[page i]

A NEW

VOYAGE

AND

DESCRIPTION

OF THE

Isthmus of America,

Giving an Account of the

AUTHOR'S Abode there,

The Form and Make of the Country, the Coasts, Hills, Rivers, &c. Woods, Soil, Weather, &c. Trees, Fruit, Beasts, Birds, Fish, &c.

The Indian Inhabitants, their Features, Complexion, &c. their Manners, Customs, Employments, Marriages, Feasts, Hunting, Computation, Language, &c.

With Remarkable Occurrences in the South Sea, and elsewhere.

By LIONEL WAFER.

Illustrated with General Copper-Plates.

LONDON:

Printed for James Knapton, at the Crown in

St. Paul's Church yard, 1699.

[page ii]

[page iii]

To his Excellency, the Right Honourable

HENRY Earl of ROMNEY,

Viscount Sidney of Sheppey, and Baron of Milton in the County of Kent, Lord Lieutenant of the same, and of the City of Canterbury, Vice-Admiral of the same, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Constable of Dover Castle, Master of the Ordinance, Lieutenant-General of His Majesty's Forces, Collonel of His Majesty's own Regiment of Foot Guards, One of the Lords of His Majesty's Bed-Chamber, One of the Lords of His Majesty's most Honourable Privy Council; and One of the Lords Justices of England, during the Absence of His Majesty.

This Relation of his TRAVELS,

A 2

[page iv]

And Description of the ISTHUMS of AMERICA, is humbly Dedicated by

His Excellency's

Most Devoted

Humble Servant,

LIONEL WAFER.

[page v]

TO THE

READER.

THO' this Book bears partly the Name Cop ages, yet I shall here acquaint you before-hand, as I have hinted in the Book it self, That you are not to expect any Thing like a Compleat Journal, or Historical Account of all Occurrences in the Scene of my Travels. My principal Design was to give what Description I could of the Isthums of Darien, where I was left among the wild

[page vi]

Indians: And as for the preceding and subsequent Relations, I have, in them, only briefly represented the Course of my Voyages; without particularizing, any further, than to speak of a few Things I thought more especially remarkable. I cannot pretend to so great an Exactness, but that I may have fail'd in some Circumstances, especially in the Descriptional Part; which l leave to be made up by the longer Experience, and more accurate Observations of Others. But I have been as careful as I could: And tho there are some Matters of Fact that will seem strange, yet I have been more especially careful in these, to say nothing but what, according to the best of my Knowledge, is the very Truth. I

[page vii]

was but Young when I was abroad, and I kept no Journal; so that I may be dispenc'd with as to Defects and Failings of less moment. Yet I have not trusted altogether to my own Memory; but some Things I committed to Writing, long before I return'd to England; and have since been frequently comparing and rectifying my Notices, by Discoursing such of my Fellow-Travellers as I have met with in London. And 'tis even my Desire that the Reader, as he has Opportunity, would consult any of them, as to these Particulars; being not fond of having him take them upon my single Word. He will do both himself and me a Kindness in it; if he will be so Candid, withal, as to make me such Allowance

[page viii]

as the Premises call for: He will ease me of the Odium of Singularity; and himself of Doubt, or a Knowledge, it may be, too detective.

ERRATA.

PAge 4. 1. 27. read 4th.

p. 44. 1. 21. r. Chapters. There, p. 223.

p. 181. 1. 23. for Capital, r. Cardinal..

p. 195. 1. 16. r. Guaura.

[page ix]

[page x]

[page xi]

[page] 1

Mr. WAFER's Voyages; and Description of the Isthmus of America.

The A.s first Voyage.

Bantam.

lihor.

Malacca.

Jamby.

MY first going abroad was in the Great Ann of London, Capt. Zachary Browne Commander, bound for Bantam in the lsle of Java, in the East-Indies, in the Year 1677. I was in the Service of the Surgeon of the Ship; but being then very young, I made no great Observations in that Voyage. My Stay at Bantam was not above a Month, we being sent from thence to Jamby in the Isle of Sumatra. At that time there was a War between the Malayans of lihor on the Promontory of Malacca, and those of Jamby; and a Fleet of Proe's from lihore block'd up the Mouth of the River of Jamby. The Town of Jamby, is about 100 Mile up the River:

B

[page] 2

Quolla.

Barcadero.

But within 4 or 5 Mile of the Sea, it hath a Port Town on the River, consisting of about 15 or 20 Houses, built on Posts, as the Fashion of that Country is: The Name of this Port is Quolla; though this seems rather an Appellative than a proper Name, for they generally call a Port Quolla: And 'tis usual with our English Seamen in those Parts, when they have been at a Landing-place, to say they have been at the Quolla, calling it so in imitation of the Natives; as the Portuguese call their Landing-places, Barcadero's. This War was some hindrance to our Trade there; and we were forc'd to stay about 4 Months in the Road, before we could get in our Lading of Pepper: And thence we return'd to Bantam, to take in the rest of our Lading. While I was ashore there, the Ship sail'd for England: So I got a Passage home in another Ship, The Bombay, Capt. White Commander; who being Chief Mate, succeeded Capt. Bennet, who dy'd in the Voyage.

The A.'s 2d Voyage.

Jamaica.

Capt. Buckenham's hard Fortune.

I arrived in England again in the Year 1679 and after about a Months stay, I entred my self on a Second

[page] 3

Voyage, in a Vessel commanded by Capt. Buckenham, bound for the West-Indies. I was there also in the Service of the Surgeon of the Ship: But when we came to Jamaica, the Season of Sugars being not yet come, the Captain was willing to make a short Voyage, in the mean while, to the Bay of Campeachy, to fetch Logwood: But having no mind to go further with him, I staid in Jamaica. It proved well for me that I did so; for in that Expedition, the Captain was taken by the Spaniards, and carried Prisoner to Mexico: Where one Russel saw him, who was then also a Prisoner there, and after made his Escape. He told me he saw Capt. Buckenham, with a Log chain'd to his Leg, and a Basket at his Back, crying Bread about the Streets for a Baker his Master. The Spaniards would never consent to the Ransoming him, tho' he was a Gentleman who had Friends of a considerable Fortune, and would have given them a very large Sum of Mony.

The Angels Plantation.

Port Royal.

Cartagena

Golden-I.

Bastimento's.

Portobel.

Mr.Dampier.

Isthmus.

Santa Maria.

S. Seas.

Hist of the Buc.

I had a Brother in Jamaica, who was imployed under Sir Thomas Muddiford, in his Plantation at the Angels:

B 2

[page] 4

And my chief Inducement in undertaking this Voyage was to see him. I staid some time with him, and he settled me in a House at Port-Royal, where I followed my Business of Surgery for some Months. But in a while I met with Capt. Cook, and Capt. Linch, two Privateers, who were going out from Port-Royal, toward the Coast of Cartagena, and took me along with them. We met other Privateers on that Coast; but being parted from them by stress of Weather about Golden-Island, in the Samballoe's, we stood away to the Bastimento's, where we met them again, and several others, who had been at the taking of Portobel, and were Rendesvouzed there. Here I first met with Mr. Dampier, and was with him in the Expedition into the S. Seas. For in short, having muster'd up our Forces at Golden-Island, and landed on the Isthmus, we march'd over Land, and took Santa Maria; and made those Excursions into the S. Seas, which Mr. Ringrose relates in the 44th part of the History of the Buccaniers.

Mr.Dampier.

Capt. Sharp.

Isthmus.

Mr. Dampier has told, in his Introduction to his Voyage round the World,

[page] 5

in what manner the Company divided with reference to Capt. Sharp. I was of Mr. Dampier's side in that Matter, and of the number of those who chose rather to return in Boats to the Isthmus, and go back again a toilsom Journey over Land, than stay under a Captain in whom we experienc'd neither Courage nor Conduct. He hath given also an Account of what besel us in that Return, till such time as by the Carlesness of our Company, my Knee was so scorch'd with Gun-powder, that after a few Days further March, I was left behind among the Wild-Indians, in the Isthmus of Darien.

The A. left in the Isthmus.

His Knee burnt.

It was the 5th Day of our Journey when this Accident befel me; being also the 5th of May, in the Year 1681. I was fitting on the Ground near one of our Men, who was drying of Gun-powder in a Silver Plate: But not managing it as he should, it blew up, and scorch'd my Knee to that degree, that the Bone was left bare, the Flesh being torn away, and my Thigh burnt for a great way above it. I applied to it immediately such Remedies as I had in my Knapsack: And being unwilling to be left behind my

B 3

[page] 6

Companions, I made hard shift to jog on, and bear them Company for a few Days; during which our Slaves ran away from us, and among them a Negro whom the Company had allow'd me for my particular Attendant, to carry my Medicines. He took them away with him, together with the rest of my Things, and thereby left me depriv'd of wherewithal to dress my Sore; insomuch that my Pain increasing upon me, and being not able to trudge it further through Rivers and Woods, I took leave of my Company, and set up my Rest among the Darien Indians.

R. Gobson.

J. Hingson.

This was on the 10th Day; and there staid with me Mr. Richard Gopson, who had served an Apprenticeship to a Druggist in London. He was an ingenious Man, and a good Scholar; and had with him a Greek Testament which he frequently read, and would translate extempore into English to such of the Company as were dispos'd to hear him. Another who staid behind with me was John Hingson, Mariner: They were both so fatigued with the Journey, that they could go no further. There had been an Or-

[page] 7

der made among us at our first Landing, to kill any who should flag in the Journey: But this was made only to terrify any from loitering, and being taken by the Spaniards; who by Tortures might extort from them a Discovery of our March. But this rigorous Order was not executed; but the Company took a very kind Leave both of these, and of me. Before this we had lost the Company of two more of our Men, Robert Spratlin and William Bowman, who parted with us at the River Congo, the Day after my being scorch'd with Gun-powder. The Passage of that River was very deep, and the Stream violent; by which means I was born down the Current, for several Paces, to an Eddy in the bending of the River. Yet I got over; but these two being the hindmost, and feeing with what difficulty I cross'd the River, which was still rising, they were discourag'd from attempting it, and chose rather to stay where they were. These two came to me; and the other two soon after the Company's departure for the North-Sea, as I shall have occasion to mention; so that there were five of

B 4

[page] 8

us in all who were left behind among the Indians.

The Indians cure the A.

A kind Indian.

Being now forc'd to stay among them, and having no means to alleviate the Anguish of my Wound, the Indians undertook to cure me; and apply'd to my Knee some Herbs, which they first chew'd in their Mouths to the consistency of a Paste, and putting it on a Plantain-Leaf, laid it upon the Sore. This prov'd so effectual, that in about 20 Days use of this Poultess, which they applied fresh every Day, I was perfectly cured; except only a Weakness in that Knee, which remain'd long after, and a Benummedness which I sometimes find in it to this Day. Yet they were not altogether so kind in other respects; for some of them look'd on us very scurvily, throwing green Plantains to us, as we sat cringing and shivering, as you would Bones to a Dog. This was but sorry Food; yet we were forc'd to be contented with it: But to mend our Commons, the young Indian, at whose House we were left, would often give us some ripe Plantains, unknown to his Neighbours; and these were a great Re-

[page] 9

freshment to us. This Indian, in his Childhood, was taken a Prisoner by the Spaniards; and having liv'd some time among them, he had learn'd a pretty deal of their Language, under the Bishop of Panama, whom he ferv'd there; till finding means to escape, he was got again among his own Country-men. This was of good use to us; for we having a smattering of Spanish, and a little of the Indian's Tongue also, by passing their Country before, between both these, and with the additional use of Signs, we found it no very difficult Matter to understand one another. He was truly generous and hospitable toward us; and so careful of us, that if in the Day-time we had no other Provision than a few sorry green Plantains, he would rise in the Night, and go out by stealth to the Neighbouring Plantain-walk, and fetch a Bundle of ripe ones from thence, which he would distribute among us unknown to his Country-men. Not that they were naturally inclin'd to use us thus roughly, for they are generally a kind and free-hearted People; but they had taken some particular Offence, upon

[page] 10

the account of our Friends who left us, who had in a manner awed the Indian Guides they took with them for the remainder of their Journey, and made them go with them very much against their Wills; the Severity of the Rainy Season being then so great, that even the Indians themselves had no mind for Travelling, tho' they are little curious either as to the Weather or Ways.

R. Spratlin, W. Bowman.

G. Gainy's drowning.

A Consult to destroy the A. and his Companions.

When Gopson, Hingson, and I had lived 3 or 4 Days in this manner, the other two, Spratlin and Bowman, whom we left behind at the River Congo, on the 6th Day of our Journey, found their way to us; being exceedingly fatigued with rambling so long among the wild Woods and Rivers without Guides, and having no other Sustenance but a few Plantains they found here and there. They told us of George Gainy's Disaster, whose Drowning Mr. Dampier relates p. 17. They saw him lie dead on the Shore which the Floods were gone off from, with the Rope twisted about him, and his Mony at his Neck; but they were so fatigued, they car'd not to meddle with it. These, after their coming

[page] 11

up to us, continued with us for about a Fortnight longer, at the same Plantation where the main Body of our Company had left us; and our Provision was still at the same Rate, and the Countenances of the Indians as stern towards us as ever, having yet no News of their Friends whom our Men had taken as their Guides. Yet notwithstanding their Disgust, they still took care of my Wound; which by this time was pretty well healed, and I was enabled to walk about. But at length not finding their Men return as they expected, they were out of Patience, and seem'd resolved to revenge on us the Injuries which they suppos'd our Friends had done to theirs. To this end they held frequent Consultations how they should dispose of us: Some were for killing us, others for keeping us among them, and others for carrying us to the Spaniards, thereby to ingratiate themselves with them. But the greatest part of them mortally hating the Spaniards, this last Project was soon laid aside; and they came to this Resolution, To forbear doing any thing to us, till so much Time were expir'd as

[page] 12

they thought might reasonably be allow'd for the return of their Friends, whom our Men had taken with them as Guides to the North Sea-Coast; and this, as they computed, would be 10 Days, reckoning it up to us on their Fingers.

Preparations to kill them.

The Time was now almost expir'd, and having no News of the Guides, the Indians began to suspect that our Men had either murder'd them, or carried them away with them; and seem'd resolv'd thereupon to destroy us. To this end they prepared a great Pile of Wood to burn us, on the 10th Day; and told us what we must trust to when the Sun went down; for they would not execute us till then.

Lacenta saves them;

and sends them away.

But it so hapned that Lacenta, their Chief, passing that way, dissuaded them from that Cruelty, and proposed to them to send us down towards the North-side, and two Indians with us, who might inform themselves from the Indians near the Coast, what was become of the Guides. They readily hearken'd to this Proposal, and immediately chose two Me to conduct us to the North-side. One

[page] 13

of these had been all along an inveterate Enemy to us; but the other was that kind Indian, who was so much our Friend, as to rise in the Night and get us ripe Plantains.

Bad Travelling.

The next Day therefore we were dismissed with our two Guides, and marched Joyfully for 3 Days; being well assur'd we should not find that our Men had done any hurt to their Guides. The first three Days we march'd thro' nothing but Swamps, having great Rains, with much Thunder and Lightning; and lodg'd every Night under the dropping Trees, upon the cold Ground. The third Night we lodg'd on a small Hill, which by the next Morning was become an Island: For those great Rains had made such a Flood, that all the low Land about it was cover'd deep with Water. All this while we had no Provision, except a handful of dry Maiz our Indian Guides gave us the first two Days: But this being spent, they return'd home again, and left us to shift for our selves.

At this Hill we remained the fourth Day; and on the fifth the Waters being abated, we set forward,

[page] 14

steering North by a Pocket Compass, and marched till 6 a Clock at Night: At which time, we arrived at a River about 40 foot wide, and very deep. Here we found a Tree fallen cross the River, and so we believed our Men had past that way; therefore here we fat down, and consulted what course we should take.

They are bewilder'd.

Bowman like to be drown'd.

And having debated the Matter, it was concluded upon to cross the River, and seek the Path in which they had travelled: For this River running somewhat Northward in this place, we perswaded our selves we were past the main Ridge of Land that divided the North part of the Isthmus from the South; and consequently that we were not very far from the North Sea. Besides, we did not consider that the great Rains were the only cause of the sudden rising and falling of the River; but thought the Tide might contribute to it, and that we were not very far from the Sea. We went therefore over the River by the help of the Tree: But the Rain had made it so slippery, that 'twas with great difficulty that we could get over it astride, for there was no

[page] 15

walking on it: And tho' four of us got pretty well over, yet Bowman, who was the last, slipt off, and the Stream hurried him out of sight in a moment, so that we concluded he was Drown'd. To add to our Affliction for the loss of our Consort, we sought about for a Path, but found none; for the late Flood had fill'd all the Land with Mud and Oaze, and therefore since we could not find a Path, we returned again, and passed over the River on the same Tree by which we cross'd it at first; intending to pass down by the side of this River, which we still thought discharged it self into the North Sea. But when we were over, and had gone down with the Stream a quarter of a Mile, we espy'd our Companion sitting on the Bank of the River; who, when we came to him, told us, that the violence of the Stream hurry'd him thither, and that there being in an Eddy, he had time to consider where he was; and that by the help of some Boughs that hung in the Water, he had got out. This Man had at this time 400 pieces of Eight at his Back: He was a weakly Man, a Taylor by Trade.

[page] 16

Great Hardships.

Maccaw-berries.

Here we lay all Night; and the next Day, being the 5th of our present Journey, we march'd further down by the side of the River, thro' thickets of hollow Bamboes and Brambles, being also very weak for want of Food: But Providence susser'd us not to Perish, tho' Hunger and Weariness had brought us even to Death's door: For we found there a Maccaw Tree, which afforded us Berries, of which we eat greedily; and having therewith somewhat satisfied our Hunger, we carried a Bundle of them away with us, and continued our March till Night.

They are besetwith Rivers.

They mistake theirway.

The next Day being the 6th, we marched till 4 in the Afternoon, when we arrived at another River, which join'd with that we had hither to Coasted; and we were now inclos'd between them, on a little Hill at the Conflux of them. This last River was as wide and deep as the former; so that here we were put to a Nonplus, not being able to find means to Ford either of them, and they being here too wide for a Tree to go across, unless a greater Tree than we were able to cut down; having no Tool

[page] 17

with us but a Macheat or long Knife. This last River also we set by the Compass, and found it run due North: Which confirmed us in oun Mistake, that we were on the North side of the main Ridge of Mountains; and therefore we resolv'd upon making two Bark-logs, to float us down the River, which we unanimously concluded would bring us to the North Sea Coast. The Woods afforded us hollow Bamboes fit for our purpose; and we cut them into proper lengths, and tied them together with Twigs of a Shrub like a Vine, a great many on the top of one another.

Violent Rains.

By that time we had finished our Bark-logs it was Night, and we took up our Lodging on a small Hill, where we gathered about a Cart-load of Wood, and made a Fire, intending to set out with our Bark-logs the next Morning. But not long after Sun-set, it fell a Raining as if Heaven and Earth would meet; which Storm was accompanied with horrid Claps of Thunder, and such flashes of Lightning, of a Sulpherous smell, that we were almost stifled in the open Air.

C

[page] 18

Great Floods.

Thus it continued till 12 a Clock at Night; when to our great Terror, we could hear the Rivers roaring on both sides us; but 'twas so dark, that we could see nothing but the Fire we had made, except when a flash of Lightning came. Then we could see all over the Hill, and perceive the Water approaching us; which in less than half an hour carried away our Fire. This drove us all to our shifts, every Man seeking some means to save himself from the threatning Deluge. We also sought for small Trees to climb: For the place abounded with great Cotton Trees, of a prodigious bigness from the Root upward, and at least 40 or 50 foot clear without Branches, so that there was no climbing up them.

The A. climbs a Tree.

For my own part, I was in a great Consternation, and running to save my Life, I very opportunely met with a large Cotton Tree, which by some accident, or thro' Age, was become rotten, and hollow on one side; having a hole in it at about the height of 4 foot from the ground. I immediately got up into it as well as I could: And in the Cavity I found

[page] 19

a knob, which served me for a Stool; and there I sat down almost Head and Heels together, not having room enough to stand or sit upright. In this Condition I sat wishing for Day: But being fatigued with Travel, though very hungry withal, and cold, I fell asleep: But was soon awakned by the noise of great Trees which were brought down by the Flood; and came with such force against the Tree, that they made it shake.

He is beset with the Waters.

The Floods go off.

When I awoke, I found my Knees in the Water, though the lowest part of my hollow Trunk was, as I said, 4 foot above the ground; and the Water was running as swift, as if 'twere in the middle of the River. The Night was still very dark, but only when the flashes of Lightning came: Which made it so dreadful and terrible, that I forgot my Hunger, and was wholly taken up with praying to God to spare my Life. While I was Praying and Meditating thus on my sad Condition, I saw the Morning Star appear, by which I knew that Day was at hand: This cheared my drooping Spirits, and in

C 2

[page] 20

less than half an hour the Day began to dawn, the Rain and Lightning ceas'd, and the Waters abated, insomuch that by that time the Sun was up, the Water was gone off from my Tree.

Then I ventured out of my cold Lodging; but being stiff and the Ground slippery, I could scarce stand: Yet I made a shift ro ramble to the Place where we had made our Fire, but found no Body there. Then I call'd out aloud, but was answer'd only with my own Eccho; which struck such Terror into me, that I fell down as dead, being oppress'd both with Grief and Hunger; this being the 7th Day of our Fast, save only the Maccaw-berries before related.

He meets again with his Companions.

Being in this Condition, despairing of Comfort for want of my Consorts, I lay some time on the wet Ground, till at last I heard a Voice hard by me, which in some sort revived me; but especially when I saw it was Mr. Hingson, one of my Companions, and the rest found us presently after: Having all sav'd themselves by climbing small Trees. We greeted each o-

[page] 21

ther with Tears in our Eyes, and returned Thanks to God for our Deliverance.

The first thing we did in the Morning was to look after our Bark-logs or Rafts, which we had left tied to a Tree, in order to prosecute our Voyage down the River; but coming to the Place where we left them, we found them sunk and full of Water, which had got into the hollow of the Bamboes, contrary to our Expectation; for we thought they would not have admitted so much as Air, but have been like large Bladders full blown: But it seems there were Cracks in them which we did not perceive, and perhaps made in them by our Carelesness in working them; for the Vessels made of these Hollow Bamboe's, are wont to hold Water very well.

In danger of going among their Enemies.

River of Cheapo.

This was a new Vexation to us, and how to proceed farther we knew not; but Providence still directed all for the better: For if we had gone down this River, which we afterwards understood to be a River that runs into the River of Cheapo, and so towards the Bay of Panama and the South Sea, it would have carried us

C 3

[page] 22

into the midst of our Enemies the Spaniards, from whom we could expect no Mercy.

The Neighbourhood of the Mountains, and steepness of the Descent, is the cause that the Rivers rise thus suddenly after these violent Rains; but for the same reason they as suddenly fall again.

They are forc'd to return.

But to return to my Story, being thus frustrate of our Design of going down the Stream, or of crossing either of these Rivers, by reason of the sinking of our Bark-logs, we were glad to think of returning back to the Indian Settlement, and Coasted up the River side in the same Track we came down by. As our Hunger was ready to carry our Eyes to any Object that might afford us some Relief, it hapned that we espied a Deer fast asleep: Which we designed if possible to get, and in order to it we came so very near, that we might almost have thrown our selves on him: But one of our Men putting the Muzle of his Gun close to him, and the Shot not being wadded, tumbled out, just before the Gun went off, and did the Deer no hurt; but starting up at the noise,

[page] 23

he took the River and swam over. As long as our way lay by the River side, we made a shift to keep it well enough: But being now to take leave of the River, in order to seek for the Indians Habitation, we were much at a loss. This was the Eighth Day, and we had no Sustinence beside the Maccaw-Berries we had got, and the Pith of a Bibby-Tree we met with, which we split and eat very favourly.

They are in fear of the Indians.

The Indians receive them Kindly.

After a little Consideration what course to steer next, we concluded it best to follow the Track of a Pecary or Wild-Hog, hoping it might bring us to some old Plantain Walk or Potato Piece, which these Creatures often resort to, to look for Food: This brought us, according to our Expectation, to an old Plantation, and in fight of a new one. But here again Fear overwhelmed us, being between two straits, either to starve or venture up to the Houses of the Indians, whom being so near, we were now afraid of again, not knowing how they would receive us. But since there was no avoiding it, it was concluded that one should go up to the House, while the rest staid behind to

C 4

[page] 24

see the Issue. In conclusion I went to the Plantation, and it proved the same that we came from. The Indians were all amazed to see me, and began to ask many Questions: But I prevented them by falling into a Swoon, occasion'd by the heat of the House, and the scent of Meat that was boyling over the Fire. The Indians were very officious to help me in this Extremity, and when I revived, they gave me a little to eat. Then they enquired of me for the other four Men, for whom they presently sent, and brought all but Gobson, who was left a little further off, and treated us all very kindly: For our long expected Guides were now returned from the North side, and gave large Commendations of the kindness and generosity of our Men; by which means all the Indians were become now again our very good Friends. The Indian, who was so particularly kind to us, preceiving Mr. Gobson was not yet arrived at the Plantation, carried out Victuals to him, and after he was a little refresh'd with that, brought him up to us. So that now we were all together again, and had a great deal of care taken of us.

[page] 25

They setout again.

Here we stayed seven Days to refresh our selves, and then took our March again: For we were desirous to get to the North Seas as soon as we could, and they were now more willing to guide us than ever before; since the Guides our Party took with them, had not only been dismiss'd civilly, but with Presents also of Axes, Beads, &c. The Indians therefore of the Village where we now were, order'd four lusty young Men to conduct us down again to the River, over which the Tree was fallen, who going now with a good will, carried us thither in one Day; whereas we were three Days the first time in going thither. When we came thither, we marched about a Mile up the River, where lay a Canoa, into which we all Imbarked, and the Indians guided us up the same River which we before, thro' mistake, had strove to go down. The Indians padled stoutly against the Stream till Night, and then we Lodged at a House, where these Men gave such large Commendations of our Men, who were gone to the North Sea, that the Master of the House treated

[page] 26

us after the best manner. The next Day we set out again, with two Indians more, who made fix in all, to Row or Paddle us; and our Condition now was well altered.

In fix Days time after this, they brought us to Lacenta's House, who had before saved our Lives.

Lacenta's Palace.

Large Cotton Trees.

This House is situated on a fine little Hill, on which grows the statelieft Grove of Cotton Trees that ever I saw. The Bodies of these Trees were generally six foot in Diameter, nay, some eight, nine, ten, eleven; for four Indians and my self took hand in hand round a Tree, and could not fathom it by three foot. Here was likewise a stately Plantain Walk, and a Grove of other small Trees, that would make a pleasant artificial Wilderness, if Industry and Art were bestowed on it.

The Circumference of this pleasant little Hill, contains at least 100 Acres of Land; and is a Peninsula of an Oval form, almost surrounded with two great Rivers, one coming from the East, the other from the West; which approaching within 40 foot at each other, at the front of the Penin-

[page] 27

sula, separate again, embracing tin Hill, and meet on the other side, making there one pretty large River, which runs very swift. There is therefore but one way to come in toward this Seat; which, as I before observed, is not above 40 foot wide, between the Rivers on each side: and 'tis senced with hollow Bamboes, Popes-heads and Prickle pears, so thick set from one side the Neck of Land to the other, that 'tis impossible for an Enemy to approach it.

On this Hill live Fifty Principal Men of the Country, all under Lacenta's Command, who is as a Prince over all the South part of the Isthmus of Darien; the Indians both there and on the North side also, paying him great respect: but the South side is his Country, and this Hill his Seat Or Palace. There is only one Canoa belonging to it, which serves to ferry over Lacenta and the rest of them.

Lacenta keeps them with him.

When we were arrived at this; Place, Lacenta discharged our Guides, and sent them back again, telling us, That 'twas not possible for us to Travel to the North side at this Season; for the Rainy Season was now in

[page] 28

its height, and Travelling very bad; but told us we should stay with him, and he would take care of us: And we were forc'd to comply with him.

We had not been long here before an Occurrence happen'd, which tended much to the increasing the good Opinion Lacenta and his People had conceiv'd of us, and brought me into particular Esteem with them.

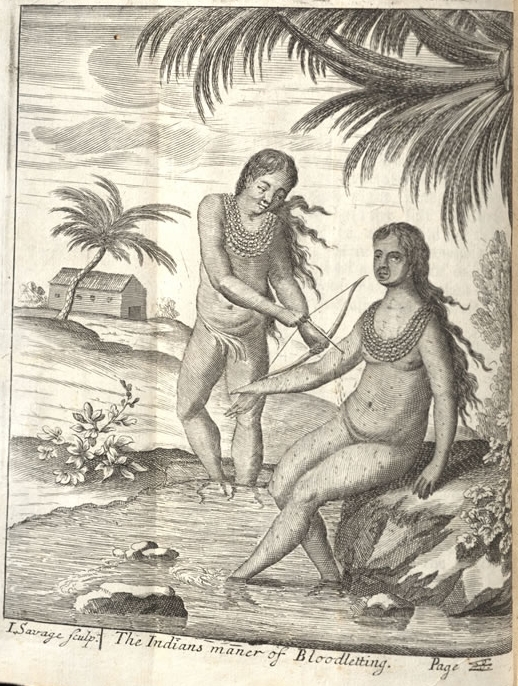

The Indians way of letting Blood.

It so happen'd, that one of Lacenta's Wives being indisposed, was to be let Blood; which the Indians perform in this manner: The Patient is seated on a Stone in the River, and one with a small Bow shoots little Arrows into the naked Body of the Patient, up and down; shooting them as fast as he can, and not missing any part. But the Arrows are gaged, so that they penetrate no farther than we generally thrust our Lancets: And if by chance they hit a Vein which is full of Wind, and the Blood spurts out a little, they will leap and skip about, shewing many Antick Gestures, by way of rejoycing and triumph.

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 29

The A. bleeds Lacenta's Queen.

The A. much reputed for this.

I was by while this was performing on Lacenta's Lady: And perceiving their Ignorance, told Lacenta, That if he pleased, I would shew him a better way, without putting the Patient to so much Torment. Let me see, says he; and at his Command, I bound up her Arm with a piece of Bark, and with my Lancet breathed a Vein: But this rash attempt had like to have cost me my Life. For Lacenta seeing the Blood issue out in a Stream, which us'd to come only drop by drop, got hold of his Lance, and swore by his Tooth, that if the did otherwise than well, he would have my Heart's Blood. I was not moved, but desired him to be patient, and I drew off about 12 Ounces, and bound up her Arm, and desired the might rest till the next Day: By which means the Fever abated, and the had not another Fit. This gained me so much Reputation, that Lacenta, came to me, and before all his Attendants, bowed, and kiss'd my Hand. Then the rest came thick about me, and some kissed my Hand, others my Knee, and some my Foot: After which I was taken up into a Ham-

[page] 30

mock, and carried on Men's Shoulders, Lacenta himself making a Speech in my Praise, and commending me as much Superiour to any of their Doctors. Thus I was carried from Plantation to Plantation, and lived in great Splendor and Repute, administring both Physick and Phlebotomy to those that wanted. For tho' I lost my Salves and Plaisters, when the Negro ran away with my Knapsack, yet I preserv'd a Box of Instruments, and a few Medicaments wrapt up in an Oil Cloth, by having them in my Pocket, where I generally carried them.

I lived thus some Months among the Indians who in a manner ador'd me. Some of these Indians had been Slaves to the Spaniards, and had made their Escapes; which I suppose was the cause of their expressing a desire of Baptism: but more to have a European Name given them, than for any thing they know of Christianity.

He goes on Hunting with Lacenta.

Gold River.

The way of gathering Gold.

Santa Maria.

The Gold carried to Santa Maria.

During my abode with Lacenta, I often accompanied him a Hunting, wherein he took great delight, here being good Game. I was one time, about the beginning of the dry Season,

[page] 31

accompanying him toward the South-East part of the Country, and we pass'd by a River where the Spaniards were gathering Gold. I took this River to be one of those which comes from the South-East, and runs into the Gulph of St. Michael. When we came near the Place where they wrought, we stole softly through the Woods, and placing our selves behind the great Trees, looked on them a good while, they not seeing us. The manner of their getting Gold it is as follows. They have little Wooden Dishes, which they dip softly into the Water, and take it up half full of Sand, which they draw gently out of the Water; and at every dipping they take up Gold mix'd with the Sand and Water, more or less. This they shake and the Sand riseth, and goes over the Brims of the Dish with the Water; but the Gold settles to the bottom. This done, they bring it out and dry it in the Sun, and then pound it in a Mortar. Then they take it out and spread it on Paper, and having a Load-stone they move that over it, which draws all the Iron, &c. from it, and then leaves the Gold

[page] 32

clean from Ore or Filth; and this they bottle up in Gourds or Calabashes. In this manner they work during the dry Season, which is three Months; for in the wet time the Gold is washed from the Mountains by violent Rains, and then commonly the Rivers are very deep; but now in the gathering Season, when they are fallen again, they are not above a Foot deep. Having spent the dry Season in gathering, they imbark in small Vessels for Santa Maria Town; and if they meet with good Success and a favourable Time, they carry with them, by Report, (for I learnt these Particulars of a Spaniard whom we took at Santa Maria under Captain Sharp) 18 or 20 thousand Pound o weight of Gold: But whether they gather more or less, 'tis incredible to report the store of Gold which is yearly wash'd down out of these Rivers.

During these Progresses l made with Lacenta, my four Companions staid behind at his Seat; but I had by this time so far ingratiated my self with Lacenta, that he would never go any where without me, and I plainly

[page] 33

perceiv'd he intended to keep me in this Country all the days of my Life; which raised some anxious Thoughts in me, but I conceal'd them as well as I could.

Pursuing our Sport one Day, it hapned we started a Pecary, which held the Indians and their Dogs in play the greatest part of the Day; till Lacenta was almost spent for want of Victuals, and was so troubled at his ill Success, that he impatiently wished for some better way of managing this sort of Game.

The A. moves for Leave to depart;

and 'tis granted.

I now understood their Language indifferent well, and finding what troubled him, I took this opportunity to attempt the getting my Liberty to depart, by commending to him our, English Dogs, and making an Offer of bringing him a few of them from England, if he would suffer me to go thither for a short time. He demurr'd at this Motion a while; but at length he swore by his Tooth, laying his Fingers on it, That I should have my Liberty, and for my Sake the other four with me; provided I would promise and swear by my Tooth, That I would return and marry among

D

[page] 34

them; for he had made me a Promise of his Daughter in Marriage, but she was not then marriageable. I accepted of the Conditions: And he further promised, that at my return he would do for me beyond my Expectation.

He returns towards Lacenta's House;

I returned him Thanks, and was the next Day dismissed under the Convoy of seven lusty Fellows; and we had four Women to carry our Provision, and my Cloaths, which were only a Linnen Frock and pair of Breeches. These I saved to cover my Nakedness, if ever I should come among Christians again; for at this time I went naked as the Salvages, and was painted by their Women; but I would not suffer them to prick my Skin, to rub the Paint in, as they use to do, but only to lay it on in little Specks.

and arrives there.

Thus we departed from the Neighbourhood of the South Seas, where Lacenta was Hunting, to his Seat or Palace, where I arrived in about 15 Days, to the great Joy of my Consorts; who had staid there, during this Hunting Expedition I made with Lacenta to the South-East.

[page] 35

After many Salutations on both sides, and some joyful Tears, I told them how I got my Liberty of Lacenta, and what I promised at my return: And they were very glad at the hopes of getting away, after so long a stay in a Savage Country.

He and the rest set out again for the N.Sea

I stayed here some few Days till I was refreshed, and then with my Companions, marched away for the North Seas; having a strong Convoy of armed Indians for our Guides.

The main Ridge of Hills.

We travelled over many very high Mountains; at last we came to one far surpassing the rest in height, to which we were four Days gradually ascending, tho' now and then with some Descent between whiles. Being on the top, I perceived a strange Giddiness in my Head; and enquiring both of my Companions, and the Indians, they all assured me they were in the like Condition; which I can only impute to the height of the Mountains, and the clearness of the Air. I take this part of the Mountains to have been higher than either that which we cross'd with Captain Sharp, or that which Mr. Dampier and the rest of our Party cross'd in their

D 2

[page] 36

return: For from this Eminence, the tops of the Mountains over which we passed before, seem'd very much below us, and sometimes we could not see them for the Clouds between; but when the Clouds flew over the tops of the Hill, they would break, and then we could discern them, looking as it were thro' so many Loop-holes.

I desired two Men to lie on my Legs, while I laid my Head over that side of the Mountain which was most perpendicular; but could see no Ground for the Clouds that were between. The Indians carried us over a Ridge so narrow that we were forced to straddle over on our Britches; and the Indians took the same Care of themselves, handing their Bows, Arrows, and Luggage, from one to another. As we descended, we were all cured of our Giddiness.

Indian Settlements.

When we came to the foot of the Mountain we found a River that ran into the North Seas, and near the side of it were a few Indian Houses, which afforded us indifferent good Entertainment. Here we lay one Night, it being the first House I had feen for

[page] 37

six Days; my Lodging, by the way, being in a Hammock made fast to two Trees, and my Covering a Plantain-Leaf.

They come to the Sea-side.

Indians in their Gowns.

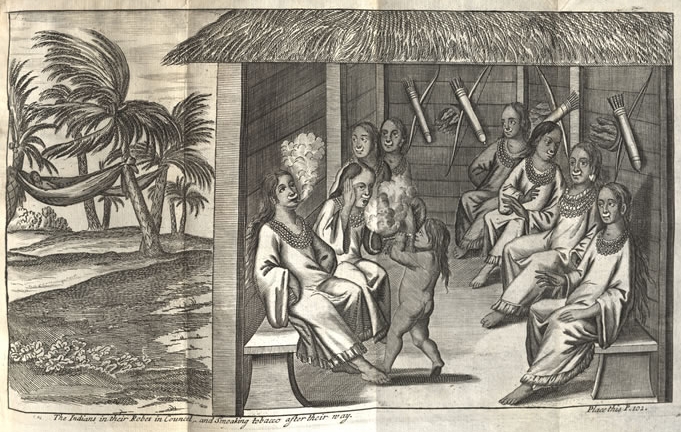

The next Morning we set forward, and in two Days time arrived at the sea-side, and were met by 40 of the best sort of Indians in the Country who congratuled our coming, and welcom'd us to their Houses. They were all in their finest Robes, which are long white Gowns, reaching to their Ancles, with Fringes at the bottom, and in their Hands they had Half Pikes. But of these Things, and such other Particulars as I observ'd during my Abode in this Country, I shall say more when I come to describe it.

The Indians fall to Conjuring

Pawawing.

The Answer made to the Conjuring.

We presently enquired of these Indians, when they expected any Ships? They told us they knew not, but would enquire; and therefore they sent for one of their Conjurers, who immediately went to work to raise the Devil, to enquire of him at what time a Ship would arrive here; for they are very expert and skilful in their sort of Diabolical Conjurations. We were in the House with them, and they

D 3

[page] 38

first began to work with making a Partition with Hammocks, that the pawawers, for so they call these Conjurers, might be by themselves. They continued some time at their Exercise, and we could hear them make most hideous Yellings and Shrieks; imitating the Voices of all their kind of Birds and Beasts. With their own Noise, they join'd that of several Stones struck together, and of Conch-shells, and of a sorry sort of Drums made of hollow Bamboes, which they beat upon; making a jarring Noise also with Strings fasten'd to the larger Bones of Beasts: And every now and then they would make a dreadful Exclamation, and clattering all of a sudden, would as suddenly make a Pause and a profound Silence. But finding that after a considerable Time no Answer was made them, they concluded that 'twas because we were in the House, and so turn'd us out, and went to Work again. But still finding no return, after an Hour or more, they made a new Search in our Apartment; and finding some of our Cloaths hanging up in a Basket against the Wall, they threw them out of Doors in great

[page] 39

Disdain. Then they fell once more to their Pawawing; and after a little time, they came out with their Answer, but all in a Muck-sweat; so that they first went down to the River and wash'd themselves, and then came and deliver'd the Oracle to us, which was to this Effect: That the 10th Day from that time there would arrive two Ships; and that in the Morning of the 10th Day we should hear first one Gun, and sometime after that another: That one of us should die soon after; and that going aboard we should lose one of our Guns: All which fell out exactly according to the Prediction.

2 Ships arriv'd

For on the 10th Day in the Morning we heard the Guns, first one, and then another, in that manner that was told us; and one of our Guns Fusees was lost in going aboard the Ships: For we five, and three of the Indians went off to the Ships in a Canoa; but as we cross'd the Bar of the River, it overset; where Mr. Gopson, one of my Consorts, was like to be drowned; and tho' we recover'd him out of the Water, yet he lost his Gun according to the Prediction.

D 4

[page] 40

I know not how this happen'd as to his Gun; but ours were all lash'd down to the side of the Canoa: And in the West-Indies we never go into a Canoa, which a little matter oversets, but we make fast our Guns to the Sides or Seats: And I suppose Mr. Gopson, who was a very careful and sensible Man, had lash'd down his also, tho' not fast enough.

They go off to the Ships.

Being overset, and our Canoa turn'd up-side down, we got to Shore as well as we could, and drag'd Mr. Gopson with us, tho' with difficulty. Then we put off again, and kept more along the Shore, and at length stood over to La Sounds Key, where the Ships lay, an English Sloop, and a Spanish Tartan, which the English had taken but two or three Days before. We knew by the make of this last that it was a Spanish Vessel, before we came up with it: But seeing it in Company with an English one, we thought they must be Consorts; and whether the Spanish Vessel should prove to be under the English one, or the English under that, we were resolv'd to put it to the venture, and get aboard, being quite tir'd with our

[page] 41

stay among the wild Indians. The Indians were more afraid of its being a Vessel of Spaniards, their Enemies as well as ours: For this was another Particular they told us 10 Days before, when they were Pawawing, that when their Oracle inform'd them that two Vessels would arrive at this time, they understood by their Dæmons Answer that one of them would be an English one; but as to the other, he spake so dubiously, that they were much afraid it would be a Spanish one, and 'twas not without great difficulty that we now persuaded them to go aboard with us: Which was another remarkable Circumstance; since this Vessel was not only a Spanish one, but actually under the Command of the Spaniards at the time of the Pawawing, and some Days after, till taken by the English.

They and the Indians receiv'd aboard.

The A. washes off his Paint.

Mr. Gopson dies.

The Indians return ashore.

They set Sail towards Cartagene

We went aboard the English Sloop, and our Indian Friends with us, and were received with a very hearty welcome. The four English Men with me were presently known and caress'd by the Ships Crew; but I sat a while cringing upon my Hams among the Indians, after their Fashi-

[page] 42

on, painted as they were, and all naked but only about the Waist, and with my Nose-piece (of which more hereafter) hanging over my Mouth. I was willing to try if they would know me in this Disguise; and 'twas the better part of an Hour before one of the Crew, looking more narrowly upon me, cry'd out, Here's our Doctor; and immediately they all congratulated my Arrival among them. I did what I could presently to wash off my Paint, but 'twas near a Month before I could get tolerably rid of it, having had my Skin so long stain'd with it, and the Pigment dried on in the Sun: And when it did come off, 'twas usually with the peeling off of Skin and all. As for Mr. Gopson, tho' we brought him alive to the Ship, yet he did not recover his Fatigues, and his drenching in the Water, but having languish'd aboard about three Days, he died there at La Sound's Key; and his Death verified another, part of the Pawawer's Prediction. Our Indians, having been kindly entertain'd aboard for about 6 or 7 Days; and many others of them, who went to and fro with their Wives and

[page] 43

Children, and Lacenta among the rest, visiting us about a Fortnight or three Weeks, we at length took leave of them, except 2 or 3 of them who would needs go with us to Windward; and weset Sail, with the Tartan in our Company, first to the more Eastern Isles of the Sambaloe's, and then towards the Coast of Cartagene.

The A.s Coasting about the W. Indies with Mr. Dampier.

and with Capt. Yanky. I. of Ash.

His Arrival in Virginia.

He goes into the S. Seas with Mr. Dampier;

and parts with him there.

This Relation discontinued, to describe the Isthmus.

But I shall not enter into the Discourse of our Voyage after this, Mr. Dampier, who was in the same Vessel, having done it particularly. It may suffice just to intimate, That I was cruising with him up and down the West-India Coast and Islands, partly under Capt. Wright, and partly under Capt. Yanky; till such time as Capt. Yanky left Mr. Dampier and the rest under Capt. Wright, at the Isle of Salt Tortuga, as Mr. Dampier relates in the 3d Chapter of his Voyage round the World, p. 58. I went then away and with Capt. Yanky; first to the Isle of Ash, where the French took us, as he relates occasionally, Chap. 4. p. 68. as also their turning us there ashore; our being taken in by Capt. Tristian, another French Man; his carrying us

[page] 44

with him almost to Petit-Guaves; our Men seizing the Ship when he was gone ashore, carrying it back to the Isle of Ash, and there taking in the rest of our Crew: The taking the French Ship with Wines, and the other in which Capt. Cook, who was then of our Crew, went afterwards to the South Seas, after having first been at Virginia: So that we arrived in Virginia with these Prizes about 8 or 9 Months after Mr. Dampier came thither. I set out with him also in that new Expedition to the South Seas under Capt. Cook, tho' he forgot to mention me in that part of his Voyages. We went round Terra del Fuego, and so up the South-Sea Coast, along Chili, Peru and Mexico, as he relates at large in his 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th Chapters, p. 223. There he tells how Capt. Davis, who had succeeded Capt. Cook at his Death, broke off Consortship with Capt. Swan, whom we had met with in the South Seas. That himself being desirous to stand over to the East-Indies, went aboard Capt. Swan: But I remain'd aboard the same Ship, now under Capt. Davis, and return'd with

[page] 45

him the way I came. Some few Particulars that I observ'd in that Return, I shall speak of at the Conclusion of this Book: In the mean while having given this Summary Account of the Course of my Travels, from my first parting with Mr. Dampier in the Isthmus, till my last leaving him in the South Seas, I shall now go on with the particular Description of the lsthmus of America, which was the main Thing I intended in publishing these Relations.

[page] 46

Mr. WAFER's Description of the Isthmus of America.

Isthmus Darien.

River of Darien.

Extent of the Isthmus.

Breadth.

Length.

THE Country I am going to describe is the narrowest part of the Isthmus of America, which is more peculiarly call'd the Isthmus of Darien; probably, from the great River of that Name, wherewith its Northern Coast is bounded to the East: For beyond this River the Land spreads so to the East and North-East, as that on the other Coast does to the South and South-Eaft, that it can no further be call'd an Isthmus. It is mostly comprehended between the Latitudes of 8 and 10 N. but its breadth, in the narrowest part, is much about one Degree. How far it reaches in length Westward under the Name of the Isthmus of Darien; whether as far as Honduras, or Nicaragua, or no further than the River Chagre, or the Towns of Portobel and Panama, I cannot say.

[page] 47

This last is the Boundary of what I mean to describe; and I shall be most particular as to the middle part even of this, as being the Scene of my Abode and Ramble in that Country: Tho' what I shall have occasion to say as to this part of the Isthmus, will be in some measure applicable to the Country even beyond Panama.

Bounds of what is strictly the Isthmus.

Its Situation.

Were I to fix particular Limits to this narrowest part of the American Isthmus, I would assign for its Western Term, a Line which should run from the Mouth of the River Chagre, where it falls into the North Sea, to the nearest part of the South Sea, Westward of Panama; including thereby that City, and Portobel, with the Rivers of Cheapo and Chagre. And I should draw a Line also from Point Garachina, or the South part of the Gulph of St. Michael, directly East, to the nearest part of the great River of Darien, for the Eastern Boundary, so as to take Caret Bay into the Isthmus. On the North and South it is sufficiently bounded by each of those vast Oceans: And considering that this is the narrowest Land that dif-

[page] 48

joins them, and how exceeding great the Compass is that must be fetch'd from one Shore to the other by Sea, since it has the North and South America, for each Extreme, 'tis of a very singular Situation, very pleasant and agreeable.

Islands on each side.

Bay of Panama.

Nor doth either of these Oceans fall in at once upon the Shore, but is intercepted by a great many valuable Islands, that lie scatter'd along each Coast: The Bastimento's and others, but especially the long Range of the Sambaloe's, on the North side; and the Kings or Pearl Islands, Perica and others in the Bay of Panama, on the South-side. This Bay is caus'd by the bending of the Isthmus: And for the bigness of it, there is not, it may be, a more pleasant and advantageous one any where to be found.

The Face of the Land.

Hills and vales.

Waters.

Main Ridge of Hills.

The Land of this Continent is almost every where of an unequal Surface, distinguish'd with Hills and Valleys, of great variety for heigth, depth, and extent. The Valleys are generally water'd with Rivers, Brooks, and Perennial Springs, with which the Country very much abounds. They fall some into the North, and

[page] 49

others into the South Sea; and do most of them take their Rise from a Ridge or Chain of higher Hills than the rest, running the length of the Isthmus, and in a manner parallel to the Shore; which for distinction's sake, I shall call the Main Ridge.

Fine Prospect.

Hills to the S. of the main Ridge.

This Ridge is of an unequal Breadth, and trends along bending as the Isthmus it self doth. 'Tis in most parts nearest the Edge of the North Sea, seldom above 10 or 15 Miles distant. We had always a fair and clear View of the North Sea from thence, and the various makings of the Shore, together with the adjacent Islands, render'd it a very agreeable Prospect; but the South Sea I could not see from any part of the Ridge. Not that the distance of it from the South Sea is so great, as that the Eye could not reach so far, especially from such an Eminence, were the Country between a Level or Champian: But tho' there are here and there Plains and Valleys of a considerable Extent, and some open Places, yet do they lie intermix'd with considerable Hills; and those too so cloath'd with tall Woods, that they

E

[page] 50

much hinder the Prospect there would the otherwise be. Neither on the other side is the main Ridge discern'd from that side, by reason of those Hills that lie between it and the South Sea; upon ascending each of which in our Return from the South Sea, we expected to have been upon the main Ridge, and to have seen the North Sea. And tho' still the further we went that way, the Hills we cross'd seemed the larger; yet, by this means, we were less sensible of the heigth of the main Ridge, than if we had climb'd up to it next way out of a low Country.

N. side all a Forrest.

On the North side of the main Ridge, there are either no Hills at all, or such as are rather gentle Declivities or gradual Subsidings of the Ridge, than Hills distinct from it: And tho' this side of the Country is every where covered with Woods, and more universally too, for it is all one continued Forrest, yet the Eye from that heigth commands the less distant Northern Shore with much Ease and Pleasure.

Breaks in the main Ridge.

R. Charge

Nor is the main Ridge it self carried on every where with a continued

[page] 51

Top; but is rather a Row or Chain of distinct Hills, than one prolonged: And accordingly hath frequent and large Valleys disjoining the several Eminencies that compose its length: And these Valleys, as they make even the Ridge it self the more useful and habitable, so are they some of them so deep in their Descent, as even to admit a Passage for Rivers. For thus the River Chagre, which rises from some Hills near the South Sea, runs along in an oblique North Westerly Course, till it finds it self a Passage into the North Sea; tho' the Chain of Hills, if I mistake not, is extended much farther to the West, even to the Lake of Nicaragua.

The Rivers, Brooks & Springs of the N. Coast.

R. of Darien.

River of Conception.

R. Charge.

The Rivers that water this Country are some of them indifferent large; tho' but few Navigable, as having Bars and Sholes at the Mouths. On the North Sea Coast the Rivers are for the most part very small; for rising generally from the main Ridge, which lies near that Shore, their Course is very short. The River of Darien is indeed a very large one; but the depth at the Entrance is not answerable to the wideness of its

E 2

[page] 52

Mouth, tho' 'tis deep enough further in: But from thence to Chagre, the whole length of this Coast, they are little better than Brooks: Nor is the River of Conception any other, which comes out over against La Sound's Key in the Sambaloe's. The River of Chagre is pretty considerable; for it has a long bending Coast, rising as it does from the South and East-part of the Isthmus, and at such a distance from its Outlet. But in general, the North Coast is plentifully water'd; yet is it chiefly with Springs and Rivulets trickling down from the Neighbouring Hills.

The Soil on this North Coast is various; generally 'tis good Land, rising in Hills; but to the Sea there are here and there Swamps, yet seldom above half a Mile broad.

The Soil by Caret Bay.

Inclusively from Caret Bay, which lies in the River of Darien, and is the only Harbour in it, to the Promontory near Golden lsland, the Shore of the Isthmus is indifferently fruitful, partly Sandy Bay; but part of it is drowned, swampy, Mangrove Land, where there is no goinga shore but up to the middle in Mud. The Shore of

[page] 53

this Coast rises in Hills presently; and the main Ridge is about 5 or 6 Miles distant. Caret Bay hath 2 or 3 Rivulets of fresh Water falling into it, as I am inform'd, for I have not been there. It is a little Bay, and two small Islands lying before it, make it an indifferent good Harbour, and hath clear Anchoring Ground, without any Rocks. These Islands are pretty high Land, cloathed with variety of Trees.

Bay near the Entrance of the R. of Darien.

I. in the Cod of the Bay.

Golden I.

Good Harbour.

To the Westward of the Cape at the Entrance of the River Darien, is another fine Sandy Bay. In the Cod of it lies a little, low, swampy Island; about which 'tis Shole-water and dirty Ground, not fit for Shipping; and the Shore of the Isthmus behind and about it, is swampy Land overgrown with Mangroves; till after three or four Mile the Land ascends up to the main Ridge. But though the Cod of this Bay be so bad, yet the Entrance of it is deep Water, and hard sandy bottom, excellent for anchoring; and has three Islands lying before it, which make it an extraordinary good Harbour. The Eastermost of those three is Golden Island,

E 3

[page] 54

a small one, with a fair deep Channel between it and the Main. It is rocky and steep all round to the Sea, (and thereby naturally fortified) except only the Landing-place, which is a small Sandy Bay on the South side, towards the Harbour, from whence it gently rises. It is moderately high, and cover'd with small Trees or Shrubs. The Land of the Isthmus opposite to it, to the South East, is excellent fruitful Land, of a black Mold, with Sand intermix'd; and is pretty level for 4 or 5 Mile, till you come to the foot of the Hills. At this Place we landed at our going into the South Seas with Capt. Sharp. I have been ashore at this Golden Island, and was lying in the Harbour near it for about a Fortnight together, before I went into the South Seas. Near the Eastern Point of the Bay, which is not above three or four Furlongs distant from Golden Island, there is a Rivulet of very good Water.

Another Island.

West of Golden Island lies the biggest of the three that face the Bay; it is, as a large low swampy Island, so beset with Mongroves, that it is difficult to go ashore; nor did any of us

[page] 55

care to attempt it, having no business in such bad Ground. It lies very near a Point of the Isthmus, which is such a sort of Ground too, for a Mile or two further Westward; and such also is the Ground on the other side, quite into the Cod of the Bay. This Island is scarce parted from the Isthmus but at High-water; and even then Ships cannot pass between.

Island of Pines.

The Island of Pines is a small Island to the North of the other two, making a kind of Triangle with them. It rises in two Hills, and is a very remarkable Land off at Sea. It is cover'd all over with good tall Trees, fit for any use; and has a fine Rivulet of fresh Water. The North of it is Rocky, as is the opposite Shore of the Isthmus. On the South side you go ashore on the Island at a curious Sand-bay, inclosed between two Points like a Half-moon; and there is very good Riding. You may sail quite round the Island of Pines; but to go to Golden Island Harbour, you must enter by the East-end of Golden Islands, between that and the Main; for there is no passing between it and the great low Island.

E 4

[page] 56

The Shore to Point Sanballas.

Tickle me quickly Harbour.

From these Islands, and the low swampy Point opposite to them, the shore runs North Westerly to Point Sanballas; and for the first 3 Leagues 'tis guarded with a Riffe of Rocks, some above, and some under Water, where a Boat cannot go ashore: The Rocks lie scatter'd unequally in breadth, for a Mile in some Places, in others two from the Shore. At the North West end of these Rocks, is a fine little Sandy Bay, with good anchoring and going ashore, as is reported by several Privateers: And the end of the Rocks on the one side, and some of the Sambaloes Islands (the Range of which begins from hence) on the other side, guard it from the Sea, and make it a very good Harbour. This, as well as the rest, is much frequented by Privateers; and is by those of our Country call'd Tickle me quickly Harbour.

Sambaloes Isles.

La Sound's key.

Springer's Key.

Trees in the Sambaloe's.

All along from hence to Point Sambaloes, ly the Sambaloes's Islands, a great multitude of them scattering in a Row, and collaterally too, at very unequal Distances, some of one, some two, or two Mile and an half, from the Shore, and from one another;

[page] 57

which, with the adjacent Shore, its Hills and perpetual Woods, make a lovely Landschape off at Sea. There are a great many more of these Islands than could well be represented in the Map; some of them also being very small. They seem to lie parcell'd out in Clusters, as it were; between which, generally, there are Navigable Channels, by which you may enter within them; and the Sea between the whole Range and the Isthmus is Navigable from end to end, and affords every where good anchoring, in hard Sandy Ground, and good Landing on the Islands and Main. In this long Channel, on the Inside of some or other of those little Keys or Islands, be the Winds how they will, you never fail of a good Place for any number of Ships to ride at; so that this was the greatest Rendezvous of the Privateers on this Coast; but chiefly La Sound's Key, or Springer's Key, especially if they stay'd any time here; as well because these two Islands afford a good Shelter for Careening, as because they yield Wells of fresh Water upon digging, which few of the rest do. The Sambaloe's

[page] 58

are generally low, flat, sandy Islands, cover'd with variety of Trees; [especially with Mammees, Sapadilloes, and Manchineel, &c. beside the Shellfish, and other Refreshments they afford the Privateers]. The outermost Keys toward the main Sea, are rocky on that side (and are called the Riffe Keys); tho' their opposite Sides are Sandy, as the innermost Keys or Islands are. And there is a Ridge also of Rocks lying off at Sea on the outside, which appear above Water at some half a Mile distance, and extend in length as far as La Sounds Key, if not further; and even the Sea between, and the Shore of the Sambaloes it self on that side, is all rocky.

Channel of the Sambaloes

R. of Conception and adjacent Coast.

Good Landing.

The long Channel between the Sambaloes and the Isthmus is of two, three, and four Miles breadth; and the Shore of the Isthmus is partly Sandy Bays, and partly Mangrove Land, quite to Point Sanballas. The Mountains are much at the same distance of 6 or 7 Miles from the Shore; but about the River of conception, which comes out about a Mile or two to the Eastward of La Sound's Key, the main Ridge

[page] 59

is somewhat further distant. Many little Brooks fall into the Sea on either side of that River, and the Outlets are some of them into the Sandy Bay, and some of them among the Mangrove Land; the Swamps of which Mangroves are (on this Coast) made by the Salt Water, so that the Brooks which come out there are brackish; but those in the Sandy Bay yield very sweet Water. None of those Outlets, not the River of Conception it self, are deep enough to admit any Vessel but Canoas, the Rivers on this part of the Coast being numerous but shallow; but the fine Riding in the Channel makes any other Harbour needless. I have been up and down most parts of it, and upon many of the Islands, and there the going ashore is always easy. But a Sea-wind makes a great Sea sometimes fall in upon the Isthmus, especially where a Channel opens between the Islands; so that I have been overset in a Canoa going ashore in one River, and in putting off to Sea from another. The Ground hereabouts is an excellent Soil within Land, rifing up gently to the main Ridge, and is a continued Forest of stately Timber-Trees.

[page] 60

Point Sanballas.

point Sanballas is a Rocky Point, pretty long and low, and is also so guarded with Rocks for a Mile off at Sea, that it is dangerous coming near it. From hence the Shore runs West, and a little Northerly, quite to Portobel. About three Leagues Westward from this Point lies Port Scrivan. The Coast between them is all Rocky, and the Country within Land all Woody, as in other Parts.

Port Scrivan.

Red Mangroves.

Port Scrivan is a good Harbour, when you are got into it; but the Entrance of it, which is scarce a Furlong over, is so beset with Rocks on each side, but especially to the East, that it is very dangerous, going in: Nor doth there seem to be a depth of Water sufficient to admit Vessels of any Bulk, there being in most Places but eight or nine Foot Water. The Inside of the Harbour goes pretty deep within the Land; and as there is good Riding, in a Sandy bottom, especially at the Cod of it, which is also fruitful Land, and has good fresh Water, so there is good Landing too on the East and South, where the Country is low for two or three Miles, and very firm Land; but the West-side is a Swamp

[page] 61

of Red Mangroves. It was here at this Swamp, as bad a Passage as it is, that Capt. Coxon, La Sound, and the other Privateers landed in the Year, 1679. when they went to take Portobel. They had by this means a very tedious and wearisome March; but they chose to land at this distance from the Town, rather than at the Bastimento's or any nearer Place, that they might avoid being discover'd by the Scouts which the Spaniards always keep in their Neighbourhood, and so might surprize them. And they did, indeed, by this means avoid being discern'd, till they came within an Hours march of the Town; tho' they travelled along the Country for five or six Days. The Spaniards make no use of this Port Scrivan; and unless a Privateer, or a rambling Sloop put in here by chance, no Vessel visits it in many Years.

Nombre de Dios.

From Port Scrivan to the Place where stood formerly the City of Nombre de Dios, 'tis further Westward about 7 or 8 Leagues. The Land between is very uneven, with small Hills, steep against the Sea; the Valleys between them water'd

[page] 62

with sorry little Rivers. The Soil of the Hills is Rocky, producing but small shrubby Trees; the Valleys are some of good Land, some of Swamps and Mangroves. The main Ridge here seems to lie at a good distance from the Sea; for it was not discernible in this March of the Privateers along the Shore to Portobel. The place where Nombre de Dios stood is the bottom of a Bay, close by the Sea, all over-grown with a sort of Wild-Canes, like those us'd by our Anglers in England. There is no Sign of a Town remaining, it is all so over-run with these Canes. The Situation of it seems to have been but very indifferent, the Bay before it lying open to the Sea, and affording little Shelter for Shipping; which I have heard was one Reason why the Spaniards forsook it: And another, probably, was the Unhealthiness of the Country it self, it being such low swampy Land, and very sickly; yet there is a little Rivulet of very sweet Water which runs close by the East-side of the Town. The Mouth of the Harbour is very wide; and tho' I have heard that there lie before it two

[page] 63

or three little Keys, or Rocks, yet they afforded no great Security to it. So that the Spaniards were certainly much in the right, for quitting this Place to settle at Portobel; which tho' it be also an unhealthy Place, yet has it the advantage of a very good and defensible Harbour.

I. Bastimento's.

2 other Isles.

About a Mile or two to the West-ward of these small Islands, at the Mouth of the Bay of Nombre de Dios, and about half a Mile or more from the Shore, lie a few Islands called the Bastimento's, for the most part pretty high, and one peeked, and all cloathed with Woods. On one of them, (part of which also was a Sandy Bay, and a good Riding and Landing place) there is a Spring of very good Water. I was ashore at this Island, and up and down among the rest of them; and all of them together make a very good Harbour between them and the Isthmus. The Bottom affords good Anchoring; and there is good coming in with the Sea-wind between the Eastermost Island and the next to it, and going out with the Land-wind the same way, this being the chief Passage. Further West, before you come to

[page] 64

Portobel, lie two small Islands, flat and without Wood or Water. They are pretty close together; and one of them I have been ashore upon. The Soil is sandy, and they are environ'd with Rocks towards the Sea; and they lie so near the Isthmus that there is but a very narrow Channel between, not fit for Ships to come into.

The Neighbouring Shore of the Isthmus.

Spanish Indians.

The Shore of the Isthmus hereabouts consists mostly of Sandy Bays, after you are past a Ridge of Rocks that run out from the Bay of Nombre de Dios, pointing towards the Bastimento's. Beyond the Bastimento's to Portabel, the Coast is generally Rocky. Within Land the Country is full of high and steep Hills, very good Land; most Woody, unless where clear'd for Plantations by Spanifh Indians, tributary to Portobel, whither they go to Church. And these are the first Settlements on this Coast under the Spanish Government, and lie scattering in lone Houses or little Villages, from hence to Portobel and beyond; with some Look-outs or Watches kept towards the Sea, for the Safety of the Town. In all the rest of the North-

[page] 65

side of the Isthmus, which I have describ'd hitherto, the Spaniards had neither Command over the Indians, nor Commerce with them while I was there, though there are Indians inhabiting all along the Continent; yet one has told me since, that the Spaniards have won them over to them.

Portobel.

The Harbour.

The Forts.

The Town.

Road to Panama.

The K'.s Stable.

The Governours House.

Rivulet.

Bad Air.

Portobel is a very fair, large and commodious Harbour, affording good Anchoring and good Shelter for Ships, having a narrow Mouth, and spreading wider within. The Galleons from Spain find good Riding here during the time of their Business at Portobel, for from hence they take in such of the Treasures of Peru as are brought thither over Land from Panama. The Entrance of this Harbour is fecur'd by a Fort upon the left Hand going in; it is a very strong one, and the Passage is made more secure by a Block-house on the other side, opposite to it. At the bottom of the Harbour lies the Town, bending along the Shore like a Half-moon: In the middle of which upon the Sea, is another small low Fort, environ'd with Houses except only to the Sea: And

F

[page] 66

at the West end of the Town, about a Furlong from the Shore, upon a gentle Rising, lies another Fort, pretty large and very strong, yet overlook'd by a Neighbouring Hill further up the Country, which Sir Henry Morgan made use of to take the Fort. In all these Forts there may be about 2 or 300 Spanish Souldiers in Garison. The Town is long and narrow, having two principal Streets besides those that go across; with a small Parade about the middle of it, surrounded with pretty fair Houses. The other Houses also and Churches are pretty handsome, after the Spanish make. The Town lies open to the Country without either Wall or Works; and at the East-side of it, where the Road to Panama goes out, (because of Hills, that lie to the Southward of the Town, and obstruct the direct Passage) there lies a long Stable, running North and South from the Town, to which it joins. This is the King's Stable for the Mules that are imployed in the Road betwixt this and Panama. The Governours House is close by the great Fort, on the same Rising, at the West of the Town.

[page] 67

Between the Parade in the middle of the Town, and the Governours House, is a little Creek or Brook, with a Bridge over it; and at the East-end, by the Stable, is a small Rivulet; of fresh Water. I have already said that it is an unhealthy Place. The East-side is low and swampy; and the Sea at low Water leaves the Shore within the Harbour bare, a great way from the Houses; which having a black filthy Mud, it stinks very much, and breeds noisome Vapours, thro' the Heat of the Climate. From the South and the East-sides the Country rises gently in Hills, which are partly Woodland and partly Savannah; but there is not any great Store either of Fruit-trees or Plantations near the Town. This Account I have had from several Privateers just as they return'd from Portobel; but I have not been there my self.

The Coast hence to R. Chagre.

The Country beyond this West-ward, to the Mouth of the River Chagre, I have seen off at Sea: But not having been ashore there, I can give no other Account of it, but only that it is partly Hilly, and near the Sea very much Swampy; and I have

F 2

[page] 68

heard by several that there is no Communication between Portobel and the Mouth of that River.

Bocca Toro & Bocca Drago.

I have been yet further Westward on this Coast, before I went over the Isthmus with Capt. Sharp, ranging up and down and careening at Bocca Toro and Bocca Drago; but this is with out the Verge of those Bounds I have set my self.

The S. Sea Coast of the Isthmus.

Having thus Survey'd the North-Coast of the lsthmus, I shall take a light View of the South also: But I shall the less need to be particular in it, because Mr. Dampier hath in some measure describ'd this part of it in his Voyage round the World.

Point Garachina.

Cape st. Lorenzo.

To begin therefore from Point Garachina, which makes the West-side of the Mouth of the River of Sambo, this Point is pretty high fast Land; but within, towards the River, it is low, drowned Mangrove, and so are all the Points of Land to Cape Saint Lorenzo.

R.Sambo.

Gulph of S. Michael

Gold R.

The River of Sambo I have not seen; but it is said to be a pretty large River. Its Mouth opens to the North; and from thence the Coast bears North East to the Gulph of St. Michael.

[page] 69