EMMA DARWIN

A CENTURY OF FAMILY LETTERS

EMMA DARWIN A CENTURY OF FAMILY LETTERS

1792-1896

EDITED BY HER DAUGHTER

HENRIETTA LITCHFIELD

IN TWO VOLUMES

ILLUSTRATED

VOL. I

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1915

Serene will be our days and bright,

And happy will our nature be,

When love is an unerring light,

And joy its own security.

And they a blissful course may hold

Even now, who, not unwisely bold,

Live in the spirit of this creed;

Yet seek thy firm support, according to their need.

WORDSWORTH: Ode to Duty.

[All rights reserved]

TO MY NIECE

FRANCES CORNFORD

MY WISE AND SYMPATHETIC COUNSELLOR

IN EDITING THIS BOOK

PREFACE

A NUMBER of family letters (originally in the possession of my aunt, Miss Elizabeth Wedgwood) were found amongst my mother's papers, and were placed in my hands by her executors, my brothers William and George Darwin. Broadly speaking, these letters cover the period during which my grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood, lived at Maer Hall in Staffordshire, and I shall speak of them as the "Maer letters."

After my mother's death I thought that some record of her life and character would be of value to her grandchildren, and with this view began to put down all that I could remember. Whilst reading these old letters in order to get light on her youth and early middle life, I became much interested in the personalities of the writers, and it seemed best to include such of them as are of interest in themselves, as well as those that bear on my mother. The letters written by the Allens (Mrs Josiah Wedgwood and her sisters) fill most of the first volume, and there are but few of my mother's until the second.

The whole mass of letters, on which the early part of this family record is founded, were given to me in a state of absolute confusion. It was the habit of the family to send letters to and from London in boxes of goods despatched from the pottery works at Etruria, hence there is often no postmark; and the writers frequently give only the day of the week or month. During the enforced leisure of

a long illness my husband arranged, dated, and annotated the whole series, a task which required the same sort of minute care and endless patience as the piecing out of a gigantic puzzle.

He read aloud to me every one of the hundreds of letters, and we discussed together what was worth preserving. In the earlier chapters most of the notes are written by him. Some of these may appear superfluous, but it should be remembered that his object was to make the book interesting to the younger members of the Darwin family.

Many omissions are made without putting any sign that this has been done, and neither the punctuation nor the spelling has been rigidly followed.

The pedigrees of the Allen, Wedgwood, and Darwin families, and a list of the principal characters, are given for convenience of reference at the beginning of each volume.

I have received valuable help, criticism, and encouragement from various friends, and especially from Professor A. V. Dicey, Miss M. J. Shaen, my brother Francis, and my niece Mrs F. M. Cornford. To the late Sir John Simon I owe the first idea of this book. Up to the day of his death, in July, 1904, he never ceased to interest himself in its progress. He read the whole in the typewritten copy and followed the proofs as they came from the press.

I wish to thank Mr John Murray for kindly allowing me to give several of the illustrations from More Letters of Charles Darwin; Messrs Elliott and Fry for their permission to make use of the fine portrait of my father in the second volume of that work, and Messrs Barraud for the same permission with regard to their portrait of my mother; Messrs Maull and Fox for allowing me to reproduce an early photograph of my mother; and Mr Prescott Row, the Editor of the Homeland Handbook Association, and Mr G. W. Smith for their kind permission to make use of Mr Smith's photograph of Down Village.

Mrs Vaughan Williams of Leith Hill Place, Mrs Godfrey Wedgwood, Mr Cecil Wedgwood, my brother Horace, and my nephew Charles Darwin, have been so good as to allow me to reproduce various family pictures. I also wish to thank Miss M. J. Shaen for allowing me to use her excellent photograph of my mother, taken in the drawing-room at Down, three months before her death.

These volumes were originally prepared for private circulation only. It was suggested to me by many of those who read them that they would interest a larger public. I have, therefore, prepared them for publication by omitting what was of purely private interest.

H. E. L.

BURROWS HILL,

GOMSHALL,

SURREY.

ERASMUS DARWIN

BORN DECEMBER 7, 1881. KILLED IN ACTION APRIL 24, 1915.

SINCE this book was finished Erasmus Darwin, a grandson of Charles and Emma Darwin, has been killed in action. He was only thirty-three years old, and his life was cut short before all its promise could be fulfilled; but he had already shown himself a man of such rare abilities and so fine and lovable a character that it has been felt that some account of him should be put on record. At the request of his aunt, Mrs. Litchfield, I therefore add to her book this little tribute to his memory. I have made use of a notice already published in The Times, and have supplemented it from letters written by the Commanding Officer and some of the men of Erasmus's battalion, and by those of his friends who can speak of a side of his life of which I have no direct knowledge.

Erasmus was the eldest child and only son of Horace and Ida Darwin, and a grandson on his mother's side of the first Lord Farrer. He was born on December 7, 1881, at Cambridge, which was throughout his life the home of his father and mother. He was in Cotton House at Marlborough, and gained an exhibition for mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. He came up to Trinity in October, 1901, and took the Mathematical Tripos in his second year, being placed among the Senior Optimes. Afterwards he took the Mechanical Sciences Tripos, and was placed in the second class in 1905. On leaving Cambridge, he went through the shops at Messrs. Mather and Platt's at Manchester. After this he worked for some little while with the Cambridge

Scientific Instrument Company, of which he was a director, and then became assistant secretary of Bolckow, Vaughan and Company, Ltd., at Middlesbrough. Here he stayed for seven years, and at the outbreak of war occupied the position of secretary to the company.

As soon as the war broke out, Erasmus decided to join the army, and in September, 1914, he was gazetted a Second-Lieutenant in the 4th Battalion (Territorial) of Alexandra Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment. The Commanding Officer, Colonel Bell, and many of the other officers were among his personal friends at Middlesbrough. The battalion crossed to France, as part of the Northumbrian Division, on April 17, 1915, and was almost immediately called upon to take part in very severe fighting in the neighbourhood of Ypres. It is impossible to give any very accurate or detailed account of the action, but to their honour be it said that these Territorial troops, fresh from home and tried at the very outset almost as highly as men could be tried, played a worthy part in the battle which has earned such undying glory for the soldiers of Canada. They behaved with a steadiness and coolness which gained for them the congratulations of the Generals commanding respectively their Division and their Army Corps. Early in the afternoon of April 24 the regiment had lined some trenches. Later, at about three o'clock, they were withdrawn from the trenches and ordered to attack. This attack they successfully carried out, and drove the enemy back for a mile or more before being ordered to retire about dusk. It was during this advance that Erasmus fell, killed instantaneously. The Royal Irish Fusiliers recovered his body, together with that of his friend, Captain John Nancarrow, and the two lie buried in one grave, with a little cross over it, by a farmhouse near St. Julien.

I cannot do better than quote a letter written to Erasmus's mother by Corporal Wearmouth, who was in his platoon:

"I am a section leader in his platoon, and when we got the order to advance he proved himself a hero. He nursed us men; in fact, the comment was, 'You would say we were

on a field-day." We had got to within twenty yards of our halting-place when he turned to our platoon to say something. As he turned he fell, and I am sure he never spoke. As soon as I could I went to him, but he was beyond human aid. Our platoon sadly miss him, as he could not do enough for us, and we are all extremely sorry for you in your great loss."

To this extract should be added one from a letter written by Private Wood to a friend in Middlesbrough:

"I expect you would know poor Mr. Darwin.... I was in his platoon, and I can tell you he died a hero. He led us absolutely regardless of the bullets from the German Maxim guns and snipers that whistled all round him."

Finally, Colonel Bell, his Commanding Officer, writes of him:

"Loyalty, courage, and devotion to duty—he had them all.... He died in an attack which gained many compliments to the Battalion. He was right in front. It was a man's death."

No soldier could wish a better epitaph. Yet something remains to be said, because soldiering was for Erasmus only a brief and splendid episode. Corporal Wearmouth's letter bears witness not only to his gallantry in the supreme hour of his life, but also to a quality that had been conspicuous throughout its whole previous course, without mention of which no account of him could be complete. He had the most genuine sympathy with and affection for working men, and never tired of trying to help them. And this quality which made him love his work at Middlesbrough brought him the keenest pleasure when soldiering came to him as a wholly new and unlooked-for experience. He delighted in his men, and especially enjoyed long expeditions across the moors, often at night-time, with his Scouts. And the men quickly appreciated his feeling, and responded to it. "The Battalion loved him," says Colonel Bell, "and called him Uncle." It would be hard to find anything more eloquent than that one simple statement.

This gift of sympathy was only one of many that made

his life at Middlesbrough a singularly happy and successful one. He had all the attributes of a good man of business in the best and widest sense. It was impossible to meet him without realizing that he combined with real intellectual power a calm, sound, and practical judgment and a general capacity for doing things well and thoroughly. No one who knew him even slightly could be surprised to hear that his associates in business conceived the highest opinion of him, and that not only on account of his acuteness and administrative ability, but of his fine and high-minded nature. Many words full of praise and affection have been written of this side of his life, and I am sorry that I cannot quote them all. Mr. Storr, who was his predecessor as secretary of Bolckow, Vaughan and Co., writes of him:

"I admired his great abilities as I loved his character.... I (in conjunction with the Chairman of the Company) selected him as my successor, trained him for the position, worked for years in the closest contact and friendship with him, and when I retired did so with the fullest confidence that he had a long and successful career before him, and that the Company could not have chosen a better man."

Dr. J. E. Stead, the distinguished metallurgist of Middlesbrough, who had been his companion on a business tour in America, says:

"During our American tour I got to know him well and find out what he really was. Before that, however, I had learnt that he had ability and intelligence of the highest order.... It was impossible to be with him long without gaining for him a most affectionate regard, and I looked forward and anticipated for him a splendid record of usefulness."

To these two striking pieces of testimony I should like to add one more, not from Middlesbrough, but from London. Mr. E. F. Turner, for many years the friend and solicitor of the Darwin family, who has occupied a distinguished place in his profession and enjoyed a peculiarly wide commercial experience, writes of Erasmus in these terms:

"Looking back on my closed professional experience, he

stands out as the ablest man of his generation that I have ever come across, and his modesty was as great as his mental powers."

A very dear friend of Erasmus, Charles Tennant, who was killed in action only a fortnight later, wrote of him: "There never was, that I ever met, a man so strong and yet so gentle." All who knew him would agree, as they would about another of his qualities, namely, a conscientiousness that was eminently sane and wide-minded, and completely unswerving. No one in the world was more certain to do what he believed to be right. Just before he left England, when his Battalion was under orders for the front, he was summoned to the War Office and offered a Staff appointment at home in connection with munitions of war. This would have given great scope to his capabilities. "It would have been interesting and important work," he wrote, "but of course there are plenty of older men who can do it just as well as I can." He felt that at that moment his place should be with his regiment, and made, in the words of one present at the interview, a "fine appeal" to be allowed to go with his men. It was granted, and he went gladly and with no looking back.

It was, I think, more than anything else this intense feeling for duty that made him so deeply respected, and gained for him in Middlesbrough a very particular position and influence. "There was no one else in his surroundings," writes one of his friends there, "who had the sort of influence he had." I am almost afraid to emphasize this point, lest a wrong impression be given and affection be cast unduly in the shade. He had many devoted friendships, and possessed, as his friend and tutor at Trinity, Dr. Parry, has said, "an unwavering loyalty of affection." Some of his friends of Cambridge days he was only able to see at long intervals, but his feeling for them and theirs for him remained as fresh and warm as ever. He was always simple and natural, and no one could be more wholly delightful and light-hearted than he was when in a holiday mood. He loved the open air and the country, more especially the north country, and

Yorkshire best of all. Fishing had been a source of the very keenest pleasure to him ever since he was a boy. Some will have memories of long days of walking in the Lakes; others of the jolly times of the May week at Cambridge—of dances and early morning rides and expeditions up the river in Canadian canoes. Whether we think of him at work or at play, we cannot remember a word or an action that does not make us proud of him. He is only one of many as to whom it may be said that they would have done much; but whatever he might have achieved, he never could have left a memory more lovable or more honourable.

BERNARD DARWIN.

May 19, 1915.

CONTENTS OF VOLUME I

CHAPTER I.

1792—1800.

Emma Wedgwood—The Allens of Cresselly—Sir James Mackintosh—The Wedgwoods and Darwins—Josiah Wedgwood's marriage—A ball at Ramsgate—Tom Wedgwood's ill-health—The Wedgwoods at Gunville . . . . . 1—19

CHAPTER II.

1804—1807.

John Hensleigh Allen inherits Cresselly—Departure of the Mackintoshes for India—A press-gang story—Tom Wedgwood's death—Return of the Josiah Wedgwoods to Staffordshire—Sarah Wedgwood and Jessie Allen . . . . 20—29

CHAPTER III.

1813—1814.

John Allen's marriage—Jessie, Emma, and Fanny Allen at Dulwich—The Mackintoshes in Great George Street—An escapade of the Duke of Brunswick—London parties and Madame de Staël . . . . . . . . . 30—50

CHAPTER IV.

MAER.

Maer Hall—The children of Josiah Wedgwood—A picnic at Trentham—Emma Caldwell's picture of life at Maer—Emma Darwin's comment seventy-two years later—Emma's childhood 51—62

CHAPTER V.

1814—1815.

The Prudent Man's Friend Society—The John Wedgwoods and Drewes at Exeter—The Battle of Waterloo—Ensign Tom Wedgwood's letters from Waterloo and Paris—Fanny Allen's pro-Buonapartism—The Maer party at a Race ball . 63—76

CHAPTER VI.

1815—1816.

The Allen sisters abroad—Paris after Waterloo—Fanny Allen and William Clifford—Harriet Drewe's engagement to Mr Gifford—A family gathering at Bath—Sarah Wedgwood's love-affairs—Bessy visits Mrs Surtees—Geneva society—The Sydney Smiths at Etruria—Kitty Mackintosh and her daughters—The Allen sisters" journey to Florence . . . 77—98

CHAPTER VII.

1816.

The crisis in Davison's Bank—Its failure averted—The loss of the John Wedgwood's fortune—Their move to Betley . 99—102

CHAPTER VIII.

1817.

The Allen sisters at Pisa, with Caroline Drewe and her family—Sismondi's courtship—Algernon Langton and Marianne Drewe—Sarah Wedgwood and Jessie Allen—Anne Caldwell's marriage 103—112

CHAPTER IX.

1818.

The Josiah Wedgwoods in Paris—The Collos Cousins—William Clifford—Dancing lessons—Madame Catalani—Emma's first letter—Society and housekeeping in Paris—Fanny and Emma at school—A letter from their old nurse . . . 113—122

CHAPTER X.

1819.

Jessie Allen and Sismondi—An outpour to her sister—Bessy's reply—Some account of Sismondi—Their early married life—Posting across France . . . . . . 123—133

CHAPTER XI.

1819—1823.

Emma Allen and her nieces, Fanny and Emma Wedgwood—A gigantic cheese—Races and Race-Balls—Dr Darwin and his daughters—A singing party of girls at the Mount, Shrewsbury—Fanny and Emma at school in London—Sunday-school at Maer—The Sismondis at Geneva . . . . 134—148

CHAPTER XII.

1823—1824.

Bessy's lessening strength—A Wedgwood-Darwin party at Scarborough—Visit to Sydney Smith at Foston Rectory—a memorable debate—An averted duel—Emma confirmed—Revels and flirtations—Kitty Wedgwood's death—Sarah Wedgwood builds on Maer Heath ....... 149—164

CHAPTER XIII.

1825—1826.

Fanny and Emma Allen return to Cresselly—The death of Caroline Wedgwood—The Grand Tour of the Josiah Wedgwoods—Frank Wedgwood at Maer—Their return home in October—Allen Wedgwood Vicar of Maer—The anti-slavery agitation 165—182

CHAPTER XIV.

1826—1827.

The Sismondis in England—Fanny and Emma Wedgwood at Geneva—Bessy and her daughter Charlotte at Ampthill—Life at Geneva—Sarah Wedgwood's generosity—The Prince of Denmark—Edward Drewe's love-affair—Harry Wedgwood on French plays—Fanny and Emma return home—Lady Byron at Geneva ........ 183—205

CHAPTER XV.

1827—1830.

The Mackintoshes at Maer—A bazaar at Newcastle—Bessy on the Drewe-Prévost affair—The house in York Street sold—The John Wedgwoods abroad—Edward Drewe's marriage—The Mackintoshes at Clapham—Bessy's illness at Roehampton—Harriet Surtees at Chêne—Harry Wedgwood's engagement—A gay week at Woodhouse ..... 206—228

CHAPTER XVI.

1830—1831.

Lady Mackintosh's death—Sir James Mackintosh a member of the Board of Control—Hensleigh Wedgwood engaged to Fanny Mackintosh—Elizabeth in London—The second reading of the Reform Bill—A meeting between Wordsworth and Jeffrey—Josiah Wedgwood defeated at Newcastle—Edward and Adèle Drewe—Fear of cholera—Mrs Patterson and Countess Guiccioli 229—241

CHAPTER XVII.

1831—1832.

Charles Darwin's voyage round the world—Hensleigh Wedgwood appointed a Police Magistrate in London—His marriage to Fanny Mackintosh—Fanny Allen and the Irvingites—The cholera—Sir James Mackintosh's death—Charlotte Wedgwood marries Charles Langton—Frank Wedgwood marries Fanny Mosley—Charlotte at Ripley—Fanny Wedgwood's death 242—252

CHAPTER XVIII.

1832—1834.

Josiah Wedgwood elected for Stoke-upon-Trent—Bessy's fall at Roehampton and serious illness—The Langtons at Onibury—Miss Martineau and Mrs Marsh—Hensleigh Wedgwood's scruples as to administering oaths—William Clifford abroad—A tour in Switzerland and visit to Queen Hortense at Constance 253—265

CHAPTER XIX.

1835—1837.

Home life at Maer—Mrs Marsh as novelist—Fanny Allen on Mr Scott—Emma Wedgwood visits Cresselly—Mrs John Wedgwood's sudden death at Shrewsbury—Emma Wedgwood at musical festivals—Charles Darwin returns home—Emma at Edinburgh—C. D. on marriage ...... 266—277

CHAPTER XX.

1837—1838.

The younger Josiah Wedgwood's engagement to his cousin Caroline Darwin—The Sismondis at Pescia—A tour in the Apennines—Mrs Norton at Cresselly—Emma at Shrewsbury and Onibury—Hensleigh resigns his Police Magistracy—A family meeting in Paris—Bro's illness ...... 278—289

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Mrs Charles Darwin, 1839. From a water-colour painting by George Richmond, R.A., in possession of Charles Galton Darwin. Frontispiece

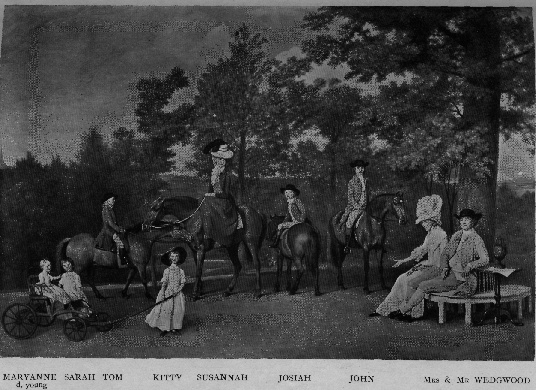

The Wedgwood family at Etruria Hall in or about 1780. From the picture by George Stubbs, R.A., in possession of Cecil Wedgwood of Idlerocks, Staffordshire. Stubbs was the famous animal painter of the time, and was especially noted for his pictures of horses ...... to face p. 8

Thomas Wedgwood. From a chalk drawing belonging to Mrs Vaughan Williams of Leith Hill Place. Artist unknown to face p. 12

Elizabeth (Allen), Wife of Josiah Wedgwood of Maer Hall. From the portrait by Romney in the possession of Mrs Vaughan Williams of Leith Hill Place. Painted when she was about twenty-eight to face p. 22

Fanny Allen, aged 24. From a miniature by Leakey in possession of Mrs Godfrey Wedgwood of Idlerocks, Staffordshire to face p. 36

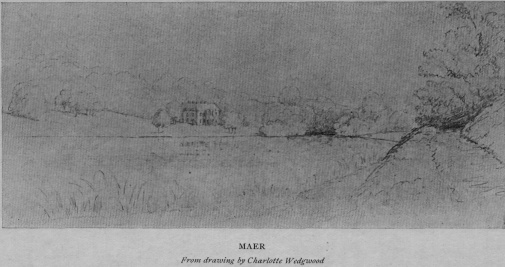

Maer Hall. From a pencil sketch by Charlotte Wedgwood (Mrs C. Langton) in possession of Mrs Godfrey Wedgwood of Idlerocks, Staffordshire ..... to face p. 52

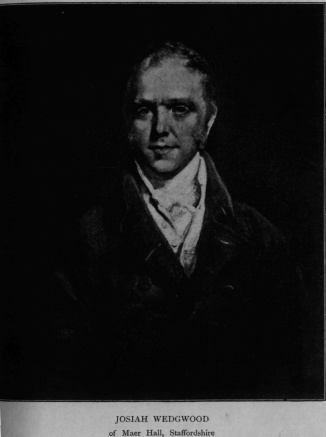

Josiah Wedgwood of Maer Hall. From the portrait by Owen in possession of Mrs Vaughan Williams of Leith Hill Place to face p. 60

Mrs John Wedgwood. From an oil painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence, R.A., in possession of Mrs Clement Allen of Woodchester ........ to face p. 74

J. C. de Sismondi. From a portrait by Madame A. Munier-Romilly given to the Musée Rath at Geneva by Hensleigh Wedgwood to face p. 128

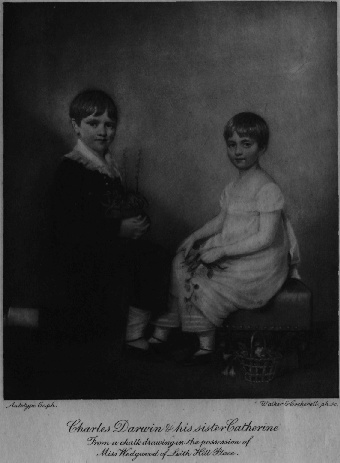

Charles and Catherine Darwin, 1816. From a coloured chalk drawing by Sharples in possession of Mrs Vaughan Williams of Leith Hill Place ........ to face p. 138

Madame de Sismondi, aged 45. From a miniature by Leakey in possession of Mrs R. B. Litchfield. Mrs J. Wedgwood writes of this picture, painted for her: "It is not your merry look when you chuse to make Sismondi stare, but it is your resigned look, when you are entertaining company and are not much entertained yourself" ..... to face p. 144

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ

CHILDREN OF JOHN BARTLETT ALLEN OF CRESSELLY (1733–1803).

1. Elizabeth (Bessy) (1764—1846) m. Josiah Wedgwood of Maer.

2. Catherine (Kitty) (1765—1830) m. Sir James Mackintosh.

3. Caroline (1768—1835) m. Rev. Edward Drewe.

4. John Hensleigh (1769—1843) of Cresselly, m. Gertrude Seymour.

5. Louisa Jane (Jane or Jenny) (1771—1836) m. John Wedgwood.

6. Lancelot Baugh (Baugh) (1774—1845), Master of Dulwich College, m. 2ce.

7. Harriet (sometimes called Sad) (1776—1847) m. Rev. Matthew Surtees, of North Cerney.

8. Jessie (1777—1853) m. J. C. de Sismondi, historian.

9. Octavia, died young.

10. Emma (1780—1866) unmarried.

11. Frances (Fanny) (1781—1875) unmarried.

CHILDREN OF JOHN HENSLEIGH ALLEN OF CRESSELLY (1769–1843).

1. Seymour Phillips (1814—1861) of Cresselly, m. Catherine dan. of Earl of Portsmouth.

2. Henry George (1815—1908).

3. John Hensleigh (1818—1868).

4. Isabella Georgina, m. G. Lort Phillips of Laurenny.

CHILDREN OF SIR JAMES AND LADY MACKINTOSH.

1. Bessy (1799—1823) unmarried.

2. Fanny (1800—1889) m. her cousin Hensleigh Wedgwood.

3. Robert (1806—1864) m. Mary Appleton.

VOL. I. b

CHILDREN OF MRS DREWE.

1. Harriet, Lady Gifford.

2. Marianne, Mrs Algernon Langton.

3. Georgina, Lady Alderson.

4. Edward, m. Adèle Prévost.

CHILDREN OF JOSIAH WEDGWOOD OF ETRURIA (1730–1795).

1. Susannah (1765—1817) m. Dr Robert Waring Darwin. Charles Darwin was their son.

2. John (1766—1844) Banker, m. Jane Allen.

3. Josiah (1769—1843) of Maer, Potter, m. Elizabeth Allen.

4. Thomas (1771—1805).

5. Catherine (Kitty) (1774—1823) unmarried.

6. Sarah Elizabeth (1778—1856) unmarried.

CHILDREN OF JOHN WEDGWOOD (1766–1844).

1. Sarah Elizabeth (Sally, then Eliza) (1795—1857) unmarried.

2. Rev. John Allen (Allen) (1796—1882), Vicar of Maer.

3. Thomas (Tom) (1797—1862) Colonel in the Guards, m. Anne Tyler.

4. Caroline, died young.

5. Jessie (1804—1872) m. her cousin Harry Wedgwood.

6. Robert (1806—1880) m. 2ce.

CHILDREN OF JOSIAH WEDGWOOD OF MAER (1769–1843).

1. Sarah Elizabeth (Elizabeth) (1793—1880) unmarried.

2. Josiah (Joe or Jos) (1795—1880) of Leith Hill Place, m. his cousin Caroline Darwin.

3. Charlotte (1797—1862) m. Rev. Charles Langton.

4. Henry Allen (Harry) (1799—1885) Barrister, m. his cousin Jessie Wedgwood.

5. Francis (1800—1888) Potter, m. Frances Mosley.

6. Hensleigh (1803—1891) Police Magistrate, Philologist, m. his cousin Fanny Mackintosh.

7. Fanny (1806—1832) unmarried.

8. Emma (1808—1896) m. her cousin Charles Darwin

CHILDREN OF DR ROBERT WARING DARWIN (1766–1848) AND HIS WIFE SUSANNAH WEDGWOOD (1765–1817).

1. Marianne (1798—1858) m. Dr Henry Parker.

2. Caroline (1800—1888) m. her cousin Josiah Wedgwood of Leith Hill Place.

3. Susan (1803—1866) unmarried.

4. Erasmus Alvey (1804—1881) unmarried.

5. Charles Robert (1809—1882) m. his cousin Emma Wedgwood.

6. Catherine (1810—1866) m., late in life, Rev. Charles Langton. Charlotte Wedgwood was his 1st wife.

ALLEN PEDIGREE

WEDGWOOD PEDIGREE

DARWIN PEDIGREE

A CENTURY OF FAMILY LETTERS

CHAPTER I

1792—1800

Emma Wedgwood—The Allens of Cresselly—Sir James Mackintosh—The Wedgwoods and Darwins—Josiah Wedgwood's marriage—A ball at Ramsgate—Tom Wedgwood's ill-health—The Wedgwoods at Gunville.

EMMA WEDGWOOD was born on May 2, 1808, at Maer Hall in Staffordshire. She was the youngest child of Josiah Wedgwood of Maer, and his wife, Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of John Bartlett Allen, of Cresselly, Pembrokeshire.

The first part of this family record consists of letters collected by Emma Wedgwood's mother, Mrs Josiah Wedgwood of Maer.1 Later on follow the life and letters of Emma Wedgwood, first as a girl and afterwards as the wife of her cousin, Charles Darwin. As these three families of Allens, Wedgwoods, and Darwins will be found constantly recurring through the book, I have found it convenient to begin with a short account of their origin, and especially of those members of the group who most often appear.

The Allens came originally from the north of Ireland, and settled in Pembrokeshire in about 1600. The estate of Cresselly was acquired by the marriage of John Allen with Joan Bartlett. Their son, John Bartlett Allen of Cresselly (1733—1803), married Elizabeth Hensleigh, who died many years before her husband. He fought in the Seven Years" War as an officer in the 1st Foot Guards (now Grenadier Guards). Quite lately his great-grandson found that he was still remembered in the neighbourhood, and was told that "the owd capen was a wonderful man." He had a large

1 To avoid confusion, these letters, thus collected, will be called "The Maer Letters." Their editor is the third daughter of Emma Wedgwood, who married Charles Darwin.

Vol. I. 1

family, eleven of whom lived to grow up. His melancholy disposition and arbitrary temper made the home in his old age an unhappy one.

Sir James Mackintosh, who married Catharine, the second daughter, thus described the life at Cresselly in a letter to Josiah Wedgwood (November 9, 1800): "We left the '2 maidens all forlorn at the House that Jack built" in tolerable good spirits considering the gloomy solitude to which they are condemned. We have heard from good little Emma [Allen] (she really is the best girl in the world), and are happy to hear that the Squire has been pleased to be infinitely more cordial and gracious to his two poor prisoners than he ever was before, so that bating an absolute want of amusement and a perpetual constraint in conversation they may be pretty comfortable. Mme de Maintenon complains of her situation with Louis XIV, 'Quelle triste occupation de ranimer une âme éteinte, et d'amuser un homme qui n'est plus amusable!""

I remember my father's telling how Mr Allen used to thump his fist on the table, and order his daughters to talk when he wished to be entertained after dinner. They were as a fact remarkably good talkers, and Dr Darwin, of Shrewsbury, thought this was partly owing to their drastic training at home. They formed an interesting group of women, handsome, spirited, clever, and deeply devoted to each other.

Elizabeth Allen, the eldest of the family, had both charm and beauty. She was the centre to whom her sisters turned secure of love and sympathy. Her practical wisdom and delicacy of feeling are revealed in the long series of letters of which only a fraction can here be given. But above all she had the charm of a radiant cheerfulness and of a singular sweetness in voice and manner. There is much in her character which reminds me of my mother. In both there was the same delight in giving and the same unfailing consideration for the unprosperous.

Catharine Allen (Kitty as she was always called) was an able woman, agreeable in conversation, and with a fine character in many respects. She was greatly interested in all questions of humanity, and was, I believe, one of the founders of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In 1798 she married James (afterwards Sir James) Mackintosh. She suffered greatly from the debt and difficulty in which he gradually became involved, but her own economy, especially as to her dress, was rigorous, and she

was entirely high-minded in all questions relating to money. Sydney Smith wrote the following appreciation of Mackintosh's character, addressed to Robert Mackintosh, when he was collecting materials for the life of his father:

"Curran, the Master of the Rolls, said to Mr Grattan: 'You would be the greatest man of your age, Grattan, if you would buy a few yards of red tape, and tie up your bills and papers." This was the fault or the misfortune of your excellent father; he never knew the use of red tape, and was utterly unfit for the common business of life. That a guinea represented a quantity of shillings, and that it would barter for a quantity of cloth, he was well aware; but the accurate number of the baser coin, or the just measurement of the manufactured article, to which he was entitled for his gold, he could never learn, and it was impossible to teach him. Hence his life was often an example of the ancient and melancholy struggle of genius with the difficulties of existence. ... A high merit in Sir James Mackintosh was his real and unaffected philanthropy. He did not make the improvement of the great mass of mankind an engine of popularity, or a stepping-stone to power, but he had a genuine love of human happiness. Whatever might assuage the angry passions, and arrange the conflicting interests of nations; whatever could promote peace, increase knowledge, extend commerce, diminish crime, and encourage industry; whatever could exalt human character, and could enlarge human understandings, struck at once at the heart of your father, and roused all his faculties. I have seen him in a moment when this spirit came upon him—like a great ship of war—cut his cable, and spread his enormous canvas, and launch into a wide sea of reasoning eloquence."1

The first Earl Dudley, in his Letters to Ivy, wrote of Mackintosh: "If I were a king I should make an office for him in which it should be his duty to talk to me two or three hours a day. ... He should fill my head with all sorts of knowledge, but, out of the great love I should bear towards my subjects, I would resolve never to take his advice about anything."

My father used to tell us that of all the great talkers he had ever known—Carlyle, Macaulay, Huxley, and others—he held Mackintosh to be the very first.

Caroline Allen married Edward Drewe, a Devonshire parson, brother of the Squire of Grange, near Honiton. Mr Edward Drewe died early, and she was for many years

1 Sydney Smith, by G. W. E. Russell, p. 184.

a widow. Her daughters, Harriet, Lady Gifford, and Georgina, Lady Alderson, mother of the late Marchioness of Salisbury, often appear in the later letters.

Louisa Jane Allen (always called Jane or Jenny) was the beauty of the family. Bessy spoke of her incomparable cheerfulness, and said: "With her the sun always shines, and she seems to trip rather than slide down the hill of life." My mother told us that the warmth and graciousness of her aunt Jane's welcome was quite unique in its charm. She married John, the eldest son of Josiah Wedgwood of Etruria, who soon after his father's death became a partner in Davison and Co.'s bank in Pall Mall. The Bank failed in 1816, and after that time he had no profession. He should be remembered as the founder of the Horticultural Society. "On the 7th March, 1804, there met at his suggestion in Hatchard's shop a little gathering, of whom the most distinguished was Sir Joseph Banks, and from their discussion sprang a society incorporated in 1809, Lord Dartmouth being the first President."1

Harriet Allen, the fifth daughter, was "very pretty and very tiny,"2 and was of a gentle unassuming nature. Her marriage to Matthew Surtees, Rector of North Cerney in Wiltshire, was most unhappy. It was made, as her sister Jessie said, with "an almost culpable want of affection," and only in order to escape from the unhappiness of her home. The family greatly disliked Mr Surtees, and he appears to have been jealous, ill-tempered, and tyrannical.

Jessie Allen, who married Sismondi the historian, was, with the exception of Bessy, the most beloved by all her sisters. She was the favourite of her nephews and nieces, and had an especial love for Emma Wedgwood, the subject of this book. Jessie must have been a delightful companion, full of vivacity and gaiety, and with the power of intense devotion to those she loved. She was handsome, with brilliant colouring, large grey eyes, and dark hair. Her sister Bessy's letters to her "dearest of the dear," as she calls her, show a peculiar warmth. In one she wrote: "My silence has nothing to do with forgetfulness. Those who love you, my Jess, are not liable to that accident."

Octavia Allen died at the age of twenty-one, and only appears once or twice in the earlier letters.

The two youngest sisters, Emma and Fanny Allen, who

1 Life of Josiah Wedgwood, by F. Julia Wedgwood.

2 Mrs Smith of Baltiboys, in the Memoirs of a Highland Lady, thus characterises her.

never married, were important members of the group. Emma Allen was the only plain woman among the sisters. She spoke of her "half-formed face," and was quite aware how much more Jessie and the piquant Fanny were sought after. But she had no doubt of her welcome at Maer. She wrote in 1803 to her sister Bessy (sixteen years older than herself): "I have a very earnest desire to have some other communication than letter writing with my dear Bessy, whom it is now four years since I have seen. I do long to see you very much, and your children, and I am determined to pay you a visit soon after Christmas or at least before I return home to Cresselly. It has always been a subject of regret to me to have spent so little of my life with you, whom I so dearly love and admire more than anybody in the world."

Fanny Allen was more like a sister than an aunt to her elder nieces. She was very pretty, vivacious, and clever, with some sharpness in her marked character and great charm—a pet of Sir James Mackintosh, and a fierce Whig and devoted admirer of Napoleon. I remember her in her old age as a delightful companion, full of life, and still as straight as a dart.

Of the two brothers it is not necessary to say much, as there are no letters to or from them in the Maer collection. John Hensleigh Allen became the Squire of Cresselly after his father's death. He had a sunny, happy disposition, and was, like his own son Harry, a good raconteur. Lancelot Baugh, called Baugh, was Master of Dulwich College, where his sisters often visited him.

The first record of the Wedgwoods is in 1299, as villeins of Lord Audley in the Manor of Tunstall. Afterwards they were yeomen farmers at Blackwood-in-Horton. Before 1500 they became the Squires of Harracles.1 The ancestors of the Wedgwoods of Etruria separated from the senior branch1 about 1600, and became absorbed in the business of potting. Josiah Wedgwood (1730—1795) founded the town of Etruria in Staffordshire, where he carried on his renowned pottery works. His daughter, Susannah, married Dr Robert Waring Darwin of Shrewsbury, and was the mother of Charles Darwin.

The Darwins came originally from Lincolnshire, William

1 The Wedgwoods of Harracles possessed some portion of these estates until the middle or end of the eighteenth century, when they became extinct.

Darwin of Marton, who died ante 1542, being the first known Darwin. They were yeomen in Lincolnshire for about 100 years, and then rose in rank. William Darwin (b. 1620) served as Captain Lieutenant in Sir W. Pelham's troop of horse, and fought for the King. His son William Darwin (b. 1655) married Anne Waring, the heiress of the Manor of Elston, Notts, which property is still in the possession of the elder branch of the Darwin family. His grandson was the well-known physician and poet, Dr. Erasmus Darwin of Lichfield, father of Dr. Robert Waring Darwin and grandfather of Charles Darwin.

The first intimation of intercourse between the Wedgwoods and Allens is the following letter from Josiah Wedgwood, the second son of Josiah Wedgwood of Etruria:

Josiah Wedgwood the younger to his father.

DEAR SIR, TENBY, August 20, 1792.

You will have heard by a letter of mine to Tom that we have had a very gay week at Haverfordwest Assizes. I have not been at Cresselly since, but as I left them all very well I hope to find them so to-morrow. The family at Cresselly is altogether the most charming one I have ever been introduced to, and their society makes no small addition to the pleasure I have received from this excursion. I am very happy to perceive that their spirits are not much affected by their Father's marriage.1 Our pleasures here are very simple, riding, walking, bathing, with a little dance twice a week.

You are so kind as to say that you shall be glad to see me and my sister, but I hope you have no objection to me staying a while longer, as much on my sister's account as my own, for I am afraid she has little chance of bringing Miss Allen back with her.

I am,

Your affectionate and dutiful son,

JOSIAH WEDGWOOD.

1 His marriage to the daughter of a coal-miner. She was not brought to Cresselly.

Whether Josiah and his sister succeeded in persuading Miss Allen to return with them to Staffordshire is not known. But his wooing was successful, for his marriage took place in December, 1792, when he was twenty-three, and she was twenty-eight years old. Josiah, the younger, was always called Jos, and by this name he will be known here. There are but few letters from him in the Maer collection, and he had not the Allen gift of expression. His character must be realised not from what he says himself, but from the impression he made on others.

Fanny Allen said: "Daddy Jos is always right, always just, and always generous," and Dr Darwin considered him one of the wisest men he had ever known. He inspired awe as well as respect. His wife, although deeply devoted to him, was not quite at ease with him, and a little afraid of annoying and vexing him.1 But this was not judging him quite fairly, for though he was silent and grave, he had no harshness of temper. I have a dim impression of being told that Bessy considered men as dangerous creatures who must be humoured. Probably her early life at Cresselly had shaken her nerves and left her with impressions that she never got over. A little speech of Sydney Smith's, quoted to me by my mother, is interesting: "Wedgwood's an excellent man—it is a pity he hates his friends." His nieces the Darwins were, as girls, afraid of him, and I have been told that they were astounded at their brother Charles talking to him freely as if he was a common mortal, and that this trust on Charles" part made his uncle fond of him. My father says of him in his Autobiography: "He was silent and reserved, so as to be a rather awful man; but he sometimes talked openly with me. He was the very type of an upright man, with the clearest judgment. I do not believe that any power on earth could have made him swerve an inch from what he considered the right course."

During the first few years of their married life Jos and Bessy lived at Little Etruria, a house near Etruria Hall, which had been built for Bentley, his father's partner. Etruria was then quite a rural spot. To those who know what it is now with collieries, iron-works, and pottery kilns belching out black smoke, with dying trees in the fields, and blackened workmen's cottages, it is strange to read Emma Allen's description written about 1800: "I spent Saturday morning

1 He must have been very indulgent to his wife's wishes, for I have been told that no cows were kept at Maer, as the moaning of the cows when their calves were taken away distressed her.

in walking with John [Wedgwood] over the works, which gratified me very much. I think Etruria [Hall] altogether a very nice place, much too good for its present inhabitants, and I felt interested in everything I saw there. I imagined it occupied by you and all the Wedgwoods, and how comfortable it must then have been. The green gate leading from one house to the other, which I had heard so much of from those I loved, immediately caught my attention."

After his father's death in 1795 Jos and Bessy were more or less wanderers for some years. They lived first at Stoke d'Abernon, in Surrey, and from 1800—1805 at Gunville, in Dorsetshire. He appeared to have trusted the management of the potteries almost entirely to his partner and cousin Mr Byerley, only himself paying occasional visits to Etruria.

There are but few letters to give in these old days—none of any interest till 1798. In that year Kitty and Harriet Allen had both married. Caroline and Jenny Allen had been married for some years, so that there were four sisters now left at Cresselly—Jessie, Octavia, Emma, and Fanny.

The following letter describes a meeting of Bessy and her two sisters, Jessie and Octavia, with the Mackintoshes at Broadstairs. It must have been the first time she had seen Kitty since her marriage to Mackintosh in April of the same year. Bessy was taking care of Octavia, who was threatened with consumption.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her sister Emma Allen.

BROADSTAIRS, 17th Oct. [1798].

...We found Kitty very well and in good spirits as usual. She visits hardly anybody here, which is very prudent. Mr M. still continues the fondest and the best-humoured husband I ever saw. The children1 are very manageable and the least troublesome of any I ever saw, and what will give you pleasure, I think she makes a very kind and attentive stepmother. Jessie and I have a snug little lodging twenty yards from theirs; we board with Kitty, and Ocky sleeps in the house with her to avoid the inconvenience of going out of nights. This is our present estab-

1 His three daughters, Maitland, Mary, and Catherine, by his first wife Catherine Stuart.

lishment, which we find very comfortable.... We have been at two balls, one at Margate, the other at Ramsgate, the last was a very genteel one, where we saw a multitude of pretty women, the first was infinitely vulgar. At Margate, Ocky danced with an Officer who looked very like her friend Capt. Scourfield at a distance, but fell very short when he came near, having but one eye. Some relations of Mr Mackintosh's introduced us all to partners, such as they were, but it must be confessed they were but very so-so. When we went to Ramsgate, the Master of the Ceremonies asked us all to dance, but Jessie and I were too delicate or too proud to like to commission him to solicit the hand of anybody, and chose to sit still. Kitty and Ocky's love of dancing was stronger than their delicate feelings on this subject, and he brought up a couple of partners to them. Ocky's was tolerably genteel, but Kitty's not quite so much so, being rather more upon the establishment of a boy than suits her taste. Ocky's partner, however, had like to have paid dear for the pleasure of dancing with her, for when we came to tea, she undertook to make it, and the urn being what we call very tripless,1 she pulled it over and scalded her poor beau's leg; however, I don't believe he was very hurt, as he danced two or three dances afterwards, and Ocky recovered of her fright enough to dance another set with him. We came away in very good time, and I don't think she is at all the worse for it this morning. There is to be a very grand Ball at Guildford on account of Nelson's victory, the 25th [Oct.], and we are all going.2 ...

Jessie Allen appears to have spent a whole year away from Cresselly, passing many months with the Josiah Wedgwoods. On her return to Cresselly she wrote to her sister Bessy (June 10, 1799): "One thing I do entreat, which is that you take the greatest possible care of your dear self. Get rid if you can of some of the superabundant affection and feeling you have for your own family. At

1 "Tripless," according to the English Dialect Dictionary, is a Pembrokeshire word, and means unsteady, rickety.

2 When they return, that is, to Stoke d'Abernon. The Battle of the Nile was on August 1st this year.

present I am sure you have too much either for your own health or happiness; this is most disinterested advice on my part, for what on earth do I love more or prize higher than your affection for us?" She gave a graphic picture of her nervous dread at returning to Cresselly and her happiness that her younger sister Emma had not to return with her: "Now she is safe, and I am where I ought to have been long ago. I cannot tell you how much I dreaded my first arrival here, and my nervousness got to such a height as almost amounted to misery."

The following is an undated draft of a letter from Bessy to her youngest sister Fanny, seventeen years her junior. It must certainly have been written whilst Fanny was quite a girl, probably about 1800. Nothing is known as to what called for Bessy's reproof.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her sister Fanny Allen.

ETRURIA, Saturday.

MY DEAR FANNY,

It is not with very pleasant feelings that I consider that there is but one day between this and the end of your visit, and as I fear I shall not have an opportunity or feel it in my power to say all I wish when we part, I chuse this way of conveying to you my tenderest wishes for your happiness. I cannot forbear telling you how amiable your conduct has appeared to me ever since our conversation in the Garden. Your silence left me rather in doubt whether you did not either think me unjust, or feel angry with me for what might appear impertinent. I saw I had given you great pain, and I felt very sorry for it. But your kind and obliging manner to me ever since has completely done away every apprehension of that sort, and I see and appreciate as it deserves the delicacy of your conduct. Not only have I never observed in a single instance what I had mentioned to you, but you have taken care by the most affectionate and attentive behaviour to let me see that you were not angry. Continue, my dear Fanny, to watch over your own character, with a sincere desire of perfecting it as much as is in your power, and you will make the happiness of all belonging to you. You have very little to do, for God has

given you an excellent temper, and a very good understanding. Do not therefore content yourself with a mediocrity of goodness. You are now at a happy time of life when almost everything is in your own power, and your character may be said to be in your own hands, to make or mar it for ever. If you humbly look into yourself, you are a better judge of your failings than any other person can be, but do not seek to palliate or veil them from your own heart. Your friends will value you for your excellences.

Josiah Wedgwood of Etruria had a third son, Thomas Wedgwood,1 who has not hitherto been mentioned. He was a remarkable man in many directions—the friend and benefactor of Coleridge, and practically the first discoverer of photography, although he was unable to "fix" his pictures. His short life ended in 1805, when he was thirty-four years old, after years of terrible suffering from some mysterious illness which was never explained.

There is much evidence that his personality was impressive. Fanny Allen tells of "the effect that his appearance and manner had on Mackintosh's 'set," as they were called." "Sydney Smith was almost awed"; and she narrates how at a party assembled to see a picture by Da Vinci of the head of Christ, Dugald Stewart2 said: "You are looking at that head—I cannot keep my eyes from the head of Mr Wedgwood (who was looking intently down at the picture), it is the finest I ever saw." Wordsworth, too, describes his appearance: "His calm and dignified manner, united with his tall person and beautiful face, produced in me an impression of sublimity beyond what I ever experienced from the appearance of any other human being." His brother Jos had a devoted, almost passionate, love for him.

Tom Wedgwood spent a great part of his life wandering in search of health. When at home he chiefly lived with Jos and Bessy, and interested himself much in the education of his little nephews and nieces. His doctrinaire views founded on Rousseau must have been trying to his sister-in-law. In other ways, too, the situation must have needed her tact and unalterable sweetness of character to make the home happy.

1 See Tom Wedgwood, the First Photographer, by R. B. Litchfield.

2 Famous at this time as the leading representative of philosophic studies in England. He held the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh from 1785 to 1820.

The following letter from Jos to Tom was written after the brothers had just parted at Falmouth, whence Tom had sailed for the West Indies. The voyage was undertaken for the sake of his health.

Josiah Wedgwood to his brother Tom.

GUNVILLE, Feb. 28, 1800.

MY DEAR TOM,

I cannot resist the temptation of employing my first moment of leisure to unburden my heart in writing to you. The distance that separates us, the affecting circumstances under which we parted, our former inseparable life and perfect friendship, unite to deepen the emotion with which I think of you, and give an importance and solemnity that is new to my communication with you. I did not know till now how dearly I love you, nor do you know with what deep regret I forebore to accompany you. It was a subject I could not talk to you upon, though I was perpetually desirous to make you acquainted with all my feelings upon it. I would not without necessity leave my wife and children, and I believed that I ought not; yet my resolution was not taken without a mixture of self-reproach. But I repeat the promise I made you at Falmouth.

I have not yet been able to think of you with dry eyes, but a little time will harden me. It is not so necessary for me to see you, as to know that you are well and happy. Nothing could be more disinterested than the love I bear you. I know that my wife and children would alone render me happy, but I see, with the most heartfelt concern, that your admirable qualifications are rendered ineffectual for your happiness, and your fame, by your miserable health. But I have a full conviction that your constitution is strong and elastic, and that your present experiment bids fair to remove the derangement of your machine. I look forward with hope and joy to our meeting again, and I am sure that seeing you again, well and vigorous, will be a moment of the purest happiness I can feel.

Perhaps this may be the last time that I shall write to

you in this strain. If it should for a time revive your sorrow, it cannot long injure your tranquillity, to be told that I love you, esteem you, and admire you truly and deeply.

I took possession of this place this morning with very different feelings from those I should have had if we had been together. I have made up my mind to-day not to add anything to the buildings until I shall have become better acquainted with the place. On looking more closely at the stables I see that 15 or 20 pounds laid out will enable them to serve a year or two, and I shall not be in a hurry to do more.

The last waggon-load from Upcott came about an hour after me, with all the live stock in good condition. I was very well pleased to be saluted by a neigh from the gig-horse the moment she heard my voice—Dido is so like Donna that I thought it was she recovered.—I find the aloes were not quite so good a bargain as we thought, for they were killed by the frost when they were brought.

I shall be here en famille in about 10 days, and possibly my mother and sister with us, but I do not know. In the beginning of April we go to town and there stay to the end of May. Whether we shall then go to Cresselly or Etruria—I do not know.

I have written to Gregory Watt1 to send me a copying machine, that I may send duplicates by another packet, a precaution you must not forget. I will send you more copying paper. I shall curse the French with great sincerity if they take the packet bearing your first letter. How anxiously will it be expected, and with what emotion will it be opened and read! You will hear from us in a month, or less, after your arrival, and we must not expect to hear from you in less than four months from your departure. Very few of the letters I write afford me any pleasure, but I foresee a great pleasure in writing to you all that comes, and just as it comes. There is a pleasure in

1 Son of James Watt, and an intimate friend of the Wedgwood brothers.

tender regret for the absence and misfortunes of a person one loves, and corresponding with that person is the complete fruition of it. I feel like Æneas clasping the shade of Creusa; I call up your image but it is not substantial. Farewell, dear Tom.

The following letters were written after Tom's return from the West Indies, the expedition having proved a complete failure as regarded his health. The Wedgwoods were not yet settled in Gunville, and Bessy was visiting her father and sisters at Cresselly.

Josiah Wedgwood to his wife at Cresselly.

CHRISTCHURCH, July 31, 1800.

I am just returned from a very pleasant evening walk with B. and Jos.1 I find they recollect many things about Etruria that surprised me, particularly in Jos. Our last half-hour was by moonlight on the sea-shore, the waves pouring gently at our feet. The delightful scenery and the innocent prattle of the children have disposed me to write to you, rather than to complete the task I had set myself for this evening of casting up a part of my building accounts. I think it was well imagined of two lovers or friends, separated from each other, to fix the days and hours of writing to each other, that they might be sure that each was occupied about the other at one moment. I hope this invention was of two lovers; if it had been told me of two women, or two men, I should call it romantic affectation. I never in my most philosophical days agreed with the opinion of the proscribers of marriage and upholders of universal concubinage—the expression is as detestable as the idea—and I cannot conceive that any but a corrupt libertine can be sincere in approving it. Who that had felt in himself the tranquil, but penetrating charm of an intimate and long-continued union with a woman sensible to his pains and his

1 Elizabeth and Josiah, the two eldest children, aged seven and five.

pleasures, participating in his hopes, strengthening his good dispositions, and gently discouraging his harshness and petulance, and more than all, who is become flesh of his flesh and bone of his bone, by bearing him children, who that is susceptible of that delightful and ennobling sympathy, would truck it for the wandering gratifications and ferocious contests of brutes. And these men are improvers of the condition of mankind! If one did not know them to be better than they profess to be, one would be afraid to hold converse with them. It is singular that Rousseau, who has given so admirable a picture of domestic education, and infused it with all the powers of his eloquence, should have sent his children to the Enfans trouvés, and that Godwin, whose writings tend to make a foundling hospital of the world, should have been an affectionate husband, and is now a tender father to his wife's and his own child. I am and will be your affectionate husband, and we are and will be tender parents to our dear children. I have no pleasures that I can compare with those I derive from you and from them. Your idea fills me, and I clasp you as the heroes of poetry clasp the shades of the departed.

My sisters went to look at Chettle on Sunday, and were much taken with it.... My mother speaks of you as her dear Bessy. She says she does not know enough of Dorsetshire to be prejudiced for or against it, but she shall be very glad to be near Tom and me and her dear Bessy, and the word with her has a deeper meaning than with some who use it oftener. She is not demonstrative, but she is affectionate. Chettle is to be vacant at Michaelmas. Besides the advantage of my mother and sisters as neighbours, which will be particularly great to Tom, we get the command of a very good manor.

I have just sent up my income return, and I have given in £874 as the tenth of my last year's income. I cannot say but it grudges me to pay such a sum to be squandered, as I believe it will, mischievously.... I have set some additional hands to work at Gunville, and I do not yet despair of Tom and me getting in by the 1st Sept., and

its being ready for you by the time your furlough will expire, to which, by the bye, I hope youwill conform like a good soldier.... Our tête-à-tête1 here is tolerably endurable. We seldom meet for five minutes except at dinner, and then with eating, drinking, and helping the children, we manage to pass an hour with a few remarks. I believe if we were to live twenty years together we should make no further progress in intimacy. However, she does exceedingly well in her situation; she did not come here to amuse me. I do not see any signs of melancholy about her. I fancy my sister's visit has cheered her for a while.

I rely on your discretion to keep my letters to yourself; they may do between you and me, but your quizzing sisters would be tremendous. Give my love to them all, and believe me with heartfelt tenderness, your affectionate husband,

JOSIAH WEDGWOOD.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her husband.

CRESSELLY, Aug. 28th, 1800.

I have felt my heart very heavy with the idea that you would be angry with me for prolonging my stay after my repeated promises that I would not, but I really found it impossible to resist. I am not sure that it would have been right to have done so. If my Father's account of his own situation was accurate it certainly would have been barbarous in me not to have staid, and as he thinks it so, the effect would be much the same on his feelings. But I am sure I am not just to you in doubting for an instant that you will enter into my feelings. I am sure I suffer more in the delay than it is possible you can, because it is more my own doing. I am persuaded your next letter will do away all my present feelings, but the comfort of meeting you will be more than I can express.

Farewell, dear Jos, love to the Children and Miss Dennis.

1 With Miss Dennis, the governess.

Josiah Wedgwood to his wife at Cresselly.

CHRISTCHURCH, August 28, 1800.

... You cannot refuse your father a few days, as he makes a point of your staying longer than the time you had fixed, and I hope Mackintosh and J. Allen will enliven them, so as to make them pleasanter than those you have hitherto passed at Cresselly. I will not affect to say that this difficulty thrown in the way of your return is not disagreeable to me, but you need not apprehend that there is anything of anger in the sentiment. I should be more displeased with your apprehension of anger, if I did not consider that the atmosphere you have lately breathed inspires fear. I am truly sorry that your visit has turned out so little to your satisfaction, and sorry that you will set out low spirited on so long a solitary journey.... I hope you are assured that shooting would not interfere with any plan for meeting you. Shooting is a pleasant thing, and I must have active exercise, but its pleasures are subordinate indeed to those in which the affections are engaged. And it is not on my own account that I am now at all eager about it. You know how much Tom has set his heart and his hopes upon it, and I am certain you have too much kindness for him to grudge the sacrifice of part of my time to this object. I have been sometimes afraid you might think I take from you to give to him, but I have never perceived that you did, and it is a source of sincere gratification to me, and increases my esteem for you, to know that you are without jealousy on the subject, and that you return the sincere affection he bears for you. ...

I am glad you have not executed either of your schemes. Mary Allen1 I have no objection to but as taking up room, which at present we cannot spare. As to the poor little Ridgway, I should have been very sorry if you had put your scheme with respect to her in practice. I do not know that

1 Bessy wished to bring back her cousin, Mary Allen, and "little Ridgway," because she was "half-starved."

VOL. I. 2

she is a fit companion for children. If filled, as I suppose, with the notions common with uneducated Welsh persons, I am sure she is not. She would have been a fish out of water, and you would not have known what to do with her. Above all things preserve the agreeableness of your home....

I wish to heaven I could make you chear up. I owe you a spite for being cast down for nothing. My love to all your party, and I am and ever shall be, your affectionate J. W.

I go to Gunville to-morrow for good.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her husband.

CRESSELLY, Sept. 1st, 1800.

MY DEAR JOS,

Contrary to your calculation, I received your letter of the 28th this evening, and it has made me very happy. I now hasten to write you my last dispatch from Cresselly, but I must make it short, as it is late, and I have taken a long walk which has tired me. I have been a fool to make myself at all uneasy upon the subject, when I knew at the same time that you would not be angry with me, but I don't know how it was, I thought you might feel uncomfortable, and indeed I felt so myself at the thoughts of our meeting being deferred. I have always written to you from the feelings of the moment, and perhaps I have sometimes given you a stronger impression of my being out of spirits than was just. John Allen and Mackintosh have enlivened our society very much, and I think my Father begins to relish society more than he did. I fancied he was a little afraid of Mackintosh at first, but he has now found out that he is by no means overbearing, and he finds himself comfortable in his company.

I am very glad I did not pursue my two schemes with relation to M. Allen and M. Ridgway, and I think you are perfectly right in what you say. I had no notion that our house was in so backward a state when I thought of Harriet [Surtees] paying us a visit, but if I find it inconvenient when we get to Gunville it will be very easy to put them off.

I am very glad you acquit me of all jealousy with respect to dear Tom. I really deserve it, for there are no sacrifices I would not make to be of any service to him, compatible with my other duties. I hope he has joined you by this time, and that he finds he can pursue his game with pleasure and advantage. My kind love to him.

I am, my dearest Jos,

Yours ever,

E. WEDGWOOD.

CHAPTER II

1804—1807

John Hensleigh Allen inherits Cresselly—Departure of the Mackintoshes for India—A press-gang story—Tom Wedgwood's death—Return of the Josiah Wedgwoods to Staffordshire—Sarah Wedgwood and Jessie Allen.

MR ALLEN died in 1803. His son John Hensleigh Allen inherited Cresselly, and after this date lived there with his three unmarried sisters, Jessie, Emma, and Fanny. The following letter from Fanny Allen was written whilst staying in London with the Mackintoshes. Mackintosh had been made Recorder of Bombay, and was knighted before leaving for India.

Fanny Allen to her sister Mrs Josiah Wedgwood.

DOVER STREET, January 11th [1804].

...I am glad to tell you that Kitty's spirits are pretty well recovered since parting with you. The day you left us she was terribly depressed. You know Mackintosh asked Dr Davy,1 the Sydney Smiths and Horner2 to dine

1 Brother of Sir Humphry Davy.

2 Francis Horner (1778—1817), Whig statesman, born at Edinburgh, was one of the group of young men who started the Edinburgh Review. In Parliament he became a great authority on finance, and Lord Cockburn, the Scotch Judge, described him as "possessed of greater public influence than any other private man." His early death at thirty-eight was a great public loss. "I never," said Sydney Smith, "saw anyone who combined together so much talent, worth, and warmth of heart." One of Sydney Smith's letters has a pleasant sentence about him: "Horner is ill. He was desired to read amusing books. Upon searching his library it appeared he had no amusing books. The nearest to any work of that description was the Indian Trader's Complete Guide."

here and, before the evening was over, I think they were of great service to her spirits....

We had a very grand dinner at Erskine's,1 and, what I did not expect, I found it very pleasant. The whole house of Kemble was there (with the exception of John Kemble), Nat Bond, a Mr Morrice Lawrence, Sharp, Boddington, and ourselves. Erskine was not as lively as he was the day he dined here; he was quite absorbed in Mrs Siddons and to my mind much in love with her. She looked uncommonly handsome, but was much too dignified to be pleasant in conversation. I was very much gratified by seeing her and hearing her talk on acting which she did very unaffectedly. I must not forget to tell you she admired my gown exceedingly. She said she thought it one of the prettiest dresses she ever saw.... Mrs Erskine asked Lady Harrington to introduce Kitty, and if she goes she [Lady H.] has promised to do so. Otherwise she has given in her name to the Lady-in-waiting, and I believe has mentioned to the Queen Kitty's desire of being introduced. Miss Stewart has promised us places to see her if she goes. The Nares dined here on Saturday last; Kitty asked the S. Smiths, Charles Warren,2 Horner and Sharp3 to meet them. We had one of the pleasantest and merriest days I have passed for a long time. Mrs Nares looked uncommonly handsome and was in very good spirits, and I hope enjoyed her day very much. Sydney Smith was in his highest spirits, and pleased me particularly by talking

1 Thomas Erskine (1750—1823), the famous advocate, became Lord Chancellor and a peer about two years after this.

2 Charles Warren (1767—1823), line engraver and active member of the Society of Arts. He had a great reputation as an illustrator of books, Gil Blas, Don Quixote, etc.

3 Richard Sharp (1759—1834), commonly called "Conversation Sharp," was a well-known figure in the literary society of the time. He had known Johnson and Burke in his youth, and was intimate with Mackintosh, Rogers, Wordsworth, Canning, and the Holland-House set. Like Campbell the poet, he had been one of Tom Wedgwood's best friends. Mackintosh called him the keenest critic he knew. He had made money as a merchant, and as a London hatter. His country home, at Fredley Farm, near Mickleham in Surrey, was a favourite meeting-place for his friends. Boddington was Sharp's partner in his West Indian business.

of my sisters in the way I wish to hear them talked of, as the very first of women. "I cannot tell you," he told me, "how much I admire and like all your sisters; they have a warmth and friendliness of manner that is delightful, but I think that Mrs Jos Wedgwood surpasses you all."

I think I have given you a very exact account of ourselves since you left us, and answered all your questions with the exception of the one about our friend B., which I really don't know how to answer. I think we are just in the same state as when you left us, not advanced and I don't think gone back, and most probably in the same place we shall ever be. He goes with us I believe to the play on Friday to see Mrs Siddons in Desdemona....

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her sister Fanny Allen.

GUNVILLE, Sunday [15th or 22nd January, 1804].

...I am glad you were too honest a girl to coquet or disqualify about B.,1 and I depend upon your telling me the whole truth and nothing but the truth....

We are going on very harmoniously. Surtees is in high good humour, but so fidgetty that I don't wonder that Harriet is so thin; she looks very well, but I think she is flat. I cannot join Jessie in thinking she is anything like a happy woman. Her spirits are not low, but there is no spring, no liveliness or self-enjoyment at all. I don't know whether she was naturally so grave, or whether it is acquired of late years, but we have had no sort of épanchement de cœur. I have not ventured upon any leading conversation, nor has she led to anything of that sort; and I daresay we shall not. She seems rather pleased at the thoughts of this ball at Blandford, and desires you will not forget to send her clothes off in time. In looking over the account of the birthday the first person that struck my eye was Lady Mackintosh. I take for granted you were in the presence chamber with Miss Stewart, a parcel of shabby plebeians, looking on the honours that had fallen upon

1 It is not known who B. was, nor whether he ever proposed.

the family; and I desire you will give me a more particular account of Kitty's presentation, reception, and appearance. I am, however, more anxious to hear of many other things relating to poor dear Kitty, and which I hope I shall in a day or two either from herself or one of you....

I believe, my little Fanny, I owe a little of your flattering representation of what Sydney Smith said of me to your good nature. You thought it a pity I should not come in for a little of what F. B. used to call "the delicious essence," and so you very kindly sent me a little. However I am much obliged to you for your kind intention in refreshing my memory with the sound of a compliment, which I must confess has still some power to charm, vain mortals as we are....

Fanny Allen to her sister Mrs Josiah Wedgwood.

ALBEMARLE STREET, Saturday [Jan. 28th, 1804].

...Kitty and Mackintosh left town this morning, and have left me one of the heaviest hearts I have ever had. I can scarcely bear to think on their kindness to me at present. The whole week has been uncommonly painful, what with the hurry of packing and the uncertainty and expectation of going every day. It was some comfort for me to see that Kitty's spirits kept up very tolerably to the last. I did not see her this morning, but I hear she was pretty cheerful. Mackintosh was rather low, but I trust they will both feel the quitting England but trifling. I should not be much surprised if they were detained a week at Ryde; in that case Sharp, Horner, and perhaps Sydney Smith, will go down and pass the time with them. That will be very desirable for them, and I cannot but say I should envy them very much—that is to say the visitors. I don't know and I almost fear you have not heard from any of us since Kitty's presentation at Court. Miss Stewart drest her uncommonly well and prettily, and she cut an exceeding good figure; the Queen talked very graciously to her, and she met with very great civility from a great many people on the occasion, particularly from Lady Harrington, who asked her to come

to her evening party on Sunday last. On the whole I was very glad Kitty went to Court. It was something for her to think of, and above all there is nothing like a little vanity to buoy up the spirits.

By the way you did me very great injustice in supposing I added to S. Smith's speech concerning you, for I will not call it a compliment. I never think a compliment worth repeating that I am obliged to add to. As a punishment for your unbelief, I have a great mind not to tell you that, instead of adding, I kept back part of the good things he said of you. Mackintosh, Kitty and I dined with the Smiths on Sunday last, and I have scarcely ever passed a pleasanter or merrier day. The company as usual were Sharp, Rogers, Horner and Boddington. We remained there till twelve, and you will accuse me, I suppose, of gross flattery, if I were to tell you, you were again the subject of a very warm eulogium from more of the gentlemen than Sydney Smith. It was a very humorous dispute and amused me very much. I will not detail it you, because of your unbelief. But Sydney put an end to that part of it which treated of the different degrees of dependence they could place in you and my other sisters in case of any emergency, by declaring he would rely on your kindness to nurse him during a fever, and Jenny's only in a toothache—this was unanswerable and unanswered. They have asked me to spend a few days with them this next week, which I think I shall do. I expect Sydney almost every minute to fix the day. I am happy to have it in my power to cultivate a friendship with them both; I have met with no people in London that I like so much as I do them, or who have showed me more unremitting kindness....

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her husband.

GUNVILLE, Sunday Morning, May 5th [1805].

MY DEAR JOS,

The only thing that has occurred since I wrote last has been the taking of poor Job Harding by the Press-gang,

which has excited a great sensation in the village, and for which I am truly concerned. The night before last they knocked at the door and told the Hardings to get up, as the Press-gang were at Hinton and were coming to take them. Job got up and went down stairs, but they had broke open the door and seized him and carried him off, without giving him time to tie his garters or to put on his coat. The other brother Jem was very ill from a chill, but the Lieut. went up and satisfied himself as to the truth of it, and he had humanity enough to leave him behind, though he said they should come for him very soon. They then went to George Collin's, but he would not open the door or answer when they called, but prepared to stand on the defensive, for which purpose he broke the child's crib to have the stick as a weapon of defence. The crew hearing the crash, thought he had broke through to the next house and made his escape; and so they went off, and he escaped for this time, but I am afraid they will get him and Jem Harding. The poor wife of Job (unlike her namesake in the Bible) is gone off this morning to comfort her husband and to take him some necessaries, and I suppose the pay she received last night, which amounted to 16s., to which Tom added some articles from his wardrobe, and I a guinea; and A. Harding's wife went with her out of friendship (a walk of 40 miles to and from Poole). A good many others of the women went to send her. I saw a letter to-day from him to his wife, written in such a simple honest style, that it interested me very much in his favour. The other two men are frightened to death at the thought of their turn coming next; and they don't lie at home. But what a sad life it is to be feeling the torments of fear, and skulking like a felon, and that for such a length of time as they probably will. Our waggoner coming from Poole yesterday met poor Harding escorted by three men armed, and himself pinioned. I declare this circumstance almost made a Bethlen Gabor1 of me.

1 Bethlen Gabori (1580—1629) was of a noble Protestant family in Hungary, and rose gloriously in defence of the civil rights of the Bohemians. He was introduced by Godwin into his novel St. Leon.

B.1 had a letter from my Joe yesterday. He asks whether Papa does not mean to come and see him before the holidays, as many of the boy's fathers are coming to see their sons. He says the holidays will begin next Wednesday six weeks, and if we fetch him a week before, the five weeks will soon run out; and I wish you would write to Mr Coleridge to mention the matter of his coming home a week before they break up, and then I can tell my Joe of it, which will make him very happy. I had nearly resolved upon setting off to see him to-morrow, but I have thought better of it. The journey so long, the time of being with him so short, and the pain of parting considered, I think it will be as well not to think of seeing him before the holidays.

Tom Wedgwood died at Eastbury, near Gunville, where he lived with his mother, on 10th July, 1805, after much suffering.

Bessy wrote to her sisters (July, 1805): "Indeed the more I think of him the more his character rises in my opinion; he really was too good for this world. Such a crowd of feelings and remembrances fill my mind while I am recalling all his past kindnesses to me and mine, and to all his acquaintances, that I feel myself quite unfit to make his panegyric, but I trust my children will ever remember him with veneration as an honour to the family to which he belonged....