[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[frontispiece]

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page i]

TRAVELS

IN

SOUTH AMERICA.

VOL. I.

[page ii]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY C. ROWORTH, BELL YARD,

TEMPLE DAR.

[page iii]

TRAVELS

IN

SOUTH AMERICA,

DURING THE YEARS 1819-20-21

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE PRESENT STATE

OF

BRAZIL, BUENOS AYRES, AND CHILE.

BY ALEXANDER CALDCLEUGH, ESQ.

TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

MDCCCXXV.

T.

[page iv]

[page v]

PREFACE.

IT would only be to follow the example of every writer on South American affairs, since the earliest accounts of Ovalle and Acosta, to state, as a reason for intruding these Travels on the public, the very general interest which is excited with regard to this portion of the New World: an interest, which, if it formerly prevailed, when the country was more imperfectly known, and beyond the reach of foreign commercial adventure, exists at the present moment with redoubled force, owing to this

[page] vi

great field being thrown open to British enterprize by revolutionary changes and the adoption of a liberal and enlightened policy.

The Author has endeavoured to collect every fact which relates to the government, the resources and the prospects of the countries which he visited; and he trusts he has drawn an impartial sketch of every thing which came under his notice.

He gladly avails himself of this opportunity of expressing his sense of the obligations he is under to many excellent friends with whom he became acquainted during his residence in South America—men as much distinguished by their intelligence in public affairs, as by their kindness and hospitality in private life. He cannot refrain from more particularly mentioning the names of Alexander Cunningham, Esq. H. M. Commissioner of Arbitration, and

[page] vii

James Watson, Esq., both of Rio de Janeiro; also that of G. F. Dickson, Esq., late of Buenos Ayres, but now residing in Liverpool; of John Watson, Esq. of Buenos Ayres; and of J. Lawson, Esq., of St. Jago de Chile.

The Engravings are executed by Finden, from drawings made by Mr. W. Daniel, a gentleman well known to all lovers of the fine arts. Many of the sketches were executed by Captain the Hon. William Waldegrave, for whose kindness the Author is happy to make this public acknowledgment.

[page break]

[page viii]

[page break]

[page ix]

CONTENTS

OF

VOLUME I.

CHAPTER I.

Departure from England.—Madeira.—Experiment on the Line —Arrival at Rio de Janeiro.—The Bay and its Defences.—The City and Public Building Page 1

CHAPTER II.

Climate.—Thermometer, Barometer, Hygrometer.—Diseases.—Soil.—Fruits, Bananas, Oranges, Fruit of the Passion Flower.—Vegetables.—Coffee, Cocoa.—Tea Plant introduced from China.—Botanical Garden.—Timber for various purposes.—Animal Kingdom, Cattle, Dogs, Tapir, Sloth.— Birds, Humming Birds, Anum.—Reptiles, Snakes and Toads.—Insects, Spiders, Ants, Cochineal Insect.—Fish, Garupa.—The Geological Formation, Organic Remains. 15

CHAPTER III.

Agriculture, Maize, Mandioca, Sugar and Coffee.—Manufactures.—Trade.—Diamonds, Gold and Precious Stones.— Bank of Brazil, Legal Interest.—Value of Land.—Community, State of Society, Amusements and Mode of Life, Marriages and Funerals.—Language, State of Literature.— Public Libraries, Museum, State of the Medical Art.—Religious Feelings and Institution, Superstitions, National Character. 49

VOL. I. b

[page x]

CHAPTER IV.

Population, Indians.—The Negro Race, Numbers and Treatment, Emancipation, Native Tribes.—Emigration, Swiss Colony.— Constitution, Support of the Clergy, Finances, Military and Naval Force.—Political Changes and Prospects 78

CHAPTER V.

Departure for Buenos Ayres.—Maldonado, Pampero.—Montevideo.—Rio de la Plata, Geological Formation.—Political Changes.—The cis-Platine Province forms a Part of Brazil. —Paraguay,—its Dictator.—Yerba, or Tea Tree.—Bonpland, —System of the Dictator.—Arrival at, and Appearance of Buenos Ayres 118

CHAPTER VI.

Province of Buenos Ayres.—Its Boundaries and Extent.—Climate.— Diseases.— Rivera.— Minerals.— Meteoric Iron.— Salt.—Botany.—Animals and Birds.—Bones of the Megatherium.—Agriculture, Cattle, Manufactures, Trade, Paraguay Tea.—Internal Commerce and Degree of Prosperity. 141

CHAPTER VII.

Individual Comfort, Food, Dress and Houses.—Social Happiness, Theatre and Tertulias.—Particular Customs, Language, University.—Public Library, Publications.—Dean Funes.— Gazettes.—influence of Religion.—Manners of the Inhabitants.—Shades of Difference in the Provinces.—Population, Indians, Slaves.—Executive and Legislative Powers.—Rivadavia and Garcia.—Religious Institutions and Administration of Justice. 168

[page] xi

CHAPTER VIII.

Revenue.—Public Debt, Internal and External Security.—Attacks of the Indians.—Alliances.—Summary of Events from the year 1810 to the present time. 197

CHAPTER IX.

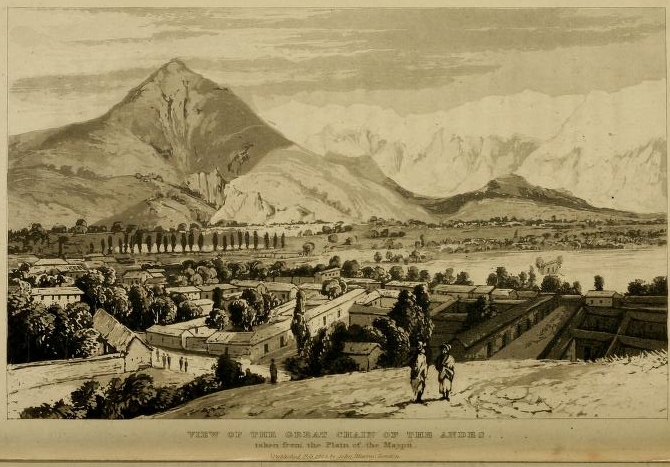

Departure from Buenos Ayres.—Diary of the Journey across the Pampas on Horseback.—Pass the Arroyo de en Medio into the Province of Santa Fé.—Enter the Province of Cordova.—Fall in with the Indians.—Escape from them.—Pursued into the Sierra de Cordova.—Arrive in safety at Estansuela.—Punta de San Luiz.—Salt Lake.—First View of the Great Chain of the Andes.—Arrival at Mendoza. 235

CHAPTER X.

Mendoza.—San Martin.—Passes in the Cordillera.—Dp rture to the Southward.—Cross the River of Mendoza.—Reach the Entrance of the Pass of the Portillo.—Ascent.—Descent to the Valley of Los Punquenos.—Snow Storm.—Confined two days under a large fragment of rock.—Ascend the Second Pass of Lot Punquenos.—Reach the Valley.—Arrive at the first Chilian Habitations.—Mill for the Grinding and Amalgamation of Silver Ores.—Arrival at Santiago, the Capital 285

CHAPTER XI.

Extent of Modern Chile.—A portion of it included in the ancient Empire of Peru.—First March of the Spaniards, under Almagro, most disastrous.—Valdivia marches into the Country of the Araucanos, defeated and killed.—The Araucanos unconquered to this day.—The Climate, Soil, Sea Coast, Rivers, Lakes.—Island of Juan Fernandez 323

[page] xii

CHAPTER XII.

State of Chilian Agriculture.—Botanical Observations,—Mines, Gold, Silver, and Copper.—Coal.—Internal and External Trade.—Individual and Social Happiness.—Language and Mental Enjoyments.—Public Library.—Visit to the Library of the Augustine Monastery.—Influence of Religion.—Morals and Manners.—Provincialism.—Population. 347

INDEX TO THE PLATES.

FIRST VOLUME.

| The Walking Costume of Lime | Frontispiece. |

| View of Botafogo Bay | page 12 |

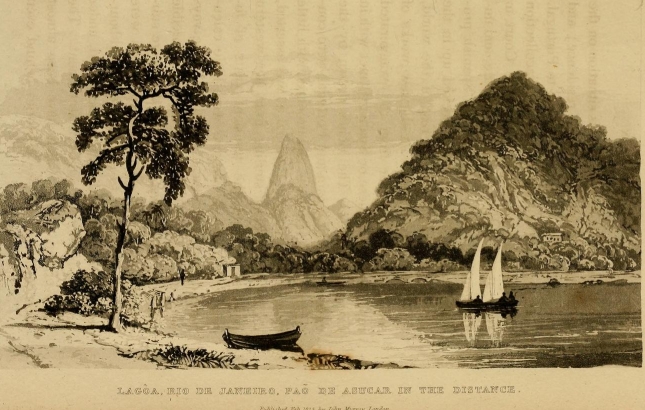

| View of the Lagoa do Freitas | 104 |

| View of the Great Chain of the Andes | 319 |

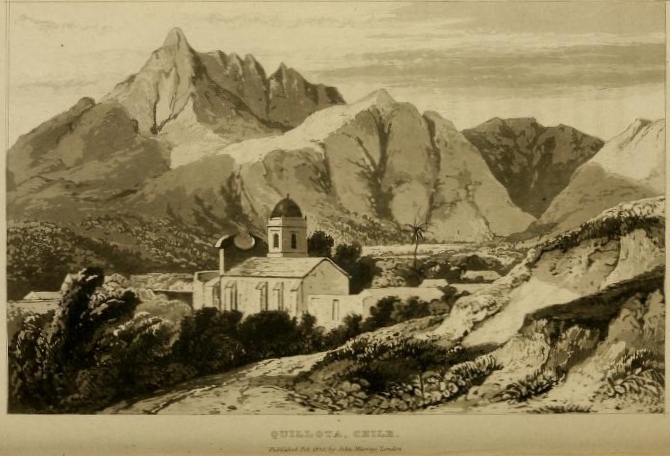

| View of Quillota | 343 |

SECOND VOLUME.

| Crossing the Cordillera on the 1st June. Frontispiece. | |

| View of Valparaiso Bay | page 45 |

| View of Lima from the Sea | 77 |

| View of Lima with the Bridge over the Rimac | 96 |

[page] 1

TRAVELS

IN

SOUTH AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

Departure from England—Madeira—Experiment on the Line —Arrival at Rio de Janeiro—The Bay and its Defences— The City and Public Buildings.

HIS Majesty's ship SUPERB, with a small squadron under the command of Commodore Sir Thomas Hardy, Bart., having been got ready for sea, and the Right Honourable Edward Thornton, Minister at the court of Rio de Janeiro, of whose suite I formed a part, taking his passage on board, we embarked at Plymouth on the 9th September, and were soon carried by a favourable wind across the Bay of Biscay. All my former voyages had merely extended to trips across the Channel in small packets, attended by every sort of inconvenience and unpleasant sensations; but the

VOL. I. B

[page] 2

motion of a ship of the line is so regular and steady, that I escaped the usual introduction to a voyage, seasickness, although the coal-tar with which the timbers of ships are now injected, however effectual against dry-rot, and far from proving unhealthy to the crew, was not very agreeable to the senses.

We arrived in Funchal Roads, Madeira, on the 18th, and stood on and off without coming to an anchor. The island, as it appeared from the ship's deck, for no one went on shore, was extremely picturesque. The town, with the high hills in the back ground, and white houses and convents appearing through the foliage, presented a very prepossessing landscape, and one, I should imagine, seldom if ever forgotten by those quitting the colder regions of the north. It forms the step, the half-way house from Europe to the tropics, and unites in itself many of the advantages of both. It has been remarked that to quit Madeira with a favourable impression, it should be seen only at a distance; for, on landing, the dirtiness of the town and the apparent wretchedness of the inhabitants soon dispel all pleasing illusions.

Leaving this beautiful island the following morning, the ships directed their course nearly south, and soon fell in with the islands of

[page] 3

Palma and Teneriffe, the celebrated Peak remaining in sight on the 21st and 22d, at the distance of a hundred miles.

When the Superb reached 4° north latitude, it was determined by the Commodore to try for soundings with an unusually long line. The weather was very nearly, although not quite, calm, and the line (whale line) was laid out in such a way as to meet with no obstacle in its descent. The weight of about six hundred pounds was attached to the rope, consisting of four pigs of ballast, two deep sea-leads, a registering thermometer, and some other articles. At first the line ran out with considerable velocity, but afterwards sluggishly; and when two thousand fathoms were expended it was determined to recall it. After the rope that had sunk from its own weight was drawn up, the pressure of the water was so great that it required almost the whole strength of the ship to bring it in. The tar ouzed from it in abundance. When about one fourth of the line was recovered, it gave way, and in an instant every thing was lost, to the great disappointment of all those on board, who imagined that, with a sufficiency of line, a bottom might be found. About fifteen hundred fathoms were down perpendicularly; and it was not a little mortifying that, in a

B 2

[page] 4

spot where the approximation of the two continents was greatest, and where soundings would have proved most interesting, this experiment should have failed. To insure success in sounding at considerable depths, some other contrivance than the common sea-lead and line must be used. Perhaps some box of a peculiar construction, charged with a weight, which should unload itself either on reaching the bottom or when the line shall be drawing up, might be made to answer the purpose. A line increasing in thickness as it is lowered into the water has also been suggested.*

We crossed the equator in 23½° W. long on the 11th October, when the usual ceremonies were performed, under proper restrictions. The heat was not so oppressive as it had been, or perhaps we had become accustomed to it, the thermometer rarely exceeding 81°, and the water at the surface a little under that temperature.† The south-east trade carried the squadron to 18° S., where the variable winds again prevailed. Shortly afterwards we

* It appears from the experiments of Captains Sabine and Wauchope, in the Caribbean Sea, that the greatest density of the ocean exists at 1300 fathoms: the temperature being 42° of Fahrenheit.

† Appendix, No. I.

[page] 5

crossed the sun's course, and every person on board went below to see the perpendicular rays in a midshipman's chest in the cockpit, a locality seldom visited by that great luminary.

In lat. 22° we experienced a severe gale of wind, with lightning and water-spouts, which lasted for some hours. After the storm subsided, the ships' decks and rigging were covered with numbers of the most beautiful butterflies and moths, blown from the shore, which at the period was distant upwards of a hundred miles.

On the morning of the 22d October, we made the coast of Brazil, distant about fifteen leagues, bearing north-west, very mountainous, and supposed to be Cape St. Tomé.* In the evening we saw Cape Frio, distant five leagues, and the following morning came in sight of the harbour of Rio de Janeiro. The mouth is so extremely contracted, and the nature of the high surrounding land such, that it reflects no small degree of credit on the man who, at such an early period, discovered the existence of an

* In the Corogratia Brasilica, there is a very interesting letter written by one of the officers who accompanied the discoverer, Cabral. The original was discovered in the archives of the Admiralty al Rio de Janeiro. Mr. Southey has given the substance of it in the first volume of the second edition of his very learned and excellent history.

[page] 6

inlet.* The squadron remained lying on and off until the sea breeze sprung up, when it entered the magnificent harbour, and, to the great delight, it was said, of His Most Faithful Majesty, the three ships saluted at the same moment, and moored in eighteen fathoms, after a delightful voyage of only forty-five days.

Very few, I should imagine, have entered Rio de Janeiro without attempting to describe the beauties of the harbour and surrounding country, and certainly few have been successful in their descriptions. After the failure of so many writers, it would be in me presumption to attempt it. The direction of the harbour is about north and south; and on the left or west side of the entrance is the Sugar Loaf (a conical hill so called), and on the opposite the fortress of Santa Cruz. The mountains on either hand are of inconsiderable height, cone shaped, and, for the most part, clothed to their summits with trees and shrubs. There are various small islands covered with luxuriant vegetation scattered about the bay; and in the distance a range of mountains of fantastic forms, called the Organ Mountains, runs across from east to west, and

* When first discovered it went by the name of Nitherohy, which means, in the Indian language, hidden water: hy, water, and nithero, hidden or concealed.

[page] 7

terminates the view. From the large harbour, which stretches more than twenty miles into the country, several small bays extend for some distance, and present various points of view of great beauty. This bay has been compared to that of Naples, although of a character totally different; but it far surpassed any idea I had formed of it.

The vast importance of the harbour has been so fully and frequently acknowledged that little remains to be noticed on that head. The tide rises between four and five feet, and at times there is a very considerable surf. There are traces to show that the sea has, if any thing, receded from this part of the coast. The few rivers running into the bay are of little note.*

The defences of the harbour are numerous. The fort of Santa Cruz, with others opposite to it, defend the entrance; and that of the island of Cobras the city. There are no docks either for the building or the repair of ships; but they might be constructed without all the difficulty that some persons have imagined. At the back of the island of Cobras every convenience is found for those repairs which can be

* Appendix, No. II.

[page] 8

accomplished without the aid of regular slips; and the spot where Captain Cook hove down is yet pointed out. In this place lie also the remains of that navy which in former days accomplished so much. It requires but a short period in a tropical country, where every description of insect and lichen is more vigorous, to destroy ships of the firmest construction, and by far the greater number of these struggled across the Atlantic either at the period of or shortly after the king's arrival, and have been laid up ever since. Considering the quantity of excellent building materials abounding in the country, little upon the whole has been done; and Portugal, at some time or other, may deeply regret the sluggish apathy that has permitted the almost entire decay of her navy. At Bahia, some degrees to the northward, a few vessels have been built on slips, and among them one small frigate; another was constructed near the settlement of Goa; these are the only vessels completed of late years by the Portuguese, to repair the rapid destruction of the others. Among the hulks, the galleon taken by Lord Anson and sold to the Portuguese, is yet visible.

The city of Rio de Janeiro is built on the west side of the bay, about three miles from

[page] 9

the entrance, between two eminences, one covered with the convent of the Benedictine on the north, and the other with the remains of the Jesuits College on the south. It extends westerly to a low marsh connected with the sea, and navigable at high water. The streets are in general straight, but narrow and confined. The squares are by no means numerous, and, as the houses are not regularly built, there is nothing to admire in them. The Palace, facing the landing place, is neither handsome nor convenient; and, excepting the addition of the convent of the Carmelites, it remains the same as when it was inhabited by a Viceroy. The interior, either for apartments or furniture, is little worthy of remark. Adjoining is the Royal Chapel, on which all the skill of natives and foreigners has been lavished, and not in vain. There are three or four churches of an Italian style of architecture, such as San Francisco de Paula and the Candelaria, particularly neat. The convents, either for men or women, are not very numerous. The monastery of the rich order of the Benedictins is well worthy of a visit: the chapel is imposing, but dark from luxuriance of ornament. The Carmelites now occupy the former college of the Lapa, and the old college of the Jesuits has become a

[page] 10

military hospital. The convent of the Portuguese saint, San Antonio, who until lately held the rank of Lieutenant-General in the service, his pay and allowances being regularly drawn by the monks of his order, is built on an eminence, and from its terrace a very excellent idea may be formed of the extent and direction of the capital. The convent of the nuns of Santa Teresa stands on an eminence behind the town, and forms a pretty object from the bay. The other convent, which has served as a temporary burying place for the Royal Family, is in the Rua da Ajuda, and is far from being an ugly building. The theatre of St. John, in part supported by an annual lottery, is built in the square called the Rocio, and both externally and internally is well decorated. Behind it is the Mint and Treasury, a large building generally visited by strangers, to see the process of cutting and polishing a certain proportion of the diamonds which come down the country, the larger quantity being sent to Europe in the rough state. The Museum, in the Campo San Anna, may be also classed among the public buildings. One of the streets is filled with the warehouses for slaves, where the unhappy negro is prepared for sale. It is crowded with planters and

[page] 11

merchants, soon after the arrival of any slave ship. There are several fountains in different parts of the town, with police officers attending to preserve order. They are supplied for the most part by an aqueduct of many arches, extending from near the summit of the Corcovado, the highest peak round the bay, being by barometrical measurement upwards of 2100 English feet.*

The houses in the city are built either of stone brought from the numerous quarries in the immediate neighbourhood, or of brick work plastered with shell lime. The rooms are generally large, with little furniture, and that, in most cases, of the commonest description. The houses in the vicinity of Rio de Janeiro, upon which all the skill of the architect has been expended, are mostly surrounded by verandas, which contribute much to their coolness. The Exchange, a neat building, was opened in 1820. The pavement of the streets is very indifferent;

* This water has had various opinions passed on it. Captain Cook seemed to think it did not keep well at sea, while many officers have subsequently spoken favourably of it. On the other hand, on board the Owen Glendower, the ship in which I returned home, various complaints were made of it. I am inclined to think the fault has rested with the tank in which it was brought off to the ship.

[page] 12

and the roads, extending only a short distance round the town, are purposely kept soft to spare the feet of the blacks.

The country palace of his Majesty, where he most constantly resides, is at the village of St. Christovem, about four English miles from the city. On the arrival of the King it was the residence of a merchant, who shortly after made a present of it to the Royal Family. It is surrounded by a veranda, and commands a fine view of the upper part of the harbour. The Queen's country residence was a very small cottage at Catete, on the south of the capital. This is justly considered the most beautiful side of Rio, and is therefore thickly studded with the country seats of the more opulent citizens. Botafogo is also justly admired for the beauty of the scenery. This village stretches along the shore of a small, but most romantic bay of the same name.

The markets in Rio de Janeiro present little worthy of note. The fish market, indeed, is distinguished for the great variety exposed, caught principally, if not entirely, within the harbour. Fruit is sold in every corner and square. The meat shambles are very properly confined to particular spots. The public garden, some years ago so much frequented, and

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 13

consequently kept in excellent order, is now much neglected and fast going to decay. From its terrace there is a very pretty view of the entrance of the harbour, and, on the right, of the hill called the Gloria, with a church on the summit, and several houses mostly occupied by Englishmen. On the left is the eminence called Boa Viagem, also crowned with a church, where, in old times, the sailor paid his last devotions before he embarked on a distant voyage.

On the opposite side of the bay, immediately in front of the city, and to which many boats are constantly passing, are situate the village and district of Praya Grande. Many excellent houses are built here, but this side of the bay is not so much esteemed as the other.

Proceeding up the harbour, the island of Governador, where the King had a seat, is universally admired; and nearer again to the city, the spot granted to the English for a burying ground presents a beautiful point of view.

It may be remarked, in concluding this brief account of Rio de Janeiro and its neighbourhood, that the eye en every side discovers the most majestic scenery, covered with all the luxuriance of a tropical vegetation; and how-

[page] 14

ever soured the European may sometimes be with the want of comfort, or the heat, yet he will generally acknowledge, that this spot has not been surpassed, if equalled, by any other that has fallen under his observation.

[page] 15

CHAPTER II.

Climate—Thermometer, Barometer, Hygrometer—Diseases —Soil—Fruits, Bananas Oranges, Fruit of the Passion Flower—Vegetables—Coffee, Cocoa.—Tea Plant introduced from China—Botanical Garden—Timber for various purposes —Animal Kingdom, Cattle, Dogs, Tapir, Sloth.—Birds, Humming Birds, Anum—Reptiles, Snakes and Toads— Insects, Spiders, Ants, Cochineal Insect—Fish, Garupa— The Geological Formation, Organic Remains.

As the prevailing winds in this part of the world are from the eastward, they arrive tolerably cooled down on the Brazil coast; for while, on the African shore, the heat is oppressive, the parallel latitudes on the opposite side of the Atlantic enjoy a moderate degree of temperature. This tendency to easterly winds receives, however, very regular modifications from the sun's progress in the ecliptic, a monsoon setting down the coast from September to April, and in the contrary direction the other half of the year. The voyage from Rio de Janeiro to the northern provinces becomes, therefore, regular and expeditious for one portion of the year, while in the other, a very considerable offing must be made.

[page] 16

A regular land and sea breeze prevails at Rio de Janeiro, and its value can only be appreciated by those who have resided in a tropical country. The land breeze begins late in the evening, frequently only about daylight, and prevails until eight or nine o'clock in the morning, when it ceases, and in a short time the sea breeze commences and blows until sunset. This is generally the case, but the regularity of the breezes is much modified by the season. In summer time, during the great heat, after the cessation of the land breeze, every one is panting and looking out for the arrival of the other. The doors closing with violence, is often the first intimation of its approach, and in a moment every thing draws a new life. On the other hand, during the cooler period of the year, the breezes seem to be more acted upon by disturbing causes.

The summer commences in the month of October and lasts until March or April. This is also the wet season, and the heaviness of the rains can only be imagined by those who have been in such latitudes. They are by no means continuous as in some other climates, but commence generally every afternoon with a thunder storm. The regularity of these afternoon storms was such, that formerly, it is said,

[page] 17

in forming parties of pleasure, it was usual to arrange whether they should take place before or after the storm. Doming this period of the year the nights are dark, and little or no deposition of dew takes place. The warmest month is February, when the barometer stands about 86° or 88° Fahrt. and, if at this period, the order of nature is so far inverted, as to allow the land breeze to prevail all day, an event which, fortunately seldom happens, the thermometer rises proportionably. On one occasion, when the land breeze continued until four o'clock in the afternoon, the air was intolerably oppressive, and resembled the hot wind of India. At five o'clock the storm began, and an immediate fall took place in the thermometer, which soon after daylight the next morning when it was registered stood thus, highest 120°, lowest 56°, a difference of 84°. During summer the inhabitants preserve a low temperature in the house by opening the windows for an hour or two at daylight, and then closing the shutters the rest of the day.

The winter months are May, June, July, and August, when little or no rain falls. The usual height of the thermometer is 67° or 68°, a heat insufficient in this climate for vegetation. The nights are beautifully clear, and the deposition

VOL. I. C

[page] 18

of dew therefore abundant. The mean annual height of the thermometer is about 73½° of Fahrenheit.

The barometer upon Sir H. Englefield's construction is very sensibly affected; the mean height is about 30.275. It seemed to stand highest between nine and eleven o'clock in the morning. Previous to any of the gusts from the S. W., supposed to be connected with the pamperos, or violent winds of the river Plate, the barometer always experienced a very considerable depression.

The moisture contained in the air is very abundant during the summer months. At that period unfortunately, I had no means of ascertaining the exact quantity, not being possessed of one of Mr. Daniell's hygrometers; but I have no doubt that the air is very nearly at the point of saturation. During the winter I was enabled to make a few experiments with Mr. Daniell's beautiful instrument. The mean quantity of vapour in the month of August, was 5.774 gr. in the cubic foot,* a quantity at the driest period of the year, nearly double that of the mean of two in England.†

* Quarterly Journal of Science, vol xiv. p. 4.

† The mean of two years in England, ending with the summer of 1821, gave 3. 652 gr. in the cubic foot. See Quarterly Journal of Science, vol. xii. p. 97.

[page] 19

The soil is mostly of a light brown colour, in many spots of a deep red cast, and clayey. By washing this last description, the children are in the habit of obtaining a small quantity of gold. In many cases the soil seems to be owing more to decomposition of rock, than any alluvial deposit; crystals of feldspar in a decomposing state are found regularly embedded in the soil, which contains, in addition, a large portion of mica.

The effects of the climate and soil of this part of Brazil, without being particularly favourable to longevity, are certainly far from proving destructive to human life. While most tropical countries have their peculiar diseases, this can scarcely be said to possess any. Where there exists in the system any tendency to diseases of the lives, all warm countries must be more or less prejudicial, and some cases of this nature have occurred at Rio de Janeiro, and terminated fatally with such rapidity, that suspicions of poison were entertained, but the European, even with strong biliary symptoms, continues the same life of luxury as before, regardless of repeated warnings. Diseases of the skin are very common, and to them the negro race seems peculiarly liable. Frequently the, objects basking in, the sun, are, from elephantiasis and other

C 2

[page] 20

diseases of that nature, of a most loathsome and disgusting appearance. These, with two or three other maladies, however unpleasant and unsightly, but not in general terminating fatally, comprise most of those that are commonly met with. Some deaths occur from the carelessness of Europeans in exposing themselves to the vertical rays of the sun: but two or three instances of Europeans living in a constant state of inebriety, and exposed to the chilling damps at night and the burning heat of the day, and leading this life for years, are a satisfactory proof of the general healthiness of the climate.

At any rate it can be no longer doubtful which is the healthier climate, Brazil or the United States. The latter, in spite of the cleared state of the country, and the frosts of winter, which might be supposed to destroy the seeds as well as arrest the progress of contagion, are annually visited by a fever of the most destructive and cruel nature—one that physicians are not decided whether it is imported or indigenous, but which, without confining itself to the foreigner, has rendered some parts of country more dangerous to the inhabitants, than when it was first visited by Raleigh. I imagine besides, that the state of

[page] 21

cleanliness is far greater in the United States than in any of the possessions of the Portuguese, who have been at no time distinguished for their love of this virtue.

The land in the immediate neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro is laid out in the cultivation of fruits and vegetables for the supply of the capital, and it may not be uninteresting to examine whether they present any thing different to those met with in other tropical countries.

The fruit that must stand first from its vast importance in the country as an article of food, is the banana or plantain. Of this there appears to me to be two varieties cultivated at Rio, one considerably larger and coarser than the other, which is small and sweet. This tree, propagated by offsets and of an extremely rapid growth, appeared to thrive well in both the lower and higher situations round the town. The banana bears in a few months after being planted, and the fruit is gathered when immature. The quantity of nutriment it possesses must be very considerable, for runway blacks are known to support themselves during months on a single banana daily. By the Brazilians it is considered so favourable to the increase of population, that the rich planters surround their

[page] 22

estates with banana trees, and permit their slaves to eat at discretion. The trees seldom prove deficient in quantity, and are the most valuable gift of a beneficent Providence to this country. Little or no cultivation is required, their large and thick leaves fall to the root, and afford moisture and manure to the native stock; all that is necessary is to loosen the earth round the trees. It often afforded subject for discussion, whether the banana was indigenous in Brazil or introduced by the Portuguese. Baron Humboldt, who throws an interest over all he treats, thinks some confusion may have arisen from the terms plantain and banana having been used indiscriminately; and after discussing the question and examining the testimonies that go to the point, concludes by saying that no doubt can exist that the banana was grown in America before the arrival of Europeans.* Mr. Brown, whose authority upon these subjects is of the first order, without entering into the question whether the banana was indigenous in America or not, observes that it is generally considered of Indian origin, but differs with M. de Humboldt in the idea that any confusion of terms has arisen. He

* Essai Politique, tom. iii. p. 22.

[page] 23

adds, that Margrave and Piso, in their Natural History, consider the plantain and banana as introduced plants; the former from Congo.* On the other hand, Robertson,† whose indefatigable research and industry in every thing he undertook, is so well known, after a careful examination of Gumilla, Acosta, and other naturalists, considers the opinion of the plant being of American origin to be better founded. After the lapse of a few years in any country, indeed, but more particularly in one where vegetation is rapid, such is the power possessed by vegetables of adapting themselves to the climate, that it becomes not an easy matter to shew whether they were indigenous or introduced. It was, therefore, a very happy idea in the botanical writers of the Mercurio Peruano, a work published in Lima, to give from time to time lists of the various plants introduced into the country, a proceeding that must prove of infinite service to succeeding researches in Peru. A very intelligent Portuguese, who had resided much among the Puri Indians on the Rio Preto at a very considerable distance from any Portuguese settlement, and whom I became acquainted with at Villa Rica, informed me that,

* Botanical Appendix to Tuckey's Congo.

† Note 56, vol. i. Quarto Edition of Dr. Robertson's History of America.

[page] 24

in his excursions, he had met with the small banana, sweeter and better, he added, than those cultivated near Rio de Janeiro. He informed me also, that this fruit had served for food to the Puris from the earliest times. It may be added, that the banana is little cultivated by the Portuguese in the interior of the country; indeed, it would be hopeless to attempt it, as they, for the sake of mining, have chosen high and mountainous situations, where the thermometer is too low. The Indians, on the other hand, seek for low, warm and thickly wooded spots, where plenty of game may be found; thus the different pursuits of the Indigenes and their conquerors led them to seek situations widely separate; and it becomes, therefore, less likely that the former should have cultivated any of the fruits introduced by the latter. Nothing could prove more disastrous to Brazil than any deficiency in the crops, or misfortune to this most useful plant.

The next fruit, for the fineness of which Brazil has some reason to boast, is the orange. Of these there are several varieties cultivated, but those most esteemed are the selecta and the tangerinha. The former is large, with a broad leaf, while the latter is small, with the leaf scarcely larger than that of the myrtle, and, as resembling the Mandarin orange of China, would

[page] 25

be suspected of having been introduced from that country, rather than from Africa, which its name would import. About April this fruit comes to perfection, and is certainly far superior to any met with in Europe. The consumption is very great, and from districts round the city, hundreds of blacks proceed to market every morning with as many as they can carry on their heads. It is one of the most lucrative farms that can be laid out. The inhabitants are particularly partial to this fruit in the morning, when they say it is oro (gold), at noon prata (silver), and at night chumbo (lead). There can be no doubt that the finer varieties of the orange were introduced by the conquerors either from the Canaries, or the Western Islands; but the laranja da terra, a small bitter kind, discovered at a considerable distance from habitations, is thought by the Portuguese to be indigenous.

No doubt whatever exists respecting the pine-apple, which is extremely abundant for a short period of the year. In general the flavour is inferior to those raised by artificial heat in Europe, which may be accounted for in part by the necessity that exists, of cutting them the moment they give out the odour, as they are immediately attacked by ants; and in a short time nothing but the skin is left.

[page] 26

The maracuja, the fruit of the passion flower, or grenadilla of the Spaniards, is by many thought superior to all the other fruits of this garden of the world. The passiflora, with large scarlet flowers and green edges, produces the finest fruit, which is always cool and grateful to the palate.

The mango, introduced from Asia, is uncertain in its produce, and seldom of high flavour. The fruta do conde, or custard-apple, and the guava, and tamarind, are very abundant, and well known; as well as an infinity of other fruits, such as the cashew, the cocoa-nut, growing as near the sea as possible, the grumichama (myrtus lucida), the pitanga, a small red fruit, the jamba, or rose-apple, the jambuticaba, and many others, more or less admired by Europeans. Melons, and water-melons, the latter more eaten by Brazilians than by foreigners, are in great plenty. The country about Rio is too warm for either grapes or figs. The latter seem particularly subject to the attacks of a large worm, that enters the heart of the wood, and renders the knife necessary. In the mountains of the Estrella, at the head of the Bay, many of the fruits of colder climates are cultivated with success.

With the exception of the more common vegetables, such as cabbages, yams, and sweet

[page] 27

potatoes, few others are cultivated by the inhabitants. Every other kind known in Europe, has been brought to perfection by various English residents, and that with a rapidity scarcely credible. The common garden pea has been sown, flowered, gathered and the haulms removed within the short space of one-and-twenty days

The mandioca, or cassava of the West Indies (jatropha manihot), is extensively cultivated. The consumption of the flour for the support of the negroes and lower classes of Brazilians, is very large. The species, the juice of which is not of an acrid nature, is scarcely cultivated, being considered less productive than the other. This invaluable plant is too well known to require either a further description or any account of the method in use to convert it into bread. A most excellent vegetable is furnished by the head of a variety of palm, called in the country palmita; the outer leaves being removed, it is dressed in a variety of ways, and generally esteemed. The potatoes imported from England in the packets, and indeed by every conveyance, become sweet on cultivation in the warm spots near the city.

The coffee tree, now one of the principal objects of care in Brazil, was introduced more than eighty years ago, under the Vice Royalty

[page] 28

of the Conde de Bobadilla, has multiplied prodigiously, and become a great source of wealth. The Portuguese do not take the same pains to keep the plant low, as is practised in some other countries. At the end of three years, it is calculated that each plant produces three quarters of a pound of coffee, worth about nine-pence per pound, and at maturity, about three pounds. The grain is large, and much resembles that brought from the East Indies, and is freed from its husk by pounding in a large wooden mortar.

The cocoa tea (theobroma cocao) grows in great abundance in every garden. Tobacco and cotton are not cultivated near the capital, but the latter is frequently planted as a pretty flowering shrub. The indigo plant also is little attended to. The rice is grown at a short distance from the capital, and has been known to produce five hundred for one; but whether this is the mountain rice, or merely the common variety which finds in-Brazil a sufficiency of moisture in the air without the irrigation requisite in other countries, I am not sufficiently a botanist to decide.

The sugar plantations are at some distance from the capital. The two varieties most in repute are the Criolho and the Cajan, (Cayenne;) the latter, yielding a larger portion of juice, is preferred for converting into spirits,

[page] 29

while the former is made into sugar. The Otaheitan cane, considered to be the best kind, is as yet a stranger to Brazil.

As considerable misrepresentations have gone abroad respecting the tea plant introduced into Brazil, it may not be improper to point out the extent to which it has been cultivated, and the hopes entertained of it. The Conde de Barca, (Araujo,) who died during his ministry, in 1817, anxious that Brazil should possess every thing within itself, procured the Bohea tea plant, and a number of Chinese to cultivate it, from Canton. It was planted in the botanical garden near the Lagoa de Freitas, three leagues from the city, and covers a few roods of ground. It produces an abundance of seeds, but not that luxuriance of leaf or bushy appearance which it is described by travellers to possess in China; the leaves have been collected and dried in ovens, but the infusion was far from agreeable, and the cultivators, concluding that time and close packing were necessary to render them desirable, seem to have now abandoned the project. Some of the Chinese are yet seen about, and the plant is still cultivated in the garden, but certainly has not extended itself beyond it. Since the tea plant seldom flourishes farther from the line than 30° S. lat. and is also found in the province

[page] 30

of Yunnan, situate within the tropics, there can be no reason why the latitude of Rio de Janeiro 22° S. should not be equally favourable. The soil also appears to be very similar to that of the southern provinces of China; but it would seem that the great difficulty consists in choosing the periods for collecting the leaves, and in the proper management of them afterwards.

In this botanical garden, the various spices of the East, the jack, the bread-fruit, and some others not indigenous to Brazil, are collected. It is to be lamented, that the many undescribed plants of the country have not been placed here in addition to the others. Many scientific foreigners, in their way to the East Indies, fly to this establishment and only find those which they will so shortly see in all the luxuriance of their native soil, while the indigenous productions are concealed in thick forests, or at a distance from the capital, where they cannot proceed from the shortness of their stay.

Every description of timber that can be required for ship-building, dying, or domestic purposes, is to be found in this neighbourhood. The Brazil wood (casalpinia echinata) is of very inferior quality to that collected in the northern provinces, so much so, that in spite of the high price of the article is Europe, it has been

[page] 31

scarcely considered worth exporting. The jacarandà, a species of inga, without the smell but in other respects similar to the rosewood of India, and a wood yet more beautiful, called in the country, Gonzalo-Alves, dispute pre-eminence among those suited for ornamental cabinet work. The pao d' alho, or garlic tree, among the most singular.

On every side the most beautiful flowers attract the attention. Varieties of bignonias, passifloras, and a thousand others, either selecting warm exposed situations, or the cooler retreats of the woods, are constantly presenting objects for admiration. Few exist at the same time, but an unceasing variety prevails through the whole year. The general character is surprising magnificence, with little or none of that accompanying sweetness which the inhabitant of a cold country finds more or less in all flowers. Many of them, and the roses in particular, meet with a fatal enemy in the ant.

I have thus run over a portion of the vegetable riches of this part of Brazil, and if I should have succeeded in drawing the attention of English botanists to this country, which has hitherto been unaccountably neglected, I shall consider myself fortunate. Two English gentlemen of acknowledged talent, connected with His

[page] 32

Majesty's garden at Kew, remained a short time in Brazil some years ago, and in that short time gave ample proofs of their own industry and of the extraordinary riches of the soil. Since the arrival of the Princess Royal, many German scientific travellers* have made vast collections of every kind of natural history, and the learned those who have already returned to Europe. That these gentlemen have collected with ardour is well known, and their published works will sufficiently prove it, but still the field is wide, and much no doubt remains to fee accomplished. The neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro is considered by botanists to present the greatest variety of plants; and those naturalists who are anxious to leave the coast, where from evident causes the tropical vegetation extends farther south than in the interior, are in the end much disappointed. It was gratifying when in company with a botanist, to hear him exclaim at every step, "this is a new variety," or "a new plant." The vegetable stores indeed form the greatest attraction to the man of science. The mineralogist will find little in the neigh-

* Messrs. Spix and Martius, Drs. Pohl and Scllows. The Fray Leandro, professor of botany at Rio de Janeiro, is indefatigable in his researches.

[page] 33

bourhood of Rio de Janeiro; while the botanist, constantly occupied, will have some difficulty in persuading himself that new plants do not spring up every day under his feet. While in Europe man must labour hard to make the unkindly earth produce; in this country, he must toil incessantly to restrain the vegetation which would otherwise overrun him with its luxuriance.

Turing from this subject, the next inquiry will relate to the productions of the animal kingdom. It may be remarked that little exists worthy of notice among the larger species, while the lower race are more numerous and deserving attention.

The breed of horses in Brazil is small, and capable of little fatigue; they are mostly bred in the colder province of the Mines, and their strength declines the moment they descend the Organ Mountains. The best horses are imported from the river Plate, but they often arrive injured and out of condition.

Mules are bred in great abundance for the most part at Rio Grande, to the southward of the capital, and are found to answer better for carriages. They are broken in by great violence, and are seldom entirely freed from the

VOL. I. D

[page] 34

vices peculiar to the animal. A stranger at first imagines that he has been duped, and alone possesses bad cattle; but after a short residence in the country, the frequent disputes between the mules and their drivers convince him that his neighbours experience the same fortune as himself. The usual food of these animals is Indian corn, and a coarse succulent grass, originally from Africa, called capim de Angola, which in the winter months is dear and even scarce. Before the introduction of this grass, cattle were fed on that of the country, capim mellado, or honied grass, so called from the leaves being covered with a clammy juice.

Black cattle, for the consumption of the city, are brought from a considerable distance, through a country containing little pasture, and they arrive and are killed in a weak heated condition. Some are driven from the plains of Santa Cruz to the southward of the capital. The common breed is not much larger than the Scotch; but that Brazil can raise fine cattle is sufficiently proved, by the remarkably large oxen seen in the carts used for carrying stone. These carts produce a peculiar noise, which, however gratifying to the oxen and efficacious in keeping off evil spirits, never becomes agree-

[page] 35

able to human ears. Similar to the ass in Europe, the cow only gives milk is this climate with the young by her side.

It is almost superfluous to mention, that horses and black cattle were originally brought from Europe at an early period after the discovery. Beef is of very inferior quality, from the distance of the pastures, the warmth of the climate, and from its being, to a certain extent, a government monopoly. Mutton is comparatively scarce, from the surrounding country being covered with thick woods.

A very ugly breed of dogs is more numerous than agreeable to foreigners, The Portuguese, whether in Rio de Janeiro or in Lisbon, seldom destroy Mc puppies, but allow them to run wild and live on the public. A constant warfare is kept up between the negroes and these animals. There have been, however, no instance of hydrophobia known. Condamine, it is said, was the first who observed that this dreadful malady was unknown in South Americo, and it may be accounted for, perhaps, by these animals being left to the care of nature, and not tormented by the cruel process of worming, which, by depriving the animal of one of the salivary ducts, may contribute to this disease.

D 2

[page] 36

The city and its environs are infested to a surprising degree by a. large variety of rat. Many of the first houses are so full of them, that during dinner it is by no means en unusual circumstance to see them playing about the room. The canine race appear quite regardless of them, and they are often seen feeding at the same heap of garbage. Their dental powers are such that a thick clumsy door of hard wood is frequently perforated in one night. Officers of ships are obliged to use every precaution to prevent this destructive animal from getting a footing on board.

The largest animal known in Brazil is the tapir or antar, the grande bestia of the Spaniards. It is by no means so large, nor of the same colour as the species met with in the East Indies. It is too well known to require a description.

The sloth is very common. It confines its depredations to one tree, called by the Brazilians sumambaia, which it never quits while there is a leaf remaining. When completely leafless the animal drops down, and is only driven by hunger to discover another. It would seem as if nature had determined that it should not procure its sustenance without some

[page] 37

difficulty, for the sumambaia is high, with leaves only at the extremity of the branches, which are at the very summit of the tree.

The armadillo serves as an article of food; the meat is white and well tasted.

The jaguar or South American tiger, seldom approaches the haunts of man. In August, 1820, however, two of them came to Praya Grande, and carried off some cattle, but were subsequently destroyed, and found to be of considerable size. There are no instances on record of their attacking the human species. At St. Paul's, ten days journey south-west of Rio de Janeiro, the jaguar frequently attacks cattle. As soon as he make his appearance the herd arranges itself in a circle, the horses with their hoofs, and the cattle with their horns presented to the enemy, the colts and calves placed in the centre, and await him in this posture. The jaguar watches his opportunity, springs in the midst, seizes one of the calves, and in a moment disperses the rest.

A species of pig is sometimes brought down from the interior which has a gland on its back, from which a fetid smell issues, and if not removed immediately after the animal is killed renders the meat useless.

The morcego, or bat, is extremely numerous.

[page] 38

One species, the andara guassu of the Brazilians, is of large dimensions, and lives on the blood of cattle. Whether the story be correct, that it cools the air with its wings, and keeps its prey quiet while it is sucking the blood, I will not pretend to decide, but I could never discover that the mule or horse had made any resistance. The wound was almost always on the neck, of a minute size, and, contrary to what is usually the case in Brazil, soon healed. It did not seem that this kind of bleeding is at all detrimental.

The birds of Brazil have been at all times more distinguished for their numbers, and the brilliancy of their plumage, than for their powers of song. In the neighbourhood of the city few are met with but such as live on cultivated fruits. The beija flores, or humming birds, varying considerably in appearance, are met with in great abundance in the gardens when the orange trees are in flower. The splendid metallic lustre of their plumage, their minute size, the smallness of the feet, and their fly-like habits never fail to attract the attention of foreigners. It has been generally supposed that they live on the nectar of plants, but their long beak, it is now believed, merely seizes the insects attracted to the nectarium. Many

[page] 39

attempts have been made to domesticate this beautiful bird, but hitherto without success.

The anum, very similar to, but smaller than, the blackbird of England, flies about in large coveys. It appears to live very much in communities, many nests being found united together.

The jacu (penelope) may be termed, from the delicacy of its flesh, the pheasant of Brazil; it is not unlike a hen turkey, but rather smaller.

It is said there are upwards of twenty varieties of parrot found in Brazil, but few are seen near Rio de Janeiro, Excepting the small green paroquet and the magnificent arara.

The jacutinga, a very excellent bird for the table, is about the size of a small turkey. The plumage is black, with some white about the wings and breast. It would prove very uninteresting to the common reader to enumerate the birds met with in this part of Brazil.

In this climate, it may easily be imagined, that the number of reptiles is very considerable. The rattle-snake does not exist near this part of the coast, but in the province of the Mines it proves very destructive to negroes. At Saint João del Rey, a young man went into the woods, was bitten on the instep by a rattle-

[page] 40

snake, came home ill and died. His widow (time being very precious with the fair sex in Brazil) soon married again, and her second availed himself of the clothes of the first, and among other things put on a pair of boots. He was shortly afterwards taken ill and died. A third husband followed and experienced the same fate. Another Brazilian, little alarmed by what had happened, and induced, perhaps, by the accumulation of wealth, became the fourth husband, and by chance discovered the fang of a rattle-snake sticking through the instep of the boot, which being worn by his predecessors, been without doubt the cause of their deaths.

The cobra de coral, or coral snake, abounds in every garden. It is small and spotted with scarlet and dark green. It is generally considered poisonous; but I examined many individuals without discovering, in any instance, the teeth that are looked upon as the marks of a venomous reptile.

The jararáca is sometimes five or six feet in length, of considerable thickness, and tapers a little towards the tail. This is one of the most common and venomous snakes met with. There

[page] 41

are many other varieties of snakes, of all colours, and most of them in all probability viviparous.

Toads of very unusual size, and one that makes a noise similar to that issuing from a stone mason's shop, and frogs of large dimensions, and small green ones living in trees, are of common occurrence. The scolopendra, or centipede, is often seen in houses, sometimes seven or eight inches long, and proportionably thick. The scorpion of Rio de Janeiro is white, and. almost innocuous.

The spider reaches an enormous size, with different habits from those of Europe. It stretches its web from tree to tree, and no longer appears a solitary insect: many hundreds live together and from nets of such strength, that I have assisted in liberating a bird of the size of swallow, quote exhausted with struggling, and ready to fall a prey to its indefatigable enemy.

It was always said by the Portuguese, that the ant was the inhabitant of Brazil, and it must be confessed there is some truth in the satire: they exist of all sizes and colours, and them, that they have nearly fallen in. At Saint Paul's, there is a variety so large, that fried it

[page] 42

forms a food by no means contemptible in the eyes of the inhabitants; and, however minute, they contribute much towards repressing a too rapid increase amongst reptiles much larger than themselves. Many winged insects, on touching the ground, become its prey. On one occasion a spider of the largest size had fallen from a tree, and was attacked by millions of a small brown ant: in his attempts to get free he crushed and destroyed many, but still some managed to get on his feet, and crawling up to his thighs, remained quiet; by these means, his progress impeded, and perfectly exhausted and overcome by numbers, he soon became their Victim, and in a short time few traces of his existence was visible. The carcase of any animal placed in the woods is rendered a perfect skeleton by these insects; and the many stories related of their powers in removing large substances are completely borne out.

The termites, or white ant so destructive in the East Indies, is not less so in South America. The mode used to destroy them is a little singular, that of turning the antipathy of the races to good account. As soon as they are observed, a little sugar in put down, which in a moment summons a tribe of brown or black ants, who instantly attack and destroy the ter-

[page] 43

mites, to the great amusement of the blacks who witness the defeat of the white insect. Scarcely any article of food, fruit or flower, can be protected from them.

The mosquito of South America has been so often celebrated that little remains to be said about it. Their humming noise adds not a little to the annoyance, and the bite of a town mosquito is, with some persons, attended with much inconvenience, and the philosophy of a new comer is a good deal put to the test. Another trouble: the jigger, a small insect which conceals itself under the toe nails, requires great attention, and the streets show every day examples of victims to a disregard of its attacks, which often extend to the legs and hands. The negro race seem more conversant with, and are generally employed to extirpate, this insect, which was probably introduced by themselves from the coast of Africa. It forms, like a cold in England, a common excuse for absenting oneself from a party.

The tick is confined in Europe to sheep and dogs; but in Brazil, under the name of carapato, it is a most annoying insect to man. It frequents the low brushwood, and insinuating itself into the most recondite parts of the body, and putting its head under the cuticle, grows

[page] 44

of considerable size, and requires great care in the eradication, for if any portion is left, a sore is produced. Tobacco water is one of the best applications. These are the chief plagues of the country, and it must be confessed lay under contribution the patience and good temper of the European.

To turn the subject from these disgusting insects to something more agreeable, it may be stated that some of the most beautiful butterflies are natives of this country. The large deep blue butterfly is seen in great numbers in the shaded situations round the city, and nothing can be more striking than the variety of form and colour exhibited. The collections which are occasionally made up for sale are got from the Island of St. Catharine, a short distance to the southward.

It is said that there are five species of bees in Brazil, but little honey is secured. The ant is without doubt the destroyer of the comb. The moribundo or wasp leaves a wound which takes some time to heal.

The cochineal insect, which was formerly bred to some extent in the neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, is now very nearly abandoned. It was probably the cochineal silvestre much adulterated. It is now scarcely known in the

[page] 45

London market. The insect was conveyed to the East Indies from Rio de Janeiro in 1795, by Captain Nelson; but what is imported from Madras is so different in appearance to that of Vera Cruz, that doubts are entertained whether it is an insect at all.

The varieties of beetles, grasshoppers, and every description of insect, are far beyond enumeration. The silk worm is not cultivated; but an insect which produces a cocoon, has been lately met with, and the discoverer advertised lessons in the mode of preparing the silk. The diamond or Brazil beetle (curculio imperialis), and the different varieties of firefly, are too well known to require description. The days in Brazil are tolerably quiet, but the moment night sets in, the confused din of a thousand different insects and reptiles forms a distinguishing character of the country; these lower branches of the creation, it must be confessed, appearing to thrive better than any other.

The tables are well supplied with fish. The garupa, considered similar to the rock fish of North America, is one of the best. Turtle is occasionally brought in. Formerly there was a whale fishery establishment in the bay, but it has been removed to St. Catharine's, that fish having left this part of the coast. Sharks are

[page] 46

often seen in the bay, and the rivers abound in a small species of crocodile or caiman, which seldom attacks man.

The geological formation round the bay presents little variety. It is essentially composed of gneiss of variety. It is essentially composed of gneiss of various kinds, frequently of a porphyritic structure, intersected by granite veins, and full of garnets. The only foreign beds I observed were of clayironstone, and greenstone, neither of which were of considerable extent. The numerous quarries round the city afforded excellent opportunities for examining the structure of the rocks. The metals and simple minerals met with in the rocks are comparatively trifling.

The jewellers' shops in the Rua dos Ourives are full of the products of the mines; amethysts, generally of inferior colour, and topazes of different tints, are most usually offered for sale. Green tourmaline, aqua marines, and crisolites (cimophane), are also to be purchased; but in most cases they may be bought cheaper and better either in London or Paris. The dealers are extremely ignorant of precious stones, and imagine every thing a foreigner admires must be valuable. The sale of the diamond in its native state is strictly forbidden, but there is little difficulty in procuring it. So large

[page] 47

a value of this stone is contained in little compass, that the dread of being sent to Angola for life has little effect in putting a stop to the contraband. It is not easy, therefore, on this account, to ascertain the quantity that arrives annually from the mines; but I believe the number of oitavas of 18 carats deposited in the treasury has never exceeded 3,000 or 4,000, a proportion of the stones probably reaching four or five carats. The quantity brought down clandestinely may be estimated at nearly as much more. Among the diamonds shown me in the government coffers was a thin narrow fragment, measuring six and half inches long, and weighing fifty-three carats. It must have formed part of an enormous stone. The price being according to its weight, and the form precluding the possibility of cutting to advantage, it had remained in the treasury for many years. The whitest stones were selected for the king, and the remainder sold for exportation to London and Amsterdam.

By a careful examination of the bags of topazes in the lapidaries' shops, a specimen or two of that still rare mineral the euclase may be picked up. It is known by the name of pivete by the jewellers, and is thrown aside as useless. It is found in topaz mines; and it is

[page] 48

more than probable that the first specimens brought to Europe by Dombey were procured here, and not in Peru, according to the hitherto received opinion. In Lima I could never discover that this mineral was known there.

It may not be in this place improper to mention the organic remains of a large animal found near the Rio das Contas, in the province of Bahia, while some workmen were employed in making a tank for cattle. The bones covered a space of seventy feet. The ribs were thirteen inches wide; the shin bones were five feet long, the tusks six; and a molar tooth, without the root, weighed four pounds. To move the jawbone the strength of four men was required. The whole was in a very decomposed state. In all probability when the western sides of the range which runs down the centre of Brazil is cleared and the earth turned up, many discoveries of a similar nature will be made. But none of the present race of geologists are likely to see that day.

[page] 49

CHAPTER III.

Agriculture, Maize, Mandioca, Sugar and Coffee—Manufactures—Trade—Diamonds, Gold and Precious Stones—Bank of Brazil, legal Interest—Value of Land—Community, State of Society, Amusements and mode of Life, Marriages and Funerals—Language, State of Literature—Public Libraries, Museum, State of the Medical Art—Religious Feelings and Institutions, Superstitions, National Character.

THE mode of agriculture followed in Brazil, as far as I had an opportunity of judging, is extremely simple. Some trees and underwood are felled in the first instance, and allowed to remain a few days to dry. Waiting then for a favourable opportunity, when the wind shall blow from the desired quarter, the dry wood is ignited, and the ground cleared to the extent required.

If the wood is virgin, that is, never disturbed before, the flight of reptiles, birds and insects from the conflagration is an object of surprise and dread to those engaged in the undertaking. Many hundreds of a large bird, called seriema, (the cariama of naturalists,) unawed by the explosions caused by the bursting of the bamboos, follow the progress of the flames and feed on

VOL. I. E

[page] 50

the scorched insects. The appearance of the land, after the flames have subsided, is singular. The fire passes too rapidly to consume the trunks of the larger trees, which remain scattered over the waste, standing like dismal monuments of the vegetable grandeur which so lately pervaded the spot. No trouble is exerted to remove them: in one season, unprotected by leaves or bark, they soon mingle with the soil.

The ground being now very rancid, or as it is called by the Portuguese bravo, is only suited to the cultivation of maize, or Indian corn, which becomes the first crop. The operation of burning is scarcely finished, before the rains take place, and the sowing of the maize is commenced. The harvest often yields a hundred and twenty for one. The quantity of Indian corn cultivated near the city is comparatively small, mandioca taking its place as a first crop. The maize flour is the principal article of subsistence in the interior, where, from the elevation of the country,* the mandioca flourishes with difficulty. The variety, which is devoid of the acrid juice, and called sweet aypé, is little cultivated. The other, and common kind, requires. Eighteen

* Perhaps in this latitude, the line of mandioca would be about 1800 hundred feet above the sea.

[page] 51

months' cultivation before it comes to maturity, when the roots are taken up, rasped, carefully deprived of the poisonous juice by heavy weights, and then dried by means of fire in large shallow pans. The flour prepared from this root, termed, farinha de pao, is left untouched by every description of insect, in itself no small recommendation, and forms the food of the lower classes. Before the arrival of the court, and the consequent introduction of certain luxuries, the farinha de pao was thrown on the dinner tables of the higher classes for each to help himself. From the earliest times it served for the food of the indigenes, and it shows more than any thing else, perhaps, that the means of subsistence were extremely limited, or otherwise a root, which must at first have proved fatal, would have been quickly abandoned.

The sugar cane is also one of the early crops. The variety mostly in request is termed criolho, and in some parts it is a very common and efficacious plan to have alternate crops of mandioca and cane; keeping, by this means, the ground in excellent order, without the assistance of irrigation or manure: The whole apparatus of the sugar house is humble. None of those large machines which embellish our West India islands are met with. The work is carried on by

E 2

[page] 52

day only, and much, therefore, of that severity said to prevail in our possessions is avoided. The largest portion of the sugar is clayed.

The coffee plantations are now considered the most lucrative of any, and some foreigners have dedicated themselves to the cultivation of it with considerable success.

No wheat, barley, or oats grow in the district of Rio de Janeiro; but there is a species of cytisus (cajan) which affords another means of subsistence, and is held in considerable estimation.

The articles of food raised in Brazil fall short of the consumption. Most of the northern provinces are occupied in the produce of various colonial articles, and it becomes cheaper to import than to take off the negroes to raise their own aliment. The quantity deficient is not much; the principal part of the population supporting themselves on little, and that the produce of the country; but wheat must be imported from the southern province of Rio Grande,—from the United States, in the form of flour,—from the river Plate,—and, occasionally, from the Cape of Good Hope. The southern provinces, and the ci-devant Spanish possessions, send large quantities of dried meat, which is carried on mules to the most distant

[page] 53

provinces of Brazil. It cannot be considered at articles of life are dear in the capital.

The manufactures in this part of Brazil are scarcely worthy of notice. Some very coarse cottons, and hammocks, and some articles of saddlery come down from the interior. From the province of the mines, cheese and bacon are received.

The colonial system, which was strictly per-served until the arrival of the court, kept the country in a state of ignorance of many of those beautiful articles of English manufacture, now so greedily purchased by all. The Brazil trade the British, as if an exclusive monopoly existed in their favour. By the commercial treaty of 1810, a treaty abused on all sides, and consequently supposed to be very equitable, British goods are admitted at a duty of fifteen per cent ad valorem, while those of other nations pay twenty-four. But I am assured that even if this difference did not exist, even if our manufactures paid a more considerable duty than any other, they would still command the market. They could always be furnished at a, cheaper rate, which, in a new country with a slave population, is, after all, the main object. Brazil takes from us every thing it requires, excepting

[page] 54

wine from Portugal; and the importance of this trade to England may be well conceived, when it is mentioned, that, after the East and West Indies, and the United States, it forms the greatest mart for our fabrics, and one that is rapidly increasing.

In 1820, the exports of British manufacture amounted to £1,860,000; in 1821 to £2,230,000. The imports of 1820 were £950,000; in 1821, £1,300,000, showing a great and progressive increase.

Of the amount of exports, about three-fifths are sent to the capital, owing to the greater consumption, and from its being in communication with the mines, the most inhabited districts of the interior.

The returns for this large sum are made in diamonds and precious stones, gold, coffee, cotton, sugar, tobacco brought from a considerable distance inland, some drugs and dye woods. The larger proportion of returns is made from the northern parts of Bahea, Pernambuco, and Maranham, as produce is there, from a variety of circumstances, much cheaper than at Rio de Janeiro. In sugar alone, the difference is often twenty-five per cent. in favour of the northern markets.

The other nations trading to Brazil exhibit a

[page] 55

poor figure after Great Britain. By far the most active of them, the United States, exported to Brazil only to the amount of £320,000, chiefly in flour, fish, and minor articles. It is impossible to say what may happen, but at present it does not appear that England has much to fear in this quarter. The immense command of capital which our merchants possess, strikes all foreigners with astonishment, and forces them to abandon all idea of competition. The trade carried on by the rest of the world amounts, in the aggregate, to little: that of France being chiefly confined to articles of dress and mode; and of Sweden, to a few ship loads of iron annually.

The trade expressly confined to Brazilian vessels is the coasting and African. This latter traffic, it is well known, is now restricted, by treaty, to that part of Africa south of the line, which comprehends, in fact, almost the whole of the Portuguese possessions. The importation of negroes varies in amount; but of late years it cannot be estimated on an average at less than 21,000 into Rio de Janeiro only.* It affords too great a return of gain to be easily abandoned, more especially when, strange to say, patriotic feelings are considered, in this instance, to go

* Appendix, No. 3.

[page] 56

hand in hand with profit, and when it is imagined that the moment the trade is prohibited, the prosperity of the country must decay. When it is considered that this number is annually received into the capital, and that there are three other ports trading to the same extent, and that scarcely two-thirds of the negroes taken from the coast live to be landed, the number of negroes carried away by this outlet only, in the course of the year, appears prodigious.

Many years since a considerable capital was employed in the whale-fishery. The black whale was extremely common near the mouth of the harbour, but an increasing traffic has driven this animal to the southward, and the only establishments at present are in the province of St. Catharine's. It forms another of the royal monopolies, and, in 1820, it was farmed out to some Frenchmen.

The other trade carried on in Brazilian bottoms is very much confined to that with the mother country; its dependencies, as Madeira and its possessions in Africa and the east. The traffic with China is still continued, but no longer in that way which made Portugal at one time the envy of all maritime nations.

The internal trade is very much confined to the products of the district of the mines, and is carried

[page] 57

on by means of large troops of mules, some of which, from the western provinces of Gozaz and Matto Grosso, are four months on the journey. It is not easy to learn with accuracy the produce of the diamond mines, as they are worked by government, and strictly monopolized: much smuggling consequently prevails. In some years the quantity discovered by government has amounted to as much as 4000 octavas of eighteen carats, but these are years of rare occurrence: taking the average, however, of some years, the number of octavas would come to near 1200. In this quantity there would be, of course, many of large size, adding immensely to the value. It is calculated that about the same quantity is smuggled; and there are strong reasons to suppose, that if no difficulties were thrown in the way, owing to the facility with which they are obtained, the produce of Brazil diamonds, in every way as fine as the oriental, would have considerable effect on the demand.

With respect to the quantity of gold which comes from the mines, it is immersed in a certain degree of obscurity. The one-fifth due to government is the principal cause that I never could ascertain, in each mine which I visited, its exact produce. I shall have another opportu-

[page] 58

nity of saying more on this head, and explaining why the produce of the gold mines is on the decrease, which I certainly conceive to be the case. Knowing the amount of the workings at the commencement of the century, and from information I collected in Rio de Janeiro and in the mines, and making allowances for that exaggeration so common in Brazil, and all new countries, I consider the annual value of gold certainly does not exceed £900,000, including the contraband.

No silver is produced in Brazil. As there is lead, it would be too much to affirm that none exists, but probably the quantity would be trifling. The silver coin is mostly Spanish dollars, restamped into three patack pieces, by which a considerable profit is obtained on each.

The quantity of precious stones shipped is not now very considerable. In most cases they are sent to a losing market, being, in fact, more valuable in Brazil than in London or Paris. Aqua marines, of very large size, have been found. In January, 1811, one was found in the Riberao das Americanas, near the Diamond District, which weighed fifteen pounds, and in the same place, in the October following, one was discovered weighing four pounds. Topazes, of

[page] 59

fine quality, but seldom large, amethysts and crisolites, are also articles of exportation, and, at times, some fine specimens of these gems are to be met with in the jewellers' shops.

Correctly speaking, there are no trading companies in Rio de Janeiro: there is a society for effecting maritime assurances, but no other.