[frontispiece]

Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery. London

Charles Darwin

Portrait by John Collier

[page i]

CHARLES

DARWIN

The Man and His Warfare

BY HENSHAW WARD

Author of Evolution for John Doe

The Circus of the Intellect

Exploring the Universe

Illustrated

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET,W.

[page ii]

COPYRIGHT, 1927

BY THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

PHINTED AND BOUND

BY BRAUNWORTH & CO., ING

[page iii]

TO

MAJOR LEONARD DARWIN

AS THE ONLY WAY OF THANKING HIM

FOR HIS KINDNESS IN HELPING ME

[page iv]

[page v]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | WHY DR. GRANT LIKED YOUNG DARWIN | 1 |

| II | WHY YOUNG DARWIN WAS ASTONISHED AT DR. GRANT |

15 |

| III | CAMBRIDGE AND THE BEAGLE | 42 |

| IV | A YEAR WITH FITZ-ROY AND LYELL: 1832 | 65 |

| V | LYELL'S "CREATION" AT CAPE HORN | 93 |

| VI | THE SECOND YEAR IN SOUTH AMERICA | 109 |

| VII | THE THIRD AND FOURTH YEARS IN SOUTH AMERICA | 137 |

| VIII | SIX YEARS OF CORAL ISLANDS AND SPECIES | 177 |

| IX | FOUR YEARS OF SPECIES AT DOWNE | 216 |

| 1. Downe House | 216 | |

| 2. Joseph Dalton Hooker | 219 | |

| 3. The Sketch of 1844 | 223 | |

| 4. Vestiges of Creation | 229 | |

| X | EIGHT YEARS OF BARNACLES: 1846–1854 | 233 |

| 1.Thomas Henry Huxley | 239 | |

| 2. Hooker in India | 248 | |

| 3. Darwin's Poor Health | 253 | |

| 4. The Death of Annie | 254 | |

| 5. Darwin Stood All Alone | 258 | |

| XI | WRITING THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES: 1855–1859 | 264 |

| 1. The Preparation for Writing | 264 | |

| 2. Asa Gray | 274 | |

| 3. Owen's Hostility to Huxley | 280 | |

| 4. Alfred Russel Wallace | 281 | |

| 5. Completing the Origin | 291 | |

| XII | THE RECEPTION OF THE ORIGIN: 1859–1870 | 294 |

| XIII | THE BOOKS AFTER THE ORIGIN: 1860–1881 | 331 |

| 1. Revisions of the Origin | 331 | |

| 2. Darwin Never Became Lamarckian | 332 | |

| 3. The Fertilization of Orchids | 341 |

[page vi]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| 4. | The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication | 345 | |

| 5. | The Descent of Man | 350 | |

| 6. | The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals | 355 | |

| 7. | Insectivorous Plants | 357 | |

| 8. | Three More Botanical Books: 1876–1880 | 358 | |

| 9. | The Formation of Vegetable Mould | 364 | |

| XIV | DARWIN'S LIFE AFTER 1850 | 368 | |

| 1. | The Home Life at Downe | 368 | |

| 2. | Darwin as a Mere Human Being after 1851 | 383 | |

| APPENDIX | ||

| SECTION | PAGE | |

| 1 | BUFFON | 407 |

| 2 | ERASMUS DARWIN | 413 |

| 3 | LAMARCK | 425 |

| 4 | LYELL WAS NOT AN EVOLUTIONIST | 433 |

| 5 | WITNESSES FOR NATURAL SELECTION | 446 |

| 6 | DARWIN DID NOT BECOME A LAMARCKIAN | 448 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 453 | |

| INDEX | 459 | |

[page vii]

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

| CHARLES DARWIN, PORTRAIT BY JOHN COLLIER | FRONTISPIECE |

| FACING PAGE | |

| THE SHREWSBURY SCHOOL | 4 |

| "THE MOUNT" | 12 |

| GEORGES LOUIS LECLERQ, COMTE DE BUFFON | 24 |

| ERASMUS DARWIN, M.D. | 32 |

| PORTRAIT OF LAMARCK | 40 |

| CHARLES DARWIN AND HIS SISTER CATHERINE | 46 |

| SIR CHARLES LYELL, BART. | 70 |

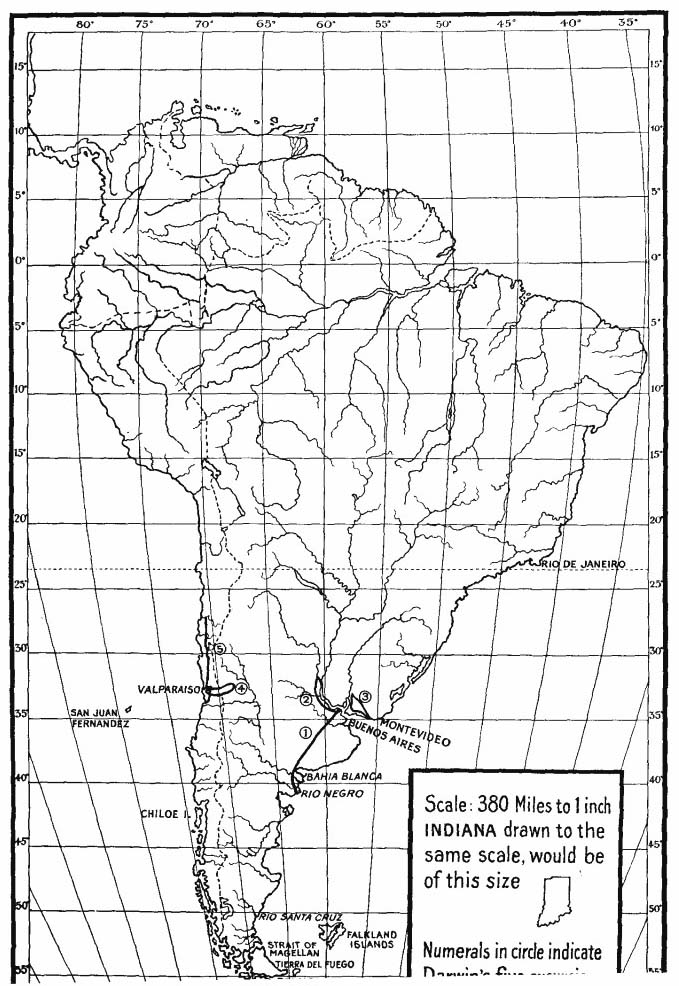

| MAP OF SOUTH AMERICA | 110 |

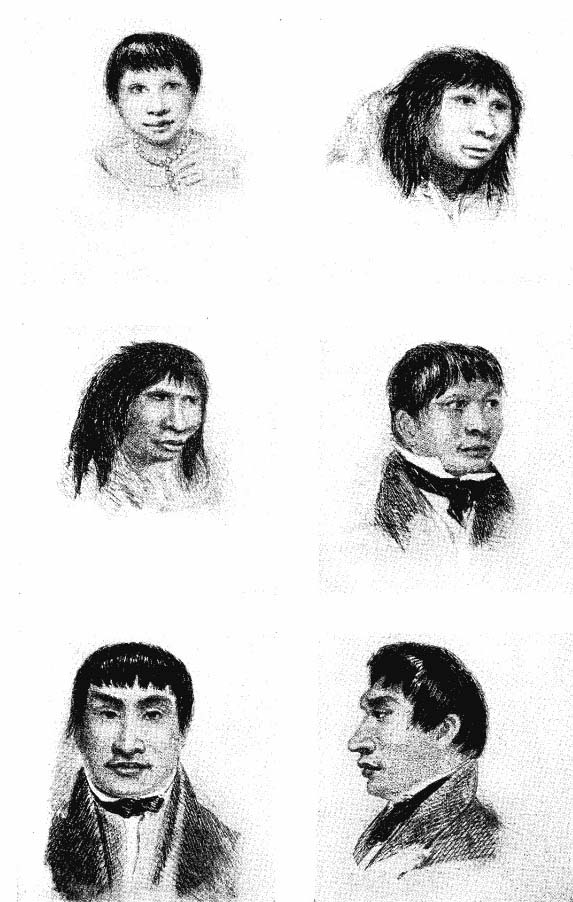

| THE THREE FUEGIANS | 114 |

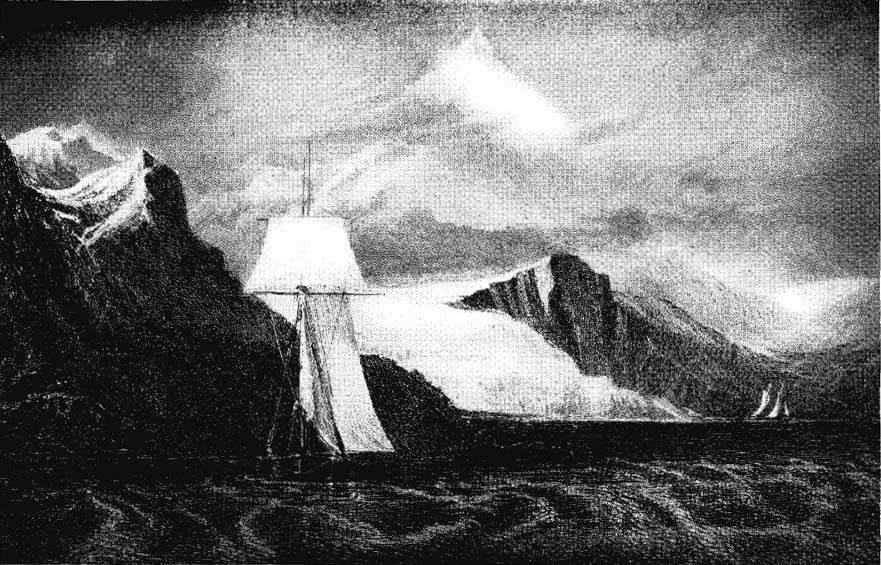

| MOUNT SARMIENTO | 120 |

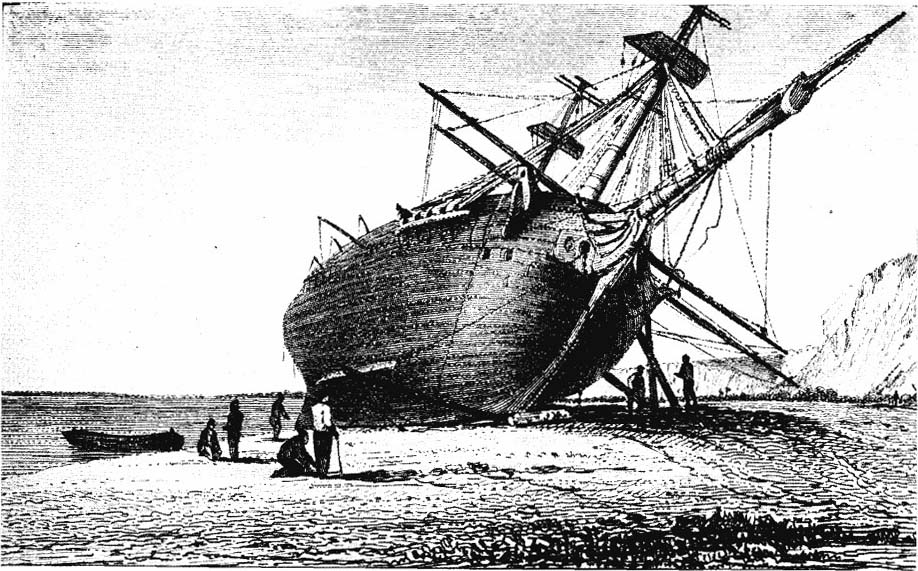

| BEAGLE LAID ASHORE | 138 |

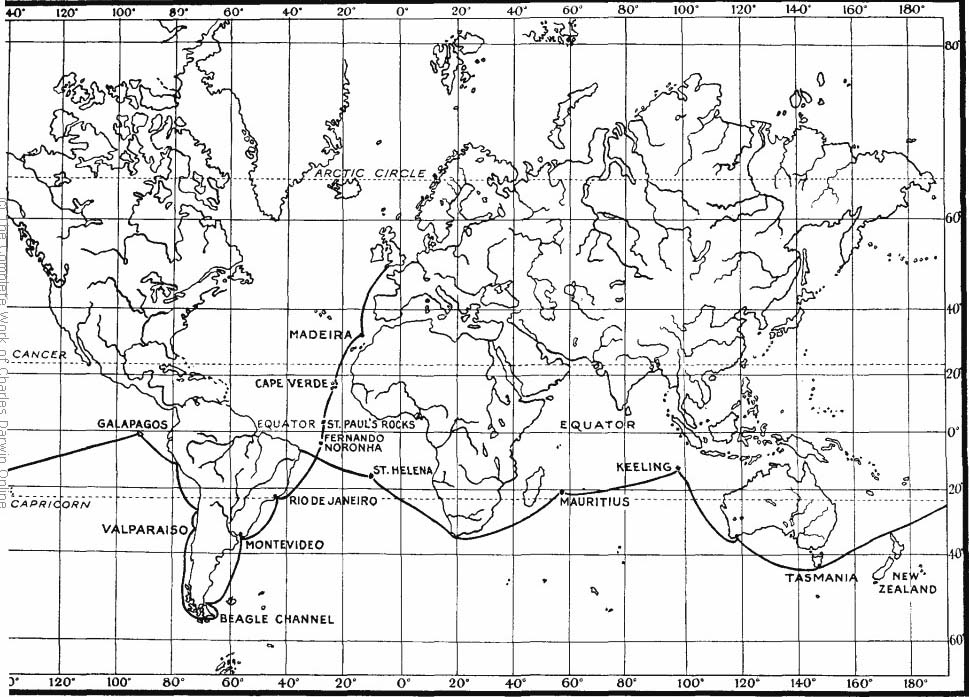

| THE COURSE OF THE BEAGLE ROUND THE WORLD | 178 |

| EMMA WEDGWOOD | 194 |

| SIR JOSEPH DALTON HOOKER | 208 |

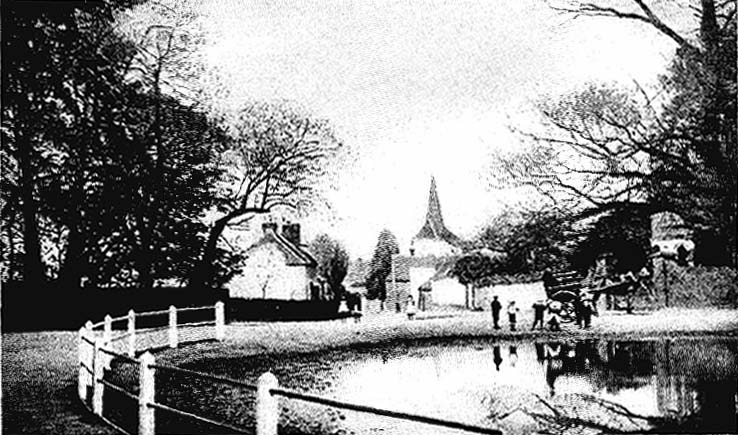

| THE VILLAGE OF DOWNE | 218 |

| THE HOUSE AT DOWNE | 228 |

| THOMAS HENRY HUXLEY | 242 |

| DR. ROBERT WARING DARWIN | 254 |

| CHARLES DARWIN, ABOUT 1854 | 262 |

| ASA GRAY | 276 |

| ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE | 290 |

| CHARLES DARWIN TAKEN VERY LATE IN LIFE | 332 |

| STATUE OF DARWIN IN SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM | 358 |

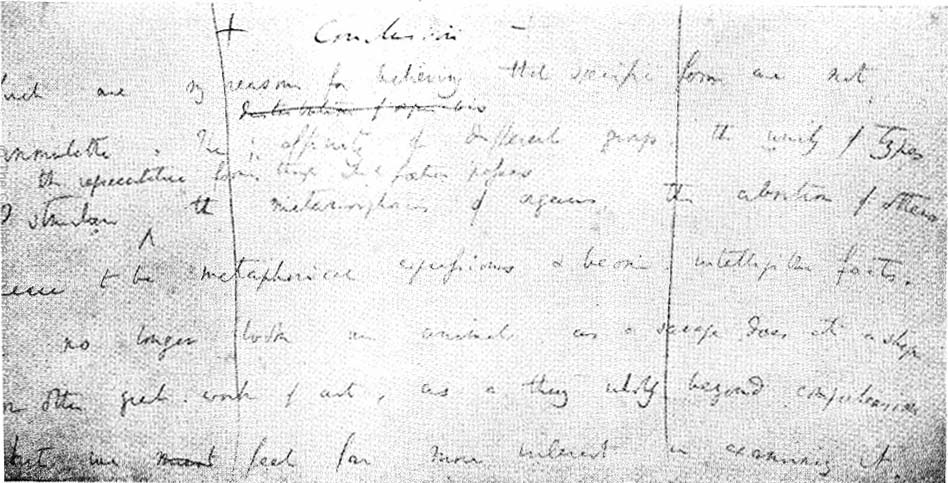

| FACSIMILE OF SEVEN LINES OF THE SKETCH OF 1842 | 366 |

| DARWIN'S STUDY AT DOWNE | 374 |

| MRS. CHARLES DARWIN | 384 |

[page viii]

[page] 1

CHARLES DARWIN

CHAPTER I

WHY DR. GRANT LIKED YOUNG DARWIN

"DR. GRANT one day, when we were walking together, burst forth in high admiration of Lamarck and his views on evolution. I listened in silent astonishment." So Charles Darwin reports an episode in Edinburgh while he was studying medicine there. The greatest puzzle that ever science grappled with was Dr. Grant's subject—what is a species? He favored the brilliant new theory of Lamarck, but young Darwin was so astonished at this judgment that, for fear of seeming disrespectful, he remained silent. It is doubtful whether any famous man ever reported so ironical a story about his youth, or indicated in so few words the result of a lifetime's potent labor. For it was to be his fate to make Lamarck's theory credible and thus revolutionize the ways of human thought.

It is easy to see why he remained silent, even though he thought the Lamarckian views preposterous; for he was only sixteen years old, had been trained for seven years in a famous school to be respectful to his betters, had no fondness for controversy, and was ignorant of all science. Whereas Dr. Grant was an adept in science, thirty-two years old, who had heard Lamarck lecture at Paris, had attended many Continental universities, and had during the past five years studied marine life on the coasts of Scotland and Ireland; he had lectured at the

1

[page] 2

University of Edinburgh, and was now publishing monographs to prove that sponges are animals. He was giving to the world new ideas about animal life, quite sound ideas, which, as the biologists later admitted, "marked a notable advance in knowledge." What was more important, in this comradeship with a boy, was that "he had much enthusiasm beneath his outer crust." Small wonder that the sixteen-year-old Darwin kept silent.

Why the boy should have been astonished is harder to guess. Perhaps his family pride was involved, because he had reason to think that his grandfather's idea had been stolen by Lamarck. More likely he had been used to hearing that the Lamarckian view of evolution was bad form scientifically—nothing but a French fancy. The reasons for young Darwin's astonishment will be unfolded in due time. Just now it is more important to know why the "dry and formal" Dr. Grant has chosen to be walking with a medical freshman and expatiating to him about a matter of biological philosophy. There was a very good reason. It is the key to Darwin's life and to the influence of Darwin's work.

Charles Robert Darwin, who never used his middle name, was born in the ancient town of Shrewsbury on the very same day that Abraham Lincoln was born—February 12, 1809. He was the fifth of the six children of Dr. Robert Waring Darwin, whose skill as a physician had made him well-to-do and highly respected. Dr. Darwin was six feet and two inches in height, and weighed nearly three hundred and fifty pounds. He was a rapid and copious talker. He kept his household orderly and punctual, and had an uncanny instinct for diagnosing what was going on in people's minds and bodies. He was a very affectionate man who inspired th devotion of his children. "When Charles said that his father thought or did so and so." (his cousin Emma Wedgwood testified)

[page] 3

"we all knew that there could be no further question in the matter; what his father did or thought was for him absolutely true, right, and wise." Emma never felt quite at ease in the Doctor's presence, but she confessed that he was extremely kind of her and that she was fond of him. Even when she once remarked sharply in a letter that "one gets rather fatigued by the Dr. 's talk, especially the two whole hours just before dinner," she admitted in the next sentence that "the Dr. has been as pleasant as possible, and I never saw him enjoy anything so much as Susan's account of all her gaieties." (It appears that Susan, Charles's sister, six years older than he, had been brought home from a ball in the chariot of the very tipsy young Sir Watkin, and that "it was rather a tight squeeze," and that Susan had to sit at the bottom of the chariot.) So Dr. Darwin could hardly have been a kill-joy even for an Emma who was used to a very gay life at home. Charles never ceased to honor and love him. In a letter to a friend, telling of the father's death, Charles wrote: "No one who did not know him would believe that a man above eighty-three years old could have retained so tender and affectionate a disposition, with all his sagacity unclouded to the last." The boy who felt such skeptical astonishment toward an accomplished zoologist had a reverence for his father that was called "boundless and most touching."

Charles had hardly any recollection of his mother, for she died when he was only eight years old. She was Susannah Wedgwood, a daughter of the Josiah Wedgwood who is credited with being "the most successful and original potter the world has even seen, whose skill influenced the whole subsequent course of pottery manufacture." She is described as having "a remarkably sweet and happy face, a gentle and sympathetic nature."

[page] 4

The motherless family lived in a large, homey, well-lighted brick house, surrounded by pleasant trees and well-planted shrubbery, on the steep bank of the Severn River, just west of the town. At this point in its course the Severn, a swift stream fifty yards wide, is describing a loop, circling round a knob of land which is threefourths of a mile in diameter, and returning so nearly upon itself as to leave the neck of the knob only three hundred yards in width. The river, forming thus a moat around a rocky hill, created a natural fortress where the ancient Britons withstood the Romans, and which the later English kings used as an important post on the Welsh marches. The town of Shrewsbury is within this loop of the Severn; its streets mount steeply from the river to the summit of the hill; its suburbs are reached by four bridges; the bridge on the northwest leads to Frank-well, where Dr. Darwin's house still stands and is still called "The Mount."

At the age of nine Charles was sent to the Shrewsbury School, then more than two hundred and fifty years old and housed in a building two hundred years old. He was a boarder, but was free to run home during intervals between roll-calls. Often he lingered so long at home that he had to run to be on time for a locking-up. "From being a fleet runner," he says in his autobiography, "I was generally successful in being on time; but when in doubt I prayed earnestly to God to help me, and I well remember that I attributed my success to the prayers, and marveled how generally I was aided." In his run to the school he went three hundred yards east to the Welsh Bridge, crossed this into the town, panted up the hill six hundred yards, and then raced three hundred yards down-hill toward the old Castle that guarded the neck of the peninsula. A hundred yards short of this he turned into the school yard and scuttled up the path beside which he now

[page break]

The Shrewsbury School, now a library, with Darwin's statue in front of the entrance

[page break]

[page] 5

sits in bronze—a severe figure of a man with a long beard meditating upon his boyish hurry.

For seven years at this school he continued to recite Latin and Greek, Latin and Greek, Latin and Greek. The standard of scholarship was kept as high as that of any school in England by the headmaster, the Rev. Samuel Butler, a canon of Lichfield Cathedral, who had been headmaster for twenty years. When he was an undergraduate at Cambridge he had won two medals for composing Greek odes, and would have won a third if he had not been in competition with the poet Coleridge. Yet in spite of these and other classical honors by which he had been distinguished, the boys of the school were still tittering at him when Charles Darwin entered in 1818; for his edition of Æschylus had been severely criticized by the Edinburgh Review. Another reason for gibing at the headmaster was that the only subject he would tolerate in the curriculum except classics and a bit of history was geography. Geography was thus favored because Mr. Butler had written the textbook and liked the royalties—so, at any rete, the merciless boys believed.

"Nothing could have been worse for the development of my mind," Darwin testified late in life, "than Dr. Butler's school. The school as a means of education to me was simply a blank." Yet he worked conscientiously, not using a crib. "The sole pleasure I ever received from such studies was from some of the odes of Horace, which I admired greatly." He was rated by all the masters as rather below the average in mental power.

Charles was yearning for something besides memory work. He took private lessons in geometry because he had "a keen pleasure in understanding any complex subject." He worked eagerly with his older brother at chemistry experiments in a tool-house at home, reading several books, and learning how to make "all the gases."

[page] 6

Such an occupation seemed ridiculous to his school mates, who nicknamed him "Gas"; and it seemed positively immoral to Mr. Butler, who reprimanded him for wasting his time, calling him, in the presence of the whole school, a poco curante. "As I did not understand what he meant," says Darwin, "it seemed to me a fearful reproach."

The epithet has been a boomerang in the Butler family. Charles Darwin, to be sure, was one who cared little about quantities in machine-made verses; but the headmaster has written himself down for posterity as one who cared not at all for the mysteries of the universe in which he lived. He was blind and deaf and unfeeling in the midst of the marvels which all sensitive minds of the period were puzzling about. And this curse of the blindness of a good intellect was transmitted to his grandson, Samuel Butler, author of Erewhon, who has written a book a captivating scholarship, Evolution Old and New, to reprimand Charles Darwin once more for being something much worse than a poco curante. Any one who has an inkling of the Darwinian theory can only read the book with silent astonishment. Perhaps the Darwin statue in front of the Shrewsbury School is meditating upon the sense of values that runs in the Butler family.

Charles had a passion for collecting during his years of schooling. At the age of ten he observed that some moths and a tiger beetle on the Welsh coast were different from any kinds seen about his native town, and he was doubtless itching to capture them. But, after consulting with his sister, he decided that it was not right to kill insects for the mere pleasure of possessing their corpses. Another equally moral resolution was that not more than one egg should ever be taken from a nest for his collection. So fascinating did he find the observing of the habits of birds that he wondered why every gen-

[page] 7

tleman did not become an ornithologist. His fondness for specimens extended to minerals, which he enjoyed decorating with learned names; and he had a desire to know something about every pebble in front of the hall door.

At this early period of boyhood he was somewhat of a sportsman, though his tenderness of heart was a handicap. For example, after he had learned how to kill angleworms painlessly, he quit spitting them alive on his fishhook, resigning himself with magnanimity to poorer catches of fish. The same tenderness of heart caused him lifelong remorse for once beating a puppy "simply [as he self-accusingly thought] from enjoying the sense of power." In old age he still remembered with contrition the exact spot where he committed this atrocious deed when he was eight years old. However, he got some consolation from the fact that the beating was not severe enough to make the puppy howl, and from the knowledge that all the rest of his life he was an adept at stealing the affections of dogs.

Of course his pure chivalry toward animals was corrupted later in his youth by the ignoble customs of the society about him. He learned to rejoice in killing insects. He acquired a passion for killing birds. "I do not believe that anyone could have shown more zeal for the most holy cause than I did for shooting birds. How well I remember killing my first snipe, and my excitement was so great that I had much difficulty in reloading my gun from the trembling of my hands."

Indeed the love of sportsmanship so grew upon him and so occupied his time that even the affectionate father was moved to angry despair. "You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching," he declared to his son, "and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family." Darwin's gentle resentment at the scolding is as

[page] 8

follows: "But my father, who was the kindest man I ever knew and whose memory I love with all my heart, must have been angry and somewhat unjust when he used such words." Probably he was no more than "somewhat" unfair. There must have been some justice in the combined judgment of father and headmaster that Charles cared little or nothing for what seemed to his elders the serious concerns of life.

Perhaps they judged that even his reading was frivolous. It is true that he read the two thick volumes of his grandfather's Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life, a book written to furnish physicians with a general perspective of biology and with concrete advice for their practice. But perhaps Charles read it out of mere curiosity or family pride. He was too fond of mere time-wasting with poetry like Thomson's Seasons or the recently published works of Byron and Scott. He confesses that he "used to sit for hours reading the historical plays of Shakespeare, generally in an old window in the thick walls of the school." Surely it might be only idle pleasure which would lead a Shrewsbury boy to read, in the Shrewsbury School, about Falstaff fighting a long hour by the Shrewsbury clock. Even when he read The Wonders of the World he did not seem to be caring for the information he might amass from it. No. He liked to doubt the truth of its statements and to dream of traveling in far countries where he might see for himself what the wonders were and by what laws they operated. How could a father and a headmaster know that he was not a poco curante?

But the father took heart in the summer of 1825, for the boy agreed to go to Edinburgh to study medicine and prepare himself to uphold in the third generation the professional reputation of his family. He showed some real zest for the profession. During the vacation he gravely

[page] 9

"attended" some poor people, keeping a record of their symptoms, consulting with his father about them, and gravely compounding the prescriptions that his father recommended. So well did he deport himself that Dr. Darwin predicted that his son would be a successful practitioner. And Dr. Darwin was seldom in error when he judged people's capacities. The son never knew a reason for the father's faith, but presumably it was this: Dr. Darwin's own success was due to "a sharpness of observation that enabled him to predict the course of an illness," and this quick, shrewd faculty of observation was possessed by Charles. It was the chief element in his scientific career.

So there was high hope at The Mount when, in October, 1825, Charles took coach for the three-hundred-mile ride to Edinburgh, where his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, had become an M. D. seventy years before. The grandfather, also, had had the sharpness of observation in a high degree; he "intuitively recognized disposition or character and ever read the thoughts of those with whom he came into contact with extraordinary acuteness." And the grandfather was a daring speculator about the nature of life, and how an organism is generated from its parents, and what the ancestry of all life has been. Such speculations as the Lamarckian views on evolution were no novelty in the brain of this boy who was to enjoy a week of stage-coaching to the capital of Scotland.

But it is doubtful whether biology and philosophy occupied his thoughts as the coach rattled northward from Shrewsbury. More likely he was thinking of a certain Emma Wedgwood, whose home was thirty miles to the northeast. History contains no record of how young Darwin felt about her in October of 1825, and speculations about a sweetheart should not be allowed to intrude

[page] 10

into the severe account of a scientific war about species. But she was to play a very important part in the war, and well deserves, just as a matter of scientific history, more space than the two following paragraphs.

She was a very good-looking, healthy, original, and much loved girl, the youngest of the eight children of the younger Josiah Wedgwood, who continued his famous father's business of making pottery. Her father and Charles Darwin's mother were brother and sister. The house in which she lived was a large stone structure more than two hundred years old, situated near the border of a small lake, a "mere." The estate had therefore been named Maer, by adopting a supposedly Saxon spelling. The mere had been extended and beautified by a landscape gardener; there were fish in it and a rowboat on it; in winter it furnised a skating-place for the children. On the slope between it and the house was a lavish series of flower beds. The house was a focus of social doings for the relatives and friends in the whole countryside—the Tolletts, the Caldwells, several families of Wedgwoods, and the Darwins. Emma's mother wrote to a sister in October, 1824: "These young things have kept me in such a whirl of noise, and ins and outs, that I have not found any leisure. I may say to you under the rose that a little calm will be agreeable.… We are just now very flirtish, very noisy, very merry, and very foolish.… Last night they performed some scenes in the 'Merry Wives of Windsor.'… Master Shallow, Emma, very good." Emma's diary record of this period (two weeks after she had been confirmed) was as follows: "1st Oct., Revels; 2nd, Revels; 4th, Revels; 5th, Acted some of Merry Wives; 6th, Oct., quiet evening."

Emma was likely to be very good at whatever she undertook. At school in London, the year before, she had been one of the show performers on the piano. When she

[page] 11

returned to Maer she composed "four delightful little stories written in simple words, and had them printed for use with her Sunday-school class." She was a clever hair-dresser for her older sisters when they were preparing for a ball. She made good use of a nine-month tour in Europe, "enlarging her sympathy and outlook." From this tour she had returned on the first of October, so that Charles Darwin had a chance to welcome her home and to say good-by before setting out for Edinburgh. He always liked to go to Maer. It was a flirtish place.

But there is no record of what girl he was thinking about as he sat in the coach with his brother Erasmus, five years his senior, bound for Edinburgh, rolling along between hills that were covered with autumn brown.

He dutifully wrote home on the Sunday after this arrival:

My dear Father,

As I suppose Erasmus has given all the particulars of the journey, I will say no more about it, except that altogether it has cost me seven pounds. We got into our lodgings yesterday evening, which are very comfortable and near the College.… The terms are £1-6 s for two very nice and light bedrooms and a sitting-room; by the the way, light bedrooms are very scarce articles in Edinburgh, since most of them are little holes in which there is neither air nor light. We called on Dr. Hanley the first morning, whom I think we never should have found, had it not been for a good-natured Dr. of Divinity who took us into his library and showed us a map, and gave us directions how to find him.… I should think Dr. Butler or any other fat English Divine would take two utter strangers into his library and show them the way! … Bridge Street is the most extraordinary thing I ever saw, and when we first looked over the sides, we could hardly believe our eyes, when instead of a fine river, we saw a stream of people. We spend all our mornings in promenading about the town, which we

[page] 12

know pretty well, and in the evenings we go to the play to hear Miss Stephens, which is quite delightful… On Monday we are going to Der F (I do not know how to spell the rest of the word).… We just have been to Church and heard a sermon of only 20 minutes. I expected, from Sir Walter Scott's account, a soul-cutting discourse of 2 hours and a half.

I remain yr affectionate son,

C. Darwin

Three months later he described to his sister his impressions of the medical school:

Many thanks for your very entertaining letter, which was a great relief after hearing a long stupid lecture from Duncan on Materia Medica.… Dr. Duncan is so very learned that his wisdom has left no room for his sense, and he lectures on the Materia Medica, which can not be translated into any word expressive enough of its stupidity.* … Dr. Hope begins at ten o'clock, and I like both him and his lectures very much.… I dislike Monro and his lectures so much, that I can not speak with decency about them.…

I will be a good boy and tell something about Johnson again (not but what I am very much surprised that Papa should so forget himself as to call me, a Collegian in the University of Edinburgh, a boy).… You mentioned in your letter that Emma was staying with you: if she is not gone, ask her to tell Jos that I have not succeeded in getting any titanium, but that I will try again. [Here the editor deletes some words.] I want to know how old I shall be next birthday—I believe seventeen, and if so, I shall be forced to go abroad for one year, since it is necessary that I shall have completed my 21st year before I take my degree.

It was unkind of the editor to suppress the rest of the message to Emma. From the scandalous remarks about

* "A whole, cold, breakfastless hour on the properties of rhubarb." Letter to Hooker, 1847.

"The Mount, "Darwin's home in Shrewsbury

[page break]

[page] 13

lectures it is easy to guess that Charles Darwin is once more on the way to being called a poco curante. He seems not to care properly for scholarship. What he liked was to indulge his craving for collecting and observing. He found his way to Newhaven, a little port north of Edinburgh, and made friends of some fishermen, who took him trawling for oysters (whatever "trawl" meant at that time in those waters). He collected marine specimens. A much deeper impulse was at work in him—to see the how and why of sea-life. "Drs. Grant and Coldstream," he records, "attended much to marine zoology, and I often accompanied the former to collect animals in the tidal pools." When he inquired of Dr. Grant about certain little vesicles that floated in the water, the zoologist replied that they were seeds of the brown rockweed which was abundant everywhere about. That was standard knowledge. Any ordinary boy who had learned and remembered it would have deserved credit.

But Charles Darwin behaved most peculiarly in regard to this knowledge: he insisted on seeing, for himself, what came out of the vesicles. The more I ponder that boyish skepticism, the more amazing it seems. For the desire was so strange: to see, with his own eyes, what actually happened. That is the rarest impulse of the intellect. The human mind almost always prefers two other ways of solving problems—either to ask an authority or to use pure reason. If we ever encounter a mind that instinctively desires to see for itself, we know that we are in the presence of a superior being.

What came out of the vesicles was not rockweed at all. It was the young of a bright-green worm, a kind of leech. Charles discovered that another sort of floating vesicle had the power of locomotion and was a young animal hunting a place to start a colony of "sea-mats." He read

[page] 14

a paper on the animals before the Plinian Society, a student organization. When Dr. Grant later wrote a monograph on them (the genus Flustra) he credited the boy with the discovery.

So it is easy to understand why Dr. Grant enjoyed walking with young Darwin. What shall we suppose he felt about the boy's astonishment at the Lamarckian views? He doubtless assumed that any one so sharpeyed for details was lacking in power to apprehend more profound issues. A man who is intellectual and enthusiastic usually does pass that sort of judgment on the Darwin type of mind.

[page 15]

CHAPTER II

WHY YOUNG DARWIN WAS ASTONISHED AT DR. GRANT

IF I were reading about Darwin's career, I should want an early chapter to give me a background of his life—the guesses about evolution which were in the air when he was a youth. So I have made such a chapter and inserted it here. But I suspect that many of my readers will be happier if they omit it for the present. It should never be read by any one until he feels curiosity about the subject. You might try a few paragraphs, and then skip the rest if you begin to fidget at the theories. There is no narrative in Chapter II; the story continues in chapter III.

Suppose that Charles Darwin had been seven years older, that he had come to Edinburgh as a sixteen-year-old boy in 1818, and that he had taken a walk with a famous professor of mathematics at the University, John Playfair. It is possible that Playfair would have burst forth in high admiration of Spence and his views on perpetual motion. It he had done so, it is certain that Charles Darwin would have listened in silent astonishment. This imaginary case will make it easy to see why he was astonished at Dr. Grant's enthusiasm about perpetual change among the species of plants and animals.

Spence was a shoemaker who lived at Linlithgow, eighteen miles northwest of Edinburgh. He had an active mind. His mind became engaged with the ancient and fascinating puzzle of creating a mechanism that could run itself, with no supply of force from outside. At length he

15

[page] 16

constructed an apparatus, operated by magnets, which he claimed was a proof that a machine can generate its own energy. Most physicists of the period were entirely skeptical about perpetual motion, were not even interested in this latest of a long line of attempts to prove the theory, and felt perfectly certain that Mr. Spence's contraption was a fraud. But Playfair, who had been thirty years a professor of mathematics and had made authoritative textbooks on physics, inspected the shoemaker's machine and announced that it was a solution of the problem of perpetual motion. Perhaps there was some philosophical Scot in 1818 who had faith in squaring the circle. Perhaps there was another who admired the doctrine of the transmutation of base metals into gold. And if young Darwin had walked with them, and if they had burst forth in admiration of the theories, he would have listened in silent astonishment. Not that he had read the evidence. He knew nothing about mathematics or physics. He simply knew that those fanciful theories were regarded with skepticism by the learned world. Dr. Darwin was a skeptic about medical superstitions. He had taught his sons the folly of seeking for a philosopher's stone or a miraculous widow's cruse of energy. So his sons would have been astounded to hear from any savant an argument in favor of those doctrines.

In 1825 the Lamarckian view of evolution seemed a similar sort of folly to Dr. Darwin and his sons. The transmutation of species—whether of metals or of animals—was just a philosopher's dream. Conventional skeptics of that day might not presume to deny that transmutation or perpetual motion was possible; for physics had not yet made a complete demonstration of the conservation of energy, nor had chemistry actually disproved the existence of a simple "prima materia." It was an ignorant world in 1825. But the evidence was so

[page] 17

strongly negative that few practical scientists had any faith in those speculations which persuaded Professor Playfair and Dr. Grant. The speculations were, intellectually, bad form.

The fate of those two theories—perpetual motion and alchemy—illustrate what Darwin's labor was all about. And without such illustration we are likely to misconceive his life. Consider perpetual motion. The theory that a machine might forever generate its own power is too ancient to be traced to its source. It was a natural assumption for a primitive mind to make, and it was a proper and rational theory through the seventeenth century. Nobody is to be blamed for working with it seriously in the eighteenth century, because it could not be disproved. Nor does any one deserve any credit for holding the theory; it had long been common property. Credit belongs only to men like Joule, who investigated the facts of heat and energy in mechanism. When facts enough had been investigated, it appeared that perpetual motion is inconceivable. Hence all the clever intellects that once believed it are now disregarded, and any intellect that still persists in hoping for a revival of the theory is called mad.

Consider alchemy. It was less esteemed in 1825 than perpetual motion, but had not been absolutely disproved. It had been the common property of the intellectual world for fifteen centuries; hence no one deserved any credit for expounding it, or any blame for believing in it. Credit was due only to investigators of the facts of chemical reaction and the nature of matter. The historian of science does not celebrate Paracelsus for brooding upon possibilities, but extols a Mme. Curie for observing the fact that one radioactive element actually does change into another. We do not praise Arabian thinkers for arguing that there is one simple basis of all metals; we

[page] 18

praise J. J. Thomson for discovering facts which indicate that the one simple basis of all metals is electricity. In one sense he has merely proved the truth of the alchemists' theory. Yet the theory was only an idle dream; it was nonsense to Thomson and Rutherford; it did not direct their researches. Their fame was not earned by espousing a doctrine, but by discovering something about natural law in the universe.

The theory of evolution is a parallel case. It was as old as Aristotle. No one deserved credit for upholding it by a logical dissertation. The Lamarcks and Grants could have theorized till doomsday without contributing a jot to the intellectual advancement of the human race. The only man worth eulogizing would be one who could discover some facts—some evidence that the transmutation of species was as false as perpetual motion or as true as the new kind of electronic alchemy.

The notion of the transmutation of species was mere biological alchemy in 1825. It looked probable as a matter of logic, because any classifier of animals knew how the array of varied organisms formed a kind of ascending series, from animalcules to clams and on up through insects and reptiles to birds and monkeys. All along the extent of this series there were resemblances of structure that could hardly be thought accidental. To any naturalist, familiar with the endless similarities and overlappings in this gamut of animal forms, there was inevitably suggested an order of development. The animal kingdom looked as if it might have grown by a progressive development from simpler forms to more complex or "higher" forms. An ignorant man, who knew only a few dozen species of animals, would never have conceived such an idea of development. An unimaginative man could not have visualized a whole "scale of nature" in which the thousands of kinds of organisms formed steps

[page] 19

in a continuous stairway from sea-anemone to elephant. But if a naturalist had wide knowledge and strong imagination, he could not fail to see the scale of nature. Once he had seen it, he never could escape the haunting queries about it.

Aristotle caught this view of life twenty-two centuries before Dr. Grant felt his high admiration for a certain theory about it. Aristotle reasoned that there is a constant tendency of life to advance to higher forms, up a scale of increasing complexity, each step in which was a definite and peculiar form—a "species." Three centuries later, in Rome, Lucretius imagined that all nature has been a steady process of development by natural law, and that man has evolved from an early beast-like form. So this theory was sponsored by great names and was a proper speculation in philosophy. The literature of the eighteenth century was dotted with ideas of evolution of some sort. Thus, for one example, Boswell used to enjoy spurring Dr. Johnson by an allusion to Lord Monboddo's theory of the descent of man from a brutish ancestry. Johnson responded with sarcasm. "Manking would soon degenerate into brutes," he asserted when arguing for the advantages of social inequality; "they would become Monboddo's men; their tails would grow." When he wrote to Boswell about the failure of the Scotch to produce Erse manuscripts, he used Monboddo as a sarcastic illustration: "If there are men with tails, catch an homo caudatus. Shreds of evolution theories were so numerous in Europe that it would be mere pedantry to offer an account of them as a background or understanding Darwin's lifework. Of what use could it be to balance the opinions as to whether de Maillet did or did not set forth an evolution theory? Why would it be worth while to debate whether Bonnet's mystic words mean or do not mean what they seem or do not seem to say? Can

[page] 20

any modern mind feel an interest in the sort of evolution that Leibnitz and Kant philosophized about or Goethe intuited? The St. Hilaires, father and son, were admirable naturalists, whose opinions would be worth recording here—if they were known. But the father was so hesitant that the son had to interpret him; and modern commentators can not agree as to whether the interpretation is right or as to the meaning of the son's expression of his own views on evolution. Such exegetic ambiguities would be proper only in a history of guessing. We are told that Treviranus was not ambiguous, that in 1805 he spoke out loud and clear for a belief in progressive development; yet there are different opinions as to whether his speaking was of any moment.

I set down those names of some early evolutionists in order to show that their combined theories—however valuable in the history of speculation"have only a slight and antiquarian interest in the history of science. If Darwin had proved by the method of science that all evolution theories were as baseless as the perpetual motion idea, the early evolutionists would be shrouded in complete oblivion. They proved nothing. They did not even point out the road to any proof. They were of no help to Darwin and had no part in the building of a scientific hypothesis of evolution.

That way of stating the case, which may appear unjust and unphilosophical, is the most essential truth for any one who wishes to understand the meaning of Charles Darwin's life. At the age of sixteen Darwin was completely out of sympathy wirth Dr. Grant's enthusiasm for Lamarckian philosophy. And through all the rest of his days he was not to take any interest in speculations about the nature of species. He always continued to feel astonished at what he called the "nonsense" of such speculation he always preferred to examine some ob-

[page] 21

jects—like the seeds and eggs in the water at Newhaven—and to ask the world, as he asked Dr. Grant, "What do you make of these facts that I observe?" The business of his life was to show the futility of mere logic. He took his sling of observation in his hand and advanced against the great Goliath of Speculation, who championed the whole host of Philistine logic—the "views" of biologists, the beliefs of theologians, the conclusions of philosophy, the mysticism of natural philosophy, the faith in the power of pure reason to arrive at knowledge. This entire army of reasoners was animated by the assumption that a human mind, if it contemplated portentously, could give forth wisdom. They considered that acute Speculation was the greatest warrior among them. So they sent him forth against young Darwin. And this Goliath cursed Darwin by his gods of intellectual processes. And Darwin smote him in his forehead, that the stone sunk into his forehead. And of course this Goliath isn't dead yet, and probably will never die. But he has been less vigorous since the encounter.

Be patient with my little parable and my dogmatic way of setting up Darwin as an opponent of theorizers. I am aware of the exceptions and explanations that could be made and that will be made in the course of this book, I shall later describe Darwin as the man who was forever theorizing, who could not even begin an investigation without a preliminary hypothesis to attack or defend. And I shall tell of Darwin's concern about priority in developing a theory of evolution. But such facts are quite secondary and partial. Here, at the outset, I want to display the chief meaning of Darwin's career: that the result of his fifty years of observing nature was to teach the world not to rely on Speculation.

I am the more anxious to do this because every book about Darwin or his theory implies the contrary. A fair

[page] 22

sample of the misapprehension of Darwin's work is the following innocent-looking statement from a recent essay: "Goethe to some extent anticipated Darwin as to the possibilities of metamorphosis in the natural world." The inference is that Darwin somehow deserves less credit if a poet perceived certain evolutionary possibilities before Darwin investigated them. But the poet had not anticipated Darwin's work. Darwin had no poetical power to "perceive" a beautiful theory, full-formed, all in bulk. His business was to find out whether such a venerable theory was true. The two men were in different fields of mentality. No divination of poetry or philosophy can anticipate the knowledge that comes from dissecting barnacles and observing fossil armadillos and studying the methods of pigeon-breeders—and then unlocking all the dissimilar mysteries with one key.

Darwin's precursors are not being robbed of any glory. If it is a merit to have originated an evolution theory, then the precursors deserve all the glory. Darwin was not even in competition with them. He found their theory set forth in speculative books. It was his starting-point. If we are to follow his career with any interest, we must be clear as to where it began. A philosophizing world has generally assumed that Darwin, by long and deep thought, arrived at a theory as at a goal—where he found Goethe and Lucretius awaiting him, resting on their laurels. No, Darwin set out from this heap of easily-won laurels. He pressed toward an entirely different goal, which no one reached ahead of him, where his fame is now commemorated by a thousand tablets and ten thousand hosannahs from scientific admirers. The narrative of his victory begins with an evolution theory for which the diviners and anticipators deserve all the credit.

At the visk of seeming to delay too long before pro-

[page] 100

ceeding with the account of Darwin's youth I will give one further illustration of how the whole meaning of his life has been distored by a philosophizing world. Prof. John W. Judd, in his The Coming of Evolution, relates that he once fell in talk with Matthew Arnold, who exclaimed, "I cannot understand why you scientific people make such a fuss about Darwin. Why, it's all in Lucretius." When Judd argued that Lucretius had guessed what Darwin proved, Arnold retorted, "Ah! that only shows how much greater Lucretius really was—for he divined a truth which Darwin spent a life of labor in groping for." Arnold's judgement was axiomatic in the learned world of fifty years ago; the intellect that divined was glorified. The judgment is still accepted, as matter of course, by a large proportion of the literary and critical world. Does it seem valid to you? To modern science it seems topsy-turvy. In this life of Darwin you are to see why science regards Matthew Arnold as an arch-Philistine. Then you will be free to pitch your tent with the army of your choice.

In 1825 Dr. Grant stood with the forces of the diviners. He highly admired the ingenious intuitions of Lamarck. Whereas young Darwin could only regard it as he did the vesicles floating in sea-water. "What is actually inside of them?" he asked. Speculation about them was only to be regarded with polite silence. He would have sympathized completely with Dr. Johnson's summary of the Monboddo theory: "Knowledge of all kinds is good. Conjecture—such as whether men ever went on all four"is very idle."

The Monboddos and Lucretiuses fascinate the Arnold type of mind because their conjectures have proved true. In just the same way prophets fascinate most of us, because we are impressed by any true prophecy. The Darwins alone inquire about all the host of prophecies that

[page] 24

fail. Only the Darwins are interested in the myriads of clever conjectures that glitter for a time and then are dissipated. A conjecture—even a fortunate one by a Lucretius about evolution—is quite idle until some Darwin breathes life into it.

The theory of evolution that captivated Dr. Grant needs no description here. My readers want a man's career, not abstractions. I will give a brief indication of what the theory was, and then follow the history of our poco curante while he goes round the world to see all the rocks and animals and things that Dr. Butler considered so contemptible.

I am sure that any one who prepared a doctoral dissertation on the history of the Lamarckian views would find no legitimate date till he had come down through the ages to 1750, whe Buffon was beginning the publication of his forty-four tall volumes of Histoire Naturelle. And after Buffon he would find only two men who deserve attention before 1825—Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck.

Buffon had just the type of daring and lucid imagination that was fitted to gather up wisps of conjecture from philosophers and frame them for the first time into a rational structure that might appeal to a mere naturalist. It was Buffon who defined style so pregnantly that his sentance has become the most famous ever composed in French: "Le style est l'homme méme." It was Buffon who first among reasoners advanced the idea that our planetary system is the result of a collision of some cosmic wanderer with our sun. Though he was not an astronomer and could not, like Laplace, give a demonstration of his conjecture, he divined an astonishing possibility. As he looked at the system of planets, deployed in one plane and revolving one way, his skilful imagination said, "They look as if they were bits of matter drawn off attraction of some er-

[page break]

Georges Louis Leclere, Comte de Buffon

[page break]

[page] 25

ratic visitor—say a comet." And now the astronomers are strongly inclined to believe that his daring conjecture was right—except for the comet part of it.

Buffon was a handsome and wealthy man, of commanding presence and winning personality, who was secure in a high social position. Yet he devoted his life to science and worked hard all his days. Sixty years before Darwin was born he projected his elaborate compendium, splendidly illustrated, of all the world knew about animals. This was highly esteemed by the academic world and was very influential in stimulating a general interest in natural history among cultured people everywhere. It could safely have been assumed that Buffon's imagination would not be content with a mere assortment of information. He was interested in generalizing, in recording his impressions about the relations of great groups of facts. An Arnold could say that he "anticipated" all which Darwin labored so long to prove. An Arnold, for example, could say that all of Darwin's reasoning about artificial selection was implicit in this one brief passage about dogs:

It is not surprising that of all the animals this should be the one in which there are the greatest varieties of shape, of size, of color, and of other characteristics. Certain circumstances lead to this changing: the dog lives a short time, breeds often and rather numerously; and since it is forever under the eyes of man, as soon as—by a chance rather common in nature—peculiarities or apparent varieties are found in certain individuals, care is taken to perpetuate these by mating those peculiar individuals, as we still do when we wish to secure new races of dogs and of other animals. (Tome V, page 194; second edition, 1750.)

An Arnold could argue that the germ of Darwin's Struggle for Existence lies in another short passage of Buffon:

[page] 26

When we consider the boundless fertility given to every species, the innumerable progeny that result, the sudden and prodigious multiplying of some animals, we are astonished that they do not overrun nature.… It is really frightful to see these thick clouds of famished insects coming, which seem to threaten the whole world.… And have we not seen those torrents of the human race pour suddenly from their caves?…

These great events, however, are merely trifling changes in the usual course of animated nature. The course is, in general, always steady, always the same; its movement, always regulated, rotates upon two unshakable pivots—one, the boundless fertility given to every species; the other, the numberless obstructions which reduce the product of this fertility by a fixed rate, and leave, in the whole course of time, only about the same quantity of individuals in every species. (Tome VI, page 247.)

Even a modern scientist would admit that the embryo of an evolution theory is in another passage of Buffon:

So we see why there are such large reptiles, such big insects, such small quadrupeds, and such unemotional men in the new world. This is due to the nature of the land, the kind of climate, to the degree of heat and humidity, to situation, to the height of mountains, the amount of stagnant or running water, the extent of forests, and especially to the dry state of nature there.

[After descanting upon the remains of the mammoth found in many parts of the world.] How many other smaller animals must have perished without leaving us any evidence or token of their existence! How many other species, after their nature had been altered—that is to say, improved or degraded by the great changes of earth and waters, by the neglect or fostering of nature, by the long-continued influence of a climate that had become adverse of favorable—are no longer the same as they once were? And yet quadrupeds are, after man, the creatures whose nature is most permanent and whose that of birds and fishes varies

[page] 27

more; that to insects still more; and if we come down as far as to plants (which we can not exclude from animated nature), we shall be surprised at the quickness with which species vary, and at the ease with which they alter their nature by taking on new shapes. (Tome IX, pages 106 and 126.)

Reasons for believing in the descent of man were summarized clearly by Buffon; any reader who is curious will find them in the Appendix of this book. Also he will find there an account of how Goliath shook his spear at Buffon, and of how Buffon kissed the ground in token of surrender to the Philistines. It was probably this fear of Goliath that made Buffon deny his own theory and leave a puzzled world to guess whether or not there was any meaning in his now-you-see-it-and-now-you-don't discussion of species. He says that they alter their natures; also he says that their natures can not be altered. There is no one section of his work in which evolution is discussed to some definite conclusion. The comments on evolution are side-remarks, a few pages at a time, in the course of seven thousand pages. Scholars who now investigate the fifteen large tomes, striving to discover some consistent message, reach opposite conclusions as to Buffon's meaning. Even a Matthew Arnold could not reasonably claim that Darwin's effectiveness had been anticipated by Buffon's bits of mystifying self-contradictions.

Yet there was a powerful fertility in those ideas of Buffon's They stimulated the adventurous mind of Erasmus Darwin when, in 1756, he began to practise medicine; they flourished in Dr. Darwin's treatise on medicine. In this treatise there is frequent reference to "the ingenious Mr. Buffon." Also there is frequent reference to "Dr. Robert W. Darwin of Shrewsbury"—for Erasmus enjoyed giving prominence to his success-

[page] 28

ful son, and included a chapter written by him. Charles had read the treatise during his poco curante days at Shrewsbury. So Buffon was not a mere dead name to him, but was associated with pride in the fame of a grandfather and with admiration for a father. The extracts from the noted Frenchman's work are not mere antiquities in an account of Charles Darwin's youth. They formed part of the background of his family pride—all the more so because his grandfather had by no means been a disciple or imitator.

Erasmus Darwin was one of the most interesting characters in England during the last half of the eighteenth century. In 1757 he settled at Lichfield—just two years after Lichfield's most famous son completed his Dictionary of the English Language. Dr. Johnson, when he visited in Lichfield during the next quarter of a century, occasionally met Dr. Darwin, but there was no friendship between them. "They seemed to dislike each other cordially," wrote Charles Darwin in a sketch of his grandfather, "and to have felt that if they had met they would have quarreled like two dogs." Dr. Darwin once scribbled a stanza about Johnson's edition of Shakespeare:

From Lichfield famed two giant critics come,

Tremble, ye poets! hear them! "Fe, Fo Fum!"

By Seward's arm the mangled Beaumont bled,

And Johnson grinds poor Shakespeare's bones for bread.

Dr. Darwin was tall and heavy; he stammered; he was witty; in an age of heavy drinking he was a teetotaler. Though unorthodox, he wrote an ode against the "dull atheist," and he defined Unitarianism as "a feather-bed to catch a falling Christian." In general he sympathized with liberal or revolutionary thought; he

[page] 29

wished for the success of the revolutions in North America and France; he expressed his hatred of slavery by writing:

Fierce SLAVERY stalks and slips the dogs of hell.

He espoused the revolutionary idea that all kinds of plants and animals may have descended from one common ancestor; he had some correspondence with the revolutionary Rousseau; he exchanged letters with the very revolutionary geologist Hutton.

His mind always ran to the novel and ingenious in any line of thought. The friend in whom he most delighted was R. L. Edgeworth, the father of Maria, who was perpetually engaged with such inventive efforts as the making of a telegraph and the educating of his children by improving on Rousseau's methods. Dr. Darwin made a "talking head" which produced some of the consonantal sounds accurately. He observed the wind by means of a vane which operated a dial in his study. He investigated artesian wells and rotary pumps and canal-locks. He did not subscribe to Buffon's theory of the origin of the planets, but conceived that they were shot forth by solar volcanos. He studied the history of the steam engine, and forty-four years before the first load of passengers was hauled on Stephenson's railway he boldly predicted:

Soon shall thy arm, unconquered steam, afar

Drag the slow barge, or drive the rapid car;

Or on wide-waving wings expanded bear

The flying-chariot through the fields of air.

His vivid imagination drove him to the writing of verse as a fit way of showing the wonders of plant life. In the opening canto of his first poem, The Economy of

[page] 30

Vegetation, 1781, he invokes the Botanic Goddess, who is to bring in her train Pomona, Ceres, and Flora. Spring comes, with her Zephyrs and Gnomes and Sylphs and Nymphs, and in a speech of three hundred lines summons the spirits of heat. She bids them "assail the Fiend of Frost" through all the northern regions, in another apostrophe of nearly two hundred lines. "The exulting tribes obey"—and so ends Canto I. This mass of rhetorical mythology would be an absurdity to twentieth-century readers. Nor would they concede much poetical merit to Dr. Darwin's way fo describing the wonders of nature—for example, the way in which plant-lice procreate without mating for several generations and then procreate by mating:

Unmarried Aphides prolific prove,

For nine successions uninform'd of love;

New sexes next with softer passions spring,

Breathe the fond vow, and woo with quivering wing.

Yet the Doctor's three volumes of poetry were highly esteemed in their day. No less a critic than Horace Walpole testified in 1792, of a passage called "The Triumph of Flora": "It is most beautifully and enchantingly imagined; and the twelve verses that by miracle describe and comprehend the creation of the universe out of chaos, are in my opinion the most sublime passage in any author or in any of the few languages with which I am acquainted." The public liked the botanical poems; so popular was the first volume that the publishers advanced a thousand guineas on the second volume before it was printed—an extraordinary sum for that sort of matter in those times.

The poems deserve a mention in a life of Charles Darwin, not because of their large sale, but because of the

[page] 31

copious notes that the Doctor delighted to add to them. Half of every page, on the average, is occupied by fineprint notes, and then the second half of each volume is filled solid with "Additional Notes." These are about all conceivable topics: a dark day in Detroit, Sir Joshua Reynolds' theory of art, opium-eating, the London Plague, divining-rods, sleep, alcohol as the curse of the Christian world and as the cause of hereditary diseases, the Gulf Stream, meteors, fossil tar, etc., etc.

The notes on botanical subjects prove that the Doctor was a close and expert observer who had a vast lot of dependable information. He was also an enthusiastic gardener: "I had last spring six young trees of the Ischia fig with fruit on them in pots in a stove" [i. e., a green-house]. He was a painstaking anatomist of plants as well as a romantic lover of them.

He loved to let his imagination play with the mysteries of their reproduction. Especially he seems to have been struck by the remarkable statements and speculations of the early evolutionist Bonnet:

Mr. Bonnet saw four generations of successive plants in the bulb of a hyacinth. [Note that Erasmus never flattered himself that he could see any such marvel.]

Mr. Bonnet says the male salamander… Who knows but the power of the stamina of certain plants may make some impression on certain germs belonging to the animal kingdom?

I am acquainted with a philosopher, who thinks it not impossible, that the first insects were the anthers or stigmas of flowers; which had by some means loosed themselves from their parent plant; and that many other insects have gradually in long process of time been formed from these; some acquiring wings, others fins, and others claws, from their ceaseless efforts to procure their food, or to secure themselves from injury. He contends that none of these changes are more incompre-

[page] 32

hensible than the transformation of tadpoles into frogs, and caterpillars into butterflies.

(The curious reader will enjoy comparing that acknowledgment of the source of an idea with what is said about Lamarck in Section 3 of the Appendix of this book.) Imagine how that notion, of stamens as the forefathers of insects, affected the grandson—the skeptical youth of a new world of thought, the boy who would not take the word of an expert about certain vesicles of plants and animals that floated off Newhaven.

These glimpses of poetry and annotation give the impression that Dr. Erasmus Darwin had a somewhat flighty mind. But he was a fellow of the Royal Society and a very hard-headed physician, with a wide reputation for professional skill. A London physician once came to consult him as "the greatest physician in the world," and when Dr. Darwin referred him to the celebrated Dr. Warren, replied, "Alas! I am Dr. Warren. I want you to tell me how much longer I have to live." Dr. Darwin's prognosis was "not many weeks." Dr. Warren died within two weeks. King George III knew of Dr. Darwin, and once said of him, "Why does he not come to London? He shall be my physician if he comes." Dr. Darwin wrote a book of guidance for medical practitioners that was republished in America and translated into German, French, and Italian, Zoonomia; or the Laws of Life. The "Introductory Address" to the American edition thus characterizes the book: "Though evidently a work of much labour and study, it appears notwithstanding to be the result of accurate and profound observation, rather than of extensive reading." The estimate is just, for the great bulk of the two volumes consists of direct report and analysis of his experience. The whole book is replete with the keenest obser-

[page break]

Erasmus Darwin, M.D.

Grandfather of Charles Darwin born in 1731, died in 1802

[page break]

[page] 33

The last of the thirty-nine sections of Volume I (Section 40 is an addendum by Dr. Darwin of Shrewsbury) treats of the greatest mystery of nature, with which Buffon had wrestled at great length, Generation. The section is forty-three pages long. It argues for two conceptions of the way an individual begins his life: (1) that the male furnishes the real seed of the embryo, the female egg being merely a nest for nourishing it; (2) that sex is determined by the condition of mind of the male at the moment of fertilization. In support of number two he is not afraid to be quite specific:

For instance: I can conceive, if a turkey-cock should behold a rabbit, or a frog, at the time of procreation, that it might happen, that a forcible or even a pleasurable idea of the form of a quadruped might so occupy his imagination, as to cause a tendency in the nascent filament to resemble such a form by the apposition of a duplicature of limbs.

Such a notion was a sheer absurdity to Dr. Darwin of Shrewsbury, who did not even credit (what is still widely believed among intelligent people) that a violent emotion in the mind of a pregnant woman can produce a corresponding effect in the embryo. Imagine, then, how the notion would cast a ludicrous hue upon other ideas in Zoonomia—for instance, upon the idea of an evolution of all living beings from one simple primary form. Dr. Erasmus Darwin set forth that idea in several of the notes to the poems and in several passages of Zoonomia. I will cite only four sentences here; some longer quotations are given in Section 2 of the Appendix.

All animals have a similar origin, viz. from a single living filament; and the difference of their forms and qualities has arisen only from the different irritabilities and sensibilities of this original living filament…

[page] 34

Hence, as Linnæus has conjectured in respect to the vegetable world, it is not impossible but the great variety of species of animals which now tenant the earth may have had their origin from the mixture of a few natural orders. (Page 367.)

When we revolve in our minds the great similarity of structure which obtains in all the warm-blooded animals, from the mouse and bat, to the elephant and whale, one is led to conclude that they have alike been produced from a similar living filament. In some this filament has acquired hands and fingers; in others toes; in others it has acquired claws or talons.

It is safe to suppose—from Charles Darwin's silent astonishment in 1825 and from what we know of his life during the next twenty years—that this speculation about "a living filament" seemed as groundless to him as the speculation that a male child would be formed if a father's mind happened to be more occupied with his own body than with his wife's. A theory of common descent, by changing species, from a primordial filament, would seen unfounded to a boy who challenged The Wonders of the World and who admired an unspeculative father.

Surely a Matthew Arnold could not believe that a Darwinian theory "was all in Zoonomia." The theory of Erasmus Darwin gained no credence. It was styled "Darwinising" by Coleridge and (says krause) "was accepted in England nearly as the antithesis of sober biological investigation."

Arnold could have argued somewhat plausibly, however, that an evolution theory was all sketched in a two-volume book published in the very near Charles Darwin was born. The author was a young "chevalier," J. B. P. A. de M. Lamarck. He was twelve years old when Erasmus Darwin began to practise medicine in the first year of the Seven Years' War (1756). In the fifth year of that war when he was almost sixteen, he left his na-

[page] 35

tive hamlet of Bazentin-le-Petit in northern France, which was in the line of trenches of the World War, midway between Amiens and Cambrai. He was bound for a battle-field a hundred miles away, beyond Antwerp, where an older brother had already been killed. His family was so poor that he had to ride an old and disreputable horse. Though he had had no military training, and was too scrawny even to look like a soldier, he forced his way into a company of grenadiers that was ordered to a hopelessly expossed position. When all the officers and most of the men of his company had been killed, he rallied the handful of survivors and refused to retreat. So remarkable was his valor that he was made an officer as soon as he had been rescued. This brilliant beginning of a military career was spoiled, not long after, by a prank of a comrade, who lifted him by the head in such a way as to injure his neck. So the poor fellow—weakened and in poverty—went to Paris to earn a living as a clerk in a bank.

The fighting quality and the hard luck marked all the rest of his life. He plunged into the battles of science as recklessly as he had forced himself into the army, fighting his way to prominence where veterans would have been afraid to venture. Before long he was challenging the teachings of the most prominent chemists; he developed extraordinary conceptions of mineralogy; he was not afraid of novelties in medicine; and he made himself a master of botany. So original—and so correct and through—was his system of classification that Charles Darwin guided himself by it when he went round the world. In 1778, when he was thirty-four years old, he published his French Flora in three volumes. This was so useful and brilliant a work that it brought him fame as scholar and placed him among the world's leading botanists.

[page] 36

It called him to the attention of Buffon, who secured for him an appointment as "Royal Botanist," by the terms of which he was to travel over Europe for two years and familiarize himself with the principal herbariums and museums. With him he took Buffon's son, whom he tutored.

On his return he was made Keeper of the Herbarium of the Royal Garden. All this looks rosy. But his life was pitifully hard. He never could secure a salary or an income sufficient for decent living. During twenty-five years, while he brought prestige to France by vast scientific labors, he could hardly provide fit food and shelter for his family. His largest salary was never more than six hundred dollars a year.

When he was almost fifty years old he was appointed to a chair of zoology at the Royal Garden; and, even at this age, pushed to the front of academic battle as ardently as if he were still sixteen. He braved previous classifiers by announcing that all animals ought to be divided into two great groups—those that have a backbone and those that have not. The zoologists have ever since conceded that this grouping was his invention and that it was a wise one. His field of work in zoology was among the invertebrates—a vast horde of forms, almost unknown and very difficult to assort. Again he was where the fighting was hardest, and again he won distinction. He became the founder of paleontology, and the leading zoologist of his period.

Seven volumes about the invertebrates flowed from his pen; he wrote learnedly on "hydrogeology," on shells, on physiology, on sound and heat, on the moon's influence upon the air, on instincts. Yet his eyesight was failing all the while. The last ten years of his life were spent in blindness. His poverty never decreased. He and three children. His ideas were re-

[page] 37

garded with silent astonishment by young skeptics in 1825. He died in 1829.

Through the century since his death there has been magic in his theory of evolution. His teachings have continued to fascinate philosophical minds; even to-day there are zoologists who pair him with Darwin and believe that his theory of evolution contains a great truth. It may be fairly presented by three short quotations from his two-volume Philosophie Zoologique, 1809. In this work—as in the works of Buffon and Erasmus Darwin—the aim is not to present a theory of how life developed. The aim is to show the nature of animal life—what bodily motions are, what consciousness and intelligence are.

The first of the three parts of the book is a preliminary survey of the classification of animals and of the nature of the "species" into which they are divided. The seventh of the eight chapters of this Part I is entitled: "On the influence of conditions upon the actions and habits of animals, and the influence of these actions and habits upon organisms, as causes which modify their structure and parts." The fifty pages of the chapter, hardly more than a tenth part of the whole work, are the source of Lamarck's fame as an evolutionist. He set forth his idea of development very picturesquely and unmistakably. The figures refer to the pages of Volume I.

245. When snakes had formed the habit of creeping on the ground and hiding under plants, their body, because of ever-repeated efforts to stretch itself out in order to pass through narrow places, acquired a length, out of all proportion to its bulk. Now feet would have been very unserviceable to these animals and therefore useless.… So the lack of use of these parts, having been constant in the races of these animals, has caused these same parts to disappear entirely, although they were really in the structural plan of animals of their close. Many insects which by the natural char-

[page] 38

acter of their order and even of their genus, should have wings lack them more or less completely, because of lack of use.

249-251. I am now going to prove that the continual use of an organ—with the efforts made to derive much advantage from it in conditions that make demands on it—strengthens, stretches, and enlarges this organ, or makes out of it new organs which can perform the functions that have become necessary.

The bird, which need attracts to the water to find there the prey on which it lives, stretches out its toes, when it wants to strike the water and move on the surface. The skin which unites these toes at their base forms, by the ever-repeatd stretchings of the toes, a habit of spreading; thus, in time, the large membranes that unite the toes of ducks, geese, etc., take such shapes as we see. The same efforts made to swim—that is, to push the water in order to get ahead and move in this liquid—have spread in the same way the membranes between the toes of frogs, sea-turtles, the otter, the beaver, etc.

Again, we see that the same bird, wishing to fish with out wetting its body, must make continual efforts to lengthen its neck. Now the results of these continual efforts in this individual and in those of its race must, in time, have lengthened their neck remarkably; this is, indeed, proved by the long neck of all shore-birds.

260. When the will determines an animal to any action, the organs that are to execute this action are at once incited to it by the flow of subtle fluids (the nervous fluid).… The result is that multiplied repetitions of these acts of organization strengthen, extend, develop, and even create the organs that are necessary for them.…Now every change acquired in an organ by a habit of use sufficient to produce it is thereafter preserved by reproduction [génération], if it is common to the individuals that, in the impregnation, came together for the propagation.

An admirer of Lamarck would say that his theory can not be fairly judged by these three brief extracts. Espe-

[page] 39

cially he would caution a reader that Lamarck's reasoning about the "will" is not what it might appear to be in the last paragraph. (So I have provided in the Appendix some further quotations.) But, even when allowances have been made for extracts thus snatched from their context, we can see why a Darwin would be astonished at the Lamarckian views. The reason is cogent: the views were not based on observed facts; they were conjectures. In the nine hundred pages of the Philosophie Zoologique there is no appeal to observations that other men have been able to make. The opening words of Chapter VII are, "We are not concerned here with abstract reasoning, but with the investigation of a positive fact"; and three pages later Lamarck declares, speaking of how needs give rise to inheritable habits, "This is easy to prove, and does not even require any explanation to be understood." That pair of statements fairly represent the argument of the whole chapter. The reader is strongly assured that positive facts are being talked about, but the facts never are explained in such a way that the rest of us can see them. The reader never encounters any concrete example of the"fluids" nor of the inheritance of the habits—never so much as a single shred of evidence that points to possible examples. Lamarck had no interest in observation or examples. He always felt that what he visualized was actual and was already demonstrated. His most ardent admirer—his biographer, A. S. Packard—confesses that Lamarck's chemical views were "formed without reference to experiment;" and most scholars of to-day feel the same way about his zoological views. Their state of mind when they contemplate Packard's eulogy is just that of Charles Darwin when he heard Dr. Grant's admiration.

The charm of Lamarck's way of thinking is a deathless one for the human brain, because it is based on per-

[page] 40

sonality, on striving, on the power of the will. Our instinct dreads the impersonal, the reign of fixed, mechanical law to which no purpose or will-power is admitted. All philosophical minds flinch from Darwinism. They respond yearningly to some inner, vital principle of Lamarckism. The reasoning of Lamarck was always absurd to the band of scientists who were destined to rally to Darwin.

It will be interesting to take a peep at the five principal members of the band on the afternoon of a day early in December, 1825.

The oldest, Charles Lyell, is twenty-eight years old. He is a barrister who has been on the western circuit for a few months. The letter that he writes to his sister contains items like these: "Coleridge informed me yesterday.… Scrope wants me to pay a visit to Waverley Abbey. He is a gentlemanlike man of fortune, and has just published a very creditable work on volcanos." Lyell always liked men who were gentlemanlike and who had an interest in geology.

Asa Gray is a fifteen-year-old boy who lives at the border of the Adirondacks, on the "Presbyterian side" of the creek, close to the Presbyterian church, which he attends every Sunday. He will enter a rustic medical school next fall and will long for such European advantages as Charles Darwin enjoys.

Joseph Dalton Hooker, though only eight years old, is bravely attending his father's botanical lectures in Glasgow and is having a hard time with Latin grammar, but is "bending all his soul and spirit to the task."

Alfred Russell Wallace will be three years old next month. He is toddling about in the yard of a humble home in the village of Usk, seventy-five miles south of Shrewsbury.

Thomas Henry Huxley is a babe of seven months in

[page break]

Courtesy Longmans, Green and Co.

Portrait of Lamarck, when Old and Blind, in the Costume of

a Member of the Institute, Engraved in 1824

[page break]

[page] 41

the home of a schoolmaster who teaches in a London suburb, Ealing, which lies six miles west of the Marble Arch. His mother thinks the child looks intellectual. Charles Darwin, aged sixteen and skeptical, would probably have listened to this estimate with silent astonishment.

[page] 42

CHAPTER III

CAMBRIDGE AND THE BEAGLE

CHARLES DARWIN'S attempt at a medical education lasted only two years. Most of the lectures were insufferable to him, both because of the subject-matter and of the dry formality of presenting it. The sights and sounds and smells of the clinics always remained horrible memories. Only twice did he venture into the operating theater (this was before the day of anesthetics), and both times had to run away from the unendurable spectacle. "The two cases fairly haunted me for many a long year." To be sure, he made interesting acquaintances during the second year and enjoyed the companionship of young men of scientific tastes. He became a favorite with the curator of the museum, a noted ornithologist. Otherwise Edinburgh furnished him little of the stimulus he craved. Even of the Royal Medical Society he felt that "much rubbish was talked there." Audubon's lectures on birds were interesting, though he "sneered unjustly at Waterton." But Darwin was prejudiced, because he had enjoyed lessons in bird-stuffing given by a negro who had worked with Waterson. Except for this little education in birds, he seems not to have been able to stomach the training he could find at Edinburgh. One professor's lectures on zoology were incredibly dull, and his field lectures denied what any good pair of seventeen-year-old eyes could see was the fact. "The sole effect the lectures produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on geology, or in any way to study

[page] 43