[page] 63

THE LIBRARY.

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS.*

Dr. Hooker's address to the British Association last year made the public aware that Mr. Darwin has been for a length of time engaged in the investigation of certain plants which he conceived to be endowed with insectivorous properties, and that a work from his pen, fully detailing the views and the facts on which they are founded, might soon be looked for. That work is now before us. Its main purport is to prove the proposition announced for him by Dr. Hooker, three-fourths of it being taken up with the facts, experiments, and inferences, drawn from one or two of the most strikingly-endowed species; but there is also a considerable amount of very interesting secondary matter relating to other allied species which he had examined in less detail. To give a fair idea of the book it would require to be viewed from two different

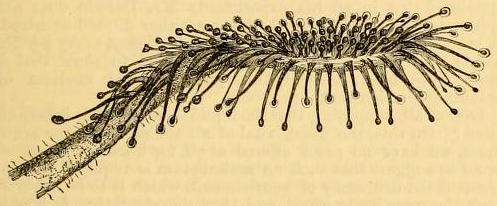

Fig. 1.—Drosera rotundifolia. Old leaf viewed laterally; enlarged about five times.

stand points, one looking to the general question opened up by Mr. Darwin, whether the plants in question are carnivorous or not; the other accepting that position, and, on it as a basis, examining the different means by which the end is attained, or supposed to be attained, in different species. We have not space for an examination of the work from both points of view; and, therefore, as the abstract question has, perhaps, at this time mostinterest for our readers, we shall confine ourselves to a review, necessarily very brief and imperfect, of

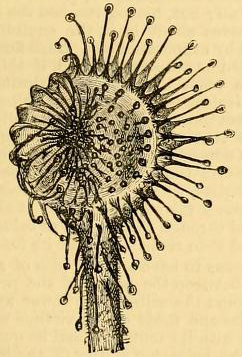

Fig. 2.—Drosera rotundifolia. Leaf (enlarged), with the tentacles on one side inflected over a bit of meat placed on the disk.

the proof brought forward by Mr. Darwin, and an enquiry into how far it seems to be conclusive.

The broad proposition maintained by Mr. Darwin is, that certain plants, which he indicates, chiefly belonging to the Droseraceæ or Sundews, are insectivorous. This entails the minor positions, that they catch insects, that they kill them, that they swallow and digest them—that is, absorb their juices, and assimilate them. All this Mr. Darwin maintains that they do. They catch them, some (as Drosophyllum) by the secretion and exudation of a viscid fluid, to which any insects that alight on it adhere in the same way that they do to the sticky gum surrounding the bud of the Horse Chestnut or the corolla of many Cape Heaths, for neither of which is any carnivorous power claimed by Mr. Darwin; others (as the various species of Drosera, especially Drosera rotundifolia) by the use of sensitive appendages on the leaf as shown in fig. 1, which is a side view of the leaf of D. rotundifolia. These have been well named tentacles by Mr. Darwin. Each is tipped with a knob, from which oozes a slimy secretion (from the glittering of which, in the sun, the plant has received the name of Sundew), and each has the power of bending, either independently or conjointly with the rest, covering and detaining by their secretion any small insect that they may have captured. Fig. 2 shows one-half of them so bent over, and the other erect. In a third species, Venus' Fly-trap (Dionæa muscipula) the tentacles are replaced, or, at least, their office is performed by a series of spines along the margin of the leaf, like a chevaux-defrise, which, when the two sides of the leaf close together, interlace, and act as prison bars, preventing anything between the sides escaping. In a fourth plant (Utricularia vulgaris, a water plant common in ditches in some parts of England), the leaves bear bladders, which have an opening closed by a sensitive valve, which opens mysteriously for the admission of insects, but closes firmly against their exit. All the latter contrivances, it will be seen, depend on a power of motion in certain parts, apparently at the will of the plant, but in reality under the stimulus of some existing cause, which induces the required action. This irritability or sensitiveness is no new thing in plants; it is present in many, as, for example, the Sensitive Plant, where it is not thought to be necessarily of beneficial use to its possessor; and, although its existence has

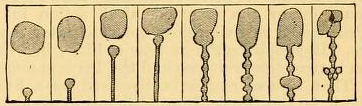

Fig. 3.—Drosera rotundifolia. Diagram of the same cell of a tentacle, showing the various forms successively assumed by the aggregated masses of protoplasm.

been disputed or denied in some of those in which Mr. Darwin has proved it, we do not imagine that anyone would, even before seeing his proofs, have hesitated to concede it to most of his carnivorous species; and he himself does not claim it for all. It is not, therefore, the irritability that is the extraordinary thing; it is the excitation that sets it in motion, and the subsequent action. Almost any kind of interference with the tentacles of Drosera rotundifolia will set it in motion, such as brushing the tentacles, placing inorganic substances upon them, and, most efficient of all, placing organic matters upon them, especially such as contain nitrogen. The rapidity with which this action is induced varies according to the size and nature of the object, the vigour of the leaf, and the temperature of the day; and the time the tentacles take to bend completely over the object is from one to four or five hours; it remains thus folded from one to seven days, and the more soluble the matter is that is dealt with, the longer it remains upon it.

The next step in the process (next, although almost simultaneous) is what Mr. Darwin calls the digestion of substances on the leaf. The term digestion, however, has two meanings—one, the chemist's meaning, who, when he speaks of digestion, means little more than solution; the other, the colloquial meaning, which comprehends solution, absorption, and assimilation. Mr. Darwin generally uses it in the technical or chemical sense, although we are not sure that he does not sometimes, perhaps unconsciously, use it in the more comprehensive one. But, at any rate, it seems to us that in the full meaning of this term lies the gist of his proof. His experiments certainly prove solution, and probably absorption; but, although he cites various probabilities in its favour, we cannot lay our hand on any proof, or even attempt at proof, of assimilation. The successive steps in the digestion claimed by Mr. Darwin are: first, a more copious secretion from the glands surrounding the object; next, a change in its quality, from being either exclusively neutral, or only very feebly acid, into an acid which is not hydrochloric acid, but, as near as can be made out, an acetic acid called propionic, and allied to

* "Insectivorous Plants." By Charles Darwin. Murray. 1875.

[page] 64

butyric and valerianic; then a fermentative agent, of the nature of pepsin, which Mr. Darwin has been unable to detect, but whose presence he is satisfied of from circumstantial evidence. The reader is aware that something more is needed to digest food in the stomach of animals than the weak hydrochloric acid, which is the principal ingredient in gastric juice; a sort of fermentative agent, named pepsin, has to be added to it to enable it to do its work. The phenomena of the leaf of the Drosera suggest that something similar must be contained in its secretion. Mr. Darwin shows that there is a number of points of resemblance between the active secretion of Drosera and gastric juice, some of which appear of real weight, others open to objection. In the nature of things it must obviously be scarcely possible to detect it chemically, the quantities being so minute; but that is no reason for accepting an uuproved conclusion.

We regret that we have not space to go into the various ingenious reasonings by which Mr. Darwin shows that the presence of something like pepsin is almost certain. We would only make one remark on the subject, applicable both to pepsin in gastric juice and pepsin anywhere else, viz., that it may be an organic product of the chemical action going on between the hydrochloric acid or other acid, and the matter it is dissolving, and not an agent contributed by the living stomach or its substitute at all. It has, we believe, never been obtained but in the half-digested food, nor has its origin been explained. The air and food may first make it, and then use it. We know that there are plenty of instances of the production of organic matters through chemical action. If this be so with pepsin, then its presence both in the animal stomach and on the leaf in Drosera is no more remarkable than that the same result should follow the same chemical action in different places. Practically, this view does not much alter the position of matters. It simplifies the process a little, but leaves the parallelism between gastric juice and the Drosera secretion untouched. That animal matter is dissolved by a living acid, alike by both, is the great point, although a combination of more than one process to effect the result, would, of course, have strengthened the implication that that was the specific result aimed at.

Subject then to any correction which Mr. Darwin's experiments may hereafter receive from subsequent observers, which, from personal verification of a fair portion of them, we can say will not be much, we may assume as proved that insects and other nitrogenous matters caught or placed on the leaves are dissolved. What is done with the solution is the next question. Is it absorbed? Mr. Darwin says that it is. "That the glands possess the power of absorption is shown by their almost instantaneously becoming dark coloured when given a minute quantity of carbonate of ammonia, the change of colour being chiefly or exclusively due to the rapid aggregation of their contents." Of Pinguicula, he says that "the secretion, when containing animal matter in solution, is quickly absorbed, and the glands, which were before limpid and of a greenish colour, become brownish, and contain masses of aggregated granular matter. This matter, from its spontaneous movements, no doubt consists of protoplasm." But there is something in his account of the same phenomenon in Drosera which gives us pause. He there gives two figures of a cell of a tentacle, showing the various forms successively assumed by the aggregated masses of protoplasm, of which fig. 3 is one, and says:—"If a tentacle is examined some hours after the gland has been excited by repeated touches or by inorganic or organic particles placed on it, or by the absorption of certain fluids, it presents a wholly changed appearance. The cells, instead of being filled with homogeneous purple fluid, now contain variously shaped masses of purple matter, suspended in a colourless or almost colourless fluid; and, shortly after the tentacles have re-expanded, the little masses of protoplasm are all re-dissolved, and the purple fluid within the cells becomes as homogeneous and transparent as it was at first." If these phenomena were always and only subsequent to solution, there would certainly be strong grounds for supposing that they belonged to absorption; but the fact that they follow mere mechanical irritation, and are, as shown by Mr. Darwin, independent of secretion, seem to indicate something else, and are, possibly, rather connected with the phenomenon of irritability. But, even although the leaves do absorb, it does not follow that they absorb without distinction; they may be capable of absorbing the water in the solution, and yet not capable of absorbing the nitrogen, or they may be able to absorb both, but the one may be to their benefit and the other to their detriment. It is a remarkable thing that if they are so greedy of nitrogen as Mr. Darwin's theory assumes, and take all these pains to absorb it in the liquid form, they absolutely decline to absorb it in the gaseous form. Though nitrogen gas constitutes by far the greatest part of the mass of the atmosphere, seeds will not germinate in it, neither will plants vegetate. Contradictory experiments are on record, indeed, as to the power of different plants to resist its deleterious effects, but both in those where the plants died and in those where they lived it was found that no use had been made of the nitrogen. Its quantity in all was found to be the same after the experiment as before it, and we are disappointed that in all his experiments Mr. Darwin does not appear to have tried any with this gas, either diluted or mixed. It is true that nitrogen is to be found in almost every part of plants, but the experiments above alluded to show that it must have been derived through the usual medium of obtaining nourishment—the roots.

Last of all, supposing that the liquid is absorbed, is it assimilated? On this, the most vital of all the points of the argument, we have no proof offered at all, for it cannot be called proof to suggest that such an assimilation is required to supplement the deficiency of nourishment, which is to be inferred from the roots being small, and that, therefore, that is how it is disposed of. In the first place, we do not admit that the root apparatus is deficient or disproportionately small. It is small, but so is the plant; and it is semi-aquatic, so that it can more quickly take up its nourishment; and, in the next place, if the provision of roots is deficient, the leaves do not seem the organs which we should expect to be used to supply the deficiency. All the observations of late years point to a reversal of the old theories of circulation of the sap from the root to the leaf, and back again from the leaf to the root. There is, we believe, no such circulation There is simply ascent from the root. There is, no doubt, an anastomosing circulation in the leaves, as there must necessarily be, if the whole of the leaf is to be supplied at all; but, having reached the leaf, the sap goes no farther; it moves about in it, the equilibrium being constantly disturbed by evaporation and fresh flow from the root, until it is deposited or evaporated; and, if this be so, to propose to nourish a plant by absorption through the leaves is pretty nearly equivalent to set about nourishing a man through other channels than those by which he is usually fed. Further, we may observe that the idea of its being possible for a plant to take up nourishment in the way supposed, if true, will militate against the views of Dr. Voelcker and other chemical physiologists, who seem to have come to the conclusion that plants never take up crude food at all, but only such as has first passed through the process of being converted into a mineral salt and then re-dissolved for its food.

Mr. Darwin seems to have a vague idea of some analogy or relation existing between the action of the protoplasm in the cells of the plant and the cells of the lower animals; that as the hydra encircles and feeds on its victims with its arms, so the Drosera does with its tentacles, and he quotes Mr. Sorby's examination of the colouring matter of the leaf of the latter with the spectroscope, who found it to consist of the commonest species of erythrophyll, which is often met with in leaves with low vitality; but we must not allow ourselves to be led astray by fanciful analogies. There ought not to be much difficulty is ascertaining, by practical experiment, whether the teleological reason suggested by Mr. Darwin is the true one or not. Let two plants of Drosera be grown under the same conditions, the one well supplied flies, and the others protected from them, and see which thrives best. According to Mr. Darwin, the non-insectivorous one should be starved, although from the small amount of nourishment that the other could derive from flies during the six months of their existence, at the rate of a meal of two or three midges once or twice a week, we could not, according to our view, credit its embonpioint to high nitrogenous living. Of course those who do not

[page] 65

accept Mr. Darwin's views must be prepared to be called upon to supply some other explanation of the very curious phenomena under consideration, if they will not adopt his. This was the constant reserve brought up when driven to their entrenchments in the discussion on the origin of species—not, indeed, by Mr. Darwin but by his followers. But the answer is the same now as then. That is not our business; we do not pretend to give an explanation of everything, least of all a teleological one; all that we do is to say whether, in our judgment, those who do have hit upon the true one or not. From what we have said, it will be seen that, in this instance, we think that Mr. Darwin has not, but we are none the less grateful to him for the instruction and information contained in his delightful volume. Mr. Alexander Dumas makes his great hero, the Count of Monte Christo, say that whatever he does he does well. With much better warrant may we say this of Mr. Darwin, and, notwithstanding our different views, of none of his works with more truth than that at present under review.

A. M.

[title page]

ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY JOURNAL

OF

GARDENING IN ALL ITS BRANCHES.

FOUNDED BY WILLIAM ROBINSON, Author of "Alpine Flowers," &c.

THIS IS AN ART WHICH DOES MEND NATURE: CHANGE IT RATHER: BUT THE ART ITSELF IS NATURE.—Shakespeare.

VOL. VIII.

LONDON:

OFFICE: 37, SOUTHAMPTON STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C.

CHRISTMAS, 1875.