[page] 101

VII. On the SCELIDOTHERE (Scelidotherium leptocephalum, OWEN).

By Professor OWEN, F.R.S. &c.

Received October 30,—Read December 18, 1856.

THE extinct species of large terrestrial Sloth, indicated by the above name, was first made known by portions of its fossil skeleton discovered by CHARLES DARWIN, Esq., F.R.S., at Punta Alta, Northern Patagonia, which were described by me in the chapters of the Appendix to the 'Natural History of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle,' treating of the "Fossil mammalia*" collected during that voyage.

The subsequent acquisition by the British Museum of the collection of Fossil Mammalia brought from the pleistocene beds, Buenos Ayres, by M. BRAVARD, has given further evidence of the generic distinction of the Scelidothere from the other Gravigrades of the Bruta phyllophaga†, and has supplied important characters of the osseous system, and especially of the skull, which the fragments from the hard consolidated gravel of Punta Alta did not afford. The best portion of the cranium from the latter locality wanted the facial part anterior to the orbit, and the greater part of the upper walls; sufficient, however, remained to indicate the peculiar character of its slender proportions, and hence the name leptocephalum proposed for the species.

The aptness of the epithet 'slender-headed' proves to be greater than could have been surmised from the original fossil; for the entire skull now in the British Museum (Plates VIII. and IX.) exhibits a prolongation of the upper and lower jaws, and a slenderness of the parts produced anterior to the dental series, unique in the leaf-eating section of the Order Bruta, and offering a very interesting approximation to the peculiar proportions of the skull in the Ant-eaters.

The original fossils on which the genus Scelidotherium was founded, indicated, by the persistence of the cranial sutures and the condition of the epiphysial extremities of the long bones, that they had belonged to an individual of immature age: the difference of size between them and the corresponding parts in the British Museum, depends on the latter having belonged to full-grown individuals: the slight difference in the shape of the anterior molars seems, in like manner, to be due to such an amount of change as might take place in the progress of growth of a tooth with a constantly renewable pulp. I find, at least, no good grounds for inferring a specific distinction between the mature, if not old, Scelidothere from Buenos Ayres and the younger specimen from Patagonia.

* 4to, 1838–40.

† See 'Conspectus Familiarum et Generum Brutorum frondes carpentium,' in 'Description of the Skeleton of the Mylodon robustus,' 4to, 1842.

MDCCCLVII. P

[page] 102

The first peculiar character which the entire cranium of the Scelidothere presents is the increase in vertical diameter (if the thin pterygoid plates be excluded), from the occiput (3, 4) to the anterior nostril (15, fig. 2, Plate VIII.): this character appears to be due, mainly, to the depth of the upper jaw required for the lodgement of the molar teeth and their persistent pulps.

The occipital condyles (Plates VIII. and IX. 2), though terminal, are less prominent than in the Mylodon or Megathere : they are relatively wider apart: their inner straight sides converge towards their lower end. The foramen magnum(Plate IX. 0) is wider relatively than in the Megathere: its upper boundary is festooned, a median notch dividing two convex curves of the thin and rather prominent border: just within this border are two pits: on the inner side of each condyle is a depression: the inner sides of the occipital foramen are impressed with the oblique canals leading to the precondyloid foramina, p, p. The plane of the foramen magnum forms, with that of the basioccipital, an angle of 135°.

The occipital region, which was vertical in the young specimen first described, inclines a little forward, as it ascends, in the adult skulls, but to a less degree than in the Megathere: its height from the upper border of the foramen magnum is half its breadth: it is bisected by a strong median vertical ridge, with a small venous foramen at its lower end: an arched semicircular thicker and rougher ridge forms its upper and lateral boundaries: this ridge bifurcates at its lower part on each side, intercepting thereby a narrow longitudinal fissure, corresponding with the wider lateral fossa of the occipital region in the Megathere, but here rather resembling the digastric fissure in ordinary mammals: the fissure is continued into the rough interspace between the mastoid and paroccipital. In each moderately concave division of the occipital region there is a low subvertical lateral ridge, which is nearer the outer boundary than is the corresponding ridge marked e in the skull of the Mylodon, in Plate V. fig. 1, of my "Memoir on the Mylodon," 4to, 1842.

The paroccipital (Plates VIII. and IX. 4) is relatively larger than in the Megathere, the mastoid (8) is relatively smaller: there is no second superoccipital ridge as in the Megathere.

The lateral rough surfaces (Plate IX. r) for the attachment of the recti capitis antici muscles to the basioccipital, are less prominent than in the Megathere: the under surface of both. the basioccipital (1) and basisphenoid (5) is flatter: the lateral basisphenoidal protuberances are low and obtuse, relatively larger than in the Megathere, not angular as in the Mylodon.

The precondyloid canals are relatively smaller than in the Mylodon; their outlets (ib. p), as in that animal, are behind and distinct from the foramen jugulare or foramen lacerum (j), not blended therewith as in the Megathere.

Corresponding with the indication of the smaller size of the tongue thus given by the canal for its muscular nerve, is the less relative size and depth of the stylohyal depression (8′). The carotid canal (c) seems to have begun at the fore-part of the foramen lacerum. The rough bifid under surface of the petrosal (16) divides it from the auditory cavity.

[page] 103

The loose tympanic bone is wanting. The eustachian groove (e) is plainly traceable from the fore-part of the auditory cavity, expanding to behind the base of the pterygoid plate.

The superoccipital extends upon the upper surface of the cranium in an angular form for more than an inch between the parietals. The temporal ridges are separated from each other by an interspace of only 8 lines, at the narrowest part of the intervening space upon the parietals, in the mid-line of which space is a longitudinal furrow.

The sutures between the parietal, the occipital and the temporal bones, remaining in one of the crania of the Scelidothere in the British Museum, show the same small vertical extent of the long squamosal as in the young individual first described * ; and the suture dividing the mastoid and squamosal below from the parietal above forms an irregularly undulating, almost straight line to opposite the end of the zygomatic process, where it descends and defines the subangular anterior boundary of the squamosal. At this point the squamosal appears to touch the frontal, an angular process of which extends backwards to the foramen ovale (Plate VIII. fig. 2 l), dividing the fore-part of the squamosal from the pterygoid; the three bones appear to concur in forming that foramen.

The zygomatic process, commencing by the ridge continued from the temporal one, as it passes from the parietal to the temporal bone, has an antero-posterior extent of attachment of 3 inches 8 lines; the free projecting end does not exceed 1½ inch in length: it is obtuse, with a slight notch below. The interspace between it and the squamosal plate is 1½ inch. The process (Plate VIII. figs. 1 & 2,27) is trihedral, the outer side almost flat, a little concave behind and as much convex in front: the upper surface forms with the narrow squamosal plate a deep and wide channel, which lodged the lower border of the temporal muscle: the under side is the shortest and broadest, and forms the almost flat subtriangular surface (Plate IX. g) for the articulation of the mandible. This surface differs from the more concave one of the Megathere, in the absence of any defensive ridge or prominence for the joint either behind or externally.

The pterygoid plates (Plate IX. 24) articulate with the sides of the basi- (5) and pre- (9) sphenoid, leaving a free interspace along the under surface of those bones an inch wide at its back part and gradually narrowing to the rounder styliform prolongation of the presphenoid (9). The posterior border of the pterygoid slopes very obliquely from above downwards and forwards, and then more gradually rises with an irregularly undulating outline to blend with the palatine ridge (20), continued to the back part of the alveolus of the last molar. The combined palatines and pterygoids form a long and wide concavity, in which the oblique ridges, diverging from the back part of the bony palate, define the acutely angular contour of the posterior palatal margin, and at the same time the lower boundary of the posterior nasal aperture (ib. n); this aperture, by the production of a ridge from the pointed end of the presphenoid, is shaped like a heart on playing-cards; it gradually expands into the capacious pterygopalatine fossa (ib. n, n, 24, 24).

The parietals (Plate VIII. fig. 2, 7) are quadrate bones, 6 inches in fore and aft extent: the posterior boundary of the frontals (ib. 11) is 8 inches from the occipital ridge; the

* Zoology of H.M.S. Beagle, "Fossil Mammalia," p. 73.

P2

[page] 104

antero-median angles of the parietals are produced between the frontals, but to a less extent than the superoccipital in relation to the parietals. The temporal ridges are continued forwards from the parietal on to the frontal bones as far as the low obtuse postorbital process: in this course each temporal ridge makes three curves with two intervening angles, one at the fronto-parietal suture, the second not quite half-way between that suture and the postorbital process. The frontal region of the cranium swells out a little above the zygomatic arch, but this affords no indication of cerebral development; it is anterior to the true cranial cavity, and is due to the development of extensive frontal sinuses. The fore-part of the frontal terminates in an angle, wedged between the nasal and lacrymal bones, above the middle of the orbit: the descending plate forms the back part of the inner wall of the orbit, where it unites with the maxillary, and then joins the palatine and pterygoid, terminating behind at the foramen ovale (ib. l). The foramen rotundum (ib. r) is 2 inches 3 lines in advance, opening upon the suture between the frontal and pterygoid, and continued forwards by a canal containing the suture between the frontal and palatine.

The palatine bones (Plate IX. 20) surround the posterior nasal aperture, and support the ridges (n, n) defining the lower boundary of that aperture: these ridges divide the inner and under surface of the palatines into an intranasal and an infranasal part: both contribute to form the fore-part of the long and wide faucial fossa.

The maxillary bone forms the major part of the narrow, transversely convex, bony palate (Plate IX. 21), the true palatines terminating anteriorly in a point opposite the penultimate molars (ib. iv): the orbital plate of the maxillary (Plate VIII. fig. 2, 21′) ascends to articulate with the nasal (15), frontal (11), and lacrymal (73), and circumscribes the antorbital foramen (a), by an outstanding malar process, which affords a sutural surface behind for articulation with the malar bone (ib. fig. 1, 26): the maxillary then expands into a broad subquadrate facial plate (ib. fig. 2 a, 21), smooth and convex externally; uniting above with the long nasal (15), behind with the anterior half of the lacrymal (73) and with the malar (26), and below and in front with the premaxillary (22). The outer alveolar wall makes a series of prominences corresponding with the three anterior molars: the inner alveolar wall is a thin plate, forming a bony case for the deeply implanted parts of the molars and their matrices; projecting in relief from the inner side of the facial and orbital plates. The length or depth of the first alveolus (Plate IX. 1) is 3 inches 3 lines; that of the second (2) is 3 inches 9 lines; the succeeding ones (3, 4, 5) gradually decrease in depth. A canal is continued from that of the dental nerve above the alveoli, forward and downward to the lower and lateral part of the outer nostril.

The alveoli, five on each side of the upper jaw, are close-set, with oblique apertures, the inner boundary descending lower than the outer one: their aggregate antero-posterior extent measures 4 inches 3 lines in one adult skull, 4 inches 6 lines in a second. The teeth (Plate IX. i–v), when in place, show wider intervals than the sockets; the situation of the thick periosteum and dental capsule being occupied by the infiltrated matrix which, in the fossil under view, binds the tooth in its place: the shape of the socket

[page] 105

nearly corresponds with that of the tooth it contains. The maxillary extends 4½ inches in advance of the first alveolus, in an obtusely pointed form, slightly diverging from its fellow to form the hinder two-thirds of an unusually long prepalatine or incisive fissure (i). The side of the fore-part of the maxillary is deeply notched for a corresponding process of the premaxillary (22′). The upper surface of the palatine plate is longitudinally grooved, and the inner border of the groove unites with its fellow to form a median ridge.

The premaxillaries (22) have partially coalesced anteriorly, where each forms an obtuse, rounded, subcompressed protuberance, expanding as it passes backwards and bifurcating. The inner branch, 3 inches in length, uniting with its fellow, forms a long and slender trihedral process, dividing the prepalatine fissure, at its upper part, into two: the ridged summit of this process is grooved at its fore-part. The outer process of the premaxillary (22′), which answers to its ascending branch (branche montante of Cuvier) in ordinary mammals, forms the horizontal lower part of the boundary of the external bony nostril, and terminates obtusely a little behind the angle between that part and the vertical part of the boundary, filling up the before-mentioned maxillary notch: the length of this process is 3½ inches. The entire length of the premaxillary is 4½ inches: the obtuse anterior ends of the premaxillaries are partially separated by a notch.

The relative size,shape and connexions of the lacrymal bone are better defined in one of the crania of the Scelidothere in the British Museum than in any other Megatherioid fossil which has hitherto come under my inspection: this bone (Plate VIII. figs. 1 & 2, 73) forms the anterior two-thirds of the upper boundary of the orbit, where it is wedged between the maxillary and the frontal, articulating by about half an inch of the upper border with the nasal bone, and for about the same extent by its anterior and inferior angle with the malar: it is semioval in shape; irregularly convex externally, and perforated near its anterior border obliquely by the lacrymal canal (l), the orifice of which is 6 lines in diameter. The bone forms a slight protuberance behind the orifice, which appears to be outside the upper and fore part of the orbit. The breadth of the lacrymal bone is 2 inches. The size of the lacrymal foramen equals that in the Megathere, and is twice the size of that in the Mylodon: in its extraorbital position it differs from both. The lacrymal canal is continued inward and forward, and then grooves obliquely the inner side of the facial plate of the maxillary, as above described. The secretion of the gland may finally have entered the fore-part of the mouth by the premaxillary fissure.

The malar (Plate VIII. fig. 1, 26) presents the characteristic form and development of that bone in the Sloth tribe, with the same absence of the postorbital process as in the Mylodon, and a suppression of the zygomatic process (z) to a degree which brings it nearly to the condition of the malar in the existing Sloths. The fore part of the malar (26) forms the fore part of the orbit, articulating by its upper end with the lacrymal (73), and by its fore surface with the outstanding malar process of the maxillary (21′). Becoming free, the malar forms a stem with a semi-elliptic transverse section, slightly convex externally, very convex internally, 9 lines in diameter: it then, extending

[page] 106

downward and backward, rapidly expands, decreasing in thickness, and bifurcates. One branch ascends with a slight twist, forming the suprazygomatic process (8), and having an obtuse rudiment of the true zygomatic process (z) on its posterior border. The suprazygomatic process appears, in the natural position of the bone, to touch or rest upon the end of the zygomatic process of the temporal (27). The descending process (d) is broader and thinner; is gently concave, is directed obliquely downward and backward, and terminates obtusely.

The cranial cavity is 7 inches in fore and aft extent, including the cavity occupied by the olfactory ganglions, which is 1½ inch long: the greatest transverse diameter of the cavity is 4 inches 9 lines, which corresponds with the back part of the cerebral hemispheres. A low tentorial ridge is continued from the upper edge of the petrosal, in a direction which shows that the cerebellum lay wholly behind the cerebrum; but the major part of the tentorium was membranous, as in the Sloths and true Ant-eaters, not osseous as in the Manis. In the Orycteropus a sharp bony ridge extends from the petrosal into each side of the tentorium. The greatest vertical diameter of the cerebrum of the Scelidothere appears to have been 2½ inches; that of the cerebellum and medulla oblongata 2 inches 3 lines: the transverse diameter of the cerebellum was about 3 inches 9 lines, its fore and aft diameter about 2 inches. The inner surface of the cranial cavity indicates several convex masses of cerebellar convolutions, and also a few simple parallel longitudinal convolutions upon the upper and lateral parts of the cerebral hemispheres.

The small relative size of the brain of the Scelidothere is most clearly demonstrated; it. was scarcely one-fourth part the length of the skull: both this proportion and the relative position of its principal masses, succeeding one another lengthwise as in reptiles, closely accord with the low general condition of the cerebral organ in the existing species of the Order Bruta.

The upper part of the basisphenoid is impressed with a broad and shallow 'sella turcica,' bounded laterally by two grooves leading forwards and inwards from the carotid foramina. The line of junction between the basisphenoid and basioccipital is indicated by a slight transverse elevation which bounds the 'sella' behind: a low median protuberance forms the anterior boundary: there are neither anterior nor posterior clinoid processes. External to the carotid canal there is a wide groove leading to the foramen ovale. This foramen (Plate VIII. fig. 2 l), though absolutely less than in the Mylodon, is relatively larger as compared with the precondyloid foramen, and indicates that the tongue was more sensitive and less muscular or bulky in the Scelidothere; but, in reasoning from the size of the foramen ovale, it must be kept in mind that certain branches both of the second and third divisions of the fifth pair of nerves were associated with the persistence of large dental pulps of which they regulated the formative force. Anterior to the foramen ovale, and at the termination of the large common groove lodging the trunk of the fifth pair of nerves, is the inner orifice of the canal representing the foramen rotundum (ib. r); the diameter of this canal is 5 lines, being somewhat less than that of the foramen ovale.

[page] 107

The length of the lower jaw (Plate VIII. figs. 4 & 5) is 1 foot 6 inches 9 lines. The horizontal rami, each 3 inches 8 lines in depth at the base of the coronoid process (b), decrease in that diameter, at first gradually, then more rapidly at the beginning of the symphysis (d), to its end (d′): they are confluent at the symphysis for an extent of 6 inches 9 lines (ib. fig. 5 d, d′). The ascending ramus of the jaw, or posterior apophysiary part, presents the broad, backwardly produced, slightly inflected angular process (c) common to all the Megatherioids; in shape and other minor characters it most resembles that in the Mylodon. The condyle (a) is transversely oblong, with the inner and smaller end bent a little back: the articular surface is nearly flat. The posterior border of the ramus is continued from the reflected inner angle of the condyle, the coronoid process (b) from the fore-part of the condyle near the thick outer end: the extent of the base of the coronoid process is 4 inches, the deep notch dividing its reflected apex (b) from the condyle (a) is but 7 lines wide: the fore margin of the process describes a regular convexity: the outer side of the process is flat, the inner side convex near the anterior border, slightly concave elsewhere: the low ridge bounding anteriorly that concavity is continued into another, which runs along the middle of the inner side of the horizontal ramus for 2 or 3 inches. The angular process (c) is concave internally: its upper border is notched, and its outer convex side is grooved for muscular attachments. The coronoid and angular processes are obviously the two great handles of the jaw, which, grasped by the opposing masses of muscles, enabled them to move with effect the lower molars horizontally upon the upper ones; the flat condyle and broad flat surface for its articulation offering no obstacle to those grinding movements. The dental canal commences by an oblique orifice, 6 lines in diameter, situated 2 inches behind the last alveolus (i v), and from 1 to 1½ inch below the level of its outlet. The canal soon bifurcates, the outer branch leading to the large orifice (ib. fig. 4 g) outside and below the anterior part of the base of the coronoid process; the inner division supplies the teeth, and then subdivides into two small canals which have their outlets on the outside of the symphysis, from 2 to 4 inches distance from its extremity. These 'mental foramina' (h, h) are small in comparison with those in the Mylodon. The horizontal ramus is moderately convex below and tumid externally at the molar region.

The series of four alveoli in each ramus measures 4 inches 3 lines. The outer alveolar wall describes a slight curve, convex outwards; it is higher than the inner one, and forms a kind of 'bead' or rounded prominent border externally: the whole alveolar part of the ramus inclines inwards. The inner alveolar wall is thin, straight, nearly parallel with that of the opposite side; but a little divergent anteriorly, where it blends with the outer wall to form the obtuse upper and outer border of the long symphysial part of the jaw. This part, near 7 inches in length, deeply excavated behind, becomes gradually shallower to the end, which is cut square off, and is slightly notched in the middle. There is a slight median prominence on the under part of the symphysis near the anterior end.

The teeth of the Scelidothere, as in the other known gravigrade Sloths, are eighteen

[page] 108

in number, all of one kind, arranged according to the Megatherioid formula: viz. m, 5—5/4—4=:18. They are simple, long, fangless, and of the same thickness from the implanted to the exposed end; the former is excavated by a deep conical cavity, the latter worn into a shallow depression, and somewhat obliquely, reaching to the level of the inner alveolar wall in the upper jaw, and to the outer one in the lower jaw.

In the upper jaw the shape of the anterior tooth (Plate IX.i) is slightly modified in two of the skulls of the Scelidothere from Buenos Ayres in the British Museum. In one, its transverse section more resembles that of the same tooth figured in the fragment described in my original memoir on the genus*, the straightest and broadest side being the inner one: in the other skull the outer side shows those proportions; the teeth being naturally implanted in both skulls: the general form of this section is an irregular oval, 11 lines in long diameter; the length of the tooth is 2½ inches; it is very slightly curved, with the convexity directed forwards and inwards.

The other four teeth gradually diminish in size, and are more or less three-sided with the angles rounded off, in transverse section; the longest side being turned outwards and backwards, and being slightly concave: the opposite angle is more developed in one than in the other skull, in the second and third molars: these are more nearly equal in size than the last two molars. The longest diameter of the grinding surface of the penultimate molar is 9 lines, that of the last molar 7½ lines. The longitudinal extent of the dental series in both adult skulls is 4 inches 4 lines. The length of the last tooth is 2 2/3 inches; that of each of the three middle teeth is 3 inches.

In the lower jaw (Plate IX. fig. 2) the first molar (i) is broader than the second and third: its transverse section is triangular with the angles rounded off, the longest side turned inwards. The second (ii) and third (iii) teeth are of equal size and similar shape, the transverse section being triangular with the apex thick and obtuse; the base is much shorter than the sides, is slightly indented, and turned outwards and a little forwards; the rounded apex in the opposite direction; the anterior side is more concave than the opposite side. The last molar (iv) is the largest and most complex, its grinding surface consisting of two lobes produced by two opposite unequal-sided channels traversing the tooth longitudinally: the lobes are subequal, and placed obliquely one before the other.

The teeth consist of a central axis of vaso-dentine, a wall between 1 line and 2 lines thick of hard dentine, and a very thin outer coat of cement.

Comparison of the Skull and Dentition.

In the comparative simplicity of the malar bone and of the grinding surface of the teeth, in their close and regular arrangement and in the narrowness of the palate, in the incomplete orbit and the uninterrupted or more simple outline of the under jaw, the Scelidothere manifests its nearer affinity to the Mylodon than to the Megathere; but in many respects it is an intermediate form, as is shown by the long premaxillaries and the corresponding length and slenderness of the symphysis of the lower jaw. The occi-

* Op. cit. Pl. XXIII. fig. 3, i.

[page] 109

pital plane is more vertical than in the Megathere, and still more so than in the Mylodon or in the existing Sloths. In the minor development of the mastoid as compared with the paroccipital, the Scelidothere resembles the Mylodon more than it does the Megathere: it differs from both in the much smaller surface of articulation for the stylohyal; and, apparently, by the want of junction of the malar with the squamosal. The lower jaw, whilst it resembles that of the Mylodon in the form of the ascending ramus and of the dentigerous part, differs in the unusual prolongation of the long and slender symphysis, and in the smaller size of the mental foramina: the intermediate character between Mylodon and Megathere is well illustrated in the mandible of the Scelidothere. The dentition of the Scelidothere differs from that of the Megathere, and resembles that of the Mylodon in the simple concavity of the grinding surface; but it differs from the dentition of the Mylodon in the first upper molar not being divided by a disproportionate interspace from the rest, and by the more unequal sides of the triangular grinding surface. The second molar, in the Mylodon, presents an elliptical transverse section instead of the reniform or subtriangular shape. The third and fourth molars of the Scelidothere are more compressed than in the Mylodon, and their long axis is from before backwards, instead of being transverse. The fifth molar is relatively smaller than in the Mylodon, approaching to that in the Megathere. In the lower jaw of the Scelidothere the differences in the form of the teeth are equally manifest, especially in the prismatic form of the first molar: it is elliptical in the Mylodon. The last molar of the Mylodon robustus has the second lobe larger than the first: in the Mylodon Darwinii the proportions of the lobes more resemble those in the Scelidothere. The two middle teeth differ more markedly from the corresponding ones in any of the species of Mylodon: the second molar in M. robustus has a triangular transverse section with the base turned inwards and indented: the third molar is subquadrate.

The retention of the mylodontal character of dentition in three forms of the genus, with modifications not surpassing those of specific value, renders it probable that other species of Scelidotherium may have existed besides the one under description. The generic distinction of Scelidotherium from Mylodon is strengthened by the additional characters which the complete crania in the British Museum have brought to light.

In conclusion I may remark, that, as our knowledge of the great Megatherioid animals increases, the definition of their distinctive characters demands more extended comparison of particulars: hence in each successive attempt at a restoration of these truly remarkable extinct South American quadrupeds, there results a description of details which might else seem prolix and uncalled-for.

I have only to add, that the allotment of the Government Grant for drawings of rare or nondescript fossils has enabled me to bring before the Society without delay the present account, with adequate illustrations of the entire skull of the Scelidotherium leptoeephalum.

MDCCCLVII. Q

[page] 110

Comparative Table of Dimensions of the Skull of the SCELIDOTHERE, MYLODON, and MEGATHERE.

| Scelidotherium leptocephalum. | Mylodon robustus. | Megatherium americanum. | |||||||

| CRANIUM. | ft. | in. | lin. | ft. | in. | lin. | ft. | in. | lin. |

| Length from the occipital condyles to the fore-end of the upper jaw | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Length from the occipital condyles to the fore-part of the malar bone | 0 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| Length from the fore-part of the malar bone to the fore-end of the upper jaw | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 6 |

| Breadth across the widest part of the zygomatic arches | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9 | |||

| Least breadth at the interspace of those arches | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Breadth of the fore-part of the nasal bones | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| MANDIBLE. | |||||||||

| Length | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Breadth between the hinder ends (angles) of the rami | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Breadth between the condyles | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Breadth between the posterior sockets of the teeth | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Breadth between the anterior sockets of the teeth | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Breadth across the fore-part of the symphysis | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Depth of ascending ramus from the upper part of the condyle | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Depth of ascending ramus at the fore-part of the base of the coronoid process | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Depth of horizontal ramus at the fore-part of the first socket | 0 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Length of the symphysis following the outer curve | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fore and aft extent of base of coronoid process | 0 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| From the back part of the condyle to the end of the angular process | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| From the end of the angular process to the last socket | 0 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 7 |

| From the first socket to the anterior margin of the jaw | 0 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Extent of the alveolar series | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Breadth of the condyle | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLATES.

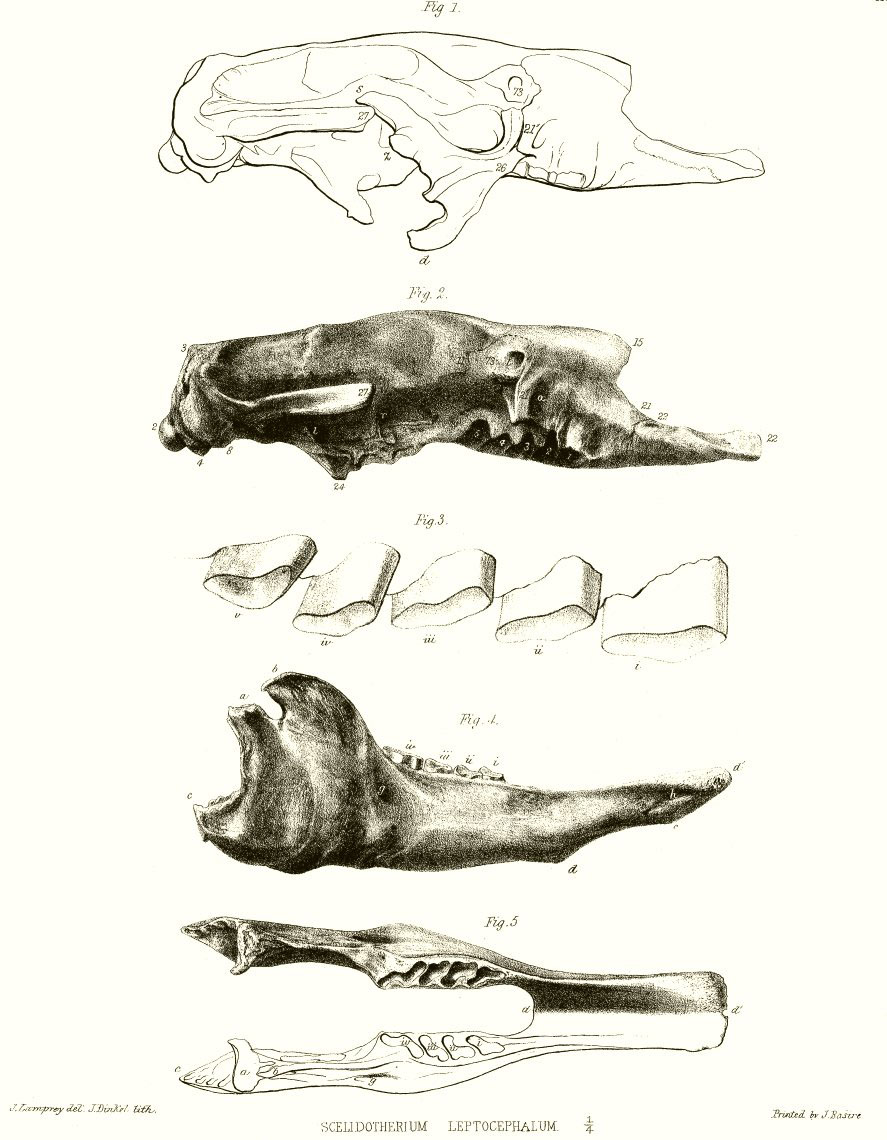

PLATE VIII.

One-fourth nat. size.

Fig. 1. Side view of the cranium, with the malar bone, in outline.

Fig. 2. Side view of a cranium, wanting the malar bone.

Fig. 3. Side view of upper molars. Nat. size.

Fig. 4. Side view of the mandible.

Fig. 5. Upper view of the mandible.

PLATE IX.

Nat. size.

Fig. 1. Base view of skull.

Fig. 2. Grinding surface of the upper molars.

Fig. 3. Grinding surface of the lower molars.

[Plate VIII]

[Plate IX]