[map]

[page i]

TRAVELS

IN

CHILE AND LA PLATA;

INCLUDING

ACCOUNTS RESPECTING THE

GEOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY, STATISTICS,

GOVERNMENT, FINANCES, AGRICULTURE,

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS,

AND THE

MINING OPERATIONS IN CHILE.

COLLECTED DURING A RESIDENCE OF SEVERAL YEARS IN THESE COUNTRIES.

BY JOHN MIERS.

ILLUSTRATED BY ORIGINAL MAPS, VIEWS, &C.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR BALDWIN, CRADOCK, AND JOY.

1826.

[page ii]

C. Baldwin, Printer,

New Bridge Street. London.

[page iii]

PREFACE

THE following work is the result of observations made on several journeys in La Plata and Chile, and during a long residence in the latter country. The Author having entered into a contract with the government of Buenos Ayres to erect in that city the machinery for a national mint, made a voyage to England in furtherance of this object During his passage he employed most of his time in arranging his notes relative to the trade, manufactures, resources, and government of Chile, with a view to publication.

On his arrival in England, in June, 1825, he compared these notes with the subject matter of his letters and journals, written as the events occurred, and forwarded to London; these supplied him with still more extensive materials for the accomplishment of his purpose. On showing these to several literary friends, he was encouraged to extend his ob-

a 2

[page] iv

servations to the form under which they now appear; he was the more induced to listen to these suggestions on finding, upon his return to England, the numerous misconceptions which were entertained, and the incorrect accounts which had been published relative to these countries.

The author having in a short space of time completed the machinery before alluded to, is now obliged to return to Buenos Ayres in pursuance of his contract, and to commit his manuscript to the hands of the publisher without its having undergone the revision he had intended.

He may, therefore, with some reason, claim the indulgence of the reader, for such inaccuracies and defects of style and arrangement as he is conscious pervades it. He has diligently devoted all the time he could spare to the prosecution of this object, both in the collection of matter, and in the laborious preparation of the numerous maps, plans, and drawings, given in these volumes.

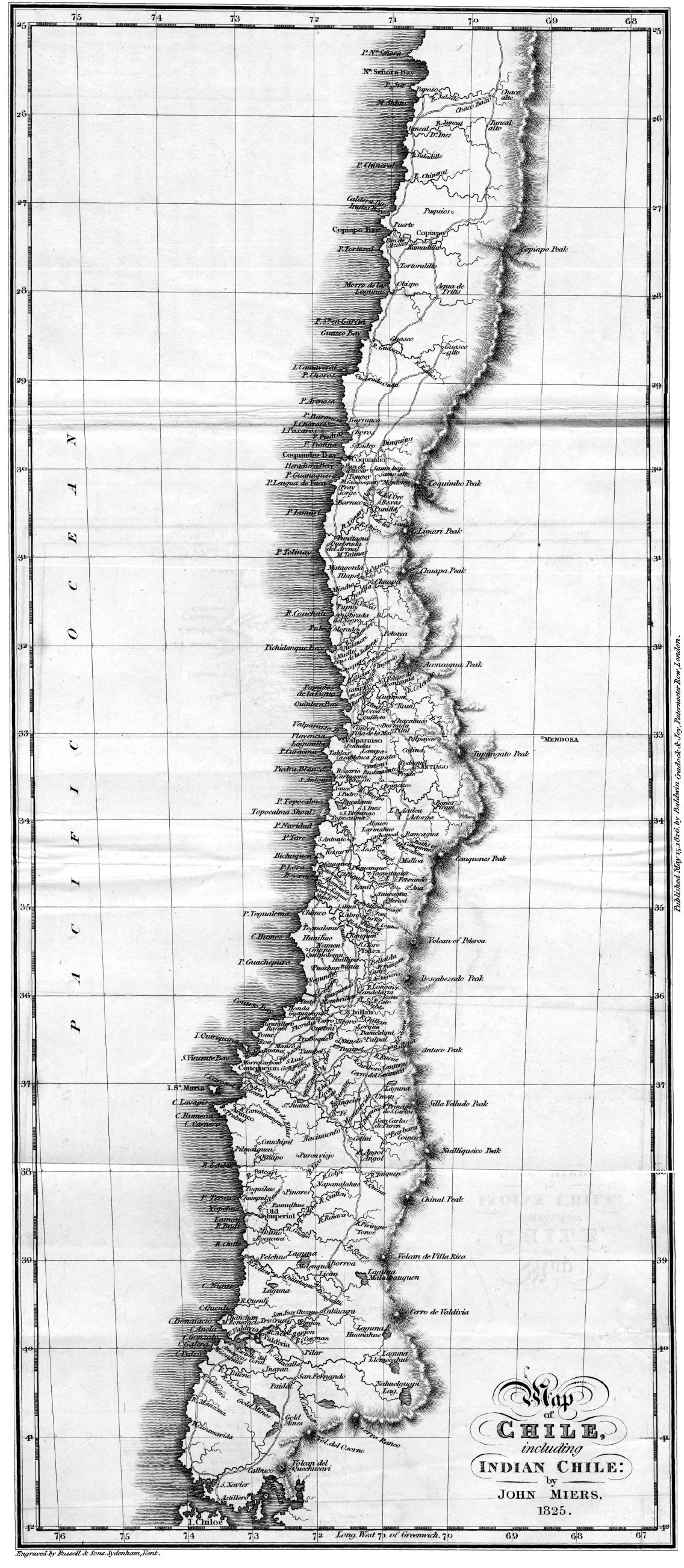

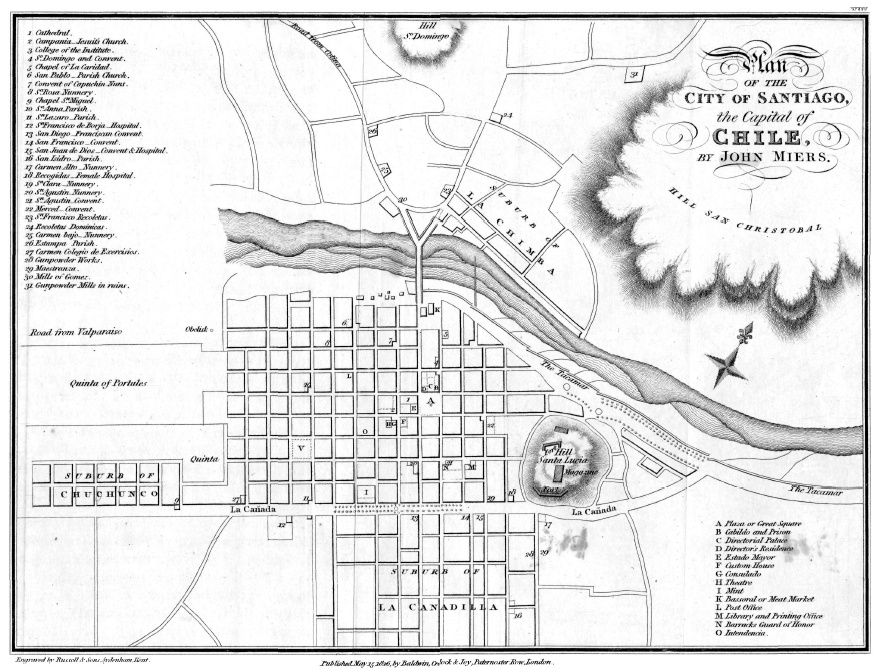

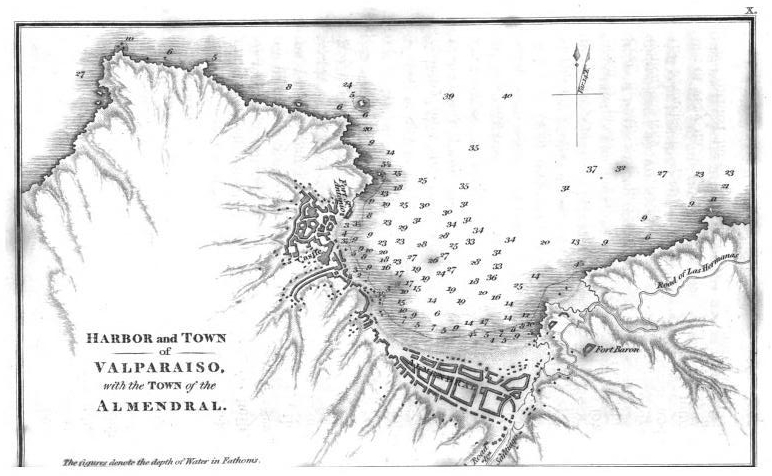

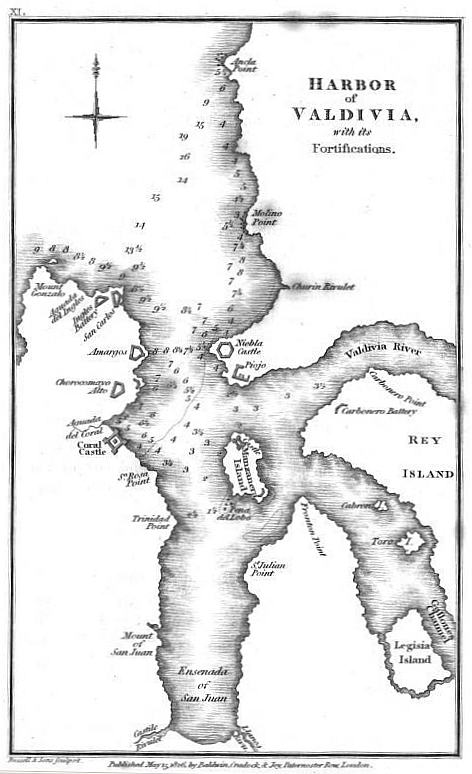

For the convenience of folding, the maps have been reduced to their present small size by the engraver. The map of the portion of Chile between Valparaiso and Mendoza is made from actual survey by the author; the other large map is nearly alto-

[page] v

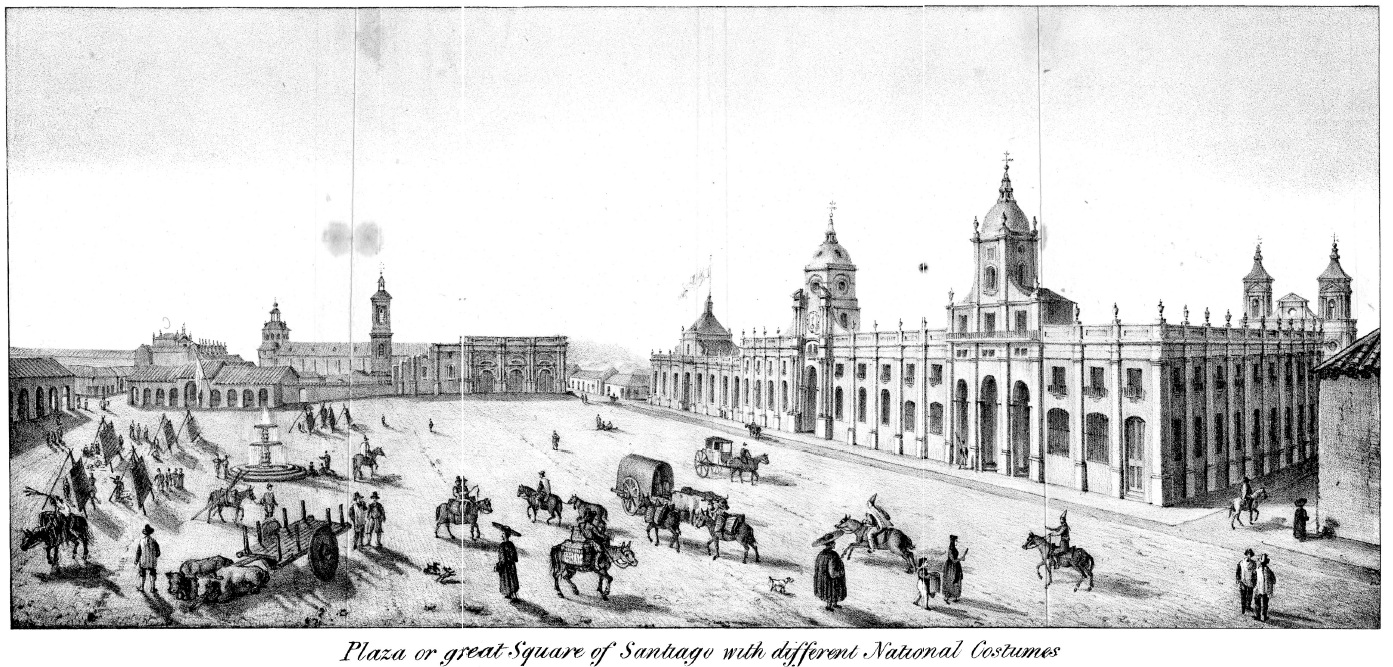

gether original, and prepared principally from his own observations, assisted by information from persons in the country qualified to afford it. The general map of Chile contains merely the names of places, leaving out all traces of the mountainous ramifications, which, upon so small a scale, would have caused confusion, and have made the map unintelligible. The plates are all made from drawings prepared by the author;—they are ably lithographed by Mr. Tell Baynes and Mr. E. T. Parris, and it is hoped will illustrate the subjects they are intended to explain.

It was the intention of the Author to have given some account of the natural history of Chile, but he found it impossible from want of time. In the botanical department, he made during his residence in Chile, Buenos Ayres, and Mendoza, upwards of two hundred drawings, including several novel genera; the remainder being nearly all new species of known genera, illustrated by descriptions, and he has materials for nearly an equal number of others. For the satisfaction of such of his readers as feel an interest in these pursuits he has added in the Appendix a list of the plants described in his drawings. In the ornithological department there is also added

[page] vi

in the Appendix a list of the drawings and descriptions he has prepared of the passeres. These several drawings are intended for subsequent publication as his other avocations may permit.

London, December 20, 1825.

[page vii]

LIST

OF

THE VIEWS, PLANS, MAPS, &c.

With Direction for placing them

VOL. I.

| Page | |

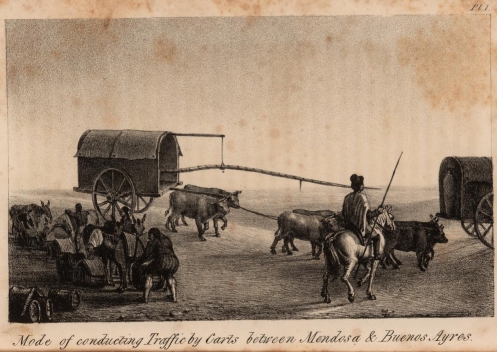

| 1. Mode of conducting Traffic by Carts between Mendoza and Buenos Ayres | 243 |

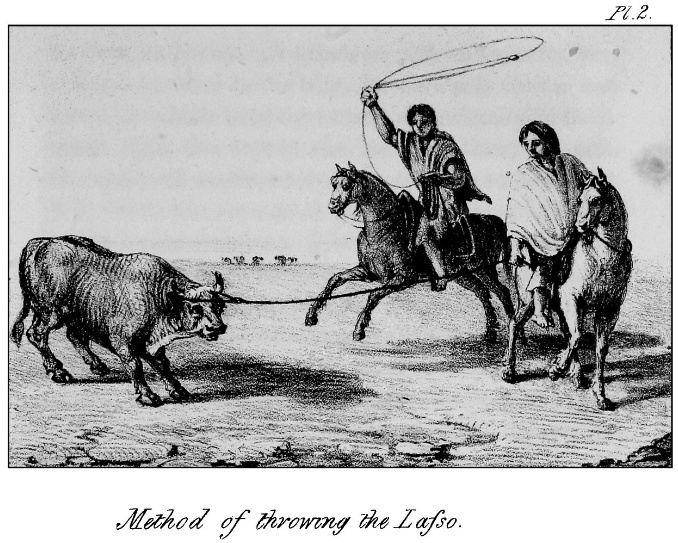

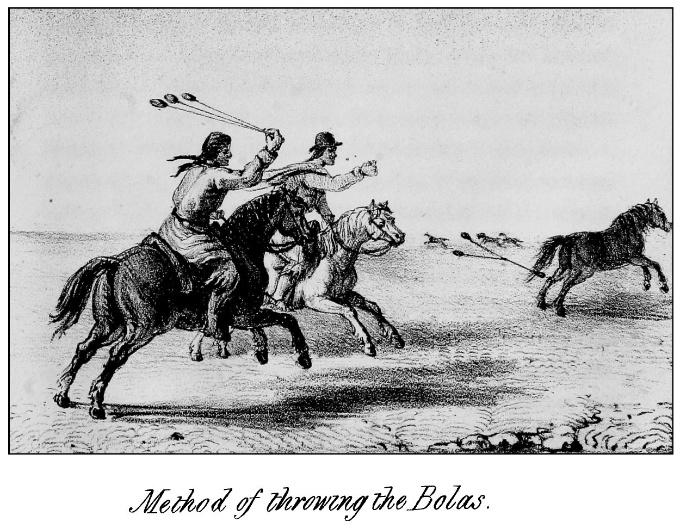

| 2. Method of throwing the Lasso Method of throwing the Bolas |

88 |

| 3. Huts at Villa Vicentio in the Cordillera | 169 |

| 4. Cerro de los Penitentes, a remarkable castellated Formation in the Cordillera | 306 |

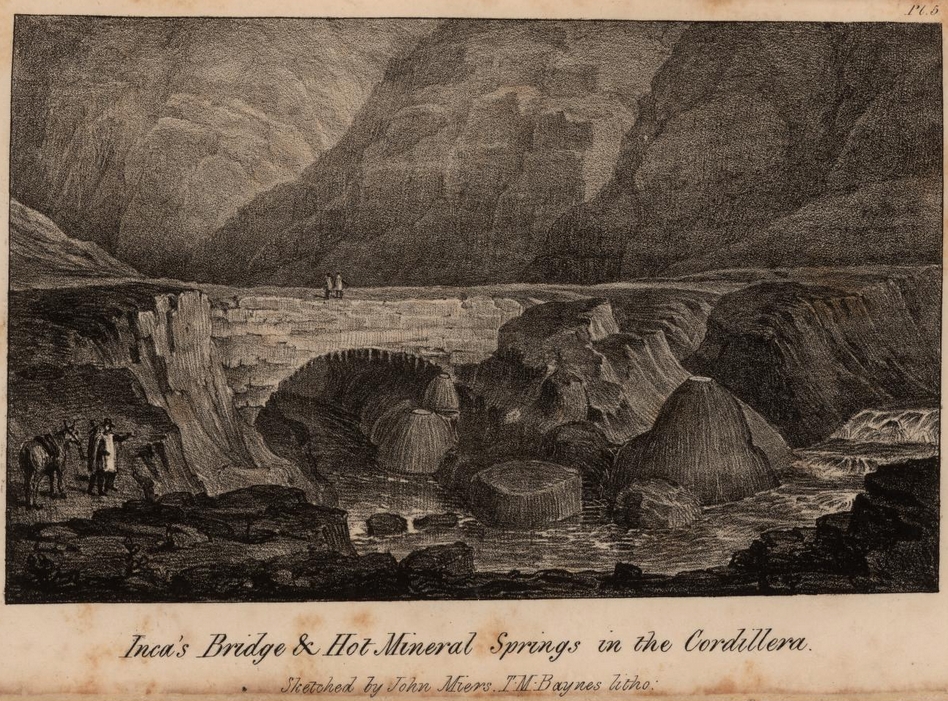

| 5. Incas Bridge, and not mineral Springs in the Cordillera | 308 |

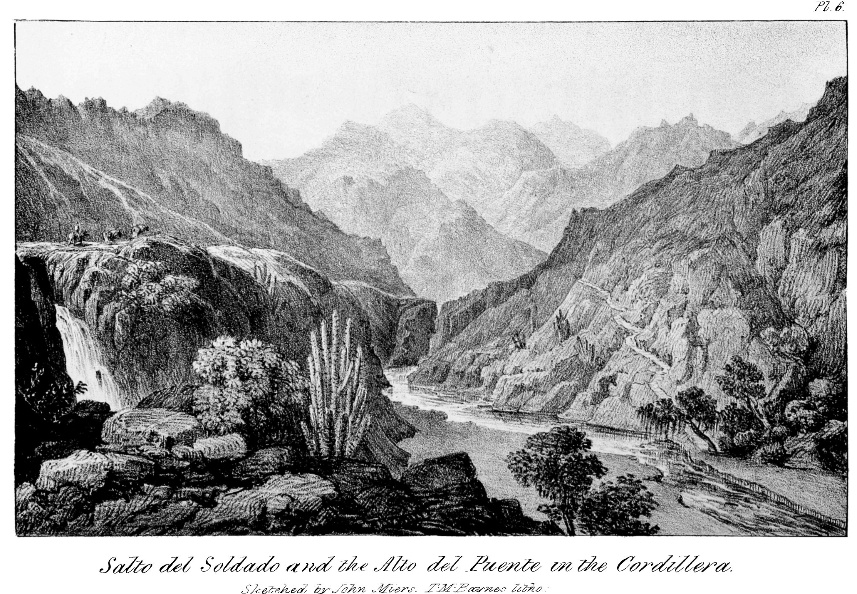

| 6. Salto del Soldado, and the Alto del Puente in the Cordillera | 331 |

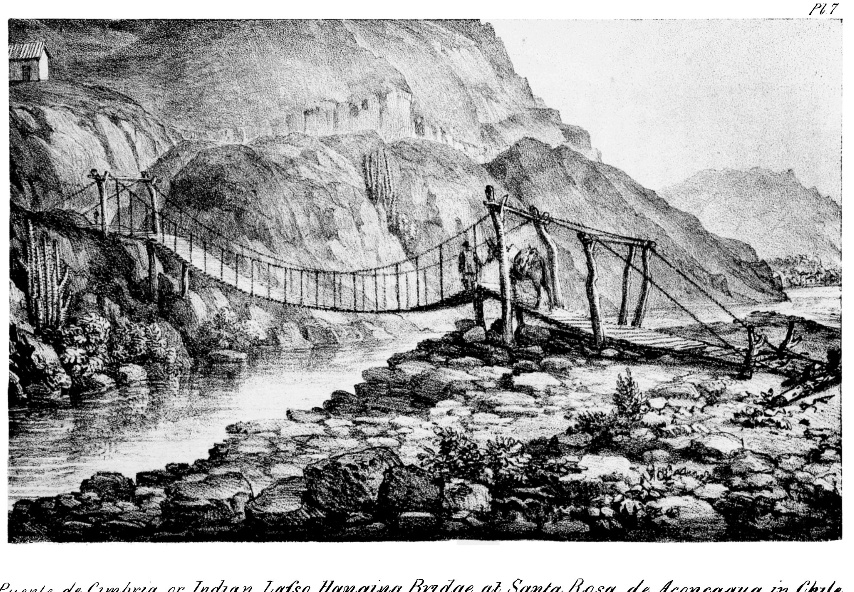

| 7. Puente de Cimbria, or Indian Lasso Hanging Bridge, at Santa Rosa, in Chite | 334 |

| 8. Plan of the City of Santiago, the Capital of Chile | 426 |

| 9. Plaza, or great Square of Santiago, with different costumes | 426 |

| 10. Harbour and Town of Valparaiso, with the Town of the Almendral | 440 |

| 11. Harbour of Valdivia, with the Fortifications | 486 |

VOL. II.

| 12. Diversions observed among the Peasantry of Chile on the Festival of Corpus Christi | 218 |

| 13. Manufacture of Utensils of Copper | 293 |

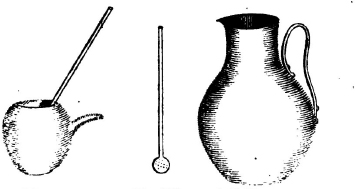

| 14. Wine making Boiling Cocido Distilling |

297 |

| 15. Construction of a Rancho Ploughing Plough |

227 |

[page] viii

| 16. Mode of using the Balsa Plan of the Balsa Carts used in Chile |

327 |

| 17. Flour Mill used in Chile Trapiche, or Water Mill used in Chile for grinding Ores of Gold and Silver Ingenio, or Machine, for pounding Ores |

305 |

| 18. Furnace used in Smelting of Copper Cancha de beneficiar, or Mode of Amalgamation of Gold and Silver Trapiche, or Mill used at the Lavaderos, or Gold Washings |

391 |

| 19. Furnaces for the Reduction of Gold and Silver | 401 |

By an error of the lithographer in plate 18, the Flour Mill is called a Trapiche, and the Trapiche a Flour Mill.

MAPS.

Map of the country between the Rio de la Plate and the Pacific Ocean, to face the title-page, VOL I.

Map of Chile, including Indian Chile Vol. I. 400

Map of a portion of Chile with the intermediate mountain ranges and passes over the Cordillera, between Valparaiso and Mendosa, to face the title-page, Vol. II.

[page xi]

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

LONDON TO BURNOS AYRES, AND THENCE TO BARRANQUITOS.

Page

Project for setting up Copper Mills in Chile.—Leave England.—Arrive at Buenos Ayres.—Journey from Buenos Ayres to Barranquitos, on the Road to Mendosa across the Pampa Country 1

CHAPTER II.

BARRANQUITOS TO MENDOZA.

From Barranquitos, through San Luis de la Punta, by the Post-road to Mendosa.—Tables of Posts—I. Buenos Ayres to Mendosa by the Pampas.—II. Buenos Ayres to Cordova.—III. Buenos Ayres to Santa Fè 83

CHAPTER III.

MENDOZA TO VILLA VICENCIO.

Mendosa and its Neighbourhood described.—Climate.—Diseases.—Vineyards and Wines.—Leave Mendoza.—Journey to Villa Vicencio.—Disaster there.—Consequences.—Place described.—State of the Weather.—Return to Mendosa 147

CHAPTER IV.

ARECO TO BARRANQUITOS.

Areco to Barranquitos by the Post Road.—Montoneros.—Indians.—Native Creoles.—Face of the Country.—Locusts.—Harvest-home 194

[page] x

CHAPTER V.

OBSERVATIONS ON THE COUNTRY BETWEEN BUENOS AYRES AND MENDOZA.

Neighbourhood of Mendoza described.—People.— Education.—Slaves—Provisions—Cattle—Pampas.— Difficult to Colonize.—Want of Trees.—San Juan.—Proposal for a Colony there. — Caravans. — Province of Cordova.—Cordova once a Seat of Learning.—Its former and present State.— Geology.—Mountain Ranges,—Mines of San Juan.—Carolinas and Famatima.—Pampa Indians.—Their Manners, Customs, Dress, Superstitions.—Population of the Provinces of the La Plata.—Conduct of the Spanish Government.—Its Consequance 223

CHAPTER VI.

MENDOZA TO SANTIAGO.

Journey over the great Chain of the Andes by the Pass of Uspallata, including Observations geological, botanical, and descriptive of this mountainous Country.—Hot Springs of Villa Viccucio—Tha Parámillo.—Plains of Uspallta.—Valley of the Souda—River of San Joan—Souda Winds—Showers of Sand.—Volcanic Formation.—Mines of San Pedro. — River of Mendoza. — Lasso Bridge. — Mountain Passes described.—Tambillitos.—Casas de los Indios.—Pará-millo de Juan Pobre. —Peak of Tupangato.—Casuchas.— Guanaco Hunting, — Castle-formed Mountains. — Incas' Bridge.—Hot Springs—Bezoar Stones 268

CHAPTER VII.

MENDOZA TO SANTIAGO.

Paramillo de las Cuevas.—The Cumbre, or highest Pass of the Andes.—Attenuation of the Atmosphere.—Other Passes.—Red and green Snow.—Valley of Calavera.—The Portillo.—Springs.—Salto del Soldado.—River Colorado and Bridge.—Bridge of Viscacha.—Valley of Aconcagua.—Town of Santa Rosa.—Lasso Bridge.—Chacabuco—Santiago.— Hints to Travellers.—Itinerary.—Mendoza to Santiago.— Barometrical Tables.—Other Passes over the Cordillera.—

[page] xi

Pass of Dehues.—Of has Patos.—Of the Portillo.—Of Planchon.—Of Antuco.—Winter Travelling 313

CHAPTER VIII.

SANTIAGO TO VALPARAISO.

Road from Santiago to Valparaiso by Casa Blanca.—Post-house of Podaguel.—Cuesta and Post-house of Prado.—Gold Mines of Curicabi.—Cuesta of Zapita.—Case. Blanca.—Las Tablas.—View of Valparaiso.—Road from Santiago to Valparaiso by the Dormida.—Polpayoo Lime Works.—Tiltil.— Cuesta Dormida.—Limache.—Concon.—Valparaiso.—Table of Distances between Santiago and Valparaiso 360

CHAPTER IX.

CHILE DESCRIBED.

Limits.—Proportion of cultivatable Land.—Climate.— Earthquakes.—Great Earthquake in 1822.—Diseases 378

CHAPTER X.

CHILE DESCRIBED.

Grand Divisions.—Jurisdictions.—First, or Northern Jurisdiction, containing the Provinces of—I. Copiapo.—II. Coquimbo.—Copper Mines in these Provinces 400

CHAPTER XI

CHILE DESCRIBED.

Second, or middle Jurisdiction, containing the Provinces of—III. Quillota.—IV. Aconcagua.—V. Santiago.—VI. Mellipilli.—VII. Rancagua.—VIII. Colchagua.—IX. Maule. —Gold, Silver, and Copper Mines.—City of Santiago.—Port of Valparaiso.—Geological Observations.—Volcanos 410

CHAPTER XII.

CHILE DESCRIBED.

Third, or southern Jurisdiction, containing the Provinces of—X. Chillan.—XI. Itata.—XII. Rere, or Huilquilemu.

[page] xii

—XIII. Puchacal—Fertility of these Provinces.—Bay, Harbour, and City of Conception 471

CHAPTER XIII.

INDIAN CHILE.

Its Divisions.—City and Harbour of Valdivia.—Capture of Valdivia by Lord Cochrane 482

[page xiii]

GLOSSARY

OF

THR MOST IMPORTANT SPANISH AND INDIAN WORDS USED IN THIS WORK.

Adobes, sun-dried bricks.

Aguardiente, ardent spirits.

Alcalde, justice of the peace.

Alemede, public walk.

Alfalfa, clover.

Algarroba, the caroba tree.

Alojamiento, lodging.

Araucanos, Indians in the southern parts of Chile.

Aròpe, syrup from wild berries.

Aròpe de chanar, syrup of the fruit of the chana.

Aròpe de piquillin, syrup of berries of lycium bushes.

Arriero, muleteer.

Arroba, a weight equal to twenty-five pounds Spanish.

Arroba, a measure.

Asado, roasted meat.

Asentistas, contractors, slave company.

Asesor, legal adviser.

Asientos, small pieces of land left in possession of the Indians.

Audiencia, court of justice.

Avellano, hazel nut.

Baguales, wild horses.

Balsa, a float, or raft.

Banos, baths.

Barbaruria, a species of large-grained wheat.

Bayeta, coarse woollen cloth made in Chile.

Bellota, a fine species of larch.

Benehuca, winged bug of Mendoza.

Bodega, shop, shed, in which wine is made, and stored.

Bolas, balls.

Boleta de venta, bill of sale, agreement.

Bombillo, tube through which mate is sipped

Botica, a large earthen wine jar.

Brazero, chaffing-dish.

Brea, mineral pitch.

Cabildo, office of justice.

Cacique, chief, king.

Calesa, an open chaise.

Calle, street.

Camara de apelaciones, court of appeal.

Camara de justicia, court of justice.

Canada, a broad ditch.

Candeal, red-bearded wheat.

Cantaro, an earthen jug.

Capaehos, hide bags used in wine nuking.

[page] xiv

Catita, a species of green parrot.

Cebo, tallow.

Chacara, garden.

Charqui, dried beef.

Chicha, fermented liquor prepared by the Indians.

Cigarillo, or Cigarro en hoja, a small cigar.

Coca, a leaf of the erythrosilum chewed by the Indians.

Cocido, must from grapes.

Colina, a sort of cane peculiar to Chile.

Commercianles, merchants dealers.

Contra-yerro, mark put on cattle when sold.

Consulado, commercial court of justice.

Corral, a sort of pound in which horses are kept.

Costal, a hide bag which holds a fanega of corn.

Couque, fermented liquor prepared by the Indians.

Cuesta, hill.

Curague, fermented liquor prepared by the Indians.

Diesmo, tenth, tithe.

Domadores, horse-breaker, herdsman.

Estancia, cattle farm.

Estanco, monopoly granted or retained by the government.

Estere, harbour.

Estrado, a low mud bench, generally covered with a carpet.

Fanega, a measure equal to two and a half English bushels.

Faxa, woollen sash.

Frijoles, French beans.

Frasco, a measure containing about two-thirds of a quart.

Grano, grain.

Grassa, grease.

Guanaoo, an animal of the deer kind.

Habilitado, shop-keeper.

Hacienda, an estate, farm.

Haceendado, land-owner, farmer.

Intendente gobernador, chief municipal officer of a province or town.

Intendencia gobernador, his court, or office.

Juez del partido, constable of the district.

Junta, council, committee, for state purposes.

Lasso, a missile weapon made of hide.

Letrado, doctor learned in the law.

Lugares, reservoirs.

Machete, a cutlass used by the Indians.

Machi, Indian soothsayer.

Madrina, mare which leads a troop of mules.

Malal, Indian fortification.

[page] xv

Malon, robbery, surprise, murder.

Marco, MARK, eight ounces.

Matanza, slaughtering place.

Matesito, calabash in which yerba is infused.

Matriz, principal church.

Misa de Gracias, thanksgiving.

Monte, a game played with cards.

Onza, ounce.

Otorgar, to grant, to accede to.

Palangana, a deep silver dish.

Palos, stripes with a cane.

Pantano, lake, swamp.

Para hacer saber, to make known.

Patio, court-yard.

Payla, a large copper pan.

Peleucones, old royalists.

Petaca, a box made of hide.

Piara, a troop of eight mules.

Plaza, square.

Polucra, green vitriol.

Poricho, a sort of cloak.

Prorrata, impressment of mules and horses.

Pueblo, village.

Puente, bridge.

Pulperia, liquor-shop.

Pulpero, keeper of a pulperia.

Puna, the sensation felt on ascending high mountains.

Quadra, land-measure.

Quartel, soldier's quarters, barracks.

Quebrada, ravine, valley.

Quintal, 100 pounds Spanish.

Rancho, a hut.

Reboso, a triangular shawl.

Resguatero, custom-house officers.

Rio, river.

Samochado. See Chicha.

Sillon, woman's saddle.

Teniente, lieutenant.

Terremotos, violent shocks of earthquakes.

Tinajas, large earthen jars used in making wine.

Tolderias, Indian encampments.

Toqui, general-in-chief of the Indians.

Trapiche, water-mill.

Travesia, desert.

Tremblores, slight shocks of earthquakes.

Tribunal de Cuentas, account and audit office.

Trigo blanco, white wheat.

Vara, Spanish yard.

Visto bueno, approval.

Uingues, a race of Indians resembling Europeans.

Ulmen, general of Indians.

Ulpa, a mixture of barley meal and water.

Yerba, herb of Paraguay.

Zandia, water-melon.

[page break]

[page] 1

TRAVELS

IN

CHILE AND LA PLATA.

CHAPTER I.

LONDON TO BUENOS AYBES, AND THENCE TO BASEANQTTITOS.

Project for setting up Copper Mills in Chile.— Leave England.— Arrive at Buenos Ayres—Journey from Buenos Ayres to Barranquitos, on the road to Mendosa, across the Pampa country.

OFFEES having been made to me in the year 1818 to undertake an enterprise of some magnitude in Chile, I embarked with a friend a very considerable capital in the speculation. It was oar intention to erect a very extensive train of machinery in that country for refining, rolling, and manufacturing copper into sheathing. The inducements were powerful and alluring. Copper of fine quality was said to be procured in abundance from the mines of Chile, and could be purchased for about half the price it bore in the English markets. Nearly all the copper raised in the country was exported in its crude state to the East Indies, its islands, and China, in return for manufactured goods; and as all

VOL. I. B

[page] 2

the copper sheathing consumed in the extensive shipbuilding there carried on was sent from England, the inference was irresistible, that, upon the given data, an immense fortune might rapidly be made in the proposed speculation:—especially as coal might, it was said, be procured for nothing in Chile, and labour was not one-fourth of the cost it bore in England; added to this, the demand for sheet copper along the coasts of the Pacific was also said to be very great, particularly in the sugar manufactories of Peru. These tales were magnified by the South American deputies then in London; and from the two Chile ambassadors I received strong assurances that the government would afford every facility, protection, and assistance, to an enterprise of such vast importance to that infant country. Under these flattering prospects, I dispatched for Chile, in different vessels, about one hundred tons' weight of machinery, and embarked with my wife in a merchant brig, called the Little Sally, with about 70 tons of machinery, implements, and baggage; taking with me several very skilful workmen, engineers, millwrights, and refiners. A surgeon of considerable professional merit, Mr. Thomas Leighton, who was engaged in the Chileno naval service, offered to accompany us, an offer I rejoiced at; and it will be seen in the sequel what essential service this meritorious gentleman extended towards us in the difficulties, we encountered on our journey; services which I shall ever remember with the deepest gratitude. We left the Downs on the 26th January, 1819, having been previously detained there above three weeks, by contrary winds and

[page] 3

violent gales; after a very favourable passage of 51 days, we made Cape Saint Mary, at the entrance of the river Plate, and after two days' careful pilotage in ascending this shoally river, we anchored on the evening of 22d March, in the outer roads of Buenos Ayras. None but very small vessels drawing little water can enter the inner roads; the outer roads, where we were obliged to anchor, are nine miles from the town. Next morning we landed, two hours being occupied in rowing from the vessel to the beach; our impressions upon landing were in sad discordance with the notions of grandeur which we had been led to form from the reports of those who had visited this city, as well as from books of travels respecting the country. The water close to the shore runs so very shoal, that our small boat could not approach nearer than 50 yards from the beach: a number of carts being in attendance to take us from the boat, we entered one of them: this vehicle was like nothing we had seen before—it was of the rudest construction—the bottom was a square frame of wood, with some sticks laid across it—it was open before and behind; the two sides about breast high ware made of rough sticks, bound together with strips of hide; the wheels were of very large diameters, and of very clumsy construction, the axletree being of wood; there was not, in fact, a piece of iron in the whole structure; it was drawn by two horses abreast, one of them mounted by an Indian looking rider, of strange appearance, and still stranger costume; a loose hide was in the bottom of the cart, on which we stood, there being no seat: the sight of this first specimen

B 2

[page] 4

of South American handicraft was ominous, and depressing. We were landed at a kind of jetty, called the Mole, formed of rough blocks of mica slate; the houses fronting the beach I mistook for gaols, as they had no glass sashes, and the open windows were defended by iron gratings; but on entering the town, I found all the houses constructed in the same manner, mostly of one ground floor; their deserted appearance, and shabby exterior, bore more the semblance of gaols than the habitations of an industrious, civilized, and free people. As it is my intention at some future period to describe Buenos Ayres in detail—its government, statistics, and resources, I shall not now enter into any further particulars respecting the city, but proceed to describe the preparations for my journey across the country of La Plata to Chile. We went to the English hotel, at that time kept by a Mrs. Hunt, from whom we received great civility and attention; but the want of accommodation induced us to look out for better quarters, and I encountered much difficulty in procuring a lodging. We entered the houses of a great many families, whom we were told were likely to receive lodgers, they all expressed great readiness to accommodate us, until they learned that a lady was of the party, when they at once refused to receive us; at length we found a family who agreed to accommodate us during our proposed short stay in Buenos Ayres. The head of this family was Don Jose Maria Calderon; he was an old Spaniard, whose fortunes had been ruined by the events of the revolution; he was about 60 years of age, and held the situation of

[page] 5

vista (or searcher) at the Custom House; his wife was an agreeable, lively woman, a sister of General Belgrano, who then commanded the national patriot forces in Upper Pern; the family consisted of eight children—two sons established in business in Men-doza—another in Spain—one in the army with Bel-grano—another a clerk in the Secretary of State's office—a promising lad educating in the college—sand two daughters: the amount they demanded for the accommodation of myself and my wife was extremely moderate, seventeen dollars for our stay (three guineas and a half). I shall give an account of our first day's entertainment as a sample of the accommodation we received. At dinner, we were placed side by side, at the top of the family table, the usual seat of guests, according to the Spanish custom. Three black female slaves waited at table: we had about twenty dishes, of different sorts, one brought on as soon as another was removed; we had bread and vermicelli soup, different kinds of stews, and bouillis of beef, roast veal, salads of lettuce, and dishes of different vegetables, dressed in oil. Our hosts wished to press upon us plates served from every dish in succession—they were extremely solicitous to make us eat more than we wished. After dinner one of the slaves said a long unintelligible grace; upon the conclusion of which all the family crossed themselves upon their foreheads, mouths, and breasts: the cloth was not removed, but was kept for the dessert, which consisted of a profusion of ripe figs, peaches, nectarines, apples, pears, and oranges; nothing but water was drunk at dinner, or afterwards; a bason and towel were

[page] 6

brought, in which all the company washed their hands in the same water, it being first presented to us: they then rose from the table, and retired to their siesta, or afternoon's sleep.

These kind people displayed much anxiety to accommodate their meals to our taste, and provided for us at morning and evening tea and coffee, which they never were in the habit of taking themselves: their principal meal was supper, of which they partook at midnight.

The artisans brought out by me were bearded and lodged at a tavern. My first care was to arrange for the transhipment of my machinery to Chile, and the preparation for our journey. From all persons, both natives and English, I heard dreadful accounts of the state of the country: the Montonero, as the roving murderous brigands of Artigas, a well-known factious partisan, were called, over-ran the country between Buenos Ayres and Chile, so as nearly to intercept all communication; and our determination to cross the country was looked upon as a desperate attempt scarcely to be accomplished; but in the several accounts related to me I could not trace any sufficient evidence to induce me to lay aside my intention. The principal circumstance which produced this determination was the pregnancy of my wife: by preferring the land journey to the sea voyage, we expected we should reach Chile before the period of her accouchement. Having been invited to a conference with the Secretary of State, I consulted with him respecting my intended journey. He assured me that little danger was to be apprehended from the Montonero, as they had been driven

[page] 7

by the troops of Buenos Ayres to the opposite banks of the Parana into the province of Entre Rios; the interior of the country, he said, was very unsettled, and he doubted much that we could proceed along the regular post-road, but he thought we might venture across the Pampas by a more southern route. After weighing circumstances seriously, we finally resolved upon the land journey. I had brought with me from England a caravan for the purpose of crossing the country, but in this respect fresh difficulties were started: it was said that the road was cut into deep ruts; and as the width between the wheels of the carriages of the country was considerably greater than that of our English vehicles, I was assured that we should travel in the caravan with great difficulty. As all agreed in this respect, and as I did not wish to encounter the risk of stoppage upon the road, I judged it expedient to purchase a carriage at Buenos Ayres, which I was told could easily be disposed of in Mendoza. For this I paid 500 dollars, a sum, at the rate of exchange at that time, equivalent to 112l. 10s. I hired four native drivers for the journey, one for each horse intended to draw the coach. They were men accustomed to travel the road, and were acquainted with all the different routes: they were paid according to their experience, one at 50 dollars, another at 40, the third at 30, and the fourth at 25 dollars for the journey, which was computed at 900 miles.

Having, at several interviews with the Secretary of State, made him fully acquainted with the object of my journey to Chile, he suggested that greater advantages would accrue to me by settling in the La

[page] 8

Plata country, and pointed out Cordova as an admirable scite for the erection of my extensive machinery, dwelling with great eulogium upon the richness of the copper mines there; but the object of his greatest anxiety was the obtaining a portion of the coming machinery then on its passage from England to Chile, which I intended to offer for the use of the Chilian Government, and proffered every advantage I might wish for that it was in the power of the Government to grant, provided I could arrange my affairs so as to settle in Buenos Ayres in preference to Chile. This I assured him was now out of the question, as my measures had been already prospectively taken, and could not be cancelled. He however expressed his hope that at some future time some arrangement might be made, with this view; he offered his best wishes for the success of my enterprize, granted an unsolicited order for the transhipment of the machinery I had brought with me free of the usual transit duties, gave me a passport across the country for myself and retinue, without exacting the usual heavy stamp duty, and begged I would apply to him for any assistance it was in his power to grant I was extremely gratified with the attentions he showed me, as a satisfactory illustration of that good disposition on the part of the South American Governments in favour of British enterprize which I had been led to expect I should assuredly meet with.

Having completed the arrangements for the transhipment of my machinery, and taken the necessary measures respecting the coach, I prepared for my departure. Horses cannot be procured for such

[page] 9

a journey at the several post-houses along the road hut by a licence from the post-office at Buenos Ayres, for which certain charges are made. One of these charges is a tenth of the whole sum fixed by law as the price of hone-hire for the whole journey, called la decima parte: another of the charges, called la parte, is an arbitrary charge. The duties exacted at the poet-office were as follows:—

| Dollars, | Reals. | |

| La parte | 12 | 1 |

| La decima parte, one-tenth part of 298 dollars, 2 reals, the estimated charge of post-hire of eight horses to Mendosa. | 29 | 2 |

| 41 | 3 |

equal to nine pounds six shillings sterling.

The charge allowed to be levied by the post-masters had been, from long established usage, fixed at the following rate for each carriage-horse one real, 6d. per league on the road from Buenos Ayres to Mendoza; for each saddle-horse and each packhorse half a real per league to San Luis, a distance of 218 leagues, and one real per league thence to Mendoza, a distance of 82 leagues. All the arrangement being completed, our departure was fixed for the 5th April.

Our whole set-out would in most other countries have appeared ludicrous. Our luggage was packed before and behind the body of the coach, and covered with hides, as was also the top of the coach. The fellies of the wheel were lashed with strips of wetted hide, which as they dried served by their contraction to strengthen them.

[page] 10

Other strips of hide were carried from the naves to the fellies, and twisted by means of pieces of wood, the ends of which rested on the spokes, and further strengthened the crazy wheels. There was a strong pole to the coach, which was to be drawn by four horses, harnessed, if harness it could be called, by a rope made of slips of hide fastened to the girths of the horses, for in this country a horse never draws by a collar. The leaders were in like manner harnessed to a clumsy piece of wood fastened to the end of the pole. Each horse had its rider; every thing was prepared on the evening of the 5th April, 1819, and the horses were brought out; but, as is usual in this country, so many delays occurred as to make it necessary to defer our departure till the next morning.

April 6.—About six o'clock we again made an effort to depart; our stock of provisions, consisting of bread, biscuit, tea, sugar, &c. were stowed under the seats of the coach, and several small boxes Were taken into the vehicle. It was half-past eight before we were able to start; my wife, myself, and two of my men, rode inside the coach; the doctor and three others of them on horseback; we had also two pack horses loaded—all the animals were of a very sorry kind. The coach body was old, and hung by means of pieces of hide which went under it, and were supported upon four pieces of iron instead of springs, two before and two behind, secured to a sort of frame-work, which held the hind wheels to the fore-carriage instead of a perch. It was a quarter past nine before we cleared the city of Buenos Ayres, owing to many stoppages oc-

[page] 11

casioned by the ox carts, which were coming into the city in trains, with the daily supplies for the inhabitants.

The country for some distance, after leaving the. suburbs, is principally laid out in gardens and orchards of peach and apple trees. The fences are mostly in good order, and sufficiently high, composed of American aloe, sometimes of cactus, growing so thickly as to be impenetrable by cattle—a dry ditch generally runs outside the fence.

Our course was S W by S. Our party had none of them been used to riding; they were consequently awkward enough; and this drew forth peals of laughter from the peons in our employment, as well as from the many gauchos whom we met going toward the city, and who, being accustomed to ride from the moment they are able to sit upright, are all most excellent horsemen. At ten a. m. we reached the little village of San José de Flores; at half-past eleven we reached an estancia, or cattle farm, where two or three of our postillions changed their sorry beasts. At twelve our course was W by S; then W; we were here assailed by multitudes of flies and other winged insects, which annoyed us greatly. On approaching the little village of Morron, the road turns S, and afterwards S W; the village consists of five neat brick houses, about which large flocks of pigeons were seen; immense numbers are bred here for the supply of Buenos Ayres. By this time almost all the stirrups of my equestrian companions had failed, notwithstanding they were all new, and had been purchased for the journey of the most respectable

[page] 12

dealers in Buenos Ayres; they were replaced without much trouble, by strips of hide cut from the covering of our baggage; the peons' knives, and their dexterity in the use of them, were of great service to us. But the necessity of replacing the broken stirrups caused considerable delay. One of my Englishmen, who had never been on horseback before, was unable to ride his horse any further, and was obliged to get up behind the coach and sit upon the luggage. The horse of another was knocked up, so that the coach was frequently stopped to allow him to come up—the horse he had recently changed being little better than the one from which he had dismounted. This afforded no small degree of mirth to two gaucho soldiers, who had overtaken us, and who amused themselves by flogging on our unfortunate Englishman's jaded horse. At length one of the soldiers lassoed a stray horse, which he saddled for the Englishman, turning the other loose; this horse, however, was no better than the other. These were but bad symptoms at the commencement of so long a journey as we had undertaken.

At half-past two we reached the first post-house at Puente de Marques: it is built of burnt bricks; its inmates were at dinner, which consisted of pottage made of maize boiled in grease.

Here we found a coach which had passed us a short time before our arrival; the travellers were a military officer and two ladies on their way to Luxan. The ladies were both seated on a little low bench, partaking of the pottage with the peasants, all eating out of the earthen vessel in which it had

[page] 13

been boiled or stewed, and with the same spoon which they handed round.

The nearly naked children of the poor people were squatted on the ground eating a mess in the same manner. We were cordially invited to partake of the feast with the other travellers, but we were as yet too young in travelling in this country to taste such messes, or to use the same spoon in the way we saw it used by the fair ladies and the dirty cottagers: we had to be sure some spoons in our canteen; but had we produced them on this occasion we could hardly have put them up again, but should have given them to the people of the house, and this would have been too great a privation; all were extremely civil; and we received their politeness as it was intended.

This is the first stage, and for this the charge is always double—the distance is seven leagues.

The horses provided for this stage were as bad as the worst of the hackney-coach horses in London, and were all knocked up, so as scarcely to be able to move by the time we reached the post-house. We were full five hours on the road.

We started again with fresh horses at 3 p.m., and soon passed a cottage near a bridge which crossed a rivulet. Here we paid a toll of one real. We were fairly in the country, and beyond the boundary of such civilization as the city of Buenos Ayres was calculated to produce. The country was smooth, covered with fine short grass, and had the appearance of an interminable bowling green. Our course was SW by S, then W by S, then W until we arrived at an estancia, where we changed horses. We con-

[page] 14

tinued our course W, and at five arrived at the Cañada de Escobar. We intended going on to Luxan, three leagues further; but our peons, who acted as our guides, recommended us to remain where we were, as it was necessary, they said, to greese the coach-wheels, and for doing this they must have day-light: much against our inclination, we acceded to the proposal. We therefore halted, having travelled this day no more than ten leagues.

The post-house of Escobar very much resembles all the similar stations on the high roads to Mendoza and Peru; an account of it will, therefore, serve for them all. It is a large hut, built of rough crooked stakes stuck into the ground; cross pieces are lashed to the uprights, with slips of hide, twigs of bushes or reeds are wattled in between the cross pieces, and tied with strips of hide. The frame thus composed is daubed over on both sides with mud, laid on with the hands. The roof is framed in the manner of the sides, with pieces tied together with hide; the ridge of the roof is supported by two poles inside of the hut, and is thatched with grass, the whole building being most rude and miserable, resembling in every thing, except its size, an Irish mud cabin. The postmaster and his family lived altogether in this one room.

By the side of this hut was another of smaller dimensions, for the use of travellers. There was neither chair, table, nor bed, in this house of accommodation; these things, or any of them, are rarely to be found in the post-houses; the only means of keeping off the bare ground is a kind of bedstead formed of four short stakes driven into the ground,

[page] 15

and four cross sticks lashed with strips of hide, as a frame from which a bullock's hide is stretched. Very few of these places are possessed of a door, but a hide is provided to keep out the weather. Another hut made in the same manner, often not plastered with mud, a mere wattled shed, is commonly attached to these residences, and is used for cooking. I need hardly say these huts have no windows. Some, however, of the post-houses are divided into two rooms, one of which is the shop or drinking room, the other the sleeping place; a square hole may be observed under the eaves of some of them, made to admit light and air; and these, like the door-way, are generally closed by a piece of hide, when necessary, to exclude the weather. Scarcely any are plastered or smoothed at all, but are in the rough state which dabbing on the mud with the hands gives them.

Miserable as they are, they afford some shelter to the traveller in stormy weather, although it frequently happens that they are not impervious to rain, which falls in heavy showers during the winter and in thunder storms in the summer season.

In these places the traveller may, if he pleases, find shelter from the heavy dews which fall in the night over this extensive country; these dews penetrate the clothes, and wet one through, chill one, and produce very uncomfortable sensations.

The greatest objection, at least to Europeans, in these dreary receptacles, is the incredible number of fleas, bugs, and even still more disgusting vermin. The fleas breed in the very earth; this is no exaggeration; for, however many years one of these places

[page] 16

may have been unoccupied, there does not appear the least diminution of these vermin. There is no exception; every hut is alike, whether it be inhabited or not; they are never swept out, nor is any filth removed; the ashes from occasional fires made in them remain from year to year.

Having resolved to remain here, the first inquiry was, could any thing be had for dinner—there was not a morsel of either meat or bread, and we were obliged to send two leagues to procure a sheep, as well as some wood to cook it. Two boys on horseback were dispatched; one returned with the sheep alive across the horse before him; the other brought the wood on a hide as a sledge, drawn by his lasso, from his saddle girth. Our peons pulled out their long knives, and one of them nearly severed the sheep's head at a stroke. It was then hung to the roof of the cooking hut by the legs, the skin was stripped off, and the carcass cut into lumps in an incredibly short space of time, and placed before the fire to roast, almost before life could be said to be extinct. The most fleshy parts were selected without any regard to the shape of the pieces; one of these was spitted on an iron used for marking cattle; the pointed end was stuck into the ground, sloping over the fire, and thus the meat was exposed to the flames of the lighted wood; the spit was occasionally turned, so that every part of the meat might be succesively presented to the fire.

This is the favourite mode of cooking, it is called asado; it is, however, a good mode, as the quickness of the operation prevents the loss of the gravy, which remains in the meat. The people themselves

[page] 17

do not remove the spit from the fire, but cut off slices, or pretty large mouthfuls, from the piece as it roasts; any such conveniencies as tables, chairs, plates, forks, &c. being unknown to them. They squat round the fire on their heels, each pulling out his knife, which he invariably carries about him day and night, and helps himself as he pleases, taking with it neither bread, salt, nor pepper. We made a good meal from the asado, with the help of the conveniencies we carried with us in our canteen. We had to wait, however, two hours and a half from the time of our arrival before we commenced eating.

We slept in the following manner:—I had some boards made to form a platform even with the seats of the coach, on which we made our bed; it was very uncomfortable, as the shortness of the coach did not permit us to lie at length. To me this was not of much consequence; but to my wife, in her situation, it was a real grievance, and was soon severely felt. Our peons slept on their saddles in the hut.

April 7.—We rose at six. It felt remarkably cold; this was occasioned by the heavy dew, for the thermometer was not lower than 50°. For our fare and accommodation for twelve persons, our host charged only one dollar.

The baggage on the coach being thought too heavy, a portion of it was removed, and another horse was hired to carry it.

The next stage was five leagues, the cost of which, for ten hours and the postillion, was 4½ dollars.

At half-past seven the cavalcade left the Cañada de Escobar; our course was WNW, over a fine level plain, and an excellent flat road; the herbage was a

VOL. I. C

[page] 18

thick short clover. We saw many herons, plovers, and herds of wild deer.

The horses were very poor; one of them could with great difficulty he made to keep up with us. The approach to Luxan is through lanes, having on each side extensive gardens and orchards. The fruit-trees are principally peach, fig, and orange. The fences, like those in the environs of Buenos Ayres, are of aloe, and the broad-leafed cactus, called tuna. We entered the village about half-past eight, and drew up in the plaza, or square, opposite to a house on the west side, called the custom-house. As soon as the coach stopped, we were accosted by the officer whom we had met at the Puente de Marques. He had just turned out of bed, and came in his shirt and trowsers to hand my wife out of the carriage. He led her to his room, which was also his bed-room, begging her to excuse him while he finished his toilet, as it was only a quento de militar. He was very polite and attentive, and quickly procured milk and fruit in abundance.

I went to the house of the commandant on the north side of the plaza, and was soon introduced to him. He was very polite, and would hardly look at my passports.

I sent for the curate of the village, to whom I delivered a letter from his friend in London; he was much pleased, and offered us any assistance we might need, but we needed none that he could give. I purchased a stock of bread for three days' consumption, being told that none could be procured for that space of time. This, as it turned out, was not the case. The bread cost 1½ dollar. We paid two

[page] 19

reals toll for a bridge outside the town, which we should have to pass on our journey.

The houses at Luxan are all of one ground-floor, except that of the Cabildo, on the east side of the plaza, which has rooms above. They are all built with sun-burnt bricks, called adobes, not white-washed. The church is a small plain building, with a little turret, and a cupola top. We left Luxan at half-past nine, and soon came to the bridge for which wehad paid toll: it passes over a deep ravine, which is the bed of a river in the rainy season, but now quite dry. One of my men was so completely unable to sit his horse, that he was taken into the coach, and I mounted in his stead.

We had to pass a deep Cañada, a sort of broad ditch in which rushes grow: in many parts it was boggy. The horse of another of my men lost his legs, and threw his rider, which delayed us some time; but this was amply compensated by attracting the attention of a young man, a native, and an officer in the army of Buenos Ayres, who joined our company, and continued with us until we reached Mendoza. He was both agreeable and useful to us, unacqainted as we were with the customs and resources of the country, and almost ignorant of the provincial language of the Gauchos. A mile beyond this cañada we came to the cañada de Rochas, at half-past ten, distant two leagues from Luxan; here we remained only to change horses. The post-house was precisely of the same description as that at which we slept the preceding night. I paid for ten horses for the next stage, of five leagues, 4½ dollars and for refreshment 5 reals. We started

C 2

[page] 20

again at eleven, the course NW, forded a Cañada at half-past eleven, and soon afterwards passed another broad ditch; at twelve we came to an estancia, where we changed the coach-horses; our course was WNW. At half-past twelve we passed another fording-place; the country we had traversed was one uninterrupted plain, broken only by water-courses, which, at this season of the year were mostly dry; not the least rising ground appeared within view in any direction; not a tree was to be seen; the plain seemed boundless, and, with the exception of small spots about the estancias, wholly uncultivated.

We observed great numbers of snipes, herons, hawks, and plovers.

We saw no cattle except in the immediate neighbourhood of the estancias, and these were by no means so numerous as we expected. The herds were very small, compared with those seen eastward of Buenos Ayres.

The cattle here, and indeed all the way to Mendoza, are a smaller breed than that on the banks of the La Plata.

The stories told of the immense herds of wild cattle which rove over these plains are wholly untrue; there are not, in any of the provinces, unowned cattle, and consequently none that can be called wild. There are wild cattle to the south of La Plata, among the Indians, over whom the Spaniards have no control, and who still continue to have every thing in common; and with whom cattle, horses, and deer, are alike considered as animals of chace for the purposes of subsistence. In the estancias, the number of cattle belonging to each is always known;

[page] 21

they are placed under the charge of herdsmen, called domadores, frequently under the eye of the owners themselves. Every animal is marked, and is regularly watched, so that none stray far beyond certain limits. The domadores know every individual animal; and their duty is to be on horseback all day long, taking care that none go beyond the boundary. It is their duty also to collect all the cattle every night within the corrales, or pens, made for their reception. Every proprietor of an estancia has a particular mark, which is burnt in upon the skin of the animal. It is generally some initial or rude character about six inches long. Horses are marked in the same manner. When any animal changes his owner, the seller puts another of his marks, making it double; this is called the contrayerro, and denotes his having no longer a claim to the beast. The purchaser then affixes his mark to establish his claim. These markings are necessary in a country without fences, and where it frequently happens that herds belonging to different persons are mixed together.

Hitherto the soil appeared to be a rich fine mould,—not a pebble was to be seen—not even sand or gravel. Where cultivated, it produced luxuriantly. It needs only the hand of man to make these immense plains as productive as any prairie land can be. Except in the middle of summer, the intervals between rain are short; and the very heavy dews which fall in the dry season compensate, in a great measure, for the want of more frequent showers; it was now the autumn of the year, and the land was covered with herbage.

The horses hereabout are of rather a small breed,

[page] 22

half blooded, and for short distances very swift, but they are soon fatigued, and consequently not well adapted to perform the long stages they are often obliged to travel.

The few fruit-trees about the estancias were in full verdure.

At one o'clock we reached the Cañada de la Cruz; the huts at this post-house were, if possible, worse than those of Cañada de Escobar, and the inhabitants much more filthy and savage in their appearance. They had neither bread, meat, poultry, grain, nor any one edible thing; I hired to horses to Areco, a distance, of six leagues, for which I paid 5½ dollars; we remained only a quarter of an hour in effecting the relay. On setting off, the road for the first mile was W by N, and then W for three miles; at nearly two o'clock we passed a cañada course, and soon afterwards a rivulet; these now occurred frequently; at three we crossed a pantana, or boggy swamp, and reached the post-house of Areco at half-past three. On applying for horses, the postmaster, whom I found afterwards to be a great rascal, advised me by no means to continue the post road. He said that the succeeding post-houses of Chacras de Ayola, Arecife, &c. had been all destroyed by the Montonero, who had carried off the horses, and terrified the inhabitants, so as to make them flee the country. He assured us that the nearest place where it would be possible to obtain a change of horses, was the village of Salto, where, at the house of a friend of his, they could be procured. Then he said we might either proceed to the NW, and again join the high road, beyond the

[page] 23

space which had been devastated by the Montonero, or we might strike off into the Pampa country. He strongly advised the latter, as most secure; he related several tales of the Montonero, and again assured us that no horses could be procured on the high road, nor any nearer than Salto, which he represented to be at the distance of twenty leagues; he offered to send forward relays of horses, to enable us to proceed at the usual post-rate. He told us, that, after all, the road by Salto would not lengthen our journey more than four or five leagues; and his whole deportment appeared so considerate and friendly, that we were induced to take his advice, and agree to go by Salto. Of the actual distance I could not myself judge. I had with me the best English map; but that conveyed no information on the proposed route, and was, besides, so incorrect in other respects, as to be of very little use. I found out afterwards that this fellow had deceived us; all his tales were gross exaggerations, or total false-hoods; even the distance to Salto turned out to be fourteen leagues instead of twenty, at which rate he charged us.

Finding it now too late to commence so long a stage, we determined to remain here all night; it was also necessary for our Englishmen, who, notwithstanding they had already become tolerable jockies, feared so long a day's ride as the next promised to be. Abundance of provisions were to be obtained at the Fortin de Areco, a place one league to the southward, where there is a mud fort, forming one of the several military posts, stretching from the Bay of Samborombom, at regular intervals of a

[page] 24

few leagues, and continuing through Salto, Rocca, Pergamino, and Rosario, forming a line of defence between the people of the province of Buenos Ayres, and the Pampa Indians. We purchased eight eggs for a rial (6d.); a cheese made in the country, weighing five pounds, for three rials; a sheep for two rials; we purchased also some melons; those called sandias, a species of water melon, are very good. All these (except the eggs), with the wood for cooking, were brought from the fortin by messengers dispatched on horseback. We had an excellent dinner; a portion of it at least was well cooked, by means of our military canteen, which was of the greatest service to us throughout our long and wearisome journey. We had boiled fowls, and a favourite dish of the country, made of pieces of mutton, boiled or stewed, with maize and onions, an asado of mutton, and melons for a dessert. The postmaster had neither plates, dishes, knives, nor forks; these were in part supplied from the canteen; and the men, who had already begun to accustom themselves to this sort of campaigning, were all well pleased. The most handy and useful among us was the doctor; he was always satisfied and cheerful, always ready, and always able to do any thing which our circumstances required. We slept as on the preceding night.

April 8.—We rose at day-break, and breakfasted on the remains of yesterday's repast. We made a trial of the yerba, or tea of Paraguay, infused in a tea-pot, using milk and sugar, and found it to be an excellent and agreeable substitute for China tea. We paid for eleven horses 18½ dollars, and started from Areco soon after eight o'clock. Our course was

[page] 25

WSW; then W; we crossed a rivulet, and a swamp, and soon after ten reached an estancia, where we changed horses. We had travelled in a zig-zag course, which appeared to me quite unnecessary, as the country was very level, and it led me to suspect that our guides were playing us some trick; according to their account, we had travelled five leagues; but on inquiring at the estancia, I found the distance was no more than three leagues; the deception arose from two causes: first, a desire to make out as long a course as possible, to cover the cheat practised upon us, in charging for too great a distance; and, second, from the common practice of the guides of compelling travellers to go the shortest possible distance each day, in order to keep them on the road, for their own emolument. Not the least confidence should be placed in any of these people, who are not ashamed of being detected in the grossest attempts at deception; we started again, still going in the same zig-zag course; about noon, after changing horses, we passed by a very large estancia; we changed horses at one, and again before two; these delays, as well as the course we had travelled, were intended to deceive us in the distance, to cover the fraud of our host of Areco. We reached Salto at half-past three. The son of the postmaster of Areco, who had accompanied us, requested us to wait outside of the village while he went to make inquiries—this seemed strange-there was something about his whole conduct which increased our suspicion of him, after waiting half an hour; and just as we were about to drive into the village he returned, and conducted

[page] 26

us to the house of a miller, the friend whom his father had spoken of. We were treated with much civility—the females paying all the attention in their power to my wife. Here the stories of the postmaster of Areco were repeated with considerable exaggerations; we were told that it was quite impossible for us to go by the high road, that our course must be over the Pampas to the Puente del Sauce, and even that course was not entirely free from danger. We began to suspect the stories they told us to be fabricated; but as we had heard of the Montonero having infested the high road even before we left Buenos Ayres, we feared to encounter the risk, but resolved to seek further information. I therefore waited on the commandant of the village to ask his advice. He was very polite, told me the tales of our landlord were fallacious; that their intention was to deceive us, in order to make the most of us: that the force of Artiagas was on the opposite side of the Parana; and as General Belgrano now occupied the bridge of Rosario, the main road was quite clear; he therefore advised me to proceed to join the main road again by the cross route of Pergamino. Before I went to the commandant, our host and his people urged us to agree with them for horses, saying they were acquainted with the proprietors of the estancias on our route, and could procure relays all along; they were very attentive, and wished to prepare dinner for us. On my return from the commandant, I told them I was resolved to go to Pergamino, from which they endeavoured to dissuade me; but finding I was resolved not to take their advice, they suddenly changed their tone, said they

[page] 27

could furnish no horses, and behaved in such a manner as induced us to quit his house. It turned out that there was no postmaster, no horses to be had of any one, and no house or hut for our accommodation. Our travelling companion, being an officer, could not be refused horses for himself, but he had no means of procuring any for us. We went to the fort, where horses belonging to the soldiery were kept, but none could be hired. Thus the afternoon was wasted; and at the close of the day we had no chance of procuring horses, except from the friend of our host of Areco, whose house we had left, and then only on his own terms. This made me resolve to go early the next morning to the nearest estancia, about a league off, and endeavour to obtain horses to take us to the nearest posthouse. We had now no house to go to, nor, as it appeared, any means of procuring food; no meat could be had in the village; the supplies were all drawn from an estancia, three leagues distant, from which meat, &c. was brought in early in the morning, when every one purchased his daily supply; neither bread, milk, nor eggs, could be purchased; wine alone was to be procured at the pulperia, or common store. We dined on the bread and cheese we had fortunately brought with us; our men took possession of the miller's covered ox cart; and I and my wife, as usual, slept in the coach.

The mill was very rude and simple; scarcely any iron was used in its construction, wood and hide being almost the only materials. The motion was communicated by two mules, which at the end of two long poles dragged round a horizontal toothed wheel, into which a lanthorn pinion worked; this

[page] 28

was connected with the upper stone; the motion was exceedingly slow, for, instead of a hundred revolutions, barely ten turns were effected in a minute, so that the corn was rather crushed than ground. Precisely of this description are all the mills in the neighbourhood of Buenos Ayres. No where is there a sufficient fall of water to give the moving power; and wind-mills are far above the mechanical genius of the people of La Plata.

In our journey to-day we saw great numbers of wild deer, ducks and quails, and also large flocks of ostriches; they were of a grey colour, and appeared to be smaller than the African ostriches; they are very shy and difficult to take, running as fast as the swiftest horse.

The soil was still covered with rich pasture. The Guardia de Salto is a small village consisting of several detached houses of the kind before described, built of sun-dried bricks, and so disposed as to form two streets at right angles. Most of the houses have what they call a garden before and behind, and some were placed in the middle of a pretty large garden. The uniformity of the streets was preserved by the walls of the gardens, which, like the houses, were built with sun-dried bricks. As usual, there is a sort of a square, called the plaza, on one side of which is the quartel, a range of small miserable rooms for the use of the military stationed here. On the opposite side is the fort, a square pile of unburnt bricks, each side of which extends about twenty feet, and is about ten feet high: one side is sloped, and formed into steps, by which to ascend: on the side opposite to these steps was placed a four-pounder

[page] 29

swivel. The fort looked like a mud bank; it was much worn by the weather, and had a most wretched appearance.

Next morning, April 9, at day break, when about to start for the estancia, in order to procure horses, the son of the post-master of Areco offered to take us on to Chacras, the next posthouse in the Pampa country. To avoid further delay, I accepted his offer, and paid him 5½ dollars for the journey, he assuring me it was full six leagues, but it turned out afterwards that he had again deceived us, the distance being only five leagues. As there was no possibility of making him refund, no further notice was taken of his extortion; but we resolved to be more on our guard against the deceptions which we had reason to believe were constantly practised to the greatest extent possible.

It was a quarter past nine before we could get away from Salto; our course was NW; we crossed a considerable rivulet, which runs into the river Tercero; changed horses at an estancia soon after ten o'clock, and arrived at the post-house of Chacras at half-past eleven. Here we obtained a supply of meat, milk, and eggs, for breakfast. The miserable appearance of this place exceeded, if it be possible, the most wretched of the huts we had seen, it being built of mud and sticks, the thatch ragged, and the walls falling to pieces. The people were extremely filthy and poor. Their first salutation was a prayer for segars or tobacco. I took pity on their misery, and gave them some. I had been advised to take a supply with me, being assured that a few segars would

[page] 30

induce these indolent people to do more than anything else would, and to give me a choice, where a choice could be had, of the best horses. This was, however, useless expense and trouble; these people think of none but themselves, nor of any thing beyond the single object they aim at, and are consequently totally devoid of gratitude. What little use they make of the intellect they possess is by lies, and low cunning, to cheat you. Very few of the people of Buenos Ayres have ever travelled far into the country, and know little more of it than the people of London. Our fellow traveller, although a native and an officer in the army, was as ignorant as ourselves. Had we attended to the recommendations of our friends in Buenos Ayres, we should have been encumbered with a multitude of useless things, and obstructed in our journey.

The people out of the villages, although living on the most fertile ground, and having nothing to do, never cultivate the smallest spot; at none of the post-houses was there a garden. The postmaster told us wonderful stories of the Montonero, and of the danger we ran; on observing that we entertained no apprehension, he seemed astonished. He was evidently impressed with fear, and assured us that we should fall in with them, if we attempted to proceed. This did not shake my determination to gain the main road. My intention was to proceed to Roceas, and thence to the main road at Pergamino. Again I felt seriously the want of a correct map of the country.

The distance to Roccas being six leagues, I paid

[page] 31

for eleven horses 5½ dollars; we left the post-house at one o'clock, and soon afterwards forded a river.

The cattle seen grazing on the plains were more numerous than in the former part of our journey; they were also of a larger breed. We saw vast numbers of beautiful snipes. At three we passed a hut which presented a phenomenon—clothes hanging out to dry. This was the first sign of washing, or of any sort of cleanliness we had seen on our journey. Such are the filthy habits of these people, that none of them ever think of washing their faces, and very few ever wash or repair their garments: once put on, they remain in wear day and night until they rot. The poncho is the only article of dress which is ever removed; those who have one sometimes take it off to cover themselves at night, when. stretched on the bedstead before described, or on what is by far more common, a hide spread on the ground.

The poncho is made of wool, is about six feet long, and four feet broad. It has a slit in the middle, just large enough for the wearer to put his or her head through. It hangs in folds, before and behind, nearly as low as the knees, and somewhat below the elbows at the sides. It is well adapted to the people of these countries, who are mostly on horseback, leaving them the free use of their arms, and in no way encumbering the rider. It is not worn to preserve warmth, but to keep off the wind and rain. Ponchos are generally made of worsted, spun to a fine thread by the women, who dye the yarn of several brilliant colours. This yarn is also woven

[page] 32

by the women in the rude loom of the country. They are neither fulled, scowered, nor otherwise prepared; the whole manufacture is as simple as possible. The many brilliant colours which poncho contains are woven in with great care, and are generally judiciously assorted. Some of the better sort of ponchos are woven in fancy running patterns, not unlike the style of the ancient Greek and Etruscan borders. Sometimes the yarn is so fine, that the poncho is nearly as supple and soft as silk. These are made by the Indians in Chile. The labour bestowed on these is almost beyond belief; a single poncho giving employment to a woman for more than two years.

The least bodily exertion, except riding on horseback, is avoided as much as possible by the people of this country; they will sit the whole day basking in the sun, or enjoying their favorite amusement, to which the women are particularly partial, that of picking the vermin out of each other's hair. The whole people are, notwithstanding, healthy, robust, muscular, and athletic.

As we approached Roccas the numbers of huts increased, and I remarked the utter want of curiosity in the people. It is probable that a coach with four horses had never before been seen in this unfrequented part of the country: this, and our ludicrous troop of horsemen, would, in any other country, have brought all the people to the doors of their houses; but here no one stirred; even the women and children were equally indifferent as the men, scarcely any giving themselves the trouble of looking at us, and no one in the huts stirring to notice

[page] 33

what was passing. The torpid state of their minds has been, and will continue to be, the great obstacle to the moral and political improvement of this country. It was nearly four o'clock when we entered Roccas. Here we found ourselves again at fault; there was no postmaster in the village, and it was necessary to send a league to obtain a change of horses. Little hope, therefore, remained of advancing any farther this day. We stopped opposite the house of the commandant, to whom I showed my passports. He was very civil, made my wife alight, and took us into his house; it was the best in the town, although it consisted of only two rooms, was built with sun-dried bricks, and thatched as usual; it was white washed within and without. The bare ground served for floors; but a few old-fashioned wooden chairs ranged round the room afforded us an accommodation we little anticipated. The family consisted of the commandant, his eldest son, his wife, and four or five children, all extremely dirty in their dress and persons. All the female part of the family were employed in making paper segars for sale: behind the door of the sitting room was a chamber utensil of silver. There was neither window nor opening into either room, except the door, which was always open in the day time. The commandant offered me a segar, and assured me there was no reason to fear meeting with the monteneros, as they (400 in number) were at Ennudio, and so locked in by the troops of Belgrano and Cisneros, that it was quite impossible for them to infest the main road. There was (he said) no chance of our obtaining horses until the next morning, as this was only an auxiliary military

VOL. I. D

[page] 34

post, and the horses were kept at an estancia, a league off, there being no food for horses near the town; the water in all the rivulets was saline, the pasture is also flavoured with salt, from the soil, here strongly impregnated with muriate of soda, and continues more or less so to the foot of the Cordilleras. The inhabitants of Roccas are therefore obliged to dig wells to procure fresh water, which is found at the depth of about 50 feet. We took leave of the commandant, and joined our party at a house in the middle of a garden, into which the coach was dragged, there being no other place where we could sleep.

The village contains very few houses, and these are small and low; each habitation consists of two huts placed side by side, having each a single room; the gardens are very irregular in shape, and the whole has a wretched appearance.

There is a church here built with mud-bricks; it is a mean building; on a level, in this respect, with the huts. It was a grand feast-day (Good Friday), and the bell was tolling for mass. It happened that the clergyman, in his way to the church, fell into conversation with us, which being interesting to him, he said to the people who had assembled outside the church, some on horseback and some on foot, all dressed in their gayest attire, "no hay misa hoy," meaning he would not say mass this afternoon, putting the key of the church, which he held in his hand, into his pocket. The people immediately retired. We continued our conversation, which related to England, its laws, and the manners of the people,

[page] 35

respecting which he was very inquisitive, and made many shrewd remarks. He was in look and manner far above the common run of village curates, and seemed much respected, and probably not a little feared also by the ignorant gauchos.

Returning to our quarters, I sent for a sheep, which cost two reals (1s.); eight eggs, one real; bread, four reals, including stock for our journey; boy half a real for fetching it; wood, half a real; boy half a real for fetching it. The sheep was soon cooked, and we made a hasty meal. The garden was stocked with fig, peach, and almond trees; in another enclosure maize had been grown. The oven was in one corner of the garden; and as this necessary appendage to the most opulent in this part of the world, is always made in the same form, and generally of the same materials, the description of this will serve for all. It was built of sun-dried bricks; the base was a mass about four feet square, built up to the height of three feet above the ground; on this was raised a cupola-formed top of the same materials. Near the top of the dome was a small hole for the escape of the smoke; and in one of the sides a small hole for removing the ashes; and in the front a larger hole, by which the bread is pot in and taken out. All the holes being opened, a fire is lighted on the oven-floor, which is kept up briskly by a constant supply of sticks and brushwood, until the requisite degree of heat is obtained. The ashes are then removed, and the top hole closed with a sheep-skin, or a brick, or both. The loaves, which are always of a small size, are pushed into the oven, and the hole

D 2

[page] 36

is closed with a sheep-skin. When sufficiently baked, the loaves are drawn out upon a rude sort of peel, or flat wooden shovel. Yeast is not used—the flour is therefore kneaded with leaven.

My intention was to have proceeded hence to Pergamino, and thence by a route parallel to the main road, through India Muerto to La Esquina, but the commandant of Roccas strongly dissuaded me from taking that course. He said that it would be impossible to obtain horses, and that we should be compelled to return. The best course, he said, was through Mercedes to Melinque, thence to Zanjon and Frayle Muerto; or by the Punto del Sauce and Rio Quarto. The latter he recommended as the best of the two. Unwilling to run any chance of being delayed, I resolved to follow his advice, and determined to take horses to the Cabeza del Tigre.

In the evening the postmaster, as he was called, came to me to bargain for horses. He said he was not a regular postmaster, and that he would not furnish me with horses at the usual post charges, which for six leagues (the distance to the lake of Cabeza del Tigre) would have been five dollars and a half, but he demanded seven; and as there was no alternative, I was obliged to comply with his demand. No trade of any sort is carried on at Roccas, and, small as are the wants of the people, it is difficult to conceive how they contrive to exist.

I saw here a plough of the country; it is very simple in its construction. On account of the scarcity of trees, it is difficult to obtain wood for these rude implements, but few are therefore seen. The only iron used about them is a plate called the reja,

[page] 37

which forms the ploughing point. There is neither share, coulter, nor mould-board. The plough consists of two pieces; the body and the handle are in one solid piece, curved like a letter L; the beam is a straight pole, wedged to it. The operation of ploughing consists merely in scratching up the surface of the ground into close shallow furrows, by which the earth is disintegrated. The handle is held by the ploughman in order to guide the implement, and to regulate the depth of the furrow. The plough is drawn by two oxen, the beam being attached to the yoke. When a tree can be procured sufficiently large, the plough and the handle are both formed of the same piece; but in most cases they are formed of two pieces.

April 10.—We rose at day-break, expecting to see the horses which had been promised, but they had not arrived. We breakfasted on bread and milk— a quantity measuring about a pint was sold for a real (6d.) With the horses came a supply of beef; it was brought on horseback by a boy, the pieces being laid across his saddle, and he riding astride upon the beef—a sight not very agreeable to an Englishman; but our nicer feelings were by this time considerably blunted. We purchased a supply of bread and beef for the journey, and the peons were also furnished with a quantity, which they placed between the saddle-cloths under the saddle. This is the usual mode all over the country; it must have been half-cooked after a hard day's ride. Bread for them was quite out of the question, as they seldom, if ever, tasted any.

When an ox is killed in the country, the flesh is

[page] 38

cut off in long slips, and the bones are left with the offal, to be eaten by birds of prey, to rot upon the ground, or to be used as fuel for the oven.

The postmaster demanded four reals for the use of each pack-saddle, and eight reals for the postilions, thus making his whole charge eight dollars four reals. The regular charge would have been no more than five dollars six reals. We however had no choice; and were therefore obliged to submit. The thermometer was 55°.

We left Roccas at eight o'clock, going WNW; saw great numbers of wild deer. At ten we crossed an extensive saline swamp, filled with rushes and tall reeds; in passing it we were attacked by multitudes of mosquitos, or gnats, of a very large size; they tormented us exceedingly. At half-past eleven we came in sight of the Lago del Tigre, and at twelve reached the post-house. This post consists of three small huts, horribly filthy; the people were extremely miserable in their appearance, and little, if any, better than savages in their mode of life. The postmaster, whose face and hands were coated with dirt, was a sly, roguish-looking fellow, far advanced in years, yet very strong and active. They had a well fifty feet deep, from which they drew most excellent water, in a hide-bag tied to a lasso, or hide-rope. The water in the lake is always rather brackish, but in spring it is strongly saline. Here again we were obliged to submit to imposition. The charge for ten horses, including two postilions, should have been six dollars five reals, but the postmaster would have ten dollars four reals, which we paid him.

[page] 39

I had just before given him and his wife a tolerable supply of tobacco, which pleased them much; but this did not in the least abate their desire to impose upon us. They were totally destitute of tobacco, and had not the least scrap of paper for making segars. I supplied both; and although they would willingly have gone a whole day or more without food to have obtained these luxuries, my generosity was doubtless an additional stimulus to their exaction. I did not then sufficiently understand the disposition of these people. With them is exemplified what will universally be met with over South America, that to confer a favour is to purchase an enemy. They are governed by no moral feelings, but will submit to a haughty, overbearing tyranny, no matter by whom practised.

We started again at one o'clock; our road led through several cañadas and bogs. There was a succession, for a considerable distance, of reedy swamps; the higher parts of them were covered with a saline efflorescence. The grass was also strongly saline.

The character of the soil was changed entirely; the rich pasture land was no longer to be seen; the grass was long and coarse, growing to the height of six feet, and much resembling rye or wild oats. It grew in clumps, the roots forming small mounds at every yard or two. The road was only a mule tract, so that the wheels of the coach rebounded from clump to clump, and made the travelling in it extremely fatiguing. We were obliged to proceed cautiously and slowly. At half-past one we crossed a rivulet, the water of which was saline. It was about

[page] 40