[page 361]

AN

ACCOUNT

OF A

VOYAGE round the WORLD,

IN THE YEARS

MDCCLXVI, MDCCLXVII, and MDCCLXVIII.

By SAMUEL WALLIS, Efq;

Commander of his Majesty's Ship the DOLPHIN.

VOL. I. A a a

[page break]

[page 363]

CHAP. I.

The Passage to the coast of Patagonia, with some account of the Natives.

[The longitude in this voyage is reckoned from the meridian of London.]

1766. June 19.

HAVING received my commission, which was dated the 19th of June 1766, I went on board the same day, hoisted the pendant, and began to enter seamen, but, according to my orders, took no boys either for myself or any of the officers.

Sat. July 26.

Sat. Aug. 16.

The ship was fitted for the sea with all possible expedition, during which the articles of war, and the act of parliament were read to the ship's company: on the 26th of July we failed down the river, and on the 16th of August, at eight o'clock in the morning, anchored in Plymouth Sound.

Tuesday 19.

On the 19th I received my failing orders, with directions to take the Swallow sloop, and the Prince Frederick store-ship under my command: and this day I took on board, among other things, three thousand weight of portable soup, and a bale of cork jackets. Every part of the ship was filled with stores and necessaries of various kinds, even to the steerage and state-room, which were allotted to the slops and portable soup. The surgeon offered to purchase an extraordinary quantity of medicines, and medical necessaries, which, as the ship's company might become sickly,

A a a 2

[page] 364

1766. August.

he said would in that case be of great service, if room could be found to stow them in; I therefore gave him leave to put them into my cabbin, the only place in the ship where they could be received, as they consisted of three large boxes.

Friday 22.

On the 22d, at four o'clock in the morning, I weighed and made sail in company with the Swallow and Prince Frederick, and had soon the mortification to find that the Swallow was a very bad sailer.

September.

Sunday 7.

We proceeded in our voyage, without any remarkable incident, till Sunday the seventh of September, when, about eight o'clock in the morning, we saw the island of Porto Santo, bearing west; and about noon saw the east-end of the island of Madeira.

About five o'clock we ran between this end of the island and the Deserters. On the side next the Deserters is a low flat island, and near it a needle rock; the side next to Madeira is full of broken rocks, and for that reason it is not safe to come within less than two miles of it.

Monday 8.

At six in the evening we anchored in Madeira Road, about two-thirds of a mile from the shore, in 24 fathom with a muddy bottom: about eight the Swallow and Prince Frederick also came to an anchor; and I sent an officer on shore to the Governor, to let him know that I would salute him, if he would return an equal number of guns, which he promised to do; the next morning therefore, at fix o'clock, I saluted him with thirteen guns, and he returned thirteen as he had promised.

Friday 12.

Having taken in a proper quantity of water at this place, with four pipes and ten puncheons of wine, some fresh beef, and a large quantity of onions, we weighed anchor on the 12th, and continued our voyage.

[page] 365

1766. September.

Tuesday 16.

At six o'clock in the morning, of Tuesday the 16th, we saw the island of Palma, and found the ship 15 miles to the southward of her reckoning. As we were sailing along this island, at the rate of no less than eight miles an hour, with the wind at east, it died away at once; so that within less than two minutes the ship had no motion, though we were at least four leagues distant from the shore. Palma lies in lat. 28° 40′N. long. 17° 48′W.

Saturday 20.

On the 20th we tried the current, and found it set S. W. by W. one mile an hour: this day we saw two herons flying to the eastward, and a great number of bonettos about the ship, of which we caught eight.

Sunday 21.

Monday 22.

Tuesday 23.

In the night between the 21st and 22d we lost our companion the Swallow, and about eight in the morning we saw the island of Sal, bearing S. ½ W.; at noon it bore S. ¾ W. distant 8 leagues; and at noon on the 23d, the nearest land of the island of Bonavista bore from S. to W. S. W. distant seven or eight miles, the east-end, at the same time, bearing W. distant two leagues. In this situation we founded, and had only 15 fathom, with rocky ground; at the same time we saw a very great rippling, which we supposed to be caused by a reef, stretching off the point about E. S. E. three miles, and breakers without us, distant also about three miles in the direction of S. E. We steered between the rippling and the breakers, but after hauling the ship off about half a mile, we had no soundings. The Prince Frederick passed very near the breakers, in the S. E. but had no soundings; yet these breakers are supposed to be dangerous. The middle of the isle of Sal is in lat. 16° 55′N. long. 21° 59° W.; the middle of Bonavista is in lat. 16° 10′long. 23° W.

[page] 366

1766. September.

Wedn. 24.

On the next day, at six in the morning, the isle of May bore from W. to S. W. six leagues; and soon after the Swallow again joined company. At half an hour after 10 the west-end of the isle of May bore north at the distance of five miles, and we found a current here, setting to the south-ward at the rate of twenty miles in four and twenty hours. The latitude of this island is 15° 10′N. longitude 22° 25′W.

Thurs. 25.

At noon the south-end of the island St. Iago bore S. W. by W. distant four leagues; and the north-end N. W. distant five leagues. At half an hour after three we anchored in Port Praya, in that island, in company with the Swallow and Prince Frederick, in eight fathom water, upon sandy ground. We had much rain and lightning in the night, and early in the morning I sent to the commanding-officer at the fort, for leave to get off some water, and other refreshments, which he granted.

We soon learnt that this was the sickly season, and that the rains were so great as to render it extremely difficult to get any thing down from the country to the ships: it happened also, unfortunately, that the small-pox, which is extremely fatal here, was at this time epidemic; so that I permitted no man to go ashore who had not had that distemper, and I would not suffer even those that had to go into any house.

We procured, however, a supply of water and some cattle from the shore, and caught abundance of fish with the seine, which was hauled twice every day: we found also in the valley where we got our water, a kind of large purslain, growing wild in amazing quantities: this was a most welcome refreshment both raw as a sallad, and boiled with the

2

[page] 367

1766. September.

broth and pease; and when we left the place we carried away enough of it to serve us a week.

Sunday 28.

On the 28th, at half an hour after twelve we weighed and put to sea; at half an hour after six in the evening the peak of Fuego bore W. N. W. distant 12 leagues, and in the night the burning mountain was very visible.

This day I ordered hooks and lines to be served to all the ship's company, that they might catch fish for themselves; but at the same time I also ordered that no man should keep his fish more than four and twenty hours before it was eaten, for I had observed that stale, and even dried fish, had made the people sickly, and tainted the air in the ship.

October.

Wednes. 1.

Friday 3.

Tuesday 7.

On the first of October, in lat. 10° 37′N. we lost the true trade-wind, and had only light and variable gales; and this day we found that the ship was set twelve miles to the northward by a current; on the third we found a current run S. by E. at the rate of six fathom an hour, or about twenty miles and a half a day: on the seventh we found the ship 19 miles to the southward of her reckoning.

Monday 20.

On the 20th, our butter and cheese being all expended, we began to serve the ship's company with oil, and I gave orders that they should also be served with mustard and vinegar once a fortnight during the rest of the voyage.

Wednes. 22.

On the 22d we saw an incredible number of birds, and among the rest a man of war bird, which inclined us to think that some land was not more than 60 leagues distant: this day we crossed the equator in longitude 23° 40′W.

Friday 24.

Sunday 26.

On the 24th I ordered the ship's company to be served with brandy, and reserved the wine for the sick and convalescent. On the 26th the Prince Frederick made signals of distress, upon which we bore down to her, and found than she had

[page] 368

1766. October.

carried away her fore-top-sail-yard. To supply this loss we gave her our sprit-sail-top-sail-yard, which we could spare, and she hoisted it immediately.

Monday 27.

On the 27th the again made signals of distress, upon which I brought to, and sent the carpenter on board her, who returned with an account that she had sprung a leak under the larboard cheek forward, and that it was impossible to do any thing to it till we had better weather. Upon speaking with Lieutenant Brine, who commanded her, he informed me that his crew were sickly; that the fatigue of working the pumps, and constantly standing by the sails, had worn them down; that their provisions were not good, that they had nothing to drink but water, and that he feared it would be impossible for him to keep company with me except I could spare him some assistance. For the badness of their provision I had no remedy, but I sent on board a carpenter and fix seamen to assist in pumping and working the ship.

November.

Saturday 8.

On the eighth of November, being in latitude 25° 52′S. longitude 39° 38′we sounded with 160 fathom, but had no ground: on the ninth, having seen a great number of birds, called albatrosses, we founded again with 180 fathom, but had no ground.

Tuesday 11.

On the 11th, having by signal brought the store-ship under our stern, I sent the carpenter, with proper assistants, on board to stop the leak; but they found that very little could be done: we then compleated our provisions, and those of the Swallow, from her stores, and put on board her all our staves, iron hoops, and empty oil jars. The next day I sent a carpenter and six seamen to relieve the men that had been sent to assist her on the 27th of October, who, by this time, began to suffer much by their fatigue. Several of her crew having the appearance of the scurvy, I sent

3

[page] 369

1766. November.

the surgeon on board her with some medicines for the sick. This day, having seen some albatrosses, turtles, and weeds, we founded, but had no ground with 180 fathom.

Wednes. 12.

On the 12th, being now in latitude 30 south, we began to find it very cold; we therefore got up our quarter cloths, and fitted them to their proper places, and the seamen put on their thick jackets. This day we saw a turtle, and several albatrosses, but still had no ground with 180 fathom.

Tuesday 18.

We continued to see weeds and birds on board the ship, but had no ground till the 18th, when we found a soft muddy bottom at the depth of 54 fathom. We were now in lat. 35° 40′S. long. 49° 54′W.; and this was the first sounding we had after our coming upon the coast of Brazil.

Wednes. 19.

Thursday 20.

On the 19th, about eight o'clock in the evening, we saw a meteor of a very extraordinary appearance in the northeast, which, soon after we had observed it, flew off in a horizontal line to the south-west, with amazing rapidity: it was near a minute in its progress, and it left a train of light behind it so strong, that the deck was not less illuminated than at noon-day. This day we saw a great number of seals about the ship, and had soundings at 55 fathom, with a muddy bottom. The next day the seals continued, and we had soundings at 53 fathom, with a dark coloured sand; upon which we bent our cables.

Friday 21.

On the 21st we had no ground with 150 fathom. Our lat. at noon was 37° 40′S. long. 51° 24′W.

Saturday 22.

On the 22d we had soundings again at 70 fathom, with a dark brown sand, and saw many whales and seals about the ship, with a great number of butterflies, and birds, among which were snipes and plover. Our lat. at noon was 38° 55′long. 56° 47′W.

VOL. I. B b b

[page] 370

1766. December.

Monday 8.

Tuesday 9.

Our soundings continued from 40 to 70 fathom, till the eighth of December, when, about six o'clock in the morning, we saw land bearing from S. W. to W. by S. and appearing like many small islands. At noon it bore from W. by S. to S. S. W. distant 8 leagues; our latitude then being 47° 16′S. long. 64° 58′W. About three o'clock Cape Blanco bore W. N. W. distant six leagues, and a remarkable double saddle W. S. W. distant about three leagues. We had now soundings from 20 to 16 fathom, sometimes with coarse sand and gravel, sometimes with small black stones and shells. At eight in the evening the Tower rock at Port Desire bore S. W. by W. distant about three leagues; and the extreams of the land from S. by E. to N. W. by N. At nine, Penguin Island bore S. W. by W. ½ W. distant two leagues; and at four o'clock in the morning of the ninth, the land seen from the masthead bore from S. W. to W. by N.

At noon Penguin island bore S. by E. distant 57 miles; our latitude being 48° 56′S. longitude 65° 6′W. This day we saw such a quantity of red shrimps about the ship, that the sea was coloured with them.

Wednes. 10.

At noon the next day, Wednesday the 10th, the extreams of the land bore from S. W. to N. W. and Wood's Mount, near the entrance of Saint Julian's, bore S. W. by W. distant three or four leagues. Our latitude was 49° 16′S. our longitude 66° 48′W.; and our soundings were from 40 to 45 fathom, sometimes sine sand, sometimes soft mud.

Tuesday 11.

At noon, on Thursday the 11th, Penguin island bore N. N. E. distant 58 leagues. Our latitude was 50° 48′S. our longitude 67° 10′W.

Saturday 13.

We continued our course till Saturday the 13th, when our latitude being 50° 34′S. and our longitude 68° 15′W.

2

[page] 371

1766. December.

the extreams of the land bore from N. ½ E. to S. S. W. ½ W. and the ship was about five or six miles distant from the shore. Cape Beachy-head, the northermost cape, was found to lie in latitude 50° 16′S. and Cape Fairweather, the southermost cape, in latitude 50° 50′S.

Sunday 14.

On Sunday the 14th, at four in the morning, Cape Beachy-head bore N. W. ½ N. distant about eight leagues; and at noon, our latitude being 50° 52′S. and longitude 68° 10′W. Penguin island bore N. 35° E. distant 68 leagues. We were six leagues from the shore, and the extreams of the land were from N. W. to W. S. W.

Monday 15.

Tuesday 16.

At eight o'clock in the morning, of Monday the 15th, being about six miles from the shore, the extreams of the land bore from S. by E. to N. by E. and the entrance of the river Saint Croix S. W. ½ W. We had 20 fathom quite cross the opening, the distance from point to point being about seven miles, and afterwards keeping at the distance of about four miles from each cape, we had from 22 to 24 fathom. The land on the north shore is high, and appears in three capes; that on the south shore is low and flat. At seven in the evening, Cape Fairweather bore S. W. ½ S. distant about four leagues, a low point running out from it S.S.W. ¾ W. We stood off and on all night, and had from 30 to 22 fathom water, with a bottom of sand and mud. At seven the next morning, Tuesday the 16th, we shoaled gradually into 12 fathom, with a bottom of sine sand, and soon after into six: we then hauled off S. E. by S. somewhat more than a mile; then steered east five miles, then E. by N. and deepened into 12 fathom. Cape Fairweather at this time bore W. ½ S. distant four leagues, and the northermost extremity of the land W. N. W. When we first came into shoal water, Cape Fairweather bore W. ½ N. and a low point without it W. S. W.

B b b 2

[page] 372

1766. December.

distant about four miles. At noon Cape Fairweather bore W. N. W. ½ W. distant six leagues, and a large hummock S. W. ½ W. distant seven leagues. At this time our lat. was 51° 52′S. long. 68° W.

At one o'clock, being about two leagues distant from the shore the extreams of three remarkable round hills bore from S. W. by W. to W. S. W. At four, Cape Virgin Mary bore S. E. by S. distant about four leagues. At eight, we were very near the Cape, and upon the point of it saw several men riding, who made signs for us to come on shore. In about half an hour we anchored in a bay, close under the south side of the Cape, in ten fathom water, with a gravelly bottom. The Swallow and store-ship anchored soon after between us and the Cape, which then bore N. by W. ½ W. and a low sandy point like Dungeness S. by W. From the Cape there runs a shoal, to the distance of about half a league, which may be easily known by the weeds that are upon it. We found it high water at half an hour after eleven, and the tide rose twenty foot.

Wednes. 17.

The natives continued abreast of the ship all night, making several great fires, and frequently shouting very loud. As soon as it was light, on Wednesday morning the 17th, we saw great numbers of them in motion, who made signs for us to land. About five o'clock I made the signal for the boats belonging to the Swallow and the Prince Frederick to come on board, and in the mean time hoisted out our own. These boats being all manned and armed, I took a party of marines, and rowed towards the shore, having left orders with the master to bring the ship's broad-side to bear upon the landing place, and to keep the guns loaded with round shot. We reached the beach about six o'clock, and before we went from the boat, I made signs to the natives to retire

[page] 373

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

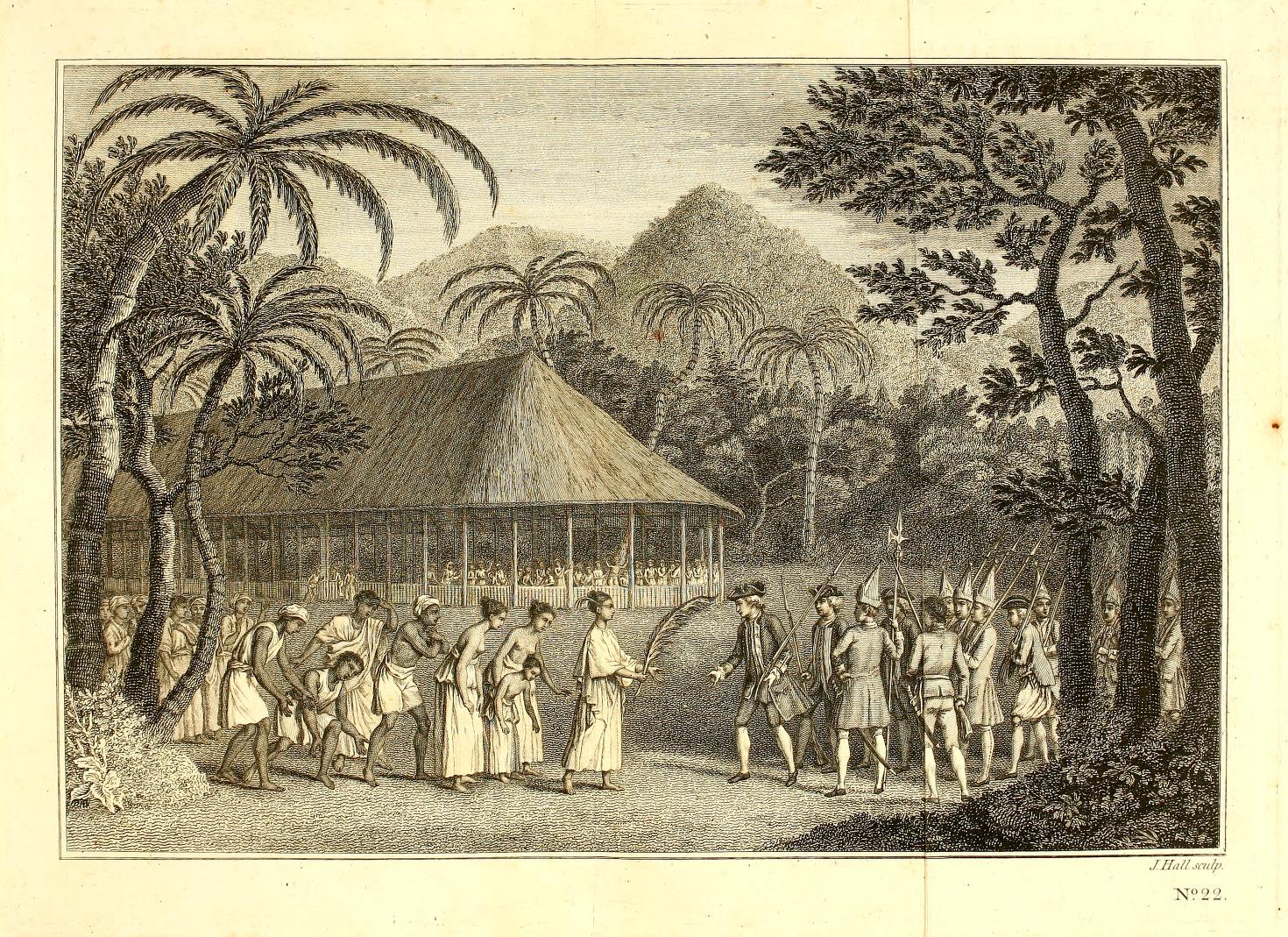

to some distance: they immediately complied, and I then landed with the captain of the Swallow, and several of the officers: the marines were drawn up, and the boats were brought to a grappling near the shore. I then made signs to the natives to come near, and directed them to sit down in a semicircle, which they did with great order and chearfulness. When this was done, I distributed among them several knives, scissars, buttons, beads, combs, and other toys, particularly some ribands to the women, which they received with a very becoming mixture of pleasure and respect. Having distributed my presents, I endeavoured to make them understand that I had other things which I would part with, but for which I expected somewhat in return. I shewed them some hatchets and bill-hooks, and pointed to some guanicoes, which happened to be near, and some ostriches which I saw dead among them; making signs at the same time that I wanted to eat; but they either could not, or would not understand me: for though they seemed very desirous of the hatchets and the bill-hooks, they did not give the least intimation that they would part with any previsions; no traffick therefore was carried on between us.

Each of these people, both men and women, had a horse, with a decent saddle, stirrups, and bridle. The men had wooden spurs, except one, who had a large pair of such as are worn in Spain, brass stirrups, and a Spanish cimeter, without a scabbard; but notwithstanding these distinctions, he did not appear to have any authority over the rest: the women had no spurs. The horses appeared to be well made, and nimble, and were about 14 hands high. The people had also many dogs with them, which, as well as the horses, appeared to be of a Spanish breed.

[page] 374

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

As I had two measuring rods with me, we went round and measured those that appeared to be tallest among them. One of these was six feet seven inches high, several more were six feet five, and six feet six inches; but the stature of the greater part of them was from five feet ten to six feet. Their complexion is a dark copper colour, like that of the Indians in North America; their hair is strait, and nearly as harsh as hog's bristles: it is tied back with a cotton string, but neither sex wears any head-dress. They are well made, robust, and boney; but their hands and feet are remarkably small. They are cloathed with the skins of the guanico, sewed together into pieces about six foot long, and five wide: these are wrapped round the body, and fastened with a girdle, with the hairy side inwards; some of them had also what the Spaniards have called a puncho, a square piece of cloth made of the downy hair of the guanico, through which a hole being cut for the head, the rest hangs round them about as low as the knee. The guanico is an animal that in size, make, and colour, resembles a deer, but it has a hump on its back, and no horns. These people wear also a kind of drawers, which they pull up very tight, and buskins, which reach from the mid-leg to the instep before, and behind are brought under the heel; the rest of the foot is without any covering. We observed that several of the men had a red circle painted round the left eye, and that others were painted on their arms, and on different parts of the face; the eye-lids of all the young women were painted black. They talked much, and some of them called out Ca-pi-ta-ne; but when they were spoken to in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Dutch, they made no reply. Of their own language we could distinguish only one word, which was chevoro: we supposed it to be a salutation, as they always

[page] 375

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

pronounced it when they shook hands with us, and when, by signs, they asked us to give them any thing. When they were spoken to in English, they repeated the words after us as plainly as we could do; and they soon got by heart the words "Englishmen come on shore." Every one had a missile weapon of a singular kind, tucked into the girdle. It consisted of two round stones, covered with leather, each weighing about a pound, which were fastened to the two ends of a string about eight feet long. This is used as a sling, one stone being kept in the hand, and the other whirled round the head till it is supposed to have acquired sufficient force, and then discharged at the object. They are so expert in the management of this double-headed shot, that they will hit a mark, not bigger than a shilling, with both the stones, at the distance of fifteen yards; it is not their custom, however, to strike either the guanico or the ostrich with them in the chace, but they discharge them so that the cord comes against the legs of the ostrich, or two of the legs of the guanico, and is twisted round them by the force and swing of the balls, so that the animal being unable to run, becomes an easy prey to the hunter.

While we stayed on shore, we saw them eat some of their flesh meat raw, particularly the paunch of an ostrich, without any other preparation or cleaning than just turning it inside out, and shaking it. We observed among them several beads, such as I gave them, and two pieces of red baize, which we supposed had been left there, or in the neighbouring country, by Commodore Byron.

After I had spent about four hours with these people, I made signs to them that I was going on board, and that I would take some of them with me if they were desirous to go. As soon as I had made myself understood, above an hundred

[page] 376

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

eagerly offered to visit the ship; but I did not chuse to indulge more than eight of the number. They jumped into the boats with the joy and alacrity of children going to a fair, and having no intention of mischief against us, had not the least suspicion that we intended any mischief against them. They sung several of their country songs while they were in the boat, and when they came on board did not express either the curiosity or wonder which the multiplicity of objects, to them equally strange and stupendous, that at once presented themselves, might be supposed to excite. I took them down into the cabbin, where they looked about them with an unaccountable indifference, till one of them happened to cast his eyes upon a looking-glass: this however excited no more astonishment than the prodigies which offer themselves to our imagination in a dream, when we converse with the dead, fly in the air, and walk upon the sea, without reflecting that the laws of nature are violated; but it afforded them infinite diversion: they advanced, retreated, and played a thousand tricks before it, laughing violently, and talking with great emphasis to each other. I gave them some beef, pork, biscuit, and other articles of the ship's provisions: they eat, indiscriminately, whatever was offered to them, but they would drink nothing but water. From the cabbin I carried them all over the ship, but they looked at nothing with much attention, except the animals which we had on board as live stock: they examined the hogs and sheep with some curiosity, and were exceedingly delighted with the Guinea hens and turkies; they did not seem to desire any thing that they saw except our apparel, and only one of them, an old man, asked for that: we gratified him with a pair of shoes and buckles, and to each of the others I gave a canvas bag, in which I put some needles ready threaded, a few slips of cloth, a knife, a pair of scissars, some twine, a

3

[page] 377

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

few beads, a comb, and a looking-glass, with some new sixpences and halfpence, through which a hole had been drilled, that was fitted with a riband to hang round the neck. We offered them some leaves of tobacco, rolled up into what are called segars, and they smoked a little, but did not seem fond of it. I showed them the great guns, but they did not appear to have any notion of their use. After I had carried them through the ship, I ordered the marines to be drawn up, and go through part of their exercise. When the first volley was fired, they were struck with astonishment and terror; the old man in particular, threw himself down upon the deck, pointed to the muskets, and then striking his breast with his hand, lay some time motionless, with his eyes shut: by this we supposed he intended to shew us that he was not unacquainted with fire-arms, and their fatal effect. The rest seeing our people merry, and finding themselves unhurt, soon resumed their cheerfulness and good humour, and heard the second and third volley fired without much emotion; but the old man continued prostrate upon the deck some time, and never recovered his spirits till the siring was over. About noon, the tide being out, I acquainted them by signs that the ship was proceeding farther, and that they must go on shore: this I soon perceived they were very unwilling to do; all however, except the old man and one more, were got into the boat without much difficulty; but these stopped at the gang-way, where the old man turned about, and went aft to the companion ladder, where he stood some time without speaking a word; lie then uttered what we supposed to be a prayer; for he many times lifted up his hands and his eyes to the heavens, and spoke in a manner and tone very different from what we had observed in their conversation: his oraison seemed to be rather sung than said, so that we found it impossible to distinguish one

VOL. I. C c c

[page] 378

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

word from another. When I again intimated that it was proper for him to go into the boat, he pointed to the fun, and then moving his hand round to the west, he paused, looked in my face, laughed, and pointed to the shore: by this it was easy to understand that he wished to stay on board till fun-set, and I took no little pains to convince him that we could not stay so long upon that part of the coast, before he could be prevailed upon to go into the boat; at length however he went over the ship's side with his companion, and when the boat put off they all began to sing, and continued their merriment till they got on shore. When they landed, great numbers of those on shore pressed eagerly to get into the boat; but the officer on board, having positive orders to bring none of them off, prevented them, though not without great difficulty, and apparently to their extream mortification and disappointment.

When the boat returned on board, I sent her off again with the master, to found the shoal that runs off from the point: he found it about three miles broad from north to south, and that to avoid it, it was necessary to keep four miles off the Cape, in twelve or thirteen fathom water.

[page] 379

CHAP. II.

The Passage through the Streight of Magellan, with some further account of the Patagonians, and a description of the Coast on each side, and its Inhabitants.

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

ABOUT one o'clock, on Wednesday the 17th of December, I made the signal and weighed, ordering the Swallow to go a-head, and the store-ship to bring up the rear. The wind was right against us, and blew fresh, so that we were obliged to turn into the Streight of Magellan with the flood-tide, between Cape Virgin Mary and the Sandy Point that resembles Dungeness. When we got a-breast of this Point, we stood close into the shore, where we saw two guanicoes, and many of the natives on horseback, who seemed to be in pursuit of them: when the horsemen came near, they ran up the country at a great rate, and were pursued by the hunters, with their slings in their hands ready for the cast; but neither of them was taken while they were within the reach of our sight.

When we got about two leagues to the west of Dungeness, and were standing off shore, we fell in with a shoal upon which we had but seven fathom water at half flood: this obliged us to make short tacks, and keep continually heaving the lead. At half an hour after eight in the evening, we anchored about three miles from the shore, in 20 fathom, with a muddy bottom: Cape Virgin Mary then bearing N. E. by E. ½ E.; Point Possession W. ½ S. at the distance of about five leagues.

C c c 2

[page] 380

1766. December.

Wednes. 17.

Thursday 18.

About half an hour after we had cast anchor, the natives made several large fires a-breast of the ship, and at break of day we saw about four hundred of them encamped in a fine green valley, between two hills, with their horses feeding beside them. About six o'clock in the morning, the tide being done, we got again under sail: it's course here is from east to west; it rises and falls thirty feet, and its strength is equal to about three knots an hour. About noon there being little wind, and the ebb running with great force, the Swallow, who was a-head, made the signal and came to an anchor; upon which I did the same, and so did the store-ship, that was a-stern.

As we saw great numbers of the natives on horseback a-breast of the ship, and as Captain Carteret informed me that this was the place where Commodore Byron had the conference with the tall men, I sent the lieutenants of the Swallow and the store-ship to the shore, but with orders not to land, as the ships were at too great a distance to protect them. When these gentlemen returned, they told me that the boat having lain upon her oars very near the beach, the natives came down in great numbers, whom they knew to be the same persons they had seen the day before, with many others, particularly women and children; that when they perceived our people had no design to land, they seemed to be greatly disappointed, and those who had been on board the ship waded off to the boat, making signs for it to advance, and pronouncing the words they had been taught, "Englishmen come on shore," very loud, many times; that when they found they could not get the people to land, they would fain have got into the boat, and that it was with great difficulty they were prevented. That they presented them

[page] 381

1766. December.

with some bread, tobacco, and a few toys, pointing at the same time to some guanicoes and ostriches, and making signs that they wanted them as provisions, but that they could not make themselves understood; that finding they could obtain no refreshment, they rowed along the shore in search of fresh water, but that seeing no appearance of a rivulet, they returned on board.

Friday 19.

At six o'clock the next morning, we weighed, the Swallow being still a-head, and at noon we anchored in Possession bay, having twelve fathom, with a clean sandy bottom. Point Possession at this time bore East, distant three leagues; the Asses Ears west, and the entrance of the Narrows S. W. ½ W.: the bottom of the bay, which was the nearest land to the ship, was distant about three miles. We saw a great number of Indians upon the Point, and at night, large fires on the Terra del Fuego shore.

Monday 22.

From this time, to the 22d, we had strong gales and heavy seas, so that we got on but slowly; and we now anchored in 18 fathom, with a muddy bottom. The Asses Ears bore N. W. by W. ½ W. Point Possession N. E. by E. and the point of the Narrows, on the south side, S. S. W. distant between three and four leagues. In this situation, our longitude, by observation, was 70° 20′W. latitude 52° 30′S. The tide here sets S.E. by S. and N.E. by N. at the rate of about three knots an hour; the water rises four and twenty feet, and at this time it was high water at four in the morning.

Tuesday 23.

In the morning of the 23d, we made sail, turning to windward, but the tide was so strong, that the Swallow was set one way, the Dolphin another, and the store-ship a third: there was a fresh breeze, but not one of the vessels would answer her helm. We had various soundings, and saw the rippling in the middle ground: in these circumstances,

3

[page] 382

1766. December.

Tuesday 23.

Wednes. 24.

sometimes backing, sometimes filling, we entered the first Narrows. About six o'clock in the evening, the tide being done, we anchored on the south shore, in 40 fathom, with a sandy bottom; the Swallow anchored on the north shore, and the store-ship not a cable's length from a sand bank, about two miles to the eastward. The streight here is only three miles wide, and at midnight, the tide being slack, we weighed and towed the ship through. A breeze sprung up soon afterwards, which continued till seven in the morning, and then died away. We steered from the first Narrows to the second S. W. and had 19 fathom, with a muddy bottom. At eight we anchored two leagues from the shore, in 24 fathom, Cape Gregory bearing W. ½ N. and Sweepstakes Foreland S. W. ½ W. The tide here ran seven knots an hour, and such bores sometimes came down, with immense quantities of weeds, that we expected every moment to be adrift.

Thursday 25.

The next day, being Christmas day, we sailed through the second Narrows. In turning through this part of the Streight we had 12 fathom within half a mile of the shore on each side, and in the middle 17 fathom, 22 fathom, and no ground. At five o'clock in the evening, the ship suddenly shoaled from 17 fathom to 5, St. Bartholomew's island then bearing S. ½ W. distant between three and four miles, and Elizabeth island S. S. W. ½ W. distant five or six miles. About half an hour after eight o'clock, the weather being rainy and tempestuous, we anchored under Elizabeth island in 24 fathom, with hard gravelly ground. Upon this island we found great quantities of celery, which, by the direction of the surgeon, was given to the people, with boiled wheat and portable soup, for breakfast every morning. Some of the officers who went ashore with their guns, saw two small dogs, and several places where fires had been recently

[page] 383

1766. December.

made, with many fresh shells of muscles and limpets lying about them: they saw also several wigwams or huts, consisting of young trees, which, being sharpened at one end, and thrust into the ground in a circular form, the other ends were brought to meet, and fastened together at the top; but they saw none of the natives.

From this place we saw many high mountains, bearing from S. to W. S. W.; several parts of the summits were covered with snow, though it was the midst of summer in this part of the world: they were clothed with wood about three parts of their height, and above with herbage, except where the snow was not yet melted. This was the first place where we had seen wood in all South America.

Friday 26.

At two o'clock in the morning of the 26th, we weighed, and having a fair wind, were a-breast of the north end of Elizabeth's island at three: at half an hour after five, being about mid-way between Elizabeth's island and St. George's island, we suddenly shoaled our water from 17 fathom to six: we struck the ground once, but the next cast had no bottom with 20 fathom. When we were upon this shoal, Cape Porpoise bore W.S.W. ½ W. the south-end of Elizabeth's island W. N. W. ½ W. distant three leagues, and the south-end of Saint George's island N. E. distant four leagues. The store-ship, which was about half a league to the southward of us, had once no more than four fathom, and for a considerable time not seven; the Swallow, which was three or four miles to the southward, had deep water, for she kept near to St. George's island. In my opinion it is safest to run down from the north-end of Elizabeth's island, about two or three miles from the shore, and so on all the way to Port Famine. At noon, a low point bore E. ½ N. Fresh-water Bay S. W. ½ W. At this time we were about three miles distant

2

[page] 384

1766. December.

Friday 26.

from the north shore, and had no ground with 80 fathom. Our longitude, by observation, which was made over the shoal, was 71° 20′W. our latitude 53° 12′S.

About four o'clock we anchored in Port Famine Bay, in 13 fathom, and there being little wind, sent all the boats, and towed in the Swallow and Prince Frederick.

Saturday 27.

The next morning, the weather being squally, we warped the ship farther into the harbour, and moored her with a cable each way in nine fathom. I then sent a party of men to pitch two large tents in the bottom of the bay, for the sick, the wooders, and the sail-makers, who were soon after sent on shore with the surgeon, the gunner, and some midshipmen. Cape St. Anne now bore N. E. by E. distant three quarters of a mile, and Sedger River S.½ W.

Sunday 28.

On the 28th we unbent all the sails, and sent them on shore to be repaired, erected tents upon the banks of Sedger River, and sent all the empty casks on shore, with the coopers to trim them, and a mate and ten men to wash and fill them. We also hauled the seine, and caught fish in great plenty: some of them resembled a mullet, but the flesh was very soft; and among them were a few smelts, some of which were twenty inches long, and weighed four and twenty ounces.

During our whole stay in this place, we caught fish enough to furnish one meal a day both for the sick and the well: we found also great plenty of celery and pea-tops, which were boiled with the pease and portable soup: besides these, we gathered great quantities of fruit that resembled the cranberry, and the leaves of a shrub somewhat like our thorn, which were remarkably four. When we arrived, all our people began to look pale and meagre; many had the scurvy to a great degree, and upon others there were manifest signs of its approach; yet in a fortnight there was not

[page] 385

1766. December.

a scorbutic person in either of the ships. Their recovery was effected by their being on shore, eating plenty of vegetables, being obliged to wash their apparel, and keep their persons clean by daily bathing in the sea.

Monday 29.

The next day we set up the forge on shore; and from this time, the armourers, carpenters, and the rest of the people were employed in refitting the ship, and making her ready for the sea.

In the mean time, a considerable quantity of wood was cut, and put on board the store-ship, to be sent to Falkland's island; and as I well knew there was no wood growing there, I caused some thousands of young trees to be carefully taken up with their roots, and a proper quantity of earth; and packing them in the best manner I could, I put them also on board the store-ship, with orders to deliver them to the commanding officer at Port Egmont, and to sail for that place with the first fair wind, putting on board two of my seamen, who being in an ill state of health when they first came on board, were now altogether unfit to proceed in the voyage.

1767. January.

Wednes. 14.

On Wednesday the 14th of January, we got all our people and tents on board; having taken in seventy-five tons of water from the shore, and twelve months provisions of all kinds, at whole allowance, for ourselves, and ten months for the Swallow, from on board the store-ship, I sent the master in the cutter, which was victualed for a week, to look out for anchoring places on the north shore of the Streight.

Saturday 17.

After several attempts to fail, the weather obliged us to continue in our old station till Saturday the 17th, when the Prince Frederick Victualer sailed for Falkland's island, and

VOL. I. D d d

[page] 386

1767. January.

the master returned from his expedition. The master reported that he had found four places, in which there was good anchorage, between the place where we lay and Cape Froward: that he had been on shore at several places, where he had found plenty of wood and water close to the beach, with abundance of cranberries and wild celery. He reported also, that he had seen a great number of currant bushes full of fruit, though none of it was ripe, and a great variety of beautiful shrubs in full blossom, bearing flowers of different colours, particularly red, purple, yellow, and white, besides great plenty of the winter's bark, a grateful spice which is well known to the botanists of Europe. He shot several wild ducks, geese, gulls, a hawk, and two or three of the birds which the sailors call a Race-Horse.

Sunday 18.

At five o'clock in the morning of Sunday the 18th, we made sail, and at noon, being about two miles from the shore, Cape Froward bore N. by E. a bluff point N. N. W. and Cape Holland W. ½ S. Our latitude at this place, by observation, was 54° 3′S. and we found the Streight to be about six miles wide. Soon after I sent a boat into Snug bay, to lie at the anchoring place, but the wind coming from the land, I stood off again all night; and at a mile from the shore, we had no ground with 140 fathom.

Monday 19.

In the morning of Monday the 19th, the Swallow having made the signal for anchoring under Cape Holland, we ran in, and anchored in 10 fathom, with a clear sandy bottom. Upon sending the boats out to found, we discovered that we were very near a reef of rocks; we therefore tripped the anchor, and dropped farther out, where we had 12 fathom, and were about half a mile from the shore, just opposite to a large stream of water which falls with great rapidity from

2

[page] 387

1767. January.

the mountains, for the land here is of a stupendous height. Cape Holland bore W. S. W. ½ W. distant two miles, and Cape Froward E. Our latitude, by observation, was 53° 58′S.

Tuesday 20.

The next morning we got off some water, and great plenty of wild celery, but could get no fish, except a few muscles. I sent off the boats to sound, and found that there was good anchorage at about half a mile from the shore, quite from the Cape to four miles below it; and close by the Cape a good harbour, where a ship might refresh with more safety than at Port Famine, and avail herself of a large river of fresh water, with plenty of wood, celery, and berries; though the place affords no fish except muscles.

Thurs. 22.

Having completed our wood and water, we sailed from this place on the 22d, about three o'clock in the afternoon. At nine in the evening, the ship being about two miles distant from the shore, Cape Gallant bore W. ½ N. distant two leagues, Cape Holland E. by N. distant six leagues; Cape Gallant and Cape Holland being nearly in one: a white patch in Monmouth's island bore S.S.W. ¾ W. Rupert's island W.S. W. At this place the Streight is not more than five miles over; and we found a tide which produced a very unusual effect, for it became impossible to keep the ship's head upon any point.

Friday 23.

At six the next morning, the Swallow made the signal for having found anchorage; and at eight we anchored in a bay under Cape Gallant, in 10 fathom, with a muddy bottom. The east point of Cape Gallant bore S. W. by W. ¼ W. the extream point of the eastermost land E. by S. a point making the mouth of a river N. by W. and the white patch on Charles's island S. W. The boats being sent out to found, found good anchorage every where, except within two cables length S. W. of the ship, where it was coral, and

D d d 2

[page] 388

1767. January.

deepened to 16 fathom. In the afternoon I sent out the master to examine the bay and a large lagoon; and he reported that the lagoon was the most commodious harbour we had yet seen in the Streight, having five fathom at the entrance, and from four to five in the middle; that it was capable of receiving a great number of vessels, had three large fresh water rivers, and plenty of wood and celery. We had here the misfortune to have a seine spoiled, by being entangled with the wood that lies sunk at the mouth of these rivers; but though we caught but little fish, we had an incredible number of wild ducks, which we found a very good succedaneum.

The mountains are here very lofty, and the master of the Swallow climbed one of the highest, hoping that from the summit he should obtain a fight of the South Sea; but he found his view intercepted by mountains still higher on the southern shore: before he descended, however, he erected a pyramid, within which he deposited a bottle containing a shilling, and a paper on which was written the ship's name and the date of the year; a memorial which possibly may remain there as long as the world endures.

Saturday 24.

In the morning of the 24th we took two boats and examined Cordes bay, which we found very much inferior to that in which the ship lay; it had indeed a larger lagoon, but the entrance of it was very narrow, and barred by a shoal, on which there was not sufficient depth of water for a ship of burden to float: the entrance of the bay also was rocky, and within it the ground was foul.

In this place we saw an animal that resembled an ass, but it had a cloven hoof, as we discovered afterwards by tracking it, and was as swift as a deer. This was the first animal we had seen in the Streight, except at the entrance, where we

3

[page] 389

1767. January.

found the guanicoes that we would fain have trafficked for with the Indians. We shot at this creature, but we could not hit it; probably it is altogether unknown to the naturalists of Europe.

The country about this place has the most dreary and forlorn appearance that can be imagined; the mountains on each side the Streight are of an immense height: about one fourth of the ascent is covered with trees of a considerable size; in the space from thence to the middle of the mountain there is nothing but withered shrubs; above these are patches of snow, and fragments of broken rock; and the summit is altogether rude and naked, towering above the clouds in vast crags that are piled upon each other, and look like the ruins of Nature devoted to everlasting sterility and desolation.

We went over in two boats to the Royal Islands, and sounded, but found no bottom: a very rapid tide set through wherever there was an opening; and they cannot be approached by shipping without the most imminent danger. Whoever navigates this part of the Streight, should keep the north shore close on board all the way, and not venture more than a mile from it till the Royal Islands are passed. The current sets easterly through the whole four and twenty hours, and the indraught should by all means be avoided. The latitude of Cape Gallant road is 53° 50′S.

Tuesday 27.

Wednes. 28.

We continued in this station, taking in wood and water, and gathering muscles and herbs, till the morning of the 27th, when a boat that had been sent to try the current, returned with an account that it set nearly at the rate of two miles an hour, but that the wind being northerly, we might probably get round to Elizabeth bay or York road before night; we therefore weighed with all expedition. At noon on the 28th, the west point of Cape Gallant bore W. N. W.

[page] 390

1767. January.

distant half a mile, and the white patch on Charles's island S. E. by S. We had fresh gales and heavy flaws off the land; and at two o'clock the west point of Cape Gallant bore E. distant three leagues, and York Point W. N. W. distant five leagues. At five, we opened York road, the Point bearing N. W. at the distance of half a mile: at this time the ship was taken a-back, and a strong current with a heavy squall drove us so far to leeward, that it was with great difficulty we got into Elizabeth bay, and anchored in 12 fathom near a river. The Swallow being at anchor off the point of the bay, and very near the rocks, I sent all the boats with anchors and hausers to her assistance, and at last she was happily warped to windward into good anchorage. York Point now bore W. by N. a shoal with weeds upon it W. N. W. at the distance of a cable's length, Point Passage S. E. ½ E. distant half a mile, a rock near Rupert's isle S. ½ E. and a rivulet on the bay N. E. by E. distant about three cable's length. Soon after sun-set we saw a great smoke on the southern shore, and another on Prince Rupert's island.

Thursday 29.

Early in the morning I sent the boats on shore for water, and soon after our people landed, three canoes put off from the south shore, and landed sixteen of the natives on the east point of the bay. When they came within about a hundred yards of our people they stopt, called out, and made signs of friendship; our people did the same, shewing them some beads and other toys. At this they seemed pleased, and began to shout; our people imitated the noise they made, and shouted in return: the Indians then advanced, still shouting and laughing very loud. When the parties met they shook hands, and our men presented the Indians with several of the toys which they had shewn them at a distance. They were covered with seal skins, which stunk abominably, and some of them were eating the rotten flesh and blubber raw,

[page] 391

1767. January.

Thursday 29.

with a keen appetite and great seeming satisfaction. Their complexion was the same as that of the people we had seen before, but they were low of stature, the tallest of them not being more than five foot six: they appeared to be perishing with cold, and immediately kindled several fires. How they subsist in winter, it is not perhaps easy to guess, for the weather was at this time so severe, that we had frequent falls of snow. They were armed with bows, arrows, and javelins: the arrows and javelins were pointed with flint, which was wrought into the shape of a serpent's tongue; and they discharged both with great force and dexterity, scarce ever failing to hit a mark at a considerable distance. To kindle a fire they strike a pebble against a piece of mundic, holding under it, to catch the sparks, some moss or down, mixed with a whitish earth, which takes fire like tinder: they then take some dry grass, of which there is every where plenty, and putting the lighted moss into it, wave it to and fro, and in about a minute it blazes.

When the boat returned she brought three of them on board the ship, but they seemed to regard nothing with any degree of curiosity except our cloaths and a looking-glass; the looking-glass afforded them as much diversion as it had done the Patagonians, and it seemed to surprize them more: when they first peeped into it they started back, first looking at us, and then at each other; they then took another peep, as it were by stealth, starting back as before, and then eagerly looking behind it: when by degrees they became familiar with it, they smiled, and seeing the image smile in return, they were exceedingly delighted, and burst into sits of the most violent laughter. They left this however, and every thing else, with perfect indifference, the little they possessed being to all appearance equal to their desires. They

[page] 392

1767. February.

eat whatever was given them, but would drink nothing but water.

When they left the ship I went on shore with them, and by this time several of their wives and children were come to the watering-place. I distributed some trinkets among them, with which they seemed pleased for a moment, and they gave us some of their arms in return; they gave us also several pieces of mundic, such as is found in the tin mines of Cornwall: they made us understand that they found it in the mountains, where there are probably mines of tin, and perhaps of more valuable metal. As this seems to be the most dreary and inhospitable country in the world, not excepting the worst parts of Sweden and Norway, the people seem to be the lowest and most deplorable of all human beings. Their perfect indifference to every thing they saw, which marked the disparity between our state and their own, though it may preserve them from the regret and anguish of unsatisfied desires, seems, notwithstanding, to imply a defect in their nature; for those who are satisfied with the gratifications of a brute, can have little pretension to the prerogatives of men. When they left us and embarked in their canoes, they hoisted a seal skin for a sail, and steered for the southern shore, where we saw many of their hovels; and we remarked that not one of them looked behind, either at us or at the ship, so little impression had the wonders they had seen made upon their minds, and so much did they appear to be absorbed in the present, without any habitual exercise of their power to reflect upon the past.

Tuesday 3.

In this station we continued till Tuesday the 3d of February. At about half an hour past twelve we weighed, and in a sudden squall were taken a-back, so as that both ships were in the most imminent danger of being driven ashore

[page] 393

1767. February.

Tuesday 3.

on a reef of rocks; the wind however suddenly shifted, and we happily got off without damage. At five o'clock in the afternoon, the tide being done, and the wind coming about to the west, we bore away for York road, and at length anchored in it: the Swallow at the same time being very near Island bay, under Cape Quod, endeavoured to get in there, but was by the tide obliged to return to York road. In this situation Cape Quod bore W. ½ S. distant 19 miles, York Point E. S. E. distant one mile, Bachelor's River N. N. W. three quarters of a mile, the entrance of Jerom's Sound N. W. by W. and a small island on the south shore W. by S. We found the tide here very rapid and uncertain; in the stream it generally set to the eastward, but it sometimes, though rarely, set westward six hours together. This evening we saw five Indian canoes come out of Bachelor's River, and go up Jerom's Sound.

Wednes. 4.

In the morning, the boats which I had sent out to found both the shores of the Streight and all parts of the bay, returned with an account that there was good anchorage within Jerom's Sound, and all the way thither from the ship's station at the distance of about half a mile from the shore; also between Elizabeth and York Point, near York Point, at the distance of a cable and a half's length from the weeds, in 16 fathom with a muddy bottom. There were also several places under the islands on the south shore where a ship might anchor; but the force and uncertainty of the tides, and the heavy gusts of wind that came off the high lands, by which these situations were surrounded, rendered them unsafe. Soon after the boats returned, I put fresh hands into them and went myself up Bachelor's River: we found a bar at the entrance, which at certain times of the tide must be dangerous. We hauled the seine, and should have caught plenty of fish if it had not been for the weeds and

VOL. I. E e e

[page] 394

1767. February.

stumps of trees at the bottom of the river. We then went ashore, where we saw many wigwams of the natives, and several of their dogs, who, as soon as we came in sight, ran away. We also saw some ostriches, but they were beyond the reach of our pieces: we gathered muscles, limpets, sea-eggs, celery, and nettles in great abundance. About three miles up this river, on the west side, between Mount Misery and another mountain of a stupendous height, there is a cataract which has a very striking appearance: it is precipitated from an elevation of above four hundred yards; half the way it rolls over a very steep declivity, and the other half is a perpendicular fall. The found of this cataract is not less awful than the sight.

Saturday 14.

In this place, contrary winds detained us till 10 o'clock in the morning of Saturday the 14th, when we weighed, and in half an hour the current set the ship towards Bachelor's River: we then put her in stays, and while she was coming about, which she was long in doing, we drove over a shoal where we had little more than 16 feet water with rocky ground; so that our danger was very great, for the ship drew 16 feet 9 inches aft, and 15 feet one inch forward: as soon as the ship gathered way, we happily deepened into three fathom; within two cables' length we had five, and in a very short time we got into deep water. We continued plying to windward till four o'clock in the afternoon, and then finding that we had lost ground, we returned to our station, and again anchored in York road.

Tuesday 17.

Here we remained till five o'clock in the morning of the 17th, when we weighed, and towed out of the road. At nine, though we had a sine breeze at west, the ship was carried with great violence by a current towards the south shore: the boats were all towing a-head, and the fails asleep, yet we

2

[page] 395

1767. February.

Tuesday 17.

drove so close to the rock, that the oars of the boats were entangled in the weeds. In this manner we were hurried along near three quarters of an hour, expecting every moment to be dashed to pieces against the cliff, from which we were seldom farther than a ship's length, and very often not half so much. We founded on both sides, and found that next the shore we had from 14 to 20 fathom, and on the other side of the ship no bottom: as all our efforts were ineffectual, we resigned ourselves to our fate, and waited the event in a state of suspense very little different from despair. At length, however, we opened Saint David's Sound, and a current that rushed out of it set us into the mid-channel. During all this time the Swallow was on the north shore, and consequently could know nothing of our danger till it was past. We now sent the boats out to look for an anchoring place; and at noon Cape Quod bore N. N. E. and Saint David's head S. E.

About one o'clock the boats returned, having found an anchoring place in a small bay, to which we gave the name of Butler's bay, it having been discovered by Mr. Butler one of the mates. It lies to the west of Rider's bay on the south shore of the Streight, which is here about two miles wide. We ran in with the tide which set fast to the westward, and anchored in 16 fathom water. The extreams of the bay from W. by N. to N. ½ W. are about a quarter of a mile asunder; a small rivulet, at the distance of somewhat less than two cables' length, bore S. ½ W. and Cape Quod N. at the distance of four miles. At this time the Swallow was at anchor in Island bay on the north shore, at about six miles distance.

I now sent all the boats out to sound round the ship and in the neighbouring bays; and they returned with an ac-

E e e 2

[page] 396

1767. February.

count that they could find no place fit to receive the ship, neither could any such place be found between Cape Quod and Cape Notch.

Friday 20.

Saturday 21.

In this place we remained till Friday the 20th, when about noon the clouds gathered very thick to the westward, and before one it blew a storm, with such rain and hail as we had scarcely ever seen. We immediately struck the yards and top-masts, and having run out two hausers to a rock, we hove the ship up to it: we then let go the small bower; and veered away, and brought both cables a-head; at the same time we carried out two more hausers, and made them fast to two other rocks, making use of every expedient in our power to keep the ship steady. The gale continued to increase till six o'clock in the evening, and to our great astonishment the sea broke quite over the fore-castle in upon the quarter-deck, which, considering the narrowness of the Streight, and the smallness of the bay in which we were stationed, might well have been thought impossible. Our danger here was very great, for if the cables had parted, as we could not run out with a sail, and as we had not room to bring the ship up with any other anchor, we must have been dashed to pieces in a few minutes, and in such a situation it is highly probable that every soul would immediately have perished; however, by eight o'clock the gale was become somewhat more moderate, and gradually decreasing during the night, we had tolerable weather the next morning. Upon heaving the anchor, we had the satisfaction to find that our cable was found, though our hausers were much rubbed by the rocks, notwithstanding they were parcelled with old hammacocs, and other things. The first thing I did after performing the necessary operations about the ship, was to send a boat to the Swallow to enquire how she had fared during the gale: the boat returned with an account that she had felt but

[page] 397

1767. February.

Saturday 21.

little of the gale, but that she had been very near being lost, in pushing through the Islands two days before, by the rapidity of the tide: that notwithstanding an alteration which had been made in her rudder, she steered and worked so ill, that every time they got under way they were apprehensive that she could never safely be brought to an anchor again; I was therefore requested, in the name of the captain, to consider that she could be of very little service to the expedition, and to direct what I thought would be best for the service. I answered, that as the Lords of the Admiralty had appointed her to accompany the Dolphin, she must continue to do it as long as it was possible; that as her condition rendered her a bad sailer, I would wait her time, and attend her motions, and that if any disaster should happen to either of us, the other should be ready to afford such assistance as might be in her power.

We continued here eight days, during which time we completed our wood and water, dried our fails, and sent great part of the ship's company on shore, to wash their cloathes and stretch their legs, which was the more necessary, as the cold, snowy, and tempestuous weather had confined them too much below. We caught muscles and limpets, and gathered celery and nettles in great abundance. The muscles were the largest we had ever seen, many of them being from five to six inches long: we caught also great plenty of a fine, firm, red fish, not unlike a gurnet, most of which, were from four to five pounds weight. At the same time, we made it part of the employment of every day to try the current, which we found constantly setting to the eastward.

The master having been sent out to look for anchoring places, returned with an account that he could find no shelter, except near the shore, where it should not be fought but in

[page] 398

1767. February.

Saturday 21.

cases of the most pressing necessity. He landed upon a large island on the north side of Snow Sound, and being almost perished with cold, the first thing he did was to make a large fire, with some small trees which he found upon the spot. He then climbed one of the rocky mountains, with Mr. Pickersgill, a midshipman, and one of the seamen, to take a view of the Streight, and the dismal regions that surround it. He found the entrance of the Sound to be full as broad as several parts of the Streight, and to grow but very little narrower, for several miles in land on the Terra del Fuego side. The country on the south of it was still more dreary and horrid than any he had yet seen: it consisted of craggy mountains, much higher than the clouds, that were altogether naked from the base to the summit, there not being a single shrub, nor even a blade of grass to be seen upon them; nor were the vallies between them less desolate, being intirely covered with deep beds of snow, except here and there where it had been washed away, or converted into ice, by the torrents which were precipitated from the fissures and crags of the mountain above, where the snow had been dissolved; and even these vallies, in the patches that were tree from snow, were as destitute of verdure as the rocks between which they lay.

March.

Sunday 1.

On Sunday the first of March, at half an hour after four o'clock in the morning, we saw the Swallow under sail, on the north shore of Cape Quod. At seven we weighed, and stood out of Butler's bay, but it falling calm soon afterwards, the boats were obliged to take the vessel in tow, having with much difficulty kept clear of the rocks: the passage being very narrow, we sent the boats, about noon, to seek for anchorage on the north shore. At this time, Cape Notch bore W. by N. ½ N. distant between three and four leagues, and Cape Quod E. ½ N. distant three leagues.

[page] 399

1767. March.

About three o'clock in the afternoon, there being little wind, we anchored, with the Swallow, under the north shore, in a small bay, where there is a high, steep, rocky mountain, the top of which resembles the head of a lion, for which reason we called the bay Lion's Cove. We had here 40 fathom, with deep water close to the shore, and at half a cable's length without the ship, no ground. We sent the boats to the westward in search of anchoring places, and at midnight they returned with an account that there was an indifferent bay at the distance of about four miles, and that Goodluck bay was three leagues to the westward.

Monday 2.

At half an hour after 12 the next day, the wind being northerly, we made sail from Lion's Cove, and at five anchored in Good Luck bay, at the distance of about half a cable's length from the rocks, in 28 fathom water. A rocky island at the west extremity of the bay bore N.W. by W. distant about a cable's length and a half, and a low point, which makes the eastern extremity of the bay, bore E. S. E. distant about a mile. Between this point and the ship, there were many shoals, and in the bottom of the bay two rocks, the largest of which bore N. E. by N. the smallest N. by E. From these rocks, shoals run out to the S. E. which may be known by the weeds that are upon them; the ship was within a cable's length of them: when she swung with her stern in shore, we had 16 fathom, with coral rock; when she swung off, we had 50 fathom, with sandy ground. Cape Notch bore from us W. by S. ½ W. distant about one league; and in the intermediate space there was a large lagoon which we could not found, the wind blowing too hard all the while we lay here. After we had moored the ship, we sent two boats to assist the Swallow, and one to look out for anchorage beyond Cape Notch. The boats that were sent to assist the Swallow, towed her into a small bay, where,

[page] 400

1767. March.

as the wind was southerly, and blew fresh, she was in great danger, for the Cove was not only small, but full of rocks, and open to the south-easterly winds.

Tuesday 3.

Wednes. 4.

Saturday 7.

Sunday 8.

All the day following, and all the night, we had hard gales, with a great sea, and much hail and rain. The next morning we had gusts so violent, that it was impossible to stand the deck; they brought whole sheets of water all the way from Cape Notch, which was a league distant, quite over the deck. They did not last more than a minute, but were so frequent, that the cables were kept in a constant strain, and there was the greatest reason to fear that they would give way. It was a general opinion that the Swallow could not possibly ride it out, and some of the men were so strongly prepossessed with the notion of her being lost, that they fancied they saw some of her people coming over the rocks towards our ship. The weather continued so bad, till Saturday the seventh, that we could send no boat to enquire after her; but the gale being then more moderate, a boat was dispatched about four o'clock in the morning, which, about the same hour in the afternoon, returned with an account that the ship was safe, but that the fatigue of the people had been incredible, the whole crew having been upon the deck near three days and three nights. At midnight the gusts returned, though not with equal violence, with hail, sleet and snow. The weather being now extremely cold, and the people never dry, I got up, the next morning, eleven bales of thick woollen stuff, called Fearnought, which is provided by the government, and set all the taylors to work to make them into jackets, of which every man in the ship had one.

I ordered these jackets to be made very large, allowing, one with another, two yards and thirty-four inches of the cloth

[page] 401

1767. March.

to each jacket. I sent also seven bales of the same cloth to the Swallow, which made every man on board a jacket of the same kind; and I cut up three bales of finer cloth, and made jackets for the officers of both ships, which I had the pleasure to find were very acceptable.

In this situation we were obliged to continue a week, during which time, I put both my own ship, and the Swallow, upon two-thirds allowance, except brandy; but continued the breakfast as long as greens and water were plenty.

Sunday 15.

On Sunday the 15th, about noon, we saw the Swallow under sail, and it being calm, we sent our launch to assist her. In the evening the launch returned, having towed her into a very good harbour on the south shore, opposite to where we lay. The account that we received of this harbour, determined us to get into it as soon as possible; the next morning therefore, at eight o'clock, we sailed from Good Luck bay, and thought ourselves happy to get safe out of it. When we got a-breast of the harbour where the Swallow lay, we fired several guns, as signals for her boats to assist us in getting in; and in a short time the master came on board us, and piloted us to a very commodious station, where we anchored in 28 fathom, with a muddy bottom. This harbour, which is sheltered from all winds, and excellent in every respect, we called SWALLOW HARBOUR. There are two channels into it, which are both narrow, but not dangerous, as the rocks are easily discovered by the weeds that grow upon them.

Monday 16.

At nine o'clock the next morning, the wind coming easterly, we weighed, and failed from Swallow harbour. At noon we took the Swallow in tow, but at five there being little wind, we cast off the tow. At eight in the evening, the boats which had been sent out to look for anchorage,

VOL. I. F f f

[page] 402

1767. March.

returned with an account that they could find none: at nine we had fresh gales, and at midnight Cape Upright bore S. S. W ½ W.

Tuesday 17.

At seven the next morning, we took the Swallow again in tow, but was again obliged to cast her off and tack, as the weather became very thick, with a great swell, and we saw land close under our lee. As no place for anchorage could be found, Captain Carteret advised me to bear away for Upright bay, to which I consented; and as he was acquainted with the place, he went a-head: the boats were ordered to go between him and the shore, and we followed. At eleven o'clock, there being little wind, we opened a large lagoon, and a current setting strongly into it, the Swallow was driven among the breakers close upon the lee shore: to aggravate the misfortune, the weather was very hazey, there was no anchorage, and the surf ran very high. In this dreadful situation she made signals of distress, and we immediately sent our launch, and other boats, to her assistance: the boats took her in tow, but their utmost efforts to save her would have been ineffectual, if a breeze had not suddenly come down from a mountain, and wasted her off.

As a great swell came on about noon, we hauled over to the north shore. We soon found ourselves surrounded with islands, but the fog was so thick, that we knew not where we were, nor which way to steer. Among these islands the boats were sent to cast the lead, but no anchorage was to be found; we then conjectured that we were in the bay of islands, and that we had no chance to escape shipwreck, but by hauling directly out: this, however, was no easy task, for I was obliged to tack, almost continually, to weather some island or rock. At four o'clock in the afternoon, it happily cleared up for a minute, just to shew us Cape Up-

[page] 403

1767. March.

right, for which we directly steered, and at half an hour after five anchored, with the Swallow, in the bay. When we dropped the anchor, we were in 24 fathom, and after we had veered away a whole cable, in 46, with a muddy bottom. In this situation, a high bluff on the north shore bore N. W. ½ N. distant five leagues, and a small island within us S. by E. ½ E. Soon after we had anchored, the Swallow drove to leeward, notwithstanding she had two anchors a-head, but was at last brought up, in 70 fathom, about a cable's length a-stern of us. At four o'clock in the morning I sent the boats, with a considerable number of men, and some hausers and anchors, on board her, to weigh her anchors, and warp her up to windward. When her best bower anchor was weighed, it was found entangled with the small one; I therefore found it necessary to send the stream cable on board, and the ship was hung up by it. To clear her anchors, and warp her into a proper birth, cost us the whole day, and was not at last effected without the utmost difficulty and labour.

Wednes. 18.

On the 18th we had fresh breezes, and sent the boats to sound cross the Streight. Within half a mile of the ship, they had 40, 45, 50, 70, 100 fathom, and then had no ground, till within a cable's length of the lee shore, where they had 90 fathom. We now moored the ship in 78 fathom, with the stream anchor.

Thursday 19

The next morning, while our people were employed in getting wood and water, and gathering celery and muscles, two canoes, full of Indians, came along side of the ship. They had much the same appearance as the poor wretches whom we had seen before in Elizabeth's bay. They had on board some seal's flesh, blubber, and penguins, all which they eat raw. Some of our people, who were fishing with a

F f f 2

[page] 404

1767. March.

Thursday 19.

hook and line, gave one of them a fish, somewhat bigger than a herring, alive, just as it came out of the water. The Indian took it hastily, as a dog would take a bone, and instantly killed it, by giving it a bite near the gills: he then proceeded to eat it, beginning with the head, and going on to the tail, without rejecting either the bones, fins, scales, or entrails. They eat every thing that was given them, indifferently, whether salt or fresh, dressed or raw, but would drink nothing but water. They shivered with cold, yet had nothing to cover them but a seal skin; thrown loosely over their shoulders, which did not reach to their middle; and we observed, that when they were rowing, they threw even this by, and fat stark naked. They had with them some javelins, rudely pointed with bone, which they used to strike seals, fish, and penguins, and we observed that one of them had a piece of iron, about the size of a common chissel, which was fastened to a piece of wood, and seemed to be intended rather for a tool than a weapon. They had all sore eyes, which we imputed to their sitting over the smoke of their fires, and they smelt more offensively than a fox, which perhaps was in part owing to their diet, and in part to their nastiness. Their canoes were about fifteen foot long, three broad, and nearly three deep: they were made of the bark of trees, sewn together, either with the sinews of some beast, or thongs cut out of a hide. Some kind of rush was laid into the seams, and the outside was smeared with a resin, or gum, which prevented the water from soaking into the bark. Fifteen slender branches, bent into an arch, were sewed transversely to the bottom and sides, and some strait pieces were placed cross the top, from gunwale to gunwale, and securely lashed at each end: upon the whole, however, it was poorly made, nor had these people any thing among them in which there was the least appearance of ingenuity.

[page] 405

1767. March.

Thursday 19.

I gave them a hatchet or two, with some beads, and a few other toys, with which they went away to the southward, and we saw no more of them.