[front cover]

CHARLES DARWIN

and the voyage of

the Beagle

[frontispiece]

Charles and Catherine Darwin, 1816

[page ii]

CHARLES DARWIN

AND

THE VOYAGE OF THE BEAGLE

Edited with an Introduction

by

NORA BARLOW

LONDON

PILOT PRESS LTD.

1945

[page iii]

FIRST PUBLISHED DECEMBER, 1945,

BY PILOT PRESS LTD., 45 GREAT

RUSSEL STREET, LONDON, W.C.I.

BOOK PRODUCION WAR ECONOMY STANDARD

This book is printed in complete

conformity with the authorized economy

standard.

Printed at The Chiswick Press, LONDON, N. 11,

by Eyre & Spottiswoode, Ltd.

[page iv]

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| PREFACE .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 1 | |

| Part 1 | ||

| INTRODUCTION | ||

| CHAPTER I. | THE ENGLISH SCENE .. .. .. | 7 |

| CHAPTER II. | EDUCATION .. .. .. .. | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | THE OFFER .. .. .. .. | 22 |

| CHAPTER IV. | CAPTAIN ROBERT FITZROY .. .. | 33 |

| Part 2 | ||

| THE LETTERS .. .. .. .. .. .. | 40 | |

| Part 3 | ||

| THE NOTE-BOOKS: INTRODUCTION .. .. .. | 149 | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1832 .. .. .. .. .. | 155 |

| CHAPTER II. | 1833 .. .. .. .. .. | 170 |

| CHAPTER III. | 1834 .. .. .. .. .. | 217 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 1835 .. .. .. .. .. | 231 |

| CHAPTER V. | 1836 AND AFTER .. .. .. | 250 |

| GLOSSARY .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 269 | |

| INDEX .. .. .. .. .. .. .. | 275 | |

[page v]

[page vi]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Plate | ||

| Charles and Catherine Darwin, 1816. From a coloured chalk drawing by Sharples, in the possession of descendants of the Wedgwood family Frontispiece | ||

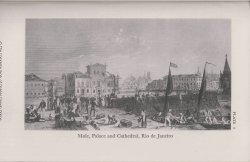

| 1 | Mole, Palace and Cathedral, Rio de Janeiro. From a drawing by A. Earle, the artist engaged by FitzRoy at the beginning of the voyage. Reproduced from the official Narrative of the Voyages of H.M.S. Beagle, 1839 .. .. .. .. .. Facing p. | 72 |

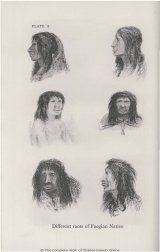

| 2 | Different races of Fuegian Native. From drawings by Captain Robert FitzRoy, ibid. .. .. Facing p. | 73 |

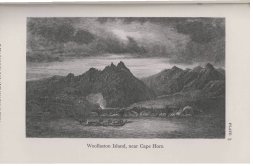

| 3 | Woollaston Island, near Cape Horn. From a drawing by C. Martens, who joined the Beagle on Earle's departure, ibid. .. .. .. .. Facing p. | 88 |

| 4 | Berkeley Sound and Port Louis, Falkland Islands. From a drawing by C. Martens, ibid. .. .. Facing p. | 89 |

| 5 | The River Santa Cruz: (a) Repairing boat; (b) Distant Cordillera of the Andes; showing method of towing the three boats, the men hauling the line just visible on the left bank; (c) Beagle laid ashore for repairs. From drawings by C. Martens, ibid. Facing p. | 104 |

| 6 | Remains of the Cathedral at Concepcion ruined by the great earthquake of 1835. From a drawing by J. C. Wickham, ibid. .. .. .. Facing p. | 105 |

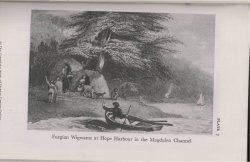

| 7 | Fuegian Wigwams at Hope Harbour in the Magdalen Channel. From a drawing by P. P. King, ibid. Facing p. | 120 |

| 8 | Fuegians going to trade with the Patagonians. From a drawing by Captain FitzRoy, ibid. .. .. Facing p. | 121 |

| 9 | Cordillera of the Andes, as seen from Mystery Plain, near the River Santa Cruz. From a drawing by C. Martens, ibid. .. .. .. .. Facing p. | 152 |

| 10 | Mount Sarmiento. From a drawing by C. Martens, ibid. Facing p. | 153 |

| 11 | Pages from the pocket-books, showing Darwin's diagrams of the geology of the Andes .. Facing p. | 168 |

| 12 | Beagle Channel. From drawings by C. Martens, ibid. Facing p. | 169 |

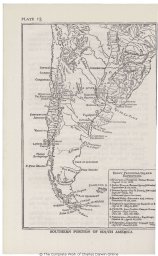

| 13 | Southern Portion of South America .. .. .. p. | 256 |

| 14 | Darwin's house in Gower Street after the bombing in the Spring of 1941 .. .. .. .. Facing p. | 258 |

| 15 | Mount Sarmiento. From a drawing by C. Martens, ibid. Facing p. | 259 |

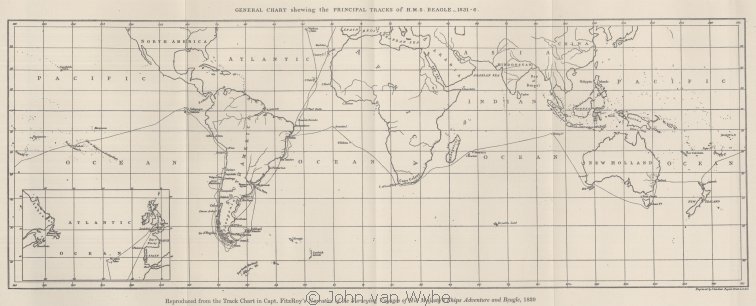

| Track chart of the Voyage of the Beagle .. Facing p. | 280 |

[page vii]

[page 1]

PREFACE

"THE VOYAGE of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career."

So wrote Charles Darwin towards the end of his life, looking back over almost half a century of quiet stay-at-home existence to the glorious adventure of his youth, when as a young man of twenty-two years he set sail on the voyage of circumnavigation which his name has rendered famous.

The Admiralty instructions to the commander, Captain Robert FitzRoy, were comprehensive, and gave as the main purpose of the expedition the accurate survey of the southern coast-lines of the South American continent, together with running a chain of chronometric readings round the world. Much subsidiary work was recommended, such as taking angle readings of all remarkable headlands and making exact geological maps of the countries visited. FitzRoy was already well acquainted with those southern regions of South America where he had spent some years on an earlier surveying voyage, and had already felt the need of someone more versed in scientific knowledge to assess the future mineralogical values of those lands. His zeal to promote the success of the second expedition led him to approach the Hydrographer for permission to place on the Beagle's books as his guest someone equipped with this additional knowledge, who would share his own accommodation and profit by the opportunity of visiting remote and unknown countries difficult of access. He little knew that his disinterested action would make his small sailing vessel forever famous in the history of science; the Beagle was to become the training-ship for Charles Darwin in the serious scientific purpose of his life.

His name will always be principally associated with the theory of evolution; the present volume, built round the little note-books of the voyage and his letters home, deals with an earlier period when hypotheses were still in the making and the orthodox doctrines of creation and immutability of species still

[page] 2 DARWIN

held their outward sway. During those five years he pursued the evasive geological puzzles that met his inexperienced eyes and made vast collections of animals and plants, but to begin with he had no guiding hypothesis on the species question to direct him. His power of building theories and testing them by the closest scrutiny of observed facts only came to him as a revelation on his travels. In the unpublished MSS. of these formative years can be traced the influences at work on his mind and character; he left England a diffident young man with no particular attainments, destined for the Church—if his despairing father could persuade him to apply himself seriously to a professional life; who only after some months began to believe, "if he could so soon judge, that he would do some original work in Natural History". He learnt to realise that "a man who dares to waste one hour of time, has not discovered the value of time", and returned with the certain knowledge that he could add both fact and theory to the great treasure-house of science.

Twenty-four little pocket-books have survived the distant travels and the passage of time. The notes are mainly geological, but they also tell of inland expeditions made whilst FitzRoy was charting the coast or the Beagle was refitting, with memoranda and odd comments of the traveller. In their pages his impressions pour forth with an almost devotional enthusiasm; that they are hastily scribbled and intended for no eye but his own is obvious. But the lapse of more than a hundred years, with all that was to ensue from these fragmentary records, has given them a value like that of the first and imperfect impression of a precious etching.

Parallel with the note-books the story is told in the thirty-nine letters written to his father and sisters from the remote corners of the earth in the form of an intimate personal narrative. These letters tell their own story and I have only added an occasional foot-note and here and there a connecting thread. I have taken some liberties with the punctuation in both the MSS., but hope I have always interpreted the indistinct handwriting correctly. I have retained his own spelling and grammar without the pedantry of recording occasional slips of the pen. Any added word is placed in square brackets; round brackets are

[page] 3 PREFACE

Darwin's own. Eight of the letters were published in Francis Darwin's Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, though not in their entirety, with portions of a few others; the remainder have not previously been published.

The presentation of the little pocket-books was a more difficult matter. There are consecutive pages of geological notes that I have omitted altogether. The entries are cramped and awkward in style, often showing the press of time and space. They were his shorthand notes to help his memory when he came to write up his journal in the more leisurely moments at sea or on shore. Therefore the day by day narrative is much fuller in his published Diary, and the more scientific discussions, which are hardly even suggested in these rough-drafts, are found in their amplified and completed forms in the later editions of the Voyage of the Beagle.1 Nevertheless much can be gleaned from these spontaneous first impressions that is worth while. His method of working and difficulty of expression are revealed, with a new assurance asserting itself towards the end of the five years. The growing grasp of his subject and his growing self-confidence brought about a remarkable change in his whole personality. Perhaps the long absence from his father's redoubtable presence with his frequent sense of blame, together with the prolonged concentration on the work he loved, helped his energies to converge in one great and fixed purpose. A change in his whole outlook was at work, and the little notebooks and the letters help to bring that conversion—for it was no less—into proper perspective in the whole history of his developing thought.

The interest of the detailed observations and of the embryonic theories of the Beagle note-books lies in their relation to the mature philosophy of the older man. Here we can trace the inception of his evolutionary views to an earlier date than has sometimes been supposed. The study of the two parallel manuscripts has yielded further light on Charles Darwin as he then was, emotionally sensitive and intellectually malleable. Some readers may think of him as always full of years and learning, grave and with flowing beard as he is represented in the best known pictures. Others may have followed him from

1 For the different forms of the Diary and the Journal see Bibliography, pp. 4 and 5.

[page] 4 DARWIN

the ardent but diffident young collector, to an old age of continuing work and established fame. Even those who know him well already, will I hope be further enriched in their love and understanding by the sincerity and deep worship of nature found in the pages of the note-books, and by the open gaiety and affection of his letters.

I am indebted to the generosity of the British Association for the loan of both series of manuscripts. As is well known, this Association now holds Down House, Darwin's old home, as a national memorial under the gift of the late Sir Buckston Browne; to the Darwin relics already under their care, were added many more important manuscripts in 1942. The Beagle letters and note-books formed part of this addition. A grant from the Pilgrim Trust enabled the owners to ensure their permanent preservation in the hands of the British Association, whose kindness in allowing me to keep them for some considerable time I should like here to place on record.

In the text I shall have occasion to refer to the versions and editions of the Beagle Diary. I will here give a short summary in order of their publication, so that the reader may know to which I am referring. This brief bibliography will also include the publications on the Geology and Zoology of the voyage. To Francis Darwin's Life and Letters of Charles Darwin (three volumes), and to Mrs. Litchfield's Emma Darwin (two volumes), and the facts and memories in these works I am more deeply indebted than I can say.

JOURNAL AND DIARY OF THE VOYAGE

1839. First edition, first issue. Darwin's Journal forms the third volume of the official publication edited by Captain FitzRoy and published by Henry Colburn, under the general title Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle. Volumes I and II were by Captain King and Captain FitzRoy.

1839. First edition, second issue. The demand for Darwin's volume immediately called for a second issue, with only minor alterations in the title. Here the well-known title Journal of

[page] 5 PREFACE

Researches was first used, with Geology taking precedence over Natural History, an order subsequently and significantly reversed.

1840. First edition, third issue.

1845. Second edition, published by John Murray as Vol. XII of his Home and Colonial Library. This is the text of the well-known work, the title of which runs: Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Captain FitzRoy, R.N. Much was added in this edition, and as the whole had to be shorter, much had to be cut or condensed. This alteration he found particularly difficult, working at it for four months, and then "rested idle for a fortnight". Further editions with the same text were issued by Murray in 1860 and in 1870.

All to be referred to as The Journal.

1933. Charles Darwin's Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, edited from the MS. by Nora Barlow. Published by the Cambridge University Press, who have kindly given permission for the extracts quoted later. The Diary is the exact transcript of the record he kept on the voyage, amplified from the note-books of the present volume, and not prepared for publication.

This will be referred to as the Diary, 1933, to distinguish it from the Journal, 1839 (first edition), and the Journal, 1845 (second edition and final version).

THE ZOOLOGY OF THE VOYAGE

1839–1843. Five quarto volumes were published with the help of a Government grant of £1,000. Darwin superintended the whole and wrote Introductions and notes, whilst specialists in Fossil Mammalia, Recent Mammalia, Birds, Fish and Reptiles wrote the letterpress.

THE GEOLOGY OF THE VOYAGE.

1843. Part I. The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs.

[page] 6 DARWIN

1844. Part II. Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle.

1846. Part III. Geological Observations on South America. Second editions of all three volumes followed, Parts II and III being incorporated in one volume in 1876. John Murray.

BIOGRAPHICAL

Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, edited by his son, Francis Darwin. In three volumes. Published by John Murray, 1887.

More Letters of Charles Darwin, edited by Francis Darwin and A. C. Seward. In two volumes. Published by John Murray, 1903.

Emma Darwin, A Century of Family Letters, edited by her daughter, Henrietta Litchfield. In two volumes. John Murray, 1915.

[page 7]

PART ONE

Chapter I

THE ENGLISH SCENE

BEFORE we embark with Darwin on his journey round the world in the year 1831, it will be as well to see him in his English setting; to know how he was equipped for his great adventure; and to picture the family circle which he was leaving behind with such bitter pangs of regret that he nearly gave up the cherished prospect of the voyage.

The letters cannot be read aright without some understanding of Charles's home at The Mount, Shrewsbury, where his father lived and practised as a prosperous family doctor, with the three sisters to whom the letters are mainly addressed. Dr. Robert Darwin, a busy, well-known, corpulent figure in Shrewsbury, loved by his rich and poor patients alike, was one of a well-read circle of friends with strong Whig leanings, and Charles was accustomed to the varied discussions at home, where Dr. Robert was apt to hold the field on every kind of subject. At Maer, the home of his Wedgwood cousins only twenty miles' ride away, the talk was more lively and the atmosphere altogether freer. In the back of his mind, never effaced by the sights and sounds of the far-off tropical scene, these two pictures were engraved on his memory; of The Mount with its beloved occupants and their familiar daily doings; and of Maer in its lovely setting of wood and mere, with the parties and the gay cousins, the youngest of whom was destined to become his wife. He could hear the robin sing and see the leaves fall as October overtook him in some remote land; the acacia and the copper beech at home grew to superb trees in his mind—for he remembered every tree, even the least, and he will never forgive his sisters if they cut many down in his absence. English scenery gained in grace the longer he was absent, until all his allegiance contracted to insular dimensions. "What reasonable person can wish for great ill-proportioned

[page] 8 DARWIN

mountains, two or three miles high? No, no; give me the Brythen or some such compact little hill.—And then as to your plains and impenetrable forests, who would compare them with the green fields and oak woods of England?—People are pleased to talk of the ever smiling sky of the tropics: must not this be precious nonsense? Who admires a lady's face who is always smiling? England is not one of your insipid beauties; she can cry, and frown, and smile, all by turns. In short I am convinced it is a most ridiculous thing to go round the world, when by staying quietly, the world will go round with you."

The Brythen for height, and the Severn as a gauge for river width, went with him round the world as his standards of measurement. He always compared a newly seen river in South America with the Severn at Shrewsbury; as so many times the Severn. For The Mount was well-placed above the town, with wide views over the curving river, and the encroaching buildings hardly visible; Robert had chosen the site and had built the solid comfortable red brick residence soon after he had married Susannah Wedgwood in 1796. There Dr. Robert lived for the rest of his life, and there Charles was born in 1809 and grew to manhood, familiar with the lawns and big trees and the terrace overlooking the meadows below, the orchard and newly planned greenhouse, and the flower garden where his sisters worked. During the winter months, when Charles was enduring the summer in the Antipodes, he would imagine the fire-side group at home, with Susan playing the piano; or Nancy the old nurse making vain efforts to rouse them all on a cold frosty morning.

I always see Charles as the eager warm centre of life at The Mount, bringing a more easy informality into that formidable atmosphere. For formidable it undoubtedly was. Dr. Robert Darwin, although possessed of a genuine sympathy and insight which won him the confidence of numerous patients, was also a very considerable tyrant. His was a compelling presence, and all sense of liberty vanished when he entered a room, for no one could feel at ease to "go on about their own talk". A busy and successful doctor, he yet had time for a two-hour monologue each day before dinner. Visitors to The Mount were full of praise of the order, correctness and comfort, but a week was

[page] 9 THE ENGLISH SCENE

long enough; the doctor's talk was fatiguing; a summer visit was better when there was more sitting out in the garden with the girls. Jessie Sismondi, aunt of the young Wedgwood cousins, wrote after a visit to The Mount that she was "in soggezione" to all the Darwins—even dear Susan whom she loved, imposed on her. Subjection to the benevolent tyrant was implicit in the family atmosphere, combined with a real reverence for his opinions and deep mutual affection; for I believe the old doctor had the insight and wisdom not to interfere with the private sense of independence of his children. A certain submissiveness in Charles' relation to his father may today seem unnatural, when adolescent revolt is the order of the day, but this aversion to running counter to authority is a persistent trait in his character throughout his life. He preferred law and the existing order as long as his intellectual integrity was not outraged, and I see no signs of repression in his compliance to his father's dictates, nor of rebellion against his outbursts of disapproval.

In Charles' eyes his chief characteristics were his great powers of observation and of sympathy; not only a sympathy with suffering and with his patients' personal difficulties, which made him a sort of Father Confessor to many of them, but also a generous understanding and desire to promote the happiness of those around him. He evidently had an uncanny perception of people's true motives, and many stories were current showing his powers of reading thoughts, which perhaps really meant that he had a remarkable power of reading character. Curiously cautious in money affairs, he was also freely generous. In Charles' letters home there is the often repeated refrain that he hopes his expenditure is not causing his father much anxiety. Certainly in these references to money, there are memories of the blame and sense of disapproval, but also a faith in his father's understanding and ultimate indulgence.1

Charles' mother died when the boy was only eight years old, leaving his upbringing in the hands of his elder sisters.

1 G. West, in his Charles Darwin, makes more of a case for Charles's fear of Robert; whilst Dr. Douglas Hubble (The Lancet, Jan. 30th, 1943) considers it an important factor in the neurosis to which he attributes Charles' 40 years of ill-health.

B

[page] 10 DARWIN

His mother had been devoted to the garden and the flowers, and Robert and she had lived a united happy life at The Mount, until ill-health intervened. To Charles her memory was dim—her curiously constructed work-table, her black velvet gown and her death-bed. He says in an unpublished sentence of his Autobiography: "I believe that my forgetfulness is partly due to my sisters, owing to their great grief, never being able to speak about her or mention her name and partly to her previous invalid state."

There were four daughters of the marriage; Marianne, the eldest, married Henry Parker in 1824 before this scene opens, and the slight mention of her suggests a much lesser affection for her than for the others. When Marianne and Caroline, the second daughter, were five years and three years old, they went with their mother on a visit to Maer, where they made a bad impression on their uncle and aunt. Mrs. Wedgwood's sister wrote: "I like her (Mrs. Darwin) exceedingly, but not her children who are more rude and disagreeable than any I ever knew, and yet they are better here than they were at Shrewsbury." But Mrs. Wedgwood learnt to love Caroline above all the others as she grew up, and the great wish of her heart came true when she married her own son Josiah in later life.

Caroline, to whom twelve of the present letters are written, had managed the house at Shrewsbury with Marianne since the age of seventeen when her mother died. She was tall, vivacious yet gentle, very popular, and was described as looking like a duchess. She must have carried some of the Shrewsbury stiffness with her, for when she was visiting Maer, Emma, the youngest cousin, wrote how nice Caroline was, and settled herself more at home than usual, as though she was accustomed to bring some formality with her, even to that most informal of houses. At this time she worked with gentle perseverance at an infant Sunday school for children under four in Frankland, the poor part of Shrewsbury above which The Mount stood high and prosperous; later her idealism languished and she wearied of children in general. She undertook the education of Charles before he went to school, but he doubted later on whether this plan had answered. He said: "Caroline was extremely kind, clever and zealous; but she was too zealous in

[page] 11 THE ENGLISH SCENE

trying to improve me; for I clearly remember after this long interval of years, saying to myself when about to enter a room where she was: 'what will she blame me for now?' and I made myself dogged so as not to mind what she might say." Nevertheless they remained great friends, with any early bitterness quite forgotten, and we know that she could write a "very entertaining letter" to her brother.

Susan, the third daughter, was her father's favourite. She, too, was tall, and more beautiful than Caroline, with a beauty that endured, an immense flow of high spirits, and a power of enjoying the little details of life. She and a cousin were nick-named Kitty and Lydia Bennett from their flirtations; she could infect her father with her own rollicking enjoyment, and loud peals of laughter would follow accounts of her balls—a story of a broken carriage pole, a tipsy coachful, and Susan travelling home on the floor. But the stiffness and love of order was there too. Later when she visited Charles and Emma and their growing family at Down, she was uneasy at the children's litter, and tidied away the untidiness as it arose. Emma allowed it to accumulate until it got unbearable, and then called in help. As with the doctor, so with Susan: boys began to be uncongenial animals to her in middle age. She seemed, too, to possess a flair for discovering "disagreables". When Charles later visited The Mount with his nineteen-month baby, accompanied only by the nurse-maid, Susan found fault with the arrangements; Daddy had no glass of water by his bedside; he risked his health by starting for a drive with soaked feet, though Dr. Robert approved of wetting the feet on the grass if shoes were changed. But the worst storm was over Mary the nurse-maid who wore no cap. It looked so dirty and like a grocer's maid-servant; they felt very strongly about it at The Mount. Poor Charles bore the brunt of their wrath and must have felt again "what will they blame me for now?" It is true he had already been on to Emma about it, but he did not give her away. Certainly the sisters created no easy atmosphere for visiting babies; no lessons had then been learnt from evacuation. But in the days when these letters were being written Susan was light-hearted and gay, and could write about an adventure: "I never enjoyed anything like it

[page] 12 DARWIN

—so gay—we never talked a word of common sense all day."

Eight of the letters are to Catherine, the third sister, one year younger than Charles. She was quick and intelligent as a child, and learnt to read more easily than he did. I think she had a disappointed life, with good intellectual powers and little vitality. She could not enjoy the uproarious friendly parties at the Owens as her sisters did, and after one such occasion, herself rather sadly assessed her enjoyment as "about half as much as Susan's" who was in violent spirits all the time. She evidently had real capacity which never found an outlet. Her father used to talk about her "great soul" yet with all her strong affections and capabilities and high character, "she achieved neither happiness for herself, nor for those with whom she lived (perhaps)".

Though not one of the present letters is to Erasmus, Charles' only brother, he is mentioned always with great affection, and his position in the family group was a most important one. He was five years Charles' senior, dearly loved by all, and Charles seldom mentions him without a "poor dear old Ras". His ample income rendered a profession unnecessary, but whether he would have had a fuller life of achievement without his father's endowment we can never know. Certainly Erasmus was able to indulge in the "patient idleness" described by Carlyle, with whom he was on intimate terms. With no fixed occupation, his life was passed with leisurely interests, much reading and many friends; a daily round of intellectual dignity, ease and aloofness hardly congruous with the more active demands of today. A sensitive sympathy and lightness of touch must have stood out against the robust formality of the family circle to which Charles's thoughts so often turned, and endeared him to the many friends who welcomed him on frequent visits to their houses. Behind a certain languor and sadness his astringent wit lurked ready to break through, and the kindly sympathy in his eyes awakened the best in his friends; there was no spitefulness in the somewhat laconic pungency of his humour. "Where he was, the response came more readily, the flow of thought was quicker." But for Charles there was one great lack, he cared not at all for natural history, though in the sciences of chemistry and electricity he had led the way since

[page] 13 THE ENGLISH SCENE

their days of boyhood. In the letters home all the arrangements about purchases and despatching books to Charles, and the plans for the reception of his specimens in England, were placed in Erasmus' hands. He is only once mentioned in the note-books. When returning by the Cape of Good Hope, Charles met Sir J. Herschel and discussed with him some chemico-physical problem. He still referred to Erasmus in his mind on such topics, and wrote: "Ask Erasmus whether electricity would affect this"; and he must have given an affectionate thought to the lonely figure living in rooms in London, and remembered the days when they worked together at chemistry in their spare time, using the tool-shed at Shrewsbury as their laboratory.

There is an autobiographical fragment, not included in the well-known autobiography, but published in More Letters of Charles Darwin, that gives an added picture of his early years with vivid light on his own and his sisters' characters. Some passages I will give here; he evidently enjoyed introspection, and he treats the retrospect of his childish untruthfulness and what must now be called exhibitionism, with the same aloofness as he would any other collection of scientific facts.

"My earliest recollection . . . which must have been before I was four years old, was when sitting on Caroline's knee in the drawing room, whilst she was cutting an orange for me, a cow ran by the window which made me jump, so that I received a bad cut, of which I bear the scar to this day. . . Of this scene I recollect the place where I sat and the cause of the fright, but not the cut itself, and I think my memory is real . . . because I clearly remember which way the cow ran, which would not probably have been told me."

"1813. When I was four years and a half old, I went to the sea, and stayed there some weeks. I remember many things, but with the exception of the maidservants (and these are not individualised) I recollect none of my family who were there. I remember either myself or Catherine being naughty, and being shut up in a room and trying to break the windows. . . . Some other recollections are those of vanity—namely thinking

[page] 14 DARWIN

that people were admiring me, in one instance for perseverance and another for boldness in climbing a low tree; and what is odder, a consciousness, as if instinctive, that I was vain, and contempt for myself. . . . All my recollections seem to be connected most closely with myself; now Catherine seems to recollect scenes where others were the chief actors. When my mother died I was eight and a half years old, and [Catherine] one year less, yet she remembers all particulars and events of each day, whilst I scarcely recollect anything (and so with very many other cases), except being sent for, the memory of going into her room, my father meeting me, crying afterwards. I recollect my mother's gown and scarcely anything of her appearance . . . I have no distinct remembrance of any conversation . . . Catherine remembers my mother crying when she heard of my grandmother's death . . . Susan like me only remembers affairs personal. It is sufficiently odd this [difference] in subjects remembered. Catherine says she does not remember the impression made upon her by external things, as scenery, but for things which she reads she has an excellent memory, i.e., for ideas. Now her sympathy being ideal, it is part of her character, and shows how easily her kind of memory was stamped; a vivid thought is repeated, a vivid impression forgotten."

"1817. At eight and a half years I went to Mr. Case's school. I remember how very much I was afraid of meeting the dogs in Barker Street, and how at school I could not get up my courage to fight. I was very timid by nature. I remember I took great delight at school in fishing for newts in the quarry pool. I had thus young formed a strong taste for collecting, chiefly seals, franks, etc., but also pebbles and minerals. . . . I believe shortly after this or before, I had smattered in botany, and certainly when at Mr. Case's school I was very fond of gardening, and invented some great falsehoods about being able to colour crocuses as I liked. . . . It was soon after I began collecting stones, i.e., when nine or ten, that I distinctly recollect the desire I had of being able to know something about every pebble in front of the hall door: it was my earliest and only geological aspiration at that time.

[page] 15 THE ENGLISH SCENE

"I was in those days a very great story-teller—for the pleasure of exciting attention and surprise. I stole fruit and hid it for these same motives, and injured trees by barking them for similar ends. I scarcely ever went out walking without saying I had seen a pheasant or some strange bird (natural history taste); these lies, when not detected, I presume excited my attention, as I recollect them vividly, not connected with shame, though some I do, but as something which by having produced a great effect on my mind, gave pleasure like a tragedy. I recollect when at Mr. Case's inventing a whole fabric to show how fond I was of speaking the truth! . . ."

"1819. July (ten and a half years). Went to the sea at Plas Edwards. I remember a certain shady green road (where I saw a snake) and a waterfall, with a degree of pleasure, which must be connected with the pleasure from scenery, though not directly recognised as such. The sandy plain before the house has left a strong impression, which is obscurely connected with an indistinct remembrance of curious insects, probably a Cimex mottled with red, and Zygœna, the burnet moth.1 I was at that time very .passionate (when I swore like a trooper) and quarrelsome. The former passion has, I think, nearly wholly but slowly died away. . . The memory now flashes across me of the pleasure I had in the evening on a blowy day walking along the beach by myself and seeing the gulls and cormorants wending their way home in a wild and irregular course. Such poetic pleasures, felt so keenly in after years, I should not have expected so early in life."

To fill in the picture of Charles and his sisters in those early days I often wish that we had their side of the correspondence, or that we might join them under the trees in the garden at The Mount and hear them discussing the absent Charles and the latest letter received. Emma Wedgwood might well have been sitting under the trees with the young Darwins on one of the frequently interchanged visits, and the slow-travelling

1 He almost decided to collect all dead insects he could find, for his sisters impressed on him that it would be wrong to kill them.

[page] 16 DARWIN

letters, often crossed with a different coloured ink, and difficult to decipher, must have been pored over long and affectionately. Or perhaps the last batch of the Journal was being discussed at Maer, for the sisters were to send it on there if they did not think it too childish; he wanted their opinion.

The household at Maer, with the Wedgwood cousins and his silent and reserved uncle and boundlessly hospitable aunt, must have crowded into his mind on the far off tropic nights as often as he thought of England and home. Life at Maer seems to have made a deep impression of happiness on a wide circle of cousins and friends; and was it not the home of Emma, Charles' future wife? There was a sense of freedom absent from The Mount; endless good talk, plenty of books, a pleasant house built of stone, and a garden with enchanted memories of sitting out on summer nights, long conversations, singing, laughter, and listening to the waterfowl on the mere at the bottom of the slope. Charles' mother, of whom he remembered so little, was Josiah's sister, and both were the children of the more famous Josiah, the Potter and founder of the Wedgwood Potteries at Etruria. Josiah of Maer, and Bessy his wife, had nine children, of whom eight lived to grow up. Emma, whom Charles married in 1840, was the youngest, and one year his senior. The geniality of the family was not of Josiah's making; Sydney Smith said of him: "Wedgwood is an excellent man; it is a pity he hates his friends." He had great good sense and judgment, and had a special liking for his nephew and a belief in him, talking more openly with him than he did with others; indeed his intervention weighted the balance in favour of Charles' acceptance of the proposal to join the Beagle. The opening of the shooting season always found Charles ready at Maer; it was in the autumn of 1831, just after he had refused the first tentative suggestion from Professor Henslow that he should go as naturalist on the Beagle, that he hastened to Maer on September 1st, and his uncle put a very different light on the matter, as will be told later.

A few years after his return home Charles and Emma became engaged to be married, and some passages in her letters show him to us through her eyes as he then was, with the experience of the voyage behind him, but before his light-

[page] 17 EDUCATION

hearted buoyancy of spirits was burdened by perpetual ill-health.

She wrote: "He is the most open transparent man I ever saw, and every word expresses his real thoughts. . . . He is particularly affectionate, and very nice to his father and sisters, and perfectly sweet-tempered, and possesses some minor qualities that add particularly to one's happiness, such as not being fastidious, and being humane to animals." He was fond of talking, and scarcely ever out of spirits; even when he was unwell, he continued sociable, and was "not like the rest of the Darwins, who will not say how they really are". She did not think it so important a thing as did Aunt Sarah that he drank no wine, but nevertheless "a pleasant thing." Alas! he is no play-goer, but "he stands concerts very well", she writes; indeed after a long fast he could become "ravenous for the pianoforte". Perhaps his genuine love of music was already on the wane in the busy London period, when Emma wrote; certainly during the voyage his love of music was deep and genuine. As to the sister arts, it is on record that a small volume of Milton was his constant pocket companion on his inland expeditions; though as for painters, he had little opinion of "birds of that feather"; and he was alarmed at his own extravagance when he spent six guineas on two landscapes by the artist accompanying the Beagle.

Chapter 2

EDUCATION

IN THE summer of 1831 Charles was still leading an easy-going desultory existence before entering the Church when he received the offer to join the Beagle as naturalist. He had finished with Cambridge; medicine as a profession he had already rejected, to Dr. Darwin's sorrow, for he longed to see his son settling to a steady gentlemanly life. Indeed he could not look favourably on the wild suggestion of the voyage, and only gave reluctant consent when persuaded that natural history was very suitable to a clergyman. Neither he nor

[page] 18 DARWIN

Charles guessed that the new venture would lead him along very different paths, and for years the tacit assumption persisted that the voyage was only a prelude to taking orders. I think in the end Dr. Robert must have been sufficiently wise to recognise the new steadiness of purpose that grew from the stern discipline of the voyage as it could hardly have grown in any other way.

Since the days when the boy of nine aspired to a knowledge of all the different pebbles on his father's drive, until the young man of twenty-two was asked to fill the post of naturalist on board the Beagle, how had his education helped him for such an undertaking, when science was little thought of as a career; and who had the acumen to pick him out as the right man?

The story of his education shall here be told briefly; the seven years at Dr. Butler's school in Shrewsbury where he boarded, he himself condemned utterly. "Nothing could have been worse for the development of my mind than Dr. Butler's school, as it was strictly classical, nothing else being taught except a little ancient geography and history. The school as a means of education to me was simply a blank." Possibly his memories have painted too harsh a picture; it may be that his admitted admiration for the Odes of Horace, together with a great fondness for all kinds of reading—including the historical plays of Shakespeare, which he used to take to an old window in the thick walls of the school—were at any rate encouraged by Dr. Butler's methods, even if at the expense of any other mental training. Amongst the pile of natural history books he took with him on the Beagle he made room for his Greek Testament; perhaps his plan to fit in "a little Classics, not more" than on Sundays, was a concession to Dr. Butler's memory even if the intention was not always carried out.

One hundred and twenty years ago no schools catered for the scientific mind; education meant a classical education, and boys with no aptitude for languages but with a craving for other kinds of knowledge had to find means of their own to gain their ends, which if carried to a conclusion can be a very valuable self-training indeed. Charles and his brother Erasmus, five years his senior, made a fair laboratory

[page] 19 EDUCATION

out of their father's tool-house in the garden, where many chemical experiments were performed by the two boys—Charles acting as Erasmus' servant. Erasmus at this time must have had a keen interest in the sciences other than natural history, and Charles as a schoolboy followed him with enthusiasm; the school got wind of their exploits, and Charles was nicknamed Gas, whilst Dr. Butler publicly rebuked him for wasting his time over such useless subjects.

When he was sixteen and a half, his father took him from Shrewsbury and sent him to Edinburgh University to join Erasmus, who was already finishing his medical training, though not intending to practice. Here he found much to stimulate him, especially in the company of other students and older men with strong tastes in natural history. He collected marine animals in the tidal pools and made friends with the fishermen, and sometimes accompanied them on their trawling expeditions. He even did some clinical work in the wards, but his soft heart could not bear the operating theatre and the gruesome sights before the days of chloroform. He inveighed bitterly against the dullness of the invariable lecture as the only means of instruction, and wrote home to Caroline: "Dr. Duncan is so very learned that his wisdom has left no room for his sense, and he lectures, as I have already said, on the Materia Medica, which cannot be translated into any words expressive enough of its stupidity. . . . At twelve the Hospital, after which I attend Monro on Anatomy. I dislike him and his lectures so much that I cannot speak with decency about them."

In later life he deplored the absence of any training in dissection: "this has been an irremediable evil, as well as my incapacity to draw." Nevertheless at Edinburgh he found others ruled by the same enthusiasms that more and more possessed him; he could discuss the problems that haunted him, though when on a walk his companion burst forth into pæans of praise of the Lamarckian doctrines of evolution, Charles could only listen with silent astonishment. Nor would he in later life acknowledge any great effect on his own views on evolution from familiarity with his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin's, works, where again evolutionary views are foreshadowed, there being too little support of factual evidence in either for Charles'

[page] 20 DARWIN

liking. He himself was to search the earth for twenty-five years for facts bearing on evolution before he was ready to put forward his own theory: facts from seedsmen, facts from animal fanciers, facts from farmers, besides his own observations and those derived from other scientists.

Nevertheless this exchange of views with other keen minds must have meant much in the Edinburgh days; so did the meetings of the scientific societies which he joined, where he even read a paper before the Plinian Society on minor discoveries concerning the microscopic marine animals which he had collected whilst trawling with the fishermen. At another society's meetings he heard some interesting lectures on American birds by Audubon, whose enthusiastic sympathy for the living animal both in his writing and in his paintings, must have been congenial to Charles. But in these discourses Audubon sneered somewhat unjustly at Waterton, for whom Charles had a great admiration; Charles felt alienated, and they met no more. He had a curious slight contact with Waterton during the Edinburgh period; he had become acquainted with a negro who had travelled with him, and who earned his living in Edinburgh by stuffing birds. Charles used often to sit with him, and found him pleasant and intelligent, besides a good instructor in the art of stuffing animals. Sitting with the negro listening to travellers' tales must have led to many wild castles in the air about the far-off lands he already craved to visit.

He went to Edinburgh at the age of sixteen, eager for knowledge, and found much that was good; perhaps more from the uses he made of his opportunities than from the university curriculum. He made friends with the fishermen and went trawling with them, and sat stuffing birds and talking to his friend the negro traveller; whilst he could not speak "with decency" of the lectures and the lecturers, they were so nauseatingly dull. Indeed he was almost disgusted with the science of geology for good by the incredible dullness of Professor Jameson's lectures. Yet geology was to become his first love amongst the sciences, and he went to Edinburgh prepared and asking for a philosophical treatment of the subject. An old man in Shrewsbury had made a great impression on his mind when quite a boy, by discussing with him a large erratic

[page] 21 EDUCATION

boulder that still stands in the town, called the Bell-stone, and the old man solemnly assured the boy that the world would come to an end before anyone would explain how the stone came to lie where it did, the nearest rocks of the kind being found no nearer than Cumberland or Scotland. Charles often thought of the wonderful stone, so that when he first read of the action of icebergs in transporting boulders over long distances, he rejoiced in this rational explanation of the mystery. Yet all his eager hopes were turned to dislike and despair when he listened to the geological Dryasdust in Professor Jameson, and he determined never to study the distasteful subject.

Dr. Robert began to despair of his son, when after two years at Edinburgh he was no nearer to becoming the successful young physician. So he suggested that he should go to Cambridge and take orders. "During the three years which I spent at Cambridge my time was wasted, as far as the academical studies were concerned, as completely as at Edinburgh and at school." But there again he met those who were to be his friends for his life-time, and found much that was stimulating and delightful outside the university curriculum. He had been too much sickened by lectures in Edinburgh to attempt Professor Sedgwick's geology course at Cambridge, though he got to know him, and went on a geological tour with him in North Wales, which proved later a very valuable help in meeting the challenge of the new geological problems of the voyage. Beetle collecting became a ruling passion, and to the end of his life he remembered the exact look of tree, post or bank, where certain rare captures were made in the Cambridge fens. One day behind some old bark on a tree-trunk, two rare beetles were seized, one with either hand; then a third appeared, and to release his right hand he popped one in his mouth; unfortunately it proceeded to eject a very acrid fluid so that he had to spit it out, and lost both it and the third specimen. He tells the story in his Autobiography, and one feels that the loss of the beetles was still at the age of sixty-seven slightly rankling in his mind. But this was not scientific collecting; he never dissected, and hardly even compared, but it probably gave him a useful insight into the varieties and specific differences of one section of insect life. Nor did he study botany, although Pro-

[page] 22 DARWIN

fessor Henslow's lectures which he attended might well have put him on the path.

It was not in the rôle of lecturer that Henslow exerted a far-reaching influence on the young Darwin, but as a much-loved and much-revered friend. Henslow had a wide knowledge in many branches of science, and kept open house once a week for young and old, where Darwin soon found himself at home. There must have been a strong affinity between the two, and in the last year at Cambridge Henslow used often to ask him back to the family dinner, and together they went for long almost daily walks. Darwin wrote of him: "His strongest taste was to draw conclusions from long-continued minute observations." All the warmth of Charles' allegiance went out to the older man with a deep personal affection. His open-hearted enthusiasms sometimes waned as the years brought a clearer understanding of character; but not so in the case of Henslow. To the end of his days he retained the deepest gratitude and admiration for this good man, and the highest respect for his moral qualities.

Chapter 3

THE OFFER

IT is not too much to say that meeting Henslow at Cambridge and becoming his intimate friend did in fact change the whole course of Darwin's career, for without Henslow the offer of the Beagle post would not have reached him. Henslow must have reciprocated the warm feelings of the younger man, and judged correctly those dormant possibilities in the ardent beetle-collector, or he would never have acted as intermediary and suggested Darwin's name when approached to furnish a suitable naturalist for the Beagle voyage. Henslow had at first thought of accepting the post himself, but his wife's distress caused him to give it up, so he placed the golden opportunity in the hands of his favourite pupil, and wrote: " . . . I have stated that I consider you to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation. I state this not in the

[page] 23 THE OFFER

supposition of your being a finished naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, and noting, anything worthy to be noted in Natural History. . . . Captain FitzRoy wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector, and would not take anyone, however good a naturalist, who was not recommended to him likewise as a gentleman. . . . Don't put any modest doubts or fears about your disqualifications, for I assure you I think you are the very man they are in search of; so conceive yourself to be tapped on the shoulder by your bum-bailiff and affectionate friend, J. S. Henslow." Thus came the critical offer in the end of August, 1831, a few months after he had taken his degree at Cambridge: "a good place amongst the  or crowd of men who do not go in for honours." Hardly any academical training lay behind him; geology in the lecture-rooms of Edinburgh had filled him with disgust for the subject; botany he had only touched on in Henslow's lectures; dissection he had done none at all. The study of Paley's Evidences had delighted him in the clarity of the logic: the premises he took for granted at that time. Yet with so little to show, Henslow pressed him to accept the offer, and other older men must also have perceived in him something exceptional. Luckily for the geological work of the voyage, which was to put him to the test so soon, Henslow had persuaded him to take up the study of the subject after taking his degree, so that in the summer of 1831 he was "working like a tiger" at a geological map of Shropshire, before joining Sedgwick on a geological tour of North Wales. The value of this belated self-training cannot be over-estimated in what was so soon to follow. Indeed it was of the same order as the self-discipline of the voyage itself, when concentration on the work in hand superseded all else. His mind had never run easily in academical grooves, and though he took no pleasure in going counter to existing convictions, he possessed something of the rebel mentality, which then even less than now could find full scope in the prescribed curriculum. His love of theorising and of observing, which had found such sympathetic appreciation in Henslow, could at last have full sway. He wrote to his old master from Shropshire, during these weeks before leaving for North Wales: "I suspect that the first expedi-

or crowd of men who do not go in for honours." Hardly any academical training lay behind him; geology in the lecture-rooms of Edinburgh had filled him with disgust for the subject; botany he had only touched on in Henslow's lectures; dissection he had done none at all. The study of Paley's Evidences had delighted him in the clarity of the logic: the premises he took for granted at that time. Yet with so little to show, Henslow pressed him to accept the offer, and other older men must also have perceived in him something exceptional. Luckily for the geological work of the voyage, which was to put him to the test so soon, Henslow had persuaded him to take up the study of the subject after taking his degree, so that in the summer of 1831 he was "working like a tiger" at a geological map of Shropshire, before joining Sedgwick on a geological tour of North Wales. The value of this belated self-training cannot be over-estimated in what was so soon to follow. Indeed it was of the same order as the self-discipline of the voyage itself, when concentration on the work in hand superseded all else. His mind had never run easily in academical grooves, and though he took no pleasure in going counter to existing convictions, he possessed something of the rebel mentality, which then even less than now could find full scope in the prescribed curriculum. His love of theorising and of observing, which had found such sympathetic appreciation in Henslow, could at last have full sway. He wrote to his old master from Shropshire, during these weeks before leaving for North Wales: "I suspect that the first expedi-

[page] 24 DARWIN

tion I take, clinometer and hammer in hand, will send me back very little wiser and a good deal more puzzled than when I started. As yet I have only indulged in hypotheses, but they are such powerful ones that I suppose, if they were put ínto action for but one day, the world would come to an end."

The story of how Charles Darwin came to be entered on the books of H.M.S. Beagle as naturalist on the long voyage of circumnavigation has often been told. Captain Beaufort, Hydrographer, Captain FitzRoy, Prof. Henslow of Cambridge, Dr. Robert Darwin, his uncle Josiah Wedgwood, all had their share, pulling this way and that, until Robert's unwilling permission was gained by Josiah's cogent reasoning.

Charles has described those crucial days in a preface to the Diary of the Beagle, and in his autobiography; how he received the letter already quoted from Henslow on his return home from Wales, whence he had hastened so as to be ready for the shooting at Maer on September 1st. "For at that time I should have thought myself mad to give up the first days of partridge-shooting for geology or any other science."

"I had been wandering about North Wales on a geological tour with Professor Sedgwick when I arrived home on Monday 29th of August. My sisters first informed me of the letters from Prof. Henslow & Mr. Peacock offering to me the place in the Beagle which I now fill.—I immediately said I would go; but the next morning finding my Father so much averse to the whole plan, I wrote to Mr. Peacock to refuse his offer. On the last day of August I went to Maer, where everything soon bore a different appearance. I found every member of the family so strongly on my side, that I determined to make another effort. In the evening I drew up a list of my Father's objections, to which Uncle Jos wrote his opinion & answer. This we sent off to Shrewsbury early the next morning & I went out shooting. About 10 o'clock Uncle Jos sent me a message to say he intended going to Shrewsbury & offering to take me with him. When we arrived there, all things were settled, & my Father most kindly gave his consent."

Here are the letters which must have reached Shrewsbury on the morning of August 30th, giving Dr. Robert considerable matter for thought. Firstly, Charles' to his Father; followed

[page] 25 THE OFFER

by the list of Dr. Robert's objections, which Charles had drawn up for Josiah's consideration; and finally Josiah's own views.

[MAER]

August 31st [1831]

My dear Father,

I am afraid I am going to make you again very uncomfortable—but upon consideration I think you will excuse me once again stating my opinions on the offer of the voyage.—My excuse and reason is, [is] the different way all the Wedgwoods view the subject from what you and my sisters do.—

I have given Uncle Jos, what I fervently trust is an accurate and full list of your objections, and he is kind enough to give his opinion on all. The list and his answers will be enclosed, but may I beg of you one favour, it will be doing me the greatest kindness if you will send me a decided answer—Yes or No—; if the latter I should be most ungrateful if I did not implicitly yield to your better judgement and to the kindest indulgence which you have shown me all through my life,—and you may rely upon it I will never mention the subject again; if your answer should be Yes, I will go directly to Henslow and consult deliberately with him and then come to Shrewsbury. The danger appears to me and all the Wedgwoods not great—the expence cannot be serious, and the time I do not think anyhow, would be more thrown away than if I staid at home.—But pray do not consider that I am so bent on going, that I would for one single moment hesitate if you thought that after a short period you should continue uncomfortable.—I must again state I cannot think it would unfit me hereafter for a steady life.—I do hope this letter will not give you much uneasiness.—I send it by the car tomorrow morning; if you make up your mind directly will you send me an answer on the following day by the same means. If this letter should not find you at home, I hope you will answer as soon as you conveniently can.—

I do not know what to say about Uncle Jos' kindness, I never can forget how he interests himself about me.

Believe me, my dear Father,

Your affectionate son,

Charles Darwin.

c

[page] 26 DARWIN

P.S. Frank would be much obliged if you would forward the Crockery to the Hill.

"1. Disreputable to my character as a Clergyman hereafter.

2. A wild scheme.

3. That they must have offered to many others before me the place of Naturalist.

4. And from its not being accepted there must be some serious objection to the vessel or expedition.

5. That I should never settle down to a steady life hereafter.

6. That my accommodations would be most uncomfortable.

7. That you, that is, Dr. Darwin, should consider it as again changing my profession.

8. That it would be a useless undertaking."

Finally also enclosed, was Josiah Wedgwood's letter to Dr. Darwin, with "Read this last" in Charles's hand-writing.

MAER,

August 31, 1831.

My dear Doctor,

I feel the responsibility of your application to me on the offer that has been made to Charles . . . . . . Charles has put down what he conceives to be your principal objections, and I think the best course I can take will he to state what Occurs to me upon each of them.

1. I should not think that it would be in any degree disreputable to his character as a Clergyman. I should on the contrary think the offer honourable to him; and the pursuit of Natural History, though certainly not professional, is very suitable to a clergyman.

2. I hardly know how to meet this objection, but he would have definite objects upon which to employ himself, and might acquire and strengthen habits of application, and I should think would be as likely to do so as in any way in which he is likely to pass the next two years at home.

3. The notion did not occur to me in reading the letters; and on reading them again with that object in my mind I see no ground for it.

[page] 27 THE OFFER

4. I cannot conceive that the Admiralty would send out a bad vessel on such a service. As to objections to the expedition, they will differ in each man's case, and nothing would, I think, be inferred in Charles's case, if it were known that others had objected.

5. You are a much better judge of Charles's character than I can be. If on comparing this mode of spending the next two years with the way in which he will probably spend them if he does not accept this offer, you think him less likely to be rendered unsteady and unable to settle, it is undoubtedly a weighty objection. Is it not the case that sailors are prone to settle in domestic and quiet habits?

6. I can form no opinion on this further than that if appointed by the Admiralty he will have a claim to be as well accommodated as the vessel will allow.

7. If I saw Charles now absorbed in professional studies I should probably think it would not be advisable to interrupt them; but this is not, and I think, will not be the case with him. His present pursuit of knowledge is in the same track as he would have to follow in the expedition.

8. The undertaking would be useless as regards his profession, but looking upon him as a man of enlarged curiosity, it affords him such an opportunity of seeing men and things as happens to few. You will bear in mind that I have had very little time for consideration, and that you and Charles are the persons who must decide.

I am, My dear Doctor,

Affectionately yours,

Josiah Wedgwood.

The rest of the story after Dr. Robert's final consent shall be told in the words of the Preface to the Diary.

"I shall never forget what very anxious & uncomfortable days these two were, my heart appeared to sink within me, independently of the doubts raised by my Father's dislike to the scheme. I could scarcely make up my mind to leave England even for the time which I then thought the voyage would last. Lucky indeed it was for me that the first picture of the expedition was such an highly coloured one.

[page] 28 DARWIN

"In the evening I wrote to Mr. Peacock & Capt. Beaufort & went to bed very much exhausted. On the 2nd I got up at 3 o'clock & went by the Wonder coach as far as Brickhill; I then proceeded by postchaises to Cambridge. I there staid two days consulting with Prof. Henslow. At this point I had nearly given up all hopes, owing to a letter from Cap. FitzRoy to Mr Wood, which threw on every thing a very discouraging appearance. On Monday 5th I went to London & that same day saw Caps. Beaufort & FitzRoy. The latter soon smoothed away all difficulties, & from that time to the present, has taken the kindest interest in all my affairs. On Sunday 11th sailed by Steamer to Plymouth in order to see the Beagle. I returned to London on 18th. On Monday the 19th by mail to Cambridge, where after taking leave of Henslow on Wednesday night I got to St Albans & so by the Wonder to Shrewsbury on Thursday 22nd. I left home on October 2nd for London, where I remained after many & unexpected delays till the 24th on which day I arrived at Devonport & this journal begins."

So the die was cast, and Dr. Darwin's caution was overruled by Josiah Wedgwood's good judgment and good sense. The expenses would be heavy, but Dr. Darwin would defray them willingly enough when once convinced of the scheme's respectability. The preliminary expenditure was considerable, though Charles could not agree to the Captain's extravagant suggestion of spending £60 on pistols. The letters to his sisters give the details of the turmoil of preparations that ensued; travelling by coach between Shrewsbury and Cambridge, where Henslow had to be consulted on many points; staying in London where final purchases had to be made. He took with him a hand-magnifier, a microscope, equipment for blow-pipe analysis, a contact goniometer (for measuring the angles of crystals), and a magnet, besides a small library of books. All these had to be packed and the inevitable last moment arrangements completed before he made his last farewells and arrived in Plymouth on Monday, October 24th, 1831. His hopes of a speedy departure were dashed, and delays dragged on for two whole months, leaving a memory of misery and anxiety recorded in his Autobiography. "These two months at Plymouth were the most miserable which I ever spent, though I exerted myself in various ways. I was out of spirits at the thought of leaving all

[page] 29 THE OFFER 29

my family and friends for so long a time, and the weather seemed to me inexpressibly gloomy. I was also troubled with palpitations about the heart, and like many a young ignorant man, specially one with a smattering of medical knowledge, was convinced that I had heart-disease. I did not consult any doctor as I fully expected to hear the verdict that I was not fit for the voyage, and I was resolved to go at all hazards."

But there were some compensations in the miserable delay; he learnt to know his companions, and he could arrange and rearrange his equipment in the Poop cabin allotted to him; he could begin to feel "a fine naval fervour", without suffering continual sea-sickness. He occupied himself with helping FitzRoy in his experiments with the dipping needle and in desultory natural history in the neighbourhood, usually accompanied by one of the young officers. The account of the preparations on board give the impression that every inch was used for stowing away all the necessaries. Darwin was tall, a disadvantage when your hammock has to be slung in a limited space, and his only expedient was to remove the top drawer where his clothes were stored before nightfall to gain the extra foot in length for the foot-clews of his hammock.

Captain FitzRoy saw to every detail in the equipment of the expedition himself; he took a great pride in his instruments and had with him twenty-two chronometers. He also took a great pride in the health of his crew, and supplied anti-scorbutics; pickles, dried apples, lemon juice; also between five and six thousand canisters of Kilner and Moorsom's preserved meat, vegetable and soup. The lengthy delay was partly caused by his scrupulous care in refitting the Beagle for the expedition, and from the fact that she was found to be so rotten when recommissioned in 1831 as the result of the long previous voyage, that much of her woodwork had to be rebuilt. But improvements were made, increasing her tonnage from 235 to 242 tons burthen by raising the upper deck, which also made her safer in heavy weather. On the voyage they were to test Harris's new lightning conductors, an innovation consisting of copper plates let into the masts and yards and connecting with the water beneath. She was rigged as a barque, although belonging to the class of ten-gun brigs, nicknamed "coffins" in the navy from their

[page] 30 DARWIN

behaviour in severe gales. But the magnificent seamanship of Captain FitzRoy brought her safely through all the rigours of the storms encountered without carrying away a spar. On November 23rd the ship was moved to Barnet Pool, the carpenters and painters had completed their work, the stores were stowed away, but still the winds remained contrary. Darwin began to understand the operations of a sailing-ship in full working order, and he felt a nautical thrill as he heard the coxwain's piping and the men working at the hawsers to the sound of a fife. Then when the weather cleared, Christmas celebrations intervened and almost the whole crew was disabled through drunkenness; December 26th was a day of anarchy with punishments of flogging and eight or nine hours of heavy chains, so that when they sailed on December 27th Charles was haunted during his first week of sea-sickness and misery by the horror of the scene.

In looking back, Darwin attributed his habits of methodical work to the absolute necessity of tidiness where space was so limited. That he made of the voyage a period of intensive scientific training was a remarkable feat in the young man of twenty-two, with his high spirits and easy outlook on life, all the more so from the knowledge the young Darwins had that they need make no effort to support themselves. Unlike Thomas Henry Huxley,1 the circumstances of whose early career ran along somewhat parallel lines, Darwin seldom reveals any emotional conflict, never any bitterness. Nor did he have to face the financial anxieties which so added to the bitter schooling of Huxley's youth. In Darwin's more equable nature, struggle and conflict seemed to play little part. Whilst Huxley waged a ceaseless war, both within himself and against man and circumstance, his qualities emerging as victories against visible and invisible foes, the young Darwin had little ambition and at the outset hardly more than a craving to collect beetles and examine the world around him with his own eyes instead of through the spectacles of his elders; there was little to mark him out as there was in the young Huxley, either in intellectual ambition or in his emotional receptiveness.

1 T. H. Huxley's Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake. Edited by Julian Huxley, 1935.

[page] 31 THE OFFER

With his high spirits and comfortable optimism it is all the more remarkable that he forced on himself the severe conditioning of the voyage. That very discipline was a sign of what was to come; and the Beagle manuscripts show how the dominating sway and the integrity of his scientific purpose came to possess him more and more. The congenial work acted like a release; here at last was the right channel for his vast latent energies, a final direction and goal for his enthusiasms. His bent towards collecting, when indulged in, had often in the past been more or less of an illicit occupation, and now in his new rôle, it suddenly became his lawful and prescribed duty.

It is the discovery of this scientific purpose that unfolds before us in the letters and note-books; from the first tentative assertion after a few weeks on board, through the intervening years when he begins to hope he will be listened to by real geologists, and sees himself living in lodgings with good big rooms in some vulgar part of London working at his results; until through the fervent study of the infinite host of living beings and the constant building of geological castles in the air, a real conviction asserts itself, a firmer faith in the value and utility of his own efforts.

But it was not only that at last the collector, the observer and the logician in him were satisfied; that now he could shoot, amass specimens and reason on the geological ages without running counter to any other more immediate rule of work; the congenial path along which his new duty lay included a new and profound emotional satisfaction.

He was at last able to begin to set together in a complete scheme his one true worship, that of the works of nature; to weld a whole compounded of his logical thought and his emotions. He was able to give all his powers to what passed in his mind "while travelling across the wild deserts . . . or glorious forests or pacing the deck of the poor little Beagle at night." Again and again in the letters stress is laid on this exalted adoration which was so intimately bound up with his search for a more coherent, unifying explanation for the world-plan as he saw it. Perhaps there is no real antithesis between the intellectual and the emotional approach; but so much has been

[page] 32 DARWIN

said on the subject of the intellectual setting of the voyage for Darwin's mental development, that I believe this other factor should be more noticed. Darwin was at that time destined for the Church; now for the first time he could give full rein to what was his true vocation; and was he not also studying the works of that Creator whom later he believed he would more specifically serve? His father had given his consent, and likewise drafts on his bank; Uncle Jos, that wisest of men, had pleaded for him and had turned the balance; all the cousins had backed him. Nay, his appointment was in the first place due to the fanatically religious Captain FitzRoy, so it was clear that his work must lie along the seeming paths of orthodoxy and the existing order; though during those nightly pacings of the Beagle's decks as the years and months passed by, the existing order must have begun to crumble in his mind.

But the point which these letters and the entries in the pocket-books confirm is that his almost religious fervour for all aspects of nature, from the vast phenomenon of Andean elevation to the detailed structure of coralline rock, received a new sanction on the voyage, which acted as a release to all his powers. He began to grope his way towards a rationalisation of his worship, a unification of the processes he saw at work all round him. Perhaps as the years passed, and his energies, dimmed by ill-health, were more and more concentrated, his search for underlying causes led to a weakening of his appreciation of works of nature, as it certainly did of works of art. In his autobiography he bitterly regrets the atrophy of his powers of appreciation of good pictures, poetry and of music; the plays of Shakespeare had become intolerably dull to him, alas; whilst music set his thoughts working too hard at the problem most on his mind. But his worship of nature never wholly left him; he would seek no altars to worship at other than the garden at Down and the quiet Kentish country, for he could not be persuaded to leave home. But the satisfaction in the daily walk along the Sand-walk, beyond the cultivated garden and overlooking the chalky turf and wooded valley, was the emotional satisfaction of the older man, taking the place of the intensity of delight of the boy who had walked on the beach alone and seen the gulls and cormorants blown about

[page] 33 CAPTAIN ROBERT FITZROY

the sky; replacing, too, those moments of intense æsthetic emotion of the young man on his travels, perhaps seated in a Brazilian forest, perhaps viewing the remote and sublime heights whilst crossing the Andes.

Chapter 4

CAPTAIN ROBERT FITZROY

OF THE influential factors of these years, one has hardly been enough recognised. The dominating personality of Captain Robert FitzRoy, Commander of the expedition, with whom Darwin was necessarily thrown into such extremely close contact, did in fact play a curiously important rôle in the drama of those years.1 From the outset they seemed to be mutually suited to one another; after the first interviews, so decisive in Charles's career, FitzRoy wrote to Captain Beaufort, the Admiralty Hydrographer: "I like what I see of him much, and I now request that you will apply for him to accompany me as Naturalist." The very same evening Darwin wrote home to his sister: "It is no use attempting to praise him as much as I feel inclined to do, for you would not believe me." Soon he refers to him as "my beau ideal of a Captain". After a few weeks at sea FitzRoy wrote again to the Hydrographer: "Darwin is a very sensible hard-working man, and a very pleasant mess-mate. I never saw a 'shore-going fellow' come into the ways of a ship so soon and so thoroughly as Darwin", whilst later he writes to Captain Beaufort, "Darwin is a regular Trump." FitzRoy must have appreciated Charles' simple openness and good temper; he himself was a difficult man to get on with, and a wide divergence in their intellectual outlook must soon have made itself felt. One of FitzRoy's early questions was: "Shall you bear being told that I want the cabin to myself? when I want to be alone. If we treat each other this way, I hope we shall suit; if not, probably we should wish each other at the devil." His temper was violent, but Charles

1 See Robert FitzRoy and Charles Darwin, by Nora Barlow, Cornhill Magazine, April, 1932.

[page] 34 DARWIN

would always avoid a quarrel if he could, and they kept an affection and essential respect for each other's integrity to the end of the voyage, in spite of "several serious quarrels".

Severe he was in carrying out his duties as Commanding Officer; but it was a severity combined with strictest justice and led to a contented ship and loyal officers. They admired his courage and magnificent seamanship, and many of the crew had been with him and Captain King on the earlier voyage. In Memories of Old Friends, by Caroline Fox, Vol. II, there is a tribute to FitzRoy worth quoting, with an unsolicited testimonial of the warm admiration of his officers. "Lieutenant Hammond dined here. He was with Capt. FitzRoy on the Beagle, and feels enthusiastically towards him. As an instance of his cool courage and self-possession, he mentioned a large body of Fuegians, with a powerful leader, coming out with raised hatchets to oppose them. FitzRoy walked up to the leader, took the hatchet out of his hand, and patted him on the back; this completely subdued his followers."