EMMA DARWIN

A CENTURY OF FAMILY LETTERS

EMMA DARWIN

A CENTURY OF

FAMILY LETTERS

1792-1896

EDITED BY HER DAUGHTER

HENRIETTA LITCHFIELD

IN TWO VOLUMES

ILLUSTRATED

VOL. II

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1915

Serene will be our days and bright,

And happy will our nature be,

When love is an unerring light,

And joy its own security.

And they a blissful course may hold

Even now, who, not unwisely bold,

Live in the spirit of this creed;

Yet seek thy firm support, according to their need.

WORDSWORTH: Ode to Duty.

[All rights reserved]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME II

CHAPTER I.

1838-1839.

The engagement of Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood—Dr Darwin's delight—Suburbs versus London—A letter from Sismondi—House-hunting . . . . . . 1—25

CHAPTER II.

1839.

The wedding at Maer—Caroline's baby dies—Life at Gower Street—Hensleigh becomes Registrar of Cabs—Elizabeth gives up the Sunday-school—Charles and Emma's first visit to Maer—Their child born Dec. 27, 1839—My mother's character 26—49

CHAPTER III.

1840—1842.

Charles Darwin in bad health—The Sismondis at Gower Street and Tenby—Miss Edgeworth and Emma Darwin—Anne Elizabeth Darwin, born—Erasmus and Miss Martinean—Charles and Doddy at Shrewsbury—Sismondi's fatal illness—The birth of Edmund Langton . . . . . . 50—63

CHAPTER IV.

1842.

A Revolution at Geneva—Taking children to the pantomime—Charles Darwin meets Humboldt—He visits Shrewsbury—Elizabeth with Emma at Gower Street—Emma at Maer—Sismondi dies June 25, 1842—Jessie comes to live at Tenby 64—74

CHAPTER V.

DOWN.

Down—The dangerous illness of Josiah Wedgwood—The birth and death of Emma's third child—A visit from Hensleigh Wedgwood's children—They get lost in the Big Woods . 75—81

CHAPTER VI.

1843—1845.

The death of John Allen—Emma and Fanny Allen leave Cresselly—Josiah Wedgwood's death—Our nurse Brodie—Henrietta Darwin born Sept. 25, 1843—Charles at Shrewsbury—Madame Sismondi at Chêne—A visit to Combe Florey—Emma at Maer—Mazzini and Carlyle—George Darwin born July 9th, 1845—Improvements at Down . . . . . . 82—97

CHAPTER VII.

1846.

The death of Bessy on March 31st, 1846—Elizabeth leaves Maer—Emma Darwin and two of her children at Tenby . 98—104

CHAPTER VIII.

1847—1848.

Elizabeth Darwin born—Sarah Wedgwood settles at Down—Elizabeth Wedgwood and the Langtons leave Staffordshire—Hartfield—Fanny Allen on a round of visits—The French Revolution of'48—Charles Darwin at Shrewsbury—Francis Darwin born August 16th, 1848—Dr Darwin's death November 13th, 1848 105—120

CHAPTER IX.

1849—1851.

Life at Down—Malvern water-cure—A tour in Wales—Jessie Sismondi on F. W. Newman—The Allens' youthy age—Heywood Lane—Miss Martineau and Mr Atkinson—A party at the Bunsens . . . . . . 121—131

CHAPTER X.

1851.

Illness and death of Annie at Malvern . . . . 132—140

CHAPTER XI.

1851—1853.

The Great Exhibition of 1851—Jessie Sismondi on Mazzini and the Coup d'État—George Darwin—Erasmus Darwin—Fanny Allen goes to Aix-les-Bains with Elizabeth—Jessie Sismondi's death on March 3rd, 1853—The destruction of Sismondi's and Jessie's journals . . . . . . 141—153

CHAPTER XII.

1853—1859.

Eastbourne and Chobham Camp—Miss Langdon at Hartfield—Sydney Smith's Life—A month in London—Florence Nightingale—A High-church wedding—Sarah Wedgwood's death—Letters to William Darwin—His speech at Cambridge—Moor Park—The Origin of Species—Two letters from my mother to my father on religion . . . . . . 154—175

CHAPTER XIII.

1860—1869.

A long illness—The death of Charlotte Langton in 1862—The illness of my mother and Leonard—A humane trap for animals—Catherine Darwin's marriage to Charles Langton—My father's continual illness—The deaths of Catherine Langton and Susan Darwin in 1866—The Huxley children at Down—George a second Wrangler—A month in London—Elizabeth Wedgwood comes to live at Down—Freshwater—My father's accident out riding—Shrewsbury and Caerdeon . . . . 176—195

CHAPTER XIV.

1870—1871.

The Descent of Man—Polly the Ur-hund—The Franco-German War —On keeping Sunday—Erasmus Darwin—The marriage of Henrietta Darwin—A wedding-gift from the Working Men's College . . . . . . 196—207

CHAPTER XV.

1872—1876.

The Expression of the Emotions—The Working Men's College walking party—Abinger Hall—Dr Andrew Clark—A séance at Queen Anne Street—Francis Darwin's marriage—Leonard Darwin in New Zealand—Vivisection—The death of Fanny Allen—Experiments on Teazles . . . . . . 208—224

CHAPTER XVI.

1876—1880.

Bernard Darwin—Stonehenge—R. B. Litchfield's illness at Lucerne—William Darwin's marriage—My father's Honorary Degree at Cambridge—A round of visits—Anthony Rich—The Darwin pedigree—A month at Coniston—Horace Darwin's marriage—A fur-coat surprise—The Liberal victory . . 225—241

CHAPTER XVII.

1880—1882.

Elizabeth Wedgwood's death—A month at Patterdale—Erasmus Darwin's death—The new tennis-court—A visit to Cambridge—The birth of Erasmus, eldest child of Horace—My father's serious state of health—His death on April 19th, 1882 242—257

CHAPTER XVIII.

1882—1884.

A letter to Anthony Rich and his answer—Leonard Darwin's marriage—The purchase of the Grove at Cambridge—Francis Darwin working at the Life of his father—His marriage to Ellen Wordsworth Crofts—George Darwin's marriage—The Greenhill and Stonyfield . . . . . . 258—269

CHAPTER XIX.

1885—1888.

The unveiling of the statue of Charles Darwin—My mother's dog, Dicky—A visit from her brothers Frank and Hensleigh Wedgwood—Oxlip gathering—Her politics—Playing patience and reading novels—Her grandchildren and daughters-in-law—The publication of my father's Life . . . . 270—280

CHAPTER XX.

1888—1892.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood of Leith Hill Place dies—Frank Wedgwood's death—The Parnell Commission—My mother's ill-health—Her affection for Down—Lord Grey and Princess Lieven—The death of Hensleigh Wedgwood—My illness at Durham—Leonard Darwin stands for Lichfield—The grandchildren at Down . . . . . . 281—299

CHAPTER XXI.

1893—1896.

My mother's ill-health—Miss Cobbe—A great storm—A birthday letter to my mother—Her improved health—Herbert Spencer—R. B. Litchfield's illness at Dover—My mother's last illness and death . . . . . . 300—313

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Charles Darwin, 1881. From a photograph by Elliott and Fry

Frontispiece

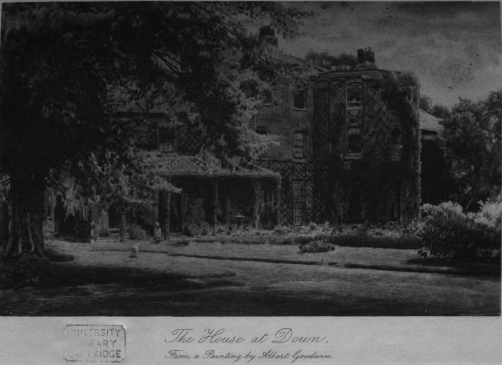

Charles Darwin's house at Down, 1880. From a water-colour painting by Albert Goodwin in possession of Horace Darwin. Mr and Mrs Darwin are seated in the verandah, their grandchild Bernard Darwin stands in front, and "Polly" is trotting towards them,

to face p. 76

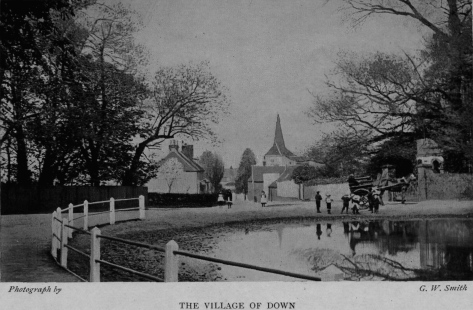

The Village of Down. From a photograph by Mr G. W. Smith

to face p. 104

Erasmus Alvey Darwin. From a photograph by Mr R. Tait

to face p. 146

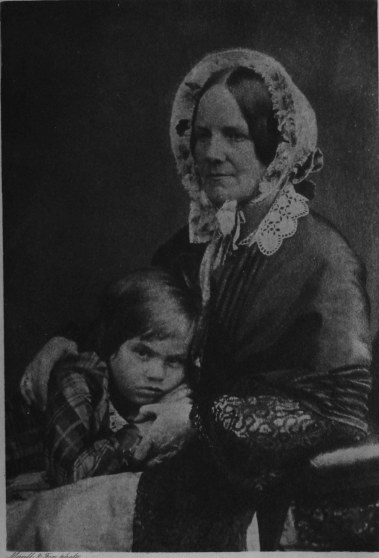

Mrs Charles Darwin and her son Leonard, about 1853. From a photograph by Maull and Fox . . . to face p. 154

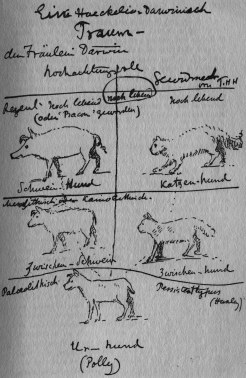

Polly, the Ur-hund. A pen-and-ink sketch by Mr Huxley

to face p. 198

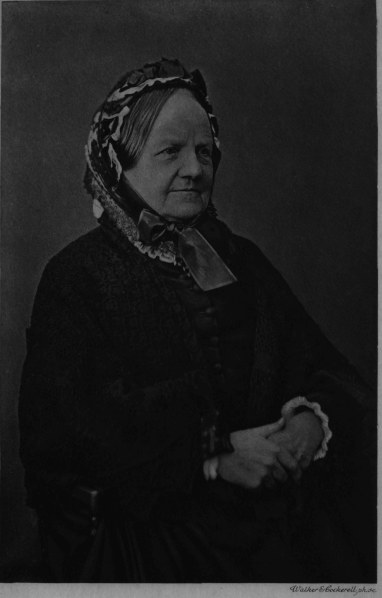

Mrs Charles Darwin, 1881. From a photograph by Barraud

to face p. 246

Mrs Charles Darwin, aged 88. From a photograph by Miss M. J. Shaen, taken in the drawing-room at Down . to face p. 310

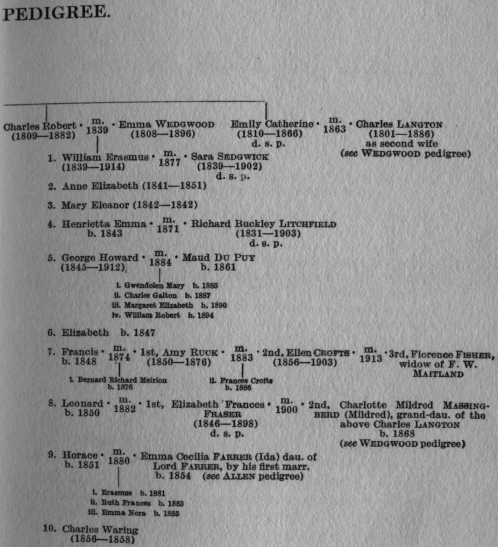

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ

CHILDREN OF JOHN BARTLETT ALLEN OF CRESSELLY

(1733-1803).

1. Elizabeth (Bessy) (1764-1846) m. Josiah Wedgwood of Maer.

2. Catherine (Kitty) (1765-1830) m. Sir James Mackintosh.

3. Caroline (1768-1835) m. Rev. Edward Drewe.

4. John Hensleigh (1769-1843) of Cresselly, m. Gertrude Seymour.

5. Louisa Jane (Jane or Jenny) (1771-1836) m. John Wedgwood.

6. Lancelot Baugh (Baugh) (1774-1845), Master of Dulwich College, m. 2ce.

7. Harriet (sometimes called Sad) (1776-1847) m. Rev. Matthew Surtees, of North Cerney.

8. Jessie (1777-1853) m. J. C. de Sismondi, historian.

9. Octavia, died young.

10. Emma (1780-1866) unmarried.

11. Frances (Fanny) (1781-1875) unmarried.

CHILDREN OF JOHN HENSLEIGH ALLEN OF CRESSELLY

(1769-1843).

1. Seymour Phillips (1814-1861) of Cresselly, m. Catherine dau. of Earl of Portsmouth.

2. Henry George (1815-1908).

3. John Hensleigh (1818-1868).

4. Isabella Georgina, m. G. Lort Phillips of Laurenny.

CHILDREN OF SIR JAMES AND LADY MACKINTOSH.

1. Bessy (1799-1823) unmarried.

2. Fanny (1800-1889) m. her cousin Hensleigh Wedgwood.

3. Robert (1806-1864) m. Mary Appleton.

VOL. II. b

CHILDREN OF MRS DREWE.

1. Harriet, Lady Gifford.

2. Marianne, Mrs Algernon Langton.

3. Georgina, Lady Alderson.

4. Edward, m. Adèle Prévost.

CHILDREN OF JOSIAH WEDGWOOD OF ETRURIA

(1730-1795).

1. Susannah (1765-1817) m. Dr Robert Waring Darwin. Charles Darwin was their son.

2. John (1766-1844) Banker, m. Jane Allen.

3. Josiah (1769-1843) of Maer, Potter, m. Elizabeth Allen.

4. Thomas (1771-1805).

5. Catherine (Kitty) (1774-1823) unmarried.

6. Sarah Elizabeth (1778-1856) unmarried.

CHILDREN OF JOHN WEDGWOOD (1766-1844).

1. Sarah Elizabeth (Sally, then Eliza) (1795-1857) unmarried.

2. Rev. John Allen (Allen) (1796-1882), Vicar of Maer.

3. Thomas (Tom) (1797-1862) Colonel in the Guards, m. Anne Tyler.

4. Caroline, died young.

5. Jessie (1804-1872) m. her cousin Harry Wedgwood.

6. Robert (1806-1880) m. 2ce.

CHILDREN OF JOSIAH WEDGWOOD OF MAER (1769-1843).

1. Sarah Elizabeth (Elizabeth) (1793-1880) unmarried.

2. Josiah (Joe or Jos) (1795-1880) of Leith Hill Place, m. his cousin Caroline Darwin.

3. Charlotte (1797-1862) m. Rev. Charles Langton.

4. Henry Allen (Harry) (1799-1885) Barrister, m. his cousin Jessie Wedgwood.

5. Francis (1800-1888) Potter, m. Frances Mosley.

6. Hensleigh (1803-1891) Police Magistrate, Philologist, m. his cousin Fanny Mackintosh.

7. Fanny (1806-1832) unmarried.

8. Emma (1808-1896) m. her cousin Charles Darwin.

CHILDREN OF DR ROBERT WARING DARWIN (1766-1848)

AND HIS WIFE SUSANNAH WEDGWOOD (1765-1817).

1. Marianne (1798-1858) m. Dr Henry Parker.

2. Caroline (1800-1888) m. her cousin Josiah Wedgwood of Leith Hill Place.

3. Susan (1803-1866) unmarried.

4. Erasmus Alvey (1804-1881) unmarried.

5. Charles Robert (1809-1882) m. his cousin Emma Wedgwood.

6. Catherine (1810-1866) m., late in life, Rev. Charles Langton. Charlotte Wedgwood was his 1st wife.

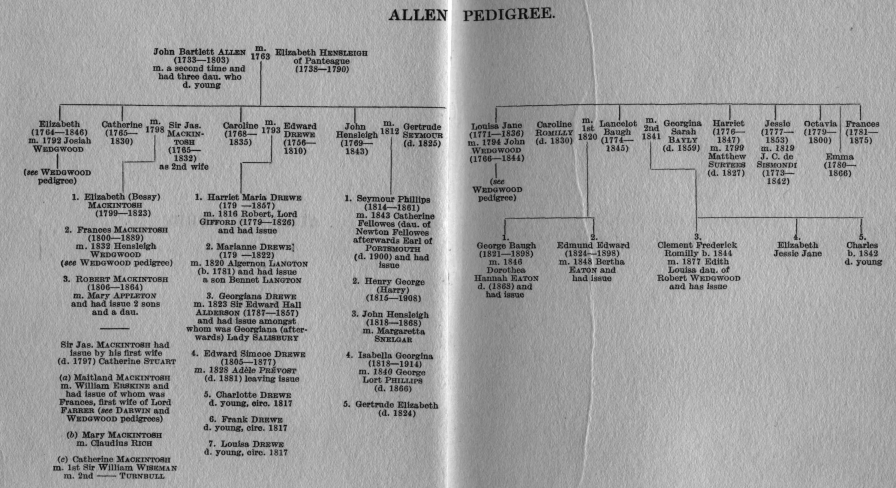

ALLEN PEDIGREE

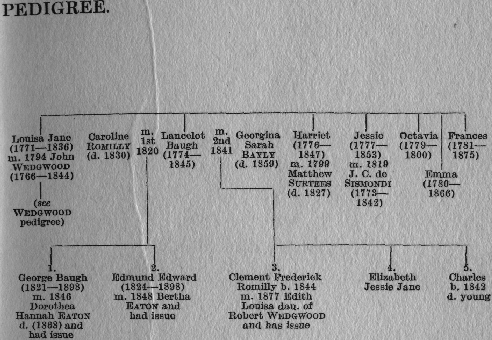

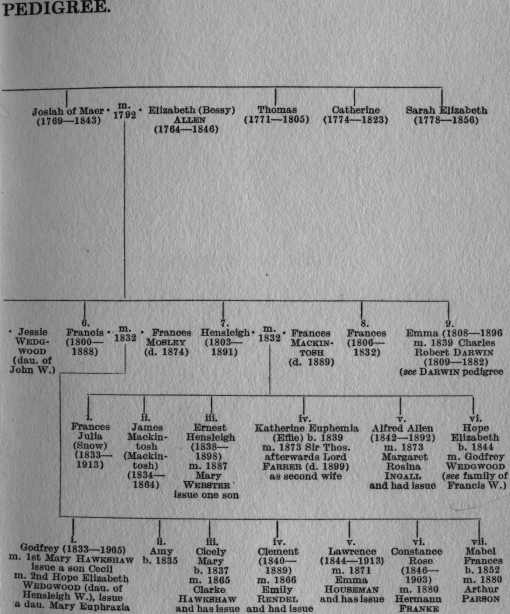

WEDGWOOD PEDIGREE

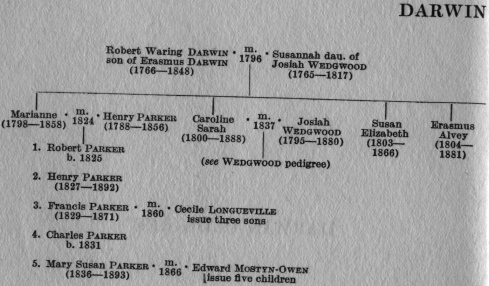

DARWIN PEDIGREE

A CENTURY OF FAMILY LETTERS

CHAPTER 1

1838-1839

Charles and Emma engaged—Dr. Darwin's delight—Suburbs versus London—A letter from Sismondi—House-hunting.

IT seems to have been in the summer of 1838 that my father determined to ask Emma to be his wife. He was however far from hopeful, partly because of his looks, for he had the strange idea that his delightful face, so full of power and sweetness, was repellently plain. He went to Maer on Nov. 8, and on Nov. 11 "The day of days," is written in his diary. The letters which follow show how warmly the engagement was received by friends and relatives alike.

Charles Darwin to Charles Lyell.

SHREWSBURY,

Monday [12 November, 1838].

MY DEAR LYELL,

I suppose you will be in Hart St. to-morrow, the 14th. I write because I cannot avoid wishing to be the first person to tell Mrs Lyell and yourself that I have the very good, and shortly since very unexpected fortune, of going to be married. The lady is my cousin, Miss Emma Wedgwood, the sister of Hensleigh Wedgwood, and of the elder brother who married my sister, so we are connected by manifold ties, besides on my part by the most sincere love and hearty gratitude to her for accepting such a one as myself.

I determined when last at Maer to try my chance, but

VOL. II. 1

I hardly expected such good fortune would turn up for me. I shall be in town in the middle or latter end of the ensuing week. I fear you will say I might very well have left my story untold till we met. But I deeply feel your kindness and friendship towards me, which in truth, I may say, has been one chief source of happiness to me ever since my return to England: so you must excuse me. I am well sure, that Mrs Lyell, who has sympathy for everyone near her, will give me her hearty congratulations.

Believe me my dear Lyell,

Yours most truly obliged,

CHAS. DARWIN.

Dr Darwin to Josiah Wedgwood.

SHREWSBURY, 13 Nov. 1838.

DEAR WEDGWOOD,

Emma having accepted Charles gives me as great happiness as Jos having married Caroline, and I cannot say more.

On that marriage Bessy said she should not have had more pleasure if it had been Victoria, and you may assure her I feel as grateful to her for Emma, as if it had been Martineau herself that Charles had obtained. Pray give my love to Elizabeth, I fear I ought to condole with her, as the loss will be very great.

Ever, dear Wedgwood, your affectionate Brother,

R. W. DARWIN.

Josiah Wedgwood to Dr Darwin.

MAER, 15 Nov., 1838.

MY DEAR DOCTOR,

A good, chearful, and affectionate daughter is the greatest blessing a man can have, after a good wife—if I could have given such a wife to Charles without parting with a daughter there would be no drawback from my entire satisfaction in bestowing Emma upon him. You lately gave up a daughter—it is my turn now. At our time of life our happiness must be in a great measure re-

flected from our families, and I think there are few fathers who have on the whole more cause to be satisfied with the conduct and present circumstances and future prospects of our families. I could have parted with Emma to no one for whom I would so soon and so entirely feel as a father, and I am happy in believing that Charles entertains the kindest feelings for his uncle-father.

I propose to do for Emma what I did for Charlotte and for three of my sons, give a bond for £5,000, and to allow her £400 a year, as long as my income will supply it, which I have no reason for thinking will not be as long as I live.

Give my love to your fireside and believe me,

Affectionately yours,

JOSIAH WEDGWOOD.

MY DEAR UNCLE,

I have begged a bit of Papa's letter to thank you from my heart for the delightful way in which you have received me into your family, and to thank my dear Marianne and Susan for their affectionate notes, which gave me the greatest pleasure. One of the things that gave me most happiness is Charles's thorough affection and value for Papa. I am, my dear uncle, yours affectionately,

EMMA W.

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

SHREWSBURY, Wednesday Morning

[14 Nov. 1838].

MY DEAR EMMA,

Marianne and Susan will have told you what joy and happiness the news gave all here. We have had innumerable cogitations; and the one conclusion I exult in is that there was never anyone so lucky as I have been, or so good as you. Indeed I can assure you, many times since leaving Maer, I have thought how little I expressed how much I owe to you; and as often as I think this, I vow to try to make myself good enough somewhat to deserve you.

I hope you have taken deep thought about the sundry knotty points you will have to decide on. We must have a great deal of talk together when I come back on Saturday. Do have a fire in the Library—it is such a good place to have some quiet talk together. The question of houses, suburbs versus central London—rages violently around each fireplace in this house. Suburbs have rather the advantage at present; and this, of course, rather inclines one to seek out the arguments on the other side. The Governor gives much good advice to live, wherever it may be, the first year prudently and quietly. My chief fear is, that you will find, after living all your life with such large and agreeable parties as Maer only can boast of, our quiet evenings dull. You must bear in mind, as some young lady said, "all men are brutes," and that I take the line of being a solitary brute, so you must listen with much suspicion to all arguments in favour of retired places. I am so selfish, that I feel to have you to myself is having you so much more completely that I am not to be trusted. Like a child that has something it loves beyond measure, I long to dwell on the words my own dear Emma. As I am writing just as things come uppermost in my mind, I beg of you not to read my letters to anyone, for then I can fancy I am sitting by the side of my own dear future wife, and to her own self I do not care what nonsense I talk—so let me have my way, and scribble, without caring whether it be sense or nonsense.…

My father echoes and re-echoes uncle Jos's words, "You have drawn a prize!" Certainly no man could by possibility receive a more cordial welcome than I did from every one at Maer on Monday morning. My life has been very happy and very fortunate, and many of my pleasantest remembrances are mingled up with scenes at Maer, and now it is crowned. My own dear Emma, I kiss the hands with all humbleness and gratitude, which have so filled up for me the cup of happiness—It is my most earnest wish I may make myself worthy of you. Good-bye.

Most affectionately yours,

CHAS. DARWIN.

I would tear this letter up, and write it again, for it is a very silly one, but I can't write a better one.

Since writing the former part the post has brought in your own dear note to Katty. You tell me to be a good boy, and so I must be, but let me earnestly beg of you not to make up your mind in a hurry: you say truly Elizabeth never thinks of herself, but there is another person who never thinks of herself, but now she has to think of two people, and I am, thank Heaven for it, that other person. You must be absolute arbitress, but do, dear Emma, remember life is short, and two months is the sixth part of the year, and that year, the first, from which for my part, things shall hereafter date. Whatever you do will be right, but it will be too good to be unselfish for me until I am part of you —Dearest Emma, good-bye.

Emma Wedgwood to Madame Sismondi.

MAER, Nov 15th. [1838].

MY DEAR AUNT JESSIE,

Nothing is pleasanter than writing good news, and I am sure you will be pleased with what I have to tell you. When you asked me about Charles Darwin, I did not tell you half the good I thought of him for fear you should suspect something, and though I knew how much I liked him, I was not the least sure of his feelings, as he is so affectionate, and so fond of Maer and all of us, and demonstrative in his manners, that I did not think it meant anything, and the week I spent in London on my return from Paris, I felt sure he did not care about me, only that he was very unwell at the time. He came to see us in the month of August, was in very high spirits and I was very happy in his company, and had the feeling that if he saw more of me, he would really like me. He came down again last Thursday with aunt Fanny, and on Sunday he spoke to me, which was quite a surprise, as I thought we might go on in the sort of friendship we were in for years, and very likely nothing come of it after all. I was too much bewildered all day to feel my happiness and there was a

large party in the house, so we did not tell anybody except Papa and Elizabeth and Catherine. Dear Papa, I wish you could have seen his tears of joy, for he has always had a great regard for Charles, and Charles looks up to him with the greatest reverence and affection. I believe we both looked very dismal (as he had a bad headache) for when aunt Fanny and Jessie [Wedgwood] went to bed they were wondering what was the matter and almost thought something quite the reverse had happened. Fanny Hensleigh was 'cuter, and knew quite well what had happened. I went into their rooms at night, and we had a large party talking it over till very late, when I was seized with hunger, and Hensleigh went down to forage in the kitchen and found a loaf and 2 lb. butter and a carving knife, which made us an elegant refection. Catherine was delighted, indeed I was so glad to find that all of them had been wishing for it and settling it. It is a match that every soul has been making for us, so we could not have helped it if we had not liked it ourselves. He and Catherine went off to Shrewsbury on Monday, so that I had not much to do with him, but we had time for some satisfactory little talks which made us feel at ease.

I must now tell you what I think of him, first premising that Eliz. thinks pretty nearly the same, as my opinion may not go for much with you. He is the most open, transparent man I ever saw, and every word expresses his real thoughts. He is particularly affectionate and very nice to his father and sisters, and perfectly sweet tempered, and possesses some minor qualities that add particularly to one's happiness, such as not being fastidious, and being humane to animals. We shall live in London, where he is fully occupied with being Secretary to the Geological Society and conducting a publication upon the animals of Australia.1 I am so glad he is a busy man. Dear Eliz. rejoices most sweetly with me and forgets herself entirely, as, without meaning a compliment to myself, I am afraid she must miss me very much. I am sure I could not have

1 The Zoology of the Voyage of the "Beagle."

brought myself to rejoice in her marrying. Mamma takes it very comfortably and amuses herself a good deal with planning about houses, trousseaux and wedding-cake, which last we were in hopes she would not have thought of, as it is a useless trouble and expense. I bless the railroad every day of my life, and Charles is so fond of Maer that I am sure he will always be ready to steam down whenever he can, so that we shall always be within reach of home. I think I have egotized nearly enough, but I feel sure that you and my dear uncle will enter entirely into my happiness.

Catherine and Charles's return home made a great sensation, for she had written word that they were not coming till Tuesday. Susan says the Dr looked very much pleased when he heard the cause of their return. Aunt Sarah was delighted; she told Eliz. she had quite given it up in despair. We are going to dine with her to-day, when we shall do a considerable quantity of talking. I don't think it of as much consequence as she does that Charles drinks no wine, but I think it a pleasant thing. The real crook in my lot I have withheld from you, but I must own it to you sooner or later. It is that he has a great dislike to going to the play, so that I am afraid we shall have some domestic dissensions on that head. On the other hand he stands concerts very well. He told me he should have spoken to me in August but was afraid, and I was pleased to find that he was not very sure of his answer this time. It was certainly a very unnecessary fear. Charlotte returned home before he came, which was very vexatious, and I am afraid she is too good a wife to leave her husband again so soon. I have been writing a good many letters so I will wish you good bye, my dearest. Give my tenderest of loves to M. Sismondi. I now rejoice more than ever in having met you at Paris. Your affectionate

EM. W.

I went strait into the Sunday School after the important interview, but found I was turning into an idiot and so came away.

Monsieur Sismondi to Emma Wedgwood.

CHÊNE, 23 Novembre, 1838.

CHÈRE EMMA,

C'est moi qui prens la plume avant ma femme, parceque je veux être le premier à embrasser, au moins, en idée, ma jolie nièce, à la féliciter du bonheur que je vois commencer pour elle, ou si elle est trop fière pour le permettre, à me féliciter du moins moi-même de ce que cette charmante personne, si faite pour le mariage, si faite pour répandre du bonheur autour d'elle, va enfin accomplir sa destinée. Tout ce qu'on peut désirer dans un époux me semble réuni dans celui à qui vous donnez la main, je mets au premier rang de ses qualités le bon goût de vous avoir choisie et d'avoir su vous plaire, mais il a tenu déjà beaucoup de place dans les lettres de toute votre famille quoique aucune ne m'eut préparé à ce qu'il en devint partie, et toutes donnoient l'envie de le connoître et de l'aimer. Cette envie est redoublée à présent que ma gentille nièce fait avec lui la plus grosse de ses alouettes comme elle les appelle; j'espère et je compte que vous lui ferez voir notre Suisse, et que vous nous le ferez voir.

Il a un grand ouvrage à publier, tant mieux; c'est une garantie de bonheur pour la femme autant que pour le mari, qu'une occupation sédentaire, mais il y aura un tems de relâche, et pendant cette intermission du travail, je l'espère, vous viendrez nous voir pendant que nous durons encore.…

Chère Emma, dites à votre père, je vous prie, combien je prens part à sa joie. Nous disons ici que l'amitié a besoin de communications regulières, je les regrette bien vivement avec lui; je voudrois de tems en tems renouveler des sentiments, des pensées, des témoignages et son souvenir, mais au moins il me fait éprouver que votre manière anglaise d'être mort l'un pour l'autre dès qu'on est séparé, n'ébranle point l'amitié, car je sens pour lui la même vivacité d'affection, le même respect pour son caractère, la même joie dans

sa joie, que si je l'avois vu encore hier. Rappelez-moi avec une sincère amitié à tout les vôtres, préparez votre époux à me vouloir un peu de bien, et aimez-moi—adieu.

J. C. L. DE SISMONDI.

Madame Sismondi to her niece Emma Wedgwood.

Sismondi has taken the first place on my sheet of paper because he would not be limited in space, for the expression of his sympathy in your happiness. Dearest Emma, I conceive no greater happiness this side heaven than that you are at this moment enjoying. Everything I have ever heard of C. Darwin I have particularly liked, and have long wished for what has now taken place, that he would woo and win you. I love him all the better that he unites to all his other qualifications that most rare one of knowing how well to chuse a wife, a friend, companion, mother of his children, all of which men in general never think of. I am glad you bring Elizabeth as voucher of the pretty character you have given of him, I might perhaps not have believed all on your word only, but I should have believed you thought so, and have enjoyed with you the exquisite happiness you must necessarily feel in saying, such is my protector, guide, friend, companion for the rest of life, and God grant you a long and happy one together. I hope some of your larks may bring you out to us before your cares and business make you prisoners. I know I shall love him. I knew you would be a Mrs Darwin from your hands.1… Now that your person will belong to another as well as yourself, I beg you not to go to Cranbourne Alley to cloathe it, nor even to the Palais Royal. I do not believe in the economy of it; a substantially good thing is never to be found in such places. I will answer for Jessie's Paris hat, lasting at least two of yours. But be that as it will, if you do pay a little more, be always dressed in good taste; do not despise those little cares

1 Palmistry. Madame Sismondi loved the minor superstitions.

which give everyone more pleasing looks, because you know you have married a man who is above caring for such little things. No man is above caring for them, for they feel the effect imperceptibly to themselves. I have seen it even in my half-blind husband. The taste of men is almost universally good in all that relates to dress decoration and ornament. They are themselves little aware of it, because they are seldom called to judge of it, but let them choose and it is always simple and handsome, so let those be your piédestals. You have given me no intimation when the wedding is to take place, if I had a mind to go to it. Yet that is always the first question put after an information of that sort.

A match here which had set everybody talking, has just been broken off in a way which has set them talking still more, and which I, worldly as I am, find quite sublime. One of our oldest English baronets, with a show place for beauty in England, with £30,000 per ann., fell in love with a daughter of one of our pasteurs, with whom the baronet had been en pension. He had neither father nor mother to consult, but Mons. Eymer, the girl's father, refused his consent for two years, saying his daughter was too young. This autumn Sir J. Thussel, as far as I can make out the name pronounced by a foreigner, returned triumphant to claim his promise and his bride, preceded by a magnificent suite of diamonds and other magnificent gifts. The day was fixed, but Mlle. Eymer, only 17, became more and more sad. At last she told her father, "I have been dazzled by the offer, but I do not love him; I have never known a happy moment since I accepted him. I feel all my happiness remains in my own country and my own family. I therefore retract my promise and will not go with him." Her father represented to her that she must never hope to marry another, that affairs between them had gone too far, she had been too long considered the wife of another for any Genevais ever to think of her, but to do as she pleased. She said she was quite aware of the truth of what he said, but if she never quitted the parental

roof she would not leave it then, and for a man she did not love: so packed up her diamonds and other gifts, and returned them to the baronet with his congé. He is on his road to England, sick of love and disappointment, and she is making a little tour with her mother while the wonder lasts. She tried on her diamonds before returning them, and shewing herself in them to her mother, "Regarde-moibien Maman, car très assurément tu ne me verras jamais plus en diamans." Her decision taken, she was gay with joy, and had hardly once smiled when her greatness hung over her. Now do not judge this after your 3 or 400 pr. ann. or your father's comfortable establishment, but after a Swiss pasteur's daughter, a dowerless girl, one who will probably be obliged to have recourse to some occupation to aid even her simple way of living, and tell me if it is not sublime at 17 to know so well where and how to fix her happiness.

What angelic love is that of sisters! Dear Elizabeth's unselfish rejoicings in your happiness are a proof. That men are the greatest fools that walk the earth is proved in her being still to be asked for. May God bless her, and you all indeed, and give you, my dearest Emma, all the happiness you anticipate and I fervently wish you.

J. S.

Her two earliest friends Georgina and Ellen Tollet wrote as follows. Their friendship in after life included my father, and was only ended by death. I inherited my share and have the happiest memories of these two able and delightful women.

Georgina Tollet to Emma Wedgwood.

[13 or 14 Nov., 1838.]

MY DEAR, DEAR EMMA,

I hope I am as glad as I ought to be at the thing happening that I have been longing for, but you ought to be gratified at my selfish sorrow when I think of losing my earliest friend. It is seldom one thinks two people so enviable as we think you and Charles; we think you as lucky

as you could possibly wish, but we must allow that we have still better reason to know that he is indeed a blessed man. I certainly was surprised at its coming so soon; it was very handsome in him to fancy he doubted. It is very like a marriage of Miss Austen's, can I say more! Those greedy girls Ellen and Carry are crying out to write. You must come any day before Friday in the week. I don't give Catherine Darwin any credit for what you call her good nature. I shall write to her soon and tell her what I think of her luck.

Heaven bless you, Your loving friend,

G. TOLLET.

Ellen Tollet to Emma Wedgwood.

… You two will be quite too happy together, and I hope you will have a chimney that smokes, or something of that sort to prevent your being quite intoxicated. It will be quite enchanting to come and see you, but you will be an untold loss. You are the only single girl of our own age in this country worth caring much for—but life is short and one ought to be cheerful as long as one is neither cold nor hungry, I am both just now.

Charles was, as his letters shew, very eager for the marriage to follow quickly. Emma appears to have felt doubts as to leaving Elizabeth alone, to a life that was one of watching and nursing. Her father was now in broken health and was troubled with a shaking palsy. Her mother had long been a complete invalid.

No letters from my mother to my father have been preserved, either before or after marriage. Whether she destroyed them on his death, or whether he did not keep them, I do not know, but he had not the habit of keeping letters except those of scientific interest. A selection from those he wrote to her during the engagement, all of which she carefully treasured, are here given.

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

[Postmark, 23 Nov., 1838], ATHENÆUM, Tuesday Night.

… I positively can do nothing, and have done nothing this whole week, but think of you and our future life.—You may then well imagine how I enjoy seeing your handwriting. I should have written yesterday but waited for your letter: pray do not talk of my waiting till I have time for writing or inclination to do so.—It is a very high enjoyment to me, as I cannot talk to you, and feel your presence by having your own dear hand within mine. I will now relate my annals: On Saturday I dined with the Lyells, and spent one of the pleasantest evenings I ever did in my life. Lyell grew quite audacious at the thoughts of having a married geological companion, and proposed going to dine at the Athenæum together and leaving our wives at home. Poor man, he would as soon "eat his head" as do such an action, whilst I feel as yet as bold as a lion. We had much geological and economical talk, the latter very profitable. By the way if you will take my advice, you will not think of reading [Lyell's] Elements [of Geology], for depend upon it you will hereafter have plenty of geology. On Sunday evening Erasmus took me to drink tea with the Carlyles; it was my first visit. One must always like Thomas, and I felt particularly well towards him, as Erasmus had told me he had propounded that a certain lady was one of the nicest girls he had ever seen. Jenny [Mrs Carlyle] sent some civil messages to you, but which, from the effects of an hysterical sort of giggle, were not very intelligible. It is high treason, but I cannot think that Jenny is either quite natural or lady-like.…

And now for the great question of houses. Erasmus and myself have taken several very long walks; and the difficulties are really frightful. Houses are very scarce and the landlords are all gone mad, they ask such prices. Erasmus takes it to heart even more than I do, and declares I ought to end all my letters to you "yours incon-

solably." This day I have given up to deep cogitations regarding the future, in as far as houses are concerned. It would take up too much paper to give all the pros and cons: but I feel sure that a central house would be best for both of us, for two or three years. I am tied to London, for rather more than that period; and whilst this is the case, I do not doubt it is wisest to reap all the advantages of London life: more especially as every reason will urge us to pay frequent visits to real country, which the suburbs never afford. After the two or three years are out, we then might decide whether to go on living in the same house, or suburb, supposing I should be tied for a little longer to London, and ultimately to decide, whether the pleasures of retirement and country (gardens, walks, &c.) are preferable to society, &c., &c. It is no use thinking of this question at present. I repeat, I do not doubt your first decision was right: let us make the most of London, whilst we are compelled to be there; the case would be different if we were deciding for life, for then we might wish to possess the advantages both of country and town, though both in a lesser degree, in the suburbs.

After much deliberate talk (especially with the Lyells) I have no doubt that our best plan will be to furnish slowly a house for ourselves—it will be far more economical both in money and time; but not in comfort just at first.—Will you rough it a little at first?

I clearly see we shall be obliged to give at least £120 for our house, if not a little more.… I will steadily go on looking and pondering: I believe I have good reason for the points I have spoken on; but I wish much to hear all suggestions from you.…

Until yesterday I intended to have paid Maer a visit on Thursday week, the day after the Geolog. Soc., but yesterday I heard of the death of the mother of Mr Owen, who was to write the next number of the Government work, which now he will not probably be able to do, and I am put to my wit's end to get some other number ready. How long this will delay me I can hardly yet tell. I hope

most earnestly not long, for I am impatient to see you again. It is most provoking I cannot settle down to work in earnest, just at the very time I most want to do so. There is the appendix of the Journal and half-a-dozen things besides this unlucky number, all waiting my good pleasure—every night I make vows and break them in the morning. I do long to be seated beside you again, in the Library; one can then almost feel in anticipation the happiness to come. I have just read your letter over again for the fifth time. My own dear Emma, I feel as if I had been guilty of some very selfish action in obtaining such a good dear wife with no sacrifice at all on my part.…

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

[30 November, 1838], Friday Evening.

[After many details on house hunting and domestic affairs.]

Powers of sentimentality forgive me for sending such a letter: it surely ought to have been written on foolscap paper, and closed with a wafer. I told you I should write to you as if you really were my own dear, dear wife, and have not I kept my word most stoutly? My excuse must be, I have seen no one for these two days: and what can a man have to say, who works all morning in describing hawks and owls, and then rushes out and walks in a bewildered manner up one street and down another, looking out for the words "To let." I called, however, to-day on the Lyells. I cannot tell you how particularly pleasant and cordial Lyell's manner has been to me: I am sure he will be a steady and sure friend to both of us. He told me he heard from his sister (whom I know) in Scotland this morning, and she says, "So Mr Darwin is going to be married: I suppose he will be buried in the country, and lost to geology." She little knows what a good, strict wife I am going to be married to, who will send me to my lessons and make me better, I trust, in every respect, as

I am sure she will infinitely happier and happier the longer I live to enjoy my good fortune. Lyell and Madame gave me a very long and solemn lecture on the extreme importance, for our future comfort during our whole London lives, of choosing slowly and deliberately our visiting acquaintance: every disagreeable or commonplace acquaintance must separate us from our relations and real friends (that is without we give up our whole lives to visiting), for the evenings we sacrifice might have been spent with them or at the theatre. Lyell said we shall find the truth of his words before we have lived a year in London. How provokingly small the paper is, my own very dear Emma.

Good-night, C. D.

Emma Wedgwood to Monsieur and Madame Sismondi.

MAER, Friday, Dec. 28, 1838.

MY DEAR UNCLE,

I have been a long time without thanking you for your kind, affectionate letter, which gave me the greatest pleasure, but I have been away to London with Fanny and Hensleigh to help Charles to look for a house. I thought we should only have to walk out into the street and take one, but we found it very difficult, and after a fortnight's hard work I came home without having taken any, but I heard yesterday that Charles had succeeded in taking one that we had very much set our hearts upon in Gower Street, so that is very pleasantly settled.

How I should enjoy coming to see you and my dear aunt Jessie; and I have some hopes that we shall accomplish it some day or other, as Charles has the most lively wish to see Switzerland and the Alps, and then I should send him off to geologise at Chamounix by himself, and I should stay with you. But I am afraid it cannot be this year or next either, he is too busy. I quite agree with you in the happiness of having plenty to do. You don't seem at all afraid of making me vain in what you say, but indeed, I don't think you will give me any worse feeling than the

warmest gratitude and affection in return for yours. I am going to write about dress and all sorts of frivolity to aunt Jessie, as I think it will suit her better than you, so I will wish you goodbye, my very dear uncle, and believe me, yours affectionately, EMMA W. Papa wishes to speak for himself.

Thank you, my dear aunt Jessie, for your warm congratulations and sympathy with my happiness. I was very glad to return home last Saturday, as I grudge every day away from home now. Fanny and Hensleigh look so comfortable in their nice little house that I feel quite sorry to think how soon they must give it up. We had a fly every day and used to go into town to look at houses and [buy] my clothes, and I think I have obeyed your orders, for though I have not bought many things, they are all very dear and the milliner's bill would do your heart good to see. I have bought a sort of greenish-grey rich silk for the wedding, which I expect papa to approve of entirely, and a remarkably lovely white chip bonnet trimmed with blonde and flowers. Harriet has given me a very hand-some plaid satin, a dark one, which is very gorgeous, hand-somely made up with black lace; and that and my blue Paris gown, which I have only worn once, and the other blue and white sort of thing will set me up for the present. Jessie and Susan gave Fanny strict orders not to let me be shabby. (And a grand velvet shawl too.) Our gaieties were first going to the play, which Charles actually proposed to do himself but I am afraid it was only a little shewing off. It was the Tempest, and we all thought it very tire-some (I shall like plays I know still, notwithstanding). We also went to a party at Sir Robert Inglis's, who is the kindest of men and shook me by the hand "till our hearts were like to break," and I did not know when we could leave off again.

Another day we dined at the Aldersons and met a family of Sam Hoares. I thought I knew the young ladies' faces very well, and soon discovered that they had come over in the steam-boat with us. They all looked full of happiness

VOL. II. 2

and goodness, as well as a brother of theirs, a young clergy-man. The presence of so much goodness made Georgina feel very good too, for she was in the happiest state of affectation I ever saw.

I admire your little pasteur's daughter extremely, but I think she should have been a little more sorry for the baronet, though he was rich.

Mama is quite well. I must tell you what sort of a house ours is that you may fancy me. A front drawing-room with three windows, and a back one, rather smaller, with a cheerful look-out on a set of little gardens, which will be of great value to us in summer to take a mouthful of fresh air; and that will be our sitting-room for quietness' sake. It is furnished, but rather ugly. Goodbye, my dearest, no more room.

It was evident that in choosing their house they neither of them gave a thought to its looks. That it should be cheap and have the requisite number of rooms and be in a part of London where they wished to live were the sole considerations.

This house, 12, Upper Gower Street (afterwards 110, Gower Street), is now part of Shoolbred's premises. I well remember how my father often laughed over the ugliness of the furniture with which they began life. "Macaw Cottage" he christened the house in allusion to the gaudy colours of the walls and furniture.

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Saturday Afternoon [29 December, 1838].

MY DEAR EMMA,

I am tired with having been all day at business work, but I cannot let a post go by without writing to tell you Gower Street is ours, yellow curtains and all. I have to-day paid some advance money, signed an agreement, and had the key given over to me, and the old woman informed me I was her master henceforth.… I long for the day when we shall enter the house together; how glorious it will be to see you seated by the fire of our own house. Oh,

that it were the 14th instead of the 24th. Good-bye, my own dear Emma.

I find I must wait in town till the latter end of next week, on account of the lease and paying the money, and suspect I must attend the Geolog. Soc. on the 9th, so my plans are hampered. But what does anything signify to the possessor of Macaw Cottage?

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Jan. 1, 1839. !! 12, UPPER GOWER STREET!!

MY DEAR EMMA,

Many thanks for your two most kind, dear, and affectionate letters, which I received this morning. I will finish this letter to-morrow. I sit down just to date and begin it, that I may enjoy the infinite satisfaction of writing to my own dear wife that is to be, the very first evening of my entering our house. After writing to you on Saturday evening I thought much of the happy future, and in consequence did not close my eyes till long past 2 o'clock, awoke at 5 and could not go to sleep—got up and set to work with the good resolution of spending a quiet day—about 11 o'clock found that would never do, so rang for Conington and said, "I am very sorry to spoil your Sunday, but begin packing up I must, as I cannot rest." "Pack up Sir, what for?" said Mr Conington with his eyes open with astonishment, as if it was the first notice he had received of my flitting. So we arranged some of the specimens of Natural History, but did no real packing up. I, however, sorted a multitude of papers. This morning however we began early and in earnest, and I may be allowed to boast, when I say that by half-past three we had two large vans full of goods, well and carefully packed. By six o'clock we had them all safely here. There is nothing left but some few dozen drawers of shells, which must be carried by hand. I was astounded, and so was Erasmus, at the bulk of my luggage, and the porters were even more so at the weight of those containing my Geological Specimens. There never

was so good a house for me, and I devoutly trust you will approve of it equally. The little garden is worth its weight in gold. About 8 o'clock the old lady here cooked me some eggs and bacon (as I had no dinner) and with some tea I felt supremely comfortable. How I wish my own dear lady had been here. My room is so quiet, that the contrast to Marlborough [Street] is as remarkable as it is delightful. It is now near 9, and I will write no more, as I am thoroughly tired in the legs, but wish you a good night, my own good dear Emma, C. D.

Tuesday morning. Once more I must thank you for your letters, which I have just read. I have been busy at work all morning, and have made my own room quite charming, so comfortable. The only difficulty is that I have not things enough!! to put in all the drawers and corners.…

I can neither write nor think about anything but the house, I am in such spirits at our good fortune. Erasmus & Co. used to be always talking of the immense advantage of Chester Square being so near the Park. Would you believe it I find by the compasses we are as near, within 100 yards of Regent's Park as Chester Square is to Green Park. I quite agree with you that this house is far pleasanter than Gordon Square. In two more days I shall be quite settled, and this change from mental [to] bodily work, will I do not doubt rest me, so that I trust to be able to finish my Glenroy Paper and enjoy my country Holiday with a clear conscience.

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Wednesday Evening, ATHENÆUM [2 Jan., 1839].

MY DEAR EMMA,

After a good day's work, here am I sitting very comfortably, and feeling just that degree of lassitude which a man enjoys after a day's shooting terminated by an excellent dinner. All my goods are in their proper places, and one of the front attics (henceforward to be

called the Museum) is quite filled, but holds everything very well. I walked for half-an-hour in the garden to-day and much enjoyed the advantage of so easily getting a mouthful of air. Erasmus's dinner yesterday was a very pleasant one: Carlyle was in high force, and talked away most steadily; to my mind Carlyle is the best worth listening to of any man I know. The Hensleighs were there and were very pleasant also. Such society, I think, is worth all other and more brilliant kinds many times over. I find I cannot by any exertion get up the due amount of admiration for Mrs Carlyle: I do not know whether you find it so, but I am not able to understand half the words she speaks, from her Scotch pronunciation. She certainly is very far from natural; or to use the expression Hensleigh so often quotes, she is not an unconscious person.…

I long for the hour of inducting you into the glory, I dare not say comfort, of Gower Street. I wish I could make the drawing-room look as comfortable as my own studio: but I daresay a fire will temporarily make things better, but the day of some signal reform must come, otherwise our taste in harmonious colours will assuredly be spoilt for the rest of our lives.…

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Sunday Night, 12, UPPER GOWER STREET, [7 Jan., 1839].

MY DEAR EMMA,

I have just returned from my little dinner at the Lyells' in which I did some geology and some scrattle about coal and coal-merchants. You will say it was high time, for when I came in and began to poke the fire, Margaret said, "You must take care, Sir, there is only one lump left for to-night and to-morrow morning.…"

You will say that the house is too good when you hear that I have lost all wish of going beyond the limits of the spacious and beautiful garden. To-day, however, it rained so heavily that I had my walk in the drawing-room. With a little judgment we shall make the room comfortable, I

can see. I have been trying the plan of working for an hour before breakfast, and find it succeeds admirably. I jump up (following Sir W. Scott's rule, for, as he says, once turn on your side and all is over), at 8, and breakfast at 10, so that I get rather more than an hour, and begin again at 11 quite fresh. You see I quote Sir W. Scott. I am reading in the evenings at the Athenæum his life, and am in the sixth volume. I never read anything so interesting as his diary, and yet somehow I do not feel much reverence, or even affection towards him, excepting to be sure, when he is talking about Johnnie, his grandson. I am well off for books, for I have a second in hand there almost more interesting, and that is poor Mungo Park's travels, which I never read before. It is enough to make one angry to think that having escaped once, he would return again: and yet to a man possessing the coolness under danger which Park had, I can fancy nothing so intensely interesting as exploring such a wonderful country: it is a strange mixture our love of excitement and tranquillity.…

I wish the awful day was over. I am not very tranquil when I think of the procession: it is very awesome. By the bye, I am glad to say the 24th is on a Thursday, so we shall not be married on an unlucky day. I have been very extravagant and ordered a great many new clothes. Mr Stewart wanted me to have a blue coat and white trousers, but I vowed I would only put on clothes in which I could travel away decently. I want you very much to come and take charge of the purse strings as I have already bought several things which I do not much want.…

You tell me to mention when I received your last letter: it came on Friday, the day after it was written.—Good night and good-bye, my dearest.

Monday morning. Fanny has just called. She has made enquiries about the cook, whom Sarah recommended, and has decided she is the best, and therefore has agreed to take her at £14. 14. 0. per year with tea and sugar.

The Hensleighs have strongly urged me to send the odious yellow curtains to the dyers at once, and have them stained

very pale drab, slate, or grey colour: Now will you send me word by return of post whether you would like me to do so and choose to trust to my taste and that of the Dyers, or whether you choose to wait till after our marriage.…

The marriage was fixed for January 29th, 1839, at Maer Charles made one hurried visit there in the middle of January, and on his return to Gower Street, wrote:

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Sunday Night, ATHENÆUM [20 Jan., 1839].

… I cannot tell you how much I enjoyed my Maer visit, I felt in anticipation my future tranquil life: how I do hope you may be as happy as I know I shall be: but it frightens me, as often as I think of what a family you have been one of. I was thinking this morning how it came that I, who am fond of talking and am scarcely ever out of spirits, should so entirely rest my notions of happiness on quietness and a good deal of solitude. But I believe the explanation is very simple. It is that during the five years of my voyage (and indeed I may add these two last), which from the active manner in which they have been passed may be said to be the commencement of my real life, the whole of my pleasure was derived from what passed in my mind while admiring views by myself, travelling across the wild deserts or glorious forests, or pacing the deck of the poor little Beagle at night. Excuse this much egotism, I give it you because I think you will humanize me, and soon teach me there is greater happiness than building theories and accumulating facts in silence and solitude. My own dearest Emma, I earnestly pray you may never regret the great, and I will add very good deed, you are to perform on the Tuesday. My own dear future wife, God bless you.

I will not be solemn any more, but will tell you of an addition to our plate-room, which is to astonish all Gower Street. My good old friend Herbert sent me a very nice

little note, with a massive silver weapon, which he called a Forficula (the Latin for an earwig) and which I thought was to catch hold of soles and flounders, but Erasmus tells me, is for asparagus—so that two dishes are settled for our first dinner, namely soup and asparagus.…

The Lyells called on me to-day after church, as Lyell was so full of Geology he was obliged to disgorge; and I dine there on Tuesday for an especial conference. I was quite ashamed of myself to-day, for we talked for half-an-hour unsophisticated Geology, with poor Mrs Lyell sitting by, a monument of patience. I want practice in ill-treating the female sex. I did not observe Lyell had any compunction; I hope to harden my conscience in time; few husbands seem to find it difficult to effect this.

Since my return I have taken several looks, as you will readily believe, into the drawing-room. I suppose my taste in harmonious colours is already deteriorated, for I declare the room begins to look less ugly. I take so much pleasure in the house, I declare I am just like a great overgrown child with a new toy; but then, not like a real child, I long to have a co-partner and possessor.

Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood.

Saturday, SHREWSBURY [26 Jan., 1839].

… The house is in such a bustle, that I do not know what I write. I have got the ring, which is the most important piece of news I have to tell. My two last days in London, when I wanted to have most leisure, were rendered very uncomfortable by a bad headache, which continued two days and two nights, so that I doubted whether it ever meant to go and allow me to be married. The railroad yesterday, however, quite cured me. Before I came to Maer last time, I was eager in my mind for the advantage of going straight home after the awful ceremony. You, however, made me just as determined on the advantages of not going straight home, and now your last letter (for which I return you thanks, for being so good a girl as to

write) has just put me half way between the two plans. This will give you hopes of my being a very docile husband, thus to have become twice an absolute convert to your scheme. I settled the matter by telling the housemaid to have fires lighted on Tuesday, and if we did not come then to have them Wednesday, so that you may decide precisely as you please at any moment you please. I went as near a falsehood as any honest man could do, by pretending to deliberate and saying in a very hesitating voice, "You need not have a fire on Monday," by which anyone would suppose we were to be married on that morning. Whether I took them in I do not know.…

CHAPTER III

1839

The wedding at Maer—Caroline's baby dies—Life at Gower Street—Hensleigh becomes Registrar of Cabs—Elizabeth gives up the Sunday-school—Charles and Emma's first visit to Maer—Their child born Dec. 27, 1839—My mother's character.

CHARLES DARWIN and Emma Wedgwood were married on Tuesday, the 29th January, 1839, at Maer Church. The wedding was perfectly quiet, and they went at once to Upper Gower Street.

Emma Darwin to her mother.

GOWER STREET, Thursday [Jan. 31, 1839].

MY DEAR MAMMA,

It was quite a relief to me to find on coming out of Church on Tuesday that you were still asleep, which spared you and me the pain of parting, though it is only for a short time. So now we have only the pleasure of looking forward to our next meeting. We ate our sandwiches with grateful hearts for all the care that was taken of us, and the bottle of water was the greatest comfort. The house here was blazing with fires and looked very comfortable and we are getting to think the furniture quite tasteful. Yesterday we went in a fly to buy an arm-chair, but it was so slippery and snowy we did not do much. We picked up some novels at the library. To-day I suspect we shall not go out as it is snowing at a great rate. I have been facing the Cook in her own region to-day, and found fault with the boiling of the potatoes, which I thought would make a good beginning and set me up a little. On

Monday or Tuesday we are going to give our first dinner-party to the Hensleighs and Erasmus. I hope the H.'s will sleep here, we shall see them so much more comfortably. I came away full of love and gratitude to all the dear affectionate faces I left behind me. They are too many to particularize. Tell my dear Eliz. I long to hear from her. Nothing can be too minute from dear home. I was very sorry to leave Caroline so uneasy and looking so unwell. I am impatient to hear of her and the baby. I don't know how to express affection enough to my dear, kind Papa, but he will take it upon trust.

Good-bye, my dearest Mamma,

Your affectionate and very happy daughter,

E. D.

Elizabeth Wedgwood to her aunt Fanny Allen.

MAER, Friday, Feb. 1, 1839.

MY DEAR FANNY,

I have no heart to write you an account of the wedding, it has had such a sad sequel. Yesterday Caroline lost her poor baby… She is as miserable as anyone can be, but she exerts herself very much, and I think the best thing to counterbalance her own grief will be her anxiety about Jos. Of course the chief part of his feeling is for her, but he often cannot command himself when he is sitting with her, and is obliged to leave the room. She came into my mother's room to see us two hours after its death, which I took exceedingly kindly of her, and came into the drawing-room this evening to see my mother again and Charles [Langton] whom she had not seen. She does her utmost not to yield, but she is very unwell and I never felt greater pity for anyone in my life. It is quite affecting to see poor dear Jos's face and hear his depressed voice. The Dr [Dr Darwin] came yesterday at 5, and C. had a good deal of comfort in talking over everything with him, the more so, I have no doubt, from the exceeding interest he has always taken in the poor little thing. The funeral is to be to-morrow—Susan and Charlotte, as well as my

father, will attend. They will go to Fenton in the evening and Susan will go there on Monday, which I am as glad of for Jos's sake (who seems to find her the greatest comfort) as for C.'s. It will make him not so unwilling to go as usual to his employment—but what poor Caroline will find to do I cannot think; for the last so many months the thoughts of this precious child and the preparations for it have occupied her in an intense way that I never saw in anyone else. But I will write no more on this sad subject.

We had such a happy and sweet little letter from Emma to-day that neither my father nor mother could read it without tears.… The ceremony was got through very stout-heartedly, and then there was not much more time but for Em. to change her clothes and pack her wedding bonnet and sit a little by the dining-room fire with Charlotte and me before she set off, and I did not much mind anything but just the last. It is no small happiness to have had such a companion of my life for so long; since the time she could speak, I have never had one moment's pain [from] her, and a share of daily pleasure such as few people have it in their power to shed around them. I am more afraid of my father's missing her than my mother. They had not to be sure a great deal of talk together, but her sunny face will leave a vacancy.…

Emma Darwin to her sister Elizabeth Wedgwood.

GOWER STREET, Saturday [2 Feb., 1839].

MY DEAR ELIZABETH,

Your letter was indeed a shock, and one quite unexpected by me, though not so much so for Charles, as Susan had told him how much alarmed she was at the baby's looks. Poor dear Caroline what fortitude she has. To-day they are returning home and a miserable return it will be. I could not believe what was coming when I read your letter.

My dear sweet Elizabeth, how I do thank you for your

love for me. I have been wishing to tell you that though my own selfish happiness filled my thoughts so much, I never forgot what your dear affectionate heart would feel in losing me, and I am afraid there are many little troubles or discomforts that I helped a little to lighten to you. In your case I never could have behaved as you did; and don't think I am complimenting myself, for I am sure you would miss a sister very much, if she only loved you half as well as I do you. The time will fly very quick before our Maer visit.

On Thursday, Charles and I did some shopping, which he professes rather to like, and I bought my morning gown, a sort of clarety-brown satin turque, very unobjectionable. And then we went slopping through the melted snow to Broadwood's, where we tried the pianoforte which had Mr Stevens1 name written in it, and it sounded beautiful as far as we could judge. If you were virtuous perhaps you would write a note to Mr Stevens to say that I like it particularly in every way, and never heard a P. F. I admired more. We hope to have it home to-day. Yesterday we trudged out again, and half-ruined ourselves at the plate shop, and in the evening we actually went to the play, which Charles thinks will look very well in the eyes of the world.…

I am cockered up and spoilt as much as heart can wish and I do think, though you and Char. may keep this to yourself, that there is not so affectionate an individual as the one in question to be found anywhere else. After this candid and impartial opinion I say no more. I am so glad my dear Mama was comfortable all about the wedding. Give her my best love and to Papa and Charlotte. I wish I had Fortunatus's cap to come and curl my hair over that dear old fire with you and Charlotte. I did so enjoy my walks and talks with Charlotte. Good-bye, my dearest.

EM. D.

1 The Rev. Thomas Stevens, founder and first Warden of Bradfield College. He married Caroline Tollet.

The piano mentioned above was her father's present to her. I remember it well in its handsome mahogany case; it kept its beauty of tone longer than any later piano. For the sake of quiet they lived, grand piano and all, in the smallish back room looking on the garden, which smoky though it was, was a great boon to their country souls.

Mrs Josiah Wedgwood to her daughter Emma Darwin.

MAER, February 4 [1839].

A thousand thanks to you, dearest Emma, for your delightful letter which from the cheerful happy tone of it drew tears of pleasure from my old eyes. I am truly thankful to find you so happy, and still more so that you are sensible of it, and I pray heaven that this may only be the beginning of a life full of peace and tranquillity. My affection for Charles is much increased by considering him as the author of all your comfort, and I enjoy the thoughts of your tasty curtains and your arm-chairs, hoping your Piano is by this time added to them. Mr Stevens is now below, strumming away upon our old affair, and I hope the girls have told him that you like the one he has fixed upon for you.…

I have had excellent nights, and have escaped my morning sicknesses for a good many days. These are among my present blessings for which I am very thankful. I can write no more except tender love to Charles and to the Hensleighs and thanks for your letter to Elizabeth. I hope to have another happy letter from you soon. God bless you, my ever dear, you will have no difficulty in believing me your affectionate "Mum,"

E. WEDGWOOD.

Elizabeth Wedgwood to her sister Emma Darwin.

MAER, Monday Night, February 4 [1839].

MY DEAREST EMMA,

I can hardly tell you how your affectionate expressions go to my heart. I have felt them too sacred to read them to anybody but Charlotte, and only part to

her, tho' she is very comfortable and very sympathising. We have just had a long talk over my fire, for this is the only quiet and private time I can find to write to you in. I do not however deserve your compliment, for it was only sometimes that I minded much beforehand the thoughts of losing you. The wedding was a sort of thing always in view to intercept one's attention. I have minded the reality more than I expected, but that will not last and I shall doubly enjoy the piece of your society I shall get, now I shall not have it all. I shall be obliged to practise more decision of character now I have not you to help me to settle everything great and small. I have always felt ashamed of the compliments in the letters to my unselfishness, for what mother ever was not rejoiced at a daughter's making a happy marriage, and people look on it as a thing of course. And so it is, though there are not many daughters or sisters have so many qualities for making those they live with happy. I think indeed Susan runs you hard. She is gone to-day to Fenton, where she will stay all the week at least, and she will be of the greatest comfort to Jos at any rate.

You have had your dinner-party to-day and I dare say Charles looked very proud to have you at the head of his table. I found Mary, the night before last, sitting by my fire crying over a poem she had cut out of the paper, "The Bride's farewell to her Parents," dated the 29th of January too. There really were many pretty thoughts in it.

My father says he should like to have a drawing of you, which I am very glad of. Is Mr Richmond come back? I don't know whether Mr Holmes is better than him or not, I rather think he is tho'.

Emma Darwin to her sister Elizabeth Wedgwood.

GOWER STREET, Tuesday, February 5 [1839].

MY DEAR ELIZABETH,

I can't remember what we did on Saturday, except walking about a good deal and meeting a pianoforte van in

Gower Street, to which Charles shouted to know whether it was coming to No. 12, and learnt to our great satisfaction that it was. Besides its own merits, it makes the room look so much more comfortable, and we expect Hensleigh and Fanny to be struck dumb to-day at our beautiful appearance. I have given Charles a large dose of music every evening.

To-day we feel much excited with the thoughts of our first dinner-party, turkey and "vitings" if you wish to know. The blue wall looks much better now we have a few prints and drawings hung up.…

I long for some news of poor Caroline. Write quite openly, for I shall keep your letters to myself, and only read aloud parts. I hope Charlotte will write to me one of these days. Give my best love to my dear Mamma and Papa. I hope some of you have complimented Allen on the way he did the service.

Good-bye, my dear Eliz.

Emma Darwin to her mother.

GOWER STREET, Thursday [8th Feb., 1839].

MY DEAREST MAMMA,

I cannot tell you how pleased I was to see your dear handwriting and how much I thank you for writing me such a nice long letter. I shall always preserve it with great care. I was very glad to find you have had such comfortable nights. I will now go back to my annals. On Tuesday … Hensleigh came in, quite agitated with happiness at having obtained this registrarship.1 It is such a wonderful piece of good fortune I could hardly believe it; and it is given him in such a gratifying way, without any testimonials or bothering of anybody. I should like to know whether it is all Lord John Russell's doing, or whether Lady Holland has had any hand in it. She has been very civil lately and sent them 2 dozen apples, &c. Hensleigh

1 Registration of cabs, an office of less emolument and importance than the magistracy he had given up.

does not think it will be at all a hard place. He will be employed from 10 till 4, about four days a week. Fanny's maids have been very uneasy at the shortness of our house-maid and are afraid that she is not tall enough to tie my gown. She is about the size of Betty Slaney, so I hope Fanny set their minds at ease on that point. Our dinner went off very well, though Erasmus tells us it was a base imitation of the Marlborough Street dinners, and certainly the likeness was very striking. But when the plum-pudding appeared he knocked under, and confessed himself conquered very humbly. And then Edward is such a perfect Adonis in his best livery that he is quite a sight. Fanny and Hensleigh slept here, and Hensleigh went the next morning to the office. Catherine has very considerately sent us a Shrewsbury paper that we may see ourselves in print, and as she drew us up she has all an author's feelings on the subject. Charles is not quite used to my honours yet, as he took up a letter to me the other day and could not conceive who Mrs C. Darwin could mean. He has set to his work in good earnest now. The Lyells have called and we were rather sorry to miss them. Yesterday we settled to sit up in state till four o'clock, to see all the crowds who should come, but there only came two callers. We then walked in the Regent's Park and were caught in the rain, which agitated us both a good deal for fear of spoiling my best bonnet. It however was none the worse. I am very much pleased that Papa wants a drawing of me. I don't know whether Mr Richmond is come back. I will go and get it done when you have settled who is best.

Charles desires his best love to you. Will you tell Mary, with my love, that I forgot to tell her about Pitman's Lectures, which I wish her to have as a Keepsake from me, and Elizabeth is to get it bound for her.

My mother told me that when they came to London it was considered impossible not to keep a man-servant, though they would have been much happier with only women-servants.

VOL. II. 3

Mrs Hensleigh Wedgwood to Mrs Marsh at Boulogne.

4, CLIFTON TERRACE, NOTTING HILL, February 13th [1839].

… Your New Year's wishes and hopes do indeed seem now like prophetic anticipations, my dear Anne.… I must tell you how surprised we have been at this proof of Ld. John's good sense and discrimination, and we hear from Lady Holland that he mentioned his intentions of offering it as soon as the vacancy was known to him, and since has written a very pretty letter to Hensleigh to that effect. It is only to be £500 a year, so we shall not be extremely rich, and my year's practice in economy will be very useful.…

You will hear from Mr Marsh that Emma is established in her new home; and most comfortable and snug they looked the only day we have as yet broke in on them. Yesterday they dined here for the first time. Emma is looking very pretty and unanxious, and I suppose there are not many two people happier than she and Charles. I want to know and hear what effect she makes in the London world, if the word can be applied to such simplicity and transparency, and [to one] who has so little notion of making an effect. They made their first appearance in the world at Dr Holland's, where they had a very pleasant day, Hibberts, Coltmans, &c. We have been unusually dissipated also of late in the evening party line, and Mr Rogers has been taking us up, I can't think why, inviting us to breakfast and a party, and coming out here to present me with a lovely copy of his poems. We met a little collection of blue ladies, H. Martineau, Mrs Austin,1 Mrs Marcet, &c., which is I believe quite a new line for him. Mrs Austin is much found fault with for being too aristocratic; since she has gone to Mayfair they say she only frequents parties of the highest distinction.…

1 Wife of John Austin, philosophical jurist. She was one of the Taylors of Norwich, translator and author of various works, a beauty, and mother of the beautiful Lady Duff Gordon.

Elizabeth Wedgwood to her sister Emma Darwin.

MAER, Sunday Morning [3, March, 1839].

MY DEAR EMMA,

It is really quite luxurious of a Sunday morning to find myself with nothing to do.1 I am beginning this letter to you purely to say how pleasant it is. I feel so idle I can hardly sit to anything else. How much obliged I am to the beggars for their singular and generous forbearance in not coming near one of a Sunday, for I cannot imagine any other motive but kind consideration for me in that piece of self-denial of theirs, which is clearly so much against their own interest. About five-and-twenty years I have had the unsatisfactory bother of that school, and I hope I have done with it for life. The other school is not likely to be very orderly; but I think the children learn, and I mean to try what some switching of fingers, steadily administered to Tommy and Billy Philips will do. If it does not succeed they must be turned out. The only time I miss you much is in my room at night. I keep on my fire, and have got a table full of books, but it will feel at present that you are gone. Very soon, I hope, it will begin to feel that you are coming. Good-bye, my dear Em. It is the greatest pleasure that can be, your letters.

I well remember my aunt Elizabeth teaching in the little school she set up close to her Sussex home where she moved after her parents' death. There she went regularly every morning for an hour or two. Her delight in giving up the Maer school makes one appreciate more what the effort and self-sacrifice must have been in this later work. The mention of beggars brings up a sad part of her life. She let herself be preyed upon by all kinds of worthless people and impostors, and must have done harm, as well as much good.

1 Elizabeth appears to have given up teaching the Sunday-school this spring.

Charlotte Langton to her sister Emma Darwin.

[ONIBURY, March, 1839].

MY DEAR EMMA,

I think it will be a very good plan for your and Elizth.'s letters to be made to do double duty, and save you both a good deal of repetition; and it will serve my purpose very well too, for I sometimes feel it absolutely necessary to give a sign of life when I have not wherewithal to fill a sheet or half a sheet, and on those occasions it will be a great relief to me to have a letter to hook on to. Elizabeth seems to enjoy her Sundays very much. Her pity is thrown away upon me, our Sunday-School is so short. Religion and virtue is all that I mean to teach, other things being taught at the day school. But as at the end of half-an-hour I find those topics totally exhausted, I am obliged to resort to a little reading, and a great relief it is.…

Fanny Allen to Mrs Marsh at Boulogne.

TENBY, March 5th [1839].

MY DEAR ANNE,

Your letter has been with me, as a companion, for nearly six weeks, watching for a quiet couple of hours that I might tell you what pleasure your warm and affectionate measure of me gives me. I feel myself of greater value from your opinion of me. I believe praise, after the age of vanity, is of great use to character, by raising your own standard, for it must be a natural feeling not to betray the opinion those whom you value greatly have formed of you. Continue to love me, dear Anne, and I will try not to lose an affection so dear to me. Since I wrote last, indeed since you wrote, how much the Wedgwoods have enjoyed and suffered! Poor Caroline's sorrow is I am afraid yet green.…

Elizth. has suffered from the loss of Emma more than she expected I fancy—her joy at Emma's happy prospects, while I was there, kept her from falling back on herself and thinking of her loss, but that time must have come.

Emma is as happy as possible, as she has always been—there never was a person born under a happier star than she, her feelings are the most healthful possible; joy and sorrow are felt by her in their due proportions, nothing robs her of the enjoyment that happy circumstances would naturally give. Her account of her life with Charles Darwin and in her new ménage is very pleasant.…