[page i]

AN ACCOUNT

OF

THE NATIVES

OF THE

TONGA ISLANDS,

IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN.

WITH

AN ORIGINAL GRAMMAR AND VOCABULARY

OF

THEIR LANGUAGE.

COMPILED AND ARRANGED FROM THE EXTENSIVE COMMUNICATIONS OF

MR. WILLIAM MARINER,

SEVERAL YEARS RESIDENT IN THOSE ISLANDS.

BY JOHN MARTIN, M. D.

"The savages of America inspire less interest…. since celebrated navigators have made known to us the inhabitants of the islands of the South Sea…. The state of half civilization in which those islanders are found gives a peculiar charm to the description of their manners…. Such pictures, no doubt, have more attraction than those which pourtray the solemn gravity of the inhabitant of the banks of the Missouri or the Maranon."

Preface to Humbeldt's Personal Narrative.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR,

AND SOLD BY JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

1817.

[page ii]

T. Davison, Lombard-street,

Whitefriars, London.

[page 1]

CHAP. XV.

The king annihilates the divine chiefdom of Tooitonga, and the ceremony of inachi—Mr. Mariner's adopted mother departs for Hapai—The stratagem used to prevent her female attendants from accompanying her—Spirited speech of Tálo on this occasion—All communication with the Hapai islands shut up—The king's extraordinary attention to the cultivation and defence of the country—Interesting anecdote respecting two chiefs, Hála A'pi A'pi and Tálo—Attempt from the people of Hapai—Mr. Mariner discovers an European vessel whilst on a fishing excursion: his men refusing to take him on board, he wounds one mortally, and threatens the others, upon which they paddle towards the ship—Anecdote of the wounded man—Mr. Mariner's arrival on board, and reception from the captain—The king visits him in the ship: his behaviour on board: his earnest wish to go to England—Mr. Mariner sends on shore for the journal of the Port au Prince, and procures the escape of two of his countrymen—Further transactions on board—He takes a final leave of the king—The ship sails for the Hapai islands.

IN consequence of Tooitonga's death, the great obstacle to shutting up the communication with Hapai was, for a time at least, re-

VOL. II. B

[page] 2

moved; but that it might be so more completely, the king came to a determination of having no more Tooitongas, and thus to put a stop for ever to the ceremony of inachi; for he conceived that there was very little public utility in what was supposed to be the divine authority of Tooitonga; but that it was, on the contrary, a great and useless expense to the people. This measure, as may be imagined, did not prove very objectionable to the wishes of the multitude, as it relieved them from the inachi, a very heavy tax; and, in times of scarcity, of course extremely oppressive. In regard to the religions objections which one might suppose would be started against the endeavour to set aside an institution so ancient, so venerable, and so sacred, as that of Tooitonga's divine authority,—it must be noticed that the island of Tonga had, for many years, been deprived of the power, presence, and influence of Tooitonga, owing to its political situation; and, notwithstanding, appeared in the eyes of Finow, and of all his chiefs, warriors, and subjects, to be not less favoured with the bounties of heaven and of nature than the other islands, excepting the mischief and destruction which arose from human passion and disturbances: and if Tonga could

[page] 3

exist without this divine chief, why not Vavaoo, or any other island? This strong argument growing still stronger, upon a little reflection, brought the chiefs, matabooles, and older members of society, to the resolution, that Tooitonga was of no use at all; and the people themselves, ever willing to fall into measures that greatly promote their interest, notwithstanding a few religious scruples, very soon came to be of the same opinion too.

As soon as Finow had come to this determination, and to that of shutting up all communication with the Hapai people, it became necessary to acquaint Tongamana, at his next arrival, with this new regulation, and to forbid him ever to return to Vavaoo again. In the mean time, however, as Finow had promised Tooi Bolotoo that his daughter (Mr. Mariner's adopted mother) should be allowed to proceed to him at the Hapais, she was ordered to get herself and attendants ready to accompany Tongamana on his way back. Now it happened this person had a great number of female attendants, many of whom were some of the handsomest women at Vavaoo; and, as the leave granted to her to depart was equally a licence for the departure of her attendants, Finow became apprehensive that the alienation of

B 2

[page] 4

so many fine women from the country would occasion considerable discontent among his young men, and would perhaps tempt some of them to take the same step. He sent, however, for Máfi Hábe, and told her, that, with her leave, he would contrive some means to keep back her women, whose departure might occasion so much disturbance: in this intention she perfectly coincided, as she should have little use for them hereafter, in the retired life she meant to lead with her father,—two favourite attendants, however, excepted, whom she begged to take with her. Matters being so far agreed on, Finow, to avoid the appearance of injustice on his part, gave Mr. Mariner instructions how to act, with a view to bring about his object, as if it were a thought and impulse of his own. Accordingly, when Tonga-mana's canoe was ready to depart, and every one in it, save Máfi Hábe and her attendants, she was carried on board, and her two favourite attendants immediately followed: at this moment, when the rest of the women were about to proceed into the canoe, Mr. Mariner, who had purposely stationed himself close at hand with his musket, seized hold of the foremost, and threw her into the water, and forbad the rest to follow, at the

[page] 5

peril of being shot. He then called out to Finow's attendants, who were purposely seated on the beach, to come to his assistance, pretending to express his wonder at their folly, in permitting those women to leave them, for whose protection they had often hazarded their lives in battle: upon this (as had been previously concerted) they ran forward, and effectually prevented any of them from departing. At this moment, while their lamentations rent the air, Finow came down to the beach; and enquiring the cause of this disturbance, they told him that Togi (Mr. Mariner) had used violent measures to prevent their accompanying their beloved mistress, and that the young chiefs had cruelly assisted him. One of these chiefs (Talo) then addressed Finow:—"We have all agreed to lose our lives rather than suffer these women, for whom we have so often fought, to take leave of us for ever. There is good reason to suppose that we shall soon be invaded by the people of Hapai: and are we to suffer some of the finest of our women to go over to the men who will shortly become our enemies? Those women, the sight and recollection of whom have so often cheered our hearts in the time of danger, and enabled us to meet the

[page] 6

bravest and fiercest enemies, and to put them to the rout? If our women are to be sent away, in the name of the gods, send away also the guns, the powder, and all our spears, our clubs, our bows and arrows, and every weapon of defence: with the departure of the women our wish to live departs also, for then we shall have nothing left worth protecting, and, having no motive to defend ourselves, it matters little how we die."

Finow upon this was obliged to explain to Tongamana the necessity of yielding to the sentiments of these young chiefs, to prevent the discontent and disturbance which might otherwise take place. The canoe was now ordered to leave Vavaoo for the last time, and never more to return, for if she or any other canoe should again make her appearance from Hapai, her approach would be considered hostile, and proper measures would accordingly be adopted. At this moment, the women on the beach earnestly petitioned Finow to be allowed to take a last farewell of their dear and beloved mistress, which on being agreed to, nearly two hours were taken up in this affecting scene.

From this time Finow devoted his attention to the cultivation of the island; and the exer-

[page] 7

tions of this truly patriotic chief were so far successful that the country soon began to promise the appearance of a far more beautiful and cultivated state than ever: nor did he in the mean time neglect those things which were necessary for the better defence of the place, and accordingly the fortress underwent frequent examination and improvements.

In the midst of these occupations, however, a circumstance happened which might have been the cause of much civil disturbance. It is well worth relating, as it affords an admirable character of one of the personages concerned, and shews a principle of honour and generosity of mind, which must afford the highest pleasure to those who love to hear of acts worthy the character of human nature. On one of the days of the ceremony known by the name of tow tow*, which is celebrated on the marly, with wrestling, boxing, &c., a young chief, of the name of Talo, entered into a wrestling-match with Hala Api Api (the young chief who, as may be recollected, was mentioned on the occasion of Toobo Neuha's assassination). It should however be noticed, that a few days

* An offering to the god of weather, beginning at the time when the yams are full grown, and is performed every day for eighty days.

[page] 8

before, these two had held a debate upon some subject or another, in which neither could convince the other. It is usual on such an occasion, to prevent all future fruitless argument upon the subject, to settle the affair by wrestling: not that this mode is considered in the light of a knock-down argument, perfectly convincing in its nature, but it is the custom for those who hold a fruitless contention in argument, to end the affair the next opportunity, by a contention in physical strength, after which the one who is beaten seldom presumes to intrude his opinion again on the other, at least not upon the same subject. Hala Api Api therefore challenged Talo on the spot. For a long time the contest was doubtful; both well made, both men of great strength: at length, however, it was the fate of Talo to fall, and thus the contest ended. The fallen chief, chagrined at this event, could not allow, in his own mind, that his antagonist had overcome him by superior strength, but rather owing to an accidental slip of his own foot; and consequently resolved to enter the lists with him again at some future and favourable opportunity. This occasion of the ceremony of tow tow presenting itself, Talo left his companions and seated himself immediately opposite Hala Api Api;

[page] 9

a conduct which plainly indicated his wish that the latter in particular should engage with him: a conduct, too, which, though sometimes adopted, is generally considered indicative of a quarrelsome disposition, because the challenge ought not to be made to one in particular, but to any individual among those of a different place or party who chooses to accept it. As soon as Hala Api Api and his friends perceived this, it was agreed among them that he alone should oppose him. In a short time Talo arose and advanced; Hala Api Api immediately closed with him and threw him, with a severe fall. At this moment the shouts of the people so exasperated Talo, (for he had made sure in his own mind of gaining a victory) that, on the impulse of passion, he struck his antagonist, whilst rising off him, a violent blow in the face; on which Hala Api Api threw himself in a posture of defence, and demanded if he wished to box with him: Talo, without returning an answer, matched a tocco tocco*, and would evidently have run him through the body if he had not been withheld. Hala Api Api, with a nobleness of spirit worthy of admiration, seemed to take no notice of this, but smiling

* A spear about five feet long, used by them as a walking stick, but seldom employed in bottle.

[page] 10

returned to his seat amid the acclamations of the whole assembly. All applauded his greatness of soul, as conspicuous now as on other occasions; Finow in particular shewed signs of much satisfaction, and in the evening, when he was drinking cava with the matabooles, whilst this noble chief had the honour to wait on them, the king addressed himself to him, returning thanks for the presence of mind which he had proved, and his coolness of temper; which conduct had placed his superiority and bravery in a far more splendid light than if he had given way to resentment: and as to his retiring, without seeking farther to prolong the quarrel, he was convinced (he said) that he had in view nothing but the peace and happiness of the people, which would undoubtedly have been disturbed by an open rupture with a man who was at the head of so powerful a party. To this the young chief made only this reply: "Co ho möóni;* and appeared overcome by a noble modesty, at being so much praised (contrary to custom) before so large an assembly.

In the mean while, Talo, conscious of his error, and ashamed to appear in public, retired

* Meaning liberally, "it is your truth:"—that is, what you say is true.

[page] 11

to one of his plantations called Mote; whilst Hala Api Api, imagining what must be the distress of his feelings, resolved upon a reconciliation, and having intimated this to his men, he desired them to go armed, in case any misunderstanding should accidentally arise. Accordingly, one morning he and his men left the moca, after having given out that he was going up the country to kill some hogs of his that were running wild: this he did lest the circumstance of his men being armed should give rise to false and dangerous suspicions respecting his intention; and, at the same time, he invited several of Finow's men to come and partake of the feast. As soon as they had left the fortress, he imparted to them all his real intention to offer Talo his former friendship, and to assure him that he had forgotten the late affair. When they arrived near the plantation, Hala Api Api went on a short distance before, and on entering the house found Talo fast asleep, attended only by his wife and one of her servants: they were both employed in fanning him. He left his spear on the outside of the house, and carried his club in with him. The noise he made on entering awoke Talo; who, imagining that the other had come to assassinate him, started up, seizing his club,

[page] 12

rushed out of the house, and fled: Hala Api Api pursued him, taking with him his spear: his feelings now being greatly hurt to see one fly him so cowardly, who of late had matched himself as his equal, he at length became so exasperated that he threw his spear at him; which, however, fortunately got entangled in some bushes. At this moment Talo was considerably in advance, in consequence of the time which it took the other to go back to the door for his spear: he was noted, however, for his swiftness, and conscious that he should overtake him, he continued the pursuit. Before Talo had crossed the field of high grass adjoining his house, he was under the necessity of throwing off his gnatoo, and very shortly after he threw away his club too. Hala Api Api stopped to pick it up, and thus loaded with two clubs he bounded after him with such extraordinary fleetness, that before they had half crossed the next field he overtook him, and catching hold of him by a wreath of flowers that hung round his neck, exclaimed with generous indignation, "Where did you expect to escape to? Are you a bird that you can fly to the skies; or a spirit that you can vanish to Bolotoo?—Here is your club, which you so cowardly threw away; take it, and learn that

[page] 13

I come not to deprive you of life, but to proffer you again my friendship, which you once prized so highly:" with that he embraced him, and tearing his own gnatoo, gave him half to wear. By this time Hala Api Api's men coming up, he dispatched them immediately to the garrison, to prevent any disturbances which might arise from a false report of this adventure: for a few of Talo's men being near the house, and mistaking Hala Api Api's intention, imagined the fate of their chief inevitable, and had betaken themselves immediately to the garrison, with a view to excite the adherents of Talo to revenge his death; for he was a powerful chief, had belonged to the former garrison, and would undoubtedly have had most of the chiefs of Vavaoo for the avengers of his cause. The two chiefs returned as soon as possible to Felletoa, to shew the people that they had entered again into a friendly alliance. When they arrived they found the whole place in such a state of disturbance, all being up in arms, party against party, that in all probability if they had arrived a little later, war would already have broken out. At the sight of them, matters were soon adjusted; and their mutual friendship became stronger than ever.

A short time after this, the people of Hapai

[page] 14

clearly shewed their intention of commencing hostilities; but were defeated in the very act by the vigilance and bravery of some of Finow's young warriors, among whom Mr. Mariner had the honour to take an active part. One day most of the large sailing canoes were launched, for the double purpose of procuring from some of the outer islands a quantity of coarse sand, and to convey those whose business it was to cut flag-stones for the grave of Tooitonga, to different places for that end. Owing, however, to contrary winds, they were not able to make the shores of Vavaoo that evening; and, in consequence, Finow, who was with them, proposed to remain at the island of Toonga during the night. A short time after, they received intelligence from a fisherman that a canoe, apparently from Hapai, was approaching, and, as was supposed, with an hostile intent, as she had a quantity of arms on board, and many men. In consequence of this, the young warriors requested of Finow leave to proceed in a number of small canoes (as the wind was unfavourable for large ones), and endeavour to cut them off. After a due consultation this was granted; and eleven canoes, manned with the choicest warriors, paddled towards the island of Toonga. As

[page] 15

it was a moonlight night, the enemy saw them, and prepared to receive them, concealing themselves behind certain bushes at a small distance from the beach, where they supposed Finow's men would land: they were right in their conjecture, and, as soon as Finow's warriors were landed, the enemy rushed upon them with their usual yell, and occasioned much disorder and alarm, but soon rallying, they pressed on them in return so closely and bravely, that they were obliged to retreat towards the place where their canoe lay; and here a most severe conflict ensued. Unfortunately, in hurrying on shore from the canoes, Mr. Mariner's ammunition got wet, which rendered his musket of little use, hence he was obliged to employ only a bow and arrows. The enemy, finding themselves so well matched, and thinking they might soon be attacked by forces from the main land (Vavaoo), they embarked as speedily as they could; but, in doing which, they lost ten or twelve men. Mr. Mariner again tried to use his musket, and, after repeated trials, succeeded in shooting the two men that steered (it being a double canoe), after which he returned with his own party to their canoes, learning nineteen of the enemy dead on the field, besides the two killed in the canoe: their

[page] 16

own loss were four, killed on the spot, and three others, who died afterwards of their wounds. The enemy were about sixty in number; themselves about fifty. In this affair Mr. Mariner unfortunately received a violent blow on the knee by a stone from a sling, which lamed him for a considerable length of time. It appeared from the account of a boy, who was wounded and taken prisoner, that the enemy intended to proceed as secretly as possible to the westward of Vavaoo, and, under cover of the night, to make incursions on shore, and do all the mischief in their power.

For the space of about two months after this affair, no circumstance worthy of note took place: no other attack from the people of Hapai was attempted, and all seemed peaceable and quiet. At the end of this period, however, there happened a circumstance, the most fortunate of all to Mr. Mariner, viz. that of his escape. In this time of peace, when he had nothing in which to employ himself, but objects of recreation and amusement, sometimes with Finow, or other chiefs, and sometimes by himself, among several amusements, he would frequently go out for two or three days together, among the neighbouring small islands, on a fishing excursion: as he was one evening

[page] 17

returning homeward in his canoe, after having been out three days, he espied a sail in the westward horizon, just as the sun had descended below it; this heart-cheering sight no sooner caught his attention than he pointed it out to the three men in the canoe with him (his servants that worked on his plantation), and desired them to paddle him on board, holding out to them what an advantageous opportunity now offered itself to enrich themselves with beads, axes, looking-glasses, &c.; an opportunity which they might never again meet with: to this they replied, that they had seen her before, but that their fear of his wishing to go on board prevented them from pointing her out to him, for they had often heard their chiefs say, that they never meant to let him go if they could help it; and hence they were apprehensive that their brains would be knocked out, if they suffered him to escape. Mr. Mariner then condescended to entreat them to pull towards the vessel, promising them very rich rewards. After conversing together, and muttering something between themselves, they told Mr. Mariner, that, notwithstanding the esteem and respect they had for him, they owed it as a duty to their chiefs to refuse his request; and, upon this, they

VOL. II. C

[page] 18

began to paddle towards the nearest shore. Mr. Mariner instantly demanded, in an elevated tone of voice, why they talked about the fear of chiefs; were they not his servants, and had he not a right to act with them as he pleased? He then took in his hand his musket from behind him, when the man who sat next immediately declared, that, if he made any resistance, he would die in opposing him, rather than allow him to escape: upon this, Mr. Mariner summoned up all his strength, and struck him a most violent blow, or rather stab, near the loins, with the muzzle of the piece, exclaiming at the same time, "Ta gi ho Hotooa, co ho mate e*." This lunge produced a dangerous wound, for the musket, being a very old one, had grown quite sharp at the muzzle, and was besides, impelled by the uncommon force with which, inspired by the prospect of escape, he felt himself animated: the man immediately fell flat in the bottom of the canoe, senseless, and scarcely with a groan†. Mr.

* Meaning, literally, "Strike your Hotooa, there's your death!" which are forms of energetic expressions, used like oaths, on extraordinary occasions, calculated to express vengeance.

† This man, whose name was Teoo Fononga, well deserved the fate he met with: he used to beat his wife unmercifully, for which Mr. Mariner had frequently knocked him down with a club: he formerly had a wife who, in time of scarcity, he killed and ate: since that time having several children, more than he wished, he killed a couple of them to get them out of the way. His best quality was being an excellent fisherman, and a very hard-working fellow.

[page] 19

Mariner instantly pulled his legs out straight: he then presented his musket to the other two, who appeared somewhat panic-struck, and threatened to blow out their brains if they did not instantly obey his orders, and pull towards the vessel. They accordingly put about, and made towards her. The one that Mr. Mariner wounded was a piece of a warrior, but the other two had never been in battle, and, as he supposes, did not know but what he could fire off his musket as often as he pleased without loading it: be this as it may, they were now perfectly obedient, and he encouraged them farther, by reminding them that they had a good excuse to make to their chiefs, since it was by compulsion, and not by will, that they acted. In the mean time, he kept a strict eye both upon them and the man in the bottom of the canoe; upon those, lest they should take an opportunity to upset the canoe, and swim to the shore, with which they were well acquainted, and upon this, lest he

C 2

[page] 20

should recover and attempt the same thing, or else make an unexpected attack: fortunately he did not stir the whole night*. They did not come up with the vessel till about daylight next morning, owing to the distance they had to go, for they were about four miles off the north-west part of Vavaoo, and the ship bore west-south-west, about five miles distant, steering under easy sail, to the south end of that island: besides which, they were much fatigued with having pulled about the whole day against a heavy sea, and were short of any provisions, except raw fish. During the whole night, the man in the bottom of the canoe lay perfectly still, and shewed no signs of life, except a slight gurgling noise in his throat, which was heard now and then. As soon as the canoe pulled up along side the brig, Mr. Mariner, without stopping to hail, on the impulse of the moment, jumped up into the main chains, and had liked to have been knocked overboard by the centinel, who took him for a native, for his skin was grown very brown,

* It may be remarked, also, that this was the season for sharks, and their consciences, probably, were not quite clear from having infringed some prohibition or another, in consequence of which, according to their notions, they were liable to be devoured by sharks.

[page] 21

his hair very long, and tied up in a knot, with a turban round the head, and an apron of the leaves of the chi tree round his waist: this disguise would have warranted the conduct of the centinel, but, as soon as Mr. Mariner spoke English, and told him he was an Englishman, he allowed him to come on deck, where he addressed the captain, who cordially shook hands with him. The latter had heard from the captain of a schooner the whole unfortunate affair of the Port au Prince; for the schooner brought away two men from one of these islands during the time that Mr. Mariner was in another quarter, upon some business for Finow.

The captain presented him with a pair of trowsers and a shirt; the latter, it must be said, was neither very new nor very clean; in consequence, he took the pains to wash it, and hang it up in the rigging to dry: in the morning, however, it had disappeared, at the honest instigation of somebody; hence, his whole stock of apparel consisted of the said pair of trowsers; nor did he get better provided till he arrived in China, about seven weeks afterwards. But to return to the subject: the brig proved to be the Favourite, Captain Fisk, from Part Jackson, about 130 tons burthen; had on

[page] 22

board about ninety tons of mother of pearl shells, procured from the Society Islands: she intended to make up her voyage with sandal wood from the Fiji islands, and thence to proceed to China.

Mr. Mariner requested the captain to give the men in the canoe, which brought him, some beads, as a reward for their trouble, &c., and also an axe as a present for Finow. The captain liberally complied; and the canoe left the ship, with a message from Mr. Mariner to the king, requesting him to come on board. As to the wounded man, he was, in all probability, dead; at least the other two seemed to think so by his not stirring, and so took no trouble about him. By this time there were about two hundred small canoes near the vessel, and several large ones, so that the whole people of Vavaoo seemed to be assembled to view the brig, for the whole beach was also crowded. As the vessel was very short of provisions, a very brisk traffic was carried on with the natives by the captain and mate, for yams, hogs, &c.: hence orders were given to the crew not to purchase any trinkets, &c., till they had procured plenty of provisions. About the middle of the day Finow came along side with his sister, and several of her female at-

[page] 23

tendants, bringing off, as a present for Mr. Mariner, five large hogs, and forty large yams, each weighing not less than thirty pounds, and some of the largest sixty or seventy pounds: these things Mr. Mariner begged leave to transfer* to the captain, and presented them accordingly. Notwithstanding repeated messages from the chiefs on shore to Finow, requesting him to return, he resolved to sleep on board that night, if the captain would allow him, which he readily did. The women, however, intimated their wish to return, not liking the thought of trusting their persons among a number of strange men. Mr. Mariner found it very difficult to remove their scruples, by assuring them that they should not be molested. At length, however, they consented to remain, on his promise to take care of them, and to roll them all up in a sail, in which state they laid the whole night in the steerage; and, as they said, slept comfortably. As to Finow, he was very well contented with sleeping on a sail on the cabin deck. As the weather was remarkably fine, the brig did not come to an anchor, but stood off and on during the whole of the night. At day-light canoes came along

* It is a very common thing among the natives to transfer a .

[page] 24

side in great numbers; but from prudent motives, dictated by former disasters, no more than three of the natives were allowed to come on board at a time, six centinels being kept constantly on deck for that purpose. In the canoes were several chiefs, who came to request Finow to return on shore, as the people were greatly alarmed lest he should form a determination of going to Papalangi (land of white people). They brought off some cava for him, but which he declined drinking, saying that he had tasted some on board (wine) which was far preferable: indeed, he considered it so much superior, that the thoughts of cava quite disgusted him. He made a hearty dinner at the captain's table—ate plenty of roast pork, with which he admired very much the flavour of the sage and onions: the fowls he cared very little about, but partook of some made dishes. The ladies also ate very heartily; but Finow handled a knife and fork, though for the first time in his life, with very great dexterity; sometimes, indeed, his majesty forgot himself a little, and laid hold of the meat with his fingers; but, instantly recollecting that he was doing wrong, he would put it down again, exclaiming, wóe! gooa te gnalo! Eh! I forget myself!

[page] 25

The natural politeness which he evinced on every occasion charmed the captain and the officers so much, that they could not help acknowledging that it far surpassed any other instance of good manners they had witnessed among the inhabitants of the South Sea islands; and not only in behaviour, but in intelligence, he seemed to excel: his inquiries about the use and application of what he saw were frequent, and indeed troublesome; but then his deportment was so affable, and his manner so truly polite, that nobody could be offended with him. He requested permission to lie down in the captain's bed, that he might be able to say what none of the people of Vavaoo could boast of, that he had been in a Papalangi bed. Permission being readily granted, he lay down, and was delighted with his situation; and said, that being now in an English bed, he could fancy himself in England. Some time after, being left in the cabin by himself, though watched unknown to him, he did not offer to take, or even touch, a single bead, or any thing else, excepting the captain's hat; but which, not choosing to put on without asking leave, he went on deck on purpose to request Mr. Mariner to obtain permission of

[page] 26

the captain for so great a liberty. So different was he from the generality of these islanders, who, stimulated by curiosity, if not by a less honest motive, would not scruple to take a man's hat off his head, unbidden, twirl it about, and be very careless about returning it, if not reminded by the owner.

About the middle of the day Finow went on shore to quiet the people, who were become very clamorous on account of his long stay: but soon after he returned on board, bringing with him a quantity of cooked victuals, ripe bananas, &c. for the crew; and also a present for the captain, consisting of a valuable spear and club, a large bale of gnatoo, a large hog, a hundred small yams, and two canoes' load of cocoa-nuts.

So delighted was Finow with every thing he saw on board, so high an opinion had he of the character of the Papalangis, and so desirous was he of arriving at those accomplishments which raised them so high above the character of the Tonga people, that he could not help several times expressing his wish to accompany Mr. Mariner to England. On the third day, which was the day of the brig's departure, his importunities on the subject be-

[page] 27

came extremely urgent, so much so, that Mr. Mariner could not refrain expressing them to the captain; but who refused (as might be expected) to accede to a wish which seemed to promise no future good to an individual in Finow's circumstances, arriving, in a strange country, without protection, and without patronage. This was a sore disappointment to him, as it must have been to one who was willing to make such large sacrifices to the accomplishment of his hopes;—to one who would have resigned a princely state and dignity, and all the respect paid by obedient subjects to an arbitrary monarch, for the sake of visiting a country, where, as Mr. Mariner explained to him, he could expect at best but a very inferior mode of life, comparing it with what he had been accustomed to. But the arguments this gentleman used were all in vain; Finow would not,—could not be divested of his wishes: he thought if he could but learn to read and write, and think like a Papalangi, that a state of poverty, with such high accomplishments, was far superior to regal authority in a state of ignorance.

Seeing, however, that his wish was this time at least destined to be thwarted, he made his friend solemnly promise,—and before their final

[page] 28

separation, made him again repeat that promise, and swear to the fulfilment of it by his father, and by the god who governed him, that he would some time or another return, or endeavour to return in a large canoe, (a ship,) and take him away with him to England; and in case his subjects should stand averse to such a measure, that he would complete his project by force of arms. Mr. Mariner acceded to this promise; and Finow embraced him, and shed tears.

It would be very interesting to know what would be the result of removing an individual, of Finow's disposition and intellectual powers, from the state of society in which he had been brought up, into a civilized country; into a scene so widely different from every thing he had been accustomed to, where every circumstance would be new, and every object calculated to draw forth the powers of his natural understanding, to judge of their propriety, absurdity, or excellence. Finow's intellect, as we shall by and by more clearly see, when we take a survey of his character, was far, very far above the common: there was interwoven in the very texture of his mind a spirit of philosophical inquiry, directed by the best of all motives—the desire of human improvement;—

[page] 29

not the offspring of common curiosity, but that noble impulse, which goads the mind on in the pursuit of knowledge, at whatever risk, and with whatsoever suffering. But we must leave this subject for the present, to take a farther view of the transactions on board.

The captain had a quantity of pearl oyster-shells, which are considered by the natives a very beautiful ornament, and very scarce among them, as those which they have are not capable of being so finely polished: these attracted Finow's fancy, which the captain observing, made him a present of several; but, however, he did not direct his attention to mere matters of ornament: he reflected that he had very few gun-flints on shore; and he ventured, in a very modest manner, to ask the captain for a supply of an article that would be so useful to him* in defending his newly established kingdom of Vavaoo against the encroachments of the Hapai people; and the captain liberally complied with his request.

Mr. Mariner had on shore, in a concealed place, the journal of the Port au Prince, which he was now desirous of securing. The reader may here be reminded, that in the early part

* Finow knew the use of a musket exceedingly well, and was a very good shot.

[page] 30

of Mr. Mariner's residence at these islands, the late king ordered him to give up his books and papers, which were afterwards burnt, as instruments of witchcraft; it happened, however, fortunately, that he had concealed this journal beneath the matting of the house, and thus it escaped the flames. After that period, reflecting what a risk there was of its being discovered, whether he left it there, or carried it about with him, particularly as the times were so unsettled, he confided it to the care of his adopted mother, Máfe Hábe, who faithfully kept it in her possession, concealed in the middle of a bale of gnatoo; which, along with others, was always conveyed to whatever island or distant place she went to reside at: and when she left Vavaoo to go and live with her father at the Hapai islands, she gave it up to Mr. Mariner, who concealed it in the middle of a barrel of gunpowder, without the knowledge of any one else; for although he had at that time considerable power and influence, and a sufficient number of confidential friends, he thought it best to conceal it in a safe place, where no native was likely to find it, and consequently no ridiculous prejudice likely to deprive him of it. To get it again into his possession, he obtained the captain's consent to

[page] 31

detain Finow Fiji (the king's uncle) on board till the journal was brought to him; and accordingly two natives were dispatched, with directions where to find it: they had orders, at the same time, to bring back with them three Englishmen that were on shore, viz. James Waters, Thomas Brown, and Thomas Dawson. In the mean while Finow Fiji, on understanding that he was detained a prisoner, turned very pale, and was evidently greatly alarmed: and even when Mr. Mariner explained to him the cause, he seemed still to think every thing was not right; and expressed his apprehension that they were going to take him to England to answer for the crime of the Hapai people, in taking the Port au Prince, and murdering the crew: the other assured him that his fears were groundless; for, as he was not a party concerned in that sad affair, the English people would never think of punishing the innocent for the guilty: "True!" he replied, "and you know that I have always befriended you, and that I am not a treacherous character; and that rather than assist in taking a Papalangi ship, I would do all that lay in my power to prevent such an outrage." To this Mr. Mariner cordially gave his assent, and the chief seemed quite satisfied: his people in the

[page] 32

canoes were, however, far from being so,—they raised great clamours, and loudly demanded his liberation; and even his own assurances could scarcely remove their apprehensions. Finow Fiji told Mr. Mariner that he should have been particularly sorry to have been taken away, when his nephew was just in the infancy of his reign, and might want his counsel and advice, and thus be deprived of the pleasure of seeing him govern prosperously, and making his people happy, which, from his ability and excellent disposition, he had no doubt would be the case. At length the canoe returned with the journal and the Englishmen. Thomas Waters was not disposed, however, to return to England: he was an old man, and had become infirm, and he reflected that it would be a difficult matter for him to get his bread at home; and as he enjoyed at Vavaoo every convenience that he could desire, he chose to end his days there.

Finow's sister, a girl of about fifteen years of age, went on shore, and brought on board several other women of rank, who were all greatly pleased that they were allowed to come into the ship and satisfy their curiosity. Finow's sister, who was a very beautiful, lively girl, proposed, in joke, to go to England, and

[page] 33

see the white women: she asked if they would allow her to wear the Tonga dress, "though perhaps," she said, "that would not do in such a cold country in the winter season. I don't know what I should do at that time: but Togi tells me that you have hot-houses for plants from warm climates, so I should like to live all winter in a hot-house. Could I bathe there two or three times a day without being seen? I wonder whether I should stand a chance of getting a husband; but my skin is so brown, I suppose none of the young papalangi men would have me; and it would be a great pity to leave so many handsome young chiefs at Vavaoo, and go to England to live a single life.—If I were to go to England I would amass a great quantity of beads, and then I should like to return to Tonga, because in England beads are so common that nobody would admire me for wearing them, and I should not have the pleasure of being envied."—She said, laughing, that either the white men must make very kind and good tempered husbands, or else the white women must have very little spirit, for them to live so long together without parting. She thought the custom of having only one wife a very good one, provided the husband loved her: if not, it was a very bad one, because he would

VOL. II. D

[page] 34

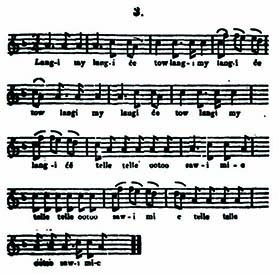

tyrannize over her the more, whereas if his attention was divided between five or six, and he did not behave kindly towards them, it would be very easy to deceive him.—These observations, of which Mr. Mariner was interpreter, afforded very great amusement. Finow, the late Tooitonga's son (about 12 years of age,) and the females, now commenced dancing and singing, at the request of the captain, and which gave the ship's company much entertainment.

Before the ship's departure, Mr. Mariner was charged with several messages from the chiefs of Vavaoo to those of Hapai. Among others, Finow sent his strong recommendations to Toobo Toa to be contented with the Hapai islands, and not to think of invading Vavaoo; to stay and look to the prosperity of his own deminions, for that was the way to preserve peace and happiness: "Tell him again," said he, "that the best way to make a country powerful and strong against all enemies is to cultivate it well, for then the people have something worth fighting for, and will defend it with invincible bravery; I have adopted this plan, and his attempts upon Vavaoo will be in vain!" — Several warriors sent insulting messages to the Hapai people, saying "We shall be very happy

[page] 35

to see them at Vavaoo, and will take care to entertain them well, and give them plenty of bearded spears to eat, and besides, we have got some excellent Toa wood (clubs) of which we shall be glad to give them an additional treat! we hope they will come and see us before they shall have worn out the fine Vavaoo gnatoo of which they took away so much when they visited us last;" (alluding to their late unsuccessful expedition.)—Hala Api Api had considerable property at the island of Foa, and he sent a message to an old mataboole residing there, (who had been a faithful servant of his father,) to gather all his moveable property, consisting of some whale's teeth and a considerable quantity of Hamoa mats, and deposit it in a house of his upon the beach, that he might come some time under cover of the night, and secure it.

Some of the Vavaoo warriors proposed a plan, if the captain would lend them the use of the ship, to kill Toobo Toa and his greatest fighting men, in revenge for his murder of their lamented chief, the brave Toobo Neuha. The plan was for about two hundred of the choicest Vavaoo warriors to conceal themselves below on board the Favourite, and when she arrived at the Hapai islands, Toobo Toa and many other considerable chiefs and warriors were to be invited on

D 2

[page] 36

board, and then the boarding nettings being hauled up that none might escape, at a signal to be given the Vavaoo people were to rush on deck and dispatch them all with their clubs. To this, of course, the captain did not consent.

Finow consigned to Mr. Mariner's care a present for Mafi Habe, consisting of a bale of fine Vavaoo gnatoo and five or six strings of handsome beads, and also his ofa tai-toogo ("love unceasing.") His wife also sent her a present of three valuable Hamoa mats, with her ofa tai-toogo.

The ship now prepared to take her departure from Vavaoo, and Mr. Mariner to take leave of his Vavaoo friends, probably for ever: the king again embraced him in the most affectionate manner, made him repeat his promises to return, if possible, to Tonga, and take him back to England, that he might learn to read books of history, study astronomy, and thus acquire a papalangi mind. As to the government of Vavaoo, he said that might be consigned to the care of his uncle, who would make a good king, for he was a brave man, a wise man, and withal a lover of peace. At this parting, abundance of tears were shed on both sides, Finow returned to his canoe with a heavy heart, and Mr. Mariner felt all the sweet bitterness of parting from much loved

[page] 37

friends to visit one's native country: he bade a long adieu to the brave and wise Finow Fiji,—to the spirited and heroic Hala Api Api,—natural characters which want of opportunity render scarce, or which are not observable amid the bustle and business of civilized life. The canoe returned to the beach,—the ship got under way, and steered her course to the Hapai islands, leaving Vavaoo and all her flourishing plantations lessening in the distance.

[page] 38

CHAP. XVI.

Preliminary remarks—Anecdote of the late king—Character of the present king—Parallel between him and his father—His humanity—His understanding—Anecdote of him respecting a gun-lock—Respecting the pulse—His love of astronomical knowledge—His observations upon European acquirements—His remarks concerning the antipodes—Anecdote of him respecting the mariner's compass—His attention to the arts.—Cursory view of the character of Finow Fiji—His early warlike propensities—His peaceable disposition and wisdom—Cursory character of Hala Api Api—His mischievous disposition—His generosity, wisdom, heroic bravery, and occasional moderation—His swiftness of foot—Arrival of the Favourite at the Hapai islands—Generosity of Robert Brown—Anecdote of the gunner of the Port au Prince—Three men of the Port au Prince received on board—Anecdote of an Hapai warrior—Excuses and apologies of the Hapai people in regard to the capture of the Port au Prince—The Favourite departs for the Fiji islands—Remarks on the conduct of one of the Englishmen left behind—An account of the intentions of the Hapai people towards Captain Cook—Anecdote respecting the death of this great man—Arrival of the Favourite at the island of Pau—Some account of the natives, and of the white people there—Departure of the ship from the Fiji islands, and her arrival in Macao roads—Mr. Mariner's reception by Captain Ross and by Captain Welbank—His arrival in England—Concluding observations.

[page] 39

IN taking leave of those with whom we have long resided, and whose ways and habits we have got accustomed to, whose virtues have gained our esteem, and whose kindnesses have won our affection;—in leaving them and the scenes that surround them, never to return, the human heart feels a sad void, which no lapse of time, no occupations, no new friendships seem likely ever to fill up: all their good qualities rush upon the mind in new and lively colours, all their faults appear amiable weaknesses essential to their character. When we lose a friend by death, we compare it, by way of consolation, to a long absence at a long distance; but it is equally just to reverse the comparison, and to say of a separation like this that it is as death, which at one cruel stroke deprives us of many friends!

Mr. Mariner, as he looked towards Vavaoo, now fast declining in the horizon, experienced sentiments which he never before had felt to such a degree: his faithful memory presented a thousand little incidents in rapid succession, which he wondered he had never before sufficiently noticed: the late king, though lying in the fytoca of his ancestors, was now as much alive to him as his son, or Finow Fiji, or Hala Api Api, or any other friend that he had just part-

[page] 40

ed with. He recollected how often, at his request, he had laid down upon the same mat with him, in the evening, to talk about the king of England, and after a long conversation, when Finow supposed him to be asleep, he would lay his hand gently upon his forehead and say, "Poor papalangi! what a distance his country is off! Very likely his father and mother are now talking about him, and comforting themselves by saying 'perhaps to-morrow a ship will arrive and bring our son back to us.'" The next moment all the amiable qualifications of the present king presented themselves to his view, and as we have not yet drawn a character so well worthy to be noticed, we shall now attempt to display it in its true and native colours, trusting that it will afford a considerable share of pleasure to the generality of readers.

Finow, the present king of Vavaoo, about twenty-five years of age, was in stature 5 feet 10 inches; well proportioned, athletic, and graceful; his countenance displayed a beautiful expression of openness and sincerity; his features, taking them altogether, were not quite so strongly marked, nor was his forehead quite so high as those of his father, nevertheless they expressed an ample store of intellect. Notwithstanding the benevolent mildness and play of

[page] 41

good humour in his countenance, his eye shot forth a penetrating look of enquiry from beneath a prominent brow that seemed to be the seat of intelligence: the lower part of his face was well made; his teeth were very white, his lips seemed ever ready to express something good humoured or witty. His whole physiognomy, compared with that of his late father, possessed less dignity, but more benevolence; less chief-like superiority, but more intellect: his whole exterior was calculated to win the esteem of the wise and good, while that of his father was well adapted to command the admiration of the multitude. The character of the father was associated with the sublime and powerful; that of the son with the beautiful and engaging. His language was strong, concise, and expressive, with a voice powerful, deep, and melodious. His eloquence fell short of effect compared with that of his father, but he did not possess the art of dissimulation. The speech which he made on coming into power struck all the matabooles with astonishment; they woundered to hear so much eloquence tempered with wisdom, so much modesty combined with ness, proceed from the lips of so young a man; and they prophesied well of him,—that he would reign in the affections of his people,

[page] 42

and have no conspiracies or civil disturbances to fear. His general deportment was engaging; his step firm, manly and graceful: he excelled in all athletic sports, racing, wrestling, boxing, and club-fighting: he was cool and courageous, but a lover of peace. He was fond of mirth and good humour: he was a most graceful dancer: he was passionately delighted with romantic scenery, poetry, and vocal concerts: these last had been set aside, in a great measure, during his father's warlike reign; but when the son came into power, he revived them, and had bands of professed singers at his house almost every night. He used to say that the song*, amused men's minds, and made them accord with each other,—caused them to love their country; and to hate conspiracies. He was of a most humane and benevolent disposition, but far, very far from being weak in this respect, for he was a lover of justice: the people readily referred to him for a decision of their private quarrels, on which occasions he was never thought to have judged rashly; if he could not immediately decide, he adjourned the cause till the next day, and in the mean time took the trouble to enquire further particulars of those who knew more of

* Their songs are mostly descriptive of sceuery.

[page] 43

the matter. If he was severe with any body, it was with his own servants, for he used to say that his father was too partial to them, by which means they had become assuming, taking upon themselves the character of chiefs, and oppressing others of the lower orders, but now he would make them know their proper places. If they did any thing wrong, they trembled in his presence. Nevertheless, the benevolence of his heart was wonderfully expressed in his manners: while he was yet on board the ship, Captain Fisk desired Mr. Mariner to tell him that it would be bad policy for him ever to attempt taking a ship, as it would prevent other ships coming to trade with them, or, if they came at all, it might be to punish him and his people for their treachery: as soon as Finow understood what the captain said, he made a step forward to Mr. Mariner, and taking his hand, pressed it cordially between his*, saying with tears in his eyes, and a most benevolent and grateful expression of feature, "Tell the chief that I shall always consider the Papalangies as my relations,—as my dearest brothers; and rather

* He had learnt the action of taking the hand from the Englishmen there, and used to say it was the most friendly and most expressive way of denoting one's feeling of sincerity.

[page] 44

would I lose my life than take any thing from them by force or treachery." He had scarcely finished speaking when the captain exclaimed, "I see, I see what he means,—you need not translate me that!

Finow's intellect was also very extraordinary, that is to say, it was naturally very strong, and was very little obscured by prejudices: we have seen several instances of the wisdom of his conduct, and a few anecdotes will serve to shew that his specific reasoning faculty was very far above the common. He had learnt the mechanism of a gun-lock by his own pure investigation: one day, on taking off the lock of a pistol to clean it, he was astonished to find it somewhat differently contrived, and a little more complicate than the common lock, which he had thought so clever and perfect that he could not conceive any thing better: on seeing this, however, he was somewhat puzzled, at first with the mechanism, and afterwards with its superiority to the common lock, but he would not have it explained to him; it was an interesting puzzle, which he wished to have the pleasure of solving himself: at length he succeeded, and was as pleased as if he had found a treasure; and in the afternoon at cava, he was not contented till he had made all his chiefs and matabooles under-

[page] 45

stand it also. He did not know the existence of the pulse till Mr. Mariner informed him of it, and made him feel his own, at which he was greatly surprised, and wanted to know how the Papalangies first found it out: he was informed at the same time, that the pulse was influenced by various diseases and passions of the mind; and that in most parts of the world, those whose profession it was to cure diseases often judged of the state of the complaint by the pulse: upon which he went about to two or three that were ill to feel their pulses, and was much delighted with the new discovery. A few days afterwards one of his servants very much offended him by some unwarrantable act, upon which he became violently angry, but on a sudden the thought struck him of the association between the passions and the pulse, and immediately applying his hand to his wrist, he found it beating violently, upon which, turning to Mr. Mariner, he said, you are quite right; and it put him in such good humour that the servant got off with a mild remonstrance, which astonished the fellow very much, as he did not understand the cause, and was sitting trembling from head to foot, in full expectation of a beating.

Mr. Mariner explained to him the form and

[page] 46

general laws of the solar system; the magnificent idea of the revolutions of the planets, the diurnal revolution of the earth, its rotundity, the doctrine of gravity, the antipodes, the cause of the changes of the seasons, the borrowed light of the moon, the ebb and flow of the tides, &c.—These were his frequent themes of discourse, and objects of his fine understanding;—they pleased him, astonished him, and filled him with intense desire to know more than Mr. Mariner was able to communicate. He lamented the ignorance of the Tonga people; he was amazed at the wisdom of the Papalangies, and he wished to visit them, that he might acquire a mind like theirs. The doctrine of the sun's central situation and the consequent revolution of the planets he thought so sublime, and so like what he supposed might be the ideas and inventions of a God, that he could not help believing it, although it was not quite clear to his understanding. What he seemed least to comprehend was how it happened that the antipodes did not fall into the sky below (as he expressed it), for he could not free his mind from the notion of absolute up and down: but he said he had no doubt, if he could learn to read and write, and think like a Papalangi, that he should be able to comprehend it as easily as a Papalangi,

[page] 47

for, he added, the minds of the Papalangies are as superior to the minds of the Tonga people as iron axes are superior to stone axes!—He did not, however, suppose that the minds of white people were essentially superior to the minds of others; but that they were more clear in consequence of habitual reflection and study, and the use of writing, by which a man could leave behind him all that he had learnt in his life-time.

One day as Mr. Mariner was sharpening an axe, and Finow was turning the grind-stone, the latter observed that the top of the stone was not only always wet, but so replete with water that it was constantly flying off in abundance on the application of the axe; this on a sudden thought puzzled him; it seemed to him strange that the superabundance of water should not run off before it got to the top: Mr. Mariner began his explanation, thus, "In consequence of the quick successive revolutions of the stone"—when on a sudden Finow eagerly exclaimed (as if a new light had shot across his mind) "Now I understand why the antipodes do not fall off the earth,—it is in consequence of the earth's quick revolution!"—This was a false explanation, and he himself soon saw that it was, much to his disappointment; but it shews

[page] 48

the activity of his mind, and how eager it was to seize every idea with avidity that seemed to cast a radiance upon the object of his research.

On another occasion they were returning to Vavaoo from the Hapai islands, where the king had been to fetch some of his property, consisting chiefly of things which originally belonged to the officers of the Port au Prince: among others there was a box containing sundry small articles and a pocket compass; the latter he did not know the use of, and had scarcely yet examined. During the whole day it was nearly calm, and the paddles were for the most part used: a breeze, however, sprang up after dark, accompanied with a thick mist: taking it for granted that the wind was in its usual direction, they steered the canoe accordingly, and sailed for about two hours at the rate of seven knots an hour. As they did not reach the shores of Vavaoo, the thought now occurred to Mr. Mariner that the wind might possibly have changed, and in that case, having no star for a guide, a continuance of their course would be exceedingly perilous; he therefore searched for the compass to judge of their direction, when he was much alarmed to find that the wind had chopped round nearly one quarter of the compass. He mentioned this to the king, but

[page] 49

he would not believe that such a trifling instrument could tell which way the wind was; and neither he, nor any other chief on board, was willing to trust their lives to it: if what the compass said was true, they must indeed be running out to sea to an alarming distance; and as night was already set in, and the gale strong, their situation was perilous. Most on board, however, thought that this was a trick of Mr. Mariner to get them out to some distant land, that he might afterwards escape to Papalangi; and even Finow began to doubt his sincerity. Thus he was in an awkward predicament: he was certain they were going wrong, but the difficulty was how to convince them of what was now, in all probability, essential to their existence, for the weather threatened to be bad, and it seemed likely that the night would continue very dark. At length, he pledged his existence for their safety, if they would but follow his advice, and suffer him to direct their course; and that they should kill him if they did not discover Vavaoo, or some of the other islands, by sun-rise. This pledge was rather hazardous to him, but it would have been still more so, for them all, to have continued the course they were then in. They at length consented; the canoe was immediately close hauled, and Mr.

VOL. II. E

[page] 50

Mariner directed their steering; the gale luckily remained nearly steady during the night; all on board were in great anxiety during the whole time, and Mr. Mariner not the least so among them. In the morning, as soon as the light was sufficiently strong, a man, who was sent up to the mast-head, discovered land, to the great relief of their anxiety; and the rising sun soon enabled them to recognize the shores of Vavaoo, to their unspeakable joy, and, in particular, to the wonder and amazement of Finow, who did not know how to express his astonishment sufficiently at the extraordinary properties of the compass. How such a little instrument could give information of such vast importance, produced in him a sort of respectful veneration, that amounted to what was little short of idolatry; for finding that Mr. Mariner could not explain why it always pointed more or less to the north, he could hardly be persuaded but what it was inspired by a hotooa. He was so pleased with this property of the compass, that he almost always carried it about him afterwards: using it much oftener than was necessary, both at sea and on shore, for it always seemed a new thing to him.

It may easily be supposed, that Finow, with such an enquiring mind as he possessed, took

[page] 51

delight in every thing that afforded him instruction, or satisfied his curiosity; not only in regard to things that were very extraordinary, but those also that were moderately common and useful. He was accustomed, therefore, to visit the houses of canoe-builders and carpenters, that he might learn their respective arts, and he often made very judicious observations. He very frequently went into the country to inspect the plantations, and became a very good agriculturist, setting an example to all the young chiefs, that they might learn what was useful, and employ their time profitably. He used to say, that the best way to enjoy one's food was to make oneself hungry by attending to the cultivation of it.

There were many individuals at the Tonga islands besides Finow, that possessed uncommon intellect, as well as good disposition of heart, but none of them seemed endowed with that extraordinary desire of investigation which so strongly characterised the king. Among the most remarkable of these was his uncle, Finow Fiji, and his friend, Hala A'pi A'pi. The first of these was venerated for his wisdom; a quality which he derived rather from his great experience, steady temper of mind, and natural solid judgment, than from the light of extraordinary

E 2

[page] 52

intellectual research. Nevertheless, this divine quality was marked in his countenance; there was something graceful and venerable about his forehead and brow that commanded respect and confidence. He had no quick sparkling look of ardour, nor fire of impetuosity, but his deep-seated eye seemed to speculate deliberately upon objects of importance and utility. His whole physiognomy was overshadowed by a cast of sublime melancholy, but he had been one of the greatest warriors that Tonga ever produced. The islands of Fiji, (whence he derived his name), had been the scenes of his achievements, and the stories recorded of him equalled those of romance; his arm had dispensed death to many a Fiji warrior, whose surviving friends still recollect the terror of his name; but all the warlike propensities of this mighty chieftain seemed now absorbed in a conviction of the vanity and absurdity of useless bloodshed; and nothing seemed now to afford him a greater pleasure, (next to giving counsel to those who asked it), than to play with little children, and to mingle with unwonted cheerfulness in their amusements. Finow Fiji was perhaps about fifty years of age,* and was become rather cor-

* No native of Tonga knows his age, for no account of the revolution of years is kept.

[page] 53

pulent: his whole demeanour was not erect, powerful, and commanding, like that of his brother, the late king, but his slow step and steady action shewed something of solid worth in his character, that wrought respect in the beholder without any mixture of fear.—It has just been said, that Finow Fiji performed most of his warlike feats at the Fiji islands: the greater part of the time that he was there, Hala Api Api,* though a much younger man, (about thirty,) was his constant friend and companion; they always fought near together, and were said to have owed their lives to each other thirty or forty times over. The mutual friendship of these two was very great, although their characters were widely different in many respects.

To form a tolerable idea of Hala Api Api, we must conceive to ourselves a slim yet athletic and active figure, of a middling stature, full of fire and impetuosity; endowed with a mind replete with the most romantic notions of heroic bravery: full of mischief (without malignity), wrought up with the most exuberant generosity: the heat and inconstancy of youth was in him strangely mixed with the steadiness and wisdom of age: no man performed more mis-

* The young chief whose conduct towards Talo has been related.

[page] 54

chievous tricks than he, at the expense of the lower orders, and yet they all liked him: if any other chief oppressed them, they flew to Hala Api Api for redress, and he always defended their cause as if it was his own, often at the risk of his life; and this he did seemingly from pure motives of pity. He would weep at the distress of which they complained, and the next moment his eyes would flash with indignation, at the injustice of the oppressor, and seizing his club, he would sally forth to redress their wrongs. If he committed any depredations himself, he would sometimes be equally sorry, and make ample reparation. On other occasions, however, his mind would remain for a considerable length of time in the same wild and ungovernable disposition; and the report of his depredations would reach the king's ears (the late king), who would say, "what shall I do with this Hala Api Api? I believe I must kill him." But Hala Api Api neither feared death nor the king, nor any other power. There was nobody but what liked him, and yet every body feared him. His mind was like a powerful flame, constantly in action, and constantly feeding upon every thing that could be made food of. Talk to him about battles, and he looked as if he were inspired. Tell him a pathetic story, and the tears would run down his cheeks faster than you could

[page] 55

count them. Tell him a good joke, and there was nobody would laugh more heartily than he. The late king used to say, that Hala Api Api would prefer two days hard fighting without food more readily than the most peaceable man would two days food without fighting. No sooner did the younger Finow come to be king, than his friend, Hala Api Api, (to the astonishment of every body), left off his mischievous tricks, and ceased to commit any acts of depredation. On being asked, by Mr. Mariner, his reason for this, he replied:—"The present king is a young man, without much experience, and I think I ought not to throw obstacles in the way of his peaceable government, by making him uneasy, or creating disturbances. The old king had great experience, and knew how to quell disturbances: besides, he was fond of fighting, and so I gratified my humour, without caring about the consequences; but such conduct now might be very bad for the country." Hala Api Api's countenance, and his whole figure, very well pourtrayed his character: his small quick eye gave an idea of wonderful activity; and, though he looked as if he were a mischievous fellow, yet his general physiognomy expressed much generosity, good sense, and understanding: his whole body was exceedingly well proportioned, and he was considered one of the

[page] 56

best made men at Vavaoo. He was beyond conception swift of foot; to see him run, you would think he outstripped the wind; the grass seemed not to bend beneath his feet, and on the beach you would scarcely expect to find the traces of his footstep.

Such is a general sketch of some of the principal men of Vavaoo, who had always behaved in a most friendly way to Mr. Mariner, and whom of course he could not help feeling very great regret at parting with. His attention was soon occupied, however, by the arrival of the ship at the Hapai islands, where she stood off and on during the time she remained (two days) between the islands of Haano and Lefooga.

A vast number of canoes came alongside from the neighbouring islands, and several of the chiefs were allowed to come on board. Mr. Mariner now took the earliest opportunity, in the first place, to procure the escape of any Englishmen who might be there; and, secondly, to fulfil the sundry commissions he had received from his Vavaoo friends. The cooper of the Port au Prince, who, it will be recollected, was the last man that remained on board with him, was now under the protection and in the service of Voona, who, with Toobo Toa, came on board the Favourite. He, therefore, immediately took

[page] 57

proper means to get the cooper (Robert Brown) on board, and had the pleasure of succeeding. Other Englishmen were at the more distant islands, and Robert Brown most generously undertook to go for them, at the risk of being detained, or of the ship's departure without him. The captain advised him not to go, if he valued his own liberty; but he replied, "it would be very hard indeed if one Englishman could not assist another, although it was at his own risk." He was particularly interested in the fate of Samuel Carlton, the boatswain of the Port au Prince, who had always been his intimate friend. This man's case was rather hard: when he was in England, he was about to be married to a young woman to whom he had been long attached; but thinking he had not yet sufficient to begin the world with, in some business on shore, he thought it would be more prudent to go first another voyage and increase his means, and accordingly he entered on board the Port au Prince. During his residence at the Hapai islands he was always in a low and almost desponding state of mind, and his friend Robert Brown most cordially participated in his distress. At the moment we are speaking of, the latter conjectured that he was at Namooca, and was resolved to run the greatest risks to effect

[page] 58

his escape, as well as that of others whom he supposed to be with him, particularly George Wood, the carpenter's mate. He accordingly, after much trouble, and offer of considerable rewards, persuaded four of the natives to accompany him to Namooca, a distance of fifty miles, in a single sailing canoe, where, when he arrived, to his great mortification, he found that the object of his search, as well as two or three other Englishmen, were gone to the island of Tonga, to assist the friends of Toobo Toa, in the garrison of Hihifo. He then deliberated, whether he should push on to Tonga, a distance of sixty miles farther; but the men refused to take him, and he was obliged to return, bringing with him Emanuel Perez, a Spaniard, and Josef, a black, who both belonged to the Port au Prince. In the mean time, three more Englishmen arrived on board, viz. Nicholas Blake (seaman), and Thomas Eversfield and Willliam Brown, (lads of 17 years of age), who afterwards returned on shore, refusing to go away*.

* It must be mentioned, that two or three men belonging to the Port au Prince got away about eighteen months before, in a schooner which happened to touch at Vavaoo. Among these was William Towel, who now resides in Cross-street, Westmorland-place, City-road, and follows the business of a hair-dresser. Mr. Mariner was at that period at the Hapai islands, and knew nothing of the schooner's arrival.

[page] 59

Mr. Mariner was much disappointed on finding that his adopted mother, Mafi Habe, was gone to a distant island to see some friend; the presents that he brought for her from the king and queen he left, therefore, with one of her relations, to be given to her as soon as she returned, with some presents from himself, to keep in remembrance of him. He sent on shore, to the island of Foa, for the old mataboole, the confident of Hala Api Api, and communicated to him the message from that chief. He also communicated to Toobo Toa the king's advice to him, viz. never to attempt the invasion of Vavaoo, but to confine himself to the cultivation and prosperity of his own islands: to which he replied, that war was necessary to keep the minds of his chiefs employed, that they might not meditate conspiracies; and that he should, therefore, direct his arms against some of the garrisons at the island of Tonga. He had the greatest respect, he said, for Finow's family; but he could not help it if some of his chiefs (as on the late occasion), made attacks upon Vavaoo, for want of other employment. One of the warriors who was engaged in that unsuccessful expedition was now on board: he was wounded on that

[page] 60

occasion in the arm by a ball from Mr. Mariner's musket. About a twelvemonth before, he laid a wager with Mr. Mariner that he could not hit a mark which he put on a cocoa-nut tree at a certain distance with his musket: the bet was a pig. Mr. Mariner accepted the wager, and the king promised to pay the pig if he lost: it happened, however, that he missed, and the king lost his pig. The warrior, as soon as he saw Mr. Mariner on board, came up to him, and said, smiling, "I find you can shoot better than you did at the cocoa-nut tree." Mr. Mariner enquired after his wound, and was happy to find that it had got nearly well. The ball had passed through the fleshy part of the arm; his Hapai surgeon, however, had laid the wound considerably open, and managed it very well.

It was very ludicrous to hear the different strange excuses and apologies made by the natives, in regard to the affair of the Port au Prince, with a view to persuade the captain that they had nothing to do with it. Many said that they were not on board; and knew nothing about it till it was all over, and then they were very sorry indeed to hear of it, and thought it a very bad thing: one man acknowledged that he was on board, being there out of curiosity, but that he knew nothing beforehand of

[page] 61

the conspiracy, and took no part in it: another acknowledged that he was on board under like circumstances, and he was quite astonished when they began to kill the white men; he declared, that he saved one white man's life, but while he was turning round to save another's, the man whose life he had just saved got killed on the spot. Several regretted they were not at Lefooga at the time, as they were sure they could have saved several of the Papalangies: they all affirmed that they were very fond of the Papalangies!!

Toobo Toa, and Voona, both asked Mr. Mariner why he had chosen to remain at Vavaoo, and if they had not behaved equally kind to him as the king, or any of the Vavaoo chiefs. To this he replied, that he preferred Vavaoo to the Hapai islands, as the latter place brought to his mind many disagreeable remembrances: it was where his ship had been destroyed, and where he had met with many insults from the lower orders on his first arrival; besides, he acknowledged that he preferred the disposition of the Vavaoo people generally, and that he thought it would be highly ungrateful in him to leave the protection of a family that had befriended him all along.

After two days stay at the Hapai islands,

[page] 62