[page 759]

A REMINISCENCE OF MR. DARWIN.

EARLY in 1871, while passing a few months in London, it being my good fortune to know Sir Charles Lyell, I, through his introduction, made the personal acquaintance of Mr. Darwin. At that time the state of Mr. Darwin's health was regarded by his family and friends as very delicate; and absorbed as he was in scientific and literary pursuits, he spent most of his time in the retirement of his country home in Kent, and very rarely saw strangers. Under these circumstances I had no reason to expect the pleasure of a personal interview with him. It so happened, however, that, some ten or twelve years before, I had made a long cruise in the South Pacific Ocean, and had visited many of the coral islands of that region. Talking of these islands with Sir Charles Lyell, and expressing something of the deep interest with which I at that time had read Mr. Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle, and especially his studies of coral islands, he was kind enough to say, doubtless in response to a wish of mine, implied if not expressed, that if a favorable occasion offered he would gladly procure for me an opportunity of talking with Darwin himself on the subject. Accordingly, not long after, I received a message from Sir Charles saying that Mr. Darwin, accompanied by some of his family, was spending a few days in town at his brother's house in Queen Anne Street, where he would be pleased to see me at luncheon on the following Sunday. This pleasant invitation was accompanied with a thoughtful warning in a note from Lady Lyell to the effect that although I might find Mr. Darwin looking well and strong, I should remember his really delicate health, and not stay too long.

On my arrival at the door, at the appointed hour, the servant evidently recognized the name of an expected visitor, and took me upstairs at once to a small library room, where I found Darwin alone. He came forward very cordially, putting out his hand in a way to make a stranger feel welcome, and entered directly into conversation in a manner lively enough to relieve any apprehension of his suffering as a great invalid. At that time he was about sixty-two, and he already wore the full gray beard visible in the portraits taken in his later years. We had a little to say about his health, and he spoke of the opinion of some of his friends that its present rather feeble state might be attributed to long-continued seasickness on his voyages years ago; and then said, "So you've been a voyager too?" and asked me in what part of the Pacific Ocean I had been, and what islands I had seen. I thereupon related to him some of my experiences and observations, which led to a pleasant talk on his part about the coral islands. He spoke with great vivacity and interest of his voyage in the Beagle, and especially of his work on coral reefs and atolls, of the wonderful impression that those islands make upon the mind of an observer, and of the charm and poetry they possess in their singular beauty and their peculiar origin and structure.

We were presently joined by two of Mr. Darwin's sons (George, now Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge, England, and Francis, for several years his father's secretary and co-laborer in botanical researches), and soon after went down to luncheon, where we met Miss Darwin, his daughter, Mrs. Darwin's absence being excused on account of illness. In the course of conversation I expressed to Mr. Darwin the regret I had ever since felt that when I went out to the South-sea Islands I was so poorly qualified to observe many of the most interesting features of the places visited, as I had studied very little of natural history, and knew nothing of birds, fishes, corals, shells, or anything of that sort. "Well," said he, "you need not think yourself unique in that respect. I never knew a man who had a rare opportunity for observation who did not regret his imperfect qualifications. It was my own experience. If I could only go now, with my head sixty years old and my body twenty-five, I could do something." Then he said that his visit to the Pacific, or rather his voyage in the Beagle, was the beginning of his scientific career; that he had not before given much serious attention to science, or studied with a definite purpose; that when the Beagle was fitting out he was a young man, fond of sport, shooting and fishing, and with a strong liking for natural history; and it seemed to him a pleasant thing to go as volunteer on the party with his friend Captain Fitzroy. Even after he came

[page] 760

back, he said, it was only after many talks with Lyell, who always heard with interest whatever he had to say, and who urged him to work up and publish his results, that he determined to devote himself to scientific studies.

After a while he spoke of some of his American friends, saying that Mr. Charles Eliot Norton and family had been his neighbors in the country for a time, and that he had enjoyed their society very much. He also mentioned visits which he had received from the younger Agassiz and from Dr. Gray, saying of the latter, "Gray often takes me to task for making hasty generalizations; but the last time he was here talking that way I said to him: 'Now, Gray, I have one more generalization to make, which is not hasty, and that is, the Americans are the most delightful people I know.'"

The conversation having turned upon his last book, The Descent of Man, which had made its first appearance only shortly before, he spoke of the reviews which he had so far seen, saying that most of them were, of course, somewhat superficial, and doubtless others might come later of a different tone, but he had been much impressed by the general assent with which his views had been received. "Twenty years ago," said he, "such ideas would have been thought subversive of everything good, and their author might have been hooted at, but now not only the press, but, from what my friends who go into society say, everybody, is talking about it without being shocked."

"That is true," I said, "but, according to Mr. Punch, while the men seem to accept it without dissent, the women are inclined to protest."

"Ah, has Punch taken me up?" said Mr. Darwin, inquiring further as to the point of the joke, which, when I had told him, seemed to amuse him very much. "I shall get it to-morrow," he said: "I keep all those things. Have you seen me in the Hornet?" As I had not seen the number referred to, he asked one of his sons to fetch the paper from upstairs. It contained a grotesque caricature representing a great gorilla having Darwin's head and face, standing by the trunk of a tree with a club in his hand. Darwin showed it off very pleasantly, saying, slowly and with characteristic criticism, "The head is cleverly done, but the gorilla is bad: too much chest; it couldn't be like that."

The humorists have done much to make Mr. Darwin's features familiar to the public, in pictures not so likely to inspire respect for the author of The Descent of Man as they are to imply his very close relation to some slightly esteemed branches of the ancestry he claims; but probably no one has enjoyed their fun more than he.

Luncheon was already over, and mindful of Lady Lyell's caution, I took an early leave.

To this short narrative I may add the following concerning a subsequent occasion upon which I had the pleasure of seeing Mr. Darwin with his family at their home in Kent. Being again in London in 1878, I was very glad to receive one day about the middle of May a message from Mrs. Darwin inviting me to go down into the country to dine and pass the night at their house in company with one other guest, Colonel T. W. Higginson, of Boston. Leaving town about four or five o'clock in the afternoon, a railway ride of an hour or a little less through one of the most beautiful parts of England brought us to Orpington, from which station we had to make a drive of three or four miles to Darwin's house, near the old and picturesque village of Down. Meeting Mr. George Darwin on the train, we got into a dog-cart which was awaiting us at Orpington station, and drove pleasantly for half an hour through a charming succession of pretty lanes and country roads on our way to Down. The day was showery, and before reaching our destination we got something of a wetting; but the intervals of bright sunshine between the showers lit up a most beautiful landscape, and gave a wonderfully brilliant effect to the foliage, glistening with the freshly fallen rain. The trees, the hedges, the shrubbery, and the grass all seemed on that May day, with alternating sun and shower, to be in a state of absolute perfection. Just before arriving we got a pretty view of Down, and passed within sight of the country-seat of Darwin's friend and fellow-worker in scientific pursuits, Sir John Lubbock.

The dwelling of the Darwin family, as I recall it, is a spacious and substantial old-fashioned house, square in form and plain in style, but pleasing in its comfortable and home-like appearance. The approach seems now to my memory to have been by a long lane, as though the house stood remote from any much-travelled

[page] 761

highway, and without near neighbors, surrounded by trees and shrubbery, and commanding a far-reaching view of green fields and gently undulating country. A portion of the house, the front, has, I believe, been built long enough to be spoken of as old even in England, to which in the rear some modern additions have been made. Entering a broad hall at the front, we passed, on the right, the door of the room the interior of which has since been made known in pictures as "Mr. Darwin's Study"; and a little further on were welcomed immediately by Mr. and Mrs. Darwin to a spacious and cheerful parlor or family room, whose broad windows and outer door opened upon a wide and partly sheltered piazza at the rear of the house, evidently a favorite sitting-place, judging from the comfortable look of easy-chairs assembled there, beyond which was a pleasing vista of fresh green lawn, bright flower beds, and blossoming shrubbery, gravel-paths, and a glass greenhouse, or perhaps botanical laboratory, and, further yet, a garden wall, with a gate leading to pleasant walks in fields beyond. All this one could see standing before the hearth, from which, although past the middle of May, a slowly smouldering fire gave out a pleasant warmth, by no means unwelcome to one whose clothing had been dampened by the brisk shower encountered on the way from the station.

The interior of the room wore a delightfully comfortable and every-day look, with books and pictures in profusion, and a large table in the middle covered with papers, periodicals, and literary miscellany. At a smaller round table, bearing a shaded lamp not yet lit and a work-basket, Mrs. Darwin—a lady of agreeable presence, perhaps eight or ten years younger than her husband (whose cousin she is), and of slightly larger stature than the average English woman of her age—resumed the place from which she had evidently risen to welcome her guests, occupying her hands with some light embroidery or other feminine handiwork, while joining in the general conversation with an occasional remark.

Mr. Darwin sat by the fireside, where he seemed to have been reading. Dressed in an easy-fitting, short, round coat, he looked as though he might have spent the day at work in the garden or laboratory. Though seven years had passed since I had seen him in London, he appeared as well as then and hardly older. We had some pleasant personal chat for a little while, when Colonel Higginson, whose arrival had been delayed, came in, and, soon after, we went to our rooms to dress for dinner, Mr. Darwin himself going on before to show his guests the way, and to see that their needs had been duly provided for.

Re-assembled a half-hour later, we were soon seated at the dinner table, six in all, George and Francis being the only younger members of the family then at home. The dining-room was a handsome, spacious apartment, with windows opening upon the lawn in the rear of the house; its walls hung with pictures, among which I seem to recall some dim, dark portraits of the Darwin ancestry, though nothing, if I remember rightly, more remote than the distinguished grandfather, Dr. Erasmus. Our dinner, though noteworthy for its wholesome simplicity in these days of excessive luxury, was served with care and elegance by two men-servants in livery, the elder butler, a man of advanced years, being evidently of long service in the family. The dinner-table talk was for the greater part light, cheerful, personal; to some extent political, suggested by current events in England and the United States; and touching somewhat upon social reforms, as might indeed be readily imagined in the presence of my distinguished vis-à-vis, Colonel Higginson. To this, however, the way was, perhaps, more directly led by the coincidence of a temperance lecture being given that evening in the public hall at Down, in which good work the family evidently felt some interest; and partly, too, by the experience of Colonel Higginson at the railway station, where he had narrowly escaped being called upon to appear in the rôle of a reformer. The lecturer, it seems, had come down from London by an early evening train, and upon Mr. Francis Darwin had devolved the duty of meeting him at the station, taking him to the hall, and seeing him fairly started upon his praiseworthy mission before returning to join us at dinner. As I now recall the affair, Colonel Higginson, having been delayed in town, had arrived at Orpington station by the same train with the lecturer, and while seeking some means of reaching his further destination, fell in with Mr. Francis Darwin, who, not then knowing him per-

[page 762]

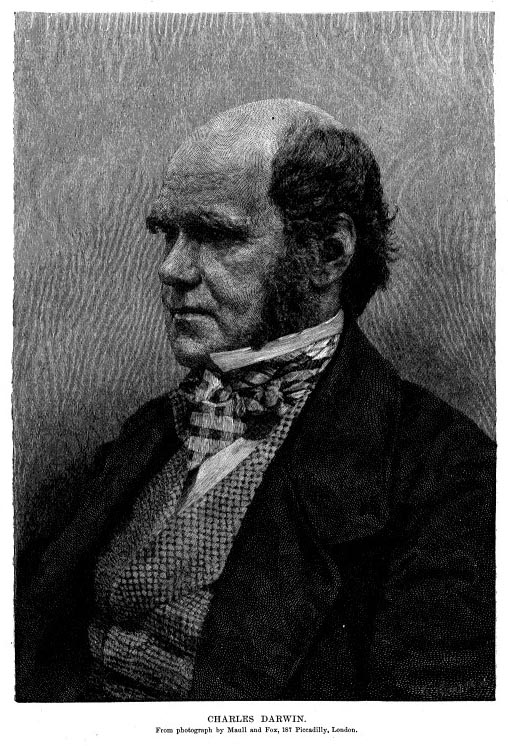

CHARLES DARWIN.

From photograph by Maull and Fox, 187 Picadilly, London.

[page] 763

sonally, and anxiously looking for the lecturer, supposed the colonel was his man, and was about whisking him off to leave him at the public hall when he discovered his mistake. Doubtless the colonel would have graced the platform as well as the dinner table, at which the incident, as he related it, afforded us some amusement.

When Mrs. Darwin rose to leave the gentlemen with their cigars, she reminded her husband that he too must go and take his customary nap. He accordingly withdrew, but about half an hour later rejoined us in the drawing-room, where he remained until half past ten or eleven. During this time he made inquiry for American friends, mostly of Cambridge, but also Marsh, of New Haven. He spoke, too, with particular interest of Mark Twain, from whose writings he had evidently derived much entertainment.

We broke up for the night with the understanding that Colonel Higginson, who had a morning engagement in town, should be called for an earlier breakfast than the rest, and go by a train leaving soon after eight o'clock, while my departure was deferred till noon. Happening to waken early. I dressed and went downstairs soon after seven, but to my surprise Mr. Darwin was there, fresh as a lark, ready to breakfast with the colonel, and speed the parting guest. When he had gone, the later members of the family gathered at their leisure about the breakfast table, while Mr. Darwin disappeared for an hour's work in his study.

During this interval I accepted the invitation of Francis Darwin to go with him for a walk about the grounds, in the course of which we followed some of his father's favorite rambles along shaded paths in a neighboring field, coming back finally to the greenhouse, where some interesting experiments on the revolving movement of plants were at that time in progress. The work of the forenoon was the careful observation of a number of tender shoots that were growing in pots, each under a separate bell glass, and all ranged on a table exposed to the morning sun. To the growing tip of each plant there had been attached by wax or some other adhesive substance one end of a straight piece of very finely drawn glass thread, in such a manner that its other end projected about two inches, horizontally or nearly so, from the point of attachment, where any revolving movement of the stem must be imparted to the glass thread, and cause it to turn like a radial arm from a central point. The ends of the glass thread were made conspicuous by little "blobs" of color, thus giving two easily distinguished points in one straight line. By marking then upon the outer surface of the bell-glass a third point in line with the two "blobs," the subsequent departure of the outer "blob" from that line, caused by the turning of the stem of the plant, very soon became distinctly visible.

At the moment of departure the family gathered at the door, each with a parting word and good wish, and I came away filled with pleasant memories of a charming home and gracious hospitality.