[page i]

A

VOYAGE

ROUND THE WORLD,

IN THE YEARS 1785, 1786, 1787, AND 1788,

By J. F. C. DELA PÉROUSE:

PUBLISHED CONTORMABLY TO THE DEGREE OF THE

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY,

OF THE 22D OF APRIL, 1791,

AND EDITED BY

M. L. A. MILET-MUREAU,

BRIGADIER GENERAL IN THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS,

DIRECTOR OF FORTIFICATIONS, EX-CONSTITUENT,

AND MEMBER OF SEVERAL LITERARY SOCIETIES AT PARIS.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, ST. PAUL'S CHURCH YARD,

1798.

[page ii]

[page iii]

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Description of Easter Island — Occurrences there — Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants | page 1. |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Journey of M. de Langle into the Interior of Easter Island—New Observations upon the Manners and the Arts of the Natives, upon the Quality and Cultivation of the Soil, &c. | page 21. |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

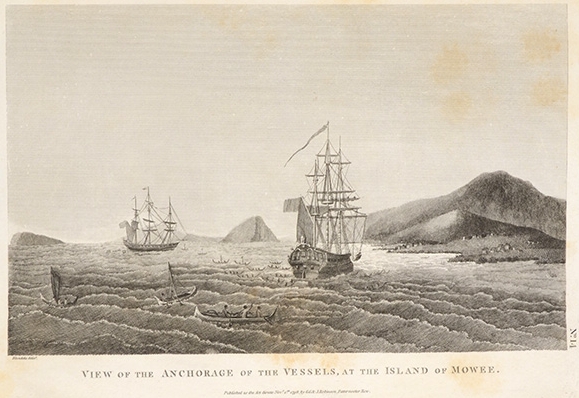

| Departure from Easter Island—Astronomical Observations—Arrival at the Sandwich Islands—Anchorage in the Bay of Keriporepo, in the Island of Mowée—Departure | page 29. |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

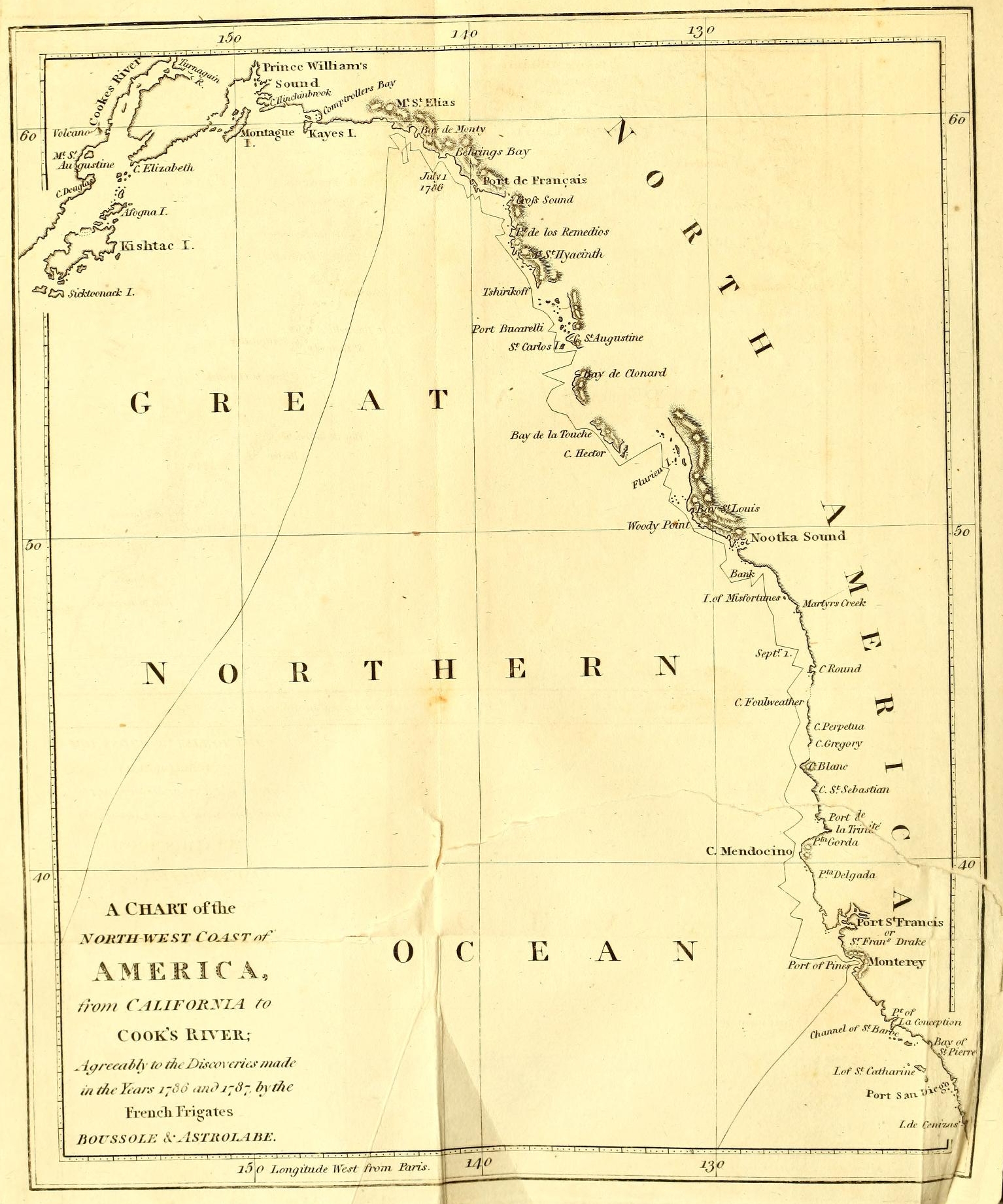

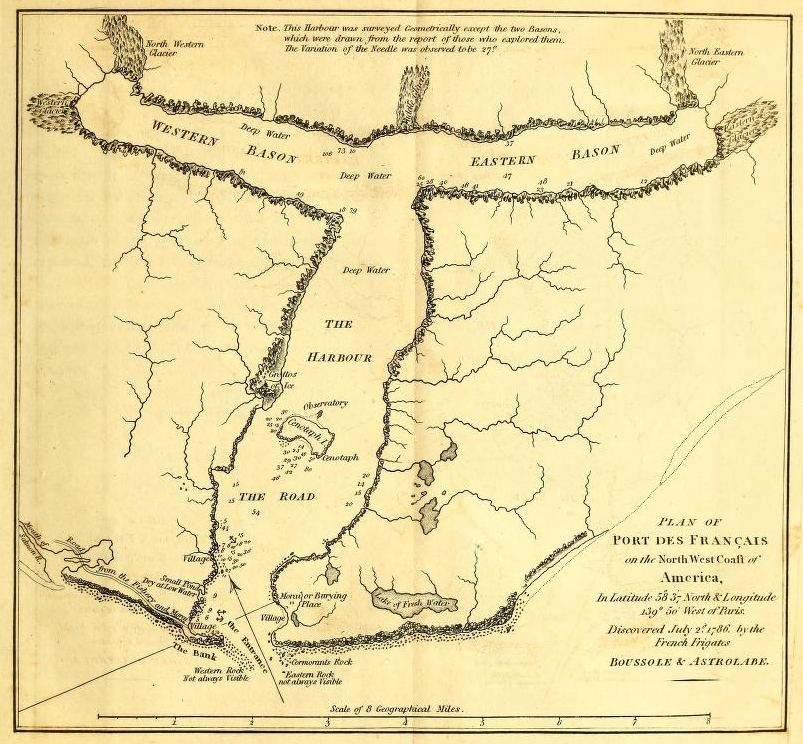

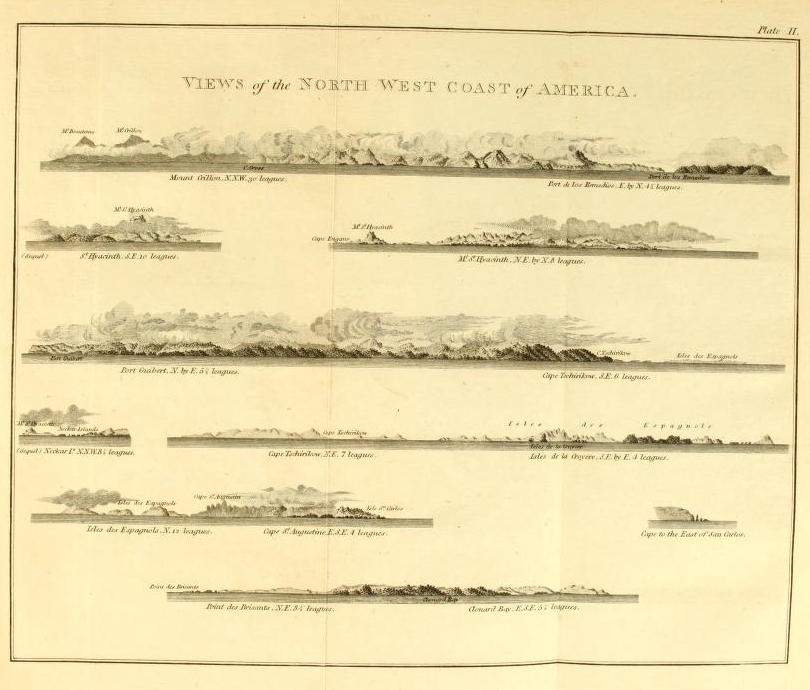

| Departure from the Sandwich Islands—Signs of approaching the American Coast—Discovery of Mount Saint-Elias—Discovery of Monti Bay—The Ships Boats reconnoitre the Entrance of a great River, to which we preserve the Name of Bebring's River—The reconnoitring of a very deep Bay—The favourable Report of many of the Officers engages us to put in there—Risks we run in entering it—The Description of this Bay, to which I give | |

VOL. II. a

[page] iv

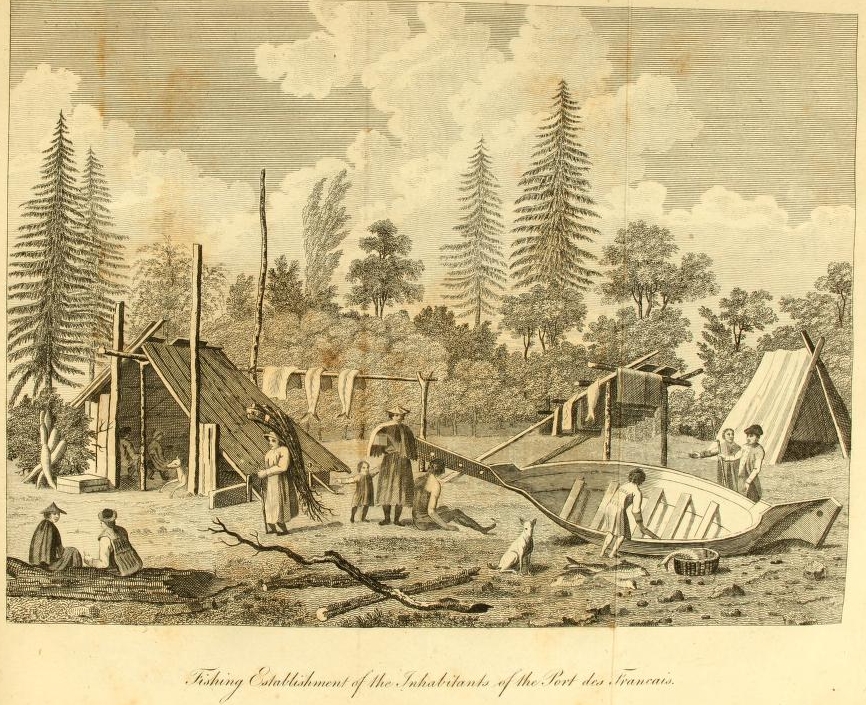

| the Name of Port des Français – Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants - Our Traffic with them—Journal of our Proceedings during our Stay | page 60. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Continuation of our Stay at Port des Français—At the Moment of our Departure from it we experience a melancholy Accident—Account of that Event—We resume our first Anchorage—Departure | page 95. |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

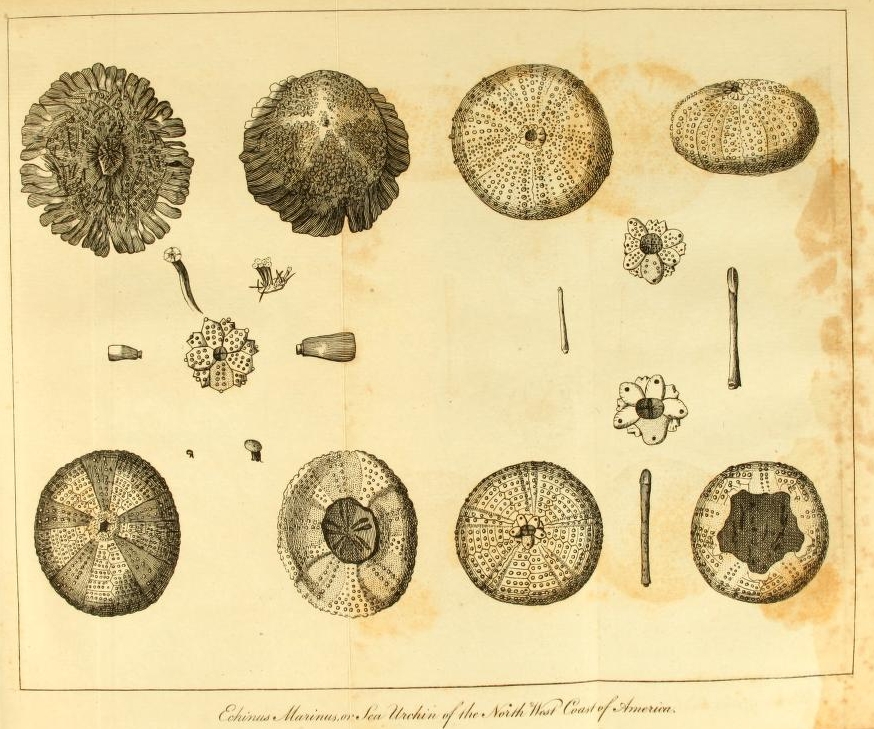

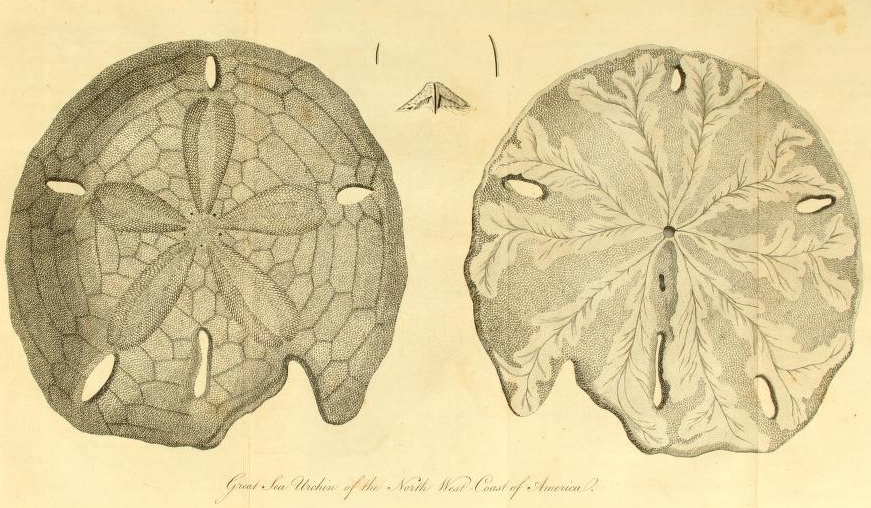

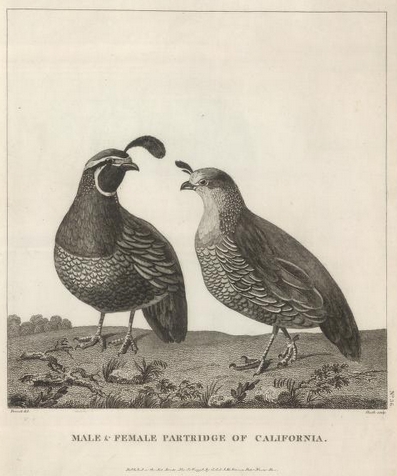

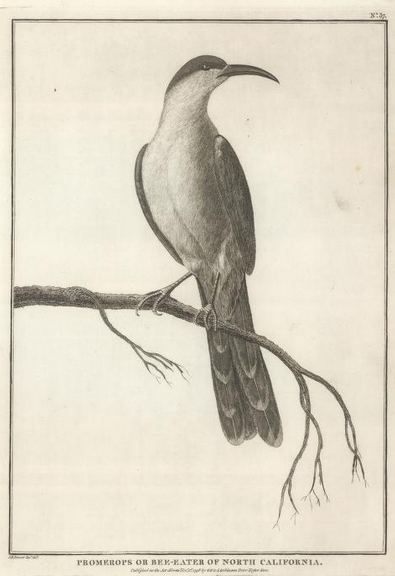

| Description of Port des Français—Its Lengitude and Latitude—Advantages and Inconveniences of this Port—Its Mineral and Vegetable Productions—Birds, Fishes, Shells, Quadrupeds—Manners and Customs of the Indians—Their Arts, Arms, Dress, and Inclination for Theft—Strong Presumption that the Russians only communicate indirectly with these People—Their Music, Dancing, and Passion for Play—Differtation on their Language | page 123. |

| CHAPTER X. | |

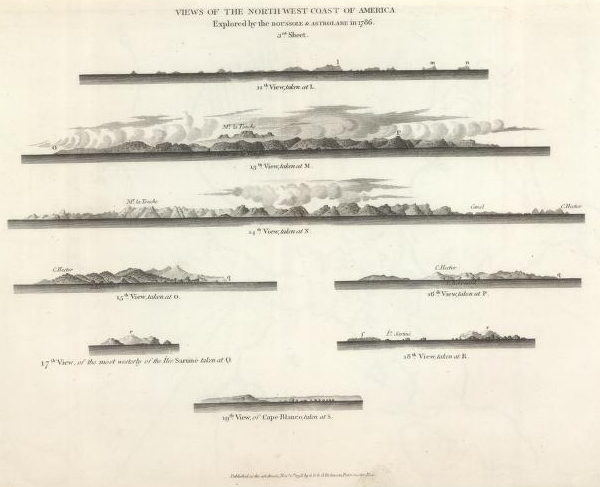

| Departure from Port des Français—Exploring of the Coast of America—Bay of Captain Cook's Islands—Port of Les Remedios, and Bucarelli, of the Pilot Maurelle—La Croyere Islands—Saint Carlos Islands—Description of the Coast from Cross as far as Cape Hector—Reconnoitring of a great | |

[page] v

| Gulph or Channel, and the exact Determination of its Breadth—Sartine Islands—Captain Cook's Woody Point—Verification of our Time keepers—Breaker's Point—Necker Islands—Arrival at Monterey | page 156. |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Description of Monterey Bay—Historical Details respecting the Two Catifernias, and their Missions—Manners and Customs of the independent Indians, and of those converted—Grains, Fruits, Pulse, of every Species—Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes, Shells, &c.—Military Constitution of these Two Provinces—Details respecting Commerce, &c. | page 194. |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Astronomical Observations—Comparison of the Refults obtained by the Distances of the Sun and Moon, and by our Time-keepers, which have served as the Basis of our Chart of the American Coast—Just Motives for thinking that our Lur deserves the Considence of Navigators—Vocabulary of the Language of the different Colonies which are in the Parts adjacent to Monterey, and Remarks on their Pronunciation | page 236. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Departure from Monterey—Plan of the Track which we proposed to follow in traversing the Western | |

a 2

[page] vi

| Ocean as far as China—Fain Research of the Island Island Noftra Senora de la Gorta—Discovery of Necker's Island—Mee', during the Night, with a funken Rock, upon which we were in danger of perishing—Description of that funken Rock—Determination of its Institude and Longitude—Vain Search after the Isles de la Mira and des Jardins—We make the Island of Assumption of the Mariannes—Description and true Situation of that Island in Latitude and Longitude—Error of the old Charts of the Manners—We fix the Longitude and Latitude of the Bashee Islands—We anchor in the Road of Macco | page 247. |

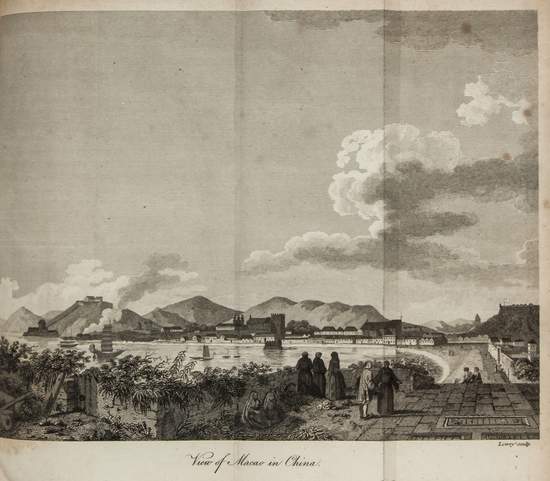

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

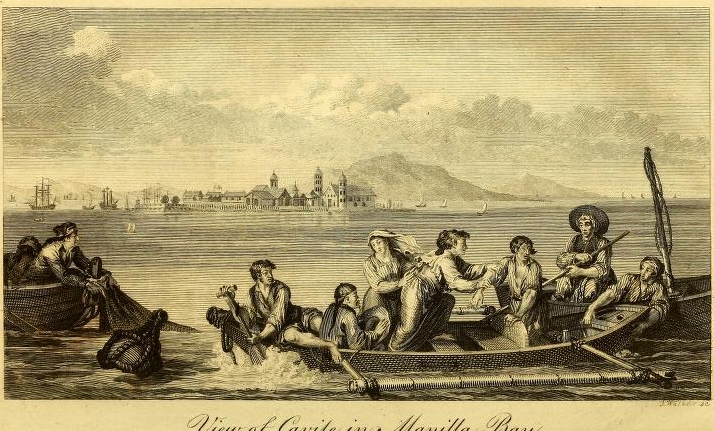

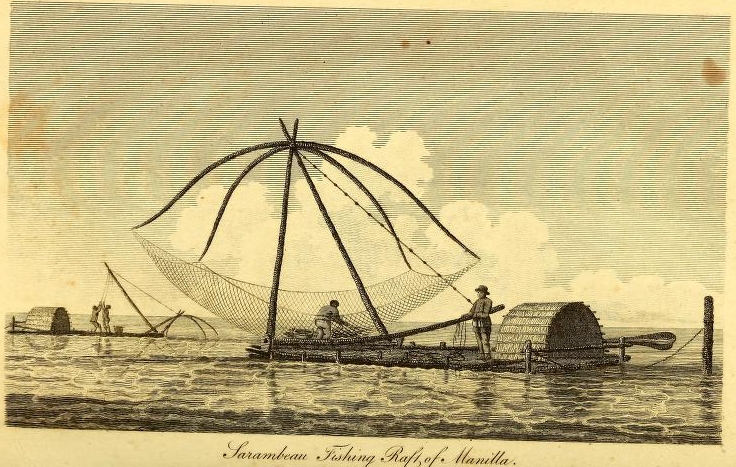

| Arrival at Mecao—Stay in the Road of Type—The Governer's obliging Reception—Description of Mecao—Its Government—Its Population—Its Relations with the Chenese—Departure from Macao—Landing on the Island of Luconia—Uncertainty of the Position of the Banks of Bulinao, Mansiloq, and Marivelle—Description of the Village of Marivelle, or Mirabelle—We enter into Manilla-Bay by the South Passage, after having in vain tried the North—Marks for turning into Manilla-Bay without Risk—Anchorage at Cavile | page 271. |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

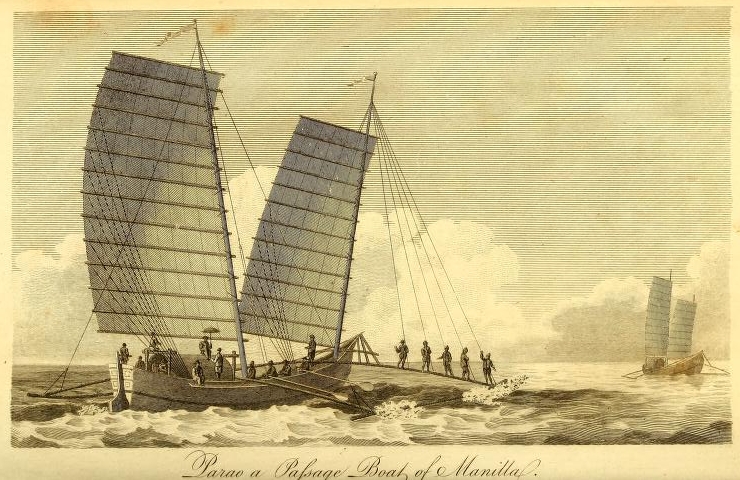

| Arrival at Cavite—Manner in which we were received by the Commandant of the Place—M Boutin, | |

[page] vii

| the Lieutenant of my Ship, is dispatched to the Governor General at Manilla—The Reception given this Officer—Details relative to Cavite, and its Arsenal—Description of Manilla, and the Parts adjacent—Its Population—Disadvantages resulting from the Government established there—Penances of which we were Witness's during Passion Week—Duty on Tobacco—Creation of the new Company of the Philippines—Reflections upon this Establishment—Details relative to the Islands south of the Philippines—Continual War with the Moors or Mahometans of these different Islands—Stay at Manilla—Military State of the Island of Luconia | page 301. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

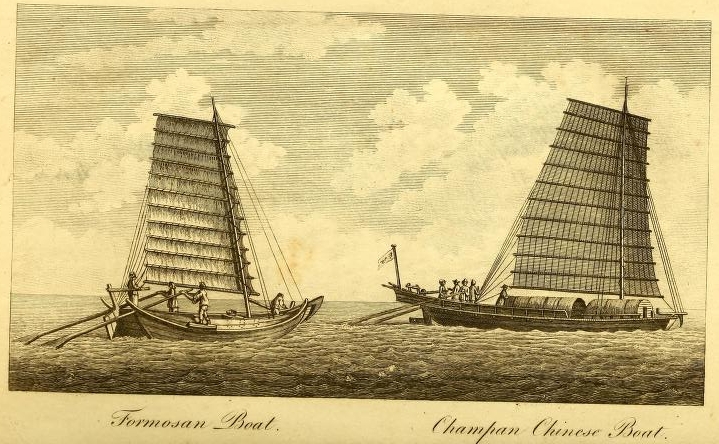

| Departure from Cavite—Meet with a Bank in the Middle of the Channel of Formosa—Latitude and Longitude of this Bank—We come to an Anchor two Leagues from the Shore off Old Fort Zealand—Get under Way the next Day—Particulars respecting the Pescadore, or Pong-hou Islands—Survey of the Island Botol Tabaco-xima—We run along Kumi Island, which makes Part of the Kingdom of Liqueo—The Frigates enter into the Sea of Japan, and run along the Coast of China—We shape our Course for Quelpaert Island—We run along the Coast of Corea, and every Day make Astronomical Observations—Particulars of Quel- | |

[page] viii

| paert Island, Corea, &c.—Discovery of Dagelet Island, its Latitude and Longitude | page 331. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

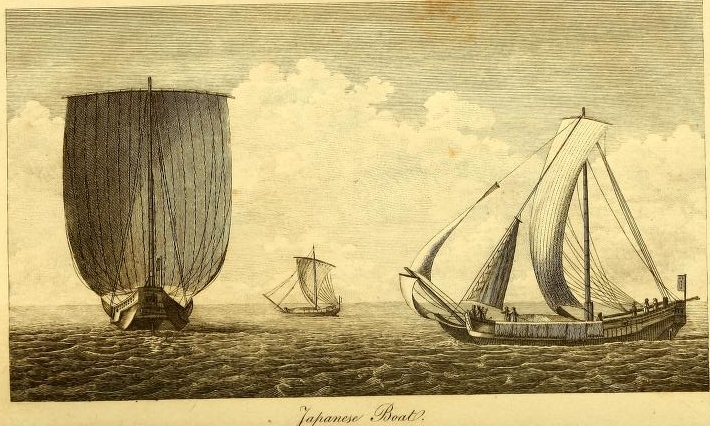

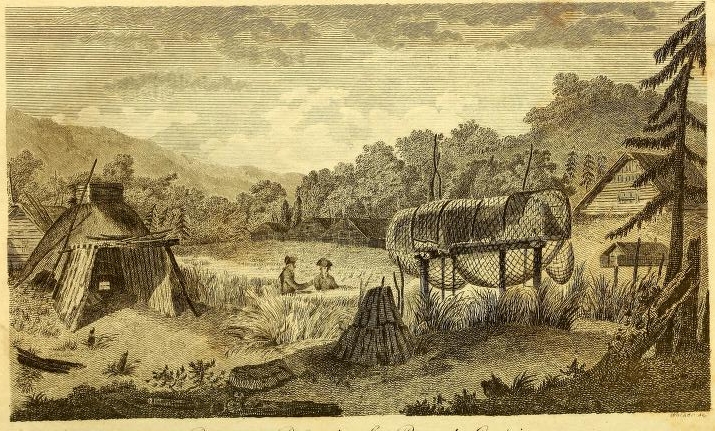

| Route towards the North-West Part of Japan—View of Cape Noto, and of the Island Jootsi sima—Details respecting this Island—Latitude and Longitude of this Part of Japan—Meet with several Japanese and Chinese Vessels—We return towards the Coast of Tartary, which we make in 42 Degrees of North Latitude—Stay at Baie de Ternai—Its Productions—Details relative to this Country—We sail from it, after a Stay of only three Days—Anchor in Baie de Suffren | page 360. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

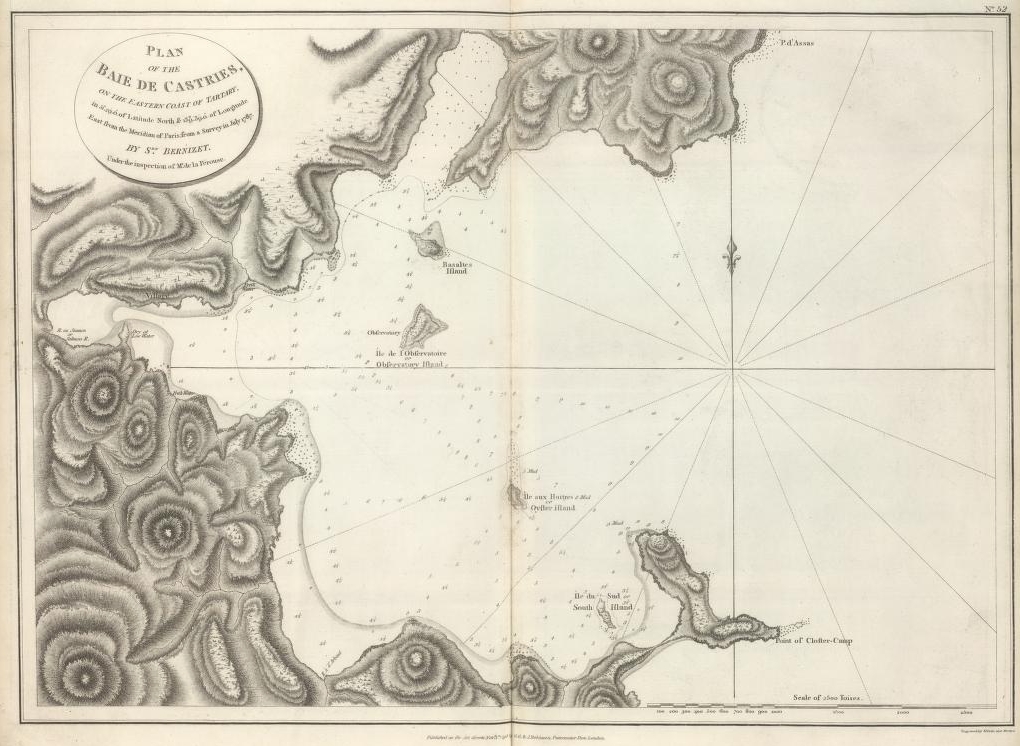

| We continue our Route to the Northward—Discovery of a Peak to the Eastward—We perceive that we were sailing in a Channel—We direct our Course towards the Coast of Segalien Island—Anchor at Baie de Langle—Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants—Their Information determines us to continue our Route to the Northward—We run along the Coast of the Island—Put into Baie d'Estaing—Departure—We find, that the Channel between the Island and the Continent of Tartary is obstructed by some Banks—Arrival at Baie de Castries, upon the Coast of Tartary | page 386. |

[page] ix

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Proceedings at Baie de Castries—Description of this Bay, and of a Tartarian Village—Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants—Their Respect for Tombs and Property—The extreme Confidence with which they inspired us—Their Tenderness for their Children—Their Union among themselves—Four Foreign Cames come into this Bay—Geographical Details given us by their Crews—Productions of Baie de Castries—Its Shells, Quadrupeds, Birds, Stones, Plants | page 422. |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

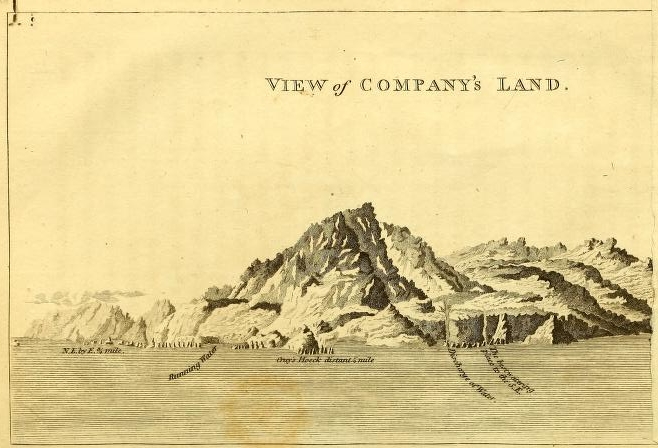

| Departure from Baie de Castries—Discovery of the Strait which dicides Jesso from Oku-Jesso—Stay at Baie de Crillon, upon the Point of the Island Toboka or Segalien—Account of the Inhabitants, and their Village—We cross the Strait, and examine all the Lands discovered by the Dutch on board the Kastricum—Staten Island—Uries Strait—Company's Land—Islands of the Four Brothers—Mareckan Island—We pass through the Kurile Islands, and shape our Course for Kamtschatka | page 446. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Supplement to the preceding Chapters—New Details relative to the Eastern Coast of Tartary—Doubt as to the pretended Pearl Fishery spoken of by the | |

I

[page] x

| Jesuits—Natural Differences between the Islanders of these Countries and the Inhabitants of Continents—Poverty of the Country—Impossibility of carrying on any useful Commerce there—Vocabulary of the Inhabitants of Toboka or Segalien Island | page 472. |

ERRATA IN VOL. II.

Page 9, line 28, for Mausoleums read Mausclea.

Page 20, Note, line 3 from bot. for des Bresses read de Brosses.

Page 69, line 26, for Six read Ten.

Page 331, line 22, for Likeu read Liquco.

Page 492, line 6 from bot. for Techicotampé re Tehikotampé.

Page 495, line 12, for Choumau read Chouma.

[page break]

[page 1]

VOYAGE

ROUND THE WORLD,

IN THE YEARS

1785, 1786, 1787, AND 1788.

CHAPTER IV.

Description of Easter Island—Occurrences there—Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants.

(APRIL 1786.)

COOK's Bay, in Easter Island, or Isle de Paque, is situated in 27° 11′ south latitude, and 111° 55′ 30″ west longitude. It is the only anchorage, sheltered from the east and south-east winds, that is to be found in these latitudes; and even here a vessel would run great risk from westerly winds, but that they never blow from that part of the horizon without previously shifting from east to north-east, to north, and so in succession to the west, which allows time to get under way; and after having stood out a quarter of a league to sea, there is no cause for apprehension. It is easy to know this bay again: after having doubled the two rocks at the south point of the island, it will be necessary to coast along a mile from the shore,

VOL. II. B

[page] 2

till a little sandy creek makes its appearance, which is the most certain mark. When this creek bears east by south, and the two rocks of which I have spoken are shut in by the point, the anchor may be let go in twenty fathoms, sandy bottom, a quarter of a league from the shore. If you have more offing, bottom is found only in thirty-five or forty fathoms, and the depth increases so rapidly that the anchor drags. The landing is easy enough at the foot of one of the statues of which I shall presently speak.

At day-break I made every preparation for our landing. I had reason to flatter myself I should find friends on shore, since I had loaded all those with presents who had come from thence over night; but from the accounts of other navigators, I was well aware, that these Indians are only children of a larger growth, in whose eyes our different commodities appear so desirable as to induce them to put every means in practice to get possession of them. I thought it necessary, therefore, to restrain them by fear, and ordered our landing to be made with a little military parade; accordingly it was effected with four boats and twelve armed foldiers. M. de Langle and myself were followed by all the passengers and officers, except those who were wanted on board to carry on the duty of the two frigates; so that we amounted to about seventy persons, including our boats crews.

[page] 3

Four or five hundred Indians were waiting for us on the shore; they were unarmed; some of them cloathed in pieces of white or yellow stuff, but the greater number naked: many were tatooed, and had their faces painted red; their shouts and countenances were expressive of joy; and they came forward to offer us their hands, and to facilitate our landing.

The island in this part rises about twenty feet from the sea. The hills are seven or eight hundred toises inland; and from their base the country shopes with a gentle declivity towards the sea. This space is covered with grass fit for the feeding of cattle; among which are large stones lying loose upon the ground: they appeared to me to be the same as those of the Isle of France, called there giraumons (pumpkins), because the greater number are of the size of that fruit: these stones, which we found so troublesome in walking, are of great use, by contributing to the freshness and moisture of the ground, and partly supply the want of the salutary shade of the trees which the inhabitants were so imprudent as to cut down, in times, no doubt, very remote, by which their country lies fully exposed to the rays of the sun, and is destitute of running streams and springs. They were ignorant, that in little islands surrounded by an immense ocean, the coolness of land covered with trees can alone stop

B 2

[page] 4

and condense the clouds, and thus attract to the mountains abundant rain to form springs and rivulets on all sides. Those islands which are deprived of this advantage are reduced to a dreadful drought, which by degrees destroying the shrubs and plants renders them almost uninhabitable. M. de Langle and myself had no doubt, that this people owed the misfortune of their situation to the imprudence of their ancestors; and it is probable, that the other islands of the South Sea abound in water, only because they fortunately contain mountains, on which it has been impossible to cut down the woods: thus the liberality of nature to the inhabitants of these latter islands appears, notwithstanding her seeming parsimony in reserving to herself these inaccessible places. A long abode in the Isle of France, which so strikingly resembles Easter Island, has convinced me, that trees never shoot again in such situations, unless they are sheltered from the sea winds, either by other trees or an enclosure of walls; and the knowledge of this fact has discovered to me the cause of the devastation of Easter Island. The inhabitants have much less reason to complain of the eruptions of their volcanoes, long since extinguished, than of their own imprudence. But as man by habit accustoms himself to almost any situation, these people appeared less miserable to me than to captain Cook and Mr. Forster. They arrived here after a long

[page] 5

and disagreeable voyage; in want of every thing, and sick of the scurvy; they found neither water, wood, nor hogs; a few fowls, bananas, and potatoes are but feeble resources in these circumstances. Their narratives bear testimony to their situation. Ours was infinitely better: the crews enjoyed the most perfect health; we had taken in at Chili every thing that was necessary for many months, and we only desired of these people the privilege of doing them good: we brought them goats, sheep, and hogs; we had seeds of orange, lemon, and cotton trees, of maize, and, in short, of every species of plants, which was likely to flourish in the island.

Our first care after landing was to form an enclosure with armed soldiers ranged in a circle; and having enjoined the inhabitants to leave this space void, we pitched a tent in it; I then ordered to be brought on shore the various presents that I intended for them, as well as the different animals: but as I had expressly forbidden the men to fire, or even keep at a distance, by the butt ends of their firelocks, such of the Indians as might be too troublesome, the soldiers soon found themselves exposed to the rapacity of the continually increasing numbers of these islanders. They were at least eight hundred; and in this number there were certainly a hundred and fifty women. The faces of these were many of them agreeable; and they

B 3

[page] 6

offered their favours to all those who would make them a present. The Indians would engage us to accept them, by themselves setting the example. They were only separated from the view of the spectators by a simple covering of the stuff of the country, and while our attention was attracted by the women, we were robbed of our hats and handkerchiefs. They all appeared to be accomplices in the robbery; for scarcely was it accomplished, than like a flock of birds they all fled at the same instant; but seeing that we did not make use of our firelocks, they returned a few minutes after, recommenced their caresses, and watched the moment for committing a new depredation: this proceeding continued the whole morning. As we were obliged to go away at night, and had so little time to employ in their education, we determined to amuse curselves with the tricks made use of to rob us; and at length, to obviate every pretence that might lead to dangerous consequences, I ordered them to restore to the soldiers and sailors the hats which had been taken away. The Indians were unarmed; three or four only, out of the whole number, had a kind of women club, which was far from being formidable. Some of them seemed to have a slight authority over the others: I took them for chiefs, and distributed medals among them, which I hung their necks by a chain; but I soon

[page] 7

found that these were the most notorious thieves; and although they had the appearance of pursuing those who took away our handkerchiefs, it was easy to perceive that they did so with the most decided intention not to overtake them.

Having only eight or ten hours to remain upon the island, and wishing to make the most of our time, I left the care of the tent and all our effects to M. Escures, my first lieutenant, giving him charge besides of all the soldiers and sailors who were on shore. We then divided ourselves into two parties; the first, under the command of M de Langle, was to penetrate as far as possible into the interior of the island, to sow seeds in all such places as might appear favourable to vegetation, to examine the soil, plants, cultivation, population, monuments, and in short every thing which might be interesting among this very extraordinary people: those who felt themselves strong enough to take a long journey, accompanied him; among these were Messieurs Dagelet, de Lamanon, Duché, Dufresne, de la Martinière, father Receveur, the Abbé Mongès, and the gardener. The second, of which I was one, contented itself with visiting the monuments, terraces, houses, and plantations within the distance of a league round our establishment. The drawing of these monuments made by Mr. Hodges was a very imperfect representation of what we saw. Mr. Forster thinks that they are the work

B 4

[page] 8

of a people much more considerable than is at present found here; but his opinion appears to mo by no means well founded. The largest of the rude busts which are upon these terraces, and which we measured, is only fourteen feet six inches in height, seven feet six inches in breadth across the shoulders, three feet in thickness round the belly, six feet broad, and five feet thick at the base; these might well be the work of the present race of inhabitants, whose numbers I believe, without the smallest exaggeration, amount to two thousand. The number of women appeared to be nearly that of the men, and the children seemed to be in the same proportion as in other countries; and although out of about twelve hundred persons, who on our arrival collected in the neighbourhood of the bay, there were at most three hundred women, I have not drawn any other conjecture from it, than that the people from the extremity of the island had come to see our ships, and that the women, either from greater delicacy, or from being more employed in the management of their family affairs and children, had remained in their houses, consequently that we saw only those who inhabit the vicinity of the bay. The narrative of M. de Langle confirms this opinion; he met in the interior of the island a great many women and children: and we all entered into those caverns in which Mr. Forster and some officers of captain

[page] 11

Cook thought at first that the women might be concealed. These are subterraneous habitations, of the same form as those which I shall presently describe, and in which we found little faggots, the largest piece of which was not five feet in length, and did not exceed fix inches in diameter. It is however certain, that the inhabitants hid their women when captain Cook visited them in 1772; but it is impossible for me to guess the reason of it, and we are indebted, perhaps, to the generous manner in which he conducted himself towards these people, for the confidence they put in us, which has enabled us to form a more accurate judgment of their population.

All the monuments which are at this time in existence, and of which M. Duché has given a very exact drawing, appeared to be very ancient; they are situated in morais (or burying places) as far as we can judge from the great quantity of bones which we found hard by. There can be no doubt that the form of their present government may have so far equalized their condition, that there no longer exists among them a chief of sufficient authority to employ a number of men in erecting a statue to perpetuate his memory. These colossal images are at present superseded by small pyramidal heaps of stones, the topmost of which is whitewashed. These species of mausoleums, which are only the work of an hour for a single man,

4

[page] 10

are piled up upon the sea shore; and one of the natives shewed us that these stones covered a tomb, by laying himself down at full length on the ground; afterwards, raising his hands towards the sky, he appeared evidently desirous of expressing that they believed in a future state. I was upon my guard gainst this opinion, but having seen this sign repeated by many, and M. de Langle, who had penetrated into the interior of the island, having reported the same fact, I no longer entertained a doubt of it, and I believe that all our officers and passengers partook in this opinion; we did not however perceive traces of any worship, for I do not think that any one can take the statues for idols, although these Indians may have shewed a kind of veneration for them. These busts of colloffal size, the dimensions of which I have already given, and which strongly prove the small progress they have made in sculpture, are formed of a volcanic production known to naturalists by the name of Lapillo: this is so soft and light a stone, that some of captain Cook's officers thought it was artificial, composed of a kind of mortar which had been hardened in the air. No more remains, but to explain how ic was possible to raise, without engines, so very considerable a weight; but as it is certainly a very light volcanic stone, it would be easy, with levers five or fix toises long, and by slipping stones underneath, as captain Cook very

[page] 11

well explains it, to lift a much more considerable weight; a hundred men would be sufficient for this purpose, for indeed there would not have been room for more. Thus the wonder disappears; we restore to nature her stone of Lapillo, which is not factitious; and have reason to think, that if there are no monuments of modern construction in the island, it is because all ranks in it are become equal, and that a man has but little temptation to make himself king of a people almost naked, and who live on potatoes and yams; and on the other hand, these Indians not being able to go to war from the want of neighbours, have no need of a chief.

I can only hazard conjectures upon the manners of this people, whose language I did not understand, and whom I saw only during the course of one day; but possessing the experience of former navigators, from an acquaintance with their narratives, I was able to add to them my own observations.

Scarcely a tenth part of the land in this island is under cultivation; and I am persuaded that three days labour of each Indian is sufficient to procure their annual subsistence. The ease with which the necessaries of life are provided induced me to think, that the productions of the earth were in common. Besides, I am nearly certain the houses are common, at least to a whole village or dis-

[page] 12

trict. I measured one of those houses near our tent*; it was three hundred and ten feet in length, ten feet broad, and ten feet high in the middle; its form was that of a canoe reversed: the only entrances were by two doors, two feet high, through which it was necessary to creep on hands and feet. This house is capable of containing more than two hundred persons: it is not the dwelling of any chief, for there is not any furniture in it, and so great a space would be useless to him; it forms a village of itself, with two or three small houses at a little distance from it. There is, probably, in every district a chief, who superintends the plantations. Captain Cook thought that this chief was the proprietor of it; but if this celebrated navigator found some difficulty in procuring a considerable quantity of yams and potatoes, it ought rather to be attributed to the scarcity of these eatables, than to the necessity of obtaining an almost general consent to their being sold.

As for the women, I dare not decide whether they are common to a whole district, and the children to the republic: certain it is that no Indian appeared to have the authority of a husband over any one of the women, and if they are private property, it is a kind of which the possessors are very liberal.

* This house was not then finished; so that captain Cook could not possibly have seen it.

[page] 13

I have already mentioned, that some of the houses are subterraneous; but others are built with reeds, which proves that there are marshy places in the interior of the island. The reeds are very skilfully arranged, and are a sufficient defence against the rain. The building is supported by pillars of cut stone*, eighteen inches thick; in these, holes are bored at equal distances, through which pass long poles, which form an arched frame; the space between is filled up with reed thatch.

There can be no doubt, as captain Cook observes, of the identity of this people with that of the other islands of the South Sea: they have the same language, and the same cast of features: their cloth is also made of the bark of the mulberry tree; but this is very scarce, on account of the drought, which has destroyed those trees. The few remaining are only three feet high; and even these are obliged to be surrounded with fences to keep off the wind, for the trees never exceed the height of the wall by which they are sheltered.

I have no doubt, that formerly these people enjoyed the same productions as those of the Society Islands. The fruit trees must have perished from the drought, as well as the dogs and hogs, to whom water is absolutely necessary. But man, who in Hudson's Streights drinks the oil of the

* These are not freestone, but compact lava.

[page] 14

whale, accustoms himself to every thing, and I have seen the natives of Easter Island drink the sea water like the albatrosses at Cape Horn. We were there in the rainy season, and a little brackish water was found in some holes on the sea shore; they offered it to us in their calabashes, but it disgusted even those who were most thirsty. I do not expect, that the hogs which I have given them will multiply; but I have great hopes, that the sheep and goats, which drink but little, and are fond of salt, will prosper among them.

At one o'clock in the afternoon I returned to the tent, with the intention of going on board, in order that M. de Clonard, the next in command, might, in his turn, come on shore: I there found almost every one without either hat or handkerchief; our forbearance had emboldened the thieves, and I had fared no better than the rest. An Indian who had assisted me to get down from a terrace, after having rendered me this service, took away my hat, and fled at full speed, followed as usual by the rest. I did not order him to be pursued, not being willing to have the exclusive right of being protected from the sun, and observing that almost every person was without a hat, I continued to examine the terrace, a monument that has given me the highest opinion of the abilities of the earlier inhabitants for building, for the pompous word architecture cannot with propriety be made use of here.

5

[page] 15

It appears that they have never had the least knowledge of any cement, but they cut and divide the stones in the most perfect manner: they were also placed and joined together according to all the rules of art.*

I made a collection of specimens of these stones; they consist of lava of different compactness. The lightest, and that which consequently would be the soonest decomposed, forms the outer soil in the interior of the island; that which is next the sea consists of a lava much more compact, so as to make a longer resistance; but I do not know any instrument or matter hard enough, in the possession of these islanders, to cut the latter stones; perhaps a longer continuance on the island might have furnished me with some explanations on this subject. At two o'clock I returned on board and M. de Clonard went on shore. Soon afterwards two officers of the Astrolabe arrived, to inform me that the Indians had just committed a new theft, which might be attended with more serious consequences. Some divers had cut under water the small cable of the Astrolabe's boat, and had taken away her grapnel, which had not been discovered till the robbers were pretty far advanced into the interior of the island. As this grapnel was necessary to us, two officers and several soldiers pursued them; but they were assailed by a shower of stones. A musket, loaded with powder,

[page] 16

and fired in the air, had no effect; they were at length under the necessity of firing one with small shot, some grains of which doubtless struck one of those Indians, for the stoning ceased, and our officers were able peaceably to regain our tent; but it was impossible to overtake the robbers, who must have been astonished at not having been able to weary our patience.

They soon returned around our tent, recommenced the offers of their women, and we were as good friends as at our first interview. At length, at six in the evening, every thing was reembarked, the boats had returned on board, and I made the signal to prepare for sailing. Before we got under way, M. de Langle gave me an account of his journey into the interior of the island, which I shall relate in the following chapter: he had sown the seeds in different parts of the road, and had given the islanders proofs of the greatest good will towards them. I will, however, finish their portrait by relating, that a sort of chief, to whom M. de Langle made a present of a he and she goat, received them with one hand, and robbed him of his handkerchief with the other.

It is certain, that these people have not the same ideas of theft that we have; with them, probably no shame is attached to it; but they very well knew, that they committed an unjust action, since they immediately took to flight, in order to avoid

[page] 17

the punishment which they doubtless feared, and which we should certainly have inflicted on them in proportion to the crime, had we made any considerable stay in the island; for our extreme lenity might have ended by producing disagreeable consequences.

No one, after having read the narratives of the later navigators, can take the Indians of the South Sea for savages; they have on the contrary made very great progress in civilization, and I think them as corrupt as the circumstances in which they are placed will allow them to be. This opinion of them is not founded upon the different thefts which they committed, but upon the manner in which they effected them. The most hardened rogues of Europe are not such great hypocrites as these islanders; all their caresses were feigned; their countenances never expressed a single sentiment of truth; and the man of whom it was necessary to be most distrustful, was the Indian to whom a present had that moment been made, and who appeared the most eager to return for it a thousand little services.

They brought to us by force young girls of thirteen or fourteen years of age, in the hope of receiving pay for them; the repugnance of those young females was a proof, that in this respect the custom of the country was violated. Not a single Frenchman made use of the barbarous right which

VOL. II. C

[page] 18

was given him; and if there were some moments dedicated to nature, the desire and consent were mutual, and the women made the first advances.

I found again in this country all the arts of the Society Isles, but with much fewer means of exercifing them, for want of the raw materials. Their canoes have also the same form, but they are composed only of very narrow planks, four or five feet long, and at most can carry but four men. I have only seen three of them in this part of the island, and I should not be much surprised, if in a short time, for want of wood, there should not be a single one remaining there. They have besides learned to make shift without them; and they swim so expertly, that in the most tempestuous sea they go two leagues from the shore, and in returning to land, often, by way of frolic, choose those places where the surf breaks with the greatest fury.

The coast appeared to me not to abound much in fish, and I believe that the inhabitants live chiefly on vegetables; their food consists of potatoes, yams, bananas, sugar canes, and a small fruit which grows upon the rocks on the sea-shore, similar to the grapes that are found in parts adjacent to the tropic in the Atlantic Ocean; the few sowls that are found upon the island cannot be considered as a resource. Our navigators did not meet with any land bird, and even sea sowl are not very common.

[page] 19

The fields are cultivated with a great deal of skill. They root up the grass, lay it in heaps, burn it, and thus fertilize the earth with its ashes. The banana trees are planted in a straight line. They also cultivate the garden nightshade, but I am ignorant what use they make of it; if I knew they had vessels which could stand fire, I should think, that, as at Madagascar or the Isle of France, they eat it in the same manner as they do spinage; but they have no other method of cooking their provision than that of the Society Isles, which consists in digging a hole, and covering their yams and potatoes with red hot stones and embers, mixed with earth, so that every thing which they eat is cooked as in an oven.

The exactness with which they measured the ship showed, that they had not been inattentive spectators of our arts; they examined our cables, anchors, compass, and wheel, and they returned the next day with a cord to take the measure over again, which made me think, that they had had some discussions on shore upon the subject, and that they had still doubts relative to it. I esteem them far less, because they appeared to me capable of reflection. One reflection will, perhaps, escape them, namely, that we employed no violence against them; though they were not ignorant of our being armed, since the mere presenting a firelock in sport made them run away: on the contrary,

C 2

[page] 20

we landed on the island only with an intention to do them service; we heaped presents upon them, we caressed the children; we sowed in their fields all kinds of useful seeds; presented them with hogs, goats, and sheep, which probably will multiply; we demanded nothing in return: nevertheless they threw stones at us, and robbed us of every thing which it was possible for them to take away. It would, perhaps, have been imprudent in other circumstances to conduct ourselves with so much lenity; but I had resolved to go away in the evening, and I flattered myself that at day-break, when they no longer perceived our ships, they would attribute our speedy departure to the just displeasure we entertained at their proceedings, and that this reflection might amend them; though this idea is a little chimerical, it is of no great consequence to navigators, as the island* offers scarcely any resource to ships that may touch there, besides being at no great distance from the Society Isles.

* Easter Island, discovered in 1722 by Roggewein, appears, according to Pérouse, to have experienced a reverse in its population, and in the products of its soil: this at least might be inferred from the remarkable difference in the accounts of these two navigators. The reader who may be desirous to reconcile them ought to consult The Voyage of Roggewein, printed at the Hague in 1739, or the extract which the president Des Brosses has given of it in his work, intitled, Histoire des Navigations aux Terres Australes, vol. ii, page 226, and following.—(Fr. Ed.)

[page] 21

CHAPTER V.

Journey of M. de Langle into the Interior of Easter Island—New Observations upon the Manners and the Arts of the Natives, upon the Quality and Cultivation of the Soil, &c.

(APRIL 1786.)

"I SET out at eight o'clock in the morning, accompanied by Messrs. Dagelet, de Lamanon, Dufresne, Duché, the abbé Mongès, father Receveur, and the gardener; we bent our course from the shore two leagues to the eastward, towards the interior of the island; the walk was very painful, across hills covered with volcanic stones; but I soon perceived that there were foot paths, by which we might easily proceed from house to house; we availed ourselves of these, and visited many plantations of yams and potatoes. The soil of these plantations consisted of a very fertile vegetable earth, which the gardener judged proper for the cultivation of our feeds: he sowed cabbages, carrots, beets, maize, and pumpkins; and we endeavoured to make the islanders understand, that these seeds would produce roots and fruits which they might eat. They perfectly comprehended us, and from that moment pointed out to us the best spots, signifying to us the places in which they were desirous of seeing our new

C 3

[page] 22

productions. We added to the leguminous plants, seeds of the orange, lemon, and cotton trees, making them comprehend, that these were trees, and that what we had before sown were plants.

"We did not meet with any other small shrubs than the paper mulberry tree*, and the mimosa. There were also pretty considerable fields of garden nightshade, which these people appeared to me to cultivate in the lands already exhausted by yams and potatoes. We continued our route towards the mountains, which, though of considerable height, are all easy of access, and covered with grass; we perceived no marks of any torrent or ravine. After having gone about two leagues to the east, we returned southward towards the shore which we had coasted the evening before, and upon which, by the assistance of our telescopes, we had perceived a great many monuments: several were overthrown; it appeared that these people did not employ themselves in repairing them; others were standing upright, their bases half destroyed. The largest of those that I measured was sixteen feet ten inches

* Morus Papyrifera, abounding in Japan, where they prepare the bark of it to use as paper. This bark, being extremely fibrous, serves the women of Louisiana to make different works with the silk which they draw out of it: the leaf is good for the nourishment of silk-worms. This tree now grows in France.—(Fr. Ed.)

[page] 23

in height, including the capital, which was three feet one inch, and which is of a porous lava, very light; its breadth over the shoulders was six feet seven inches, and its thickness at the base two feet seven inches.

"Having perceived a small village, I directed my course towards it; one of the houses was three hundred feet in length, and in the form of a canoe reversed. Very near this place we observed the foundations of several others, which no longer existed; they are composed of stones of cut lava, in which are holes about two inches across. This part of the island appeared to us to be in a much better state of cultivation, and more populous, than the parts adjacent to Cook's Bay. The monuments and terraces were also in greater number. We perceived upon some of the stones, of which those terraces are composed, some rude sculptures of skeletons; and we also saw there holes which were stopped up with stones, by which we imagined, that they might form a communication with the caverns containing the bodies of the dead. An Indian explained to us, by very expressive signs, that they deposited them there, and that afterwards they ascended to heaven. We found upon the sea-shore pyramids of stones, ranged very nearly in the same form as cannon balls in a park of artillery, and we perceived some human bones in the vicinity of those pyra-

C 4

[page] 24

mids, and of those statues, all of which had the back turned towards the sea. In the morning we visited seven different terraces, upon which there were statues, some upright, others thrown down, differing from each other only in size; the injuries of time were more or less apparent on them, according to their antiquity. We found near the farthest a kind of mannikin of reed, representing a human figure, ten feet in height; it was covered with a white stuff of the country, the head of a natural size, but the body slender, the limbs in nearly exact proportion; from its neck hung a net, in the shape of a basket, covered with white stuff, which appeared to be filled with grass. By the side of this bag was the image of a child, two feet in length, the arms of which were placed across, and the legs pendent. This mannikin could not have existed many years; perhaps it was a model of some statues to be erected in honour of the chiefs of the country. Near this same terrace there were two parapets, which formed an enclosure of three hundred and eighty-four feet in length, by three hundred and twenty-four in breadth: we were not able to ascertain whether it was a reservoir for water, or the beginning of a fortress; but it appeared to us, that this work had never been finished.

[page] 25

"Continuing to bend our course to the west, we met about twenty children, who were walking under the care of some women, and who appeared to go towards the houses of which I have already spoken.

"At the south end of the island we saw the crater of an old volcano, the size, depth, and regularity of which excited our admiration; it is in the shape of a truncated cone; its superior base, which is the largest, appeared to be more than two thirds of a league in circumference: the lower base may be estimated, by supposing that the side of the cone makes with the axis an angle of about 30°. This lower base forms a perfect circle; the bottom is marshy, containing large pools of fresh water, the surface of which appeared to be above the level of the sea; the depth of this crater is at least eight hundred feet.

"Father Receveur, who descended into it, related to us, that this marsh was surrounded by some beautiful plantations of banana and mulberry trees. It appears, according to our observations in sailing along the coast, that a considerable portion of it has rolled down on the side next the sea, thus occasioning a great breach in the crater; the height of this breach is one third of the whole cone, and its breadth a tenth of the upper circumference. The grass which has sprung up on the sides of the cone, the swamps which are at the bottom, and the fer-

[page] 26

tility of the adjacent lands, are proofs that the subterraneous fires have a long time been extinct*. The only birds which we met with in the island we saw at the bottom of the crater; these were terns. Night obliged me to return towards the ships. We perceived near a house a great number of children, who ran away at our approach: it appeared to us probable, that this house was the habitation of all the children of the district. There was too little difference in their ages for them all to belong to the two women who seemed to be charged with the care of them. There was near this house a hole in the earth, in which they cooked yams and potatoes, according to the manner practised in the Society Isles.

"On our return to the tent, I presented to three of the natives the three different species of animals which we had destined for them.

"These islanders are hospitable; they several times presented us with potatoes and sugar canes; but they never let an opportunity slip of robbing us, when they could do it with impunity. Scarcely a tenth part of the island is cultivated; the lands which are cleared are in the form of a regular oblong, and without any kind of enclosure:

* "There is on the edge of the crater, on the side towards the sea, a statue, almost entirely destroyed by time, which proves that the volcano has been extinct for several ages."

[page] 27

the remainder of the island, even to the summit of the mountains, is covered with a coarse grass. It was the rainy season when we were there, and we found the earth moistened at least a foot deep; some holes in the hills contained a little fresh water, but we did not find in any part the least appearance of a stream. The land seemed to be of a good quality, and there would be a far more abundant vegetation if it were watered. We did not obtain from these people the knowledge of any instrument, which they used for the cultivation of their fields. Probably, after having cleared them, they dig holes in them with wooden stakes, and in this manner plant their yams and potatoes. We very rarely met with a few bushes of mimosa, whose largest branches are only three inches in diameter. The most probable conjectures that can be formed as to the government of these people are, that they consist only of a single nation, divided into as many districts as there are morais, because it is to be observed, that the villages are built near those burying places. The products of the earth seem to be common to all the inhabitants of the same district; and as the men, without any regard to delicacy, make offers of the women to strangers, it is natural to suppose, that they do not belong to any man in particular; and that when the children are weaned, they are delivered over to the management of other women,

[page] 28

who, in every district, are charged with the care of bringing them up.

"Twice as many men are met with as women, and if indeed the latter are not less numerous, it is because they keep more at home than the men. The whole population may be estimated at two thousand people; several houses that we saw building, and a great number of children, ought to induce a belief that it does not diminish; there is however reason to think, that the population was more considerable when the island was better wooded. If these islanders had industry enough to build cisterns, they would thereby remedy one of the greatest misfortunes of their situation, and perhaps they would prolong their lives. There is not a single man seen in this island who appears to be above the age of sixty-five, if we can form any estimate of the age of people with whom we are so little acquainted, and whose manner of life differs so essentially from our own."

[page] 29

CHAPTER VI.

Departure from Easter Island—Astronomical Observations—Arrival at the Sandwich Islands—Anchorage in the Bay of Keriporepo, in the Island of Mowée—Departure.

(APRIL, MAY, JUNE, 1786.)

ON taking our departu from Cook's Bay in Easter Island, on the 10th in the evening, I stood to the northward, and coasted along the island a league from the shore, by moon-light. We did not lose sight of it till the next day at two o'clock, when we were about twenty leagues off. The wind till the 17th was constantly at south east, and east south east. The weather was extremely clear; it neither changed nor was overcast till the wind shifted to the east north east, in which point it continued from the 17th to the 20th, when we began to catch bonetas, which continued to follow our frigates to the Sandwich Islands, and furnished almost every day, during six weeks, a complete allowance for the ships companies. This wholesome food preserved us in good health; and after being ten months at sea, during which we had been only twenty-five days in port, we had not a sick person on board the two ships. We traversed unknown seas; our course was very nearly parallel

[page] 30

to that of captain Cook in 1777, when he sailed from the Society Islands for the north-west coast of America; but we were about eight hundred leagues more to the eastward. I flattered myself, that in a distance of near two thousand leagues, I should make some discovery; sailors were continually at the mast-head, and I had promised a reward to him who should first discover land. For the purpose of overlooking a greater space, our ships kept abreast of each other during the day, leaving between them an interval of three or four leagues.

M. Dagelet, in this run, never neglected an opportunity of making lunar observations; their agreement with the time-keepers of M. Berthoud was so exact, that the difference was never more than from ten to fifteen minutes of a degree; they mutually confirmed each other. M. de Langle's calculations were equally satisfactory; and we every day knew the set of the currents, by the difference between the longitude by account, and the longitude by observation; they carried us one degree to the south west, at the rate of about three leagues in twenty-four hours; and afterwards changed to the east, running with the same rapidity, till in seven degrees north, when they again took their course to the westward; and on our arrival at the Sandwich Islands, our longitude by account differed nearly five degrees from

[page] 31

that by observation, so that if, like the ancient navigators, we had had no means of ascertaining the longitude by observation, we should have placed the Sandwich islands 5° more to the eastward. It is, without doubt, from the set of the currents, formerly so little observed, that all the errors in the Spanish charts have originated; for it is remarkable, that of late the greater part of the islands discovered by Quiros, Mendana, and other navigators of that nation, have been found again, but always placed upon their charts too near the coast of America. I ought also to add, that if the vanity of our pilots had not a little suffered from the difference that was daily found between the longitude by account, and that by observation, it is very probable that we should have had an error of eight or ten degrees on our making the land, and consequently, that in times less enlightened, we should have placed the Sandwich Islands ten degrees more to the eastward.

These reflections left much doubt on my mind as to the existence of the cluster of islands called by the Spaniards La Mesa, Los Majos, La Disgraciada. Upon the chart that admiral Anson took on board the Spanish galleon, and which the editor of his voyage has caused to be engraved, this cluster is placed precisely in the same latitude as the Sandwich Islands, and 16 or 17° more to the eastward. My daily differences of longitude

1

[page] 32

made me think, that these islands were the same*; but what completely convinced me, was the name

* In the course of the years 1786 and 1787, captain Dixon anchored three times at the Sandwich Islands; and having the same doubt as La Pérouse with regard to the identity of these islands, and those called Los Majos, La Mesa, &c. he made researches in consequence; his results were perfectly similar, as may be seen by the following extracts:

"The islands Los Majos, La Maso, and St. Maria la Gorta, laid down by Mr. Roberts, from 18° 30′ to 28° north latitude, and from 135° to 149° west longitude †, and copied by him from a Spanish manuscript chart, were in vain looked for by us, and, to use Maurelle's words, "it may be pronounced that no such islands are to be found;" so that their intention has uniformly been to mislead rather than be of service to future navigators."

"Our observation at noon, on the 8th of May, gave 17° 4′ north latitude, and 129° 57′ west longitude; in this situation we looked for an island called by the Spaniards Roco Partida, but in vain; however, we stood to the northward under an easy sail, and kept a good look out, expecting soon to fall in with the group of islands already mentioned.

From the 11th to the 14th we lay to every night, and when we made sail in the morning, spread at the distance of eight or ten miles, standing westerly: it being probable that though the Spaniards might have been pretty correct in the latitude of these islands, yet they might easily be mistaken several degrees in their longitude: but our latitude on the 15th, at noon, being 20° 9′ north, and 140° 1′ west longitude, which is considerably to the westward of any island laid down by the Spaniards, we concluded, and with reason, that there must be some gross mistake in their chart."

"On the 1st of November we looked out for St. Maria le Gorta, which is laid down in Cook's chart in 27° 50′ north latitude, and in 149° west longitude; and the same afternoon, sailed directly over it. Indeed we scarcely expected to meet with any such place, as it is copied by Mr. Roberts into the above chart from the same authority which we had already sound to be erroneous respecting Los Majos and Roco Partida."

† It must be observed, that Dixon reckons his longitude from the west, whereas Cook, in his third voyage, reckons it the opposite way; Dixon's reason without doubt is, that, having shaped his course to the westward in doubling Cape Horn, this manner of reckoning was more natural and more convenient to him.

[page] 33

of Mesa, which signifies table, given by the Spaniards to the island of Owhyhee. I had read in the description of this same island by captain King, that, after having doubled the eastern point, they discovered a mountain called Mowna-roa, which was visible at a great distance: it is, says he, flattened at the summit, and forms what French mariners call plateau. The English expression is still more signicant, for captain King calls it Table-land.

Although the season was very far advanced, and I had no time to lose in order to reach the American coasts, I determined at all events to shape a course which might bring my opinion to the proof; the result, if I were in error, would necessarily be, to meet with a second cluster of islands, forgotten perhaps by the Spaniards for more

VOL. II. D

[page] 34

than a century, and to determine their situation, and their precise distance from the Sandwich islands. Those who know my character cannot suspect, that I have been influenced in this research by the desire of taking away from captain Cook the honour of this discovery. Full of respect and admiration for the memory of that great man, he will always appear to me the greatest of navigators; and he who has determined the exact situation of these islands; who has explored their coasts; who has made us acquainted with the manners, customs, and religion of the inhabitants; and who has paid with his blood for all the knowledge of which we are at this time in possession respecting these people; he is, I say, the true Columbus of this country, of the coast of Alashka, and of almost all the islands of the South Sea. Chance sometimes makes discoveries to the most ignorant; but it belongs only to great men like him, to leave no more information to be desired concerning the countries they have seen. Mariners, philosophers, naturalists, each find in their voyages something which is the object of their peculiar study; all men perhaps, at least all navigators, owe a tribute of praise to his memory: how can I refuse it, at the moment of reading those islands, where he so unfortunately finished his career?.

On the 7th of May, in 8° north latitude, we

2

[page] 35

perceived a great many birds of the petrel species, man of war, and tropic birds; these last two species, it is said, seldom go any great distance from land; we also saw a great many turtles pass alongside. The Astrolabe caught two of them, which they shared with us, and which we found very good. The birds and turtles followed us as far as 14°, and I doubt not but we passed some island which was probably uninhabited; for a rock in the middle of the sea would rather be a place of resort for these animals than a cultivated country. We were now very near Rocca-Partida and la Nublada: I shaped my course so as to pass almost in sight of Rocca-Partida, if its lon gitude were justly determined; but I did not wish to run past its latitude, not being able to spare from my other schemes a single day to this research. I knew very well, that in this way it was probable I should miss it, and I was not much surprised at not finding it. When we had crossed its latitude the birds disappeared, and till my arrival at the Sandwich Islands, a space of five hundred leagues, we never saw more than two or three in a day.

On the 15th I was in 19° 17′ north latitude, and 130° west longitude, that is to say, in the same latitude as the cluster of islands laid down in the Spanish charts, as well as in that of the Sandwich Islands,

D 2

[page] 36

but a hundred leagues more to the eastward than the former, and four hundred and sixty to the eastward of the latter. Thinking to render an important service to geography if I could succeed in taking away from the charts these idle names, which point out islands that have no existence, and perpetuate errors which are very prejudicial to navigation, I was desirous, in order to leave no doubt, to prolong my track as far as the Sandwich Islands; I even formed the design of passing between the island of Owhyhee and that of Mowee, which the English had not been able to explore; and I proposed to land at Mowee, to traffic there with the inhabitants for some supplies of fresh stock, and leave it without loss of time. I knew, that by partially following my plan, and only running down 200 leagues on this parallel, there would still be unbelievers, and I wished that not the slightest objection should remain.

On the 18th of May I was in 20° north latitude, and 139° west longitude, precisely upon the Spanish island Disgraciada, where I met with no sign of land.

On the 20th I passed through the middle of the supposed cluster of Los Majos, without perceiving signs of being near any island: I continued to run to the westward upon this parallel between 20° and 21°: at length, on the 28th in the morning,

[page] 37

I got sight of the mountains of the island of Owhyhee, which were covered with snow, and seon afterwards of those of Mowee, which are not quite so high. I crowded all the fail I could in order to near the land, but when night came on I was still seven or eight leagues from it. I passed the time till morning in standing off and on waiting for day, in order to run into the channel formed by these two islands, and to seek for an anchorage to leeward of Mowee, near the island of Morokinne. Our longitude by observation corresponded so exactly with that of captain Cook, that after having pricked off the ship's place upon the chart by our bearings, according to the English method, we found only 10′ difference, which we were more to the eastward.

At nine in the morning I saw the point of Mowee bearing west 15° north. I perceived also an island bearing west 22° north, which the English had not been able to get sight of, and is not found in their chart, which in this part is very defective; whilst every thing that they have laid down from their own observations is deserving of the warmest praise. The appearance of the island of Mowee was delightful, I coasted it along at about a league distance; it projects into the channel in the direction of south-west by west: we saw cascades falling from the summits of the mountains, and de-

D 3

[page] 38

scending to the sea, after having watered the habitations of the natives, which are so numerous, that a space of three or four leagues may be taken for a single village; but all the houses are upon the sea shore, and the mountains seem to occupy so much of the island, that the habitable part of it appears to be scarcely half a league broad. It is necessary to be a seaman, and reduced, as we were, in these scorching climates to a bottle of water a day, to form a just conception of the sensations we experienced. The trees which crowned the mountains, the verdure, the banana trees which were perceived around the habitations, all produced an inexpressible charm upon our senses; but the sea broke upon the coast with great fury, and we were reduced to desire, and to devour with our eyes, what it was impossible for us to attain.

The breeze had freshened, and we ran at the rate of two leagues an hour; I wished before night to explore this part of the coast as far as Morokinne, near which I flattered myself I should be able to find an anchorage sheltered from the trade winds: this plan, which was dictated by the imperious circumstances in which I was placed, did not permit me to shorten sail in order to wait for about a hundred and fifty canoes which were putting off from the shore; they were laden with fruits and hogs, which the Indians proposed to exchange for our pieces of iron.

[page] 39

Almost all the canoes came aboard of one or other of the frigates, but we were going so fast through the water that they filled alongside: the Indians were obliged to let go the ropes which we had thrown them, and leaping into the sea swam alongside after their hogs, and taking them in their arms, they took their canoes upon their shoulders, emptied them of the water, and gaily got in again, endeavouring by force of paddling to regain the situation that they had been obliged to abandon, and which had been in an instant occupied by others, who also met with the same accident. Thus we saw more than forty canoes successively overset; and although the commerce we entered into with these honest Indians was perfectly agreeable to both parties, it was impossible for us to procure more than fifteen hogs and some fruits, and we lost the opportunity of bargaining for more than three hundred others.

These canoes had outriggers: each held from three to five men; the common size might be about twenty-four feet in length, only one foot in breadth, and very near the fame in depth. We weighed one of them of these dimensions, which did not exceed fifty pounds weight. It is with these ticklish vessels that the inhabitants of these islands make runs of sixty leagues, traverse channels that are twenty leagues wide, like that between Atooi and Wohaoo, where the sea runs

D 4

[page] 40

very high; but they are such excellent swimmers, that they can scarcely be compared to any thing but seals and sea lions.

In proportion as we advanced, the mountains seemed to remove towards the interior of the island, which appeared to us in the form of a vast amphitheatre of a yellow green; we no longer perceived any cascades; the trees were much more sparingly scattered in the plain, the villages were composed only of ten or twelve cabins very remote from each other. We had every instant fresh cause to regret the country we had left behind us, and we found no shelter till we saw before us a rugged shore, where torrents of lava had formerly run, as the cascades now flow in the other part of the island.

After having steered south west by west, as far as the south-west point of the island of Mowee, I stood west and north west in order to gain the anchorage where the Astrolabe had already brought up, in twenty-three fathoms, in very hard grey sand, about a third of a league from shore. We lay sheltered from the sea breeze by a high bluff, capped by clouds. We had strong squalls from time to time, and the wind shifted every instant, so that we were constantly dragging our anchors. This roadstead was so much the worse, as we were exposed in it to currents, which prevented us from riding head to wind, except in the squalls, but they

[page] 41

made so high a sea, that it was scarcely possible for our ships boats to live. I sent one of them, however, immediately to sound around the ships; the officer reported to me, that the bottom continued the same quite to the shore; that the depth of water gradually diminished; and that there was still seven fathoms at two cables length from the shore; but when we weighed the anchor, I saw that the cable was rendered absolutely unserviceable, and that under a slight covering of sand there must have been a rocky bottom.

The Indians of the villages in this part of the island were eager to come alongside in their canoes, bringing, as articles of commerce, hogs, potatoes, bananas, roots of arum, which the Indians call tarro, with Puffs, and some other curiosities which make pars of their dress. I did not chuse to allow them to come on board till the frigate was at anchor, and the sails were furled; I told them, that I was taboo*, and this word, which I

* A word which, according to their religion, signifies a thing they cannot touch, or a consecrated place, into which they are not permitted to enter.

Reliance may be placed upon the signification of the words in the language of the Sandwich Islands from the vocabulary of captain Cook, who made a long stay in these islands, and who possessed advantages which no other navigator has had to carry on a communication with the islanders. To these motives may be added, the considence due to the known talents of Anderson, by whom he was so ably seconded.

Dixon gives a vocabulary of the language of the Sandwich islands, in which the word taboo signifies embargo; although in his Journal he explains the ceremony of lying taboo in the same manner as captain Cook.

The following table contains words of similar found, taken from the two vocabularies, which proves the errors that may be made, when to a perfect ignorance of the language is added the uncertainty of the mode of expressing the pronunciation of the words, which varies according to the individuals who pronounce them.

ENGLISH WORDS.

Correspondent WORDS from the Vocabularies

Of COOK.

Of GEO. DIXON.

Cocoa nut

Eeneeco

Neebu.

The fun

Hai, raa

Malarma.

Gourd

Aiecboo

Tibo.

W. man

Waheine

Cohabeene.

Maheine

Brother

Tooanna

Titunanie.

Cord

Heabo

Touro.

The vocabulary of Cook, although more perfect, still comes in support of my assertion; the word which signifies a woman is there found in two different places; he has repeated it without any mark of a doubt, and it is probable he has learned this signification from two individuals whose pronunciation was different, for in one place he writes Wabeine and in the other Mabeine.—(Fr. Ed.)

[page] 42

picked up from the English narratives, had all the success which I expected from it. M. de Langle,

[page] 43

who had not taken the same precaution, had in an instant the deck of his ship quite crouded with a multitude of these Indians; but they were so docile, and so fearful of giving offence, that it was extremely easy to prevail on them to return to their canoes. I had no idea of a people at once so mild and respectful. When I permitted them to come on board my ship, they did not advance a single step without our concurrence; they always evinced a fear of displeasing us; the greatest fidelity prevailed in their commerce. They took a great fancy to our pieces of old iron hoops; they were not wanting in address to procure them, by making good bargains on their own part; they would never agree to sell a quantity of stuffs, or several hogs in a lump; they very well knew, that there would be more profit arising to them by making an agreement to fix a particular price for every article.

These commercial habits, this knowledge of iron, which from their own confession they did not acquire from the English, are fresh proofs of the

[page] 44

frequent communications which these people have formerly had with the Spaniards*.

* It appears certain, that these islands were first discovered by Gaetan in 1542. This navigator sailed from the Port of the Nativity, on the western coast of Mexico, in 20° of north latitude: he stood to the westward, and after having run nine hundred leagues in this direction (without changing his latitude) he discovered a group of islands, inhabited by almost naked savages. These islands were furrounded with coral rocks: they contained cocoas, and several other fruits, but neither gold nor silver. He called them the King's Islands, probably from the day on which he made the discovery; and he named one, which he found twenty leagues to the westward, Garden Island. It was impossible for geographers, from this narrative, not to have placed the discoveries of Gaetan precisely at the same point where captain Cook has since again found the Sandwich Islands; but the Spanish editer adds, that these islands are situated between the 9th and 11th degrees of latitude, instead of saying between the 19th and 21st, as all mariners ought to conclude from the course of Gaetan.

Is this omission of ten degrees an error of the press, or does it originate from the policy of the Spanish court, which, during the last century, had so great an interest in keeping secret the situation of all the islands of this ocean?

I am led to believe that it is an error of the press, because it was very impolitie to print that Gaetan, failing from 20° of latitude, shaped his course to the westward; if they were desirous of deceiving as to the latitude, it was not very difficult to have made him steer another course.

Be this however as it may, if ten degrees be added to the latitude mentioned by Gaetan, every thing agrees; the fame distance from the coast of Mexico, the same people, the same vegetable productions, a coast in like manner surrounded with coral rocks, the same extent from north to south; the situation of the Sandwich Islands being nearly between 19 and 21 degrees, as those of Gaetan are between 9 and 11. This fresh proof, joined to those already cited, appears to me to carry this geographical discussion to absolute certainty. Besides, I can farther affirm, that there exists no group of islands between the 9th and 11th degrees, for it is the common track of the galleons from Acapulco to Manilla.

[page] 45

This nation had, during a century, very strong reasons against making these islands known, because the western seas of America were infested by pirates, who would have found provisions among these islanders, and who, on the contrary, from the difficulty of procuring them, were obliged to run westward towards the Indian seas, or to return by Cape Horn into the Atlantic Ocean. When the navigation of the Spaniards to the westward was reduced to a single galleon from Manilla, I think this extremely rich veffel was conftrained by the proprietors to follow a fixed track, which might leffen their risk. Thus by degrees this nation has perhaps lost even the remembrance of these islands, preserved upon the general chart of Cook's third voyage by lieutenant Roberts, with their ancient situation at 15° more to the eastward than the Sandwich Islands; but their identity with these last seems to me to be so clearly demonstrated, that I thought it my duty to clear them away from the surface of the sea.

[page] 46

It was so late before our sails were surled, that I was under the necessity of deserring till the next day the landing which I proposed to make upon this island, where nothing could detain me but a convenient watering place, but we already perceived, that this part of the coast was altogether destitute of running water, the declivity of the mountain having directed all the falls of rain towards the windward side. Some few days labour on the summit of the mountains might perhaps have proved sufficient to render so precious a benefit common to the whole island; but these Indians have not yet arrived at this degree of industry; in many other respects, however, they are very far advanced. The form of their government is well known by the English narratives: their extreme subordination is a striking proof, that there is an acknowledged authority, that gradually extends from the king to the lowest chief, and is based upon the people. My imagination feels great pleasure in comparing them with the Indians of Easter Island, whose industry is at least as far advanced: the monuments of the latter shew even more skill; the fabrication of their stuffs, as well as the construction of their houses, is much better, but their government is so vicious, that no one is capable of putting an end to its disorder; they do not acknowledge any authority, and although I do not think them absolutely wicked, it

[page] 47

is but too common for licentiousness to have troublesome and even fatal consequences. In making a comparison between these two nations, all the advantages seem to be in favour of those of the Sandwich Islands, though all prejudices were against them on account of the death of captain Cook. It is more natural for navigators to regret so great a man, than coolly and impartially to examine whether it were not some imprudence on his part, that obliged the inhabitants of Owhyhee to have recourse to necessary defence*.

* It is incontestibly proved, that the English commenced hostilities; this is a truth, which it would be in vain to conceal. I will not adduce any proofs of it, but such as are contained in the narrative of captain Cook's friend, of the man who looked upon him as his father, and whom the islanders believed to be his son; in short, of captain King, who tells us, after a faithful relation of the events which led to his death, "I was apprehensive of some unhappy moment, in which this confidence would prevent him from taking the necessary precautions."

The reader will also be able to judge for himself, by a comparison of the following circumstances:

Cook very inconsiderately gave orders to fire with ball, if his labourers were disturbed; though he had before him the experience of the massacre of ten men of captain Furneaux's ship's company, a maacre which was occasioned by the discharge of two firelocks upon the Zealanders, who had committed a trifling theft of some fish and bread.

Pareea, one of the chiefs, reclaiming his canoe, which had been seized upon by the ship's company, was knocked down by a violent blow of an oar, with which they struck him on he head; recovered from the stunning occasioned by it, he had the generosity to forget the violence which had been offered him; he returned a short time afterwards, brought back a hat that had been stolen, and appeared to be afraid that captain Cook himself might kill, or at least punish him.

Before the commission of any other crime than that of stealing the boat, two guns had been fired upon two great canoes, which endeavoured to make their escape.

Nevertheless, after these events, captain Cook walked to the village where the king was, and received those marks of respect, which they had always been accustomed to pay him; the inhabitants proftrated themselves before him.

There was no circumstance which could give rise to an idea of any hostile intention on the part of the islanders, when the boats placed across the bay fired again upon some canoes which endeavoured to escape, and unfortunately killed a chief of the first rank.

This death drove the islanders to madness. One of them was contented with challenging captain Cook, and threatening to throw a stone at him. Captain Cook discharged a musket at him, loaded with small shot, which, owing to the matting with which he was clothed, had no effect: this discharge of the musket became the signal of engagement. Phillips was on the point of being stabbed. Cook then fired a second musket charged with ball, and killed the foremost of the islanders. The attack immediately became more serious; the soldiers and sailors made a discharge of musketry. Four marines were already killed, and three others, with a lieutenant, were wounded, when captain Cook, finding the situation he was in, approached the water side; he called out to the boats to cease their firing, and to land, that he might embark his little troop: it was at this instant, that he was stabbed in the back, and fell upon his face into the sea.

It yet remains to be added, that Cook, having determined to bring the king and his family on board his ship, either willingly or by force, and having for that purpose penetrated into the country, was very ill prepared for such an attempt, by taking no more than a detachment of ten men.—(Fr. Ed.)

[page] 48

The night was very calm, with the exception of some gusts, which lasted less than two minutes.

[page] 49

At day-break the longboat of the Astrolabe was detached with Messrs. De Vaujuas, Boutin, and Bernizet; they had orders to sound a very deep bay which lay to the north west of us, and in which I supposed there was better anchorage than where we then were; but this new anchorage, though within our reach, was not much better than that which we occupied. According to the report of the officers, this part of the island of Mowee not affording either wood or water, and having only three very bad roads, must be very little frequented.

At eight o'clock in the morning four boats of the two frigates were ready to set off, the first two carried twenty armed soldiers, commanded by M. de Pierrevert, one of the lieutenants; M. de Langle, accompanied by all the passengers and officers who were not detained by their duty on board, were in the two others. This preparation gave no alarm to the natives, who from day-break had been alongside in their canoes; these Indians continued their traffic; they

VOL. II. E

[page] 50