[page ii]

[page iii]

AN

ACCOUNT

OF THE

ARCTIC REGIONS,

WITH A

HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION

OF THE

NORTHERN WHALE-FISHERY.

BY

W. SCORESBY Jun. F.R.S.E.

ILLUSTRATED BY TWENTY-FOUR ENGRAVINGS.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED FOR ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND CO. EDINBURGH:

AND HURST, ROBINSON AND CO. CHEAPSIDE, LONDON.

1820.

[page iv]

P. Neill, Printer.

[page v]

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

NORTHERN WHALE-FISHERIES, &c.

| Page | |

| CHAP. I.—CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY of the Northern Whale-Fisheries, | 1 |

| CHAP. II.—Comparative View of the Origin, Progress, and Present State of the Whale-Fisheries of different European Nations, | 96 |

| SECT. 1. Whale-Fishery of the British, | 98 |

| 2. Whale-Fishery of the British Colonies in America, | 134 |

| 3. Whale-Fishery of the Dutch, | 138 |

| 4. Whale-Fishery of the Spaniards, French, Danes, Germans, Norwegians, Prussians and Swedes, | 161 |

| CHAP. III.—Situation of the early Whale-Fishery,—Manner in which it was conducted,—and the Alterations which have subsequently taken place, | 172 |

| CHAP. IV.—Account of the Modern Whale-Fishery, as conducted at Spitzbergen, | 187 |

| SECT. 1. Description of a well-adapted Greenland Ship, with the additional strengthenings reouisite for resisting the Concussions of the Ice, | 187 |

| 2. Proceedings on board of a Greenland Ship, from putting to sea to her arrival on the Coast of Spitzbergen, | 199 |

[page] vi

| SECT. 3. Observations on the Fishery of different latitudes and seasons, and under different circumstances of ice, wind and weather, | 207 |

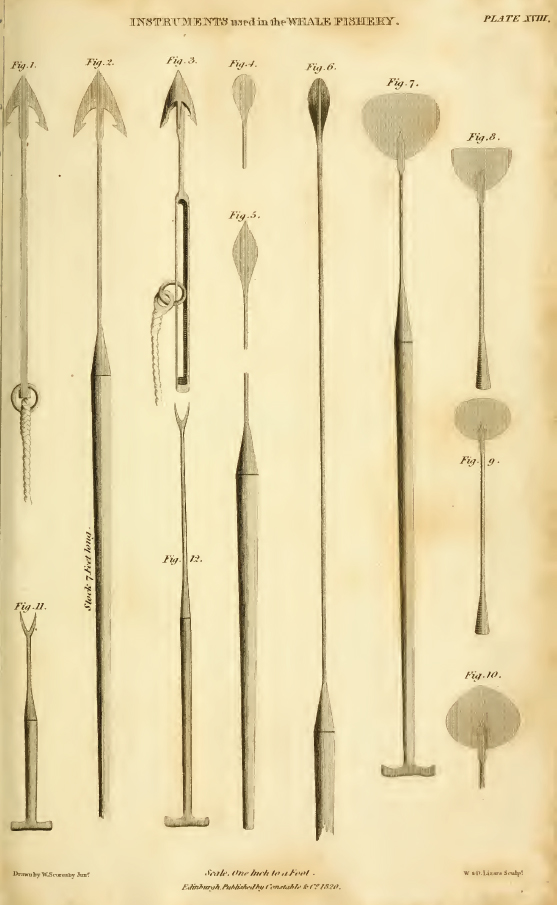

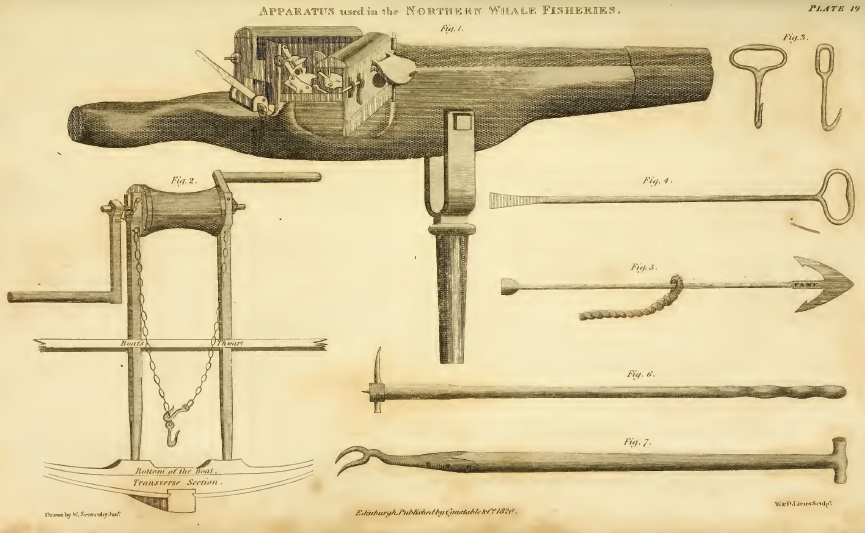

| 4. Description of the Boats and principal Instruments used in the capture of the Whale, | 221 |

| 5. Preparations for the Fishery, | 230 |

| 6. Proceedings on Fishing Stations, | 236 |

| 7. Proceedings in capturing the Whale, | 240 |

| 8. Alterations produced in the manner of conducting the Fishery, by peculiar circumstances of Situation and Weather, | 257 |

| a. Pack-fishing, | ib. |

| b. Field-fishing, | 259 |

| c. Fishing in crowded Ice, or in open Packs, | 266 |

| d. Bay-Ice-fishing, | 268 |

| e. Fishing in Storms, | 272 |

| f. Fishing in Foggy Weather, | 273 |

| 9. Anecdotes, illustrative of peculiarities in the Whale-Fishery, | 276 |

| 10. Proceedings after a Whale is killed, | 292 |

| 11. Process of Flensing, | 298 |

| 12. Process of Making-off, | 304 |

| 13. Laws of the Whale-fishery, | 312 |

| 14. Remarks on the Causes on which Success in the Whale-fishery depends, | 333 |

| 15. Anecdotes illustrative of the Dangers of the Whale-fishery, | 340 |

| a. Dangers from Ice, | 341 |

| b. ——the nature of the Climate, | 346 |

| c. ——the Whale, | 356 |

| 16. Proceedings in a Greenland Ship, from leaving the Fishing Stations, to her arrival in Britain, | 369 |

| 17. Legislative Regulations on the Importation of the Produce of the Northern Whale-fisheries, | 378 |

[page] vii

| CHAP. V.—Account of the Davis' Strait Whale-Fishery, and a comparison with that of Greenland, with Statements of Expences and Profits of a Fishing Ship, | 382 |

| SECT. 1. Some account of the Whale-fishery, as at present conducted in Davis' Strait, and on the Coast of Labrador, | ib. |

| 2. Comparative View of the Fisheries of Green-land and Davis' Strait, | 390 |

| 3. Statements of Expences and Profits on some Whale-fishing Voyages, | 393 |

| CHAP. VI.—Method of Extracting Oil and Preparing Whalebone, and Remarks on the uses to which the several products of the Whale-Fishery are applied, | 397 |

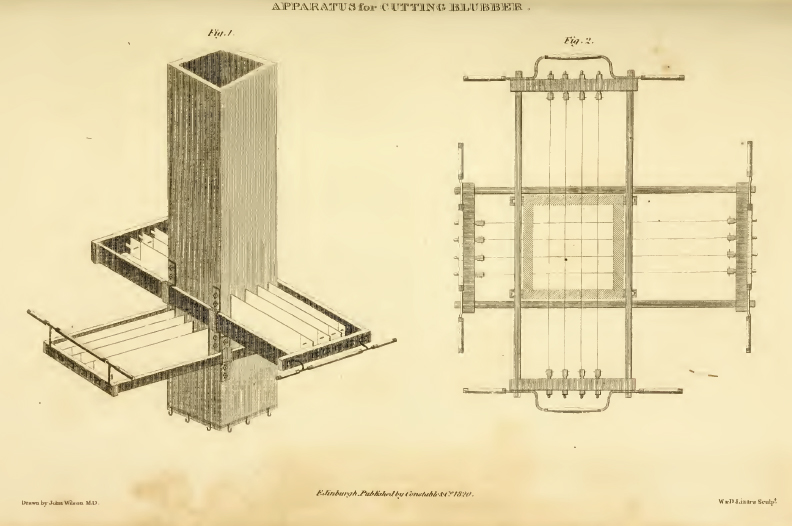

| SECT. 1. Description of the Premises and Apparatus used in extracting Oil out of Blubber, | 397 |

| 2. Process of Boiling Blubber or Extracting Oil, | 400 |

| 3. Description of Whale-Oil, and Remarks on the cause of its offensive smell, | 408 |

| 4. Description of Whalebone, and of the Method of Preparing it, | 415 |

| 5. Remarks on the Uses to which the Oil, Fenks, Tails, Jawbones, and other produce of Whales are applicable, | 420 |

| CHAP. VII.—Narrative of Proceedings on board of the Ship Esk, during a Whale-Fishing Voyage to the coast of Spitzbergen, in the year 1816, | 438 |

[page] viii

APPENDIX

| Page | |

| No. I.—Abstract of the Acts of Parliament at present in force for the Regulation of the Whale-fisheries of Greenland and Davis' Strait, | 491 |

| II.—1. Some Remarks on the most advantageous Dimensions of a Whale-Ship, | 506 |

| 2. Additional Notices respecting the Fortifications of a Greenland Ship, | 508 |

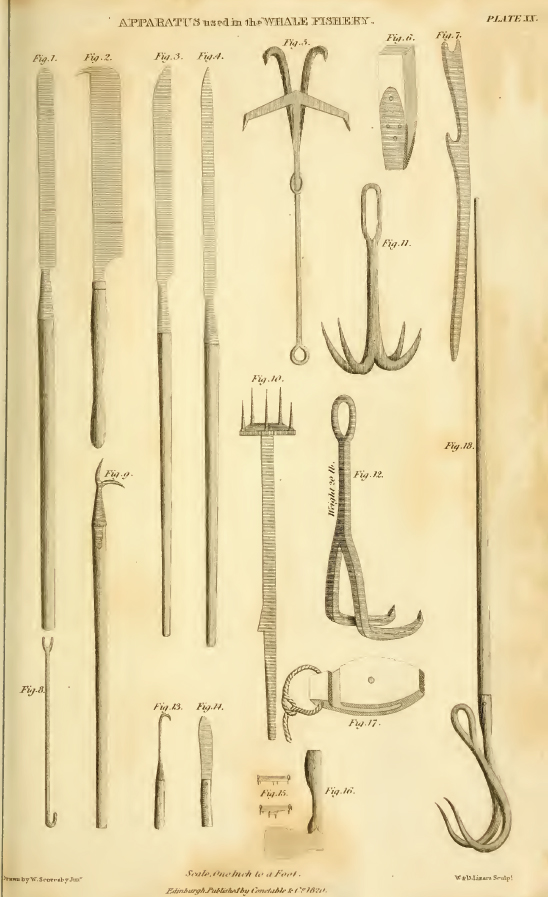

| III.—Schedule of the Principal Fishing Apparatus necessary for a Ship, of 300 tons burden or upwards, intended to be employed in the Greenland Trade, | 509 |

| IV.—Manner of Mustering the Crew of Whale-Ships, with some account of the Affidavits, Certificates, &c. required by Law, | 512 |

| V.—Account of a Trial respecting the right of the Ship Experiment, to a Whale struck by one of the Crew of the Neptune; Gale v. Wilkinson, | 518 |

| VI.—Signals used in the Whale-fishery, | 521 |

| 1. General Signals, | 522 |

| 2. Particular Signals, | 524 |

| VII.—Account of some Experiments for determining the Relations between Weight and Measure in certain quantities of Whale-Oil, | 525 |

| VIII.—Some account of the Whale Fishery conducted in the Southern Seas, | 529 |

| IX.—Observations and Deductions on the Anomaly in the Variation of the Magnetic Needle, as observed on Ship-board, | 537 |

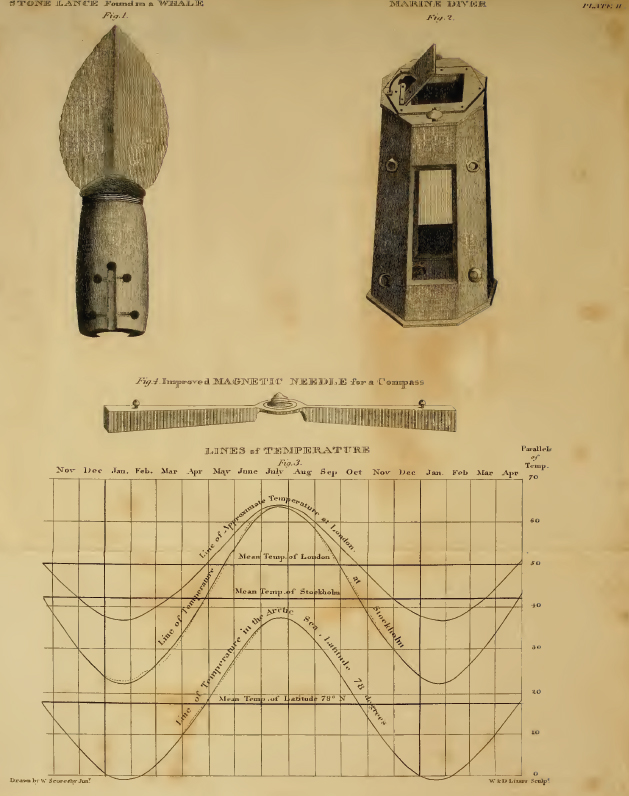

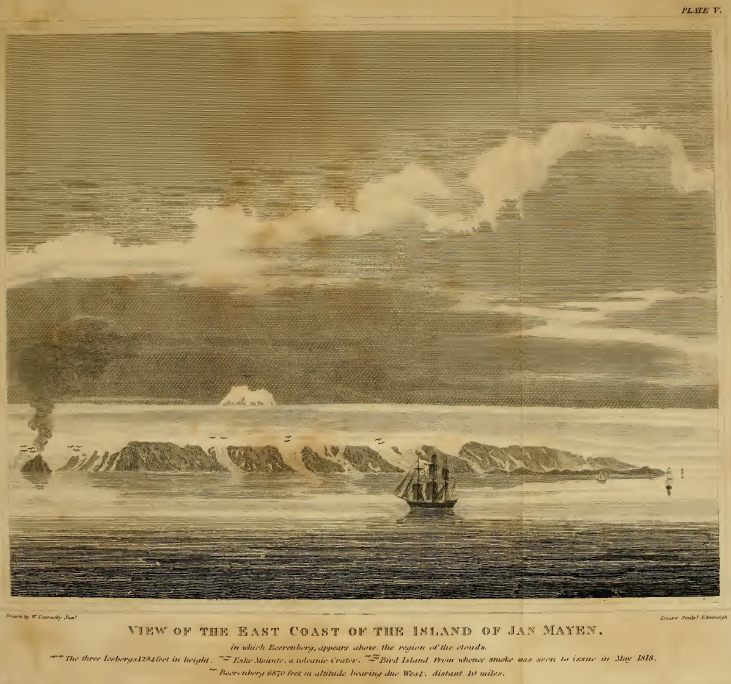

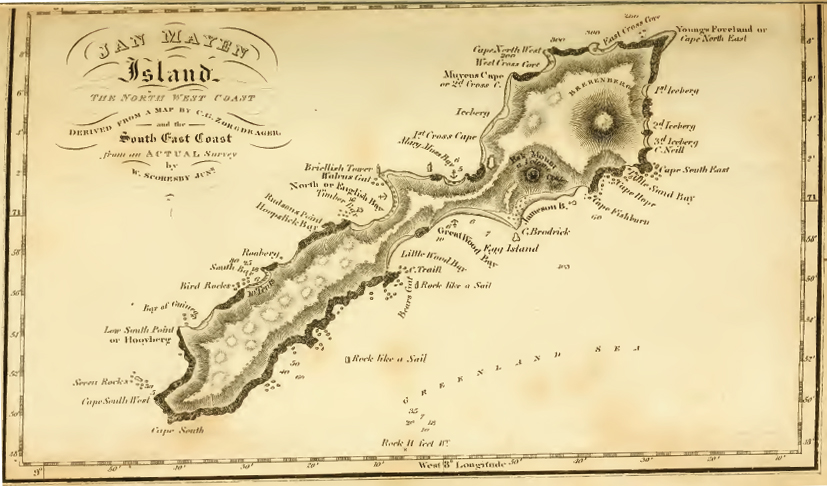

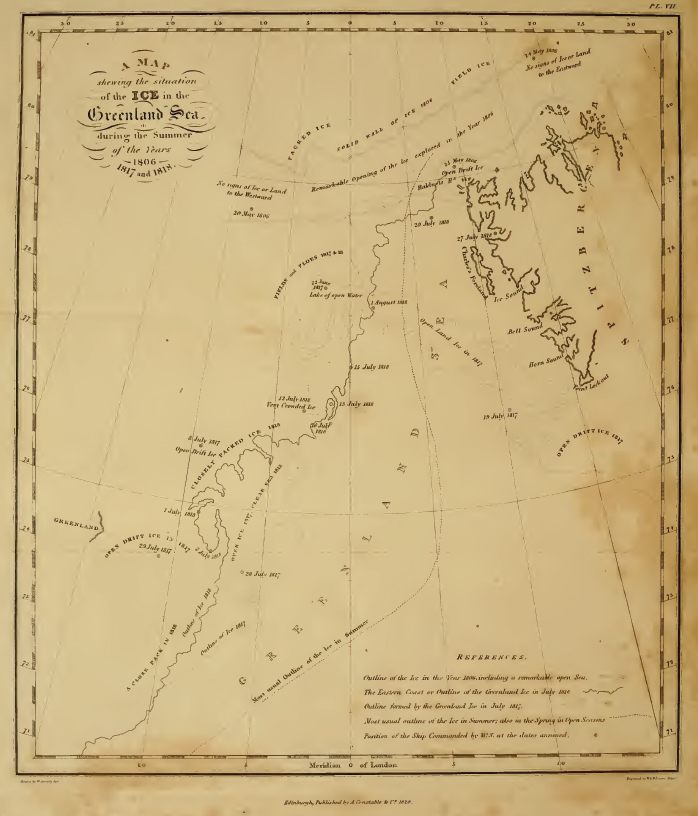

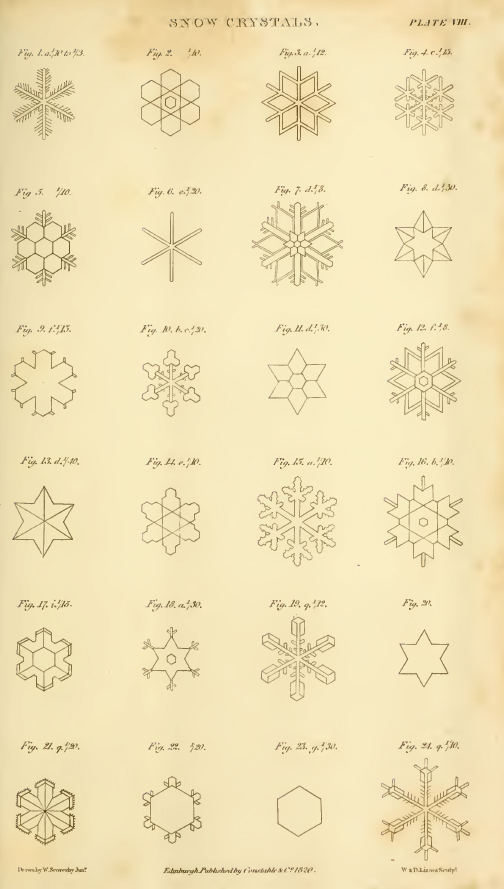

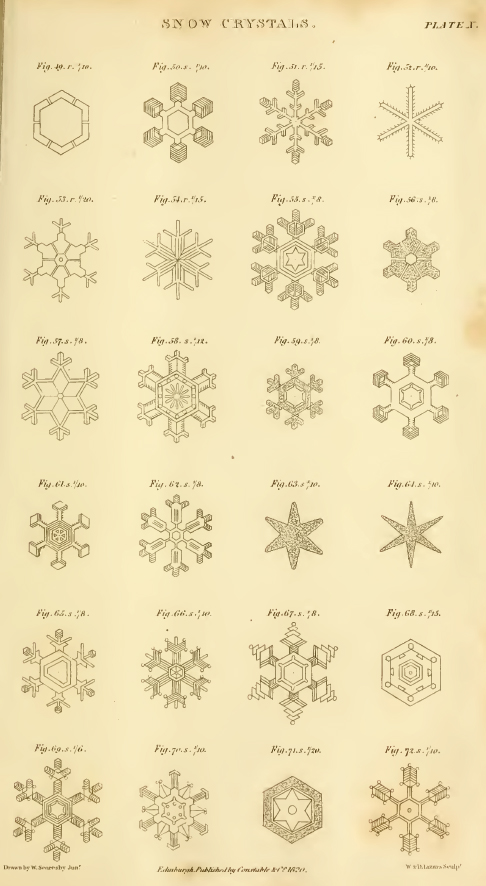

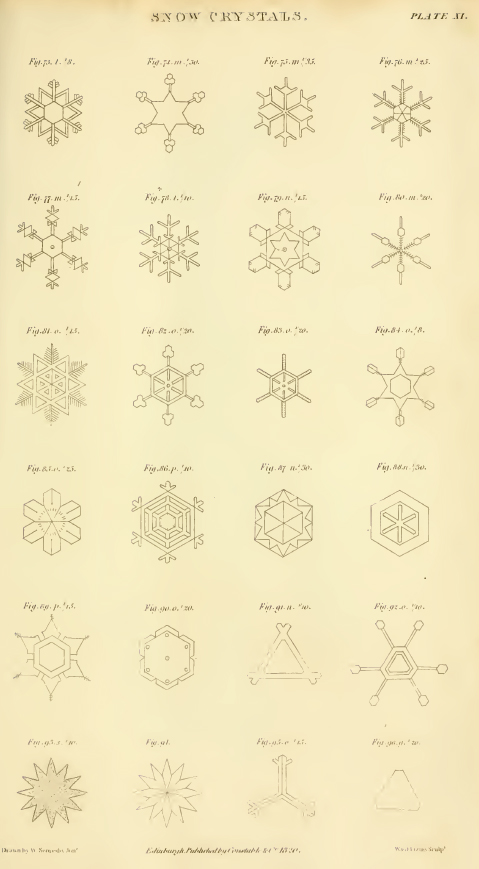

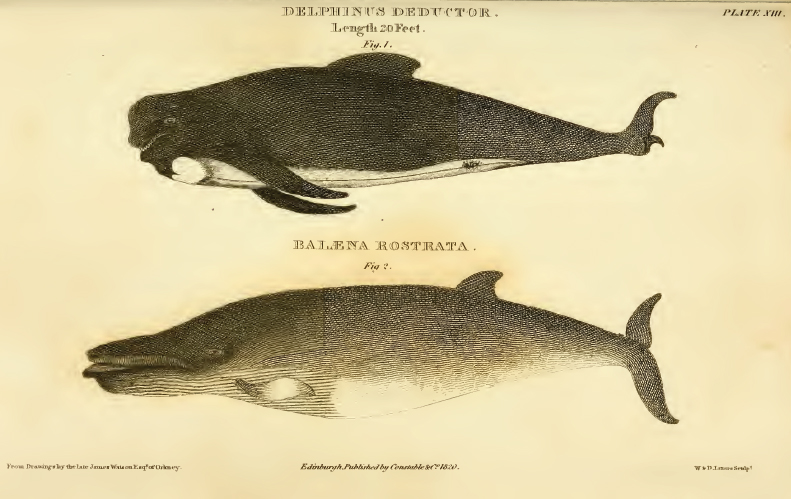

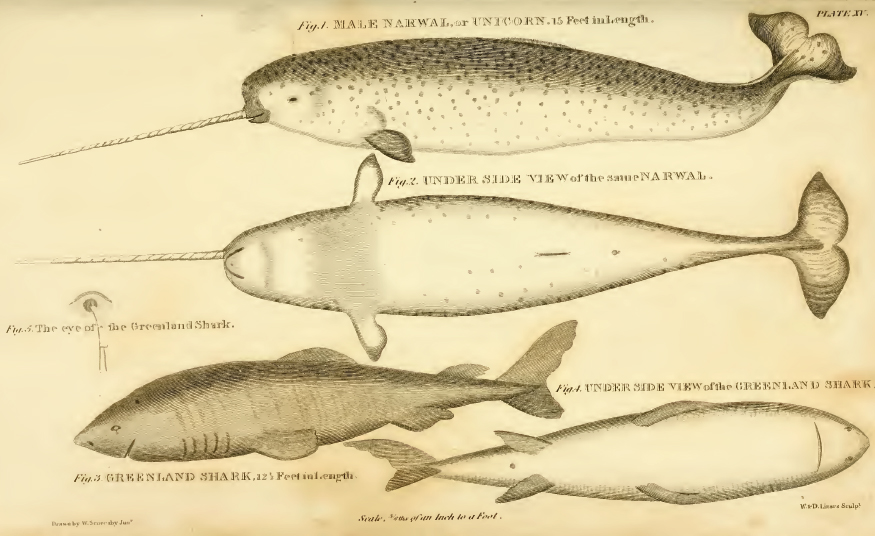

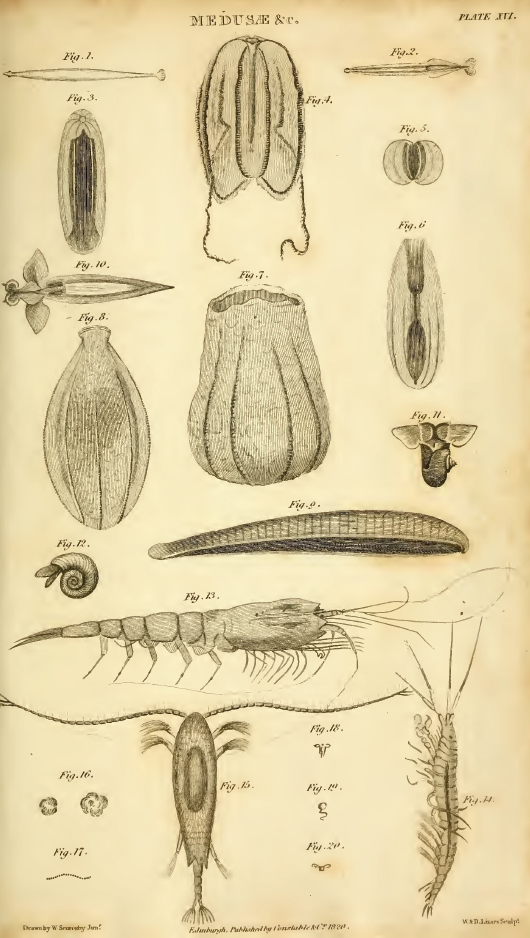

| X. Explanation of the Plates, | 552 |

| INDEX, | 561 |

[page 1]

ACCOUNT

OF THE

NORTHERN WHALE-FISHERIES,

&c.

CHAPTER I.

CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE NORTHERN WHALE-FISHERIES.

IN the early ages of the world, when beasts of prey began to multiply and annoy the vocations of man, the personal danger to which he must have been occasionally exposed, would oblige him to contrive some means of defence. For this end he would naturally be induced, both to prepare weapons, and also to preconceive plans for resisting the disturbers of his peace. His subsequent rencounters with beasts of prey would therefore be more frequently successful; not only in effectually repelling them when they should attack him, but also in some instances in accomplishing their destruction. By ex-

VOL. II. A

[page] 2

perience, he would gradually discover more safe and effectual methods of resisting and conquering his irrational enemies; his general success would beget confidence, and that confidence at length would lead him to pursue in his turn the former objects of his dread, and thus change his primitive defensive act of self-preservation into an offensive operation, forming a novel, interesting, and noble recreation. Hence we can readily and satisfactorily trace to the principle of necessity, the adroitness and courage evidenced by the unenlightened nations of the world, in their successful attacks on the most formidable of the brute creation; and hence we can conceive, that necessity may impel the indolent to activity, and the coward to actions which would not disgrace the brave.

If we attempt to apply this principle to the origin of the schemes instituted by man, for subduing the cetaceous tribe of the animal creation, it may not at the first sight appear referable to the exigence of necessity. For man to attempt to subdue an animal whose powers and ferocity he regarded with superstitious dread, and the motion of which he conceived would produce a vortex sufficient to swallow up his boat, or any other vessel in which he might approach it,—an animal of at least six hundred times his own bulk, a stroke of the tail of which might hurl his boat into the air, or dash it and himself to pieces,—an animal inhabiting at the

[page] 3

same time an element in which he himself could not subsist;—for man to attempt to subdue such an animal under such circumstances, seems one of the most hazardous enterprises, of which the intercourse with the irrational world could possibly admit. And yet this animal is successfully attacked, and seldom escapes when once he comes within reach of the darts of his assailer.

In tracing from a principle of necessity the progress of such a difficult and hazardous undertaking, from its first conception in the mind to its full accomplishment; in the existing deficiency of authentic records, much must be left to speculation. The following view may at least be considered as plausible.

It seems to be the opinion of most writers on the subject of the Whale-Fishery, that the Biscayans were the first who exercised their courage in waging a war of death with the whales, and succeeded in their capture. This opinion, though, perhaps, not correct, as will hereafter appear, is yet a sufficient foundation for investigating the probable origin of this remarkable employment. These people, like the inhabitants of almost all sea-coasts, were employed, principally, in the occupation of fishing. A species of whale, probably the Balæna rostrata, was a frequent visitor to the shores of France and Spain. In pursuit of herrings and other small fishes, these whales would produce a serious destruc-

A 2

[page] 4

tion among the nets of the fishermen of Biscay and Gaseony. Concern for the preservation of their nets, which probably constituted their principal property, would naturally suggest the necessity of driving these intruding monsters from their coasts. With this view, the use of fire-arms, or, supposing the capture of these animals by the Basques and Biscayans to have been effected prior to the invention of gunpowder (A. D. 1330), which was probably the case, the use of arrows and spears would naturally be resorted to. On shooting at the whales, either by means of the how or the musket, they would doubtless be surprised to find, that, instead of their being the ferocious, formidable, and dangerous animals they had conceived, they were timid and inoffensive. This observation would have a tendency to supply them with such additional confidence and courage, that the most adventurous, from motives of emulation, the prospect of profit, or even from a principle of fool-hardiness, might be induced to approach some individual of the species, and even dart their spears into its body. Perceiving that it evinced no intention of resistance, but that, on the contrary, it immediately fled with precipitation to the bottom of the sea, and that, on its return to the surface, it was quite exhausted, and apparently in a dying state; they might conceive the possibility of entangling some of the species, by means of a cord attached to a barbed arrow or spear. If, to the

[page] 5

end of this cord they attached one of the buoys used in their common fishing occupations, it would point out the place of the wounded animal, fatigue it in its motions, and would possibly goad it on to produce such a degree of exhaustion, that it might fall an easy prey to these adventurous fishermen. One of these animals being thus captured, and its value ascertained, the prospect of emolument would be sufficient to establish a fishery of the cetaceous tribe, and lead to all the beneficial effects which have in modern times resulted.

Historians, in general, it has been observed, have given to the Biscayans the credit of having first succeeded in capturing the whale upon the high sea. Those authorities, indeed, may be considered as unquestionable, which inform us, that the Basques and Biscayans, so early as the year 1575, exposed themselves to the perils of a distant navigation, with a view to measure their strength with the whales, in the midst of an element constituting the natural habitation of these enormous animals; that the English in 1594, fitted an expedition for Cape Breton, intended for the fishery of the whale and the walrus (seahorse), pursued the walrus-fishing in succeeding years in high northern latitudes, and in 1611 first attacked the whale near the shores of Spitzbergen; and that the Hollanders, and subsequently, other nations of Europe, became participa-

[page] 6

tors in the risk and advantages of these northern expeditions. Thus, according to these writings, the Basques and Biscayans, then the English, and afterwards the Dutch, were the nations who first practised the fishery for the whale. Some researches on the origin of this fishery, carried on in the northern seas, however, will be sufficient to rectify the error of these conclusions, by proving, that the whale-fishery by Europeans may he traced as far back, at least, as the ninth century*.

Oppien, in his treatise de Piscatu, has left some details of the ancient whale-fishery, which, however, we shall pass over; because he seems to refer principally, if not altogether, to the smaller species of whales of the genus Delphinus. We, therefore, go on to authority which is more respectable.

The earliest authenticated account of a fishery for whales, is probably that contained in Ohthere's Voyage by Alfred the Great. This voyage was undertaken about the year 890 by OHTHERE a native of Halgoland, in the diocese of Dronthein, a person of considerable wealth in his own country, from motives of mere curiosity, at his own risk, and under his own personal superintendence. His enterprise was communicated by the navigator himself to King Alfred, who preserved it, and has handed it

* NOEL.

[page] 7

down to us in his translation of Orosius*. On this occasion, Ohthere sailed to the northward along the coast of Norway, round the North Cape, to the entrance of the White Sea. Three days after leaving Dronthein or Halgoland, "he was come as far towards the north, as commonly the whale-hunters used to travel†." Here Ohthere evidently alludes to the hunters of the walrus or seahorse; but subsequently, he speaks pointedly as to a fishery for some species of cetaceous animals, having been at that period practised by the Norwegians. He told the King, that with regard to the common kind of whales, the place of most and best hunting for them

* The work of Orosius is a summary of ancient history, ending with the year 417, at which period he lived. He was a Spaniard and a Christian. To this translation, Alfred added, of his own composition, a Sketch of Germany, and the valuable Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan, the former towards the North Pole, the latter into the Baltic Sea. The principal MS. of Alfred's Orosius, which is very ancient and well written, is preserved in the Cotton Library, Tiberius, b. 1. In 1773, the Honourable Daines Barrington published the Anglo-Saxon Orosius, with an English translation. His MS. was a transcript formerly made of this.—Turner's Anglo-Saxons, vol. ii. p. 282, 283, and 284.

† Hackluyt's Voyages, vol. i. p. 4. Turner's History of the Anglo-Saxons, vol. ii. p. 288.–296, reads, "Three days was he as far north as the whale hunters farthest go."—"Da ves he sva feor nord sva sva hoœl huntan fyrrest farad.".

[page] 8

was in his own country; whereof some be 48 ells of length, and some 50, of which sort, he affirmed, that he himself was one of the six who in the space of three (two) days, killed threescore*. From this it would appear, that the whale-fishery was not only prosecuted by the Norwegians so early as the ninth century, but that Ohthere himself had personal knowledge of it. But when he affirms, that himself, with five men, captured 60 of these whales in two days, when it is well known that fifty men, under the most favourable circumstances, and in the present improved state of the fishery, could not have taken one-half, or even one-third of that number in the same space of time, of any of the larger species of whales,—we are naturally led to question the authenticity of the account, as far as relates to this transaction; and in questioning one part, throw a shade of doubt over the whole narrative. As, however, the voyage of Ohthere is a document of much value in history, both in respect to the matter of it, and the high character of the author by whom it has been preserved, it were well to examine carefully this circumstance, before we decide on a point so important. Hitherto I have followed Hackluyt; but if we refer to the original, we shall find, that Hackluyt himself, is probably, in this instance, the

* Hackluyt's Voyages, vol. i. p. 4.

[page] 9

occasion of the apparent inconsistency. Turner, in his "History of the Anglo-Saxons," gives a copy in the original language of this part of Alfred's Orosius, taken from the principal manuscript preserved in the Cotton Library. In reference to this passage, where the remarkable exploit of Ohthere is recorded, he observes, that the Saxon words of this sentence have perplexed the translators. He has ventured to give it some meaning, by supposing, that syxa is an error in the manuscript, and should be f xa; by which alteration the passage reads, "On his own land are the best whales hunted; they are 48 ells long, and the largest 50 ells. There, he said, that of (fyxa) some fish, he slew sixty in two days*." Thus, the whale here referred to, might,

* The words of the original are, "Ac on his agnum lande is se bets'ta hwœl huntath tha beoth eahta and feowertiges elna lange, tha mæstan fiftiges elna lange, thara he sæde thæt he syxa (or fyxa) sum of sloge syxtig on twam dagnum." Turner's Anglo-Saxons, vol. ii. p. 292. note.

The Honourable Daines Barrington, in the account of Ohthere's Voyage, published in his "Miscellanies," translates the passage, containing his exploit in the whale-fishery, in the words, "That he had killed some six; and sixty in two days;" but, conscious of the unintelligibleness of the sentence, he observes in a note, that "Syxa," he conceives, "should be a second time repeated here, instead of syxtig or sixty; it would then only be asserted, that six had been taken in two days, which is much more probable than sixty." (p. 462.)

[page] 10

possibly, be that species of Delphinus, so frequently driven on shore in great numbers at Orkney, Shetland, and Iceland, in the present age; where, in this way, a few small boats have been known to capture even a larger number than Ohthere speaks of, in one day. If so, though it does not contradict or explain away the fact, of larger whales having been likewise hunted and captured, it removes the objection as to the improbability of the exploit recorded, and enables us to adhere with greater confidence to our authority of the great antiquity of the whale-fishery by the Norwegians.

In various ancient authors, we have accounts of whales as an object of pursuit; and by some nations held in high estimation as an article of food. Passing over the notices of these animals by the classic authors as objects of peculiar dread, or as prognostics of peculiar events, I proceed to the consideration of those which mention the whale in the way of fish-cry or capture, as my more immediate object*.

* For the following researches relative to the ancient history of the Whale-fishery., up to the middle of the sixteenth century, I am chiefly indebted to a "Mémoire sur l'Antiquité de la Pêche de la Baleine par les Nations Européennes," by S. B. J. NOEL, Paris, 1795, 12mo. The greater part of the references I have compared with the originals; and where the spirit of the language has been altered by the translation. I have endeavoured to correct it.

[page] 11

A Danish work*, which, there is reason to suppose, was written about the middle of the twelfth century, hut, at any rate, of a date much earlier than that which we assign to the first fishery of the Basques, declares, that the Icelanders, about this period, were in the habit of pursuing the whales, which they killed on the shore, and that these islanders subsisted themselves on the flesh of some one of the species†. And Langebek does not hesitate to assert‡, that the fishery of the whale (hvalfangst) was practised in the most northern countries of Europe, in the ninth century.

Whether the Normans, in the different invasions which they made on France, might have carried the method of harpooning and capturing the whale thither, or whether these processes, as I have before suggested, were known and practised by the fishermen inhabiting the Bay of Biscay before their incursions, is uncertain; nevertheless it would appear, that the French were not unacquainted with the business at a very remote period. Under the

* Kongs Skugg-sio, 121.

† The whale here referred to, is probably the species of Delphinus, usually called Bottle-nose, which is yet occasionally driven on shore by the inhabitants of Shetland, Orkney, Feroc, and Iceland.

‡ Langebek, Rer. Dan. hist. med, ævi, ii. 108.

[page] 12

date of 875, in a book, entitled the Translalion and Miracles of St Vaast*, mention is made of the whale-fishery on the French coast. In the Life of St Arnould, bishop of Soissons†, a work of the eleventh century, particular mention is made of the fishery by the harpoon, on the occasion of a miracle performed by the Saint. Some Flemish fishermen had wounded, with strokes of their lances, a large whale, the capture of which they believed to be certain, when suddenly, regaining his strength, the animal struggled so violently, that he was on the point of escaping from them. At this critical juncture, they considered their only resource was to invoke the Saint, say their légendaire, and promise him a part of the fish, if he would be propitious in assisting them to subdue it. The offering was happily accepted; and, to their joy, the same instant, the whale is said to have suffered them to approach it, and without further resistance was killed, and drawn to the shore at the will of the fishers.

At this period, we have different authorities for supposing, that a whale-fishery was carried on near the coasts of Normandy and Flanders. We find, in the eleventh century, a donation of William the Conqueror, to the Convent of the Holy Trinity of Caen,

* "Translation et des Miracles de Sain Vaast."

† "Vie de Saint Arnould, Evêque de Soissons."

[page] 13

of the tithe of whales captured at or brought to Dive*; and in a bull of Pope Eugene III. in 1145, we find again a donation in favour of the church of Coutances, of the tithe of the tongues of whales† taken at Merry, a gift which was confirmed to this church by an act of Philip, King of France, in 1319. Though there seems nothing in the words of these acts against the idea, that the whales here spoken of were fished for in the sea, but, on the contrary, they rather convey a belief, that the Normans, familiarised in the north with these hardy enterprises, never hesitated the repetition of them in the Channel, with a superiority of means and of courage derived from experience; yet, as hitherto, there is nothing decisive as to a fishery having been actually carried on by the French, I do not feel myself competent to speak positively to the point.

* "Decimam Divaæ,—de balenis et de sale," &c. Gall. Christ. xi. instrum. 59.

† ——"Apud Merri, decimas linguarum cenarum quæ capiuntur inter Tar et Tarel fluvios, &c.—decima lignarum "crassi piscis totius rippariæ maris," &c. Gal. Christ, xi. instr. 240.-273. There are two serious errors in the text of these two charters. In the first we must read celarum, instead of cenarum; and, in the second, linguarum, instead of lgnavum, for establishing the sense, without which they will be unintelligible. These charters likewise indicate, that the people of Normandy were in the habit of eating the tongues of whales.

[page] 14

The great D'Aussy, who has given a valuable work on the private life of the French*, quotes a manuscript of the thirteenth century, where mention is made of the flesh of the whale being used for food. He also quotes a fable†, tending to prove the same point; and as he makes it appear, that the flesh, and particularly the tongue, was publicly sold in the markets of Bayonne, Cibourre, and Béariz, and that it was esteemed as a delicacy; it is presumed that it was sold in its fresh state, and that they took the whales at a little distance from the coast, in the manner practised in Normandy. In support of this opinion, it may be observed, that Edward III. King of England, had a revenue of 6l. Sterling, upon every whale taken and brought into the harbour of Béariz; which, in 1338, was so considerable, that it became the subject of petition by Peter de Puyanne, Admiral of the English fleet stationed at Bayonne, and it seems was awarded to him, in consideration of his services in the capacity of Admiral, in which he was employed‡.

* "La Vie privée des Francais."

† "Bataille de Charnage et de Carême;"—"La Vie privée," &c. vol. ii. 66. 68.

‡ Rymer's "Fædera." Tom. v. p. 46 12. Edw, III.

[page] 15

Whilst the Norwegians, Flemings, French, and probably the Spaniards of Biscay, seem to have thus early subjected to their necessities or ambition, the largest animals in the creation, the English, it is not to be expected, remained long behind. We possess, indeed, few documents, which relate to any very early attempts to capture the whale by the English; and those we have, leave us rather in doubt whether the whales therein referred to, were such as were run on shore by accident, or whales attacked and subdued upon the high sea. By an act of Edward II.* A. D. 1315, in an agreement with Yolendis de Soliere, Lady of Belino, he reserves to himself the right of all whales cast by chance upon the shore; and, by a subsequent act, (A. D. 1324.) the wreck of whales throughout the realm, or whales or great sturgeons taken in the sea, or elsewhere, within the realm, excepting certain privileged places, were to belong to the King†. Another

* Rymer's Fœedera, tom. iii. p. 514. and 515. An. 8. Edward II.

† "Item habet warectum maris per totum regnum, balenas et sturgiones captos in mari vel alibi infra regnum, exceptis quibusdam locis privilegiatis per Reges." Cotton, MS. 17. Edward II. c. 11.

[page] 16

act recorded by Dugdale*, expresses, that Henry IV. gave, in 1415, to the Church of Rochester, the tithe of whales taken along the shore of that bishoprick.

The whale-fishers of the sixteenth century, who most distinguished themselves by their habitual success in capturing those formidable creatures which constituted the objects of their pursuit, were the inhabitants of the shores of the Bay of Biscay. On the French side, the fishers of Cape Breton, of Plech or Old Boucaut, the Basques of Béariz, of Gattari, St Jean-de-Luz, of Cibourre, &c., and the Biseayans, on the side of Spain, are all understood to have been actively engaged in attacking the whales, whenever they appeared in the Bay of Biscay†; and with almost uninterrupted success. The animal, however, captured by these people, was not the great Mystieetus or common whale, but a species of Fin-whale, probably the Balæna rostrata of Linnæus, as appears both by the testimony of the Dutch‡, and by

* "Henricus rex Anglorum, Anselmo Archiepiscopo, &c. Sciatis nos dedisse S. Andreæ de Rovecestra, &c.—Et decimam Balenarum quæ captaæ fuerint in Episcopatu Rofensi."—Monas. Angl. I. 30.

† Noel, Mémoire, &c. p. 11.

‡ "Nieuwe Beschryving der Walvisvangst en Haringvisschery," vol. i.

[page] 17

the known habits of the common whale, which lias never yet been seen in the European seas, as far as I can learn, but only in or very near the regions of ice. Besides, the food of the mysticetus does not seem to occur in the necessary profusion except in the Polar Seas. The fin-whales, on the contrary, which feed in general on herrings and other white fish, find large supplies of food in most parts of the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

At first, these animals used to present themselves in the Bay of Biscay, at a certain season every year, when they were attacked by the Biscayans. At length, however, when the capture of them became a particular object of industry, and the whales were disturbed and became less abundant, with a desire also, it appears, of enjoying a more uninterrupted fishery, the Biscayans insensibly became bolder, and being good navigators, anticipated their return by pursuing them when they left the Bay, until they ultimately approached the coasts of Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland*. The Icelanders, now attracted by a prospect of a new branch of commerce, fitted out vessels, and uniting their energies with those of the Biscayans, conducted the whale-fishery on so extensive a scale, that, towards the end

B

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 1.

[page] 18

of the sixteenth century, the number of vessels annually employed by the united nations, amounted to a fleet of 50 or 60 sail*.

The first attempt by the English to capture the whale, of which we have any satisfactory account, was made in the year 1594. Different ships were fitted out for Cape Breton, at the entrance of the Gulf of St Lawrence, part of which were destined for the walrus-fishery, and the remainder for the whale-fishery. The Grace of Bristol, one of these vessels, took on board 700 or 800 whale-fins or laminæ of whalebone, which they found in the Bay of St George, where two large Biscayan fishermen had been wrecked three years before. This is the first notice I have met with of the importation of this article into Great Britain†.

However doubtful it might have appeared at one time, whether the English or the Dutch were the first discoverers of Spitzbergen, the claim of the English to the discovery and first practice of the whale-fishery on the coasts of these islands, stands undisputed‡.

* Beschryving, vol. i. p. 1.

† Hackluyt's Voyages, vol. iii. p. 241.

‡ The Dutch allow that the English preceded them to the Greenland or Spitsbergen whale-fishery, four years.—Beschryving der Walv. vol. i. p. 2.

[page] 19

Out of the several attempts which had been made to find a passage on the north of Europe or America to the East Indies, arose the Archangel trade; for the prosecution of which, the Russia Company was established under an advantageous charter. The active prosecution of this trade, and the annual fishery about the North Cape and Cherry Island, for the walrus, so inured the English to these boisterous and frigid regions, that, on the retreat of the objects of their pursuit, they extended their voyage (which had usually terminated at Cherry Island) to the northward, along the coast of Spitzbergen, where they resigned the capture of the walrus and seal, for the more important fishery of the whale.

The discovery of the Greenland whale-fishery, it therefore appears, was not a circumstance that immediately resulted from the prior discovery of Spitzbergen, but it arose out of the enterprising character of the adventurers, employed in commercial speculations at this period; which character would, most undoubtedly, have led them to follow the objects of pursuit, when they retreated to the northward, independent of the existence of these islands. Hence, whatever importance is attached to the discovery of these barren lands, the value of the discovery is eclipsed by that of the whale-fishery in the prolific seas adjacent; as it in a short time proved the most lucrative, and the most important branch

B 2

[page] 20

of national commerce, which had ever been offered to the industry of man.

The merchants of Hull, who were ever remarkable for their assiduous and enterprising spirit, fitted out ships for the whale-fishery so early as the year 1598*; which they continued regularly to prosecute on the coasts of Iceland and near the North Cape, for several years; and after the re-discovery of Spitzbergen by Hudson in 1607, they were among the first to push forward to its coasts.

Captain Jonas Poole was sent out on a voyage of discovery in the year 1610, by the "Company for the Discovery of unknown Countries," the "Muscovy Company," or the "Russia Company," as it was subsequently denominated. When unable to proceed farther to the northward, he returned to Spitzbergen, and employed himself some time in killing sea-horses, in order to reduce the expences of the voyage. Having observed a vast number of whales on the coast, he mentioned it to the company after his return, who, the next year, fitted out two ships for the fishery; the Marie Margaret of 160 tons, under the direction of Thomas Edge, factor, and the Elizabeth of 60 tons, Jonas Poole, master. Edge had six Biscayans along with him, expert at killing whales, and his ship was fur-

* Elking's View of the Greenland Trade and Whale-fishery, p. 41.

[page] 21

nished with the requisite apparatus for the fishery. About the 12th of June they killed a small whale, which yielded twelve tons of oil, being, according to Captain Edge, the first oil ever made in Greenland. Whilst they were busily engaged killing sea-horses in Foul Sound, and preparing the oil, a quantity of ice set in, whereby the ship was driven on shore and wrecked. The men being now totally destitute, the Elizabeth having parted company before this accident, took to their boats on the 15th of July, and proceeded along shore thirty or forty leagues to the southward. Two boats parted company off Horn Sound, and shortly afterwards fell in with a Hull ship, which happened to be on the coast, and gave the master intelligence, that they had left 1500l. value of goods in Foul Sound. He therefore proceeded to the place to get the goods belonging to the company, as well as to kill some morses for himself. Meanwhile, Captain Edge, with two other shallops, had put off shore in lat. 77½° for Cherry Island, and landed there with a N. W. storm on the 29th of July, after being fourteen days at sea. Here, they were so fortunate as to find the Elizabeth, just on the point of weighing anchor for England; which ship having made a bad voyage, Edge ordered her back to Foul Sound, to take on board the goods left there. They left Cherry Island on the 1st of August, and arrived in Foul Sound on the 14th, where they found the Hull ship

[page] 22

and the rest of their men. Captain Edge now ordered the cargo of the Elizabeth, consisting of seahorse hides and blubber taken at Cherry Island, of little worth, to be landed, and the oil and whale-fins procured by his own crew to be taken in. In performing this, they brought the ship so light that she upset and was lost. Captain Edge then agreed with Thomas Marmaduke, master of the Hull ship, to take in the goods saved, at the rate of 5l. per ton, which being done, they set sail homewards on the 21st of August, and arrived in Hull on the 6th of September, from whence the company's goods were shipped for London*.

This was the first instance in which the Russia Company embarked in the whale-fishery at Spitzbergen†.

Though the English had thus by rapid steps discovered and established a whale-fishery on the coasts of Spitzbergen, of vast national as well as private

* Edge's "English and Dutch Discoveries,—PURCHAS'S Pilgrimes," vol. iii. p. 467.

† Anderson, in his History of Commerce, under the year 1597, mentions, that the Russia Company now commenced the fishing for whales near Spitzbergen. It is evident, however, that the Spitzbergen fishery did not commence so early by several years; and it is probable that the voyage of Edge, in 1611, was the first of the fishery on this coast.

[page] 23

value, yet they had an opportunity of reaping but little benefit from the trade before other nations-presented themselves as competitors.

Such a novel enterprise as the capture of whales, which was rendered practical, and even easy, by the number in which they were found, and the convenience of the situations in which they occurred,—an enterprise at the same time calculated to enrich the adventurers far beyond any other branch of trade then practised—created a great agitation, and drew towards it the attention of all the commercial people of Europe. By one impulse, their mercantile spirit was directed to this new quarter, and vessels from various ports were engaged, and began to be fitted for the fishery. In the next year, however, when the Russia Company sent two ships, the Whale of 160 tons, and the Sea-Horse of 180 tons, to the fishery, three foreign ships only made their appearance. They consisted of one from Amsterdam, commanded by William Muydam, and another from Sardam, intended only, it seems, for the taking of sea-horses; and a Spanish ship from Biscay, fitted for the whale-fishery*. The English, jealous of the interference of the Dutch ships which they encountered during the voyage, (who now, as on many former occasions, followed them closely wherever there was presented a prospect of emolu-

* DE BRY'S Ind. Orientalis, tom. iii. p. 51.

[page] 24

ment*,) would not allow them to fish, but obliged them to return home, threatening to make prizes of their ships and cargoes if ever they had the presumption to appear again on the fishery†. They conceived themselves to be justifiable in this conduct, from the supposition that the discoverers of Spitzbergen, as they considered themselves, and its whale-fisheries, were entitled to all the emoluments to be derived from them. The Dutch vessels‡ which, on this occasion, were repulsed from the fishery, were piloted by a man who had been twenty years in the service of the Russia Company; and the Spanish vessel which the same year attempted the Spitzbergen fishery, was piloted by an-

* "In most of the new branches of trade discovered by the English, in the latter part of the sixteenth, and the former part of the seventeenth century, we may observe, that the Dutch followed close at their heels. This has been seen in the Russia Trade,—the N. E. and N. W. attempts for a passage to China,—in planting America,—in the circumnavigation of the globe,—and in the East India Commerce."—MACPHERSON'S Annals of Commerce, vol. ii. p. 264.

† Elking's View of the Greenland Trade and Whale-fishery, p. 41.

‡ Most authorities mention only one Dutch vessel as having sailed to Spitzbergen this year; but, as De Bry, who mentions two vessels, wrote his account in the following year, I have preferred his authority to any other.

[page] 25

other of the company's servants, and procured a full cargo in Green Harbour. Woodcock, the pilot, on his return to England, was, on the complaint of the company, imprisoned sixteen months in the Gatehouse and Tower, for conducting the Spanish ship to the fishery*. On this voyage the Russia Company's ships made no discoveries, in consequence of some quarrelling between the commanders; they, however, succeeded better in the fishery, having taken seventeen whales and some sea-horses, which produced them 180 tons of oil.

In the following year (1613), the English Russia Company having received intimation that a number of foreign ships were fitting for Spitzbergen, obtained a Royal Charter, excluding all others, both natives and foreigners, from participating in the fishery; after which they equipped seven armed vessels, under the direction of Captain Benjamin Joseph, in the Tigris of 21 guns, for the purpose of enforcing this prerogative, and monopolizing the trade.

Though the foreign adventurers were apprized of the resistance intended by the English, yet they all persisted in their object, and proceeded openly on the voyage; excepting some vessels from Biscay, which put to sea under pretence of being bound to

* Purchas's "Pilgrimes," &c. vol. iii. p. 467.

[page] 26

the West Indies, to carry out men to Lima, by order of the King of Spain; but eventually made their way to the coast of Spitzbergen. Thus, in the course of the season, there appeared in the fishing country two Amsterdam ships, furnished with twelve Biscayans, as harpooners, boat-steerers, and oil manufacturers, and two more from other ports of Holland; together with a pinnace, partly manned with English, fitted from Amsterdam, for the walrus-fishery; one ship and a pinnace also arrived from Dunkirk, one from Bourdeaux, one from Rochelle, three from St Jean de Luz, and some Spanish ships from St Sebastian. These vessels being successively discovered by the English in their various retreats, were attacked in the way they had reason to anticipate; and after the greater proportion of the blubber or oil, and whale-fins, which they had procured, was taken from them, most of them were driven out of the country. Even four English ships, fitted out by private individuals, were likewise driven away, to which, in common with the foreigners, the Russia Company's people attached the name of interlopers. Some French ships only were permitted to fish, in consideration of their paying to the English a tribute of eight whales; and one ship belonging to the same nation, which had been successful in the fishery, was allowed to retain half of the blubber it had taken, on condition of reducing the other half

[page] 27

into oil for the English, who were not so well acquainted with the process of manufacturing this article as the French. The Dutch vessel which had English seamen on board, was captured and taken to London*, together with the greater part of eighteen and a half whales, which their other ships had procured, occasioning a loss, according to their estimation, of 130,000 guilders†. The English, however, were far from being gainers by these transactions; for whilst engaged in making reprisals on their competitors, they neglected their own voyage, whereby their ships returned home 200 or 300 tons dead freight, and occasioned a loss to the company

* The Dutch, in their modern publications on the whale-fishery, are silent on the subject of this capture; as also is Captain Edge, who has given us an account of the early fishery of the English, in Purchas's Pilgrimes, &c. in which he himself was engaged. I therefore presume, that the prize, on its arrival in England, was restored to its proper owners.

† "Beschryving der Walvisvangst," &c. Deel i. p. 25., and "Ind. Orientalis," by John Theodore de Bry, A. D. 1619, where we have a full account of the transactions above referred to, in a chapter entitled "Descriptio regionis Spitzbergœ; addita simul relatione injuriarum, quas, An. 1613, alii piscatores ab Anglis perpessi sunt: et protestatione contra Anglos, qui sibi solis omne jus in istam regionem vendicarunt."—torn. iii. p. 47, 62.

[page] 28

of three to four thousand pounds*. But though the Dutch made a dreadful outcry against the proceedings of the English, we find the latter affording assistance and protection to some of the crew of a Dutch vessel who had been separated from their ship in a fog, whilst engaged, in opposition to the orders of the English Admiral, in conveying away from the land the produce of a whale they had taken†: and we also find, that while the Dutch were highly indignant at the opposition received from the English, yet they themselves assumed the same right over some Spanish vessels which entered the Sound where they lay, by prohibiting them from fishing, and forcing them to depart‡.

The Dutch, who constantly exhibited an uncommon degree of perseverance in all their commercial undertakings, were not to be diverted from participating in so lucrative a branch of commerce, without a struggle, made an attempt, in 1614, to continue the trade, notwithstanding their discouragement, on a plan so extensive, as to combine the resources of the principal cities and sea-port towns of the United Provinces. In the first instance,

* Purchas's "Pilgrimes," &c. vol. iii. p. 467.

† De Bry, tom. iii. p. 59.

‡ Idem, vol. iii. p. 58.

[page] 29

however, the plan was only got to bear in Amsterdam, where a company was established. In consideration of repeated petitions to the States-General, setting forth the great expences incurred by the merchants composing this company, in discovering the countries situated in the polar regions, and in commencing a whale-fishery therein, they obtained a charter for three years, granting them the right of all the fisheries, and other emoluments, included between Nova Zembla and Davis' Straits, and excluding all other ships of the realm from interference, under the penalty of confiscation of the ships and cargoes*.

With this encouragement, they immediately sent to Biscay for additional harpooners, to assist and instruct them in the fishery; erected boiling-houses, ware-houses, and cooperages, to be in readiness to reduce the fat into oil, in the event of a successful fishery; and, for the security of their ships, they sent along with them, four ships of war, of thirty guns each, which, together, amounted to a fleet of eighteen sail. This fleet was so formidable, that the English, notwithstanding their pretensions to an exclusive claim to the fishery, having only thirteen large ships present, and two pinnaces, though furnished with artillery, were obliged to allow the Hollanders to fish without interruption. The English got but

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 2, 3.

[page] 30

half laden, and the Dutch made but a poor fishing*.

King James seems to have entertained the same opinion with regard to the title of his subjects, to the sole occupation of the Greenland Whale-fishery; or, at least, he wished to establish such a title, since, in the course of the same year, he sent Sir Henry Wootten, his ambassador extraordinary, to treat with the Commissioners of their High Mightinesses the States-General, concerning the intrusion of the Hollanders into the English Greenland fishery, together with their interruption of our East India Commerce†.

In 1615, the Russia Company fitted out but two ships and two pinnaces for the whale-fishery, while the Dutch sent out eleven, together with three ships of war. Three Danish ships of war, piloted by one James Vaden, an Englishman, likewise appeared on the fishery, with the object of exacting tribute from the English fishermen, on the score of a supposed title, on their part, to the right of the fishery. This absurd claim was answered by the English with their usual argument of Sir Hugh Willough-

* Purchas's Pilgrimes, vol. iii. p. 467.; and Churchill's Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. i. p. 565.

† Anderson's History of Commerce, A. D. 1614; and Macpherson's Annals, vol. ii. p. 275.

[page] 31

by's prior discovery of Spitzbergen. An uncommon quantity of ice, with foggy weather, so pestered the fishers this season, that the English got entangled, and lay fourteen days beset. They returned home, as before, half laden; while the Dutch made a successful fishery*.

Captain Edge, in the Russia Company's service, had eight ships and two pinnaces under his command, in 1616. "This year," says Edge, in his account of the English and Dutch Discoveries to the North†, "it pleased God to bless their labours, and they filled all their ships, and left a surplus behind, which they could not take in." They had 1200 or 1300 tons of oil by the 14th of August; and all the ships arrived in the Thames in September in safety. The Dutch had four ships in the country, which kept together in obscure places, and made an indifferent fishing.

Fourteen sail of ships, and two pinnaces, were equipped for the fishery, by the Russia Company, in the year following. They killed 150 whales; from whence they extracted 1800 or 1900 tons of oil, besides some blubber left behind, for want of casks; and all their ships returned without accident‡.

* Purchas, vol. iii. p. 467.; and Anderson's Commerce, A. D. 1615.

† Idem.

‡ Idem.

[page] 32

The superiority of the Dutch, in point of numbers, prevented open broils in Greenland, during two or three years; but the spirit of jealousy still existed, and again burst forth. Captain Edge, who had under his direction the whole of the Greenland fleet, went on board of a Dutch ship, which he met in the country, and showing him the King's commission, ordered the captain to depart, telling him to inform his comrades, that if he met any of them on the coast, he should take from them whatever fishing they had made. Edge treated the captain courteously and then allowed him to depart, on his promising to seek two of his companions and return home; in place of which, however, meeting with a Hull fisher, he was induced to return back and commence the fishing in Horn Sound. Edge on hearing this, sent his Vice-Admiral to attack them, and take the produce of their fishing from them; but before he arrived, the Zealanders being aware of his approach, freighted two ships and sent them off, leaving one ship with some casks of blubber, and two whales and a half unflenched. The blubber was seized, together with the cannon and ammunition in the ship, to prevent reprisals on any of the English fleet, which the Zcalandcr, being well armed, threatened. This blubber, however, proved a prize of little or no value to the English, as they had already procured more blubber and fins than

[page] 33

than their ships could carry*. The cannon and some other articles were restored to the owners on the arrival of the ships in England.

The Dutch, determined, in spite of the opposition received from the English, to pursue a commerce which promised such striking personal, as well as national, advantage, in 1617, procured a renewal of their charter for four years, whereby were incorporated two or three companies, formed in different States of the United Provinces. This charter interdicted any other persons in the country from participation in the trade, under the penalty of 6000 guilders for each ship, together with the confiscation of the vessel and cargo. From the substance of this charter, it appears, that the Dutch had, prior to this period, resorted to Jan Maycn Island, for the purpose of fishing for whales†.

With a view to make the whale-fishery trade more general, King James, who had then succeeded to the throne of England, in 1618, granted a patent, whereby he embodied a number of English, Scots and Zealand adventurers. This charter, however, appearing to militate against the privileges of the Russia and East India Companies, who had been at the greatest expence in the discovery and esta-

VOL. II. C

* Purchas, vol. iii. p. 467,–8.

† Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 6

[page] 34

blishment of the fishery, was annulled, notwithstanding that shipshad been purchased, provisions contracted for, and other considerable preparations made by the different parties, for commencing the fishery. The Russia and East India Companies being therefore still allowed to monopolize the trade, with their joint stock, equipped thirteen ships and two pinnaces for the Greenland fishery.

But on this occasion the event proved most unfortunate; for the Zealanders, exasperated by the rescinding of the Scottish patent, the seizure of their oil, and other insults, appeared in the country with twenty-three well appointed ships. They placed themselves in the most frequented bays where the English fished, and setting on watch a great number of boats, prevented their success. Towards the end of July, ten sail being collected in the harbour at the Foreland, where lay two English ships and a pinnace, a division of five in number attacked them, killed a number of their men, shot away their sails, and overpowered them. They then plundered them of their cannon and ammunition, burnt their casks, and made prize of one of their ships for their indemnification. The rest of the English were dispersed, and most of them returned home empty as they were*.

* Purchas, vol. iii. p. 469.; Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 26.

[page] 35

In this conflict, it appears that the English were either overpowered by numbers, or, being discouraged by the unexpected attack, did not fight with their accustomed coolness and valour. They fired short, according to the Dutch account, and were defeated, while the Dutch had the opportunity of satisfying our countrymen, as they observed, that they were as little deficient in personal courage as in diligence and zeal, to carry on their trade. These dissensions were viewed by the Governments of the two nations, with a happy degree of moderation, though it does not appear that they took any measures to prevent the recurrence of such events. On the arrival of the Dutch fleet with their prize in Holland, the States-General presented the English captain with a remuneration, and judiciously liberated his vessel*.

The occurrence of these mortifying circumstances, together with the arrival of the vessels of other powers on the fishing stations, which tended to divide the quarrel, had the effect of producing a conference between the captains of the rival nations, for the consideration of the best method of adjusting their differences, and preventing the liability to future disturbances. The English, at this time, claimed the exclusive right to the fishery, while the Dutch and the Danes asserted an equal title.

C 2

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 20.

[page] 36

The English grounded their claim on the supposed discovery of Spitzbergen by Sir Hugh Willoughby, in the year 1553*, and on the discovery and establishment of the fishery about which they contended. The Dutch denied, and with justice, Sir Hugh Willoughby's discovery, and rested their claim on the discovery of these islands by Heemskerke, Barentz and Ryp, in the year 1596. And the Danes, supposing Spitzbergen to form part of West Greenland, which was at an early period possessed by them, asserted this as a sufficient title.

Finding the determination of this point a matter of great difficulty, while it now appeared of less importance than they had at first conceived, having found that the whole coast abounded with fine bays and commodious harbours, each of which were equally resorted to by the whales, and equally well adapted for carrying on every operation relative to the fishery, they agreed at length to a division of these bays and harbours, which were to be considered as the independent possession of those to whom they were allotted.

The English had such influence as to obtain, not only the first choice, but the privilege of occupying

* This claim of the English was fully answered by D. Peter Planei, "a very learned cosmogropher," who proved that Sir Hugh Willoughby never reached so far north as Spitzbergen. His protest against the claims and conduct of the English, is included in De Bry's "Historica Descriptio regionis Spitzbergæ," published in his Ind. Orient, tom. iii. p. 60.–62.

[page] 37

a greater number of bays or harbours than any of the rest. After the English, the Dutch, Danes. Hamburghers and Biscayans, each in succession, made a selection, in the order of their arrival on, or their supposed claim to the fishery.

The English chose for themselves some of the principal southern bays, most free from ice, consisting of Bell Sound, Preservation or Safe Harbour in Ice Sound, and Horizon Bay, the whole situated on the south of the Foreland; together with a small bay behind the northern part of the Foreland, which they called English Harbour, and another more remote which still bears the name of English or Magdalena Bay*.

The Hollanders, obliged to take up their quarters farther to the northward, chose the Island of Amsterdam, with two bays adjoining, one on each side; and a third, which they called Hollander's Bay, formed between the island and the main.

The Danes, who followed next after the Hollanders, contenting themselves with more circumscribed possessions, established themselves between the English and the Dutch. Their principal place of resort they called Danes Island and Danes Bay.

When the Hamburghers resorted to the fishery, they discovered a small bay to the northward of the Foreland, situated near the Seven Ice Bergs, which

* Histoire des Pêches, tom. i. p. 15,

[page] 38

being less encumbered with ice than many others, they took possession of for their fishing station, and named it after their native city.

Lastly, The Spaniards and French, though among the earliest visitors to Spitzbergen, found, on their arrival, in the year when the division was made, all the bays on the coast already disposed of and occupied; they therefore fixed themselves in an unclaimed situation, on the northern face of Spitzbergen.

Thus we perceive the origin of the names of the different places called English Bay and English Harbour, Hollanders Bay and Amsterdam Island, Danes Island and Danes Bay, Ham burghers Bay, Biscayners Point*, &c.

These arrangements having been adopted, the fishery was subsequently carried on with greater harmony. Each nation prosecuted the fishery exclusively in its own possession, or along the sea-coast, which was free for all. It was understood, however, that the ships of any nation might resort to any of the bays or harbours whatever, for the convenience of awaiting a favourable wind, taking refuge from a storm, or any other emergency; the prosecution of the fishery in the bays belonging to other nations, being alone prohibited. The better to secure the fulfilment of this part of the ar-

* Anderson's Commerce, A, D. 1618; also Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 5, & 26.

[page] 39

rangement, it was agreed, that whenever a boat was lowered in a strange harbour, or happened to row into the same, the harpoon was always to be removed from its rest, so as not to be in readiness for use*.

All the early adventurers on the whale-fishery, both English and others, were obliged to be indebted to the Biscayans for their superintendence and help. The office of harpooner† requiring great experience as well as personal courage, was only suited to the Biscayans, who had long been inured to the dangers and difficulties attendant on the fishery of the fin-whale. The Biscayans were likewise looked to for coopers, "skilful in setting up the staved cask." At this period, each ship carried two principals; the Commander, who was a native, was properly the navigator, as his chief charge consisted in conducting the ship to and from Greenland; the other, who was called by the Dutch Specksynder, or cutter of the fat, as his name implies, was a Biscayan, and had the unlimited controul of the people in the fishery; and indeed every operation belonging to it was entirely confided to him. When, however, the fishery

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i.

† The harpooner is the person who strikes and kills the whale.

[page] 40

became better known, the commander likewise assumed the superintendence of the fishery. The office of specksioneer, as it is called by the English, was nevertheless continued, and remains to this day, though with a more limited prerogative. The specksioneer is now considered the principal harpooner, and has the "ordering of the fat," and extracting or boiling of the oil of the whale; but he serves entirely under the direction of the commander of the vessel.

It has been observed, that the merchants of Hull were among the most enterprising of the British subjects, in equipping ships for the whale and walrus fisheries of Spitsbergen and the adjacent islands; besides which, they distinguished themselves by the discovery, on the part of the English, of Jan Mayen Island, called by them Trinity Island, and by establishing a whale-fishery there at a very early period. The Russia Company wishing to monopolize the whole of this branch of commerce, disputed the right of the Hull merchants to participate in it; and wished to debar them from visiting even this secluded island. In consequence, however, of a proper representation of the facts, King James at this time (1618) privileged the corporation of Hull with a grant of the Jan Mayen Island whale-fishery*.

*Anderson's History of Commerce, A. D. l6l8.; Macpherson's Annals, vol. ii. p. 292.

[page] 41

Though the joint speculation of the Russia and East India Companies, in the Greenland whale-fishery in 1618, proved unsuccessful, they, nevertheless, made a second trial the following season, by equipping nine ships and two pinnaces; but a boat with ten men, belonging to one of the ships, being lost, one of the ships cast away, and five failing of success, so discouraged them, that they agreed to relinquish the trade.

After this determination, four members of the Russia Company compromised with the Society, and fitted out, on their own responsibility, seven ships in the year 1620; but on account of the number of Flemings and Danes in the northern harbours where they resorted to, they were induced to remove from station to station, and were disappointed of a full lading. Their united cargoes amounted to 700 tons of oil. In 1621, the same number of vessels being sent out, succeeded rather better, having procured 1100 tons of oil; the next season they had very bad success; and in the year 1623, the last of their union, they procured 1300 tons of oil. One of their largest ships was unfortunately lost this season, and twenty of the men perished*.

In the mean time, the Dutch pursued the whale-fishery with more vigour than the English, and with still better effect. It was no un-

* Purchas, vol. iii. p. 470.

[page] 42

common thing for them to procure such vast quantities of oil, that empty ships were required to take home the superabundant produce*. Such an importance, indeed, did they attach to this speculation, that the Dutch Companies always solicited, by petition, a renewal of their charter previous to its expiration; and of such value was it deemed in a national point of view, that for a number of years they were encouraged, by the fulfilment of their wishes. In 1622, in consequence of a petition to this effect, the charter of the Amsterdam Company was renewed for twelve years, and the charter of the Zealand Society was extended about the same time, whereby the latter were allowed to establish themselves in Jan Mayen Island, and to erect boiling-houses and cooperages in common with their associates†.

The Dutch having now incorporated a considerable and opulent company, and possessing the encouragement of the Prince of Orange's commission‡, they were enabled to protect their own fishery, and to secure themselves against interruption from other nations. For which purpose, as appears

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 28.; and Churchill's Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. ii. p. 471.

† Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 7,–10.

‡ Maurice de Nassau was Prince of Orange at this time.

[page] 43

from a subsequent charter*, they erected forts and dwelling-houses in different parts of their possessions.

The privileges of these companies, furnishing them with the opportunity of aggrandizement, to the exclusion of all other persons belonging to the United Provinces, produced a considerable degree of discontent, when the fishery, towards the expiration of these last charters, was in its most flourishing state. Hence, it became the general wish of those excluded from participation, that the trade might be entirely laid open. To effect which, therefore, towards the time of the expiration of the Amsterdam and Zealand charters, the merchants of some of the other provinces petitioned the government against their renewal. These petitions having failed, the Frieslanders, who, in particular, were wishful to embark in the whale-fishery trade, made a representation to the States-General of Friesland to this effect. In consequence of which, inquiries, agreeable to their suggestions, began to be made respecting the legality of benefiting any part of the community of a republican country, to the exclusion of the rest. The result placed the legality of

* The whole of these charters I have by me, in the English and French, as well as in the original languages. I find them, however, like most law documents, so redundant, and, on the whole, so uninteresting, that I shall not encumber my pages with the translation.

[page] 44

the proceeding in a light so equivocal, at the same time that the claim of the memorialists relative to their right to participate in the fishery, was so equitable, and their arguments of the unbounded and natural freedom of the seas, so appropriate, that the States-General of Friesland were induced to grant a charter to a company formed in that province, which endowed them for twenty years with similar privileges, as those of the other companies of Holland*.

When, on the strength of this charter, the Frieslander, in the year 1634, had prepared three ships for the fishery, to prevent disturbance, and to secure themselves against future litigation, they perceived a necessity for procuring the sanction of the Zealand and Amsterdam Companies, to their right to participation. The States-General of Holland having, at their request, given a verbal acknowledgment to their charter, the two ancient companies gave instructions to the commanders of their ships to respect it also. To prevent also, as far as practicable, the possibility of unpleasant consequences, arising from the inter-

* This period of time, it seems, was reduced to eight years, on the union of the Frieslanders with the other fishing companies of Holland; so that the freedom of the fishery, for every one, was declared at their expiration in 1641,–2. Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 10,–12.

[page] 45

ference of the Frieslanders' ships with those of the other companies, in the course of the year, they contracted together and formed a triple union. The principal conditions of this union were, that the Company of Friesland, for the use of their vessels in the concern, should be entitled to all the privileges of the ancient companies, with the use of all their bays and harbours; and that they should receive one-ninth of the produce of all the ships of the united companies as their share, out of which they were to allow the Amsterdam Company 10 per cent., probably in consequence of these being the original adventurers; that the influence of each company in matters of dispute, should be in the proportion of six votes to Holland, two to Zealand, and one to Friesland; and that in case of any new discovery being made, the discoverer should be entitled to all emoluments to be derived therefrom for five years, and then it should revert to the use of the general concern*. The whole of the articles of union amounted to twenty-four, but the preceding are the most important. Though it appears, that the interests of the three companies were united in 1634, the formal contract was not completed and signed until the 23d of June 1636. The Holland

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 13,–15.

Idem, vol. i. p. 18.–20, contains the charter whereby the Zealanders, Hollanders, and Frieslanders were incorporated.

[page] 46

and Zealand Companies were the more willing to incorporate the Frieslanders along with them, from the hope, that this union would effectually prevent any other towns from joining in the trade. In this, however, they were disappointed; for, at the solicitation of different persons, it was found necessary to allow all who were in readiness within a certain limited time, to unite themselves with the concern. For the use of these additional adventurers, the ancient companies appropriated a part of their possession, lying in the South Bay on the Main, where the Haarlingers erected their boiling-house*.

While the Dutch followed the whale-fishery with perseverance and profit, they were successfully imitated by the Hamburghers and other fishermen of the Elbe, but the English made only occasional voyages. Sometimes the Russia Company sent out ships, at others, private individuals belonging to London, but more frequently the merchants of Hull embarked their property in the Spitzbergen trade.

About this period, when the fishery was chiefly pursued in the very bays where the ships lay at their moorings, it was found a matter of convenience and dispatch, to erect various buildings for the accommodation of the coopers employed in making and repairing casks, and for the seamen who were engaged in re-

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 17.

[page] 47

ducing the blubber into oil, together with suitable erections for performing this operation. The erections of the Dutch were the most considerable; but even the English, though their shipping in the trade had never been very numerous, had, we learn, several substantial buildings on the margin of Rynier's River in Bell Sound; among which, were a a cooperage firmly built of timber, and roofed with Flemish tiles, 80 feet in length and about 50 in breadth; a considerable boilers' lodging-house; and boiling furnaces with chimneys of brick*.

The adventurers in the whale-fishery, conceiving that considerable advantages might be derived, could Spitzbergen be resorted to as a permanent residence, were desirous of ascertaining the possibility of the human species subsisting throughout the winter in this inhospitable climate. The English merchants, it appears, offered considerable rewards, together with the supply of every requisite for such an undertaking, to any person who would volunteer to pass the winter on any part of Spitzbergen; but not one was found sufficiently hardy to undertake the hazardous experiment. Such, indeed, was the

* These buildings were erected originally by the "Flemings, in the time of their trading hither," as appears from Pelham's "Miraculous Preservation and Deliverance of Eight Englishmen, left by mischance in Greenland 1630," published in Churchill's Collection, vol. iv. p. 750.; and a verbatim copy in "Clarke's Naufragia," vol. ii. p. l63,–206.

[page] 48

terror with which the enterprise was viewed, that certain criminals preferred to sacrifice their lives to the laws, rather than pass a year in Spitzbergen. The Russia Company, it is said, procured the reprieve of some culprits who were convicted of capital offences, to whom they not only promised pardon, but likewise a pecuniary remuneration, on the condition that they would remain during a single year in Spitzbergen. The fear of immediate death induced them to comply; but when they were carried out and shown the desolate, frozen, and frightful country they were to inhabit, they shrunk back with horror, and solicited to be returned home to suffer death, in preference to encountering such appalling dangers. To this request, the captain who had them in charge humanely complied; and on their return to England, the company interceded on their behalf and procured their pardon*.

Probably it was about the same time, that nine men, who were by accident separated from one of the London fishing ships, were left behind in Spitzbergen: all of them perished in the course of the winter, and their bodies were found on the ensuing summer, shockingly mangled by beasts of prey. The same master who abandoned these poor wretches to so miserable a fate, was obliged, by the drifting

*Pelham's Narrative.

[page] 49

of the ice towards the shore, to leave eight of his crew who were engaged in hunting rein-deer for provision for the passage home, in the year 1630. These men, like the former, were abandoned to their fate; for, on their proceeding to the usual places of resort and rendezvous, they perceived with horror, that their own, together with all the other fishing ships, had departed. By means of the provisions procured by hunting, the fritters of the whale left in boiling the blubber, and the accidental supplies of bears, foxes, seals and sea-horses, together with a judicious application of the buildings which were erected in Bell Sound, where they took up their abode, they were enabled not only to support life, but even to maintain their health little impaired, until the arrival of the fleet the following year*.

The preservation of these men, revived in the Dutch the desire of establishing permanent colonies, and confirmed them in the idea of the possibility of effecting this desideratum. It was, however necessary that other trials should be made, before the project could be carried into execution.

In consequence, therefore, of certain encouragements proclaimed in general throughout the fleet, seven men volunteered their services, were landed

VOL. II. D

* Pelham's Narrative in Churchill's Collection, vol. iv. and Clarke's Naufragia, vol. ii. p. 179.

[page] 50

at Amsterdam Island*, furnished with the needful articles of provisions, clothing, spirits, fuel, &c., and were left by the fleet on the 30th of August l633†. About the same time, another party, likewise consisting of seven volunteers, were landed in Jan Mayen Island, and left by their comrades, to endure the like painful service with the former. On the return of the fleet in the succeeding year, this last party were all found dead‡, from the effects of the scurvy; but the other which was left in Spitzbergen, nine degrees further towards the north, though they suffered exceedingly from their privations and unusual hardships, all survived§. Encouraged by this partial success, for it appears that the melancholy result of the experiment at Jan Mayen was as yet unknown to the Spitzbergen fishermen, it was proposed that another party should repeat the experiment in the ensuing winter. Accordingly, other seven volunteers were landed as before, supplied with every supposed necessary, and quitted by their comrades, on the 11th of September 1634. Before the close of the month of November, the scurvy made its appear-

* Amsterdam Island lies on the N. W. of Spitzbergen, in lat. 77° 44′ N. long. 9° 51′ E.

† Churchill's Collection, vol. ii. p. 413.

‡ Idem, vol. ii. 415,–425.

§ Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. ii. p. 26,–31.

[page] 51

ance among these devoted people, and by the beginning of March, had, by its dreadful ravages, destroyed the whole party*. The names of each of the fourteen men who suffered in the two trials, are perpetuated; but of the names of those who successfully encountered the severities of the arctic winter, I have not met with any notice. Neither does it appear what were the encouragements which stimulated those hardy adventurers to undertake the hazardous enterprise, though it is very evident the inducements must have been considerable.

In the year 1635, the Russia Company was endowed by Charles the First, with the exclusive right of importing the oil and fins of whales. This indulgence was merely a confirmation of the proclamation of the 17th of James the First, with the restriction, that the fishery should be prosecuted by this company in its joint stock capacity only†.

The bold and unconscious manner in which the whales resorted to the bays and sea-coasts at this period, their easy and expeditious destruction, the consequent regularly productive state of the fishery, together with the immense herds in which the whales appeared, in comparison of the number

D 2

* Churchill, vol. ii. 427,–8.; and Anderson's Commerce, A. D. 1634; also, Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. ii. p. 31.

† Anderson's Commerce, A. D. 1635.

[page] 52

which was killed,—encouraged the hope that the profitable nature of the fishery would continue unabated. This consideration induced the enterprising Dutch to incur very great expences in making secure, ample and permanent erections, which they gradually extended in such a degree, that at length they assumed the form of a respectable village, to which, in reference to the use that it was designed for, they gave the name of Smeerenberg.*

The result did not, however, justify the sanguine expectations of the Greenland Companies; for the fishery, as it soon appeared, had already attained its acme†, and began to decline so rapidly from the year 1636–7, to the termination of the companies charters, that their losses are stated, on some occasions, as having exceeded their former profits‡. To the system of extravagance which they had adopted, with the vast expence which they incurred in the the construction of buildings, in a region where most of the materials had to be imported, is attributed the subsequent failure of the Dutch chartered companies.

Towards the expiration of the charters of the united Dutch Greenland Companies in the year 1642.

* Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 27,–28. The word Smeerenberg is probably derived from the Dutch words smeer signifying fat, and bergen, to put up.

† Forster's Discoveries in the North, p. 426.

‡ Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol. i. p. 29.

[page] 53

their renewal was attempted by the interested parties; but in consequence of the people of Overyssel, Utrecht, Guelderland and others, having, by their representatives, most strenuously resisted the measure, and petitioned for liberty to embark in the whale-fishery trade; their High Mightinesses the States-General conceived that the renewal of the charters would not only give general dissatisfaction, but would likewise be inimical to the commercial interests of the United Provinces, and therefore caused the trade to be laid entirely open to all adventurers*. This determination produced an effect so happy, that in a short time the trade was increased almost tenfold. The number of ships annually sent out by the chartered companies, would appear to have only amounted to about thirty, while, on the dissolution of the monopoly, the influx of shipping into the whale-fishery commerce was so great, that in a few years they accumulated to between two and three hundred sail†.

* Beschryving, vol. i. p. 21.

† De Witt, in his "Interest of Holland," mentions that the Greenland Whale-fishing trade increased ten-fold, on the dissolution of the monopolizing companies. Now, as the Frieslanders, who fitted three ships, were considered as forming one-ninth part of the united companies, the fleet of the whole would probably amount to about twenty-seven sail, to which, adding the Haarlingers, and other additional adventurers, we may consider the Dutch Greenland Fishery, during the latter years of the monopoly, as employing at least thirty vessels, If De Witt be correct, therefore, a ten-fold increase will make the fleet in subsequent years to have increased to three hundred sail. And, as these ships were double manned, they must have carried about sixty men each, which, multiplied by 300, the number of vessels employed, gives the total of their crews, 18,000 men! Lieven Van Aitzina, quoted by De Witt, indeed says, That the Dutch Whale-fishery employed upwards of 12,000 men, at the same time that the English did not send a single ship, which was about the period referred to. It is therefore probable, that the above estimate may not be very wide of the truth. See Macpherson, vol. ii. p. 290.; and Beschryving der Walvisvangst, vol, i. p. 28.