[front cover]

CHARLES DARWIN

JUSTICE OF THE PEACE

THE COMPLETE RECORDS (1857-1882)

John van Wyhe & Christine Chua

[inside front cover]

[page 1]

© John van Wyhe and Christine Chua 2021. RN1

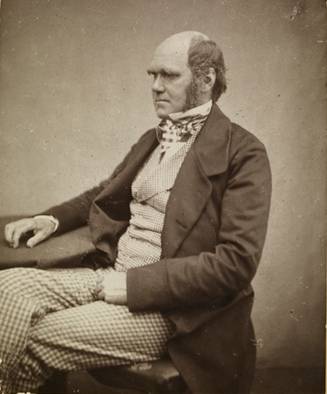

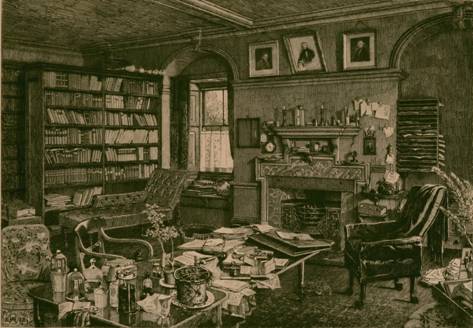

Front cover illustration: Charles Darwin in 1857, the year he became a justice of the peace. Photograph by Maull & Polyblank. This photograph is always attributed to "Maull & Fox" (after the name of the firm on later prints) but their partnership was 1879-1885. Back cover illustration: Copper engraving of Darwin's new study at Down House in 1882, after Darwin's death, by Axel H. Haig.

[page ii]

[page 1]

CHARLES DARWIN

JUSTICE OF THE PEACE

THE COMPLETE RECORDS (1857-1882)

John van Wyhe & Christine Chua

[page 2]

[page] 3

CONTENTS

Introduction 4

Justices of the peace 21

Darwin at the bench 31

The petty sessions reports 37

Magistrate Darwin in the news 48

Afterword 95

Acknowledgements 96

References 97

[page break]

[page] 4

"Perhaps no student since man first began to speculate on the world which surrounds him ever attained ideas so far in advance of what had been deemed true, and saw these ideas find acceptance with his contemporaries." Daily News, 21 Apr. 1882.

INTRODUCTION

The epigraph above from the London Daily News aptly encapsulates the way Charles Darwin was seen by the public, at home, abroad and by posterity, as the man of science who revolutionized our understanding of life on Earth. This makes it all the more surprising for many readers to learn about the more mundane, familial and social activities he engaged in during his life apart from his science and sometimes together with his science.

Darwin has long been one of the most intensively studied men of science in history. One might easily assume that there were no significant aspects of his life that had not already been revealed. And yet there is a fascinating side to Darwin's public life that is still almost completely unknown. From July 1857 until he died in April 1882, Darwin was a justice of the peace (JP). Although the bare fact that he was a JP has been known and mentioned in the literature on Darwin from the very beginning, so far only brief mentions or summaries have ever appeared.[1] The reason for this brevity and vagueness is that the official case records are lost.

But press reports in provincial newspapers have been found that enable us to reconstruct the full story of Darwin as a justice of the peace. This lost record contains many surprises and not a few amusing episodes with which the great naturalist was involved in his local community. For example, the very day that his revolutionary Origin of species was published on 24 November 1859, a crime and "riot" occurred in his own sleepy village of Down that he would later pass judgement on from the bench. It will come as a surprise to any reader interested in Darwin to discover just how much his life was taken up with acting as a justice of the peace at one of the most important and analysed parts of his life, the years bracketing the publication of Origin of species. Rediscovering Darwin's activities as a justice of the peace helps bring to life a more vivid and nuanced picture of his real original historical and social contexts. He was not an isolated thinker concerned only with evolution or corresponding with the great scientific minds of the day. His complete life included also more parochial concerns. And his local context included not just other wealthy landowners and their many dependent staff but shopkeepers, publicans, police constables, labourers, coachmen, poachers, brawlers and petty thieves. Who would ever think that Charles Darwin, while writing the most influential book of science in history was at the same time fining petty thieves for stealing plums?

A more careful study of the rules, roles and duties of JPs in the mid-nineteenth century also reveals that the few mentions we do have of his activities in this role in the existing literature are very often mistaken and misinformed. For example, Darwin was not, as sometimes described, a "judge" and he did not preside at a "police court".

After returning home from the voyage of the Beagle in October 1836, Darwin stayed briefly in Cambridge and then took a house in London to be close to the scientific experts and societies that were describing and discussing his many specimens from the voyage. It was during this fruitful time that his theory of evolution began to develop and he "thought much upon religion."[2] He soon began "giving up revelation" and gradually concluded that Christianity was not supported by evidence.[3] And, of course, he concluded that species must change over time— they evolve.

The other major change in his life was that he sought the hand of his cousin Emma Wedgwood (1808-1896). They were married on 29 January 1839. The young couple settled in a rented house in London where their first two children were born. Growing weary of busy, noisy, smoky and filthy London, in September 1842 the Darwins purchased Down House just outside the tiny village of Down (later spelled Downe) with eighteen acres of land in rural Kent for £2,020. It was only about two hours by carriage and train to central London yet quiet and quintessentially rural. Here Darwin would live and work for the rest of his life.

In later years, a friend and neighbour would recall the look and feel of Down in those days.

The neat little houses, no two or three alike, stood near together, but with trim gardens fronting the clean street, each with picket fence and wicket gate, and gay with old-fashioned flowers all the summer time. Some of these cottages were old-time houses, built of unbaked clay bricks, set in transverse frames of timber, which had held up the old thatched roofs for hundreds of years. …

But these old whitewashed houses had mostly given place to the warm red brick, with slate roofs that brighten and silver in the sunshine. Three little stores had been made, by the enterprising tradesman building out over his front garden to the village street. At the head of the village it branched out into two more roads, widening at the branching point into an open space. On one side of this stood the old parish church, and had stood for eight hundred years,—restored, as the parson called it, spoiled as some of the rest of us thought, at a recent date. Still the solitary yew tree stood its sentinel at the churchyard gate, and had stood for the same eight hundred years[4]

Not quite the recluse as he is often depicted, as one of the wealthiest gentlemen in the neighbourhood, Darwin soon became a respected and integral part of the community.[5] His patronage provided jobs, stimulated the village economy and the family's charitable gifts and donations to the poor soon earned them great admiration and respect from the villagers and those living in the neighbourhood. At this stage of his life Darwin was forty-eight years old and head of a large family, the owner of a large house and modest estate, a landlord, a prodigious portfolio of stocks and investments and employer of numerous domestic servants including a butler, footmen, coachmen, cooks, gardeners, a governess, a housekeeper and various maids. Darwin spent about £120 a year on menservants' wages. Over the years many tradesmen and others would also work in his employ. For example, a boy named William Baxter (1860-1934) used to work for Darwin as an errand boy and delivered chemicals and medicines to Down House.[6] There were very many more.[7]

The Darwins' estate was not just a fine house, but more a farm. Indeed Darwin was listed as "farmer" in Bagshaw's Directory for Kent in 1847.[8] There were cows for milk, a horse to help in the haytime and for pulling the phaeton or tax-cart and a donkey which pulled the lawn mowing machine. These were kept in the stables and grazed in the paddock. There were chickens for eggs which his daughter Henrietta could remember taming until they would eat out of her hand. Sometimes there were also ducks and geese. The family usually had a dog or two and some cats.

For his research on artificial selection as an analogous process to natural selection in nature, Darwin kept every breed of domesticated pigeon he could procure. In 1855 he had an elevated hexagonal wooden pigeon house built near the well and later the "principal wooden pigeon house" was built above the tool house behind the kitchen garden wall. His daughter Henrietta could remember "A cross old fantail who in taking food from my hand liked to give a good peck & hurt me if he could. The pouter pigeon was good natured but not clever, and I remember a hen jacobin which I considered rather feeble minded."[9] Darwin's son George could remember "A good large aviary was erected on a patch of ground near the well, & near where the douche stood. Everyday there used to be an inspection of the pigeons before starting for a walk".[10] By mid-1858 Darwin's researches on pigeons had been completed and the aviary was abandoned. Eventually it became completely smothered in ivy. It finally blew down in heavy winds a few days after Darwin's death in 1882.

Always methodical, Darwin kept very detailed household accounts from the time of his marriage onwards. He had columns for all the staples: meat, fish and game, poultry, bacon, butter, cheese, sugar, bread, butter, tea and coffee.[11] There was a large kitchen garden beyond the ornamental area by the house and an orchard at the north end of the property with several varieties of pears, apples, cherries, apricots and oranges.[12]

Darwin's home and garden were also where he carried out his scientific research into all manner of previously unimagined evolutionary puzzles. As a neighbour recalled: "Home was his experiment station, his laboratory, his workshop."[13] His servants were utterly baffled by Darwin's scientific activities. His neighbour and friend John Lubbock (1834-1913) recollected the words of one of the gardeners.

One of his friends once asked Mr. Darwin's gardener about his master's health, and how he had been lately. "Oh!", he said, "my poor master has been very sadly. I often wish he had something to do. He moons about in the garden, and I have seen him stand doing nothing before a flower for ten minutes at a time. If he only had something to do I really believe he would be better."[14]

Darwin was very methodical and unvarying in his daily routine. He got up early, took a bath, and went for a short walk along the roads before breakfast, sometimes accompanied by one of his children. By 7.30 he would have a light breakfast of an egg and tea. His son George recalled: "He was particularly attached to a very old cup, the last remaining one of an old set which had once been blue & gold. But as I remember it, the blue was partly worn off & blotched to a dirty brown & the gold nearly all gone."[15]

After breakfast he retired to his study to work from 8 to 9.30am. He regarded this as his best working time. At 9.30 he would emerge and walk over to the drawing room to collect his letters from the first post. Looking at the envelopes was often accompanied by muttered expressions such as "'Oh dear, here's this bothering fellow again', or 'there's a letter from old Hooker'". He would then take the letters back to his study. Afterwards he would listen to a novel read aloud until 10.30. George recalled that "He often astonished us what trash he wd tolerate in the way of novels. The chief requisites were a pretty girl & a good ending."[16] Darwin then went back to his study. At 12 or 12.30 he would go for a walk on the sandwalk accompanied by his dog. The sandwalk was a circular path through a small wood at the south side of the property, originally the path was dressed with red sand, hence its name. The little wood through which it wound was planted with a variety of trees including oak, elm, beech, hornbeam, birch, alder, hazel, lime and an old ash tree.

After his midday walk he would find the second post of the day waiting shortly before 1pm. Then it was time for lunch followed by reading the newspaper on the drawing room sofa. With this relaxation concluded, it was time to answer his letters. Many he would dictate to a member of the family. When this was finished he would go upstairs to his bedroom for a rest. Emma would read a novel and he would often fall asleep and miss part of the story. She kept reading to avoid waking him. At 4pm he could be heard coming downstairs to re-enter his study for more work and a cup of coffee. At 5.30 he would return to the drawing room to visit with his family until 6 when he would go upstairs for another rest. Dinner was at 7.30 although he ate little. Afterwards he and Emma would play two games of backgammon and they kept score for many years. After the games he would read a scientific book before going to bed at 10.30. The children could remember that he would always blow his nose loudly as he undressed. Perhaps this had something to do with the snuff he habitually took.

Even before his famous Origin of species, Darwin already had an impeccable reputation in the scientific community from his voyage on the Beagle as naturalist and best-selling book of travels about it, his major geological, paleontological, zoological and botanical discoveries, his revolutionary coral reef theory his ongoing comprehensive taxonomy of barnacles and a large variety of other original work and discoveries.

The very day he packed up the last of his barnacle specimens at the conclusion of his eight-year project, he noted down: "Sept. 9th. [1854] began sorting notes for Species Theory."[17] From that moment on his theory of evolution was his full-time occupation and no longer worked on in the background and inbetween other projects on his list of things to do. For the succeeding years he had worked at research and experimentation with this in view. In May 1856 he began writing up his theory for publication. By mid-July 1857 he had completed seven and a half chapters. He probably had another two to three years ahead of him to complete what he saw as the great work of his life. It was at this stage in his life that, on 3 July 1857, that Darwin was appointed a justice of the peace.

Some modern writers describe Darwin being a justice of the peace as part of an oppressive regime determined to keep down the poor. Although there is more than a grain of truth to such a perspective, nowadays such interpretations are still common if wearing their age and Marxist origins not very loosely. Others think Darwin becoming a justice of the peace was to gain respectability, something such a wealthy, upper-class and well-educated public figure could not possibly worry about or require in his local community or beyond it. This is a notion only late twentieth-century authors have imagined. Equally modern and imaginary are stories that purport that Darwin feared losing his respectability because of his evolution theory. Darwin was so utterly part of wealthy, respectable society that, evolutionary theorizing notwithstanding, this was never an issue for him and never entrered his mind. Even at the height of the controversies over Darwin's theories, his social respectability was never in doubt or at issue in the slightest. After all, the debate over evolution was a debate within the intellectual and scientific elite, not one of the socially respectable vs. a socially insignificant handful of radical ruffians. Historian of science James Secord suggested we see it as more of a palace coup within the scientific elite rather than a popular revolt.[18]

If Darwin took up the office of justice of the peace as respectable camouflage for his evolutionary theorizing, then how shall we explain all the other gentlemen of almost identical background, social class, education and wealth who did so? Were they also seeking respectability cover? And if it was a shield of respectability, what good was that when no one apart from people in Kent knew about it? And after his theory had gone public and his respectability was not attacked, why stick with the considerable trouble of working as a justice of the peace? Writing with a more even hand, Darwin biographer Janet Browne described it as "an occupation at the heart of provincial life in which law-abiding, landowning gentlemen like himself imposed fines on poachers or issued licenses for keeping pigs."[19] Quite so. Yet the need to look more closely at this facet of Darwin's life remains. As it turns out, justices of the peace, including Darwin, did not issue licenses to keep pigs.

Contemporary sources and the recollections of those who knew him described Darwin being a justice of the peace (or magistrate) as civic-minded volunteering. He may have seen it as one of the obligatory responsibilities of a man of his means and social position. And abhorrence of theft, violence and animal cruelty were some of Darwin's most deeply felt passions. As his third son Francis wrote of the latter, "It was indeed one of the strongest feelings in his nature".[20] Darwin's eldest son, William, in a speech given at the Darwin Celebration banquet in Cambridge in 1909, said:

There was living very near us at Down a gentleman farmer...this man had allowed some sheep to die of starvation. My father heard of it and at once took up the matter, and though he was ill and weak and it was most painful to attack a near neighbour, he went round the whole parish, collected all the evidence himself, and had the case brought before the magistrates, and as far as I can recollect he got the man convicted. This, I remember, as a boy impressed me immensely; he took it so seriously and devoted himself to it, though his health was in such a bad state.[21]

The science writer and anthropologist Richard Milner wrote in 2009: "Once [Darwin] witnessed a man cruelly whipping his horse on the road. Pulling to a stop in his own carriage, Darwin angrily told the driver that he was a magistrate in the district and that if he caught the man abusing an animal again, he would personally haul him into court and throw the lawbook at him."[22] As vivid as this account appears, there is no such record of Darwin wielding his title of magistrate like this. Milner's story seems to be based on this passage from Francis Darwin's published recollections:

In smaller matters, where he could interfere, he did so vigorously. He returned one day from his walk pale and faint from having seen a horse ill-used, and from the agitation of violently remonstrating with the man. On another occasion he saw a horse-breaker teaching his son to ride, the little boy was frightened and the man was rough; my father stopped, and jumping out of the carriage reproved the man in no measured terms.

One other little incident may be mentioned, showing that his humanity to animals was well known in his own neighbourhood. A visitor, driving from Orpington to Down, told the cabman to go faster. "Why," said the man, "if I had whipped the horse this much, driving Mr. Darwin, he would have got out of the carriage and abused me well."[23]

Milner quoted another amusing though much later recollection: "I remember how troubled [Darwin] was once when he had to punish some boys who had robbed his orchard. 'I do wish the police hadn't caught them,' he said to me." This is credited to: "George Sales, 1939".[24] There is no reference given and this quotation could not be traced. The name Sales is however that of the family of the long-term grocer and publican of Down, William Sales (1808-1880) and his son Sydney Sales (c.1844-?) who was listed as a retired grocer in the 1881 census. In 1937 a George Edward Sales was living in Myrtle Villa, Downe.[25] However, no record of a theft from Darwin's orchard has been found.

In 1852 Darwin remonstrated in vain by letter with a neighbour, the Rev. Robert Ainslie (1803-1876), a fellow Cambridge graduate, Methodist minister and writer who lived (1845-1858) at the grand Tromer Lodge, along Luxted Road just on the southern edge of the village. Ainslie was even then having a fifty-one-foot tower added to his home.[26] It had been reported that Ainslie was working his horses even though they had sores on their necks (i.e. his farmhands were doing so.) When this letter didn't work, Darwin took matters into his own hands. His wife Emma wrote to their son William: "Papa is in hopes that Mr Ainslie will be punished for working his horses with sore places on their necks. An officer of the Society for preventing cruelty to animals was sent for by your father to see what state his horses were in & he is going to have him up before a magistrate & his ploughman also, but he is afraid that only the man may be punished & not the master."[27] Darwin did report Ainslie to the local magistrates and as Darwin later wrote to another local landowner working injured horses: "Mr Ainslie was fined by the Magistrates at the Bromley Session."[28] Apparently a troublemaker, Ainslie was strongly disliked by the Darwins. As far back as 1845 Darwin had written to his sister Susan complaining about Ainslie altering the road illegally.[29]

In his biography of his father, Francis Darwin recorded Darwin's social mindedness:

He was also treasurer of the [village] Coal Club, which gave him some work, and he acted for some years as a County Magistrate.

With regard to my father's interest in the affairs of the village, Mr. Brodie Innes has been so good as to give me his recollections:—

"On my becoming Vicar of Down in 1846, we became friends, and so continued till his death. …In all parish matters he was an active assistant; in matters connected with the schools, charities, and other business, his liberal contribution was ever ready.[30]

Similarly, another son, Leonard, recalled it was a "civic duty" as seen by Darwin's role in the "Down Coal club…and his having sat for some few years as a magistrate, [which] are worth recording as showing that he certainly would have been active in his civic duties had his health permitted."[31]

The American anarchist and journalist Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915) wrote fourteen books in the series Little journeys to homes of the great. The volume on Darwin has a section on him as a magistrate which has sometimes been quoted as it has details found nowhere else.

For several years Darwin was village [sic] magistrate. Most of the cases brought before him were for poaching or drunkenness. "He always seemed to be trying to find an excuse for the prisoner, and usually succeeded," says his son. Once when a prosecuting attorney [sic] complained because Darwin had discharged a prisoner, the magistrate, who might have fined the impudent attorney for contempt of court [sic], merely said, "Why, he's as good as we are. If tempted in the same way I am sure that I would have done as he has done. We can't blame a man for doing what he has to do!" This was poor reasoning from a legal point of view. Darwin afterward admitted that he didn't hear much of the evidence, as his mind was full of orchids, but the fellow looked sorry and he really couldn't punish anybody who had simply made a mistake. The local legal lights gradually lost faith in Magistrate Darwin's peculiar brand of justice—he hadn't much respect for law, and once when a lawyer [sic] cited him the criminal code, he said, "Tut, tut, that was made a hundred years ago!" Then he fined the man five shillings, and paid the fine himself, when he should have sent him to the workhouse for six months."[32]

These anecdotes are certainly charming but there are serious inaccuracies which cast doubt on the reliability of the rest. Obviously Hubbard used Francis Darwin's Life and letters (1887) as a source, as did all writers on Darwin. Hubbard never travelled to Britain to research this book nor did he interview any of Darwin's sons and no correspondence between them and him is in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University Library.[33] In fact, Hubbard's words "says his son" may not be meant to suggest that he spoke to or corresponded with one of the Darwins because the identical language was used at that time by writers who were merely referring to what Francis Darwin wrote in Life and letters, except in this case Francis did not write any of these things. The cases Hubbard describes are not found in any of the reports of the petty sessions Darwin attended and there were no lawyers and magistrates could not fine anyone for contempt of court. Nevertheless, Life and letters does not mention poaching, which was indeed one of the more frequent crimes as we will see below. Still, Hubbard's account is so unreliable that his stories should be considered at best vague third-hand memories and at worst, apocryphal.

A lenient magistrate Darwin certainly sounds like what we know of his character. But a recollection by his daughter Henrietta shows how mistaken that might be.

For some years he acted as magistrate. He thought when first he went on that no doubt he shd be all for moderating the harsher views of the other magistrates but quite the contrary the very first time he sat on the Bench some sentence was passed which he thought far too lenient. I have the impression that he thought his fellow magistrates were upon the whole inclined to err in that direction, but that they were generally very fair & took a g[rea]t deal of trouble.[34]

We need to understand Darwin serving as a magistrate not in isolation but as one of very many acts he performed in his community as a gentleman of his social station. Serving as a magistrate was not only not unusual for someone of his place in society, but actually rather typical. Several members of Darwin's family also did so. His half uncle Francis Sacheverel Darwin (1786-1859) was JP and deputy lieutenant of Derbyshire from 1837. Darwin's half-cousin Reginald Darwin (1818-1892) was a highly respected magistrate at Buxton in Derbyshire from 1861. His obituary noted that "as a magistrate, his was an example to be followed. Instances have been known of his having paid the fine rather than the convicted should go to the gaol."[35] He was also remembered as "always taking great pain in the discharge of his duty."[36]

Francis Rhodes (1825-1920) married Charlotte Maria Cooper Darwin in 1849 and changed his name to Darwin in 1850 when he inherited Elston Hall under the will of his brother-in-law, Robert Alvey Darwin. Francis was a very active JP for Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire from 1858. In 1882 he attended Darwin's funeral as head of the senior branch of the Darwin family. Robert Gerard Fox (1849-1909), the son of Darwin's second cousin William Darwin Fox, was a JP for Hampshire. His grandfather, Samuel Fox (1765-1851), had been a JP in Derbyshire. Darwin's half-cousin Erasmus Galton (1815-1909) was JP and deputy lieutenant of Somerset. Darwin's half-first cousin, Darwin Galton (1814-1903), the brother of Francis Galton, was JP and deputy lieutenant of Warwickshire as early as 1858. And Darwin's son Horace was a JP for Cambridgeshire from 1906.[37]

In addition to family, many of Darwin's friends and correspondents also served as magistrates. They include C. R. Barton, J. W. Broderip, C. J. F. Bunbury, C. W. Dilke Jr, W. H. Dixon, J. B. Dunbar-Brander, T. C. Eyton, J. G. Fenwick, J. Higgins, J. W. Lubbock, J. Lubbock, W. H. John, M. H. Massy, Cecil Smith, and his old shipmate John Clements Wickham.[38] So there is nothing unusual about Darwin serving as a magistrate too, and we don't need any idiosyncratic theories regarding him being an evolutionist to understand this.

Almost as soon as he moved to Down, Darwin began to take an active role in village affairs. For example, he established the Down Friendly Society (or Friendly Club) in 1850, which provided insurance for the villagers who lost their work, fell ill or needed funeral expenses. He managed the accounts for decades.[39] He did the same for the Coal and Clothing Club which he also established for the villagers. Members contributed a few pennies and the local gentry made "honorary" contributions. Darwin regularly contributed £5. He kept the accounts in a small notebook from 1848-1869. His son Leonard later recalled:

Each Whit Monday a small group of men marched on to the lawn with a banner flying. This was the Down coal and clothing club, which my father, as treasurer, then came out to address. After a little I generally heard a laugh run through the whole gathering, and I have often since wished that I had had courage enough to have gone sufficiently near to have been able to hear and record my father's jokes.[40]

Darwin sat on the Down church Vestry [committee] from 1844-1871; he was appointed, with Sir John William Lubbock (1803-1865), Surveyor of Roads for 1844-1846, pushed for the founding of a parish library and a village reading room and sat on the village School Management Committee until 1874 when he resigned because of poor health.[41] Together with the vicar and his wealthy neighbour, Lubbock of High Elms and others, he set up the "National" non-denominational day school in the centre of the village. He would see to it that the large schoolroom would later be made available as a reading room for working men in the evening. Anything to keep them from staying too much in the pub.

For decades, Darwin signed memorials and wrote letters of recommendation for worthy causes or individuals. In this he was no doubt hardly distinguishable from other wealthy gentlemen of his class. Many of Darwin's donations were not previously known. In 1858, for example, he donated £3 to the Field Lane refuge, a charitable housing and London Christian mission centre for the poor and unemployed. In 1860 he gave £50 for the formation of a Bromley volunteer rifles corps. In 1861 he gave annual subscriptions of £5 to the Coventry Relief Fund and the Indian Famine Relief Fund, in 1862 £10 to the Lancashire and Cheshire Operatives Relief Fund, in 1864 £5 to the Ladies' Polish Relief Fund for sick and wounded Poles, in 1867 £5 to the East-End Central Relief Committee, in 1871 he supported the Voysey Establishment Fund on behalf of liberal theist preacher Charles Voysey and gave £50 to the Cresy Memorial Fund, in 1872 £3 to the Medical Education of Women Fund. Despite expecting to make a loss, in 1871 he purchased ten shares worth or £100 in the Artizans, Labourers, and General Dwellings Company which was dedicated to building affordable housing for the working classes.[42] In 1875 he donated £5 to "the children's meal" soup kitchen in Merthyr, Wales, for relief during a protracted strike. Also in 1875 he gave £100 to the Stazione Zoologica in Naples, in 1876 £15 to Viscountess Strangford's Bulgarian Peasant Relief Fund, in 1877 £10 for the building of a new infant Sunday school in Frankenwell and £2 2s to the secular Sunday Lecture Society. For years he subscribed to the RSPCA (1854-1861, 1863-1864, 1871-1875, 1878 and 1880). And in 1881 he subscribed to the Carlyle Memorial Fund.

For years near the end of his life, Darwin paid an annual subscription to the South American Missionary Society for the orphanage at the Mission Station in Tierra del Fuego where he had travelled during the voyage of the Beagle. In 1881 he gave 5 guineas to the women's Cambridge colleges, Girton and Newnham, for a physical and biological laboratory. Many more donations are recorded under "Gifts and annual subscriptions" in his Classed account books at Down House, now a museum and property maintained by English Heritage.[43]

Darwin also contributed to all manner of other activities in the area. On 21 January 1861 his young neighbour John Lubbock gave a talk on Coral Islands at the Bromley Literary Institute. The local newspaper noted that the "naturalist" Charles Darwin had lent "Several beautiful varieties of coral" to illustrate the talk.[44] Darwin even made a field available for local cricket matches.[45]

In these benevolently paternalist activities promoting self-help and thrift, he was not alone. Emma Darwin was active as well. She paid regular visits to some of the poorer ladies in the village and brought food, old clothes and small cash donations. From home she would give away "penny bread-tickets" which could be redeemed for bread at the village baker.[46] It was reckoned that over the course of fifty years she must have dispensed thousands of tickets.

Together with other ladies of the gentry, Emma Darwin oversaw the village Sunday School and helped children to learn to read and write. To aid this endeavour, she lent books to village children. Her daughter Henrietta recalled:

They were given out in a little dismal room where she used to interview her many clients for help of one sort or another, flannel, money, cough mixture, etc. On Sunday afternoon the children could come to exchange the books & there was sometimes quite a little crowd. The only rule was that no child should have more than one book This they evaded, if they wished, by inventing demands from the elders of the family, or at least so we thought. If a book was much enjoyed the proof was that it was stolen however often it was replaced. This was the fate of my beloved Little Servant Maids, and at last it was not able to be procured & is now no longer existent.[47]

One of the gardeners, Henry Wheeler, later recollected Emma Darwin's activities: "Mrs Darwin frequently paid visits to the village, of which her famous husband was the squire, and she was very kind indeed to some of the more needy villagers. She was a very sweet woman, and always had a smile and a joke for everyone."[48]

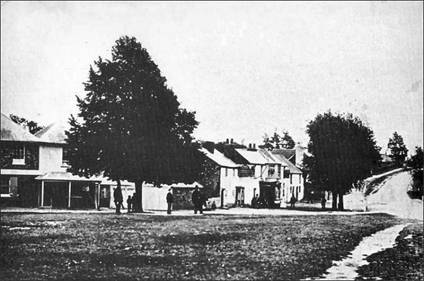

Photographic postcard of Down by G. W. Smith, c.1900.

Darwin seems also to have been on good terms with the village constables. In his book Annie's Box (2001), Darwin descendant Randal Keynes claimed that because of the tragic early death of his daughter Annie in 1851, Darwin "set the Christian faith firmly behind him. He did not attend church services with the family; he walked with them to the church door, but left them to enter on their own and stood talking with the village constable or walked along the lanes around the parish." Keynes cited a 1889 interview by the leading secularist and publisher George William Foote (1850-1915) with "the late head constable of Devonport". Foote said that the unnamed constable "was himself an open Atheist, [and] that he had once been on duty for a considerable time at Down. He had often seen Darwin escort his family to church, and enjoyed many a conversation with the great man, who used to enjoy a walk through the country lanes while the devotions were in progress".[49]

Keynes suggested that perhaps "The constable who told Foote about his conversations with Mr Darwin may have been William Soper, who served at Downe between 1858 and the mid-1860s. He did, though, still firmly believe".[50] But how could the recollection of someone who came to Down seven years after Annie's death suggest that Darwin's church attendance ceased because of her death in 1851?[51] At any rate, the constable was not Soper, but a man named John Lynn (1822-1889) from Stirling in Scotland and the head constable of Devonport. He joined the new London metropolitan police force as a young man when the police were still called "Metropolitan". He left that position after fifteen years. He was then stationed at Chatham and Woolwich and somewhere about this time at Down. But we don't know when. He is not in the 1851 census. After Down he became the Superintendant at Neath and from that position he retired (after an unknown duration) in June 1860. So the date he was at Down could presumably have been around 1855. His obituary also describes: "While stationed in Down, Kent, he made the acquaintance of Charles Darwin, the eminent naturalist. The acquaintance ripened into a warm friendship, and Darwin presented him with several of his works, on which Mr. Lynn set great value."[52] It's difficult to know how much this second-hand and far-removed account can be trusted, but at the very least constable Lynn did chat with Darwin from time to time on friendly terms. But this was likely before Darwin became a magistrate and long after Annie's death.

After Brodie Innes left Down, he and Darwin kept in touch about parish affairs by letter. Darwin continued an active and important patron in church affairs, even though he did not himself attend religious services. Just when he stopped going we don't know.

There is one possible though not very conclusive clue. In 1881 the Darwins were visited for lunch by the radical atheist agitator Edward B. Aveling and the German philosopher and freethinker Ludwig Büchner. After lunch the gentlemen retired to another room to talk about religion. In that conversation, Aveling asked Darwin why he had abandoned Christianity: "the reply, simple and all-sufficient, was: 'It is not supported by evidence.'"[53] This was music to Aveling's ears. Darwin went on to say "I never gave up Christianity until I was forty years of age." That would put it at about 1849.

Despite the fact that such a round number may not have been meant to have absolutely precise, this still does not seem to square with what Darwin recorded in late 1838 that he "thought much upon religion". Before getting engaged in 1839, his father urged him to "conceal carefully my doubts" from a future bride. We know he didn't and Emma's letters to him show that he told her that he was giving up on belief in revelation, which caused her considerable distress.[54] And many years later, in his autobiography, he wrote that in "October 1836 to January 1839…I was led to think much about religion". He gave a list of reasons that led him to doubt and abandon Christianity. And they are indeed about evidence as he had said to Emma.

But I had gradually come, by this time, to see that the Old Testament from its manifestly false history of the world, with the Tower of Babel, the rainbow as a sign, etc., etc., and from its attributing to God the feelings of a revengeful tyrant, was no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindoos, or the beliefs of any barbarian. The question then continually rose before my mind and would not be banished,—is it credible that if God were now to make a revelation to the Hindoos, would he permit it to be connected with the belief in Vishnu, Siva, &c., as Christianity is connected with the Old Testament. This appeared to me utterly incredible.

By further reflecting that the clearest evidence would be requisite to make any sane man believe in the miracles by which Christianity is supported,—that the more we know of the fixed laws of nature the more incredible do miracles become,—that the men at that time were ignorant and credulous to a degree almost incomprehensible by us,—that the Gospels cannot be proved to have been written simultaneously with the events,—that they differ in many important details, far too important as it seemed to me to be admitted as the usual inaccuracies of eye-witnesses;—by such reflections as these, which I give not as having the least novelty or value, but as they influenced me, I gradually came to disbelieve in Christianity as a divine revelation. The fact that many false religions have spread over large portions of the earth like wild-fire had some weight with me. Beautiful as is the morality of the New Testament, it can hardly be denied that its perfection depends in part on the interpretation which we now put on metaphors and allegories.

But I was very unwilling to give up my belief;—I feel sure of this for I can well remember often and often inventing day-dreams of old letters between distinguished Romans and manuscripts being discovered at Pompeii or elsewhere which confirmed in the most striking manner all that was written in the Gospels. But I found it more and more difficult, with free scope given to my imagination, to invent evidence which would suffice to convince me. Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete. The rate was so slow that I felt no distress, and have never since doubted even for a single second that my conclusion was correct.[55]

Losing his faith was slow, gradual and without distress. The death of Annie was the most distressing event in his life.

In 1873 when answering his half-cousin Francis Galton's questionnaire for a study "on the dispositions of original workers in science", Darwin answered as evidence that he had "Independence of Judgment" by writing: "I think fairly independent; but I can give no instances. I gave up common religious belief almost independently from my own reflections." This is a curious remark and hard to interpret. It seems to suggest that his apostasy was not intentional.

At any rate, all of the evidence from Darwin himself points to giving up on Christianity around 1839. So what could he have meant by telling Aveling that he was 40 rather than 30 when he gave up Christianity? It could have been a lapse of memory (which would not be surprising) or a detail just not very important to Darwin. Or could he have meant, speaking to a total stranger, rather than his internal private beliefs, his outward and public observance? That would mean attending church services.

Two decades later the relationship with the village church soured with the appointment of a new vicar, George Ffinden, in 1871. Ffinden was less easy-going than Brodie Innes and tried to foist his sanctimonious take on the Anglican faith onto the parish. Not surprisingly, he and Darwin did not get along. At all. In 1909, the centenary of Darwin's birth, a journalist visited Down to interview those who had known him. Ffinden was still there and said: "I confess that, perhaps, I am a bit sour over Darwin and his works. You see, I'm a Churchman first and foremost. He never came to church, and it was such a bad business for the parish, a bad example."[56] That was the point. A man of Darwin's social position was expected to set an example by outwardly conforming, as well as contributing to a fund for repairing the roof of the church.

In the literature on Darwin, virtually nothing has been written about what a justice of the peace actually was and what it meant in Victorian Britain. Indeed much of what has been written about the subject turns out to be inaccurate. A justice of the peace was defined in the Rural Cyclopedia in 1857 as:

a judicial magistrate.…The justice of the peace, though not high in rank, is an officer of great importance, as the first judicial proceedings are had before him in regard to arresting persons accused of grave offences; and his jurisdiction extends to trial and adjudication for small offences. In case of the commission of a crime or a breach of the peace, a complaint is made to one of these magistrates. If he is satisfied with the evidence…he issues a warrant directed to a constable…ordering the person complained of to be brought before him, and he thereupon tries the party, if the offence be within his jurisdiction, and acquits him or awards punishment.…in general, the appointment is by commission…It is evidently of the greatest importance to the peace and good order of a community, that the justices should be discreet, honest and intelligent.[57]

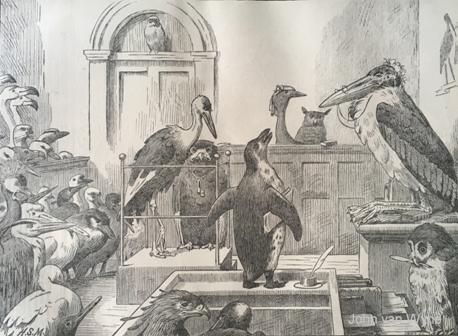

Hence justice of the peace and magistrate are synonymous for Darwin's office. Some earlier writers on Darwin have referred to him and fellow magistrates as "judges". But justices of the peace were not judges. A magistracy was an unpaid public office active in the lowest level of the judiciary from which attorneys were excluded. Judges presided over higher courts with juries and so forth and were able to interpret statutes and the common law. Similarly, some writers have referred to Darwin sitting on "the police court".[58] But police courts were something completely different. Darwin sat on a court of summary jurisdiction, a distinction that is part of the arcane and vast world of the English legal system that modern readers naturally know little about. One should not, for example, imagine Darwin wearing a wig or robes. He didn't. Four nineteenth-century caricatures of magistrates are given below from Punch which, among other things, show that they simply wore their normal clothing.

Formally speaking, justices of the peace were assigned a branch of summary process. One authority at the time described it as follows.

The process is extremely brief: after summoning the offender, the magistrate proceeds to examine one or more witnesses, as the statute may require, upon oath: he then makes his conviction in writing, upon which he usually issues his warrant, either to apprehend the party, in case corporal punishment is to be inflicted on him, or else to levy the penalty incurred, by distress and sale of goods.[59]

Magistrates had the power to impose a fine up to £20, enforce the payment of adequate compensation, remit fees and to commit to periods of imprisonment with or without hard labour.[60] There was no right of appeal to these decisions (with a few exceptions). Magistrates could not convict for felonies, blasphemy, unlawful oaths, abduction and so on, or sentence to transportation for life.[61] The next higher level courts were the quarter sessions, held at least quarterly by at least two justices of the peace "for the trial of misdemeanors and other matters touching the breach of the peace."[62]

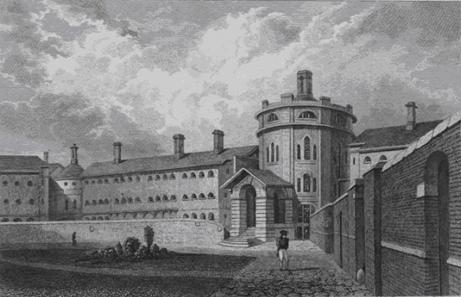

Convicted criminals from the West of Kent were sent to Maidstone County Prison (usually called Maidstone gaol/jail) which had space for 541 prisoners (424 male, 117 female). The majority of the prisoners held there were in for less than two months, and often for only a week or two, no doubt sent there for minor offences by zealous magistrates. It cost the prison 1s 11d to feed a prisoner for a week and the food was usually a very unappetizing gruel or mash. Hard labour consisted of four hours a day on either "the tread-wheel, loom weaving, making mats on a frame with a beater of 5 lbs. weight, work at shearing machines, beating oakum and rope, stone-breaking, and [rotating a] capstan". Four hours on the treadmill was the equivalent of climbing 7,680 feet.[63]

The magistrates of this period were usually, and intentionally, gentry. About one eighth were clergymen in 1842.[64] The gentry were a small minority of landed people of "good breeding", socially below the nobility, but above tradesmen and the common people. The gentry were gradually coming to call themselves middle class in this period.[65] But rural Kent was rather old-fashioned and the traditional notion of gentry continued. In a village such as Orpington (population 1,203 in 1851), there were ten people listed in the local directory as gentry and about forty traders (tradesmen) in 1858. These lists only named the head of the household and not his entire family. In Darwin's village of Down (population 437 in 1851), five gentry were listed and twenty-three traders in the same year. Thus these two villages had the same ratio of gentry to traders listed.[66]

Although unquestionably gentry, the Darwins did not derive the majority of their income from land and rents but investments, particularly in the new industrial technology of the railways as well as government bonds. After 1859, Darwin also made about £500 a year from his books.

As suggested by the Rural Cyclopedia, above, it was believed that in order to ensure respectability, competence and unassailable independence of judgment, a justice of the peace had to be a landholder earning at least £100 a year and one had to swear the oath of qualification to that effect. One also had to take the oath of office, the oath of allegiance and the oath of supremacy. The former was a denunciation of the notion that an excommunicated English sovereign might be deposed or murdered and that no foreign power had any jurisdiction or authority in the kingdom. The oath of supremacy ensured the supremacy of the English crown in ecclesiastical, spiritual and temporal affairs. Both are obviously Elizabethan in origin as was much of the legal system. The oath of office is rather lengthy but boils down to "do equal right to the poor and to the rich"; do not be an interested party in any decision, follow the law and do not take bribes.[67]

Historians of science Adrian Desmond and James Moore cited a different oath: "Keep the Peace of one said Lady Queen in the said County, and to hear and determine divers felonies and also trespasses and other misdemeanours in the same County perpetrated."[68] This dramatic wording seemed to suit their assertion that, because Darwin was working on unorthodox evolutionary views, he was somehow betraying this oath, society or at least living a double life, something they frequently claimed. "He was living a double life with double standards, unable to broach his species work with anyone except [his brother] Eras, for fear he be branded irresponsible, irreligious, or worse."[69]

It is difficult to understand how any writer familiar with the original sources could say this. Contemporary evidence demonstrates unequivocally that Darwin spoke to, as he wrote, "very many" people about evolution. In one of his so-called transmutation notebooks he wrote in 1838 "State broadly scarcely any novelty in my theory, only slight differences" he inserted above this line as evidence for this view: "the opinion of many people in conversation."[70] In the sixth edition of Origin of species (1872) he stated: "I formerly spoke to very many naturalists on the subject of evolution, and never once met with any sympathetic agreement."[71] In his autobiography written in 1876, Darwin recalled, "I occasionally sounded not a few naturalists, and never happened to come across a single one who seemed to doubt about the permanence of species".[72] When answering Galton's questionnaire in 1873, one of the questions was, did he have "Energy of mind?" Darwin replied that he did, and to prove it, wrote: "Shown by rigorous and long-continued work on same subject, as 20 years on the 'Origin of Species' and 9 years on Cirripedia." Darwin always described the years after first conceiving of his theory as the time he was working on it, never a hint that it was held back because the times made it difficult or impossible then to talk about his now triumphant views. And as the quotations all say, he talked with "many" people about it.

Milner quoted the same "oath" of office as Desmond and Moore in 1994 and twice again in 2009. He followed them in suggesting that there is at least an irony and at most a secret contradiction in Darwin's oath while being at the same time an evolutionist. But this was not the oath Darwin swore upon becoming a justice of the peace.[73] It could not be. As noted above, justices of the peace did not and could not try felonies in petty sessions. Furthermore, this quotation is not the oath of office at all but the wording used in written depositions in the higher criminal court of appeal.[74]

Milner 1994 and Milner 2009b gave an additional quotation: "In the same document, [Darwin] was also enjoined from doing 'anything to upset the religious values of the country.'"[75] In Milner 2009a the identical sentence is given again, but the sentence now beginning with "Ironically".[76] These remarks further the dramatic tension of Darwin embodying some sort of secret contradiction. It cannot be stressed enough that this is a mid-twentieth century re-interpretation of Darwin, absent in his own writings and of all those who knew him and a generation of writers after them.

As regards the second quotation by Milner, it cannot be located in any nineteenth-century publication and is not part of the oath of office of English justices of the peace. Indeed, any historian of the period ought to pause at reading it. This sounds very much like mid- to late- twentieth-century English, and not at all the (already by then) antiquated language used in mid-nineteenth century legal documents. The phrase "religious values" was not used in this sense at that time. Indeed, according to the OED, the plural "values" in this sense was not recorded in English until 1918. The quotation is therefore spurious and was presumably meant as a paraphrase. The oaths were not so ominous or indeed even meaningful or interesting. They were just a dull old-fashioned formality- a tradition- that was already centuries out of date.

In fact, we know from a recollection by Darwin's daughter Henrietta that the ceremony of swearing in was more laughable than solemn.

He was sworn in ? at Canterbury on the 8th day of some month & after swearing all kinds of oaths he had to write on 'this eighth day' over & over again & always spelt it eightth, as he remembered with disgust afterwards. …along w[ith] a country Sqr. a g[en]t[l] man who slurred over the words & whenever this happened the clerk gravely reproved my f.[ather] saying speak up or some such words.[77]

Far from trembling at the thought of swearing an oath that felt uncomfortable, Darwin instead told jokes about his spelling and how the country squire with him kept slurring the words.

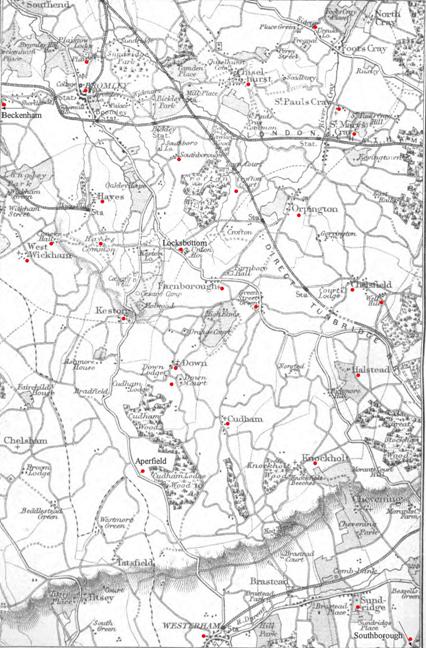

Darwin was, to use the most exact term, a county magistrate, which was distinct from justices of the peace of boroughs and ex officio justices of the peace.[78] County magistrates met monthly for a court of petty sessions. A "session" is the sitting together of a number of persons to adjudicate. A court of petty sessions was specific to the subdivision of a county. In Kent there were sixteen divisions. Darwin's division was Bromley. In 1861 there were twenty-two acting magistrates in the Bromley division. The Bromley petty sessions met on the third Monday of each month at 11am at the Bromley Court House about 10km from Down House or at The White Lion Inn (now Ye Olde Whyte Lyon), Locksbottom, near Farnborough Common, about 6 ½km from Down.[79]

The White Lion Inn in 1865. Courtesy of Dover Kent Archives.

A caricature of magistrates from Punch, 1861.

DARWIN'S FELLOW MAGISTRATES

Each of Darwin's petty sessions was presided over by two to five magistrates. During his years of attendance, ten other magistrates, men of particularly high status and wealth, sat with Darwin at one time or another. Their names and details are given below.

Richard Benyon Berens (1834-1916). MA, MD and Lord of the manor of Kevington, St. Mary Cray. Chairman of the Royal Veterinary College Association. Held a commission in the West Kent Yeomanry Cavalry, a magistrate from 1855 and Deputy Lieutenant for Kent. He served as High Sheriff for Kent in 1893.[80]

Col. John Farnaby Cator (1861, Lennard), (1816-1899). Seat Wickham Court, Beckenham, Kent. Educated at the Royal Academy, Woolwich. Received a commission in the Royal Artillery in 1835. JP 1854. 1880 Baronet, 1881 Chairman of the Bromley and Beckenham Joint Hospital Board, 1882 Chairman of the Kent County Council, senior JP for Kent. Bart 1880.

James Chapman (1797-1878). St Paul's Cray-Hill. Earliest record as JP 1830. 1871 nominated as Sheriff of England and Wales for the county of Kent.

Joseph Jackson (1778-1860). Mayfield Place, Orpington. Deputy Lieutenant and magistrate for the county of Kent. Earliest record as JP 1826. Remembered by the late Lord Sidney as "one of the best magistrates on the Bench."[81]

Frederick Mortimer Lewin (1798-1877). Halfway-street, Bexley, Kent. Appointed 1855 as JP. Register to the Zillah Court of Calicut Assistant judge and joint criminal judge of Salem. High Court Civil Service.[82]

George Warde Norman (1793-1882). Merchant, 1821-1872 a director of the Bank of England, Chairman of the Bromley Poor Law Union. A Utilitarian and Unitarian who later became active in the Church of England. Lived at The Rookery, Bromley Common, near Down. Much more detail is given on him below.

John Robert Townshend (1805-1890). MA, GCB, 1st Earl Sydney and third Viscount between 1831-1874. Of Foot's Cray, Kent. Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard and Lord Chamberlain to the Queen 1859-1866 and 1868-1874. Owner of Matson House and estate near Gloucester.[83]

William Waring (1818-1904). Lived at Woodlands, on Hawstead Lane, Orpington. Lord of Chelsfield Manor and Hewitts for fifty-three years, two of the four estates in the parish. Appointed JP in 1859.

Ford Wilson (1797-1863). Of Blackhurst, Tunbridge Wells. From a family of silk weavers with origins in Coventry. Earliest record as JP 1843. 1851 High sheriff of Kent.

John Joseph Wells (1804-1858). Of Southborough Lodge, Bromley. Landowner owner. JP from 1852.

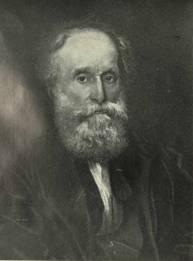

Oil painting of Col. John Farnaby (Cator) Lennard, c.1890. Maidstone County Hall. ARTUK |

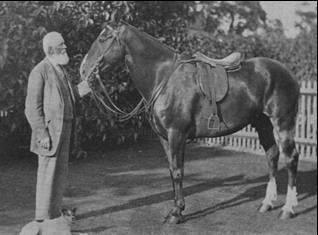

Carte de visite of John Robert Townshend, Viscount Sydney. Royal Trust Collection. |

Darwin's "clever neighbour" George Warde Norman. Engraving after an oil painting by G. F. Watts. |

Richard Benyon Berens. © National Portrait Gallery, London. |

William Waring. Bromley Borough Local History Society.

.

Report of Darwin qualifying as a magistrate. Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser, 7 July 1857.

On 3 July 1857 Darwin and two others "qualified as magistrates for the County of Kent."[84] The journalist or the typesetters mistakenly gave Darwin's residence as "Dover" rather than Down. But then Darwin couldn't even spell 'eighth'. He was purportedly provided with testimonials from the Rev. John Brodie Innes (1817-1894), perpetual curate of Down (c.1860-1869), and Sir John W. Lubbock, the wealthiest landowner in his neighbourhood and Sheriff of Kent in 1852.[85] Milner wrote that Lubbock "had talked [Darwin] into accepting…as part of a gentleman's duty to 'help maintain order in the neighborhood.'"[86] This purported quotation appears nowhere in the Darwin correspondence and is clearly not contemporary in its language or meaning. It is misleading to attribute imagined ideas of social control to Lubbock and Darwin for which we have no evidence.

Although one would not see it on his publications, becoming a justice of the peace entitled Darwin to use more letters after his name in addition to MA, FRS, FLS and FGS. Now a JP, the census survey interviewers habitually recorded such information. Thus the census records for Darwin show:

1861 "Justice of P. M.A. Author of scientific works…land & shareholder".

1871 "Shareholder…& J.P."

1881 "M.A., L.L.D.(Cambs), F.R.S., J.P."[87]

Incidentally, it seems never to have been pointed out before that Darwin stated his profession as "shareholder". Which, indeed, he was. Asked by Francis Galton in 1874 on a questionnaire if he had any "special talents" Darwin replied: "None, except for business as evinced by keeping accounts, replies to correspondence, and investing money very well."[88] 'Darwin the shareholder' would make an interesting and important study.

Darwin clearly took pride in being a JP and would single it out as one of his principal titles. In 1866 he drafted a biographical entry about himself in third person for Reeve and Walford's Portraits of men of eminence in literature, science, and art. Darwin wrote: "He has lived for the last 25 years since 1842 at Down near Farnborough Beckenham in Kent; & is a magistrate for that county".[89] In The Bromley directory for 1869, p. 11, he was listed under Down as: "Darwin Chas. R. esq. J.P. Down House". He was still listed like this in the 1876 directory, although by then the directory spelled both the name of the village and Darwin's house as "Downe".[90]

There are several references in the press reports below to the "Union-house", "Bromley Union" or "Union clothes". The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 saw the amalgamation of the older vestry and parish units for the responsibility for the poor. The new union workhouses were an attempt to supersede the traditional "outdoor relief" of payments to the poor. These amalgamated districts required larger centralized workhouses to house the poor. The Bromley Union comprised sixteen parishes, including Down, with a total population of about 7,000. The Bromley Union workhouse was built in 1844 at Locksbottom. There were 220 residents in 1861. By the 1930s the building had been demolished.[91]

When it comes to workhouses, modern readers tend to think of the image painted by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist (1838) where Oliver famously asked "Please, sir, I want some more". But that was a parish workhouse before the new poor law and its supposedly more modern workhouses. Life in the new workhouses was not quite so bleak, but it was not a pleasant place either. They were explicitly designed to discourage able-bodied workers from shirking and to ensure that only the absolutely destitute sought refuge there. On entering a workhouse, one had to give up one's own clothing to be disinfected and stored. Residents were given standard Union clothing, colloquially called a uniform. Men might be given a striped cotton shirt, jacket, trousers and a cloth cap. Women were often given a blue-and-white striped dress and smock. Men, women and children were housed separately in the workhouses. Residents were provided with a healthy, if not very interesting diet.

Able-bodied residents were also expected to work, sometimes justified as giving them useful skills but in some workhouses it was just an attempt to turn a profit from the free labour by the organizers. Men often worked at stone-breaking and oakum picking and females too did oakum picking as well as domestic work to maintain the workhouse such as mopping the floors. Discipline was strictly enforced. For swearing or pretending to be sick one's food ration could be cut for up to two days. Insubordination or violence could lead to confinement for a day.

Map from Anon. 1882. Round Bromley and Keston: A handy guide to ramblers in the district, with a …bicycle route. London. Many places mentioned in the reports are indicated with a dot.

DARWIN'S PETTY SESSIONS

We have found records which explicitly name Darwin as on the bench or judging criminal cases on at least twenty-eight occasions between 1857 and 1862.[92]

1857 Sept. 21 Bromley.

1857 Nov. 16 Bromley.

1858 Jan. 18 Farnborough.

1858 Feb. 15 Bromley.

1858 Mar. 15 Bromley.

1858 Apr. 19 Bromley.

1858 May 17 Bromley.

1858 Jun. 21 Bromley.

1858 Aug. 16 Bromley.

1858 Sept. 20 Bromley.

1858 Oct. 18 Bromley.

1858 Dec. 20 Bromley.

1859 Jan. 17 Chelsfield.

1859 Feb. 21 Bromley.

1859 Mar. 21 Bromley.

1859 Apr. 18 Bromley.

1859 May 16 Bromley.

1859 Jun. 20 Chelsfield.

1859 Aug. 15 Bromley.

1859 Sept. 19 Farnborough.

1859 Dec. 19 Bromley.

1860 Jan. 16 Farnborough.

1860 Feb. 20 Bromley.

1860 Mar. 19 Farnborough.

1860 Aug. 20 Farnborough.

1860 Sept. 17 Farnborough.

1861 Dec. 16 Farnborough.

1861 Dec. 20 Down.

1862 Jan. 20 Locksbottom.

1862 Feb. 17 Farnborough.

Being a magistrate was sometimes very taxing for Darwin. Emma Darwin wrote to their son William who was then at Rugby: "The other day when Papa was doing some justice work in the dining room [eight-year-old] Lenny went upstairs to [the governess] Miss Pugh saying 'There is Papa being Judge, jury & policeman all himself.'"[93] In the same year, Darwin cut short a visit to London because, as he wrote to William: "On Monday 20th I have to attend Magistrates meeting".[94] Clearly he attended when he could, his notorious ill health permitting.

In 1848 he had asked to be excused from jury duty on grounds of ill health. Can we conclude, as is so often claimed, that he was shirking and using his health as an excuse when he spent so much time working as a magistrate?[95] On 24 June 1858 Darwin, as magistrate, certified the "Declaration by William Stow of Farnborough, yeoman, about brothers' marriages".[96] In 1864 Darwin gave advice to John Scott (1838-1880), a young Scottish botanist, who wished to seek employment in India. A character reference from a magistrate was one possibility Darwin recommended. "If you decide to try the plan and run such risk as there is of not getting employment, can you get a character for probity, sobriety and energy, from Professor Balfour, Mr Macnab, or any clergyman or magistrate of the district in which you reside. These would be of important service."[97] Scott did secure a post at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Calcutta. On 9 October 1869 Darwin wrote to the secretary of the Friendly Club in the neighbouring village of Westerham.

Sir

Mr W. Reeves in this place has called on me as a County Magistrate to consult me on the best means of obtaining the payment which he states is due to him from the Westerham Club.—

I can testify that the condition of his hand shows that he is unable [to] work, & as he cannot at present write, he has asked me to address you on the subject,—before he takes any further steps.— His case seems a hard one, I am informed that some of your members still receive payment, & if this be correct it wd be difficult to justify, any one member who may have a just claim being refused.

Hoping that you will be able to satisfy W Reeves' claim. I beg leave to remain

Sir I Your obed sert

Ch. R. Darwin.[98]

The key line here being "I can testify". This was one of the functions of a magistrate, they were a trustworthy authority and had the "power to administer oaths".[99]

The final record that survives of Darwin acting as magistrate comes from 28 January 1881 when he wrote to his protégé George John Romanes (1848-1894): "I am daily bothered to give orders as a magistrate for animals to cross from one field to another on the same farm, if across any road!"[100] This was only necessary because of a recent outbreak of swine flu which had caused the authorities to restrict the movement of livestock in the southern counties.

Rates

Magistrates set the local rates (similar to taxes). Darwin oversaw all of the following. There was a district gas-rate to pay the local gas company but only for properties that had gas lighting. The lighting-rate was to pay for public street lighting. These gas lamps were likely lit only eight months of the year from sunset to 2am. The poor-rate was a tax on property levied in each parish to provide poor relief. Magistrates also had the power to renew, or deny, the licenses of public houses.

On 14 May 1858 Darwin wrote to his son William about Ainslie again: "I have this minute returned from a Vestry [meeting at Down church] to compel that beast, Mr Ainslie, to pay a Church-rate; but he has floored us.— I have great hopes that the beast is ruined & will soon be clear of the village."[101] The editors of Darwin's correspondence noted: "The church rate was a tax levied on landowners in each parish for the benefit of the parish church. The church rates were set by the churchwardens, together with parishioners in the vestry. Although it was a compulsory personal charge, collecting the tax often proved problematic, particularly from nonconformists who objected to supporting the established church".[102] And Ainslie was a nonconformist.

As the records below reveal, Darwin was amongst the magistrates who met on 19 April 1858 when Ainslie was summoned on this matter. It was reported that: "Mr. Ainslie still disputing the validity of the rate, an arrangement was come to, by which the churchwardens will call a vestry meeting to consider the subject, and they will be guided by the decision of the meeting in any further steps it may be necessary to take."[103]

The vestry book at St Mary's church in Downe records "1858 Apr./May: Mr Darwin and Mr Parslow involved in a dispute between the churchwardens and Robert Ainslie about his non-payment of the church rate. Mr Darwin moved that 'no further legal proceedings be taken in the matter of the Church rate which Mr Ainslie refuses to pay'".[104] Mr Parslow was, of course, Joseph Parslow (1812-1898), Darwin's manservant and then loyal butler from c.1840-1875.

Darwin suggested letting Ainslie off, but this is not what ultimately transpired. On 27 September 1858 Ainslie was "summoned [before the Bromley magistrates] for non-payment of poor-rate for the parish of Down. The amount was 1l. 18s. 10d. The defendant complained of being summoned without having received any notice requiring him to pay the amount. - The bench told Mr. Ainslie the rate must be paid, and ordered him also to pay the costs."[105] Ainslie would have been compelled to pay or face imprisonment by default. By October 1858 he had left Down and Emma Darwin hoped to buy some of his furniture if suitable.[106] Ainslie was mentioned once more by Darwin, in 1876, as having once been a trustee of the Down Friendly Society, but having left many years before, his whereabouts were unknown to Darwin.[107] The Society met at the George Inn in Down from 1850 until 1882, the year Darwin died.

Crime & punishment

Theft was the most common crime brought before Darwin as a magistrate.[108] Defendants before him were charged with stealing potatoes, hazel nuts, plums, apples, beer, pieces of wood, parts of fences, trusses of hay, an iron hurdle, a coat and ash poles. Other common crimes were disorderliness, drunkenness and mischief. There was one case of a deserter from the army being caught and one case of illegal gambling. More frequent were cases of assault. These were usually very minor and in only one case involved a man making a threat with a knife. Others were charged with damaging property such as breaking windows or fences, especially the latter. Trespassing was also fairly common.

Poaching was the next most common crime. It was at the time an escalating trend. There were around 9,000 convictions for poaching in 1860.[109] When one case was assessed with Darwin present, one of the other magistrates, Mr. Berens, had the right of sport over the property in question. He therefore excused himself from taking part in that particular decision, as in law "interested justices should not act".[110] Another case of a magistrate having a possible interest in a case was that of a lad accused of setting his dog to worry some sheep on the land of Col. Cator, who was one of the magistrates at the bench that day. The lad was fined 5s and costs. It was not recorded whether Cator excused himself from the judgment.[111]

We have a rare glimpse of the private view of one of Darwin's fellow magistrates on a case of poaching from December 1859. George Warde Norman wrote in his diary:

Smith caught three men shooting in Barnet & was able to recognize 2 of them & of whom proceedings will be taken. They threw away 5 Pheasants. I shall also have to summon 9 men who persist in shooting on my alders every Sunday. I would willingly overlook the latter offence, as I do not attempt to preserve the alders, but the [process] of opinion on all sides, prosecution.

The Poaching prosecutions are very disagreeable, but how can they be avoided? All the offenders in the above cases are old Hands, who habitually violate the Law, without the least excuse from poverty & infringe upon rights of Property—[112]

Darwin's daughter Henrietta recalled that he once encountered a poacher during his morning walk.

But he kept up the very early morning walk for years. It used to be almost in the dark in winter & he had a story of how he had surprised old Duke poaching out by the big woods & was offered the pheasant he had just seen shot as a bribe to make him say nothing.[113]

Whether Darwin took the pheasant let off old Duke was not recorded.

Others were fined for disobeying the laws of the public roads such as riding without reins or recklessly driving a horse and cart and one man was charged for exceeding the speed limit, which was 4 miles an hour! Others were charged with evading tolls on toll roads by going through fields to avoid them. There were several cases of men fined for allowing ferocious unmuzzled dogs to run loose. It appears from the reports that being attacked or bitten by a dog was not uncommon in the district.

In 1858, Johanne Spellard, a blind Irishwoman, was charged with tearing up her clothes in theBromley Union workhouse. In her defence, she said she was ashamed to go out in her old clothes and that she had been "very 'tossicated" at the time."[114] She was sentenced to one month's hard labour. In 1861 Darwin sentenced a man (a serial offender) to fourteen days hard labour for absconding from the Bromley Union workhouse in Union clothes.[115]

Most recorded cases reveal that the magistrates tried to act fairly, letting off those with no previous convictions with only a nominal fine or only court costs. In another case, a man accused a woman of using abusive language against him on the high-road. However, the magistrates were told that the accuser had got the woman pregnant whereby she "had been brought to utter ruin". Hearing this the magistrates "severely rebuked the complainant for his heartless conduct, and dismissed the case, leaving him to pay the costs."[116]

Magistrates were not always forgiving and lenient. In August 1870, after Darwin had ceased to attend petty sessions, Stephen Holder, a carter from Orpington, was charged with illegal gambling, specifically, playing pitch-and-toss on the 13th. Pitch-and-toss is a game in which the player who throws a coin nearest to the mark gets the first chance at tossing up all the coins so far played and winning all those that fall heads up. Holder pleaded not guilty, stating that he had merely stopped to watch the game after feeding his master's horse. When the police constable was spotted, all of the assembled men ran away. Only Holder was apprehended. Despite his plea that he had only been a spectator and didn't even have a penny on him, and the policeman even said he was of good character, the Bromley magistrates committed him to two months' hard labour. The chairman, Col. John Lennard, warned "if you come before us again we will give you three months." The newspaper reporter noted: "Prisoner appeared overwhelmed at the decision, and begged the chairman not to send him to prison, but the chairman directed the police to remove him to the cells."[117] All those present were shocked. Several London newspapers later took up the story, outraged by what they saw as the incommensurate severity of the sentence for such a minor infraction.[118]

The next day, Holder's employer, George Groombridge, wrote to the editor of the Daily Telegraph & Courier: "I, as the employer of Stephen Holder, beg to express the astonishment of myself and every one else at such an outrageous sentence as two months' hard labour without the option of a fine; and that on the evidence of a single policeman. I can add my testimony to the sergeant's, and give the man a good character."[119] The conservative Pall Mall Gazette pointed out that sending a man of good character to prison might see him come out with a bad character and that this might be cause for alarm for the country magistrates' "partridges and pheasants, if not of their forks and spoons".[120]

Poaching was not always for the pot as there were in many areas intricate networks for the sale and redistribution of the booty.[121] On 20 August the Daily Telegraph & Courier also cast aspersions on the magistrates as "the great unpaid". This was a common derogatory nickname for country magistrates because they were unpaid amateurs who had no legal training or qualifications. Indeed, practising lawyers and solicitors were ineligible to become magistrates in England and Wales. It was a common stereotype by newspaper journalists and the satirical magazine Punch to lampoon and chastise country magistrates as primarily motivated to preserve their game from poachers.[122] Judging from the prevalence of cases of poaching and trespassing, this does not seem to have been entirely unfounded. Even fifty years later, magistrates were still sometimes an object of ridicule. P. G. Wodehouse once described the reputation of magistrates in the 1920s through the voice of his character Bertie Wooster: "Well, you know what magistrates are. The lowest form of pond life. When a fellow hasn't the brains and initiative to sell jellied eels, they make him a magistrate."[123]

"Magistrate (in an undertone to his colleague). 'This man has been so often before us for poaching, I think we should fine five pounds'.

Prisoner (overhearing). 'You needna pench yourselves, gen'lemen!—For deil a penny ye'll get!'" Punch, 1 Oct. 1881.

"Squire Bobbins, with a view to grouse driving later in the season, employs the country boys to shy turnips over the wall for him to practise at. Sometimes the young rascals take a better aim than the old gentleman!" Punch, 16 Sept. 1882.

"Short-sighted Swell (to Gamekeeper, who has been told off to see that he 'makes a bag''). 'Another hit, Wiggins! By the way—rum thing—always seem to hear a shot somewhere behind me, just after I fire!'

Wiggins (stolidly). 'Yes, Sir, 'zactly so, Sir. Wunnerfle place for echos this 'ere, Sir!'" Punch, 19 Nov. 1881.

The same day that Groombridge's letter was published, at a meeting of the Greenwich Advanced Liberal Association, a resolution was passed expressing indignation at the severity of the punishment by the Bromley magistrates and expressed the hope that the Home Secretary (Henry Bruce, Lord Aberdare) would get Holder released.[124] Also on the same day, Frances Power Cobbe (1822-1904), the Anglo-Irish journalist and founder of the Anti-Vivisection Society in 1875, published an article in the daily halfpenny London newspaper the Echo condemning Holder's sentence.

On the same day, Darwin wrote in a postscript to a letter to Cobbe: "I forgot to say that I wrote as J.P: for Kent to Home Secretary, calling his attention to Holder's case."[125] The letter to the home secretary does not survive. Surprisingly, Cobbe then published a modified letter from Darwin and addressed it to the editor of the Echo (where she was a staff writer from 1868 to 1875):

Sir,

I have read your admirable and most just article on "Even-handed Justice," [the one by Cobbe] and beg to say that if anyone who sympathises with the case be disposed to open a subscription for the benefit of Stephen Holder, I should be happy to contribute to it £ 1.—

I am, Sir, yours &c.

Charles Darwin

Down, Beckenham, Kent.[126]

The modification was done without Darwin's knowledge or consent. Darwin's daughter Henrietta later wrote: