[frontispiece]

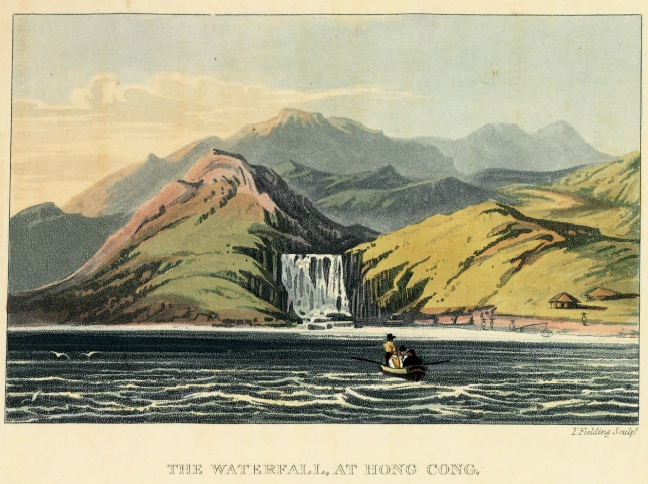

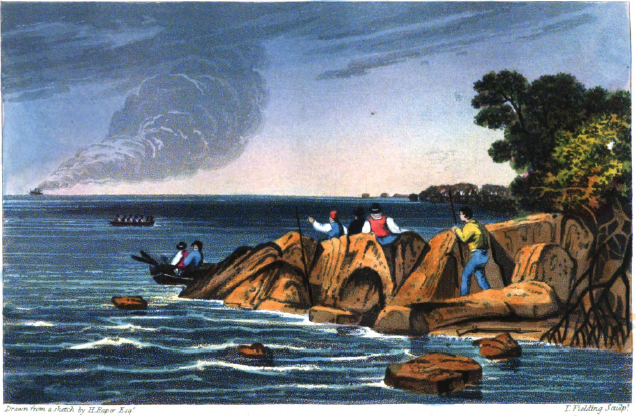

THE WATERFALL, AT HONG CONG.

Published by Langman Hurst, Rees. Orme &. Brewn, London. Oct 1 1817.

[page i]

NARRATIVE OF A JOURNEY

IN THE INTERIOR OF

CHINA,

AND OF

A VOYAGE TO AND FROM THAT COUNTRY,

IN THE YEARS 1816 AND 1817;

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE MOST INTERESTING TRANSACTIONS

OF

LORD AMHERST'S EMBASSY TO THE COURT OF PEKIN,

AND

OBSERVATIONS ON THE COUNTRIES WHICH IT VISITED.

BY CLARKE ABEL, F.L.S.

AND MEMBER OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY,

CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER AND NATURALIST TO THE EMBASSY.

ILLUSTRATED BY MAPS AND OTHER ENGRAVINGS.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, AND BROWN,

PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1818.

[page ii]

Printed by A. Strahan,

Printers-Street, London.

[page iii]

TO THE

RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD AMHERST,

&c. &c. &c.

MY LORD,

THE high situation held by Your Lordship as head of the Embassy of which these pages contain some account, will, in the public mind, point out the propriety of the present Dedication. Permit me to declare that this consideration has less influenced me than the desire of publicly thanking Your Lordship for your sanction and support to my scientific pursuits, and uniform kindness to myself.

I am, My Lord,

With the greatest respect,

Your Lordship's

Obliged and obedient humble Servant,

CLARKE ABEL.

London, July, 1818.

A 2

[page iv]

[page v]

ERRATA.

| Page 12. | line 13. | for Sensations never, read Sensations which I never. |

| 34. | line 4. | for below quite bare, read below they are quite bare. |

| 35. | note, | for See note (B) in Appendix, read See Appendix. |

| 40. | line 15. | for eight or ten, read eighty or a hundred. |

| 50. | line 13. | for coagulated, read coagulable. |

| 50. | note, | for Appendix C, read Appendix. |

| 60. | line 31. | for from a fern which I believe to be the Polypodium trichotomum of Kæmpfer, read from the Polypodium dichotomum of Thunberg. |

| 60. | note, | for Icones Kæmpferi. Banks, read Flora Japonica. Pl. 17. |

| 61. | line 23. | for Polypodium trichotomum, read Polypodium dichotomum. |

| 63. | note, | for See Edict I, in Appendix E, read See Appendix. |

| 68. | note, | for See Appendix F, read See Appendix. |

| 108. | line 3. | for Chow-ta-jin, read Sun-ta-jin. |

| 143. | line 10. | for caprifolia, read caprifolium. |

| 150. | line 7. | for over, read through. |

| 152. | line 8. | for white, read black. |

| 155. | lines 3. & 5. | for Paludina, read Bithynia. |

| 160. | line 18. | for dying, read dyeing. |

| 160. | line 21. | after Chinese, erase and. |

| 167. | line 10. | for lanceolatus, read lanceolata. |

| 181. | line 25. | for smallest, read smallest leaved. |

| 191. | line 24. | for former, read latter. |

| 203. | line 17. | for vegetable, read corn. |

| 233. | line 6. | for accept, read accept it. |

| 244. | lines 9. & 13. | for Augustine, read Franciscan. |

| 254. | line 33. | for suit, read suite. |

| 267. | line 10. | for payed, read paid. |

| 313. | line 27. | for religiosus, read religiosa. |

| 322. | note, | in the measurement of the Orang-Outang, for 9, read 19, as the circumference of its hips. |

In this view might be dwelt upon, and has so illustrated them by the writings of the Missionaries, as almost to preclude the hope of a further elucidation of the same subjects from similar sources of information.

[page] vi

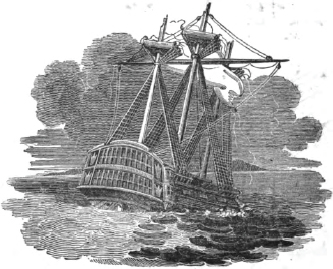

I am in scarcely less difficulty respecting the natural history of the countries which I have visited. Sickness abridged, and shipwreck almost annihilated the materials which would have afforded extensive scientific communication respecting China. My illness, indeed, was comparatively of little importance, except as it prevented my observation of the country; for the exertions of my friends more than compensated the loss of my individual efforts in making collections. But the shipwreck deprived me of all the fruits of those means which the wisdom and liberality of the East India Company placed at my command; and has only left me the duty of stating, in justice to others, what was the nature of those means, and something of the results to which they led.

My appointment to the Embassy was at first simply medical; but through the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks to the East India Company, I was permitted to take upon me the office of Naturalist, and received an ample outfit of all the apparatus for scientific research. To give greater effect to my exertions in collecting and preserving the vegetable productions of the countries to be visited by the Embassy, a botanic gardener, from the Royal gardens at Kew, taking out with him a plant cabin, for the preservation of living specimens, was placed under my directions; and to assist generally in my pursuits my brother-in-law, Mr. Poole, was allowed to attend me. With such facilities, it would have been strange, even in countries often trod by scientific men, if I had not gleaned some new and important facts. But in China, scarcely touched by the foot of the naturalist, nothing short of a rich harvest could have been received as a token of my due exertions. The proofs of what these were, of their efficiency or abortiveness, are buried in the straights of Gaspar. But it is incumbent on me to bear testimony to the exertions of Mr. Hooper, the Botanic Gardener, whose industry was equally unremitting and availing. His more peculiar department having been to collect and preserve seeds, he placed, on our leaving China, three hundred packages,

[page] vii

in my keeping, many of which were taken from plants of undescribed genera, and by far the greater number from unknown species. They formed part of the shipwrecked collection.*

From the kindness of Sir George Staunton, to whom I gave a small collection of China plants, and of Captain Basil Hall, to whom I gave a small collection of China rocks at Canton, I have derived all the specimens which have enabled me to give the slight geological and botanical notices of China contained in this work. To the latter gentleman, and to his friend, Mr. Clifford, I am also under other obligations of an important kind; and in naming them, have to mention the loss of collections equalling my own in value. In taking leave of the Embassy on its disembarkation in the Gulf of Pe-tche-le, they took charge of a case of bottles with spirit, for the purpose of preserving any interesting marine animal production which might fall in their way; and the necessary means for the preservation of plants. On rejoining the Embassy five months afterwards, they presented me with a collection of Zoophytes and an extensive collection of plants from the Lew-chew Islands. These also perished with the Alceste, but do not complete my catalogue of losses. A fine collection of madrepores made by Capt. Maxwell may be added to them, and will still leave it unfinished. Whilst the Alceste and Lyra explored the Corean coast and the Lew-chew islands, the other ships of the Embassy visited the coast of Tartary. Lieut. Maughn, of the East India Company's service, went with them, and having taken directions as to the mode of preserving dried specimens of plants, surprised me on my arrival at Canton with an extensive geological and botanical collection from the coast of Tartary. These, encreased by a collection which had been made from the same part of the world, for Mr. Livingston, one of the surgeons to the British factory at Canton, and which I received from the kindness of that gentle-

* After leaving the wreck of the Alceste, I had the mortification of hearing that the cases containing these seeds had been brought upon deck and emptied of their contents by one of the seamen, to make room for some of the linen of one of the gentlemen of the Embassy.

[page] viii

man, were also placed in my possession, and shared the fate of my other specimens. But I should fatigue the patience of my readers without doing justice to my own feelings, if I attempted to state all that I owe to the kindness and exertions of my friends and all that they have left me to regret.

After these declarations respecting the loss of materials which would have given value and interest to these pages, what, it may fairly be asked, have I remaining of importance to the public? In looking over my observations on the countries that I had visited, I was of opinion that they contained something to interest, and something to inform. It is not for me to judge how far I may have correctly estimated the value of my matter; but I trust that the exclamation of the Poet,

"—— ibi omnis,

Effusus labor."

will not entirely apply to my pages. I have endeavoured to describe things as I saw them; and when subjects arose incidentally from my narrative, have tried to give them an extrinsic interest by noticing the opinions of others and comparing them with my own. In doing so, I have respected the freedom of my own mind, and have never hesitated to express my thoughts, even when they differed from high authority. I trust that my language has, on these occasions, expressed the deference of my feeling. If, however, it should not always be found exactly suited to my purpose, I beg that my readers will charitably attribute it to my little experience in the niceties of speech. Indeed, it is in what concerns the style of this work that I am especially anxious to bespeak their indulgence. Little practised in composition, I have been desirous to give my own thoughts in my own words, and in doing so have not, I fear, benefited the language of these pages, and have delayed them longer than the merit of their contents may seem to have deserved. In what regards my facts and conclusions I cannot feel much apprehension: the first are, to the best of my judgment, strictly stated, and

[page] ix

the last were drawn because they seemed to follow the premises, and if they be not adopted will only have the fate of others better than themselves.

In making acknowledgments it seems almost superfluous to state that I am under the deepest obligations to Sir Joseph Banks, whose support to my scientific views was the natural consequence of their being laudable and useful. In leaving England I carried with me his instructions respecting the objects to be kept most closely in view during my absence, and since my return have derived from the freest access to his library and herbarium all possible facilities in constructing this work.

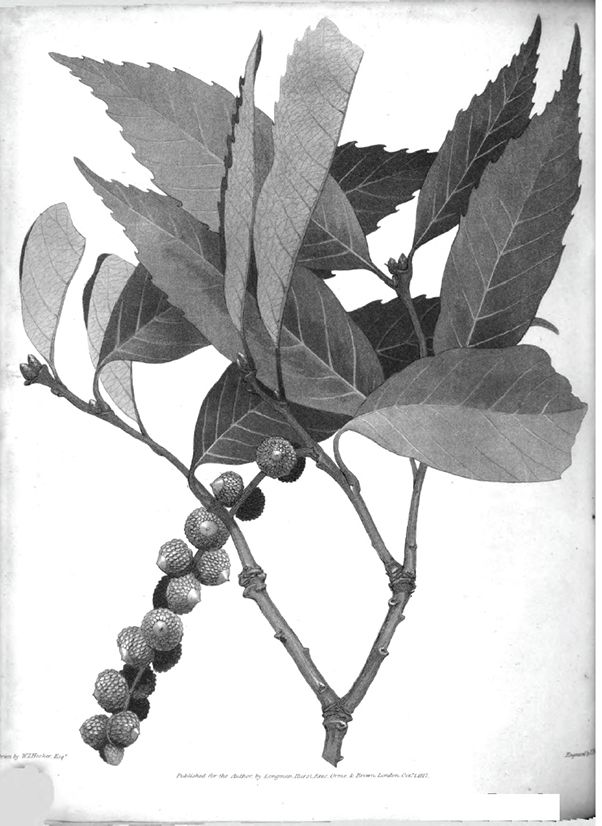

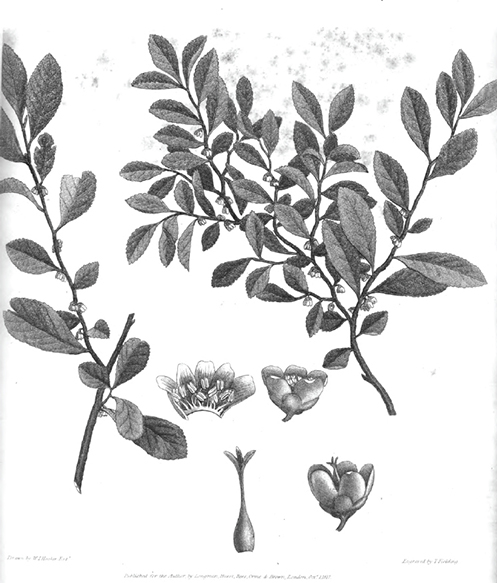

Of the assistance of Robert Brown, Esq. the following pages bear sufficient evidence. His description of a new genus, which, in friendly partiality, he has named Abelia, and of two new species of plants, the one leading to the establishment of a new natural order, and the other fixing the place in the natural method of a genus hitherto of doubtful affinity, gives unequivocal value to my Appendix.

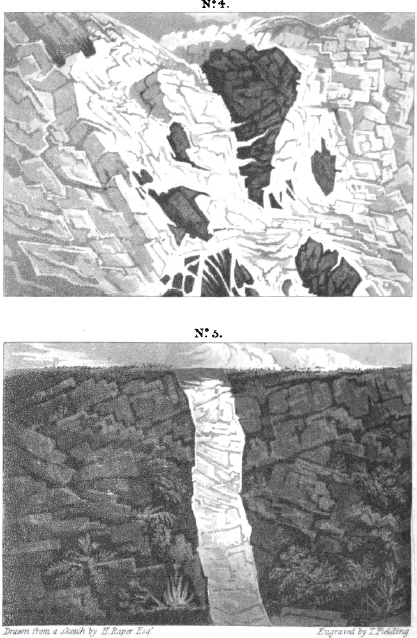

To Mr. Morrison's journal I owe in a great measure the short account of the progress of the Embassy during the period of my illness, and some interesting notes respecting transactions from which I was absent. Some of these notes would have been incorporated with the text had I possessed the journal at an earlier period. To Mr. Cooke's journal I have been also much indebted, and to the same gentleman I owe two drawings which illustrate the book. The drawings of the Quercus Chinensis and Eurya Chinensis are from the tried pencil of my friend W. Hooker, Esq. To Mr. H. Raper, an officer of the Alceste, I am indebted for all the geological views, except two, of the Cape of Good Hope, taken on the spot, and possessing not their least value in their minute accuracy. The plate of the temple of Quong-ying is from a sketch which I obtained from the kindness of Sir George Staunton. The other drawings, not bearing the names of professed artists, I am answerable for.

a

[page] x

For that part of the "Chart showing the track of the Alceste," which gives the line of the Corean coast and the Corean archipelago, I have to thank the Rev. Mr. Taylor, chaplain of the Alceste. The more general map of China, and the map of the route of the Embassy on the Yang-tse-kiang, are reduced from the great map of the Jesuits. My object in giving the former has been to convey to the reader some notion of that very peculiar character of the country, which arises from its universal intersection by navigable rivers and canals, as well as to show the whole route of the Embassy. Its accuracy of course depends on that of the Jesuits, which we had no opportunity of verifying, but had no occasion to suspect. It so far, however, differs from the map of the Missionaries in containing the names of a greater number of places in the line of our route than the original, and in having the nature of the banks of the rivers passed over by the Embassy marked upon it, when this could be done without producing confusion by crowding the letter-press. The same observations apply to the map of the Yang-tse-kiang and Po-yang lake.

The meteorological tables contained in the Appendix, although very imperfect, will be thought perhaps to have merited insertion as adding to the very few facts that we already possess regarding the atmospherical phenomena of a part of the world so little known. I have scarcely as much to say for the Itinerary of our route. It is of some consequence in reference to the maps, and in containing disstances extracted from a Chinese Itinerary: an excuse for its insertion may be found in the small space which it occupies.

In conclusion, I must not forget to point out the fidelity with which the engraver, Mr. Fielding, has executed his department of the work, or to acknowledge the interest he took in the progress of it, and his anxiety that the accuracy of his pencil should correspond with the nicety of my own wishes in subjects not so frequently under the eye of an artist.

[page xi]

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

DEPARTURE of the Embassy from Portsmouth.—Arrival off Madeira.—Town of Funchal.—Mountain Torrent.—Priests.—Flying-fish.—Remarks on its habits.—Pass the line.—Cape Frio.—South America.—Harbour of Rio di Janeiro.—St. Sebastian.—Fish and vegetable market.—Visit to the Braganza shore.—Sugar Loaf Mountain.—Musical instrument of the negro slaves.—Importation of slaves.—Remarks on the slave trade.—Second visit to the Sugar Loaf Mountain.—Scenery of the mountain.—Visit to the Botanic Garden.—Cultivation of the Tea-plant.—Its preparation.—Plants cultivated in the Botanic Garden.—Ipecacuanha plants of the Brazils and of New Spain.—Fire-flies.—Islands in the harbour.—Their geological structure.—Fruits.—General remarks. Page 1

CHAPTER II.

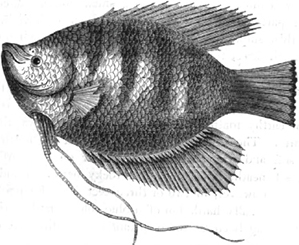

Departure of the Embassy from Rio di Janeiro.—Arrival off the Cape of Good Hope.—In the Straights of Sunda.—Shark.—Sucking Fish.—Arrival at Sirang.—Volcanic Mountain.—Plassur Pittee.—Javanese instruments.—Dexterity of the natives in climbing the Cocoa-nut trees.—Gunong Karang.—Rice fields.—Scenery of Plassur Pittee.—Hospitality of the natives.—Their huts.—Visit to the Crater of Gunong-Karang.—Precipitous ascent.—Interesting plants.—Benevolence of the Javanese.—Visit to Pandigalang, famed for the manufacture of bracelets.—Javanese arms.—Kriss.—Gold and silver ornaments worn by Javanese women.—Native Sulphur.—The Goramy, a fish common in rivers.—Return to Sirang.—Mineral springs.—Bantam.—Ceremony of circumcision.—Sultan of Bantam.—His death.—Great bats of Java.—Of the large Snake of Java.—Its habits.—Destroys a man.—Swallows a Goat.—Dissection of the Snake.—Power of Snakes.—Geckoo Lizard of Java.—Species of.—Characters of.—Habits of.—Departure from Sirang. 24

a 2

[page] xii

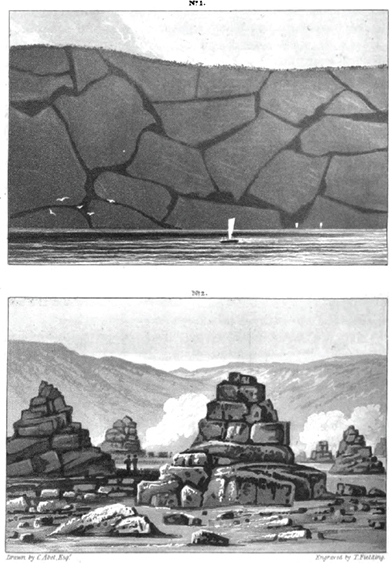

CHAPTER III.

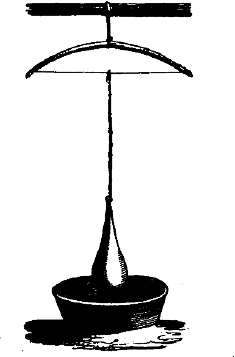

Departure of the Embassy from Batavia Roads.—Typhoons.—Lemma Islands.—Physalia.—Hong Kong.—Plants found there.—Its high conical mountains.—Waterfall.—Geological facts.—Scenery of Hong Kong.—Departure from Hong Kong.— Libellulæ.—South-west monsoon.—Straits of Formosa.—Mee-a-tau Islands.—Meteorological observations.—Experiments on the temperature of the water of the Yellow Sea.—Ambassador visited by two Mandarins.—In what manner received.—Visit of Chang and Yin to the Ambassador.—Description of their persons, manners, and dress.—A junk with supplies.—Presents for the Emperor trans-shipped.—Disembarkation of the Embassy.—Embassy announced to the Legate.—Arrival at Ta-koo on the banks of the Pei-ho.—The Legate visits the Ambassador.—Chinese crowd.—Present from the Legate to the Ambassador.—Departure from Takoo.—Banks of the Pei-ho.—Observations on its inhabitants.—Stacks of salt.—Approach to Tien-sing.—Appearance of the people.—Arrival at Tien-sing.—Description of the city.—Hall of audience described.—The screen.—Mandarins.—Performance of the ceremony discussed.—In what manner performed.—Chinese feast.—Play.—Presents to the gentlemen of the Embassy.—Chinese salutation.—Ice.—Plants of Tien-sing.—Chinese houses.—Villages.—Visit to a Chinese Colonel.—Chinese encampment.—Soldiers.—Arrival at Tung-chow. Page 58

CHAPTER IV.

Tung-chow.—Ho, brother-in-law to the Emperor.—Muh, president of the Le-poo.—Ambassador and suite visit the Commissioners.—Chinese carts.—Roads.—Interview at Tung-chow.—Interior of the city, its walls, gates.—Note from the Ambassador to the Duke.—The Duke visits the Ambassador.—Preparation to leave Tung-chow.—Description of Chinese carts and horses.—Litters for the sick.—Journey to Yuen-min-yuen.—Bridge.—Road to Pekin.—Halting place.—Refreshment.—Distress of the sick.—Suburbs of Pekin.—Yuen-min-yuen.—Scenery.—Nelumbo.—Ambassador's carriage stopped by Mandarins.—Soo-tagin.—Quang.—Ambassador urged to enter the Imperial Palace.—Enters.—Description of the apartments.—Ambassador urged to enter the Imperial presence.—Refuses.—Is insulted.—Mandarins' solicitations.—Brutality.—Ambassador quits the Palace.—Reaches the quarters prepared for the Embassy.—Visited by the Emperor's Physician.—Haiteen.—Breakfast.—Prepares to return to Tung-chow.—Message from the Governor of Pekin.—Humane conduct of a Chinese.—Application on behalf of the sick.—Departure from Yuen-min-yuen.—Pekin.—Its walls. — Arrival of the Embassy at Tung-chow.—Joy expressed by the boatmen at our return.—One of the Ambassador's servants nearly killed.—Emperor deceived by his ministers.—Arrival of Soo and Quang.—Presents from the Emperor

[page] xiii

to the Prince Regent.—Selection of presents for the Emperor.—Mandarins disgraced.—Remarks on Tung-chow and its environs.—Cheating propensity of the Chinese.—European Coins.—Tchen.—Fur shops.—Sables.—Druggists' shops.—Public houses.—Sam-tchoo.—Beggars.—Observations on mendicity.—Timber sellers.—Their houses.—Plants.—Nelumbium.—Petsai.—Fruits.—Xing-ma, or Cordage plant.—Nature of the soil.—Insects.—Sickness at Tung-chow.—Noxious qualities of the water.—Death of one of the band.—Observations on the cause of disease at Tung-chow.—Water of the Pei-ho. Page 92

CHAPTER V.

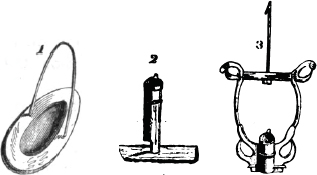

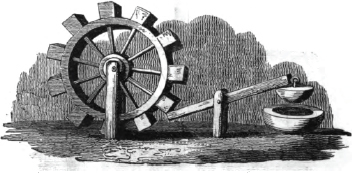

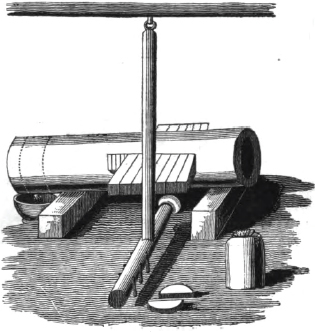

Embassy leaves Tung-chow.—Plants.—Peasants.—Arrival at Tien-sing.—Articles of ingenuity.—The Yu, its different varieties, its manufacture.—Agate.—Puddingstone.—Chinese barbers.—Shampooing.—Chinese razors.—Barbers' instruments.—Departure from Tien-sing.—Euho, or Imperial River.—Appearance of the country.—Corn and oil mills.—Oil of Sesamum.—Mode of expressing the oil.—Blacksmith's shop.—English pen-knives.—Razors.—Scissars.—Exactions of the soldiers.—Illness of the author.—Face of the country.—Quit the province of Pe-tche-le.—Plants.—Character of Chang.—Character of Yin.—The judge of Pe-tche-le.—Blind musicians.—Sang-yuen.—Thuja Orientalis.—Willows.—Pagoda of Lin-tsing.—Mahomedan mosques.—Cha-ho.—Tang-chang-foo.—Fan-shang-meaou.—Wan-ho.—Lake.—Embankments of the Canal.—Province of Shantong.—Province of Kiang-nan.—Face of the country changes.—Chung-tswe-tsee, or full harvest moon.—Sacrifice of the boatmen.—Yellow River.—Ambassador and suite land.—Pass a flood-gate.—Pass Tsing-keang-foo.—Locks.—Population.—City of Hival-gan-foo.—Kaou-yen-chow. Temple.—Impressment of trackers.—Their confinement.—Pagoda of Kao-ming-tse.—Change boats.—Woo-yuen.—Picturesque landscape.—Qua-tchow.—Imperial Canal.—Observations on Imperial Canal.—Plants.—Rice fields.—Snakes.—Shells.

130

CHAPTER VI.

Embassy enters the Yang-tse-keang.—Quan-yin-mun.—City of Nankin.—Porcelain Pagoda.—Hot baths.—Cotton.—Plants.—Walls of Nankin.—Leave Nankin.—City of Woo-hoo-shien.—Tallow tree.—Geological appearance.—Arrival at Ta-tung.—Ta-few.—Cotton mill.—Tea-plant, first met with.—Oaks.—Remarks on them.—Ginger.—Kwa-yuen-chin.—Death of William Millidge.—Conical Rook.—Province of Kiang-si.—Enter the Poyang Lake.—Ta-koo-shan, or Orphan Rock.—Ta-kootang.—Plants.—Arrival at Nan-kang-foo.—Archways.—Romantic Scenery.—Temple of Pih-luh-tung-shoo-yuen.—Ferns used as tea.—Ferns collected.—Embassy quit the

[page] xiv

Poyang Lake.—Arrival at Nan-chang-foo.—General observations on the Yang-tse-keang.—Cultivation.—Scenery.—Oak, tallow and camphor-trees.—Pine.—Geolo gical facts.—Meteorological observations. Page 156

CHAPTER VII.

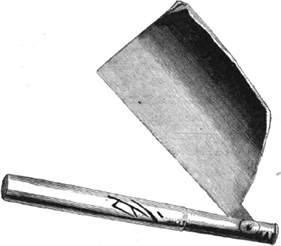

Nan-chang-foo.—Porcelain Vases.—Porcelain shops.—Fire in the suburbs.—Embassy leaves Nan-chang-foo.—Beautiful plants.—Camellia Sasanqua.—Camellia oleifera, or oil plant of the Chinese.—Expression of oil.—Oil press.—Tallow-tree.—Process of extracting the tallow.—Candles.—Camphor-tree.—Mode of obtaining the camphor.—Species of Ficus.—Plantations of Camellia.—Cross the She-pa-tan, or eighteen cataracts.—Rocks.—Soil.—Plants.—Arrival at the city of Nan-gan-foo.—Rocks in the neighbourhood of the city.—Ground-nut.—Cross the Mei-ling Mountain.—Arched gateway.—Wild scenery of the mountain.—Lime-kilns.—Valley of rocks.—Village of Choong-chun.—General observations on the military of China.—Triumphal arches.—Chinese cities.—Du Halde's description of.—Chinese boats.—Re-embark.—Shallowness of the river.—Mountains.—Geological formation.—Brickkilns.—Timber-rafts.—Marbled rock.—Vegetation.—Coal-pits.—Sulphate of iron. Chaou-chou-fou.—Bridge of boats.—Unsuccessful attempt to enter the city.—Canton linguist.—Change of boats.—Temple in the fissure of a rock.—Lord Macartney's description.—Nature of the rock.—Chinese Bonzes.—Rocky pass.—Plants.—Plantations of sugar cane.—Sugar mills.—Buffaloes.—Terrace cultivation.—General cultivation.—Population of China.—Approach to Canton.—Groves of orange trees, of bananas, and of rose apples.—Arrival at Canton. 173

CHAPTER VIII.

Canton.—Cruise of the Alceste and Lyra during the absence of the Embassy.—Viceroy of Canton.—Chinese edict.—Emperor's letter to the Prince Regent.—Ceremony of its delivery.—Viceroy's arrogance humbled.—Conference between the Ambassador and Viceroy.—Streets of Canton.—Shops of.—Fans.—Snuff bottles of rock crystal.—Adamantine spar, or Corundum.—Porcelain shops.—Minerals employed in colouring porcelain.—Glass shops.—Drug shops.—Camphor.—Opium.—Tobacco.—Mercury.—Chinese medical practitioner.—The Moxa.—Artemisia.—Vaccination.—Gypsum.—Streets of Canton.—Unsuccessful attempt to enter them.—Nursery Gardens of Fa-tee.—Plants.—Tea-plant.—Manufacture of.—Its cultivation.—In what latitudes it flourishes.—Where cultivated.—Plantations of the Green Tea.—Observations on the Tea-plant.—Temple.—Religious ceremony.—Chinese deities.—Bonzes.—Library of religious books.—Printing-office.—Moveable types.—Embassy leave Canton.—Salute from the batteries.—Food of the Chinese.—Character of the

[page] xv

Chinese.—Their proneness to falsify.—Middling class of Chinese.—Penury of the lower orders.—The peasantry.—Infanticide.—Exposure of children.—The Alceste anchors off Macao.—Portuguese Governor.—Macao.—Nepenthes distillatoria.—Geological appearance. Page 207

CHAPTER IX.

Embassy arrives at Manilla.—Festival.—Inhabitants' dress.—Ambassador visits the Governor.—Mulatto women.—Cigars.—Their manfacture.—Bamboo dwellings.—Execution of malefactors.—Mode of strangling.—Embassy dines with the Governor.—Olla Podrida.—Andalusian.—Gallician.—Excursions to Los Bagnos.—River Passig.—Its scenery.—Canoes of the natives.—Convent of Benangonan.—Laguna de Baie.—Method of catching fish.—Franciscan Convent.—Superior of the Convent.—Epidemic disease.—Procession of Indians.—Los Bagnos.—Native village.—Small convent inhabited by a native priest.—Description of convent and its inhabitants.—Hot springs.—Temperature.—Vapour baths.—Hot stream.—Sonnerat's statement.—Woods.—Trees.—Plants.—Cordage plant.—The nippis.—Arrival of the Ambassador at Los Bagnos.—Return to Manilla.—Alceste leaves Manilla Bay.—Is wrecked.—Ambassador and suite land on Pulo Leat.—Ground cleared.—Scenery.—Want of water.—Excessive thirst of the party.—State of the Alceste.—Cask of water staved.—Ambassador and suite leave Pulo Leat for Batavia in two boats.—Sunken rocks.—Point of Banca.—Short allowance.—Fall of rain.—Dead calm.—Breeze.—Approach land.—Exhaustion of the men.—Anchor near Krawang Point.—Fresh water discovered.—The Krawang river.—Princess Charlotte transport.—Arrival in Batavia roads.—Ternate and Princess Charlotte dispatched to Pulo Leat.—Arrival at Batavia.—At the Dutch Governor's.—Transaction at Pulo Leat after the departure of the Ambassador and suite.—Heavy fall of rain.—Musquitoes.—Captain Maxwell addresses his men.—Malay prows attack the wreck.—Malay boats.—The party chased by Malays.—Two of the Alceste's boats appear.—Malays make for the wreck.—Plunder it.—Picquets stationed at the landing place.—Party retires to rest.—Encampment alarmed by a large monkey.—Scolopendras.—Scorpions.—Alceste fired by the Malays.—Garrison again alarmed by a monkey.—A party dispatched to the ship.—Twelve sail of Malay prows appear.—A well dug.—Fortress.—Two canoes laden with plunder.—Malay prow attacked by Alceste's barge.—Commander of the barge kills two Malays.—Barge's grapnell sinks the prow.—Malays fight in the water.—Three dragged on board the barge.—Two die.—Third made prisoner.—Employed to cut wood.—Makes his escape.—Fourteen Malay prows appear off Pulo Leat.—Captain Maxwell gives orders to prepare for a voyage to Batavia.—Captain visited by the Rajah.—He musters his men.—Malay prows increase to forty-five.—A sail descried in the distance.—Ternate arrives.—The shipwrecked band embarks for Batavia. 237

[page] xvi

CHAPTER X.

Java.—Description of Batavia.—Weltervreden.—Barracks.—Fruit.—Mangostan. Bazaar.—Trees.—Sugar-tree.—Javanese ink.—Plants.—Chinese burial ground. Nelumbium.—Lotus.—Artisans.—Dutch colonists.—Balls.—Dress of the colonists.—Buitenzorg.—Its scenery.—Climate.—Causes of disease.—Mode of cure.—Departure from Java.—Fire on board the Caesar.—Arrival in Simon's Bay. Page 274

CHAPTER XI.

Cape of Good Hope.—Geological excursion at.—Magnificent scenery.—The Kloof.—Basaltic vein.—Strata of sandstone.—Rocks grotesquely grouped.—Vein of small-grained granite.—Green point.—Vertical strata of schistus.—Mixture of granite and schistus.—Granite resting on schistus.—Intimate union of granite and schistus.—Beds of schistus.—Schistus imbedded in granite.—Ascent up Table Mountain.—Mixture of schistus and granite.—Veins of granite in schistus.—Schistus imbedded in granite.—Varied character of granite veins.—Sandstone formation.—Native iron.—Oxyde of iron.—Simon's Town.—Junction of granite and sandstone.—Order of appearances.—Description of the schistus.—Explanation of appearances.—Mr. Playfair and Captain Hall's opinions.—Neptunian theory.—Phænomena inexplicable by.—Huttonian theory.—Phænomena explicable by.—Wernerian theory.—Appearances explained by.—General conclusions.—Constantia.—Huyt's Bay.—Stalactite at.—Cause of.—Simon's Town.—Incrustations on vegetables.—Opinions of Vancouver.—Flinders and Péron respecting experiments on.—Results.—Albatross. 285

CHAPTER XII.

St. Helena.—Scenery of.—Plantation house.—Plants of.—Climate of.—Geological facts.—Beds of lava.—Friar's ridge.—Buonaparte.—Visit to.—Conduct of.—Description of.—His health.—Embassy.—Departure from St. Helena.—Island of Ascension.—Author's visit to.—-Geology of.—Euphorbia.—Turtle.—Departure from. — Orang Outang.—Description of.—Hair.—Skin.—Head.—Chest.—Hands.—Posture.—Habits in Java.—On board ship.—Sagacity and disposition.—Examples of.—Intimacy with the boatswain.—Monkey's anger.—Examples of.—Arrival in England. 313

APPENDIX 331

[page break]

[page break]

[page 1]

EMBASSY TO CHINA.

CHAPTER I.

DEPARTURE FROM PORTSMOUTH.

AT three o'clock of the afternoon of February 8th, 1816, I embarked with His Excellency Lord Amherst, on board H. M. S. Alceste, then lying at Spithead. Getting under weigh at eight o'clock the following morning, in company with H. M. S. Lyra, Capt. B. Hall, and General Hewitt, Capt. Campbell, we steered with a fine breeze through the Needles. In passing the shores of the Isle of Wight, my imagination dwelt painfully on its white cliffs and verdant slopes, which but three days before I had visited with friends who gave the best value to my existence, and from whom I was separating, perhaps for ever. But the painful feelings excited by such reflections, too intense, indeed, for long continuance, were quickly destroyed by my share of the bodily suffering which attacked, in succession, the greater number of those, who then, for the first time, felt the motion of a ship at sea. Scarcely had we cleared the western extremity of the island, when an intolerable giddiness, languor, and sickness, drove me to my cot, and had but slightly mitigated, when the mountains of Madeira were descried from the ship.

Early in the morning of the 18th February, going upon deck, I saw this interesting island bearing S. S. W., distant about six leagues.

B

[page] 2

A thick white cloud covered its mountains, which gradually dissipating as we advanced, disclosed their snowy summits beautifully contrasting with the dark foliage of their declivities. The squadron hove to about ten o'clock in the forenoon, off the town of Funchal, at the distance of two or three leagues from the land.

Having prepared every thing for collecting objects of natural history, I waited impatiently for the appearance of a boat, to carry me to the fulfilment of my anticipations. Examining with my glass the aspect of the rugged shores, I exulted in the geological interest of their appearance, and collected, in imagination, plants which, from number and rarity, would give a long and delightful employment. What then was my disappointment, when I was informed by His Excellency, that he wished no one to leave the ship, lest any chance of delay should arise to the sailing of the Alceste, as soon as she had obtained the necessary supplies. As Lord Amherst denied himself, for public reasons, the pleasure which he much desired, of visiting the island, no one of his suite had a shadow of right to remonstrate, and I prepared to suffer my disappointment with all possible patience. After the lapse, however, of two or three hours, Capt. Campbell, of the General Hewitt, came on board, and offered to take me on shore; and, being almost immediately to return, I readily accompanied him.

On approaching the beach, where I had hoped to find some specimens of sea-weed, I found the depth of water up to the shore so great, that a vessel might almost anchor with her bowsprit over the land, and consequently, that no marine production was to be met with. The beach is made up of large rounded fragments of lava, generally of a vesicular structure, very ponderous, and of a bluish colour. Landing to the westward of the town, I found a mountain torrent, having its bed sides formed of huge masses of volcanic matter, as far as the eye could follow its romantic windings. I entered its bed in search of plants, but found very few, as the apprehension of losing my chance of returning to the ship prevented my looking very narrowly. The Fumaria Parviflora, which was growing in great

[page] 3

abundance in all the crevices of the rocks, and a few geraniums, ferns, and mosses, composed my collection.

Not finding the boat in readiness on my return to the beach, I walked into the town, which I entered under an archway that led to a long narrow street very well paved with round pebbles, and perfectly clean, and which was intersected by others of a similar character. The houses are lofty, and completely overshadow the narrow streets, forming an effectual screen against the beams of a hot sun. The softer sex, for here they cannot be called the fair sex, were enjoying the air on virandas which projected from the first floor of the better-looking houses, and were enabled by the narrowness of the streets to converse freely with their opposite neighbours. The young ladies of Madeira, although dark brunettes, possess many charms. Their hair, and arching eye-brows, are of a jet black, and their eyes sparkle under lashes of the same colour; their face is oval and expressive, and handsome rather than beautiful.

The streets were filled with foot passengers, of whom no inconsiderable number were priests, in long loose robes, and without hats. They had evidently fared on the fat of the land; and many of them exhibited in their countenances and deportment, a full share of self-satisfaction and self-importance. But the faces of others seemed to be lightened with a paternal feeling, and physiognomists might have traced in them characters of mildness, benignity, and religion. Neither did they all receive the same marks of respect from the passing populace. Sometimes the hat was simply raised, and the body bowed, without any regard being directed to the object of this salute, which was begun and ended at the instant of meeting. In other cases, an eagerness was shown to catch the observation of the Father, long before he approached, while a deprecating and beseeching manner appeared to implore the blessing of a superior being. It was agreeable to the harmony of my own sentiments, that these last attentions were paid to those alone, whose exterior almost incited me to a similar display of respectful feeling.

B 2

[page] 4

On quitting the town, I was disposed to conclude, that it had been much improved since it was visited by its last describers; but as it was Sunday when I was there, and all classes were enjoying the leisure of the day in their best apparel, and as first impressions are frequently erroneous, I shall confine myself to the remark, that what I saw did not correspond with what I had read.

When I reached the Alceste, I found that I might have remained on shore several hours, as some circumstances had occurred, which prevented her immediate sailing; and she did not leave Funchal Roads till the evening, when we got under weigh with a fine breeze.

As we proceeded on our voyage towards the Line, the tedium of our situation was in some measure relieved, by the amusement we derived from observing the habits of the flying-fish, which continually surrounded us. This animal, equally interesting in its structure, and in the circumstances of its persecuted life, has been so often the theme of the traveller's description, that its very mention comes with the heaviness of a twice-told tale. Yet, although its descriptions are numerous, much is still wanting to the completion of its natural history; and it is a subject of regret with naturalists, that its species met with by voyagers, are not ascertainable. For these reasons, and because "nature is an inexhaustible source of investigation," I shall state the few observations which I made on a specimen that was brought me on the morning of the 27th February, when in lat. 10° 38' N., and 25° 47' W. long.; and I do this the more readily, as its characters did not entirely accord with the description of any other species.

The colour of its back was a deep blue, which passed on its sides into a yellowish green, terminating in a silvery white, which, near its tail, had a pinkish hue. Several small patches of white reached from above its eye, to the pectoral fin. Its fins were six in number; two pectoral, two ventral, one caudal, and one dorsal. The pectoral fin consisted of fourteen rays, and was five inches in its greatest length, and as much in its greatest width. The two undermost rays, when the wing was expanded, were very short, and scarcely distin-

[page break]

EXOCOETUS SPLENDENS.

Published by Longman Hurst Rees Orme & Brown londen Oct. 11817

[page break]

[page] 5

guishable from those next them, and the uppermost ray was the longest. Each ventral fin consisted of six rays, and was situated immediately behind the insertion of the pectoral fin. The dorsal fin, the rays of which were so indistinct that I cannot venture to state their number, had its origin about two-thirds down the back. The caudal fin was an inch long, and terminated at the setting on of the tail.

From the above description, it will appear that my specimen resembled the Exocætus Volitans in the position of the ventral fins, but differed from it in colour, which in the latter is brownish red on the back. It agreed with Exocœtus Exiliens and Mesogaster, in its general colour, but differed from them in the position of its ventral fins. It was distinguished from them all by the position of its dorsal fins. Should these differences be considered sufficient to establish it as a new species, I would propose to call it Exocœtus* Splendens, from the brilliancy of its colours.

The species which I have just described is furnished with as ample means of supporting itself in air as any of its congeners. Its air-bladder reaches from the pharyngeal bones along the spine to the extremity of its body, occupying eight-tenths of its whole length. The widest part of the air-bladder is situated immediately in front of the pectoral fins, and it tapers gradually towards the tail. It is equal in bulk to about four-tenths of the whole fish.

A particular purpose seems to be answered by the greater dimension of the air-bladder near the head, namely, the compensation of the great gravity of the animal at this part in consequence of its breadth. This compensation is necessary to the support of the animal's body in the air in a favourable position for flight. The situation of the pectoral fins before the centre of gravity in this, as in other flying-fish, also tends to elevate the head, as remarked by Lacépède.†

* If the white spots on its head be peculiar, Exocœtus Maculatus would be a better name.

† Histoire Naturelle des Poissons, vol. v. p. 406. Lacépède has made the situation of the dorsal fin opposite to the anal fin an essential character of the genus Exocœtus. Is it a universal character, or is the situation of the dorsal fin in my specimen a mere exception to a general law?

[page] 6

It has been stated by a naturalist* of the highest eminence, that the pectoral fins of the flying-fish serve only as a parachute, and by another† that "the animal beats the air during the leap, that is, it alternately extends and closes its pectoral fins." With this last observation my own experience perfectly agrees. I have repeatedly seen the motion of the fins during its flight, and as flight is only "swimming in air," it appears natural that these organs should be used in the same manner in both elements. The flying-fish is also much nearer in conformation to the bat, which supports itself in the air by repeated percussion, than to the flying squirrel, and other animals, whose structure only enables them to fall slowly. I may also remark, that when the fin of the flying-fish expands, its rays do not open in the same line, but describing a curve strike the air with repeated impulses.

I found it impossible to satisfy my mind with any probable conjecture respecting the greatest space through which these fish can support themselves in air, but I have seen them fly without once touching the water for fifty seconds, and my eye could not follow them till they fell. I have little doubt that they take to the air, as well for pleasure as to escape their enemies, since they were often seen rising about the ship in all directions, when no foe was visibly near, and when they had not been disturbed by the ship's motion through the water. Indeed I have been disposed to think myself unfortunate in not witnessing, during the whole voyage, a single flying-fish taken by a frigate-bird, or dorado; and I therefore venture to hope that these poor animals are not so persecuted a race as travellers have been led to imagine.

It is impossible to reflect on the habits of the flying-fish without considering its power of respiring in air. In treating of the respir-

* Cuvier, Règne Animal, tom. ii. p. 188.

† Humboldt, Personal Narrative, vol. ii. p. 14.

[page] 7

ation of fishes, the possibility of their air-bladder acting subsidiarily to the branchiæ, has not passed unnoticed by authors; but I am not aware that this organ in the flying-fish has been pointed out as likely to assist the respiration of that animal out of the water. And yet I had once flattered myself with the belief that I had discovered its communication with the mouth under such circumstances of organisation as precluded any doubt of its aiding the function of aerial respiration. But I had only one opportunity of dissecting the animal when recently taken, and I dare not trust to a single observation. I would recommend however those, whose opportunities are frequent of possessing the flying-fish soon after death, to examine attentively the termination of its air-bladder at the pharyngeal bones. These bones, in all other fish* which I have examined, are two in number, and much apart, their office being to assist deglutition and to shield the blood-vessels which ramify under them on their way to the branchiae. In the flying-fish their number and position is different, allowing the inference that their function is also different. They are in this animal four in number, two large and two small. The two former in close apposition are situated immediately above and behind the anterior orifice of the œsophagus, and are compressed by the latter, which are united to them by a strong elastic membrane. Muscles are attached to the larger bones so as to separate them by their contraction. The anterior termination of the air-bladder is at the posterior portion of the larger bones. The question to be determined is, whether the air-bladder has an orifice at this part, which is opened and closed by the separation and re-union of the pharyngeal bones.

On the evening of the 4th March we passed the line, and on the following morning shortened sail, to pay the usual homage to Neptune, which being accomplished we proceeded on our voyage.

* Since my return I have examined a specimen of the Exocœtus Mesogaster, preserved in spirit, in which the two large bones were united, but there was an orifice between them and the small ones; whether it led into the air-bladder or not I was unable to determine. The same specimen had only eight, instead of ten, rays to its branchiæ.

* B 4

[page] 8

On the 10th, being in 10° 39' S. Lat., and 32° 47' W. Long., the Alceste parted company from the Lyra and General Hewitt, which shaped their course for the Cape, whilst the former steered for the harbour of Rio de Janeiro. On the 20th, we were off Cape Frio, and all those who had never before visited the shores of South America anxiously speculated on the scenes they were about to witness in the New World.

The affections of different minds on first approaching an interesting coast, might form a subject of curious and instructive speculation. When the land indeed appears but as a dark undefined speck in the distant horizon, first reflections cannot widely differ, although their vividness may depend on the sensibility of the individual, and their extensiveness on the number of his associations. But few educated men will approach a country for the first time of their lives, without reverting to the history of its conquest or discovery. On making the coast of the New World, so interesting in the history of man and of the earth, every thought must centre in Columbus. All the circumstances of his situation on the day of his discovery, all the attributes of his mind, and all the heroism of his conduct, array themselves in the imagination. But as the land developes itself, as its larger features become visible, speculation is extinguished in a general glow of undefined but delightful feeling. Never can I forget the pleasing, yet almost awful emotion of my mind, when rising early in the morning I first beheld the shores of South America expanded before me. To describe the scenery by words would be a vain attempt; the pencil of a painter enthusiastic in genius and in feeling, could alone convey to those who have never beheld it an imperfect apprehension of its grandeur.

As objects become still more defined and palpable, various trains of thought arise in different characters. In the commander of a British ship of war, the hope of finding refreshments for his crew, of meeting old friends, of carrying his ship into port in a skilful and gallant style, and of supporting the proud pre-

[page] 9

eminence of his flag, is perhaps on ordinary occasions the leading sentiment of his mind. — In many of his officers, an escape from subordination to the independence of a rove on shore, with all the importance really and in imagination attached to the character of a British naval officer, may be the chief pleasurable expectation. In one or two of them, indeed, very different feelings may arise. Habit sometimes acts so powerfully on a seaman's nature, that all his pleasing associations are of a nautical character, and whatever interrupts their train is to him a positive evil. To such a character the appearance of land, so dear to others, brings with it no pleasing emotion, and is irksome in proportion to his chances of delay. — The professor, or admirer of the pictorial art, dwells on the exterior characters of the scene, collects all the great traits by which a sublime picture is formed, and anticipates the interior beauties of the country of which he contemplates the outline.—The speculator on human character, varied by the modifying influence of climate, religion, and government, takes his own species as the subject of his examination. As the inhabitants of different classes appear, he combines them in an imaginary society, owing its character to his previous conclusions, but which he expects will be found consistent with reality. — Over all these, the naturalist has many advantages both with respect to pleasurable expectation and the chances of its fulfilment. The objects of his studies are infinitely numerous, and each in its simple relations is so completely a centre of observation, that he must always be repaid for the labour of research. On first entering the harbour of Rio Janeiro, he feels unutterable delight. No apprehension of disappointment darkens his prospect. The certainty of meeting Nature in her gayest and most exalted colours, in all her varied and attracted forms, gives him unmixed enjoyment. The brilliant tints of the mountain foliage feed his botanical imagination, whilst the dazzling insects which flutter about the ship tell to him the stores of animated nature. As a geologist, he may almost remain on the deck of the vessel and pro-

* C

[page]10

secute his labours. Immense ridges of primitive mountains, traversed by deep ravines, and rising in succession to the very boundary of his vision, afford him an ample subject of interesting investigation.

Long before the Alceste reached her anchorage, the firing of cannon at regular intervals announced the occurrence of some great public event, and as soon as we communicated with other ships in the harbour, we were informed of the death of the Queen of Portugal. Vessels of all nations that were at this time lying off St. Sebastian, showed their respect to the King of Portugal by crossing their yards, hoisting flags half mast high, and firing guns every five minutes. The Alceste followed their example; and as a farther mark of respect, the British Ambassador determined to appear on shore with some outward badge of mourning, and requested the gentlemen of his suite to do the same.

It was the afternoon before we anchored, and dark before I could gratify my impatience to visit the shore. The city of St. Sebastian has undergone so little alteration since it was described by Mr. Barrow, that any account of it which I could give from my limited means of observation would be superfluous. The darkness of the night prevented my seeing much of the inhabitants, but those who did fall under my passing notice were priests riding in their carriages, friars in procession, and ladies peeping from latticed doors. In company with some friends I hastened to the Caza de Pasto in the Rua D'Alfandaga, the best English hotel in the place, which, although it did not possess the comforts of a similar establishment at home, afforded no ordinary fare, and very civil treatment made us less fastidious respecting our entertainment. Having partaken of a supper at which we were supplied with tolerable claret at three shillings a bottle, we enquired for beds. The house contained no distinct bed-rooms and but few beds; but in a large billiard-room, with the assistance of the billiard-table, chairs, and sofas, our party, though numerous, mustered a sufficient number of separate resting places. The dread of musquitoes, the scourge of Europeans in hot

[page] 11

countries, did not disturb our repose, and we were glad to find in the morning that we had not suffered from their attack.*

I set out at an early hour on my return to the ship, and on my way through the town had an opportunity of taking a hasty glance at the morning employments of some of its inhabitants. Walking by the chief fountain which supplies the city, I was surprised at the great number of slaves who were waiting with vessels to receive in succession a measured quantity of water, and I witnessed the same scene at whatever hour in the day I passed this spot. St. Sebastian is badly supplied with this article, although numerous springs rise every where in its neighourhood within the distance of one or two miles. But the Portuguese in this country require some powerful and present necessity to rouse them to any great exertion, and it is less a matter of wonder that they suffer this inconvenience to exist, than that they ever should have attempted and completed so extensive a work as the aqueduct which supplies the city.

In passing the fish and vegetable market at the southern extremity of the town, every sense I possessed became disagreeably impressed. My hearing, by the jargon of the different languages used by the slaves who were bartering for their masters, and by the old women who were endeavouring to obtain the highest price for their articles of sale. My sense of sight and of smell, by a horrible combination of every sort of filth, which sent forth the most sickening effluvia that ever exhaled from the corruption of a charnel-house. The very air tasted of putridity, and my clothes felt unctuous to the touch from accidental contamination. Some of my companions who were old travellers felt disposed to joke at my squeamishness, and having bought a large quantity of fruit and fish, hired a canoe which carried us and our steaming cargo on board.

* A drought had prevailed at Rio for some weeks previous to our visit, which is always unfavourable to the propagation of these formidable insects. I have found that rubbing the skin with camphorated oil is the best protection against their attack.

C 2

[page] 12

On reaching the ship, I prepared every thing for making collections of plants, and set off in company with some friends on an excursion to the Braganza shore.* We landed at the foot of a small fort, which was in a state of as complete disservice as it is possible to imagine. The guns, from their rust and the rottenness of their carriages, could be formidable only to those who should attempt to discharge them. Yet as the war had but recently terminated, and this fort commanded an important part of the harbour, it might have been expected to be in a tolerable state of repair. From the fort we divided ourselves into different groups, and ascending the rocky hills that surrounded us, entered the woods which every where covered their summits. Taking a road which led through one of the thickest, I soon found myself encompassed by all the beauties of Flora. Sensations never before experienced, for some minutes, entirely overwhelmed me. It was the first time that I had ever seen the glorious productions of a tropical climate in their native soil. Plants, which in England are reared at great expense, and obtain under the best management but a puny and uncharacteristic form, flourished around me in all the vigour and luxuriance of their perfect being. A thick coppice was formed by numerous species of cassia cæsalpinia and bauhinia, whose gay colours and elegant forms were curiously contrasted with the grotesque characters of the aloe and the cactus. The trunks of the forest-trees were covered with beautiful creepers, and parasitic ferns occupied their branches. Emerging from the wood, I entered groves of orange-trees, bearing fruit and flowers in the greatest profusion. I approached them in wonder, and scarcely dared to taste their abundant produce, when I was astonished, by receiving permission to gather them in any quantity; and this permission was not confined to myself, but granted to all my companions, who successively visited the place of their growth. Indeed, nothing could surpass the liberality of the proprietors of orange-groves, or of the Portuguese peasantry whom I

* The shore on the opposite side of the harbour to that on which the city of St. Sebastian stands.

[page] 13

met with in my different excursions in the neighbourhood of Rio. Whenever they could understand me they gratified my wishes in the most prompt and obliging manner. Having laden myself with plants, I returned in the evening along the rocky beach to my boat, walking at every step over land-crabs and the larvæ of insects, whose numbers gave an appearance of animation to the soil.

On the following morning I again visited the town; and, having procured horses, went with two of the officers of the Alceste on a visit to the Sugar-Loaf Mountain, but was unable to approach it very near. I ascertained, however, that it was surrounded by interesting scenery, and determined to revisit it by water the succeeding morning.

Returning from my ride through the city of St. Sebastian, I fell in with a group of negro slaves who were assembled at the corner of a street, listening with great delight to one of their own tribe playing on a very rude musical instrument. It consisted of a few wires fixed to a small square frame, placed over a large segment of the shell of the coconut. I requested one of his companions to accompany the instrument with his voice, which he immediately did, in a monotonous, though not unpleasing tone. Another performer accompanied the last notes by wild and expressive gesticulations, in which he was followed by most of the bye-standers. It was more than probable that national remembrances animated both performers and auditors. Nothing less powerful, surely, could excite the strong emotion which agitated their frames; and I was, in some measure, confirmed in this opinion by what followed. Having bought the instrument, I slung it on my arm, and rode with it through the streets to the English hotel. Every slave whose eye caught my appendage uttered as I passed a cry of surprise: it was also one of joy and exultation. His dark countenance assumed the liveliest expression, and his whole attitude marked the strong sensation excited by the appearance of a stranger, a white and a free man, bearing, perhaps, his national emblem, under such circumstances, reviving the recol-

[page] 14

lection of that liberty and that home from which he had been impiously and for ever torn.*

The number of slaves imported into Rio Janeiro has greatly increased during the last year, in consequence of the abolition which is to take place in five years, according to the treaty between the British and Portuguese governments. But although this effect of British interference in behalf of suffering humanity is much to be deplored, the great and beneficial alteration which it has produced in the treatment of its unfortunate objects more than compensates the temporary evil. With the view of obtaining a stock of slaves that may supply the wants of the colony when the trade in them shall have become unlawful, the Portuguese have adopted the measure of selecting from the market the most vigorous and handsome of the two sexes, and establishing them in pairs in different parts of their estates. The object of this plan is sufficiently obvious, and it will probably be obtained. Promiscuous and unrestrained intercourse has been much allowed among the slaves in Rio Janeiro, and experience has of course shown that it is unfavourable to population. Whilst a ready, cheap, and exhaustless supply was open, slaveowners cared very little about the best means of keeping up their stock by breeding; but they have been induced by the apprehension that the trade will become contraband at the expiration of five years, to attempt every possible method of increasing the number of their human cattle; and as this cannot be accomplished without attention to good feeding and general comfort, they will, probably, (without any better feelings on the score of humanity,) render the state of slavery more tolerable amongst them. I blush to observe the phraseology I use in writing of my fellow men, but I can in no other

* On the subject of the slave-trade in South America, I had collected some facts during my short continuance at Rio, which I had intended to give as illustrative of its extent, increase, cruelty, and impolicy; but I find in the lucid and ample details of Mr. Koster, so complete a developement of every circumstance which it involves, that any detail from me respecting it, would be equally useless and impertinent.

[page] 15

way express the relation which exists between the master and his slave.

It is affirmed that three-fourths of the population of St. Sebastian are blacks; and, indeed, their visible number is so great, that a stranger unacquainted with the slave-trade, and visiting this city, might imagine that the slaves were its proper inhabitants, and their masters its casual dwellers. He would also be liable to conclude that its municipal laws were not very effective, as he could scarcely traverse a street without meeting troops of Africans chained together, dragging heavy clogs, or exhibiting on their shoulders the marks of lashes.

It was stated that within the last year, twenty thousand had been imported into the province of Rio Janeiro through the port of St. Sebastian, a part of whom filled the markets, and others had not yet disembarked. A ship-load of them was one of the first objects which met our sight on reaching the harbour. They were arranged upon deck, tier above tier, and their bare heads and uniform countenances, (uniform from equal expression of despondence,) exhibited a frightful picture of aggregate misery. It may be thought, perhaps, that since the slave-trade is diminishing, and the state of slavery ameliorating, these remarks are unnecessary; but, in my opinion, the. subject is not an exhausted one. Those countries that have consented through the interference of England to its abolition, have done so most reluctantly, and in no instance from principle. They all carry it on in a smuggling manner; and unless the good sense and humanity of the enlightened part of mankind be constantly on the watch against the sordid views of those persons whose immediate interest and opinions favour this bloody traffic, it will rise to all its former capabilities of inducing human misery, although its practices may not be so flagrantly displayed to the world. I much fear, from what I have heard, that in some of our own colonies, human bondage yet exists in its worst form, and still operates in producing its peculiar effect that of hardening the heart of man against the sufferings of his fellow-creatures.

[page] 16

It ought always to be kept in mind that the slave-trade, and not slavery, has been attempted to be abolished; that both exist in several parts of the world in the full possession of their horrid attributes; and, to use the words of an eloquent writer, "that from slavery in its mildest form, oppression, injustice, and cruelty are inseparable. These crimes have, from the beginning of it, formed its basis, and without them it can no more subsist than a house without a foundation."

I visited the Sugar-Loaf Mountain by water on the following day, and forgot, in the delightful scenery of its vicinage, my previous unpleasant reflections. As I approached a small fort near its base, I was challenged by a sentry, who ordered me to land, and to satisfy his officer respecting my object in visiting the coast. I obeyed, and was led into a fortress, strong in itself, but overlooked by the adjacent hills. Its commandant questioned me at first rather roughly as to my intention in coming there; but as soon as he ascertained the nature of my pursuits, and that I belonged to the British embassy, he became very civil, and described to me the nearest way to the foot of the mountain.

The Sugar-Loaf Mountain is a huge entire rock of granite, seven hundred feet in height, and owes its name to its conical form. It stands by itself, and the side facing the harbour is nearly perpendicular throughout. I had hoped to ascend to its summit, but the appearance of its precipitous sides effectually prevented my making the attempt. The scenery about its base was more pleasing than any other which I had an opportunity of seeing while at Rio Janeiro. Other parts of the country afforded views more imposing, from the immensity of their features; but they rather disappointed than satisfied the mind, from its incapacity to grasp their extent. On the contrary, in the neighbourhood of this mountain, they are on a scale within the compass of the mind's observation, and yet possess those characters of wildness, richness, and grandeur, which mark the landscape of this country. Standing on the beach, with my back to the sea, I had immediately before me the dark face of the mountain rising from a

[page] 17

wood of flowering trees. On my right hand, the same wood climbed, in a curve, the sides of precipitous ground, and was intersected by winding paths leading to a rugged rock. On the verge of this hung a picturesque cottage, and at its foot, groves of orange trees afforded a retreat from an unclouded sun, whose beams, darting through the intervals of their foliage, exhibited beautiful contrasts of light and shade. On my left, the land sloped in gentle undulations towards the sea, into which it ran in a narrow and rocky promontory; on this was built the fort near which I had landed. The effect of the scene was much heightened by the cooling sea-breezes; which, blowing over fields of flowers, came charged with delicious fragrance.

Having satiated myself with the contemplation of the objects around me, and collected many interesting birds, insects, and plants, I returned to my boat, and coasted along the rocky shore, which runs in steep declivities to the water's edge. I gathered on my way several specimens of Fuci and Confervæ, which included a greater number of species, than from the reported barrenness of these shores I had been led to expect. I doubt not, that a botanist, with a sufficient command of time, might collect from them treasures that would more than repay him for the trouble of his research. It is true, that as the shores are rocky and steep, they are seldom thrown upon land, and must therefore be gathered from their places of growth, which cannot be accomplished without frequently wading; but this, in a hot climate, is both wholesome and pleasant.

My next excursion led me to the Botanic Garden, distant about six miles from the town of St. Sebastian. The day was excessively hot; and my walk was through a deep sandy lane; but small houses of refreshment were numerous on the side of the road, which afforded the means of allaying thirst, at the most moderate expense: for three half-pence, as much lemonade, or weak brandy and water, was handed to me, as I could prudently drink. Such beverage would have been more grateful, had it partaken less of a local character; but as a traveller, I did not scruple to swallow, at every draught, a considerable number of ants, and a proportionate quan-

D

[page] 18

tity of dirt. On reaching the Botanic Garden, I received from the kindness of Senhor Gomez, its curator, refreshment of a more substantial and attractive kind.

The Botanic Garden is of considerable extent; and if its support by the Portuguese government was proportionate to the zeal of its superintendant, and the means of its improvement, it would become the first establishment of the kind in the world. The climate would favour the growth of all the plants of the east; and there can be no doubt, that such of them as afford commercial produce, might be cultivated with success and profit. But it has no other care bestowed on its management than what it receives through the judgment and exertion of Senhor Gomez, whose particular appointment is that of superintendant of some powder-mills situated in its neighbourhood.

This gentleman has, notwithstanding the defects of its establishment, contrived through the aid of a few Chinese gardeners, to cultivate the Tea-plant with great success. It was in seed at the time of my visit, and its leaves had been repeatedly and effectively-manufactured. The process pursued is very simple. The leaves are gathered in the month of January, after heavy falls of rain, before they are wholly expanded, care being taken that no foot-stalks are mingled with them; they are then put into an iron vessel, and exposed to heat till they begin to shrink; when they are taken out, and rolled between the hands till they become spirally folded. They are then returned into the vessel, and again exposed to heat till it becomes intolerable to the hand, which continually agitates them, to prevent their burning; and thus the process is finished.

Many other Chinese plants, besides the Tea, were growing in the garden in full vigour. Amongst these, the Tallow-tree (Stillingia Sebifera), the Wax-tree (Ligustrum Lucidum), and Camellia Sesanqua, were the most conspicuous. The last-mentioned plant, Senhor Gomez was disposed to call the Thea Oleifera, from the belief, that it is not a Camellia, but a Thea, and that it is the Oil-plant of the Chinese. In the former opinion, he is probably correct; in the latter, he accords with the statement of others; but in another part

[page] 19

of this work, I shall have occasion to show, that the Camellia sasanqua is not the oil plant of the Chinese. The Cactus opuntia, which was formerly cultivated in this garden for the purpose of rearing the Cochineal insect, is now altogether neglected.

The Ipecacuanha plant of the Brazils grows in great quantity in the woods in the neighbourhood of the Botanic Garden, whence it is collected by the country people for the market. I lamented much, that the shortness of my stay at Rio di Janeiro prevented my obtaining this plant, of which so many confused accounts have been given. The difficulty of determining the plants producing the Ipecacuanha of commerce, appears to have been occasioned by the supposition, that it is entirely derived from one species; whereas there can be no doubt that it is afforded by two at least of different genera. A short history of the descriptions given of these by various writers, will perhaps be decisive in showing from what plants it is all obtained.

Piso and Margraave were the first who described the Ipecacuanha plant of the Brazils, but neither their figures nor descriptions were sufficiently precise to determine its genus. In 1781, Linnaeus published a description which he had received from Mutis, governor of Santa Fe, of the Ipecacuanha plant of New Spain, under the genus Psychotria.* In 1801, a complete monograph of the Ipecacuanha plant of the Brazils was published by Brotero† at Lisbon, from specimens furnished to him by Bernardino Antonio Gomez, who accompanied them by a dissertation on the characters, properties and culture of the plant. It was named by these authors Callicocca ipecacuanha. The plant of Gomez and Brotero has since been confounded with that of Mutis: in other words, the Psychotria emetica of Linnaeus, and the Callicocca Ipecacuanha of Brotero, have been referred to the same plant‡ by Persoon, who has described

* Linn. Supplem. Plant. p. 144.

† Memoria sobre A. Ipecacuanha Fusca, p. 57.

‡ Persoon, Synopsis, p. 203.

* D 2

[page] 20

it under the genus Cephaelis. That they are essentially distinct, however, will readily appear from the comparison of their descriptions given in the Appendix.* Humboldt† and Bonpland have also very lately described and figured the Psychotria emetica as the Ipecacuanha of New Spain.

The Callicocca ipecacuanha grows, according to Brotero, in shady and moist places in Pernambuco, Bahia, Rio di Janeiro, and other provinces of the Brazils. The Psychotria emetica according to Humboldt "is cultivated in the warm and humid valleys of the mountains of San Lucar, near Simiti and Giron; and also in the district called La Vara de Guammoco, to the west of the river Magdalen." It is therefore evident, that two plants of different genera, one a native of North, the other of South America, produce the Ipecacuanha of commerce. The first reaches Europe from Carthagena in America, by the way of Cadiz; and the latter probably from the ports of St. Sebastian and St. Salvador, through Lisbon.

The plant which grows in the neighbourhood of the Botanic Garden was, indeed, supposed by Senhor Gomez, to be the Psychotria emetica of Linnaeus; but the description with which he favoured me proves, I think, that it is the Callicocca of Brotero.‡

Two other plants also grew in the immediate vicinity of the Botanic Garden, which possess emetic and purgative properties, but in a less degree than the Psychotria or Callicocca. These are also collected for medicinal purposes, and are sometimes confounded with, and sold for the true Ipecacuanha. They are the Richardia scabra of Linnaeus, called in Rio the White Ipecacuanha, probably the

* See Appendix, A.

† Plantes Equinoxiales.

‡ "Calix — Involucrum tetraphyllum.

Corolla — Infundibuliform: 5 fid.

Stamina — 5 intra tubum. Antheris simplicibus.

Pistillum — Germen ovatum. Stilus brevis. Stigm: bifid:

Pericarp. Bacca flaccida 2 sperm. Semina, arillata, sulcata, contorta, hinc convexa, inde plana."

[page] 21

Ipecacounha Blanca of Piso, and the Viola Ipecacuanha of Linnæus, known under the name of the false Ipecacuanha.

During the time I remained at the Botanic Garden, I received every possible attention from S. Gomez, and lamented much that the advance of the day obliged me to quit it when I had seen only a small portion of its treasures.

As I returned to St. Sebastian, my path was illuminated by myriads of fire flies, whirling in the air, or lighting on trees. At a distance these insects resembled stars of great brilliancy, but as I approached them, their rapid and varied motion, and their vivid scintillations amidst dense foliage, disclosing patches of its most attractive hues, exhibited a transporting scene of novelty and beauty. It was perhaps equalled by the waves of silvery light, over which the boat glided that carried me from the shore to the Alceste.

One more excursion completed my opportunities of examining the scenery and productions of Rio. In this I visited many of the islands, scattered in great numbers over its harbour. These are much diversified in their forms, but are all of a similar geological structure. Their basis is granite, with large flesh-coloured crystals of Felspar. Their surface is a thin but rich soil of a red colour, and formed by the decomposition of the rock beneath. They are clothed with a luxuriant foliage, mingled with blossoms, whose colour and fragrance is only surpassed by the flavour and refreshing qualities of their fruits. Oranges, bananas, Cashew apples, and water melons, are their common produce.

These islands vary very much in size, being from 200 yards to one mile in diameter, and are frequently occupied by a single habitation. The oranges which grow on them were larger, more juicy, and of a better flavour than any I had tasted from the main land. The sailors were permitted to gather them in any quantity, with no other request on the part of their owners, than that care should be taken not to break the branches of the trees.

These well clothed islands are in some respects less interesting than the bare rocks in their neighbourhood, which rise in isolated

[page] 22

masses from the surface of the water. They are generally of a conical form, rising from 10 to 50 feet in height, and are seldom more than 60 or 100 feet in circumference. They seem to be the apices of cones, whose bases are under water. I sounded round one of the smallest, and found within a yard of its side 15 feet water, which rapidly deepened as I withdrew from it. The larger of these rocky islets do not consist of single masses, but are broken into several of singular shapes. In more than one instance, I saw a large cone of granite, 30 feet high, split from its very apex to its base, the parts of which had seceded against their gravity; proving, I imagine, that their separation could not have been the consequenee of disintegration. Was it produced by a cause coeval with their appearance above the surface of the water?

Could I have dwelt on the appearances presented by the exposed surfaces of these rocks, I should have found perhaps many interesting geological facts, traced upon them in very legible characters. But the time I was enabled to spend in their examination allowed me to derive little else from their contemplation than the pain of awakened, but unsatisfied curiosity.

My pursuits having separated me from the suite of His Excellency, I lost the opportunity of witnessing the funeral solemnities of the Queen of Portugal. But from the information I obtained from those who saw them, I missed but little which my imagination had not supplied. I heard the tolling of bells, and the firing of cannon; and when to these my fancy added their other elements in the church, illumination, magnificent bier, chanting, and solemn response; in the streets, the glare of torches, priests, and nobles in procession, crowds of by-standers, and soldiers keeping the ground, I formed a picture which, if not agreeable to reality, was at least satisfactory to myself.

On taking leave of Rio de Janeiro, I feel desirous of leaving on the minds of my readers some general notion of the characteristic features of the city of St. Sebastian, and of the country in its neighbourhood; but I fear any description in my power to give would be

[page] 23

inadequate to this object. The strongest efforts of the imagination cannot picture any thing so heavenly as the country, or so disgusting as the town. The first contains many of the noblest works of nature in their greatest freshness and beauty, on a magnificent scale; the latter exhibits all the disgusting objects which pride, slavery, laziness, and filth can possibly engender. When I state that the face of high mountains is often covered with a sheet of blossom, a faint apprehension may perhaps be formed of the beauties of the country; but when I aver that on entering some parts of the town, I almost lamented that I had an organ of smell, I give no idea of the stench which exhales from the accumulated ordure of its streets.

[page] 24

CHAPTER II.

THE Alceste left the harbour of Rio de Janeiro on the morning of the 31st of March, and after a very rapid passage, arrived off the Cape of Good Hope, and anchored in Table Bay, on the afternoon of the 18th of April.

We remained at the Cape till the 5th of May, when the Alceste sailed for the Straights of Sunda. The Lyra and General Hewitt had been dispatched nine days before, but our superior sailing enabled us to gain rapidly upon them, and we anchored in Anyer Roads on the 9th of June, two days after them.

Whilst at anchor I had an opportunity of examining a large shark, which was taken the day after our arrival. This animal, which measured twelve feet in length, was torn in pieces by the sailors the instant it was fairly on deck. They drew from its stomach a whole buffaloe's hide, two buffaloes' tails, one whole fowl, and the bones of another, the remains of several snakes, and a mass of matter of which it was impossible to ascertain the nature.

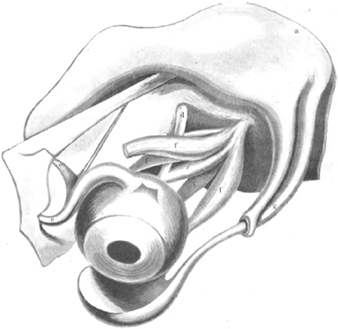

With some difficulty I made sufficient interest with its furious mutilators, to obtain its eye, the structure of which I was anxious to learn. It is supported on a firm cartilaginous stem, which arises from the bottom of the socket*, and passing by the side of the optic nerve, is articulated to the ball by a joint which permits motion in every direction. This joint is the centre of motion to six strong muscles that arise from the interior of the orbit, and are so inserted in the ball of the eye, that their whole action

* This structure has been pointed out by a celebrated naturalist, who considers the cartilaginous stem as a lever to the muscles. The same naturalist also observes, that the stem is articulated with the lower part of the orbit. Leçons d'Anatomie Comparéc, tom. ii. p. 425.

[page] 25

amounts to the circumference of a circle, whose diameter is that of the portion of the ball comprehended within their points of insertion. This organisation seems necessary in the shark, which takes its prey by turning on its back, to enable it to keep its object in view when preparing to seize it. The eye balanced on a pivot is obviously capable of a greater extent of motion, in any direction, than when imbedded in the gelatinous matter, which lines the eye-sockets of most other fish.