[page 1]

A

VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY

TO THE

NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN,

AND

ROUND THE WORLD.

VOL. I.

[page 2]

[page 3]

A

VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY

TO THE

NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN,

AND

ROUND THE WORLD:

IN WHICH THE COAST OF NORTH-WEST AMERICA HAS BEEN CAREFULLY

EXAMINED AND ACCURATELY SURVEYED.

Undertaken by HIS MAJESTY'S Command,

PRINCIPALLY WITH A VIEW TO ASCERTAIN THE EXISTENCE OF ANY

NAVIGABLE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN THE

North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans;

AND PERFORMED IN THE YEARS

1790, 1791, 1792, 1793, 1794, and 1795,

IN THE

DISCOVERY SLOOP OF WAR, AND ARMED TENDER CHATHAM,

UNDER THE COMMAND OF

CAPTAIN GEORGE VANCOUVER.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR G. G. AND J. ROBINSON, PATERNOSTER-ROW;

AND J. EDWARDS, PALL-MALL.

1798.

[page 4]

[page 5]

TO THE KING.

SIR,

YOUR MAJESTY having been graciously pleased to permit my late brother CAPTAIN GEORGE VANCOUVER, to present to YOUR MAJESTY the Narrative of his labours during the execution of your commands in the Pacific Ocean, I presume to hope, that, since it has pleased the Divine Providence to withdraw him from YOUR MAJESTY'S service, and from the society of his friends, before he could avail himself of that condescension, YOUR MAJESTY will, with

[page 6]

the same benignity, vouchsafe to accept it from my hands, in discharge of the melancholy duty which has devolved upon me by that unfortunate event.

I cannot but indulge the hope that the following pages will prove to YOUR MAJESTY, that CAPTAIN VANCOUVER was not undeserving the honour of the trust reposed in him; and that he has fulfilled the object of his commission from YOUR MAJESTY with diligence and fidelity.

Under the auspices of YOUR MAJESTY, the late indefatigable CAPTAIN COOK had already shewn that a southern continent did not exist, and had ascertained the important fact of the near approximation of the northern shores of Asia to those of America. To those great discoveries the exertions of CAPTAIN VANCOUVER will, I trust, be found to have added the complete certainty, that, within the limits of his researches on the continental shore of North-West America,

[page 7]

NO INTERNAL SEA, OR OTHER NAVIGABLE COMMUNICATION whatever exists, uniting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

I have the honour to be,

SIR,

With the most profound respect,

YOUR MAJESTY'S

Most faithful and devoted

Subject and servant,

JOHN VANCOUVER.

[page 8]

[page i]

INTRODUCTION.

IN contemplating the rapid progress of improvement in the sciences, and the general diffusion of knowledge, since the commencement of the eighteenth century, we are unavoidably led to observe, with admiration, that active spirit of discovery, by means of which the remotest regions of the earth have been explored; a friendly communication opened with their inhabitants; and various commodities, of a most valuable nature, contributing either to relieve their necessities, or augment their comforts, introduced among the less-enlightened part of our species. A mutual intercourse has been also established, in many instances, on the solid basis of a reciprocity of benefits; and the productive labour of the civilized world has found new markets for the disposal of its manufactures. Nor has the balance of trade been wholly against the people of the newly-discovered countries; for, whilst some have been enabled to supply their visitors with an abundance of food, and the most valuable refreshments, in exchange for iron, copper, useful implements, and articles of ornament; the industry of others has been stimulated to procure the skins of animals, and other articles of a commercial nature; which they have found to be eagerly fought for by the traders who now resort to their shores from Europe, Asia, and the eastern side of North America.

Vol. I. a

[page] ii

The great naval powers of Europe, inspired with a desire not only of acquiring, but also of communicating, knowledge, had extended their researches, in the 16th and 17th centuries, as far into the pacific ocean as their limited information of the geography of the earth, at that time, enabled them to penetrate. Some few attempts had also been made by this country towards the conclusion of each of those centuries; but it was not until the year 1764 that Great-Britain, benefiting by the experience of former enterprizes, laid the foundation for that vast accession of geographical knowledge, which she has since obtained by the persevering spirit of her successive distinguished circumnavigators.

By the introduction of nautical astronomy into marine education, we are taught to sail on the hypothenuse, instead of traversing two sides of a triangle, which was the usage in earlier times; by this means, the circuitous course of all voyages from place to place is considerably shortened; and it is now become evident, that sea officers of the most common-rate abilities, who will take the trouble of making themselves acquainted with the principles of this science, will, on all suitable occasions, with proper and correct instruments, be enabled to acquire a knowledge of their situation in the atlantic, indian, or pacific oceans, with a degree of accuracy sufficient to steer on a meridional or diagonal line, to any known spot; provided it be sufficiently conspicuous to be visible at any distance from five to ten leagues.

This great improvement, by which the most remote parts of the terrestrial globe are brought so easily within our reach, would, nevertheless, have been, comparatively, of little utility, had not those happy means been discovered, for preserving the lives and health of the officers and seamen engaged in such distant and perilous undertakings; which

[page] iii

were so successfully practised by Captain Cook the first great discoverer of this salutary system, in all his latter voyages round the globe. But in none have the effects of his wise regulations regimen, and discipline, been more manifest, than in the course of the expedition of which the following pages are designed to treat. To an unremitting attention, not only to food, cleanliness, ventilation, and an early administration of antiseptic provisions and medicines, but also to prevent, as much as possible, the chance of indisposition, by prohibiting individuals from carelessly exposing themselves to the influence of climate, or unhealthy indulgences in times of relaxation, and by relieving them from fatigue and the inclemency of the weather the moment the nature of their duty would permit them to retire; is to be ascribed the preservation of the health and lives of sea-faring people on long voyages. Instead of vessels returning from parts, by no means very remote, with the loss of one half, and sometimes two thirds, of their crews, in consequence of scorbutic, and other contagious disorders; instances are now not wanting of laborious services having been performed in the most distant regions, in which, after an absence of more than three or four years, during which time the vessels had been subjected to all the vicissitudes of climate, from the scorching heat of the torrid zone to the freezing blasts of the arctic or antarctic circles, the crews have returned in perfect health, and consisting nearly of every individual they had carried out; whilst those who unfortunately had not survived, either from accident or disease, did not exceed in number the mortality that might reasonably have been expected, during the same period of time, in the most healthy situations of this country. To these valuable improvements, Great-Britain is, at this time, in a great measure indebted, for her present exalted station amongst

a 2

[page] iv

the nations of the earth; and it should seem, that the reign of George the Third had been reserved, by the Great Disposer of all things, for the glorious task of establishing the grand key-stone to that expansive arch, over which the arts and sciences should pass to the furthermost corners of the earth, for the instruction and happiness of the most lowly children of nature. Advantages so highly beneficial to the untutored parts of the human race, and so extremely important to that large proportion of the subjects of this empire who are brought up to the sea service, deserve to be justly appreciated; and it becomes of very little importance to the bulk of our society, whose enlightened humanity teaches them to entertain a lively regard for the welfare and interest of those who engage in such adventurous undertakings for the advancement of science, or for the extension of commerce, what may be the animadversions or sarcasms of those few unenlightened minds that may peevishly demand, "what beneficial consequences, if any, have followed, or are likely to follow, to the discoverers, or to the discovered, to the common interests of humanity, or to the increase of useful knowledge, from all our boasted attempts to explore the distant recesses of the globe?" The learned editor*, who has so justly anticipated this injudicious remark, has, in his very comprehensive introduction to Captain Cook's last Voyage, from whence the above quotation is extracted, given to the public, not only a complete and satisfactory answer to that question, but has treated every other part of the subject of Discovery so ably, as to render any further observations on former voyages of this description totally unnecessary, for the purpose of bringing the reader acquainted with what

* Dr. Douglas, now Bishop of Salisbury.

[page] v

had been accomplished, previously to my being honored with His Majesty's commands to follow up the labours of that illustrious navigator Captain James Cook; to whose steady, uniform, indefatigable, and undiverted attention to the several objects on which the success of his enterprizes ultimately depended, the world is indebted for such eminent and important benefits.

Those benefits did not long remain unnoticed by the commercial part of the British nation. Remote and distant voyages being now no longer objects of terror, enterprizes were projected. and carried into execution, for the purpose of establishing new and lucrative branches of commerce between North West America and China; and parts of the coast of the former that had not been minutely examined by Captain Cook, became now the general resort of the persons thus engaged.

Unprovided as these adventurers were with proper astronomical and nautical instruments, and having their views directed almost intirely to the object of their employers, they had neither the means, nor the leisure, that were indispensably requisite for amassing any certain geographical information. This became evident, from the accounts of their several voyages given to the public; in which, notwithstanding that they positively contradicted each other, as well in geographical and nautical facts as in those of a commercial nature, they yet agreed in filling up the blanks in the charts of Captain Cook with extensive islands, and a coast apparently much broken by numberless inlets, which they had left almost intirely unexplored.

The charts accompanying the accounts of their voyages, representing the North West coast of America to be so much broken by the waters of the pacific, gave encouragement once more to hypotheses;

[page] vi

and the favorite opinion that had slept since the publication of Captain Cook's last voyage of a north-eastern communication between the waters of the pacific and atlantic oceans, was again roused from its slate of slumber, and brought forward with renovated vigour. Once more the archipelago of St. Lazarus was called forth into being, and its existence almost assumed, upon the authority of a Spanish admiral named De Fonte, De Fonta, or De Fuentes; and of a Mr. Nicholas Shapely, from Boston in America, who was stated to have penetrated through this archipelago, by failing through a mediterranean sea, on the coast of North-West America, within a few leagues of the oceanic shores of that archipelago; where he is said to have met the Admiral. The straits said to have been navigated by Juan De Fuca were also brought forward in support of this opinion; and, although the existence or extent of these discoveries remained still to be proved by an authenticated survey of the countries which had been thus stated to have been seen and passed through, yet the enthusiasm of modern closet philosophy, eager to revenge itself for the refutation of its former fallacious speculations, ventured to accuse Captain Cook of "hastily exploding" its systems; and, ranking him amongst the pursuers of peltry, dared even to drag him forward himself in support of its visionary conjectures.

With what reason, or with what justice, such animadversions have been cast upon one, who, unhappily for the world, does not survive to enforce his own judicious opinions; influenced as they were, by no prejudice, nor biassed by any pre-conceived theory or hypothesis, but founded on the solid principles of experience, and of ocular demonstration; it is not my province to decide: let it suffice to say, that the labours of that distinguished character will remain a monument of his pre-eminent

[page] vii

abilities, and dispassionate investigation of the truth, as long as science shall be respected in the civilized world; or as long as succeeding travellers, who shall unite in bearing testimony to the profundity of his judgment, shall continue to obtain credit with the public.

Although the ardour of the present age, to discover and delineate the true geography of the earth, had been rewarded with uncommon and unexpected success, particularly by the persevering exertions of this great man, yet all was not completed; and though, subsequent to his last visit to the coast of North-West America, no expedition had been projected by Government, for the purpose of acquiring a more exact knowledge of that extensive and interesting country; yet a voyage was planned by His Majesty for exploring some of the Southern regions; and in the autumn of the year 1789 directions were given for carrying it into effect.

Captain Henry Roberts, of known and tried abilities, who had served under Captain Cook during his two last voyages, and whose attention to the scientific part of his profession had afforded that great navigator frequent opportunities of naming him with much respect, was called upon to take charge of, and to command, the proposed expedition.

At that period, I had just returned from a flation at Jamaica under the command of Commodore (now Vice-Admiral) Sir Alan Gardner, who mentioned me to Lord Chatham and the Board of Admiralty; and I was solicited to accompany Captain Roberts as his second. In this proposal I acquiesced, and found myself very pleasantly situated, in being thus connected with a fellow-traveller for whose abilities I bore the greatest, respect, and in whose friendship and good opinion I was proud to pos-

[page] viii

sess a place. And as we had failed together with Captain Cook on his voyage towards the south pole, and as both had afterwards accompanied him with Captain Clerke in the Discovery during his last voyage, I had no doubt that we were engaged in an expedition, which would prove no less interesting to my friend than agreeable to my wishes.

A ship, proper for the service under contemplation, was ordered to be provided. In the yard of Messrs. Randall and Brent, on the banks of the Thames, a vessel of 340 tons burthen was nearly finished; and as she would demand but few alterations to make her in every respect fit for the purpose, the was purchased; and, on her being launched, was named the Discovery.

The first day of the year 1790 the Discovery was commissioned by Captain Roberts; some of the other officers were also appointed, and the ship was conducted to His Majesty's dock-yard at Deptford, where the was put into a state of equipment; which was ordered to be executed, with all the dispatch that the nature of the service required.

For some time previous to this period the Spaniards, roused by the successful efforts of the British nation, to obtain a more extended knowledge of the earth, had awoke, as it were, from a slate of lethargy, and had not only ventured to visit some of the newly-discovered islands in the tropical regions of the pacific ocean, but had also, in the year 1775, with a spirit somewhat analogous to that which prompted their first discovery of America, extended their researches to the northward, along the coast of North-West America. But this undertaking did not seem to have reached beyond the acquirement of a very superficial knowledge of the shores; and though these were found to be extremely broken, and divided by the waters of the pacific, yet it does

2

[page] ix

not appear that any measures were pursued by them for ascertaining the extent, to which those waters penetrated into the interior of the American continent.

This apparent indifference in exploring new countries, ought not, however, to be attributed to a deficiency in skill, or to a want of spirit for enterprize, in the commander* of that expedition; because there is great reason to believe, that the extreme caution which has so long and so rigidly governed the court of Madrid, to prevent, as much as possible, not only their American, but likewise their Indian, establishments from being visited by any Europeans, (unless they were subjects of the crown of Spain, and liable to a military tribunal) had greatly conspired, with other considerations of a political nature, to repress that desire of adding to the fund of geographical knowledge, which has so eminently distinguished this country. And hence it is not extraordinary, that the discovery of a north-western navigable communication between the atlantic and pacific oceans, should not have been considered as an object much to be desired by the Spanish court. Since that expedition, however, the Spaniards seem to have considered their former national character as in some measure at stake; and they have certainly become more acquainted than they were with the extensive countries immediately adjoining to their immense empire in the new world; yet the measures that they adopted, in order to obtain that information, were executed in so defective a manner, that all the important questions to geography still remained undecided, and in the same state of uncertainty.

Towards the end of april, the Discovery was, in most respects, in a condition to proceed down the river, when intelligence was received

* Senr. Quadra.

Vol. I. b

[page] x

that the Spaniards had committed depredations on different branches of the British commerce on the coast of North-West America, and that they had seized on the English vessels and factories in Nootka sound. This intelligence gave rise to disputes between the courts of London and Madrid, which had the threatening appearance of being terminated by no other means than those of reprizal. In consequence of this an armament took place, and the further pacific equipment of the Discovery was suspended; her stores and provisions were returned to the respective offices, and her officers and men were engaged in more active service. On this occasion I resumed my profession under my highly-esteemed friend Sir Alan Gardner, then captain of the Courageux, where I remained until the 17th of the november following; when I was ordered to repair to town for the purpose of attending to the commands of the Board of Admiralty.

The uncommon celerity, and unparalleled dispatch, which attended the equipment of one of the noblest fleets that Great-Britain ever saw, had probably its due influence upon the court of Madrid, for, in the Spanish convention, which was consequent on that armament, restitution was offered to this country for the captures and aggressions made by the subjects of His Catholic Majesty; together with an acknowledgment of an equal right with Spain to the exercise and prosecution of all commercial undertakings in those seas, reputed before to belong only to the Spanish crown. The extensive branches of the fisheries, and the fur trade to China, being considered as objects of very material importance to this country, it was deemed expedient, that an officer should be sent to Nootka to receive back, in form, a restitution of the territories on which the Spaniards had seized, and also to make an accurate

[page] xi

survey of the coast, from the 30th degree of north latitude north-west ward toward Cook's river; and further, to obtain every possible information that could be collected respecting the natural and political state of that country.

The outline of this intended expedition was communicated to me, and I had the honor of being appointed to the command of it. At this juncture it appeared to be of importance, that all possible exertion should be made in its equipment; and as the Discovery, which had been selected on the former occasion, was now rigged, some of her stores provided, and she herself considered, in most respects, as a vessel well calculated for the voyage under contemplation, she was accordingly directed to be got ready for that service; and the Chatham armed tender, of 135 tons burthen, built at Dover, having been destined to accompany the Discovery in the voyage which had been abandoned, she was ordered to be equipped to attend on the voyage now to be undertaken, and was sent to Woolwich to receive such necessary repairs and alterations as were deemed requisite for the occasion.

The Discovery was copper-fastened, sheathed with plank, and coppered over; the Chatham only sheathed with copper. The former mounted ten four-pounders, and ten swivels; the latter, four three-pounders and six swivels. The following list will exhibit the establishment of the officers and men in the two vessels.

b 2

[page] xii

An account of the number of officers and men on board the Discovery sloop of war, in december, 1790.

| OFFICERS. | NO. | NAMES. |

| Captain, | 1 | George Vancouver. |

| Lieutenants | 3 | Zachariah Mudge, |

| Peter Puget, | ||

| Joseph Baker. | ||

| Master | 1 | Joseph Whidbey. |

| Boatswain | 1 | |

| Carpenter | 1 | |

| Gunner | 1 | |

| Surgeon | 1 | |

| Midshipmen | 6 | |

| Master's mates | 3 | |

| Boatswain's mates | 3 | |

| Carpenter's mates | 3 | |

| Gunner's mates | 2 | |

| Surgeon's mates | 2 | |

| Carpenter's crew | 4 | |

| Master at arms | 1 | |

| Corporal | 1 | |

| Sail-maker | 1 | |

| Sail-maker's mate | 1 | |

| Armourer | 1 | |

| Cook | 1 | |

| Cook's mate | 1 | |

| Clerk | 1 | |

| Quartermasters | 6 | |

| Able seamen | 38 | |

| Serjeant | 1 | Marines. |

| Corporal | 1 | |

| Privates | 14 | |

| Total | 100 |

[page] xiii

An account of the number of officers and men on board the Chatham armed tender, in december, 1790.

| OFFICERS. | NO. | NAMES. |

| Commander | 1 | Lieutenant W.R. Broughton. |

| Lieutenant | 1 | James Hanfon. |

| Master | 1 | James Johnstone. |

| Boatswain | 1 | |

| Carpenter | 1 | |

| Gunner | 1 | |

| Surgeon | 1 | |

| Midshipmen | 4 | |

| Master's mates | 2 | |

| Boatswain's mates | 2 | |

| Carpenter's mates | 2 | |

| Gunner's mates | 2 | |

| Surgeon's mate | 1 | |

| Sail-maker | 1 | |

| Armourer | 1 | |

| Clerk | 1 | |

| Quartermasters | 4 | |

| Able seamen | 10 | |

| Serjeant | 1 | Marines. |

| Privates | 7 | |

| Total | 45 |

[page] xiv

I had great reason to be satisfied with these arrangements: the second and third lieutenants, and the master of the Discovery, whom I had the honor of being allowed to name for this service, had all served some years with me, under the command of Sir Alan Gardner, both at home, and in the West-Indies; the other officers were men of known character, possessing good abilities, and excellent dispositions, which their subsequent conduct and zeal, exhibited on all occasions, sufficiently demonstrated.

In the former equipment of the Discovery, Captain Roberts and myself had undertaken to make all such astronomical and nautical observations, as the circumstances occurring in the voyage might demand. This talk now devolped upon me alone; but with the assistance of Mr. Whidbey, I entertained little doubt of accomplishing the proposed object, at least in an useful manner; for which purpose we were supplied by the Navy Board with such an assortment of instruments as I considered to be necessary.

It was with infinite satisfaction that I saw, amongst the officers and young gentlemen of the quarter-deck, some who, with little instruction, would soon be enabled to construct charts, take plans of bays and harbours, draw landscapes, and make faithful portraits of the several headlands, coasts, and countries, which we might discover; thus, by the united efforts of our little community, the whole of our proceedings, and the information we might obtain in the course of the voyage, would be rendered profitable to those who might succeed us in traversing the remote parts of the globe that we were destined to explore, without the assistance of professional persons, as astronomers or draftsmen.

2

[page] xv

Botany, however, was an object of scientific inquiry with which no one of us was much acquainted; but as, in expeditions of a similar nature, the most valuable opportunities had been afforded for adding to the geral stock of botanical information, Mr. Archibald Menzies, a surgeon in the royal navy, who had before visited the pacific ocean in one of the vessels employed in the fur trade, was appointed for the specific purpose of making such researches; and had, doubtless, given sufficient proof of his abilities, to qualify him for the station it was intended he should sill. For the purpose of preserving such new or uncommon plants as he might deem worthy of a place amongst His Majesty's very valuable collection of exotics at Kew, a glazed frame was erected on the after part of the quarter-deck, for the reception of those he might have an opportunity of collecting.

The Board of Admiralty, greatly attentive to our personal comforts, gave directions that the Discovery and Chatham should each be supplied with all such articles as might be considered in any way likely to become necessary, during the execution of the long and arduous service in which we were about to engage. Our stores, from the naval arsenals, were ordered to be selected of the very best forts, and to be made with materials of the best quality. In addition to the ordinary establishment, we were supplied with a large assortment of seines and other useful fishing geer of various kinds. The provisions were furnished at the victualling-office with the greatest care, all of which proved to be excellent, and manifested the judgment which had been exercised in the selection and preparation of the several articles. To these were added a large proportion of sour-krout, portable soup, wheat instead of the usual supply of oatmeal for breakfast, the essence of malt

[page] xvi

and spruce, malt, hops, dried yeast, flour, and seed mustard; which may all be considered as articles of food. Those of a medicinal nature, with which we were amply supplied, were Dr. James's powders; vitriolic elixir; the rob of lemons and oranges, in such quantities and proportions as the surgeon thought requisite; together with an augmentation to the usual allowance, amounting to a hundred weight, of the best peruvian bark.

To render our visits as acceptable as possible to the inhabitants of the islands or continent in the pacific ocean, and to establish on a firm basis a friendly intercourse with the several tribes we might occasionally meet with, Lord Grenville directed that a liberal assortment of various European commodities, both of a useful and ornamental nature, should be sent on board from the Secretary of State's office. From the Board of Ordnance the vessels were supplied with every thing necessary for our defence, and amongst other articles were four well-contrived three pound field pieces, for the protection of our little encampment against any hostile attempts of the native Indians, amongst whom we should necessarily have frequent occasion to reside on shore; and for the amusement and entertainment of such as were peaceably and friendly disposed towards us, we were furnished with a most excellent assortment of well-prepared fireworks. So that nothing seemed to have been forgotten, or omitted, that might render our equipment as complete, as the nature of the service we were about to execute could be considered to demand. But as I have hitherto only pointed out in general terms the outline of the intended expedition; the various objects it proposed to embrace, and the end it was expected to answer, will be more clearly perceived by the perusal of the instructions under which I was to sail, and by which I

[page] xvii

was to govern my conduct; which will enable the reader to form a judgment, how far His Majesty's commands, during this voyage, have been properly carried into execution.

"By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great-Britain and Ireland, &c.

The KING having judged it expedient, that an expedition should be immediately undertaken for acquiring a more complete knowledge, than has yet been obtained, of the north-west coast of America; and, the sloop you command, together with the Chatham armed tender, (the Lieutenant commanding which, has been directed to follow your orders) having been equipped for that service; you are, in pursuance of His Majesty's pleasure, signified to us by Lord Grenville, one of His principal Secretaries of State, hereby required and directed, to proceed, without loss of time, with the said sloop and tender, to the Sandwich islands in the north pacific ocean, where you are to remain during the next winter; employing yourself very diligently in the examination and survey of the said islands; and, as soon as the weather shall be favorable, (which may be expected to be in february, or at latest in march, 1792) you are to repair to the north-west coast of America, for the purpose of acquiring a more complete knowledge of it, as above-mentioned.

It having been agreed, by the late convention between His Majesty and the Catholic King, (a printed copy of which you will receive herewith) that the buildings and tracts of land, situated on the north-west coast above-mentioned, or on islands adjacent thereto, of which the subjects of His Britannic Majesty were dispossessed about the month of april, 1789, by a Spanish officer, shall be restored to the said British

VOL. I. c

[page] xviii

subjects, the court of Spain has agreed to send orders, for that purpose, to its officers in that part of the world; but, as the particular specification of the parts to be restored may still require some further time, it is intended that the King's orders, for this purpose, shall be sent out to the Sandwich islands, by a vessel to be employed to carry thither a further store of provisions for the sloop and armed tender above-mentioned, which it is meant shall sail from this country in time to reach those islands in the course of next winter.

If, therefore, in consequence of the arrangement to be made with the court of Spain, it should hereafter be determined that you should proceed, in the first instance, to Nootka, or elsewhere, in order to receive, from the Spanish officers, such lands or buildings as are to be restored to the British subjects; orders, to that effect, will be sent out by the vessel above-mentioned. But, if no such orders should be received by you previous to the end of January, 1792, you are not to wait for them at the Sandwich islands, but to proceed, in such course as you may judge most expedient for the examination of the coast above-mentioned, comprized between latitude 60° north and 30° north.

In which examination the principal objects which you are to keep in view, are,

1st, The acquiring accurate information with respect to the nature and extent of any water-communication which may tend, in any considerable degree, to facilitate an intercourse, for the purposes of commerce, between the north-west coast, and the country upon the opposite side of the continent, which are inhabited or occupied by His Majesty's subjects.

[page] xix

2dly, The ascertaining, with as much precision as possible, then umber, extent, and situation of any settlements which have been made within the limits above-mentioned, by any European nation, and the time when such settlement was first made.

With respect to the first object, it would be of great importance if it should be found that, by means of any considerable inlets of the sea, or even of large rivers, communicating with the lakes in the interior of the continent, such an intercourse, as hath been already mentioned, could be established; it will therefore be necessary, for the purpose of ascertaining this point, that the survey should be so conducted, as not only to ascertain the general line of the sea coast, but also the direction and extent of all such considerable inlets, whether made by arms of the sea, or by the mouths of large rivers, as may be likely to lead to, or facilitate, such communication as is above described.

This being the principal object of the examination, so far as relates to that part of the subject, it necessarily follows, that a considerable degree of discretion must be left, and is therefore left to you, as to the means of executing the service which His Majesty has in view; but, as far as any general instructions can here be given on the subject, it seems desirable that, in order to avoid any unnecessary loss of time, you should not, and are therefore hereby required and directed not to pursue any inlet or river further than it shall appear to be navigable by vessels of such burthen as might safely navigate the pacific ocean: but, as the navigation of such inlets or rivers, to the extent here stated, may possibly require that you should proceed up them further than it might be safe for the sloop you command to go, you are, in such case,

c 2

[page] xx

to take the command of the armed tender in person, at all such times, and in such situations as you shall judge it necessary and expedient.

The particular course of the survey must depend on the different circumstances which may arise in the execution of a service of this nature; it is, however, proper that you should, and you are therefore hereby required and directed to pay a particular attention to the examination of the supposed straits of Juan de Fuca, said to be situated between 48° and 49° north latitude, and to lead to an opening through which the sloop Washington is reported to have passed in 1789, and to have come out again to the northward of Nootka. The discovery of a near communication between any such sea or strait, and any river running into, or from the lake of the woods, would be particularly useful.

If you should fail of discovering any such inlet, as is above-mentioned, to the southward of Cook's river, there is the greatest probability that it will be sound that the said river rises in some of the lakes already known to the Canadian traders, and to the servants of the Hudson's bay company; which point it would, in that case, be material to ascertain; and you are, therefore, to endeavour to ascertain accordingly, with as much precision as the circumstances existing at the time may allow: but the discovery of any similar communication more to the southward (should any such exist) would be much more advantageous for the purposes of commerce, and should, therefore, be preferably attended to, and you are, therefore, to give it a preferable attention accordingly.

With respect to the second object above-mentioned, it is probable that more particular instructions will be given you by the vessel to be

[page] xxi

sent to the Sandwich islands as aforesaid; but, if not, you are to be particularly careful in the execution of that, and every other part of the service with which you are entrusted, to avoid, with the utmost caution, the giving any ground of jealousy or complaint to the subjects of His Catholic Majesty; and, if you should fall in with any Spanish ships employed on any service similar to that which is hereby committed to you, you are to afford to the officer commanding such ships every possible degree of assistance and information, and to offer to him, that you, and he, should make to each other, reciprocally, a free and unreserved communication of all plans and charts of discoveries made by you and him in your respective voyages.

If, in the course of any part of this service, you, or the officers or the people under your command, should meet with the subjects or vessels of any other power or state, you and they are to treat them in the most friendly manner, and to be careful not to do any thing which may give occasion to any interruption of that peace which now happily subsists between His Majesty and all other powers.

The whole of the survey above-mentioned (if carried on with a view to the objects before stated, without too minute and particular an examination of the detail of the different parts of the coast laid down by it) may, as it is understood, probably be completed in the summers of 1792 and 1793; and, in the intermediate winter, it will be proper for you to repair, and you are hereby required and directed to repair accordingly, to the Sandwich islands; and, during your stay there, you are to endeavour to complete any part which may be unfinished of your examination of those islands.

[page] xxii

After the conclusion of your survey in the summer of 1793, you are, if the state and circumstances of the sloop and tender under your command will admit of it, to return to England by Cape Horn, (for which the season will then probably be favorable;) repairing to Spithead, where you are to remain until you receive further order; and sending to our secretary an account of your arrival and proceedings.

It seems doubtful, at present, how far the time may admit of your making any particular examination of the western coast of South America; but, if it should be practicable, you are to begin such examination from the south point of the island of Chiloe, which is in about 44° south latitude; and you are, in that case, to direct your attention to ascertaining what is the most southern Spanish settlement on that coast, and what harbours there are south of that settlement.

In the execution of every part of this service, it is very material that you should use, and you are therefore hereby strictly charged to use every possible care to avoid disputes with the natives of any of the parts where you may touch, and to be particularly attentive to endeavour, by a judicious distribution of the presents, (which have been put on board the sloop and tender under your command, by order of Lord Grenville) and by all other means, to conciliate their friendship and confidence. Given under our hands the 8th of March, 1791."

"To

George Vancouver, Esq. commander of His Majesty's sloop the Discovery,

At Falmouth.

By command of their Lordships.

Ph. Stephens."

"Chatham.

Rd. Hopkins.

Hood.

J. T. Townshend."

[page] xxiii

ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTIONS.

"By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great-Britain and Ireland, &c.

Lieutenant Hergeft, commanding the Dædalus transport, (by whom you will receive this) being directed to put himself under your command, and to follow your orders for his further proceedings; you are hereby required and directed, to take him, and the said transport, under your command accordingly; receiving from her the provisions and stores intended for the use of the sloop you command, and the Chatham armed tender, or such part thereof as the said ship and tender shall be able to flow.

And whereas you will receive herewith a duplicate of a letter from Count Florida Blanca, to the Spanish officer commanding at Nootka, (together with a translation thereof) signifying His Catholic Majesty's orders to cause such officer as may be appointed on the part of His Britannic Majesty, to be put in possession of the buildings, and districts, or parcels of lands therein described, which were occupied by His Majesty's subjects in the month of april, 1789, agreeable to the first article of the late convention, (a copy of which has been sent to you) and to deliver up any persons in the service of British subjects who may have been detained in those parts; in case, therefore, you shall receive this at Nootka, you are to deliver to the Spanish officer, commanding at that port, the above-mentioned letter from Count Florida Blanca, and to receive from him, conformably thereto, on the part of His Britannic Majesty, possession of the buildings and districts, and parcels

3

[page] xxiv

of land, of which His Majesty's subjects were possessed at the above-mentioned period.

In case, however, this shall not find you at Nootka, when Lieutenant Hergest arrives there, but be delivered to you at the Sandwich islands, or elsewhere, and the said lieutenant shall not have then carried into execution the service above-mentioned, (which in the event of his not falling in with you he is directed to do) you are immediately to proceed to Nootka, and to carry that service into execution as above directed, taking the said lieutenant and transport with you if you shall judge it necessary. But as they are intended afterwards to proceed to New South Wales, to be employed there, under the orders of Commodore Phillip, you are not to detain them at Nootka, the Sandwich islands, or elsewhere, longer than may be absolutely necessary, but to direct Lieutenant Hergest: to repair with the said transport to port Jackson, with such live stock, and other refreshments, as may be likely to be of use in the settlements there; and to touch at New Zealand in his way, from whence he is to use his best endeavours to take with him one or two flax-dressers, in order that the new settlers at port Jackson may, if possible, be properly instructed in the management of that valuable plant.

Previous, however, to your dispatching him to port Jackson, you are to consider whether, in case of your not being able to take on board the whole of the transport's cargo, any future supply of the articles of which it is composed, will be necessary to enable you to continue your intended survey; and, if so, you are to be careful to send notice thereof to Commodore Phillip, who will have directions, on the receipt of your application, to re-dispatch the transport, or to send such other ves-

[page] xxv

sel to you with the remainder of those supplies (as well as any others he may be able to furnish) to such rendezvous as you shall appoint.

And whereas Mr. Dundas has transmitted to us a sketch of the coast of North America, extending from Nootka down to the latitude of 47° 30", including the inlet or gulph of Juan de Fuca; and as from the declarations which have lately been made, there appears to be the strongest disposition, on the part of the Spanish court, that every assistance and information should be given to His Britannic Majesty's officers employed on that coast, with a view to the enabling them to carry their orders into execution; we send you the said sketch herewith, for your information and use, and do hereby require and direct you, to do every thing in your power to cultivate a good understanding with the officers and subjects of His Catholic Majesty who may fall in your way, in order that you may reap the good effects of this disposition of the Spanish court.

You are to take the utmost care in your power, on no account whatever, to touch at any port on the continent of America, to the southward of the latitude of 30° north, nor to the north of that part of South America, where, on your return home, you are directed to commence your intended survey; unless, from any accident, you shall find it absolutely necessary, for your immediate safety, to take shelter there: and, in case of such an event, to continue there no longer than your necessities require, in order that any complaint on the part of Spain on this point may, if possible, be prevented.

If, during your continuance on the American coast, you should meet with any of the Chinese who were employed by Mr. Meares and

VOL. I. d

[page] xxvi

his associates, or any of His Majesty's subjects. who may have been in captivity, you are to receive them on board the sloop you command, and to accommodate them in the best manner you may be able, until such time as opportunities may be found of sending them to the different places to which they may be desirous of being conveyed; victualling them during their continuance on board, in the same manner as the other persons on board the said sloop are victualled.

Given under our hands the 20th of august, 1791."

"To

George Vancouver, Esq. commander of His Majesty's sloop the Discovery.

By command of their Lordships.

Ph. Stephens."

"Chatham.

J. T. Townshend.

A. Gardner."

[page] xxvii

LETTER from COUNT FLORIDA BLANCA.

(Translated from the Spanish.)

"IN conformity to the first article of the convention of 28th october, 1790, between our court and that of London, (printed copies of which you will have already received, and of which another copy is here inclosed, in case the first have not come to hand) you will give directions that His Britannic Majesty's officer, who will deliver this letter, shall immediately be put into possession of the buildings and districts, or parcels of land, which were occupied by the subjects of that sovereign in april, 1789, as well in the port of Nootka, or of Saint Lawrence, as in the other, said to be called port Cox, and to be situated about sixteen leagues distant from the former to the southward; and that such parcels or districts of land, of which the English subjects were dispossessed, be restored to the said officer, in case the Spaniards should not have given them up.

You will also give orders, that if any individual in the service of British subjects, whether a Chinese, or of any other nation, should have been carried away and detained in those parts, such person shall be immediately delivered up to the above-mentioned officer.

I also communicate all this to the viceroy of New Spain by His Majesty's command, and by the same royal command I charge you with the most punctual and precise execution of this order.

May God preserve you many years.

(Signed)

Aranjuez, 12th may, 1791.

To the governor or commander of the port at Saint Lawrence".

"The Count Florida Blanca."

d 2

[page] xxviii

"By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great-Britain and Ireland, &c.

IN addition to former orders, you are hereby required and directed, by all proper conveyances, to send to our secretary, for our information, accounts of your proceedings, and copies of the surveys and drawings you shall have made; and, upon your arrival in England, you are immediately to repair to this office, in order to lay before us a full account of your proceedings in the whole course of your voyage; taking care, before you leave the sloop, to demand from the officers, and petty-officers, the log-books, journals, drawings, &c. they may have kept, and to seal them up for our inspection; and enjoining them, and the whole crew, not to divulge where they have been until they shall have permission so to do: and you are to direct the lieutenant commanding the Chatham armed tender to do the same, with respect to the officers, petty-officers, and crew of that tender.

Given under our hands the 10th of august, 1791."

"To

George Vancouver, Esq. commander of His Majesty's sloop the Discovery.

By command of their Lordships.

Ph. Stephens,"

"Chatham.

J. T. Townshend.

A. Gardner."

[page] xxix

Amongst other objects demanding my attention, whilst engaged in carrying these orders into execution, no opportunity was neglected to remove, as far as I was capable, all such errors as had crept into the science of navigation, and to establish, in their place, such facts as would tend to facilitate the grand object of finding the longitude at sea; which now seems to be brought nearly to a certainty, by pursuing the lunar method, assisted by a good chronometer. On this, as well as some other subjects, it is highly probable, that great prolixity and repetition will be found in the following pages; it will, however, readily appear to the candid perusers of this voyage, that, as the primary design of the undertaking was to obtain useful knowledge, so it became an indispensable duty, on my part, to use my utmost exertions and abilities in doing justice to the original intention, by detailing the information that arose in the execution of it, in a way calculated to instruct, even though it should fail to entertain. And when the writer alleges, that from the age of thirteen, his whole life, to the commencement of this expedition, (fifteen months only excepted) has been devoted to constant employment in His Majesty's naval service, he feels, and with all possible humility, that he has some claims to the indulgence of a generous public; who, under such circumstances, will not expect to find elegance of diction, purity of style, or unexceptionable grammatical accuracy: but will be satisfied with "a plain unvarnished" relation, given with a rigid attention to the truth of such transactions and circumstances as appeared to be worthy of recording by a naval officer, whose greatest pride is to deserve the appellation of being zealous in the service of his king and country.

[page break]

[page break]

Advertisement from the Editor.

AS a considerable delay has necessarily taken place in the publication of this work, in consequence of the decease of the late Captain Vancouver, it becomes of absolute necessity to give an accurate account of the state of the work at the period when his last fatal indisposition rendered him incapable of attending any more to business; left the melancholy event which has retarded its completion should tend to affect its authenticity in the public opinion.

The two first volumes, excepting the introduction, and as far as page 288 of the third and last volume, were printed; and Captain Vancouver had finished a laborious examination of the impression, and had compared it with the engraved charts and headlands of his discoveries, from the commencement of his survey in the year 1791, to the conclusion of it at the port of Valparaiso, on his return to England in the year 1795. He had also prepared the introduction, and a further part of the journal as far as page 408 of the last volume. The whole, therefore, of the important part of the work, which comprehends his geographical discoveries and improvements, is now presented to the public, exactly as it would have been had Captain Vancouver been still living. The notes which he had made on his journey from the port of Valparaiso to his arrival at St. Jago de Chili, the capital of that kingdom, were unfortunately lost; and I am indebted to Captain Puget for having assisted me with his observations on that occasion.

Ever since Captain Vancouver's last return to England, his health had been in a very debilitated state, and his constitution was evidently so much impaired by the arduous services in which, from his earliest youth, he had been constantly engaged*, that his friends dared to indulge but little hope that he would continue many years amongst them. Notwithstanding that it pleased the Divine Providence to spare his life until he had been able to revise and complete the account of the geographical part of his late Voyage of Discovery, a cir-

* The late Captain Vancouver was appointed to the Resolution by Captain Cook in the autumn of the year 1771, and on his return from that voyage round the world, he undertook to assist in the outfit and equipment of the Discovery, destined to accompany Captain Cook on his last voyage to the North pole, which was concluded in october, 1780. On the 9th of december following he was made a lieutenant into the Martin sloop; in this vessel he continued until he was removed into the Fame, one of Lord Rodney's fleet in the West-Indies, where he remained until the middle of the year 1783. In the year 1784 he was appointed to, and failed in the Europa to Jamaica, on which station he continued until her return to England in September 1789. On the 1 st of January, 1790, he was appointed to the Discovery, but soon afterwards was removed to the Courageux: here he remained until december, 1790, when he was made master and commander, and appointed to the Discovery. In august, 179, he: was, without solicitation, promoted to the rank of post captain, and was paid off on the conclusion of his last voyage in november, 1795. After this period he was constantly employed, until within a few weeks of his decease, in may, 1798, in preparing the following journal for publication.

2

[page break]

cumstance which must ever be regarded as most fortunate by all the friends of science, and especially by those professional persons who may hereafter be likely to follow him, through the intricate labyrinth which he has so minutely explored; yet it will ever be a consideration of much regret, that he did not survive to perfect the narrative of his labours. He had made many curious observations on the natural history of the several countries he had visited, and on the manners, customs, laws and religion, of the various people with whom he had met, or amongst whom he had occasionally resided; but had been induced to postpone these miscellaneous matters, left the regular diary of the voyage should be interrupted by the introduction of such desultory observations. These he had intended to present in the form of a supplementary or concluding chapter, but was prevented from so doing by the unfortunate event of his illness.

Most of the papers, which contain these interesting particulars, are too concise and too unconnected for me to attempt any arrangement of them, or to submit them to the reader without hazarding Captain Vancouver's judgment as an observer, or his reputation as a narrator, rigidly devoted to the truth. But as some of the notes, which he made upon the spot, are of too valuable a nature to be intirely lost, I shall venture to subjoin them to the History of the Voyage, as nearly as possible in his own words, without attempting any such arrangement of them, as might tend to diminish their authenticity, or bring into doubt that scrupulous veracity from which Captain Vancouver never departed.

The whole narrative of the Voyage of Discovery having been brought to its conclusion at Valparaiso, by Captain Vancouver himself, there only remains for me to add, that in preparing for the press the small remainder of his journal, comprehending the passage round Cape Horn to St. Helena, and from thence to England, I have strictly adhered to the rough documents before me; but as no new incidents occurred in this part of the voyage, and as the insertion of log-book minutes, over a space which is now so frequently traversed, cannot either be useful or entertaining, I have endeavoured to compress this portion of the journal into as few pages as possible.

In performing this painful task, I have had severe and ample cause to lament the melancholy office to which I have been compelled, by the loss of him whose early departure from this life has deprived His Majesty of an active and able officer, truth and science of a steady supporter, society of an uniformly valuable member, and in addition to the feelings of many who live to regret the loss of a sincere friend, I have to deplore that of a most affectionate brother.

JOHN VANCOUVER.

[page break]

CONTENTS

OF THE

FIRST VOLUME.

INTRODUCTION.

EXPLANATION OF THE PLATES.

BOOK THE FIRST.

TRANSACTIONS FROM THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXPEDITION, UNTIL OUR DEPARTURE FROM OTAHEITE.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Equipment of the DISCOVERY and the CHATHAM—Departure from Falmouth—Visit and transactions at Teneriffe—Occurrences and observations during the passage to the Cape of Good Hope—Transactions there, and departure thence, | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Departure from False Bay—Death of Neil Coil by the flux—Proceed towards the coast of New Holland—Discover King George the Third's Sound—Transactions there—Leave King George the Third's Sound—Departure from the south-west coast of New Holland, | 21 |

A

[page break]

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Remarks on the country and productions on part of the south-west coast of New Holland—Extraordinary devastation by fire—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Passage from the south-west coast of New Holland—Pass Van Dieman's land—Arrival in Dusky bay, New Zealand—Violent storms—Leave Dusky bay—A violent storm—Much water found in the ship—Part company with the Chatham—Discover the Snares—Proceed towards Otaheite—Arrive and join the Chatham there, | 58 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Mr. Broughton's narrative, from the time of his separation, to his being joined by the Discovery at Otaheite; with some account of Chatham Island, and other islands discovered on his passage, | 82 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Visit Otoo—Arrival of Pomurrey and Matooara Mahow—Arrival of Taow, Pomurrey's father—Interview between Taow and his sons—Submission of Taow to Otoo—Entertainments at the encampment—Visit of Poatatow—Death of Mahow—Excursion to Oparre, | 98 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Two natives punished for theft—Obsequies of Mahow—Several articles stolen—Measures for their recovery—Towereroo the Sandwich islander absconds—Brought back by Pomurrey—Sail for Malavai bay—Character of Pomurrey—His wives—Changes in the government of Otaheite—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 123 |

[page break]

BOOK THE SECOND.

VISIT THE SANDWICH ISLANDS; PROCEED TO SURVEY THE COAST OF NEW ALBION; PASS THROUGH AN INLAND NAVIGATION; TRANSACTIONS AT NOOTKA; ARRIVE AT PORT ST. FRANCISCO.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Passage to the Sandwich Islands—Arrive off Owhyhee—Visit from Tianna and other chiefs—Leave Towereroo at Owhyhee—Proceed to leeward—Anchor in Whyteete bay in Woahoo—Arrival at Attowai, | 151 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Transactions at Attowai—The prince and regent visit the ships—Fidelity of the natives—Observations on the changes in the several governments of the Sandwich islands—Commercial pursuits of the Americans, | 169 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Passage to the coast of America—Find the main-mast sprung—See the land of New Albion—Proceed along the coast—Fall in with an American vessel—Enter the supposed straits of De Fuca—Anchor there, | 191 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Proceed up the Straits—Anchor under New Dungeness—Remarks on the coast of New Albion—Arrive in port Discovery—Transactions there—Boat excursion—Quit port Discovery—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 220 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Description of port Discovery and the adjacent country—Its inhabitants—Method of depositing the dead—Conjectures relative to the apparent depopulation of the country, | 248 |

[page break]

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Enter Admiralty inlet—Anchor off Restoration point—Visit an Indian village—Account of several boat excursions—Proceed to another part of inlet—Take possession of the country, | 258 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Quit Admiralty inlet and proceed to the northward—Anchor in Birch bay—Prosecute the survey in the boats—Meet two Spanish vessels—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 290 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The vessels continue their route to the northward—Anchor in Desolation sound—The boats dispatched on surveying parties—Discover a passage to sea—Quit Desolation sound—Pass through Johnstone's straits, | 317 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Pass through Broughton's archipelago, to pursue the continental shore—The vessels get aground—Enter Fitzhugh's sound—Reasons for quitting the coast, and proceeding to Nootka, | 352 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Passage from Fitzhugh's sound to Nootka—Arrival in Friendly Cove—Transactions there, particularly those respecting the cession of Nootka—Remarks on the commerce of North-west America—Astronomical observations, | 382 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Depart from Nootka sound—Proceed to the southward along the coast—The Dædalus enters Gray's harbour—The Chatham enters Columbia river—Arrival of the Discovery at port St. Francisco, | 414 |

[page break]

A

LIST OF

THE PLATES

CONTAINED IN THE FIRST VOLUME.

WITH

DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER.

| Plate | To face Page | |

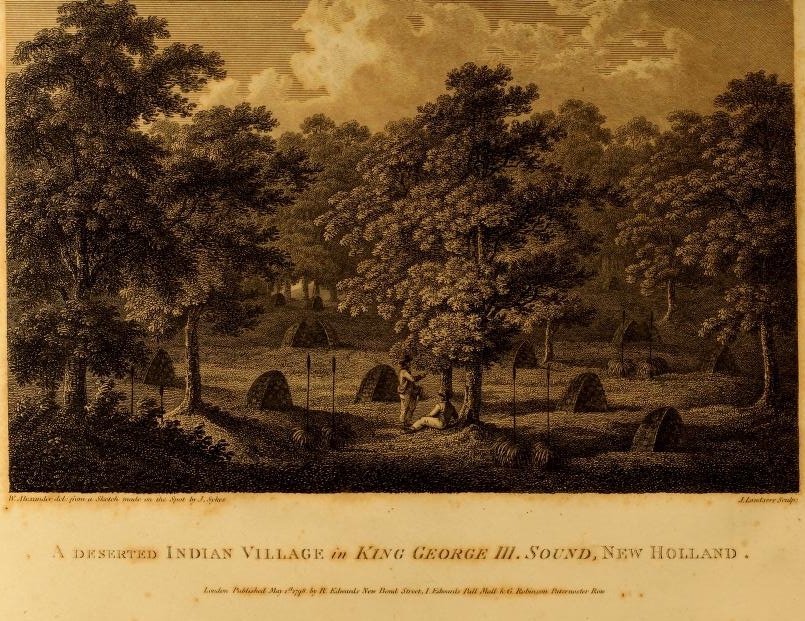

| I. | A Deserted Indian village in King George the Third's sound, New Holland, | 54 |

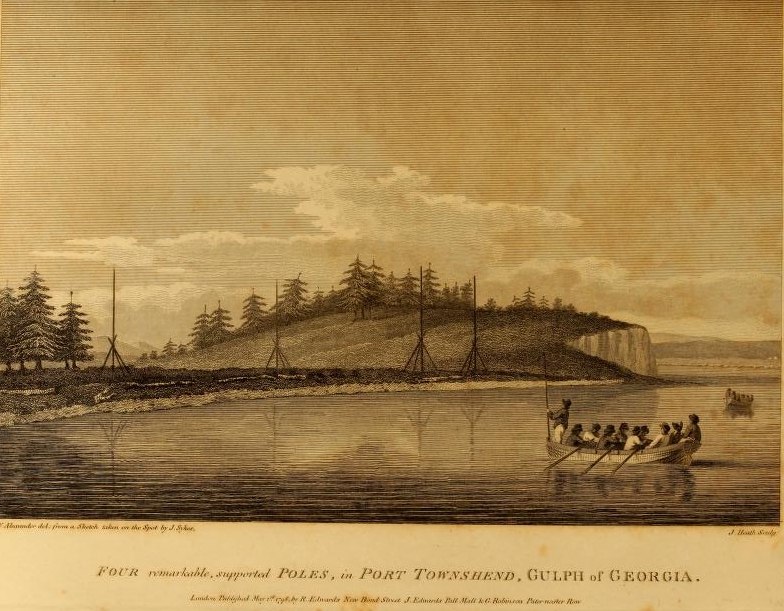

| II. | Four remarkable supported poles, in port Townshend, in the gulf of Georgia, | 234 |

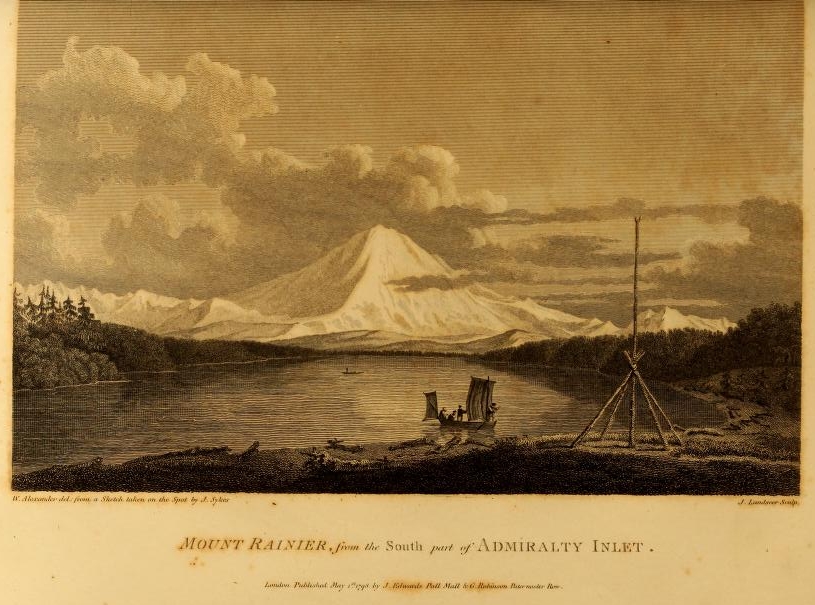

| III. | Mount Rainier, from the south part of Admiralty inlet, bearing S. 55 E. | 268 |

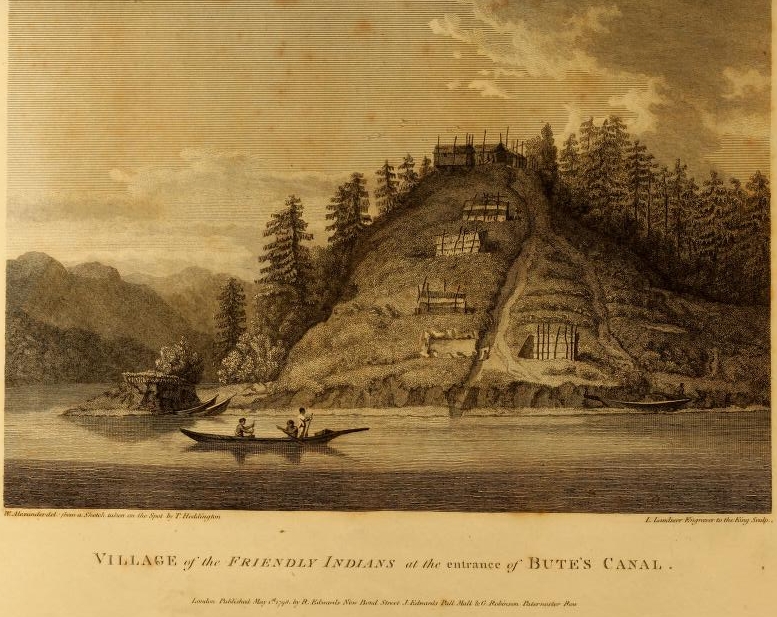

| IV. | Village of the friendly Indians, at the entrance of Bute's canal, | 326 |

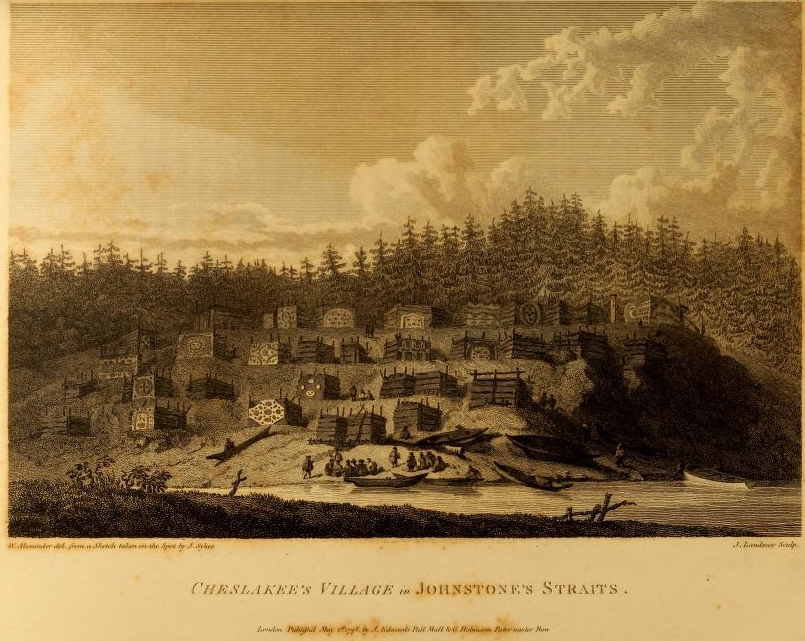

| V. | Cheslakees village, in Johnstone's straits, | 346 |

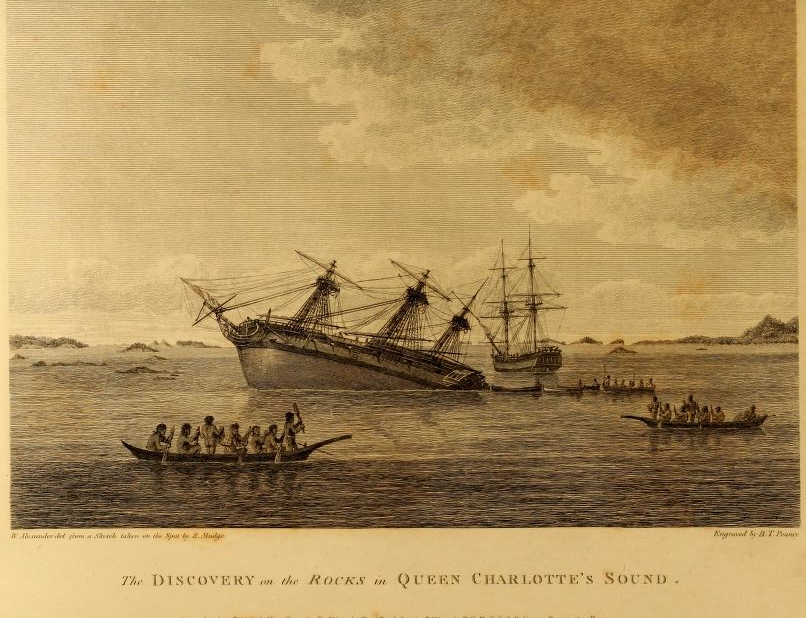

| VI. | The Discovery on the rocks in Queen Charlotte's sound, | 364 |

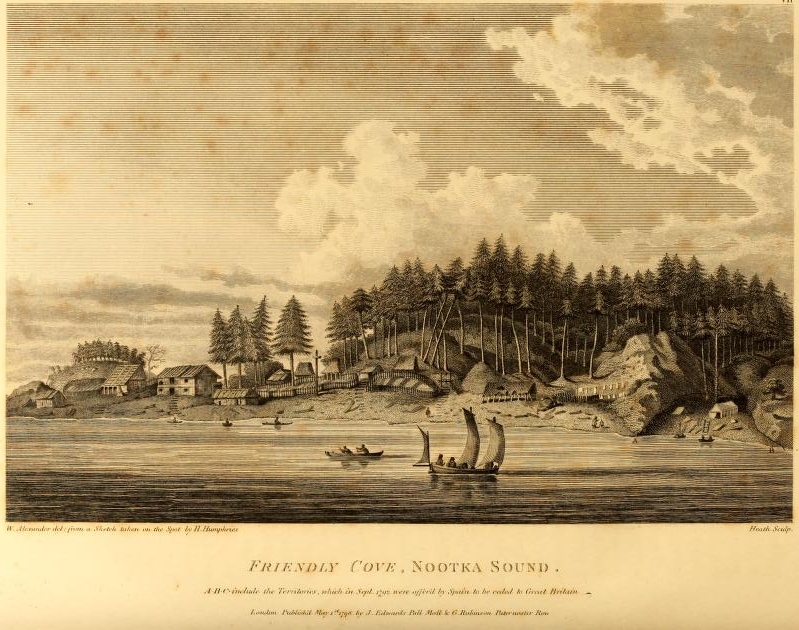

| VII. | Friendly cove, Nootka sound. The line A, B, C, containing the districts and territories offered on the part of His Catholic Majesty to be ceded to the crown of Great Britain. | 467 |

[page break]

A LIST OF

THE PLATES

CONTAINED IN THE FOLIO VOLUME.

| No. | |

| 1. | A SURVEY of part of the south west coast of New Holland, &c. |

| 2. | Views of parts of the south west coast of New Holland, with the islands of Oparre and the Snares. |

| 3. | Survey of part of the north west coast of America, from latitude 38° 15′ north, longitude 24° 0′ east, to latitude 45° 45′ north, longitude 232° east. |

| 4. | Views of parts of the coast of North West America. |

| 5. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 45° 30′ north, longitude 238° 30′ east, to latitude 52° 15′ north, longitude 230° 30′ east. |

| 6. | Views of parts of the coast of North West America. |

| 7. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 51° 45′ north, longitude 233° 30′ east, to latitude 57° 30′ north, longitude 225° 30′ east. |

| 8. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 38° 30′ north, longitude 237° 0′ east, to latitude 30° 0′ north, longitude 245° 0′ east. |

| 9. | Views of parts of the coast of North West America. |

| 10. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 56° 15′ north, longitude 204° 30′ east, to latitude 61° 30′ north, longitude 211° 30′ east. |

| 11. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 58° 30′ north, longitude 219° 30′ east, to latitude 62° 0′ north, longitude 210° 0′ east. |

| 12. | Survey of part of the coast of North West America, from latitude 56° 0′ north, longitude 227° 0′ east, to latitude 61° 0′ north, longitude 219° 0′ east. |

| 13. | Views of headlands and islands on the coasts of North West and South America. |

| 14. | A general chart of part of the coast of North West America. |

| 15. | A survey of the Sandwich islands. |

| 16. | Views of the Sandwich and other islands. |

[page 1]

A

VOYAGE

TO

THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN,

AND

ROUND THE WORLD.

BOOK THE FIRST.

Transactions from the commencement of the expedition, until our departure from Otaheite.

CHAPTER I.

Equipment of the DISCOVERY and the CHATHAM—Departure from Falmouth—Visit and transactions at Teneriffe—Occurrences and observations during the passage to the Cape of Good Hope—Transactions there and departure thence.

1790. December. Wednes.15. Thursday 16.

ON the 15th of December, 1790, I had the honor of receiving my commission as commander of His Majesty's sloop the Discovery, then lying at Deptford, where, the next morning, I joined her, and began entering men.

1791. January, Thursday 6.

Lieutenant William Robert Broughton having been selected as a proper officer to command the Chatham, he was accordingly appointed; but the repairs she demanded prevented her equipment keeping pace with that of the Discovery; which in most respects being completed by thursday the 6th of January, 1791, the fails were bent, and the ship got in readiness to

VOL. I. B

[page] 2

1791, January. Friday 7. Wednes. 26.

proceed down the river. With a favorable wind on the following day we failed, and anchored in Long Reach about five in the evening. Although this trial of the ship may appear very insignificant, yet as she had never been under fail, it was not made without some anxiety. The construction of her upper works, for the sake of adding to the comfort of the accommodations, differing materially from the general fashion, produced an unsightly appearance; and gave rise to various opinions unfavorable to her qualities as a sea-boat; for which reason it was natural to pay the minutest attention to her steering, and other properties when in motion; and we obtained in the course of this short expedition, the pleasing prospect of her proving handy, and in all other respects a very comfortable vessel. Various necessary occupations detained us in Long Reach until the 26th, when, having taken on board all our ordnance stores, and such things as were wanted from Deptford dock yard, we proceeded down the river on our way to Portsmouth. My orders for this purpose were accompanied by another, to receive on board and convey to his native country Towraro, an Indian, from one of the Sandwich Islands, who had been brought from thence by some of the north west American traders in july 1789. This man had lived, whilst in England, in great obscurity, and did hot seem in the least to have benefited by his residence in this country.

Sunday 30. February. Thursday 3. Saturday 5.

Unfavorable winds prevented our reaching the Downs until the 30th; where they still continued, and, being attended with very boisterous weather, detained us until the 3d of february; when, with a strong gale from the northward, we proceeded down channel. About noon we passed the South Foreland, and had the misfortune to lose John Brown, who fell overboard, and was drowned. He was one of the Carpenter's mates, an exceedingly good man, and very much regretted. About noon on the 5th we anchored at Spithead, where Rear-Admiral Goodall's flag was flying on board His Majesty's ship Vanguard, in company with twelve sail of the line, and several frigates.

Some defects in the ship's head were already evident, as the bumkins, and a considerable part of the head were now washed away. These repairs, with such other duties as were necessary, I gave orders to have executed; and my presence being required in London, I repaired

[page] 3

1791. February. Sunday 27.

thither; where I remained until the 27th, when I returned to Portsmouth, with orders to proceed to Falmouth.

On former voyages of this description, it had been customary to pay the officers and ship's company, the wages that had become due whilst they had been employed in the equipment of the vessels, which in general had occupied six months or upwards; enabling them by such means more effectually to provide themselves with those comforts which such long and remote services ever demand. But as a similar payment to the crews of the Discovery and Chatham, (whose complements were now complete) for the short time they had been in pay, would have been of little assistance; the Lords of the Admiralty, at my solicitation, had the goodness to grant them three months pay in advance; which was accordingly received free of all deductions.

March. Tuesday 1.

I have already mentioned that the Navy Board had supplied me with an assortment of mathematical instruments; and the Board of Longitude, in compliance with the wishes of the Admiralty, provided in addition two chronometers; one made by the late eminent Mr. Kendall, (the excellence of which had been manifested on board the Discovery during Captain Cook's last voyage, and which had lately been cleaned and put into order by its very worthy and ingenious maker, a short time before his decease;) the other lately made by Mr. Arnold. These had both been deposited at the observatory of the Portsmouth academy, for the purpose of finding their respective errors, and for ascertaining their rate of going. The former was delivered to me, with such observations as had been made to that effect: whence it appeared to be fast of mean time at Greenwich, on the 1st of March at noon, 1′ 30″ 18″, and to be gaining on mean time at the rate of 6″ 12″ per day. The latter was directed to be put on board the Chatham, which vessel had now arrived from the river.

Thursday 3. Friday 4. Saturday 12.

Having completely finished our business with the dock-yard on thursday evening, we dropped down to St. Helen's, and the next morning proceeded down channel, leaving the Chatham behind, not as yet quite ready to accompany us; in our way we stopped at Guernsey, and on the 12th arrived at Falmouth, where I was to wait the arrival of the Chatham, and to receive my final instructions for the prosecution of the

B 2

[page] 4

1791. March. Sunday 20. Thursday 31.

voyage. An Admiralty messenger presented me with the latter on sunday the 20th; but the Chatham did not arrive until the 31st, when Lieutenant Broughton, who had orders to put himself under my command, received such signals and instructions as were necessary on this occasion. He informed me, that they had experienced a very boisterous passage from Spithead, and that the Chatham had proved so very crank, as, in some instances, to occasion considerable alarm. The length of time I had already waited for her arrival rendered this intelligence very unpleasant; as, demanding immediate attention, it would cause further delay, which I much wished to avoid; especially as a favorable gale for clearing the channel now prevailed. The apprehension of further detention by contrary winds, should we lose the present opportunity by breaking up the Chatham's hold for the reception of more ballast, induced me to resort to another expedient, that of lending her all our shot, which when stowed amidships as low down as possible, and every weight removed from above, we flattered ourselves would be the means of affording a temporary relief to this inconvenience.

April. Friday 1. Saturday 2.

A gentle breeze from the N.E. at day dawn on friday the 1st: of april, enabled us to sail out of Carrack road, in company with the Chatham; and at midnight we took a long farewell of our native shores. The Lizard lights bore by compass N.N.W.½ w. about eight leagues distant; and the wind being in the western quarter, we stood to the southward. Towards the morning of the 2d, on the wind's shifting to the south, we stood to the westward, clear of the English channel; with minds, it may easily be conceived, not entirely free from serious and contemplative reflections. The remote and barbarous regions, which were now destined, for some years, to be our transitory places of abode, were not likely to afford us any means of communicating with our native soil, our families, our friends or favorites, whom we were now leaving far behind; and to augment these painful reflections, His Majesty's proclamation had arrived at Falmouth, the evening prior to our departure, offering bounties for manning the fleet; several sail of the line were put into commission, and flag officers appointed to different commands: these were circumstances similar to those under which, in august, 1776, I had failed

[page] 5

1701. April.

from England in the Discovery, commanded by Captain Clerke, on a voyage which in its object nearly resembled the expedition we were now about to undertake. This very unexpected armament could not be regarded without causing various opinions in those who, from day to day, would have opportunities of noticing the several measures inclining to war or peace; but to us, destined, as it were, to a long and remote exile, and precluded, for an indefinite period of time, from all chance of becoming acquainted with its result, it was the source of inexpressible solicitude, and our feelings on the occasion may be better conceived than described.

Sunday 3.

Having no particular route to the pacific ocean pointed out in my instructions, and being left at perfect liberty to pursue that which appeared the most eligible, I did not hesitate to prefer the passage by way of the cape of Good Hope, intending to visit the Madeiras, for the purpose of procuring wine and refreshments. Our course was accordingly so directed against winds very unfavorable to our wishes. At noon on the 3d we reached the latitude of 48° 48′ north, longitude, by the chronometer, 6° 55′ west; where the cloudy weather preventing our making the necessary observations on the sun eclipsed produced no small degree of concern; as with the late improvement of applying deep magnifying powers to the telescopes of sextants, the observations on solar eclipses are rendered very easy to be made at sea; and although we were not fortunate enough on this occasion to procure such, at the interesting periods of the eclipse, as would have put this improvement fully to the test, yet it was evident that these observations to persons not much accustomed to astronomical pursuits would be rendered plain and easy, by the reflected image of the sun being brought down to the horizon; so that the beginning and the end of the eclipse would be ascertained by the help of these deep magnifying telescopes with great precision; and probably it may not be unworthy the attention of the Board of Longitude to contrive, and cause such calculations to be published, as would tend to render these observations generally useful in the various parts of the globe, without the tedious process of calculating eclipses. The wind, continuing in the southern quarter, rendered our progress slow; the weather, however,

[page] 6

1791. April. Tuesday 12.

being clear, afforded us employment in taking some good lunar observations; which, reduced to the 12th at noon, gave the mean result of four sets, taken by me, 12° 24′ west longitude; four sets taken by Mr. Whidbey, 12° 30′; the chronometer at the same time shewing 12° 9′; and as I considered the latter to be nearest the truth, the lunar observations appeared to be 15′ to 21′ too far to the westward. The longitude, by dead reckoning, 13° 22′, and the latitude 44° 22′ north. The error in reckoning amounting almost to a degree, seemed most likely to have been occasioned by our not having made sufficient allowance for the variation of the compass on our first sailing, as, instead of allowing from 22° to 25°, which was what we esteemed the variation, our observations for ascertaining this fact, when the ship was sufficiently steady, shewed the variation to be 28° and 29° ½ westwardly. These opportunities, however, had not occurred so frequently as I could have wished, owing to a constant irregular swell that had accompanied us since leaving the land, and caused so much motion and pitching, that the whole head railings, bumkins, &c. were again washed away.

Saturday 16.

In làtitude 42° 34′ north, longitude 12° 31′ west, the variation of the compass, by the mean result of six sets of observations taken by three compasses differing from 25° 57′ to 27° 35′, was observed to be 26° 29′ westwardly. The current was found to set in a direction F.N.E.. at the rate of a quarter of a mile per hour. The whole of the day being perfectly calm, with remarkably fine weather, induced me to embrace the opportunity of unbending all our sails which wanted alteration, and to bend an entire new suit; these I caused to be soaked over board for some hours, that the sea water might dissolve the size used in making the canvass, and by that means act as a preventive against the mildew in hot rainy weather. This process might probably be sound useful in the operation of bleaching.

21.

On our departure from England, I did not intend using any antiseptic provisions, until the refreshments which we might be enabled to procure at the Madeiras should be exhausted: but light baffling winds, together with the crank situation and bad sailing of the Chatham, having so retarded our progress, that, by the 21st, we were advanced no further

[page] 7

1791. April.

than the latitude of 35° 7′ north, longitude 14° 40′ west: four krout and portable broth had, for some days, been served on board each of the vessels; the store rooms had been cleared, cleaned, and washed with vinegar, and the ship had been smoked with gunpowder mixed with vinegar. As I had ever considered fire the most likely and efficacious means to keep up a constant circulation of fresh and pure air throughout a ship; in the sore part of every day good fires were burning between decks, and in the well. Both decks were kept clean, and as dry as possible, and not withstanding the weather was hot, and the smoke and heat thence arising was considered as inconvenient and disagreeable, yet I was confident that a due attention to this particular, and not washing too frequently below, were indispensable precautions, and would be productive of the most salubrious and happy effects in preserving the health and lives of our people. These preventive measures becoming the standing orders of the Discovery, it will be unnecessary hereafter to repeat that they were regularly enforced, as they were observed throughout the voyage with the strictest attention. It may not, however, on this subject, be improper to remark that if instead of biscuit, seamen were provided with fresh soft bread, which can easily be made very good at sea, and a large proportion of wholesome water, where the nature of the services will admit of such a supply, they would add greatly to the preservation of that most valuable of all blessings, health.

Saturday 23. Sunday 24. Monday 25.