[page i]

Charles Darwin's Notebooks, 1836-1844

[page ii]

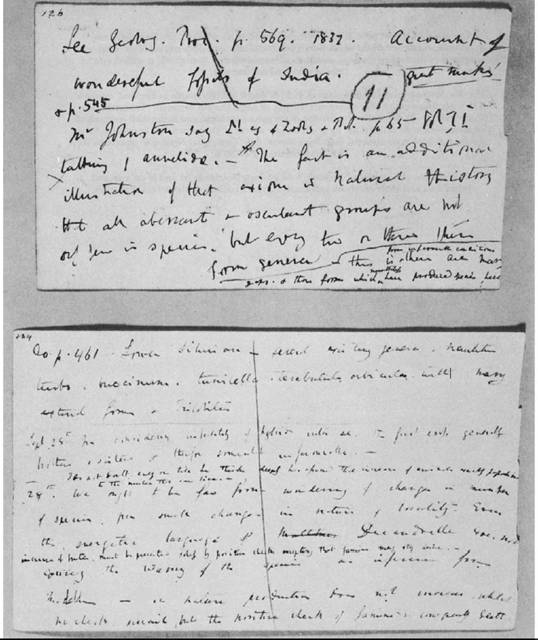

Notebook pages B126e and D134e (see pp. 201, 374-75 for a transcription). B126e was originally written c. September 1837, while the note in the bottom corner—transcribed in bold—was added in grey ink between 29 July and 20 October 1838. The additions [in brown crayon] were made in December 1856, when pages were excised and distributed to topical portfolios: 11 was the divergence portfolio (see Table of Location of Excised Pages, pp. 643-52). D134e was written in September 1838, when grey ink was Darwin's standard writing medium. The page was crossed in pencil, presumably after the note was of no further use.

[page iii]

Charles Darwin's Notebooks, 1836-1844

Geology, Transmutation of Species, Metaphysical Enquiries

Transcribed and Edited by

Paul H. Barrett Michigan State University

Peter J. Gautrey Cambridge University Library

Sandra Herbert University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Sydney Smith St Catharine's College Cambridge

[page iv]

© 1987 by Paul H. Barrett, Peter J. Gautrey, Sandra Herbert, Sydney Smith

[page v]

Contents

Acknowledgements vii

Historical Preface Sydney Smith 1

Introduction 7

Sandra Herbert & David Kohn

RED NOTEBOOK [1836-1837] 17

Transcribed and edited by Sandra Herbert

Geology

Notebook A [1837-1839] 83

Transcribed and edited by Sandra Herbert

Glen Roy Notebook [1838] 141

Transcribed and edited by Sydney Smith, Paul H. Barrett, & Peter J. Gautrey

Transmutation of Species

Notebook B [1837-1838] 167

Transcribed and edited by David Kohn

Notebook C [1838] 237

Transcribed and edited by David Kohn

Notebook D [1838] 329

Transcribed and edited by David Kohn

Notebook E [1838-1839] 395

Transcribed and edited by David Kohn

Torn Apart Notebook [1839-1841] 457

Transcribed and edited by Sydney Smith & David Kohn

Summer 1842 472

Zoology Notes, Edinburgh Notebook [1837—1839] 475

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

Questions & Experiments [1839—1844] 487

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

[page vi]

Metaphysical Enquiries

Notebook M [1838] 517

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

Notebook N [1838-1839] 561

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

Old & Useless Notes [1838-1840] 597

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

Abstract of Macculloch [1838] 631

Transcribed and edited by Paul H. Barrett

Table of Location of Excised Pages 643

Bibliography 653

Biographical Index 693

Subject Index 701

Symbols used in the transcriptions of Darwin's notebooks

< > |

Darwin's deletion |

« » |

Darwin's insertion |

bold type |

Darwin's later annotation |

[ ]CD |

Darwin's brackets |

[ ] |

Editors' brackets |

e |

Wholly or partly excised page |

[page] vii

Acknowledgements

[...]

[page x]

Charles Darwin's Notebooks, 1836-1844

[page] 1

Historical Preface

Sydney Smith

The documents here newly transcribed with the benefit of contemporary insight sustained by computer technology, are survivors from Darwin's period of maximal diversification of interests which drove him to make abstracts of everything available in print. This was, moreover, about the last time when such an activity was within the capacity of a single man. The results accumulated in the family home, extended to house the growing family and essential staff, record forty years of writing and experimenting, mostly written on high-quality paper made from linen rags.

Down House, Downe, Kent is today the store of material covering Darwin's life up to the return from the Beagle voyage. Papers relating to domestic matters, Darwin's health and activities in the garden, poultry and pigeon houses and so on are also at Down. The major store and site for accumulation of most of Darwin's working papers and significantly important manuscripts, and of the contents of this book, is the Darwin Archive of Cambridge University Library. It is my concern to give in outline the occasionally chaotic history and to record and give thanks for the recent and continuing generosity of contemporary members of the Darwin family and others. The Archive at Cambridge is incomparable in richness and as yet incompletely exploited treasure.

This volume aims to cover the years 1836 to 1844 when the theory of transmutation was conceived and was drafted in pencil in 1842 (DAR 6) to the second version of 1844 (DAR 7). Following the death of Emma in 1896, the manuscripts of the original sketches of 1842 and 1844 were found in a cupboard under the staircase at Down House. Supplementing the manuscript versions Darwin, plagued by ill-health and fearing premature death, had a fair copy (DAR 113) made in 1844 by Mr Fletcher, the Downe schoolmaster, which was interleaved for additions and corrections. This copy was returned to Darwin in September, 1844 and corrected by him against the original manuscript. On the 21st of the month Mr Fletcher, for his 'Species theory copying' was paid the sum of £2.0.0. In the event of his death, Darwin's wife Emma was charged with revealing the contents with the help of individual friends.

Public knowledge of the extent and quality of manuscripts, furniture, photographs and portraits in the family became clear when the Linnean Society of London celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the meeting on 1 July 1858, at which the Darwin-Wallace communications were read by the Secretary. In 1909, the centenary of Darwin's birth and the fiftieth year after the 'Origin' was published, was made an occasion for celebration in Cambridge 22 to 24 June. At the same time an exhibition was mounted in the Old Library of Christ's College. The catalogue and also the Easter Term issue of the College Magazine should not be neglected. Most of the material in the Cambridge exhibition was also exhibited with many items from the British Museum (Natural History) in a further display in London in July. The Director of the Museum, Sir Sidney F. Harmer and Dr W. G. Ridewood, published a document of great significance to scholars, as some of the loans from the Royal College of Surgeons' Museum in Lincoln's Inn were lost in air raids on London during the War of 1939—45. The catalogue Memorials of Charles Darwin, 1909, was re-issued in 1910 and might well be reprinted, but not I fear for sixpence a copy. As Harmer says in the Preface:

it seemed best to illustrate some of Darwin's arguments by means of specimens, using as far as possible the species to which he himself referred in his writings, and in some cases the material which actually passed through his hands.

[page] 2

At that time it is interesting to see that apart from notebooks of the Beagle period, only Notebook M, dealing chiefly with expression (item 42) was exhibited. Every delegate at the Cambridge celebrations had been given a printing of the pencil manuscript of the first (1842) version of the 'Origin'. Francis re-issued this and also the version of 1844 entitled 'The foundations of the Origin of Species'.

After the celebrations in 1909 Francis Darwin resided at 'Wychfield', his house in Cambridge with a few favourites from among his father's books. He also kept on his research room in the Botany School where his old assistant would set up plants for him to confirm or perhaps extend older measurements. He wrote an introduction to the Collected Works of his brother George, the Plumian Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge who died in 1913. He wrote on natural history and continued his lifelong practice at music—playing the bassoon in chamber works. He died in 1925 and left the residue of his father's library to the Botany School where they were distributed as reading copies on the open shelves and where, amongst other works by Herbert Spencer, Darwin's annotated numbers of his Principles of Biology were stumbled on. In 1925 Darwin himself was underrated. Francis left the great accumulation of documents assembled for Life and Letters, published in 1887, and with A. C. Seward, the two-volume More Letters, published in 1903 which weighted most essentially the scientific content of the published correspondence. Difficult subjects as Cirripedes and Pigeon breeding were still left on one side. Bernard, the inheritor of this accumulation, moved into 'Gorringes', a former dower house on the Lubbock estate in Downe village. Following the death of his wife in 1954 he moved to Kensington, where he died on 16 October 1963.

The more esteemed of the manuscripts belonged to Sir Charles Galton Darwin at the National Physical Laboratory: the Beagle Diary, and the manuscript 'Recollections of the Development of my Mind and Character', now called his 'Autobiography'. Owing to characteristic outspokenness in this work, complete publication was restricted during the lifetime of Leonard Darwin. He died in 1943.

On 4 September 1942, at one of the most troubled and difficult moments of World War II, Sir Alan Barlow, with his wife Nora at hand, wrote to the Librarian of Cambridge University as follows:

Dear Mr Scholfield,

The Pilgrim Trust have decided to buy certain MSS of Charles Darwin, with the intention that the main part should be given to the Cambridge University Library, and the rest to Down House. I am writing to ask whether the Library would be willing to accept the gift ...the greater number belong to Bernard Darwin & Mrs Cornford, and the rest to Sir Charles Darwin. I am co-executor with Bernard Darwin of the late Sir Francis Darwin, his and Mrs Cornford's father, and am writing on behalf of all three.

The proposal is to give to Down House, the diary of the 'Beagle' (the property of Sir Charles Darwin), which is at present deposited with you, the field notebooks from which it was compiled; certain smaller items relating particularly to Down; and Charles Darwin's personal account books; and to give the rest to Cambridge. The principle of the division is to let Down have a popular exhibit, & items specially relating to Down, but to keep together in the University Library the rest of the material, in order that it may be available for any future student of Darwin & his work. The material throws a good deal of light on his methods of work & the growth of his theory of Evolution & Natural Selection.

After specifying the location of Sir Charles (Galton) Darwin's MSS Sir Alan proceeds:

The rest of the material is in Sir Bernard Darwin's House-Gorringes, Downe, Kent. The Down

[page] 3

House Trustees have accepted the items offered to them, [they were transferred by October 1942] and Sir Charles Darwin will be writing to you to ask you to send the 'Beagle' Diary to them.

He concludes

We all feel the documents should be in a public library rather than in private ownership, & though sale in the U.S.A. would have produced more cash, we would like them to remain in this country. We should be glad that through the munificence of the Pilgrim Trust, they should find a home at Cambridge.

Yours very truly,

Alan Barlow.

On 14th October 1942 the University accepted the gift, but in spite of appeals from Bernard that the Library collect their property, the excuse of staff shortage to catalogue and process accessions, petrol rationing for carriage allowed the Librarian to remain inert and unresponsive. Somewhat exasperated, Bernard Darwin wrote 9 May 1946: May I remind you that yr Darwin documents are still here awaiting you, unblitzed and unburgled so far. Scholfield was invited for lunch. He replied that he could not commit himself and suggested carriage be undertaken by rail or by Pickfords. Bernard answered 22 May 1946: I am disinclined to send them off by rail or by Pickfords. Meanwhile a request to the Library from Sweden for permission to consult the Darwin material had been forwarded to Bernard by the staff for him to attend to. This produced this expostulation 31 August 1948:

I really do think it is time you sent for your property here ... I am most anxious to be quit of them and this sort of thing is not very encouraging to those who give. Do please take some step on this matter—I wish you would.

Mr Creswick, then Secretary of the Library, replied for Scholfield who was ill, and action to some purpose was at long last begun. Creswick was able to report to Sir Charles Darwin on 13 October 1948: Those MSS destined for Cambridge have been collected from Downe & Barclays Bank. There remained errors in assigning items between Down House and Cambridge to be set right, but there also remained items which were still missing. On 4 June 1949 when thanking Bernard for the gift of the 'Gorringes' 1932 catalogue, compiled by Miss Catherine Ritchie, Creswick concluded:

... all our efforts are being directed to completing the toll of known Darwin manuscripts and their present whereabouts in the interest of posterity and the fame of your great ancestor.

The 'Edinburgh Notebook' was missing. It was known to have been borrowed by the late Professor Ashworth who had Professed Zoology at Edinburgh University. Sir Charles Darwin as well as Bernard were approached, and the Librarian of the National Library of Scotland was asked to help sort things out. The widow of Professor Ashworth was able to supply the receipt of the registered parcel conveying the loan back to Bernard on 28 August, 1935. Moreover, she still had the note from him acknowledging its return. He accordingly searched at 'Gorringes' with more care, to reveal the notebook tucked away in a locked drawer where I ought to have looked before. (Letter 7 February 1949)

Meanwhile his wife's own search turned out the massive and important 'Diary of observations on Zoology of the places visited during the voyage'. Both items were sent to the

[page] 4

Library 7 February 1949. Reporting these events to Mrs Ashworth in a letter 8 February, Mr Creswick concluded:

... my enquiries about the Edinburgh notebook is complete success. This is to large extent due to your kindness in allowing me to see the papers relating to the use of the Notebook, and its return in 1935. My letter to Mr Darwin was so convincing, that he made a further search and found it together with a great bundle of other papers all in Charles Darwin's hand. We have therefore, as good reason to be grateful to you as if you had presented us with a valuable manuscript for the Library.

It seems fair to conclude that Bernard did not know where the items still required to complete the gift to Cambridge may be in his house. The list of undelivered material was sent to Bernard on two occasions, without any response. In preparation for the move to Kensington, miscellaneous treasures which were outside the 'Gorringes' catalogue were placed in Box 'B' and the Box put into store. These items included Erasmus Darwin's correspondence with his contemporary Richard Lovell Edgeworth, author and inventor, together with part of a letter from Benjamin Franklin while he was U.S. Ambassador in Paris, as well as a great treasure of family letters which have proved invaluable for giving continuity to the Correspondence. Some items missing from Boxes A, C, D and E, reappeared over a period, but there were a small number still missing and not traced. Box 'B' had labels tied to a handle; an old dirty one inscribed 'Box "B" CD', seemingly dating from the division of the manuscripts between the five Boxes A to E. The other label was newer, 'B. Darwin 26/9/56, John Barker & Co. Ltd. Depository. Cromwell Crescent. W.' It seems that Bernard had the Box in his flat for about two years.

Box 'B' reappeared when Barker's ceased trading as a separate store and merged with Derry & Toms. The Box was returned to Bernard's custody, but was housed in the basement of the Science Museum, close to the Royal College of Art where Sir Robin Darwin, Bernard's son, was Principal. There was already other Darwin material deposited there: notably the letters sent to Darwin from the 1860s when he had to assume responsibilities congruent with his public notoriety; and in addition, observations shared by both Charles and his son Francis which hovered on the edge of Charles' own work and continued by Francis after his father died. When arranging his father's manuscripts, Francis overlooked this joint work, so much of the material on the Power of Movement in Plants appeared.

The storage in the Science Museum seems to have been arranged while Sir Terence Morrison Scott was Director. When he became Director of the British Museum (Natural History) the boxes moved with him. Sir Robin Darwin, informed of this mislaid property now assembled for inspection, wrote to Lady Barlow suggesting she and I call for an appraisal. This we did on the morning of 22 March 1962, initially meeting with Miss Skramovsky, secretary to the former Director, Sir Gavin de Beer, who still retained working space in the library of the Museum. The black metal deed box, its lock burst open by force, was filled with a confusion of manuscripts, amongst which was a small sealed envelope inscribed by Francis Darwin: 'Box C. D5. Darwin's Journal'. This is the description in the 'Gorringes' list. 'C implies the Journal had been removed from Box 'C, and moreover Francis signed the sealed envelope before 1925. It seemed probable that the arrangement of the documents was done by Francis, possibly with his father. I handed the envelope to Lady Barlow saying you should open this. The long-lost, original Journal was inside and we were released from the tidied up, distorted travesty from which Sir Gavin de Beer produced the reprint. After lunch with Sir Robin, we adjourned to his office at the top of the Royal College of Art where we were shown the books from Box 'H'. These consisted of Darwin's copies of his works with corrections; and additions, together with copies formerly belonging to the family. These books were for sale

[page] 5

and our advice was sought as to their possible value. We told Robin of the high significance of the volumes and suggested an expert should be consulted about their value. In the end, all the books reached Cambridge University Library a few months later the gift of an anonymous donor.

The envelopes listed in the 'Gorringes' catalogue under C.40 were found to contain most of the excised pages from the notebooks transcribed on the pages that follow. Marked with the number of envelope in crayon, the pages were cut out by Darwin, 'B' notebook, 7 Dec. 1856; 'C, 13 Dec. 1856; 'D', 14 Dec. 1856, and finally 'E', 15 Dec. 1856. Some pages are to be found in other places in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge, but the majority have been located in the C.40 envelopes in Box 'B' and now mounted in volumes DAR 205.1-11.

Shortly after this great day in London, Sir Robin agreed to the deposit of Box 'B' with the University Library in Cambridge but, while access was possible, the contents of 'B' were so chaotic that it took a good time to decide which of the materials were still Robin's property. Things were not finally agreed upon when he died suddenly in January 1974. He bequeathed to his two sisters those manuscripts in the black Box 'B' which had been placed therein entirely independent of the 'Gorringes' list. This was an exacting task, but by agreement with Sir Robin's lawyers, funds already given to the Library together with a matching Government Grant aimed at safeguarding for the Nation manuscripts of great importance, money was made available to provide annuities for the two sisters. The greater part of the excised pages were later transcribed by de Beer, Rowlands and Skramovsky and published in Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Historical Series. Issued in 1967, this work was read by me in proof. There has been difficulty in studying the notebooks in scattered publications, which is why the present attempt to bring them together in a seemly fashion was an urgent task. During many years of my serious indisposition the colleagues whose labours complete the work have earned my warm gratitude and I am sure the respect of future readers.

NOTE: All correspondence relating to the original gift is to be found arranged in chronological order in DAR 156.

[page] 6

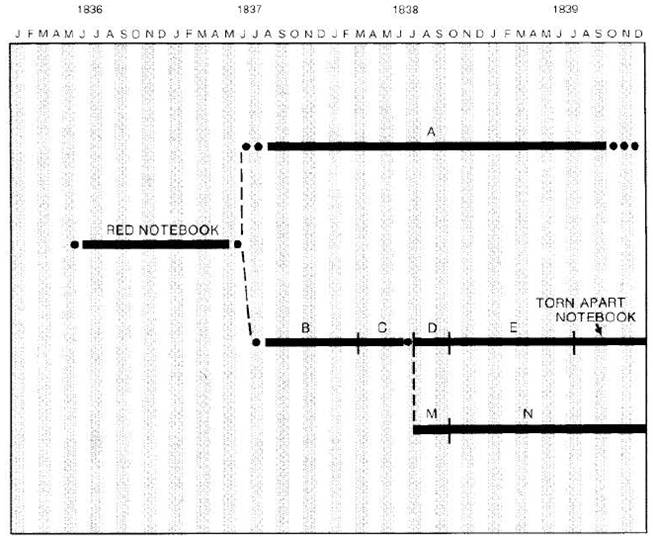

Fig. 1 Nine Darwin notebooks from 1836 to 1839. Solid lines represent the notebooks, dotted lines uncertainties in dating, and broken lines divisions of subject matter among members of the set.

[page] 7

Introduction

SANDRA HERBERT & DAVID KOHN

The English naturalist Charles Darwin lived from 1809 to 1882. Through his writing he affected the content and growth of science to a degree rarely matched in its history. This volume contains eleven notebooks and four related manuscripts from his most creative years as a theorist. In the notes contained in this volume he developed many of the major ideas contained in several of his geological publications, in On the Origin of Species (1859), The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868), The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872).1 These notes thus contain in outline the main programme of research and publication he was to follow during his life. They illumine his intellectual development and display the power and direction of his mind as scientist and as author.

The subtitle of this work 'Geology, Transmutation of Species, Metaphysical Enquiries', is drawn from Darwin's own words. He labelled one notebook 'Geology', one group of notebooks he characterized as being 'on Transmutation of Species—', and another notebook he described as being 'connected with Metaphysical Enquiries'.2 The earliest notes in this collection date from 1836, when Darwin was 27 years old and returning home from his service as naturalist aboard H.M.S. Beagle during the years 1831-36; the latest explicitly dated notes made in regular sequence are from 1844, though later entries exist.3

As an edition, this work is simultaneously a work of fresh publication, of restoration and, within limits, of interpretation. As a work of fresh publication it provides texts of six previously unpublished manuscripts: Notebook A; the Glen Roy Notebook; the extant pages of what we have characterized as the Torn Apart Notebook; the Summer 1842 Notes; the Zoology Notes, Edinburgh Notebook; and a notebook labelled Questions & Experiments. As a work of restoration this edition offers an integrated version of Notebooks B, C, D and E. When these were first published by Gavin de Beer in 1960, only pages still extant in the notebooks were included.4 Darwin had excised numerous pages from his notebooks for use in later writing, and the location of these was then unknown. After the original publication of the notebooks, the majority of the pages excised by Darwin were found and published in 1961 and 1967.5 While that publication was an appropriate solution at the time, it was not a lasting one since it is clearly an advantage to be able to read the notebooks straight through, as they were written, without having to consult separate publications. In the present edition that defect is corrected, the excised pages from Notebooks B, C, D and E having been replaced in their original positions. Other improvements have also been made in this edition. Most especially, care has been taken to note the layering of the manuscripts with respect to date.

1 The standard guide to Darwin's publications is Freeman 1977. For concordances to Origin, Descent, and Expression see Barrett, Weinshank and Gottleber (1981); Barrett, Weinshank, Ruhlen and Ozminski (1987, in press); and Barrett, Weinshank, Ruhlen, Ozminski and Newell-Berghage (1986).

2 Notebook A is labelled 'Geology'. In his 'Journal' begun in August 1838, Darwin referred to Notebook B as follows—'In July [1837] opened first note Book on "transmutation of Species".—' and to Notebook M as follows 'opened «note» book, connected with Metaphysical Enquiries.' De Beer 1959:7—8, and for a text corrected against the original manuscript, Correspondence 2:431—32.

3 See the Introduction to Questions & Experiments. The bulk of the notebook was completed by 1844, its latest explicit date. However, 1845-46 references do exist, and the date of last use of the notebook remains uncertain.

4 De Beer 1960. The unexcised pages of Notebook B were also published in Barrett 1960.

5 De Beer and Rowlands 1961; De Beer, Rowlands, and Skramovsky 1967.

[page] 8

In addition to being a work of fresh publication and restoration, the present edition is also, within limits, a work of interpretation. It is so in its grouping of manuscripts. In publishing the geological and the metaphysical notebooks alongside the transmutation notebooks, the editors are taking a synthetic view of Darwin's endeavours. His work as a geologist and his enquiries concerning man and behaviour are presented as integral to the formation of the species theory and to the development of his scientific outlook generally. Reading his geological notebooks alongside his transmutationist notebooks allows one to observe the connections between his views on species and his questions regarding the origin and structure of the earth. For a somewhat different reason, reading the metaphysical notebooks alongside the transmutation notebooks one perceives more readily what gains accrued to Darwin's theory from his own reading in traditions outside natural history. Were one to read more narrowly, these perspectives, and with them a sense of the integrity of Darwin's work, might be lost.

The seven notebooks lettered alphabetically—Notebooks A, B, C, D, E, M and N—form the core of this edition. They define the centre of the notebook period, summer 1837 to summer 1839, and elaborate its key topics: geology (Notebook A), transmutation of species (Notebooks B to E), and metaphysical enquiries (Notebooks M and N). The other eight manuscripts relate directly to this core. The Red Notebook contains both geological and transmutationist themes and was the predecessor to the later notebooks. The Glen Roy Notebook, while primarily a geological field notebook, contains occasional observations on breeding and instinct. The Torn Apart Notebook was a direct continuation of Notebook E, the brief Summer 1842 Notes being on related themes but later. The Zoology Notes, Edinburgh Notebook were a series of notes running roughly parallel in time and subject matter to the transmutation notebooks. Questions & Experiments carried forward transmutationist themes by a set of questions on breeding and inheritance and by a record of experiments to be tried on these subjects. The Old & Useless Notes and the Abstract of Macculloch complimented the major themes of Notebooks M and N.

In addition to forming the core of this volume, the alphabetically lettered notebooks bear a generative relationship to one another, the subject of transmutation serving as the stimulus for the differentiation of the group. During the years Darwin kept these notebooks he moved from asserting transmutation as an hypothesis to constructing a full theory of its operation. Before opening these notebooks he knew of the state of opinion on the subject and, while on the Beagle voyage, commented on it, often tangentially. In March 1837 after London zoologists had examined a number of the specimens he had collected on the voyage, he was ready to take up the transmutationist hypothesis. Darwin's earliest known explicitly transmutationist statements occur in the Red Notebook, scattered amongst observations and reading notes, primarily on geology. When this notebook was filled, Darwin began Notebooks A and B. Notebook A, devoted primarily to geology, he filled gradually over two years. Notebook B, devoted entirely to the subject of the transmutation of species, he filled relatively rapidly. It was succeeded in turn by Notebooks C, D, E and the Torn Apart Notebook all devoted to transmutation. In addition, in the course of keeping Notebook C, Darwin recorded an increasing number of observations on man, behaviour, and the metaphysical and epistemological implications of transmutation. When Notebook C was filled, Darwin opened a new parallel series of notebooks, labelled sequentially 'M' (possibly for 'metaphysics') and 'N', devoted to exploring his new interests. Meanwhile, in Notebook D Darwin first formulated the concept of natural selection, which he elaborated in subsequent notebooks. Over time, the scheme of these notebooks can be represented as illustrated in Fig. 1. Although Darwin stopped using notebooks to record his views in the 1840s, he continued to

[page] 9

make notes on transmutation, which he organized into subject portfolios, through the rest of his career. The formal writing of the Origin went through three stages before publication: two drafts—the 1842 Sketch and the 1844 Essay; a long version of the argument, Natural Selection, never published in his lifetime; and, finally, the Origin itself in its first and subsequent five editions. Darwin's geological notes in the Red Notebook and in Notebook A were incorporated into various of his later publications. Material from Notebooks M and N appeared primarily in The Descent of Man and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

In addition to the fifteen manuscripts included in this volume are others bearing on its subject that were excluded only for practical reasons. The Red Notebook itself has a predecessor in the form of 34 numbered pages at the back of a field notebook from the Beagle voyage labelled 'Santiago Book'. Begun in 1835, these pages contain entries of a theoretical nature and are directed towards future publication.6 From the post-voyage period the 'St. Helena Model' notebook, begun in 1838, records Darwin's notes on his observations of Robert Seale's topographical model of that island, as well as some entries directed towards the species question.7 In addition to notebooks, there are in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University Library a considerable number of loose notes from the 1836-44 period that bear on the subject matter of the notebooks published here. Among these are notes, catalogued in the library as DAR 29, regarding specimens from the Beagle voyage. Also of interest are Darwin's collection of abstracts of books and scientific periodicals similar to the Abstract of Macculloch.

Entries in the majority of the fifteen manuscripts in the present collection are directed towards the construction of theory. They represent a series of brief expositions, memoranda and reading notes: theory in the process of gestation. Since the arguments presented in the notebooks were in the early stages of formation, they display the probing and discursive logic of discovery rather than the coherent and fully articulated logic of final exposition. In addition, to the reader familiar with On the Origin of Species, the notebooks may initially seem foreign, for where the Origin, at least in its first edition, offered few clues to its antecedents, the notebooks served as Darwin's record of his sources. Also in these manuscripts Darwin frequently reflected on the subject of scientific method with regard to his own work, as, for example, in his comment in [Notebook] D117: 'The line of argument «often» pursued throughout my theory is to establish a point as a probability by induction, & to apply it as hypothesis to other points. & see whether it will solve them.—'

The notebooks are also revealing of Darwin's day-to-day practice as a scholar. In the notebook texts, reading notes are abundant and useful for assaying questions of influence, but one can also find connections between the texts and Darwin's marginal comments in books from his own library, sometimes, as in the John Phillips' references in A147, transferred

6 The notebook labelled 'Santiago Book' is stored at Down House, Darwin's former home in Kent, with the other field notebooks from the voyage. It is catalogued as 1.18. Darwin's first statement of his theory of coral reef formation is contained in the set of numbered pages at the rear of the notebook. For a transcription of the coral reef entries see Correspondence 1:567—71. Also see Barlow 1945:243—44.

7 The notebook labelled 'St. Helena Model' is catalogued as 1.5 and stored at Down House, no doubt because it was believed to have been a product of the voyage. However, the notebook appears rather to be post-voyage in date, possibly having been opened in September 1838. On 12 September 1838 Darwin wrote a letter requesting permission to study the large plaster model of St Helena constructed by Robert F. Seale and housed, from at least as early as 1826, at the East India Company's Military College at Addiscombe (Correspondence 2:103, Seale 1834:8). Entries in the first fifteen pages of the notebook appear to correspond with a trip by Darwin to see the model and pertain to craters, which suggests a relation with Darwin's comment that in September 1838 he 'Began craters of Elevation Theory' (Correspondence 2:432, VI:93-96). The notebook continues into late 1838 and had some use in 1839. For quotations from it see Barlow 1945:257-60. Gordon Chancellor is presently preparing for publication an edition of the complete notebook. He has generously shared his work on the notebook with the editors of this volume.

[page] 10

directly from book margin to notebook page. With regard to Darwin's note-taking, the organization of the notebook occasionally changes in such a way that reveals a new category of meaning emerging, as in the notes on generation that begin a separate section of Notebook D at page 152. The notebooks also bear evidence of recurrent use, for Darwin repeatedly culled them for ideas and references. For an early instance of Darwin's re-reading of and commentary on his own work see B153 quoting the Red Notebook; for a much later example of re-reading see A33.

The circumstances under which Darwin kept the majority of notes in this collection were conducive to concentrated intellectual effort. With an income provided for him by his father, he set his own course. The prospect of his becoming a clergyman had evaporated during the voyage.8 For a time he believed a Cambridge professorship would be required to provide a living, but even that proved unnecessary.9 A handsome marriage settlement further secured independence.10 In addition to leisure, Darwin also benefited from a change in venue, for during most of the notebooks' period he lived in London. His places of residence were as follows: 16 December 1836 to 6 March 1837 lodgings in Fitzwilliam Street in Cambridge, a week's stay at his brother's house at 43 Great Marlborough Street in London, then from 13 March to 31 December 1837 furnished rooms at 36 Great Marlborough Street, from 1839 to September 1842 a house for himself and his bride at 12 Upper Gower Street after which the family moved to Down House in Kent.11 (Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood on 29 January 1839.) It was the presence in London of the major scientific societies and institutions that had drawn him to the city, and, once there, he found peers. In turn he was valued. In 1841, as Darwin was contemplating departure from London, the geologist Charles Lyell wrote to him:

It will not happen easily that twice in ones life even in the large world of London a congenial soul so occupied with precisely the same pursuits & with an independence enabling him to pursue them will fall so nearly in my way, & to have had it snatched from me with the prospect of your residence somewhere far off, is a privation I feel as a very great one—12

Darwin's life in London was not circumscribed by science, however, and through his brother Erasmus Alvey Darwin he met Harriet Martineau, Thomas and Jane Carlyle, and other literary figures. On 21 June 1838, in recognition of his accomplishments, Darwin was elected to the brilliantly populated Athenaeum Club (in the same class as Charles Dickens) and in its library read extensively while keeping Notebooks M and N.13

Darwin's chief, and related, occupations during his London years were establishing himself in its scientific world and bringing to completion work from the voyage, which task included publication of his own observations and arranging for the disposition of his collections. On the first count, Darwin chose to make his way in London primarily as a geologist. Early in the voyage he had decided to write 'a book on the geology of the various countries visited', and in keeping with that goal, even before the end of the voyage, had arranged for himself to be put up for election as a Fellow of the Geological Society of London.14 Immediately upon arriving

8 See Darwin's letters to his cousin William Darwin Fox in Correspondence 1:316, 432, 460.

9 Correspondence 2:443.

10 Correspondence 2:119.

11 Correspondence 1:542; 2:430 (but see p. 8 for a possible 3 March date), 10-11, 435 n. 5, 432, 435.

12 Correspondence 2:299. On Lyell's relationship with Darwin in his London years see L. G. Wilson 1972, chap. 13; also see Sydney Smith 1960:396-98.

13 Correspondence 2:94 n. 2.

14 Barlow 1958:81; Correspondence 1:499, 517.

[page] 11

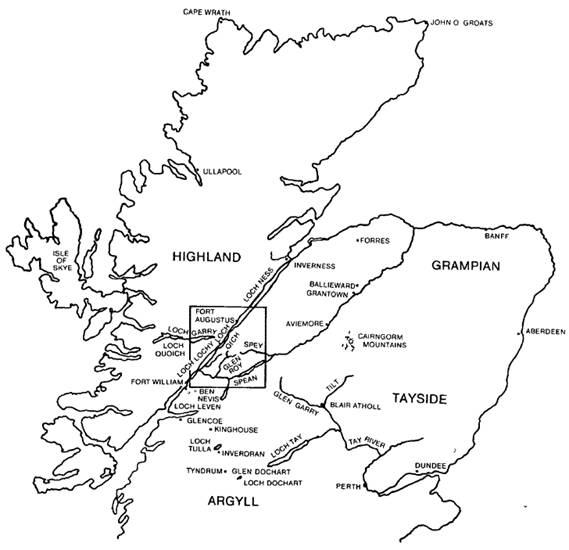

home he began attending meetings of the Society and very soon presented papers before it and served as one of its officers. Darwin also began a new project during this period, undertaking a trip to Scotland at the end of June 1838 in order to formulate an explanation for the origin of the so-called 'parallel roads' of Glen Roy. This work was published in the Transactions of the Royal Society of London, of which he became a Fellow in 1839.15 Geology aside, Darwin also participated in the more general scientific life of London, including attendance at numerous meetings and lectures, possibly including the 1837 Hunterian lectures of Richard Owen at the Royal College of Surgeons.16

With regard to publishing results from the voyage Darwin made rapid progress. He recast his diary from the voyage into book form on his return to London in early March 1837 to about 25 June, sending a manuscript to the publisher in early August and receiving proof later that month and into the autumn. As publication was delayed, he added a preface and addenda to the book in October 1838.17 His Journal and Remarks on the voyage was in his hands in May 1839.18 In the autumn of 1837, as he was finishing proofs for the Journal, Darwin 'Commenced geology'.19 Although much delayed by illness and by his increasing attention to the species question, the geology emerged in three parts: The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842), Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (1844), and Geological Observations on South America (1846).

On the zoological side Darwin's immediate task following the voyage was to arrange for his collections, which had been sent back to Henslow, to be dealt with by competent specialists. He spent much of the winter of 1836—37 in Cambridge unpacking and sorting his specimens. At the same time he had already begun to place some of the specimens with individuals who would be responsible for classifying and describing them. In August 1837 he received a Treasury grant of £1,000 to support publication of their findings.20 In the autumn he planned for the work that would emerge, noting in his 'Journal' under the year 1837 that he was in 'October—November.⎯ preparing scheme of Zoology of Voyage of Beagle.'21 With Darwin assisting the specialists at every step, the Zoology from the voyage was published in five parts made up of nineteen numbers over a five-year period from 1838 to 1843. The parts were assigned as follows: Fossil Mammalia, Richard Owen; Mammalia, G. R. Waterhouse; Birds, John Gould (with assistance of T. C. Eyton and G. R. Gray); Fish, Leonard Jenyns; and Reptiles, Thomas Bell.22 Reports on other portions of Darwin's collections appeared subsequently in various formats.

In the course of placing his collections, Darwin became a respected member of London's botanical and zoological circles. His working ties with Robert Brown and Richard Owen made him a frequent visitor to the British Museum and to the Royal College of Surgeons. Through his collaboration with John Gould and George Robert Waterhouse in work on

15 Darwin 1839; Correspondence 2:433.

16 Sloan 1986:398—432. On the institutional milieu of zoology in London see Desmond 1985.

17 Correspondence 2:432.

18 According to The Publisher's Circular of 1 June 1839, Darwin's Journal and Remarks, vol. 3 of Fitzroy 1839, was published between 15 May and 1 June 1839. The separate publication of Darwin's book, retitled Journal of Researches, was first advertised in The Publisher's Circular

of 15 August 1839.

19 Correspondence 2:431.

20 Correspondence 2:37—39.

21 Correspondence 2:431, 17. The scheme of publication was altered after its inception. Freeman 1977:26 cites an 1837 prospectus for the work stating that 'a description of some of the invertebrate animals procured during the voyage will also be given. At the conclusion of the work Mr. Darwin will incorporate the materials which have been collected, in a general sketch of the Zoology of the southern parts of South America.' As Freeman points out, neither of these intentions was realized. However, it is possible that some of the entries in the Zoology Notes, Edinburgh Notebook were directed towards them.

22 Zoology; on the assistance of Eyton and Gray see Freeman 1977:29—31.

[page] 12

specimens from the Beagle voyage, Darwin came to attend the meetings of the Zoological Society, where descriptions of his voyage specimens were read, and to visit the Society's gardens. Over the notebook years, these biological contacts and interests would expand, and Darwin would become recognized as one of London's most accomplished young naturalists, as well as a well-published geologist.23

Each one of Darwin's occupations immediately following the voyage proved instrumental in establishing his stature as an author of wide influence. His narrative of his travels and his articles for scientific journals established his credentials as a writer on both popular and specialized topics. His work on the Zoology from the Beagle voyage gave him experience in organizing a major editorial enterprise. And all of these activities brought him in contact with the personalities and ideas of the men who formed the community of naturalists that Darwin would always regard as the prime audience for his work.

Amidst all these public activities, in the years Darwin would characterize as the most active ones he ever spent, he opened the private notebooks that comprise this edition. In them he took up the question that would unify biology and give definition to his own life: the transmutation of species.

EDITORIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The primary goal of the editors has been to provide an accurate transcription of Darwin's text. While the aim has not been to produce a facsimile in type, the editors have attempted to capture those elements in the text that are important for meaning. The method of transcription adopted is a modified version of that described by Fredson Bowers.24 Following that method the text is printed together with a set of textual notes containing editorial comments concerning the transcription. These notes are keyed to the text by a quotation from it followed by a lemma. In the textual notes Darwin's words are printed as in the text, the editors' comments in italics. For an illustration of editorial method the reader may compare the two manuscript pages reproduced as a frontispiece to this volume with the published text for the pages. [Omitted from this online version.]

In transcribing Darwin's text all words and fragments of words are recorded. Deletions are enclosed by single angled brackets < > . Superimpositions are noted in the textual notes, as in the phrase ' "a" over "o" ' meaning that the letter 'a' is written over the letter 'o'. Superimpositions of the same letter (an 'a' over an 'a' for example) are ignored. Insertions in the text are set off by double angled brackets « ». If their placement on the page is unusual, that fact is recorded in the textual notes. Entries in the notebooks are regarded as insertions if they appear to have been written out of sequence as compared to other entries on the page. Insertions would include careted remarks and afterthoughts generally. Annotations are recorded in the text in bold face type.

To decide whether to record an out-of-sequence entry as an insertion or as an annotation is difficult. An insertion is an addition to the text thought to be contemporary with the original entry. An annotation, on the other hand, is a note or comment made after the fact, that is, at some time after composition of the original entry. The editors have attempted to distinguish between these two categories. The most common sign of annotation has been taken to be a

23 On the interplay between Darwin's public and private lives in science during these years see S. Herbert 1974—77 and Rudwick 1982.

24 Bowers 1976. Tanselle 1978 has also been used as a guide to editorial standards.

[page] 13

change in writing medium. Where an out-of-sequence entry is written in the same medium as its surrounding passage, the entry will usually be taken to have been an insertion. Only if there are other signs suggesting addition at a later date—as, for example, having been written diagonally across a page over existing script—or some indication from the content of the entry that it must have been written well after the original passage, will the entry be treated as an annotation. An example of an easily identified annotation is the entry in brown ink on RN38, 'V. back of page 1 of New Zealand Geological Notes'. This entry stands out sharply from the other entries on the page, which are in pencil, and was obviously squeezed on to the page after the original entries were made. Of course, not all cases are so clear cut, and where there has been doubts our inclination has been to treat out-of-sequence entries as insertions rather than annotations. No systematic attempt has been made to date annotations. However, certain annotations which appear in grey ink, discussed below, can be assigned a definite range of dates. Also, brown-crayon numbers, indicating subject portfolios, were added to many excised pages in the 1850s. On this see the 'Table of Location of Excised Pages'. At points in the notebooks, and always at the beginning and end, one must be cautious in inferring temporal sequence from physical sequence. Thus, for example, Darwin used the inside of the covers of notebooks as convenient, and the ordering of entries must there be regarded as problematical. In addition, the entire Questions & Experiments Notebook was filled in a more complicated manner than front to back.

Other difficulties in transcription pertain to symbols, abbreviations, spelling (and its attendant problem of handwriting), punctuation, variation in media, and the treatment of excised pages.

With respect to symbols and abbreviations the editors have preserved Darwin's usages in so far as they can be brought gracefully into print. Darwin's use of the ampersand and plentiful employment of the dash are unaltered; and his abbreviations 'do' for 'ditto' and 'V.' for 'Vide' remain unexpanded. Darwin's own figures and sketches have been traced or, where feasible, reproduced photographically from manuscript. Two idiosyncratic markings have also been kept: first, a backwards question mark that he borrowed from Spanish, and a cross-hatch he used on occasion for emphasis. Darwin's underlinings have been reproduced according to printers' conventions: one line, italics; two lines, small capital letters; three or more lines, large capital letters. Where underlinings are annotations they are recorded in the textual notes ('underlined'). The lines Darwin often used to separate entries, his 'rule lines', have been reproduced according to the following convention: a rule line taking up one quarter or less of the notebook page is transcribed as a short line, a rule line taking up between one quarter and three quarters of the notebook page is transcribed as a medium line, and a line taking up three quarters or more of the page is transcribed as a long line. The marginal scorings that Darwin used for emphasis have not been reproduced in the text but are recorded in the textual notes, the passage in question being noted as having been 'scored'. Similarly, where Darwin circled or enclosed a word or phrase for emphasis, the fact has not been reproduced in the text but recorded in the textual notes, the word or phrase being noted as having been 'circled'. (However, where Darwin circled or half circled notebook page numbers that fact has not been recorded.) The vertical lines that run through much of the text of the notebooks were Darwin's indications to himself that he had made full use of the material. Passages so marked are recorded in the textual notes as having been 'crossed'. Finally, some of Darwin's markings elude succinct description. In such cases the editors have attempted to indicate Darwin's intention in so far as they could determine it.

In spelling the editors have preserved Darwin's practice where individual letters are clearly formed. Where individual letters are indistinct, as is often the case, the editors have offered the probable reading of the word without comment. Also, the slurring together of letters amounted to a kind of shorthand (for example, 'by' is often written as one curving stroke rather than as two

[page] 14

clear letters, or the 'e' in 'the' appears only as a tail), and here too the words have been spelled out in full. Where two readings of a letter are possible, as is, again, often the case, the editors have chosen what seemed from the context the more probable reading. Such ambiguities are particularly common with the vowels—for example, an 'a' being indistinguishable from 'or'. Where ambiguous readings are plausible in context, the editors have chosen one for the text and listed the other as an 'alternate reading' in the textual notes. Where the editors can do no more than guess at a reading, they have appended a textual note 'uncertain reading' to the word or passage. Where a section of text is illegible, bracketed ellipses marks ('[. . .]') appear in the text with a notation being made in the textual notes as to how many letters or words are illegible. In orthography Darwin's forms are standard with the exception of the long 's' (appearing as the first 's' of a double 's'), which has been modernized silently. In capitalization Darwin's usage has been preserved where it is clear. Where it is unclear, preference has been given to conventional usage.

In punctuation, as in spelling, the editors have attempted to follow Darwin's practice in so far as they could determine it. As R. C. Stauffer has pointed out, Darwin followed a system similar to that suggested in Lindley Murray's English Grammar.25 In that system, commas, semicolons, colons, and full stops or periods indicate increasingly longer pauses more than they distinguish different constructions. Thus Darwin might use a colon where a semicolon would now be employed. The editors have not altered Darwin's practice in this regard. More problematical for the editors has been the question of distinguishing commas from full stops and both from stray marks and pen rests. Here the editors have attempted to transcribe literally while being alert for signs of Darwin's intentions. The editors have not added punctuation where there is none.

Another issue in transcription is media. Customarily Darwin wrote in pencil or in pen and ink, with an occasional entry in crayon. The pencil he used was of the standard sort, except in the Glen Roy Notebook where he used a special metallic pencil that came with the notebook. The inks he used are usually shades of brown, grading into one another, presumably as a result of different inks being mixed in a common well. The distribution of pages written in ink and pencil is indicated in the introduction to each notebook. The medium of individual entries is recorded in the textual notes only where a change of medium occurs on the page. The colour of the ink Darwin used is noted systematically in only one case, where knowledge of its presence is helpful in dating entries. Darwin used a greyish ink from 29-31 July 1838 to 19 October 1838 (D21-E26 and M56-N18).26 During this eleven-week period, Darwin also added numerous grey-ink annotations to Notebooks B and C.

25 Natural Selection: 20-21.

26 These dates have been determined as follows. On 29 July 1838, Darwin set out from Shrewsbury to Maer in Staffordshire (Correspondence 2:432). His first known use of grey ink occurs in a page of observations on Staffordshire geology written as the continuation of brown ink notes on Shropshire geology (DAR 5:21-22, 'Alluvium/Shropshire/1838/July'). This document is a single folded piece of paper with the brown notes on 5:21 verso and recto followed by the grey notes on 5:22 recto. Darwin was at or in the vicinity of Maer until 31 July. The grey ink in the notebooks begins with Darwin at Maer on D21—after the second line—and on M56. The last dated use of grey ink is 19 October and occurs in E26. See textual note on E IFC for details. N18 is in grey ink up to, but not including, the entry dated 'Octob. 19th'.

[page] 15

With regard to excised pages, in all cases excisions, whole or partial, have been recorded. Where the excised material has been recovered, the location of the recovered material is given in the 'Location of Excised Pages'. Recovered material is noted as follows: the letter 'e' is given next to the page number in the text and, for partly excised pages, the word 'excised' appears in the textual notes together with an indication of the placement of the excision. Unrecovered material is indicated by the phrase 'not located'. On some excised pages, one can detect pin holes that once held pins attaching various sheets together. Pin holes are signalled by an asterisk next to the page number of the excised page in the 'Table of Location of Excised Pages'. It should also be noted in connection with excised pages that a fragment of a letter, a word, or a sentence sometimes appears on the stub of an excised page. The editors have checked all stubs for such material and have incorporated it into the text silently.

To aid the reader the texts in this edition are provided with explanatory footnotes. Most footnotes fall into two categories: (1) persons referred to in the text other than as authors, and (2) references to written work, usually books or articles. The first category of notes includes persons referred to in the text who are not being cited as authors and who thus require identification. Thus the 'Aunt Sarah' referred to on M83 is identified in a note as 'Aunt Sarah: Sarah Elizabeth Wedgwood'. In the biographical index she is further identified as the daughter of Sarah and Josiah Wedgwood I and her birth and death dates given. Readers seeking fuller biographical information on the persons listed should consult standard biographical dictionaries and listings, most particularly the Dictionary of National Biography and the Dictionary of Scientific Biography. For a list of sources of biographical information on figures in nineteenth-century English natural history readers should consult the Calendar to the Darwin correspondence.

The second, and largest, category of footnotes pertains to the published literature. Where possible the identical edition of a work to that used by Darwin has been cited. Frequently Darwin's own copy of a work has provided the citation. Where Darwin's marginal comments on the relevant passage in his own copy of the work were particularly apposite, they have been included in the note. However, marginalia can rarely be dated, and the reader should not infer that they are necessarily contemporaneous with the notebook entries.27 In some notes, cross-references are made to various of Darwin's publications, or to his manuscripts, but no attempt has been made to provide an exhaustive set of cross-references between the manuscripts published here and Darwin's other writings. Also, the notes do not refer to what has become a large secondary literature on Darwin and his contemporaries, since to have done so would have greatly lengthened the volume.28

Titles of journal articles are cited in full in the bibliography and journal titles are abbreviated according to the standard specified in the List of Serial Publications in the British Museum (Natural History) Library (London, 1968). Book titles have been reduced in length; those seeking full titles and complete publication data may consult standard library catalogues. In addition, a number of works have been given short titles, by which they are cited throughout the volume. Books and articles marked with asterisks in the bibliography are those that are part of Darwin's personal library. Darwin's library is presently divided between the Cambridge University Library and Down House, his home in Kent. While there is no published list of Darwin's reprint collection—an unpublished list by P. J. Vorzimmer (Ph.D. thesis 1963, vol. 2) can be found in the Cambridge University Library—there does exist a published catalogue of his library: H. W. Rutherford, Catalogue of the Library of Charles Darwin now in the Botany School, Cambridge (1908).

[page] 16

Following each entry in the biographical index and bibliography, there is an index of mentions listing every location in the manuscripts where that reference appears. Thus following the biographical entry for Charles Lyell is a list of all those places in the notebooks where he is mentioned in a guise other than that of author. References in the notebooks to specific publications by Lyell are listed under the appropriate bibliographical entry.

To aid the scholar a colour microfilm of the majority of the manuscripts in this volume has been prepared under the supervision of Peter J. Gautrey. Manuscripts included are the Red Notebook, Notebooks A, B, C, D, E, M, N, the Torn Apart Notebook and Questions & Experiments. In order to keep the microfilm to one roll, the other manuscripts in this volume were omitted, the Glen Roy Notebook being too faint for filming in any case. The microfilm, published jointly by Cambridge University Library and the British Museum (Natural History), is available for purchase from the Museum and from Cornell University Press. Also for the scholar, a concordance to the manuscripts in this volume is being prepared under the supervision of Paul H. Barrett and Donald J. Weinshank and will be published by Cornell University Press.

27 A catalogue of Darwin's marginalia is presently being prepared for publication by Mario DiGrigorio and Nick Gil.

28 On the literature see the bibliography produced with the assistance of Malcolm J. Kottler in Kohn 1985.

[page] 17

Red Notebook

Transcribed and edited by SANDRA HERBERT

The Red Notebook1 forms part of the collection of Darwin manuscripts at Down House in Kent, Darwin's home from 1842 to his death, and, since 1929, a museum in his honour. The notebook (164 100 mm) is bound in red leather, blind embossed on both sides, and has a metal clasp. The front and back covers bear the initials 'R.N.' on rectangular pieces of white paper, and on the back cover is written 'Range of Sharks', referring to an entry within the notebook. There is also written in large letters across the back of the notebook 'Nothing For any Purpose'. All the inscriptions are in brown ink in Darwin's hand, with the exception of a circled '16' in the hand of Nora Barlow on the inside front cover and the notation '1.2', made by an unknown cataloguer, on the inside back cover.

There are 90 leaves of a green-edged paper, chain lined, feintly ruled, and bearing a 'T WARREN 1830' watermark. Seventy-eight pages were wholly or partly excised from the notebook of which all but eight have been wholly or partly recovered. The notebook divides into two parts: the first to page 113 is written in pencil across the page parallel to the spine; the second is written in both ink and pencil across the page perpendicular to the spine. The only trace of grey ink occurs on the inside front cover.

The first part of the notebook yields a perfect progression of place-names corresponding to points visited by the Beagle from late May to the end of September 1836.2 The second part, from page 113 onwards, is more difficult to date, and, indeed was once thought to have been produced during the voyage, a significant dating given its transmutationist passages.3 However, scholars now agree that the second portion of the notebook postdates the voyage.4 While an exact date cannot be set, this second part opens with comments that suggest a January 1837 dating. On 2 January Darwin was in London dining with the geologist Charles Lyell; the next day work was being done at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons on the fossil bones Darwin had collected in South America.5 Presumably Darwin assisted in this work, which would explain his query on page 113 regarding Richard Owen, comparative anatomist at the Hunterian Museum: 'Should Mr Owen consider bones washed about much at Coll. of. Surgeon's?' On the same page Darwin noted, 'With discussion of camel urge S. Africa productions.—' The 'camel' represents Owen's initial judgement of a fossil he would later name Macrauchenia patachonica6 Owen's earliest known written statement on the affinities of the fossil occurs in a letter to Lyell of 23 January 1837, and presumably Darwin knew of Owen's judgement before this time.7 Thus January 1837, and earlier rather than later in the month, would appear a likely date for the opening of the second part of the notebook.

1 For Darwin's use of the title 'Red Note Book' see DAR 29.3:9V.

2 S. Herbert 1980:6.

3 Barlow 1945:260-64; Barlow 1963:277 dates RN127-53 to before April 1836.

4 S. Herbert 1968:78,1974:246-49,1980:6-12; Kohn 1980:67 n. 3; Sulloway 1982:370-86.

5 Correspondence 1:532; also Sloan 1986:422 n. 98 citing two diary entries by William Clift at the RCS, the first noting a Darwin communication of 30 December 1836 asking the College not to open his parcels shipped to the College from Cambridge until his return to London and the second, on 3 January 1837, recording the commencement of the washing of Darwin's fossils at the College.

6 Darwin to Owen [28 December 1837], Correspondence 2:66.

7 Owen to Lyell, 23 January 1837 in L. G. Wilson 1972:436-37. Against the dating offered in Sulloway 1982:355 see Correspondence 2:4.

[page] 18

Darwin filled the notebook sometime from late May to mid-June 1837. His reference to petrified wood on page 178 is tied to its examination by Robert Brown reported in a letter of 18 May.8 On the same page the reference beginning 'Puncture one animal' also occurs in a letter written sometime between late May and mid June.9 The correlation between notebook references and the Journal of Researches also supports an early June dating.10

The year in which the Red Notebook was kept was one of transition. The notebook reflects that transition, and itself served partly as an instrument of adjustment, for Darwin used it to assist future publication. Scattered throughout the first part of the notebook are reminders to himself: 'Introduce part of the above in Patagonian paper' (p. 49), 'In Rio paper . . .' (p. 65), 'In my Cleavage paper . . . ' (p. 101), and so on. Entries in the Red Notebook were also directed to another publishing project, the work commonly known as the Journal of Researches. From about 7 March to 25 June 1837 Darwin converted his diary from the voyage into the draft of his Journal and used the Red Notebook as a storehouse for references.11

Most entries in the notebook are geological and of these the majority describe specific land formations and rock types. However, nearly as many entries pertain to the elevation and subsidence of the earth's crust, the attendant issue of the form of the earth, and such patterns of disturbance in the earth's crust as were indicated by the occurrence of earthquakes and the presence of volcanoes and mountain chains. Contemplating the prospects for geological theory in understanding the vertical motion of the earth's crust, Darwin speculated that the 'Geology of whole world will turn out simple.—' (p. 72) In addition to crustal motion, Darwin also made notes on such topics as the distribution of metallic veins, the preservation of fossils, erratic blocks, and life at the bottom of the sea.

However compelling the geology, it is Darwin's remarks on the species question that have drawn the greatest attention to the Red Notebook. The entries, on pages 127-133, form Darwin's first thoughts on transmutation, the notion, as he put it on page 130, that 'one species does change into another'. These entries record his adoption of the transmutationist hypothesis in 'about' March 1837, a date he set down later in his 'Journal'.12 This date coincides with Darwin's receipt of the views of London zoologists regarding key specimens from his collection.13 Particularly important was John Gould's description of the new species of Galapagos mockingbirds on 28 February 1837 at the Zoological Society of London; Darwin was impressed to learn the mockingbirds were not 'only varieties' as he had once thought, but, in Gould's opinion, good species. Only slightly less important—since Darwin had presumed it to be a new species on his own—was Gould's work on the smaller rhea, described at the

8 Correspondence 2:17-18.

9 Charles to Caroline Darwin, 19 May-17 June 1837, Correspondence 2:19-21. This letter has been redated from earlier treatments (Calendar:30) [#360], Sulloway 1982:384-85) on the basis of a newly discovered letter (Correspondence 2:23-24). Since the 'Thursday' referred to in the letter is probably 1 or 8 June, the date of the letter would then be a few days prior to either of these dates.

10 The last third of JR was written between 18 May and 25 June (note 11 and Correspondence 2:18). Compare JR:52\-22 with references towards the end of the notebook.

11 On 6 March 1837 Darwin departed Cambridge, where he had remained until he finished looking over his geological specimens, to reside in London. On 12 March he was already 'hard at work' on the book, and by 26 June he could allow himself a holiday and a trip to Shrewsbury 'as I had finished my journal'. (Correspondence 2:430, U, 29)

12 Correspondence 2:431; on dating RN: 127-33 see S. Herbert 1980:10-11 and Sulloway 1982:370-86. The entries beginning on RN127 were probably written in the second half of March, after Darwin had conferred with the London specialists. See also Sydney Smith 1960.

13 S. Herbert 1974:241-45, 1980:11-12, and Sulloway 1982:356-69. For current identifications of birds named in RN see David Snow's notes in S. Herbert 1980.

[page] 19

14 March 1837 meeting of the Zoological Society; the two rheas figure prominently in the entries on pages 127 and 130.14

Darwin's remarks on species in the notebook are directed towards three general questions: geographical distribution, the relation between the spatial and temporal distribution of species, and generation. The central theoretical notion to emerge with respect to geographical distribution is that of the 'representation' of species (p. 130), or what Darwin referred to in his autobiography as 'the manner in which closely allied animals replace one another in proceeding southwards over the [South American] Continent . . .'.15 From this notion Darwin drew the tentative conclusion that such representative species as the two South American rheas had descended from a common parent (p. 153). Darwin's second, and critical, point on species is the comparison he drew between the distribution of species through space and time. The passage, simplified by omission of one example, reads, 'The same kind of relation that common ostrich bears to (Petisse . . .): extinct Guanaco to recent: in former case position, in latter time' (p. 130). The first relation—the 'common ostrich' being the common rhea, the 'Petisse' the lesser or Darwin's rhea (note RN127-3)—was based on spatial succession, the geographical ranges of the two birds being contiguous. The second relation, between what Darwin termed the 'extinct Guanaco' (Macrauchenia) and 'recent' guanaco, involved temporal succession, though the exact nature of the succession is not specified in the text.16 The common element binding the two relations derives from the fact that both involved the replacement of one species by an allied species. Moreover, in context it is clear that replacement implied transmutation, for immediately upon asserting an analogy between spatial and temporal succession, Darwin referred to species changing. In doing so he also asserted that allied species do not grade into each other but 'inosculate' (p. 130).17

A third topic taken up in the notebook with general relevance for the species question was generation or reproduction. In the notebook Darwin dealt briefly with individuation in the zoophytes. The technical nature of zoophyte generation was not Darwin's primary concern; rather he wanted to see where zoophyte generation might fit in the general analogy he was drawing between the generation of species and the generation of individuals. Although the claim is not made explicitly in this notebook, Darwin presumed that the complementary relationship might also hold, that the birth of new species might be understood by analogy to the birth of individuals.18

14 Gould 1837f, Barlow 1963:262, and RN130-7; Gould 1837b, RN127-3. On Darwin's discussions with Gould see Sulloway 1982:362-69.

15 Barlow 1958:118.

16 Initially Richard Owen associated the fossil he named Macrauchenia with the order Ruminantia; before writing up the Zoology he placed it with the Pachydermata. (Presently it is in the order Litopterna.) Owen's association of the fossil with camels was based on the vertebrarterial canal in the neck being like that in camels while his later assignment of the fossil to the pachydermata depended in large part on the structure of the fossil's astragalus or ankle bone (Rachootin 1985). This analysis is borne out by evidence from Owen's research notebooks. Owen's notebook labelled '1836-1837' contains his description of the cervical vertebrae of the fossil while his notebook labelled '1838-1839' contains his description of its astragalus (Owen MSS, Notebooks 12 ['1836-1837'] and 13 ['1838-1839'], British Museum [Natural History] Archives). The dates on the covers of these notebooks are not in Owen's hand and are presumably approximate. Owen probably examined the fossil for the second time in the autumn of 1837, sometime before he named it in December (Correspondence 2:66). Darwin still thought of the fossil as primarily camelid in its affinities when he wrote A9 and JR:208-9, which he sent off to the publisher in August 1837 (Correspondence 2:33). For a photograph of Darwin's specimen of Macrauchenia see S. Herbert 1980.

17 MacLeay 1819-21; Sydney Smith 1968; Barlow 1967:62, n. 2; note B8-1. Also see A76 for an alternative reading.

18 On Darwin's invertebrate programme see Sloan 1985.

[page] 20

Once the Red Notebook was filled, Darwin reorganized his method of taking notes. Where the Red Notebook contained entries on all subjects of interest, subsequent notebooks were more restricted in content. On its own, however, the notebook provides a means not only for gauging the extent of Darwin's geological ambitions and for documenting his early belief in transmutation, but also for observing his passage from H.M.S. Beagle to the larger world of science.

[page 21]

RED NOTEBOOK FC-5e

FRONT

COVER R.N

inside up to 1° / July 1835. the excess of harbor = 180

cover See Daubisson both Volumes,1 and Molina Is' Vol2 & Lyell3

Sailed, 27th

(Friday, gale 29%

Friday

Thursday 29th gale

Lyell's Geology4

The living atoms having definite existence, those that have undergone the greatest

number of changes towards perfection (namely mammalia) must have a shorter

duration, than the more constant: This view supposes the simplest infusoria same

since commencement of world.—5

le-4e [not located]

5e La. billardiere mentions the floating marine confervae, is very common within E. Indian Archipelago, no minute description, calls it a Fucus. P «Vol I 287))1

P 379. Henslow Anglesea, nodules in Clay Slate, major axis 2.Vi ft.—singular structure of nodule, constitution «same as» of slate same.—longer axis in line of Cleavage, laminae fold round them;2 Quote this. Valparaiso Granitic nodules in Gneiss.

IFC 1°/] alternate reading T of.

up] feint '118' appears beneath, questionably Darwin's hand.

up . . . ISO] pencil, perpendicular to spine.

See . . . Vol] pencil, parallel to spine.

& Lyell] ink, parallel to spine.

Sailed . . . gale] pencil, parallel to spine.

27th] uncertain reading.

Lyell's Geology] ink, circled, written over 'Sailed, 27th', parallel to spine.

The living. . . world.—] ink, scored at left, perpendicular to spine, crossed ink. Crossing probably grey ink.

5 constitution . . . them;] scored left margin.

La.billardiere . . . 287] crossed ink.

IFC-1 Aubuisson de Voisins 1819.

IFC-2 Molina 1788-95,1.

IFC-3 Charles Lyell.

IFC-4 Lyell 1830-33 or, possibly, a later edition of the same work or Lyell 1838a. The dates preceding this entry probably pertain to the departure of H.M.S. Beagle from England. The Beagle sailed from England Tuesday 27 December 1831. The ship encountered heavy seas, caused by gales elsewhere, on Thursday 29 December 1831. For Darwin's description of the ship's departure see his letter to his father of 8 February-1 March 1832 in Correspondence 1:201 and his own Diary: 18-19.

IFC-5 The probable stimulus for this passage was Ehrenberg 1837c, 1:555-76.

5-1 Labillardiere 1800, 1:287, Je revis le fucus que j'avois auparavant rencontre tout pres de la Nouvelle-Guinee; il ressemble a de l'etoupe tres-fine coupee par petis morceaux longs d'environ trois centimetres: ce sont des filamens aussi fins que des cheveux. On les voyoit souvent reunis en faisceaux, et si nombreux qu'ils ternissoient l'eau de la rade.'

5-2 Henslow 1821-22:379,'The major axis of some of the larger nodules is two feet and a half, and the minor one foot and a half; and the conical structure extends to the depth of three or four inches. The direction of the longer axis is placed parallel to the schistose laminae, which pass round the nodules.'Darwin scored this passage.

[page] RED NOTEBOOK 6e-8e

6e Epidote seems commonly to occur where rocks have undergone action of heat, it is so found in Anglesea, amongst the varying & dubious granites.—Wide limits of this mineral in Australia. Fitton's appendix1

Would Slate. & unstratified rocks show any difference in facility of conducting Electricity? Would minute particles have a tendency to change their position?

7e Carbonate of Lime disseminated through the great Plas Newydd dike.—Mem tres Montes. ((Henslow Anglesea))1

great variety in nature of a dike.—Mem. at Chonos & Concepcion. P. 4172

Veins of quartz exceedingly rare Mem C. [Cape] Turn P. 434 & 4193

As Limestone passes into schist scales of chlorites—Mem. Maldonado P 3754 Much Chlorite in some of the dikes.—P 432.5 as in Andes.

8e In Dampier's voyage there is a mine of metereology with respect to the discussion of winds & storms:1—«in Volney's travels also»2

Dampier's last voyage to New Holland P 127.—Caught a shark 11 ft long.3 "Its maw was like a leathern sack, very thick & so tough that a sharp knife could not cut it: in which we found the Head & Boans of a Hippotomus; the hairy lips of which were still sound and not petrified, and the

6 Would ... position] crossed pencil.

8 page crossed.

6-1 Fitton in King 1827, 2:585, 'The Epidote of Port Warrender and Careening Bay, affords an additional proof of the general distribution of that mineral; which though perhaps it may not constitute large masses, seems to be of more frequent occurrence as a component of rocks than has hitherto been supposed.' 7-1 Henslow 1821-22:403, 'Carbonate of lime is very generally disseminated through every part [of the Plas-Newydd dike].'

7-2 Henslow 1821-22:417, 'The most interesting phenomena exhibited by this dyke, are the various changes which it assumes in its mineral character.' 7-3 Henslow 1821-22:434, 'Through this dyke there run several veins of quartz, which also abound in the surrounding rock, a fact which I do not recollect witnessing in any other dyke in Anglesea.' Also p. 419: 'At its [the dyke's] Northern termination the trap has been removed by the continued action of the sea, and its original walls, composed of quartz rock, form a small bay about eighty feet wide.' In his copy Darwin commented on p. 434 'At C. Turn Quartz broad vein traversed Slate & greenstone' and on p. 419 'just what occurs in the Magdalen Channel at C: Turn T del Fuego'.

7-4 Henslow 1821-22:375,'As the limestone passes into the schist [at Gwalchmai], it assumes a fissile character, and scales of chlorite are dispersed over the natural fractures.' Next to this passage in his copy Darwin reminded himself to 'Mem: Maldonado Limestone . . .'.

7-5 Henslow 1821-22:432, 'The whole [mass of trap] assumes a greenish tinge, but the colouring substance does not appear to be of a very crystalline nature, and is probably chlorite.' In his copy of the work Darwin scored this passage, adding a comment—now partly cropped— that ends 'of Chili'.

8-1 Dampier 1698-1703, 2, pt 3.

8-2 Volney 1787b, 1, chap. 20 the section entitled 'Des vents', and chap. 21 entitled 'Considerations sur les phenomenes des vents, des nuages, des pluies, des brouillards et du tonnerre'.

8-3 Dampier 1698-1703, 3:125. Exact edition unknown.

[page] RED NOTEBOOK 9-13e

9 jaw was also firm, out of which we pluckt a great many teeth, 2 of them, 8 inches long, & as big as a mans thumb, the rest not above half so long; The maw was full of jelly which stank extreamly."—This shark was caught in Shark's Bay. Lat 250.1 The nearest of the E. Indian Islands, namely Java is 1000 miles distant! Where are Hippotami found in that Archipelago? Such have never been observed in Australia

10 Dampier also repeatedly talks about the immense quantities of Cuttle fish bones floating on the surface of the ocean, before arriving at the Abrolhos shoals.-(^—l