[page i]

A

VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY

TO THE

NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN,

AND

ROUND THE WORLD.

VOL. III.

[page ii]

[page iii]

A

VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY

TO THE

NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN,

AND

ROUND THE WORLD;

IN WHICH THE COAST OF NORTH-WEST AMERICA HAS BEEN CAREFULLY

EXAMINED AND ACCURATELY SURVEYED.

Undertaken by HIS MAJESTY'S Command,

PRINCIPALLY WITH A VIEW TO ASCERTAIN THE EXISTENCE OF ANY

NAVIGABLE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN THE

North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans;

AND PERFORMED IN THE YEARS

1790, 1791, 1792, 1793, 1794, and 1795,

IN THE

DISCOVERY SLOOP OF WAR, AND ARMED TENDER CHATHAM,

UNDER THE COMMAND OF

CAPTAIN GEORGE VANCOUVER.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR G. G. AND J. ROBINSON, PATER NOSTER ROW:

AND J. EDWARDS, PALL-MALL.

1798.

[page iv]

[page v]

CONTENTS

OF THE

THIRD VOLUME.

EXPLANATION OF THE PLATES.

BOOK THE FIFTH.

THIRD VISIT TO THE SANDWICH ISLANDS—CONCLUDE THE SURVEY OF THE COAST OF NORTH-WEST AMERICA.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Leave the coast of New Albion—Arrive off the east point of Owhyhee—Examine Whyeatea bay—Visited by Tamaahmaah—Proceed to Karakakooa bay—Transactions there—Departure of the Dædalus for New South Wales. | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Sequel of transactions at Karakakooa—Cession of the island of Owhyhee— Astronomical and nautical observations, | 21 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Quit Karakakooa—visit Tyahtatooa and Toeaigh bays—Some description of the anchorage at those places—Examine the northern sides of Mowee, Woahoo, and Attowai—Observations on the anchorage at Attowai and Onehow—Leave the Sandwich islands, | 59 |

VOL. III. A

[page vi]

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Quit the Sandwich islands—Part company with the Chatham—Indications of land—See Tseherikow island—Pass Trinity isles— Proceed along the coast—Enter and proceed up Cook's river, | 83 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Dangerous situation of the ship in consequence of ice—Examination of the upper part of Cook's river—Its final termination proving it to be only an extensive arm of the sea, it obtains the name of Cooks inlet—Joined by the Chatham—Mr. Puget's narrative during the separation of the two vessels—visited by Russians—Quit Cook's inlet—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 110 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Passage from Cook's inlet to Prince William's found—Meet a large fleet of canoes—Spring the bowsprit in a gale of wind—Carry away the foreyard —Arrive in port Chalmers—Survey of Prince William's found by the boats —A violent storm—Visited by a few Russians—Some account of their establishments in the found—Chatham dispatched to continue the survey of the coast eastward from cape Hinchinbrook—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 150 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Quit Prince William's found—Geographical and other observations respecting the adjacent country and its inhabitants—Proceed in the examination of the exterior coast—Pass port Mulgrave—Intelligence received of the survey having been completed to that station by the Chatham—Arrive in Cross found—Joined by the Chatham there, | 189 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mr. Puget's narrative of his transactions and survey of the coast, between Prince William's and Cross founds; during the Chatham's separation from the Discovery, | 216 |

2

[page vii]

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Transactions in Cross found—Proceed to sea—Account of a boat excursion— Description of port Althorp and Cross found—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 238 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Proceed to the southward along the exterior coast of King George the Third's archipelago—Arrive in port Conclusion—Transactions there—Two boat excursions—Complete the survey of the continental shores of North-West America—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 264 |

BOOK THE SIXTH.

PASSAGE TO THE SOUTHWARD ALONG THE WESTERN COAST OF AMERICA; DOUBLE CAPE HORN; TOUCH AT ST. HELENA; ARRIVE IN ENGLAND.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Depart, from port Conclusion—Arrive at Nootka—Transactions there— Visit Maquinna at Tahsheis—Astronomical observations for correcting the survey between cape Douglas and cape Decision, | 297 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Depart from Nootka found—Violent, storm—Arrive at Monterrey—Receive on board the deserters from the Chatham and Dædalus—Excursion into the country—Examine a very remarkable mountain—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 319 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Leave Monterrey—Some account of the three Marias islands—Proceed to the southward—Astronomical and nautical observations, | 339 |

[page viii]

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Visit the island of Cocos—Some description of that island—Astronomical and nautical observations there — Proceed to the Southward — Pass between Wenman's and Culpepper's islands—See the Gallipagos islands, and ascertain their situation. | 357 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

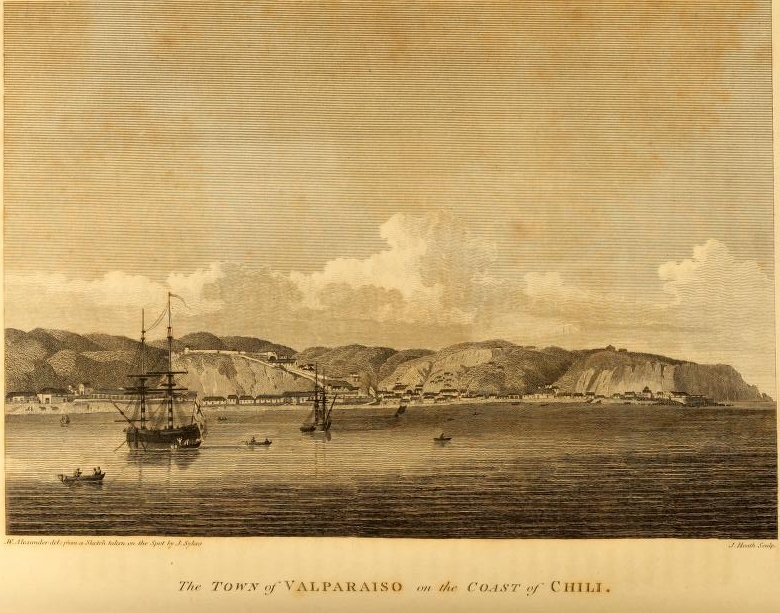

| Proceed to the Southward—The Discovery springs her main-mast—Scurvy makes its appearance—Pass the islands of Massafuero and Juan Fernandez—Arrive at Valparaiso—Visit St. Jago, the capital of Chili, | 389 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Quit Valparaiso—Proceed to the southward—Pass to the south of cape Horn —Useless search for isla Grande—Part company with the Chatham— Arrive at St. Helena—Join the Chatham there—Capture the Macassar Dutch East India Man—Astronomical and nautical observations—Leave St. Helena—Proceed to the northward—Discover a number of vessels under convoy of His Majesty's ship Sceptre—Join the convoy, and proceed with it to the Shannon—Discovery proceeds from thence to the river Thames, | 464 |

| Notes and Miscellaneous Observations, | 487 |

[page ix]

A

LIST OF

THE PLATES

CONTAINED IN THE THIRD VOLUME.

WITH

DIRECTION TO THE BINDER.

| Plate | To face Page | |

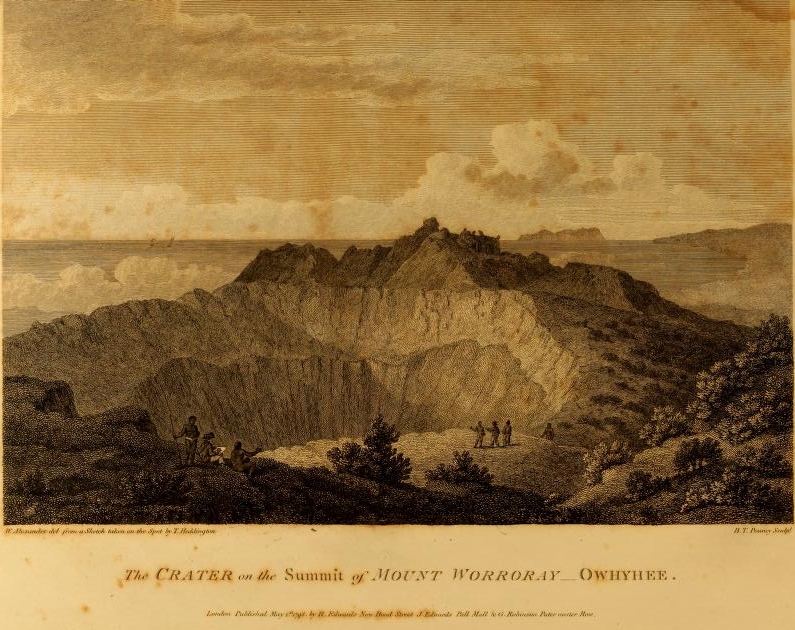

| I. | THE crater on the summit of mount Worroray, Owhyhee, with a distant view of the island of Mowee, | 14 |

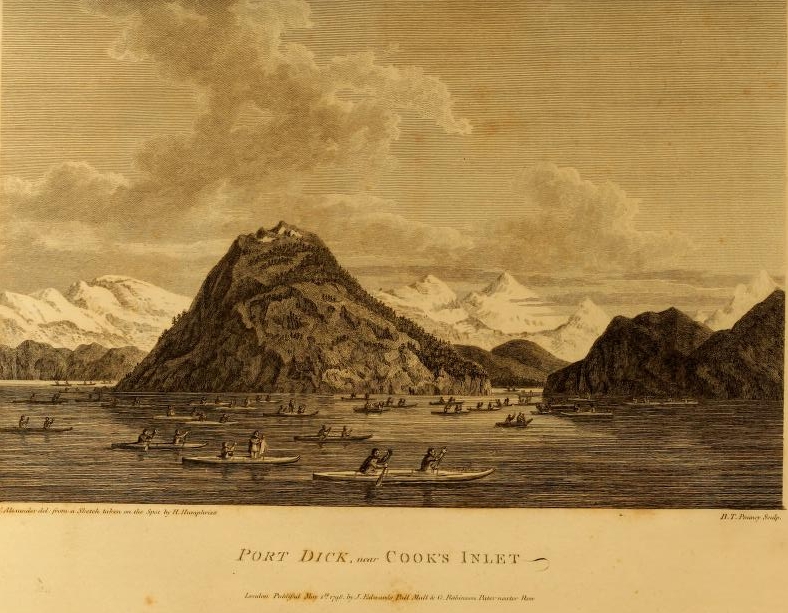

| II. | Port Dick, with a fleet of Indian canoes, | 150 |

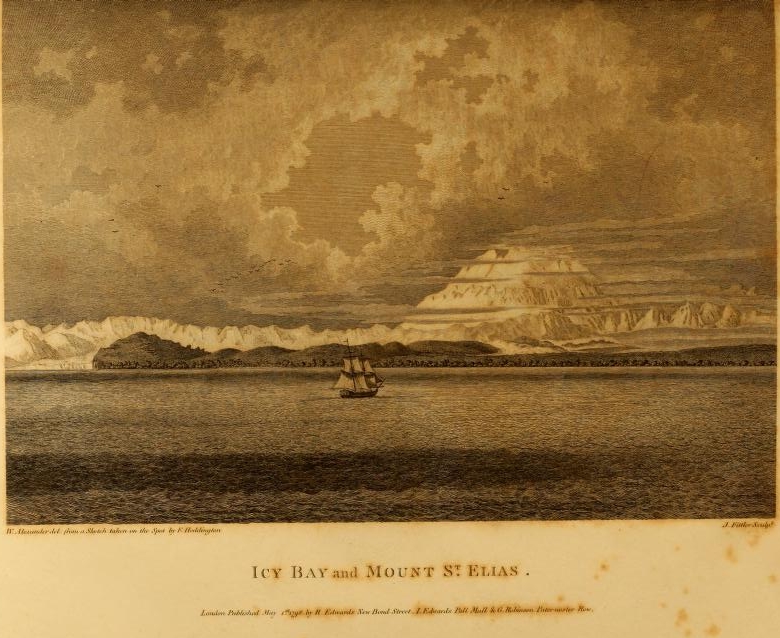

| III. | Mount St. Elias, bearing N. 50 W. and Icy bay, N. 20 W. five miles distant, | 204 |

| IV. | A remarkable mountain near the river of Monterrey, | 334 |

| V. | The town of Valparaiso on the coast of Chili, | 403 |

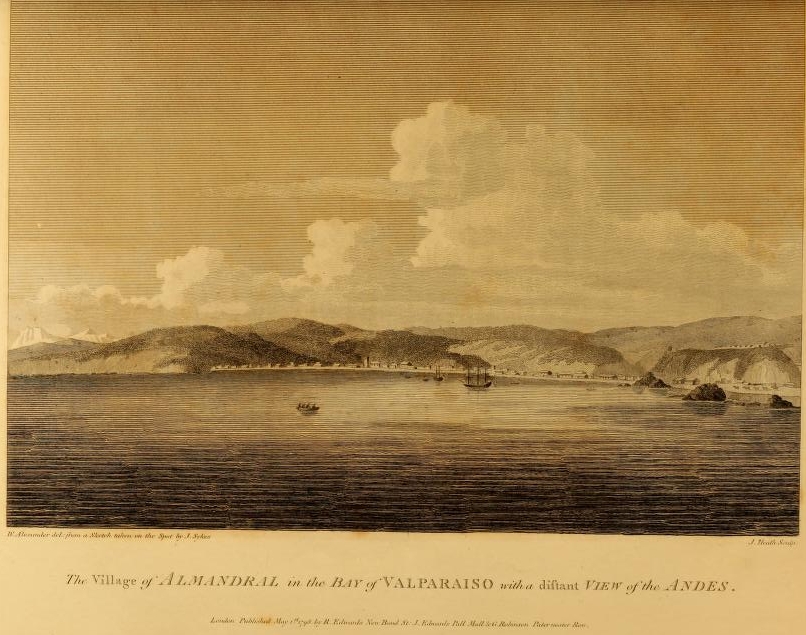

| VI. | The village of Almandrel, in the bay of Valparaiso, with a distant view of the Andes, | 412 |

[page x]

[page 1]

A

VOYAGE

TO

THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN

AND

ROUND THE WORLD.

BOOK THE FIFTH.

THIRD VISIT TO THE SANDWICH ISLANDS—CONCLUSION OF THE SURVEY OF THE COAST OF NORTH-WEST AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

Leave the coast of New Albion—Arrive off the east point of Owhyhee—Examine Whyeatea bay—Visited by Tamaahmaah—Proceed to Karakakooa bay —Transactions there—Departure of the Dædalus for New South Wales.

1793. December. Sunday 15.

OUR progress from the coast of New Albion, still attended with light variable winds, was so slow, that at noon of the 15th the shores were yet in sight, bearing from N. 17 E. to S. 69 E.; the former, being the nearest, was distant 7 leagues; the observed latitude was 30° 14', longitude 243° 57½.

Monday 16.

In the afternoon, the wind blew a moderate gale at W. N. W., which brought us by day-light the next morning within sight of the island of Guadaloupe. This island is composed of high naked rocky mountains; is about thirteen miles long, nearly in a north and south direction, with two rocky islets; one lying W. S. W., at the distance of half a league;

VOL. III. B

[page] 2

1793. December.

the other lying south, two miles from its south point, which is situated in latitude 28° 54', longitude 241° 38'. The wind at N.W. continued to blow a pleasant gale with fair weather until midnight; but at this time it veered round, and settled in the north-east trade. Our distance was now about 75 leagues from the coast, and it is probable the north-west winds do not extend far beyond that limit, as the wind that succeeded continued without calms, or other interruptions, between the N. E. and E. N. E., blowing a Ready, gentle, and pleasant gale.

Sunday 22.

Wednes. 25.

On the 22d, in latitude 23° 23', longitude 234° 37', the variation of the compass was 7° eastwardly; here we had thirty hours calm, after which we had a gentle breeze from the N. E.; this as we proceeded was attended first by cloudy and gloomy weather, and afterwards with rain, and sudden gusts or flurries of wind. On the 25th, a tropic bird was seen, and a common gull that appeared to be much fatigued, and inclined to alight on board.

Sunday 29.

This very unpleasant weather, similar to that which we had experienced in this neighbourhood about the conclusion of last january, still continued; and on the 29th, in latitude 19° 1', longitude 231° 58', the wind, after veering to the S. E., became light, and, like the weather, was very unsettled. We were now passing the spot assigned to the los Majos isles, at the distance of a few miles only to the southward of our former track; but we perceived no one circumstance that indicated the vicinity of land.

Tuesday 31.

1794. January. Friday 3.

Monday 6.

Tuesday 7.

On the 31st, the wind seemed to be fixed in the northern quarter, but the atmosphere was still very unpleasant, and the gloomy weather was accompanied by much rain. On the 3d of January, in latitude 18° 34', longitude 213° 32', a very heavy swell rolled from the N. W., and the wind in that direction was light, with alternate calms, attended by foggy or dark hazy weather until the 6th, when in latitude 19° 19', longitude 208° 48', we had a few hours of fair and pleasant weather; this was again succeeded by the same gloomy atmosphere that we had experienced during the greater part of this passage, and the wind continued to be very variable between the N. W. and S. S. W. In the afternoon of the following day the weather was more favorable, and the wind from the

[page] 3

1794. January.

Wednes. 9.

northward settled in the N. E; to this we spread all our canvass in the expectation of seeing the island of Owhyhee at day-light the next morning. The wind however slackened during the night, and the weather being dark and gloomy, it was not until about nine o'clock in the forenoon that Mowna-kaah was discovered shewing his hoary head above the clouds, bearing by compass W. ½ s.; but the haze and mist with which the district of Aheedo was inveloped, prevented our discerning the shores. The observed latitude at noon was 19° 52'; at this time the east end of Owhyhee bore by compass S. 52 W., at the distance of 10 leagues, by which it appeared, that Arnold's chronometer, No. 14. had erred in longitude since our departure from the coast of New Albion 27'; his No. 176, 21'; Kendall's, 52'; and the dead reckoning 3° 40'; all being to the eastward of the truth. This error has however been corrected, in assigning the several situations during this passage.

Tuesday 7

We stood for the land until sun-set, when being within 2 leagues of the shore, we employed the night in preserving our station off that part of the coast, where we expected to find the harbour or bay of Whyeatea: in quest of which I dispatched Mr. Whidbey in the cutter the next morning, attended by a boat from the Chatham, and another from the Dædalus, all well armed. The appearance of the shores did not seem much in favor of our finding a more eligible situation here than at Karakakooa, for accomplishing our several purposes; notwithstanding the representation that had been made to us of its being very commodious.

The boats had scarcely departed when some of the natives came off in their canoes, but owing to a very heavy swell from the northward, they could bring us but few refreshments. As soon as they understood who we were, they told us that Tamaahmaah, with several of the principal chiefs, were then on shore waiting in expectation of our arrival; and then immediately made the best of their way towards the shore, proclaiming our return to their country with shouts, apparently of great joy and gladness.

About ten in the forenoon we were honored with the presence of the king, with his usual confidence and cheerful disposition. It was impossible to mistake the happiness he expressed on seeing us again,

B 2

[page] 4

1794. January.

which seemed to be greatly increased by his meeting us at this, his most favorite part of the island; where he hoped we should be able to remain some time, to take the benefits arising from its fertility; which, from the appearance of the neighbouring shores, seemed to promise an abundant supply of the various refreshments these countries are known to produce.

Tamaahmaah had noticed the boats in their way to the shore, and trusted they would return with a favorable report; which he, as well as ourselves, anxiously waited for until five in the evening. Mr. Whidbey now informed me, that during the prevalence of the southerly winds, in the more advanced part of the spring season, Whyeatea might probably be found a tolerably secure and convenient place, as the land formed a deep bay, which was additionally sheltered by a reef lying off its south-east point, with foundings from 25 to 6 fathoms, clear sandy bottom; at least as far as his examination had extended. This had not been very minute, as the bay was intirely exposed to the northerly winds, which then blew very strong; and being attended with a heavy sea from that quarter, rendered any attempt to land from our boats impracticable. On this report I determined to proceed to Karakakooa, as that bay was indisputably at this time the most secure and convenient port for shipping of any in the Sandwich islands.

My intention was directly made known to Tamaahmaah, and I requested that he would give us the pleasure of his company thither; well knowing that his influence over the inferior chiefs and the people would be attended with the most desirable consequences, in preserving the harmony and good understanding that already so happily existed. He did not however seem much inclined to accept my invitation, or to give me a positive answer; but requested, that the vessels might remain some days in this neighbourhood, to avail ourselves of the ample supply of refreshments that might be procured here, before we proceeded to any other part of the island; adding, that he would remain with us to see this business properly performed.

I was by no means disposed to accede to the wishes of the king, nor was I satisfied with the arrangement he had proposed.

[page] 5

1794. January.

The vessels having been driven far to leeward on the morning of the 10th, and the wind then blowing strong from the northward, attended with a very heavy sea, I pointed out and explained to Tamaahmaah, the great improbability of our being able to comply with his desires, and the necessity of our proceeding without delay to some place of secure anchorage, for the purpose of refitting; renewing at the same time and in the strongest terms, my solicitations for his company. I did not sail to enforce how important his presence would necessarily be, not only to us for whom he had repeatedly expressed the greatest respect and friendship, but also to the welfare of his own subjects. He readily acknowledged the propriety of my observations, and how much he was inclined to adopt the measure I had proposed; but he now avowed that he could not accompany us, as the taboo appertaining to the festival of the new year demanded his continuance for a certain period, within the limits of the district in which these ceremonies had commenced. The time of interdiction was not yet expired, and it was not possible he could absent himself without the particular sanction of the priests. To obtain this indulgence, he considered his presence to be indispensibly necessary on more at the morai. Aware of the superior influence possessed by the priesthood, and of the strict adherence of all ranks to their superstitions, I suspected that if Tamaahmaah went on shore they would not allow him to return; for this reason I recommended, that one of the chiefs in his suite should repair thither, and make known the king's pleasure. But as this proposal did not seem to meet his ideas, or to be consonant to his wishes, I resolved not to detain him contrary to his own free will and inclination, or by any other means than those of persuasion. Yet as I considered his attendance to be an object of too much importance to be readily relinquished, I had recourse to a fort of artifice, that I had reason to believe would answer my purpose by its operation on his feelings. I desisted from all importunities, and attributed his declining my invitation to a coolness and a relaxation in the friendship he had formerly shewn, and pretended to entertain; and I stated, that I had no doubt of soon finding amongst the other islands some chief,

2

[page] 6

1794. January.

whose assistance, protection, and authority, would on all occasions be readily afforded.

Tamaahmaah had always been accustomed to attend our meals, and breakfast in particular he was extremely fond of partaking with us; but under the reproach he had just received, of a want of friendship, no solicitation could prevail on him to accept of any thing at table; he fat in a silent thoughtful mood, his sensibility was probed to the quick, and his generous heart, which continued to entertain the warmest friendship and regard, not only for me but for every one in our little community, yielded to our wishes; though at the risk of incurring the displeasure of the priests, by an unprecedented breach of their religious rites. At length he determined, that his half brother Crymamahoo should be sent to the priests, to communicate his intentions of accompanying us. On my saying, that this resolution made me very happy, and met my hearty concurrence, he replied, that I had treated him unkindly in suspecting that his friendship was abated, for that it remained unshaken, as his future conduct would demonstrate; but that he considered himself to be the last person in his dominions who ought to violate the established laws, and the regulations of the country which he governed.

Our little difference being thus amicably adjusted, he ate a hearty break-fast; and having given his brother the necessary instructions for governing this part of the island during his absence, in which business they were occupied an hour, Crymamahoo was dismissed, and directed to return with all convenient speed to communicate the answer of the priests.

Thoroughly convinced of the purity of Tamaahmaah's friendly intentions, I had receded from my former determination with respect to him, or any other of the chiefs, sleeping on board the ship. Our party now consisted of seven chiefs, three of whom were accompanied by their favorite females; but Tahow-man-noo, the king's consort, was not of the number. As she had never sailed in her attendance on him, the cause of her absence became a subject of inquiry, and I had the mortification of understanding that a separation had taken place, in consequence of its having

[page] 7

1794. January.

been reported, that too great an intimacy had subsisted between her and Tianna.

I understood from the king's attendants, that the infidelity of the queen was by no means certain; and as I well knew the reciprocal affection of this royal pair, and as she was then residing with her father at, or in the neighbourhood of Karakakooa, I thought it a charitable office, to make a tender of my endeavours for the purpose of bringing about a reconciliation. In reply to this obtrusion of my services, Tamaahmaah expressed his thanks; and assured me, that he should be always happy to receive any advice on state affairs, or any public matters, especially where peace or war might be concerned; but that such differences as might occur in, or respect, his domestic happiness, he considered to be totally out of my province. This rebuff I silently sustained; cherishing the hope that the period would arrive, when I should be able to prevail on him to entertain a different opinion.

The wind from the northward, attended with a very heavy sea, reduced us to our close-reefed topsails, and as we stood in shore in the afternoon a very strong current evidently pressed us to leeward. The appearance of the weather indicating no favorable or early change, there was little probability of our soon seeing Crymamahoo, or any of the inhabitants of Aheedoo; this induced the king to call his whole retinue together, both male and female, in order to take their advice as to his proceeding, without first receiving the religious assent he had dispatched Crymamahoo to obtain. The result of their deliberations was, a unanimous opinion that the priests would, on a certainty, accede to his wishes. This had been undoubtedly the previous sentiment of the king, or he would not have instructed his brother, in the manner he had done, how to conduct himself during his absence.

Although I earnestly wished to avoid being the cause of endangering his popularity, yet I was so anxiously desirous of his company, that I did not hesitate a moment in giving my hearty concurrence to this determination, in order that we might make the best of our way to Karakakooa.

[page] 8

1794. January. Saturday 11.

Our course was now directed round the east point of the island, along its south-east side; we made a tolerably good progress; and as we passed the district of Opoona, on the morning of the 11th, the weather being very clear and pleasant, we had a most excellent view of Mowna Roa's snowy summit, and the range of lower hills that extend towards the east end of Owhyhee. From the tops of these, about the middle of the descending ridge, several columns of smoke were seen to ascend, which Tamaahmaah, and the rest of our friends said, were occasioned by the subterranean fires that frequently broke out in violent eruptions, causing amongst the natives such a multiplicity of superstitious notions, as to give rise to a religious order of persons, who perform volcanic rites; consisting of various sacrifices of the different productions of the country, for the purpose of appealing the wrath of the enraged demon.

On approaching the shores of the district of Kaoo, we were met by several of the inhabitants, bringing in their canoes some refreshments and other productions of the country. Those who first approached us seemed to be much surprised, and many of them were not a little alarmed at seeing their king on board; inquiring with great earnestness, whether his being there, and having broken the taboo, was by his own choice, or by compulsion. On being assured by all present that Tamaahmaah, and the rest of the chiefs, were under no restraint whatever, but were accompanying us by their own free will, they became perfectly satisfied; and appeared to be equally so on understanding, that it was the king's pleasure, that the hogs and vegetables they had brought off should be delivered on board, without their receiving any equivalent in return; nor could we, without giving Tamaahmaah serious offence, have infringed this order, which seemed to be very cheerfully complied with on the part of his subjects; and, in the course of the forenoon, the vessels procured a sufficient supply for their present consumption. Whether the king accounted with these people afterwards for the value of their property thus disposed of, or not, I could not rightly understand; but from the great good humour with which they complied with the royal order, and from some conversation with one of the king's attendants, re -

[page] 9

1794. January.

specting the value of the refreshments so delivered, I had reason to believe that a compensation would be allowed to them.

Shortly after noon we were opposite the south point of the island; and, as a report had been circulated that close round, on its western side, good anchorage and excellent shelter had been found. (though it had escaped the notice of Captain Cook) Mr. Whidbey was dispatched in the cutter, in order to ascertain the truth of this assertion, which was soon proved to be void of foundation; for although a strong westerly gale prevented Mr.Whidbey from making a very minute examination, yet he clearly discovered that the shores were nearly straight, and exposed to a most tremendous surf, that broke with such fury as to render landing, if not impossible, highly dangerous, even to those of the inhabitants who are most expert in the management of their canoes.

The wind continued to blow very strong between west and N. W. until the morning of the 12th; when it became variable, and allowed us to make but a very flow progress towards Karakakooa. Tamaahmaah being very anxious that we should gain the place of our destination, went on shore for the purpose of placing lights to conduct us in the evening to our former anchorage; where, about ten the following night we anchored near an American brig, named the Lady Washington, commanded by Mr. John Kendrick.

As we worked into the bay many of the inhabitants were assembled on the shores, who announced their congratulations by shouts of joy, as, on our different tacks. we approached the shores of the neighbouring villages. At this late hour many of our former friends, particularly of the fair sex, lost no time in testifying the sincerity of the public sentiment in our favour. Young and Davis we had likewise the pleasure of finding in the exercise of those judicious principles they had so wisely adopted, and by their example and advice had so uniformly been carried into effect. The great propriety with which they had conducted themselves, had tended in a high degree to the comfort and happiness of these people, to the gratification of their own feelings, and to a pre-eminence in the good opinion of the king, that had intitled them to his warmest a affections. The same sort of esteem and regard, we understood, was shewn to

VOL. III. C

[page] 10

1794. January.

them, if not by all, at lead by the well-disposed inhabitants of the island.

The Discovery was secured nearly in her former station on the following morning; and the Chatham and Dædalus were disposed of in the most convenient manner for carrying into execution the respective services that each had to perform.

Mr. Kendrick had been here about six weeks, and it was with infinite pleasure we understood, that during that time he had not only been liberally supplied by the inhabitants of the island with its several productions, but that the same orderly, and civil behaviour had been observed towards him, which we had experienced on our former visit; and which we had every reason to expect would be continued, from the assurances we received from the chiefs, and from the acclamations of the people, which had resounded from all quarters on our arrival.

Tamaahmaah understanding that it would be necessary that we should land parts of the cargoes of all the vessels, appointed proper places for their reception; and knowing we had no more men than we could constantly employ for the speedy accomplishment of this business, he undertook to be answerable for the safety and security of every thing we might have occasion to put on shore, without our having any guard there for its protection. He also gave orders that his people should fill all our water casks; and as he considered that bartering with the several chiefs, and other individuals, for the valuable refreshments of the country, would not only be troublesome and unpleasant, but might give rise to disputes and misunderstandings between the parties; he desired we would daily, or as often as should suit our convenience, make our demands known to him, and he would take care that the three vessels were duly supplied with every necessary refreshment.

Wednes. 15.

This considerate and very friendly arrangement I was happy to concur in, and at day-light on wednesday morning three large canoes, laden with forty very fine hogs, and thirty small ones, with a proportionate quantity of vegetables, were, by the directions of the king, distributed amongst our three vessels.

[page] 11

1794. January.

On this occasion, it was impossible to avoid making a companion between our reception and treatment here, by these untaught children of nature, and the ceremonious conditional offers of accommodation we experienced at St. Francisco and Monterrey, from the educated civilized governor of New Albion and California.

After the large canoes had delivered their acceptable cargoes, they received and took to the shore the live cattle, which I had been more successful in bringing from New Albion than on the former occasion. These consisted of a young bull nearly full grown, two fine cows, and two very fine bull calves, all in high condition; as likewise five rams, and five ewe sheep. Two of each of these, with most of the black cattle, were given to the king; and as those I had brought last year had thrived exceedingly well; the sheep having bred, and one of the cows having brought forth a cow calf; I had little doubt, by this second importation, of having at length effected the very desirable object of establishing in this island a breed of those valuable animals.

I learned from Tamaahmaah, that he had issued the strictest orders so to regulate the conduct and behaviour of his people towards us, as he trusted would be the means of insuring a continuance of the harmony that had so happily subsisted on our former visits to his dominions; and he added, that he had many enemies even amongst the chiefs of Owhyhee, who were not unlikely to use their endeavours for the purpose of frustrating his good intentions, and that it was very important that the designs of such ill-disposed persons should be watchfully guarded against. I thanked Tamaahmaah for his vigilant attention to preserve our tranquillity and comfort, and informed him, that I had also issued orders and directions similar to those given on my former visit. These having the same tendency, and operating to the same end, with those enjoined by himself, would, I hoped, be effectual in affording us the recreation and enjoyment of the country, and in securing to us a continuation of the then subsisting friendly intercourse.

These necessary precautions being taken on both sides, we immediately began upon the various services that demanded our attention. Those appertaining to the reception of the provisions and stores from

C 2

[page] 12

1794. January.

the Dædalus, were the primary objects of our consideration; and by the orderly and docile behaviour of all classes of the inhabitants, this business was carried into execution with a degree of facility, and confidence in our perfect security, equal to the accommodation that could possibly have been obtained in any port of Europe.

There were not at this time many of the principal chiefs in our neighbourhood. Our former friend Kahowmotoo paid us an early visit, with a present of twenty large hogs, and a proportionable quantity of vegetables. He was not, however, in his usually cheerful good spirits, but was much depressed, in consequence of a violent indisposition under which his favorite son Whokaa laboured, from a wound he had received in the exercise of throwing the spear with a man of mean rank. After a long contention for superiority, their play, it seemed, terminated in earned, and the young chief received his adversary's spear, which was barbed, in the throat. Much difficulty had attended its being taken out, which had occasioned a wound that had battled all their art to cure, and had reduced him to the last stage of his existence. His antagonist was soon seized, and the next day his eyes were pulled out, and, after remaining in that deplorable state two days, he was executed, by being strangled with a rope.

Thursday 16.

As some of the gentlemen intended to accompany Mr. Menzies on an excursion into the interior part of the country, they were, agreeably to our plan of regulations, attended by a chief of the village of Kakooa with several of the king's people, who had directions to supply all their wants, and to afford them every assistance and service that they might require.

Tuesday 21.

The harmony that had attended the execution of all our employments had so facilitated the equipment of the vessels, that, by the following tuesday, the business in the Discovery's hold was in that state of forwardness as to permit our attending to other objects. The astronomical department claimed my first thoughts; and being of such material importance, I was anxious to lose no time in sending the tents, observatory, and instruments, on shore, now that a party could be afforded for their protection. On this occasion I was surprized to find the king make some

[page] 13

1794. January.

Wednes. 22.

objection; to their being erected in their former situation, near the morai; giving us as a reason, that he could not sanction our inhabiting the tabooed lands, without previously obtaining the permission of an old woman, who, we understand. was the daughter of the venerable Kaoo, and wife to the treacherous Koah. Being totally unacquainted before, that the women ever possessed the least authority over their consecrated places, or religious ceremonies, this circumstance much surprized me, especially as the king seemed to be apprehensive of receiving a refusal from this old lady, and which, after waiting on shore for some time, proved to be the case. Tamaahmaah observing my disappointment, intreated me to fix upon some other part of the bay; but as it was easily made obvious to his understanding that no other spot would be equally convenient, he instantly assembled some of the principal priests of the morai, and after having a serious conference with them, he acquainted me, that we were at liberty to occupy the consecrated ground as formerly, which we accordingly took possession of the next morning.

Mr. Whidbey, who had charge of the encampment, attended it on shore under a guard of fix marines; these were sent, however, more for the sake of form than for necessity; as Tamaahmaah had appointed one of his half brothers, Trywhookee, a chief of some consequence, together with several of the priests, to protect, and render the party on shore every service their situation might demand. To this spot, as on our former visit, none were admitted but those of the society of priests, the principal chiefs, and some few of their male attendants; no women, on any pretence whatever, being ever admitted within the sacred limits of the morai.

The unfortunate son of Kahowmotoo had been brought by his father from one of his principal places of residence, about six miles north of the bay where the unfortunate accident happened, to the village of Kowrowa, in order to benefit by such medical or other assistance as we might be able to afford, but without effect; for in the afternoon he breathed his last.

The periodical taboo, that ought to have commenced the following evening, was, on this occasion, suspended, to manifest that they were

*Vide Captain King's account of Cook's death.

[page] 14

1794. January. Thursday 23.

offended with their deity for the death of this young chief; whose loss seemed to be greatly deplored by all the family, but most particularly so by Kahowmotoo; of whom I took a proper opportunity of inquiring when the corpse would be interred, and if there would be any objection to my attending the funeral solemnities. To this he made answer, that the burial would take place the day following, and that he would come on board at any convenient hour, and accompany me on shore for that purpose.

Friday 24.

I remained perfectly satisfied with the promise made by Kahowmotoo; and was the next morning greatly disappointed on his informing me, that Kavaheero, the chief of the village at which his son had died, had, in the course of the night, unknown to him or any of his family, caused the body of the young chief to be interred in one of the sepulchral holes of the steep hill, forming the north side of the bay. This circumstance could not but be received as an additional proof of their aversion to our becoming acquainted with their religious rites, and their determination to prevent our attendance on any of their sacred formalities.

Saturday 25.

The party accompanying Mr. Menzies returned with him on saturday, after having had a very pleasant excursion, though it had been somewhat fatiguing in consequence of the badness of the paths in the interior country, where in many places the ground broke in under their feet. Their object had been to gain the summit of Mowna Roa, which they had not been able to effect in the direction they had attempted it; but they had reached the top of another mountain, which though not so lofty as Mowna-rowna, or Mowna-kaah, is yet very conspicuous, and is called by the natives Worroray. This mountain rises from the western extremity of the island, and on its summit was a volcanic crater that readily accounted for the formation of that part of the country over which they had found it so dangerous to travel. The good offices of their Indian guide and servants received a liberal reward, to which they were highly intitled by their friendly and orderly behaviour.

The whole of the retinue that had attended Tamaahmaah from Aheedoo, with the addition of some new visitors, lived intirely on board the ship, and felt themselves not only perfectly at home, but very advan-

[page break]

The CRATER on the SUMMIT of MOUNT WORRORAY OWHYHEE.

[page break]

[page] 15

1794. January.

tageously situated, in being enabled to purchase such commodities of their own produce or manufacture which were brought to us for sale, as attracted their attention, with the presents which they received from time to time. Notwithstanding this indulgence, which I thought could not have sailed to keep them honest, such is their irresistible propensity to thieving, that five of my table knives were missing. The whole party stoutly denied having any knowledge of the theft; but as it was evident the knives were stolen by some of them, I ordered them all, except the king, instantly to quit the ship, and gave positive directions that no one of them should be re-admitted. Beside this, I deemed it expedient to make a point with Tamaahmaah that the knives should be restored. He saw the propriety of my insisting on this demand, and before noon three of the knives were returned.

Sunday 26.

The taboo, which had been postponed in consequence of Whokaa's death, was observed this evening, though not without holding out a sentiment of resentment to their deity for having suffered him to die; for instead of its continuing the usual time of two nights and one whole day, this was only to be in force from sun-set to the rising of the sun the following morning; which the king having observed, returned to us as soon as the ceremonies were finished.

Being very much displeased with the ungrateful behaviour of his attendants, I demanded of Tamaahmaah, in a serious tone, the two knives that had not yet been restored. I expatiated on the disgrace that attached to every individual of the whole party, and the consequence of the example to all the subordinate classes of his people. He appeared to be much chagrined, and to suffer a high degree of mortification at the very unhandsome manner in which I had been treated; this was still further increased, by one of his most particular favorites having been charged, and on just grounds, as one of the delinquents.

About noon he went on shore, in a very sullen humour, and did not return until I had sent for him in the evening, which summons he very readily obeyed; and soon another knife was returned, which he declared was the only one he had been able to find, and that if any more were yet missing, they must have been lost by some other means. The

1

[page] 16

1794. January.

truth, as we afterwards understood, was that the knife had been given, by the purloiner, to a person of much consequence, over whom Tamaahmaah did not with to enforce his authority.

These knives had not been stolen, as might be naturally imagined, for their value as iron instruments, but for the sake of their ivory handles. These were intended to have been converted into certain neck ornaments, that are considered as sacred and invaluable. The bones of some fish are, with great labour, appropriated to this purpose; but the colour and texture of the ivory surpassing, in so eminent a degree, the other ordinary material, the temptation was too great to be resisted.

Under the particular circumstances, which we understood attended the missing knife, I readily put up with its loss; because, in so doing, I was relieved of the inconvenience which a number of noisy and troublesome visitors had occasioned. These, however, paid clearly for their dishonesty, in being abridged the great source of wealth which they had enjoyed on board, and which had enabled them to procure many valuable commodities of their own country, at the expence of asking only for such of our European articles as the seller demanded.

Monday 27.

Our business in the hold being finished, the seamen were employed in a thorough examination of all the rigging; and although this was the first time, with respect to the lower rigging, that an examination had taken place since the ship was commissioned, we had the satisfaction of finding it in much better condition than, from the trials it had endured, we could reasonably have expected.

Tuesday 28.

Since the death of Whokaa, Kahowmotoo had not paid the least attention to the Owhyhean taboos; but as similar interdictions were to take place on the 28th, on the island of Mowee, these he punctually observed: and on the following day Tamaahmaah also was again thus religiously engaged; but as there were no prayers on this day, the people at large seemed to be under little restriction.

Thursday20.

On thursday we were favored with the company of Terree-my-tee, Crymamahoo, Tianna, and some other chiefs, from the distant parts of the island.

Their arrival had been in consequence of a summons from the king, who had called the grand council of the island, on the subject of its ces-

[page] 17

1794. January.

sion to the crown of Great Britain, which was unanimously desired. This important business, however, for which their attendance had been demanded, appeared to be of secondary consideration to all of them; and the happiness they expressed on our return, together with their cordial behaviour, proved, beyond dispute, that our arrival at Owhyhee was the object most conducive to the pleasure of their journey. Even Tianna conducted himself with an unusual degree of good humour; but as neither he, nor his brother Nomatahah, from their turbulent, treacherous, and ungrateful dispositions, were favorites amongst us, his humility, on this occasion, obtained him only the reputation of possessing a very superior degree of art and duplicity. But as the principal object I had in view was to preserve the good understanding that had been established between us, and, if possible, to secure it on a permanent basis, for the benefit of those who might succeed us at these islands, I waved all retrospective considerations, and treated Tianna with every mark of attention, to which his rank, as one of the six provincial chiefs, intitled him, and with which, on all occasions, he appeared to be highly gratified.

These chiefs brought intelligence, that a quantity of timber which had been sent for at my request, was on its way hither; it had been cut down under the directions of an Englishman, whose name was Boid, formerly the mate of the sloop Washington, but who had relinquished that way of life, and had entered into the service of Tamaahmaah. He appeared in the character of a shipwright, and had undertaken to build, with these materials, a vessel for the king, after the European fashion; but not having been regularly brought up to this business, both himself and his comrades, Young and Davis, were fearful of encountering too many difficulties; especially as they were all much at a loss in the first outset, that of laying down the keel, and properly letting up the frame; but could they be rightly assisted in these primary operations, Boid (who had the appearance of being very industrious and ingenious) seemed to entertain no doubt of accomplishing the rest of their undertaking.

VOL. III. D

[page] 18

1793. February.

This afforded me an opportunity of conferring on Tamaahmaah a favor that he valued far beyond every other obligation in my power to bestow, by permitting our carpenters to begin the vessel; from whose example, and the assistance of these three engineers, he was in hopes that his people would hereafter be able to build boats and small vessels for themselves.

Saturday 1.

An ambition so truly laudable, in one to whose hospitality and friendship we had been so highly indebted, and whose good offices were daily administering in some way or other to our comfort, it was a grateful task to cherish and promote; and as our carpenters had finished the re-equipment of the vessels, on the 1st of february they laid down the keel, and began to prepare the frame work of His Owhyhean Majesty's first man of war. The length of its keel was thirty-six feet, the extreme breadth of the vessel nine feet and a quarter, and the depth of her hold about five feet; her name was to be The Britannia, and was intended as a protection to the royal person of Tamaahmaah; and I believe few circumstances in his life ever afforded him more solid satisfaction.

It was not very likely that our stay would be so protracted, as to allow our artificers to finish the work they had begun, nor did the king seem to expect I should defer my departure hence for that purpose; but confided in the assertion of Boid, that, with the assistance we should afford him, he would be able to complete the vessel.

In the evening a very strict taboo commenced; it was called The taboo of the Hahcoo, and appertains to the taking of two particular kinds of fish; one of which, amongst these islanders, bears that name; these are not lawful to be taken at the same time, for during those months that the one is permitted to be caught the other is prohibited. They are very punctual in the observance of this anniversary, which is, exclusively of their days, months, and year, an additional means of dividing their time, or, perhaps, properly speaking, their seasons. The continuance of this interdiction ought to have extended to ten days; but as it is the prerogative of the king to shorten its duration in any one particular district, he directed on our account that in the district of

[page] 19

1794. February.

Akona it should cease with the men on the morning of the 4th, and with the women on the day following.

Thursday 6.

Most of our essential business was nearly brought to a conclusion by the 6th, and our remaining here for the accomplishment of what yet remained to be done, was no longer an object of absolute necessity; yet I was induced to prolong our stay in this comfortable situation for two reasons; first, because the plan of operations I intended to pursue, in the prosecution of the remaining part of our survey on the coast of North-West America, did not require our repairing immediately to the northward; and secondly, because our former experience amongst the other islands had proved, that there was no prospect of obtaining that abundant. supply of refreshments which Owhyhee afforded, even at the expence of arms and ammunition; articles that humanity and policy had uniformly dictated me to with-hold, not only from these islanders, but from every tribe of Indians with whom we had any concern.

The completion of our survey of these islands required still the examination of the north sides of Mowee, Woahoo, and Attowai; and reserving sufficient time for that purpose, I determined to spend here the rest I had to spare, before we should proceed to the American coast. This afforded an opportunity to Mr. Menzies and Mr. Baker, accompanied by some others of the gentlemen, to make another excursion into the country for the purpose of ascending Mowna Roa, which now appeared to be a task that was likely to be accomplished; as we had understood from the natives, that the attempt would be less difficult from the south point of the island than from any other direction. For this purpose the party, furnished by Tamaahmaah with a large double canoe, and a sufficient number of people, under the orders of a Ready careful chief, sat out, in the confidence of receiving every assistance and attention that could be necessary to render the expedition interesting and agreeable.

The Dædalus being, in all respects, ready to depart for port Jackson, Lieutenant Hanson on the 8th received his orders from me for that purpose, together with a copy of our survey of the coast of New Albion,

D 2

[page] 20

1794. February.

southward from Monterrey; and such dispatches for government as I thought proper to transmit by this conveyance, to the care of the commanding officer at that port.

Some plants of the bread fruit were also put on board, in order that Mr. Hanson, in his way to New South Wales, should endeavour, in the event of his visiting Norfolk island, to introduce there that most valuable production of the vegetable kingdom.

[page] 21

CHAPTER II.

Sequel of transactions at Karakakooa—Cession of the island of Owhyhee— Astronomical and nautical observations.

1793. February.

Sunday 9.

WHILST the re-equipment of the vessels was going forward in this hospitable port, I had remained chiefly on board; but having now little to attend to there, on sunday I took up my abode at the encampment, highly to the satisfaction of the king; who, for the purpose of obtaining such knowledge as might hereafter enable him to follow the example of our artificers, had paid the strictest attention to all their proceedings in the construction of the Britannia. This had latterly so much engaged him, that we had been favored with little of his company on board the vessels; yet I had the satisfaction of reflecting, that his having been occasionally with us, and constantly in our neighbourhood, had been the means of restraining the ill-disposed, and of encouraging the very orderly and friendly behaviour that we had experienced from the inhabitants without the least interruption whatever. An uniform zeal directed the conduct of every Indian, in the performance of such offices of kindness as we appeared to stand in need of, or which they considered would be acceptable; these were executed with such promptitude and cheerfulness, as to indicate that they considered their labours amply repaid by our acceptance of their services; yet I trust they were better rewarded than if they had acted on more interested principles.

Our reception and entertainment here by these unlettered people, who in general have been distinguished by the appellation of savages, was such as, I believe, is seldom equalled by the most civilized nations of

[page] 22

1794. February.

Europe, and made me no longer regret the inhospitality we had met with at St. Francisco and Monterrey. The temporary use that we wished to make of a few yards of the American shore, for our own convenience and for the promotion of science, was not here, as in New Albion, granted with restrictions that precluded our acceptance of the favor we solicited; on the contrary, immediately on our arrival an ample space, protected by the most sacred laws of the country, was appropriated to our service; whilst those of our small community whose inclinations led them into the interior parts of the island, either for recreation, or to examine its natural productions, found their desires met and encouraged by the kind assistance of Tamaahmaah, and their several pursuits rendered highly entertaining and agreeable, by the friendship and hospitality which was shewn them at every house in the course of their excursions.

A conduct so disinterestedly noble, and uniformly observed by so untutored a race, will not sail to excite a certain degree of regret, that the first social principles, teaching mutual support and universal benevolence, should so frequently, amongst civilized people, be sacrificed to suspicion, jealousy, and distrust. These sentiments had undoubtedly very strongly operated against us on a recent occasion; but had the gentleman, to whose assistance we appealed, but rightly considered our peculiar situation, he must have been convinced there could not have existed a necessity for the unkind treatment he was pleased to offer to our little squadron; and he would have spared me at this moment the unwelcome talk of making this comparison, by which the world will perceive what I must have felt upon that occasion.

Wednes. 12.

A very strict taboo was on this day to be enforced over all the island, and required that the respective chiefs should retire to their own estates, for the purpose of rigidly observing the attendant solemnities; which were to continue two nights and one day. In the event of the omen's proving favorable, the chiefs would be permitted to eat of such pork as they might think proper to consecrate on this occasion; and high poory, that is, grand prayers would be performed; but should the omens be otherwise, the rites were instantly to be suspended.

1

[page] 23

1791. February.

I had frequently expressed to Tamaahmaah a desire of being or sent on some of these occasions; and he now informed me, that he had obtained for me the consent of the priests, provided I would, during the continuance of the interdiction, attend to all the restrictions which their religion demanded.

Having readily promised to comply with this condition, I was with some degree of formality visited by several of the principals of their religious order, one of whom was distinguished by the appellation of Eakooa, no Tamaahmaah; meaning the god of Tamaahmaah. This priest had been one of our frequent attendants, notwithstanding which, he was, on this occasion, detected in Stealing a knife; for which offence he was immediately dismissed from our party, and excluded from the precincts of our encampment.

The restraints imposed consisted chiefly in four particulars; first, a total seclusion from the company of the women; secondly, partaking of no food but such as was previously consecrated; thirdly, being confined to the land, and not being afloat, or wet with sea water; and fourthly, not receiving, or even touching, the most trivial article from any one, who had not attended the ceremonies at the morai.

These restrictions were considered necessary to be observed by the whole of our party resident on shore; and about sun-set we attended the summons of the king at the morai, who was there officiating as high priest, attended by some of the principal residents of their religious orders, chanting an invocation to the setting fun. This was the commencement of these sacred rites; but as I propose to treat this subject more fully on a future occasion, I shall for the present postpone the detail of my observations, and briefly state, that their prayers seemed to have some regularity and form, and that they did not omit to pray for the welfare of His Britannic Majesty, and our safe and happy return to our native country. A certain degree of order was perceptible throughout these ceremonies, accompanied by many superstitious and mysterious formalities; amongst which, a very principal one was performed about the dawn of day. At this time the most profound silence was required of every creature within hearing of this sacred place. The

[page] 24

1794. February.

Thursday13.

Friday 14.

king then repeated a prayer in a low tone of voice with the greatest solemnity, and in the middle of it he took up a live pig tied by the legs, and with one effort dashed it to death against the ground: an operation which must be performed without the smallest interruption or cry from the victim, or without the prevailing silence being broken by any noise whatsoever, though of the most trivial kind. This part of the service is supposed to announce their being on terms of friendship with the gods, on which the further ceremonies were carried into execution. A number of hogs, plantains, and cocoa-nuts, were then consecrated for the principal chiefs and priests; the more common productions, such as fish, turtle, fowls, dogs, and the several esculent roots, that compose their food during the intervals between these more sacred taboo's, were not now served up, but for the first time since our arrival, they fared sumptuously on those more delicious articles. The intermediate day and the second night were passed in prayer, during which we found no difficulty in complying with the prescribed regulations; and soon after the sun arose on the 14th, we were absolved from any further attention to their sacred injunctions.

Saturday 15.

Most of our Indian friends returned to our party the following day; and as we all now fed alike on consecrated pork, they were enabled to be infinitely more sociable. Our mode of cookery was generally preferred, as far as related to the dressing of fish, flesh, or fowls; but with respect to roots and the bread fruit, they certainly preserved a superiority.

Tahowmotoo was amongst the most constant of our guests; but his daughter, the disgraced queen, seldom visited our side of the bay. I was however not ignorant of her anxious desire for a reconciliation with Tamaahmaah; nor was the same wish to be misunderstood in the conduct and behaviour of the king, in whose good opinion and confidence I had now acquired such a predominancy, that I became acquainted with his most secret inclinations and apprehensions.

His unshaken attachment and unaltered affection for Tahowmannoo, was confessed with a sort of internal self conviction of her innocence. He acknowledged with great candour, that his own conduct had not been exactly such as warranted his having insisted upon a separation from his

3

[page] 25

1794. February.

queen; that although it could not authorize, it in some measure pleaded in excuse for, her infidelity; and, for his own, he alledged, that his high rank and supreme authority was a sort of licence for such indulgences.

An accommodation, which I considered to be mutually wished by both parties, was urged in the strongest terms by the queen's relations. To effect this desirable purpose, my interference was frequently solicited by them; and, as it concurred with my own inclination, I resolved on embracing the first favorable opportunity to use my best endeavours for bringing a reconciliation about. For although, on our former visit, Tahowmannoo had been regarded with the most favorable impressions, yet, whether from her distresses, or because she had really improved in her personal accomplishments, I will not take upon me to determine, but certain it is, that one, or both of these circumstances united, had so far prepossessed us all in her favor, and no one more so that myself, that it had been long the general wish to see her exalted again to her former dignities. This desire was probably not a little heightened by the regard we entertained for the happiness and repose of our noble and generous friend Tamaahmaah; who was likely to be materially affected not only in his domestic comforts, but in his political situation, by receiving again and reinstating his consort in her former rank and consequence.

I was convinced, beyond all doubt, that there were two or three of the most considerable chiefs of the island, whose ambitious views were inimical to the interests and authority of Tamaahmaah; and it was much to be apprehended, that if the earned solicitations of the queen's father (whose condition and importance was next in consequence to that of the king) should continue to be rejected, there could be little doubt of his adding great strength and influence to the discontented and turbulent chiefs, which would operate highly to the prejudice, if not totally to the destruction, of Tamaahmaah's regal power; especially as the adverse party seemed to form a constant opposition, consisting of a minority by no means to be despised by the executive power, and which appeared to be a principal constituent part of the Owhyhean politics.

VOL. III. E

[page] 26

1794. February.

For these substantial reasons, whenever he was disposed to listen to such discourse, I did not cease to urge the importance and necessity of his adopting measures so highly essential to his happiness as a man, and to his power, interest, and authority as the supreme chief of the island. All this he candidly acknowledged; but his pride threw impediments in the way of a reconciliation which were hard to be removed. He would not of himself become the immediate agent; and although he considered it important that the negociation should be conducted by some one of the principal chiefs in his fullest confidence, yet, to solicit their good offices after having rejected their former overtures with disdain, was equally hard to reconcile to his feelings. I stood nearly in the same situation with his favorite friends; but being thoroughly convinced of the sincerity of his wishes, I spared him the mortification of soliciting the offices he had rejected, by again proffering my services. To this he instantly consented, and observed that no proposal could have met his mind so completely; since, by effecting a reconciliation through my friendship, no umbrage could be taken at his having declined the several offers of his countrymen, by any of the individuals; whereas, had this object been accomplished by any one of the chiefs, it would probably have occasioned jealousy and discontent in the minds of the others.

All, however, was not yet complete; the apprehension that some concession might be suggested, or expected on his part, preponderated against every other consideration; and he would on no account consent, that it should appear that he had been privy to the business, or that it had been by his desire that a negociation had been undertaken for this happy purpose, but that the whole should have the appearance of being purely the result of accident.

To this end it was determined, that I should invite the queen, with several of her relations and friends, on board the Discovery, for the purpose of presenting them with some trivial matters, as tokens of my friendship and regard; and that, whilst thus employed, our conversation should be directed to ascertain, whether an accommodation was still an object desired. That on this appearing to be the general wish, Tamaahmaah

1

[page] 27

179. February.

would instantly repair on board in a hasty manner, as if he had something extraordinary to communicate; that I should appear to rejoice at this accidental meeting, and by instantly uniting their hands, bring the reconciliation to pass without the least discussion or explanation on either side. But from his extreme solicitude left he should in any degree be suspected of being concerned in this previous arrangement, a difficulty arose how to make him acquainted with the result of the proposed conversation on board, which could not be permitted by a verbal message; at length after some thought he took up two pieces of paper, and of his own accord made certain marks with a pencil on each of them, and then delivered them to me. The difference of these marks he could well recollect; the one was to indicate, that the result of my inquiries was agreeable to his wishes, and the other that it was the contrary. In the event of my making use of the former, he proposed that it should not be sent on shore secretly, but in an open and declared manner, and by way of a joke, as a present to his Owhyhean majesty. The natural gaiety of disposition which generally prevails amongst these islanders, would render this supposed disappointment of the king a subject for mirth, would in some degree prepare the company for his visit, and completely do away every idea of its being the effect of a preconcerted measure.

Monday 17.

This plan was accordingly carried into execution on the following monday. Whilst the queen and her party, totally ignorant of the contrivance, were receiving the compliments I had intended them, their good humour and pleasantry were infinitely heightened by the jest I proposed to pass upon the king, in sending him a piece of paper only, carefully wrapped up in some cloth of their own manufacture, accompanied by a message: importing, that as I was then in the act of distributing favors to my Owhyhean friends, I had not been unmindful of his majesty.

Tamaahmaah no sooner received the summons, than he hastened on board, and with his usual vivacity exclaimed before he made his appearance, that he was come to thank me for the present I had sent him, and for my goodness in not having forgotten him on this occasion. This was heard by every one in the cabin before he entered; and

E 2

[page] 28

1794. February.

all seemed to enjoy the joke except the poor queen, who appeared to be much agitated at the idea of being again in his presence. The instant that he saw her his countenance expressed great surprize, he became immediately silent, and attempted to retire; but having posted myself for the especial purpose of preventing his departure, I caught his hand, and joining it with the queen's, their reconciliation was instantly completed. This was fully demonstrated, not only by the tears that involuntarily stole down the cheeks of both as they embraced each other, and mutually expressed the satisfaction they experienced; but by the behaviour of every individual present, whose feelings on the occasion were not to be repressed; whilst their sensibility testified the happiness which this apparently fortuitous event had produced.

A short pause produced by an event so unexpected, was succeeded by the sort of good humour that such a happy circumstance would naturally inspire; the conversation soon became general, cheerful, and lively, in which the artifice imagined to have been imposed upon the king bore no small share. A little refreshment from a few glasses of wine, concluded the scene of this successful meeting.

After the queen had acknowledged in the most grateful terms the weighty obligations she felt for my services on this occasion, I was surprized by her saying, just as we were all preparing to go on shore, that she had still a very great favor to request; which was, that I should obtain from Tamaahmaah a solemn promise, that on her return to his habitation he would not beat her. The great cordiality with which the reconciliation had taken place, and the happiness that each of them had continued to express in consequence of it, led me at first to consider this intreaty of the queen's as a matter of jest only; but in this I was mistaken, for notwithstanding that Tamaahmaah readily complied with my solicitation, and assured me nothing of the kind should take place, yet Tahowmannoo would not be satisfied without my accompanying them home to the royal residence, where I had the pleasure of seeing her restored to all her former honours, and privileges, highly to the satisfaction of all the king's friends; but to the utter mortification of those, who, by

[page] 29

1794. February.

their scandalous reports and misrepresentations, had been the cause of the unfortunate separation.

The domestic affairs of Tamaahmaah having thus taken so happy a turn, his mind was more at liberty for political considerations; and the cession of Owhyhee to His Britannic Majesty became now an object of his serious concern. On my former visit it had been frequently mentioned, but was at that time disapproved of by some of the leading chiefs; who contended, that they ought not voluntarily to surrender themselves, or acknowledge their subjection, to the government of a superior foreign power, without being completely convinced that such power would protect them against the ambitious views of remote or neighbouring enemies. During our absence this subject had been most seriously discussed by the chiefs in the island, and the result of their deliberations was, an unanimous opinion, that, in order to obtain the protection required, it was important that Tamaahmaah should make the surrender in question, formally to me, on the part of His Majesty; that he should acknowledge himself and people as subjects of the British crown; and that they should supplicate that power to guard them against any future molestation.

To this act they were greatly stimulated by the treatment they had received from various strangers, by whom they had been lately visited. Of some of these I was well persuaded they had had too just cause to complain; particularly in the fraudulent and deceitful manner in which the traffic with the natives had been conducted.

In many instances, no compensation whatever had been given by these civilized visitors, after having been fully supplied, on promise of making an ample return, with the several refreshments of the very best quality the country afforded. At other times they had imposed upon the inhabitants, by paying them in commodities of no service or value, though their defects were indetectable by the examination of the natives. This was more particularly the case in those articles which they were most eager to obtain, and most desirous to possess, namely, arms and ammunition; which chiefly composed the merchandize of the North-West American

[page] 30

1794. February.

adventurers. Muskets and pistols were thus exchanged that burst on being discharged the first time, though with the proper loading. To augment the quantity of gunpowder which was fold, it was mixed with an equal, if not a larger, proportion of pounded sea or char-coal. Several of these fire-arms, and some of the powder, were produced for my inspection in this shameful state, and with the hope that I was able to afford them redress.

Many very bad accidents had happened by the bursting of these fire-arms; one instance in particular came within our knowledge a few days after our arrival. A very fine active young chief had lately purchased a musket, and on his trying its effect, with a common charge of powder, it burst; and he not only lost some of the joints of his fingers on the left hand, but his right arm below the elbow, was otherways so dangerously wounded, that, had it not been for the timely assistance afforded him by some of our gentlemen of the faculty, his life would have been in imminent danger.

The putting fire-arms into the hands of uncivilized people, is at best very bad policy; but when they are given in an imperfect and insufficient condition for a valuable consideration, it is not only infamously fraudulent, but barbarous and inhuman. Notwithstanding which, should these inhabitants resort to measures of revenge for the injuries thus sustained, they would be immediately stigmatized with the epithets of savages and barbarians, by the very people who had been the original cause of the violence they might think themselves justified in committing.

Under a conviction of the importance of these islands to Great Britain, in the event of an extension of her commerce over the pacific ocean, and in return for the essential services we had derived from the excellent productions of the country, and the ready assistance of its inhabitants, I lost no opportunity for encouraging their friendly dispositions towards us; notwithstanding the disappointments they had met from the traders, for whose conduct I could invent no apology; endeavouring to impress them with the idea, that, on submitting to the authority and protection of a

[page] 31

1794. February.

superior power, they might reasonably expect they would in future be less liable to such abuses.

The long continued practice of all civilized nations, of claiming the sovereignty and territorial right of newly discovered countries, had heretofore been assumed in consequence only of priority of seeing, or of visiting such parts of the earth as were unknown before; but in the case of Nootka a material alteration had taken place, and great stress had been laid on the cession that Maquinna was stated to have made of the village and friendly cove to Senr. Martinez. Notwithstanding that on the principles of the usage above stated, no dispute could have arisen as to the priority of claim that England had to the Sandwich islands; yet I considered, that the voluntary resignation of these territories, by the formal surrender of the king and the people to the power and authority of Great Britain, might probably be the means of establishing an incontrovertible right, and of preventing any altercation with other states hereafter.

Under these impressions, and on a due consideration of all circumstances, I felt it to be an incumbent duty to accept for the crown of Great Britain the proffered cession; and I had therefore stipulated that it should be made in the most unequivocal and public manner.

For this purpose all the principal chiefs had been summoned from the different parts of the island, and most of them had long since arrived in our neighbourhood. They had all become extremely well satisfied with the treatment they had received from us; and were highly sensible of the advantages they derived from our introducing amongst them only such things as were instrumental to their comfort, instead of warlike stores and implements, which only contributed to strengthen the animosities that existed between one island and another and enabled the turbulent and ambitious chiefs to become formidable to the ruling power. They seemed in a great measure to comprehend the nature of our employment, and made very proper distinctions between our little squadron, and the trading vessels by which they had been so frequently visited; that these were engaged in pursuits for the private emolument of the individuals concerned, whilst those un-

[page] 32

1794. February.

der my command acted under the authority of a benevolent monarch, whole chief object in sending us amongst them was to render them more peaceable in their intercourse with each other; to furnish them with such things as could contribute to make them a happier people; and to afford them an opportunity of becoming more respectable in the eyes of foreign visitors.

These ideas at the same time naturally suggested to them the belief, that it might be in my power to leave the Chatham at Owhyhee for their future protection; but on being informed that no such measure could possibly be adopted on the present occasion, they seemed content to wait with patience, in the expectation that such attention and regard might hereafter be shewn unto them; and in the full confidence that, according to my promise, I would represent their situation and conduct in the most faithful manner, and in the true point of view that every circumstance had appeared to us.

These people had already become acquainted with four commercial nations of the civilized world; and had been given to understand, that several others similar in knowledge and in power existed in those distant regions from whence these had come. This information, as may reasonably be expected, suggested the apprehension, that the period was not very remote when they might be compelled to submit to the authority of some one of these superior powers; and under that impression, they did not hesitate to prefer the English, who had been their first and constant visitors.

The formal surrender of the island had been delayed in consequence of the absence of two principal chiefs. Commanow, the chief of Aheedoo, was not able to quit the government and protection of the northern and eastern parts of the country, though it had been supposed he might have delegated his authority to some one of less importance than himself; but after some messages had passed between this chief and Tamaahmaah, it appeared that it had not been possible to dispense with his presence in those parts of the island.

The other absentee was Tamaahmotoo, chief of Koarra, the person that had captured the Fair American schooner, and with whom I was

[page] 33

1794. February.

not ambitious to have much acquaintance. Since that perfidious melancholy transaction, he had never ventured near any vessel that had visited these shores; this had been greatly to the prejudice of his interest, and had occasioned him inconceivable chagrin and mortification. Of this he repeatedly complained to Tamaahmaah on our former visit; and then, as now, solicited the king's good offices with me to obtain an interview, and permission for his people to resort to the vessels, for the sake of sharing in the superior advantages which our traffic afforded. But, to shew my utter abhorrence of his treacherous character, and as a punishment for his unpardonable cruelty to Mr. Metcalf and his crew, I had hitherto indignantly refused every application that had been made in his favor. When, however, I came seriously to reflect on all the circumstances that had attended our reception and treatment at this island, on our former visit and on the present occasion; when I had reference to the situation and condition of those of our countrymen resident amongst them; and when I recollected that my own counsel and advice had always been directed so to operate on their hasty violent tempers, as to induce them to subdue their animosities, by exhorting them to a forgiveness of past injuries, and proving to them how much their real happiness depended upon a strict adherence to the rules of good fellowship towards each other, and the laws of hospitality towards all such strangers as might visit their shores, I was thoroughly convinced, that implacable resentment, or unrelenting anger, exhibited in my own practice, would ill accord with the precepts I had endeavoured to inculcate for the regulation of theirs; and that the adoption of conciliatory measures, after having evinced, by a discrimination of characters, my aversion to wicked or unworthy persons, was most consistent with my duty as a man, and with the station I then filled.