[page]

Charles Darwin, a couple of years after his return from the Beagle voyage Source: N. Barlow, Charles Darwin's Diary of the Voyage of HMS Beagle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1933). The drawing is probably by George Richmond.

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

Patrick Armstrong

[page]

CONTINUUM

The Tower Building 80 Maiden Lane

11 York Road Suite 704

London SE1 7NX New York, NY 10038

© Patrick Armstrong 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmittted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Patrick Armstrong has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identied as Author of this work.

First published 2004

Reprinted 2006 (twice)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 0-8264-7531-0 (hardback)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

[page]

Contents

Acknowledgements vii

List of Figures ix

Chronology xi

Abbreviations xiii

1 Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview 1

2 Darwin's Islands in Context 11

3 The Mystique and Myth of the Galapagos - and the Reality 20

4 The Islands That Never Were 31

5 St Jago, Cape Verde: Source of Inspiration 38

6 The Smallest Rocks in the Tropical Seas: St Paul's Rocks and Fernando Noronha 46

7 Brief Interlude in the Abrolhos 55

8 The End of the Earth: Tierra del Fuego 59

9 Changing Environments, Changing Ideas: The Desolate Falklands 79

10 Chiloe: A Fine Island 107

11 The Chonos Archipelago: A Multitude of Islets 131

12 Across the Wide Pacific: To Tahiti and Beyond 138

[page]

Contents

13 New Zealand: Maoris and Missionaries 155

14 Australia: The Great Princess of the South 166

15 Tasmania: A Geological Laboratory 183

16 I am glad that we have visited these Islands': The Cocos (Keeling) Atoll 196

17 Mauritian Interlude 214

18 A Rock and a Cinder: St Helena and Ascension 223

19 The Last Island: Terceira, Azores 233

20 Conclusion: Islands, Inspiration and Ideas 246

Index 259

VI

[page]

Acknowledgements

My interest in Charles Darwin began very early in my Cambridge childhood, when I used to see his granddaughter, Gwen Raverat, painting with an easel mounted on her invalid carriage, along the Backs of the colleges and elsewhere on the banks of the River Cam. She was regarded locally with something akin to awe. I clearly recall, as a very young lad, watching from a discreet distance as she painted a view over the Mill Pond, adjacent to the Silver Street Bridge, from Laundress Green, just a stone's throw from Newnham Grange, the house in which the Darwin family lived for generations, and the adjoining Old Granary. These were the properties that Gwen immortalized in her book Period Piece: A Cambridge Childhood, and which in 1964 formed the basis for Darwin College, where in the 1980s I was able to spend two wonderful periods of sabbatical leave, undertaking some of the research upon which this book is based. Over a century earlier Charles used to walk along the Backs, sometimes with his mentor, the Reverend Professor John Stevens Henslow, past King's College Chapel (sometimes he would attend evensong), and so he must have followed a similar route to my regular peregrination during those periods of study-leave, from Darwin College to the University Library (open fields in Darwin's day) wherein the greater number of his manuscripts and notebooks are now preserved. I cannot, therefore, avoid expressing my heartfelt thanks to my parents, the late Edward and Eunice Armstrong, who chose to live in Cambridge during the formative period of my youth, and to the University of Western Australia, my present employer, who enabled me to return there many decades later, as well as to those at Darwin College and the Cambridge University Library Manuscripts Collection who provided assistance.

Funding for field research, in Darwin's footsteps, and in the Beagle's

[page]

Acknowledgements

wake, was provided by the Centre for Indian Ocean Studies (Perth, Western Australia) and the Committee for Exploration and Research of the National Geographic Society (Washington, DC), as well as the University of Western Australia. St Deiniol's Library, Hawarden, North Wales, with its incomparable resources for the study of nineteenth-century thought, has on several occasions provided exactly the right environment for thinking and writing. Other institutions that have allowed me access to archives or specimens include: The Natural History Museum (London), the University Zoological Museum (Cambridge), the Public Record Office (Kew), which holds the Beagle log and other material relating to the voyage, Shrewsbury School, the Royal Naval Hydrographic Office (Taunton), the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia) and Yale University Library (New Haven).

I thank also, with all my heart, my dear wife Moyra, who has had to live with Darwin, as well as a sometimes-preoccupied husband for nearly two decades. Other individuals who have encouraged, supported, discussed, disagreed, accommodated or fed me, or just 'been there' for a Darwin-hunter, in several continents include: Alan and Robyn Cadwallader, Viv Forbes, Peter Francis, Peter Gautrey, Brian Shaw, Kenn Back, Jim Moore, Alun Cooper, Geof Martin, Mark and Vanessa Seaward, Pauline Bunce, Jill and Phil Rutherford, Andrew Allott, Bob and Marion Keegan, John and Alison Underwood, Sarah Lumley, Marion Hercock, Arthur Conacher, Tim and Paula Armstrong, Nick and Ros Philpott, Sheelagh and Robert Hethering-ton, Nancy Hudson-Rodd, Brook and Eileen Hardcastle, Jim McAdam, Mike and Sue Morrisey. And many more.

viii

[page]

List of Figures

Note: Unless otherwise indicated on the figures, all photographs are by the author and all maps and diagrams were drawn at the School of Earth and Geographical Sciences, University of Western Australia.

Frontispiece Charles Darwin, a couple of years after his return from the Beagle voyage

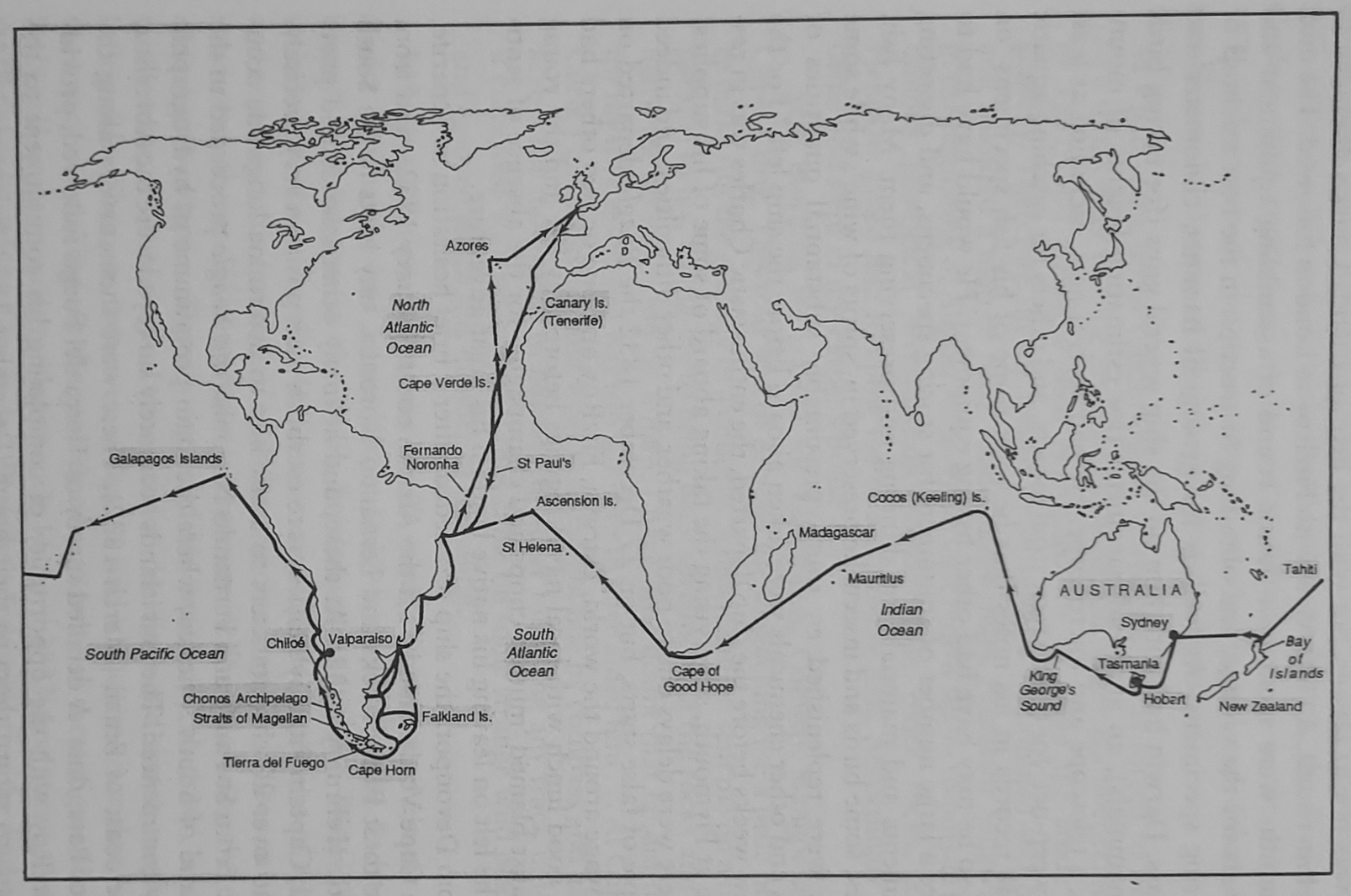

1.1 Map to show the approximate route of HMS Beagle (1831-36), and positions of some of the islands visited 6

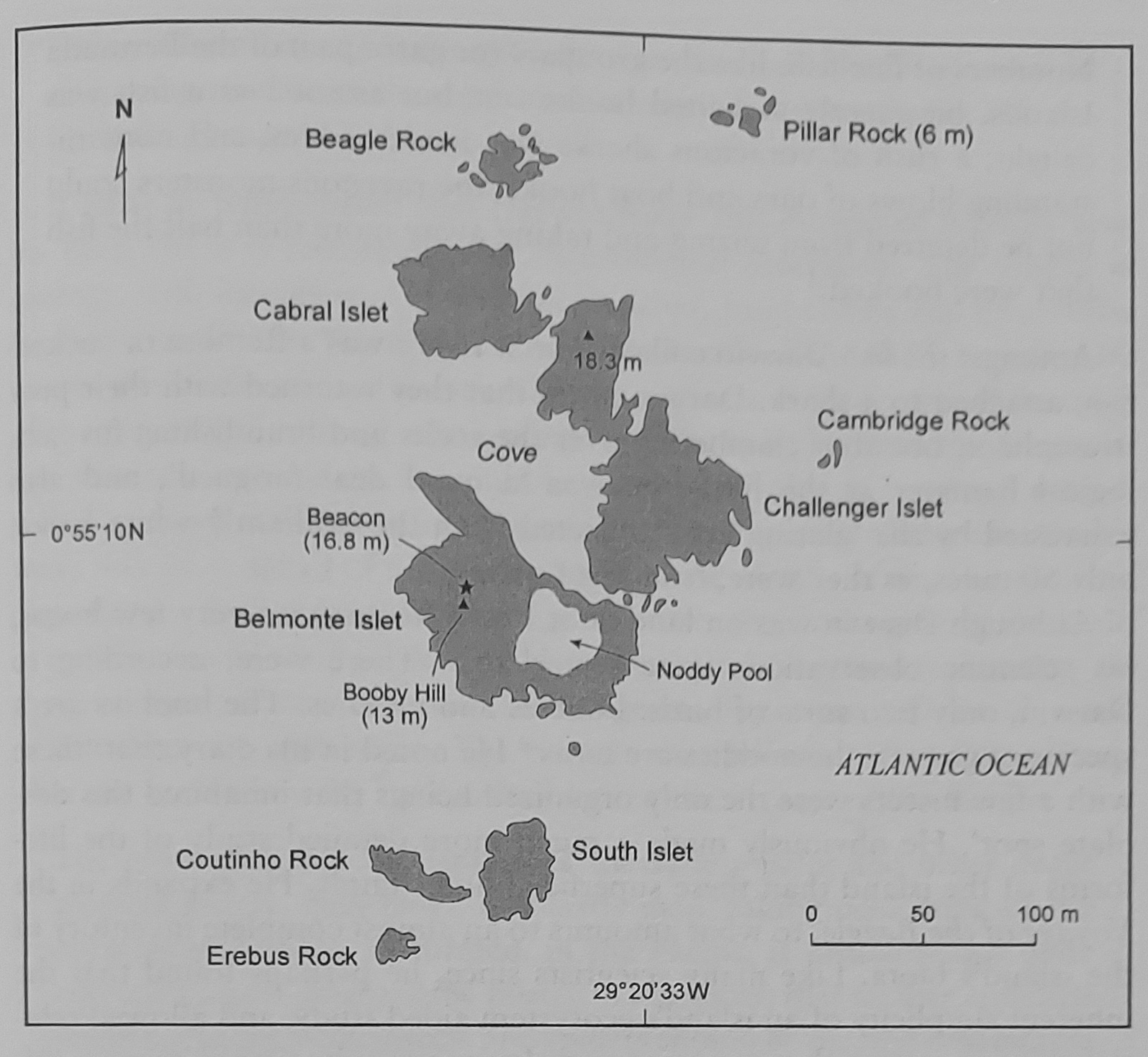

6.1 Map of St Paul's, Atlantic Ocean 47

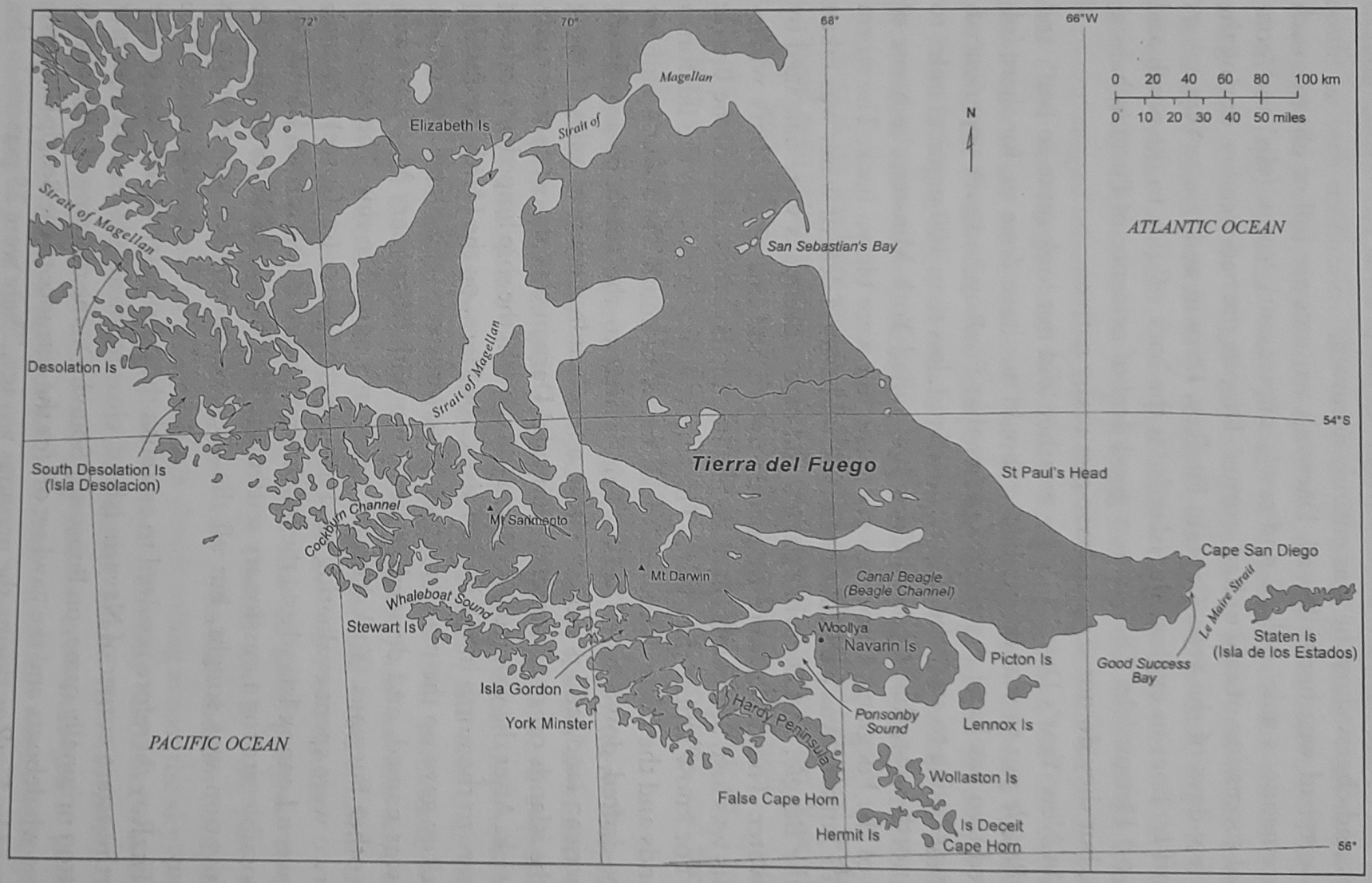

8.1 Map of Tierra del Fuego, showing some of the places mentioned in the text 62

8.2 The Beagle Channel, looking south 63

8.3 'Darwin's fungus' (Cyttaria darwinii), growing on Nothofagus trunk, Tierra del Fuego 72

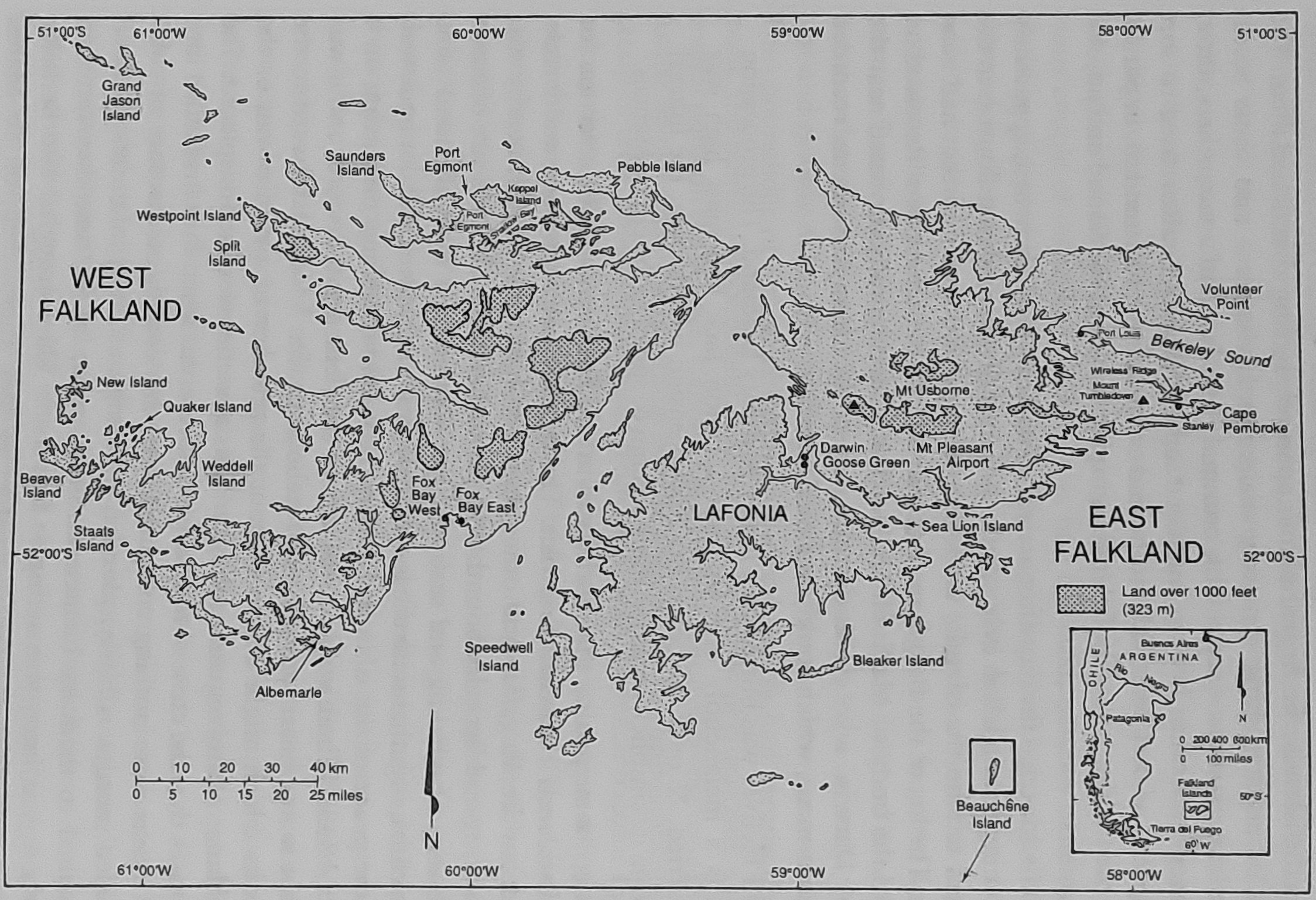

9.1 Map of the Falkland Islands 82

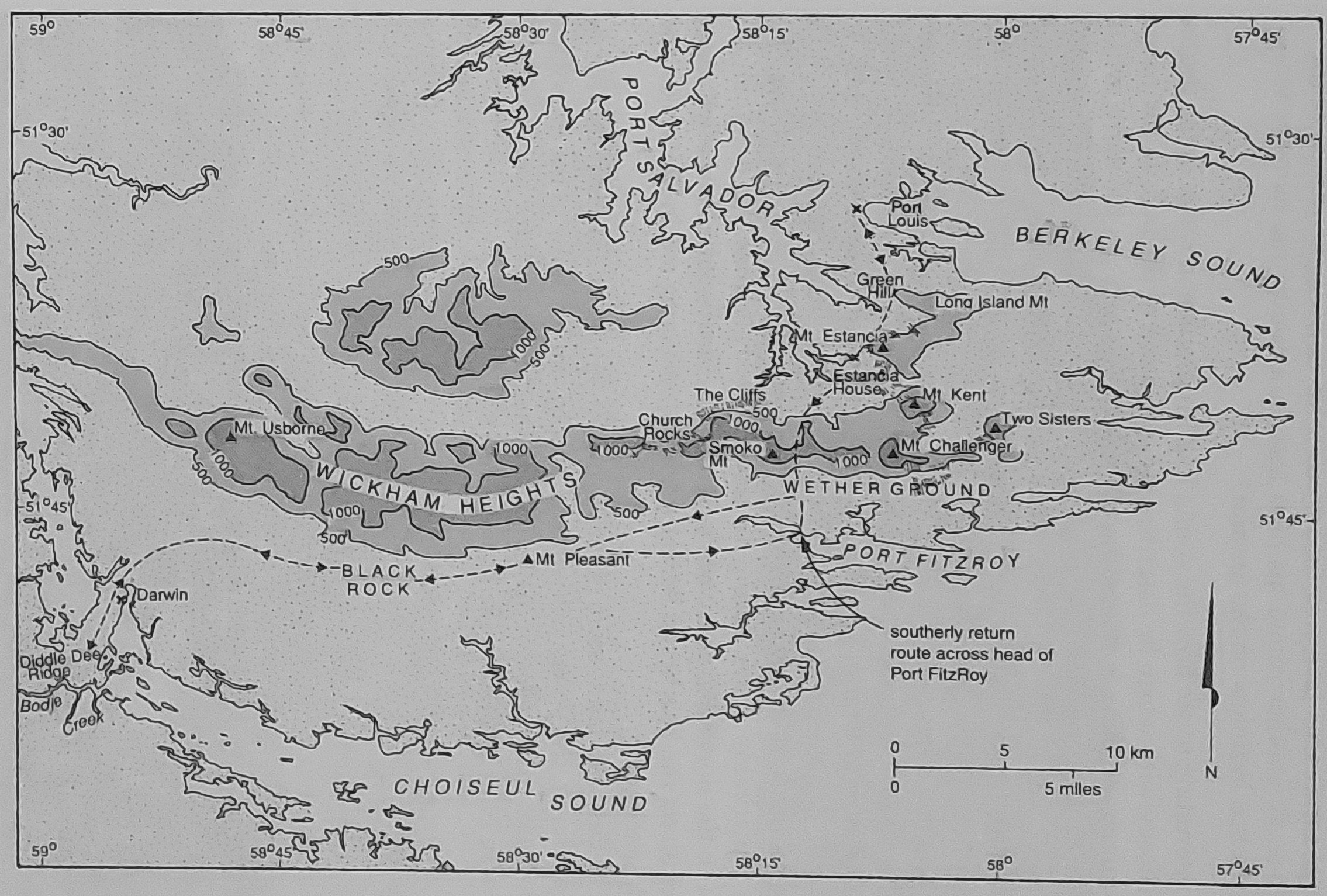

9.2 Map of Berkeley Sound, East Falkland, showing the various Beagle anchorages, and other places mentioned in the text 83

9.3 Darwin's excursion with the gauchos, March 1834 85

9.4 Settlement of Port Louis, East Falkland, in the 1830s 86

9.5 Settlement of Port Louis, East Falkland, in the 1980s 87

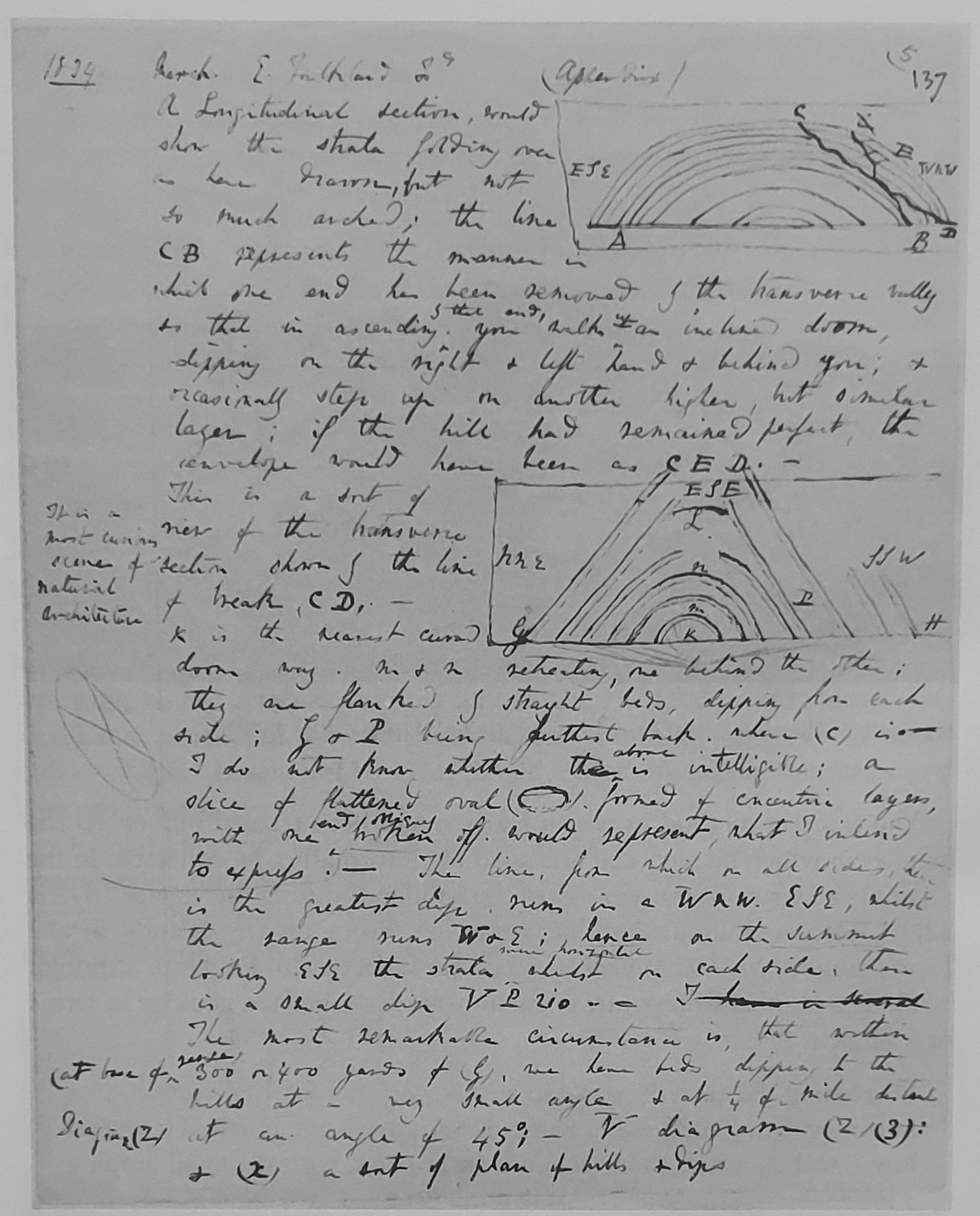

9.6 Darwin's geological notes of the folding of rocks in the Falklands 88

9.7 Darwin's 'zone of upheaval' (anticline), south of Berkeley Sound, East Falkland 89

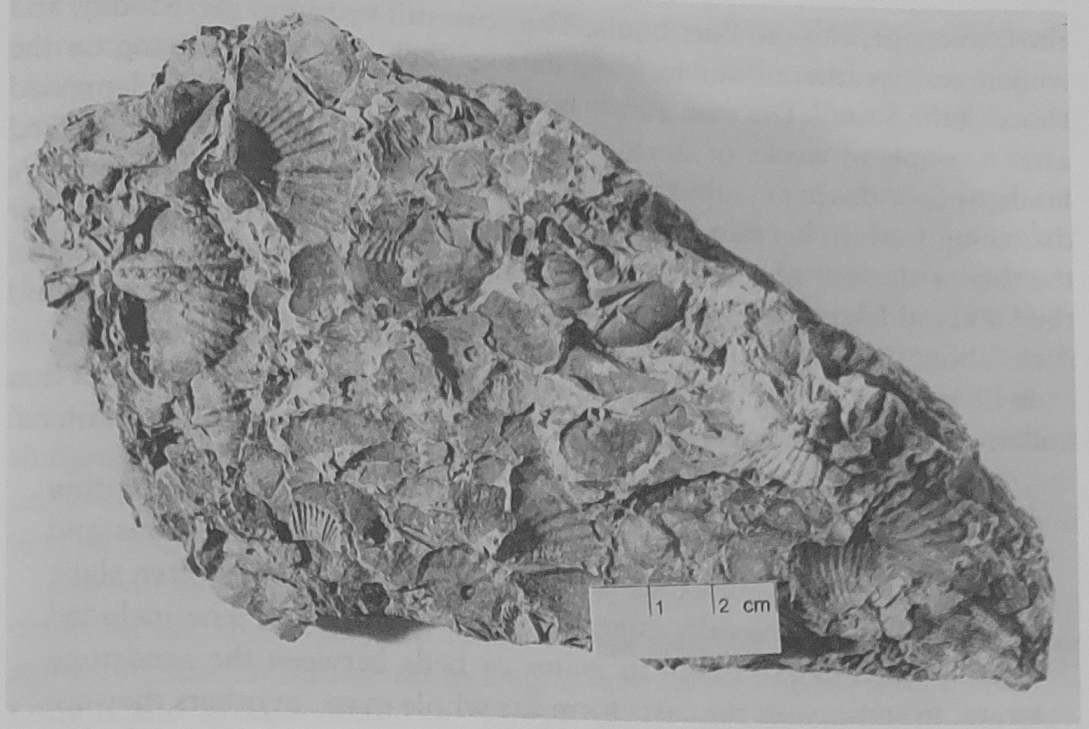

9.8 Fossils from rock exposures, Berkeley Sound 91

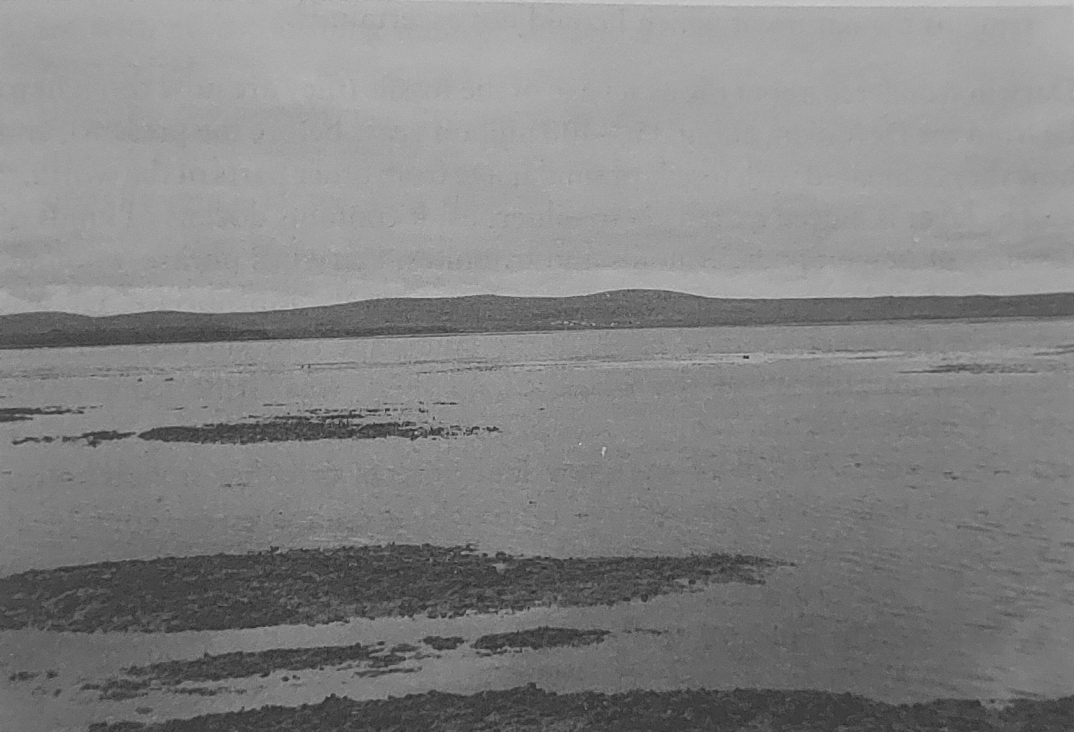

9.9 Berkeley Sound, East Falkland 91

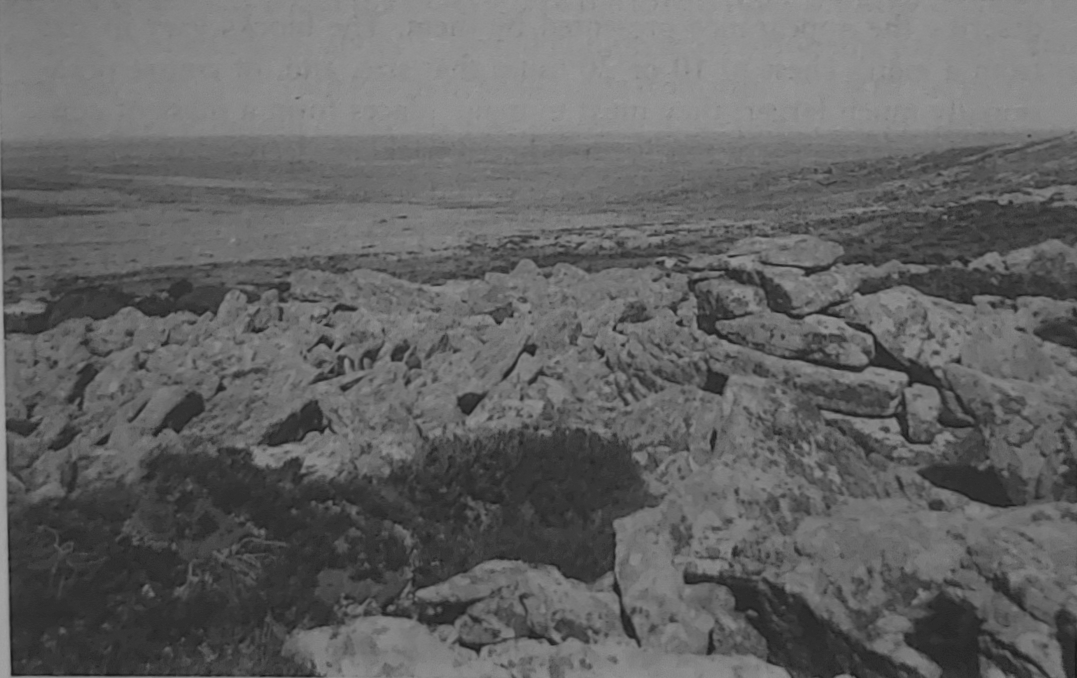

9.10 Stone-runs, East Falkland 94

ix

[page]

List of Figures

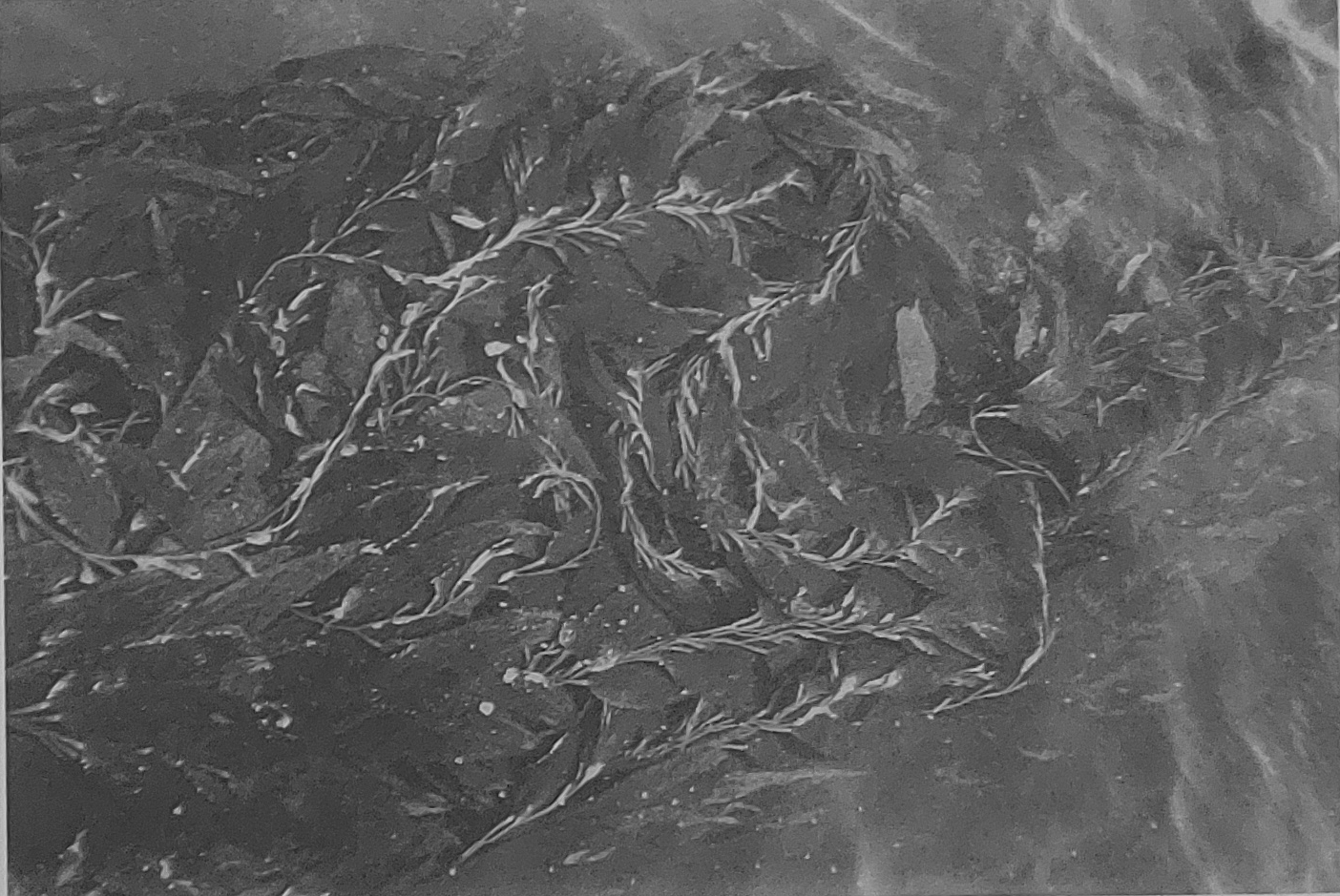

9.11 Kelp-bed, East Falkland 98

9.12 Desolate moorland, East Falkland 102

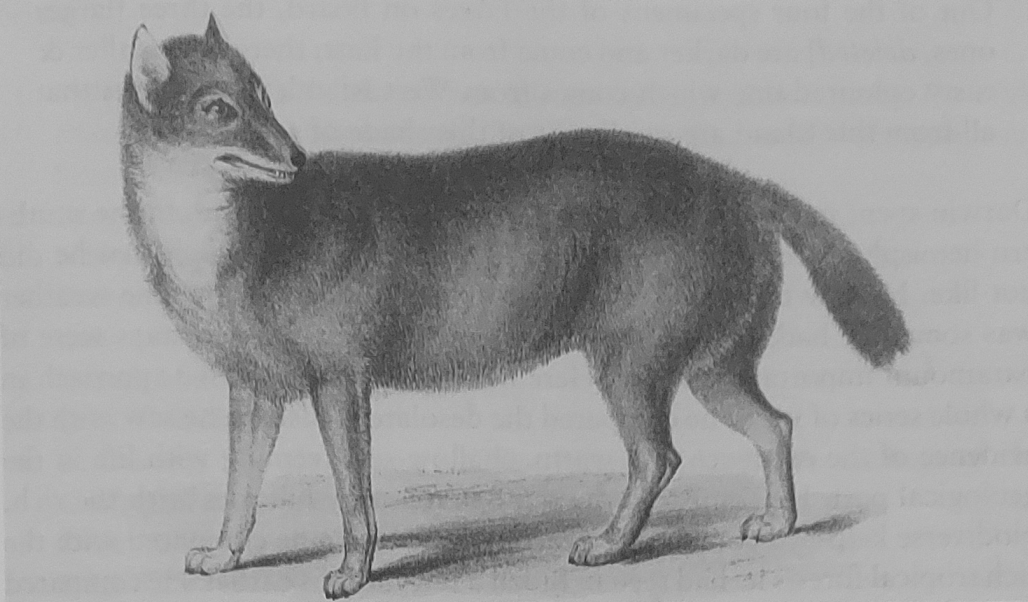

9.13 The Falklands fox or warrah 103

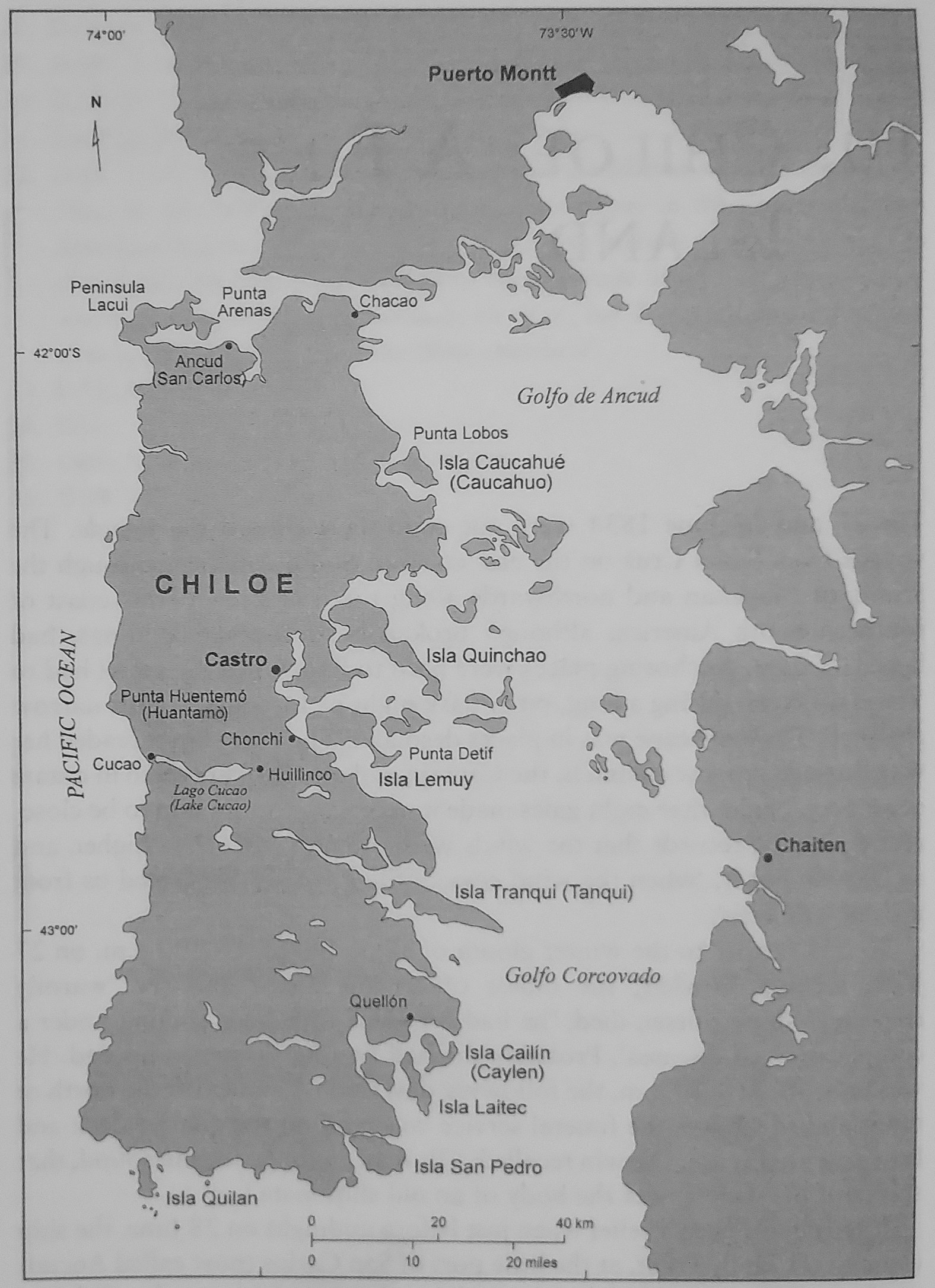

10.1 Map of Chiloe, showing some of the places mentioned in the text 108

10.2 Gunnera at Cucao, Chiloe 113

10.3 Temperate forest, Chiloe 115

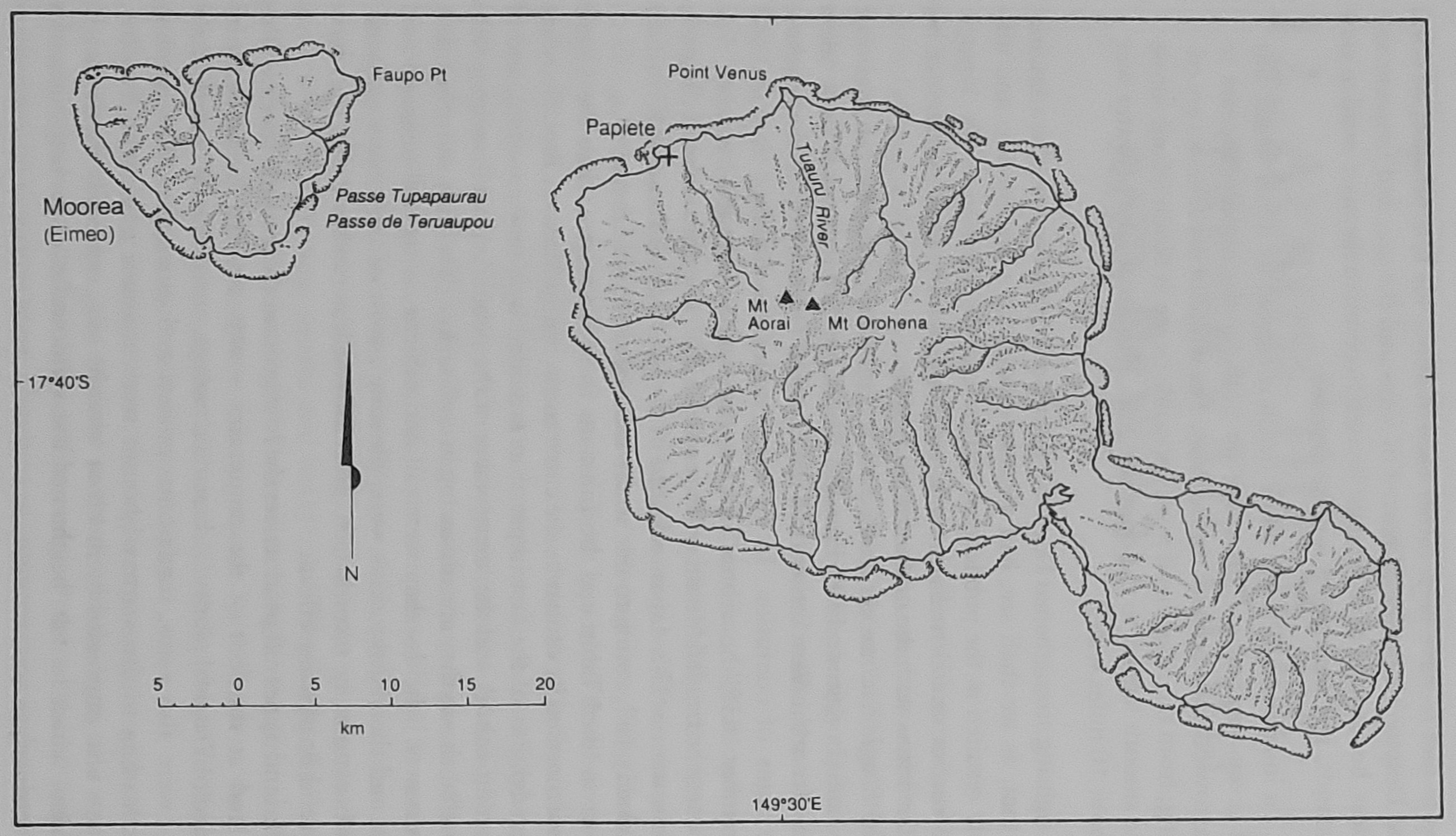

12.1 Map of Tahiti, showing valley of the River Tuauru, along which Darwin explored 140

12.2 Map of Tuauru Valley, Tahiti 141

12.3 Breadfruit still flourish in the gardens of Tahiti 142

12.4 Coast of Tahiti, from Point Venus 143

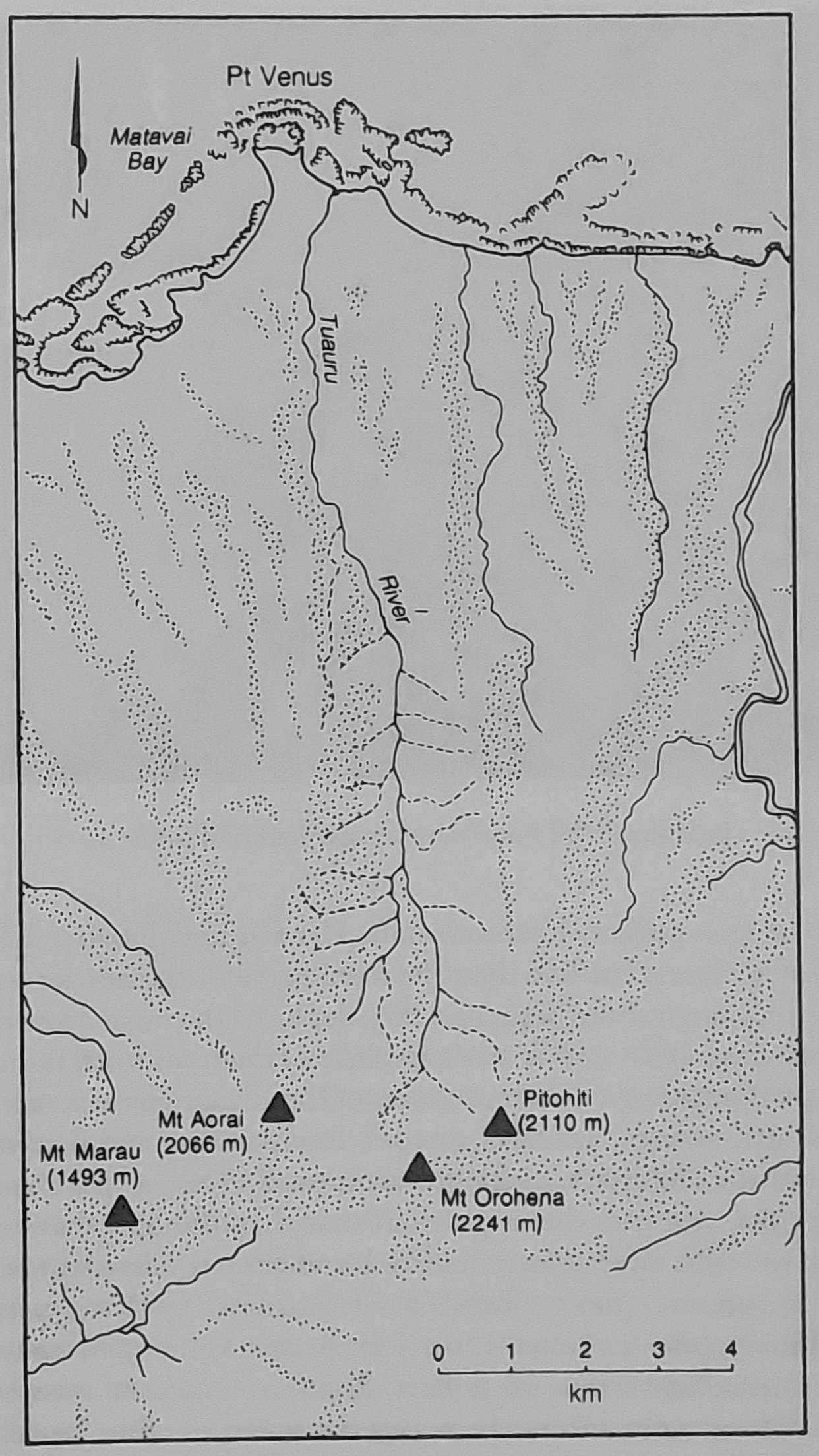

12.5 Darwin's theory of coral reefs: the transformation of a fringing reef into a barrier reef and ultimately an atoll, through the subsidence of an island or a rise in sea level 152

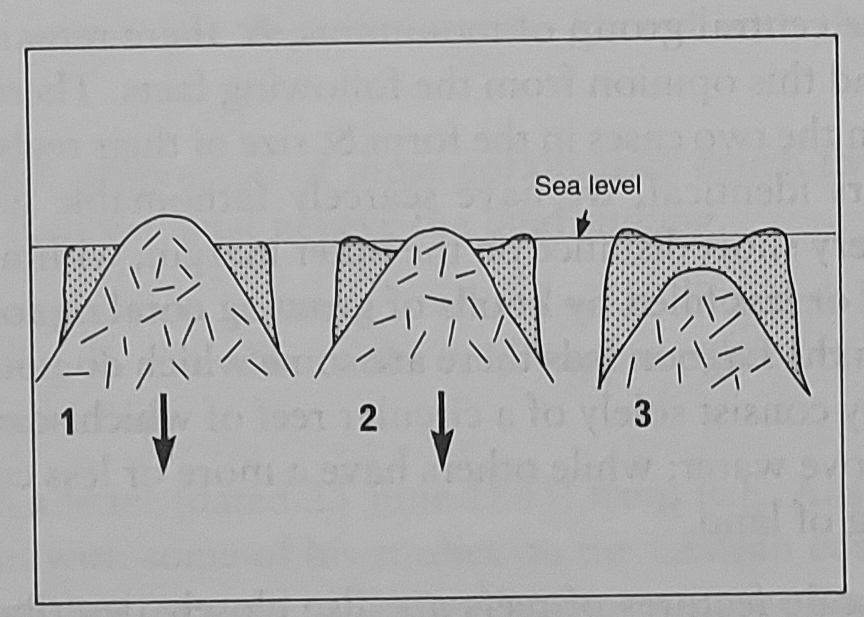

13.1 Map of the Bay of Islands area, North Island, New Zealand, showing places mentioned in the text and Darwin's route to Waimate mission 157

13.2 Haruru Falls 158

13.3 Kauri trees, North Island, New Zealand 158

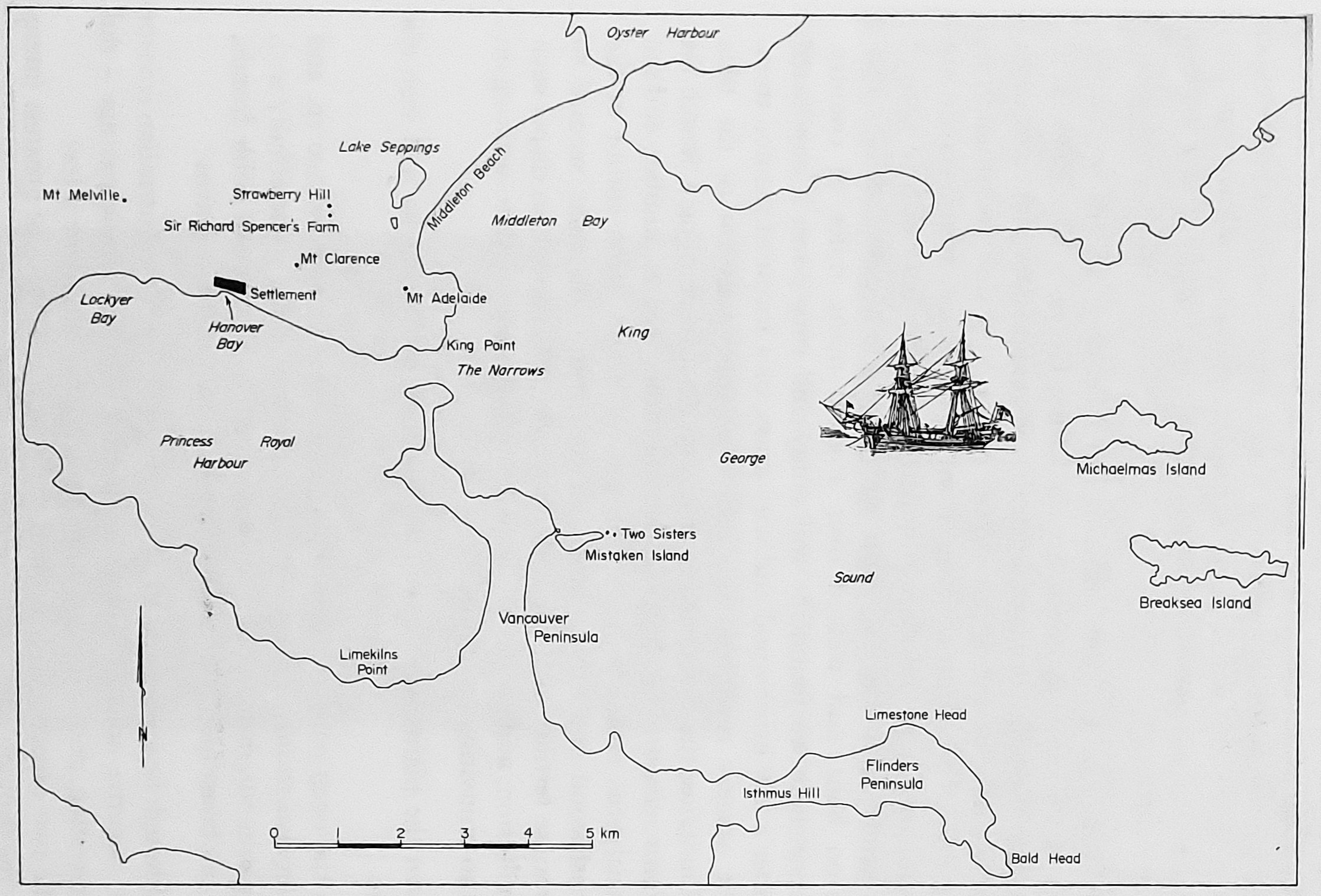

14.1 Map of King George's Sound, Western Australia 175

14.2 Dykes intruding into granite, shore of King George's Sound 177

14.3 Grass-tree (Kingia), King George's Sound 177

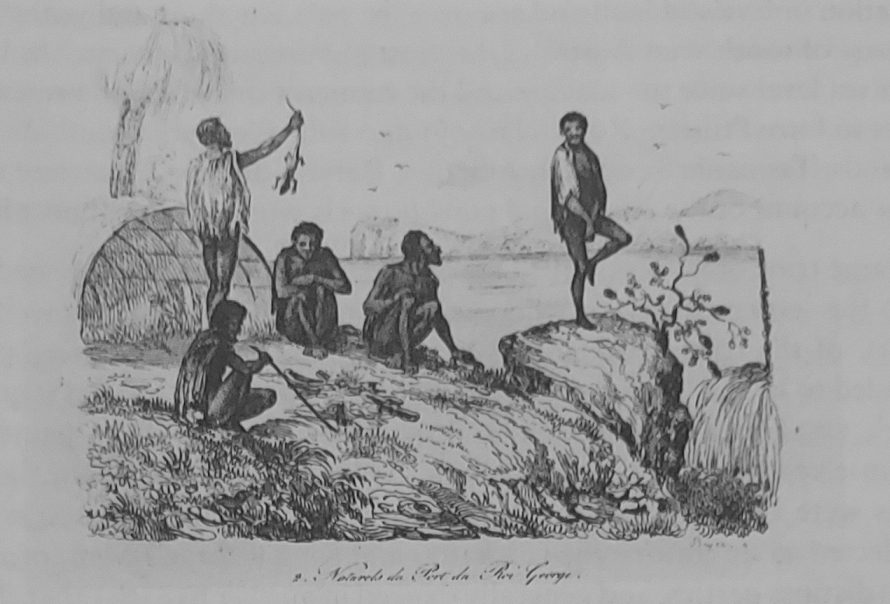

14.4 Aborigines, King George's Sound 180

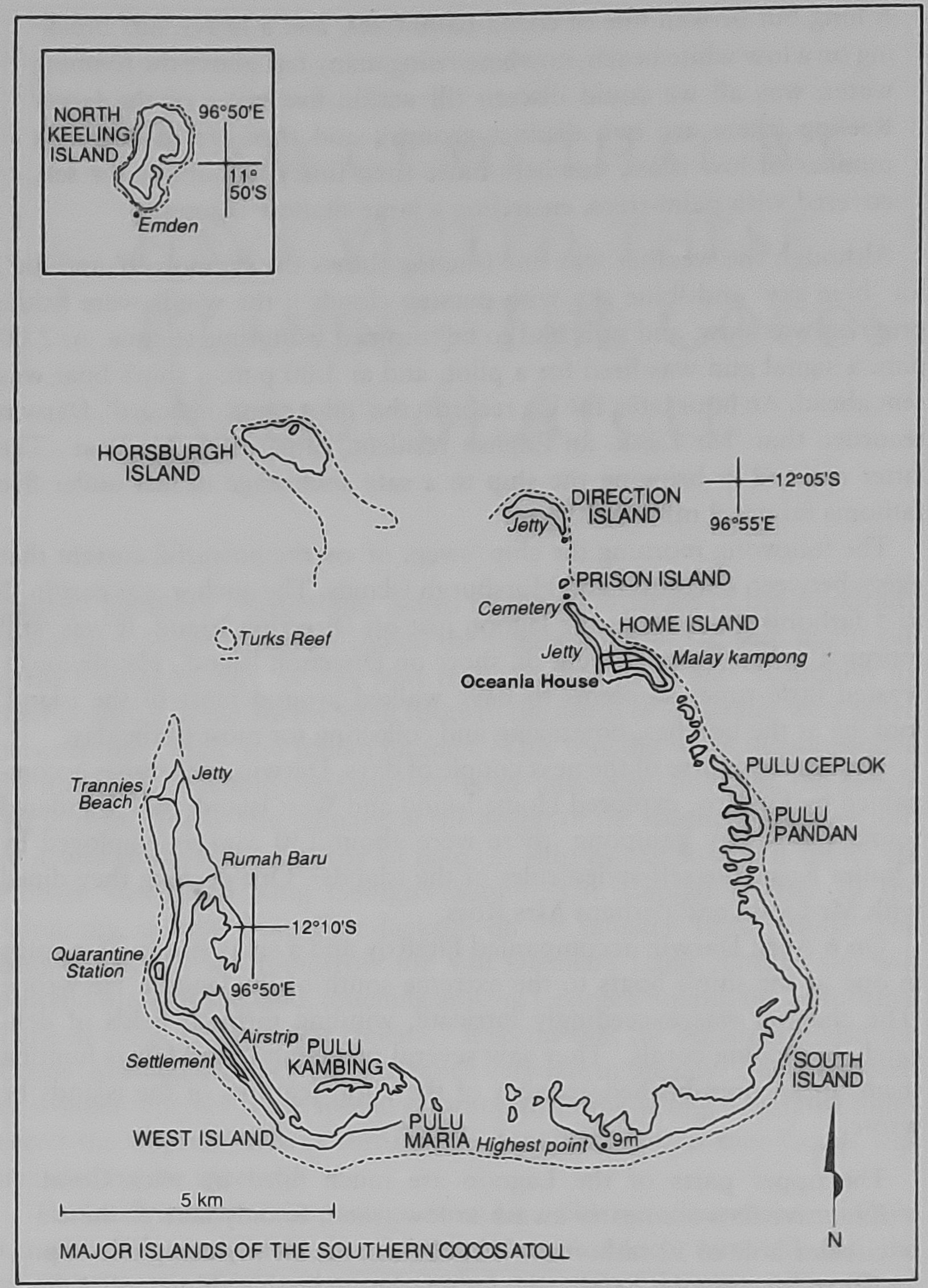

16.1 Map showing the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Indian Ocean 198

16.2 Exposed coast, West Island, Cocos 199

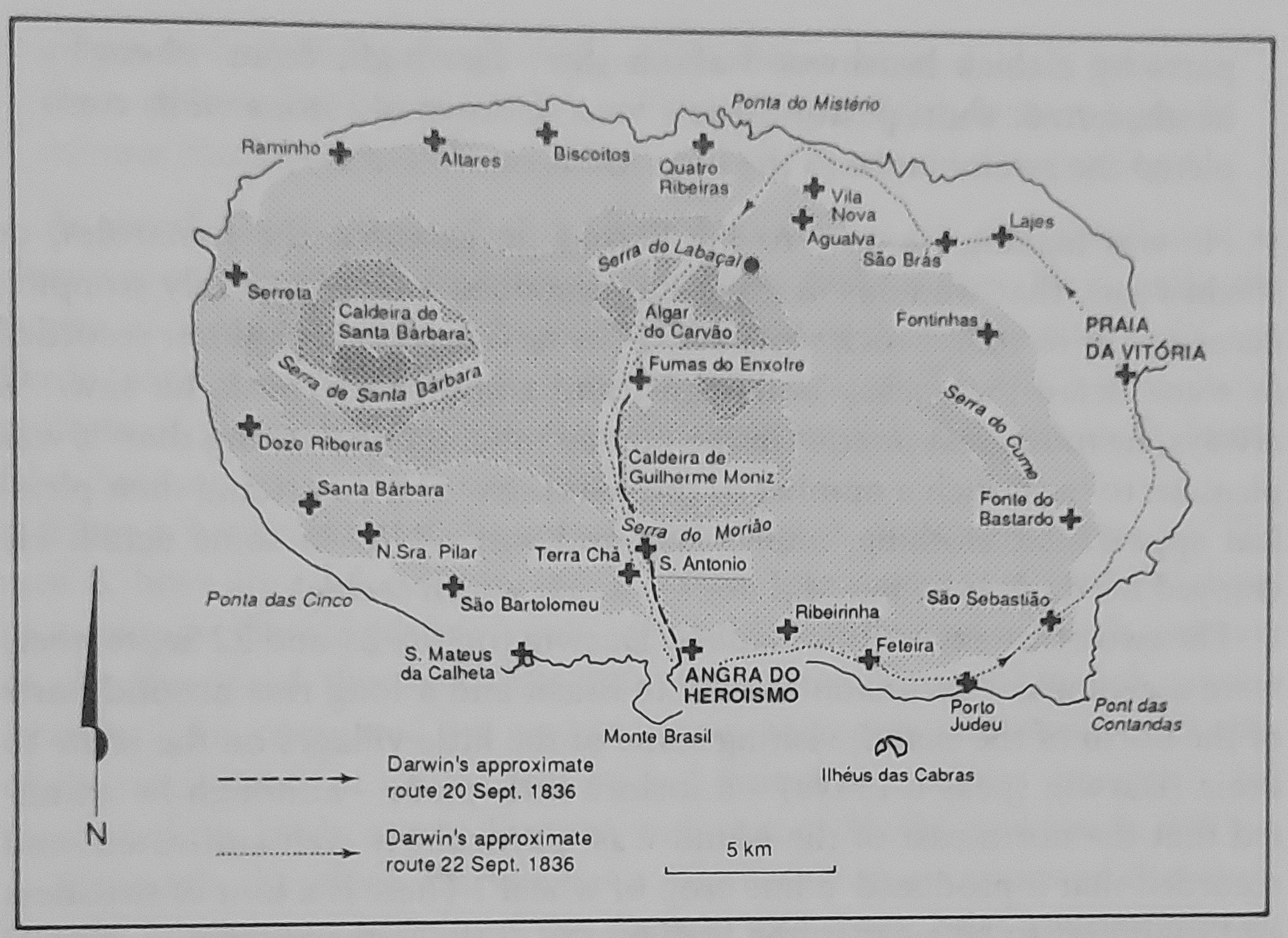

19.1 Map of Terceira, with Darwin's probable routes 235

19.2 Volcanic landscape, Terceira 238

Table 1 Darwin's theory of coral reefs 249

x

[page]

Chronology

1809 February

1825-27 1828-31

1828 August

December

1830 June

1831 August

December

1832 January

January-February February February-March December

1833 January-February

March-April 1833-34

Birth of Charles Robert Darwin, Shrewsbury

Medical training in Edinburgh

Studies at Christ's College, Cambridge; meets the Revd Professors John Henslow and Adam Sedgwick

Suicide of Captain Pringle Stokes, Commander of HMS Beagle, Tierra del Fuego

Robert FitzRoy assumes command of Beagle

HMS Beagle departs Tierra del Fuego with Fuegian hostages

Charles Darwin's geological excursion through North Wales with Professor

Sedgwick; received invitation to join HMS Beagle on a voyage around the world

Departure of Beagle from England

Abortive visit to Tenerife; landing prevented by quarantine restrictions

Visit to Cape Verde Islands

Visit to St Paul's Rocks

First landfall in South America; Bahia, Brazil

Beagle's return to Tierra del Fuego

Attempt by FitzRoy to establish mission

settlement at Woollya; exploration of Tierra del Fuego

First visit to Falkland Islands

Explorations of mainland South America

[page]

Chronology

1834 |

January-March |

|

March-April |

|

May-June |

|

June |

|

November- |

|

December |

1835 |

January |

|

January-February |

|

March-September |

|

September |

|

November |

|

December |

1836 |

January |

|

February |

|

March |

|

April |

|

April-May |

|

May |

|

July |

|

August |

|

August-September |

|

September |

|

October |

1837 |

March |

1839 |

January |

|

May |

1859 November 1882 April

Return to Woollya, Tierra del Fuego

Second visit to Falkland Islands

Passage through Magellan Strait

First visit to Chiloe

Second visit to Chiloe and surrounding islands

Cruising in Chonos Archipelago

Third visit to Chiloe

Exploration on mainland South America (west coast)

Visit to Galapagos Islands

Visit to Tahiti

Visit to Bay of Islands, New Zealand

Visit to New South Wales, Australia

Visit to Tasmania

Visit to King George's Sound, Western Australia

Visit to Cocos Islands, Indian Ocean

Visit to Mauritius, Indian Ocean

Visit to Cape of Good Hope; called on Sir John Herschel

Visits to St Helena and Ascension Island, Atlantic Ocean

Final call on South American mainland, Bahia, Brazil; completion of 'chain of meridians around the world'

Second visit to Cape Verde Islands

Visit to Terceira, Azores

Landfall at Falmouth, England; Darwin's return to Shrewsbury

Approximate date of Darwin's 'conversion' to an evolutionary outlook

Marriage to Emma Wedgwood

Publication of edited version of Darwin's Beagle diary as final part of Captain

FitzRoy's Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of the Beagle

Publication of On the Origin of Species

Death of Darwin at Downe, Kent; burial in Westminster Abbey

xu

[page]

Abbreviations

ADM

Autobiography

Correspondence

DAR

Diary

Geological Diary

Geology of the Voyage

Little Notebooks

Narrative

Admiralty archives, Public Record Office, Kew.

N. Barlow (ed.), The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, with the Original Omissions Restored (London: Collins, 1958).

F. Burkhardt and S. Smith, The Correspondence ofCharles Darwin, Vol. 1, 1821-1836 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Darwin archives, Cambridge University Library.

N. Barlow (ed.), Charles Darwin's Diary of the Voyage ofHMS 'Beagle' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1934; 1st edn, 1933).

Darwin's geological notes from the Beagle voyage, DAR 32-5.

C. R. Darwin, The Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle (London: Smith, Elder &c Co, 1842-46): Part

1, The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, 1842; Part 2, Geological Observations on VolcanicIslands, 1844; Part 3, Geological Observations onSouth America, 1846 (repr. London: William Pickering, 1986).

Darwin had many small leather-covered notebooks. These are at Downe House; microfilm copies are held in DAR, Cambridge University Library.

R. FitzRoy, Part 2 of Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure andBeagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describingtheir Examination of the Southern Shores of South

[page]

Abbreviations

Origin of Species

Red Notebook

Volcanic Islands Voyage

Zoological Diary

Zoology of the Voyage

America, and the Beagle's Circumnavigation of theGlobe (London: Henry Colburn, 1839). Part 1 was Captain King's account of the first voyage; Part 3 was Charles Darwin's original account.

C. R. Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of FavouredRaces in the Struggle for Life (London: John Murray, 1859).

S. Herbert (ed.), The Red Notebook of CharlesDarwin (London and Ithaca, NY: British Museum [Natural History] and Cornell University Press, 1980).

See Geology of the Voyage, Vol. 2.

C. R. Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle; originally published as Journal of Researches into the Geologyand Natural History of the various countries visited by H.M.S. 'Beagle', in FitzRoy, Narrative.

Darwin's zoological notes from the Beagle voyage, DAR 30-31

The Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle, 'edited and supervised by Charles Darwin' (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1840-43). Part 1, R. Owen, Fossil Mammalia; Part 2, G. R. Waterhouse, Mammalia; Part 3, J. Gould, Birds; Part 4, L. Jenyns, Fish; Part 5, T. Bell, Reptiles (repr. London: William Pickering, 1986).

xw

[page]

1. Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview

The first decades of the nineteenth century constituted the Great Age of British Hydrography. The empire was expanding. Although the American colonies had been lost following the War of Independence, Canada (British North America) remained loyal, and following 1788, when New South Wales was settled (partly as a dumping ground for convicts who could no longer be transported to America), expansion in Australasia accelerated. The other Australian colonies followed in brisk succession. Tasmania was first settled from New South Wales in 1803 and established as a separate colony in 1825. Victoria was settled from Tasmania in 1834, separating in 1855, and the first settlement in Western Australia, at King George's Sound was established (to forestall the French) in 1826, the Swan River Colony following in 1829. New Zealand had been claimed by Captain Cook in 1769-70, although organized British government did not follow for many decades. Meanwhile, the East India Company had established its first coastal settlements in 1609, expansion accelerating from 1757. The Company had also acquired staging posts, such as that of St Helena, settled in 1661, although that island did not come directly under the Crown until 1834. The defeat of Napoleon, and his confinement on that island, led to the occupation of the nearby islet of Ascension by the Royal Navy in 1815. Cape Colony was seized from the Dutch in 1795, and Mauritius, another useful staging post, was acquired from the French in 1810. And so on. Between 1783 and 1870, by conquest, settlement and treaty, there was a period of almost uninterrupted expansion, and with this expansion came trade; with international trade came the need for accurate charts. Thus it was, in early August of 1828, HMS Beagle, along with the Adventure and a small vessel purchased to assist with hydrographic survey,

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

the Adelaide, was examining the coasts around the southern tip of South America. The Beagle was then under the command of Captain Pringle Stokes. As the result of serious depression, brought on by the privations suffered through the terrible weather, Captain Stokes shot himself. Mortally wounded, he died in great pain on 12 August. The ship limped northwards to Rio de Janeiro to onload supplies and effect repairs. There, Admiral Otway, Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy's South American station, appointed the young Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy to command the Beagle, and survey work was resumed. Although much of this task was completed successfully (FitzRoy was a competent leader and a brilliant surveyor) there were difficulties; there were confusing magnetic anomalies and on one occasion, in late January 1830, one of the ship's boats was stolen, near Cape Desolation, Tierra del Fuego, by the local people. FitzRoy took hostages, hoping to exchange them for the boat. The plan was unsuccessful, for the inhabitants of these wild regions seemed disinclined to surrender the boat in exchange for their comrades, to whom the names Jemmy Button, Boat Memory and Fuegia Basket were given. Fuegia Basket was a young girl of about nine or ten, 'as broad as she was high'. Later, another young man, York Minster (after the island from whence he came, itself named for its alleged resemblance to the ecclesiastical building), was picked up.1

FitzRoy resolved to transport the extraordinary little group to England, where they were to be educated and then eventually returned. The Admiralty was not enthusiastic, but agreed not to interfere with FitzRoy's plans, to assist with the care of the Fuegians and afford them passage home. They were provided with medical care in the Royal Naval Hospital in Plymouth and then given schooling by the Reverend William Wilson, of Walthamstow (east of London). They became something of a curiosity and were presented to King William IV and Queen Adelaide.2

For a while it seemed as though their Lordships of the Admiralty might be reluctant to fulfil the bargain, to return the group - by now reduced to three in number, as Boat Memory had died of smallpox - to South America. Captain FitzRoy made plans to charter a vessel himself, at his own expense, but as the result of a certain amount of influence, for he was extremely well-connected, their Lordships were persuaded to allow the Beagle, under the command of Robert FitzRoy, to resume the survey, and for the Fuegians to be returned. They were to be accompanied by a Mr Richard Matthews, a missionary who was to attempt to start a mission colony in Tierra del Fuego. FitzRoy, as well as completing hydrographic charts of large parts of South America, was also charged with compiling 'a chain of meridians around the world'. Thus at every port of call he had to set up instruments in order to make navigational, astronomical and magnetic measurements.

2

[page]

Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview

One further incident should be recounted. In January 1830 Captain FitzRoy was surveying around the islets west of the main mass of Tierra del Fuego, attempting to explain the anomalies in his compass bearings. He formed the view that there might be magnetic rocks in some of the mountains of Tierra del Fuego, and regretted the fact that there was no one aboard the Beagle who knew much about geology or mineralogy. He resolved 'that if ever I left England again on a similar expedition, I would endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers and myself would attend to hydrography'.3

Thus the remote southern island of Tierra del Fuego has claims to be the trigger for the 1831-36 voyage of HMS Beagle, and also for Charles Darwin's presence on it. However, before we follow the young naturalist on his epoch-making voyage, perhaps it might be appropriate to review the early years of his life.

Charles Robert Darwin was born into a reasonably prosperous doctor's family in Shrewsbury on 11 February 1809.4 His father was Dr Robert Waring Darwin (1766-1848), himself the son of Erasmus Darwin (1733-1802; doctor, philosopher, poet, polymath). His mother was Susannah Darwin {nee Wedgwood); she died when Charles was eight and in later life he said he had little recollection of her. After a few years at a small school run by a Mr Case, the young Darwin went to Shrewsbury School, then in a chunky, several-storey stone building not too far from the modern centre of Shrewsbury.5 He did not perform particularly well academically, and left the school, not altogether unwillingly, at the age of sixteen. Thereafter, for a few months in the summer of 1825, he served as a sort of apprentice to his doctor father, helping with patients and the preparation of prescriptions, before he was dispatched to Edinburgh Medical School, where his elder brother (also called Erasmus Darwin) was completing his training. Although he attended a few rather unexciting lectures on geology there, made contact with the freethinking Dr Robert Grant, a specialist in the biology of sponges, and enjoyed fossicking along the coast of the Firth of Forth looking for seashore life, he detested the medical training itself. The sight of operations (performed, of course, without anaesthetic) appalled him, and after a couple years he left, unqualified. His father was not impressed; but it was decided that although it was rather outside the tradition of the family, he might make a Church of England parson; he was therefore sent to Christ's College Cambridge to take a general degree in Arts. There a modest amount of theology, philosophy, mathematics and New Testament Greek was studied, good food eaten, wine consumed and friends made. (It does not take too much imagination to know what membership of the 'Glutton Club' involved!) In 1831 he graduated as a Bachelor of

3

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

Arts. Particularly important influences in Cambridge days were his friendships with the young don, the Revd John Stevens Henslow, Professor of Botany, with whom he used to go for botanizing walks into the Cambridgeshire countryside,6 and with the Revd Adam Sedgwick, the Professor of Geology. Both encouraged his interest in natural history. In the summer of 1831 Sedgwick took the young Darwin on a geological expedition. In his autobiography Darwin recalled the incident as follows:

As I had come up to Cambridge at Christmas, I was forced to keep two terms after passing my final examination, at the commencement of 1831; and Henslow then persuaded me to begin the study of geology. Therefore on my return to Shropshire I examined sections and coloured a map of parts round Shrewsbury. Professor Sedgwick in the beginning of August intended to visit North Wales to pursue his famous geological investigation amongst the older rocks, and Henslow asked him to allow me to accompany him. Accordingly he came and slept in my Father's house . . .

Next morning we started for Llangollen, Conway, Bangor and Capel Curig. This tour was of decided use in teaching me a little how to make out the geology of a country. Sedgwick often sent me on a line parallel to his, telling me to bring back specimens of the rocks and to mark the stratification on a map. I have little doubt that he did this for my own good, as I was too ignorant to have aided him... At Capel Curig I left Sedgwick and went in a straight line by compass and map across the mountains to Barmouth, never following any track unless it coincided with my course. I thus came on some strange wild places and enjoyed much this manner of travelling.7

In his explorations during the Beagle voyage Darwin used almost every aspect of what he had learned from Sedgwick and what he had taught himself that summer in the Welsh Borderland and North Wales. These included the direct transect-line across country, the inspection of sections and exposures, the marking of stratification on a map, the collection of rock specimens, the use of clinometer (an instrument for measuring the dip of strata) and compass. Darwin regretted his 'incapacity to draw', and certainly some of his geological cross-section drawings and sketch-maps are a little crude. They are, however, adequate, and it is quite clear that he had the knack of 'making out the geology of a country' in three dimensions. He had good cause to write to Henslow on 11 April 1833, just after he had left the Falklands, asking him to tell Professor Sedgwick that he had 'never ceased to be thankful for that short tour in Wales'.8

Charles returned to Shrewsbury from the Welsh excursion to find a letter

4

[page]

Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview

from Henslow suggesting that he might be interested in accompanying Captain FitzRoy on the Beagle voyage as a 'supernumerary'. Dr Darwin initially was not in favour, but with the help of friends Charles managed to swing him round. An interview with FitzRoy in London followed. The next few months were spent in a frantic round of assembling equipment and materials for the voyage, and obtaining instruction in the best methods of preparing specimens. As well as his geological hammer, clinometer and compass, Darwin had with him on the ship several guns (for taking birds and mammals), an anaeroid barometer (for estimating heights of mountains), a telescope and microscope. He had several nets, including at least one 'sweep-net' for taking terrestrial insects, and others for catching aquatic life. He records in his notes that he took some of his fish specimens 'on hook' so he may have had other fishing equipment. He would have had to acquire a large number of containers for storing specimens, and dissecting instruments and materials for skinning and preserving them. Many fish, reptiles, some birds and insects he preserved in 'spirits of wine'; while some stores were replenished en route, presumably substantial quantities of spirits and other chemicals were taken aboard before the ship left.9 For the last few weeks before the ship departed, the enthusiastic Charles was in residence at Plymouth, supervising the taking aboard of some of his supplies.

There were delays due to poor weather, and other difficulties, and indeed a couple of false starts, but on 27 December 1832 the Beagle departed on her voyage around the world. Darwin, FitzRoy and one or two others had had a good lunch with local naval bigwigs before they left and the young naturalist blamed 'mutton chops and champagne' for the absence of sentiment he felt on leaving his native land on his great adventure.

From Devonport the ship proceeded, after a brief hesitation at Tenerife, to the Cape Verde Islands, off the African coast (January 1832), and from thence to St Paul's Rocks and Fernando Noronha, tiny islets in the South Atlantic (February 1832). At these, and at many other islands and ports visited, Captain FitzRoy's task was to establish their position very precisely. He had over 20 chronometers to assist him to determine longitude accurately. From St Paul's and Fernando Noronha the Beagle proceeded to the mainland of South America, where the main programme of hydrographic survey commenced. The first islands accurately surveyed were the Abrolhos, off the coast of Brazil (March 1832). There were then surveys along the coast of Patagonia. A detailed survey of Tierra del Fuego followed, providing FitzRoy with the opportunity of completing his commitment to the Fuegians to return them to their home (December 1832-February 1833). Visits to the Falklands (March/April 1833 and 1834) alternated with the visits to Tierra del Fuego. Eventually, in mid-1834 the Magellan Strait,

5

[page]

Figure 1.1 Map to show the approximate route of HMS Beagle (1831-36), and positions of some of the islands visited

[page]

Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview

between Tierra del Fuego and the South American mainland, was traversed, and the expedition set out northwards, to Chiloe (visited three times in 1834 and 1835), and the scattering of islands that constitute the Chonos Archipelago. Surveys along the coast of Chile and Peru allowed Darwin the opportunity of making a number of excursions inland in South America. In September 1835 the Beagle set out across the Pacific, calling first, as is well known, at the Galapagos Islands (September-October 1835), which, as we shall see, Charles Darwin did not particularly like. Then followed the longest leg of the entire voyage, to Tahiti (November 1835); this allowed Darwin to glimpse several coral atolls from afar. Tahiti, especially the missionaries working there, left positive images in his mind, and he was sorry to leave. New Zealand (Christmas 1835), where again he was impressed by the work of missionaries, he liked less. Australia, with its brashness, the convicts and the dry, stark landscape, was not a great deal to be preferred, although some of the observations he made there were important (New South Wales, January 1836; King George's Sound, March): he preferred green, mild Tasmania (February 1836).

From Australia, perhaps because of some change of plans at a late stage, FitzRoy decided to go to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean; he had been instructed to 'fix their position' if possible (April 1836). Darwin enjoyed his time there as much as he had disliked New South Wales and Western Australia: they were also very important to him in the development of his 'theory of coral reefs'. A short 'dissipated' visit to Mauritius (April-May 1836) was followed by a brief sojourn at the Cape of Good Hope: Madagascar may have been glimpsed from afar.

Back in the Atlantic, there were visits to St Helena and Ascension (July 1836), and then to 'complete the chain of meridians', Bahia in Brazil was visited once again (August). Another return visit, to the Cape Verdes, was followed by a very few days at Terceira in the Azores (September 1836) before Falmouth in Cornwall was gained on 2 October 1836.

Thus Darwin had the opportunity of examining as well as South American, and, much more briefly, African environments (outside the scope of this book), islands in the Atlantic (north and south), Pacific and Indian Oceans. He experienced the large island continent of Australia and tiny St Paul's. He explored volcanic islands (St Helena, Ascension, Fernando Noronha, Terceira) and coral atolls (Cocos), and composites (Mauritius, Tahiti). Chiloe, Tierra del Fuego and the Chonos group are of continental rocks, and so different again. The Falklands are sub-antarctic in climate; Cocos, Tahiti and Mauritius are tropical. St Jago in the Cape Verdes has some characteristics of a 'desert island'. Some were inhabited; some were devoid of human habitation. The range was enormous: Darwin

7

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

was interested in them all. Almost all in some way contributed to the development of his ideas.

It is perhaps appropriate at this point very briefly to document the written sources that allow Darwin's voyage, his activities, and even his thoughts, to be reconstructed in some detail. First his diary or journal; this was published in more or less its original form, edited by his granddaughter, Norah Barlow, in 1933.10 (There are other editions, but this is the best known.) Darwin edited, and considerably improved the style of this, and it became part 3 of the Narrative of the Surveying Voyages.11 Later versions, after further slight revision, are generally titled The Voyage of the Beagle. There are also his letters - those he wrote to his family and friends and those he received. Some of these have been lost. Some of the letters are, with other Darwin materials, deposited by the family in the Darwin Archive in the Manuscript Collection in Cambridge University Library (they are indicated here by the abbreviation DAR). Letters written by Darwin are scattered all over the world, although many are in Cambridge. Known Darwin letters have been published in the impressive Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Volume 1 of which has those from the Beagle period.12 He also kept separate Zoological and Geological Diaries, many parts of which are unpublished; these are in Cambridge, along with lists of specimens. There was also a series of 'little note books', perhaps used in the field, or for single ideas or references. The most famous of these is the Red Note Book 'RN', in which the first evolutionary thoughts were put to paper (after the return to England, although the notebook was opened during the voyage).13 Captain FitzRoy kept a diary, one that formed the basis of Volume 2 of the Narrative of the Surveying Voyages. The young man who became Darwin's servant part-way through the voyage, Syms Covington, also kept a diary, now held by the Mitchell Library, Sydney, New South Wales. The official log of the Beagle is available at the Public Record Office at Kew, along with certain other Admiralty documents relating to the voyage. Some of FitzRoy's manuscript charts, other notes and manuscripts are in the Hydrographic Department Office in Taunton, Somerset. From the time of his return to Britain (indeed from slightly before) Darwin was publishing papers and articles, in scientific journals and elsewhere. The most important publications from the voyage were The Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle (in five volumes)14 and The Geology of the Voyage (in three volumes, on Coral Reefs, Volcanic Islands and The Geology of South America).15

All the above (and other primary and secondary sources) were consulted during the research on which this book is based. I have also been privileged to visit a number of the islands that the Beagle visited, and these landscapes,

8

[page]

Introduction: The Origins of the Darwin Voyage, and an Overview

much changed as some of them are, can also be regarded as part of the archival sources of the voyage.

My purpose is to show that there was more to the Beagle voyage than the Galapagos Islands. The visit to the Galapagos was significant; it was, however, just one incident on a journey, one bead on the thread. The thread stretched around the world, and linked dozens of islands. It was Darwin's ability to observe and to compare these islands, from an early stage in the voyage, and to arrange the information he collected around a limited number of conceptual frameworks, that transformed a routine survey expedition into one of the most significant voyages of all time.

Notes

1. Robert FitzRoy, Part 2 of Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle's Circumnavigation of the Globe (London: Henry Colburn, 1839). Part 1 was Captain King's account of the first voyage; Part 3 was Charles Darwin's account. Hereafter in these notes, FitzRoy's memoir will be referred to as Narrative.

2. An account of the whole affair is given in N. Halewood, Savage: The Life and Times of Jemmy Button (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2000). A summary appears in R. Keynes, Fossils, Finches and Fuegians (London: HarperCollins, 2002). See also P. Nichols, Evolution's Captain (New York and London: HarperCollins, 2003).

3. Fitzroy, Narrative, page xi

4. The Darwin home at The Mount is still there; a rather austere redbrick building, now housing the local income tax office.

5. The building is now the Shrewsbury Public Library. The modern school, with a statue of its most famous son in a prominent position (Galapagos iguanas at his feet), is on the outskirts of the old city.

6. The young Cambridge Darwin became known as 'The man who walks with Henslow'.

7. N. Barlow (ed.), The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, with the Original Omissions Restored (London: Collins, 1958), pp. 68-71.

8. Original at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. See F. Burkhard and S. Smith, The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Vol. 1, 1821-36 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 308.

9. An account of Darwin's specimens and what became of them is given in D. M. Porter, 'The Beagle Collector and His Collections', in D. Kohn, The Darwinian Heritage (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985), pp. 973-1019.

9

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

Darwin improvised a good deal in collecting during the voyage: for example, he had prepared a net made out of bunting for trailing behind the ship to collect planktonic life.

10. N. Barlow (ed.), Charles Darwin's Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. 'Beagle' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1933). Referred to here as the Diary.

11. Darwin's account will be referred to in these notes as Voyage.

12. F. Burkhardt and S. Smith, The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Vol. 1, 1821-1836 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). (Hereafter Correspondence.)

13. S. Herbert (ed.), The Red Notebook of Charles Darwin (London and Ithaca, NY: British Museum [Natural History] and Cornell University Press, 1980).

14. The Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle, 'edited and supervised by Charles Darwin' (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1840-43): Part 1, R. Owen, Fossil Mammalia; Part 2, G. R. Waterhouse, Mammalia; Part 3, J. Gould, Birds; Part 4, L. Jenyns, Fish; Part 5, T. Bell, Reptiles (repr. London: William Pickering, 1986). (Hereafter Zoology of the Voyage.)

15. C. R. Darwin, The Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle (London: Smith, Elder & Co.): Part 1, The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, 1842; Part 2, Geological Observations on Volcanic Islands, 1844; Part 3, Geological Observations in South America, 1836 (repr. London: William Pickering, 1986).

There are a number of websites devoted to the life and work of Charles Darwin.

The Darwin Correspondence Project can be accessed through www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Departments/Darwin

Syms Covington's diary is at www.asap.unimelb.edu.au/bsparcs/covingto/contents.htm

10

[page]

2. Darwin's Islands in Context

[A]s a number of isolated facts soon becomes uninteresting, the habit of comparison leads to generalization . . -1

[T]he zoology of Archipelagoes will be well worth examining.2

These two quotations go a long way towards an explanation of the success of Charles Robert Darwin. The first was written in his diary at the very end of the voyage, between HMS Beagle's brief visit to Terceira in the Azores (19-23 September 1836) and the little ship's berthing in Falmouth (2 October), in a few pages of recollection and reflection, in which he summarized his conclusions from and feelings about the voyage as a whole. The second was written in his notes concerning the Galapagos Islands. He had noticed that the islands were 'possessed of but a scanty stock of animals', and that there were similarities between the biota of the various islands 'in sight of each other', but also significant differences.

These two themes, the comparative approach and a fascination with remote islands, run through the entire corpus of Darwin's writings from the Beagle period and through the thinking that gave rise to them. The twin themes are interconnected. Darwin was fortunate enough to visit some 40 islands, possibly more (in a very few cases it is difficult from his notes and other documents that survive from the voyage to be absolutely sure whether he landed on a particular islet or simply viewed it from offshore), and it is perhaps unsurprising that he often compared them. But there was more to it than that. Darwin's notes show the comparative approach ran very deep. Not only was he constantly comparing his observations on one island with those from another, and these with impressions of continental (non-island) environments, but he was constantly comparing his own ideas with those

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

of others. The Beagle cabin was filled with books - the accounts of the great voyagers of the past.3 He was self-critical too, and time and again reread his notes, revising, and sometimes completely rewriting them as new information came to hand: in this way he compared his ideas of one time and place with those of another. Darwin's notes from the voyage, and from later decades, have largely been retained in the order in which he left them, and thus the modern enquirer is able to trace the route of his developing ideas, as well his route across the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Darwin may have learned this comparative approach, in part at least, from his reading of John HerschePs Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy in his last year at Christ's College, Cambridge. The laws of nature had to be established by testing a hypothesis again and again under a variety of conditions. The following passage was marked in Darwin's copy of Herschel's little book, still preserved in the Darwin Collection in the University Library, Cambridge.

It is in precise proportion that a law once obtained endures this extreme severity of trial, that its value and importance are to be estimated; and our next step must therefore consist in extending its application to cases not originally contemplated; in studiously varying the circumstances under which our causes exist, with a view to ascertain whether their effect is general; and in pushing the application of our laws to extreme cases.4

In the case of the experimental sciences - physics, chemistry and to some extent biology - one could repeat an experiment again and again, and Charles Darwin quite frequently did this. In the case of the field sciences -geology, geography and ecology, and although Darwin did not use this word, he applied its concepts - one had to make use of 'nature's experiments' and 'natural laboratories', by examining analogous phenomena repeatedly under different environments: in other words by using the comparative method. The many islands Darwin visited lent themselves to this comparative treatment: each one is a unique 'natural experiment'; whereas the number of continents can be counted on one hand (or two if one separates North from South America and Europe from Asia). Here is an example. Darwin is comparing the volcanic rocks and land-forms at the last island group he visited, the Azores, with those of islands he had visited earlier in the voyage.

The degree of [volcanic] activity about equal to the Galapagos, & Cape Verd & Canary . . .

. . . lavas of a smooth texture, of a blackish colour with crystals of glassy felspar [sic] similar to some on James Is.

12

[page]

Darwin's Islands in Context

Both these islands [i.e. Terceira and Sao Miguel] in their general form, number of craters, few scattered mounds, Lithological nature of the rocks ... degree of activity, general dimensions appear very closely to agree with the Galapagos Archipelago.5

From comparisons such as these, theories emerged, as we shall see. Charles Darwin was forever searching for the vera causa, the underlying cause of a phenomenon, rather than the immediate, short-term explanation. He was trying to see the 'big picture'. Here he is, still in the reflective mood that characterizes the last few pages of his diary: he is again preoccupied with the nature, relationships and size of islands. It should be remembered that he was writing while parts of the world map were still far from clear.

There are several. . . sources of enjoyment in a long voyage . . . The map of the world ceases to be a blank; it becomes a picture full of the most varied and animated figures. Each part assumes its true dimensions: large continents are not looked at in the light of islands, or islands considered as mere specks, which in truth are larger than many kingdoms of Europe.6

On the other hand, as well as seeing, or at least seeking, the 'grand design', the young naturalist had a fine eye for detail. He was immensely curious, he wanted to know. He wanted to see what was the other side of the mountain, what a particular organism looked like under a microscope (he had a small Bancks microscope with him on the Beagle) and what were the physical effects of a sea-creature's sting on a human. Such a curiosity was linked to excellent powers of observation. Here is a quotation from his zoological notebook on a type of coral from the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean.

1836 April Keeling Is.

Madrepora 3560 This stony branching elegant coral is very abundant in the shallow still waters of the lagoon: it lives in the ... parts which are always covered by water to a depth of 15 ft & perhaps more. Its color [sic] is nearly white or pale brown. The orifice is either nearly simple or protected by a strong hood; the polypus is similar in both. The upper extremity or mouth of the polypus is attached to the edge of the orifice: it cannot be drawn back out of sight; it consists of a narrow fleshy lip which is divided into 12 tentacula or subdivisions of the lip. These tentacula are very short & minute &c are flattened vertically; are brown colored, tipped with white. The animal possesses very little irritability on being pricked, the mouth is folded into an elongate figure & partially drawn back. The body of the polypus fills

13

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

up the cell & is so excessively delicate transparent & adhesive, that I in vain tried to examine its structure. I could see a sort of abdominal sack & attached to the side of this were intestinal folds of a whitish color. These when separated from the body possessed a sort of peristaltic motion. I examined the Madrepora (3584) also common in the lagoon & found the same sort of polypus & from a shorter examination I believe such will be likewise found in kinds (3612, 3586).7

The passage is in many ways typical. It reveals Darwin's attention to detail and his very careful observation at both the macroscopic and microscopic level. He compares several different forms. He also comments on the organism's behaviour (or at least its irritability): a feature of Darwin's work was his interest in the behaviour of organisms - he was paying attention to this at a time when the science of ethology, the scientific study of the behaviour of animals, was still in the future.

This close attention to detail and powerful skill in observation was no doubt partly innate; inklings of it can be seen in his enthusiasm for natural history and in particular for the collection of beetles, not one of the most conspicuous groups of organisms, in the Shropshire countryside of his boyhood. It was probably fostered by his medical training, gained both in the brief time he assisted his father with patients and in the two unfortunate years of medical training in Edinburgh. At Edinburgh Medical School, despite the boredom of the lectures and the horrific operations (one on a child), he probably picked up some skill in detailed observation and also curiosity about his fellow humans. Here is one place where the medical training shines through in the writings of the medecin manque; Darwin is still on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and still examining corals, comparing a branched and a plate-like form of 'Millepora':

They ... agree in the very remarkable property, hitherto unnoticed in such productions, of producing on contact a stinging sensation . . . The power appears to be, very generally speaking, on pressing or rubbing a fragment [of the plate kind] on tender skin of the face or arm, a pricking sensation will be felt after the interval of a second, which lasts a very short time. But on rapidly touching with the specimen (3609) of the branching kind the side of the face the pain was instantaneous, but increased as usual after a short interval; the sensation continued strong for a few minutes but was perceptible half an hour afterwards. The sensation was as bad as a sting of a Physa.8 -On touching the tender skin of the arm, red spots were produced, & which had the appearance, if the stimulation had been a little stronger of producing watery pustules.9

14

[page]

Darwin's Islands in Context

Here again one may note the firm comparative treatment and the exceptionally fine level of detailed observation. But the experimental approach, the detailed notes on sensations, their duration and intensity, and the use of terms such as 'pustules', seem to reflect the days of medical training. So too some of his observations on the physiognomy and appearance of some of his fellow humans. He commented in detail on the light-coloured skin, short stature and the shape of the temple and cheekbones of the 'Hottentots, or Hodmadods' of Cape Colony, which 'project so much that the whole face is hidden from a person standing in the same side position, in which he would be enabled to see part of the features of a Europaean [s/c]'.10 He makes comparable observations on the detailed appearance of the Indian convicts he encountered on the island of Mauritius; of one unfortunate individual, perhaps recalling patients he had seen in Edinburgh, he wrote: '[TJhis poor man was remarkable as being a confirmed opium eater, of which fact his emaciated body & strange drowsy expression bore witness.'11

There is yet another characteristic of Darwin's observations and comments on island (and other) environments: they are remarkably integrative. Here is his account of the island of Terceira in the Azores:

The island is moderately lofty & has a rounded outline with detached conical hills of volcanic origin. The land is well cultivated, & is divided into a multitude of rectangular fields by stone walls, extending from the water's edge to high up on the central hills. There are few or no trees, & the yellow stubble land at this time of year gives a burnt up & unpleasant character to the scenery. Small hamlets & single white-washed houses are scattered in all parts.12

Darwin conveys the essential 'feel' of a landscape vividly and yet with economy. He appreciates that what he sees is the result of the subtle interplay of human activities and the biophysical landscape. He was quite happy to allow his own appraisal to intrude on objective description; he frequently made clear in his writings what he regarded as an attractive view: the fields are well cultivated, but the burned-up stubble had given the landscape an unpleasant appearance - views that to some extent reflected upper-middle-class English tastes of his day.

In the final few pages of The Voyage of the Beagle he wrote:

. . . there is a growing pleasure in comparing the character of the scenery of different countries, which to a certain degree is distinct from admiring its beauty. It depends chiefly on an acquaintance with the individual parts of each view: I am strongly induced to believe that, as in music, the person who understands every note will, if he

IS

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

also possesses a proper taste, more thoroughly enjoy the whole, so he who examines each part of a fine view may also thoroughly comprehend the full and combined effect.13

He goes on to say how a landscape may be analysed in terms of geology: 'great masses of naked rocks . . . afford a sublime spectacle', and botany, for in many views 'plants form the chief embellishment'. His approach is both analytical, in attempting to see how the components of an environment relate to one another, and integrative, showing how a whole system worked. He applied this twofold approach to humanized or cultural landscapes and to wild places, to the grand vistas and to the tiny details of nature. On East Falkland, in April 1834 he wrote of the flightless steamer-duck (Tachyeres pteneres), a distinctive element of the local avifauna:

A logger-headed duck called by former navigators .. . race-horses, &C now steamers has been described from its extraordinary manner of splashing & paddling along: they here abound in large flocks; In the evening when preening themselves make the very same mixture of noises which bull-frogs do in the Tropics: their head is remarkably strong (my big geological hammer can hardly break it) & their beak likewise; this must fit them well for their mode of subsistence: which from their dung must chiefly be shell-fish obtained at low water & from kelp - They can dive but little, are very tenacious to life, so as to be (as all our sportsmen experienced) very difficult to kill; They build amongst bushes & grass near the sea.14

The account mentions several aspects of behaviour; but it is rather more than a straightforward account of 'exquisite adaptation' - a phrase often used by Darwin - to which notes on voice, nesting and locomotion have been added. Here is an account - imperfect perhaps, but nevertheless far ahead of its day - that aims to show how the steamer duck slotted into its habitat, and which reveals an understanding of how morphology, behaviour, food supply and habitat are related to each other. The heavy head and bill 'fit them well for their mode of subsistence'; the ducks seldom dive but 'feed from shell-fish obtained at low water & from kelp'; they are strongly social and 'abound in large flocks', and thus are very vocal, with a vigorous 'splashing' display. Darwin does not actually suggest that their 'remarkably strong head', the tenaciousness with which they hold to life, and flocking behaviour might to some extent compensate for flightlessness, but the account shows what might now be called ecological awareness, and the integrative pattern in the way in which he recorded his observations.

It can be seen in this brief preliminary overview of some of Darwin's island

16

[page]

Darwin's Islands in Context

experiences that the great Victorian naturalist had a very distinctive way of accumulating, recording and processing his information. He had an extraordinary eye for detail, developed partly perhaps from his medical training, partly from his natural history excursions into the Shropshire and East Anglian countryside. Yet at the same time he looked for the overall pattern, the way in which the part fitted with the whole, and attempted to seek relationships and causes, indeed 'natural laws'. His approach was thus analytic, yet integrative. In this search for pattern he was enormously assisted by 'the habit of comparison' (from Herschel) and a fascination with islands.

A brief note on the nature of islands is perhaps apposite. They can, very broadly, be assigned to two categories. Continental islands are those that, perhaps some time in the geological past, have been parts of the world's continents. Such islands are made up of rocks that form in, on or close to continents such as granites, folded and metamorphosed rocks (i.e. those that have been affected by heat or pressure) such as slates, and sedimentary rocks such as sandstones. These last are assumed to have formed in shallow seas on the margins of continents, or occasionally under desert conditions. Separation of such an island from its parent continent may have occurred within the last few thousand years as the result of the rise in sea level that accompanied the melting of the ice sheets that covered large parts of continents during the last Ice Age, or minor local earth movement. Examples include (as well as Britain and Ireland), Tasmania, Tierra del Fuego and Chiloe, off the Chilean coast. Alternatively, a fragment of a continent may have broken away from a larger land mass as the result of the movement of the plates that make up the earth's crust. Today it is believed that these plates have moved in relation to one another throughout geological time, as the result of convectional currents deep within the earth. The Falklands, for example, are now thought to be a tiny segment of the African plate that separated from the east coast of southern Africa millions of years ago. New Zealand once adjoined eastern Australia; the island continent of Australia was once part of a massive supercontinent, Gondwana, that broke up in the Mesozoic period, over a hundred million years ago.

Oceanic islands are those that have never been a part of, or connected to, a continental land mass: they have literally risen out of the sea. Some are volcanic. Where, as along the mid-Atlantic rift system, the crustal plates are gradually pulling apart, liquid magma spills out onto the ocean floor, eventually reaching the surface. St Helena and Ascension Island provide examples. In tropical regions coral organisms may establish themselves on such volcanic islands, forming a coral skirt around the island; sometimes where the volcanic core sinks oc^fae-.^ea level rises the growing coral overtops the

17

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

original volcanic island, and no volcanic rock is visible at the surface. Tahiti and Mauritius are islands with a fringing skirt of coral reef; the Cocos Islands - now known by the clumsy name of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands -show no volcanic material at the surface. The origin and nature of coral islands were of great interest to Charles Darwin, and will be discussed in much greater detail later.

Just as continental and oceanic islands differ from each other in their geology, so too they differ biologically. Usually continental islands support biotas (assemblages of plants and animals) from the continents of which they formed parts. Chiloe and Tierra del Fuego share many organisms with the nearby South American mainland. Tasmania has many plants and animals in common with Australia. New Zealand's biota differs from that of Australia to a much greater degree because it has been separated longer. Australia, because of the ancient Gondwanan connection, has a few groups in common with South America.

Oceanic islands have a depauperate biota in comparison with continental islands. When they formed as the result of volcanic activity or coral growth (or very often a combination of the two) they will have been devoid of terrestrial life-forms. All plants and animals (or their ancestors), be they flowering plants, ferns, mosses, fungi, birds, insects or reptiles, must at some time have made the journey from some other landmass. Seeds and fruits (such as coconuts) floated. Birds and insects may have been blown by the wind. Some seeds, and perhaps tiny insects and other invertebrates (or their eggs) might have adhered to the feathers or other parts of birds. Other seeds could well have travelled in the guts of birds. Very occasionally a reptile, or even a small mammal, may have been transported to an island by rafting, aboard a floating tree-trunk or a mass of vegetation debris. Conditions may have been difficult on a small remote island; for sexually reproducing organisms it might have been a long time before the arrival of a mate of the same species; there is the risk of being blown into the sea. Extinction rates may therefore be high. There is thus a 'chanciness' or serendipity about the assemblage of plants and animals on an island: what is found there depends on what has been carried thither and has survived. However, some types of creature, for example freshwater fish and amphibians that cannot survive salt water, are rare, while plants with tiny spores that can be blown by the wind (ferns, mosses) are often quite well represented.

Darwin, on his travels, as we shall see, noticed the differences in richness between island and continental environments: these have important evolutionary significance. If all life is derived from a very limited number of original forms, the life-forms found on remote islands must have made the journey thither, and will be distinctive in the manner described. In the

18

[page]

Darwin's Islands in Context

theory of independent creation there is no reason why there should be significant differences in the forms the Creator placed on islands and those on continents.

Finally it may be noted that there is a high degree of endemism or uniqueness on islands: there are often organisms that are unique to a single island or archipelago, the result of periods of isolation. This too makes for the distinctiveness of island biotas, and this fact too was occasionally noted by Darwin.

Notes

1. N. Barlow (ed.), Charles Darwin's Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. 'Beagle' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1934) (referred to subsequently as Diary), p. 430; written late September 1836.

2. Darwin's 'Ornithological Notes' (DAR 29.3) have been dated to about June 1836, towards the end of the voyage. They are transcribed in: N. Barlow (ed.), Darwin's Ornithological Notes, Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Series 2.7 (1963); see p. 134.

3. A list of the books known to be aboard the Beagle is given in Appendix 4 of Correspondence, Vol. 1.

4. J. F. W. Herschel, Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, 1830). Darwin's edition was rebound as part of the 'Cabinet Cyclopaedia', 1831. The quotation is from Part 3, Chapter 6, p. 167. John Frederick William Herschel (1792-1871) was the son of William Herschel (1738-1822) and nephew of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), both of whom were also astronomers. John was something of a polymath: classical scholar, pioneer photographer, instrument-maker and philosopher of science, as well as astronomer. Darwin met him in Cape Town in May 1835, while he was living in South Africa, mapping the southern stars. It may be that the two had important discussions on scientific matters at this meeting.

5. Geological Diary, DAR 38.2/957-60.

6. Diary, probably September 1836, p. 429.

7. Zoological Diary, DAR 31.2/354-5.

8. Physa is the scientific name for a type of gastropod (snail). Perhaps the young naturalist meant Physalia, the Portuguese man-of-war, a stinging jellyfish.

9. Zoological Diary, DAR 31.2/359-60.

10. Diary, 4 June 1836, p. 407.

11. Ibid., 30 April 1836, p. 402.

12. Ibid., 20 September 1836, p. 421.

13. Voyage, p. 483.

14. Zoological Diary,DAK 31.2.

19

[page]

3. The Mystique and Myth of the Galapagos - and the Reality

All remote islands possess a certain romantic mystique. But Charles Darwin has raised the mystique of the Galapagos Islands to a level that finds virtually no rivals in the history of scientific thought. Both for the biology textbooks and for the history of science, these 'enchanted islands' have become the highly acclaimed symbol of one of the greatest revolutions in Western intellectual thought. Indeed, that this momentous scientific revolution sprang from insights that Charles Darwin garnered during a brief five-week visit to the Galapagos in 1835 has made them into the symbolic equivalent of Newton's famous apple among the great stories of scientific discovery. But unlike Newton's apple, with its fleeting but historic fall, the Galapagos Islands have remained a permanent showcase of the fundamental insights that Charles Darwin first divined. For those who have visited the Galapagos in Darwin's historic wake, there is inevitably a feeling of being on hallowed ground and standing intellectually in Darwin's awesome and ever-present shadow.1

So wrote Frank Sulloway, a distinguished Darwin scholar.2 Darwin himself, in his Autobiography, recalled:

During the voyage of the Beagle I had been deeply impressed ... by the South American character of most of the productions of the Galapagos archipelago, and more especially by the manner in which they differ slightly on each island of the group; none of these islands appearing very old in a geological sense.3

[page]

The Mystique and Myth of the Galapagos - and the Reality

David Lack, later Director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology, in Oxford, who undertook fieldwork on the Galapagos in the 1930s, asserted: 'Darwin first questioned the [im]mutability of species when actually in the Galapagos, through finding different forms of mockingbird and tortoise on different islands.'4 However, a careful scrutiny of the archives reveals there was no Eureka-like experience in the Galapagos. Although Darwin was deeply impressed by the archipelago, and made many extremely important observations there, it was only some years later, and indeed many months after his return to England, that he was 'converted' to an evolutionary position. Nevertheless, the idea of the mutability of species seems to have passed fleetingly through his mind earlier. While actually on the islands he was uncertain about which region it was to which they had closest biological affinities. He was puzzled on seeing seals, penguins, palms and tropical birds. His recollection in the Autobiography, written late in his life, well over 40 years after the event, seems to be either mistaken or gives an incorrect impression.

In fact Darwin spent only nineteen days, in some cases only in part (and in a few instances only for a period of an hour or two), on land in the Galapagos archipelago. The remainder of the 40 or so days he was aboard the Beagle, as she made her way from island to island engaged in hydro-graphic survey work. It seems that he landed on only four islands, although he had quite good shipboard views of a further eight. Let us examine the details of this sojourn, remembering that by the time he went ashore on the Galapagos he had been voyaging for four years and eight months, and explorations of dozens of islands and many parts of the continent of South America lay behind him.

HMS Beagle left the mainland of South America on 7 September 1835, and by the 15th was surveying the eastern coasts of Chatham (San Cristobal) Island; the following day the ship came close to Hood (Espanola) Island, but Darwin did not disembark. He noted, however, the presence of a couple of American whaling-ships. The Beagle then swept away northwards to Chatham once more, where Darwin spent an hour at Wreck Point, on the western side of the island. He wrote in his diary:

These islands at a distance have a sloping uniform outline, excepting where broken by sundry paps & hillocks; the whole black Lava, completely covered by small leafless brushwood & low trees. The fragments of Lava where most porous are reddish like cinders; the stunted trees show little signs of life. The black rocks heated by the rays of the Vertical sun, like a stove, give to the air a close & sultry feeling. The

21

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

plants also smell unpleasantly. The country was compared to what we might imagine the cultivated parts of the Infernal regions to be.5

Certainly Darwin's initial impression of the Galapagos was not very favourable. On 17 September the ship moved to Stephen's Bay (Darwin refers to 'St Stephen's harbor [sic]') and the day started more propitiously:

The Bay swarmed with animals; Fish, Shark & Turtles were popping their heads up in all parts. Fishing lines were soon put overboard & great numbers of fine fish 2 &c even 3 feet long were caught. This sport makes all hands very merry; loud laughter & the heavy flapping of fish are heard on every side.6

But in his account of the latter part of the day, negative images appear once more:

After dinner a party went on shore to try to catch Tortoises, but were unsuccessful. The islands appear paradises for the whole family of Reptiles. Besides three kinds of Turtles, the Tortoise is so abundant that [a] single ship's company here caught 500-800 in a short time. The black Lava rocks on the beach are frequented by large (2-3 ft) most disgusting, clumsy Lizards. They are as black as the porous rocks over which they crawl & seek their prey from the Sea. Somebody calls them 'imps of darkness'. They assuredly well become the land they inhabit. When on shore I proceeded to botanize &c obtained 10 different flowers; but such insignificant, ugly little flowers, as would better become an Arctic than a Tropical country.7

The tortoise hunt was 'unsuccessful'; the number of negative adjectives is high: disgusting, clumsy, insignificant, ugly. The image of the 'imps of darkness' fits well with that of the 'Infernal regions' mentioned in the account of the previous day, along with the heat and the dark, black rock. Perhaps one of his shipmates suggested the comparison (he seldom adopted religious imagery), but for a while at least Darwin seems to have caught the notion of the Galapagos Islands as some sort of Hell on Earth. Nevertheless, there was much of interest: the tortoises and birds were extremely tame. Little birds, probably some of them the finches that now bear Darwin's name, hopped in the bushes within three or four feet. 'Mr King killed one with his hat', he noted; and Darwin himself pushed a large hawk from a branch with his gun.

On 18 September the ship moved again, to Terrapin Road, close to the northernmost tip of Chatham Island, and Darwin went ashore and made careful observations of the rocks and volcanic land-forms. The 19th and 20th were spent almost entirely at sea on hydrographic survey on the

22

[page]

The Mystique and Myth of the Galapagos - and the Reality

eastern side of the island, which he noted seemed to have more surface streams than other parts, and indeed he described a 'small cascade'; the valleys were a brighter shade of green. On 21 September the Beagle returned to Stephen's Bay. Darwin and his servant, Syms Covington, were again landed for studies of the small volcanic cones that dot the area, and that day and the next they 'collected many new plants, birds & shells & insects'. Darwin was also pleased to see the volcanic forms: 'long familiar, but only by description'. Despite the interest, however, he seems to have had no great affection for the place: the negative and 'infernal' images recur. The day was 'glowing hot', and the chimney-like volcanic features reminded him of 'the iron furnaces near Wolverhampton'. The bare volcanic rock, devoid of vegetation, was 'rough and horrid'. Darwin came up close to some of the giant tortoises, one of which hissed at him! He thought they 'appeared most old-fashioned antediluvian animals or rather inhabitants of some other planet'. He and his servant slept on the beach, and continued collecting on the 22nd, returning to the ship in the evening.

On 23 September the ship followed a somewhat irregular course to Charles (Santa Maria) Island, passing quite close to Barrington (Santa Fe), small and low but steeply cliffed. The next few days were spent exploring various parts of Charles Island, a ship's boat sometimes delivering Darwin to a place that he wanted to explore. On one occasion he met a Mr Lawson, an Englishman, currently acting as governor, who took him and one or two companions about four and a half miles (7 km) inland to view the settlement, just six years established. The volcanic soil here was more fertile than elsewhere and there were freshwater springs. Sweet potatoes and plantains were grown; and the population of 200-300 (mainly persons convicted of political crimes in Ecuador) lived in houses 'built of poles & thatched with grass' scattered over the cultivated area. The people existed by hunting goats, wild pigs and tortoises. The depredations of residents and visiting ships on the tortoises were already serious: they had 'formerly swarmed' close to the pools, but were now much scarcer. 'The ship's company of a Frigate brought down to the beach in one day more than 200.' Mr Lawson thought that there would be few left in another 20 years, and already he was seeking supplies from James Island (San Salvador).

Some of the animals there are so very large that upwards of 200 lbs of meat have been procured from one. Mr Lawson recollects having seen a Terrapin, which 6 men could scarcely lift & two could not turn over on its back. These immense creatures must be very old; in the year 1830 one was caught (which required 6 men to lift it. . .) which had various dates carved on its shell: one was 1786.8

23

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands

Collecting continued on 26 and 27 September. Darwin wrote in his diary: 'I industriously collected all the animals, plants, insects & reptiles from this Island.' This implies that he felt that he had made a nearly complete collection: certainly he seems to have collected more insect specimens on Charles Island than on the others, although occasionally it seems he may have intermingled specimens from different islands.9 His notes show that many dozens of Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), Hemiptera (bugs), Hymenoptera (ants, bees, wasps) and Orthoptera (grasshoppers) were collected, probably many of them by using a sweep-net in the vegetation high on the island. He wondered 'from what district or "centre of creation" future comparison might show that the organized beings of this archipelago must be attached.'10 He ascended to the summit of Saddle Mountain, the highest hill on the island. He estimated it at 2,000 feet (610 m) (modern maps show it at 2,700 feet [825 m]), finding there 'the remains of an old crater' covered with 'coarse grass & Shrubs'. Darwin was extremely interested in the volcanic land-forms, counting 39 conical hills on the comparatively small island, in the summit of each of which 'there was a more or less circular depression'. From the thickness and fertility of the soil, the relatively smooth outline, and from the covering of vegetation, he deduced that it had been 'long' since the lava streams that covered the lower part of the island had flowed from these craters.

On the morning of the 28 September HMS Beagle sailed from Charles Island to the southern tip of Albemarle (Isabela) Island, Captain FitzRoy surveying its southern approaches. As the ship came to anchor in Iguana Cove, Darwin recorded that this island was 'the highest & boldest' they had seen. The volcanic landscape continued to fascinate him; he noticed onshore a landscape 'studded with little truncated cones'; the craters were 'very perfect' and generally had reddish interiors. 'The whole had even a more workshop appearance than that described at Chatham Island', he noted. Darwin did not land here; instead the ship sailed northwards between the upright of the reversed 'L' of Albemarle Island, and Narborough (Fernandina). His generally unfavourable reactions continued: Narborough had 'a more rough & horrid' aspect than any other; the shortage of water (each man was reduced to half a gallon for all purposes) was a 'sad drawback' in the 'overpowering' heat; when they found some water in small depressions on northern Albemarle it was 'not good'; the country was 'arid &C sterile'; lizards he found were 'clumsy' and 'hideous'. A day or two later he wrote of the same island that he thought it would be difficult to find 'in the intertropical latitudes a piece of land 75 miles long, so entirely useless to man or the larger animals'. Nevertheless, he continued to make thoughtful observations, although he did not see any tortoises.

24

[page]

The Mystique and Myth of the Galapagos - and the Reality

He describes the suite of volcanic forms and his exploration of them very lucidly:

To the South of the Cove [Targus Cove] I found a most beautiful Crater, elliptic in form, less than a mile in its longer axis & about 500 feet deep. Its bottom was occupied by a lake, out of which a tiny Crater formed an Island ... The ... lake looked blue & clear. I hurried down the cindery side, choked with dust, to my disgust on tasting the water found it Salt as brine. This crater & some other neighbouring ones have only poured mud or Sandstone containing fragments of Volcanic rocks; but from the mountain behind, great bare streams have flowed, sometimes from the summit, or from small Craters on the side, expanding in their descent, have at base formed plains of Lava.11

Despite the heat, thirst and dust his observation of animals remained astute. He carefully compared the terrestrial lizards he found in the mountains with the marine forms he had encountered by the shore; he thought from their structure that they were 'closely allied' to the 'imps of darkness'; he noted that this species lived in burrows, into which it hurried when frightened; the creatures had a ridge and spines along the back and were orange-yellow with the hinder part of the back brick-red in colour; they weighed 10-15 lb (4.5-6.8 kg) and were 2-4 ft (0.6-1.2 m) in length. They were considered good eating. Darwin commented, 'this day forty were collected'.

On 2 October the Beagle sailed from what Darwin called 'Crater Harbor, [sic]' but the ship was becalmed between Narborough and Albemarle Islands, and made her way slowly round the north of the latter. Darwin continued to study the coastline, noting that it remained 'studded with small craters', although there were some 'great Volcanic mounds' from which streams of black lava had flowed. The ship, having rounded the north point of Albemarle, seems to have been swept over 100 nautical miles back to the east, and the next week was spent 'most unpleasantly . . . struggling to get about 50 miles to Windward against a strong current'. Darwin was pleased when they eventually reached James Island (San Salvador), on 8 October. He was landed, along with Mr Bynoe,12 some provisions and three seamen, while the Beagle returned to Chatham Island to take on water, supplies of which were now depleted. The group set up camp in a small valley a little inland from the beach at Buccaneer Cove, somewhat to the north of James Bay. Initially at least Darwin was little more impressed with James Island than the others he had visited or seen from shipboard: 'there was a miserable little Spring of Water', and the seamen had to work hard to keep the group supplied. One day the group found a human skull in the bushes at the point where a few years previously the crew of a sealing vessel had murdered

25

[page]

Darwin's Other Islands