[page ii]

Let knowledge grow from more to more,

But more of reverence in us dwell;

That mind and soul, according well,

May snake one music as before,

But vaster....

IN MEMORIAM.

[page iii]

THE REIGN OF LAW

By

THE DUKE OF ARGYLL

ALEXANDER STRAHAN, PUBLISHER

56 LUDGATE HILL, LONDON

1867

[page iv]

[page v]

PREFACE.

SOME portions of this work have already appeared at various times in the Edinburgh Review, in Good Words, and in Addresses to the Royal Society of Edinburgh during the years in which I had the honour of being President of that Body. The deep interest of the matter dealt with in those Papers has induced me to expand them, to add new chapters on other aspects of the same subject, and to publish the whole in a connected form.

Among many other deficiencies which may be observed in this Volume, there is one which demands explanation, lest a serious misunder

[page] vi

standing should arise. I had intended to conclude with a chapter on "Law in Christian Theology." It was natural to reserve for that chapter all direct reference to some of the most fundamental facts of Human nature.' Yet without such reference the Reign of Law, especially in the "Realm of Mind," cannot even be approached in some of its very highest and most important aspects. For the present, however, I have shrunk from entering upon questions so profound, of such critical import, and so inseparably connected with religious controversy. In the absence of any attempt to deal with this great branch of the inquiry, as well as in many other ways, I am painfully conscious of the narrow range of this work. I can only offer it as a very small contribution to the discussion of a boundless subject.

INVERARAY, October 1866.

[page vii]

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

PAGE

I. THE SUPERNATURAL, 1

II. LAW;—ITS DEFINITIONS, 53

III. CONTRIVANCE A NECESSITY ARISING OUT OF THE REIGN OF LAW—EXAMPLE IN THE MACHINERY OF FLIGHT, 128

IV. APPARENT EXCEPTIONS TO THE SUPREMACY OF PURPOSE, 181

V. CREATION BY LAW, 217

VI. LAW IN THE REALM OF MIND, 295

VII. LAW IN POLITICS, 354

ILLUSTRATIONS.

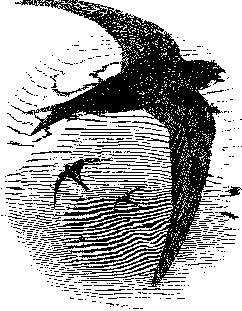

THE SWIFT, Facing 154

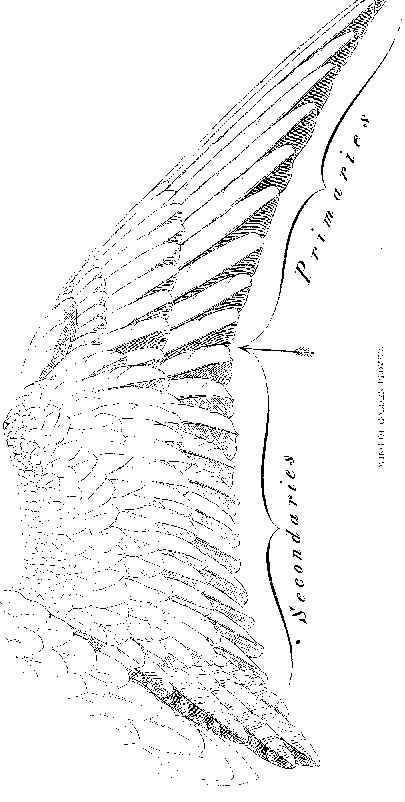

WING OF GANNET, 162

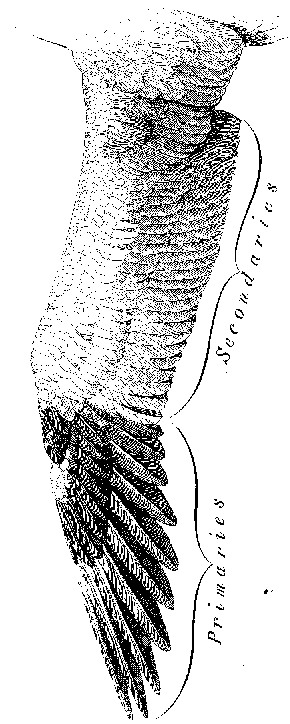

WING OF GOLDEN PLOVER, 164

SPARROW-HAWK—MERLIN—KESTREL HOVERING, 166

[page viii]

[page 1]

THE REIGN OF LAW.

CHAPTER I.

THE SUPERNATURAL.

THE Supernatural—what is it? What do we mean by it? How do we define it? M. Guizot* tells us that belief in it is the special difficulty of our time—that denial of it is the form taken by all modern assaults on Christian faith; and again, that acceptance of it lies at the root, not only of Christianity, but of all positive religion whatever. These questions, then, concerning the Supernatural are questions of first importance. Yet we find them seldom distinctly put, and still more seldom distinctly answered. This is a

* L'Eglise et la Société Chretienne en 1861, ch. iv. p. 19.

[page] 2

capital error in dealing with any question of philosophy. Half the perplexities of men are traceable to obscurity of thought hiding and breeding under obscurity of language."The Supernatural" is a term employed often in different, and sometimes in contradictory, senses. It is difficult to make out whether M. Guizot himself means to identify belief in the Supernatural with belief in the existence of a God, or with belief in a particular mode of Divine action. But these are ideas quite separable and distinct. There may be some men who disbelieve in the Supernatural only because they are absolute atheists; but it is certain that there are others who have great difficulty in believing in the Supernatural who are not atheists. What they doubt or deny is, not that God exists, but that He ever acts, or perhaps can act, unless in and through what they call the "Laws of Nature." M. Guizot, indeed, tells us that "God is the Supernatural in a Person." But this is a rhetorical figure rather than a definition. He may, indeed, contend that it is inconsistent to believe in a God, and yet to disbelieve in the Supernatural; but

[page] 3

he must admit, and indeed does admit, that such inconsistency is found in fact.

Theological and philosophical writers frequently use the Supernatural as synonymous with the Superhuman. But of course this is not the sense in which any one can have any difficulty in believing in it. The powers and works of Nature are all superhuman—more than Man can account for in their origin—more than he can resist in their energy—more than he can understand in their effects. This, then, cannot be the sense in which so many minds find it hard to accept the Supernatural ; nor can it be the sense in which others cling to it as of the very essence of their religious faith. What, then, is that other sense in which the difficulty arises? Perhaps we shall best find it by seeking the idea which is competing with it, and by which it has been displaced. It is the Natural which has been casting out the Supernatural—the idea of Natural Law,—the universal reign of a fixed Order of things. This idea is a product of that immense development of the physical sciences which is characteristic of our time. We cannot read a

[page] 4

periodical, or go into a lecture-room, without hearing it expressed. Sometimes, but rarely, it is stated with accuracy, and with due recognition of the limits within which Law can be said to comprehend the phenomena of the world. But generally it is expressed in language vague and hollow, covering inaccurate conceptions, and confounding under common forms of expression ideas which are essentially distinct. The mere ticketing and orderly assortment of external facts is constantly spoken of as if it were in the nature of Explanation, and as if no higher truth in respect to natural phenomena were to be attained or desired. And herein we see both the result for which Bacon laboured, and the danger against which Bacon prayed. It has been a glorious result of a right method in the study of Nature, that with the increase of knowledge the "human family has been endowed with new mercies." But every now and then, for a time at least, from " the unlocking of the gates of sense, and the kindling of a greater natural light, incredulity and intellectual night have arisen in our minds."

"This also we humbly beg that human things may not preju-

[page] 5

But let us observe exactly where and how the difficulty arises. The Reign of Law in Nature is, indeed, so far as we can observe it, universal. But the common idea of the Supernatural is that which is at variance with natural Law, above it, or in violation of it.' Nothing, however wonderful, which happens according to Natural Law, would be considered by any one as Supernatural. The law in obedience to which a wonderful thing happens may not be known; but this would not give it a supernatural character, so long as we assuredly believe that it did happen according to some law. Hence, it would appear to follow that a man thoroughly possessed of the idea of Natural Law as universal, never could admit anything to be supernatural; because on seeing any fact, however new, marvellous, or incomprehensible, he would escape into the conclusion that it was the result of some natural Law of which lie had before been ignorant. No one will deny that, in respect to the vast dice such as are Divine, neither that from the unlocking of the gates of sense, and the kindling of a greater natural light, anything of incredulity or intellectual night may arise in our minds towards Divine mysteries."—The Student's Prayer, Bacon's Works.

[page] 6

majority of all new and marvellous phenomena, this would be the true and reasonable conclusion. It is not the conclusion of pride, but of humility of mind. Seeing the boundless extent of our ignorance of the natural laws which regulate so many of the phenomena around us, and still more of so many of the phenomena within us, nothing can be more reasonable than to conclude, when we see something which is to us a wonder, that somehow, if we only knew how, it is " all right " —all according to the constitution and course of Nature. But then, to justify this conclusion, we must understand Nature in the largest sense,—as including all that is

"In the round ocean, and in the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of mall."

must understand it as including every agency which we see entering, or can conceive from analogy as capable of entering, into the causation of the world. First and foremost among these is the agency of our own Mind and Will. Yet, strange to say, all reference to this agency is often tacitly excluded when we speak of the laws

* Tintern Abbey.—Wordsworth.

[page] 7

of Nature. One of our most distinguished living teachers of physical science- 'began, not long ago, a course of lectures on the phenomena of Heat by a rapid statement of the modern doctrine of the Correlation of Forces—how the one was convertible into the other-how one arose out of the other—how none could be evolved except from some other as a pre-existing source. " Thus," said the lecturer, "we see there is no such thing as spontaneousness in Nature." 'I What!—not in the lecturer himself? Was there no " spontaneousness " in his choice of words—in his selection of materials—in his orderly arrangement of experiments with a view to the exhibition of particular results? It is not probable that the lecturer was intending to deny this; it simply was that he did not think of it as within his field of view. His own Mind and Will were then dealing with the " laws of Nature," but it did not occur to him as forming part of those laws, or, in the same sense, as subject to them.

Does Man, then, not belong to Nature? Is he above it—or merely separate from it, or a viola-

* Professor Tyndall.

[page] 8

tion of it? Is he supernatural? If so, has he any difficulty in believing in himself? Of course not. Self-consciousness is the one truth, in the light of which all other truths are known. Cogito, ergo sum-; or volo, ergo sum—this is the one conclusion which we cannot doubt, unless Reason disbelieves herself. Why, then, are the faculties of the human mind and body not habitually included among the "laws of Nature?" Because a fallacy is getting hold upon us from a want of definition in the use of terms. "Nature" is being used in the narrow sense of physical nature; and the whole world in which we ourselves live, and move, and have our being is excluded from it. But these selves of ours do belong to Nature. If we are ever to understand the difficulties in the way of believing in the Supernatural, we must first keep clearly in view what we are to understand as included in the Natural. Let us never forget, then, that the agency of Man is of all others the most natural — the one with which we are most familiar—the only one, in fact, which we can be said, even in any measure, to understand. When any wonderful event can

[page] 9

be referred to the contrivance or ingenuity of Man, it is thereby at once removed from the sphere of the Supernatural, as ordinarily understood. It must be remembered, however, that we are now only seeking a clear definition of terms; and that provided this other meaning be clearly agreed upon, the Mind and Will of Man may be considered as separate from " nature," and belonging to the Supernatural. This view is taken in an able treatise on "Nature and the Supernatural," by Dr Bushnell, an American clergyman.* Dr Bushnell says:—" That is supernatural, whatever it be, that is either not in the chain of natural cause and effect, or which acts on the chain of cause and effect in nature, from without the chain." Again:—" If the processes, combinations, and results of our system of nature are interrupted or varied by the action, whether of God, or angels, or men, so as to bring to pass what would not come to pass in it by its own internal action, under the laws of mere cause and effect, such variations are in like manner supernatural." There is no other

* Nature and the Supernatural, as together constituting the one System of God. By Horace Bushnell, D.D. Edinburgh, 1860.

[page] 10

objection to this definition of the Supernatural, than that it rests upon a limitation of the terms "Nature" and "natural," which is very much at variance with the sense in which they are commonly understood. There is, indeed, a distinction which finds its expression in common language between the works of Man and the works of Nature. A honeycomb, for example, would be called a work of Nature, but not a steam-engine. This distinction is founded on a true perception of the fact that the Mind and Will of Man belong to an order of existence very different from physical laws, and very different also from the fixed and narrow instincts of the lower animals.? It is a distinction bearing witness to the universal consciousness that the Mind of Man has within it something of a truly creative energy and force—that we are in a sense "fellow-workers with God," and have been in a measure "made partakers of the Divine nature." But in that larger and wider sense in which we are here speaking of the Natural, it contains within it the whole phenomena of Man's intellectual and spiritual nature, as part, and the most familiar of all parts, of the visible system of

[page] 11

things. In all ordinary senses of the term, Man and his doings belong to the Natural, as distinguished from the Supernatural.

We are thus coming nearer to some precise understanding of what the Supernatural may be supposed to mean. But before we proceed, there is another question which must be answered.—What is the relation in which the agency of Man stands to the physical laws of Nature? The answer, in part at least, is plain. His power in respect to those laws extends only first to their discovery and ascertainment, and then to their use. He can establish none: he can suspend none. All he can do is to guide, in a limited degree, the mutual action and reaction of the laws amongst each other. They are the tools with which he works—they are the instruments of his Will. In all he does or can do he must employ them. His ability to use them is limited both by his Want of knowledge and by his want of power. The more he knows of them, the more largely he can employ them, and make them ministers of his purposes. This, as a general rule, is true; but it is subject to the second limitation just

[page] 12

pointed out. Man already knows far more than he has power to convert to use. It is a true observation of Sir George Lewis* that Astronomy, for example, in its higher branches, has an interest almost purely scientific. It reveals to our knowledge perhaps the grandest and most sublime of the physical laws of Nature. But a much smaller amount of knowledge would suffice for the only practical applications which we have yet been able to make of these laws to our own use. Still, that knowledge has a reflex influence on our knowledge of ourselves, of our powers, and of the relations which subsist between the constitution of our own minds and the constitution of the universe. And in other spheres of inquiry, advancing knowledge of physical laws has been constantly accompanied with advancing power over the physical world. It has enabled us to do a thousand things, any one of which, a few generations ago, would have been considered supernatural. Nor can it be said that this judgment of their character would have been erroneous. These things would have been superhuman then, though they

* Astronomy of the Ancients, p. 254.

[page] 13

are not superhuman now. The same lecturer who told his audience that there was nothing spontaneous in Nature proceeded, by virtue of his own knowledge of natural laws, and by his selecting and combining power, to present a whole series of phenomena—such as ice frozen in contact with red-hot crucibles—which certainly did not belong to the "ordinary course of Nature." Such an exhibition a few centuries ago, would beyond all doubt have subjected the lecturer on Heat to painful experience of that condition of matter. Nevertheless the phenomena so exhibited were natural phenomena—in this sense, that they were the product of natural laws. Only these laws were combined in action under extraordinary conditions, and these conditions were governed by the purpose and design of the lecturer, which design was "spontaneous," if there is any meaning in the word. In like manner, if the progress of discovery is as rapid during the next 400 years as it has been during the last period of the same extent, men will be able to do many things which would now appear to be "supernatural". There is no difficulty in conceiving how a complete knowledge of

[page] 14

all natural laws would give, if not complete power, at least degrees of power immensely greater than those which we now possess. Power of this kind, then, however great in degree, clearly does not answer that idea of the Supernatural which so many reject as inconceivable. What, then, is that idea? Have we not traced it to its den at last? By " supernatural " power, do we not mean power independent of the use of means, as distinguished from power depending on knowledge—even infinite knowledge—of the means proper to be employed ?

This is the sense—probably the only sense—in which the Supernatural is, to many minds, so difficult of belief. No man can have any difficulty in believing that there are natural laws of which he is ignorant; nor in conceiving that there may be Beings who do know them, and can use them, even as he himself now uses the few laws with which he is acquainted. The real difficulty lies in the idea of Will exercised without the use of means—not in the exercise of Will through means which are beyond our knowledge."

Now, have we any right to say that belief in this

[page] 15

is essential to all Religion? If we have not, then it is only putting, as so many other hasty sayings do put, additional difficulties in the way of Religion. The relation in which od stands to those rules of His government which are called " laws," is, of course, an inscrutable mystery to us. But those who believe that His Will does govern the world, must believe that ordinarily, at least, He does govern it by the choice and use of means. Nor have we any certain reason to believe that He ever acts otherwise. Extraordinary manifestations of His Will—signs and wonders—may be wrought, for aught we know, by similar instrumentality—only by the selection and use of laws of which Man knows and can know nothing, and which, if he did know, he could not employ.*

Here, then, we come upon the question of

* This chapter, originally published as an article in the Edinburgh Review for Oct. 1862, has been referred to in the remarkable work of Mr Lecky on "The Rise and Influence of Rationalism in Europe," (vol. i. ch. ii. p. 195 note,) as conveying "a notion of a miracle which would not differ generically from a human act, though it would still be strictly available for evidential purposes." I am quite satisfied with this definition of the result. Beyond the immediate purposes of benevolence which were served by almost all the miracles of the New Testament, the only other purpose which

[page] 16

miracles—how we understand them? what we would define them to be? The common

idea of a miracle is, a suspension or violation of the laws of Nature. This

is a definition which places the essence of a miracle in a particular method

of operation. But there is another definition which passes this by altogether,

and dwells only on the agency by which, and the purpose for which, a wonderful

work is wrought. "We would confine the word miracle," says Dr M'Cosh, * "to

those events which were wrought in our world as a sign or proof of God making

a supernatural interposition, or a revelation to Man." This definition is defective

in so far as it uses the word " supernatural," which, as we have seen, itself

requires definition as much as miracle. But from the general context and many

individual passages in his treatise, it is sufficiently clear that the two conditions

essential in Dr

is ever assigned to them is an " evidential purpose"—that is, a purpose that they might serve as signs of the presence of superhuman knowledge, and of the working of superhuman power. They were performed—in short—to assist faith, and not to confound reason.

* The Supernatural in relation to the Natural. By the Rev. James M'Cosh, LL.D. Macmillan, Cambridge, 1861.

[page] 17

M'Cosh's view of a miracle, are that they are wrought by a Divine power for a Divine purpose, and are of a nature such as could not be wrought by merely human contrivance. In this sense a miracle means a superhuman work. This definition of a miracle does not exclude the idea of God working by the use of means, provided they are such means as are out of human reach. Indeed, in an important note, (p. 149,) Dr M'Cosh seems to admit that miracles are not to be considered "as against Nature" in any other sense than that in which " one natural agent may be against another—as water may counteract fire." Mr Mansel, in his " Essay on Miracles," adopts the word "superhuman" as the most accurate expression of his meaning. He says, "A superhuman authority needs to be substantiated by superhuman evidence; and what is superhuman is miraculous." * It is important to observe that this

* Aids to Faith, p. 35. In another passage, (p. 2c,) Mr Mansel says that in respect to the great majority of the miracles recorded in Scripture, "the supernatural element appears . . . in the exercise of a personal power transcending the limits of man's will. They are not so much supermaterial as superhuman."

[page] 18

definition does not necessarily involve the idea of a "violation of the laws of Nature." It does not involve the idea of the exercise of Will apart from the use of means. It does not involve, therefore, that idea which appears to many so difficult of conception. It simply supposes, without any attempt to fathom the relation in which God stands to His own " laws," that out of His infinite knowledge of these laws, or of His infinite power of making them the instruments of His Will, He may and He does use them for extraordinary indications of His presence.

The reluctance to admit as belonging to the domain of Nature any special exertion of Divine power for special purposes, stands really in very close relationship to the converse notion, that where the operation of natural causes can be clearly traced, there the exertion of Divine power and Will is rendered less certain and less convincing. This is the idea which lies at the root of Gibbon's famous chapters on the spread of Christianity. He labours to prove that it was due to natural causes. In proving this, he evidently thinks he is disposing of the notion that

[page] 19

Christianity spread by Divine power; whereas he only succeeds in pointing out some of the means which were employed to effect a Divine purpose. In like manner, the preservation of the Jews as a distinct People during so many centuries of complete dispersion, is a fact standing nearly if not absolutely alone in the history of the world. It is at variance with all other experience of the laws which govern the amalgamation with each other of different families of the human race. The case of the Gipsies has been referred to as somewhat parallel. But the facts of this case are doubtful and obscure, and such of them as we know involve conditions altogether dissimilar in kind. It is not surprising, therefore, that the preservation of the Jews, partly from the relation in which it stands to the apparent fulfilment of Prophecy, and partly from the extraordinary nature of the fact itself, is tacitly assumed by many persons to come strictly within the category of miraculous events. Yet in itself it is nothing more than a striking illustration how a departure from the "ordinary course of nature" may be effected through the instrumentality

[page] 20

of means which are natural and comprehensible, An extraordinary resisting power has been given to the Jewish People against those dissolving and disintegrating forces which have caused the disappearance of every other race placed under similar conditions. They have been torn from home and country, and removed, not in a body, but in scattered fragments, over the world. Yet they are as distinct from every other people now as they were in the days of Solomon. Nevertheless this resisting power, wonderful though it be, is the result of special laws, overruling those in ordinary operation. It has been effected by the use of means. Those means have been superhuman—they have been beyond human contrivance and arrangement. But they belong to the region of the Natural. They belong to it not the less, but all the more, because in their concatenation and arrangement they seem to indicate the purpose of a living Will seeking and effecting the fulfilment of its designs. This is the manner after which our own living Wills in their little sphere effect their little objects. Is it difficult

[page] 21

to believe that after the same manner also the Divine Will, of which ours is the image only, works and effects its purposes ?

Our own experience shows that the universal Reign of Law is perfectly consistent with a power of making those laws subservient to design—even when the knowledge of them is but slight, and the power over them slighter still. How much more easy, how much more natural, to conceive that the same universality is compatible with the exercise of that Supreme Will before which all are known, and to which all are servants! What difficulty in this view remains in the idea of the Supernatural? Is it any other than the difficulty in believing in the existence of a Supreme Will—in a living God? If this be the belief of which M. Guizot speaks when he says that it is essential to religion, then his proposition is unquestionably true. In this sense the difficulty of believing in the Supernatural, and the difficulty of believing in pure Theism, is one and the same. But if he means that it is necessary to Religion to believe in even the occasional " violation of law,"—if he means that without such belief

[page] 22

signs and wonders cease to be evidences of Divine power,—then he announces a proposition which cannot be sustained. There is nothing in Religion incompatible with the belief that all exercises of God's power, whether ordinary or extraordinary, are effected through the instrumentality of means—that is to say, by the instrumentality of natural laws brought out, as it were, and used for a Divine purpose. To believe in the existence of miracles, we must indeed believe in the Superhuman and in the Super material. But both these are familiar facts in Nature. We must believe also in a Supreme Will and a Supreme Intelligence; but this our own Wills and our own Intelligence not only enable us to conceive of, but compel us to recognise in the whole laws and economy of Nature. Her whole aspect answers intelligently to our intelligence—mind responding to mind as in a glass."* Once admit that there is a Being who—irrespective of any theory as to the relation in which

* Beginning Life: Chapters for Young Men on Religion, Study, and Business. By John Tulloch, D.D., Principal of St Mary's College, St Andrews. Chap. iii., The Supernatural. Edinburgh, 1860. P. 29.

[page] 23

the laws of Nature stand to His own Will-has at least an infinite knowledge of those laws, and an infinite power of putting them to use-then miracles lose every element of inconceivability. In respect to the greatest and highest of all—that restoration of the breath of life which is not more mysterious than its original gift—there is no answer to the question which Paul asks, ' Why should it be thought a thing incredible by you that God should raise the dead?

This view of miracles is well expressed by Principal Tulloch:—

"The stoutest advocate of interference can mean nothing more than that the Supreme Will has so moved the hidden springs of nature that a new issue arises on given circumstances. The ordinary issue is supplanted by a higher issue. The essential facts before us are a certain set of phenomena, and a Higher Will moving them. How moving them? is a question for human definition; but the answer to which does not and cannot affect the Divine meaning of the change. Yet when we reflect that this Higher Will is everywhere reason and wisdom, it seems a jester

[page] 24

as well as a more comprehensive view to regard it as operating by subordination and evolution rather than by 'interference' or 'violation.' According to this view, the idea of Law is so far from being contravened by the Christian miracles, that it is taken up by them and made their very basis. They are the expression of a Higher Law, working out its wise ends among the lower and ordinary sequences of life and history. These ordinary sequences represent nature — nature, however, not as an immutable fate, but a plastic medium through which a Higher Voice and Will are ever addressing us, and which, therefore, may be wrought into new issues when the Voice has a new message, and the Will a special purpose for us."

It is well worthy of remark, that Locke, who laid great stress on the Christian miracles, as attesting the authority of those who wrought them, declines, nevertheless, to adopt the common definition of that in which miraculous agency consists. " A miracle then," he says,

"I take to be a sensible operation, which, be-

* Beginning Life, &c., pp. 85, 86. By John Tulloch, D. D.

† A Discourse on Miracles.

[page] 25

ing above the comprehension of the spectator and, in his opinion, contrary to the established course of nature, is taken by him to be Divine." And in reply to the objection, that this makes a miracle depend on the opinions or knowledge of the spectator, he points out that this objection cannot be avoided by any of the definitions commonly adopted; because "it being agreed that a miracle must be that which surpasses the force of nature in the established steady laws of cause and effect, nothing can be taken to be a miracle but what is judged to exceed those laws. Now every one being able to judge of those laws only by his own acquaintance with nature, and his own notions of its force, which are different in different men, it is unavoidable that that should be a miracle to one man which is not so to another." In this passage Locke recognises the great truth, that we can never know what is above Nature unless we know all that is within Nature. But he misses another truth quite as important,—that a miracle would still be a miracle even though we did know the laws through which it was accomplished, provided those laws, though not beyond human knowledge,

[page] 26

were beyond human control. We might know the conditions necessary to the performance of a miracle, although utterly unable to bring those conditions about. Yet a work performed by the bringing about of conditions which are out of human reach, would certainly be a work attesting superhuman power.

Nevertheless so deeply ingrained in popular theology is the idea that miracles, to be miracles at all, must be performed by some violation or suspension of the laws of Nature, that the opposite idea of miracles being performed by the use of means is regarded by many with jealousy and suspicion. Strange that it should be thought the safest course to separate as sharply and as widely as we can between what we are called upon to believe in Religion, and what we are able to trace or understand in Nature! With what heart can those who cherish this frame of mind follow the great argument of Butler? All the steps of that argument—the greatest in the whole range of Christian philosophy—are founded on the opposite belief, that all the truths, and not less all the difficulties of Religion, have their type and

[page] 27

likeness in the "constitution and course of Nature." As we follow that reasoning, so simple and so profound, we find our eyes ever opening to some new interpretation of familiar facts, and recognising among the curious things of earth, one after another of the laws which, when told us of the spiritual world, seem so perplexing and so hard to accept or understand. To ask how much further this argument of the Analogy is capable of illustration and development, is to ask how much more we shall know of Nature. Like all central truths, its ramifications are infinite—as infinite as the appearance of variety, and as pervading as the sense of oneness in the universe of God.

But what of Revelation? Are its history and doctrines incompatible with the belief that God uniformly acts through the use of means? The narrative of Creation is given to us in abstract only, and is told in two different forms, both having apparently for their main, perhaps their exclusive object, the presenting to our conception the personal agency of a living God. Yet this narrative indicates, however slightly,

[page] 28

that room is left for the idea of a material process. "Out of the dust of the ground;" that is, out of the ordinary elements of Nature, was that Body formed which is still upheld and perpetuated by organic forces acting under the rules of Law. Nothing which Science has discovered, or can discover, is capable of traversing that simple narrative. On this subject M. Guizot lays great stress, as many others do, on what he calls the Supernatural in Creation, as distinguished from the operations now visible in Nature. "De quelle façon et par quelle puissance le genre humain a-t-il commencé sur la terre ?" In reply to this question, he proceeds to argue that Man must have been the result either of mere material forces, or of a supernatural power exterior to, and superior to matter. Spontaneous generation, he argues, supposing it to exist at all, can give birth only to infant beings—to the first hours, and feeblest forms of nascent life. But Man—the human pair—must evidently have been complete from the first; created in the full possession of their powers and faculties. " C'est â cette condition seulement qu'en appa-

[page] 29

raissant pour la première fois sur la terre fhomme aurait pu y vivre—s'y perpétuer, et y fonder le genre humain. Evidemment l'autre origine du genre humain est seul admissible, seul possible. Le fait surnaturel de la creation explique seul la première apparition de l'homme ici-bas."

This is a common, but not a very safe argument. If the Supernatural — that is to say, the Superhuman and the Supermaterial — cannot be found nearer to us than this, it will not be securely found at all. It is very difficult to free ourselves from this notion that by going far enough back, we can " find out God" in some sense in which we cannot find Him now. The certainty not merely of one, but of many successive Creations in the history of our Planet, and especially of a time comparatively recent, when Man did not exist, is indeed an effectual answer to the notion, if it be now ever entertained, of " all things having continued as they are since the Beginning." But those who believe that the existing processes of Nature can be accounted for by "Law," may as reasonably believe that those processes were commenced by the same vague

[page] 30

and mysterious agency. To accept the primeval narrative of the Jewish Scriptures as coming from authority, and as bringing before us the personal agency of the Creator, but without purporting to reveal the method of His work,—this is one thing. To argue that no other origin for the first parents of the human race is conceivable than that they were moulded perfect, without the instrumentality of any means,—this is quite another thing. The various hypotheses of Development, of which Darwin's theory is only a new and special version, whether they are probable or not, afford at least a possible escape from the logical puzzle which M. Guizot puts. These hypotheses are indeed destitute of proof; and in the form which they have as yet assumed, it may justly be said that they involve such violations of, or departures from, all that we know of the existing order of things, as to deprive them absolutely of all scientific basis. But the close and mysterious relations between the mere animal frame of Man, and that of the lower animals, does render the idea of a common relationship by descent at least conceiv-

[page] 31

able. Indeed, in proportion as it seems to approach nearer to processes of which we have some knowledge, it is, in a degree, more conceivable than Creation without any process,—of which we have no knowledge and can have no conception.

But whatever may have been the method or process of Creation, it is Creation still. If it were proved to-morrow that the first man was " born " from some pre-existing Form of Life, it would still be true that such a birth must have been, in every sense of the word, a new Creation. It would still be as true that God formed him " out of the dust of the earth," as it is true that He has so formed every child who is now called to answer the first question of all theologies. And we must remember that the language of Scripture nowhere draws, or seems even conscious of, the distinction which modern philosophy draws so sharply between the Natural and the Supernatural. All the operations of Nature are spoken of as operations of the Divine Mind. Creation is the outward embodiment of a Divine Idea. It is in this sense, apparently, that the narrative of Genesis speaks of every plant being

[page] 32

formed "before it grew." But the same language is held, not less decidedly, of every ordinary birth. "Thine eyes did see my substance, yet being imperfect. In Thy book all my members were written which in continuance were fashioned, when as yet there were none of them." And these words, spoken of the individual birth, have been applied not less truly to the modern idea of the Genesis of all Organic Life. Whatever may have been the physical or material relation between its successive forms, the ideal relation has been now clearly recognised, and reduced to scientific definition. All the members of that frame which has received its highest interpretation in Man, had existed, with lower offices assigned to them, in the animals which flourished before Man was born. All theories of Development have been simply attempts to suggest the manner in which, or the physical process by means of which, this ideal continuity of type and pattern has been preserved. But whilst all these suggestions have been in the highest degree uncertain, some of them violently absurd, the one thing which is certain is the fact for

[page] 33

which they endeavour to account. And what is that fact? It is one which belongs to the world of Mind, not to the world of Matter. When Professor Owen tells us, for example, that certain jointed bones in the Whale's paddle are the same bones which in the Mole enable it to burrow, which in the Bat enable it to fly, and in Man constitute his hand with all its wealth of functions, he does not mean that physically and actually they are the same bones, nor that they have the same uses, nor that they ever have been, or ever can be, transferable from one kind of animal to another. He means that in a purely ideal or mental conception of the Plan of all Vertebrate skeletons, these bones occupy the same relative place—relative, that is, not to origin or use, but to the Plan or conception of that skeleton as a whole.

Here the Supermaterial, and in this sense the Supernatural, element,—that is to say, the ideal conformity and unity of conception, is the one unquestionable fact, in which we recognise directly the working of a Mind with which our own has very near relations. Here, as elsewhere,

[page] 34

we see the Natural, in the largest sense, including and embodying the Supernatural ; the Material, including the Supermaterial. No possible theory, whether true or false, in respect to the physical means employed to preserve the correspondence of parts which runs through all Creation can affect the certainty of that mental plan and purpose which alone makes such correspondence intelligible to us, and in which alone it may be said to exist.

It must always be remembered that the two ideas,—that of a Physical Cause and that of a Mental Purpose,—are not antagonistic only the one is larger and more comprehensive than the other. Let us take a case. In many animal frames there are what have been called " silent members—"members which have no reference to the life or use of the animal, but only to the general pattern on which all vertebrate skeletons have been formed. Mr Darwin, when he sees such a member in any animal, concludes with certainty that this animal is the lineal descendant by ordinary generation of some other animal in which that member was not silent but turned to use. Pro-

[page] 35

fessor Owen, taking a larger and wider view, would say, without pretending to explain how its presence is to be accounted for physically, that the silent member has relation to a general purpose or plan which can be traced from the dawn of Life, but which did not receive its full accomplishment until Man was born. This is certain

the other is a theory. The assumed physical cause may be true or false. But in any case the mental purpose and design—the conformity to an abstract idea—this is certain. The relation in which created Forms stand to our own mind, and to our understanding of their Purpose, is the one thing which we can surely know, because it belongs to our own consciousness. It is entirely independent of any belief we may entertain, or any knowledge we may acquire, of the processes employed for the fulfilment of that Purpose.

And yet scientific men sometimes tell us that "we must be very cautious how we ascribe intention to Nature. Things do fit into each other, no doubt, as if they were designed; but all we know about them is that these corre-

[page] 36

spondences exist, and that they seem to be the result of physical laws of development and growth." Very likely; but how these correspondences have arisen, and are daily arising, is not the question, and it is immaterial how that question may be answered. Do those correspondences exist, or do they not? The perception of them by our mind is as much a fact as the sight or touch of the things in which they appear. They may have been produced by growth—they may have been the result of a process of development,—but it is not the less the development of a mental purpose. It is the end subserved that we absolutely know. What alone is doubtful and obscure is precisely that which alone we are told is the legitimate object of our research,—viz., the means by which that end has been attained. Take one instance out of millions. The poison of a deadly snake—let us for a moment consider what this is. It is a secretion of definite chemical properties which have reference, not only—not even mainly—to the organism of the animal in which it is developed, but specially to the organism of another animal which it is

[page] 37

intended to destroy. Some naturalists have a vague sort of notion that, as regards merely mechanical weapons, or organs of attack, they may be developed by use,—that legs may become longer by fast running, teeth sharper and longer by much biting. Be it so: this law of growth, if it exist, is but itself an instrument whereby purpose is fulfilled. But how will this law of growth adjust a poison in one animal with such subtle knowledge of the organisation of another that the deadly virus shall in a few minutes curdle the blood, benumb the nerves, and rush in upon the citadel of life? There is but one explanation—a Mind, having minute and perfect knowledge of the structure of both, has designed the one to be capable of inflicting death upon the other. This mental purpose and resolve is the one thing which our intelligence perceives with direct and intuitive recognition. The method of creation, by means of which this purpose has been carried into effect, is utterly unknown.

Perhaps no illustration more striking of this principle was ever presented than in the curious volume published by Mr Darwin on the " Fer-

[page] 38

tilisation of Orchids."* It appears that the fertilisation of almost all Orchids is dependent on the transport of the pollen from one flower to another by means of insects. It appears, further, that the structure of these flowers is elaborately contrived, so as to secure the certainty and effectiveness of this operation. Mr Darwin's work is devoted to tracing in detail what these contrivances are. To a large extent they are purely mechanical, and can be traced with as much clearness and certainty as the different parts of which a steam-engine is composed. - The complication and ingenuity of these contrivances almost exceed belief. "Moth-traps and spring-guns set on these grounds," might be the motto of the Orchids. There are baits to tempt the nectar loving Lepidoptera, with rich odours exhaled at night, and lustrous colours to shine by day; there are channels of approach along which they are surely guided, so as to compel them to pass by certain spots; there are adhesive plasters

* On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects. By Chas. Darwin, F.R.S. London, 1862.

[page] 39

nicely adjusted to fit their probosces, or to catch their brows; there are hair-triggers carefully set in their necessary path, communicating with explosive shells, which project the pollen-stalks with unerring aim upon their bodies. There are, in short, an infinitude of adjustments, for an idea of which I must refer my readers to Mr Darwin's inimitable powers of observation and description—adjustments all contrived so as to secure the accurate conveyance of the pollen of the one flower to its precise destination in the structure of another.

Now there are two questions which present themselves when we examine such a mechanism as this. The first is, What is the use of the various parts, or their relation to each other with reference to the purpose of the whole? The second question is, How were those parts made, and out of what materials? It is the first of these questions-that is to say, the use, object, intention, or purpose of the different parts of the plant,—which Darwin sets himself instinctively to answer first; and it is this which he does answer with precision and success. The second question,—

[page] 40

that is to say, how those parts came to be developed, and out of what "primordial elements" they have been derived in their present shapes, and converted to their present uses—this is a question which Darwin does also attempt to solve, but the solution of which is in the highest degree difficult and uncertain. It is curious to observe the language which this most advanced disciple of pure naturalism instinctively uses when he has to describe the complicated structure of this curious order of plants. "Caution in ascribing intentions to nature" does not seem to occur to him as possible. Intention is the one thing which he does see, and which, when he does not see, he seeks for diligently until he finds it. He exhausts every form of words and of illustration by which intention or mental purpose can be described. " Contrivance " — "curious contrivance"—"beautiful contrivance,"—these are expressions which recur over and over again. Here is one sentence describing the parts of a particular species; " the Labellum is developed into a long nectary, in order to attract Lepidoptera, and we shall presently give reasons for suspecting that

[page] 41

the nectar is purposely so lodged that it can be sucked only slowly, in order to give time for the curious chemical quality of the viscid matter setting hard and dry." Nor are these words used in any sense different from that in which they are applicable to the works of man's contrivance—to the instruments we use or invent for carrying into effect our own preconceived designs. On the contrary, human instruments are often selected as the aptest illustrations both of the object in view, and of the means taken to effect it. Of one particular structure Mr Darwin says:—"This contrivance of the guiding ridges may be compared to the little instrument sometimes used for guiding a thread into the eye of a needle." Again, referring to the precautions taken to compel the insects to come to the proper spot, in order to have the "pollinia" attached to their bodies, Mr Darwin says:—"Thus we have the rostellum partially closing the mouth of the nectary, like a trap placed in a run for game,—and the trap so complex and perfect!" †But this is not all. The idea of special use, as the

* P. 29. f P. 30.

[page] 42

controlling principle of construction, is so impressed on Mr Darwin's mind, that, in every detail of structure, however singular or obscure, he has absolute faith that in this lies the ultimate explanation. If an organ is largely developed, it is because some special purpose is to be fulfilled. If it is aborted or rudimentary, it is because that purpose is no longer to be subserved. In the case of another species whose structure is very singular, Mr Darwin had great difficulty in discovering how the mechanism was meant to work, so as to effect the purpose. At last he made it out, and of the clue which led to the discovery he says:—"The strange position of the Labellum perched on the summit of the column, ought to have shown me that here was the place for experiment. I ought to have scorned the notion that the Labellum was thus placed for no good purpose. I neglected this plain guide, and for a long time completely failed to understand the flower."

When we come to the second part of Mr Darwin's work, viz., the Homology of the Orchids, we find that the inquiry divides itself into two separate

* P. 262.

[page] 43

questions,-first, the question what all these complicated organs are in their primitive relation to each other; and secondly, how these successive modifications have arisen, so as to fit them for new and changing uses. Now, it is very remarkable that of these two questions, that which may be called the most abstract and transcendental—the most nearly related to the Supernatural and the Supermaterial—is again precisely the one which Darwin is able to solve most clearly. We have already seen how well he solves the first question—What is the use and intention of these various parts? The next question is, What are these parts in their primal order and conception? The answer is, that they are members of a numerical group, having a definite and still traceable order of symmetrical arrangement. They are expressions of a numerical idea, as so many other things—perhaps as all things—of beauty are. Mr Darwin gives a diagram, showing the primordial or archetypal arrangement of Threes within Threes, out of which all the strange and marvellous forms of the Orchids have been developed, and to which, by careful counting and dissection, they can still be ideally

[page] 44

reduced. But when we come to the last question—By what process of natural consequence have these elementary organs of Three within Three been developed into so many various forms of beauty, and made to subserve so many curious and ingenious designs?—we find nothing but the vaguest and most unsatisfactory conjectures. Let us take one instance as an example. There is a Madagascar Orchis—the "Angræcum sesquipedale"—with an immensely long and deep nectary. How did such an extraordinary organ come to be developed? Mr Darwin's explanation is this. The pollen of this flower can only be removed by the proboscis of some very large Moths trying to get at the nectar at the bottom of the vessel. The Moths with the longest probosces would do this most effectually; they would be rewarded for their long noses by getting the most nectar; whilst, on the other hand, the flowers with the deepest nectaries would be the best fertilised by the largest Moths preferring them. Consequently, the deepest-nectaried Orchids, and the longest-nosed Moths, would each confer on the other a great advantage in the "battle of life."

[page] 45

This would tend to their respective perpetuation, and to the constant lengthening of nectaries and of noses. But the passage is so curious and characteristic, that it is well to give Mr Darwin's own words:—

"As certain Moths of Madagascar became larger, through natural selection in relation to their general conditions of life, either in the larval or mature state, or as the proboscis alone was lengthened to obtain honey from the Angrxcum, those individual plants of the Angraecum which had the longest nectaries, (and the nectary varies much in length in some Orchids,) and which, consequently, compelled the Moths to insert their probosces up to the very base, would be the best fertilised. These plants would yield most seed, and the seedlings would generally inherit longer nectaries; and so it would be in successive generations of the plant and Moth. Thus it would appear that there has been a race in gaining length between the nectary of the Angroccum and the proboscis of certain Moths; but the Angrxcum has triumphed, for it flourishes and abounds in the forests of Madagascar, and still troubles each Moth to insert its

[page] 46

proboscis as far as possible in order to drain the last drop of nectar . . . . . We can thus," says Mr Darwin, "partially understand how the astonishing length of the nectary may have been acquired by successive modifications."

It is indeed but a "partial" understanding. How different from the clearness and the certainty with which Mr Darwin is able to explain to us the use and intention of the various organs! or the primal idea of numerical order and arrangement which governs the whole structure of the flower! It is the same through all Nature. Purpose and intention, or ideas of order based on numerical relations, are what meet us at every turn, and are more or less readily recognised by our own intelligence as corresponding to conceptions familiar to our own minds. We know, too, that these purposes and ideas are not our own, but the ideas and purposes of Another—of One whose manifestations are indeed superhuman and supermaterial, but are not " supernatural," in the sense of being strange to Nature, or in violation of it.

The truth is, that there is no such distinction between what we find in Nature, and what we are

[page] 47

called upon to believe in Religion, as that which men pretend to draw between the Natural and the Supernatural. It is a distinction purely artificial, arbitrary, unreal. Nature presents to our intelligence, the more clearly the more we search her, the designs, ideas, and intentions of some

"Living Will that shall endure,

When all that seems shall suffer shock."

Religion presents to us that same Will, not only working equally through the use of means, but using means which are strictly analogous—referable to the same general principles—and which are constantly appealed to as of a sort which we ought to be able to appreciate, because we ourselves are already familiar with the like. Religion makes no call on us to reject that idea, which is the only idea some men can see in Nature—the idea of the universal Reign of Law—the necessity of conforming to it—the limitations which in one aspect it seems to place on the exercise of Will,—the essential basis, in another aspect, which it supplies for all the functions of Volition. On the contrary, the high regions into which this idea is found

[page] 48

extending, and the matters over which it is found prevailing, is one of the deepest mysteries both of Religion and of Nature. We feel sometimes as if we should like to get above this rule—into some secret Presence where its bonds are broken. But no glimpse is ever given us of anything, but " Freedom within the bounds of Law." The Will revealed to us in Religion is not—any more than the Will revealed to us in Nature—a capricious Will, but one with which, in this respect, "there is no variableness, neither shadow of turning."

We return, then, to the point from which we started. M. Guizot's affirmation that belief in the Supernatural is essential to all Religion is true only when it is understood in a special sense. Belief in the existence of a Living Will—of a Personal God—is indeed a requisite condition. Conviction "that He is" must precede the conviction that " He is the rewarder of those that diligently seek Him." But the intellectual yoke involved in the common idea of the Supernatural is a yoke which men impose upon themselves. Obscure thought and confused language are the main source of difficulty.

[page] 49

Assuredly, whatever may be the difficulties of Christianity, this is not one of them,—that it calls on us to believe in any exception to the universal prevalence and power of Law. Its leading facts and doctrines are directly connected with this belief, and directly suggestive of it. The Divine mission of Christ on earth—does not this imply not only the use of means to an end, but some inscrutable necessity that certain means, and these only, should be employed in resisting and overcoming evil? What else is the import of so many passages of Scripture implying that certain conditions were required to bring the Saviour of Man into a given relation with the race He was sent to save? " It behoved Him . . . . to make the Captain of our Salvation perfect through suffering." " It behoved Him in all things to be made like unto His brethren, that He might be," &c.—with the reason added: "for in that He himself hath suffered being tempted, He is able to succour them that are tempted." Whatever more there may be in such passages, they all imply the universal reign of Law in the moral and spiritual, as well as in the material world: that those laws in

[page] 50

had to be—behoved to be—obeyed; and that the results to be obtained are brought about by the adaptation of means to an end, or, as it were, by way of natural consequence from the instrumentality employed. This, however, is an idea which systematic theology generally regards with intense suspicion, though, in fact, all theologies involve it, and build upon it. But then they are very apt to give explanations of that instrumentality which have no counterpart in the material or in the moral world. Perhaps it is not too much to say that the manifest decay which so many creeds and confessions are now suffering, arises mainly from the degree in which at least the popular expositions of them dissociate the doctrines of Christianity from the analogy and course of Nature. There is no such severance in Scripture—no shyness of illustrating Divine things by reference to the Natural. On the contrary, we are perpetually reminded that the laws of the spiritual world are in the highest sense laws of Nature, whose obligation, operation, and effect are all in the constitution and course of things. Hence it is that so much was capable of being conveyed

[page] 51

in the form of parable-the common actions and occurrences of daily life being often chosen as the best vehicle and illustration of the highest spiritual truths. It is not merely, as Jeremy Taylor says, that "all things are full of such resemblances,"—it is more than this—more than resemblance. It is the perpetual recurrence, under infinite varieties of application, of the same rules and principles of Divine government,—of the same Divine thoughts, Divine purposes, Divine affections. Hence it is that no verbal definitions or logical forms can convey religious truth with the fulness or accuracy which belong to narratives taken from Nature—man's nature and life being, of course, included in the term

And so, the Word had breath, and wrought With human hands the Creed of creeds."

The same idea is expressed in the passionate exclamation of Edward Irving:—"We must speak in parables, or we must resent a wry and deceptive form of truth ;f of which choice the first is to be preferred, and our Lord adopted it. Because parable is truth veiled, not truth dismembered

* Tennyson's In Memoriam.

[page] 52

and as the eye of the understanding grows more piercing, the veil is seen through, and the truth stands revealed." Nature is the great Parable; and the truths which she holds within her are veiled, but not dismembered The pretended separation between that which lies within Nature and that which lies beyond Nature is a dismemberment of the truth. Let both those who find it difficult to believe in anything which is "above" the Natural, and those who insist on that belief, first determine how far the Natural extends. Perhaps in going round these marches they will find themselves meeting upon common ground. For, indeed, long before we have searched out all that the Natural includes, there will remain little in the so-called Supernatural which can seem hard of acceptance or belief — nothing which is not rather essential to our understanding of this otherwise "unintelligible world."

[page 53]

CHAPTER II.

LAW;-ITS DEFINITIONS.

THE Reign of Law—is this, then, the reign under which we live? Yes, in a sense it is. There is no denying it. The whole world around us, and the whole world within us, are ruled by Law. Our very spirits are subject to it—those spirits which yet seem so spiritual, so subtle, so free. How often in the darkness do they feel the restraining walls — bounds within which they move—conditions out of which they cannot think! The perception of this is growing in the consciousness of men. It grows with the growth of knowledge; it is the delight, the reward, the goal of Science. From Science it passes into every domain of thought, and invades, amongst others, the Theology of the Church. And so we see the men of Theology coming out to parley with the men of Science,—a white flag in their

[page] 54

hands, and saying, "If you will let us alone, we will do the same by you. Keep to your own province; do not enter ours. The reign of Law which you proclaim, we admit — outside these walls, but not within them.—let there be peace between us." But this will never do. There can be no such treaty dividing the domain of Truth. Every one Truth is connected with every other Truth in this great Universe of God. The connexion may be one of infinite subtlety, and apparent distance—running, as it were, underground for a long way, but always asserting itself at last, somewhere, and at some time. No bargaining, no fencing off the ground—no form of process, will avail to bar this right of way. Blessed right, enforced by blessed power! Every truth, which is truth indeed, is charged with its own consequences, its own analogies, its own suggestions. These will not be kept outside any artificial boundary; they will range over the whole Field of Thought, nor is there any corner of it from which they can be warned away.

And therefore we must cast a sharp eye indeed on every form of words which professes to repre-

[page] 55

sent a scientific truth. If it be really true in one department of thought, the chances are that it will have its bearing on every other. And if it be not true, but erroneous, its effect will be of a corresponding character; for there is a brotherhood of Error as close as the brotherhood of Truth. Therefore, to accept as a truth that which is not a truth, or to fail in distinguishing the sense in which a proposition may be true, from other senses in which it is not true, is an evil having consequences which are indeed incalculable. There are subjects on which one mistake of this kind will poison all the wells of truth, and affect with fatal error the whole circle of our thoughts.

It is against this danger that some men would erect a feeble barrier by defending the position, that Science and Religion may be, and ought to be, kept entirely separate;—that they belong to wholly different spheres of thought, and that the ideas which prevail in the one province have no relation to those which prevail in the other. This is a doctrine offering many temptations to many minds. It is grateful to scientific men who are afraid of being thought hostile to Religion. It is

[page] 56

grateful to religious men who are afraid of being thought to be afraid of Science. To these, and to all who are troubled to reconcile what they have been taught to believe with what they have come to know, this doctrine affords a natural and convenient escape. There is but one objection to it—but that is the fatal objection—that it is not true. The spiritual world and the intellectual world are not separated after this fashion: and the notion that they are so separated does but encourage men to accept in each, ideas which will at last be found to be false in both. The truth is, that there is no branch of human inquiry, however purely physical, which is more than the word "branch" implies;—none which is not connected through endless ramifications with every other,—and especially with that which is the root and centre of them all. If He who formed the mind be one with Him who is the Orderer of all things concerning which that mind is occupied, there can be no end to the points of contact between our different conceptions of them, of Him, and of ourselves.

The instinct which impels us to seek for harmony

[page] 57

in the truths of Science and the truths of Religion, is a higher instinct and a truer one than the disposition which leads us to evade the difficulty by pretending that there is no relation between them. For, after all, it is a pretence and nothing more. No man who thoroughly accepts a principle in the philosophy of Nature which he feels to be inconsistent with a doctrine of Religion, can help having his belief in that doctrine shaken and undermined. We may believe, and we must believe, both in Nature and in Religion, many things which we cannot understand; but we cannot really believe two propositions which are felt to be contradictory. It helps us nothing in such a difficulty, to say that the one proposition belongs to Reason and the other proposition belongs to Faith. The endeavour to reconcile them is a necessity of the mind. We are right in thinking that if they are both indeed true they can be reconciled, and if they really are fundamentally opposed they cannot both be true. That is to say, there must be some error in our manner of conception in one or in the other, or in both. At the very best, each can represent only some partial and imperfect

[page] 58

aspect of the truth. The error may lie in our Theology, or it may lie in what we are pleased to call our Science. It may be that some dogma, derived by tradition from our fathers, is having its hollowness betrayed by that light which sometimes shines upon the ways of God out of a better knowledge of His works. It may be that some proud and rash generalisation of the schools is having its falsehood proved by the violence it does to the deepest instincts of our spiritual nature,—to

"Truths which wake to perish never!

Which neither man nor boy,

Nor all that is at enmity with joy,

Can utterly abolish or destroy."*

Such, for example, is the conclusion to which the language of some scientific men is evidently pointing, that great general Laws inexorable in their operation, and Causes in endless chain of invariable sequence, are the governing powers in Nature, and that they leave no room for any special direction or providential ordering of events. If this be true, it is vain to deny its bearing on Religion. (What, then. can be the use of prayer?

* Ode to Immortality from the Recollections of Early Childhood.—Wordsworth.

[page] 59

Can Laws hear us? Can they change, or can they suspend themselves? These questions cannot but arise, and they require an answer. It is said of a late eminent Professor and clergyman of the English Church, who was deeply imbued with these opinions on the place occupied by Law in the economy of Nature, that he went on, nevertheless, preaching high doctrinal sermons from the pulpit until his death. He did so on the ground that propositions which were contrary to his reason were not necessarily beyond his faith. The inconsistencies of the human mind are indeed unfathomable; and there are men so constituted as honestly to suppose that they can divide themselves into two spiritual beings, one of whom is sceptical, and the other is believing. But such men are rare—happily for Religion, and not less happily for Science. No healthy intellect, no earnest spirit, can rest in such self-betrayal. Accordingly we find many men now facing the consequences to which they have given their intellectual assent, and taking their stand upon the ground that prayer to God has no other value or effect than so far as it may be a good way of preaching to

[page] 60

ourselves. It is a useful and helpful exercise for our own spirits, but it is nothing more. But how can they pray who have come to this? Can it ever be useful or helpful to believe a lie? That which has been threatened as the worst of all spiritual evils, would then become the conscious attitude of our "religion," the habitual condition of our worship. This must be as bad science, as it is bad religion. It is in violation of a Law the highest known to Man—the Law which inseparably connects earnest conviction of the truth in what we do or say, with the very fountains of all intellectual and moral strength. No accession of force can come to us from doing anything in which we disbelieve. Such a doctrine will be indeed

" The little rift within the lute That by and by will make the music mute, And ever widening slowly silence all:'

If there is any helpfulness in Prayer even to the Mind itself, that helpfulness can only be preserved by showing that the belief on which this virtue depends is a rational belief. The very essence of

* Idylls of the King—Vivien.—Tennyson.

[page] 61

that belief is this—that the Divine Mind is accessible to supplication, and that the Divine Will is capable of being moved thereby. No question is, or indeed can be, raised as to the powerful effect exerted by this belief on Man's nature. That effect is recognised as a fact. Its value is admitted; and in order that it may not be lost, the compromise now offered by some philosophers is this—that although the course of external nature is unalterable, yet possibly the phenomena of Mind and character may be changed by the Divine Agency. But will this reasoning bear analysis? Can the distinction it assumes be maintained? Whatever difficulties there may be in reconciling the ideas of Law and of Volition, are difficulties which apply equally to the Worlds of Matter and of Mind. The Mind is as much subject to Law as the Body is, The Reign of Law is over all and if its dominion be really incompatible with the agency of Volition, Human or Divine, then the Mind is as inaccessible to that agency as material things. It would indeed be absurd to affirm that all Prayers are equally rational or equally legitimate. Most true it is that " we know not what we should pray

[page] 62

for as we ought. " Prayer does not require us to believe that anything can be done without the use of means; neither does it require us to believe that anything will be done in violation of the Universal Order. "If it be possible," was the qualification used in the most solemn Prayer ever uttered upon Earth. What are and what are not legitimate objects of supplication, is a question which may well be open. But the question now raised is a wider one than this—even the question whether the very idea of Prayer be not in itself absurd — whether the Reign of Law does not preclude the possibility of Will affecting the successive phenomena either of Matter or of Mind. This is a question lying at the root of our whole conceptions of the Universe, and of all our own powers, both of thinking and of acting. The freedom which is denied to God is not likely to be left to Man. We shall see, accordingly, that precisely the same denials are applied to both.

The conception of Natural Laws—of their place, of their nature, and of their office—which involves us in such questions, and which points to such

[page] 63

conclusions, demands surely a very careful examination at our hands.

What, then, is this Reign of Law? What is Law, and in what sense can it be said to reign ?

Words, which should be the servants of Thought, are too often its masters; and there are very few words which are used more ambiguously, and therefore more injuriously, than the word "Law." It may, indeed be legitimately used in several different senses, because in all cases as applied in Science it is a metaphor, and one which has relation to many different kinds and degrees of likeness in the ideas which are compared. It matters little in which of these senses it is used, provided the distinctions between them are kept clearly in view, and provided we watch against the fallacies which must arise when we pass insensibly from one meaning to another. And here it may be observed, in passing, that the metaphors which are implied in Language are generally founded on analogies instinctively, and often unconsciously, perceived, and which would not be so perceived if they were not both deep and true. "In this case the idea which lies at the root

[page] 64

of Law in all its applications is evident enough. In its primary signification, a "law" is the authoritative expression of human Will enforced by Power. The instincts of mankind finding utterance in their language, have not failed to see that the phenomena of Nature are only really conceivable to us as in like manner the expressions of a Will enforcing itself with Power. But, as in many other cases, the secondary or derivative senses of the word have supplanted the primary signification; and Law is now habitually used by men who deny the analogy on which that use is founded, and to the truth of which it is an abiding witness. It becomes therefore all the more necessary to define the secondary senses with precision. There are at least Five different senses in which Law is habitually used, and these must be carefully distinguished:—

First, We have Law as applied simply to an observed Order of facts.

Secondly, To that Order as involving the action of some Force or Forces, of which nothing more may be known.

[page] 65

Thirdly, As applied to individual Forces the measure of whose operation has been more or less defined or ascertained.

Fourthly, As applied to those combinations of Force which have reference to the fulfilment of Purpose, or the discharge of Function.

Fifthly, As applied to Abstract Conceptions of the mind—not corresponding with any actual phenomena, but deduced therefrom as axioms of thought necessary to our understanding of them. Law, in this sense, is a reduction of the phenomena, not merely to an Order of facts, but to an Order of Thought.

These great leading significations of the word Law all circle round the three great questions which Science asks of Nature, the What, the How, and the Why—

(1) What are the facts in their established Order ?

(2) How — that is, from what physical causes,—does that Order come to be ?

(3) Why have these causes been so combined? What relation do they bear to Purpose, to the fulfilment of Intention, to the discharge of Function?

It is so important that these different senses of

[page] 66

the word Law should be clearly distinguished that each of them must be more fully considered by itself.

The First and, so to speak, the lowest sense in which Law is applied to natural phenomena is that in which it is used to express simply "an observed Order of facts"—that is to say, facts which under the same conditions always follow each other in the same order. In this sense the laws of Nature are simply those facts of Nature which recur according to a rule. It is not necessary to the legitimate 'application of Law in this sense, that the cause of any observed Order of facts should be at all known, or even guessed at. The force or forces to which that Order is due may be hid in total darkness. It is sufficient that the Order or sequence of phenomena be uniform and constant. The neatest and simplest illustration of this, as well as of the other senses in which Law is used, is to be found in the exact sciences, and especially in the history of Astronomy. It is nearly 250 years since Kepler discovered, in respect to the distances, velocities, and orbits of the Planets, three

[page] 67

facts, or rather three series of facts, which, during many years* of intense application to physical inquiry, remained the highest truths known to Man on the phenomena of the Solar System. They were known as the Three Laws of Kepler. It is not necessary to describe in detail here what these laws were. Suffice it to say, that the most remarkable among them were facts of constant numerical relation between the distances of the different Planets from the Sun, and the length of their periodic times, and again, between the velocity of their motion and the space enclosed within certain corresponding sections of their orbit. These Laws were simply and purely an "Order of facts" established by observation, and not connected with any known cause. The Force of which that Order is a necessary result had not then been ascertained. A very large proportion of the laws of every science are laws of this kind and in this sense. For example, in Chemistry the behaviour of different substances towards

* The "Third Law" of Kepler was; made known to the world in 1619. Newton's " Principia" appeared in 1687.

[page] 68

each other, in respect to combination and affinity, is reduced to system under laws of this kind, and of this kind only. Because, although there is a probability that Electric or Galvanic Force is the cause, or one of the causes, of the series of facts exhibited in chemical phenomena, this is as yet no better than a probability, and the laws of Chemistry stand no higher than facts which by observation and experiment are found to follow certain rules.