[frontispiece]

[page i]

A

VOYAGE

ROUND THE WORLD,

IN THE YEARS 1785, 1786, 1787, AND 1788,

By J. F. G. DE LA PÉROUSE:

PUBLISHED CONFORMABLY TO THE DECREE OF THE

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY,

OF THE 22D OF APRIL, 1791,

AND EDITED BY

M. L. A. MILET-MUREAU,

BRIGADIER GENERAL IN THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS,

DIRECTOR OF FORTIFICATIONS, EX-CONSTITUENT,

AND MEMBER OF SEVERAL LITERARY SOCIETIES AT PARIS.

IN THREE VOLUMES

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH.

VOL. III

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, ST. PAUL'S CHURCH YARD.

1798.

[page ii]

[page iii]

CONTENTS

OF

VOL. III.

CHAPTER XXII.

| Anchorage in the bay of Avatscha.—Obliging reception given us by lieutenant Kaborof.—Arrival of Mr. Kasloff-Ougrenin, governor of Okbotsk, at the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul.—He is immediately followed by Mr. Schmaleff, and by the unfortunate Ivachkin, who inspires us with the most lively interest in his fate.—Kind attention paid us by the governor. —A ball of the Kamtschadales.—A courier from Okhotsk brings us letters from France.—We discover the tomb of M. de la Croyere, and place an inscription on copper over it, as well as over that of captain Clerke.—New views of Mr. Kasloff, in the administration of Kamtschatka.—We obtained permission to send our interpreter to France with our dispatches.—Departure from the bay of Avatscha | page 1 |

CHAPTER XXIII.

| Summary account of Kamtschatka —Marks for sailing in and out of the bay of Avatscha.—We run down the latitude 37° 30′, for a space of three hundred |

A 2

[page] iv

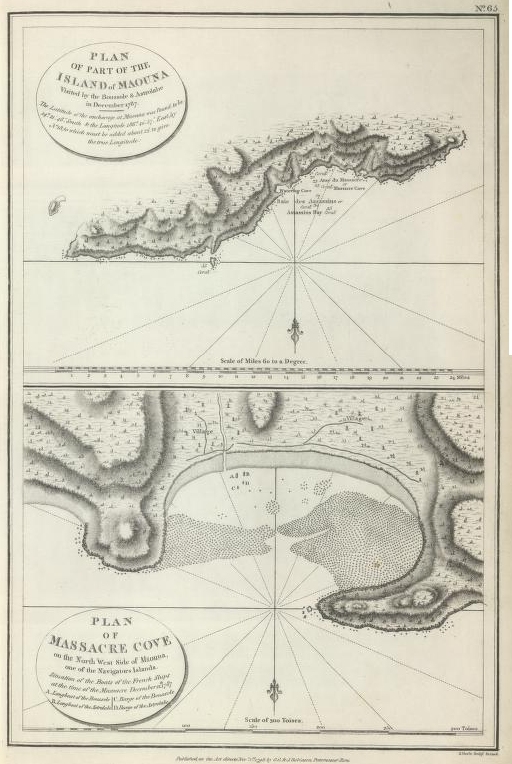

| leagues, in search of land, said to be discovered by the Spaniards in 1620.—We cross the line for the third time.—We make the island of Navigators after having passed by the island of Danger, discovered by Byron.—We are visited by a number of canoes, bartr with the Indians, and anchor at the island of Maouna. | page 37 |

CHAPTER XXIV.

| Manners, customs, arts, and usages of the islanders of Maouna.—Contrast of that beautiful and fertile country, with the ferocity of its inhabitants.—The swell becomes very heavy, and we are obliged to get under way.—M. de Langle wishing to water his ship, goes on shore with four boats manned and armed.—He and eleven persons of the two crews are murdered.—Circumstantial account of that event | page 68 |

CHAPTER XXV.

| Departure from the island of Maouna.—Description of the island of Oyolava.—Exchanges with its inhabitants.—We make the island of Pola.—New details concerning the manners, arts, and customs of these islands, and concerning the productions of their soil.—We fall in with Cocoa-nut and Traiter islands | page 102 |

[page] v

CHAPTER XXVI.

| Departure from the Islands of Navigators.—We direct our route towards the Friendly Islands.—Fall in with the island of Vavao, and several others of that archipelago very ill laid down in the charts.— The inhabitants of Tongataboo hasten on board to trade with us.—We anchor at Norfolk Island.—Description of that island.—Arrival at Botany Bay | page 128 |

SUPPLEMENTARY MEMOIRS.

| Extract of a journey to the Peak of Teneriffe, by Messieurs de Lamanon and Mongès, and the results of several chemical experiments made on the summit of the mountain; together with a description of some new varieties of volcanic Schörls | page 155 |

| Eulogy of Lamanon, by Cit. Ponce | 160 |

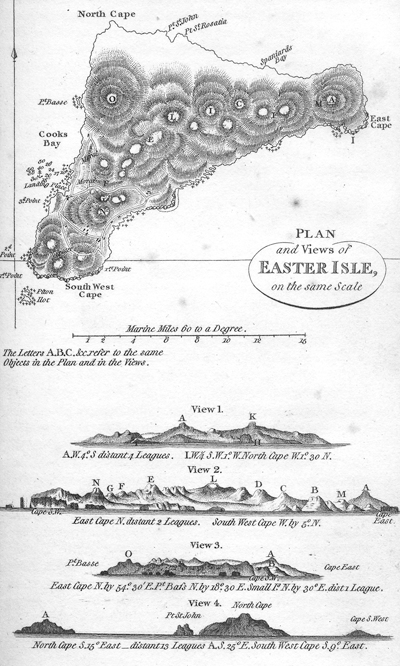

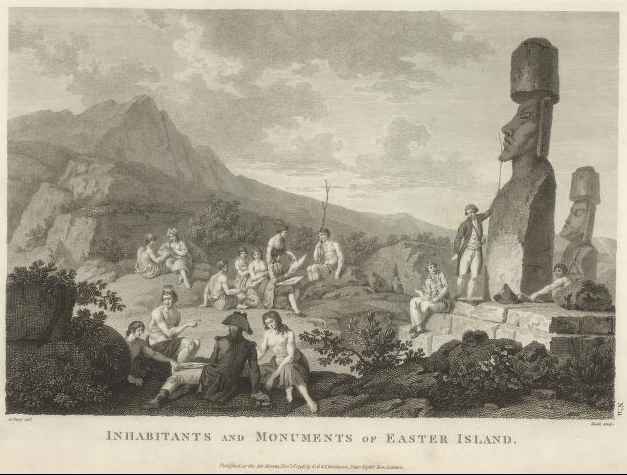

| Dissertation on the inhabitants of Easter Island and Mowie, by M. Rollin, M. D. | page 171 |

| Geographical memoir on Easter Island, by M. Bernizet, geographical engineer | page 184 |

| Physiological and pathological memoir on the Americans, by M. Rollin | page 199 |

| Of the Natives of Chili | 199 |

| Of the Natives of California | 200 |

[page] vi

| Of the Americans in the neighbourhood of Port des Français | page 202 |

| General Observations | 204 |

| Table of Comparative Proportions of the Native Americans | 222 |

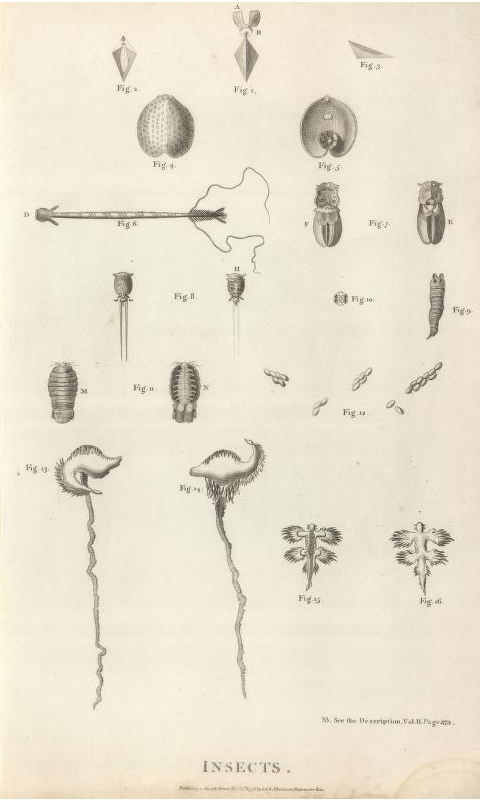

| Descriptive Memoir of certain Insects, by M. de la Martinière, Naturalist to the Expedition | page 223 |

| Dissertation on the inhabitants of the Island of Tchoka or Segalien, and on the Eastern Tartars, together with a Table of the Comparative Proportions of these People, by M. Rollin, M. D. | page 234 |

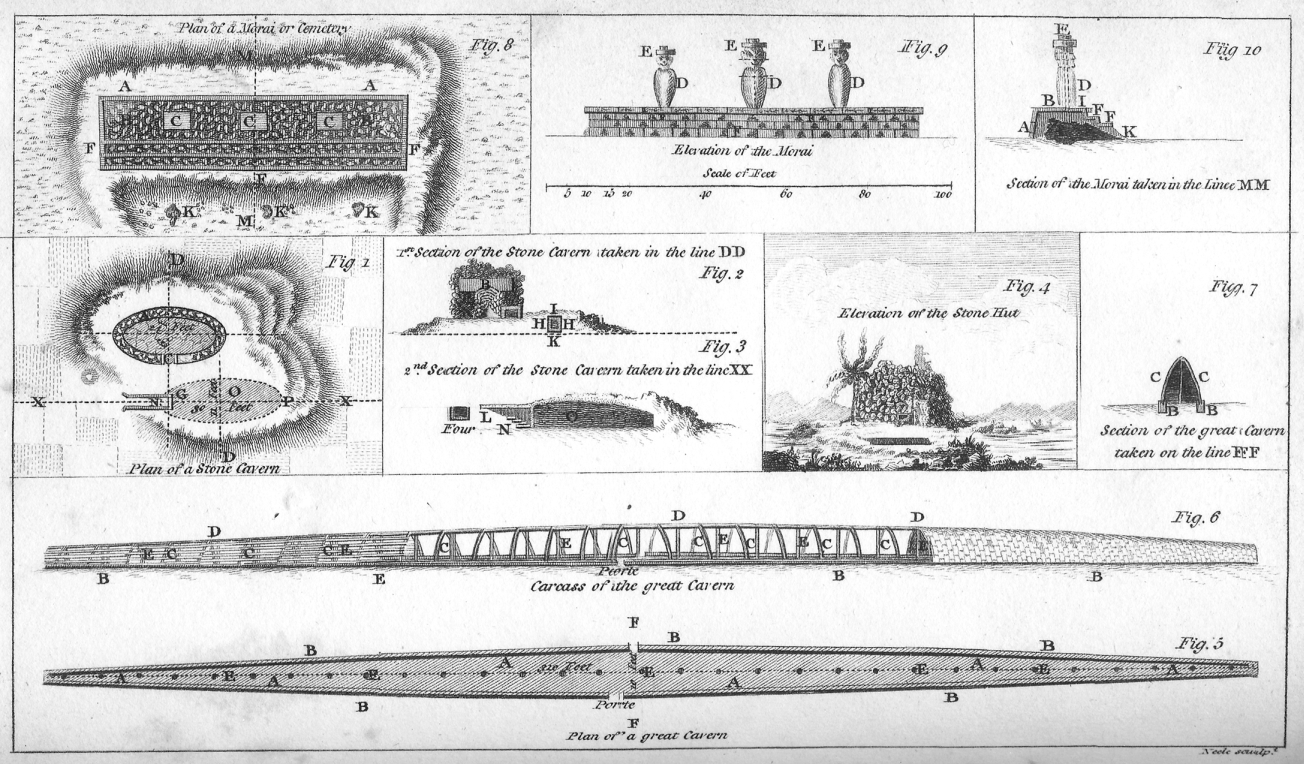

| Observations by M. de Monneron, Captain of Engineers, and Engineer in cheif to the Expedition | page 247 |

| Island of Trinidad | 247 |

| Island of St. Catherine | 251 |

| Chili | 257 |

| Easter Island, and Sandwich Islands | 263 |

| Baie des Français | 264 |

| Harbour of Monterey | 266 |

| Memoirs concerning manilla and Formosa, by M. de la Pérouse | page 268 |

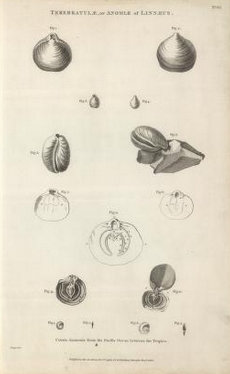

| Memoir on Terebratulæ, or Anomiæ, together with a Description of a new Species found in the Sea of East Tartary, by M. de Loamanon | page 278 |

| Description of the Shell | 282 |

| Ditto—— of the Animal | 288 |

[page] vii

| Memoir on the Cornua Ammonis, with the Description of a new Species found between the Tropics in the South Sea, by M. de Lamanon | page 298 |

| Memoir on the Fur Trade, particularly that of the Sea Otter, by M. de la Pérouse | page 304 |

| State of the Otter and Beaver Skins procured in Port des Français, on the North-West Coast of America, by the Frigates Boussole and Astrolabe | page 315 |

| Extracts from the Correspondence of Messieurs de la Pérouse, de Langle, Lamanon, &c. with the Minister of the Marine | page 318 |

| Extracts of Letters from Messieurs de la Pérouse and Dagelet to M. Fleurieu | page 380 |

| Extracts of Letters written by M. de la Pérouse, to M. de la Touche, Adjutant Director of the Ports and Post Captain; and by M. de Lamanon to M. de Serviéres | page 416 |

| Letter from M. de la Martiniére to the Minister of Marine | page 422 |

| Extract of a Letter from M. de Lamanon to M. Condorcet | page 428 |

| Memoir and Table of Observations made for the Purpose of discovering the Flux and Reflux of the Atmosphere, by M. de Lamanon | page 434 |

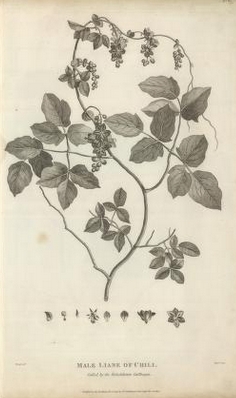

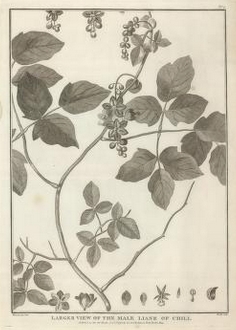

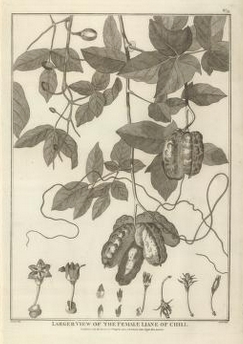

| Descriptive Note on the Lianes of Chili, by Ventenat, Member of the National Institute | page 413 |

[page] viii

NAUTICAL TABLES

| Tables, shewing the Course of la Boussole, during the years 1785, 1786, 1787, 1788, from the time of the ship's sailing from Europe till its arrival in Botany Bay | page 1 |

| Tables, shewing the Course of l'Astrolabe, during the years 1785, 1786, 1787, from the time of the ship's sailing from Europe till its arrival in Kamtschatka | page 33 |

| Table of Longitudes, from the 11th of April to the 7th of September, 1787, by M. Dagelet | page 57 |

ERRATA

| Page 11, | line 20, insert insert after determination. |

| —— 45, | — 26, for read Kaborof. |

| —— 134, | — 47, for read Cook. |

| —— 155, | — 1, for Journal read Journey. |

| —— 159, | — 16, 17, for plans read planes. |

| —— 171, | — dele Chapter XXVII. |

| —— 329, | — ult. for rivality read rivalry. |

| —— 340, | — penult. for smaller read less. |

[page 1]

VOYAGE

ROUND THE WORLD,

IN THE YEARS

1785, 1786, 1787, AND 1788.

CHAPTER XXII

Anchorage in the bay of Avatscha.—Obliging reception given us by lieutenant Kaborof.—Arrival of Mr. Kasloff-Ougrenin, governor of Okhotsk, at the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul.—He is immediately followed by Mr. Schmaleff, and by the unfortunate Ivachkin, who inspires us with the most lively interest in his fate.—Kind attention paid us by the governor.—A ball of the Kamtschadales.—A courier from Okhotsk brings us letters from France.—We discover the tomb of M. de la Croyere, and place an inscription on copper over it, as well as over that of captain Clerke.—New views of Mr. Kasloff, in the administration of Kamtschatka.—We obtained permission to send our interpreter to France with our dispatches.—Departure from the bay of Avatscha.

(SEPTEMBER 1787.)

WE had not yet moored before the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul, when a visit was paid us by the toyon, or cheif, of the village, and several other

VOL. III.B

[page] 2

inhabitants. All of them brought us presents of salmon, or skate, and offered us their services in hunting bears, or in shooting the ducks, with which the ponds and rivers are covered. We accepted their offers; lent them muskets; gave them powder and shot; and found no want of wild-fowl during our whole stay in the bay of Avatscha. They required no money as a reward for their fatigue; but we had been so amply provided at Brest with articles of the greatest value to Kamtschadales, that we insisted upon their accepting tokens of our gratitude, which our opulence enabled us to proportion rather to their wants than to the worth of their game. The government of Kamtschatka had been entirely changed since the departure of the English. It was now only a dependency of that of Okhotsk; and the different posts of the peninsula were commanded by different officers, who were accountable for their conduct to the commandant-general of that province alone. Captain Schmaleff, the same person who succeeded major Behm pro tempore, was still in the country, with the title of commandant of the Kamtschadales. Mr. Reinikin, his real successor, who arrived at Kamtschatka a short time after the departure of the English, had remained there only four years, and had returned to Petersburg in 1784. These particulars were communicated to us by lieutenant Kaborof, who was governor of the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul, with a serjeant and a detachment of forty soldiers

8

[page] 3

or cossacks under his command. The kind attentions of this officer were boundless: his personal exertions, those of his soldiers, every thing, in short, that he possessed was at our service. He would not even permit me to send off one of my own officers to Bolcheretsk, where Mr. Kasloff-Ougrenin, the governor of Okhotsk, who was making a tour through his province, happened most fortunately to be. He told me, that the governor was expected to arrive in a few days at St. Peter and St. Paul's, and that he was probably already on the road. He added, that the journey was more tedious than we. might suppose, because the time of the year not permitting the use of a sledge, it was necessary to travel half the way on foot, and the other half in a canoe upon the rivers of Avatscha and Bolcheretsk. Mr. Kaberof at the same time proposed to send off a cossack with my dispatches to Mr. Kasloff, of whom he spoke with an enthusiasm and satisfaction in which it was hardly possible not to participate. He congratulated himself every moment upon the opportunities we should have of conversing, and communicating with an officer, whole education, manners, and knowledge, were not inferior to those of any officer of the Russian empire, or indeed of any nation whatever. M. de Lesseps, our young interpreter, who spoke the Russian language as fluently as French, translated the kind expressions of the lieutenant; and wrote a Russian letter in my name to the governor of Okhotsk, to whom I

B2

[page] 4

also wrote in French myself. I told him, that the narrative of Cook's last voyage had spread the fame of the hospitality of the Kamtschadale government; and that I flattered myfelf I should meet with a reception similar to that of the English navigators, since our voyage, like theirs, was meant to conduce to the common advantage of all maritime nations. As Mr. Kasloff's answer could not reach us in less than five or six days, the worthy lieutenant told us, that he only anticipated his orders, and those of the empress of Russia, by begging us in the mean time to consider ourselves as in our native land, and to dispose freely of every thing the country afforded. It was easy to perceive by his gestures, his looks, and his expressions, that if it had been in his power to perform a miracle, the mountains and morasses of Kamtschatka would have been transformed for our gratification into an elysium. A report was circulated, that Mr. Kasloff had no letters for us, but that Mr. Steinheil, the former governor, whom Mr. Schmaleff succeeded as captain-ispravnik, or inspector of the Kamtschadales, and who resided at Verkhnei-Kamtschatka, possibly had; and instantly upon this vague conjecture, which hadscarcely asemblance of truth, he sent off an express, who had more than 150 leagues to travel on foot. Mr. Kaborof knew how extremely desirous we were of receiving letters from France. He had learned from M. de Lesseps how great our disappointment had been on finding that no packets addressed to us

[page] 5

had arrived at St. Peter and St. Paul's. He appeared almost as much afflicted as ourselves; and by his solicitude and cares seemed to say, that he would go to Europe himself in search of our letters, if there were any hope of his finding us on his return. The serjeant and all the soldiers manifested an equal desire to oblige, and Mrs. Kaborof, on her part shewed us every possible attention: her house was open to us at all hours of the day, and tea and the other refreshments of the country were prepared there for our use. Every one wished to make us presents, and, inspite of our determination not to receive any, it was impossible to withstand the pressing solicitations of the lieutenant's lady, who forced our officers, M. de Langle, and myself, to accept a few skins of sables, rein-deer, and foxes, far more useful, without doubt, to those who parted with, them, than to us who were about to return towards the tropics. Fortunately we had the means of acquitting ourselves of the obligation; and we insisted on being permitted in our turn to offer such things as were not be found at Kamtschatka. But though richer than our hosts, our artificial manners did not permit us to vie with them in that simple and affecting expression of kindness, which stamps a value on the meanest gift.

Through the medium of M. de Lesseps I signified to Mr. Kaborof, that I was desirous of forming a little establishment on shore, for the purpose of lodging our astronomers, and depositing a qua-

B 3

[page] 6

drant and a pendulum. Immediately the most commodious house in the village was offered us; and as we repaired thither but a very few hours after the request was made, we thought we might venture to accept it without indelicacy, because to us it appeared uninhabited. But we learned afterwards, that the lieutenant, to make room for us, had turned out the corporal, who was at the same time his secretary, and the third person in the country. Such is the Russian discipline, that its movements are executed with as much promptitude as the manual exercise, no order being necessary but a nod of the head.

Our astronomers had scarcely erected their observatory, when our naturalists, whose zeal was not inferior to theirs, determined to visit the volcano, in appearance not more than two leagues distant, though in fact it was at least eight to the foot of the mountain, which was almost entirely covered with snow, and at the summit of which the crater was situated. The mouth of this crater, turned towards the bay of Avatscha, presented constantly to our eyes thick clouds of smoke; and once during the night we perceived faint blue and yellow flames; but they rose to a very jnconsiderable height.

The zeal of Mr. Kaborof was as much excited in favour of our naturalists, as of our astronomers; and immediately eight Cossacks were ordered to accompany Messieurs Bernizet, Monges, and Receveur. The health of M. Lamanon was not sufficiently re-

[page] 7

established to permit him to engage in the expedition. Never perhaps was one so laborious undertaken for the advancement of the sciences. Not one of the learned English, Germans, or Russians, who had travelled in Kamtschatka had ever ventured upon so difficult an enterprise. From the aspect of the mountain I judged it to be entirely inaccessible. There was no appearance of verdure—it was nothing but a rock, of which the acclivity was terribly steep. Our intrepid travellers set off in hopes of overcoming these obstacles. The Cossacks were loaded with their baggage, which consisted of one tent, a number of skins, and the provision that each person had laid in for four days. The honour of carrying the barometers, the thermometers, the acids, and the other articles necessary for observation, was retained by the naturalists, who could not trust such frail instruments to any other hands; besides, their guides were only to conduct them to the bottom of the peak, a prejudice, as ancient perhaps as Kamtschatka; making both Kamtschadales and Russians believe, that the mountain emits a vapour, which must infallibly suffocate all who are rash enough to ascend it. They flattered themselves no doubt, that our natural philosophers would, like themselves, stop at the foot of the volcano, having probably been inspired with a tender concern for their fate by a few glasses of brandy given them previous to their departure. With this hope they set off in high spirits, and made their first halt in

B 4

[page] 8

the middle of the woods, at six leagues distance from the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul. The ground they had as yet gone over opposed little obstacle to their passage, though covered with shrubs and trees, the greater number of the latter being of the birch species. The pines that were there were stunted, and little better than dwarfs. One species of them bears cones, of which the seeds or nuts are good to eat; while a very wholesome and agreeable beverage flows from the bark of the birch. This liquor the Kamtschadales take care to collect, and drink very freely. Berries of every kind, and of every shade of red and black, also offered themselves to the travellers at every step. Their taste is in general somewhat acid; but they are rendered highly palateable by the admixture of sugar.

At sunset the tent was pitched, the fire lighted, and every thing prepared for passing the night, with a promptitude unknown to people accustomed to reside in cities. The greatest care was taken to prevent the fire from spreading to the trees of the forest. The application of the stick to the backs of the Cossacks would not have sufficed to expiate so serious a fault, because the flames never fail to put the sables to flight. After such an accident no more are to be found during the winter, which is the hunting season; and as the skin of these animals, the only riches of the country, is given in exchange for all the commodities the inhabitants stand in need of, and serves to pay the annual

[page] 9

tribute due to the crown, it is easy to conceive the enormity of a crime that deprives the Kamtschadales of advantages so important. The Cossacks accordingly were at great pains to cut down the grass round the fire place, and before their departure, to dig a deep hole to receive the ashes, which they extinguished by covering them with earth well moistened with water. During this day's journey they saw no quadruped but a hare, which was almost white: neither bear, argali*, nor reindeer, made its appearance, although these animals are very common in the country. The next morning they rose at break of day, and continued their journey. It had snowed hard during the night, and, what was still worse, a thick fog covered the volcanic mountain, the foot of which our natural philosophers did not reach till three o'clock in the afternoon. Their guides, according to agreement, stopped as soon as they reached the limits of the vegetative earth, pitched their tents, and lighted a fire. That night's rest was a necessary preparative to the fatigues of the next day.

* This animal is the mountain-sheep, or Capra Ammon of the Linnean system. It is supposed to exist in no part of Europe but Corsica and Sardinia, and to be the same of which a living specimen existed a few years ago in the Prince of Conde's collection at Chantille. It was there called Mouffoli, and was considered by M. Bufson as the parent stock whence all the varieties of domestic sheep are sprung. T.

[page] 10

At six o'clock in the morning Messieurs Bernizet, Mongés, and Receveur, began to ascend the steep, and did not stop till three in the afternoon, when they reached the very edge of the crater, but at the lowermost part. They had been often obliged to have recourse to their hands in order to support themselves among the broken rocks, the intervals between them being sometimes very dangerous precipices. All the substances of which the mountain is composed are lavas more or less porous, and almost in the state of pumice-stone. At the summit they met with gypseous stones, and crystallized sulphur; but the latter was much less beautiful than that of the peak of Teneriffe. In general, indeed, the schorls, and all the other stones they found there, were much inferior in beauty to those of that ancient volcano, which has not been in a state of eruption for a century past, whereas the Kamtschadalian mountain threw up stones and ashes in 1778, during captain Clerke's stay in the bay of Avatscha. They brought back with them, however, some tolerable specimens of chrysolite; but they encountered such bad weather, and passed over so rough a road, that their being able to add a new weight to that of the barometers, thermometers, and other instruments, is truly astonishing. Their horizon never extended beyond a musketshot, except for a few minutes only, when they perceived the bay of Avatscha, and the frigates, which

[page] 11

from that elevation appeared no bigger than small canoes. Their barometer upon the edge of the crater fell to nineteen inches, eleven lines, and 2/10, while ours on board the frigates, where we were making hourly observations, pointed at the very same time to twenty-seven inches nine lines 2/10. Their thermometer was two degrees and a half below the freezing point, and differed no less than twelve degrees from the temperature at the waterside. Thus, admitting the calculations of the natural philosophers, who believe in this mode of measuring elevations, and making the requisite corrections by the thermometer, the travellers must have ascended about fifteen hundred toises, a prodigious height, considering the difficulties they had to surmount. But their views were so frustrated by fogs, that they resolved to go over the same ground again the following day, if the weather should be more favourable, difficulties having only increased their ardour; and with this courageous determination descended the mountain, and repaired to their tents. The night being already come on, their guides had said prayers for their souls, and swallowed a part of the liquor, for which they supposed that dead men could no longer have occasion. The lieutenant, when informed on their return of this hasty proceeding, ordered the most culpable to be punished with a hundred stripes, which were duly administered before we knew any thing of the matter, and con-

[page] 12

sequently before it was possible for us to solicit their pardon. The night, after this journey to the mountain's top, was dreadful: the fall of snow redoubled, and in a few hours covered the earth several feet deep. This forced them to give up all idea of executing the plan of the preceding afternoon, and that very evening they arrived at the village of St. Peter and St. Paul, after a march of eight leagues, which the natural declivity of the ground rendered less fatiguing than they had found it before.

While our mineralogists and astronomers were making such good use of their time, we filled our cacks with water, and our hold with wood, and cut and dried hay for the live stock we expected; for we had now only one sheep left. The lieutenant had written to Mr. Kasloff, begging him to collect as many oxen as he could: he calculated with sorrow, that it was impossible for us to wait for those that were no doubt coming from Verknei by order of the governor, as it would require at least six weeks for their conveyance. The indifference of the inhabitants of Kamtschatka in regard to cattle has prevented their multiplying in the southern part of that peninsula, where, with a little care, they might soon be as abundant as in Ireland. The finest and thickest grass grows in natural meadows to the height of more than four feet; and an immense quantity of hay might be made for the winter, which in that climate lasts between seven

[page] 13

and eight months. But the Kamtschadales are incapable of such cares: it would be necessary to have barns, and vast stables sheltered from the cold; while to them it appears far more commodious to live upon the produce of their hunting and fishing, particularly upon the salmon, which comes every year at the appointed time, like the manna of the desert, to fill their nets, and insures them a plentiful subsistence till the return of the season. The Cossacks, and the Russians, who are better soldiers than farmers, have adopted the same method.

The lieutenant and the serjeant alone had little gardens for the cultivation of potatoes and turnips; but neither their exhortation, nor their example, had any influence over their countrymen, who ate potatoes with an excellent relish, but who, to procure them, would not have consented to take any farther trouble than that of pulling them up, in case nature had offered them spontaneously, like saranne*, garlick, and especially the berries, of which they make agreeable drinks, and sweetmeats that they reserve for the winter season. Our European seeds having kept very well, we gave a great quantity of them to Mr. Schmaleff, to the lieutenant, and to the serjeant; and hope on some future day to hear that they have retained their vegetative power. In the midst

* A species of lily peculiar to Siberia and Kamtschatka. T.

[page] 14

of our labours we found time for pleasure; and made several hunting parties on the rivers Avatscha and Paratounka, being very desirous of getting a shot at the bears, rein-deer, or argali. We were obliged, however, to be contented with a few ducks, or rather teal, a paltry sort of game, which ill repaid our long and fatiguing excursions. We were more fortunate through the medium of our friends the Kamtschadales, who brought us, during our stay, four bears, an elk, and a rein-deer, with such a quantity of divers, and other wild fowl, that we distributed them among our crews, who began already to be tired of fish. A single cast of the net almost close along side of our frigates would have sufficed for the subsistence of half a dozen ships; but there was little variety of species, the fish taken being seldom any thing but small cod, herrings, plaice, and salmon. I gave orders to salt only a few barrels, because it was represented to me, that fish so small and tender could not resist the corrosive activity of the salt; and that it was better to preserve our stock of that article for the hogs we should find in the islands of the South sea. While we were passing our time in a manner which appeared very pleasant after the fatigues we had recently undergone in exploring the coasts of Oku. Jesso and Tartary, Mr. Kasloff had set off for the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul; but he travelled slowly, because he wished to examine every thing, the object of his.

[page] 15

journey being to establish the best possible order in the administration of the province. He knew that a general plan could not be formed for that purpose till he had first inquired what the country produced, and what it might be made to produce by a mode of cultivation suitable to the climate. He wished also to make himself acquainted with the stones, minerals, and in general with all the substances that compose the soil. His observations detained him a few days at the hot springs at twenty leagues distance from St. Peter and St. Paul, whence he brought several stones, and other volcanic matters, with a species of gum, which was analyzed by Mr. Monges. On his arrival, M. Kasloff told us with great civility, that having learned by the public papers, that several able naturalists had embarked on board our frigates, he had been desirous of availing himself of so fortunate a circumstance, in order to learn the nature of the minerals of the peninsula, and thus to become a naturalist himself The politeness of Mr. Kasloff, and indeed the whole of his behaviour, was exactly the same as that of the best educated inhabitants of the largest cities in Europe. He spoke French; and was well informed concerning all the objects of our research, as well in geography as in natural philosophy. It is easy to conceive, that an intimate acquaintance between him and us was speedily formed. The day after his arrival he

[page] 16

came to dine with me on board the Boussole, in company with Mr. Schmaleff, and the vicar of Paratounka. I ordered him to be saluted with thirteen guns. Our faces, which bespoke better health even than that which we enjoyed at our departure from Europe, surprising him exceedingly, I told him, that we owed a little of it to our own care, and a great deal to the good living we had met with in his government. Mr. Kasloff seemed to participate in our comfortable situation; but he expressed the greatest concern at his inability to get together more than seven oxen before the time of our departure, which was too near at hand to admit of their being brought from the river of Kamtschatka, a hundred leagues distant from St. Peter and St. Paul. For six months he had been in expectation of the vessel that was to bring from Okhotsk the meal and other provision necessary for the garrisons in Kamtschatka, and began to feel some anxiety for her fate. Our surprise at not receiving any letters was much lessened when he told us, that since his departure from Okhotsk he had not received a single express. He added, that he was going to return by land, along the shores of the sea of Okhotsk, a journey almost as long, and certainly attended with more difficulties than that from Okhotsk to Petersburg.

The next day the governor, with all his suite, dined on board the Astrolabe, where he was also

[page] 17

saluted with a discharge of thirteen guns; but he earnestly requested, that this compliment might be paid him no more, that in future we might fee one another with more ease and comfort.

It was perfectly impossible to make him accept the value of the oxen. In vain did we represent, that we had paid the whole of our expences at Manilla, notwithstanding the strict alliance between France and Spain. Mr. Kasloff told us, that the principles of the Russian government were different, and that his only regret was the having so little cattle at his disposal. He invited us to a ball which he was to give the following day, on our account, to all the women, both Kamtschadales and Russians, of St. Peter and St. Paul's. If the assembly were not numerous, it was at least extraordinary. Thirteen women, dressed in silken stuffs, ten of the number being Kamtschadales, with broad faces, little eyes, and flat noses, were sitting on benches round the room. The Kamtschadales as well as the Russians had silk handkerchiefs tied round their heads, almost in the manner they are worn by the mulatto women in our West India islands. The ball began with Russian dances, of which the tunes were very pleasing, and very much like the country dance called the Cossack, that was in fashion at Paris a few years ago. The Kamtschadale dances that followed can only be compared to those of the con-

VOL. III. C

[page] 18

vulsionnaires, at the famous tomb of St. Medard*, the dancers having occasion for nothing but arms and shoulders, and scarcely for any legs at all. The Kamtschadale females, by their convulsions, and contracted motions, inspire the spectator with a painful sensation, which is still more strongly excited by the mournful cry that is drawn from the pit of their stomachs, and that serves as the only music to direct their movements. Their fatigue is such during this exercise, that they are covered with perspiration, and lie stretched out upon the floor, without the power of rising. The abundant exhalations that emanate from their bodies persume the whole apartment with a smell of oil and fish, to which European noses are too little accustomed to find out its fragrance. As the dances of all these nations have ever been imitative, and in fact nothing but a fort of pantomime, I asked what two of the women, who had just taken such violent exercise, had meant to express. 1 was told that they had represented a bear-hunt. The woman who rolled on the ground acted the animal; and the other, who kept turning round her, the hunter; but if the bears could speak, and were to see such a pantomime, they would certainly complain of being so awkwardly imitated. This dance, almost as fa-

* The tomb of a pious abbé at Paris, where lame people were cured by being thrown into convulsions. T.

[page] 19

tiguing to the spectator as to the performer, was scarcely over, when a joyful exclamation announced, the arrival of a courier from Okhotsk. He was the bearer of a large trunk filled with our packets. The ball was interrupted, and each of the females dismissed with a glass of brandy, a refreshment worthy of such votaries of Terpsichore. Mr. Kasloff, perceiving our impatience to learn the news of all that was interesting to us in Europe, entreated us not to defer the pleasure; conducted us to his own room; and retired, that he might not restrain the effusion of the different sentiments by which we might be affected, according to the news received by each from his family or friends. It was favourable to all, particularly to me, who, by a degree of favour to which I dared not to aspire, had been promoted to the rank of commodore. The compliments every one was eager to make me soon reached Mr. Kasloff, who was pleased to celebrate the event by a discharge of all the artillery of the place. To the last day of my life, I shall remember, with the strongest emotions of gratitude, the marks of friendship and affection which I received from him upon this occasion. I did not indeed pass a moment with him that was not marked by some trait of kindness or attention. It is needless to say, that as since his arrival all the inhabitants of the country were hunting and fishing for us, we were unable to consume the quantity

C 2

[page] 20

of provision furnished us. To this he added presents for M. de Langle and myself. We were forced to accept a Kamtschadalian sled for the king's cabinet of curiosities, and two royal eagles for the menagerie, as well as a great number of sable-skins. We offered him, in our turn, every thing that we thought useful or agreeable to him; but as we were only rich in commodities for the savage market, we had nothing worthy of such a benefactor: we begged him, however, to accept the narrative of Cooke's third voyage, with which he was much pleased, especially as he had in his suite almost all the personages whom the editor has brought forward upon the stage—Mr. Schmaloff the good vicar of Paratounka, and the unfortunate Ivaschkin. To them he translated all the passages that concerned them, and at the rehearsal of each they repeated that every word was strictly true. The serjeant alone, who then commanded at the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul, was dead. The others enjoyed the best state of health, and still inhabited the country, except major Behm, who had returned to Petersburg, and Port, who resided at Irkoutsk. I testified my surprise to Mr. Kasloff at finding the aged Ivaschkin in Kamtschatka, the English accounts stating, that he had at length obtained permission to go and live at Okhotsk.

We could not help feeling great concern for the fate of this unfortunate man, when told that his

5

[page] 21

only crime was some indiscreet expressions concerning the empress Elizabeth, at the breaking up of a convivial party, when his reason was disordered by wine. He was then under twenty, was an officer in the guards, belonged to a Russian family of distinction, and could boast of a handsome face, which neither time nor misfortune have been able to alter. He was cashiered, and banished to the interior of Kamtschatka, after having suffered the punishment of the knout, and had his nostrils slit. The empress Catherine, whose attentions are carried as far as the victims of preceding reigns, granted this unfortunate man a pardon several years ago: but a stay of more than fifty years in the midst of the vast forests of Kamtschatka; the bitter recollection of the ignominious punishment he suffered; perhaps, also, a secret sentiment of hatred against an authority which punished so cruelly a fault, that was rendered excusable by circumstances; these various motives rendered him insensible to a tardy act of justice; and he purposed ending his days in Siberia. We begged him to accept some tobacco, powder, shot, cloth, and every thing, in short, which we supposed useful to him. He had been educated at Paris, still understood a little French, and recollected a number of words expressive of his gratitude. He loved Mr. Kasloff like a father, and accompanied him in his journey out of affection; while the good governor treated him with an attention well

C 3

[page] 22

calculated to make him forget his misfortunes*. He did us the favour of pointing out the grave of M. de la Croyère, whom he had seen buried at Kamtschatka in 1741. We placed over it the following inscription, engraved on copper, and composed by M. Dagelet, a member, like himself, of the Academy of Sciences:

Here lies Louis de I'Isle de la Croyère, of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, who died in 1741, on his return from an expedition undertaken by command of the Czar, in order to explore the coast of America: as an astronomer and geographer, he was emulous of two brothers celebrated in the sciences, and was deserving of the regret of his country. In 1786, the Count

* The remembrance and the shame of an unjust punishment so pursued the unfortunate Ivaschkin, that he determined to hide himself from the eyes of strangers; and it was not till a week after the arrival of the frigates, that Lesseps found means to discover him. The interpreter, affected by his situation, gave an account of it to La Perouse, who, admiring the noble disposition of the old man, and pitying his misfortune, requested to see him. It was with difficulty, and by means of Mr Kasloff's influence over his mind, that he was prevailed on to quit his retreat. The amenity of manners of La Pérouse soon inspired Ivaschin with the greatest confidence, and the unfortunate man, who was ever mindful of the civilities he received, testified his gratitude still more strongly, when the French general made him a number of useful presents, of which he was in the greatest: want.

This anecdote, which Lesseps has related to me several times is not out of its place here.—(Fr. Edit)

[page] 23

de la Pérouse, commanding the king's frigates, the Boussole and Astrolabe, did honour to his memory by giving his name to an island near the places visited by himself.

We also asked Mr. Kasloff's permission to engrave upon a plate of the same metal the inscription over the grave of captain Clerke, which was only written with a pencil upon wood, a matter too perishable to perpetuate the memory of so estimable a navigator. The governor had the goodness to add to the permission which he gave us a promise to erect without delay a monument more worthy of those two celebrated men, who paid the debt of nature in the midst of their arduous undertakings, at so great a distance from their native land. He told us, that M. de la Croyère had. married at Tobolsk, and that his poerity enjoyed a great deal of consideration at that place. The history of the voyages of Behring, and captain Tschirikow, were familiar to Mr. Kasloff, who thence took occasion to tell us, that he had left Mr. Billings at Oknotsk, charged by the state to build two vessels for the purpose of continuing the Russian discoveries in the Northern seas. He had given orders, that all the means at his disposal should be employed to accelerate the expedition; but his zeal, his best endeavours, his earnest desire, to fulfil the wishes of the empress, did not suffice to overcome the obstacles, which necessarily presented

C 4

[page] 24

themselves in a country almost as savage as on the first day of its discovery, and where labour is suspended by the rigour of the climate for more than eight months in the year. He was of opinion, that it would have more economical, and far more expeditious, to let Mr. Billings take his departure from some port in the Baltic, where he might have provided for all his wants for several years to come.

We took a plan of bay of Avatscha, or, more correctly speaking, we verified that of the English, which is exceedingly correct; and M. Bernizet made a very elegant drawing of it, which he begged him a view of the Ostrog; and the abbes Monges and Receveur made him a present of a small box of acids for the analysis mineral waters, and the ascertainment of the different substances of which the soil of Kamtschatka is composed. Mr. Kasloff was no stranger to the sciences of chemistry and mineralogy: he had indeed a particular taste for chemical experiments; but he convinced us, by reasons of which force is easily felt, that previously to attending to the minerals of an uncultivated country, it was the part of a wife and enlightened administration to endeavour to procure the inhabitants bread, by accustoming them to agricultural labours. The rabidity of vegetation bespoke great fertility of soil, and he did not doubt, that it would produce abun-

[page] 25

dant crops of rye or barley, in case of the Failure of wheat, which might be prevented from shooting by the severity of the winter. He made us remark the promising appearance of several small fields of potatoes, of which the seed had been brought from Irkoutsk a few years before; and purposed to adopt mild, though infallible means, of making farmers of the Russians, Cossacks, and Kamtschadales. The sinall-pox in 1769 swept away three fourths of the individuals of the latter nation, which is now reduced to less than four thousand persons, scattered over the whole of the peninsula; and which will speedily disappear altogether, by means of the continual mixture of the Russians and Kamtschadales, who frequently intermarry. A mongrel race, more laborious than the Russians, who are only fit for soldiers, and much stronger, and of a form less disgraceful to the hand of nature, than the Kamtschadales, will spring from these marriages, and succeed the ancient inhabitants. The natives have already abandoned the yourts, in which they used to burrow like badgers during the whole of the winter, and where they breathed an air so foul as to occasion a number of disorders. The most opulent among them now build isbas, or wooden houses, in the manner of the Russians. They are precisely of the same form as the cottages of our peasants; are divided into three little rooms; and are warmed by a

[page] 26

brick stove, that keeps up a degree of heat* insupportable to persons unaccustomed to it. The rest pass the winter as well as the summer in balagans, which are a kind of wooden pigeon-houses, covered with thatch, and placed upon the top of posts twelve or thirteen feet high, to which the women as well as the men climb by means of ladders that afford a footing very insecure. But these latter buildings will soon disappear; for the Kamtschadales are of an imitative genius, and adopt almost all the customs their hair, and are almost entirely dressed, in the manner of the Russians, whose language prevails in all the ostrogs; a fortunate circumstance, since each Kamtschadalian village spoke a different jargon, the inhabitants of one hamlet not understanding that of the next. It may be said in praise of the Russians, that though have established a despotic government in this rude climate, it is tempered by a mildness and equity, that render its inconveniencies unfelt. They have no reproaches of atrocity to make themselves, like the English in Bengal, and the Spaniards in Mexico and Peru. The taxes they on the Kamtschadales are so light, that they can only be considered as a mark of gratitude towards the sovereign, the produce of half a day's hunting acquitting

* Not less than thirty degrees of Reaumur's thermometer.

[page] 27

the imposts of a year It is surprising to see in cottages, to all appearance more miserable than those of the most wretched hamlets in our mountainous provinces, a quantity of species in circulation, which appears the more considerable, because it exists among so small a number of inhabitants. They consume to few commodities of Russia and China, that the balance of trade is entirely in their favour, and that it is absolutely necessary to pay them the difference in rubles. Furs at Kamtschatka are at a much higher price than at Canton, which proves, that as yet the market of Kiatcha has not felt die advantageous effect of the new channel opened in China. The Chinese merchants are, no doubt, careful, to let these furs run off in an imperceptible stream, and thus to make enormous gains; for at Macao they bought of us for ten piastres what was worth a hundred and twenty at Pekin. An otter skin is worth at St. Peter and St. Paul's thirty rubles; a sable three or four: the price of fox skins cannot be fixed, I do not mean black foxes, which are too scarce to become the subject of calculation, and which are sold for more than a hundred rubles apiece. The white and grey vary from two to twenty rubles according as they approach to black or red, which last only differ from those of France by the softness and thickness of their fur.

The English, who, by the happy constitution of their company, have it in their power to leave to

[page] 28

the private trade of India all the activity of which it is susceptible, sent a small vessel last year to Kamtschatka. It was fitted out by a commercial house of Bengal, and commanded by captain Peters, who sent colonel Kasloff a letter in French, which he gave me to read. The English captain, upon the plea of the strict alliance which unites the two courts in Europe, requested permission to trade with Kamtschatka, by bringing thither the different commodities of India and China, such as stuffs, sugar, tea, and arrack, and taking the furs of the country in return. Mr. Kasloff was too enlightened a man not to perceive that such a proposition was ruinous to the commerce of Russia, which sold the same articles to the Kamtschadales at a great profit, and made a still greater upon the skins which the English wished to export; but he knew also, that certain limited permissions had sometimes been given to the detriment of the empire at large, for the increase of a colony, which afterwards enriches the mother country, when it has risen to such a pitch as to have no farther occasion for foreign commerce. These considerations prevented Mr. Kasloff from deciding the question; and he permitted the English to transmit their proposition to the court of Petersburg. He was sensible however, that, even if their request were granted, the country consumed too little of the commodities of India and China, and found too good a market for its furs at Kiatcha, for the Bengal

[page] 29

merchants to find it a profitable speculation. Besides, the very vessel that brought these commercial overtures was wrecked on Copper Island, a few days after going out of the bay of Avatscha, and only two men saved, to whom I spoke, and furnished some articles of clothing, of which they stood in great need. Thus captain Cook's ships and our own are the only ones which have yet made a fortunate voyage to this part of Asia.

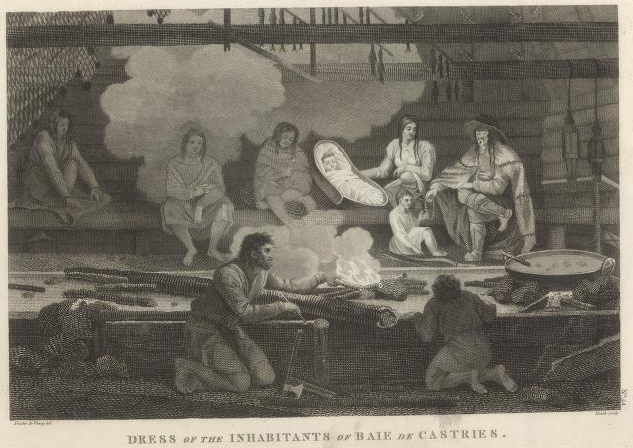

It would be incumbent on me to give the reader a more particular account of Kamtschatka, if the works of Coxe and Steller did not afford ample satisfaction*. The editor of captain Cook's third voyage has had recourse to these sources, and has given a new degree of interest to every thing relative to the country, about which more has been written than concerning several of the interior provinces of Europe, and which, as to climate and the productions of the soil, may be compared to the coast of Labrador in the vicinity of the Straits of Belle-Isle; but the men, like the animals, are there very different. The Kamtschadales appeared to me the same people as those of the bay of Castries, upon the coast of Tartary. Their mildness and their probity are the

* Very curious particulars, which deserve to be compared with those given by Coxe and Steller, have been furnished by Lesseps in his interesting Travels from Kamtschatka to France published in English by Johnson, St. Paul's Church Yard.

[page] 30

same, and their persons are very little different They ought then no more to be compared to the Esquimaux Indians, than the sables of Kamtschatka to the martins of Canada.

The bay of Avatscha is certainly the finest, the most, convenient, and the safest, that is to be met with in any part of the world. The entrance is narrow, and ships would be forced to pass under the guns of the forts that might be easily erected. The bottom is mud, and excellent holding ground. Two vast harbours, one on the eastern side, the other on the western, are capable of containing all the ships of the French and English navy. The rivers of Avatscha and Paratounka fall into this bay, but they are choaked up with sand-banks, and can only be entered at the time of high water. The village of St. Peter and St Paul is situated upon a tongue of land, which, like a jetty made by human art, forms behind the village a little port, shut in like an amphitheatre, in which three or four vessels might lie up for the winter. The entrance ot this sort of bason is more than twenty-five toises wide; and nature can afford nothing more safe or commodious. It is on its shore that Mr. Kasloff purposes laying down the plan of a city, which some time or other will be the capital of Kamtschatka, and perhaps the centre of an extensive trade with China, Japan, the Phillippines, and America. A vast pond of fresh water is situated northward of the site of this projected city; and at

6

[page] 31

only three hundred toises distance run a number of streamlets, the easy union of which would give the ground all the advantages necessary to a great establishment. Of these advantages Mr. Kasloff understood the value; "but first," said he a thousand times over, "we must have bread and hands, and our stock of both of them is very small." He had, however, given orders, which announced a speedy union of the other ostrogs to that of St. Peter and St. Paul, where it was his intention immediately to build a church. The Greek religion has been established among the Kamtschadales without persecution or violence, and with extraordinary facility. The vicar of Paratounka is the son of a Kamtschadale and of a Russian woman. He delivers his prayers and catechism with a tone of feeling very much to the taste of the aborigines, who reward his cases with offerings and alms, but pay no tithes. The canons of the Greek church permitting priests to marry, we may conclude that the morals of the country clergymen are so much the better. I believe them, however, to be very ignorant; and do not suppose, that for a long time to come they will stand in need of greater knowledge. The daughter, the wife, and the sister of the vicar, were the best dancers of all the women, and appeared to enjoy the best state of health. The worthy priest knew that we were good catholics, which procured us an ample aspersion of holy water; and he also made us kiss

[page] 32

the cross that was carried by his clerk: these ceremonies were performed in the midst of the village. His parsonage-house was a tent, and his altar in the open air; but his usual abode is Paratounka, and he only came to St. Peter and St. Paul's to pay us a visit.

He communicated to us a number of particulars concerning the Kuriles, of which he is also vicar, and of which he makes the tour once a year. The Russians have found it convenient to substitute numbers to the ancient names of those islands, concerning which authors are much at variance with one another. They now call them N° 1, N° 2, &c., as high as twenty-one, which last terminates the pretensions of Russia. According to the report of the vicar, it is very likely, that this last is the island of Marikan; but I am not very sure of it, because the good priest was exceedingly diffuse. We had, however, an interpreter who understood the Russian language as well as French; but Mr. Lesseps thought, that the good priest did not understand himself. The following particulars, concerning which he did not vary, may be nevertheless considered as almost certain. Of the twenty-one islands belonging to Russia, four only are inhabited—the first, the second, the thirteenth, and the fourteenth. The last two may indeed be counted only as one, because the inhabitants all pass the winter upon N° 14, and return to N° 13 to pass the summer months. The

[page] 33

others are entirely uninhabited, the islanders only landing there occasionally from their canoes for the sake of hunting foxes and otters. Several of these last mentioned islands are no better than large rocks, and there is not a tree on any one of them. The currents are very violent between the islands, particularly at the entrance of the channels, several of which are blocked up by rocks on a level with the sea. The vicar never made the voyage from Avatscha to the Kuriles in any thing but a canoe, which the Russians call baidar; and he told us, that he had several times been very nearly lost, and still nearer dying of hunger, having been driven out of sight of land; but he is persuaded, that his holy water and his cassock delivered him from the danger. The population of the four inhabited islands amounts at most to fourteen hundred souls. The inhabitants are very hairy, wear long beards, and live entirely upon seals, fish, and the produce of the chase. They have just been exempted for ten years from the tribute usually paid to Russia, because the number of otters on their islands is very much diminished. These poor people are good, hospitable, and docile, and have all embraced the Christian religion. The more southern and independent islanders sometimes pass in canoes the channels that separate them from the Russian Kuriles, in order to give some of the commodities of Japan in exchange for peltries. These islands are part of Mr. Kasloff's government; but

VOL. III. D

[page] 34

as the landing is very difficult, and as they are of little consequence to Russia he did not purpose visiting them; and, although he expressed some regret for having left a chart of them at Bolcheretsk, he did not appear to put much confidence in its accuracy. At the same time he seemed to place so much in us, that we could have wished to communicate to him the particulars of our expedition. His remarkable discretion in that respect deserves our praise.

We gave him, however, some little account of our voyage; and did not conceal from him, that we had doubled Cape Horn, visited the north-west coast of America, and put in at China, and the Philippines, whence we were come to Kamtschatka. We did not allow ourselves to enter into any farther details, but I assured him, that if the publication of our discoveries should be ordered by government, I would send him one of the first copies of the work. I had already obtained permission to send my journal to France by M. Lesseps, our young interpreter. My confidence in Mr. Kasloff and in the Russian government was such, that I should have been free from all uneasiness if I had been obliged to put my packet in the post-office; but I thought I should render a service to my country by giving M. de Lesseps an opportunity of making his own observations on the different provinces of the Russian empire, where he will probably on some future day

[page] 35

fill the place of his sacher, out consul-general at Petersburg. Mr. Kasloff told me kindly, that he would take him as his aid-de-camp as far as Okhotsk whence he would furnish him with the means of proceeding to Petersburg, and that from the present moment he should consider him as one of his family. So great a favour, so obligingly conferred, is felt more strongly than it is expressed; and it made us lament his absence at Bolcheretzk during part of our stay in the bay of Avatscha.

The cold gave us warning to depart. The ground, which on our arrival on the 7th of September, was covered with the most beautiful verdure, was as yellow and as much parched up on the 25th of the same month, as it is in the environs of Paris at the latter end of December; while the mountains of two hundred toises elevation above the level of the sea were covered with snow. 1 therefore gave orders to prepare every thing for our departure, and on the 29th got under way. Mr. Kasloff came to take leave of us, and as the calm forced us to bring up in the middle of the bay, dined on board. I accompanied him on shore with M. de Langle and several officers, and there he gave us a good supper, and another ball. The next morning, at day-break, the wind having shifted to the northward, I made the signal for sailing; and before we were well under way, heard a discharge of all the cannon of St. Peter and St.

D 2

[page] 36

Paul's I ordered a return to be made to this salute, which was repeated when we were at the mouth of the bay, the governor having sent a detachment of soldiers to pay us the honours of departure at the instant when we should pass the little battery to the north of the lighthouse that stands at the entrance.

It was not without emotion that we parted with M. de Lesseps, whose good qualities had endeared him to us all, and whom we left in a foreign land at the moment of his undertaking a journey equally long and laborious*. We carried away with us a grateful remembrance from this country, with the certitude that the laws of hospitality had never been more fully observed in any country, or in any age.

* I refer the curious reader for more ample details to de Lesseps's journal: he will there see an interesting account of all the interpreter underwent in the route from the harbour of St. Peter and St. Paul to Paris, and of the care he took to fulfil his mission, and to convey to France one of the most valuable parts of la Perouse's voyage. — (Fr. Ed.)

[page] 37

CHAPTER XXIII.

Summary account of Kamtschatka — Marks for sailing in and out of the bay of Avatscha.— We run down the latitude 37° 30′, for a space of three hundred leagues, in search of land, said to be discovered by the Spaniards in 1620.— We cross the line for the third time.— We make the island of Navigators after having passed by the island of Danger, discovered by Byron.— We are visited by a number of canoes, barter with the Indians, and anchor at the island of Maouna.

(SEPTEMBER and OCTOBER 1787)

IT is not to foreign navigators, that Russia owes her discoveries and her establishments on the coast of Oriental Tartary, and on that of the peninsula of Kamtschatka. The Russians, as eager after peltry as the Spaniards after gold and silver, have for a long time undertaken the longest and most difficult journies by land, in order to procure the valuable spoils of the sable, the fox, and the sea-otter; but being rather soldiers than hunters, they found it more convenient to impose a tribute upon the natives of the countries they subdued, than to share with them in the fatigues of the chafe.

D 3

[page] 38

They did not discover the peninsula of Kamtschatka till towards the close of the last century, their first expedition against the liberty of its wretched inhabitants having taken place in 1696. The authority of Russia was not fully acknowledged throughout the peninsula till 1711, when the Kamtschadales accepted the conditions of a tribute very little onerous, and scarcely sufficing to pay the expences of administration. Three hundred sables, two hundred red or grey fox, and a few otter skins, make up the whole revenue of Russia in that part of Asia, where she stations about four hundred soldiers, mostly Cossacks and Siberians, and several officers who command in the different districts.

The court of Russia has several times changed the form of government in the peninsula. That which the English found established in 1778 no longer existed in 1784. Kamtschatka then became a province of the government of Okhotsk, which is itself a dependency of the sovereign court of Irkoutsk.

The ostrog of Bolcheretsk, formerly the capital of Kamtschatka, where major Behm resided at the time the English arrived, is now only governed by a serjeant of the name of Martinof. Mr. Kaborof, a lieutenant, commands, as I have already said, at St. Peter and St. Paul's; major Elleonoff at Nijenei-Kamtschatka, or the ostrog of Lower

[page] 39

Kamtschatka; and lastly Verknei, or Upper Kamtschatka, is under the command of serjeant Momayeff. These several commandants are under no responsibility to one another; but each renders his own account directly to the governor of Okhotsk, who has established an inspector with the rank of major, and with a particular command over the Kamtschadales, no doubt to protect them against the presumed oppression of the military government.

This first view of the commerce of these countries would give but a very imperfect idea of the advantages that Russia derives from its colonies in the eastern parts of Asia, if the reader were not aware, that expeditions by land have been followed by voyages eastward of Kamtschatka towards the coasts of America. Those of Behring, and Tschirikow are known to all Europe. After the names of these men rendered famous by their adventurous expeditions, and by the misfortunes that eventually attended them, those of several other navigators may be mentioned, who have added to the possessions of Russia the Aleutian Islands, the cluster to the east known by the name of Oonalashka, and all the islands to the south of the peninsula.

Captain Cook's last voyage suggested expeditions still farther eastward; but 1 was told at Kamtschatka, that the natives of the countries where the Russians landed had refused to pay them tri

D 4

[page] 40

bute, and even to have any dealing with them. The latter probably were injudicious enough to let them perceive the design they had formed of subduing them; and every one knows how proud the Americans are of their independence, and how jealous of their liberty,

Russia has been at very little charge in extending her dominions. Commercial houses fit out vessels at Okhotsk, where they are built at enormous expence. They are from forty-five to fifty feet long, with a single mast in the middle, much like our cutters, and carry forty or fifty men, who are all better hunters than seamen. They sail from Okhotsk in the month of June, generally pass between the point of Lopatka, and the first of the Kuriles, steer eastward, and continue for three or four years to run from island to island, till they have either bought of the natives, or killed a sufficient number of otters themselves, to pay the expense of the out-fit, and to afford the merchants a profit of cent per cent upon the capital advanced.

Russia has not yet made any permanent establishment eastward of Kamtschatka: each vessel forms a temporary one in the port where it winters, and when it sails either destroys or gives it up to some other vessel belonging to the nation. The governor of Okhotsk strictly enjoins the captains of these cutters to make all the islanders they visit acknowledge the authority of Russia, and he em-

[page] 41

barks on board each vessel a sort of custom-house officer commissioned to impose and levy a duty for the crown. I was told, that a missionary was to set off from Okhotsk without delay, in order to preach the Christian religion to the people that have been subjugated, and thus to make them some sort of compensation by spiritual gifts for the tribute they exact by right of superior power.

It is well known, that furs fetch a very high price at Kiatcha, upon the frontiers of China and Russia; but it is only since the publication of Mr. Coxe's work, that we have been acquainted in Europe with the importance of that article of commerce, of which the exportation and importation fall little short of eighteen millions of livres * a year. I was assured that twenty-five vessels, the crews amounting to about a thousand men, Kamtschadales, Russians, and Cossacks, had been sent this very year in quest of furs to the eastward of Kamtschatka. These vessels will disperse themselves from Cook's river to Behring's island. Long experience has taught them, that the otters scarcely ever frequent the latitudes farther north than the 60th degree; a circumstance that directs all the adventurers towards the peninsula of Alashka, or still farther east, but never to Behring's straits, which are obstructed by everlasting ice.

When these vessels come back they sometimes put in at the bay of Avatscha; but always return

* £. 750,000.

[page] 42

ultimately to Okhotsk, the usual residence of their owners, and of the merchants who go to trade directly with the Chinese upon the frontiers of the two empires. As the ice leaves the entrance of the bay of Avatscha open at all times, the Russian navigators generally put in there when the season is too far advanced for them to arrive at Okhostk before the end of September; a very wise regulation of the empress of Russia having forbidden the navigation of the sea of Okhotsk after that epoch, at which those hurricanes and gales of wind begin that have occasioned very frequent shipwrecks in that quarter.

The ice never extends in the bay of Avatscha farther than three or four hundred toises from the shore; and it often happens, during the winter, that the land winds drift away that which blocks up the mouths of the rivers of Paratounka and Avatscha. The navigation of these rivers then becomes practicable.

As the winter is generally less severe in Kamtschatka, than it is at Petersburg, and in several provinces of the Russian empire, the Russians generally speak of it as the French do of that of Provence; but the snow which surrounded us as early as the 20th of September, the white frost that covered the ground every morning, and the grass, as completely withered as that of the environs of Paris in the month of January, all combined to indicate a win-

[page] 43

ter of which the severity must be insupportable to the inhabitants of the south of Europe.

We were, however, in some respects less chilly than the Russian and Kamtschadale inhabitants of the ostrog of St. Peter and St. Paul. They were clothed with the thickest skins, and the temperature of their isbas, in which stoves are constantly burning, was from twenty-eight to thirty degrees above the freezing point. The heated air deprived us of res piration, and obliged the lieutenant to open the windows whenever we were in his apartment. The people of this country have inured themselves to the extremes of heat and cold. It is well known, that their custom, in Europe as well as in Asia, is to go into vapour baths, come out covered with perspiration, and immediately roll themselves in the snow. The ostrog of St. Peter had two of these public baths, into which I went before the fires were lighted. They consist of a very low room, in the middle of which is an oven constructed of stones, without cement, and heated like those intended to bake bread. Its arched roof is fur- rounded by fears one above another, like an amphitheatre, for those who wish to bathe, so that the heat is greater or less, according as the per- son is placed upon a higher or lower bench. Water thrown upon the top of the roof, when heated red- hot by the fire underneath, is converted instantly into vapour, and excites the most profuse perspi-

[page] 44

ration. The Kamtschadales have borrowed this custom, as well as many others, from their conquerors; and ere long the primitive character that distinguished them so strongly from the Russians will be entirely effaced. Their population at present does not exceed four thousand souls, scattered over the whole peninsula, which extends from the fifty-first to the sixty-third degree of latitude, and occupies several degrees of longitude. Hence it appears, that there are several square leagues for each individual. They cultivate no one production of the earth; and the preference they give to dogs over rein-deer in drawing their sledges, prevents their breeding either hogs, sheep, rein-deer, horses, or oxen, because these animals would be devoured before they could acquire sufficient strength to defend themselves. Fish is the principal food of their draught dogs, which go notwithstanding as much as twenty-four leagues a day. They are never fed till they come to their journey's end.

The reader has already seen, that this manner of travelling is not peculiar to the Kamtschadales. The people of Tchoka, and the Tartars of the bay of Castries use no other cattle. We were exceedingly desirous to know whether the Russians were at all acquainted with those countries, and were told by Mr. Kasloff, that the Okhotsk vessels had several times perceived the north end of the

[page] 45

island, at the mouth of the great river Amur, but that they had never landed, because it is beyond the limits of the Russian establishments upon that coast

The bay of Avatscha. very much resembles that of Brest; but it affords much better holding ground, its bottom being mud. Its entrance is also narrower, and consequently more easy to defend. Our lithologists and botanists found neither mineral nor vegetable substances upon its shores, but such as are exceedingly common in Europe. The English have published a very good chart of this bay. Attention should be paid to two banks, situated east and west of the entrance, and separated by a large channel for vessels to pass through. They may be avoided with certainty by keeping two insulated rocks on the east coast open with the light-house point, and by shutting in with the west coast a large rock on the larboard hand, which is only separated from the land by a passage not more than a cable's length in width. All the anchorage in the bay is equally good; and ships may approach more or less near to the ostrog, according to the intercourse they wish to keep up with the shore.

According to the observations of M. Dagelet, the house of lieutenant Kabroof is situated in 53° I' north latitude, and 156° 30′ east longitude. The tides are very regular. It is high water at half past three, at the time of full and change of the

7

[page] 46

moon, the rise in the harbour being four feet. We observed that our time-keeper, No. 19, lost 10" a day, which differed 2" from the daily loss attributed to the same at Cavite fix months before.

The north wind, which was so favourable to our sailing out of the bay of Avatscha, deserted us when we were two leagues in the offing. It shifted to the west, and continued to blow with an obstinacy and violence, which did not permit me to follow my plan of reconnoitring, and laying down the latitude and longitude of the Kuriles, as far as the isle of Marikan. The gales of wind and squalls followed each other so rapidly, that I was often obliged to lay to under the forefail, and found myself driven eighty leagues from the land. I did not attempt to struggle against these obstacles, the reconnoitring of the Kurile islands being of little importance; but steered a course so calculated as to cross the parallel of latitude of 37° 30′ in the longitude of 165°, where several geographers have placed a large, rich, and well-peopled island, said to have been discovered by the Spaniards in 1620. A search after this island made part of captain Uriès' instructions; and there is also a paper with some particulars concerning it, in the fourth volume of the academical collection, under the foreign head. It appeared to me, that among the different objects of research rather indicated than ordered by my instructions, this deserved a preference. I did

[page] 47

not reach the latitude 3° 30′ till the 14th, at midnight, in the course of which day we had seen several small land birds of the linnet genus settle upon our rigging. The same evening we also perceived two flights of ducks, or corvorants, birds which scarcely ever wander far from land. The weather was very clear, and in both frigates we had men constantly upon the look-out from the mast-head, a reward somewhat considerable being promised to him who should first see land. This motive of emulation was little necessary, every sailor being eager for the honour of discovering an island, which, according to my promise, was to bear his name. But, notwithstanding the certain indications of our being near land, we discovered nothing, although the horizon was very extensive. I supposed that the island in question must lie farther south, and that the violent gales that had recently blown from that quarter, had driven northward the little birds that we had observed to settle upon our rigging. I therefore steered a south course till midnight. Being then exactly, as I have said above, in 37° 30′ latitude north, I gave directions to steer due east, under very easy fail, waiting for the day with the utmost impatience. It was done, and we again saw two small birds. I continued an east course, and the same evening a large turtle passed along-side of the ship. The following day, still running down the same parallel towards the east,

1

[page] 48

we saw a bird, smaller than the European wren, perched upon the main-top-sail yard arm, and a third flight of ducks. Thus were our hopes every moment kept up; but we never had the good fortune to see them realized *.

During this search we met with a real misfortune. A seaman fell overboard from the Astrolabe while furling the mizen-top-gallant-fail. Whether he was wounded in his fall, or could not swim, I know not; but he never rose again, and all our efforts to save him were of no avail.

The signs of land continued on the 18th and 19th, although we had made a long run to the eastward. We perceived flights of ducks and other birds that frequent the shore: a soldier even pretended that he saw some small bits of sea-weed (goemon) float by; but as this fact was supported by no other testimony, we rejected it unanimously, preserving nevertheless the

* Was la Pérouse ignorant, that the parallel of 37° 30′ north had been run down to no purpose, for a space of 450 miles, towards the east of Japan, by the ship Kastricum? Or was he afraid to depart from his instructions, and from the indication given him in the forty-eighth geographical note inserted in the first volume? Whatever motive may have determined his conduct, it is matter of regret, that la Pérouse did not follow the 37th or 38th parallel of latitude. The land discovered in former times having been almost all discovered in our own, this island will certainly be the object of new researches; and there is reason to hope it will be found by running down the parallel of 36° 30′.— (Fr. Ed.)

[page] 49

strongest hopes of speedily making land. Scarcely had we reached the 175th degree of east longitude, when all these signs disappeared. I continued, however, the same course till the 22d at noon; but at that epoch the longitude indicated by the time keeper, No. 19, placing me at 20′ beyond 180° east of Paris, the limits prescribed for the search of the island in question, I ordered a southerly course to be steered, in order to meet with less stormy seas. Since our departure from Kamtschatka we had constantly navigated in the midst of a very heavy swell; and at one time a sea washed away our jolly-boat, though lashed to the gangway, and threw more than twenty tons of water aboard. These little accidents would hardly have been noticed, had we been fortunate enough to meet with the island, the search of which had cost us so much fatigue, and which certainly exists in the neighbourhood of the course we steered. The signs of land were too frequent, and of too decided a nature, to permit us to doubt it. I am inclined to think, that we ran down too northerly a parallel; and were I to begin the same search again, I should follow the parallel of 35°, from 160 to 170° of longitude. In that space it was, that we perceived the greatest number of land birds, which appeared to me to come from the south, and to have been I driven to sea by the violence of the gales that had blown from that quarter. The farther objects of

VOL. III. E

[page] 50

my voyage did not give me time to verify this conjecture, by running as far westward as we had just run east. The wind, which blows almost invariably from the west, would have made me consume more than two months in a passage that I had made in eight days. I therefore shaped my course towards the southern hemisphere, in that vast field of discoveries where the tracks of Quiros, Mendana, Tasman, &c. are crossed in every direction by those of modern navigators, and where every one of the latter has added some new islands to those which were already known; but concerning which the curiosity of Europeans still desired more circumstantial details, than those given in the narratives of the earlier navigators. It is well known, that in that vast part of the great equatorial ocean there exists a zone, from 12 to 15 degrees, from north to south, and of 140 degrees from east to west, interspersed with islands, which are upon the terrestrial globe what the milky way is in the heavens. The language and manners of their inhabitants are no longer unknown to us; and the observations that have been made by the last circumnavigators even enable us to form probable conjectures concerning the origin of these people, which may be attributed to the Malays, as that of the different colonies on the coasts of Africa and Spain is to the Phenicians. It was in this Archipelago that my instructions directed me to navigate during the third year of my

[page] 51