[title page]

GREATER LONDON:

A NARRATIVE OF

ITS HISTORY, ITS PEOPLE, AND ITS PLACES.

BY

EDWARD WALFORD, M.A.,

JOINT-AUTHOR OF "OLD AND NEW LONDON."

ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS.

VOL. II.

CASSELL & COMPANY, LIMITED:

LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK & MELBOURNE.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

[page] 116

elms, is neatly kept. In it is the monument of Robert Monsey Rolfe, Baron Cranworth, Lord Chancellor of England, who died in 1868. It consists of a flat grey granite tomb, with a large cross of red granite. Among other memorials in the churchyard is a marble slab, on which are recorded the deaths of Francis Hastings Toone, Esq., of Keston Lodge, and of his sister, the Countess of Dysart, and of her son, William Felix Tollemache, Lord Huntingtower.

Near the lodge of Holwood, not far from the church, is a spring of water, called by the traditional name of the Archdeacon's Well. Often during dry seasons this forms the only supply of water for the houses round about, and even the inhabitants of the next village, Downe, are partially dependent on it. Close by the Archdeacon's Well is a spot called Warbank, which bears more than ordinary interest. "The prevalent idea," writes the author of Unwin's "Half-Holiday Handbook," "is that this was the site of an ancient town, and this probability is strengthened by the fact that remains of houses, of bricks, and old pottery, and even human skeletons, have been unearthed. The name Warbank is possibly a corruption of Weard-bank, meaning originally a kind of watch, or look-out station for the use of the Roman army. Mr. Kempe, the antiquarian, made some excavations here a few years since, and he positively asserts that he came upon the foundation of a circular building of flint, having a radius of fifteen feet, and walls of great thickness. Near to this were also discovered the remains of a square structure, which he supposed to be a tomb, as other graves and human bones were found in its immediate vicinity. The fields round Keston Court Farm contain evidences of the existence of a burial-ground, as urns holding the ashes of former inhabitants have been brought to light, showing that the Roman custom of cremation was known and put into practice by the settlers. According to the rude idea of the time, when a person of distinction died his body was cremated, and the ashes buried with such possessions as the deceased was particularly fond of. Coins of various descriptions, that have not seen the light for ages, and bearing the names and effigies of Claudius and Carausius, were also found at this spot. By some antiquarians this was supposed to be the veritable 'Noviomagus' of the Romans, and an archæological society was formed, under the title of the 'Order of Noviomagians,' for the purpose of elucidating its history."

With regard to the etymology of Keston, Ireland, in his "History of Kent," says it was "anciently written Cheston, the sound of the Saxon c being often expressed by the letters ch, having been probably so called quasi Chesterton, that is, the place of the camp, or fortification; but the Britons, pronouncing the c as we do k at this time, it thence assumed its present name of Keston. Some ingenious etymologists have fancied that they have discovered therein something of Cæsar's name, whence they would have it termed quasi Keesar's Town, as the Britons pronounced that name."

The Manor of Keston was originally given by William the Conqueror to his half-brother, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. This prelate, according to Hasted, let it to Gilbert de Maminot, one of William's favourite captains, who provided a thousand men as payment to guard the person of the king. In the reign of Edward III. the manor was held by Sir John de Huntingfield, who paid half a knight's fee for it. Afterwards it passed into the hands of Thomas Squerie, of West Wickham, on whose death without issue his two sisters became his co-heirs, of whom Dorothy, the youngest, married Richard Mervin, and the manor became her husband's. In the reign of Elizabeth, Mr. John Lennard, of Chevening, was its owner, and he settled it on his second son, Samuel, who came to reside at West Wickham. The eldest son of this gentleman was made a baronet in 1642, and dying in 1709, was succeeded by his son. Thus the descent is traced to its present owner, Sir John Farnaby Lennard, who, taking the name of Lennard, has had the title renewed in his favour.

CHAPTER XIII.

FARNBOROUGH AND DOWNE.

Productions of Farnborough—Early History—Tubbendens—Church of St. Giles—Greenstreet Green and Knockholt Beeches—Downe—St. Mary's Church—Charles Robert Darwin—Downe Hall—High Elms—Sir John Lubbock—Cudham and its Church.

THE village of Farnborough, whither we are now directing our steps, lies to the east of Keston, on the high road from London to Sevenoaks and Tonbridge. It is between three and four miles from the Bromley stations of the South Eastern and the London, Chatham, and Dover Railways, and about

[page] 117

two miles from that of Orpington, on the Sevenoaks and Tunbridge line of the South Eastern Railway. The village is called in the Textus Roffensis "Fearnberga." Ireland, in his "History of Kent," says "it most probably took its name from the natural disposition of the soil to bear fearn, or fern, the latter syllable, berge, signifying in old English a little hill—an etymology well suiting the place." It may be observed that the name of Farnborough is not uncommon in other parts of England. There is one near Blackwater, in Hampshire, another in Warwickshire, another in Berkshire, and yet another in Somerset, not far from Bristol.

The parish lies on high ground, and in the north-west parts, towards Hayes and Bromley, is much overgrown with coppice woods. A walk round the village, however, will reveal the fact that we are in the midst of the fruit district. "Out of 1.411 acres, which is the estimated area of the parish," remarks the author of "Unwin's Guide" to the district, "about a quarter is devoted to the cultivation of fruit and vegetables to supply the London markets. Even the hedgerows abound in fruit-trees, particularly the damson, which here grows to perfection; and no prettier sight can be imagined than when these trees are laden with blossoms, and later on with fruit hanging temptingly overhead. A large portion of land is taken up with the culture of potatoes, most of them going to the Borough Market." Some hundreds of acres of strawberries also are grown here for the London markets.

The village of Farnborough in itself possesses little or nothing to interest or attract the tourist; but it is of interest as having given the title of Lord Farnborough to Sir Charles Long, of the neighbouring parish of Bromley, and of whom we have already spoken at some length in our account of that place.* It is a quaint, straggling, irregular village, mostly on the high road. The sign of the "Woodman" marks an old roadside tavern, which may have been a public-house in the days of the Tudors, or earlier. Its red brick chimneys are far out of the perpendicular.

The liberty of the Duchy of Lancaster claims sundry rights over this parish, the manor of Farnborough having belonged to that duchy from its first erection.

In the reign of Henry III. Farnborough appears to have been one of the fees belonging to Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, who fell at the battle of Evesham, fighting on the side of the barons. His estates and honours were seized by the Crown, and were given by the king to his second son, Edmund Plantagenet, Earl of Lancaster, of whom they were held, under Edward I., by the eminent family of the Grandisons, one of whom, in the reign of Edward III., was Bishop of Exeter. In the eighteenth year of that king, Henry, Earl of Lancaster, possessed this manor after the death of his brother Thomas, who had been beheaded at Pomfret. He had been restored to all his titles, and died in 1345. His son Henry, who succeeded to this manor, had been created Earl of Derby, and the property continued in the hands of that royal line till Henry VII., in his first year, broke the entail. The property was in the possession of Charles I. at his death, in 1648. The royal estates being then seized by the Parliament, the Manor of Farnborough, commonly called the Duchy Court of Farnborough, belonging to the Duchy of Lancaster, was, in 1652, surveyed. At the restoration of Charles II., in 1660, this manor again returned to the Crown, and it continued among its revenues, under the jurisdiction of the Duchy Court of Lancaster, without any grant being made of the same, till about the middle of the last century, when the Hon. Thomas Walpole obtained a grant of the property under the seal of the duchy court. The manor has since been held by the Bonds, Copes, and others.

Farnborough Hall, at a short distance to the north-east of the village, is built upon an estate which appears to have been held by Simon de Chelsfield of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, in the reign of Henry III. About the middle of the fourteenth century the property was purchased by the Petleys, from whom it passed by sale to the Peches, and from that family it passed, by the marriage of an heiress, to John Hart. With the descendants of this gentleman the property remained till it was conveyed by marriage to the Dykes of Lullingstone.

Tubbendens is another ancient seat in this district, the demesnes of which lie partly in this parish and partly in that of Orpington. In the twenty-first year of Edward I. it was possessed by owners of the same name, as it appears that "Gilbert Saundre, of Orpington, demised several parcels of land to John de Tubbendens, of Ferneborough, and his sons." According to Hasted, "in 1660 W. Gee conveyed it to Thomas Brome, serjeant-at-law. His arms are in one of the windows of Gray's Inn Hall. He resided at Tubbendens, and died in 1673, and was buried in Farnborough Church. He was succeeded by his son, William Brome, barrister-at-law, whose son, Colonel John Brome,

* See ante, p.94.

[page] 118

succeeded him. Both were buried at Farnborough Church." Colonel John Brome married Elizabeth, only child of the Rev. George Berkeley, Prebendary of Westminster, second son of George, first Earl of Berkeley. Their daughter Maria married a Mr. John Hammond, of Chatham, who, in right of his wife, became the owner of Tubbendens, of which he died possessed in 1774, leaving two daughters, one of whom, Anna Maria, married James Primrose Maxwell, whose grandson, Colonel George Shirley Maxwell, now owns the estate. It will thus be seen that Tubbendens has passed from one generation to another, either in male or female descent, for upwards of 200 years. From an old book, entitled "Stemmata Chicheleyana," it appears that through the Bromes and Berkeleys the present owner of Tubbendens is descended from the father of Archbishop Chicheley, who died in the year 1400.

The present house dates from the seventeenth century, but has of late years been partially rebuilt and modernised. The estate, comprising about 170 acres, has this much of interest attached to it: that it has remained the same in extent for centuries past, except when a small portion was taken by the South Eastern Railway to construct the chalk embankment on which stands the Orpington Station. At the entrance gate of Tubbendens is a milestone over a century old, marking fifteen miles from London Bridge.

Farnborough was till lately a chapelry annexed to Chelsfield, the united living being in the gift of All Souls' College, Oxford, but was constituted a separate parish in 1876. It is in the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the diocese of Canterbury and the deanery of West Dartford. The church, dedicated to St. Giles the Abbot, stands prettily on a steep slope overhanging the road at the south-east end of the village, a little out of the high way, on the road to Downe. It consists of a simple nave and chancel, neatly and plainly "restored." The edifice dates from the early part of the seventeenth century, when, its predecessor having been considerably damaged by a violent storm of wind in December, 1639, it was found necessary to take it down and re-build it. One or two lancet windows in the chancel are all that remains of the original fabric. The windows of the nave and the east window are poor and squareheaded. The font is of Perpendicular date, and handsomely carved in diaper work. The low square tower, of brick and flint, was erected in 1838. The church contains several monuments to the Bromes and other families.

On the chancel floor are some finely-carved monumental slabs of the last century, one of them to a Mr. Meetkerke, Rector of Chelsfield, who died in 1775. On the north wall is a mural tablet bearing the following quaint inscription:—

"Beloved; lamented; Rebecca Floyd, wife of Lieut.-General Floyd; victim of maternal affection: she nursed her fever'd infant in her bosom. One fate attended both.

"One grave contains the mother and the child. Almighty God receive their souls.

"Flavia Floyd died Feb. 1, 1802, aged 4½ years. Rebecca Floyd died Feb. 3, 1802, aged 30 years."

By a Commission of Inquiry, in 1650, it was returned that Farnborough had been a "chapel of ease to Chelsfield, and was already fitly divided: it had only one acre of land, and an old house belonging thereto; the parsonage being, at most, worth only £30 per annum." In 1821 there were only 91 dwellings in the parish of Farnborough, the total number of the inhabitants at that time being 553. According to the last census returns, the population now numbers some 1,200 souls.

About a mile eastward from the village, and at the junction of the high road with that leading northward to Orpington, is the little hamlet of Greenstreet Green, a locality frequented by pleasure parties because of its proximity to the Knockholt Beeches, a favourite resort of holiday-makers during the summer months. This famous clump of trees, standing on a knoll, forms a prominent landmark, and is conspicuous for many miles. Chevening Park, the seat of Lord Stanhope, lies in its immediate vicinity, and will be found full of interest to botanists. Both Knockholt and Chevening, however, lie beyond the limits of our jurisdiction.

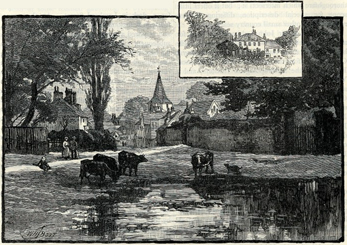

The little village of Downe is situated on a very elevated and salubrious spot, about two miles south by east from Farnborough. The road thither is all "ups and downs," and winds prettily through Sir John Lubbock's park of High Elms. There is also a way to it along pleasant country lanes and field-paths.

The village, for the most part consisting of the cottages of agricultural labourers, is built at the intersection of four cross-roads. It is very pretty and rural, most of its houses clustering round the church, the shingled spire of which peeps out charmingly from the surrounding trees. There are a few houses here and there of a better class, among them being one called the Great House. Trodmore Lodge, formerly called Trowmers, near the church, is a good restored specimen of a Jacobean mansion. It is built of red brick, and has a lofty "prospect tower," which rises as high

[page] 119

above the trees as the neighbouring church spire.

The church, dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin, is a small building, encircled by a belt of elm-trees. It consists of a nave and chancel, and a tower at the west end. The interior and exterior have both been restored on the old lines, but the Early English lancets have been mostly superseded by squareheaded Tudor windows, as at Farnborough and Cudham.

In the churchyard, opposite the south porch, is one of those magnificent yew-trees which are so common throughout this district; the trunk is of enormous growth.

From time to time stained-glass windows have been given by the wealthier members of the congregation, and in 1878 a handsome clock was erected in the tower by public subscription. There are some fine brasses, and around the walls are tablets to various persons connected with the place, and under the nave are deposited the remains of members of the Petley family, who were lords of the manor from the time of Edward III. till Henry VIII. Their mansion has long since disappeared, and the site is now occupied by Petley's Farm. In the chancel is a mural tablet to the late Sir John W. Lubbock. In the south wall of the chancel is a piscina and a double stone seat, beneath a Pointed arch.

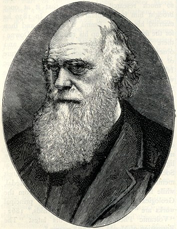

Downe is chiefly notable as having been the residence of one of the most distinguished men of the century, Charles Robert Darwin—remarkable not more for the startling novelty and daring of the theories which he advanced than for the patient industry and scholarly investigation which made his words a power in the land, differ as people may as to the question of their truth or falsity. This is not the place for a discussion respecting the so-called "Darwinian Theory," but a few particulars respecting its originator may not be without interest.

Charles Darwin was born at Shrewsbury on the 12th February, 1809. He came of a distinguished family. His father was the son of Erasmus Darwin, the author of the poem called "The Botanic Garden." His maternal grandfather was the greatest of potters, Josiah Wedgwood. Charles Darwin himself was educated at Shrewsbury School and Christ's College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1831. From the first the young man had shown a strong bent towards the study of natural history, and when Captain Fitzroy offered a berth on board the Beagle on her surveying voyage, to any naturalist who would accept it, Darwin caught eagerly at the offer, unsalaried as the post was. On his return from this voyage of scientific discovery, during which South America and the Pacific Islands were visited, Mr. Darwin published a book containing his observations, which showed so much research and ability that it at once brought him into general notice. In 1839 he married his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and then for the first time took up his residence at Downe; there he devoted himself to experiment and observation, while books such as "The Structure of Coral Reefs" and "Observations on Volcanic Islands" showed the world that he was not idle with his pen. At last, in 1859, the "Origin of Species" burst upon the world, with its bold theories concerning evolution, natural selection, and the like. Instantly a storm of prejudice broke on the author's head.

Undisturbed, he worked on, silently but un-wearyingly, and soon after published "The Descent of Man," dealing specially with such features of the modification of species as may seem to throw light on the origin of man. In 1853 the Royal Society recognised the worth of its greatest member by awarding to him the Royal Medal, while he received the Wollaston Medal from the Geological Society. The rest of his principal works are "The Fertilisation of Orchids," 1862; "Volcanic Phenomena," and his latest "The Formation of Mould by Earth-worms."

Darwin died here on the 19th of April, 1882, at the age of seventy-three. History will doubtless assign to him a foremost place among the scientific writers not only of this country, but of Europe; and though his body lies in Westminster Abbey, his best monument will be that "Origin of Species" which, it has been declared, marks a new epoch in the history of scientific thought. The Daily Telegraph, in recording the death of Darwin, says:—"One scarcely knows which to praise most in this great biologist, his methods or his results. Down to his time naturalists had been chiefly observers and describers. Mr. Darwin was all this, but he was also an experimenter. Let us illustrate his character in these two respects. The philosopher is walking over the pretty downs near Farnham. He sees a few Scotch firs on the hill-tops: they have been there for years; but now some enclosures are made, and very shortly there spring up self-sown firs, in hosts too many to live. 'On looking closely between the stems of the heath,' he says, 'I found a multitude of seedlings and little trees, which had been perpetually bowed down by the cattle. In one square yard I counted thirty-two little trees, and one of them, with twenty-six rings of growth, had, during many years, tried to raise

[page] 120

its head, and failed. No wonder that as soon as the land was enclosed it became thickly clothed with young firs. Yet the heath was extremely

CHARLES DARWIN.

barren. … Here we see cattle absolutely determine the existence of Scotch firs.' Then, again, there was the curious bit of connected natural history showing how the number of old maids in a village might determine the growth of the heartsease or red clover. If there were many ladies with pet cats there would be few field-mice, with few field-mice there would be more red clover, which requires the bees to fertilise it; 'hence we may infer as highly probable that if the whole genus of humble bees became extinct or very rare in England, the heartsease or red clover would become very rare, or wholly disappear.' Facts like these Mr. Darwin has marshalled by the score, and Sir John Lubbock and others, following his example, are daily extending the record. They seem simple, but they are of the utmost importance, as showing the dependence of one part of the economy of nature on another. In this way a school of biologists has been formed who have explained how animals have acquired their forms and characters; how plants have gained the beauty of their forms, the gorgeousness of their colours, and the sweetness of their perfumes; and how by continued sexual selection the male in many species, as the lion or the common fowl, have become strikingly handsome. Whole classes of facts have received explanation which hitherto were enigmas. Mr. Darwin had to meet the objection that the struggle for existence in the animal world seemed insufficient to account for the facts. The following extract shows how he met the argument in the case of the slowest breeding animal:—'There is no exception to the rule that every organic being naturally increases at so high a rate that, if not destroyed, the earth would soon be covered by the progeny of a single pair. Even slow-breeding man has doubled in twenty-five years, and, at this rate, in a few thousand years there would literally not be standing-room for his progeny. Linnæus has calculate that if an animal plant produced two, and so on, then in twenty years there would be 1,000,000 plants. The elephant is reckoned to be the slowest breeder of all known animals, and I have taken some pains to estimate its probable minimum rate of natural increase. It will be under the mark to assume that it breeds under thirty years old, and goes on breeding till ninety years old, bringing forth three pairs of young in this interval; if this be so, at the end of

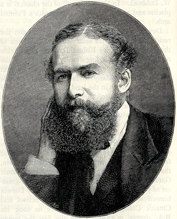

SIR JOHN LUBBOCK.

(From a Photograph by the London Stereoscopic Company.)

the fifth century there would be alive 15,000,000 elephants, descended from the first pair.' Darwin's last communications to the Linnæan Society were

[page] 121

of an experimental character. They were two papers, read only about a month before his death, 'On the Action of Carbonate of Ammonia on the Roots of Plants,' and of the same substance on the chlorophyll of plants. After the publication of his 'Origin of Species,' the author developed his theories in the 'Descent of Man,' 'The Fertilisation of Orchids,' 'The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals,' and 'Movements and Habits of Climbing Plants.' In some of these works there was thought to be a tendency to over-speculation, and the theory that 'man is descended from a

THE VILLAGE OF DOWNE, AND DARWIN'S HOUSE.

hairy quadruped, furnished with a tail and pointed ears, probably arboreal in its habits,' provoked a good deal of easy ridicule. Some of the views of Darwinians, especially the pedigrees of animals, must appear strange till the world becomes familiar with them; but the great merit of the new doctrine is that it has re-created zoology, botany, embryology, and geology, and their kindred sciences. Everything connected with the past and with the future of man and of society is seen to be more or less bound up in the questions of evolution, development, and descent."

Downe Hall, which was for so many years the residence of Darwin, is situated on the south side of the village, about a quarter of a mile from the church. It is an old-fashioned mansion, of no great size; it may be known by its white front, covered with clusters of ivy. On the right hand of the entrance-hall is the new library, which he built for his books, and where, of late years, he read and wrote; on the other side is a smaller apartment, which was used previously as a study, and in which most of his more important works were written. The drawing-room at the back looks out upon a lawn such as many a country rectory possesses, with its mulberry-tree, and its verandah covered with creepers of all sorts and hues. In the further part of the lawn a little grassy mound, carefully railed in, marks the grave of the great naturalist's favourite dog.

The manor of Downe Court, with its site, in the reigns of Edward I. and II., was the property and residence of Richard de Downe. That family became extinct before the middle of the reign of Edward III., when the Petleys of Trowmer, in this parish, became lords of the same. From the Petleys the estate was carried in marriage to the Mannings. It was later on sold to Sir Francis Carew, of Beddington, since which time it had undergone several changes of ownership before coming into Dr. Darwin's hands.

In this neighbourhood has long lived another

[page] 122

distinguished man of science, Sir John Lubbock, whose name has been incidentally mentioned above. His residence, called High Elms, lies to the north of the church, on the road towards Farnborough. It stands in a small park, sweetly undulating and surrounded with trees, among which the beech, the chestnut, and the fir dispute the supremacy with those "elms" which have given to it a name. It crowns a slope overlooking gardens and lawns which gradually die away into the park, the turf being artificially raised so as to conceal the thoroughfare which intersects it; but it offers little scope for special description, differing in few respects from other small country seats.

The name of Sir John Lubbock has been for many years well known in the scientific world. He has been for some time a member of the Royal Commission for the Advancement of Science, President of the Anthropological Institute, and a Vice-President of the Royal Society. He is the author of several learned works, such as "The Origin of Civilisation," "The Origin and Metamorphoses of Insects," and "Pre-historic Times." Max Müller on one occasion wrote of Sir John Lubbock:—"His articles stand almost alone, distinguished alike by sound reasoning and a careful collection of authentic facts. Sir John Lubbock is as honest as a scientific man as he is as a politician. He is not afraid of truth, in whatever shape it comes before him."

It is, however, in the field of pre-historic archæology that Sir John Lubbock has achieved his greatest popular triumphs, having done more, perhaps, than any other archæologist, dead or living, to enlighten the British public on the subject. In the preface to his valuable work, "Pre-historic Times," Sir John quotes, with approval, the noble words of the late Archbishop of Canterbury to the effect that religion and science are really not at variance, and that it is treason to the majesty of both to seek to help either "by swerving ever so little from the straight line of truth." It is elsewhere remarked by Sir John that the "separation of the two mighty agents of improvement (religion and science) is the greatest misfortune of humanity, and has done more than anything else to retard the progress of civilisation."

In 1870 Sir John Lubbock entered Parliament as member for Maidstone, and in 1880 was elected for London University, for which he was again returned in 1885 and 1886. Among the Acts of Parliament with which his name will always be closely associated, are the Bank Holid y Act, the Shop Hours Regulation Act, and the Act for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments.

Amongst its list of "Celebrites at Home," the World of January 1st, 1879, devotes an article to describing Sir John Lubbock at his Kentish residence. "Inheriting mathematical power from his father, he appears to have taken up zoological studies entirely on his own account. His education can hardly be said to have given his taste any bent in that direction. His preliminary instruction over, he was sent to Eton, where his academical career was suddenly cut short by the illness of his father's two partners, which made it necessary that the form at Eton should be exchanged for a desk in Lombard Street. At the age of fourteen he forsook Latin verse-making for accounts, and acquired a sound knowledge of banking. His subsequent education was therefore completed in his leisure hours at High Elms, his recreation being the pursuit of natural history. Early in life he learned to divide his attention, and while given it thoroughly to banking during business hours, to turn it with good effect on literature and science while at home. His natural history work received a great impetus from Mr. Darwin, who came to reside at Downe, and at once took a keen interest in the young investigator. Thus commenced a friendship between two of the most thoughtful and agreeable of men, which has only increased in cordiality with time. In zoology Sir John Lubbock has confined his researches mainly to the lower animals, insects, and crustacea, and made many discoveries concerning their habits and development, embodied in communications to various learned societies. These abstruse studies, however, are of course less known and appreciated by the public than his remarkable observations on the relations of insects and plants. His studies of bee life, habits, and development have contributed greatly to the more perfect understanding of that insect. More recently he has devoted his powers of observation to ants, and has tested their intelligence by a variety of interesting experiments. Mindful that the proper study of mankind is man, Sir John Lubbock has not devoted more than a fair share of his energy and acuteness to the study of the lower animals. Always fond of archæology, he gave that interesting pursuit a wide range by applying the evidence of existing monuments to the elucidation of the habits of primitive mankind. The sum of his work in this direction has been given to the public in "Pre-historic Times" and the "Origin of Civilisation," both of which have passed through several editions, and appear on the shelves of his work-room in French, German, Italian, Danish, Russian, Dutch, and Swedish. His "Origin of Civilisation" has also, it is almost

[page] 123

needless to add, gone through two American editions. The short career of Sir John Lubbock as a politician has been marked by substantial success. Although neither a showy orator nor a brilliant debater, he has succeeded in passing six useful Bills beside that Bank Holiday Bill. How does he contrive to get through this quantity of work? Mainly, he will answer, by beginning early in the morning. At six o'clock he will be found in his work-room preparing for the day by a plunge into the world of science, by writing a paper to be read at some learned gathering, or by making anatomical drawings, an art in which he has acquired considerable skill. Then come breakfast, a drive to the Orpington station, and thence, as swiftly as may be, to Lombard Street. Afterwards follows, according to the season, the House of Commons or home, for the member for Maidstone is a genuine family man."

A mile or more from Downe, through a well-wooded valley, we are met by the arms of the City of London, showing the limits of the Lord Mayor's jurisdiction, and reminding us that we have reached the limits of our letter. Just out of our limits is Cudham, or—as it is called locally—Coodham, with its church prettily perched on the top of an eminence. Its shingled spire is to be seen on every side. A nearer view shows an edifice of the Early English style, with a handsome north aisle to the nave and a south aisle to the chancel. The latter is made to do duty as a vestry, and one of the most beautiful of Decorated windows is blocked up. The nave has been "restored" with painful propriety. At the east end, and in other parts of the church, the Early English lancet windows have been superseded by square-headed insertions of the later Tudor style. The church contains some fine brasses, a piscina, and other objects of interest to antiquarians. In the churchyard are two magnificent yew-trees, which doubtless flourished there at the Conquest.

A little east of the church stands a modern parsonage, most pretentious in its semi-castellated magnificence, and looking as if it had dropped from heaven. The whole place looks as if it were a hundred miles from London.

Downe and Cudham both lie in the midst of: picturesque scenery, but much of the woodlands, which in former times stretched over the greater part of the parish, have within the last few years been converted to agricultural purposes. The route thither from Keston is thus described in Unwin's "Half-Holiday Handbook":—"As we traverse the road, and glance into the valley beneath, a strangely diversified mixture of colours presents itself. The beauty of the various tints contrast; with the arable land, and even in winter time the gradation of colour of the chalk soil from white to a deep brown is very striking. In spring it is even more so, as the young corn and clover, with patches of the farmer's enemy, the yellow charlock, and here and there a newly-ploughed field, form a fine study for the artist; while in autumn the ripe corn gives the appearance of a valley of gold. About a mile along the road from Leaves Green is a cottage known by the appropriate name of the Salt Box, from its being shaped like that article; and opposite this are two lanes—one leading down a steep hill into the valley, the other called Jewer's Hill, offering a shady retreat, where beech-trees grow on either side, their branches meeting overhead, and forming a leafy tunnel. This road leads to Croydon and Chelsham; and should the tourist feel inclined to penetrate its recesses, he will be amply repaid by the rich harvest of wild flowers awaiting him. A pleasant ramble on the chalk hills and slopes in search of these will enable him to pluck specimens of the hoary mullein, that grows here to the height of four or five feet, its yellow flowers clustered round the stem making it a very conspicuous object. The sulphur-coloured blossom of the toad flax, the purple of the foxglove, the sweet aromatic-scented wild thyme, the bladder campion, the pretty yellow cistus, or rock rose, and milkwort, all lend by their gay hues a charm to these chalky slopes. Continuing along the main road beyond the Salt Box Cottage is a small hamlet called Biggin Hill, consisting of a few cottages tenanted by farm-labourers; and on the left the road leads to Cudham village, which is about three miles distant. The route thither lies through fruit plantations, which are in the summer months scenes of great activity, for shoals of the London poor migrate to the locality for the purpose of earning a few shillings by fruit-picking. One is struck with the wild and romantic picturesquesness of the place, and many would scarcely believe such a spot existed so few miles from the metropolis. A few years ago this region was covered with trees, and formed an immense wood; but the suitability of the soil for the growth of fruit was perceived, and a few growers turned their attention to the cultivation of strawberries, many acres of which are now raised. The roots of the trees were grubbed up, and year after year several acres are added by the same process. Most of the crops find their way into the London markets; and when the season is on, long strings of vans, heavily laden, pass through Bromley during the evening, ready for the next morning's market."