THE

FOSSIL REMAINS

OF THE

ANIMAL KINGDOM,

BY

EDWARD PIDGEON, ESQ.

LONDON:

WHITTAKER, TREACHER, & Co.

AVE-MARIA-LANE.

MDCCCXXX.

LONDON:

Printed by WILLIAM CLOWES,

Stamford Street.

LIST OF PLATES.

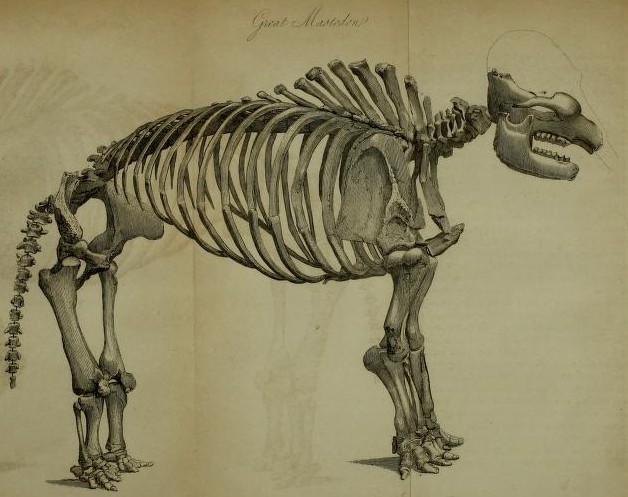

| GREAT Mastodon | to face page 66 |

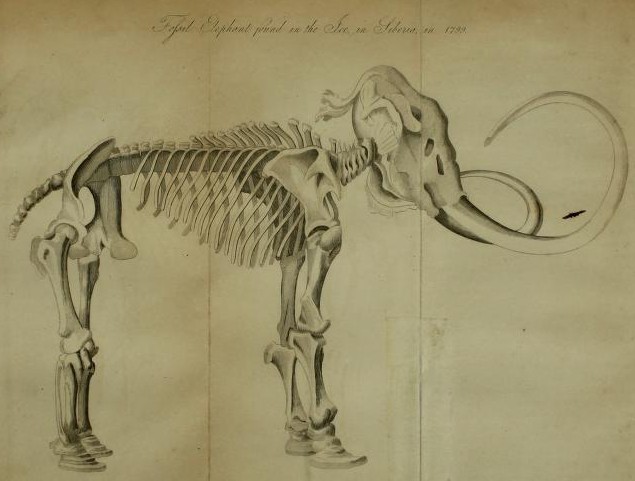

| Fossil Elephant, found in the ice in Siberia | 52 |

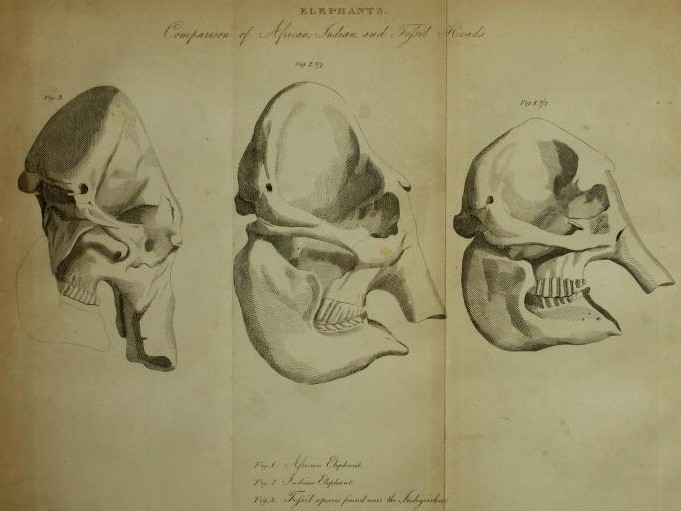

| Elephants, comparison of heads | 57 |

| Supposed outlines of extinct species | 105 |

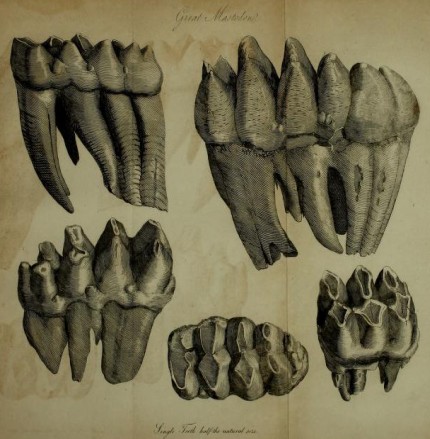

| Great Mastodon, jaws of | 70 |

| Great Mastodon, single teeth of | 69 |

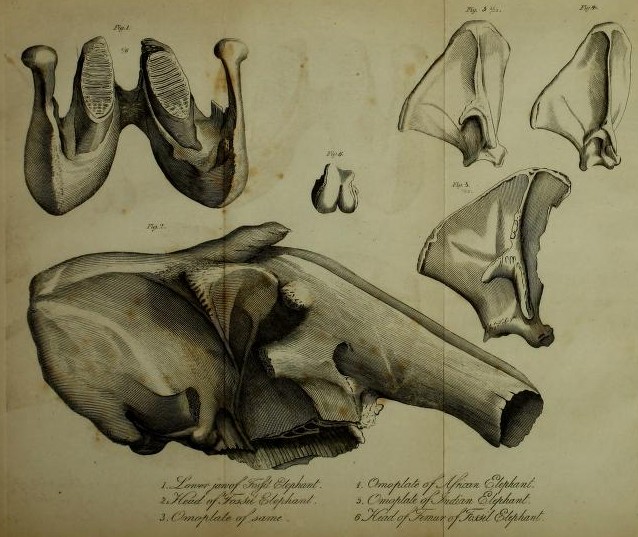

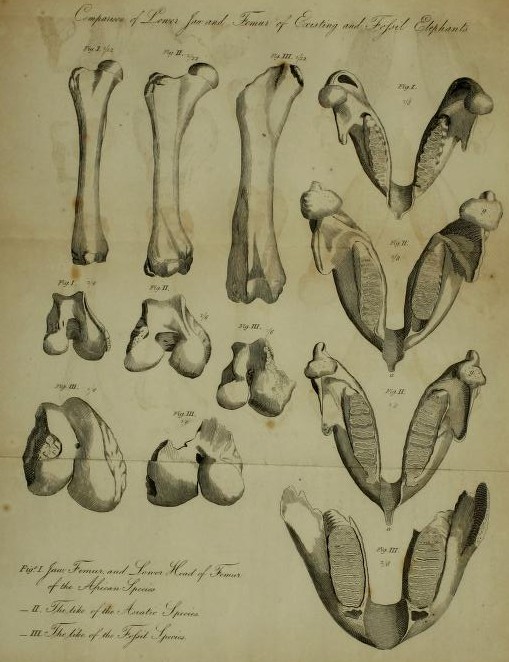

| Comparison of lower jaw and femur of existing and fossil Elephants | 58 |

| Megatherium | 132 |

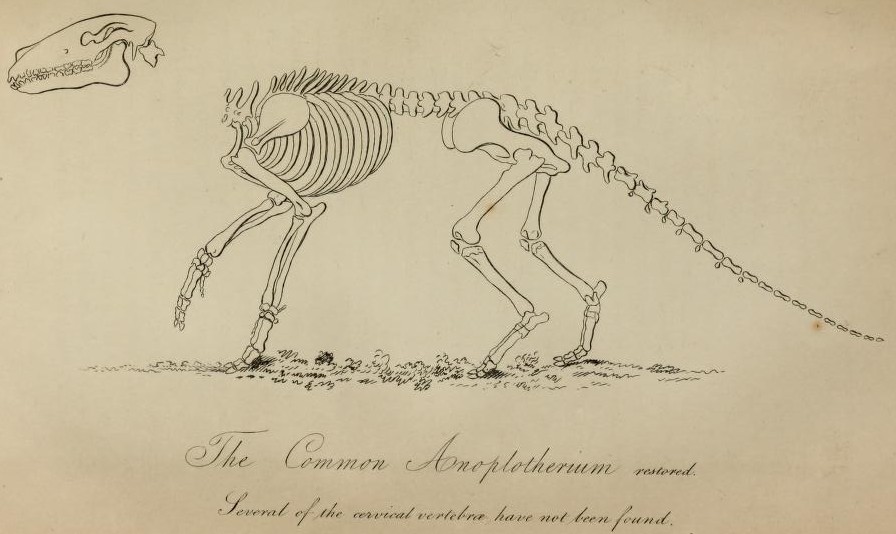

| Common Anoplotherium restored | 110 |

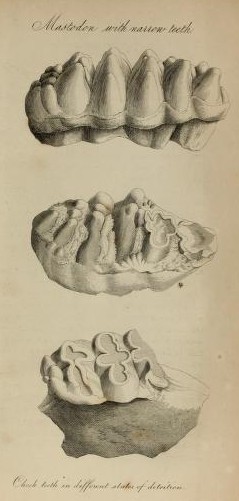

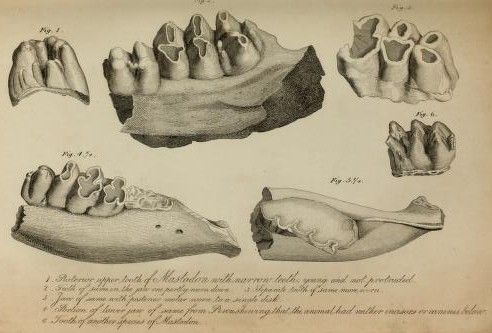

| Mastodon with narrow teeth | 74 |

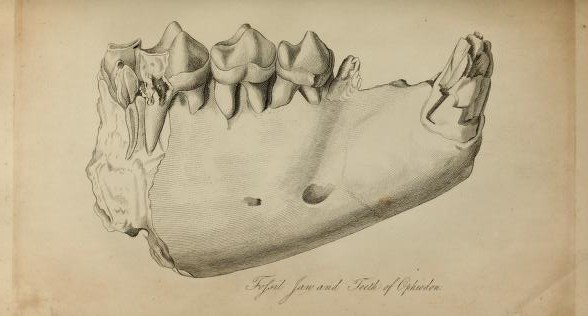

| Fossil jaw and teeth of Lophiodon | 94 |

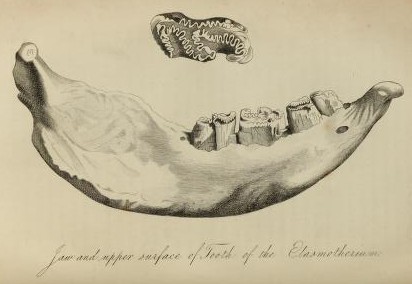

| Jaw and upper surface of tooth of the Elasmotherium | 89 |

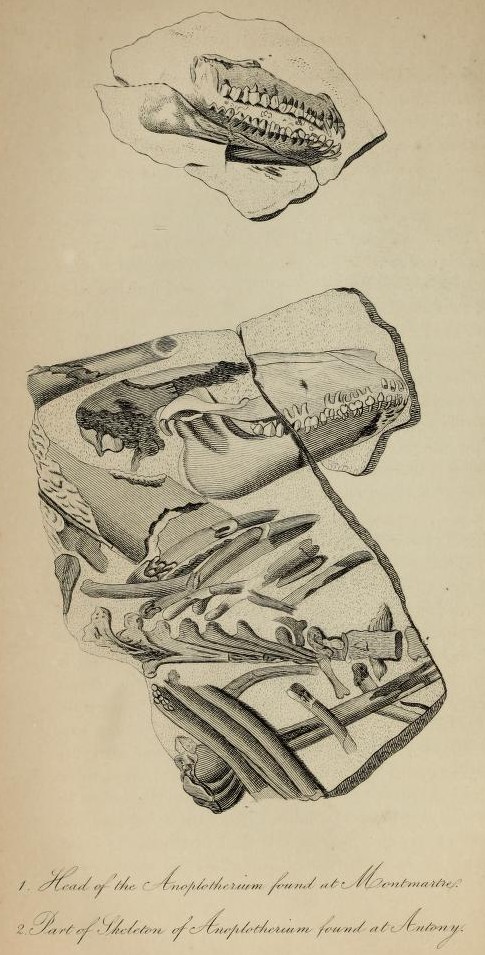

| Head and part of skeleton of Anoplotherium | 109 |

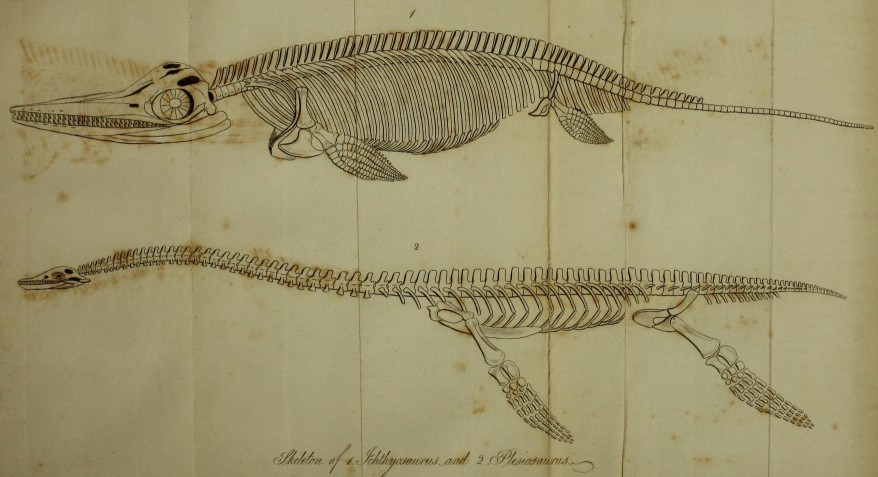

| Skeleton of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus | 343 |

| Lower jaw of fossil Elephant, with omoplate and femur of Elephant | 57 |

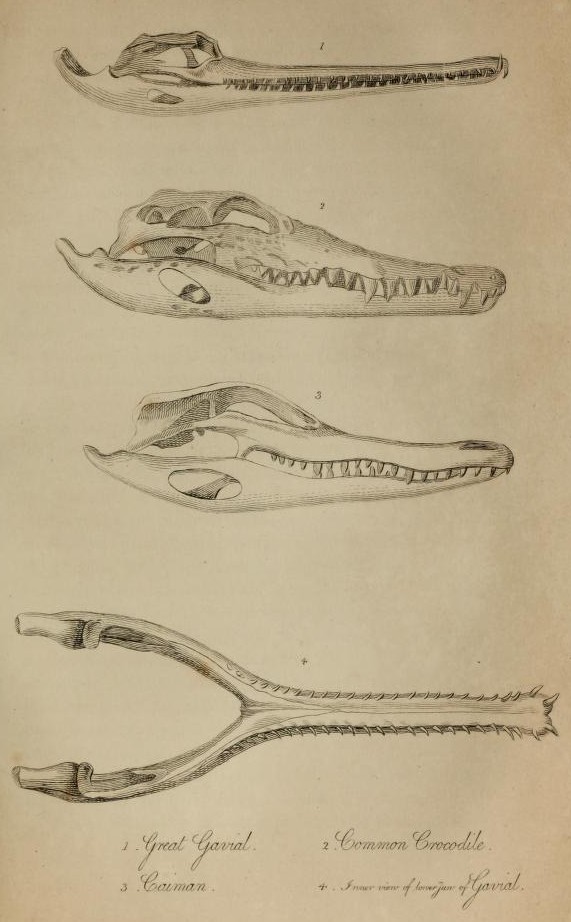

| Great Gavial, Caiman, common Crocodile, and jaw of Gavial | 200 |

| Fragment of jaw of Megalosaurus, and single tooth of same | 318 |

| Posterior upper Tooth of Mastodon, with narrow teeth, young and not protruded, &c. | 74 |

| Fossil Hyæna from Kirkdale Cave, &c. | 124 |

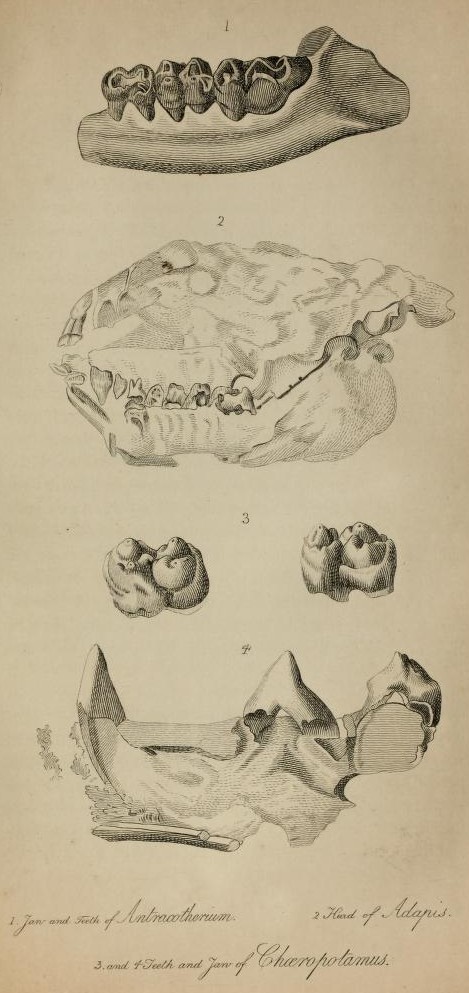

| Jaw, &c., of Antracotherium, head of Adapis, and teeth of Chæropotamus | 112 |

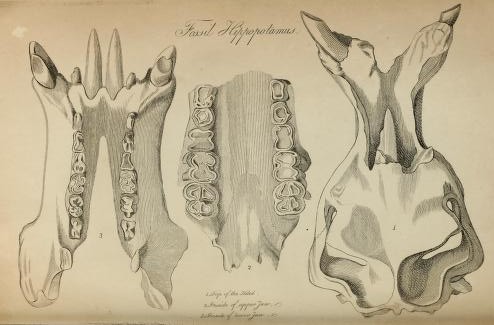

| Fossil Hippopotamus | 77 |

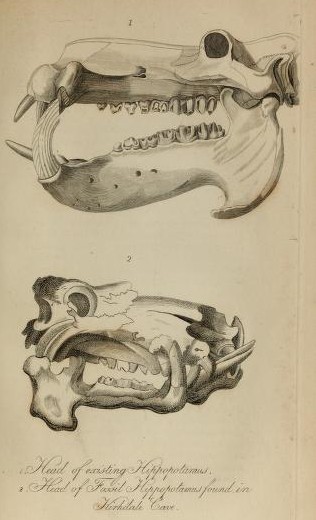

| Head and upper jaw of existing Hippopotamus, &c. | ibid. |

| Part of Crocodilus priscus of Soemmering | 233 |

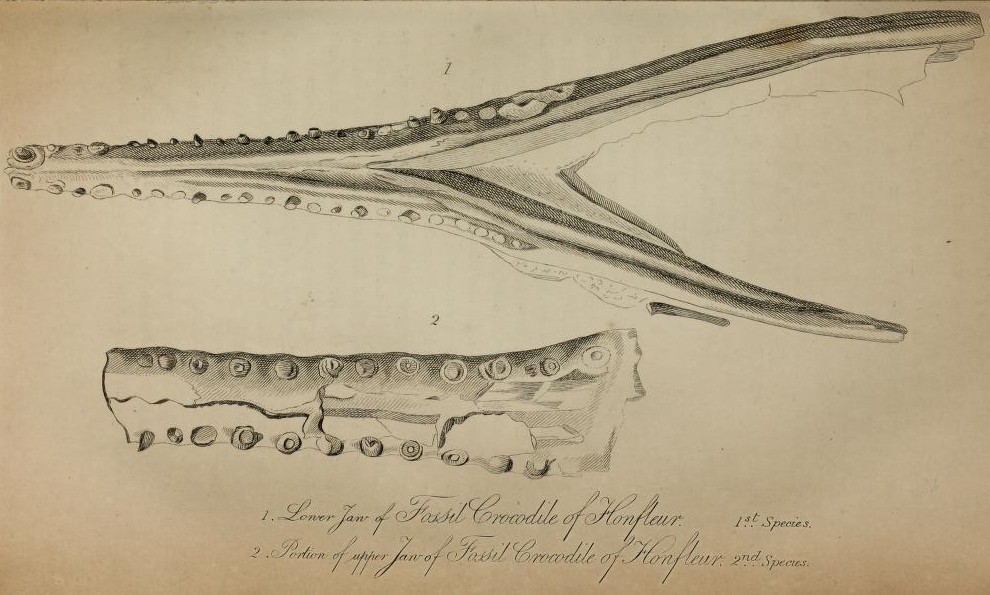

| Lower jaw of fossil Crocodile of Honfleur, &c. | 242 |

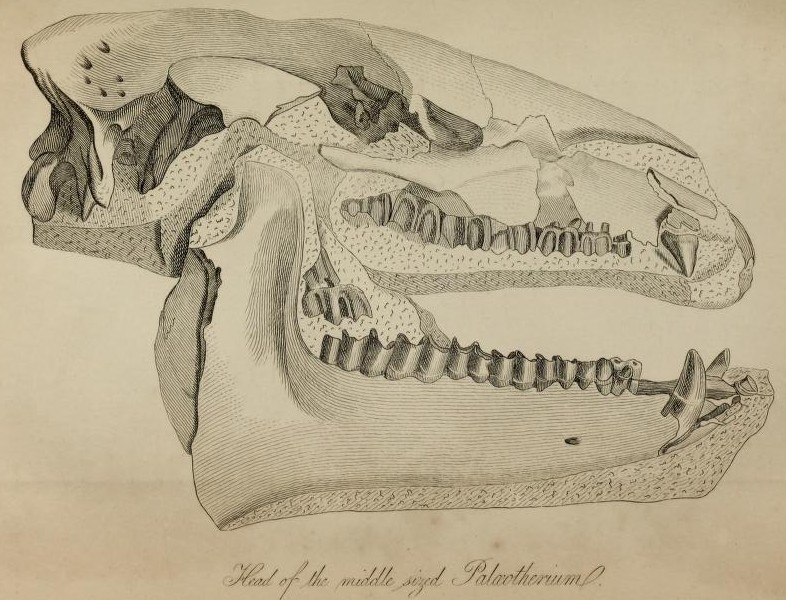

| Head of middle-sized Palæotherium | 106 |

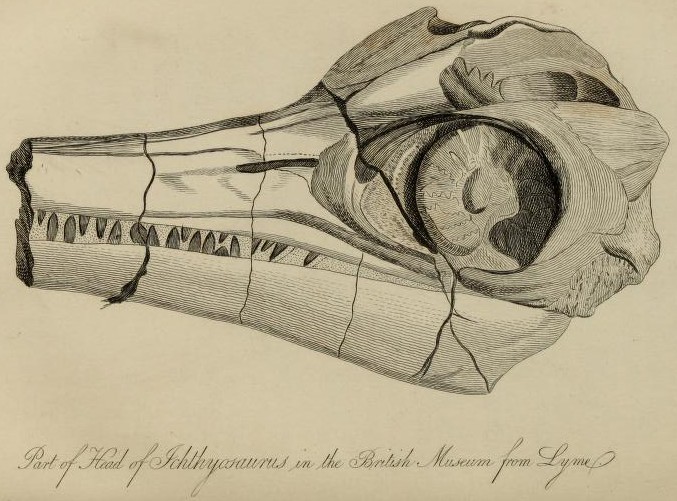

| Part of head of Ichthyosaurus in the British Museum, from Lyme | 357 |

| Head of existing Hippopotamus and of fossil Hippopotamus, found in Kirkdale Cave | 78 |

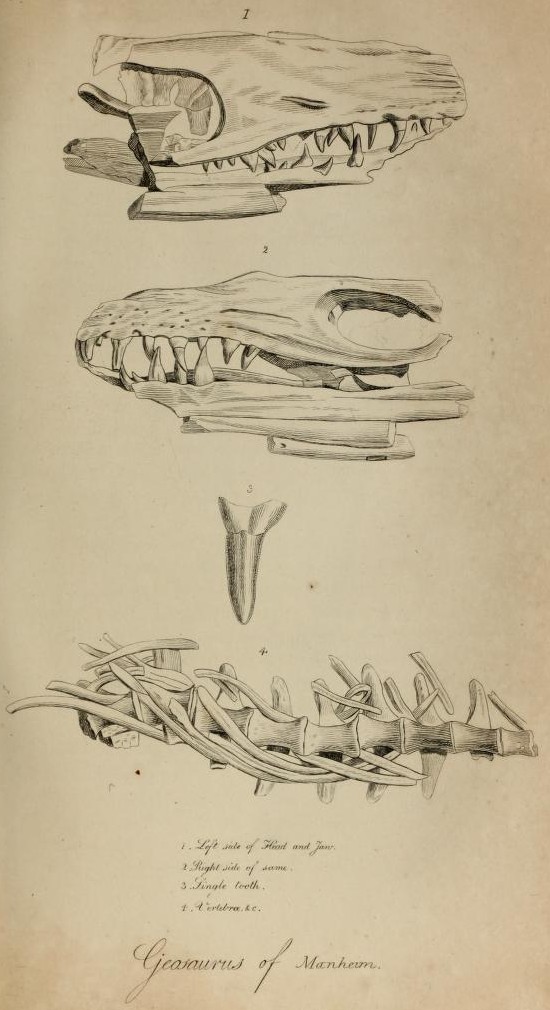

| Geosaurus of Manheim | 316 |

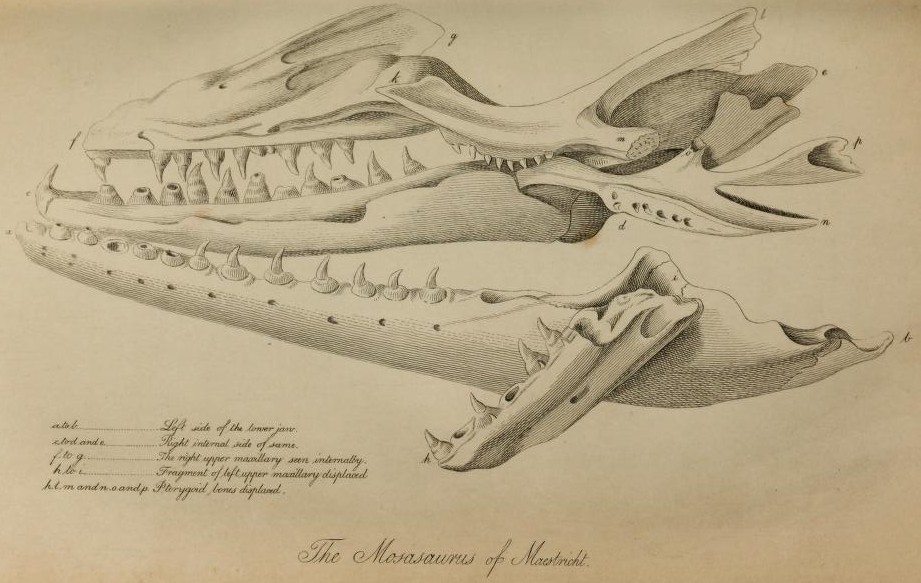

| Mosasaurus of Maestricht | ibid. |

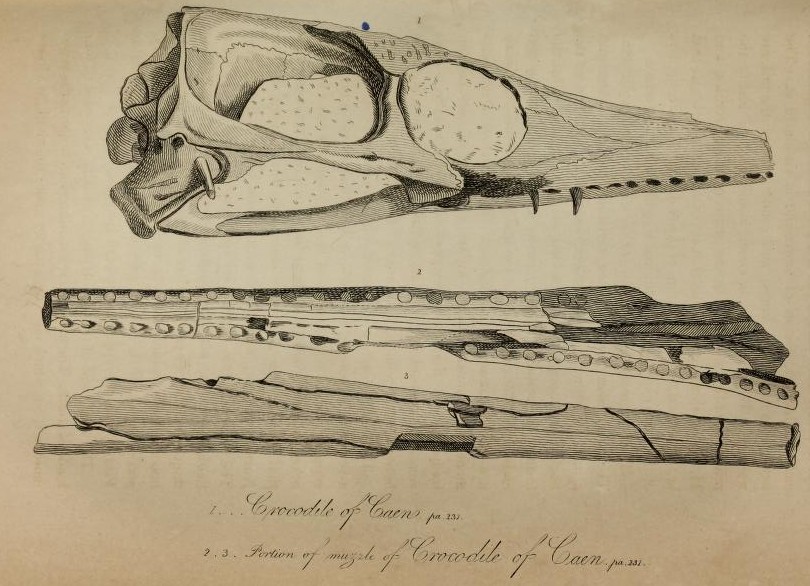

| Crocodile of Caen, and portion of muzzle of the same | 234 |

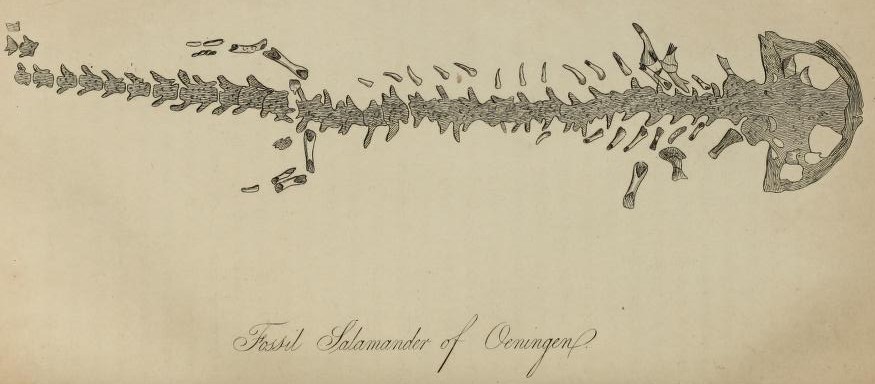

| Fossil Salamander of Œningen | 377 |

| Plesiosaurus, from Lyme | 365 |

| Pterodactylus longirostris, from Pappenheim | 326 |

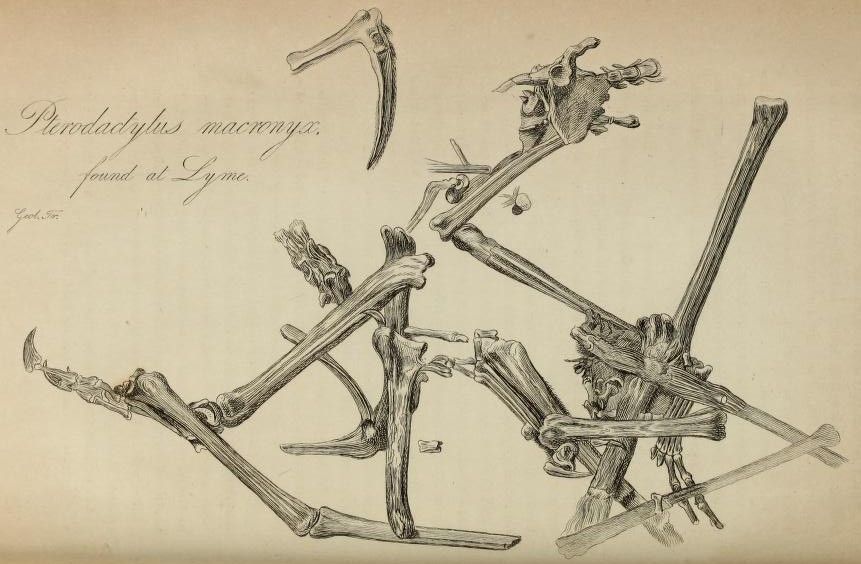

| Pterodactylus macronyx, found at Lyme | 331 |

| Ichthyosaurus tenuirostris | to face page 364 |

| Dapedium politum, from Lyme | 390 |

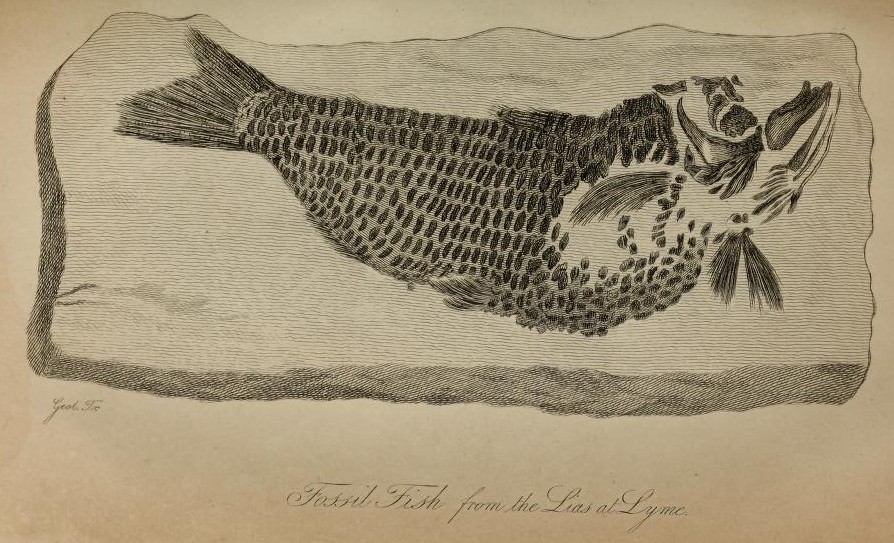

| Fossil Fish, from the lias, at Lyme | ibid. |

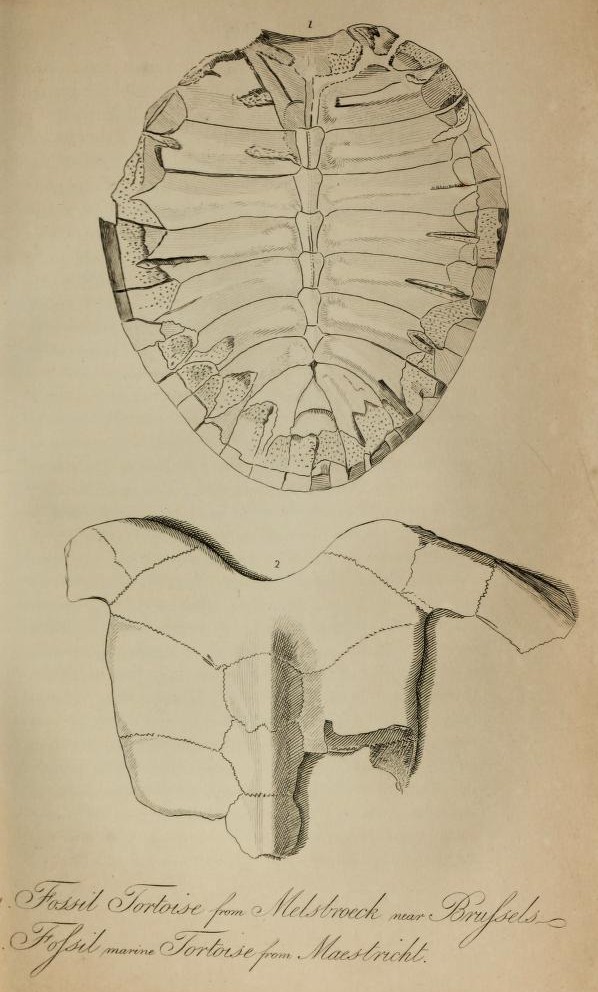

| Fossil Tortoise, from Melsbroeck, near Brussels | 276 |

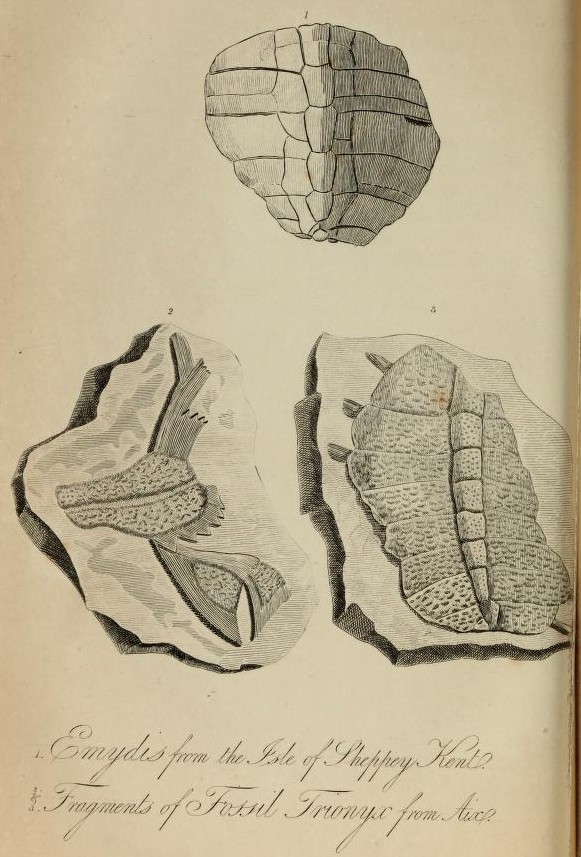

| Emys, from the Isle of Sheppey, Kent | 279 |

| Fossil Crab, found in the green sand at Lyme | 492 |

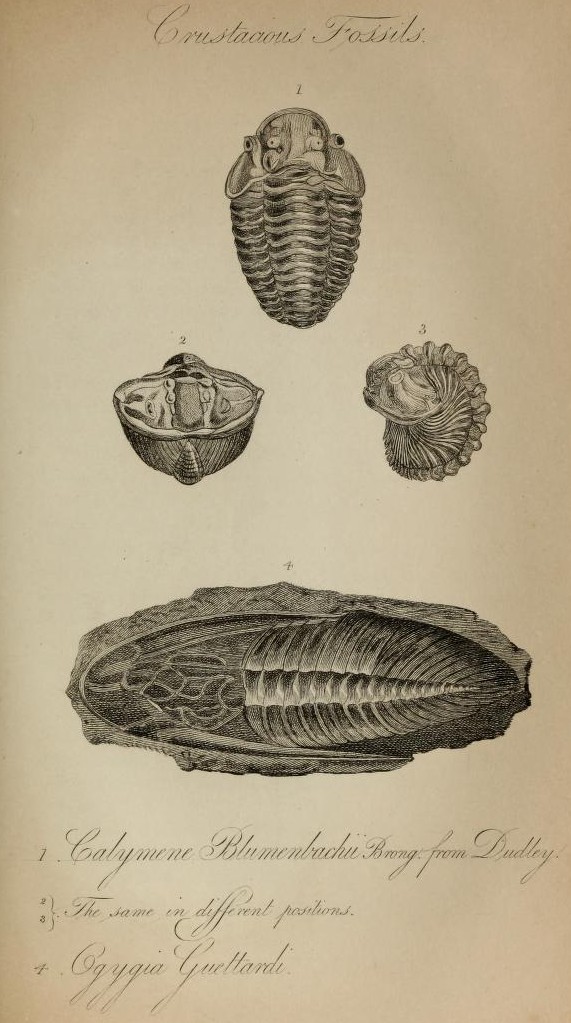

| Crustaceous Fossils, &c. | ibid. |

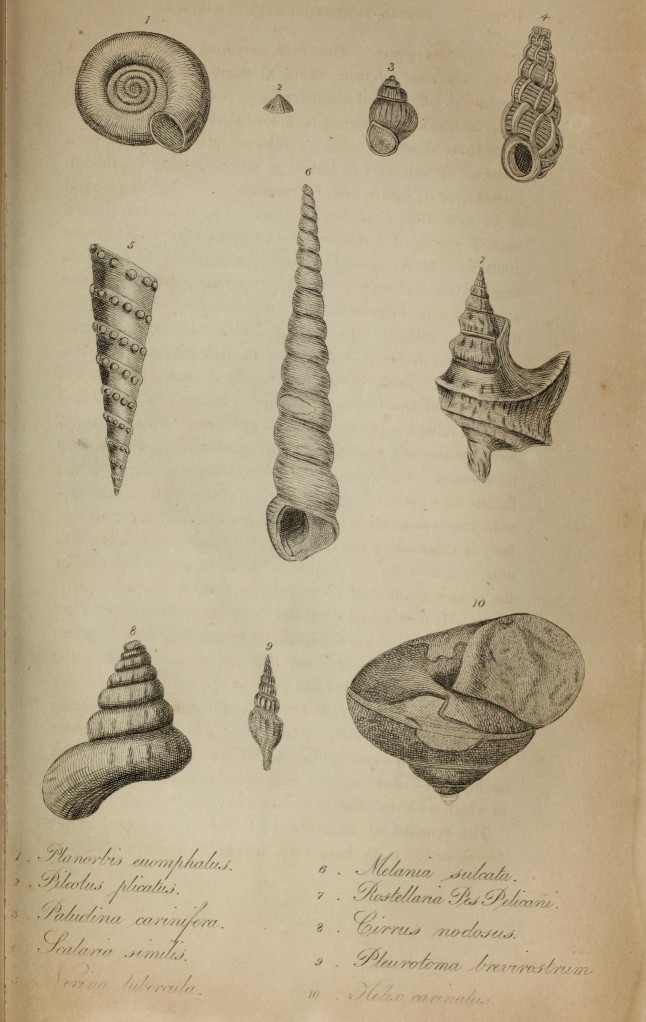

| Fossil Shells—Planorbis euomphalus, &c. | 490 |

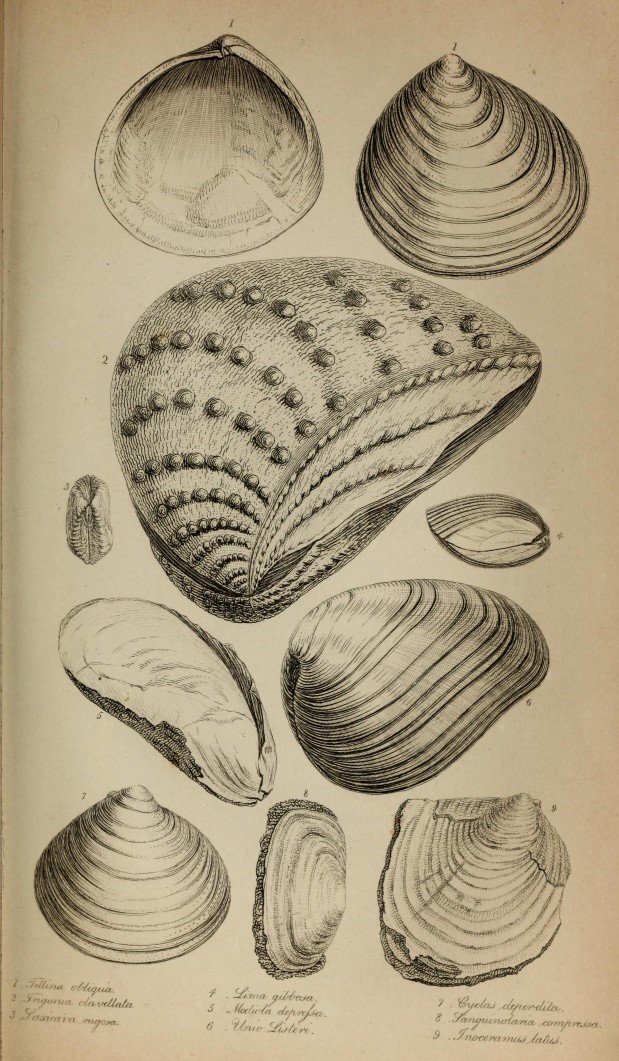

| Tellina obliqua, &c. | ibid. |

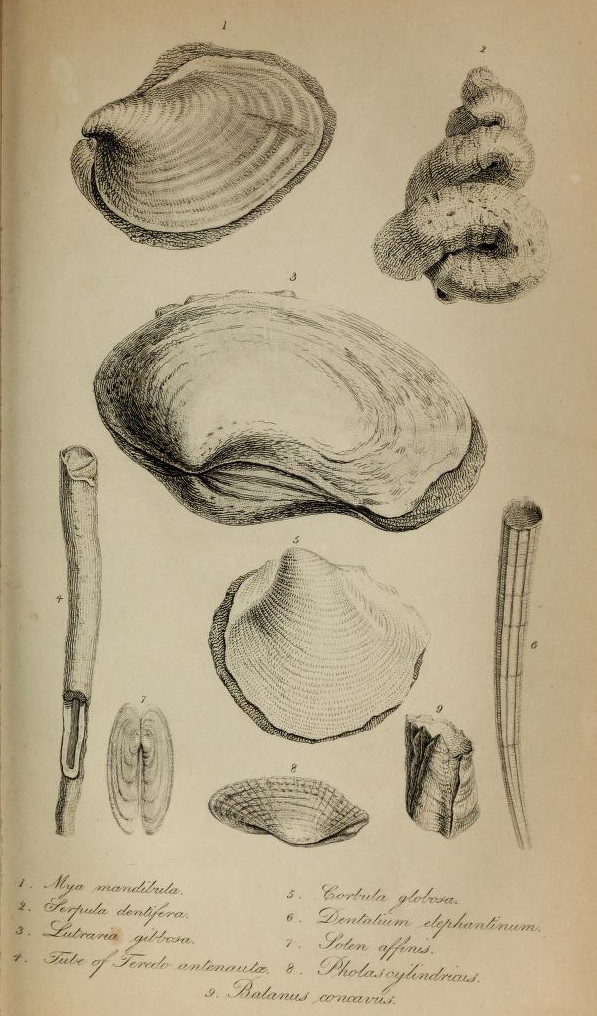

| Mya mandibula, &c. | ibid. |

| Emarginula crassa, &c. | ibid. |

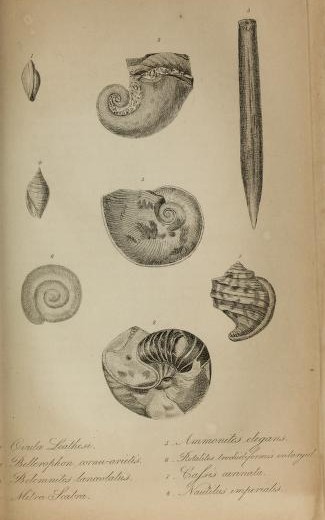

| Ovula Leathesi, &c. | ibid. |

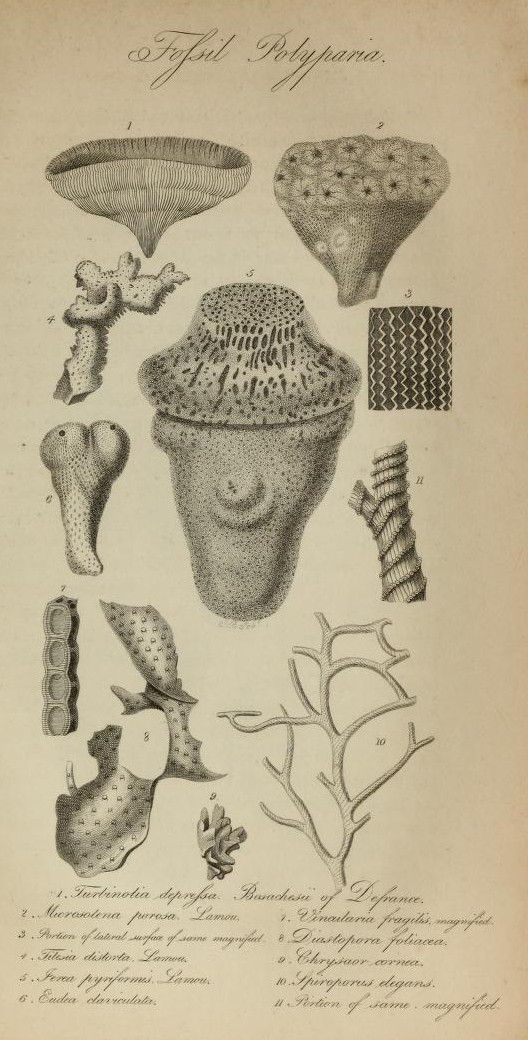

| Fossil Polyparia—Turbinolia depressa, &c. | 504 |

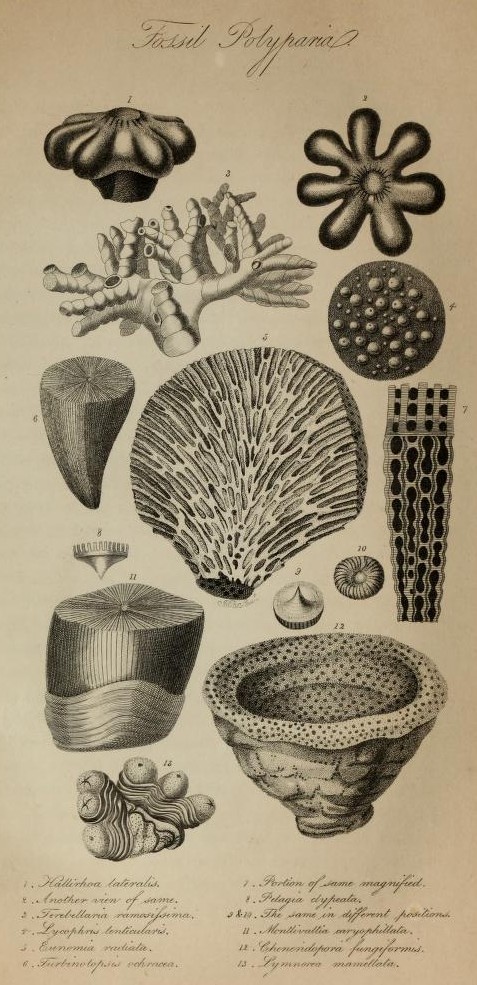

| Hallirhoe lateralis, &c. | ibid. |

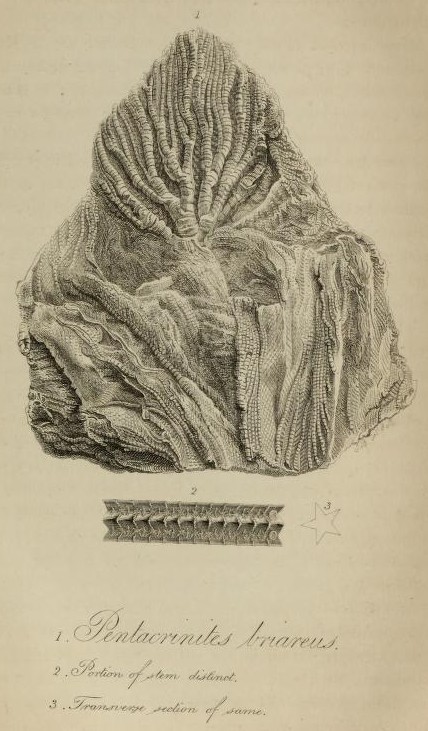

| Pentacrinites briareus | 510 |

ERRATA IN THE PLATES.

For Ophiodon, read Lophiodon.

For Emydis, read Emys.

For Crustacious Fossils, read Crustaceous.

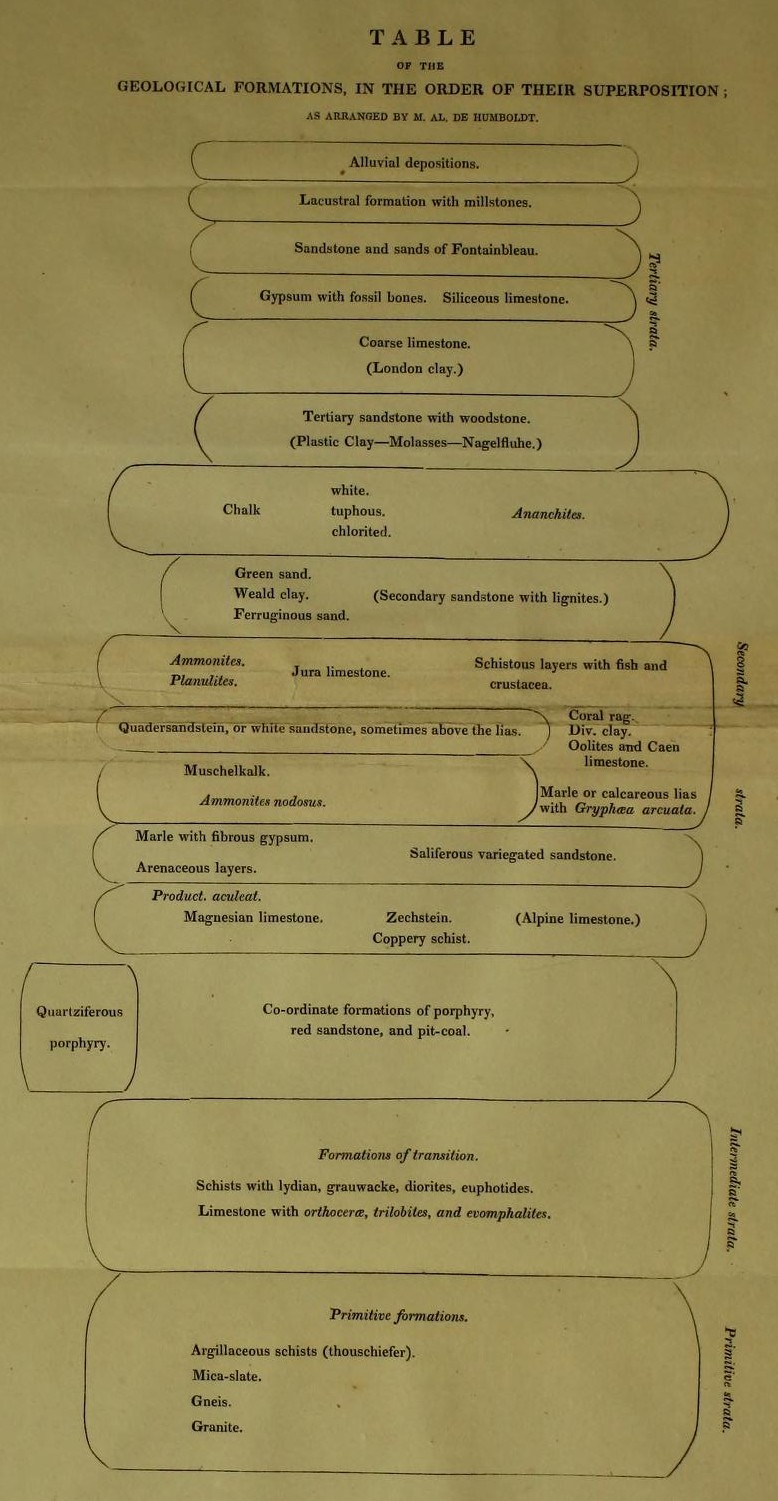

TABLE

OF THE

GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS, IN THE ORDER OF THEIR SUPERPOSITION,

AS ARRANGED BY M. AL. DE HUMBOLDT,

THE FOSSIL REMAINS OF VERTEBRATED ANIMALS.

BY EDWARD PIDGEON, ESQ.

FOSSIL MAMMALIA.

RESEARCHES into Fossil Osteology are comparatively of very recent date, and almost all that they possess of a scientific form is owing to the exertions of the illustrious naturalist whose steps we have thus far pursued, though at a very humble distance. It was reserved for him to ascertain, for the most part, the genera and species to which the osseous remains of terrestrial animals, so abundantly discovered in the superficial strata of this planet, are attached. Prepared for the execution of this Herculean task by the profoundest study of comparative anatomy, and the natural history of existing, he was enabled to characterize with precision the fragments of extinct species, to reconstruct those ancient animals, and present to our astonished view the wonders of former creations. More certain data have been thus obtained for the revolutions and duration of the globe; geology has ceased to be a romance, and a solid basis is at length established for a rational theory of the earth. Our intention is to present to our readers, in an abridged form, the result of such researches, not only of the Baron, but of every other modern naturalist who has investigated the subject; but, before we enter on any specific details, it will be necessary to take a brief general view of the revolutions which the surface of this globe has undergone, and the consequent alterations which have taken place in animal existence. Our limits will

* B

prevent us from entering very deeply into the purely geological portion of the subject, or, in fact, of considering it at all, except in relation to its connection with the organic fossils.

An inspection of the various strata in which fossil remains have been deposited, serves to prove that, in general, a constant order has been observed in their formation.

The sea, by which the entire earth appears to have been covered, having rested in certain situations a sufficient length of time to collect particular substances, and sustain the life of certain genera and species of animals, has been afterwards replaced by another sea, which has collected other substances, and nourished other animals.

It may be believed that the primitive strata, which contain no organic remains, had all of them one contemporaneous origin. But, with respect to the strata which cover them, the study of fossil osteology has clearly proved that they were formed at different eras of time, during each of which animals existed distinct from those which lived in other eras, and distinct from almost all the known species which exist at the present day. It is true, that those causes to which the production of mountains is owing, have, in the countries which are intersected by primitive chains, or which border on them, disturbed the original established order of the strata. But, in level countries, it is perfectly obvious that they have been formed by a long and tranquil sojournment of the waters, in the same manner as are formed, at the present day, those depositions which cover the bottom of the seas.

Vegetable and animal remains are sometimes found at a depth of three or four thousand feet, and even below the sea, as in the instance of the coal-pits of Whitehaven. In all parts of the world, marine productions are to be found in a fossil state. They are found at very considerable degrees of elevation, on mountains far remote from the neighbourhood of any sea. So numerous, indeed, are they in certain places, that they constitute, to a very great extent, the aggregate of

the soil. These remains of organized bodies were formerly considered as mere lusus naturæ, generated in the bosom of the earth by its creative powers. But this absurdity has been completely refuted, by a thorough examination of their forms and composition. It has been clearly demonstrated that there is no difference of texture between the bodies of which we now speak, and those which exist in our present seas.

The marine genera, found in the most ancient, do not appear to be as numerous as those contained in the more recent strata; and it is worthy of remark that the fossil organic bodies of every description, differ more from existing species in proportion to the antiquity of the strata in which they are found. Those very ancient formations, to which the name of transition-strata has been given, rest upon the granite or other primitive rocks, which, as far as we can tell, form the substratum of the globe, and in which no organic remains have ever been discovered. We are thus led to the knowledge of a fact equally astonishing and certain, namely, that there was a period when life did not exist upon this earth; the era, indeed, of its commencement is clearly observable. This evidently proves the doctrine of a creation, and utterly confounds the absurd speculations of atheism respecting the eternity of the world, and the generative powers of inanimate matter.

The mode in which these primitive strata were formed is a mooted question. Some are of opinion that the ancient granite owed its origin to a fluid which once held every thing in solution, and others, that it was the first substance that became fixed, on the cooling of a mass of matter in a state of fusion. The Marquess de La Place has conjectured, that the materials of which the earth is composed were at first of an elastic form, and became, in cooling, of a liquid, and, finally, of a solid consistence. The recent experiments of M. Mitcherlich, says the Baron Cuvier, go far in support of this opinion. That gentleman has completely succeeded in composing and crystallizing several of the mineral species which enter into the composition

B 2

of primitive rocks. Be this, however, as it may, we find the shelvy summits of all the grand mountain-chains which intersect our continents composed of these primitive strata. The granite almost invariably constitutes the central ridges of these mighty chains, and, singular to relate, it occupies the highest and the lowest position in their stratification. That it was forced upwards by some tremendous convulsions of nature, which have shaken this globe to its very centre, is indubitable. The indented ridges, the ragged precipices, the bristling peaks, by which these primitive chains are always characterized, prove to demonstration the violence which was exerted in their production. In this respect, they exhibit a decided contrast to those more convex mountains, and undulating ranges of hills, whose mass was quietly deposited by the last retiring sea, and has since remained undisturbed by any violent revolution.

The lateral ridges of these chains are formed of schistus, porphyry, talc-rocks, &c. which rest on the sides of the granite. Finally, the external ranges are composed of granular marble, and other calcareous strata, but devoid of shells, which rest upon the schistus, and form the last boundary of the empire of mere inanimate matter. We now begin to find, but few in number, and, at intervals, in the transition strata, the earliest animal productions. We find the larger orthoceræ, those singular crustacea, the tribolites, the calymenes, the ogygiæ. We find encrinites, numerous species of cornua ammonis, and of terebratulæ, belemnites, trigoniæ, and other genera, most of which are no longer found in less ancient strata. Terebratulæ are found in these ancient strata, in the chalk formations above them, in the shelly limestone above those, and in the living state; but the number of species, and even of individuals of this genus, are found to diminish in an inverse ratio to the antiquity of the periods in which they existed.

We find shelly strata occasionally interposed between beds of granite and other primitive substances, which must have occupied their present situation at a more recent period. That

these primitive masses experienced changes and convulsions even previously to the appearance of life on this globe is evident. These masses indicate violent removals of position, some of which must have taken place before they were covered by the strata of shells. The disruptions we observe among them are sufficient proof of this. But since the formation of the secondary strata those same primitive masses have undergone similar convulsions. They have, not improbably, caused, most certainly they have shared in, the violent changes which have as evidently taken place in the secondary strata. How, if it were otherwise, could it happen that we find immense portions of those primitive rocks uncovered, though not situated so high as the secondary strata? We find numerous blocks of granite, &c. scattered over the secondary strata, even in situations where deep vallies, where portions of the sea intervene between them and those mountainous ridges from which they must have been transported. They must have been driven thither by tremendous eruptions or violent inundations, far exceeding in force and velocity any impelling cause with which we are now acquainted capable of changing the face of nature.

To enter very deeply into an examination of the acting causes which contribute at present, and have contributed ever since the era at which authentic history dates its commencement, to change the earth's surface, would be foreign to our present purpose. It will be sufficient to remark that these causes are rains and thaws, which bring down portions of mountains; streams which carry these on, and form what are termed alluvial depositions, in places where their course is slackened; the sea, which gradually changes the outline of the land, by undermining the more elevated coasts and forming precipitous cliffs, and throwing in heaps of sand upon the more level shores, thus gradually overspreading a considerable extent of terra firma; and finally, volcanoes, piercing through the solid strata and throwing heaps of matter around them to certain degrees of extent and elevation.

Now, the action of the waters, whether in rains, thaws, or running streams, which extend the land by the eventual deposition of debris, presupposes the existence of mountains, vallies, plains, and other inequalities, and consequently could not have produced them. The action of the sea is still more limited, and its phenomena have no affinity with the immense masses of whose revolutions we have been speaking; and volcanoes, though they have formed both mountains and islands, formed them of nothing but lava, i. e. of substances modified by volcanic action, which is never the case with the substances to which we have above alluded, nor do volcanoes ever disturb the strata which traverse their apertures. In a word, none of the agents acting on the earth's surface with which we are now acquainted, are capable of producing those tremendous revolutions which have left their traces so indelibly marked on the external covering of the globe. Neither will the circular motion of the pole of the earth, nor the gradual inclination of its axis on the plane of the ecliptic, better serve to explain such phenomena. The slowness and limited direction of these motions bear no proportion to the extent and overwhelming rapidity of such catastrophes. It follows, then, that they must have been occasioned by causes whose operation has long ceased, which were external to this planet, and most probably totally out of the course of things in existing nature. Many conjectures have been made by naturalists respecting the character of these causes, some eminent for absurdity, and all resting on hypothesis; into any of which it would be as wide of our design to enter as to propound any new solution of our own. It is enough to repeat that nothing in the agency of nature, as it has operated for ages in relation to this earth, could have produced the grand revolutions which this earth has evidently undergone; nor is it any absurdity to suppose that the agency which did produce them was preternatural.

To return to our more immediate subject; it is comparatively but a short time since the study of marine fossils has been

pursued with that degree of attention which it deserves. Involving infinitely greater difficulties than that of the conchology of existing species, much fewer of the former than of the latter have been discovered. It is yet the opinion of some eminent naturalists that the number of ancient species may equal, if not exceed, that of the modern. They are led to this conclusion by considering that the latter appertain but to a single era, while the former are attached to many successive periods in which animals of different descriptions have been abundantly produced.

It is but seldom that we meet with shells in the fossil state of species perfectly analogous to those which now exist. There is scarcely any exception to this but in the case of the fossils imbedded in the low hills of the Apennine range, of which a considerable number are found in a living state in the neighbouring Mediterranean. It is, however, remarkable that a number of mollusca and marine polypi found in this sea in abundance are not discovered in the fossil state, as, in like manner, fossil species are found in the Apennines that no longer exist. This want of perfect similarity is by no means surprising when we find that even species of the same strata, and of the existing seas, do not perfectly resemble when the habitat differs.

The remains of mollusca and zoophytes are much more numerous than other fossils, and the strata in which they are found are sometimes changed into calcareous stone. They are found in falun, in marl, in clay, and in grès or granulated brownish quartz. Shells, nearly resembling those of our marshes and streams, are found in the more recent strata.

Between the strata composed of marine fossils, we sometimes meet others containing terrestrial remains of animals or vegetables, which prove the settlement and return, at different periods, of the sea and fresh water, and even between these periods, the absence for a time of both, as it appears that the

terrestrial animals must have lived in the place where their remains are found.

The circumstance of finding, amidst the ice of the north, the carcasses of elephants and rhinoceroses with flesh and hair, proves that the retreat of the waters at the era of their destruction must have been prompt. A sudden change must have also taken place in the temperature of these countries; for these carcasses were found in places to which they could not have been transported at the present day, and were besides so frozen up, that in the instance of the elephant found by a Tungoose in 1799 (as will be subsequently seen), several years elapsed before all the parts of the body could be extricated.

Had the waters retired slowly, the entire surface of the earth so abandoned would have been like the shore of the sea; ancient cliffs would have been found wherever elevations existed, and the fossil shells would have been defaced like those now found on the sea-coast. But nothing of all this occurs. Many fossil shells are found broken, but not worn: their angular points are not blunted. This is declared by M. Defrance to be invariably the case with those of France, Italy, England, and North America, which he has examined, with the exception of such as are found in the falun of Touraine, which in all respects resembles the shelly sand of the sea-shore. The shells found there are almost all broken; their angles are blunted, and in the apertures of the univalves stones or other shells are repeatedly found which are difficult to be got out, just exactly as we find it to be with those on the sea-coasts. Terrestrial helices are even found there of a species unknown in the country filled with the debris of marine polypi and shells. It is natural to imagine that the soil of Touraine where the falun is found was exposed to the dashing of the waves which covered those parts of France where the bed of coarse, shelly limestone is found, and with which the falun of Touraine has the strongest affinity.

Fossil fish are found in the ancient marine strata as well as in the more recent. So are the crustacea which frequently accompany them. There is reason to believe, that a sudden revolution like that which a volcano might occasion, may have overwhelmed such of them as are found in the greatest abundance in certain places. The debris of osseous fishes are often found: but of the cartilaginous we find nothing but the vertebræ and teeth of squali. The coarse, shelly limestone, as well as the more recent strata, contains an immense quantity of debris of the claws of crustacea, and of the auricular bones of different sorts of fish.

The remains of terrestrial animals found in the fossil state consist of bones, the antlers of certain species of cervus, and teeth. It may be noticed, that such remains are rarely in a state of petrifaction. The horns of other ruminants, hoofs, claws, &c. are never found.

Oviparous quadrupeds, such as the crocodiles of Honfleur, of England, and the monitors of Thuringia, are found in very ancient strata. The saurians and tortoises of Maestricht are met with in the more recent chalk formation. The bones of lamantins and phocæ are found in a coarse, shelly limestone, very analogous to that which covers the chalk formation near Paris. The Baron has observed, in his great work, that up to this point no remains of mammiferous land animals have been found. Professor Buckland, however, to whose researches fossil osteology is so much indebted, has, in the first volume of the "Transactions of the Geological Society," given an account of a mammiferous quadruped occurring in an ancient secondary rock. In the calcareous slate of Stonesfield, in Oxfordshire, which lies in the upper part of the lowest division of oolitic rocks, have been found, says the Doctor, "two portions of the jaw of the didelphis, or opossum, being of the size of a small kangaroo rat, and belonging to a family which now exists chiefly in America, Southern Asia, and New Holland." The Doctor refers this fossil to didelphis on the

authority of the Baron himself, who has examined it twice, and the second time pronounced it to have been mammiferous, like an opossum, but of an extinct genus, and differing from all carnivorous mammalia in having ten teeth in a series in the lower jaw.

It is right, however, to remark here, that some controversy has arisen respecting the exact position of this calcareous slate in the minor subdivisions of the oolitic series at Stonesfield. To enter into the merits of this controversy would be quite beside our purpose; and, though we most strongly lean to the belief that the Doctor is justified in his conclusions, it would be presumptuous in humble compilers like ourselves, to pronounce decisively on so important a question.

Waiving this exception, if it be one, we find no bones of terrestrial mammalia until we come to the strata deposited above the last-mentioned formation of shelly limestone. There we first discover them, and there is a remarkable succession among the species. The debris of genera unknown at the present day, of anoplotheria, of palæotheria, found in the fresh-water formation, are the first which exhibit themselves above the shelly limestone. With those we find some lost species of known genera, oviparous quadrupeds and fishes. The beds in which they are found are covered by other strata, filled with marine fossils.

The fossil elephant, the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, and the mastodon, are not found with those more ancient genera. They are found in the ancient alluvial strata, sometimes with marine and sometimes with fresh-water productions; but never in the regular rocky strata. The species of these animals, and every relic found with them, are either unknown or doubtful: and it is only in the latest alluvial depositions that species which appear similar to those now existing are to be found.

Among the most astonishing phenomena which fossil osteology unfolds to our view, are those osseous breccie, which, though removed from each other the distance of many hundred

leagues, do yet present analogous peculiarities. Scattered rocks composed of the same stone are divided in different directions. Their fissures are filled with a calcareous concretion, very hard, and forming a sort of red ochreous cement, in which bones mixed with terrestrial shells are found imbedded. These bones, which are not petrified, have been almost all of them broken previously to their incrustation. These breccie are found in the rock of Gibraltar, at Cette, Nice, Antibes, in Corsica, in Dalmatia, and in the island of Cerigo; depositions nearly similar are found at Corcud, near Terruel in Arragon, in the Vicentine territory, and in the Veronese.

In the rock of Gibraltar have been found the bones of a ruminant animal, which the Baron thinks may appertain to antelope, and the teeth of one species of the genus lepus.

In the deposition at Cette, the bones of rabbits, of the size and form of such as now exist, have been found; others of the same genus, but one-third smaller; rodentia, similar to the campagnol; birds of the size of the wagtail, and snakes.

In the osseous breccia of Nice and Antibes are found the bones of horses, and ruminant's teeth of the latter order, of species about the magnitude of cervus.

The breccia of Corsica contains debris of lagomys, existing at present only in Siberia, and bones of a rodens resembling perfectly the water-rat, except that it is smaller.

We find in those of Dalmatia, the bones of ruminants of the size of dama.

Of the bones in the breccia of the island of Cerigo, we have no account, except from Spallanzani, who imagined that human bones existed among them. This opinion, however, appears totally destitute of foundation.

In the deposition of Corcud, the bones of asses and oxen have been found, resembling those of the present day, and of sheep of a very diminutive size.

In the Vicentine and the Veronese breccia, the antlers and bones of cervus have been found, together with the bones of

oxen and elephants. A tusk of one of these last was nearly twelve feet in length.

Similar discoveries have also been made in the fissures of Sicily and Sardinia, and in different parts of Germany. But it is impossible to afford in this place any further detail concerning them.

In the plaster-quarries in the neighbourhood of Paris, are found skeletons of genera for ages extinct, such as the anoplotherium and palæotherium: also bones of an animal bearing affinity to the sarigue, of four species of carnivora, with debris of tortoises, birds, and fishes.

The loose strata exhibit bones, teeth, and tusks of elephants, mingled with bones of horses, in almost every country; of mastodons, in America, in Little Tartary, in Siberia, in Italy, in France; of the rhinoceros, in France, in England, in Italy, in Germany, and Siberia; of the hippopotamus, near Montpellier, in Italy, and England, &c. &c. of an animal resembling the tapir in the south of France; of a gigantic species of cervus, resembling the elk in Ireland and England; of the Indian musk-ox in Siberia; of fallow-deer of an unknown species in Scania; of hyaenas, near Eichstadt; of balænæ, in the Plaisantin; and of an immense animal of the family tardigrada, called the megatherium, a species unknown in the living state, near Buenos Ayres.

In the turbaries of the department of the Somme in France, have been found debris of the aurochs, of oxen, far surpassing in magnitude our domestic races; of beavers, of cervi of unknown species, of horses, of roebucks, and of wild boars.

We are far, indeed, from having enumerated all the discoveries of this description that have been made, nor will our limits permit us to do so. Even since the publication of the last edition of the "Ossemens Fossiles," thirty species have been found in volcanic tufa in the strata of Mount Perrier, near the Issoire, in France;—namely, nine ruminants, six pachydermata, one edentatum, twelve carnivora, and two ro-

dentia. In the calcareous fresh-water formation of Volvic, ten species;—one ruminant, two anoplotheria, one palæotherium, two rodentia, two carnivora, and two reptiles. In the similar formation of Gergovia, four species;—one anoplotherium, one reptile, and two ornitholites. Nay, even as we write, these discoveries are being prosecuted on the Continent and in America, with a zeal, assiduity, and success, unexampled in any former era in the annals of science; nor can it be expected, by any possibility, that a sketch like the present should embrace them all.

Phenomena not less astonishing than those on which we have been hitherto commenting, are exhibited in certain ancient caverns which have been discovered in Germany, in Hungary, and in England. They equally surprise and interest us by the immense quantity of debris of fossil animals which they contain, and the remarkable analogy that exists among them all in a geological point of view. To attempt any thing even approaching to a complete account of them here would be impossible. We shall, however, notice some of their most striking peculiarities; and for a fuller description refer our readers to the "Reliquiæ Diluvianæ" of Professor Buckland, a work equally admirable for deep research, luminous exposition of facts, and sound deduction.

The most anciently celebrated of these caverns, according to the Baron, is that of Bauman, near the city of Brunswick. The entrance faces the north, but the entire direction is from east to west. The entrance is very narrow. The first chamber is the largest. Into the second it is necessary to descend by a passage, first creeping, and then with the assistance of a ladder. The difference of level is thirty feet. This second chamber most abounds in stalactite, of a variety of forms. The passage to the third chamber is at first the most difficult of all. It is necessary to climb with hands and feet, but it gradually enlarges, and the stalactites upon its roof and sides exhibit an astonishing variety of fantastic and beautiful figures. There

are in this passage two lateral dilatations, constituting a third and fourth chamber in the map of the Acta Erud: At its extremity it is necessary again to re-ascend to arrive at the entrance of the third chamber, which forms a sort of portico. Behrens, in his Hercynia Curiosa, says that there is no penetrating there, as it would be necessary to descend more than sixty feet. But the map above-mentioned and the description of Van der Hardt which accompanies it, characterize this third chamber as the fifth, and place beyond it another tunnel or passage terminated by two small caverns. Silbersschlag, in his Geogenie, adds that one of them leads into a final tunnel, which, descending considerably, leads under the other chambers, and is terminated by a place filled with water. There are abundance of fossil remains in this remote and unfrequented part.

The principal portion of the bones discovered in this cavern belong to the genus of the bear.

Other caverns very nearly similar are found in the chain of the Hartz mountains. Many are also found in Hungary on the southern declivities of the Krapach mountains. But the most celebrated of all is that of Gaylenreuth, situated on the left bank of the Wiesent. It is composed of six grottoes, which form an extent of more than two hundred feet. These caverns are strewed with bones, great and small, which are all of the same description as are to be found over an extent of more than two hundred leagues. More than three-fourths of these bones belong to a species of bear as large as our horses, and which is longer found in the living state. The half or two-thirds of the remaining bones belong to an hyæna, of the size of the living bear. There were also the remains of a tiger, wolf, fox, glutton, and pole-cat, or some species approximating to it. The bones of herbivera are also found there, particularly of cervi, but in smaller number. Sœmmering has also mentioned that a portion of the cranium of an elephant was extracted from this cavern.

It is the opinion of the Baron that the remains in question belonged to animals which lived and died in the caves in which their debris are found, and that the period of their establishment there was considerably posterior to the era in which the extensive rocky strata were formed. In his first edition, he expressed his opinion that it was subsequent to the formation of the loose strata in which the bones of the elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus have been discovered. But he has since altered this opinion, and fully coincides with Dr. Buckland that the bones of the caverns and the osseous breccia, are of the same antiquity with those of the loose strata, and that all were prior to the last general catastrophe which overwhelmed this globe.

Of the Megalonix, an extinct animal of the sloth genus, the remains have been found in a cavern in Western Virginia.

Of the caves of this country the most remarkable is that of Kirkdale, in Yorkshire, visited and first described by Dr. Buckland. The generality of educated readers must be so well acquainted, through the medium of various publications, with the researches of the learned professor, that we shall be excused from following him through his very minute and lucid description of the geological position and internal peculiarities of this cavern: for our present purpose it will be sufficient to observe, that the teeth and bones discovered in the cave pf Kirkdale are referable to twenty-three different species of animals;—six carnivora, four pachydermata, four ruminantia, four rodentia, and five birds. Among the carnivora, the most numerous by far appear to have been hyænas of a larger size than any known at present. Their teeth were so very abundant, that the professor does not calculate the number of animals to which they belonged at less than two or three hundred. Two large canine teeth of the tiger were found four inches in length, and a few molars exceeding in size those of the largest lion or Bengal tiger. There was one tusk of a bear, which appears to have been specifically identical with the ursus spelœus of the Ger-

manic caves, and which, as we have already observed, equalled the horse in magnitude. The bones of the elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus were found co-extensively with all the rest, even in the inmost and smallest recesses. The teeth of deer of two or three species are also numerous, but the most abundant of all are those of the water-rat.

The conclusion of the professor respecting this cave is, that it was inhabited during a long succession of years previous to the last general deluge, by hyænas, and that they dragged into it the other animal bodies whose remains are found there. The bones are all comminuted and broken; and many of them distinctly bear the impress of the canine fangs of the hyæna, an animal whose appetite for bones and tremendous power in fracturing them is well known. The professor considers, that, at the period of the last general inundation, the floor of the cave was covered with the diluvial loam and pebbles under which these bones were found, and had been so long preserved from decomposition by this covering of mud, and the coating of stalagmite above it. Several other caverns and fissures have been discovered in this country and in Wales, containing osseous remains, the greater portion of which are referable to the antediluvian era. Near Wirksworth, in Derbyshire, in a cave called Dream Cave, was found the skeleton of a rhinoceros, nearly entire. At Oreston, near Plymouth, three deposits were found of a similar nature, containing great quantities of bones. In the cave of Paviland, in Glamorganshire, were found remains of elephant, rhinoceros, horse, hog, bear, hyæna, &c. In this cave, a human skeleton was also found; but its circumstances, position, state of preservation, &c., prove it to be most clearly postdiluvian.

From all the facts of this description which have been ascertained, Dr. Buckland concludes, that previously to the last general catastrophe, the extinct species of the hyæna, tiger, bear, elephant, rhinoceros and hippopotamus, as also wolves, foxes, oxen, deer, horses, and other animals not distinguishable

from existing species, existed contemporaneously in this country; and the Baron, from similar inductions, has drawn a similar conclusion respecting the continent of Europe.

The general circumstances of all these caverns are, as we have observed, extremely similar. The hills in which they are excavated resemble each other in their composition. They are all calcareous, and produce stalactite in abundance. The roofs, sides, and passages in the caverns are ornamented and contracted by it in all its boundless variety of configuration. The bones are nearly in a similar state in all these deposits. Detached, scattered, partly broken, but never rolled, as would be the case had they been brought from a distance by the force of inundations. Somewhat specifically lighter, and less solid than the recent bones, they yet preserve their genuine animal nature, are not much decomposed, still contain plenty of gelatine, and are never in a state of petrifaction. A hardened earth, but still liable to break or pulverize, impregnated with animal manner, and sometimes of a blackish colour, constitutes their natural envelope. This is, in many instances, interpenetrated and covered by a crust of stalactite of the finest alabaster. The bones themselves are sometimes clothed with the same material which enters their natural cavities, and occasionally attaches them to the walls of the cavern. From the admixture of animal matter, this stalactite often exhibits a reddish hue. At other times its surface is tinted with black. But these are accidents of recent occurrence, and independent of the cause which introduced the bones into their present locale. It is easy to observe, that this same stalactite is daily making a rapid progress, and invading those groups of osseous remains which it had hitherto left untouched.

This mass of earth, intermixed with animal matter, envelopes without distinction the bones of all the species, and if we except a few on the surface of the soil, and which, from their comparative freshness, we must conclude to have been transported thither at a much later era, all were evidently

C

interred in the same manner, and by the same agents. In a great many of these caverns, especially in that of Gaylenreuth, are found pieces of bluish marble, the angles of which are rounded and blunted, clearly testifying the influence of that diluvial action which hurried them along. A similar phenomenon is observable in the osseous breccia of Gibraltar and Dalmatia.

The pachydermatous remains, so common in the loose or ancient alluvial strata, are very rarely found among the fossil carnivora of the Germanic caves: nor are the bones of the latter very frequent in the alluvial strata. This circumstance, at first, led M. Cuvier to assign different eras to those respective remains. But, independently of the fact that the reverse is sometimes the case in these situations, the discoveries made in our British caves have clearly demonstrated the contemporaneous existence of the animals in question; and the Baron, with that single-minded devotion to the cause of science invariably characteristic of the highest order of philosophical genius, has subsequently avowed that this important fact has been completely established by Dr. Buckland.

There are but three imaginable causes by which such quantities of bones could have been accumulated in those vast subterraneous repositories. Either they are the remains of animals which lived and died there undisturbed, or they were carried thither by inundations, or some other violent cause, or they, were originally enveloped in the stony strata whose dissolution produced those excavations, and were not dissolved by the agent which removed the material of the excavated strata. The last supposition is refuted by the fact of these same strata containing no bones; and the second, by the integrity of their smallest prominences, which will not permit us to suppose that they have been rolled, or have suffered any violent change of place. Some of these bones, indeed, are a little worn, but, as Dr. Buckland remarks, on one side alone; which only proves that some transient current has passed over them in the de-

posit where they are found. The first supposition, then, which, as we observed, the Professor adopted in explanation of the phenomena of Kirkdale-cave, is the only one that can be admitted in reference to all the rest which exhibit phenomena precisely similar. There are certainly some cases of caverns in which we may otherwise account for the presence of bones. Animals may have retired there to die, fallen accidentally into their fissures, or been washed in by diluvial waters. But such hypotheses will only explain the cases where the bones are few and not gnawed, the caverns large, and their fissures extending upwards. In all other instances we can only account for the vast accumulation of bones by the agency of beasts of prey.

It is, however, quite certain that the period in which the animals lived in these caves was considerably subsequent, not only to the formation of the extended rocky strata of which the mountains where they are excavated are composed, but to that of similar strata of more recent date. No permanent inundation penetrated into these subterraneous recesses, or formed there any regular stony deposition. The rolled pebbles that are found there, and any traces of detrition on the bones, indicate nothing but the transitory passage of evanescent waters.

"How, then," exclaims the Baron, "have the ferocious beings which once peopled our ancient forests, been extirpated from the surface of the earth? The only reply that can be given is, that they were destroyed at the same time, and by the same agency, as the large herbivora, which were fellowinhabitants with themselves, and of which no traces in existing nature are any longer to be found."

The debris of birds have been found in the fossil state, the genera of which involve some difficulty in the determination. Of these we treat in the proper place.

The genera of fossil reptiles are well characterized; such are the tortoises, the crocodiles or saurians, the monitors, the

C 2

salamanders, the protei, the frogs, and a lizard with the wings of a bat, called pterodactylus, on which the present is no place to extend our remarks.

Insects are found in the fossil state in calcareous, foliated stones, and in amber, where they are preserved without any alteration. In Prussia, where this resinous fossil production is most usually found, the insects exhibited there are all of them foreign to the climate.

The debris of vegetable fossils are found in the ancient as well as in the recent strata; but they are more common in the latter, and even on the surface of the earth. They consist for the most part in ligneous trunks, almost always changed into silex, in kernels, seeds, and the impressions of leaves, disposed between the veins of fissile stones. Those found in the mines of pit-coal belong for the most part to the family of fern, bamboo, casuarinas, and other plants, foreign to the climate in which they are thus found. These mines, situated between the granitic or porphyritic schists, are very ancient, and contain no marine shells. It is not thus with similar mines which occur in the calcareous formation. They do not appear to be equally ancient; and instead of recognizing in them the impressions of fern, &c. we find in some of them succinum, and shells of the genus am pullaria, which appear to appertain to marine depositions. The palm-tree of different kinds has been found in many situations in the fossil state, in countries to which the particular species were not native. Near Canstadt, in the duchy of Wirtemberg, an entire forest was discovered of palm-trees in a horizontal position, each two feet in diameter. In Cologne, from Bruhl, Liblar, Kierdorf, Bruggen, and Balkhausen, as far as Watterberg, are found, over many leagues of country, immense depositions of wood changed almost entirely into mould, and covered with a bed of rolled flints, from ten to twenty feet in height. This deposit, which exceeds fifty feet in thickness, also contains trunks of trees, and nuts, which exhibit a strong analogy to the areka which

grows in India. In the midst of quartzose sands of the most arid kind in the African deserts, and on the surface of a soil for ages under the curse of sterility, are found considerable quantities of the trunks of trees changed into silex. Buried in the peat, on a mountain in the department of the Isère, in France, fossil wood was found not less than 2000 feet above the most elevated line where trees can grow at the present day *.

We have now to notice a fact connected with fossil osteology of the most singular and striking kind. We find, as has been seen, quadrupeds of different genera, cetacea, birds, reptiles, fishes, insects, mollusca, and vegetables, in the fossil state. But to the present moment no human remains have been found, nor any traces of the works of man in those particular formations where these different organic fossils have been discovered. What is meant by this assertion is, that no human bones have been found in the regular strata of the surface of the globe. In turf-bogs, alluvial beds, and ancient burying-grounds, they are disinterred as abundantly as the bones of other living species. Similar remains are found in the clefts of rocks, and sometimes in caves, where stalactite is accumulated upon them; and the stage of decomposition in which they are found, and other circumstances, prove the comparative recentness of their deposition; but not a fragment of human bone has been found in such situations as can lead us to suppose that our species was contemporary with the more ancient races,—with the palæotheria, the anoplotheria, or even with the elephants and rhinoceroses of comparatively a later date. Many authors, indeed, have asserted, that debris of the human species have been found among the fossils, properly so called; but a careful examination of the facts on which

* In speaking of fossil vegetables, we should not omit to mention the name of our countryman, Mr. Parkinson, who, in his "Organic Remains," was one of the first writers who threw considerable light on the subject of fossils in general. Though erroneous in some of his speculative notions, his work contains a summary of facts of the utmost importance to this branch of science.

such assertions were founded, have proved that these authors were utterly mistaken. We refer our readers to the preliminary discourse of the Baron to his "Ossemens Fossiles," for the most complete satisfaction on this question. The same may be asserted of all articles of human fabrication. Nothing of that description has ever been found indicating the existence of the human race at an era antecedent to the last general catastrophe of this globe, in those countries where the strata have been examined, and the fossils discoveries we are treating of been made. Yet there is nothing in the composition of human bones that should prevent their being preserved as well as any others. There is no principle of premature decomposition in their texture. They are found in ancient fields of battle equally well preserved with those of horses, whose bones we know are found abundantly in the proper fossil state. Neither can it be said that the comparative smallness of human bones has anything to do with the question, when it is recollected, that fossil remains of some of the smallest of the rodentia are to be found in a state of preservation.

The result, then, of all our investigations serves to prove that the human race was not coeval with the fossil general and species: for no reason can be assigned why man should have escaped from the revolutions which destroyed those other beings, nor, if he did not escape, why his remains should not be found intermingled with theirs. His bones are found occasionally in sufficient abundance in the latest and most superficial depositions of our globe, where their bones are never found: their bones are in immense quantities in some of the ancient strata of the earth, where no traces of him exist. Human remains in caverns and fissures, along with some of those more ancient debris, prove nothing for the affirmative of man's coeval existence with the lost species. Their freshness proves the lateness of their origin; their fewness, the impossibility that mankind could have been established in the adjacent regions at

the period when those other animals lived there; and their situation and general circumstances, the accident of their introduction.

It is a fact not less remarkable, that no remains of the qua-drumanous races, which occupy the next rank in creation to man, at least in physical conformation, are to be found in the strata of which we have been speaking. Nor will this fact be deemed less remarkable, when it is considered that the majority of the mammifera there found have their congeners at present in the warmest regions of the globe, in the intertropical climates, where those anthropomorphous animals are almost exclusively located.

Where, then, was the human species during the periods in question? Where was this most perfect work of the Creator, this self-styled image of the divinity? If he existed any where, was he surrounded by such animals as now surround him, and of which no traces are discoverable among the organic fossils? Were the countries which he and they inhabited overwhelmed by some desolating inundation, at a time when his present abodes had been left dry by the retreating waters? These are questions, says the Baron, to which the study of the extraneous fossils enables us to give no reply.

It is not meant, however, to deny that man did not exist at all in the eras alluded to—he might have inhabited a limited portion of the earth, and commenced to extend his race over the rest of its surface, after the terrible convulsions which had devastated it were passed away. His ancient country, however, remains as yet undiscovered. It may, for aught we know, lie buried, and his bones along with it, under the existing ocean, and but a remnant of his race have escaped to continue the human population of the globe. All this, however probable, is but conjecture. But one thing is certain, that in a great part of Europe, Asia, and America, countries where the organic fossils have been found, man did not exist previously to the revolutions which overwhelmed these remains, nor even pre-

viously to those by which the strata containing such remains have been denudated, and which were the latest by which this earth has been convulsed.

It only remains for us now to give a summary view of the succession of strata, and an enumeration of the different fossil genera and species in the respective strata, by the order of which we are enabled to calculate to a certain extent the number of revolutions the globe has undergone. In doing this, we shall pursue the order observed by the Baron in his great work.

In speaking of the strata of which this globe is composed, we must be understood to mean here nothing more recent than that formation which is proved to have resulted from the last grand catastrophe by which the earth was overwhelmed. The strata then formed, the most superficial of the regular strata, consisting of beds of loam and argillaceous sand, mixed with rolled pebbles from remote regions, and filled with debris of land animals unknown, or foreign to the places in which they are found, appear to have covered all the plains, and the floors of the caverns, and choked up the fissures of the rocks within their reach. To such formations, Dr. Buckland has given the name of diluvium, and described them with his usual clearness and accuracy. They must be considered as totally distinct from the other strata, which, like them, are equally loose, but have been continually deposited, by streams and rivers, in the usual course of nature, since the last great convulsion of the globe, and which contain no fossil remains, but such as are indigenous to the country where they are found. These last depositions Dr. Buckland distinguishes by the term alluvium, and they must be considered as entering for nothing into the question of the grand revolutions of the earth. But in the diluvial strata, all modern geologists have discovered the clearest evidence of that tremendous inundation, which constituted the last general catastrophe by which the surface of our planet has been modified. It may not be amiss to inform our

readers here, that both these formations, agreeing in their character of uncompactness, but differing in their antiquity, are alike termed loose, or alluvial, by Cuvier and other geologists. We do not altogether deviate from this usage in our subsequent account of the fossil species; but when we use the term alluvial, in relation to organic debris, we must be understood to mean the diluvial formations.

Between this diluvium and the chalk formation are strata alternately filled with fresh and salt water productions. These mark the irruptions and retreats of the sea to which our portion of the globe has been subjected, subsequently to the formation of the chalk. First come marly beds, and cavernose silex, similar to those of our ponds and morasses. Under these are marle again, sandstone, and limestone, containing nothing but marine productions.

At a greater depth we find fresh-water strata, of an era more remote. Among these are reckoned the celebrated plasterquarries in the neighbourhood of Paris, where the remains of entire genera of terrestrial animals have been found, which exist no longer.

These last-mentioned strata rest on beds of calcareous stone, in which an immense number of sea-water shells have been collected, the great majority of which belong to species unknown in the existing seas. In this formation are also found the bones of fishes, cetacea, and other marine mammalia.

Under this marine limestone we have again another freshwater stratum, composed of argilla, in which are interposed considerable beds of lignite, or that species of coal which is of a more recent origin than our pit-coal. Here are found shells only of the fresh water, and bones among them, not of mammiferous animals, but of reptiles. It is filled with crocodiles and tortoises, &c., whereas the mammiferous genera contained in the gypsum are not seen there. They did not yet exist in the country when the argilla and lignites were in a course of formation.

This last fresh-water formation, which supports all the

strata just enumerated, and appears the most ancient of the Parisian depositions, is itself supported by the chalk. This formation, of immense thickness and extent, appears in countries as remote from us as Pomerania and Poland. But in the neighbourhood of Paris, in Berri, in Champagne, in Picardy, and a considerable part of England, it predominates uninterruptedly, and forms a most extensive circle, or basin, in which all the strata we have mentioned are contained, and its edges are barely covered by them in these places where the superstrata are least elevated.

Such superstrata are not confined to the countries just instanced, or to the basin in question. Depositions, more or less similar, and containing organic remains, are found in other regions, wherever the surface of the chalk affords similar cavities for their reception. They are found even where no chalk formation exists, and where the most ancient strata constitute their only support. The two distinct formations with fresh-water shells have been found in England, Spain, and even on the confines of Poland; the marine beds interposed between them exist along the entire range of the Apennines. Some of the quadrupeds of the Parisian plaster-stones have been found elsewhere, as, for instance, in the gypseous strata of Valai, and in the molasse quarries in the South of France.

Thus it appears, that the partial revolutions which took place between the era of the chalk-formation, and that of the last great inundation, and which consisted in the alternate inversion and retreat of the sea, occurred in many countries. This globe has undergone a long series of agitations and changes, which appear to have been rapid in their operation, from the comparative slightness of the depositions they have left behind. The chalk has evidently been the production of a more tranquil and extensive sea. It contains marine productions alone, but among them the most remarkable remains of vertebrated animals, all of the fish or reptile class—tortoises and lizards of colossal size and extinguished genera.

A very considerable portion of Germany and England is composed of strata anterior to the chalk, in the hollows of which the chalk reposes, just as the intermediate strata before mentioned rests in its own cavities. Immediately under the chalk, and indeed partially intermingled in its lowest strata, are depositions of green sand, and ferruginous sand below it. In many countries both are found condensed into banks of sandstone, in which are seen lignites, succinum, and debris of reptiles.

After these come the immense accumulation of strata composing the mountain-chain of Jura, which extends into Suabia and Franconia, the chief summits of the Apennines, and many similar formations in England and France. They consist in calcareous schistus, abounding in fish and Crustacea, immense banks of oolite, marly and pyriteous grey limestone, containing ammonites, oysters with curved valves, and reptiles of more extraordinary character and conformation than any of their predecessors.

These, which we shall take leave to call Jurassic strata, are supported by extensive beds of sand and sandstone, in which the impressions of vegetables are frequently found, and which rest upon a limestone which has been termed coquillaceous, from the immense quantities of shells and zoophytes with which it abounds. It is separated by other strata of sandstone of the variegated kind, from a limestone still more ancient, called Alpine, because it composes the loftier range of the Tyrol Alps; but, in fact, it appears also continually in the east of France, and the entire south of Germany.

In the limestone called coquillaceous, are deposited considerable accumulations of gypsum and rich beds of salt. Below it we find slender strata of coppery schistus, with abundant remains of fish, and some fresh-water reptiles. The coppery schistus rests upon a red sandstone, of the same age as the pit-coal, which we have before alluded to as bearing the impressions of the earliest vegetable productions which adorned the surface of the globe.

We now come rapidly to the transition strata, where matter lifeless and unorganised appears to have made its last stand against the vivifying and organising principle of nature. Here we find black limestone and schistus, with Crustacea and shells of unknown genera, alternating with the latest of the primitive strata. We finally arrive at the most ancient formations which we are permitted to discover,—the marble, the primitive schistus, the gneiss, and the granite, the ancient foundations of the earth, and which are themselves, in all probability, the result of the united action of fire and water, after myriads of revolving ages.

Such is the exact enumeration of the series of strata which compose our globe; such is the order of facts which geology has been enabled to establish, by calling in the aid of mineralogy, and the sciences of organization, by abandoning the reveries of arbitrary hypothesis, and steadily pursuing the safer path of observation and induction.

We shall now rapidly enumerate the fossils in those various allocations, beginning with the earliest, and ending with the latest formations.

We have observed that zoophytes, mollusca, and certain crustacea, begin to appear in the transition strata. Bones and skeletons of fish may, perhaps, be also found there. But we are far from discovering, among those early formations, the remains of land animals, or any formed for the direct respiration of atmospheric air.

The great strata of pit-coal, and the trunks of palm and fern of which they bear the impression, must presuppose the existence of dry land and aërial vegetation. Yet no bones of quadrupeds are found there, not even of the oviparous species.

Their first traces are found a step higher, in the bituminous coppery schistus. There we find quadrapeds of the family of the lizards, very similar to the monitors, which are now natives of the torrid zone. Many individuals of this description are found in the mines of Thuringia in Germany, among innu-

merable fish, of a genus unknown at present, but which, from its analogy with some existing genera, appears to have inhabited the fresh water. The monitors we know to be inhabitants of the same element.

A little higher is the Alpine limestone, and on it the coquillaceous limestone, abounding in entrochi and encrini, and forming the basis of a great portion of Germany and Lorraine. It contains the osseous remains of a very large sea-tortoise, and another reptile of the lizard tribe, of very great length, and pointed muzzle.

Next come certain sandstone strata, having only vegetable impressions of the large reeds, bamboos, palms, &c.; and then of Jurassic limestone, where the remains of the reptile class exhibit a diversity of singular conformations, and a gigantic degree of development. Its middle portion is composed of oolites and lias, or the gray limestone, containing therecurvivalve oysters; and in it were found the debris of two most extraordinary genera, uniting the characters of oviparous quadrupeds, with locomotive organs, like those of the cetacea. Those are the ichthyosaurus and plesiosaurus, first discovered and determined here by our distinguished countrymen, Sir Everard Home and Mr. Conybeare. These, with their species, shall be described in the proper place. Their skeletons are in a state of high perfection, and their remains have been found extended through all the formations of lias.

In the same deposition were also found two species of the crocodile, amidst ammonites, terebratulæ, and other shells of the ancient sea. These are called by Cuvier the long-beaked and short-beaked gavial. Another crocodile was discovered in the oolite at Caen, and another in the same formation here.

The megalosaurus, a fossil reptile of prodigious size, has been discovered by Dr. Buckland in this country. Its remains appear to have been contemporaneous with the concretion of the lias, but are also dispersed abundantly in the oolite and higher sands. From the magnitude of a femur and other

bones, found in the ferruginous sandstone of Tilgate-Forest, in Sussex, the Doctor calculates that the animal in question could not have been less than from sixty to seventy feet in length. Remains of this reptile, or at least of species referrible only to this genus, have been also discovered in France and Germany, in the calcareous slate above the oolitic beds.

In this same slate, the long-beaked crocodiles continue to abound; but the most remarkable animals there are the pterodactyls, or flying-lizards. They appear to have been sustained in the air, on the same principle as the cheiroptera: they had long jaws, armed with trenchant teeth, hooked claws; and some species, as would seem from the fragments remaining, arrived at a considerable size.

In the nearly-homogeneous limestone of the crests of Jura, a little higher than the calcareous slate, are bones, but invariably of the reptile class. There are crocodiles, but more especially fresh-water tortoises, as yet not fully determined, but many of which, by their magnitude and conformation, are strongly distinguished from all known species.

Amid those innumerable reptiles, whose varied structure and colossal dimensions rival, if not surpass, the fabled monsters of poetical antiquity, we begin, as is said for the first time, to recognise the remains of some small mammalia. Jaws and bones have been discovered in England, appertaining to the families of the didelphis and insectivora, in these situations. But if the locale of Dr. Buckland's discovery of the opossum before-mentioned be completely established, it must be granted that they appear sooner. Cuvier, however, seems to think that the rocks in which the bones in question are incrusted may owe their existence to some local recomposition, posterior to the era of the original formation of these strata; and it is most certain that, even for a period considerably subsequent, the reptile class exclusively predominate. In the ferruginous sands above the chalk in England, abundance of those already enumerated occur; and an additional reptile has been discovered there

by Mr. Mantell, of Lewes, which seems to have been herbiviorous, and to have inhabited the fresh water. This is the iguanodon, and it is supposed to have been sixty feet long.

In the chalk, according to Cuvier, there are only reptiles, the remains of crocodiles and tortoises. In the tufa of Mount St. Pierre, near Maëstricht, which is of the chalk formation, has been found, amidst marine tortoises, shells and zoophytes, another gigantic member of the saurian family, a distinct genus, for which Mr. Conybeare has proposed the name of mosasaurus.

In the argilla and lignites, covering the superior portion of the chalk, the Baron declares that he has discovered nothing but crocodiles; and thinks that the lignites of Switzerland, in which are bones of the beaver and mastodon, must be assigned to a more recent era. He adds, that it was only in what the French call the calcaire grossier, surmounting the argilla, that he commenced to discover mammiferous remains, and that they belonged to marine mammalia. But Dr. Buckland mentions the occurrence of these in the stratum of Cuckfield, in Sussex, much anterior to the formation of which we now speak; and they are also declared to have been found in the calcareous slate of Stonesfield, and in the corn-brash limestone in Oxfordshire.

These marine mammalia are dolphins, lamantins, and morses, apparently of an unknown species. The lamantin is at present confined to the torrid zone, and the morse to the Icy Sea; still those two genera are found together in the coarse limestone, in the midst of France. This union of species, whose consimilars are now allocated in opposite zones, is by no means uncommon.

In the strata succeeding this coarse limestone, or in the ancient contemporaneous fresh-water depositions, the class of terrestrial mammifera first begins to appear in tolerable abundance. Belonging to the same age are the animal remains buried in the molasse and ancient gravel-beds in the south of France;

in the gypsum, mixed with limestone, in the environs of Paris and of Aix, and in the marly fresh-water formations, covered again with marine strata, in Alsace, Orleannais, and Berri.

These organic remains are singularly remarkable, as belonging to a variety and abundance of certain genera of pachydermata, now rotally extinct, and approximating more or less in character to the tapir, rhinoceros, and camel. These genera, for whose discovery we are entirely indebted to the Baron, are the palæotherium, laphiodon, anoplotherium, antracotherium, cheropotamus, and adapis. Of these there are about forty species, all extinct, and to which there are none analogous in the living world, except two tapirs and a daman.

In the same formation with these pachydermata are some remains of carnivora, of rodentia, of birds, of crocodiles, and tortoises. Of the first, a bat, (and, singular to relate, the only instance of the kind occurring in this or subsequent formations,) a fox, an animal approximating to the racoons and coatis, a peculiar species of genet, some other carnivora not so easily determined, and, most remarkable of all, a small sarigue, a genus now confined to America. There are two small rodentia of the dormouse kind, and a head of the genus squirrel. In the gypsum of Paris, bones of birds are very abundant, constituting the remains of at least ten species. The crocodiles approximate to those of the present age, and the tortoises are all of the fresh water. There are also remains of fish and shells, in great part unknown at present.

There can be no doubt that this immense animal population of what Cuvier calls the middle age of the earth, has been entirely destroyed. Wherever its debris have been discovered, there are vast superincumbent beds of marine formation, proving the invasion and long continuance of the sea in the countries inhabited by these races. Whether the countries subjected to such inundation at this era were of considerable extent or not, our present acquaintance with the strata in question does not enable us to decide. These formations, however, embrace the

gypsum or plaster-quarries of Paris, and those of Aix in Provence, and many quarries of marle-roeks and molasse in the south of France. Certain portions of the molasse of Switzerland, and the lignites of Liguria and Alsace, are referrible to the same. As for the fossil bones of England, Italy, and Germany, they belong either to an earlier or a later era,—to the ancient reptiles of the Jurassic strata and copper-slate, or to the diluvial formations of the last universal inundation.

We may, then, fairly suppose, that, at the period when these numerous pachydermata existed, there were not many fertile plains to afford pasture for their support. These plains, too, in all probability, were insulated districts, intersected by those elevated mountain-chains in which we discover no traces of those extinct animals.

In the same strata with those pachydermatous remains are found the trunks of palm, and many other relics of those magnificent vegetable productions which at present are indigenous to tropical climates alone.

The sea which covered these formations has left extensive depositions, constituting, at a moderate depth, the foundation of our present large plains. It again retired, and left open immense surfaces of soil to a new population, the debris of which abound in all the sandy and loamy strata of every region of the globe which has been subjected to examination.

To this last tranquil deposition of the sea we must refer some cetacea, very similar to the existing species. Among these an entirely new genus has been discovered, and named ziphius by Cuvier. It contains three species, and approximates to the cachalots and hyperoodontes.

Among the animals which lived on the surface of this deposition, when it became dry land, and whose debris now fill the loose strata of the earth, we find no palæotheria, or anoplotheria, none of the extraordinary and extinct genera contained in the gypseous formations. Still, however, the order pachydermata predominates; but in the gigantic genera of the elephant,

D

rhinoceros, and hippopotamus, accompanied with innumerable bones of horses, and many of the larger ruminantia. This new animal kingdom was devastated by carnivora, of the magnitude and generic characters of the lion, the tiger, and the hyæna. This population, the remains of which extend to the extremity of the north, and the borders of the Frozen ocean, has, generally speaking, nothing congeneric at present, except in the torrid zone, but in all cases a specific difference is sufficiently marked.

Among these species are the elephas primigenius, or mammoth of the Russians, whose remains are found from Spain to the coasts of Siberia, and throughout all North America; the mastodon, with narrow teeth, common in the temperate parts of Europe and the mountains of South America; the great mastodon, in immense abundance in North America; an hippopotamus, very common in England, Germany, France, and Italy, and a smaller species; three rhinoceroses, chiefly in Germany and England; a gigantic tapir, in Germany and France, and an apparently extinct genus, resting on a single fragment, discovered in Siberia, and called elasmotherium by Fischer.

The bones of the horses are not so clearly determined to belong to distinct species. Of the ruminantia several species may be pronounced distinct, particularly a stag superior in size to the elk, common in the marle and peat of England and Ireland, and whose remains have also been found in Italy, France, and Germany; among the elephantine bones of the deer and ox of the caverns, and osseous breccia, which appertain to the same era, we cannot speak so decidedly. It appears, however, pretty clearly that they were not native to the climate; and what is most singular, the bones of the rein-deer, an animal now confined to the inhospitable regions of the north, are located with the remains of the inhabitants of the tropics. We must not, however, omit to notice, that many of the positions from which the bones of ruminantia have been taken, are not sufficiently verified to warrant us in deciding that they were contemporaneous

with the larger pachydermata last mentioned. Nay, we are even justified in believing many of them to have been postdiluvian.

In the osseous breccia of the Mediterranean have been found two species of lagomys, a genus confined to Siberia; two of rabbit, some campagnols, and rats as small as the water-rat and the mouse; and likewise in the English caverns; also the bones of shrews and lizards.

In the sandy strata of Tuscany the teeth of a porcupine have been found; and in Russia heads of a species of beaver, larger than any now known, and called trongotherium.

The remains of the edentata, above those of all other classes, indicate species of a size far superior to that of their existing congeners, and even of a magnitude altogether gigantic. Such was the megatherium, an animal partaking of the generic characters of the tardigrada and the armadillos, and equalling the rhinoceros in size. It has been found only in the sandy strata of North America. The megalonyx, found in the caverns of Virginia, and in a small island on the coast of Georgia, very much resembled the megatherium, but was not so large. Those two edentata were confined to America. But in Europe one appears to have existed, which, from a fragment remaining, has been considered as not less than four-and-twenty feet in length. This fragment was found in a sand-pit, in the district of Darmstadt, not far from the Rhine, among the bones of elephants, rhinoceroses, and tapirs.

In the osseous breccia are found, but very rarely, the bones of carnivora, which are, as we have seen, far more abundant in the caverns. Those of Germany are principally characterised by the remains of a very large species of bear, much surpassing any existing one in size, the ursus spelœus. There are two others, ursus arctoideus and ursus priscus. There is the fossil hyæna, differing, in some peculiarities of the teeth and head, from the Cape hyæna; two tigers, or panthers, a wolf, fox, glutton, genet, and some other small carnivora.

D 2

The bears are not very numerous in the loose strata. The ursus spelæus is said, however, to be found there, in Austria and Hainault. In Tuscany there is a peculiar species, remarkable for its compressed canines, thence termed U. Cultridens, or Angustidens. Hyænas are more frequently found in such strata, with the bones of the elephant and rhinoceros.

It appears, then, that during the era of which we are now speaking, the carnivorous order was numerous and powerful. The rodentia, smaller in general, and more feeble, have not so much attracted the attention of collectors of fossil remains. Still, as we have observed, it has presented us with some unknown species in the fossil state.

We have now enumerated the principal animals whose remains are found in the accumulation of earth, sand, and loam, which cover our large plains, and fill many caverns and fissures of rocks, and have been called diluvium. They decidedly constitute the population which occupied our part of the world, at the era of the last great catastrophe which destroyed their races, and prepared the soil on which the animals of our own era exist. Whatever resemblances certain of their species may present to those of our days, it cannot be denied that their general character was very different, and that most of their races have been annihilated.

It is, as we before remarked, most remarkable that in all the strata, and among all the fossil remains now enumerated, no relic has been found of man or monkey. Whether these kindred orders existed at all during the periods in question, or, if they did exist, where they existed, are points which it is yet impossible to decide. But what is quite certain is, that we are now surrounded by a fourth succession of terrestrial animals, and that, after the age of the reptiles, that of the palæotheria, and that of the mammoths, mastodons, and megatheria, the age arrived in which the human species, with the aid of certain domesticated animals, has appropriated and cultivated the earth; and it is only in alluvion, in peat, in recent concretions,

in a word, in such formations as have taken place since the last general inundation of the globe, that the bones of man and of existing animals have ever been discovered. To these are referrible the human skeletons, found incrusted in travertino, in the island of Guadaloupe. They are accompanied with shells and madrepores of the existing and surrounding seas. The remains of oxen, deer, &c., common in the peat-formations, are in the same predicament; as are likewise the bones of man and domestic animals embedded in alluvion, in ancient burying-grounds and fields of battle. To the era of the last general catastrophe, or to those of any preceding ages, none of these remains are attributable.

The mode in which the fossil bones have been determined, depends upon a principle in comparative anatomy, which regulates the co-existence of organic forms. Every animal may be considered as a whole, all the parts of which are in strict keeping and correspondence with each other. If the animal be carnivorous, it is characterised by a certain system of dentition. The teeth are trenchant, the jaws are powerful, and their condyles peculiarly formed. But such teeth and jaws would be of little service, unless the animal were also provided with claws adapted for seizing and tearing the prey. Claws of this kind necessitate a peculiar construction of the phalanges, a facility of rotation in the fore-arm, and corresponding changes in the humerus. Every animal whose stomach is constituted to digest nothing but flesh, must have every other part of his frame in consonance with this restriction. On the other hand, it is obvious that hoofed animals must be herbivorous, as they possess no means of seizing prey. Accordingly we find that their masticating and digestive organs correspond with this peculiarity. Their teeth are supplied with flat and unequal coronals, to bruise the herbage, &c., on which they feed; and as their system of dentition is generally less complete, so their stomachs are more complicated. This is not the place to enlarge