[map]

[page i]

A

CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY

OF THE

VOYAGES AND DISCOVERIES

IN THE

SOUTH SEA

OR

PACIFIC OCEAN.

VOLUME IV,

To the Year 1723, including a History of

THE BUCCANEERS OF AMERICA.

BY JAMES BURNEY, F.R.S.

CAPTAIN IN THE KOYAL NAVY.

London:

Printed by Luke Hansard $ Sons, near Lincoln's-Inn Fields;

AND SOLD BY

G. & W. NICOL, BOOKSELLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, AND T. PAYNE & H. FOSS, PALL-MALL;

LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME & BROWN, PATERNOSTER-ROW; CADELL & DAVIES, IN THE STRAND;

NORNAVILLE & FELL, BOND-STREET; AND J. MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

1816.

[page ii]

[page iii]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV.

CHAPTER I.

Considerations on the Rights acquired by the Discovery of Unknown Lands, and on the Claims advanced by the Spaniards.

CHAP. II.

Review of the Dominion of the Spaniards in Hayti or Hispaniola.

| Page | |

| Hayti, or Hispaniola, the Land on which the Spaniards first settled in America | 7 |

| Government of Columbus | 9 |

| Dogs made use of against the Indians | 10 |

| Massacre of the Natives, and Subjugation of the Island | 11 |

| Heavy Tribute imposed | 12 |

| City of Nueva Ysabel, or Santo Domingo | 14 |

| Beginning of the Repartimientos | 16 |

| Government of Bovadilla | ib. |

| The Natives compelled to work the Mines | 17 |

| Nicolas Ovando, Governor | ib. |

| Working the Mines discontinued | 8 |

| The Natives again forced to the Mines | 19 |

| Insurrection in Higuey | 20 |

| Encomiendas established | ib. |

| Africans carried to the West Indies | 21 |

| Massacre of the People of Xaragua | 22 |

| Death of Queen Ysabel | 23 |

| Desperate condition of the Natives | 24 |

| The Grand Antilles | 26 |

| Small Antilles, or Caribbee Islands | ib. |

| Lucayas, or Bahama Islands ib. The Natives of the Lucayas betrayed to the Mines | 27 |

| Fate of the Natives of Porto Rico | 28 |

| D. Diego Columbus, Governor | ib. |

| Increase of Cattle in Hayti. Cuba | 29 |

| De las Casas and Cardinal Ximenes endeavour to serve the Indians | 30 |

| Cacique Henriquez | ib |

CHAP. III.

Ships of different European Nations frequent the West Indies. Opposition experienced by them from the Spaniards. Hunting of Cattle in Hispaniola.

| Page | |

| Adventure of an English Ship | 32 |

| The French and other Europeans resort to the West Indies | 33 |

| Regulation proposed in Hispaniola, for protection against Pirates | ib. |

| Hunting of Cattle in Hispaniola | 34 |

| Matadorcs | ib. |

| Guarda Costas | 35 |

| Brethren of the Coast | 36 |

A 2

[page] iv

CHAP. IV.

Iniquitous Settlement of the Island Saint Christopher by the English and French. Tortuga seized by the Hunters. Origin of the name Buccaneer. The name Flibustier. Customs attributed to the Buccaneers.

| Page | |

| The English and French settle on Saint Christopher | 38 |

| Are driven away by the Spaniards | 40 |

| They return | 41 |

| Tortuga seized by the Hunters | 41 |

| Whence the Name Buccaneer | 42 |

| the Name Flibustier | 43 |

| Customs attributed to the Buccaneers | 45 |

CHAP. V.

Treaty made by the Spaniards with Don Henriquez. Increase of English. and French in the West Indies. Tortuga surprised by the Spaniards. Policy of the English and French Governments with respect to the Buccaneers. Mansvelt, his attempt to form an independent Buccaneer Establishment. French West-India Company. Morgan succeeds Mansvelt as Chief of the Buccaneers.

| Page | |

| Cultivation in Tortuga | 48 |

| Settlements in the West Indies | ib. |

| Tortuga surprised by the Spaniards | 49 |

| Is taken possession of for the Crown of France | 51 |

| Policy of the English and French since named Old Providence | ib. |

| Governments with respect to the Buccaneers | 52 |

| The Buccaneers plunder New Segovia | 53 |

| The Spaniards retake Tortuga | ib. |

| With the assistance of the Buccaneers the English take Jamaica | 54 |

| The French retake Tortuga | ib. |

| Pierre le Grand, a French Buccaneer | ib. |

| Alexandre | 55 |

| Montbars, surnamed the Exterminator | ib. |

| Bartolomeo Portuguez | ib. |

| L'Olonnois, and Michel le Basque, Increase of the English and French take Maracaibo and Gibraltar | 55 |

| Outrages committed by L'Olonnois | ib. |

| Mansvelt, a Buccaneer Chief, attempts to form a Buccaneer Establishment | 56 |

| Island Sta Katalina, or Providence; Death of Mansvelt | 57 |

| French West-India Company | ib. |

| The French Settlers dispute their authority | 58 |

| Morgan succeeds Mansvelt; plunders Puerto del Principe | ib. |

| Maracaibo again pillaged | 59 |

| Morgan takes Porto Bello: his Cruelty | ib. |

| He plunders Maracaibo and Gibraltar | 60 |

| His Contrivances to effect his Retreat | 61 |

[page] v

CHAP. VI.

Treaty of America. Expedition of the Buccaneers against Panama. Exquemelin's History of the American Sea Rovers. Misconduct of the European Governors in the West Indies.

| Page | |

| Treaty between Great Britain and Spain | 63 |

| Expedition of the Buccaneers against Panama | 64 |

| They take the Island Sta Katalina | 65 |

| Attack of the Castle at the River Chagre | ib. |

| Their March across the Isthmus | 66 |

| The City of Panama taken | 67 |

| And burnt | 68 |

| The Buccaneers depart from Panama | 69 |

| Exquemelin's History of the Buccaneers of America | 71 |

| Flibusticrs shipwrecked at Porto Rico; and put to death by the Spaniards | 73 |

CHAP. VII.

Thomas Peche. Attempt of La Sound to cross the Isthmus of America. Voyage of Antonio de Vea to the Strait of Magalhanes. Various Adventures of the Buccaneers, in the West Indies, to the year 1679.

| Page | |

| Thomas Peche | 75 |

| La Sound attempts to cross the Isthmus | ib. |

| Voyage of Ant. de Vea | 76 |

| Massacre of the French in Samana | 77 |

| French Fleet wrecked on Aves | 77 |

| Granmont | ib. |

| Darien Indians | 79 |

| Porto Bello surprised by the Buccaneers | ib. |

CHAP. VIII.

Meeting of Buccaneers at the Samballas, and Golden Island. Party formed by the English Buccaneers to cross the Isthmus. Some Account of the Native Inhabitants of the Mosquito Shore.

| Page | |

| Golden Island | 81 |

| Account of the Mosquito Indians | 82 |

CHAP IX.

Journey of the Buccaneers across the Isthmus of America.

| Page | |

| Buccaneers commence their March | 91 |

| Fort of Sta Maria taken | 95 |

| John Coxon chosen Commander | 96 |

| They arrive at the South Sea | 97 |

[page] vi

CHAR X.

First Buccaneer Expedition in the South Sea.

| Page | |

| In the Bay of Panama | 98 |

| Island Chepillo | ib. |

| Battle with a small Spanish Armament | ib. |

| Richard Sawkins | 99 |

| Panama, the new City | 100 |

| Coxon returns to the West Indies | 101 |

| Richard Sawkins chosen Commander | ib. |

| Taboga; Otoque | 102 |

| Attack of Pueblo Nuevo | 103 |

| Captain Sawkins is killed | ib. |

| Imposition practised by Sharp | 104 |

| Sharp chosen Commander | 105 |

| Some return to the West Indies | ib. |

| The Anchorage at Quibo | ib. |

| Island Gorgona | 106 |

| Island Plata | 107 |

| Adventure of Seven Buccaneers | ib. |

| Ilo | 109 |

| Shoals of Anchovies | ib. |

| La Serena plundered and burnt | ib. |

| Attempt of the Spaniards to burn the Ship of the Buccaneers | ib. |

| Island Juan Fernandez | 110 |

| Sharp deposed from the Command | 111 |

| Watling elected Commander | ib. |

| William, a Mosquito Indian, left on the Island Juan Fernandez | 112 |

| Island Yqueque; Rio de Camarones | 113 |

| They attack Arica | ib. |

| Are repulsed; Watling killed | 114 |

| Sharp again chosen Commander | 115 |

| Huasco; Ylo | ib. |

| The Buccaneers separate | 116 |

| Proceedings of Sharp and his Followers | ib. |

| They enter a Gulf | 118 |

| Shergall's Harbour | 119 |

| Another Harbour | ib. |

| The Gulf is named the English Gulf | ib. |

| Duke of York's Islands | 120 |

| A Native killed by the Buccaneers | 121 |

| Native of Patagonia carried away | ib. |

| Passage round Cape Horn | 122 |

| Appearance like Land, in 57° 50′ S. | ib. |

| Ice Islands | ib. |

| Arrive in the West Indies | 123 |

| Sharp, and others, tried for Piracy | ib. |

CHAP. XI.

Disputes between the French Government and their West-India Colonies. Morgan becomes Deputy Governor of Jamaica. La Vera Cruz surprised by the Flibustiers. Other of their Enterprises.

| Page | |

| Prohibitions against Piracy disregarded by the French Buccaneers | 125–6 |

| Sir Henry Morgan, Deputy Governor of Jamaica | 126 |

| His Severity to the Buccaneers | ib. |

| Van Horn, Granmont, and De Graaf, go against La Vera Cruz | 127 |

| They surprise the Town by Stratagem | 127 |

| Story of Granmont and an English Ship | 128 |

| Disputes of the French Governors with the Flibustiers of Saint Domingo | 130 |

[page] vii

CHAP. XII.

Circumstances which preceded the Second Irruption of the Buccaneers into the South Sea. Buccaneers under John Cook sail from Virginia; stop at the Cape de Verde Islands; at Sierra Leone. Origin and History of the Report concerning the supposed Discovery of Pepys Island.

| Page | |

| Circumstances preceding the Second Irruption of the Buccaneers into the South Sea | 132 |

| Buccaneers under John Cook | 134 |

| Cape de Verde Islands | 135 |

| Ambergris; The Flamingo | ib. |

| Coast of Guinea | 136 |

| Sherborough River | 137 |

| John Davis's Islands | ib. |

| History of the Report of a Discovery named Pepys Island | ib. |

| Shoals of small red Lobsters | 140 |

| Passage round Cape Home | ib. |

CHAP. XIII.

Buccaneers under John Cook arrive at Juan Fernandez. Account of William, a Mosquito Indian, who had lived there three years. They sail to the Galapagos Islands; thence to the Coast of New Spain. John Cook dies. Edward Davis chosen Commander.

| Page | |

| The Buccaneers under Cook joined by the Nicholas of London, John Eaton | 141 |

| At Juan Fernandez | 142 |

| William the Mosquito Indian | ib. |

| Juan Fernandez first stocked with Goats by its Discoverer | 143 |

| Appearance of the Andes | ib. |

| Islands Lobos de la Mar | ib. |

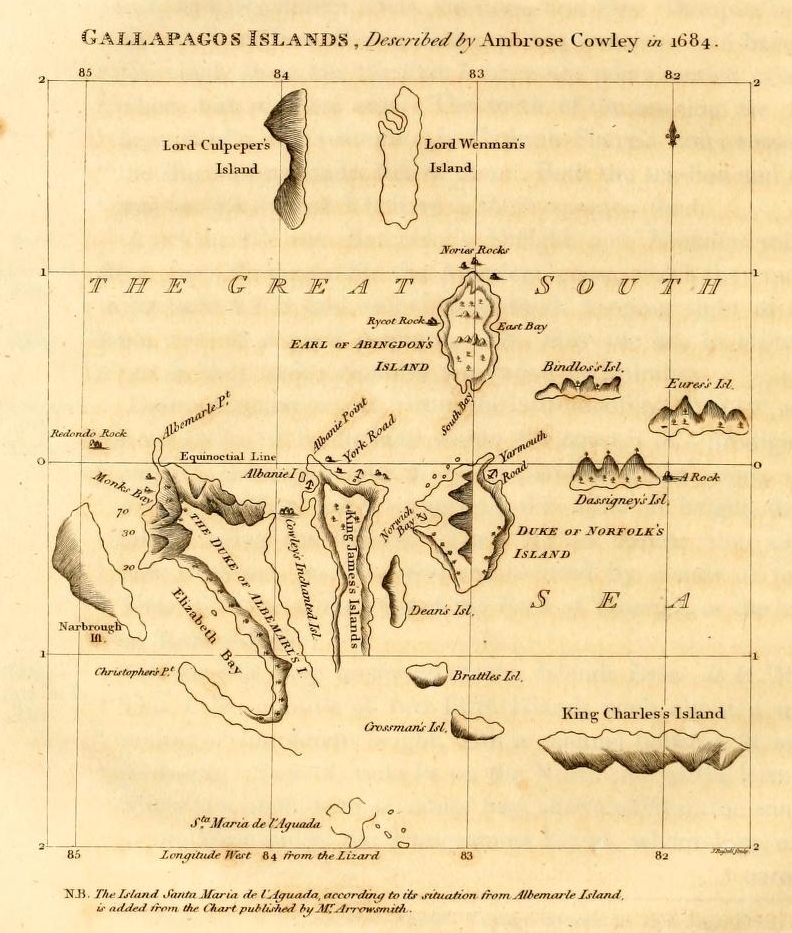

| At the Galapagos Islands | 145 |

| Duke of Norfolk's Island | ib. |

| Cowley's Chart of the Galapagos | 146 |

| King James's Island | ib. |

| Mistake by the Editor of Dampier | ib. |

| Concerning Fresh Water and Herbage at the Galapagos | ib. & 147 |

| Land and Sea Turtle | 148 |

| Mammee Tree | ib. |

| Coast of New Spain; Cape Blanco | 149 |

| John Cook, Buccaneer Commander, dies | ib. |

| Edward Davis chosen Commander | ib. |

CHAP. XIV.

Edward Davis Commander. On the Coast of New Spain and Peru. Algatrane, a bituminous earth. Davis is joined by other Buccaneers. Eaton sails to the East Indies. Guayaquil attempted. Rivers of St. Jago, and Tomaco. In the Bay of Panama. Arrivals of numerous parties of Buccaneers across the Isthmus from the West Indies.

| Page | |

| Caldera Bay | 150 |

| Volean Viejo | 151 |

| Ria-lcxa Harbour | ib. |

| Bay of Amapalla | 152 |

| Davis and Eaton part company | 154 |

| Tornadoes near the Coast of New Spain | 155 |

| Cape San Francisco | ib. |

| Eaton's Description of Cocos Island | ib. |

| Point Sta Elena | 156 |

| Algatrane, a bituminous Earth | ib. |

[page] viii

| Page | |

| Rich Ship wrecked on Point Sta Elena | 157 |

| Manta; Rocks near it, and Shoal | ib. |

| Davis is joined by other Buccaneers | ib. |

| The Cygnet, Captain Swan | ib. |

| At Isle de la Plata | 159 |

| Cape Blanco, near Guayaquil; difficult to weather | ib. |

| Payta burnt | 160 |

| Part of the Peruvian Coast where it never rains | ib. |

| Lobos de Tierra, and Lobos de la Mar | ib. |

| Eaton at the Ladrones | 161 |

| Nutmeg Island, North of Luconia | 163 |

| Davis on the Coast of Peru | ib. |

| Slave Ships captured | ib. |

| The Harbour of Guayaquil | 164 |

| Island Sta Clara: Shoals near it | 164 |

| Cat Fish | 165 |

| The Cotton Tree and Cabbage Tree | 166 |

| River of St. Jago | ib. |

| Island Galio; River Tomaco | 167 |

| Island Gorgona | ib. |

| Pearl Oysters | 168 |

| Galera lsle | ib. |

| The Pearl Islands | 169 |

| Arrival of fresh bodies of Buccaneers from the West Indies | 170 |

| Grogniet and L'Escuyer | ib. |

| Townley and his Crew | 171 |

| Pisco Wine | 172 |

| Port de Pinas; Taboga | 173 |

| Chepo | 174 |

CHAP. XV.

Edward Davis Commander. Meeting of the Spanish and Buccaneer Fleets in the Bay of Panama. They separate without fighting. The Buccaneers sail to the Island Quibo. The English and French separate. Expedition against the City of Leon. That City and Ria Lexa burnt. Farther dispersion of the Buccaneers.

| Page | |

| The Lima Fleet arrives at Panama | 176 |

| Meeting of the two Fleets | 177 |

| They separate | 180 |

| Keys of Quibo: The Island Quibo | 181 |

| Rock near the Anchorage | ib. |

| Serpents; The Serpent Berry | 182 |

| Disagreements amonsr the Buccaneers | ib. |

| The French separate from the English | 183 |

| Knight, a Buccaneer, joins Davis | ib. |

| Expedition against the City of Leon | 184 |

| Leon burnt by the Buccaneers | 186 |

| Town of Ria Lexa burnt | 187 |

| Farther Separation of the Buceaneers | ib. |

CHAP. XVI.

Buccaneers under Edward Davis. At Amapalla Bay; Cocos Island; The Galapagos Islands; Coast of Peru. Peruvian Wine. Knight quits the South Sea. Bezoar Stones. Marine Productions on Mountains. Vermejo. Davis joins the French Buccaneers at Guayaquil. Long Sea Engagement.

| Page | |

| Amapalla Bay | 188 |

| A hot River | ib. |

| Cucos Island | 189 |

| Effect of Excess in drinking the Milk of the Cocoa-nut | 190 |

| At the Galapagos Islands | ib. |

[page] ix

| Page | |

| On the Coast of Peru | 191 |

| Peruvian Wine like Madeira | ib. |

| At Juan Fernandez | 192 |

| Knight quits the South Sea | ib. |

| Davis returns to the Coast of Peru | ib. |

| Bezoar Stones | 193 |

| Marine Productions found on Moun tains; Vermejo | ib. |

| Davis joins the French Buccaneers at Guayaquil | 195 |

| They meet Spanish Ships of War | 196 |

| A Sea Engagement of seven days | ib. |

| At the Island de la Plata | 198 |

| Division of Plunder | 199 |

| They separate, to return home by different Routes | 200 |

CHAP. XVII.

Edward Davis; his Third visit to the Galapagos. One of those Islands, named Santa Maria de l'Aguada by the Spaniards, a Careening Place of the Buccaneers. Sailing thence Southward they discover Land. Question, whether Edward Davis's Discovery is the Land which was afterwards named Easter Island? Davis and his Crew arrive in the West Indies.

| Page | |

| Davis sails to the Galapagos Islands | 201 |

| King James's Island | 202 |

| The Island Sta Maria de l'Aguada | 203 |

| Davis sails from the Galapagos to the Southward | 205 |

| Island discovered by Edward Davis | 206 |

| Question whether Edward Davis's Land and Easter Island are the same Land | 207 |

| At the Island Juan Fernandez | 210 |

| Davis sails to the West Indies | 211 |

CHAP. XVIII.

Adventures of Swan and Townley on the Coast of New Spain, until their Separation.

| Page | |

| Bad Water, and unhealthiness of Ria Lexa | 213 |

| Island Tangola | 214 |

| Guatulco; El Buffadore | 215 |

| Vinello, or Vanilla, a Plant | 216 |

| Island Sacrificio | ib. |

| Port de Angeles | ib. |

| Adventure in a Lagune | 217 |

| Alcatraz Rock; White Cliffs | 218 |

| River to the West of the Cliffs | ib. |

| Snook, a Fish | ib. |

| High Land of Aeapulco | 219 |

| Sandy Beach, West of Acapulco | ib. |

| Hill of Petaplan | 220 |

| Chequetan | ib. |

| Estapa | ib. |

| Hill of Thelupan | 221 |

| Volcano and Valley of Colima | ib. |

| Salagua | 222 |

| Report of a great City named Oarrah | ib. |

| Coronada Hills | 223 |

| Cape Corrientes | ib. |

| Keys or Islands of Chametly form a convenient Port | ib. |

| Bay and Valley de Vanderas | 225 |

| Swan and Townley part company | 226 |

VOL. IV. b

[page] x

CHAP. XIX.

The Cygnet and her Crew on the Coast of Nueva Galicia, and at the Tres Marias Islands.

| Page | |

| Coast of Nueva Galicia | 227 |

| Point Ponteque | ib. |

| White Rock, 21° 51′ N | 228 |

| Chametlan Isles, 23° 11′ N | ib. |

| The Penguin Fruit | ib. |

| Rio de Sal, and Salt-water Lagune | ib. |

| The Mexican, a copious Language | 229 |

| Mazatlan | ib. |

| Bay of Vanderas | 236 |

| Rosario, an Indian Town; River Rosario; Sugar-loaf Hill; Caput Cavalli; Maxentelbo Rock; Hill of Xalisco | 230 |

| River of Santiago | 230 |

| Town of Sta Pecaque | 231 |

| Buccaneers defeated and slain by the Spaniards | 233 |

| At the Tres Marias | 234 |

| A Root used as Food | 235 |

| A Dropsy cured by a Sand Bath | ib. |

CHAP. XX.

The Cygnet. Her Passage across the Pacific Ocean. At the Ladrones. At Mindanao.

| Page | |

| The Cygnet quits the American Coast | 237 |

| Large flight of Birds | ib. |

| Sarangan and Candigar | 243 |

| Bank de Santa Rosa | 238 |

| At Guahan | ib. |

| Flying Proe, or Sailing Canoe | 239 |

| Bread Fruit | 241 |

| Eastern side of Mindanao, and the Island St. John | 241 |

| Shoals and Breakers near Guahan | ib. |

| Harbour or Sound on the South Coast of Mindanao | ib. |

| River of Mindanao | 244 |

| City of Mindanao. | ib. |

CHAP. XXI.

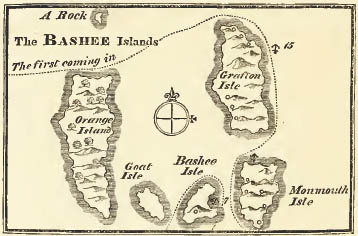

The Cygnet departs from Mindanao. At the Ponghou Islcs. At the Five Islands. Dampier's Account of the Five Islands. They are named the Bashee Islands.

| Page | |

| South Coast of Mindanao | 249 |

| Among the Philippine Islands | ib. |

| Pulo Condore | ib. |

| In the China Seas | 250 |

| Ponghou Isles | 250 |

| The Five Islands | ib. |

| Dampier's Description of them | 250—256 |

[page] xi

CHAP. XXII.

The Cygnet. At the Philippines, Celebes, and Timor. On the Coast of New Holland. End of the Cygnet.

| Page | |

| Island near the SE end of Mindanao | 257 |

| Candigar, a convenient Cove there | ib. |

| Low Island and Shoal, SbW from the West end of Timor | 258 |

| NW Coast of New Holland | ib. |

| Bay on the Coast of New Holland | 258 |

| Natives | 259 |

| An Island in Latitude 10° 20′ S | 261 |

| End of the Cygnet | ib. |

CHAP. XXIII.

French Buccaneers under François Grogniet and Le Picard, to the Death of Grogniet.

| Page | |

| Point de Burica; Chiriquita | 263 |

| Unsuccessful attempt at Pueblo Nuevo | 265 |

| Grogniet is joined by Townley | ib. |

| Expedition against the City of Granada | 266 |

| At Ria Lexa | 269 |

| Grogniet and Townley part company | ib. |

| Buccaneers under Townley | ib. |

| Lavelia taken, and set on fire | 270 |

| Battle with Spanish armed Ships | 274 |

| Death of Townley | 277 |

| Grogniet rejoins company | 278 |

| They divide, meet again, and reunite | 279 |

| Attack on Guayaquil | 280 |

| At the Island Puna | 282 |

| Grogniet dies | ib. |

| Edward Davis joins Le Picard | 283 |

CHAP. XXIV.

Retreat of the French Buccaneers across New Spain to the West Indies. All the Buccaneers quit the South Sea.

| Page | |

| In Amapalla Bay | 286 |

| Chiloteca; Massacre of Prisoners | ib. |

| The Buccaneers burn their Vessels | 287 |

| They begin their march over land | 288 |

| Town of New Segovia | 289 |

| Rio de Yare, or Cape River | 291 |

| La Pava; Straiton; Le Sage | 294 |

| Small Crew of Buccaneers at the Tres Marias. Their Adventures | 295 |

| Story related by Le Sieur Froger | ib. |

| Buccaneers who lived three years on the Island Juan Fernandez | 296 |

b 2

[page] xii

CHAP. XXV.

Steps taken towards reducing the Buccaneers and Flibustiers under subordination to the regular Governments. War of the Grand Alliance against France. Neutrality of the Island St. Christopher broken.

| Page | |

| Reform attempted in the West Indies | 298 |

| Campeachy burnt | ib. |

| Danish Factory robbed | 300 |

| The English driven from St. Christopher | 301 |

| The English retake St. Christopher | 302 |

CHAP. XXVI.

Siege and Plunder of the City of Carthagena on the Terra Firma, by an Armament from France in conjunction with the Flibustiers of Saint Domingo.

| Page | |

| Armament under M. de Poinds | 303 |

| His Character of the Buccaneers | 304 |

| Siege of Carthagena by the French | 307 |

| The City capitulates | 309 |

| Value of the Plunder | 313 |

CHAP. XXVII.

Second Plunder of Carthagena. Peace of Ryswick, in 1697. Entire Suppression of the Buccaneers and Flibustiers.

| Page | |

| The Buccaneers return to Carthagena | 316 |

| Meet an English and Dutch Squadron | 319 |

| Peace of Ryswick | 320 |

| Causes which led to the Suppression of the Buccaneers | ib. |

| Providence Island | 322 |

| CONCLUSION | 323 |

[page] xiii

PART II.

CHAPTER I.

Voyage of Captain John Strong to the Coast of Chili and Peru.

| Page | |

| From the Downs | 330 |

| At John Davis's Southern Islands | ib. |

| A Sound or Strait discovered | ib. |

| Is named Falkland Sound | 331 |

| Foxes. Conjectures concerning them | ib. |

| In the Strait of Magalhanes;—Natives | 332 |

| Island Mocha | 333 |

| Baldivia | 333 |

| At Point Sta Elena | ib. |

| Mas-a-fuero | 335 |

| Juan Fernandez | ib. |

| Four Buccaneers who had lived on the Island nearly three years | ib. |

CHAP. II.

Notices of the Discoveries of two Islands, whose Situations have not been ascertained. Voyage of M. de Gennes to the Strait of Magalhanes. Of Gemelli Careri.

| Page | |

| Floating Weeds near California | 338 |

| I. de San Sebastian | ib. |

| Island Juan de Gallego | 339 |

| M. de Gennes | ib. |

| At the Island Goree | 340 |

| In the River Gambia | ib. |

| Treatment of Slaves | ib. |

| In the Strait of Magalhanes | 341 |

| Baye Boucault | ib. |

| Natives at Port Famine | ib. |

| Baye Françoise | 342 |

| De Gennes sails back out of the Strait | ib. |

| Of Gemelli Careri | 343 |

| His passage across the Pacific | 344 |

CHAP. III.

Of the Expeditions of the Spaniards in California, to their first Establishment, in 1697.

| Page | |

| Expedition of Otondo in 1683 | 345 |

| Settlement formed at Port de la Paz | 347 |

| Tribe called Koras | 347 |

| The Guaycuros | ib. |

| Natives treacherously murdered | 348 |

| Port de la Paz abandoned | ib. |

| Second Expedition of Otondo | 349 |

| Settlement of San Brano | ib. |

| Is abandoned | 350 |

| The Conquest of California undertaken again, in 1697 | 351 |

| Salvatierra goes to California | 352 |

| Presidio de San Loreto founded | 353 |

| Doubt concerning the junction of California with the Continent | 357 |

| The junction verified by P. P. Kino and Salvatierra | ib. |

[page] xiv

CHAP. IV.

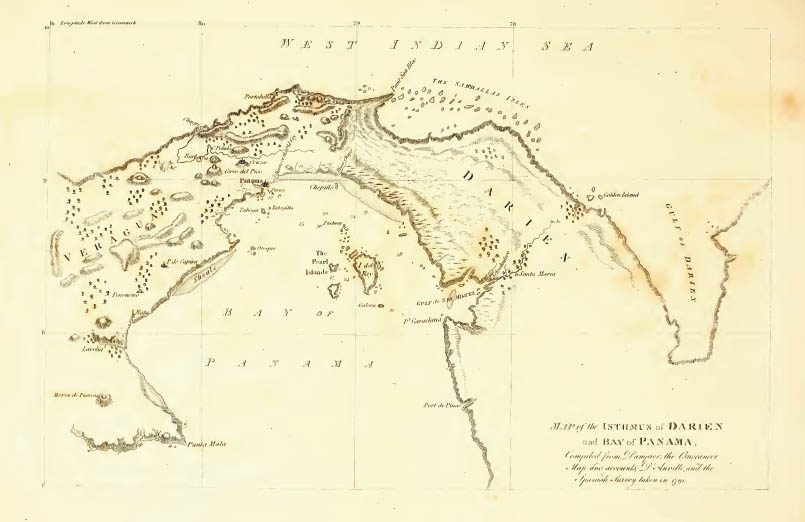

The Company of Scotland trading to Africa and the Indies. History of the Colony formed by them at Darien.

| Page | |

| Act of the Parliament of Scotland | 359 |

| The Company's Ships sail for America | 363 |

| Convention made with the Darien Chiefs | 364 |

| New Edinburgh built | 365 |

| Its advantages ibid & | 366 |

| Is abandoned to the Spaniards | 369 |

| Indemnification made to the Scots Company at the Union of England and Scotland | 374 |

CHAP. V.

Voyage of M. de Beauchesne Gouin.

| Page | |

| French Company for establishing Colonies in South America fit out Ships | 375 |

| Beauchesne sails to Patagonia | 376 |

| In the Strait of Magalhanes | ib. |

| Natives there | ib. |

| At Elizabeth Bay—Shoal | 377 |

| Island Louis le Grand | ib. |

| River named Du Massacre | 378 |

| Two distinct Tribes | ib. |

| Cape Gate, supposed to be Cape Quad | 379 |

| Harbour of San Domingo | 380 |

| At Arica | ib. |

| Balsa of Arequipa | 381 |

| Galapagos Islands | ib. |

| Isle à Tabac—I. de Sante | ib. |

| Mascariu | ib. |

| Isle Beauchesne | 382 |

| Represented as two Islands by Frezier | 383 |

CHAP. VI.

Voyage to the South Atlantic Ocean, by Dr. Edmund Halley.

| Page | |

| Observations for the Longitude at sea | 386 |

| Situation of the Island Trinidada | 386 |

CHAP. VII.

Voyage of Captain William Dampier, in the Roebuck, to New Holland, and New Guinea.

| Page | |

| Teneriffe; Road of Santa Cruz | 389 |

| Malmesy Wine | ib. |

| Mayo. Trape-boat | 390 |

| St. Jago; Road and Town. Bahia | 391 |

| Petrel | 392 |

| Western Coast of New Holland | 394 |

| b rolhos | ib. |

| Dirk Hartog's Reede, or Shark's Bay | 395 |

| Kanguroos; Guanos | 396 |

| N.W. Coast of New Holland | 399 |

| Archipelago of Islands along the coast | ib. |

| Tasman's Chart | 400 |

| Rosemary Island | ib. |

| Natives of New Holland | 402–3 |

| Low sandy Island | 405 |

| At Timor | 406 |

[page] xv

| Page | |

| The Voyage to New Guinea | 406 |

| Freshwater Bay. White Island | ib. |

| Pulo Sabuda. Gape Mabo | 407 |

| Cockle Island | ib. |

| Pigeon Island | 408 |

| Little Providence Island | 409 |

| Matthias Island. Squally Island | 410 |

| Vischer's Island | ib. |

| Natives; Slinger's Bay | 411 |

| Gerrit Denijs Island; Natives | 412–413 |

| Antony Kaan's Island | 413 |

| Island St. Jan | 414 |

| St. George's Bay and Island | 415 |

| Cape Orford | ib. |

| Port Montague | 416 |

| Intercourse with the Natives | 417 |

| Strait discovered by Dampier | 420 |

| Burning Island. King William's Cape | ib. |

| Cape Gloucester; Cape Anne | 421 |

| Sir George Rooke's Isle | ib. |

| Northern Coast of New Guinea | 422 |

| Cape Mabo | 423 |

| Uncommon Tides | 424 |

| From Timor. Search for the Tryal Rocks | ib. |

| At the Island Ascension | 425 |

| The Ship springs a Leak | ib. |

| Loss of the Ship | 427 |

| Spring of fresh Water found at Ascension | ib. |

CHAP. VIII.

Voyage of Captain William Dampier to the South Sea, with the Ships St. George and Cinque Ports Galley.

| Pape | |

| A Strait named Jelouchte | 431 |

| At Isla Grande | 432 |

| At Juan Fernandez | 433 |

| Engagement with a French Ship | 434 |

| On the coast of Peru | 435 |

| Las Hormigas Rocks; Island Gallo | ib. |

| In the Bay of Panama | 436 |

| The St. George and Cinque Ports part Company | 437 |

| Proceedings in the St. George | 438 & seq. |

| Point de la Galera | 438 |

| Gulf of Nicoya | 439 |

| Desertion of Clipperton | ib. |

| Volcanos of Guatimala | 440 |

| Along the Coast of New Spain | 441 |

| Motines Mountains. Bay of Martaba | ib. |

| Dampier engages the Manila Galeon, and is repulsed | 442 |

| In Amapalla Bay | ib. |

| The Ceawau | 443 |

| The ship Saint George abandoned at the Lobos Isles | ib. |

| Funnel from New Spain to the East Indies | 444 |

| Island S.W. of the Ladrones | ib. |

| The Guedes | ib. |

| New Guinea, St. John's Strait | 446 |

| Clipperton's Isle | 447 |

| Account of the Cinque Ports Galley | ib. |

| Alexander Selkirk | 448 |

| A fourth volume to Dampier's Voyages, published by Knapton | ib. |

CHAP. IX.

1703 to 1708.—Voyages of the Dutch for the farther Discovery of New Holland and New Guinea. Navigations of the French to the South Sea.

| Page | |

| Voyage from Timor to the North Coast of New Holland | 450 |

| The Geelvink to New Guinea | 451 |

| Straits between Waigeeuw and New Guinea | 452 |

| Natives of New Guinea | ib. |

[page] xvi

| Page | |

| Coudrai Perée and Fouquet | 453 |

| Pere Nyel | ib. |

| Isles of Anican | 454 |

| Patagonians | ib. |

| Malouines, or Isles Nouvelles | 454 |

| Pere Feuillée | 455 |

| Land of the Assumption | ib. |

CHAP. X.

Voyage of the Ships Duke and Dutchess, of Bristol, under Captain Woodes Rogers, round the World.

| Page | |

| Island St. Vincent; the Bay | 458 |

| John Davis's South Land, or Falkland Islands | 459 |

| Beauchesne's Island | 460 |

| At Juan Fernandez | 461 |

| Alexander Selkirk found there | 462 |

| Islands Lobos de la Mar | 468 |

| Guayaquil taken and ransomed | 469 |

| At the Galapagos | ib. |

| Simon Hatley missing | 470 |

| Island Gorgona | 471 |

| Large Snakes; the Sloth | ib. |

| Bay de Atacames | 472 |

| Fresh-water Rivers there | ib. |

| Galapagos: Of the Island Santa Maria de l'Aguada | 473 |

| Tres Marias Islands | 474 |

| Turtle; their Eggs | 475 |

| Natives of California | 476 |

| A Manila Ship taken | 477 |

| A second Manila Ship seen and attacked | 478 |

| The English are beaten off | 479 |

| Natives of Cape San Lucas | 480 |

| Puerto Segura | ib. |

| Captain Rogers departs from the American Coast | 481 |

| Cargoes of his Ships | ib. |

| His bad treatment of Africans who served under him | 482 |

| At Guahan; Sailing Proe | 483 |

| Small low Island | ib. |

| Batavia; Sickness; bad Water | ib. |

| Arrive in the Thames | 484 |

| Of Simon Hatley | ib. |

| Woodes Rogers and Edward Cooke, their Charts | ib. |

| William Dampier | 485 |

| Unembarrassed Style of his Voyages | 486 |

| English South Sea Company | ib. |

CHAP. XI.

Voyages of the French to the South Sea in the years 1709 to 1721, including the Voyage of M. Frezier.

| Page | |

| Frondac, from China to California | 487 |

| Of the position of the Sebald de Weerts | 489 |

| Natives of Tierra del Fuego | ib. |

| Volcano there | 490 |

| Frezier's Voyage | 490 & seq. |

| Island St. Vincent | 491 |

| Island Sta Katalina | 492 |

| Strait le Maire | ib. |

| Natives of Chili; Patagons | 494 |

| His remarks on P. Feuillé | 495 |

| La Concepciou | ib. |

| Natives of Tierra del Fuego | 497 |

| Passage of the St. Barbe | ib. |

| Frezier's Chart | 499 |

| Bay of Coquimbo | 500 |

[page] xvii

| Page | |

| Road of Arica; Guana | 500 |

| Number of Inhabitants in Lima | 501 |

| Island Trinidada | 503 |

| Dr. Halley in answsr to M. Frezier | 504 |

| Pere Feuillée's Preface Critique, and Frezier's Reponse | 505 |

| Reported Discovery in 38° S. latitude | 507 |

| L. G. de la Barbinais | 508 |

| Passion Rock | 512 |

| Quick Passage from China to New Spain | ib. |

| Thaylet, his search for an Island in 10° S. latitude | 513 |

CHAP. XII.

The Asiento Contract. The English South Sea Company. Plan for a Voyage of Discovery proposed by John Welbe. Supposed Discovery of Islands near Japan.

| Page | |

| Asiento Contract. Is given to the English South Sea Company | 514 |

| Charter of the Company | 515 |

| Plan for Discovery of the Terra Australis | 517 |

| Supposed Discovery near Japan | 518 |

| Missionary Survey of China | ib. |

| Korea | ib. |

CHAP. XIII.

Voyage of Captain John Clipperton, and Captain George Shelvocke.

| Page | |

| English Ships with Austrian Commissions | 520 |

| The Commissions changed | 521 |

| The two Ships separate | 522 |

| Proceedings of Shelvocke | 523 & seq. |

| On the Coast of Brasil | 523 |

| Passage round Cape Horne | 526 |

| The Albatross | 527 |

| Narbrough's Island | 529 |

| River of S. Domingo | ib. |

| At the Island Chiloe | ib. |

| At Juan Fernandez | 532 |

| Vale of Arica; Ylo. | 533 |

| Payta plundered and burnt | 534 |

| Shelvocke's Ship wrecked at Juan Fernandez | 535 |

| A new Vessel built there | 538 |

| On the Coast of Chili and Peru | 539 |

| At the Island Quibo | 540 |

| Clipperton and Shelvocke meet | 541 |

| Account of Clipperton's Proceedings | 542 |

| He parts company from Shelvocke, and sails for China | 544 |

| His indiscretion at Guahan | 545 |

| Shelvocke on the Coast of New Spain | 547 |

| At California; Porto Segura | 549 |

| Shelvocke's Isle | 550 |

| Is the Roca Partida of Villalobos | 551 |

| Shelvocke is tried for Piracy | 553 |

| Escapes by want of Evidence | ib. |

| South Sea Bubble | ib. |

VOL. IV. c

[page] xviii

CHAP. XIV.

Voyage round the World by Jacob Roggewein; commonly called the Expedition of Three Ships.

| Page | |

| Departure from Holland | 558 |

| Dorade and Dauphin | 559 |

| John Davis's South Land | ib. |

| Island Mocha | ib. |

| Juan Fernandez | 560 |

| Paaschen, or Easter Island | ib. |

| Roggewein lands there, and kills many of the Natives | 562 |

| Carls-hof Island | 566 |

| Other Islands discovered, and the African Galley wrecked | 567 |

| Schaadelyk, or the Pernicious Islands | ib. |

| Daageraad, or Aurora Island | 569 |

| Abend-roth, or Vespre Island | ib. |

| The Labyrinth Islands | 571 |

| Verquikking, or Recreation Island | ib. |

| Bauman Islands | 575 |

| Other Islands | 577 |

| Tienhoven and Groningen | ib. |

| New Britain | 578 |

| Arimoa and Moa | ib. |

| Roggewein arrives at Batavia | 579 |

| His Ships seized and condemned | ib. |

[page 1]

HISTORY

OF

THE BUCCANEERS

OF

AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

Considerations on the Rights acquired by the Discovery of Unknown Lands, and on the Claims advanced by the Spaniards.

CHAP. 1.

THE Accounts given by the Buccaneers who extended their enterprises to the Pacific Ocean, are the best authenticated of any which have been published by that class of Adventurers. They are interspersed with nautical and geographical descriptions, corroborative of the events related, and more worth being preserved than the memory of what was performed. The materials for this portion of Buccaneer history, which it was necessary should be included in a History of South Sea Navigations, could not be collected without bringing other parts into view; whence it appeared, that with a moderate increase of labour, and without much enlarging the bulk of narrative, a regular history might be formed of their career, from their first rise, to their suppression; and that such a work would not be without its use.

VOL. IV. B

[page] 2

CHAP. 1.

No practice is more common in literature, than for an author to endeavour to clear the ground before him, by mowing down the labours of his predecessors on the same subject. To do this, where the labour they have bestowed is of good tendency, or even to treat with harshness the commission of error where no bad intention is manifest, is in no small degree illiberal. But all the Buccaneer histories that hitherto have appeared, and the number is not small, are boastful compositions, which have delighted in exaggeration: and, what is most mischievous, they have lavished commendation on acts which demanded reprobation, and have endeavoured to raise miscreants, notorious for their want of humanity, to the rank of heroes, lessening thereby the stain upon robbery, and the abhorrence naturally conceived against cruelty.

There is some excuse for the Buccaneer, who tells his own story. Vanity, and his prejudices, without any intention to deceive, lead him to magnify his own exploits; and the reader naturally makes allowances.

The men whose enterprises are to be related, were natives of different European nations, but chiefly of Great Britain and France, and most of them seafaring people, who being disappointed, by accidents or the enmity of the Spaniards, in their more sober pursuits in the West Indies, and also instigated by thirst for plunder as much as by desire for vengeance, embodied themselves, under different leaders of their own choosing, to make predatory war upon the Spaniards. These men the Spaniards naturally treated as pirates; but some peculiar circumstances which provoked their first enterprises, and a general feeling of enmity against that nation on account of their American conquests, procured them the connivance of the rest of the maritime states of Europe, and to be distinguished first by the softened appellations of Freebooters and Adventurers, and afterwards by that of Buccaneers.

[page] 3

CHAP. 1.

Spain, or, more strictly speaking, Castile, on the merit of a first discovery, claimed an exclusive right to the possession of the whole of America, with the exception of the Brasils, which were conceded to the Portuguese. These claims, and this division, the Pope sanctioned by an instrument, entitled a Bull of Donation, which was granted at a time when all the maritime powers of Europe were under the spiritual dominion of the See of Rome. The Spaniards, however, did not flatter themselves that they should be left in the sole and undisputed enjoyment of so large a portion of the newly-discovered countries; but they were principally anxious to preserve wholly to themselves the West Indies: and, such was the monopolising spirit of the Castilians, that during the life of the Queen Ysabel of Castile, who was regarded as the patroness of Columbus's discovery, it was difficult even for Spaniards, not subjects born of the crown of Castile, to gain access to this New World, prohibitions being repeatedly published against the admission of all other persons into the ships bound thither. Ferdinand, King of Arragon, the husband of Ysabel, had refused to contribute towards the outfit of Columbus's first voyage, having no opinion of the probability that it would produce him an adequate return; and the undertaking being at the expence of Castile, the countries discovered were considered as appendages to the crown of Castile.

If such jealousy was entertained by the Spaniards of each other, what must not have been their feelings respecting other European nations? 'Whoever,' says Hakluyt, 'is conversant with the Portugal and Spanish writers, shall find that they account all other nations for pirates, rovers, and thieves, which visit any heathen coast that they have sailed by or looked on.'

Spain considered the New World as what in our law books

B 2

[page] 4

CHAP. 1.

is called Treasure-trove, of which she became lawfully and exclusively entitled to take possession, as fully as if it had been found without any owner or proprietor. Spain has not been singular in her maxims respecting the rights of discoverers. Our books of Voyages abound in instances of the same disregard shewn to the rights of the native inhabitants, the only rightful proprietors, by the navigators of other European nations, who, with a solemnity due only to offices of a religious nature, have continually put in practice the form of taking possession of Countries which to them were new discoveries, their being inhabited or desert making no difference. Not unfrequently has the ceremony been performed in the presence, but not within the understanding, of the wondering natives; and on this formality is grounded a claim to usurp the actual possession, in preference to other Europeans.

Nothing can be more opposed to common sense, than that strangers should pretend to acquire by discovery, a title to countries they find with inhabitants; as if in those very inhabitants the right of prior discovery was not inherent. On some occasions, however, Europeans have thought it expedient to acknowledge the rights of the natives, as when, in disputing each other's claims, a title by gift from the natives has been pretended.

In uninhabited lands, a right of occupancy results from the discovery; but actual and bonâ fide possession is requisite to perfect appropriation. If real possession be not taken, or if taken shall not be retained, the right acquired by the mere discovery is not indefinite and a perpetual bar of exclusion to all others; for that would amount to discovery giving a right equivalent to annihilation. Moveable effects may be hoarded and kept out of use, or be destroyed, and it will not always be easy to prove whether with injury or benefit to mankind: but

[page] 5

CHAP. 1.

the necessities of human life will not admit, unless under the strong hand of power, that a right should be pretended to keep extensive and fertile countries waste and secluded from their use, without other reason than the will of a proprietor or claimant.

Particular local circumstances have created objections to the occupancy of territory: for instance, between the confines of the Russian and Chinese Empires, large tracts of country are left waste, it being held, that their being occupied by the subjects of either Empire would affect the security of the other. Several similar instances might be mentioned.

There is in many cases difficulty to settle what constitues occupancy. On a small Island, any first settlement is acknowledged an occupancy of the whole; and sometimes, the occupancy of a single Island of a group is supposed to comprehend an exclusive title to the possession of the remainder of the group. In the West Indies, the Spaniards regarded their making settlements on a few Islands, to be an actual taking possession of the whole, as far as European pretensions were concerned.

The first discovery of Columbus set in activity the curiosity and speculative dispositions of all the European maritime Powers. King Henry the VIIth, of England, as soon as he was certified of the existence of countries in the Western hemisphere, sent ships thither, whereby Newfoundland, and parts of the continent of North America, were first discovered. South America was also visited very early, both by the English and the French; 'which nations,' the Historian of Brasil remarks, 'had neglected to ask a share of the undiscovered World, when Pope Alexander the Vlth partitioned it, who'would as willingly have drawn two lines as one; and, because they derived no advantage from that partition, refused to

[page] 6

CHAP. 1.

admit its validity.' The West Indies, however, which doubtless was the part most coveted by all, seem to have been considered. as more particularly the discovery and right of the Spaniards; and, either from respect to their pretensions, or from the opinion entertained of their force in those parts, they remained many years undisturbed by intruders in the West Indian Seas. But their homeward-bound, ships, and also those of the Portuguese from the East Indies, did not escape being molested by pirates; sometimes by those of their own, as well as of other nations.

[page] 7

CHAP. II.

Review of the Dominion of the Spaniards in Hayti or Hispaniola.

CHAP. 2.

1492–3.

Hayti, or Hispaniola, the first Settlement of the Spaniards in America.

THE first settlement formed by the Castilians in their newly discovered world, was on the Island by the native inhabitants named Hayti; but to which the Spaniards gave the name of Española or Hispaniola. And in process of time it came to pass, that this same Island became the great place of resort, and nursery, of the European adventurers, who have been so conspicuous under the denomination of the Buccaneers of America.

The native inhabitants found in Hayti, have been described a people of gentle, compassionate dispositions, of too frail a constitution, both of body and mind, either to resist oppression, or to support themselves under its weight; and to the indolence, luxury, and avarice of the discoverers, their freedom and happiness in the first instance, and finally their existence, fell a sacrifice.

Queen Ysabel, the patroness of the discovery, believed it her duty, and was earnestly disposed, to be their protectress; but she wanted resolution to second her inclination. The Island abounded in gold mines. The natives were tasked to work them, heavier and heavier by degrees; and it was the great misfortune of Columbus, after achieving an enterprise, the glory of which was not exceeded by any action of his contemporaries, to make an ungrateful use of the success Heaven had favoured him with, and to be the foremost in the destruction of the nations his discovery first made known to Europe.

[page] 8

CHAP. 2.

Review of the Dominion of the Spaniards in Hispaniola.

The population of Hayti, according to the lowest estimation made, amounted to a million of souls. The first visit of Columbus was passed in a continual reciprocation of kind offices between them and the Spaniards. One of the Spanish ships was wrecked upon the coast, and the natives gave every assistance in their power towards saving the crew, and their effects to them. "When Columbus departed to return to Europe, he left behind him thirty-eight Spaniards, with the consent of the Chief or Sovereign of the part of the Island where he had been so hospitably received. He had erected a fort for their security, and the declared purpose of their remaining was to protect the Chief against all his enemies. Several of the native Islanders voluntarily embarked in the ships to go to Spain, among whom was a relation of the Hayti Chief; and with them were taken gold, and various samples of the productions of the New World.

Columbus, on his return, was received by the Court of Sperm with the honours due to his heroic achievement, indeed with honours little short of adoration: he was deelared Admiral, Governor, and Viceroy of the Countries that he had discovered, and also of those which he should afterwards discover; he was ordered to assume the style and title of nobility; and was furnished with a larger fleet to prosecute farther the discovery, and to make conquest of the new lands. The Instructions for his second expedition contained the following direction: 'Forasmuch as you, Christopher Columbus, are going by our command, with our vessels and our men, to discover and subdue certain Islands and Continent, our will is, that you shall be our Admiral, Viceroy, and Governor in them.' This was the first step in the iniquitous usurpations which the more cultivated nations of the world have practised upon their weaker brethren, the natives of America.

[page] 9

CHAP. 2.

1493.

Government of Columbus.

1494.

Thus provided and instructed, Columbus sailed on his second voyage. On arriving at Hayti, the first news he learnt was, that the natives had demolished the fort which he had built, and destroyed the garrison, who, it appeared, had given great provocation, by their rapacity and licentious conduct. War did not immediately follow. Columbus accepted presents of gold from the Chief; he landed a number of colonists, and built a town on the North side of Hayti, which he named after the patroness, Ysabel, and fortified. A second fort was soon built; new Spaniards arrived; and the natives began to understand that it was the intention of their visitors to stay, and be lords of the country. The Chiefs held meetings, to confer on the means to rid themselves of such unwelcome guests, and there was appearance of preparation making to that end. The Spaniards had as yet no farther asserted dominion, than in taking land for their town and forts, and helping themselves to provisions when the natives neglected to bring supplies voluntarily. The histories of these transactions affect a tone of apprehension on account of the extreme danger in which the Spaniards were, from the multitude of the heathen inhabitants; but all the facts shew that they perfectly understood the helpless character of the natives. A Spanish officer, named Pedro Margarit, was blamed, not altogether reasonably, for disorderly conduct to the natives, which happened in the following manner. He was ordered, with a large body of troops, to make a progress through the Island in different parts, and was strictly enjoined to restrain his men from committing any violence against the natives, or from giving them any cause for complaint. But the troops were sent on their journey without provisions, and the natives were not disposed to furnish them. The troops recurred to violence, which they did not limit to the obtaining food. If Columbus could spare a detachment strong enough to make

VOL. IV. C

[page] 10

CHAP. 2.

1494.

1495.

Dogs used in Battle against the Indians.

such a visitation through the land, he could have entertained no doubt of his ability to subdue it. But before he risked engaging in open war with the natives, he thought it prudent to weaken their means of resisting by what he called stratagem. Hayti was divided into five provinces, or small kingdoms, under the separate dominion of as many Princes or Caciques. One of these, Coanabo, the Cacique of Maguana, Columbus believed to be more resolute, and more dangerous to his purpose, than any other of the chiefs. To Coanabo, therefore, he sent an Officer, to propose an accommodation on terms which appeared so reasonable, that the Indian Chief assented to them. Afterwards, relying on the good faith of the Spaniards, not, as some authors have meanly represented, through credulous and childish simplicity, but with the natural confidence which generally prevails, and which ought to prevail, among mankind in their mutual engagements, he gave opportunity for Columbus to get possession of his person, who caused him to be seized, and embarked in a ship then ready to sail for Spain. The ship foundered in the passage. The story of Coanabo, and the contempt with which he treated Columbus for his treachery, form one of the most striking circumstances in the history of the perfidious dealings of the Spaniards in America. On the seizure of this Chief, the Islanders rose in arms. Columbus took the field with two hundred foot armed with musketry and cross-bows, with twenty troopers mounted on horses, and with twenty large dogs*!

It is not to be urged in exculpation of the Spaniards, that the natives were the aggressors, by their killing the garrison left at Hayti. Columbus had terminated his first visit in friendship; and, without the knowledge that any breach had happened between the Spaniards left behind, and the natives, sentence

* Lebreles de pressa.

[page] 11

CHAP. 2.

1495.

of subjugation had been pronounced against them. This was not to avenge injury, for the Spaniards knew not of any committed. Columbus was commissioned to execute this sentence and for that end, besides a force of armed men, he tools with, him from Spain a number of blood-hounds, to prosecute a most unrighteous purpose by the most inhuman means.

Many things are justifiable in defence, which in offensive war are regarded by the generality of mankind with detestation. All are agreed in the use of dogs, as faithful guards to oui persons as well as to our dwellings; but to hunt men with dogs seems to have been till then unheard of, and is nothing less offensive to humanity than cannibalism or feasting on our enemies. Neither jagged shot, poisoned darts, springing of mines, nor any species of destruction, can be objected to, if this is allowed in honourable war, or admitted not to be a disgraceful practice in any war.

Massacre of the Natives, and Subjugation of the Island.

It was scarcely possible for the Indians, or indeed for any people naked and undisciplined, however numerous, to stand their ground against a force so calculated to excite dread. The Islanders were naturally a timid people, and they regarded fire-arms as engines of more than mortal contrivance. Don Ferdinand, the son of Columbus, who wrote a History of his father's actions, relates an instance, which happened before the war, of above 400 Indians running away from a single Spanish horseman. So little was attack, or valiant opposition, apprehended from the natives, that Columbus divided his force into several squadrons, to charge them at different points. 'These faint-hearted creatures,' says Don Ferdinand, 'fled at the first onset; and our men, pursuing and killing them, made such havock, that in a short time they obtained a complete victory.' The policy adopted by Columbus was, to confirm the natives in their dread of European arms, by a terrible

C 2

[page] 12

CHAP. 2.

1495.

Tribute imposed.

execution. The victors, both dogs and men, used their ascendancy like furies. The dogs flew at the throats of the Indians, and strangled or tore them in pieces; whilst the Spaniards, with the eagerness of hunters, pursued and mowed down the unresisting fugitives. Some thousands of the Islanders were slaughtered, and those taken prisoners were consigned to servitude. If the fact were not extant, it would not be conceivable that any one could be so blind to the infamy of such a proceeding, as to extol the courage of the Spaniards on this occasion, instead of execrating their cruelty. Three hundred of the natives were shipped for Spain as slaves, and the whole Island, with the exception of a small part towards the Western coast, which has since been named the Cul de Sac, was subdued. Columbus made a leisurely progress through the Island, which occupied him nine or ten months, and imposed a tribute generally upon all the natives above the age of fourteen, requiring each of them to pay quarterly a certain quantity of sold, or 25 lbs. of cotton. Those natives who were discovered to have been active against the Spaniards, were taxed higher. To prevent evasion, rings or tokens, to be produced in the nature of receipts, were given to the Islanders on their paying the tribute, and any Islander found without such a mark in his possession, was deemed not to have paid, and proceeded against.

Queen Ysabel shewed her disapprobation of Columbus's proceedings, by liberating and sending back the captive Islanders to their own country; and she moreover added her positive commands, that none of the natives should be made slaves. This order was accompanied with others intended for their protection; but the Spanish Colonists, following the example of their Governor, contrived means to evade them.

In the mean time, the Islanders could not furnish the tribute, and Columbus was rigorous in the collection. It is

[page] 13

CHAP. 2.

1495.

said in palliation, that he was embarrassed in consequence of the magnificent descriptions he had given to Ferdinand and Ysabel, of the riches of Hispaniola, by which he had taught them to expect much; and that the fear of disappointing them and losing their favour, prompted him to act more oppressively to the Indians than his disposition otherwise inclined him to do Distresses of this kind press upon all men; but only in very ordinary minds do they outweigh solemn considerations. Setting aside the dictates of religion and moral duty, as doubtless was done, and looking only to worldly advantages, if Columbus had properly estimated his situation, he would have been resolute not to descend from the eminence he had attained. The dilemma in which he was placed, was simply, whether he would risk some diminution of the favour he was in at Court, by being the protector of these Islanders, who, by circumstances peculiarly calculated to engage his interest, were entitled in an especial manner to have been regarded as his clients; or, to preserve that favour, would oppress them to their destruction, and to the ruin of his own fame.

Despair of the Natives.

The Islanders, finding their inability to oppose the invaders, took the desperate resolution to desist from the cultivation of their lands, to abandon their houses, and to withdraw themselves to the mountains; hoping thereby that want of subsistence would force their oppressors to quit the Island. The Spaniards had many resources; the sea-coast supplied them with fish, and their vessels brought provisions from other islands. As to the natives of Hayti, one third part of them, it is said, perished in. the course of a few months, by famine and by suicide. The rest returned to their dwellings, and submitted. All these events took place within three years after the discovery; so active is rapacity.

Some among the Spaniards (authors of that time say, the

[page] 14

CHAP. 2.

1495.

1496.

enemies of Columbus, as if sentiments of humanity were not capable of such an effort) wrote Memorials to their Catholic Majesties, representing the disastrous condition to which the natives were reduced. Commissioners were sent to examine into the fact, and Columbus found it necessary to go to Spain, to defend his administration.

So great was the veneration and respect entertained for him, that on his arrival at Court, accusation was not allowed to be produced against him: and, without instituting enquiry, it was arranged, that he should return to his government with a large reinforcement of Spaniards, and with authority to grant lands to whomsoever he chose to think capable of cultivating them. Various accidents delayed his departure from Spain on his third voyage, till 1498.

City of Nueva Ysabel founded, 1496

Its name changed to Santo Domingo.

He had left two of his brothers to govern in Hispaniola during his absence; the eldest, Bartolomé, with the title of Adelantado; in whose time (A.D. 1496) was traced, on the South side of the Island, the plan of a new town intended for the capital, the land in the neighbourhood of the town of Ysabel, before built, being poor and little productive. The name first given to the new town was Nueva Ysabel; this in a short time gave place to that of Santo Domingo, a name which was not imposed by authority, but adopted and became in time established by common usage, of which the original cause is not now known*.

Under the Adelantado's government, the parts of the Island which till then had held out in their refusal to receive the Spanish yoke, were reduced to subjection; and the conqueror gratified his vanity with the public execution of one of the Hayti Kings.

* The name Saint Domingo was afterwards applied to the whole Island by the French, who, whilst they contested the possession with the Spaniards, were desirous to supersede the use of the name Espanola or Hispaniola.

[page] 15

CHAP. 2.

1496.

1498.

Columbus whilst he was in Spain received mortification in two instances, of neither of which he had any right to complain. In October 1496, three hundred natives of Hayti (made prisoners by the Adelantado) were landed at Cadiz, being sent to Spain as slaves. At this act of disobedience, the King and Queen strongly expressed their displeasure, and said, if the Islanders made war against the Castilians, they must have been constrained to do it by hard treatment. Columbus thought proper to blame, and to disavow what his brother had done. The other instance of his receiving mortification, was an act of kindness done him, and so intended; and it was the only shadow of any thing like reproof offered to him. In the instructions which he now received, it was earnestly recommended to him to prefer conciliation to severity on all occasions which would admit it without prejudice to justice or to his honour.

It was in the third voyage of Columbus that he first saw the Continent of South America, in August 1498, which he then took to be an Island, and named Isla Santa. He arrived on the 22d of the same month at the City of San Domingo.

1498–9.

The short remainder of Columbus's government in Hayti was occupied with disputes among the Spaniards themselves. A strong party was in a state of revolt against the government of the Columbuses, and accommodation was kept at a distance, by neither party daring to place trust in the other. Columbus would have had recourse to arms to recover his authority, but some of his troops deserted to the disaffected, and others refused to be employed against their countrymen. In this state, the parties engaged in a treaty on some points, and each sent Memorials to the Court. The Admiral in his dispatches represented, that necessity had made him consent to certain conditions, to avoid endangering the Colony; but that it would

[page] 16

CHAP. 2.

1498–9.

be highly prejudicial to the interests of their Majesties to ratify the treaty he had been forced to subscribe.

Beginning of the Repartimientos.

The Admiral now made grants of lands to Spanish colonists, and accompanied them with requisitions to the neighbouring Caciques, to furnish the new proprietors with labourers to cultivate the soil. This was the beginning of the Repartimientos, or distributions of the Indians, which confirmed them slaves, and contributed, more than all former oppressions, to their extermination. Notwithstanding the earnest and express order of the King and Queen to the contrary, the practice of transputting the natives of Hayti to Spain as slaves, was connived at and continued; and this being discovered, lost Columbus the confidence, but not wholly the support, of Queen Ysabel.

1500. Government of Bovadilla.

The dissensions in the Colony increased, as did the unpopularity of the Admiral; and in the year 1500, a new Governor General of the Indies, Francisco de Bovadilla, was sent from Spain, with a commission empowering him to examine into the accusations against the Admiral; and he was particularly enjoined by the Queen, to declare all the native inhabitants free, and to take measures to secure to them that they should be treated as a free people. How a man so grossly ignorant and intemperate as Bovadilla, should have been chosen to an office of such high trust, is not a little extraordinary. His first display of authority was to send the Columbuses home prisoners, with the indignity to their persons of confining them in chains. He courted popularity in his government by shewing favour to all who had been disaffected to the government or measures of the Admiral and his brothers, the natives excepted, for whose relief he had been especially appointed Governor. To encourage the Spaniards to work the mines, he reduced the duties payable to the Crown on the produce, and trusted to an increase in the quantity of gold extracted, for preserving the revenue from

[page] 17

CHAP. 2.

1500. All the Natives compelled to work the Mines.

diminution. This was to be effected by increasing the labour of the natives; and that these miserable people might not evade their servitude, he caused muster-rolls to be made of all the inhabitants, divided them into classes, and made distribution of them according to the value of the mines, or to his desire to gratify particular persons. The Spanish Colonists believed that the same facilities to enrich themselves would not last long, and made all the haste in their power to profit by the present opportunity.

By these means, Bovadilla drew from the mines in a few months so great a quantity of gold, that one fleet which he sent home, carried a freight more than sufficient to reimburse Spain all the expences which had been incurred in the discovery and conquest. The procuring these riches was attended with so great a mortality among the natives as to threaten their utter extinction.

Nothing could exceed the surprise and indignation of the Queen, on receiving information of these proceedings. The bad government of Bovadilla was a kind of palliation which had the effect of lessening the reproach upon the preceding government, and, joined to the disgraceful manner in which Columbus had been sent home, produced a revolution of sentiment in his favour. The good Queen Ysabel wished to compensate him for the hard treatment he had received, at the same time that she had the sincerity to make him understand she would not again commit the Indian natives to his care. All his other offices and dignities were restored to him.

1501–2. Nicolas Ovando, Governor.

For a successor to Bovadilla in the office of Governor General, Don Nicolas Ovando, a Cavalero of the Order of Alcantara, was chosen; a man esteemed capable and just, and who entered on his government with apparent mildness and consideration. But in a short time he proved the most execrable

VOL. IV. D

[page] 18

CHAP. 2.

1501–2.

of all the tyrants, 'as if,' says an historian, 'tyranny was inherent and contagious in the office, so as to change good men to bad, for the destruction of these unfortunate Indians.'

In obedience to his instructions, Ovando, on arriving at his government, called a General Assembly of all the Caciques or principal persons among the natives, to whom he declared, that their Catholic Majesties took the Islanders under their royal protection; that no exaction should be made on them, other than the tribute which had been heretofore imposed; and that no person should be employed to work in the mines, except on the footing of voluntary labourers for wages.

1502. Working the Mines discontinued by Orders from Spain.

On the promulgation of the royal pleasure, all working in the mines immediately ceased. The impression made by their past sufferings was too strong for any offer of pay or reward to prevail on them to continue in that work. [The same thing happened, many years afterwards, between the Chilesc and the Spaniards.] A few mines had been allowed to remain in possession of some of the Caciques of Hayti, on the condition of rendering up half the produce; but now, instead of working them, they sold their implements. In consequence of this defection, it was judged expedient to lower the royal duties on the produce of the mines, which produced some effect.

Ovando, however, was intent on procuring the mines to be worked as heretofore, but proceeded with caution. In his dispatches to the Council of the Indies, he represented in strong colours the natural levity and inconstancy of the Indians, and their idle and disorderly manner of living; on which account, he said, it would be for their improvement and benefit to find them occupation in moderate labour; that there would be no injustice in so doing, as they would receive wages for their work, and they would thereby be enabled to

[page] 19

CHAP. 2.

1502.

pay the tribute, which otherwise, from their habitual idleness, many would not be able to satisfy. He added moreover, that the Indians, being left entirely their own masters, kept at a distance from the Spanish habitations, which rendered it impossible to instruct them in the principles of Christianity.

This reasoning, and the proposal to furnish the natives with employment, were approved by the Council of the Indies; and the Court, from the opinion entertained of the justice and moderation of Ovando, acquiesced so far as to trust making the experiment to his discretion. In reply to his representations, he received instructions recommending, 'That if it was necessary to oblige the Indians to work, it should be done in the most gentle and moderate manner; that the Caciques should be invited to send their people in regular turns; and that the employers should treat them well, and pay them wages, according to the quality of the person and nature of the labour; that care should be taken for their regular attendance at religious service and instruction; and that it should be remembered they were a free people, to be governed with mildness, and on no account to be treated as slaves.'

1502–3. The Natives again forced to the Mines.

These directions, notwithstanding the expressions of care for the natives contained in them, released the Governor General from all restriction. This man had recently been appointed Grand Master of the order of Calatrava, and thenceforward he was most generally distinguished by the appellation or title of the Grand Commander.

A transaction of a shocking nature, which took place during Bovadilla's government, caused an insurrection of the natives; but which did not break out till after the removal of Bovadilla. A Spanish vessel had put into a port of the province of Higuey (the most Eastern part of Hayti) to procure a lading of cassava,

D 2

[page] 20

CHAP. 2.

1502–3.

Severities shewn to the people of Higuey.

a root which is used as bread. The Spaniards landed, Having with them a large dog held by a cord. Whilst the natives were helping them to what they wanted, one of the Spaniards in wanton insolence pointed to a Cacique, and called to the dog in manner of setting him on. The Spaniard who held the cord, it is doubtful whether purposely or by accident, suffered it to slip out of his hand, and the dog instantly tore out the unfortunate Cacique's entrails. The people of Higuey sent a deputation, to complain to Bovadilla; but those who went could not obtain attention. In the beginning of Ovando's government, some other Spaniards landed at the same port of Higuey, and the natives, in revenge for what had happened, fell upon them, and killed them; after which they took to arms. This insurrection was quelled with so great a slaughter, that the province, from having been well peopled, was rendered almost a desert.

1503. Encomiendas established.

Ovando, on obtaining his new instructions, followed the model set by his predecessors. He enrolled and classed the natives in divisions, called Repartimientos: from these he assigned to the Spanish proprietors a specified number of labourers, by grants, which, with most detestable hypocrisy, were denominated Encomiendas. The word Encomienda signifies recommendation, and the employer to whom the Indian was consigned, was to have the reputation of being his patron. The Encomienda was conceived in the. following terms:—' I recommend to A. B. such and such Indians (listed by name) the subjects of such Cacique; and he is to take care to have them instructed in the principles of our holy faith.

Under the enforcement of the encomiendas, the natives were again dragged to the mines; and many of these unfortunate wretches were kept by their hard employers under ground for six months together. With the labour, and grief at being

[page] 21

CHAP. 2.

1503. African Slaves carried to the West Indies.

again doomed to slavery, they sunk so rapidly, that it suggested to the murderous proprietors of the mines the having recourse to Africa for slaves. Ovando, after small experience of this practice, endeavoured to oppose it as dangerous, the Africans frequently escaping from their masters, and finding concealment among the natives, in whom they excited some spirit of resistance.

The ill use made by the Grand Commander of the powers with which he had been trusted, appears to have reached the Court early, for, in 1503, he received fresh orders, enjoining him not to allow, on any pretext, the natives to be employed in labour against their own will, either in the mines or elsewhere. Ovando, however, trusted to being supported by the Spanish proprietors of the mines within his government, who grew rich by the encomiendas, and with their assistance he found pretences for not restraining himself to the orders of the Court.

In parts of the Island, the Caciques still enjoyed a degree of authority over the natives, which rested almost wholly on habitual custom and voluntary attachment. To loosen this band, Ovando, assuming the character of a protector, published ordonnances to release the lower classes from the oppressions of the Caciques; but from those of their European taskmasters he gave them no relief.

Some of the principal among the native inhabitants of Xaragua, the South-western province of Hayti, had the hardiness openly to express their discontent at the tyranny exercised by the Spaniards established in that province. The person at this time regarded as Cacique or Chief of Xaragua was a female, sister to the last Cacique, who had died without issue. The Spanish histories call her Queen of Xaragua. This Princess had shewn symptoms of something like abhorrence of the Spaniards near her, and they did not fail to send repre-

[page] 22

CHAP. 2.

1503.

1503–4.

Massacre of the people of Xaragua.

sentations to the Grand Commander, with the addition, that there appeared indications of an intention in the Xaraguans to revolt. On receiving this notice, Ovando determined that Xaragua, as Higuey had before, should feel the weight of his displeasure. Putting himself at the head of 370 Spanish troops, part of them cavalry, he departed from the city of San Domingo for the devoted province, giving out publicly, that his intention was to make a progress into the West, to collect the tribute, and to visit the Queen of Xaragua. He was received by the Princess and her people with honours, feastings, and all the demonstrations of joy usually acted by terrified people with the hopes of soothing tyranny; and the troops were regaled with profusion of victuals, with dancing, and shows. After some days thus spent, Ovando invited the Princess, her friends and attendants, to an entertainment which he promised them, after the manner of Spain. A large open public building was the chosen place for holding this festival, and all the Spanish settlers in the province were required to attend. A great concourse of Indians, besides the bidden guests, crowded round, to enjoy the spectacle. As the appointed time approached, the Spanish infantry gradually appeared, and took possession of all the avenues; which being secured, this Grand Commander himself appeared, mounted at the head of his cavalry; and on his making a signal, which had been previously concerted, which was laying his hand on the Cross of his Order, the whole of these diabolical conquerors fell upon the defenceless multitude, who were so hemmed in, that thousands were slaughtered, and it was scarcely possible for any to escape unwounded. Some of the principal Indians or Caciques, it is said, were by the Commander's order fastened to the pillars of the building, where they were questioned, and made to confess themselves in a conspiracy against the Spanish government; after which

[page] 23

CHAP. 2.

1503–4.

1504.

confession the building was set on fire, and they perished in the flames. The massacre did not stop here. Detachments of troops, with dogs, were sent to hunt and destroy the natives in different parts of the province, and some were pursued over to the Island Gonave. The Princess was carried bound to the city of San Domingo, and with the forms of law was tried, condemned, and put to death.

The purposes, besides that of gratifying his revenge for the hatred shewn to his government, which were sufficient to move Ovando to this bloody act, were, the plunder of the province, and the reduction of the Islanders to a more manageable number, and to the most unlimited submission. Some of the Indians fled to the mountains. 'But,' say the Spanish Chronicles of these events, 'in a short time their Chiefs were taken and punished, and at the end of six months there was not a native living on the Island who had not submitted to the dominion of the Spaniards.'

Death of Queen Ysabel.

Queen Ysabel died in November 1504, much and universally lamented. This Princess bore a large share in the usurpations practised in the New World; but it is evident she was carried away, contrary to her real principles and disposition, which were just and benevolent, and to her own happiness, by the powerful stream of general opinion.

In Europe, political principles, or maxims of policy, have been in continual change, fashioned by the nature of the passing events, no less than dress has been by caprice; causes which have led one to deviate from plain rectitude, as the other from convenience. One principle, covetousness of the attainment of power, has nevertheless constantly predominated, and has derided and endeavoured to stigmatize as weakness and imbecility, the stopping short of great acquisitions, territorial especially, for moral considerations. Queen Ysabel lived surrounded by a

[page] 24

CHAP. 2.

1504.

world of such politicians, who were moreover stimulated to avarice by the prospect of American gold; a passion which yet more than ambition is apt to steel the heart of man against the calls of justice and the distresses of his fellow creatures, If Ysabel had been endued with more than mortal fortitude, she might have refused her sanction to the usurpations, but could not have prevented them. On her death bed she earnestly recommended to King Ferdinand to recal Ovando. Ovando, however, sent home much gold, and Ferdinand referred to a distant time the fulfilment of her dying request.

1506.