[map]

[page 1]

A

CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY

OF THE

DISCOVERIES

IN THE

SOUTH SEA

OR

PACIFIC OCEAN.

PART I.

Commencing with an Account of the earliest Discovery of that Sea by Europeans, And terminating with the Voyage of SIR FRANCIS DRAKE, in 1579.

ILLUSTRATED WITH CHARTS.

BY JAMES BURNEY,

CAPTAIN IN THE ROYAL NAVY.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY LUKE HANSARD, NEAR LINCOLN'S-INN FIELDS, AND SOLD BY

G. AND W. NICOL, BOOKSELLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, PALL-MALL; G. AND J. ROBINSON, PATERNOSTER ROW; J. ROBSON, NEW BOND-STREET; T. PAYNE, MEW'S-GATE; AND CADELL AND DAVIES, IN THE STRAND.

1803.

[page 2]

[page i]

TO THE

RIGHT HONOURABLE

SIR JOSEPH BANKS, BART. K. B.

ONE OF HIS MAJESTY'S MOST HONOURABLE PRIVY COUNCIL, PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY, &C. &C.

SIR,

THE volume, which I have the honour to offer to Your notice, is intended as a contribution towards the advancement of a plan for a Digest of Maritime Geographical Discovery; a work which has long been wanted, and which every addition to the general stock renders more necessary.

Carefulness of arrangement is seldom to be found in the early collections of travels. These collections are, in general, to be regarded rather as valuable repositories, than as containing any regular series of information. Our countryman, Hakluyt, deserves to be excepted from this remark: perhaps there is no general collection wherein the compiler has been more studious of method. Indeed, the necessity for method

b

[page] ii

did not formerly exist in the same degree as at present. A single volume might then have contained nearly all the published relations worth preservation, of those who had travelled 'by land or by water.' The words voyage and journey, were then used as synonymous terms; and it is but of late, that they have acquired separate and appropriate meanings. A Spanish book is entitled, " A Diary of the Voyages of King PHILIP V. from Versailles to Madrid, and his Journey to Naples*:" though King PHILIP went by land to Madrid, and by sea to Naples. At the present time, in France, every traveller is called, un voyageur. With books, as with men, when the numbers of a community increase, distinctions become necessary, and sometimes, as in this case, separation. The most obvious and natural, was that marked by the elements: travels by land, and those by sea, we now scarcely consider as undertakings of the same species; the name of journey is given exclusively to the former, and of voyage to the latter; and the distinction is become the more strongly established in Great Britain, from its being so peculiarly a maritime country.

The accounts of voyages now in the possession of the public, are alone sufficient, both in number and in quantity, to form a considerable library. The length to which some of the relations have been extended, especially those of a modern date, and the want of any general arrangement, are become

* Diario de Viajes de el Rey Philipe V., desde Versailles a Madrid; y Jornada a Napoles.

[page] iii

vexatious obstructions to the acquisition of knowledge in maritime geography.

The utility of method and compression, to prevent irregular exuberance in so important a branch of science, is evident beyond contradiction. The manner in which the attempt may be made with the best prospect of success, seems the only object of enquiry. Various modes of reducing the voyages into methodical order present themselves; and probably each so far eligible as to possess some peculiar advantage.

To place the whole in the order of time, would be attended with this great inconvenience, that to obtain a satisfactory account of any one subject, it might be requisite to consult every volume in the collection, however extensive.

To distinguish the discoveries of different nations, making a distinct class of the voyages of each, is liable to the same objection.

A third method, which seems to me to possess many, if not the greatest advantages, is that of classing the voyages according to some hydrographical division of the globe. This has been attempted, but in few instances with any tolerable degree of success. If the divisions have been judiciously allotted, they have not been strictly preserved. The same irregularity has prevailed in collections which consist wholly of republications, where it is difficult to imagine that any good reason could exist against an adherence to correct arrangement.

b 2

[page] iv

Among modern collections, one of the most full, and the most regular, is the Histoire General des Voyages of M. Prevot, the foundation of which was laid by Astley. M. Prevot undertook more than could be performed with accuracy, as every man will discover who undertakes the whole. The earlier volumes required to be supplied by additions and amendments in those afterwards published, by which the subject is much dispersed. The Histoire General des Voyages is nevertheless a most valuable work, and there is reason to be astonished that so large a mass of geographical information should have been so well compiled and published by the exertions of any individual; and the irregularities in the collection are much atoned for by a copious and good index.

To form a complete History of Voyages, is an undertaking that would require, for a great number of years, the labour and united efforts of many able associates. In such an employment, a rapid progress is scarcely compatible with correctness, and especially in those parts where it is thought necessary to compress and consolidate many accounts into one. By compression, is not to be understood the vicious practice of curtailing, in the generality of what are called abridgements; a practice ill adapted to works designed for information.

With respect to nautical remarks, some are involved with the most interesting incidents of a voyage; and some few are, independent of all other circumstances, of more real importance, as well as more satisfactory to curiosity than any incident of the narrative. But it must be acknowledged, that a great part of the nautical remarks in many voyages are not within either of the above descriptions; and the reader cer-

[page] v

tainly has sufficient reason to complain, when he finds the relation of a voyage greatly swelled with minute accounts of days works, lunar observations, &c. even in known seas, and when far distant from land; as if it were a matter of importance to settle the exact geography of a spot in the middle of the ocean, where no mark exists by which it can be ever recognised.

To remedy this, by striking out any part of what is useful, is to exchange superfluity for defect. Many have supposed that to abridge, is a work of no labour; that to read and reject such parts as are disapproved, is nearly the whole that is required: the consequence has been, that abridgements have been undertaken by persons very inadequately skilled in the subject of which their original consisted. Many things that are justly objectionable, cannot be wholly omitted without leaving a chasm: to furnish the necessary explanation on such an occasion, may require both labour and experience; for where the task is carelessly or unskilfully performed, an abridgement is of no use: when information shall be wanted, recourse must be had to the original authority.

To form a complete account of any voyage, it is necessary that no incident, remark, or observation, in any former relation, shall be omitted which can be in the least serviceable to science, which can excite interest, or satisfy curiosity: and to state every thing remarkable or extraordinary, however useless or incredible; with, occasionally, an observation on the degree of credit to which it appears entitled. It is likewise satisfactory, that many things, which appear of little use and uninteresting, should be noticed, though only a single line be

[page] vi

bestowed on them; and not always the less satisfactory for their being noticed with brevity. In short, every thing should be mentioned which possesses any prospect of utility, and the quantity of remark may be proportioned to the importance and to the occasion; avoiding to seek brevity at the expense of the more valuable qualities of information or interest.

All this might be admitted, and the accounts of voyages be yet greatly compressed, and at the same time enriched.

It is not to be supposed that any mode of arranging the subject could be devised, which would obviate every inconvenience. The following division is proposed as one which appears capable of preserving its classes in a great measure distinct from each other.

The first class may contain the voyages to the North of Europe; those in the North seas, and towards the North pole.

The second, those along the West coast of Africa to the Cape of Good Hope; and the discoveries of the Atlantic Islands.

The third, East from the Cape of Good Hope to China, including the Eastern Archipelagos between New Holland and the coast of China. Japan might have a section to itself as a supplement to this class.

The fourth might contain the whole of the discovery of the East side of America, except the Strait of Magalhanes and

4

[page] vii

of Le Maire, which are more connected with the voyages to the South Sea.

The fifth class may comprehend the circumnavigations and voyages to the South Sea. With these, the discoveries on the West coast of North America are so much interwoven, that they cannot, without disadvantage, be separated.

The discoveries made by the Russians in the seas near Kamtschatka, and from thence to the North, would appear not improperly as a supplement to the fifth class.

New Holland might form a sixth class. This country would naturally have divided itself between the third and fifth, had not its importance so much increased within the few last years, that it now requires a distinct class to itself.

The foregoing division is offered as a sketch for a general plan: the classes are capable of modification, according to the convenience or inclination of those who may undertake any part of the task; and, in each, chronological order might with ease be preserved.

An inconvenience to which the plan here suggested may be liable, is, the necessity for repetition which must sometimes occur. To place each particular of information in its respective class, is the method most adapted to useful purposes; yet the voyages must not be broken or disjointed; for by such a process, too much of their interest would be sacrificed. Captain Cook's discovery of the East coast of New Holland could not be spared, either from the account of his voyage, or from a

[page] viii

history of the discovery of New Holland. Other similar instances must occur; but such repetitions would bear a very small proportion to the whole. It might be necessary, however, in a complete collection, when a voyage of any class contained information that also belonged and was material to another class, to make a transfer; substituting, in lieu of the information transferred, a brief, but complete, abstract, with a reference to the place where the fuller description was to be found. For instance, the island of Madeira is described in many voyages of a more distant class. All those descriptions might be collected, and placed in regular order immediately following the account of the discovery of Madeira; and in the part from which the description is taken, the vacancy might be supplied by an abstract and reference, which, as the incidents belong exclusively to the narrative, would leave no chasm; the recapitulation so managed would occupy too small a space to attract notice; each class would be rendered entire, and the accounts of voyages would not sustain injury.

It is a material advantage in regular arrangement, that it affords encouragement and facility to such an undertaking. In a geographical division, each class forms of itself a complete head of discovery; and by being separately considered, the attention of the writer is more concentrated to one point.

For the subject of the present work, I have chosen the discoveries made in the South Sea, to which my attention has been principally directed, from having sailed with that great discoverer and excellent navigator, the late Captain Cook;

[page] ix

under whose command I served as Lieutenant in his two last voyages.

And here, Sir, it is proper to explain my motives for addressing you on this occasion.

Independent of the wish natural to an author to obtain such countenance as he believes will stamp the most estimation on his performance, I am desirous, on many accounts, to recommend my work particularly to your notice. You have visited, and are well acquainted with the scenes I am endeavouring to describe. To you my plan was first communicated, and the encouragement it received from you, determined me to the undertaking. You indulged me with the most unrestrained use of your valuable library; not merely with access, but with permission to take away, for more deliberate consideration, whatever appeared connected with my pursuit; thus rendering it, to all purposes of utility, my own. To these reasons I may justly add, that, next to His Majesty, you have been one of the greatest patronisers and promoters, in this or in any country, of Geographical Discoveries.

To Mr. Dalrymple I have been greatly indebted for assistance. From his large collection of scarce Spanish books, I have been furnished with several original accounts of Spanish discoveries, which I had no other means of procuring. Much labour has likewise been saved me by his "Historical Collection of Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean;" a work which, besides giving a clear outline of the subject, has been extremely useful as an index to direct

c

[page] x

me to original information. It has, indeed, been my Vade Mecum.

It is with great satisfaction I am enabled to state, that the outline of my plan for a General History of Maritime Discovery had the entire approbation of Major Rennel. Let it not be supposed that in saying this, I intend to insinuate any recommendation of the performance of that part which I now submit to the public. The merits of a plan and of its execution are to be decided separately; and very inexperienced must be the reader who encourages himself to expect that every work will fulfil the intention of its author.

I have been favoured by Mr. Arrowsmith with many useful communications, which his knowledge in modern geography, and the materials he has collected concerning the more recent navigations an the Pacific Ocean, so well enabled him to impart.

It might be considered as an omission not to notice that the Histoire des Navigations aux Terres Australes, by M. De Brosses, is similar in plan, and still more so in the extent of its design, to the work which I have undertaken. It is, however, very evident, that the principal object of M. De Brosses, was to explain the advantages of distant colonies, and to recommend the settlement of lands discovered in the Southern hemisphere. His book, considered as a geographical work, affords no proof of laborious research. His information in this respect, appears to have been collected with haste, and adopted without examination. His division of the Southern discoveries into Magellanique, Australasie, and Polynèsie, is

[page] xi

methodical, and clear for the purposes of description; but could not be preserved in narrative, as is evident from the most cursory perusal of M. De Brosses's work. The names likewise are objectionable; inasmuch as they give an appearance of technical obscurity to his subject, keeping the reader at a mysterious distance.

His Table of Contents is well contrived to exhibit, in small space, a general and comprehensive view of all the navigations performed in the different divisions of his subject. It is to be regretted, that this author had so light an opinion of the importance of the task of registering and methodizing geographical information, and has not bestowed on it more of his labour and attention.

The geography of the South Sea has much greater obligations to M. Fleurieu for his Treatise on the Discoveries to the South East of New Guinea. Zeal for the reputation of France has sometimes carried him into discussions not necessary to his subject; but in the more material parts of his work, there is much diligent investigation and comparison, and his labours in this, and in other publications, throw much light on the discoveries made in that part of the globe.

The form of the ensuing History was not a matter of reflection or choice; the subject without premeditation fell into that shape; and, with a few slight deviations from chronological order, it has been found capable of preserving the integrity of each voyage distinct and unmixed with other matter.

How far the account I now offer of the discoveries to the time of Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation maybe defective,

c 2

[page] xii

I know not: I have searched all the materials within my reach, and I have been fortunate in obtaining access to most of the works from which I had reason to expect original information.

In digesting what I found, I have endeavoured to preserve the most striking features of the different narratives I had occasion to consult; and have been especially careful that no geographical notices of any value should be neglected.

Having thus explained my design, I submit my performance to your judgment without further comment; assured as I am, that every attempt to convey useful information, will experience from you favourable attention.

I have the honour,

SIR,

To subscribe myself,

With the most sincere

Respect and Esteem,

Your greatly obliged and

Obedient Servant,

James Burney.

[page xiii]

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

Introductory; containing a brief Account of the Discoveries made in the South Sea, previous to the Voyage of MAGALHANES.

| Page | |

| Line of boundary of the South Sea or Pacific Ocean | l, 2 |

| Columbus, his motives and opinions | 2, 3 |

| Meridian of Partition | 3 |

| Expedition of the Cabots | 4 |

| Corte Real | ib. |

| Strait of Anian | 5 |

| Americus Vespucius | 6 |

| Discovery of R. de la Plata | 7 |

| Discovery of the Sea to the West of America | 8 |

| Name SOUTH SEA | 9 |

| Juan de Solis | 10 |

| Islands de las Perlas | ib. |

| Schemes for sailing Westward to the Moluccas | 11 |

CHAP. II.

Voyage of FERNANDO DE MAGALHANES.

| Page | |

| Arrival of Magalhanes at the court of Spain, and his proposals | 13 |

| Terms of agreement with the emperor Charles V. | 15 |

| Original accounts remaining of the voyage | 16, 18 |

| His departure from Spain | 19 |

| At Brazil | 20 |

| Rio de la Plata | 22 |

| Port San Julian | 25 |

| Mutiny of the fleet | 27 |

| Rio de Santa Cruz, discovery of | 31 |

| Wreck of the Santiago | ib. |

| Natives at Port San Julian | 33 |

| The Guanaco | 34 |

| The natives named Pata-gones | ib. |

| Treachery of the Europeans | 35 |

| Description of the Patagonians | 36 |

| Short vocabulary of their language | 37 |

| Cape de las Virgenes | 39 |

| A strait discovered | ib. |

| Tierra del Fuego | 41 |

| Magalhanes enters the South Sea | 43 |

| Desertion of the St. Antonio | ib. |

| Passage in Pigafetta's narrative | 45 |

| Island San Pablo | 48 |

| Island Tiburones | 49 |

| The name Pacific given to the South sea | 51 |

| Observations on the track of Magalhanes across the South Sea | ib. |

| The Ladrones | 57, 59 |

| Humunu, Zuluan | 60 |

| Archipelago of St. Lazarus | ib. |

| Mazagua | 61 |

| Zebu | 65 |

| Battle at Matan | 77 |

| Death of Magalhanes | 78 |

| His character | 79 |

| Circumnavigation of the globe completed by him | 80 |

d

[page xiv]

CHAP. III.

Sequel of the Voyage after the Death of MAGALHANES.

| Page | |

| Massacre of the Spaniards at Zebu | 83 |

| Bohol | 84 |

| Mindanao | 85 |

| Cagayan Sooloo | ib. |

| Puluan | 86 |

| Borneo port and city | 87 |

| Sensitive tree | 93 |

| Zolo Islands: pearls there | 94 |

| Tidore | 97 |

| Spices produced at the Moluccas | 100 |

| The clove tree | 101 |

| Bird of Paradise | 105 |

| The ship Vitoria sails for Europe | 106 |

| Timor | 110 |

| St. Jago | 111 |

| Arrives in Spain | 112 |

| Attempt of the Trinidad to sail from the Moluccas to New Spain | 115 |

| Advantages of the Voyage of Magalhanes to Geography | 118 |

CHAP. IV.

Progress of Discovery on the Western coast of America, to 1524; Disputes between the Spaniards and Portuguese, concerning the Spice Islands. Attempt to discover a Strait near the Isthmus of Darien.

| Page | |

| Hernando Cortes sends ships along the Western Coast of New Spain | 119 |

| Junta de Badajoz | 122 |

| Attempt of Gomez | 124 |

CHAP. V.

Voyage of GARCIA JOFRE DE LOYASA, from Spain to the Moluccas. Discovery of the North Coast of Papua, by the Portuguese. Voyage of ALVARO DE SAAVEDRA, from New Spain to the Moluccas.

| Page | |

| Loyasa sails from Convnna | 129 |

| Island S. Mateo (St. Matthew) | ib. |

| Cape de las Virgenes | 131 |

| Wreck of Del Cano's ship | ib. |

| Discovery of Land to the South | 133 |

| Natives in the Strait of Magalhanes | 135 |

| Four ships enter the South Sea | 136 |

| One sails to New Spain | 137 |

| Death of Loyasa and Seb. del Cano | ib. |

| Island San Bartolome | 138 |

| At the Ladrone Islands | ib. |

| Mindanao | 140 |

| Island Polola | ib. |

| Talao | 142 |

| Zamafo | 143 |

| Molucca Islands. Tidore | 144 |

| North Coast of Papua discovered by the Portuguese | 145 |

| Menusu, Bufu (Dos Graos) | ib. |

| Islands de Sequeira | 146 |

| Saavedra sails from New Spain | 148 |

| Discovers Islands los Reyes | ib. |

| Arrives at the Moluccas | 150 |

| Sails thence for New Spain | 151 |

| Land of Papua | ib. |

| Returns to the Moluccas | 153 |

| Sails a second time for New Spain | ib. |

| Islands Los Pintados | 154 |

| Los Buenos Jardines | 155 |

| Death of Saavedra | 157 |

| The ship returns to the Moluccas | 158 |

| The Spaniards abandon the Moluccas | 160 |

[page xv]

CHAP. VI.

Various other Expeditions between the Years 1526 and 1533, each inclusive. Discoveries on the Western coast of America. Discovery of California.

| Page | |

| Sebastian Cabot to Brazil | 162 |

| Ships of Villegagnon | 163 |

| Passages across the Isthmus of Darien | ib. |

| First Spanish town built in Peru | 164 |

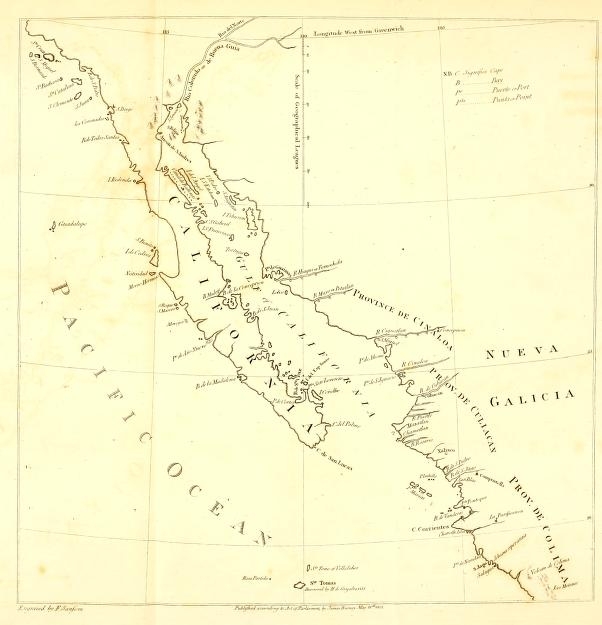

| Ships sent by Cortes discover California | 168 |

| Island Santo Tomas | 169 |

CHAP. VII.

Expedition of Simon de Alcazova. The Spaniards penetrate to the South from Peru.

| Page | |

| Alcazova sails from San Lucar | 171 |

| Island de la Trinidad | ib. |

| He quits the Strait and sails to P° de Leones | 174 |

| Expedition of his people inland | ib. |

| Alcazova killed | 175 |

| City of Los Reyes built | 176 |

| Almagro marches into Chili | ib. |

CHAP. VIII.

The Marquis Del Valle sails to California. Voyage of Hernando de Grijalva, and Alvarado, from Peru to the Moluccas. Voyage of Alonzo de Camargo from Spain to Peru.

| Page | |

| Cortes sails to California, and forms a settlement there | 177, 178 |

| The settlement abandoned | 179 |

| Voyage of Grijalva and Alvarado | 180 |

| Remarks on Galvaom's account of their Voyage | 184 |

| Guedes or Joseph Freewill's Islands | 185 |

| Voyage of Al. de Camargo | 186 |

CHAP. IX.

Relation given by Marcos de Niza, of his Journey to Cevola. Discovery by Francisco de Ulloa, that California was part of the Continent.

| Page | |

| Cevola or Cibola | 191, 192 |

| Voyage of F. de Ulloa | 193 |

| He discovers California to be part of the Continent | 199 |

| Ancon de San Andres | 202 |

| Isle de Cedros | 206 |

d 2

[page xvi]

CHAP. X.

Continuation of the Discoveries to the North of Mexico. Expedition of Hernando de Alarcon, and of Francisco Vasquez de Cornado.

| River de Buena Guia | Pages 212, 2l6 |

CHAP. XI.

Schemes for Maritime Expeditions, formed by Pedro de Alvarado. They are frustrated by Ms Death. Voyage of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, to the North of California.Establishment of the Spaniards in Chili. The Coast of Japan seen for the first Time by Europeans.

| Page | |

| Death of Pedro de Alvarado | 220 |

| Plans he had formed | ib. |

| J. Rod. Cabrillo sails from New Spain | 221 |

| Cape de Fortunas | 223 |

| Santiago the first town built by the Spaniards in Chili | 225 |

| Japan seen for the first time by Europeans | ib. |

CHAP. XII.

Voyage of Ruy Lopez de Villalobos.

| Page | |

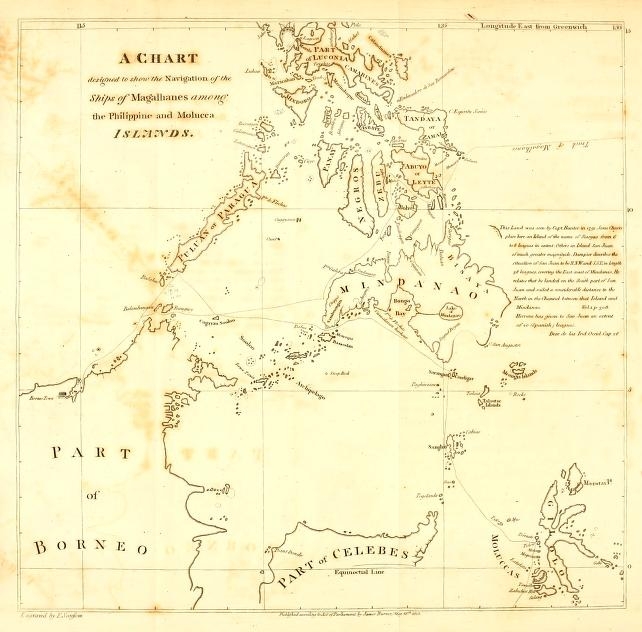

| Track of Villalobos from New Spain to Mindanao | 228, 232 |

| Sto Tome. La Annublada. Roca partida. De los Reyes. Los Corales. Los Jardines. Matalotes. Arrccifes | 228, 233 |

| Mindanao. Sarrangan | 234 |

| The San Juan sails for New Spain | 236 |

| Name Las Philippinas given | ib. |

| Villalobos sails to the Moluceas | 237 |

| The Navigation of the San Juan | 238 |

| Islands: Abriojos, Dos Hermanas, Los Voleanes, Forfana | 239, 240 |

| Second attempt of the San Juan | 241 |

| Land of Papua named New Guinea | ib. |

| Villalobos departs from the Moluccas | 243 |

| His death | ib. |

CHAP. XIII.

Events connected with Maritime Expeditions in the South Sea, to the Year 1558. Ships sent to examine the American Coast to the South from Valdivia. Juan Ladrilleros to the Strait of Magalhanes.

| Page | |

| Preparations for the conquest of the Philippines | 244 |

| City of Valdivia founded | 245 |

| Schemes of P. de Valdivia | 246 |

| He sends two ships to the Straits | ib. |

| Voyage of J. Ladrilleros From Valdivia | 247 |

| He arrives in the Strait | 248 |

| Proceeds to the east entrance, and returns, | ib. |

5

[page xvii]

CHAP. XIV.

Expedition of Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, from New Spain to the Philippine Islands.

| Page | |

| Sails from Navidad | 252 |

| Island de los Barbudos | 253 |

| Islands de los Plazeres | ib. |

| I. de Paxaros | ib. |

| Las Hermanns | ib. |

| Arrival at the Ladrones | 254 |

| At the Philippines. Tandaya | 258 |

| Abuyo. Mazagua | 263 |

| Camiguin. Bohol | 264 |

| Zebu | 266 |

| P. Urdaneta sails for New Spain | 269 |

| Arrives at Acapulco | ib. |

| His route | 270 |

| Zebu submits to the Spaniards | 271 |

CHAP. XV.

Of the Islands discovered near the Continent of America in the Pacific Ocean.

| Page | |

| Islands Juan Fernandez and Mas-a-fuera | 274 |

| The Galapagos | ib. |

| Malpelo. Cocos Island | 275 |

CHAP. XVI.

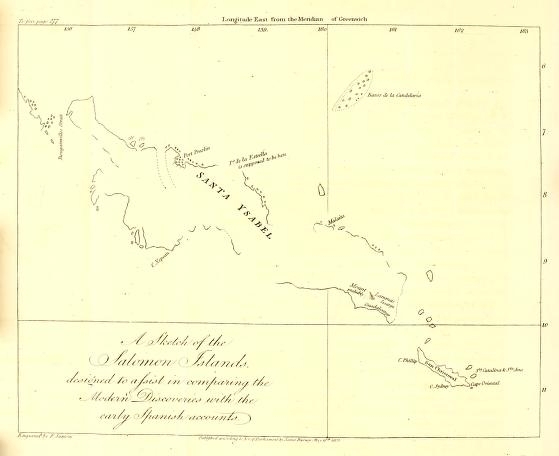

Discovery of the Salomon Islands, by Alvaro de Mendana.

| Page | |

| Isle de Jesus | 278 |

| Baxos de la Candelaria | ib. |

| Santa Ysabel | ib. |

| A brigantine built, and sent on discovery, | 279 |

| Many islands discovered | 279, 280 |

| The brigantine sails round Santa Ysabel | 281 |

| Guadaleanar | 282 |

| The Island San Christoval | 283 |

| Santa Catalina and Santa Ana | 284 |

| Mendana sails for New Spain | 285 |

| Island San Francisco | ib. |

| Returns to Lima | 286 |

| Reports concerning another voyage | ib. |

| Remarks on the situation of the lands discovered by Mendana | 287 |

[page xviii]

CHAP. XVII.

Progress of the Spaniards in the Philippine Islands. The Islands San Felix and San Ambor discovered. Enterprise of John Oxnam, an Englishman, in the South Sea.

| Page | |

| City of Manilla built | 292 |

| Islands S. Felix and S. Ambor | ib. |

| Oxnam crosses the Isthmus of Darien | 294 |

| Builds a vessel and sails into the South Sea | 296 |

| His adventures | 296, 299 |

CHAP. XVIII.

Reports concerning the Discovery of a Southern Continent.

CHAP. XIX.

Voyage of Francis Drake round the World.

| Page | |

| Sails from England | 305 |

| Mogadore | 306 |

| Cape Blanco | 308 |

| Islands: Mayo, Brava | 309 |

| Rio de la Plata | 310 |

| Bay of Seals | 313 |

| The natives there | 313, 316 |

| Port San Julian | 317 |

| Trial of Thomas Doughtie | 320 |

| Three ships pass the strait | 325 |

| They are separated | 326 |

| Southernmost part of Tierra del Fuego discovered | 327 |

| Island Mocha | 329 |

| Valparaiso | 331 |

| Callao | 335 |

| Rich Spanish ship captured | 338 |

| Island Canno | 339 |

| Guatulco | 341 |

| New Albion | 342 |

| Of the situation of Port Drake | 354 |

| Islands of St. James | 355 |

| Drake leaves the coast of America | 356 |

| Islands of Thieves | 357 |

| Islands near the east of Mindanao | ib. |

| Sarangan and Candigar | ib. |

| Molucca Islands. Terrenate | 358 |

| Crab Island near Celebes | 361 |

| The ship on a rock | 362 |

| Extraordinary escape | 363 |

| Java | ib. |

| Arrival at Plymouth | ib. |

| Account of the Elizabeth | 367 |

| The Shallop | 368 |

| The Marigold | 369 |

[page xix]

CHAP. XX.

| Some Account of the Charts to this Volume, with Miscellaneous Observations on the Geography of the 16th Century. Evidence in favour of the Probability that the Country, since named New Holland, was discovered by Europeans within that Period | 370 |

APPENDIX.

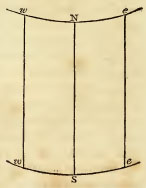

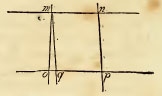

| Remarks on the Projection of Charts, and particularly on the Degree of Curvature proper to be given to the Parallcls of Latitude | 383 |

ERRATA.

| Page | 39, | line 19, and in margin. | for Virgines read Virgenes, |

| 102, | line 4, | for where read whither. | |

| 109, | in margin, | dele Timor. | |

| 113, | line 11, | for circumdediste read circumdedisti. | |

| 121, | line 10, | for douple read double. | |

| 157, | line 18, | for Cortez read Cortes. | |

| 181, | line 9, | for no tact read not act. | |

| 225, | in the last paragraph, | for seen on their coast anchored before Awa,, oppsite the island Tsikok, read had been seen in Awa on the island Tsikok, lying opposite. | |

| [The passage, as it is printed in p. 225, was taken from Schenchzer's translation of Kæmpfer's History of Japan. In the original, the fact is stated as in the correction.] | |||

| 306, | in note *, | for the same read similar. | |

| 329, | line 14, | insert an inverted comma. |

[page xx]

DIRECTIONS FOR THE BINDER.

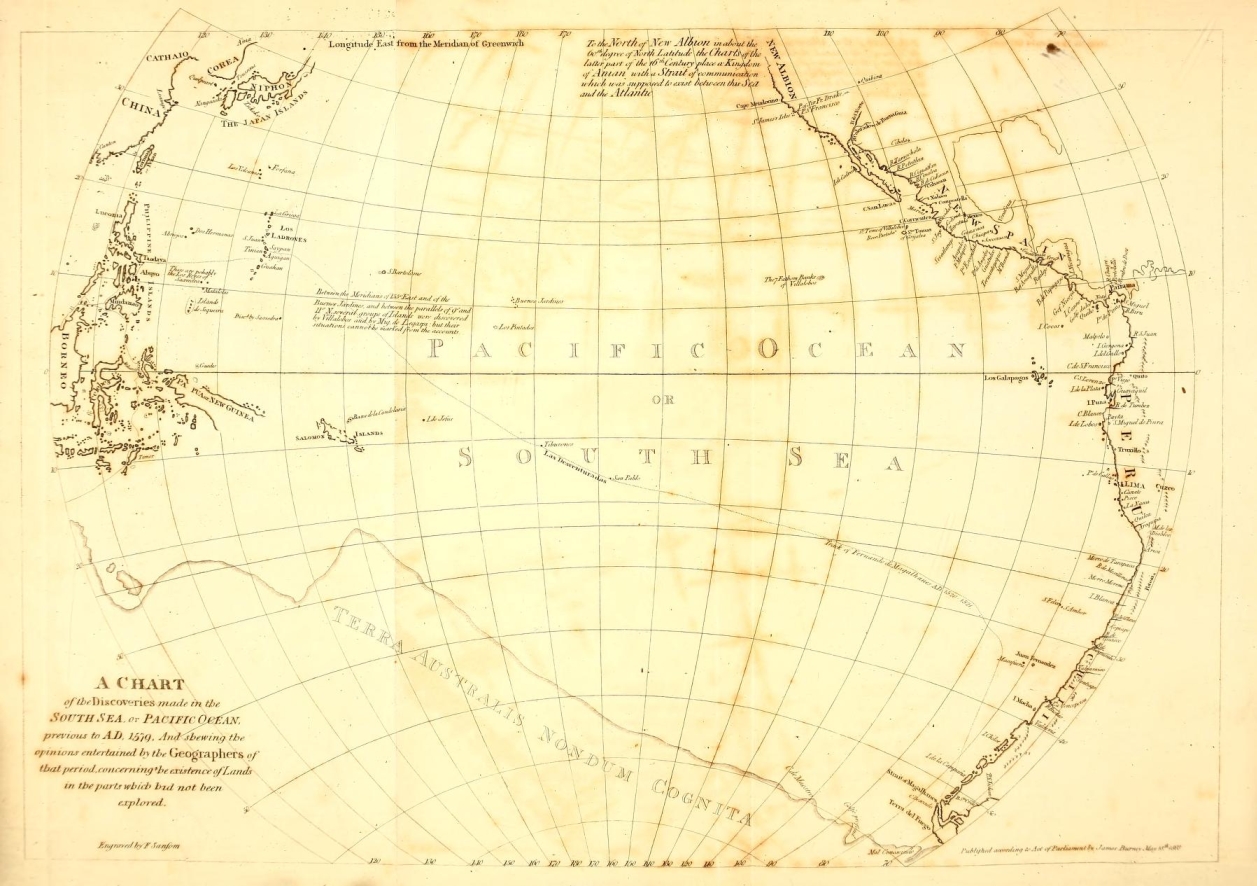

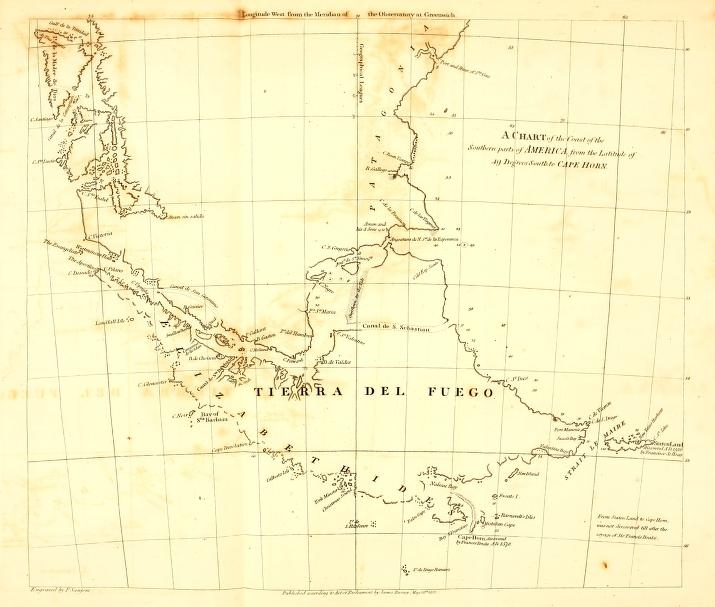

| A Chart of the Discoveries made in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean | To face the Title. |

| Sketch of the Salomon Islands | To face page 277. |

| Chart of the Southern Parts of America | |

| Chart of the Philippine and Molucca Islands | After page 382, and before the Appendix. |

| Chart of California and the Gulf |

[page 1]

A

HISTORY

OF THE

DISCOVERIES

IN THE

SOUTH SEA.

CHAPTER I.

Introductory; containing a brief Account of the Discoveries made in the South Sea, previous to the Voyage ofMAGALHANES.

MOST of the names which have been assigned to the different portions of the Ocean, are descriptive either of the climate, situation, or of some quality peculiar to the sea they are intended to designate. The names, South Sea, and Pacific Ocean, are both of a characterising nature: but it will appear that their application has been extended far beyond every signification of the words which the most liberal construction can allow, and equally beyond the space for which they were originally intended, to limits which, till within the last thirty years, remained undiscovered.

The line of boundary which seems designed by nature for this great sea, is formed, on its Eastern part, by the Western

B

[page] 2

coast of America, taken from its Southern extremity (Terra del Fuego) to the shore near mount St. Elias, in 60 degrees North latitude. The northern limits are marked by the continuation of the American coast from mount St. Elias towards the West, "with the chain of islands called the Fox and the Aleutian islands. The western boundary may be described by a line drawn from the Cape of Kamtschatka (Cape Lopatka) towards the South, passing by the Kurili islands, and the Eastern coast of the Japan islands; from thence by Formosa, and along the East of the Philippines; by Gilolo; by the North and eastern coast of New Guinea; and by the East coast of New Holland, to the South-east cape of Van Demen's land.

Considering the present state of science in our quarter of the globe, it is scarcely possible to reflect, without astonishment, that the whole of this great expanse of ocean, and even its existence, three centuries ago was unknown to Europeans: for though Marco Polo, in the 13th century, gave notice of the existence of a sea Eastward of China, his information did not reach within the limits above described.

1492.

The expectation of being able to sail Westward from Europe without interruption, to the Spice islands, appears to have been the principal inducement of COLUMBUS in undertaking, and of the Spanish court in promoting, the celebrated voyage which first marked the western limits of the Atlantic ocean, and made known to Europeans another continent. The most esteemed geographers of that time were of opinion, and have so represented it in their maps, that from the Western shores of Europe and Africa, to the eastern part of Asia, the whole space was, with the exception of some islands, a continued open sea; Asia being then believed to extend much more towards the

[page] 3

East than experience has since shewn*. The discovery of America opened a new field for enterprize, and with such powerful attractions, as for a time to eclipse the original object, and wholly to engross the attention of the Spanish adventurers. America, however, was not supposed to be of an extent to obstruct entirely the sailing West from Europe to the Eastern Indies; and the attempt to accomplish that navigation was soon renewed.

Meridian of partition.

Immediately after the discovery of what was then called a New World, Pope ALEXANDER the VIth, to prevent disputes between the Spaniards and Portuguese, respecting their titles to the possession of so many new countries, and no doubt partly in support of the maxim long inculcated, that the disposal of earthly kingdoms was a right inherent in the Papal See, issued a bull of donation, fixing as limits of partition, a meridian to be drawn 100 leagues West of the Azores and Cape de Verd islands; from which meridian, the bull granted

* Antonio de Herrera, in the beginning of his history of the Western Indies, has related the following anecdote of Columbus.

'Columbus reckoned, that as cosmographers had written of as much of the world as amounted to 15 hours, without having come to the eastern extremity, the end must consequently be yet farther; and the more it extended to the east, the nearer it must approach to the Cape de Verd islands. He was confirmed in this opinion by his friend Martin de Bohemia (i. e. Martin Behaim).'

Herrera, Dec. 1. lib. 1. cap. 2.

Major Rennel remarks, 'that the splendid discoveries of Columbus were prompted by a geographical error of most extraordinary magnitude;' the extent of China, and its distance to the east from Europe, being both so much magnified, that many at first imagined the new discoveries of Columbus to be a part of Asia.——Geographical System of Herodotus examined and explained, &c. p. 685.

Correspondent to the idea that Columbus, by sailing westward, had reached India, his new discoveries obtained that name. It afterwards became necessary to distinguish the India of the Ancients by the appellation of the Eastern India, and to bestow the addition of Western on the Modern India.

B 2

[page] 4

1494.

1497.

to the Spaniards dominion over all lands newly discovered, and to be discovered, as far as 180 degrees to the West: and to the Portuguese the same distance Eastward. At the instance of the Portuguese, with the consent of the Pope, in 1494, the line of partition was by agreement removed 270 leagues more to the West, that it might accord with their possessions in the Brasils*. Notwithstanding the generosity of Alexander the VIth, thus exclusively exerted in favour of Spain and Portugal, so early as the year 1497†, an expedition was undertaken by the English, which was conducted by the Cabots (John and Sebastian, father and son) who sailed in search of a passage to the North of the Spanish discoveries, but were stopped by the continent.

1500.

In the year 1500, Gaspar de Corte Real, a Portuguese, obtained leave of king EMANUEL to make a voyage for discovering unknown lands. He departed from the Azores with a de-

* On the latter adjustment, the Spaniards afterwards rested their claim to the Spice islands. The Spanish geographers reckoned from the island St. Antonio, the most western of the Cape de Verd islands. 370 Spanish leagues measured on the same parallel, (which seems to be the proper construction of the bull) is equal to 22 degrees of longitude, and would place the Meridian of Partition at 47° west from Greenwich. Argensola says, according to the terms of agreement between the monarchs of Spain and Portugal, the Meridian of Partition fell upon the country of Brasil, at the western part of the entrance of the river Maragnan. Herrtra, in the eharts to his Descrip de las Ind. Occidentales, has drawn it above a degree to the east of the same river. In Herrera's chart, the Meridian of Demarcation is placed 30° west from the first meridian, and the first meridian passes through Cape Verd. The opposite Meridian of Demarcation, supposed to be 180 degrees from the former, has been drawn variously, according to the opinions or views of the different geographers. Malacca was generally included by the Spaniards in their half, which comprehended, as later observations have shewn, not less than 213 degrees of the equator: a division to which the Portuguese did not subscribe.

† One account dates the expedition of Cabot in 1496.

Vide. Hakluyt, Vol. I. p. 6 and 7. edit. 1600.

[page] 5

sign similar to that of the Cabots, and pursued nearly the same track. He fell in with the eastern coast of Newfoundland, and sailed along that side of the island, till he arrived at its northern extremity, where, finding an opening to the West, he proceeded in that direction, till he came near the entrance of the river now called St. Laurence. Finding, in such a length of route, a clear sea before him, he concluded that he was in a passage or strait, which led to the Pacific Ocean; and returned to Lisbon, to communicate the news of his discovery, giving to the supposed strait the appellation of Anian*, it is said, after three brothers so named.

Corte Real's navigation is briefly noticed by several authors, who almost all vary from each other in the circumstances. Antonio Galvaom, who was his countryman, and nearly his contemporary, seems the best entitled to credit. He relates that Gaspar sailed a second time the same voyage, and was wrecked; but another ship that went in company with him, returned to Portugal. Miguel Corte Real, brother to Gaspar, fitted out three ships at his own cost, and went in search of his brother. They arrived at a part of the American coast, where there were several entrances of rivers and inlets. Each vessel took a different route, having previously agreed that they would meet again before the 20th day of August. Two of the ships rejoined each other at the appointed time: but the ship in which was the unfortunate Miguel was not again seen or

* The strait of Anian, formerly the subject of much geographical discussion has by some been supposed to have been so named after a province of China of the name of Ania, mentioned in the travels of Marco Polo: but in the charts of the 16th century, a passage is given to the sea round the north of America and Anian appears as a country on the north west part of that continent.

[page] 6

heard of*. On the return of the two ships to Portugal, Joaō Vasques de Corte Real, the eldest brother, who was chamberlain to king EMANUEL, would have undertaken a voyage in the hope of tracing his two brothers, but the king would not suffer him to embark in so hazardous an enterprise. The land called Labrador was named likewise the land of Corte Real, and the sea near the entrance of the river St. Laurence, was called the Gulf of the Three Brothers †.

1501.

In 1501, Americus Vespucius, a Florentine, then in the service of the king of Portugal, discovered along the coast of South America (not then so named) according to his own account ‡, 600 leagues to the South, and 150 leagues to the

* Tratado dos Dcscobrimentos, pelo Antonio Galvaom, p. 36. edit. 1731. Lisboa.

† Description du Nouveau Monde, Tirée des Tableaux Geographiques de Petrus Bertius.

‡ Letters of Americus Vespucius, in Ramusio's Collection, vol. i. fol. 128.

Americus Vespucius, a vain man, bnt an enterprising and good navigator, has been accused of constantly appropriating to himself the 'glory' of being the first European discoverer of the New Continent. Herrera, Dec. 1. 1. 4. c. 2.

Columbus saw the Continent in August 1498, not then suspecting it to be such; for having found so many large islands, this land was likewise supposed to be of the same description. By Vespucius, it was not seen before June 1499, when he was engaged in an expedition, of which Alonso de Ojeda was the chief commander.

In fact, the first Europeans who saw the main land of America, were the English, under the command of Cabot; and certainly Cabot might have advanced a claim in every respect superior to that of Vespucius. To Columbus, however, the great leader of the western navigation, and to him only, is Europe indebted for the knowledge of America: the discovery of the Continent was a necessary and certain consequence of the discovery of the West Indian islands; besides that he was the actual discoverer of South America.

In 1507 (the Admiral, Christopher Columbus, being dead) Americus Vespucius was taken into the service of the king of Spain, with the title of Pilot Mayor (chief pilot) and was employed in making charts of the new discoveries, which gave him opportunity to affix his own name to the land of South America. Don Diego, the son of Columbus, remonstrated against the disingenuous eonduct of Americus Vespucius [Herrera, Dee. 1. 7. 5.]: the name, nevertheless, not only remained, but has been extended to the whole of that Continent.

6

[page] 7

West, from Cape Saint Augustine: but it does not appear that he kept sight of the coast to so great a distance. In an edition of the geography of PTOLEMY, printed at Rome in the year 1508, there is a chart, an extract from which was lately published by Mr. Dalrymple, in which it is said that ships of the Portuguese had observed a continuance of the land to the South, as far as to 50 degrees of South latitude, without its there terminating. By this, it may be presumed, was meant the voyage of Vespucius: it is not however probable, that he followed the coast regularly so far as to Rio de la Plata; for that river was not known to Europeans till several years after his voyage. It is remarkable in this chart, that the name America does not appear. The land of Brasil is there called Terra Sancle Cruris, and is delineated as being separate from the northern continent.

1502.

Various attempts were likewise made by the Spaniards to penetrate farther to the West: one in particular by COLUMBUS himself in 1502, who, with that view, examined 370 leagues along the coast of that part of the continent, since known by the names of Terra Firma, and the Spanish Main.

1512.

In 1512, Juan de Solis, a Spaniard, discovered the great river de la Plata, which name was given to it on account of the quantity of silver there seen.

The knowledge that the eastern part of China was washed by the ocean, demonstrated the certainty of a sea to the west of the newly discovered continent: but the first actual information obtained by Europeans of this sea, was given to the

[page] 8

1513. Discovery of the sea to the West of America.

1513. Sept. 25.

Spanish conquerors by the native Americans. Basco Nunnez de Balboa, a Spanish commander at Darien, to verify the intelligence he had received, marched with a body of Spaniards, and with Indian guides, across the isthmus. He was opposed in the passage by the natives. They demanded who the bearded strangers were, what they sought after, and whither they-were going? The Spaniards answered*, 'they were Christians, that their errand was to preach a new religion, and to seek gold; and that they were going to the southern sea.' This answer not giving satisfaction, Balboa forcibly made his way. On arriving at the foot of a mountain, from the top of which he was informed that the sea he so anxiously wished to discover was visible; he ordered his men to halt, and ascended alone. As soon as he had attained the summit, he fell on his knees, and with uplifted hands returned thanks to Heaven, for having bestowed on him the honour of being the first European that beheld the sea beyond America. Afterwards, in the presence of his followers, and of many Indians, he walked up to his middle in the water, with his sword and target; and called on them to bear testimony that he took possession of the South Sea, and all which appertained to it, for the king of Castile and Leon. Pietro Marti re, in his Decades, (Dec: 3. lib. 1.) mentions letters received by him from Nunnez, "written after his concise and warlike manner †, by which we understand that he has passed over the mountains dividing the ocean known to. us, from the sea on the south side of this land hitherto unknown." Francisco Pizarro was an officer under Nunnez in this expedition.

* Gomara. Istoria de las Indias, 34 fol. Folio edit. 1552.

† 'Suo militaii stilo compactus.'

[page] 9

The name SOUTH SEA.

The particular position of the coast of that part of the American continent from whence the sea on the other side was first discovered, appears to have stamped on it the denomination of the SOUTH SEA. The isthmus of Darien lies nearly East and West; consequently, there the two seas appear situated, the one to the North, and the other to the South. If the new sea had been first discovered from any part to the South of the bay of Panama, it would probably have received some other appellation. A consequence resulting from the name thus imposed has been, that the Atlantic ocean, by way of contra-distinction, has occasionally been called the North Sea, even in its most southern part. A ship sailing through the strait of Magalhanes, has been said to have passed from the North Sea into the South Sea, or vice versa: and in the Dict. Encyclopédique, we meet with the following article, 'Riviere de la Plata,—qui pr end sa source a Pérou & va se jetter dans la mer du Nord par le 35me deg. de Lat. Merid.*. The two seas nevertheless, relatively to each other, are North and South only in the neighbourhood of the isthmus of Darien: in their general extent they are East and West.

The discovery of the 'South Sea' immediately provoked, or rather, stimulated afresh, the enquiry whether it communicated with the Atlantic, and if so, by what means. As the coast of America in extending to the South, was found to recede westward, in like manner as the coast of Africa does towards the East, it was natural by analogy to infer a similar termination: and as the Portuguese were encouraged to prosecute the discovery round Africa, by a knowledge of the

* 'River de la Plata, whose source is in Peru, and which discharges itself into the North Sea, in the 35th degree of south latitude.'

C

[page] 10

sea to the East of that continent, so likewise were the Spaniards strengthened in their opinion by the discovery of Balboa.

1515. Juan de Solis.

In 1515, the king of Spain, FERDINAND, again sent Juan Diaz de Solis, who was one of the most able navigators of his time, to explore the Southern coast of America, and to endeavour to discover a passage that way into the South Sea, and to the Spice islands. This commander and several of his followers were unfortunately killed in a quarrel with the natives of Rio de la Plata, by which circumstance the accomplishment of the undertaking was reserved for MAGALHANES; the expedition being abandoned after the death of Diaz de Solis, those who remained returning with the vessels to Spain. A small island in Rio de la Plata, near the North shore, is yet distinguished in some of the charts by the name of Solis, and two rivers on the same shore, by the names of the greater and less Rio de Solis.

1516.

Islands de las Perlas.

The Spaniards at Darien in the mean time, in their pursuit of plunder, continued to increase their knowledge of the coast of the newly discovered sea. In 1516, Hernan Ponce de Leon sailed in small barks along the coast to the West from the bay of Panama 140 leagues, and discovered a port to which was given the name of San Lucar, but afterwards of Nicoya, from the Cazique who then governed that part of the country. The Spaniards cut timber near the shore, on the North side of the isthmus, and with extraordinary labour conveyed it across the land to the other shore, for the purpose of building vessels to prosecute greater enterprizes. The conquest of the islands, since named de las Perlas (the Pearl islands) situated opposite to a small gulf in the isthmus, now called the Gulf de San Miguel, was among their ear-

[page] 11

1516.

liest exploits in the South Sea. P. Martire*, speaking of the first of these islands visited by the Spaniards, says, "this island is now better known to our men, who have also brought their fierce king to humanity, and converted him from a cruel tiger, to one of the meek sheep of Christ's flock." From these people the Spaniards took 110lbs., at eight ounces to the pound, (libras octunciales) of pearls, and imposed on them an engagement to furnish 100 lbs. (of the same weight) of pearls annually for the great king of Castile. It is possible that for a short time such a tribute might be collected, as the natives, it may be supposed, had in store a stock that had been accumulating for ages: but it is not very probable that the annual produce of the fisheries would supply such a demand. The pearls that were at first thus obtained, had lost much of their primitive lustre, from the natives having been accustomed to open the shells by means of fire.

Schemes were soon planned for attempting to sail from the shore of the newly discovered sea, to the Spice islands. The ideas then entertained of a Western navigation to the Moluccas, and likewise how generally the subject was at that time discussed, will appear from the following extract†. "There came to me," says P. Martire, "the day before the ides of October this year, 1516, Rodriguez Colminares, and Francisco de la Puente, who affirmed, one that he had heard of, the other that he had seen, divers islands in the South Sea to the West of the Pearl islands, in which trees are engendered and nourished, which bring forth aromatic fruits, as in India; and therefore they conjecture that the

* Dec. 3. l.10. Eden's Translation.

† P. Martire, Dec. 3. lib. 10. Eden's Translation.

c 2

[page] 12

land where the fruitfulness of spice beginneth, cannot be far distant. And many do only desire that leave be granted them to search farther, and they will of their own charges, frame and furnish ships, and adventure the voyage to seek those islands and regions. And they think it better that ships should be prepared in the gulf de San Miguel, than to attempt the way by Cape St. Augustine (in Brasil), which is long, difficult, and full of dangers, and is said to reach beyond the 40th degree of latitude towards the pole. Antartic."

1517.

In 1517, the Spaniards founded Nata, on the Western side of the bay of Panama, which was the first town built by them on the coast of the South Sea; and the following year, they established themselves at Panama. The design of prosecuting discoveries thence towards the Spice islands, assumed a regular form; a commander in chief being appointed by the Spanish court, to direct the proceedings of the ships intended to be fitted out in the South Sea for that purpose. Vessels were constructed and equipped; but the undertaking at this time failed, in consequence of the wood, of which the ships were built, becoming worm-eaten within a month after they were launched into the salt water*.

* Herrera, Hist, de las Ind. Occid. Dec, 2, lib, 4, cap.1.

[page] 13

CHAP. II.

Voyage of FERNANDO DE MAGALHANES.

1517.

ABOUT this time* FERNANDO DE MAGALHANES. †, by birth a Portuguese, and of a good family, who had served five years with reputation in the East Indies, under the celebrated Albuquerque, thinking his services ill requited by the court of Portugal, banished himself ‡ from his native land, and solicited employment from the king of Spain. He was accompanied by one of his countrymen, Ruy Falero, who was esteemed to be a good astronomer and geographer. They offered to prove that the Molucca islands fell within the limits assigned by the Pope to the crown of Caftile, and undertook to discover a passage thither, different from the one used by the Portuguese. It is said that they first presented their plan to Emanuel, king of Portugal, who rejected it with displeasure; probably, being of opinion that it would be prejudicial to the interests of the Portuguese, who were then quietly suffered by the rest of Europe to possess exclusively the advan-

* The Spaniards date the arrival of Magalhanes at the court of Spain, in 1517. The Portuguese in 1518.

† The Spanish authors call him Magallanes, and generally with the Christian name Hernando. Galvaom, De Barros, and others of his countrymen, write the name Fernando de Magalhanes, and this orthography has been adopted by Mr. Dalrymple. The Strange practice (for it is one of those which custom cannot familiarise) of translating proper names, even when composed of words which have no descriptive or second meaning, has not been neglected in that of Magalhanes. In Spanish it is Magallanes; in Italian, Magaglianes; and the English of Magalhanes has been Magellan.

‡——determino de desnaturalizar-se del Reyno. Herrera, Hist. de las Ind. Occ. Dec. 2. lib. 2. c. 10.

[page] 14

tages of the East Indian navigation, to encourage the discovery of a new route to those seas. An enterprize of such a nature, undertaken by one of their countrymen, for the benefit of foreigners, must naturally have excited great indignation in the Portuguese; and to this sentiment may be attributed several anecdotes which the writers of that nation have related to the disadvantage of MAGALHANES.

Some authors have stated that MAGALHANES had himself been at the Moluccas: others, that Francisco Serrano, the discoverer of the Moluccas, was the friend and relation of MAGALHANES, and in correspondence with him. Argensola* says, that the Portuguese general, Albuquerque, sent Antonio de Abreu, Francisco Serrano, and H ERNANDODE MAGALLANES, from Malacca, in three ships, by different routes, to seek for the Moluccas. The credit due to these accounts, will best appear from the track pursued by MAGALIIANES in the voyage about to be related. It is sufficient here to remark, that Galvaom, who was governor for the Portuguese at Ternate (one of the Molucca islands) in the year 1537, and therefore probably was well acquainted with the facts, has named Antonio de Breu, and Francisco Serrano, on this occasion, but not MAGALIIANES.

The emperor CHARLES V. received favourably the proposals of MAGALHANES and Falero, notwithstanding that strong remonstrances and opposition were made by the Portuguese ambassador, who exerted all his influence to prevent this undertaking; and who endeavoured, by large promises, to prevail on MagalHanes to return to Portugal: but (says Fray Gas-

* Conquista de las Malucas, lib. 1.

[page] 15

par *) MAGALHANES had too much regard for his own person to trust to such promises. Assurances, however, were given, that nothing should be attempted prejudicial to the rights of Portugal. MAGALHANES and his companion were made Knights of St. Jago, and the title or rank of Captain was given to them. The Emperor engaged to furnish five ships for the voyage with 234 men, and necessaries for two years: that the chiefs should have the government of such islands as they discovered, with the title of Adelantado †, to them and their heirs born in Spain; that they should receive a twentieth part of the clear income and profits accruing from their discoveries: that in this their first voyage, the discoverers should receive one-fifth of what the ships brought home: that if either MAGALHANES or Falero died, the survivor should be entitled to the whole of the rights contracted for: and during the space of ten years, that no other subject on his own private account was to be allowed, without their licence, to sail the same course. To these grants were added, the privilege of sending, in future, merchandize of the value of 1000 ducats yearly in the king's ships, on condition of paying the king's duty ‡.

Herrera relates, that MAGALHANES, on being questioned by some of the Emperor's ministers, what course he proposed to pursue, if he should not find a passage into the South Sea on the American side, answered, that he would then go by the Cape of Good Hope; for as the Moluccas fell within the

* Couquista de las Philipinas.

† From Adelantar, to precede or excel: a title by which the king's governors or lieutenants were frequently distinguished.

‡ Herrera, Dec. 2. lib.2. c. 19; and Fray Caspar de San Augustin. Conq. de las Islas Philipomas.

[page] 16

Spanish limits, by so doing he could not prejudice the rights of the Portuguese. This anecdote does not appear to be confirmed by any evidence, neither is it strengthened by the subsequent proceedings of MAGALHANES.

Orders for the equipment, according to the foregoing stipulations, were sent to the India House at Seville.

Previous to entering upon the relation of a voyage so important both in itself and in its consequences to Geography, and which it has been observed is not one of those which can easily be traced step by step from any printed account, it may be satisfactory to give a brief statement of the materials which have been consulted.

There is reason to believe, that the most perfect and authentic account of the voyage of MAGALHANES was one written by Pietro Martire, a Milanese, generally distinguished by the appellation of P. Martyr de Angera, who was in the service of the emperor CHARLES V., and at the time a commissioner for the affairs of the Spanish Indies. He was ordered by the emperor to repair to Seville, for the express purpose of collecting all the information that could be obtained, both oral and written, from those who returned, and to draw up a history of the voyage. He completed his task, and the manuscript was sent to Pope ADRIAN VI. at Rome, under whose auspices it was to have been printed. But ADRIAN dying soon after (as likewise did P. Martyr), the work seems to have been neglected by his successor; and, in the sacking of the city by the Connétable de Bourbon, 1527, the copy was unfortunately lost, probably consumed by the flames, as it has never since appeared. In Martire's 5th Decade, cap. 7, which has for title De Orbe Ambito, and is addressed "Adriano Pontifico Maximo," there is an abridged

[page] 17

account, or rather the author has recapitulated the heads of the voyage.

A narrative by Antonio Pigafetta Vicentino, one of those who performed the voyage, appears to have been the first detailed account given to the public. The author relates, that, immediately after his return, he presented to the Emperor a journal, in which he had day by day recorded whatsoever passed in the course of the voyage. The account he published is called a copy of his Journal; but the early part has the appearance of having been composed from memory, probably with the assistance of some notes he might have retained: and there is reason to conjecture, that he did not begin to keep a regular journal till the voyage was considerably advanced. Pigafetta was a man of observation, but with very moderate literary acquirements; he was fond of the marvellous, and much addicted to the superstitions of his time*.

In Ramusio's collection of voyages, there is a very short account, said to have been written by a Portuguese seaman who sailed with MAGALHANES, which contains some particulars worthy of notice respecting the track.

The same collection contains likewise a narrative in the Italian language, in the form of a letter, addressed to cardinal

* Pigafetta's narrative was written in a mixed or provincial dialect of the Italian language. He presented a copy to Louisa of Savoy, the mother of Francis I. when she was regent of France during the minority of her son. A translation into the French language, in which the narration underwent some abridgement, was made and published by her order. Ramusio inserted an Italian version in his collection; but what became of the originals of this and of two other copies (one presented by Pigafetta to the Pope, the other to Villers Lisle Adam, grand master of Rhodes) in not known. A copy, however, has been lately discovered in the Ambrosian library at Milan, translations of which into the French and Italian languages, have been published by Jansen, printer and bookseller at Paris.

D

[page] 18

Salzubrgense, written by Maximilian Transylvanus, one of the secretaries of the Emperor CHARLES the Vth, composed from information principally collected from the officers and mariners who returned, with every one of whom Transylvanus professes to have conversed.

That which has generally been regarded as the most respectable authority in the possession of the public, concerning the voyage of MAGALHANES, is the account of it which appears in Antonio Herrera's History of the Indies. As historiographer to his Catholic Majesty, Herrera had access to all the documents and papers of the Royal Chamber, and. of the Council of the Indies. His relation, nevertheless, in common with every other, is deficient in several important particulars. Fortunately he is most full in the early part, where Pigafetta's account is most defective.

Respecting circumstances of equipment and plan, as well as of several scattered articles of information concerning the voyage itself, other good authorities might be mentioned; but for the most material facts, the works already named are to be regarded, as forming the original source from whence all the subsequent relations have been supplied.

1519.

When the fleet was nearly ready for sailing, a dispute arose between MAGALHANES and Falero, which of them should enjoy the distinction of carrying the flag during the day, and the light at night. To prevent the bad effects of a disagreement between the commanders, the Emperor ordered that Ruy Falero, on the pretext of his not being in perfect health, should remain behind, to be employed on a future occasion. Some accounts say, that excess of study during the negotiation, turned the head of Falero, and that the vexation of this dismission caused his death. He is however mentioned in

[page] 19

the history of Herrera, foliciting the Emperor for employment several years afterwards.

The Ships destined for the voyage were:

The Trinidad, of 130 tons and 62 men. In this ship MAGALHANES embarked.

The San Antonio, 130 tons and 55 men, commanded by Juan de Cartagena, who was comptroller of the fleet.

The Vitoria, 90 tons and 45 men, commanded by Luys de Mendoza, treasurer.

The Conception, 90 tons and 44 men; Gaspar de Quesada, commander.

And the Santiago, of 60 tons and 30 men, commanded by Juan Rodriguez Serrano, who was likewise chief pilot.

The other pilots in the fleet, were Estevan Gomez, a Portuguese, Andres de San Martin, Juan Lopez de Carvallo, Sebastian del Cano, Juan Rodriguez de Mafra, and Basco Gallego.

Before their departure, the oath of fidelity was with public solemnity administered to MAGALHANES, as Captain General of the expedition, in the church of Sta Maria de la Vitoria at Seville; the captains and other principal officers likewise took an oath of fidelity and obedience to MAGALHANES as their commander; and every one belonging to the fleet publicly attended Mass on shore, and made confession.

Departure from Spain, Sept. 20th. 1519.

August 10th, 1519, the ships dropped down the river Guadalquiver, from Seville; but they did not sail from San Lucar till the 20th of September, on which day the voyage must be said to commence. The general established signals for both night and day, and prescribed the order of sailing, according to which the Capitana (by which name it was customary with

D 2

[page] 20

the Spaniards to distinguish the ship of the commander in chief) was to take the lead.

1519. September.

September 26th, the fleet arrived at Teneriff, where they stopped to take wood and water.

October.

October 2d, in the night, they sailed from Teneriff, and when clear of the land steered to the South West, till the next day at noon, at which time the captain-general ordered the course to be changed, fleering South, and at times South by West. This course being different from what had previously been settled in a consultation held with the principal officers and pilots of the fleet, gave much discontent to the captains of the other ships. Juan de Cartagena, commander of the St. Antonio, remonstrated with the general for not steering more towards the West. MAGALHANES made no other answer to his representations, than that it was the business of those under his command to follow his ship, and not to call him to account. This course, however, carried them so near to the coast of Africa, that, after crossing the equinoctial line, they Were becalmed twenty days*, and met with unfavourable winds and weather for a month more.

Pigafetta, in this part of his relation, has given strange descriptions of birds seen by them; some which never make nests, and have no feet, but the female lays and hatches her eggs on the back of the male in the middle of the sea, &c.

December. Brasil.

December 8th, they made the coast of Brasil, in 20° South, and on the 13th anchored in a port which they called the Bay of Sta Lucia, the latitude of which, according; to their

*Herrera, Dec. 2. lib. 4. cap. 9, who says, that in twenty days they did not advance above three leagues.

4

[page] 21

observations, was 23° 45′ South. This it was supposed was the Bahia de Genero, or Rio Janeiro of the Portuguese *.

1519.

Immediately on their arrival, the natives in canoes came to the ships, bringing various kinds of refreshments in great abundance. As a proof of the plenty of provisions, as well as of the simplicity of the natives, it is related, that for a king out of a pack of cards, they gave in exchange fix fowls, and thought they had made a good bargain. For a hatchet they offered a slave; but this traffic MAGALHANES prohibited, that cause of complaint might not be given to the Portuguese nation, and that the number of the consumers of provisions in the fleet might not be increased. In the sequel, nevertheless, it appears that they took at least one Brasilian with them.

The Brasilians are thus described by Pigafetta. 'They are without religion. Natural instinct is their only law. It is not uncommon to see men 125 years of age, and some of 140. They live in long houses or cabins they call boc, one of which sometimes contains a hundred families. They are cannibals, but cat only their enemies. They are olive coloured, well made, their hair short and woolly. They paint themselves both in the body and in the face, but principally the latter. Most of the men had the lower lip perforated in three places,

* In the port where they anchored, Andres, Je San Martin observed, December 18th, the sun's meridian altitude 89° 40′, which, by applying the declination 23° 25′ South, gave for the latitude 23° 45′ South. Herrera, Dee. 2. lib. 4. cap. 10. If they were in Rio Janeiro, the sun, as it always is there at the Southern solstice, must have been South of them, and the result of the observation, properly computed, would have been 23° 05′ South. If the sun was North of them, which in their calculation they have supposed, thev were not at Rio Janeiro, but in some port farther South. Modern observations place Rio Janeiro in 22° 54′ South.

[page] 22

in which they wore ornaments, generally made of stone, of a cylindrical form, about two inches in length. Their chief had the title of Cacique. They are of a good disposition, and extremely credulous. When they first saw us put out our boats, and that they remained close to the sides of the ships, or followed, they imagined them to be the children of the ships.' Part of this description seems borrowed from Vespucius.

Whilst the fleet remained in the Bay of Sta. Lucia, Andres de San Martin, who was styled the cosmographer, observed altitudes of the moon and of Jupiter for determining the longitude: but the results did not prove satisfactory.

December 27th, the fleet proceeded towards the South.

1520.

Riode la Plata.

January 11th, they made Cape Sta. Maria, on the North side of the entrance into Rio de la Plata †, which may be known by three hills, that at a distance appear like islands: and on the 13th, they entered that river, and sailed up two days, when the shoalness of the water obliged them to anchor. Here they took in fresh water and wood, and caught plenty of fish. This was the place where Juan de Solis had been killed, and probably on that account it was that the natives did not come near the

* The particulars of this observation are thus given in Herrera. Saturday December 17th, at 4h 3om A. M. the D was above the Eastern horizon 28° 30′ and Jupiter 33° 15′, being right over the moon. From this difference of 4° 45′ in the altitude, it was computed that 9h 15m had elapsed since the time of Jupiter being in conjunction with the moon: consequently, that the time of the conjunction at the place of observation, was 7h 15m after noon of December 16th. By the almanac of Monteregio, the time at Seville, when the conjunction happened, was December 17th, at 1h 10m P.M. San Martin attributed the error to the tables. Herr. Dec. 2. 4. 10.

† The name given to the river by the natives was Parana-gnacu, which signified the Great Water. [Galvaom's Hist.of Disc.] From this the name of Paraguay seems to be derived, unless from the Spanish words agna, water, and parrar, to spread its branches.

[page] 23

1520.

ships. Some of them appeared in their canoes, but kept at a distance. Three boats were sent towards them, on whose approach they all fled. The Spaniards landed and pursued the Indians, but could not overtake any. They saw trees that had been cut with European hatchets, and on the top of one tree a cross, which had been erected, was standing. One night, a single Indian in a canoe had the courage to venture on board the general's ship, which he entered without shewing any symptom of fear. He had for clothing the skin of a goat. A silver porringer being shewn to him, he made signs that on shore there was plenty of that metal. MAGALHANES gave him a linen shirt and a red cloth waistcoat, and in the morning he was allowed to depart, in hopes that by his report of the treatment he had received, more of the natives would be encouraged to visit the ships: but no others came, neither returned he any more.

The natives here seen are described to have been of extraordinary large stature. "Semi-sylvestres ac nudos homines, Spitamis duabus hunanam super-antes staturam*."

The Santiago was sent to examine higher up the river, and was about fifteen days on that employment. The general, in the mean time, with the two smaller ships, examined the Southern parts, unwilling to believe, without full conviction, that so large a body of water would not afford them a channel to the Western sea.

February.

Tuesday, February the 6th, they quitted this river: and either from being forced to the Northward by the winds, or the general wishing to be more fully satisfied concerning some part of the coast that had already been passed, the fleet were, on

* P. Martyr, Dec. 5. cap. 7.

[page] 24

1520.

the 12th, in 33° 11′ South*, where the Vitoria struck several times on a shoal, but got off without receiving any material damage.

1520.

In 42° 30′ South, they discovered a great bay, which they named the Bay of St. Matias. They followed the direction of the coast in sailing round it 50 leagues, to examine if there was any opening. No anchoring ground was found, and the depth of water in some parts was 80 fathoms †.

To the South of Bay St. Matias they anchored in a bay, where they found great numbers of penguins, sea-calves, seals, &c. In this place they had much bad weather, and the Capitana was in danger of being driven on the rocks, by the parting of one of her cables.

Pursuing their voyage towards the South, they anchored in another bay, which was narrow at the entrance and capacious within, and which the general hoped would prove a safe port for the fleet to winter in‡: but here likewise they experienced so much stormy weather and distress, that they were glad to depart, naming the bay De los Trabajos (i. e. of sufferings.)

* Noticia de las Expediciones al Magalhanes, published as a second part to Relation del Ultimo Viaje al Estrecho, en 1785 y 1786. Madrid 1788. The author of this memoir was favoured with the opportunity of examining some original papers concerning the early voyages, which are preserved in the Archivo General de Indias, amongst which was a diary of Francisco Alvo, one of the officers in the expedition of Magalhanes.

† The peninsula de San Josef, on the Eastern coast of South America, forms with the adjacent shores two bays. One of them, north of the peninsula, extending from about 42° 20′ to 41° South latitude, corresponds with the account here given of the Bay St. Matias. The depth of water in the bay is remarkable, as regular soundings are obtained at much less depth all along that coast, and at a considerable distance from the land.

‡ The places where they anchored between the Bay St. Matias, and Port San Julian, are not sufficiently marked in the accounts to be ascertained, or to encourage conjecture.

[page] 25

1520. April. Port San Julian.

By the slowness of their progress, they must have remained a considerable time at these anchorages, or have met with very unfavourable winds at sea; for, on Easter eve, they anchored in a river and port, to which was given the name of Port San Julian, in latitude 49° 18′ South, by their observations.

MAGALHANES had, for disrespectful or mutinous conduct, deprived Juan de Cartagena of his command, and confined him; and had appointed Alvaro de Mezquita, his own kinsman, to be captain of the St. Antonio. The day after arriving in port, being Easter day, the Captain General gave directions that Mass should be performed on shore, and that every person in the fleet should attend its celebration; but neither Luys de Mendoça, nor Gaspar de Quesada, the captains of the Vitoria and Conception, appeared; which was regarded by the Captain General as a symptom of disaffection; and such in the sequel it proved.

Port San Julian appearing to be a safe and commodious harbour, MAGALHANES determined on remaining there till the winter season, which now approached, should be passed: and as fish were caught in abundance, he ordered a retrenchment in the allowance of provisions. This occasioned much murmuring. The people seeing the barrenness of the country, and apprehensive of the hardships they might have to endure, by wintering in a climate where they already found the cold very severe, represented that the land had all the appearance of extending directly towards the Antarctic Pole, without sign of either termination or strait, and that some of their company had already fallen victims to the difficulties they had encountered: they therefore desired that he would either continue the accustomed allowance, or return back. They alleged " that it was not the King's design they should endeavour

E

[page] 26

1520. Port San Julian.

after impossibilities: it was enough that they had gone farther than any person before them had ever ventured; and if they approached nearer to the Pole, some outrageous tempest might cast them into a place from whence they could never extricate themselves, and must all perish."