[title page]

JUST BEYOND LONDON

HOME TRAVELLERS' TALES

WITH SOME GLIMPSES OF

RUS-IN-SUB-URBE

BY

GORDON S. MAXWELL

ILLUSTRATED BY

DONALD MAXWELL

"Outside the City walls we found many

wondrous things of which the indwellers

know but little."

Travels of Marco Polo, 1275

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

[page] 104

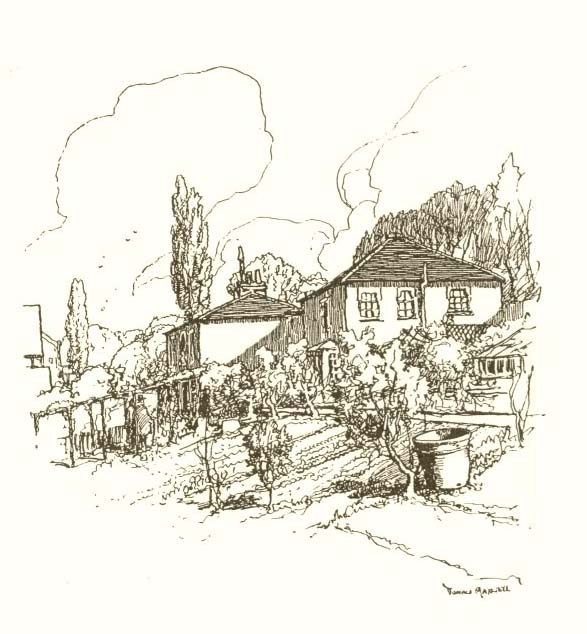

box hedges. The house itself is a small, picturesque, square building, built, I should imagine, some time in the late eighteenth century. In the niche over the front door is a bust of Æsculapius.1 At one side of the house is the Pump-Room, now a small, rather bare little chamber, with a few chairs and tables and a counter behind which is the pump that draws the water from the old well. The room must at one time have been much larger, when the vogue for drinking the waters was the fashion. Even now it could be much improved; for one thing, a few old prints of Streatham Wells in bygone days would add interest to it.

Here, however, we can still sit and sip the Streatham Waters, which I was surprised to find are not half as nasty as I had imagined they would be. Beyond a slightly brackish taste they are not at all unpleasant. The analysis is rather too technical to quote here, but the chief ingredient seems to be sulphate of magnesia impregnated with iron. Of their medicinal value I am not competent to speak, but the list of diseases that these chalybeate waters are said to cure contains some fearsome names.

Not only can the waters be drunk on the spot, but the dairy company who own the place send bottles out, if desired, with the milk, though I presume separately! It is even still exported to all parts of the United Kingdom, and often abroad.

I was given a pamphlet at the wells which sets forth the analysis and diseases in full, together with a picture of the old house and some interesting notes on

1 Æsculapius, or Asclepius, was revered among the Greeks as the God of the Healing Art. The Fountain of Æsculapius in his temple in a grove at Epidaurus was a place of pilgrimage for those in search of health. Homer in the Iliad, however, does not treat him as a divinity, but as the "blameless physician".

[page break]

STREATHAM WELLS

[page] 105

the old Streatham Wells. This pamphlet is, however, a little misleading, for it gives the reader to understand that these wells date from 1659, whereas they date only from the end of the eighteenth century; the original wells were in quite another part of Streatham, of which we shall hear more soon. The spring itself certainly may have been here in 1659, but as a spa it was not used until the closing of the other wells.

"In the early days of the existing spring," writes Arnold, "when it enjoyed the fag-end of the waning popularity of its illustrious predecessor, it is said that the line of carriages almost every day wending their way down to the well in close array was upwards of a mile and a half in length."

In bygone days this well-house must have been a pleasant spot in which to linger, and even now the hill slopes up at the back of it in meadows and woodland, though Valley Road itself is fast becoming suburbanized.

In the Pump-Room I met with a very interesting old man, and we fell into conversation as we drank the waters. He told me he was eighty-seven; he looked twenty years younger, but whether this was due to the rejuvenating properties of the Streatham waters or not is more than I can say. He was very proud of two things; the first was that he had had pluerisy ten times and had been given up by the doctor thirty years ago (this seemed to cause him no small satisfaction, as well it might, for he looked hale and hearty now, despite his years); the second was that he had helped put Darwin in his coffin. "But that would be before you were born," he added, becoming reminiscent, "although I was over middle-age then; and what is more I also helped take him out of it again—which may surprise you."

[page] 106

It did, and to his delight I sought more details, which gave him the chance of repeating an obviously oft-told and rather rambling story about a second undertaker being commissioned unknown to those who had ordered the village builder, with whom my old friend was associated, to make a coffin for the dead scientist. When the second man arrived with his coffin he insisted on the change being made before the Abbey funeral. These rather gruesome details were related at great length and grim satisfaction by the old man. He gave a certain dramatic and mysterious touch his story by his way of telling it, even to describing the fitful moonlight that shone through the trees as they brought the coffin late one night to the house of one whom all the world was mourning, who now lay silent for ever. This occurred at the Kentish village of Downe, where Darwin had spent forty-three years of his life. I happened to know this village and the house in question, and certainly the old man's tale conjured up a vivid mental picture of those rather weird happenings that took place there on that memorable night in the early spring of 1882.

Many other stories of Darwin the told me, whom he knew in life as well as in death, often having worked for him on various building jobs, but the story that intrigued me most was one in which he said that Darwin attributed his good health to his habit of going out into the fields and "inhaling the sheep". These were the old man's exact words, though he couldn't explain exactly how this novel method of healthculture was carried out, but he was unshaken in his assertion that the renowned savant used to practise it daily!

To return to Streatham. After taking the waters I went to inspect the great dairy premises adjoining.

[page] 107

These are owned by Messrs. Curtis Bros. & Dumbrill, one of the big firms forming the Milk Combine. Whether or not we agree with this attempt to form a monopoly of the trade and eliminate competition by seeking to crush the smaller independent man, there is no doubt that this milk "factory" here is the latest thing in efficiency.

It was a great contrast to go from the old-world atmosphere of the Pump-Room to the great building devoted to everything that is the last word in modern methods in the handling of London's milk supply. Everything is mechanical; the human element, except for the guiding of machines, is non-existent. Bottles are filled by a really marvellous contrivance as they pass by on an endless moving platform, another machine puts in the stoppers, another sterilizes and cools the milk, others wash the bottles and churns with steam. The boiler-house and machine-room, where electric power is generated by oil engines, reminded me of the engine-room of an oil-driven warship.

It is all very wonderful and hygienic—almost sternly hygienic, for I'm sure that any germ that was unwary enough even to put its head round the door would die of chagrin!

The stables are worth seeing, especially when the sixty well-groomed horses are "at home", for though the milk-churns are all brought by motor-lorries, it is literal horse-power that delivers the bottles in the neat little red carts. It was quite refreshing to see some parts of this great mechanical organization that were living creatures.

Some people call this a Model Dairy Farm, though I believe the word "farm" is left out of its official title, and rightly so, for wonderful as it all is, it is

[page] 264

Roman soldiers, being badly in need of water when they first camped here, were first attracted to this spring and the little stream that flowed from it by watching a raven that frequently flew down into the bushes; conjecturing that the bird went to drink, the soldiers watched the spot closely and thus discovered its watering-place.

That the Romans called the stream the Raven's bourne (or brook) on account of this incident is humorously absurd, as a little thought will show. To begin with, the Latin for "raven" is corbis, and for "river" flumen, and, anyhow, the Romans are not likely to have suddenly given an English name to the place—yet this story is heard everywhere. I have been told it many times and seen it in various books; even that most interesting volume, Hone's Table Book, has it. It is extraordinary that none of the writers of these books has seen the absurdity of it, for they all mention it in perfectly good faith.

Having upset this tradition, it is, perhaps, only fair to give the correct derivation of the name. It is from ur (Celtic), avon (Saxon) and bourne (Saxon)—all three words, meaning "water" or a "stream", have in the course of centuries become tacked on to it by various dwellers on its banks. This duplication (and triplication) of terms, especially in the case of rivers, is fairly common in the history of English place-names.

The "great house" at Keston is Holwood House, and it is around this (or, to be exact, the predecessor of the existing house) and its beautiful park that the chief interest in the place is centred.

The present Holwood House was built in 1827, and, beyond being a very fine country mansion, has no particular history; but the older house, demolished a few years earlier and standing on a slightly different site, was one of the most interesting in the Home Counties.

[page] 265

In Stanhope's Life we read how William Pitt, the Younger, who, as we have seen, was born at Hayes, once said: "When I was a boy I used to go a-bird-nesting in the wood of Holwood, and it was always my wish to call it my, own." In 1785 this boyish ambition came true, and the great statesman was able to purchase the house and estate. Pitt showed as much ardour for arboriculture at Keston as his father, Lord Chatham, had done at Hayes. Even more—for whereas the father chiefly occupied himself with planting, the son, who certainly also planted, had an equal passion for cutting, as William Wilberforce wrote in his Diary of a visit to Holwood in 1790: "Walked about after breakfast with Pitt and Grenville. We sallied forth armed with billhooks, cutting new walks from one large tree to another, through the thickets of the Holwood copses." Another contemporary writer has also left us a picture of this side of Pitt's life, for in the Diary and Correspondence of the Right Hon. George Rose we read: "Pitt took the greatest delight in his residence at Holwood, which he enlarged and improved (it may truly be said) with his own hands. Often have I seen him working in his woods and gardens with his labourers for whole days together, undergoing considerable bodily fatigue, with so much eagerness and assiduity that you would suppose the cultivation of his villa to be the principal occupation of his life."

Rose also mentions the improvements Pitt made to the house, and adds that the walls of one room were covered with Gilray's and other political cartoons levelled directly against himself. This showed at least a broad-mindedness which was commendable, though I doubt if he exposed any of the unpublished (and unpublishable) cartoons of Gilray, privately printed copies of which are possessed by some col-

[page] 266

lectors. I saw a complete set recently, and was amazed at the disgusting coarseness which in those days apparently passed for wit, judging by the popularity of Gilray's work.

When he bought the house Pitt made many alterations, and in an old engraving of it is to be seen a wing at one side with a semi-octagonal termination, very like the outside of the famous oval library which Pitt also designed for his friend Richard Thornton at Battersea Rise House, which stood, until recently, facing Clapham Common.

"Pitt had an exquisite sense of the beauties of the country," we read in one account of his Kentish home; "he delighted in the prospects of Holwood, ranging as they do over a wide tract of wood and plains of Kent and Surrey, embracing almost all the amenities of the scenery—water excepted—of ourhome counties." To-day this view from the higher parts of the estate is little altered as the eye sweeps over the delightful prospect towards Farnborough and Downe. Both these places are associated with famous men, the former with Lord Avebury (Sir John Lubbock) and the latter with Charles Darwin; and well worth visiting as they are, the temptation to extend our ramble in the itinerary must be resisted till another time.

There is a footpath through the grounds of Holwood Park, by the ladder style I have already mentioned, and a more beautiful or pleasing walk no one could desire. The woods that slope away to the right are approached by a grass sward studded with fine old trees, though to the left the way is barred by a high wire fence. That the owner of the property has not barred the way both sides of the path (which he would be perfectly entitiled to do, though he could not stop the right-of-way) is to his credit, seeing the wanton

[page] 267

damage that is often done to the trees. I was caught red-handed trespassing here, by one of the estate workers, when I was having a look at the house. My courteous "captor" and I sat on a tree-trunk and smoked the pipe of peace together, and talked of the history of the place, in which I was surprised to find he was quite well versed; by no means always the case, as I have often discovered when seeking information from folk in similar positions. It was he who told me of the vandalism that led to the recent erection of the wire fence on the house side of the path; before then, he said, on Bank Holidays people would come and picnic almost in front of the house, leaving behind them the usual litter of paper and bottles. He told me that the owner had no objection to people exploring the woods if they would only have the decency to behave themselves and not damage his property—which struck me as only fair and reasonable, seeing that he had it in his power to close them save for one narrow path.

As I walked along this path I was struck with the wording on the notice boards—not the usual peremptory and meaningless warning to trespassers, but a request that the place should be respected and not damaged. Most of these boards were very old, some almost indecipherable, and my "captor" said that it was because this courteous request had been ignored that the wire fence had been put up—the pearls of courtesy cast before the swine of Bank Holiday bounders!

The most interesting thing—next to the Roman remains—is the old oak-tree that stands by this main path, about a third of the way across the estate. It is a very large tree and is protected by zinc plates and railed round, for it is a tree with a history. This is the famous Pitt's Oak, also sometimes called Wilberforce's Oak or Emancipation Oak. It was

[page] 268

beneath this venerable woodland giant that Pitt and Wilberforce used to sit and discuss the measures to be adopted for the abolition of the slave trade—talks which culminated in the formation of the famous Clapham Sect some dozen or so years later and the passing of the Bill in 1833.

On the stone seat on the opposite side of the path to this tree is carved the inscription:

FROM MR. WILBERFORCE'S DIARY 1788.

AT LENGTH, I WELL REMEMBER, AFTER A

CONVERSATION WITH MR. PITT, IN THE

OPEN AIR JUST AT THE FOOT OF AN

OLD TREE AT HOLWOOD. JUST

ABOVE THE STEEP DESCENT INTO THE

VALE OF KESTON. I RESOLVED TO GIVE

NOTICE ON A FIT OCCASION IN THE

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF MY INTENTION TO

BRING FORWARD THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE

TRADE.

ERECTED BY EARL STANHOPE 1862.

BY PERMISSION OF LORD CRANWORTH.

The Diary of Bishop Wilberforce records a visit to this tree seventy-four year after his father had sat here with Pitt: "Examined the Wilberforce Oak. Saw Mr. Pitt's old carter-boy, now eighty-two, and clear in his remembrance. 'Mr. Pitt,' he said, 'took in from the farm the ground sloping below the oak; he planted all except the old oaks. He used to get his trees from Brompton; I used to go in the cart for them. He was very particular about the planting. He was a very nice sort of man, and would do what anyone asked him in one way or another.'"

So in the shadow of this Tree of Freedom, and in the woods planted by one of England's greatest statesmen, we must bid farewell for a time to one of the most delightful rambling-grounds that lie round London.