found sufficient to give the outer line of the dangers, and to connect that line with the regular soundings in the offing.

"3dly. The Rio Negro is stated to be a river of large capacity, with settlements fifty miles from its mouth, and ought to be partially reconnoitred as far as it is navigable.

"4thly. The gulf of San Matias should be examined, especially its two harbours, San Antonio and San José, and a narrow inlet on the eastern side of the peninsula, which, if easy of access, appears to be admirably situated: and—

"5thly. From the Bahia Nueva to Cape Blanco, including the Gulf of St. George, the coast is of various degrees of interest, and will accordingly require to have more or less time bestowed on its different parts. The position of Cape Blanco should be determined, as there appears to be an error of some miles in its latitude, as well as much doubt about the places of two shoals which are marked near it in the Spanish charts.

"From Cape Blanco to the Strait of Magalhaens, the coast has been partially corrected by Captain King; and Port Desire, having been carefully placed by him, will afford a good place for rating the chronometers, and an opportunity for exploring the river.

"Port San Julian, with its bar and wide river, should be surveyed, as well as any parts of that interval which were not visited in the last expedition.

"The above are the principal points of research between the Rio de la Plata and the Strait. They have been consecutively mentioned in order to bring them into one point of view; but that part of this service would perhaps be advantageously postponed till after the Beagle's first return from the southward; and, generally speaking, it would be unwise to lay down here a specific route from which no deviation

would be permitted. Where so many unforeseen circumstances may disturb the best-concerted arrangements, and where so much depends on climates and seasons with which we are not yet intimately acquainted, the most that can be safely done is to state the various objects of the voyage, and to rely on the Commander's known zeal and prudence to effect them in the most convenient order.

"Applying this principle to what is yet to be done in the Strait, and in the intricate group of islands which forms the Tierra del Fuego, the following list will show our chief desiderata.

"Captain King, in his directions, alludes to a reef of half a mile in length, off Cape Virgins, and in his chart he makes a seven fathoms' channel outside that reef; and still further out, five fathoms with overfalls. Sarmiento places fifty fathoms at ten miles E.S.E. from that Cape; thirteen fathoms at nineteen miles; and, at twenty-one miles in the same direction, only four fathoms, besides a very extensive bank projecting from Tierra del Fuego, between which and the above shoals Malaspina passed in thirteen fathoms. In short, there is conclusive evidence of there being more banks than one that obstruct the entrance to the Strait, and undoubtedly their thorough examination ought to be one of the most important objects of the Expedition; inasmuch, as a safe approach to either straits or harbours is of more consequence to determine than the details inside.

"None of the above authors describe the nature of these shoals, whether rock or sand; it will be interesting to note with accuracy the slope, or regularity, of the depths, in their different faces, the quality of their various materials, and the disposition of the coarse or fine parts, as well as of what species of rock in the neighbourhood they seem to be the detritus; for it is probable that the place of their deposition is connected with the very singular tides which seem to circulate in the eastern end of the Strait.

"Beginning at Cape Orange, the whole north-eastern coast of Tierra del Fuego as far as Cape San Diego should be sur-

veyed, including the outer edge of the extensive shoals that project from its northern extreme, and setting at rest the question of the Sebastian Channel.

"On the southern side of this great collection of islands, the Beagle Channel and Whale-boat Sound should be finished, and any other places which the Commander's local knowledge may point out as being requisite to complete his former survey, and sufficiently interesting in themselves to warrant the time they will cost; such as some apparently useful ports to the westward of Cape False, and the north side of Wakefield Channel, all of which are said to be frequented by the sealers.

"In the north-western part it is possible that other breaks may be found interrupting the continuity of Sta. Ines Island, and communicating from the Southern Ocean with the Strait; these should be fully or cursorily examined, according to their appearance and promise; and though it would be a very useless waste of time to pursue in detail the infinite number of bays, openings, and roads, that teem on the western side of that island, yet no good harbour should be omitted. It cannot be repeated too often that the more inhospitable the region, the more valuable is a known port of refuge.

"In the western division of the Strait, from Cape Pillar to Cape Froward, there are a few openings which may perhaps be further explored, on the chance of their leading out to sea; a few positions which may require to be reviewed; and a few ports which were only slightly looked into during Captain King's laborious and excellent survey, and which may now be completed, if likely to augment the resources of ships occupied in those dreary regions.

"In the eastern division of the Strait there is rather more work to be done, as the Fuegian shore from Admiralty Sound to Cape Orange has not been touched. Along with this part of the service, the Islands of Saints Martha and Magdalena, and the channel to the eastward of Elizabeth Island, will come in for examination; and there is no part of the Strait which requires to be more accurately laid down and distinctly described, from the narrowness of the channels and the trans-

verse direction of the tides. Sweepstakes Foreland may prove to be an Island; if so, there may be found an useful outlet to the long lee-shore that extends from Cape Monmouth; and if not, perhaps some safe ports might be discovered in that interval for vessels caught there in strong westerly gales.

"It is not likely that, for the purposes of either war or commerce, a much more detailed account will be necessary of those two singular inland seas, Otway and Skyring Waters, unless they should be found to communicate with one of the sounds on the western coast, or with the western part of the Strait. The general opinion in the former Expedition was certainly against such a communication, and the phenomena of the tides is also against it; still the thing is possible, and it becomes an interesting geographical question, which a detached boat in fine weather will readily solve.

"These several operations may probably be completed in the summer of 1833-34, including two trips to Monte Video for refreshments; but before we finally quit the eastern coast of South America, it is necessary to advert to our present ignorance of the Falkland Islands, however often they have been visited. The time that would be occupied by a rigorous survey of this group of islands would be very disproportionate to its value; but as they are the frequent resort of whalers, and as it is of immense consequence to a vessel that has lost her masts, anchors, or a large part of her crew, to have a precise knowledge of the port to which she is obliged to fly, it would well deserve some sacrifice of time to have the most advantageous harbours and their approaches well laid down, and connected by a general sketch or running survey. Clear directions for recognizing and entering these ports should accompany these plans; and as most contradictory statements have been made of the refreshments to be obtained at the east and west great islands, an authentic report on that subject by the Commander will be of real utility.

"There is reason to believe that deep soundings may be traced from these islands to the main, and if regular they would be of great service in rectifying a ship's place.

"Having now stated all that is most urgent to be done on this side of the South American Continent as well as in the circuit of Tierra del Fuego, the next step of the voyage will be Concepçion, or Valparaiso, to one of which places the Beagle will have to proceed for provisions, and where Captain King satisfactorily determined the meridian distances.

"The interval of coast between Valparaiso and the western entrance of the Strait has been partly surveyed, as well as most of the deep and narrow channels formed by the islands of Hanover, Wellington, and Madre de Dios; but of the sea face of that great chain of islands which stretches from Queen Adelaide Archipelago to Campana Island, little has yet been done. It presents a most uninviting appearance, can probably afford but little benefit to the navigator, and the chief object in urging its partial examination, is to remove a blank from this great survey, which was undertaken by Great Britain from such disinterested motives, and which was executed by Captains King and Fitz-Roy with so much skill and zeal.

"The experience gained by the latter in that climate will enable him to accomplish all that is now required in much less time than it would have occupied in the beginning of the former expedition.

"At the Gulf of Peñas the last survey terminated. Of the peninsula de Tres Montes, and of the islands between that and Chilóe, a Spanish manuscript has been procured from Don Felipe Bauzá, which may greatly abridge the examination of that interval.

"From thence to Valdivia, Concepçion, and Valparaiso, the shore is straight, and nearly in the direction of the meridian, so that it will require no great expenditure of time to correct the outline, and to fix the positions of all the salient points. Mocha Island is supposed to be erroneously placed: and the depth, breadth, and safety of its channel are not known.

"To the south of Valparaiso the port of Topocalmo and the large shoal in the offing on which an American ship was wrecked, require special examination; and according to Captain Burgess, of the Alert, the coast and islands near Coquimbo

are very imperfectly laid down. Indeed of the whole of this coast, the only general knowledge we have is from the Spanish charts, which seem, with the exception of certain ports, to have been merely the result of a running view of the shore. Of this kind of half-knowledge we have had too much: the present state of science, which affords such ample means, seems to demand that whatever is now done should be finally done; and that coasts, which are constantly visited by English vessels, should no longer have the motley appearance of alternate error and accuracy. If, therefore, the local Governments make no objections, the survey should be continued to Coquimbo, and indefinitely to the northward, till that period arrives when the Commander must determine on quitting the shores of South America altogether. That period will depend on the time that has been already consumed, and on the previous management of his resources, reserving sufficient to ensure his obtaining a series of well-selected meridian distances in traversing the Pacific Ocean.

"The track he should pursue in executing this important duty cannot well be prescribed here, without foreseeing to what part of the coast he may have pushed the survey, and at what place he may find it convenient to take in his last supplies. If he should reach Guayaquil, or even Callao, it would be desirable he should run for the Galapagos, and, if the season permits, survey that knot of islands. Felix Island, the London bank seen by the brig Cannon, in 1827, in 27° 6′ S. 92° 16′ W., even with the water's edge, and half a mile in length; some coral islands, supposed to be 5° or 6° south of Pitcairn Island, and other spots, which have crept into the charts on doubtful authority, would all be useful objects of research if the Beagle's route should fall in their vicinity. But whatever route may be adopted, it should conduct her to Tahiti, in order to verify the chronometers at Point Venus, a point which may be considered as indisputably fixed by Captain Cook's and by many concurrent observations. Except in this case, she ought to avoid as much as possible the ground examined by Captain Beechey.

"From Tahiti the Beagle should proceed to Port Jackson touching at some of the intervening islands, in order to divide the run into judicious chronometer stages; for the observatory at Paramatta (Port Jackson) being absolutely determined in longitude, all those intervening islands will become standard points to which future casual voyagers will be able to refer their discoveries or correct their chronometers.

"From Port Jackson her course will depend on the time of the year. If it be made by the southward, she might touch at Hobart Town, King George Sound, and Swan River, to determine the difference of longitude from thence to the Mauritius, avoiding the hurricane months; to Table or Simon's Bay, according to the season; to St. Helena, Ascension, and home.

"If she should have to quit Port Jackson about the middle of the year, her passage must be made through Torres Strait. In her way thither, if the in-shore route be adopted, there are several places whose positions it will be advantageous to determine:—Moreton Bay, Port Bowen, Cape Flinders, and one of the Prince of Wales Islands; and in pursuing her way towards the Indian Ocean, unless the wind should hang to the southward, Cape Valsche or the south-west extreme of New Guinea, one of the Serwatty Chain, Coupang, or the extreme of Timor, Rotte Island, and one of the extremes of Sandal-wood Island, may be easily determined without much loss of time. And, perhaps, in crossing the ocean, if circumstances are favourable, she might look at the Keeling Islands, and settle their position.

"Having now enumerated the principal places at which the Beagle should be directed to touch in her circuit of the globe, and described the leading operations which it would be desirable to effect, it remains to make some general remarks on the conduct of the whole survey.

"In such multiplied employments as must fall to the share of each officer, there will be no time to waste on elaborate drawings. Plain, distinct roughs, every where accompanied by explanatory notes, and on a sufficiently large scale to show the

VOL. II. D

minutiæ of whatever knowledge has been acquired, will be documents of far greater value in this office, to be reduced or referred to, than highly finished plans, where accuracy is often sacrificed to beauty.

"This applies particularly to the hills, which in general cost so much labour, and are so often put in from fancy or from memory after the lapse of months, if not of years, instead of being projected while fresh in the mind, or while any inconsistencies or errors may be rectified on the spot. A few strokes of a pen will denote the extent and direction of the several slopes much more distinctly than the brush, and if not worked up to make a picture, will really cost as little or less time. The in-shore sides of the hills, which cannot be seen from any of the stations, must always be mere guess-work, and should not be shown at all.