[page i]

A

VOYAGE

TO

SOUTH AMERICA:

DESCRIBING AT LARGE

THE SPANISH CITIES, TOWNS, PROVINCES, &c.

ON THAT

EXTENSIVE CONTINENT:

UNDERTAKEN, BY COMMAND OF THE KING OF SPAIN,

BY

DON GEORGE JUAN,

AND

DON ANTONIO DE ULLOA,

CAPTAINS OF THE SPANISH NAVY,

FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON,

MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL ACADEMY AT PARIS, &c. &c.

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL SPANISH:

WITH

NOTES AND OBSERVATIONS: AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE

BRAZILS.

BY JOHN ADAMS, ESQ. OF WALTHAM ABBEY;

Who resided several Years in those Parts.

THE FOURTH EDITION.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR JOHN STOCKDALE, PICCADILLY; R. FAULDER, BOND-STREET; LONGMAN AND CO. PATER-NOSTER ROW; LACKINGTON AND CO. FINSBURY SQUARE; AND J. HARDING, ST. JAMES'S STREET.

1806.

[page ii]

[page iii]

CONTENTS

OF

VOLUME THE SECOND.

BOOK VII.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | JOURNEY from Quito to Truxillo. | 1 |

| II. | Arrival at Truxillo. Description of that city. Continuation of journey to Lima. | 19 |

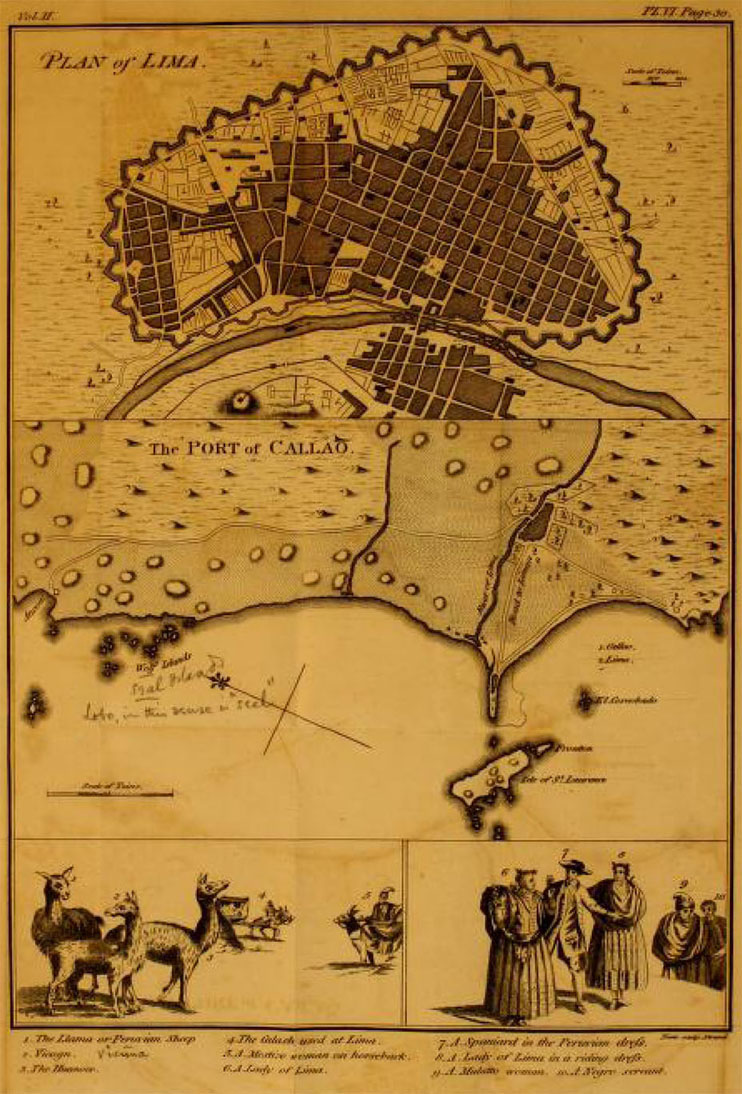

| III. | Account of the city of Lima. | 29 |

| IV. | Of the public entrance, &c. of the Vice-roy. | 46 |

| V. | Of the inhabitants of Lima. | 52 |

| VI. | Of the climate of the city of Lima, and of the whole country of Valles. Divisions of the seasons. | 64 |

| VII. | Inconveniences, distempers, and evils to which the city of Lima is subject, particularly earthquakes. | 79 |

| VIII. | Fertility and cultivation. | 94 |

| IX. | Of the plenty of provisions at Lima. | 102 |

| X. | Trade and commerce of Lima. | 107 |

| XI. | Jurisdiction of the Vice-roy of Peru. Of the audiences, and diocesses of that kingdom. | 113 |

| XII. | Of the provinces in Truxillo, Guamanga, Cusco, and Arequipa. | 127 |

| XIII. | Of the audience of Charcas. Jurisdictions and sees in that archbishopric. | 142 |

| XIV. | Account of the three diocesses of La Pas, Sant Cruz de la Sierra, and Tucuman, and of their respective provinces. | 157 |

| XV. | Account of Paraguay and Buenos Ayres. Of the missions of the Jesuits established in the former, their government and police. | 170 |

BOOK VIII.

| I. | Voyage from Callao to Paita, thence to Guayaquil, and to Quito. Description of Paita. | 191 |

| II. | Transactions at Quito. Unhappy occasion of a sudden return to Guayaquil. Second journey to Lima. | 197 |

[page iv]

| III. | Voyage to Juan Fernandes. Account of the seas and winds in that passage. | 206 |

| IV. | Account of Juan Fernandes. Voyage to Santa Maria. Thence to the bay of Conception. Nautical remarks. | 219 |

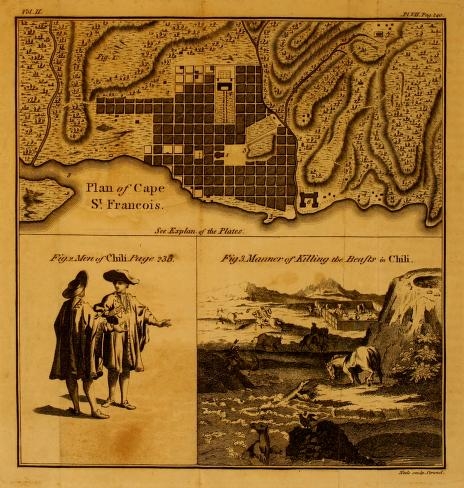

| V. | Description of the city of Conception, in the kingdom of Chili. Ravages it has suffered from Indians. Commerce and fertility. | 234 |

| VI. | Description of Conception bay; its roads or harbours, fish, &c.; singular mines of shells in its neighbourhood. | 248 |

| VII. | Description of the city of Santiago. | 255 |

| VIII. | Account of that part of the kingdom of Chili within the jurisdiction of the audience of Santiago. | 260 |

| IX. | Commerce of Chili. Harmony with the wild Indians. | 270 |

| X. | Voyage to the island of Juan Fernandes. Thence to Valparaiso. | 282 |

| XI. | Voyage to Callao. Second return to Quito, third journey to Lima. | 288 |

BOOK IX.

| I. | Departure from Callao. Arrival at Conception. Voyage to the island of Fernando de Norona. | 295 |

| II. | Nautical observations in the Voyage round Cape Horn. | 308 |

| III. | Description of Fernando de Norona. | 319 |

| Account of some parts of the Brazils, hitherto unknown to the English nation. By Mr. Adams. | 329 | |

| IV. | Voyage from Fernando de Norona. Engagement with two English privateers. | 336 |

| V. | Voyage of the Delivrance to Louisbourg, where she was taken. Nautical remarks on the passage. | 345 |

| VI. | Don George Juan's Voyage from La Conception to Guarico, thence to Brest. His return to Madrid. | 357 |

| VII. | Account of the harbour and town of Louisbourg, and of its being taken by the English. Of the French fishery, and the trade carried on there. | 373 |

| VIII. | The colony of Boston; its rise, progress, and other particulars. | 390 |

| IX. | Voyage from Louisbourg to Newfoundland. Account of that island and cod-fishery. Voyage to England. | 398 |

[page 1]

A

VOYAGE

TO

SOUTH AMERICA.

BOOK VII.

Account of our Journey to Lima; with a Description of the Towns and Settlements on the Road, and of the City of Lima.

CHAP. I

Journey from Quito to Truxillo.

THE accidents to which human enterprizes and attempts are generally exposed, direct, with an inconstant but wonderful harmony, the series of our actions and adventures, and introduce among them a great variety of alterations and changes. It is this variety, which in vegetation embellishes nature, and equally displays the glory and wisdom of the Supreme Creator in the political and rational world; where we admire the surprizing diversity of events, the infinity of human actions,

VOL. II. B

[page] 2

and the different schemes and consequences in politics, the successive chain of which renders history so delightful, and, to a reflecting mind, so instructive. The inconstancy so often seen in things the most solid and stable, is generally one of the most powerful obstacles, to the advantages which might otherwise be derived from works of any duration. However great they are, either in reality, or idea, the perfection of them is not only impeded by the vicissitudes of time, and the inconstancy of things, but they even decline, and fall into ruins: some, thro' want of proper support and encouragement; while others, from the mind being wearied out by delays, difficulties, and a thousand embarrassments, are abandoned; the imagination being no longer able to pursue its magnificent scheme.

To measure some degrees of the meridian near the equator, the principal intention of our voyage, if considered only in idea, and abstractedly from the difficulties which attended its execution, must appear easy, and as requiring no great length of time; but experience convinced us, that a work of such importance to the improvement of science, and the interest of all nations, was not to be performed without delays, difficulties and dangers; which demanded attention, accuracy, and perseverance. Besides the difficulties necessarily attending the requisite accuracy of these observations, the delays we were obliged to make in order to take them in the most favourable seasons, the intervening clouds, the Paramos, and disposition of the ground, were so many obstacles to our making any tolerable dispatch; and these delays filled us with apprehensions, that if any other accidents should happen, the whole design would be rendered abortive, or at least, suffer a long interruption.

It has already been observed that while we were at Cuença, finishing our astronomical observations in that extremity of the arch of the meridian, we un-

[page] 3

expectedly received a letter from the marquis de Villa Garcia, vice-roy of Peru, desiring us to come with all speed to his capital: any delay on our part might have been improper; and we were solicitous not to merit an accusation of the least remissness in his majesty's service. Thus we were under a necessity of suspending our observations for some time;* though all that remained was the second astronomical observation, northward, where the series of our triangles terminated.

THE occasion of this delay, arose from an account, received by the vice-roy, that war being declared between Spain and England, the latter was sending a considerable fleet on some secret designs into those seas. Several precautions had been taken to defeat any attempt; and the vice-roy, being pleased to conceive that we might be of some use to him in acquitting himself with honour on this occasion, committed to us the execution of some of his measures; giving us to understand, that the choice he made of us, was the most convincing proof of the high opinion he entertained of our abilities; and indeed our obligations were the greater, as the distance of four hundred leagues had not obliterated us from his remembrance, of which he now gave us so honourable a proof.

ON the 24th of September, 1740, the vice-roy's letter was delivered to us, and we immediately repaired to Quito, in order to furnish ourselves with necessaries for the journey.

EVERY thing being performed, we set out from that city on the 30th of October, and determined to go by Guaranda and Guayaquil; for tho' there is a road by land thro' Cuença and Loja, yet the other seemed to us the most expeditious, as the ways are neither so bad, nor mules and other beasts of carriage so difficult to be met with. The long stays in villages

* Vol. 1. Book V. Chap. II.

B 2

[page] 4

were here also little to be apprehended, which are frequently rendered necessary in the other road by inundations, rivers, and precipices.

ON the 30th of October we reached the Bodegas, or warehouses, of Babayoho, where taking a canoo we went down the river to Guayaquil; and embarking on board a small ship bound for Puna,. we anchored in that port November the 3d. At this place we hired a large balza, which brought us through the gulph to Machala. For though the usual route is by the Salto de Tumbez, we were obliged to alter our course, the pilot not being well acquainted with, the entrance of a creek, through which you pass to the Salta.

ON the 5th in the morning our balza landed us on the coast of Machala, from whence we travelled by land to the town, the distance being about two short leagues. The next day we sent away our baggage in a large canoo to the Salto de Tumbez; going myself in the same canoo, being disabled by a fall the preceding day. Don George Juan, with the servants, followed on horseback: the whole country being level, is every where full of salt marshes, and overflows at high water, so that the track is not sufficient for two to go abreast.

THE Salto, where I arrived on the 7th at night, is a place which serves as a kind of harbour for boats and small vessels. It is situated at the head of some creeks, particularly that of the Jambeli, between fourteen and sixteen leagues from the coast, but entirely destitute of inhabitants, no fresh water being found in any part of the adjacent country; so that it only serves for landing goods consigned to Tumbez, where they are carried on mules, kept there for this purpose; and in this its whole trade consists. The Salto is uninhabited; nor does it afford the least shelter, all the goods brought thither being deposited in a small square; and, as rain is seldom or never known here,

6

[page] 5

there is little danger of their receiving any damage before they are carried to Tumbez.

HERE, as along the sides of all the creeks, the man-grove-trees stand very thick, with their roots and branches so interwoven as to be absolutely impenetrable; tho' the swarms of muschetos are alone sufficient to discourage any one from going among them. The only defence against these insects is, to pitch a tent, till the beasts are loaded, and you again move forward. The more inland parts, where the tides do not reach, are covered with forests of smaller trees, and contain great quantities of deer; but at the same time are infested with tigers; so that if the continual stinging of the moschetos deprives travellers of their rest, it also prevents their being surprised by the tigers, of the fury of which there are many melancholy examples.

ON the 9th in the morning I arrived at the town of Tumbez, situated seven leagues from the Salto; the whole country through which the road lies is entirely waste, part of it being overflowed by the tides, and the other part dead sands, which reflect the rays of the sun so intensely, as to render it necessary in general to perform this journey in the night; for travelling seven leagues thither, and as many back, without either water or fodder, is much too laborious for the mules to undergo in the day-time. A drove of mules therefore never sets out from Tumbez for the Salto, till an account arrives, generally by one of the sailors belonging to the vessel, of the goods being landed, and every, thing in readiness; as it would otherwise be lost labour, it being impossible that the mules should make any stay there.

DON GEORGE JUAN had reached Tumbez on the 8th, and though he did every thing in his power to provide mules for continuing our journey, we were obliged to wait there some time longer. Nor could we make any advantage of our stay here, except to

[page] 6

observe the latitude, which we did on the ninth with a quadrant, and found it to be 3° 13′ 16″ south.

NEAR Tumbez, is a river of the same name, which discharges itself into the bay of Guayaquil, almost opposite to the island of St. Clare. Barks, boats, balzas, and canoos, may go up and down this river, being three fathom deep and twenty-five broad; but it is dangerous going up it in the winter season, the impetuosity of its current being then increased by torrents from the mountains. At a little distance from the Cordillera, on one side of the banks of the river, stands the town of Tumbez in a very sandy plain, interspersed with some small eminences. The town consists only of seventy houses, built of cane, and thatched, scattered up and down without any order or symmetry. In these houses are about one hundred and fifty families of Mestizos, Indians, Mulattoes, and a few Spaniards. There are besides these other families living along the banks of the river, who having the conveniency of watering their grounds, continually employ themselves in rural occupations.

THE heat is excessive; nor have they here any rain for several years successively; but when it begins to fall, it continues during the winter. The whole country from the town of Tumbez, to Lima, contained between the foot of the Cordillera and the sea, is known by the name of Valles, which we mention here, as it will often occur in the remaining parts of this narrative.

TUMBEZ was the place where in the year 1526, the Spaniards first landed in these parts of South America, under the command of Don Francisco Pizarro; and where he entered into several friendly conferences with the princes of the country, but vassals to the Yncas. If the Indians were surprized at the sight of the Spaniards, the latter were equally so at the prodigious riches which they every where saw, and the largeness of the palaces, castles, and

[page] 7

temples; of all of which, though built of stone, no vestiges are now remaining.

ALONG the delightful banks of this river, as far as the water is conveyed, maize, and all other fruits and vegetables that are natives of a hot climate, are produced in the greatest plenty. And in the more distant parts, which are destitute of this advantage, grows a kind of leguminous tree, called algarrobale, producing a bean, which serves as food for all kinds of cattle. It resembles almost that known in Spain by the name of valencia; its pod being about five or six inches long, and only four lines broad, of a whitish colour, intermixed with veins of a faint yellow. It proves a very strengthening food to beasts of labour, and is used in fattening those for the slaughter, which hence acquire a taste remarkably delicious.

ON the 14th, I arrived at the town of Piura, where I was obliged to wait some time for Don George Juan, during which I entirely recovered from the indisposition I before laboured under from my fall.

HERE I experienced the efficacy of the Calaguala; which I happily found not to fall short of the great reputation it has acquired in several parts of Europe.

FROM the town of Tumbez, to the city of Piura, is 62 leagues, which we performed in 54 hours, exclusive of those we rested; so that the mules, which always travel one constant pace, go something above a league an hour. To the town of Amotape, the only inhabited place in the whole road, is 48 leagues: the remaining part is one continued desart. At leaving Tumbez, its river is crossed in balzas, after which for about two leagues the road lies through thickets of algarrobale, and other trees, at the end of which the road runs along the sea-coast to Mancora, 24 leagues, from Tumbez. In order to travel this road, an opportunity at low Water must be taken for crossing a

[page] 8

place called Malpasso, about six leagues from Tumbez; for being a high steep rock, washed by the sea during the flood, and the top of it impassable from the many chasms and precipices, there is a necessity of passing between the sea and its basis, which is about half a league in length. And this must be done before the flood returns, which soon covers this narrow way, though it is very safe at low water. During the remainder of this journey, it is equally necessary to consult the tide; for the whole country being sandy, the mules would, from their sinking so deep in it, be tired the first league or two. Accordingly travellers generally keep along the shore, which being washed by the breaking of the waves the sand is more compact and firm; and consequently much easier to the beasts. During the winter, there runs through Mancora a small rivulet of fresh water, to the great relief of the mules; but in summer the little remaining in its course is so brackish, that nothing but absolute necessity can render it tolerable. The banks of this rivulet are so fertile by its water, that it produces such numbers of large algarrobales, as to form a shady forest.

FROM Mancora, the road for fourteen leagues runs between barren mountains, at some distance from the coast, with very troublesome ascents and declivities, as far as the breach of Parinnas; where the same cautions are to be observed as at Mancora, and is the second stage; from whence the road lies over a sandy plain, ten leagues in length, to the town of Amotape, and at some distance from the coast.

THIS town, which stands in 4° 51′ 43″ south latitude, is an appendix to the parish of Tumbez, belonging to its lieutenancy, and in the jurisdiction of Piura. The houses are about 30 in number, and composed of the same materials with those of Tumbez; but the inhabitants are only Indians and Mestizos. A quarter of league from it is a river of the

[page] 9

same name, and whose waters are of such prodigious use to the country, that it is every where cultivated, and divided into fields, producing plenty of the several grains, esculent vegetables, and fruits, natural to a hot climate; but like Tumbez, is infested with moschetos. This river in summer may be forded; but in winter, when the torrents descend from the mountains, it must be crossed in a balza, the rapidity of its current being then considerably increased. There is a necessity for passing it in going to Piura, and after this for about four leagues the road lies through woods of lofty algarrobales. These woods terminate on a sandy plain, where even the most experienced drivers and Indians sometimes lose their way, the wind levelling those hills of sana which served as marks, and effacing all the tracks formerly made: so that in travelling this country, the only direction is the sun in the day-time, and the stars in the night; and the Indians being little acquainted with the situation of these objects; are often bewildered, and exposed to the greatest hardships before they can again find their way.

FROM what has been said, the difficulties of travelling this road may be conceived. Besides, as far as Amotape, not only all kinds of provisions must be carried, but even water, and the requisites for kindling a fire, unless your provision consists of cold meat. In this last stage is a mine of cope, a kind of mineral tar, great quantities of which are carried to Callao, and other ports, being used in ships instead of naphtha, but has the ill quality of burning the cordage; its cheapness however induces them to use it mixed with naphtha.

THE city of Piura, which is at present the capital of its jurisdiction, was the first Spanish settlement in Peru. It was founded in the year 1531 by Don Francisco Pizarro, who also built the first church in it. This city was originally called San Miguel de

[page] 10

Piura, and stood in the valley of Targasala, from whence, on account of the badness of the air, it was removed to its present situation, which is on a sandy plain. The latitude of it is 5° 11′ 1″ south, and the variation of the needle we observed to be 8° 13′ easterly. The houses are either of bricks dried in the sun, or a kind of reeds called quinchas, and few of them have any story. Here the Corregidor resides, whose jurisdiction extends on one side along Valles, and on the other among the mountains. Here is an office for the royal revenue, under an accomptant or treasurer, who relieve each other every six months, one residing at the port of Paita, and the other in this place: at the former for receiving the duties on imports for goods landed there, and also for preventing a contraband trade; and at the latter for receiving the revenues and merchandizes on goods Consigned from the mountains to Loja, or going from Tumbez to Lima.

THIS city contains near fifteen hundred inhabitants; and among these some families of rank, besides other Spaniards, Mestizos, Indians, and Mulattoes. The climate is hot and very dry, rains being seldomer known here than at Tumbez; notwithstanding which it is very healthy. It has a river of great advantage to the inhabitants as well as the adjacent country, the soil of which is sandy, and therefore easier penetrated by the water; and being level, the water is conveyed to different parts by canals. But in the summer the river is absolutely destitute of water, the little which descends from the mountains being absorbed before it reaches the city; so that the inhabitants have no other, method of procuring water, but by digging wells in the bed of the river, the depth of which must be proportioned to the length of time the drought has continued.

PIURA has an hospital under the care of the BethIemites; and though patients afflicted with all kinds of

1

[page] 11

distempers are admitted, it is particularly famous for the cure of the French disease, which is not a little forwarded by the nature of the climate. Accordingly there is here a great resort of persons infected with that infamous distemper; und are restored to their former health by a less quantity of a specific than is used in other countries, and also with greater ease and expedition.

As the whole territory of this jurisdiction within Valles produces only the algarroba, maize, cotton, grain, a few fruits and esculent vegetables, most of the inhabitants apply themselves to the breeding of goats, great numbers of which are continually sold for slaughter, and from their fat they make soap, for which they are sure of a good market at Lima, Quito, and Panama; their skins are dressed into leather called Cordovan, and for which there is also a great demand at the above cities. Another branch of its commerce is the Cabuya, or Pita, a kind of plant from whence a very fine and strong thread is made; and which abounds in the mountainous parts of its jurisdiction. Great advantages are also made from their mules; as all the goods sent from Quito to Lima, and also those coming from Spain, and landed at the port of Paita, cannot be forwarded to the places they are consigned to but by the mules of this province; and from the immense quantity of goods coming from all parts, some idea may be formed of the number of beasts employed in this trade, which continues more or less throughout the year, but is prodigious when the rivers are shallow.

DON GEORGE JUAN being arrived at Piura, every thing was got ready with the utmost dispatch, and on the 21st we continued our journey. The next day we reached the town of Sechura, ten leagues distant from Piura, according to the time we were

[page] 12

travelling it. The whole country between these two places is a level sandy desart.

THOUGH the badness and danger of the roads in Peru scarce admit of any other method of travelling than on mules, yet from Piura to Lima there is a conveniency of going in litters. These instead of poles are suspended on two large canes, like those of Guayaquil, and are hung in such a manner as not to touch the water in fording rivers, nor strike against the rocks in the ascents or descents of difficult roads.

As the mules hired at Piura perform the whole journey to Lima, without being relieved, and in this great distance, are many long desarts to be crossed, the natural fatigue of the distance, increased by the sandiness of the roads, render some intervals of rest absolutely necessary, especially at Sechura, because on leaving that town we enter the great desart of the same name. We tarried here two days; during which we observed the latitude, and found it 5° 32′ 331/2″S.

THE original situation of this town was contiguous to the sea, at a small distance from a point called Aguja; but being destroyed by an inundation, it was thought proper to build the present town of Sechura about a league distance from the coast, near a river of the same name, and which is subject to the same alterations as that of Piura; for at the time we crossed it no water was to be seen; whereas from the months of February or March till August or September, its water is so deep and the current so strong, as to be passed only in balzas; as we found in our second and third journey to Lima. When the river is dry, the inhabitants make use of the above-mentioned expedient of digging wells in its beds, where they indeed find water but very thick and brackish. Sechura contains about 200 houses of cane, and a large and handsome brick church; the inhabitants

[page] 13

are all Indians, and consist of near 400 families, who are all employed either as drivers of the mules or fishermen. The houses of all these towns are quite simple; the walls consisting only of common canes and reeds, fixed a little way in the ground, with flat roofs of the same materials, rain being hardly ever known here; so that they have sufficient light and air, both the rays of the sun and wind easily find a passage. The Indian inhabitants of this place use a different language from that common in the other towns both of Quito and Peru; and this is frequently the case in great part of Valles. Nor is it only their language which distinguishes them, but even their accent; for besides their enunciation, which is a kind of melancholy singing, they contract half of their last words, as if they wanted breath to pronounce them.

THE dress of the Indian women in these parts, consists only of an anaco, like that of the women of Quito, except its being of such a length as to trail upon the ground. It is also much larger, but without sleeves, nor is it tied round them with a girdle. In walking they take it up a little, and hold it under their arms. Their head-dress consists of cotton cloth laced or embroidered with different colours; but the widows wear black. The condition of every one may be known by their manner of dressing their hair, maids and widows dividing it into two platted locks, one hanging on each shoulder, whilst married women braid all their hair in one. They are very industrious, and usually employed in weaving napkins of cotton and the like. The men dress in the Spanish manner; and consequently wear shoes; but the women none. They are naturally haughty, of very good understandings, and differ in some customs from those of Quito. They are a proof of what has been observed (Book VI. Chap. VI. vol. 1.) with regard to the great improvement they

[page] 14

receive from a knowledge of the Spanish language; and accordingly it is spoken here as fluently as their own. They have genius, and generally succeed in whatever they apply themselves to. They are neither so superstitious, nor so excessively given to vice as the others; so that except in their colour and other natural appearances, they may be said to differ greatly from them; and even in their propensity to intemperance, and other popular customs of the Indians, a certain moderation and love of order is conspicuous among these. But to avoid tedious repetitions, I shall conclude with observing, that all the Indians of Valles from Tumbez to Lima are industrious, intelligent, and civilized beyond what is generally imagined.

THE town of Sechura is the last in the jurisdiction of Piura, and its inhabitants not only refuse to furnish passengers with mules, but also will not suffer any person of whatever rank, to continue his journey, without producing the Corregidor's passport. The intention of this strictness is to suppress all abuses in trade; for there being besides this road which leads to the desart, only one other called the Rodeo; one of them must be taken; if that of the desart, mules must be hired at Sechura for carrying water for the use of the loaded mules when they have performed half their journey. This water is put into large callebashes, or skins, and for every four loaded mules one mule loaded with water is allowed, and also one for the two mules carrying the litter. When they travel on horseback, the riders carry their water in large bags or wallets made for that purpose; and every one of the passengers, whether in the litter or on horseback, provides himself with what quantity he thinks sufficient, as during the whole journey nothing is seen but sand and hills of it formed by the wind, and here and there masses

[page] 15

of salt; but neither sprig, herb, flower, or any other verdure.

ON the 24th we left Sechura, and crossed the desart, making only some short stops for the ease of our beasts, so that we arrived the next day at five in the evening at the town of Morrope, 28 or 30 leagues distance from Sechura, tho' falsely computed more by the natives. The extent and uniform aspect of this plain, together with the continual motion of the sand which soon effaces all tracks, often bewilders the most experienced guides, who however shew their skill in soon recovering the right way; for which they make use of two expedients: 1st, to observe to keep the wind directly in their face; and the reverse upon their return; for the south winds being constant here, this rule cannot deceive them; 2d, to take up a handful of sand at different distances, and smell to it; for as the excrements of the mules impregnate the sand more or less, they determine which is the true road by the scent of it. Those who are not well acquainted with these parts, expose themselves to great danger, by stopping to rest or sleep; for when they again set forward, they find themselves unable to determine the right road; and when they once have lost the true direction, it is a remarkable instance of Providence if they do not perish with fatigue or distress, of which there are many melancholy instances.

THE town of Morrope consists of between 70 and 80 houses, built like those in the preceding towns; and contains about 160 families, all Indians. Near it runs a river called Pozuelos, subject to the same changes as those above-mentioned: though the lands bordering on its banks are cultivated, and adorned with trees. The instinct of the beasts used to this road is really surprizing; for even at the distance of four leagues, they smell its water, and become so impatient that it would be difficult to stop them; ac-

[page] 16

cordingly they pursue themselves the shortest road, and perform the remainder of the journey with remarkable chearfulness and dispatch.

ON the 26th we left Morrope, and arrived at Lambayeque, four leagues from it: and being obliged to continue there all the 27th, we observed its latitude, and found it 6° 41′ 37″S. This place consists of about 1500 houses, built some of bricks, others of bajareques, the middle of the walls being of cane, and plaistered over, both on the inside and outside, with clay: the meanest consist entirely of cane, and are the habitations of the Indians. The number of inhabitants amount to about 3000, and among them, some considerable and opulent families; but the generality are poor Spaniards, Mulattoes, Mestizos, and Indians. The parish-church is built of stone, large and beautiful, and the ornaments splendid. It has four chapels called ramos, with an equal number of priests, who take care of the spiritual concerns of the Indians, and also attend, by turns, on the other inhabitants.

THE reason why this town is so populous is, that the families which formerly inhabited the city of Sana, on its being sacked in 1685, by Edward Davis, an English adventurer, removed hither; being under a farther necessity of changing their dwelling from a sudden inundation of the river of the same name, by which every thing that had escaped the ravages of the English was destroyed. It is the residence of a Corregidor, having under his jurisdiction, besides many other towns, that of Morrope. One of the two officers of the revenue appointed for Truxillo, resides here. A river called Lambayeque, washes this place; which, when the waters are high, as they were when we arrived here, is crossed over a wooden bridge: but at other times may be forded, and often is quite dry.

THE neighbourhood of Lambayeque, as far as the

[page] 17

industry of its inhabitants have improved it, by canals cut from the river, abounds in several kinds of vegetables and fruits; some of the same kind with those known in Europe; and others of the Creole kind, being European fruits planted there, but which have undergone considerable alterations from the climate. About ten leagues from it are espaliers of vines, from the grapes of which they make wine, but neither so good, nor in such plenty as in other parts of Peru. Many of the poor people here employ themselves in works of cotton, as embroidered handkerchiefs, quilts, mantelets, and the like.

ON the 28th we left Lambayeque, and having passed through the town of Monsefu, about four or five leagues distant from it, we halted near the sea coast, at a place called Las Lagunas, or the Fens; these contain fresh water left in them by the overflowings of the river Sana. On the 29th we forded the river Xequetepeque, leaving the town of that name at the distance of about a quarter of a league, and in the evening arrived at the town of St. Pedro, twenty leagues from Lambayeque, and the last place in its jurisdiction. By observation we found its latitude to be 7° 25′ 49″S.

ST. PEDRO consists of about 130 baxaraque houses, and is inhabited by 120 Indian families, 30 of Whites and Mestizos, and 12 of Mulattoes. Here is a convent of Augustines, though it seldom consists of above three persons, the prior, the priest of the town, and his curate. Its river is called Pacasmayo, and all its territories produce grain and fruits in abundance. A great part of the road from Lambayeque to St. Pedro, lies along the shore, not indeed at an equal, but never at a great distance from it.

ON the 30th of November we passed through the town of Payjan, which is the first in the jurisdiction of Truxillo, and on the first of December we reached that of Chocope, 13 or 14 leagues distant from

VOL. II. C

[page] 18

St. Pedro. We found its latitude to be 7° 46′ 46″ S. The adjacent country being watered by the river called Chicama, distributed to it by canals, produces the greatest plenty of sugar canes, grapes, fruits of different kinds, both European and Creole: and particularly maize, which is the general grain used in all Valles. From the banks of the river Lambayeque to this place, sugar canes flourish near all the other rivers, but none of them equal, ether in goodness or quantity, those near the river Chicama.

CHOCOPE consists of betwixt 80 and 90 baxareque houses, covered with earth. The inhabitants, who are between 60 and 70 families, are chiefly Spaniards, with some of the other casts; but not above 20 or 25 of Indians. Its church is built of bricks, and both large and decent. They report here, as something very remarkable, that in the year 1726, there was a continual rain of 40 nights, beginning constantly at four or five in the evening, and ceasing at the same hour next morning, the sky being clear all the rest of the day. This unexpected event intirely ruined the houses, and even the brick church, so that only some fragments of its walls remained. What greatly astonished the inhabitants was, that during the whole time the southerly winds not only continued the same, but blew with so much force, that they raised the sand, though thoroughly wet. Two years after a like phænomenon was seen for about eleven or twelve days, but was not attended with the same destructive violence as the former. Since which time nothing of this kind has happened, nor had any thing like it been remembered for many years before.

[page] 19

CHAP. II.

Our arrival at Truxillo; a Description of that City, and the Continuance of our Journey to Lima.

WITHOUT staying any longer at Chocope than is usual for resting the beasts, we continued our journey, and arrived at the city of Truxillo, 11 leagues distant, and, according to our observations, in 8° 6′ 3″ S. latitude. This city was built in the year 1535, by Don Francisco Pizarro, in the valley of Chimo. Its situation is pleasant, notwithstanding the sandy soil, the universal defect of all the towns in Valles. It is surrounded by a brick wall, and its circuit entitles it to be classed among cities of the third order. It stands about half a league from the sea, and two leagues to the northward of it is the port of Guanchaco, the channel of its maritime commerce. The houses make a creditable appearance. The generality are of bricks, decorated with stately balconies, and superb porticos; but the other of baxareques. Both are however low, on account of the frequent earthquakes; few have so much as one story. The corregidor of the whole department resides in this city; and also a bishop (whose diocese begins at Tumbez) with a chapter consisting of three dignitaries, namely, the dean, arch-deacon, and chanter; four canons, and two prebendaries. Here is an office of revenue, conducted by an accomptant and treasurer; one of whom, as I have already observed, resides at Lambayeque. Convents of several orders are established here; a college of Jesuits, an hospital of Our Lady of Bethlehem, and two nunneries, one of the order of St. Clare, and the other of St. Teresa.

THE inhabitants consist of Spaniards, Indians, and

C 2

[page] 20

all the other casts. Among the former are several very rich and distinguished families. All in general are very civil and friendly, and regular in their conduct. The women in their dress and customs follow nearly those of Lima, an account of which will be given in the sequel. Great number of chaises are seen here, there not being a family of any credit without one; as the sandy soil is very troublesome in walking.

IN this climate, there is a sensible difference between winter and summer, the former being attended with cold, and the latter with excessive heat. The country of this whole valley is extremely fruitful, abounding with sugar canes, maize, fruits, and garden stuff; and with vineyards and olive yards. The parts of the country nearest the mountains produce wheat, barley, and other grain; so that the inhabitants enjoy not only a plenty of all kinds of provisions, but also make considerable exports to Panama, especially of wheat and sugars. This remarkable fertility has been improved to the great embellishment of the country; so that the city is surrounded by several groves, and delightful walks of trees. The gardens also are well cultivated, and make a very beautiful appearance; which with a continual serene sky, prove not less agreeable to travellers than to the inhabitants.

ABOUT a league from the city is a river, whose waters are conducted by various canals, through this delightful country. We forded it on the 4th when we left Truxillo; and on the 5th, after passing through Moche, we came to Biru, ten leagues from Truxillo. The pass of the corregidor of Truxillo must be produced to the alcade of Moche, for without this, as before at Sechura, no person would be admitted to continue his journey.

BIRU, which lies in 8° 24′ 59′S. latitude, consists of 50 baxarcque houses, inhabited by 70 families of Spaniards, Indians, Mulattoes, and Mestizos.

[page] 21

About half a league to the northward of it, is a rivulet, from which are cut several trenches, for watering the grounds. Accordingly the lands are equally fertile with those of Truxillo, and the same may be said of the other settlements farther up the river. This place we left the same day, travelling sometimes along the shore, sometimes at a league distance from it.

ON the 6th we halted in a desart place called Tambo de Chao, and afterwards came to the banks of the river Santa; which having passed by means of the Chimbadores, we entered the town of the same name, which lies at about a quarter of a league from it, and 15 from Biru. The road being chiefly over vast sandy plains intercepted between two hills.

THE river Santa, at the place where it is usually forded, is near a quarter of a league in breadth, forming five principal streams, which run during the whole year with great rapidity. It is always forded, and for this purpose persons make it their business to attend with very high horses, trained up to stem the current, which is always very strong. They are called Chimbadores; and must have an exact knowledge of the fords, in order to guide the loaded mules in their passage, as otherwise the fording this river would be scarce practicable, the floods often shifting the beds of the river; so that even the Chimbadores themselves are not always safe; for the fords being suddenly changed in one of the streams, they are carried out of their depth by the current, and irretrievably lost. During the winter season, in the mountains, it often swells to such a height, as not to be forded for several days, and the passengers are obliged to wait the fall of the waters, especially if they have with them any goods; for those who travel without baggage may, by going six or eight leagues above the town, pass over it on balzas made of calabashes: though even here not without danger, for if the balza

[page] 22

happens to meet any strong current, it is swept away by its rapidity, and carried into the sea. When we forded it, the waters were very low, notwithstanding which, we found from three several experiments made on its banks, that the velocity of the current was 35 toises in 291/2 seconds: so that the current runs 4271 toises, or a league and a half, in an hour. This velocity does not indeed equal what M. de la Condamine mentions in the narrative of his voyage down the river Maragnon, or that of the Amazones, at the Pango, or streight at of Manceriche. But, doubtless when the river of Santa is at its usual height, it exceeds even the celerity of the Pango; at the time of making our observations, it was at its lowest.

THE latitude of the town of Santa Miria de la Parrilia, for so it is called, we determined by an observation of some stars, not having an opportunity of doing it by the sun, and found it 8° 57′ 36′S. It was first built on the sea coast, from which it is now something above half a league distant. It was large, populous, the residence of a Corregidor, and had several convents. But in 1685, being pillaged and destroyed by the above-mentioned English adventurer, its inhabitants abandoned it, and such as were not able to remove to a place of greater security, settled in the place where it now stands. The whole number of houses in it at present does not exceed thirty; and of these the best are only of baxareque, and the others of straw. These houses are inhabited with about 50 poor families consisting of Indians, Mulattoes, and Mestizos.

DURING our observations, we were entertained with a sight of a large ignited exhalation, or globe of fire in the air, like that mentioned in the first volume of this work, though not so large, and less effulgent. Its direction was continued for a considerable time towards the west, till having reached the sea coast, it disappeared with an explosion like that of cannon. Those

[page] 23

who had not seen it were alarmed, and imagining it to be a cannon fired by some ship arrived in the port, ran to arms, and hastened on horseback to the shore, in order to oppose the landing of the enemy. But finding all quiet, they returned to the town, only leaving some sentinels to send advice, if any thing extraordinary should happen. These igneous phænomena are so far from being uncommon all over Valles, that they are seen at all times of the night, and some of them remarkably large, luminous, and continuing a considerable time.

THIS town and its neighbourhood are terribly infested with moschitos. There are indeed some parts of the year when their numbers decrease, and sometimes, though very seldom, none are to be seen; but they generally continue during the whole year. The country from Piura upwards is free from this troublesome insect, except some particular towns, situated near rivers; but they swarm no where in such intolerable numbers as at Santa.

LEAVING this town on the 8th, we proceeded to Guaca-Tambo, a plantation so called, eight leagues distant from Santa, and contiguous to it is the Tambo, an inn built by the Yncas for the use of travellers. It has a shed for the convenience of passengers, and a rivulet running near it.

ON the 9th we came to another plantation known by the name of Manchan, within a league of which we passed through a village called Casma la Baxa, having a church, with not more than ten or twelve houses. Half way betwixt this and Manchan is another rivulet. The latter plantation is about eight leagues distant from the former. From Manchan on the tenth we travelled over those stony hills called the Culebras, extremely troublesome, particularly to the litters, and on the following day being the 11th, we entered Guarmey, 16 leagues from Manchan; and after travelling about three leagues further we reached

[page] 24

the Pascana, or resting place, erected instead of a tambo or inn, and called the Tambo de Culebras. The town of Guarmey is but small and inconsiderable, consisting only of 40 houses, and those no better than the preceding. They are inhabited by about 70 families, few of which are Spaniards. Its latitude is 10° 3′ 53″S. The corregidor has obtained leave to reside here continually, probably to be free from the intolerable plague of the moschitos at Santa, where formerly was his residence.

ON the 13th we proceeded from hence to a place called Callejones, travelling over 13 leagues of very bad road, being either sandy plains, or craggy eminences. Among the latter is one, nor a little dangerous, called Salto del Frayle, or the Friar's leap. It is an entire rock, very high, and, towards the sea, almost perpendicular. There is however no other way, though the precipice cannot be viewed without horror; and even the mules themselves seem afraid of it by the great caution with which they take their steps. On the following day we reached Guamanmayo, a hamlet at some distance from the river Barranca, and belonging to the town of Pativirca, about eight leagues from the Callejones. This town is the last in the jurisdiction of Santa or Guarmey.

PATAVIRCA consists only of 50 or 60 houses, and a proportional number of inhabitants: among whom are some Spanish families, but very few Indians. Near the sea coast, which is about three quarters of a league from Guamanmayo, are still remaining some huge walls of unburnt bricks; being the ruins of an ancient Indian structure; and its magnitude confirms the tradition of the natives, that it was one of the palaces of the ancient caseques, or princes; and doubtless its situation is excellently adapted to that purpose, having on one side a most fertile and delightful country, and on the other, the refreshing prospect of the sea.

[page] 25

ON the 15th we proceeded to the banks of the river Barranca, about a quarter of a league distant. We easily forded it, under the direction of Chimbadores. It was now very low, and divided into three branches, but being full of stones is always dangerous. About a league further is the town of Barranca, where the jurisdiction of Guaura begins. The town is populous, and many of its inhabitants Spaniards, though the houses do not exceed 60 or 70. The same day we reached Guaura, which from Guamanmayo makes a distance of nine leagues.

THIS town consists only of one single street, about a quarter of a league in length, and contains about 150 or 200 houses; some of which are of bricks, others of baxareques: besides a few Indian huts.

THIS town has a parish church, and a convent of Franciscans. Near it you pass by a plantation, extending above a league on each side of the road, which is every where extremely delightful; the country eastward, as far as the eye can reach, being covered with sugar-canes, and westward divided into fields of corn, maize, and other species of grain. Nor are these elegant improvements confined to the neighbourhood of the town, but the whole valley, which is very large, makes the same beautiful appearance.

AT the south end of the town of Guaura, stands a large tower, with a gate, and over it, a kind of redoubt. This tower is erected before a stone bridge, under which runs Guaura river: and so near to the town that it washes the foundations of the houses, but without any damage, being a rock. From the river is a suburb which extends above half a league, but the houses are not contiguous to each other; and the groves and gardens with which they are intermixed, render the road very pleasant. By a solar observation, we found the latitude of Guaura to be 11° 3′ 3″S. The sky is clear, and the tem-

[page] 26

perature of the air healthy and regular. For though it is not without a sensible difference in the seasons, yet the cold of the winter, and the heats of summer, are both easily supportable.

IN proceeding on our journey from Guarmey we met with a great many remains of the edifices of the Yncas. Some were the walls of palaces; others, as it were large dykes, by the sides of spacious highways; and others fortresses, or castles, properly situated for checking the inroads of enemies. One of the latter monuments stands about 2 or 3 leagues north of Pativirca, not far from a river. It is the ruins of a fort, and situated on the top of an eminence at a small distance from the sea; but the vestiges only of the walls are now remaining.

FROM Guaura we came to the town of Chancay; and though the distance between this is reckoned only twelve leagues, we concluded, by the time we were travelling, it to be at least fourteen. From an observation we found its latitude 11° 33′ 47″ S. The town consists of about 300 houses, and Indian huts; is very populous, and among other inhabitants can boast of many Spanish families, and some of distinguished rank. Besides its parish church, here is a convent of the order of St. Francis, and an hospital chiefly supported by the benevolence of the inhabitants. It is the capital of the jurisdiction of its name, and belongs to that of Guaura. The Corregidor, whose usual residence is at Chancay, appoints a deputy for Guaura. The adjacent country is naturally very fertile, and every where well watered by canals cut from the river Passamayo, which runs about a league and a half to the southward of the town. These parts are every where sowed with maize, for the purpose of fattening hogs, in which article is carried on a very considerable trade; the city of Lima being furnished from hence.

WE left Chancay the 17th; and after travelling

[page] 27

a league beyond the river Passamayo, which we forded, arrived at the tambo of the same name, situated at the foot of a mountain of sand, exceeding troublesome, both on account of its length, steepness, and difficulty in walking; so that it is generally passed in the night, the soil not being then so fatiguing.

FROM thence on the 18th we reached Tambo de Ynca, and after travelling 12 leagues from the town of Chancay, we had at length the pleasure of entering the city of Lima.

FROM the distances carefully set down during the whole course of the journey, it appears that from Tumbez to Piura is 62 leagues, from Piura to Truxillo 89, and from Truxillo to Lima 113; in all 264 leagues. The greatest part of this long journey is generally performed by night; for the whole country being one continued sand, the reflection of the sun's rays is so violent, that the mules would be overcome by the heat; besides the want of water, herbage, and the like. Accordingly the road all along is rather distinguished by the bones of the mules which have sunk under their burdens, than by any track or path. For notwithstanding they are continually passing and re-passing throughout the whole year, the winds quickly efface all the prints of their feet. This country is also so bare, that when a small herb or spring happens to be discovered, it is a sure sign of being in the neighbourhood of houses. For these stand near rivers, the moisture of which fertilizes these arid wastes, so that they produce that verdure not to be seen in the uninhabited parts: as they are such merely from their being destitute of water; without which no creature can subsist, nor any lands be improved.

IN the towns we met with plenty of all necessary provisions; as flesh, fowl, bread, fruits, and wine; all extremely good, and at a reasonable price; but

[page] 28

the traveller is obliged to dress his meat himself, if he has not servants of his own to do it for him; for in the greatest parts of the towns be will not meet with any one, inclinable to do him that piece of service, except in the larger cities where the masters of inns furnish the table. In the little towns, the inns, or rather lodging houses, afford nothing but shelter; so that travellers are not only put to the inconvenience of carrying water, wood and provisions, from one town to another, but also all kinds of kitchen utensils. Besides tame fowl, pigeons, peacocks and geese, which are to be purchased in the meanest towns, all cultivated parts of this country abound in turtle doves, which live intirely on maize and the seeds of trees, and multiply exceedingly; so that shooting them is the usual diversion of travellers while they continue in any town; but except these, and some species of small birds, no others are to be had during the whole journey. On the other hand, no ravenous beasts, or venomous reptiles, are found here.

THE distribution of waters by means of canals, which extend the benefit of the rivers to distant parts of the country, owes its origin to the royal care and attention of the Yncas; who among other marks of their zeal for promoting the happiness of their subjects, taught them by this method, to procure from the earth, whatever was necessary either for their subsistance, or pleasure. Among these rivers, many are entirely dry or very low, when the waters cease to flow from the mountains; but others, as those of Santa Baranca, Guaura, Passamayo, and others, continue to run with a full stream during the greatest drought.

THE usual time when the water begins to increase in these rivers is the beginning of January or February, and continues till June, which is the winter among the mountains; and, on the contrary, the

[page] 29

summer in Valles; in the former it rains, while in the latter the sun darts a violent heat, and the south winds are scarce felt. From June the waters begin to decrease, and in November or December the rivers are at their lowest ebb, or quite dry; and this is the winter season in Valles, and the summer in the mountains. So remarkable a difference is there in the temperature of the air, though at so small a distance.

CHAP. III.

Account of the City of Lima, the Capital of Peru.

FORTUITOUS events may sometimes, by their happy consequences, be classed among premeditated designs. Such was the unforeseen cause which called us to Peru; for otherwise the history of our voyage would have been deprived of a great many remarkable and instructive particulars; as our observations would have been limited to the province of Quito. But by this invitation of the vice-roy of Peru, we are now enabled to lead the reader into that large and luxuriant field, the fertile province of Lima, and the splendid city of that name, so justly made the capital of Peru, and the queen of all the cities in South America. It will also appear that our work would have suffered a great imperfection, and the reader consequently disappointed in finding no account of those magnificent particulars, which his curiosity had doubtless promised itself, from a description of this famous city, and an accurate knowledge of the capital province. Nor would it have been any small mortification to ourselves, to have lost the opportunity of contemplating those noble objects, which so greatly increase the value of our work, though already enriched with such astronomical

[page] 30

observations and nautical remarks, as we hope prove agreeable to the intelligent reader. At the same time it opens a method of extending our re-searches into the other more distant countries, for the farther utility and ornament of this voyage; which as it was founded on the most noble principles, she be conducted and closed with an uniform dignity.

MY design however is not to represent Lima in its present situation, as I should then, instead of noble and magnificent objects, introduce the most melancholy and shocking scenes; ruinated palaces, churches, towers, and other stately works of art, together with the inferior buildings of which this opulent city consisted, now thrown into ruin and confusion, by the tremendous earthquake of October the 28th, 1746; the affecting account of which reached Europe with the swiftness which usually attends unfortunate advicd and concerning which, we shall be more particulars in another place. I shall not therefore describe Lima, as wasted by this terrible convulsion of nature; but as the emporium of this part of America, and endeavour to give the reader an idea of its former glory magnificence, opulence, and other particulars which rendered it so famous in the world, before it suffered under this fatal catastrophe; the recollection of which cannot fail of being painful to every lover of his country, and every person of humanity.

THE city of Lima, or as it is also called the city or the kings, was, according to Garcilaso, in his history of the Yncas, founded by Don Francisco Pizarro, on the feast of the Epiphany, 1535; though others affirm that the first stone was not laid till the 18th of January that year; and the latter opinion is confirmed by the act, or record of its foundation, still preserved in the archives of that city. It is situated in the spacious and delightful valley of Rimac, an Indian word, and the true name of the city itself, from a corrupt pronunciation of which word the Spaniard

3

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 31

have derived Lima. Rimac is the name by which both the valley and the river are still called. This appellation is derived from an idol to which the native Indians used to offer sacrifice, as did also the Yncas, after they had extended their empire hither; and as it was supposed to return answer to the prayers addressed to it, they called it by way of distinction Rimac, or, he who speaks. Lima, according to several observations we made for that purpose, stands in the latitude of 12° 2′ 31″S. and its longitude from the meridian of Teneriffe is 299° 27′ 27′.72/3 ″. The variation of the needle is 9° 2′ 30″ easterly.

ITS situation is one of the most advantageous that can be imagined; for being in the centre of that spacious valley, it commands the whole without any difficulty. Northward, though at a considerable distance, is the cordillera, or chain of the Andes; from whence some hills project into the valley, the nearest of which to the city are those of St. Christopher, and Amancaes. The perpendicular height of the former, according to a geometrical mensuration performed by Don George Juan, and M. de la Condamine in 1737, is 134 toises; but father Fevillée makes it 136 toises and one foot, which difference doubtless proceeds from not having measured with equal exactness, the base on which both founded their calculations. The height of the Amancaes, is little less than the former, and situated about a quarter of a league from the city.

THE river, which is of the same name, washes the walls of Lima, and when not increased by the torrents from the mountains is easily forded; but at other times, besides the increase of its breadth, its depth and rapidity render fording impossible; and accordingly a very elegant and spacious stone bridge is built over it, having at one end a gate, the beautiful architecture over which is equal to the other parts of this useful structure. This gate forms the entrance into the city, and leads to the grand square,

[page] 32

which is very large and finely ornamented. In the centre is a fountain, equally remarkable for its grandeur and capacity. In the centre is a bronze statue of Fame, and on the angles are four small basons. The water is ejected through the trumpet of the statue, and also through the mouths of eight lions which surround it, and greatly heighten the beauty of this work. The east side of the square is filled by the cathedral and the archiepiscopal place, whose height surpasses the other buildings in the city. Its principal foundations, and the bases of its columns and pilasters, together with the capital front which faces the west, are of freestone; the inside resembles that of Seville, but not so large. The outside is adorned with a very magnificent façade or frontispice, rising into two lofty towers, and in the centre is the grand portal. Round the whole runs a grand gallery, with a balustrade of wood, resembling brass in colour, and at proper distances are several pyramids, which greatly augment the magnificence of the structure. In the north side of the square is the vice-roy's palace, in which are the several courts of justice, together with the offices of revenue, and the state prison. This was formerly a very remarkable building, both with regard to its largeness and architecture, but the greatest part of it being thrown down by the dreadful earthquake with which the city was visited, Oct. 20th, 1687, it now consists only of some of the lower apartments erected on a terras, and is used as the residence of the vice-roy and his family.

ON the west side which faces the cathedral, is the council-house, and the city prison; the south side is filled with private houses, having only one story; but the fronts being of stone, their uniformity, porticoes, and elegance, are a great embellishment to the square, each side of which is 80 toises.

THE form of the city is triangular, the base, or longest side, extending along the banks of the river.

1

[page] 33

Its length is 1920 toises, or exactly two-thirds of a league. Its greatest breadth from N. to S. that is, from the bridge to the angle opposite to the base, is 1080 toises, or two-fifths of a league. It is surrounded with a brick wall, which answers its original intention, but is without any manner of regularity. This work was bagun and finished by the duke de la Plata in the year 1685. It is flanked with 34 bastions, but without platforms or embrasures; the intention of it being merely to inclose the city, and render it capable of sustaining any sudden attack of the Indians. It has, in its whole circumference, seven gates and three posterns.

ON the side of the river opposite to the city is a suburb, called St. Lazaro, which has, within these few years, greatly increased. All the streets of this suburb, like those of the city, are broad, parallel, or at right angles some running from N. to S. and others from E. to W. forming squares of houses, each 150 yards in front, the usual dimensions of all these quadras or squares in this country, whereas those of Quito are only 100. The streets are paved, and along them run streams of water, conducted from the river a little above the city; and being arched over contribute to its cleanliness, without the least inconveniency.

THE houses, though for the most part low, are commodious, and make a good appearance. They are all of baxareque and quincha. They appear indeed to be composed of more solid materials, both with regard to the thickness of the principal walls, and the imitation of cornices on them; and that they may the better support themselves under the shocks of earthquakes, of which this city has had so many dreadful instances, the principal parts are of wood, mortised into the rafters of the roof, and those which serve for walls are lined both within and without with wild canes, and chaglias or osiers; so that the timber-work is totally inclosed. These osiers

VOL. II. D

[page] 34

are plaistered over with clay, and whitewashed, but the fronts painted in imitation of free-stone. They afterwards add cornices and porticos which are also painted as a stone colour. Thus the whole front imposes on the sight, and strangers suppose them to be built of those materials which they only so far as is necessary to keep out the wind and intercept the rays of the sun. The pieces of timber, of which the roofs are formed, and which on the inside are decorated with elegant moulding and other ornaments, are covered with clay to preserve them from the sun. This slender covering is sufficient, as no violent rains are ever known here. Thus the houses are in less danger than if built of more compact materials; for the whole building yields to the motions of the earthquakes, and the foundations which are connected with the several parts of the building follow the same motion; and by that means are not so easily thrown down.

The wild canes, which serve for the inner parts of the walls, resemble in length and bigness those known in Europe, but without any cavity. The wood of them is very solid, and little subject to rot. The chaglla is also a kind of shrub growing wild in the forests and on the banks of rivers. It is strong and flexible like the osier. These are the materials of which the houses in all the towns of Valles mentioned in the preceding chapter, are bulilt.

TOWARDS the cast and west parts of the city, but with in the walls, are a great many fruit and kitchen gardens; and most of the principal houses have gardens for entertainment, being continually refreshed with water by means of the banals.

THE whole city is divided into the five following parishes. 1. Segrario, which has three priests. 2. St. Ann, and 3. St. Sebastian, each having two priests. 4. St. Marcelo, and 5. St.Lazaro, each of which has one priest only. The parish of the latter extends it-

[page] 35

self five leagues, namely, to the valley of Carabaillo, and to it belong the many large plantations in that space; chapels are therefore erected for celebrating mass on days of precept, that the people may perform their duty without the fatigue and trouble of travelling to Lima. Here are also two chapels of ease: that of St. Salvador in the parish of St. Ann; and that of the orphans, in the Sagrario. There is also in the Cercado, one of the quarters of the town, a parish of Indians, under the care of the Jesuits.

THE convents here are very numerous; four Dominicans, viz. La Casa grande, Recolleccion de la Magdalena, the college of St. Thomas appropriated to literature, and Santa Rosa. Three of Franciscans, viz. Casa grande, Recoletos de nuestra Senora de los Angeles, or Guadalupe, and Los Descalzos de San Diego: the latter is in the suburb of San Lazaro. Three of the order of Augustin, namely, Casa grande; the seminary of San Ildefonso, a literary college; and the noviciate at Nuestra Senora de Guia. Three also belong to the order of Mercy, namely, the Casa principal, the college of St. Pedro Nolasco, and a Recolleccion, called Bethlehem.

THE Jesuits have six colleges or houses, which are those of St. Paul, their principal college; St. Martin, a college for secular students; St. Anthony, a noviciate; the house of possession, or desamparados, under the invocation of Nuestra Senora de los Dolores; a college in the Circado, where the Indians are instructed in the precepts of religion; and that of the Chacarilla, appointed for the exercises of St. Ignatius; and accordingly all seculars on their desire to perform them are admitted. They are also allowed the liberty of beginning when most convenient for themselves, and are handsomely entertained by the college during the eight days of their continuance. But it must be observed, that of all these convents, the Casas grandes are now the most

D 2

[page] 36

considerable; the others, besides being small, have but few members, and small revenues.

BESIDES the preceding nineteen convents and colleges, here are also an oratory of St. Philip Neri; a monastery of the order of St. Benedict, with the title of Nuestra Senora de Monserrat, the abbé of which is commonly the only member, and sent from Spain; and though this foundation is one of the most ancient in the whole city, its revenue is hardly sufficient to support any more: a convent called Nuestra Senora de la Buena Muerte, or the order of that name, generally known by the name of Agonizantes. This order founded an hospital in the city, in 1715, under the particular direction of the fathers Juan Mugnos, and Juan Fernandez, who with a lay brother of the same order having in 1736 obtained a licence from the council of the Indians, went from Spain and founded a convent of community, in every form. In the suburb of St. Lazaro is also a convent of St. Francis de Paula, a modern foundation, under the name of Nuestra Senora del Scorro.

THERE are also in Lima three other charitable foundations, namely: St. Juan de Dios, served by the religious of that order, and appropriated to the relief of persons recovering from sickness; and two of Bethlemites; one of which, being the Casa grande, is without the city, and founded for the relief of sick Indians, who are taken care of in Santa Anna; and the other within the city, called that of the incurables, being appropriated to persons labouring under diseases of that nature. The latter, as we have already observed,* was founded so early as the year 1671. This opulent city has also nine other hospitals, each appropriated to some peculiar charity.

1. SAN Andres, a royal foundation admitting only Spaniards.

* Chap. IV. Lib. V. Vol. I.

[page] 37

2. San Pedro, for poor ecclesiastics.

3. El Espiritu Santo, for mariners, and supported by the ships belonging to these seas, their crews being properly assessed for that purpose.

4. St. Bartholome, for the negroes.

5. Senora Santa Anna, for the Indians.

6. San Pedro de Alcantara, for women.

7. Another for that use, under the care of the Bethlemite fathers, erected before their Casa grande.

8. La Caridad, also for women.

9. San Lazaro, for the lepers, which with those already enumerated, make twelve.

Here are also 14 nunneries, the number of persons in which would be sufficient to people a small town. The 5 first are regulars, and the other 9 recollects.

1. La Encarnation. 2. La Conception. 3. Santa Cathalina. 4. Santa Clara. 5. La Trinidad. 6. El Carmen. 7. Santa Teresa, ò El Carmen baxo. 8. Las Descalzas de San Joseph. 9. Las Capuchinas. 10. Las Nazarenas. 11. Las Mercidarias. 12. Santa Rosa. 13. Las Trinitarias Descalzas. 14. Las Monjas del Prado.

Lastly, Here are four other conventual houses, where some few of the sisters are not recluses, though most of them observe that rule. These houses are:

1. Santa Rosa de Viterbo. 2. Nuestra Senora del Patrocinio. 3. Nuestra Senora de Capacabana, for Indian ladies. 4. San Joseph.

The last is a retreat for women who desire to be divorced from their husbands. There is also a house constituted in the manner of convents, for poor women, and under the direction of an ecclesiastic appointed by the archbishop, who is also their chaplain.

THE most numerous of all these nunneries, are the Incarnation, Conception, Santa Clara, and Santa Cathalina. The others are indeed not so large; but the Recollects, in the rectitude and austerity of their lives, are an example to the whole city.

[page] 38

HERE is also an orphan-house, divided into two colleges, one for the boys, and the other for the girls: besides several chapels, in different parts of the city; but the following list will shew at once, the parishes, hospitals, churches and monasteries of Lima; which was always no less conspicuous with regard to a zeal for religion than for splendour.

LIST of the parishes, convents of each order, hospitals, nunneries, and conventual houses in Lima.

Parishes 6.

CONVENTS of San Domingo, 4. Of San Francis, 3. Of San Augustin, 3. Of la Merced, 3.

COLLEGES of Jesuits, 6.

ORATORY of St. Philip Neri, 1.

MONASTERY of Benedictins, 1. Of San Francisco de Paula, 1. Of Agonizantes, 1. Of San Juan de Dios, 1. Of Bethlemites, 2.

NUNNERIES of Regulars, 5. Of Recollets, 9.

CONVENTUAL House, 4, Houses for poor women, 1. Orphan house, 1. Hospital, 12.

ALL the churches, both conventual and parochial, and also the chapels, are large, constructed partly of stone, and adorned with paintings and other decorations of great value; particularly the cathedral, the churches of St. Dominic, St. Francis, St. Augustin, the fathers of Mercy, and that of the Jesuits, are so splendidly decorated, as to surpass description; an idea being only to be formed by the sight. The riches and pomp of this city, especially on solemn festivals, are astonishing. The altars, from their very bases to the borders of the paintings, are covered with massive silver, wrought into various kinds of ornaments. The walls also of the churches are hung with velvet, or tapestry of equal value, adorned with gold and silver fringes: all which in this country is remarkably dear; and on these are splendid pieces of plate in various figures. If the eye be directed from

[page] 39

the pillars, walls, and ceiling, to the lower part of the church, it is equally dazzled with glittering objects, presenting themselves on all sides: among which are candlesticks of massive silver, six or seven feet high, placed in two rows along the nave of the church; embossed tables of the same metal, supporting smaller candlesticks; and in the intervals betwixt them pedestals on which stand the statues of angels. In fine, the whole church is covered with plate, or something equal to it in value; so that divine service, in these Churches, is performed with a magnificence scarce to be imagined; and the ornaments, even on common days, with regard to their quantity and richness, exceed those which many cities of Europe pride themselves with displaying on the most common occasions.

IF such immense riches are bestowed on the body of the church, how can imagination itself form an idea of those more immediately used in divine worship, such as the sacred vessels, the chalices, ostensoriums, &c. in the richness of which there is a sort of emulation between the several churches? In those the gold is covered with diamonds, pearls, and precious stones, so as to dazzle the eye of the spectator. The gold and silver stuff for vestments and other decorations, are always of the richest and most valuable among those brought over by the register ships. In fine, whatever is employed in ornamenting the churches, is always the richest of the kind possible to be procured.

THE principal convents are very large, with convenient and airy apartments. Some parts of them, as the outward walls which inclose them, are of unburnt bricks; but the building itself of quinchas or baxareques. The roofs of many are arched with brick, others only with quinchas; but of such curious architecture as entirely to conceal the materials; so that the frontispieces and principal gates have a majestic appearance. The columns, friezes, statues and cornices

[page] 40

are of wood, finely carved, but so nearly imitating the colour and appearance of stone, as only to be discovered by the touch. This ingenious imitation does not proceed from parsimony, but necessity; in order to avoid as much as possible the dreadful devastations of earthquakes, which will not admit of structures built with ponderous materials.

THE churches are decorated with small cupolas of a very pretty appearance: and though they are all of wood, the sight cannot distinguish them from stone. The towers are of stone from the foundation the height of a toise and a half, or two toises, and from thence to the roof of the church of brick, but the remainder of wood painted of a free-stone colour, terminating in a statue, or image alluding to the name of the church. The height of these may be nearly known from that of St. Dominic, which by a geometrical mensuration we found to be between 50 and 60 yards; a height which though small in proportion to the largeness of the structure, is a necessary caution both with regard to the shocks of earthquakes, and the weight of the bells, which in size and number exceed those of Spain, and on a general ringing produce a very agreeable harmony.

ALL the convents are furnished with water from the city though not from that of the rivulets, which as we before observed, run through the streets in covered channels; but brought from a spring by means of pipes. While on the other hand, both the monasteries and nunneries are each obliged to maintain a fountain in the street, for the public use of poor people, who have not the conveniency of water in their houses.

THE viceroys, whose power extends over all Peru, usually reside at Lima: but the province and audience of Quito has been lately detached from it; as we have observed in our account of that province. This government is triennial, though at the expiration

3

[page] 41