[page i]

THE

ANIMAL KINGDOM

ARRANGED IN CONFORMITY WITH ITS ORGANIZATION,

BY THE BARON CUVIER,

MEMBER OF INSTITUTE OF FRANCE, &c. &c. &c.

WITH

ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTIONS

OF

ALL THE SPECIES HITHERTO NAMED, AND OF MANY NOT BEFORE NOTICED,

BY

EDWARD GRIFFITH, F.L.S., A.S., &c.

AND OTHERS.

VOLUME THE SECOND.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR GEO. B. WHITTAKER,

AVE-MARIA-LANE.

MDCCCXXVII.

[page ii]

LONDON:

Printed by WILLIAM CLOWES,

Charing Cross.

[page iii]

THE

CLASS MAMMALIA

ARRANGED BY THE

BARON CUVIER,

WITH

SPECIFIC DESCRIPTIONS

BY

EDWARD GRIFFITH, F.L.S., A.S., &c.

MAJOR CHARLES HAMILTON SMITH,.. F.R.S., L.S., &c.

AND

EDWARD PIDGEON, ESQ.

VOLUME THE SECOND.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR GEO. B. WHITTAKER,

AVE-MARIA-LANE.

MDCCCXXVII.

[page iv]

LONDON:

Printed by WILLIAM CLOWES,

Charing Cross.

[page v]

LIST OF PLATES IN THE SECOND VOLUME.

| To face Page | |

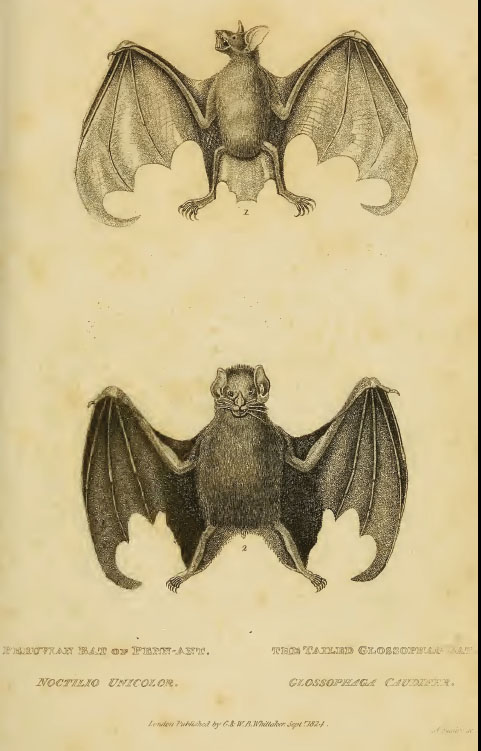

| Peruvian Bat, and Tailed Glossophag Bat (species190 and 207 of Table) | 14 |

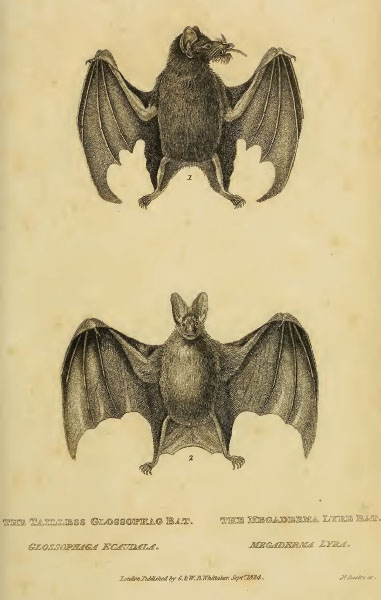

| Tailless Glossophag Bat, and Megaderma Lyra (species 208 and 212 of Table) | 14 |

| Plate I. of the "Regne Animal" | 78 |

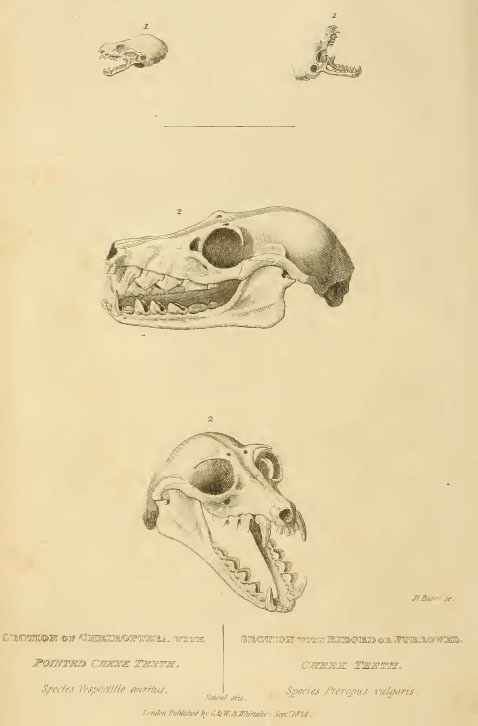

| Teeth of Cherioptera | 103 |

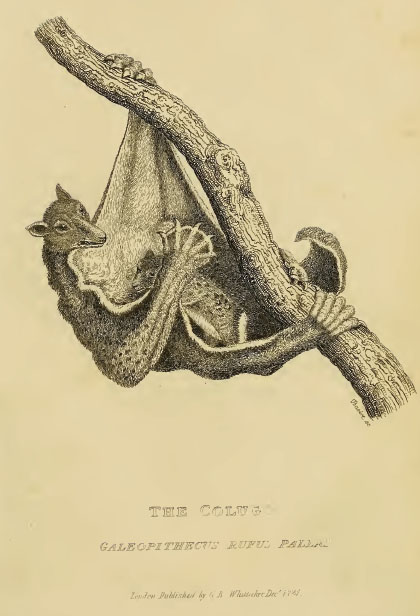

| Colugo | 158 |

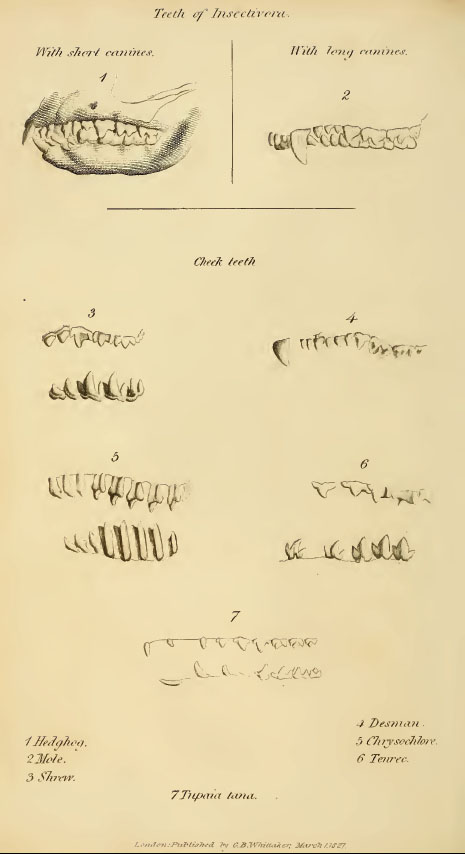

| Teeth of Insectivora | 161 |

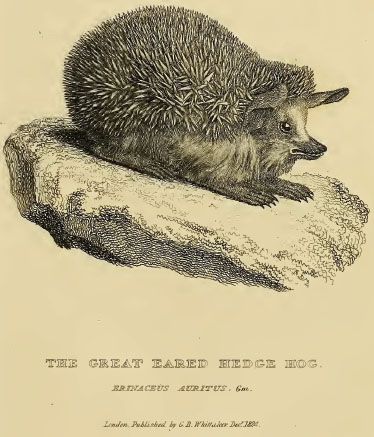

| Great-eared Hedgehog | 170 |

| Cape Chrysoclore | 192 |

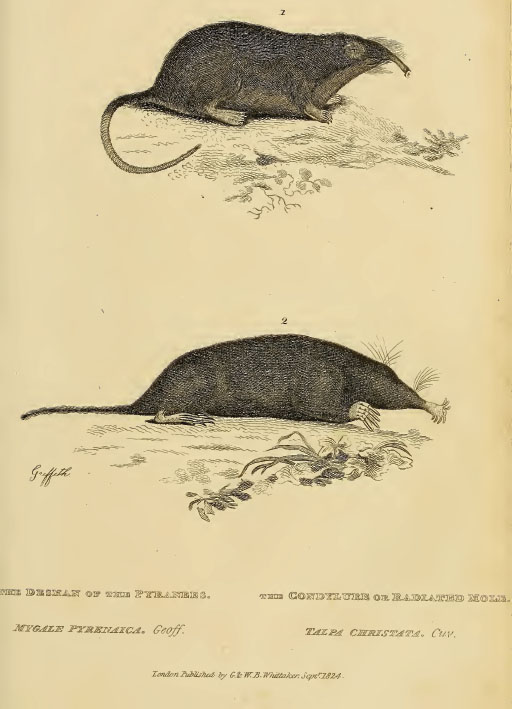

| Desman and Condylure | 210 |

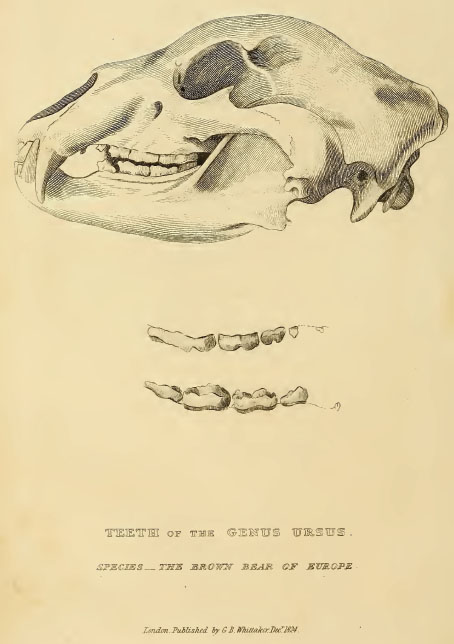

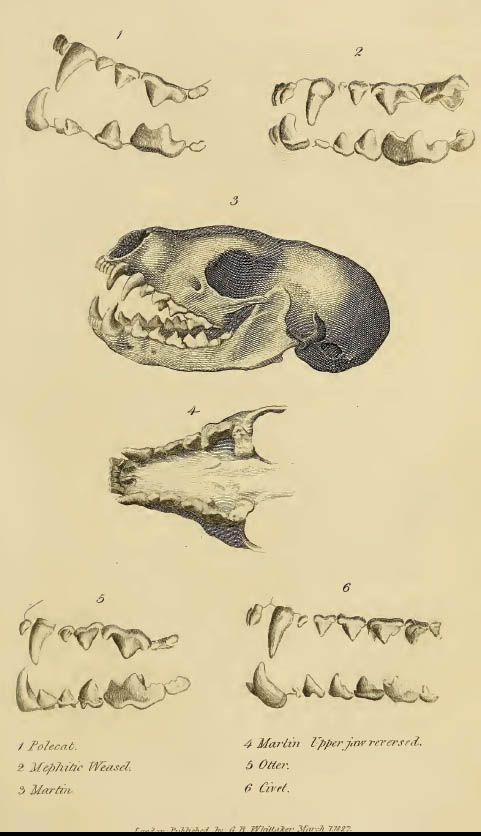

| Teeth of Genus Ursus | 219 |

| North American Bear | 229 |

| Polar Bear | 232 |

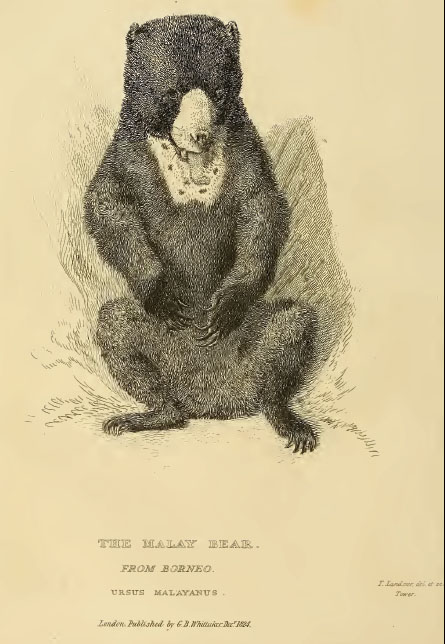

| Malay Bear | 237 |

| Taira | 278 |

| Masked Glutton | 281 |

| Ferruginous Glutton | 282 |

| Teeth of Weasels | 284 |

| White-eared Weasel | 297 |

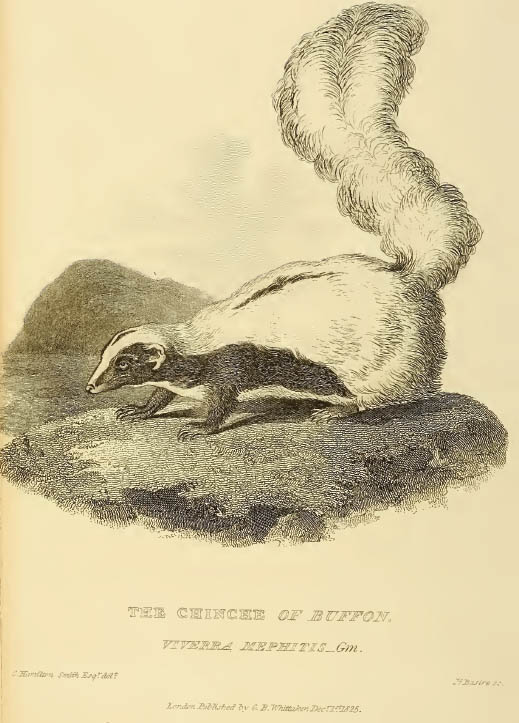

| Chinche | 299 |

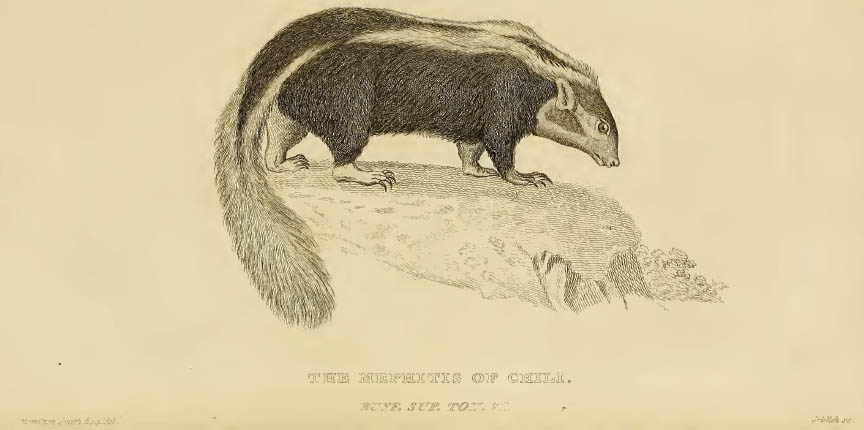

| Mephitis of Chili | 300 |

| Teledu | 305 |

| Canadian Otter | 315 |

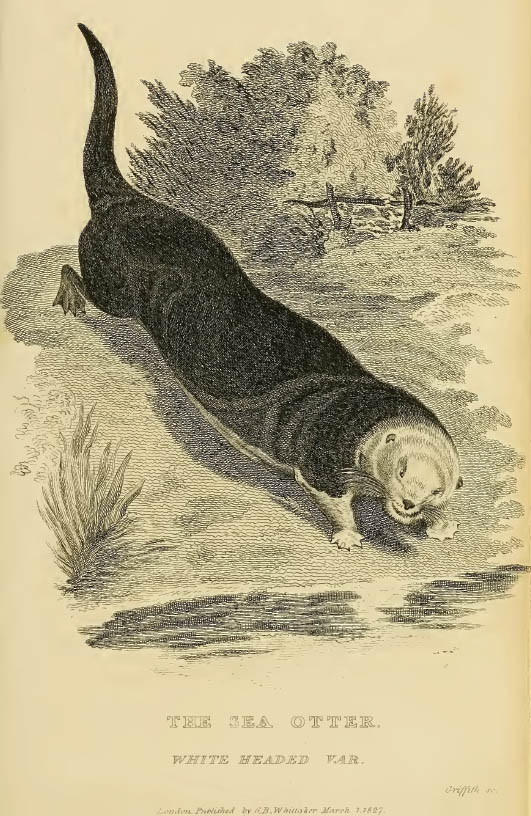

| White-headed Sea Otter | 316 |

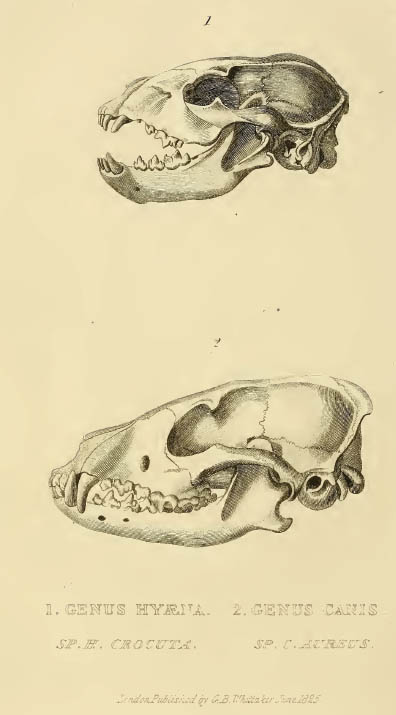

| Skulls of Dogs and Hyæna | 323 |

| Drigo, Dhole, and North and South American Dogs' Heads | 327 |

| Dogs' Heads, Second Plate | 339 |

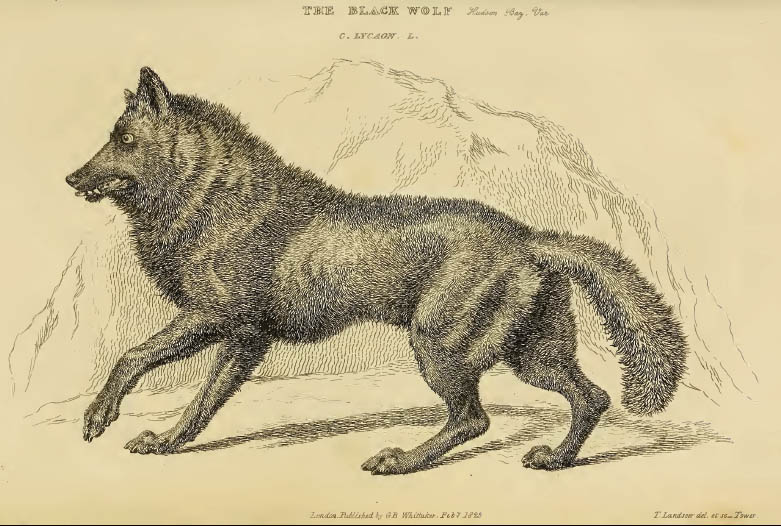

| Black Wolf | 348 |

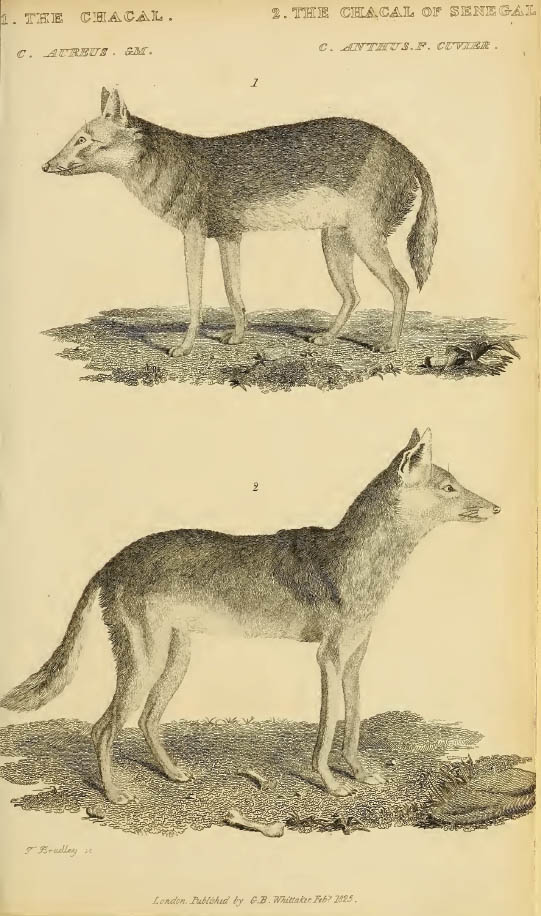

| Chacal | 350 |

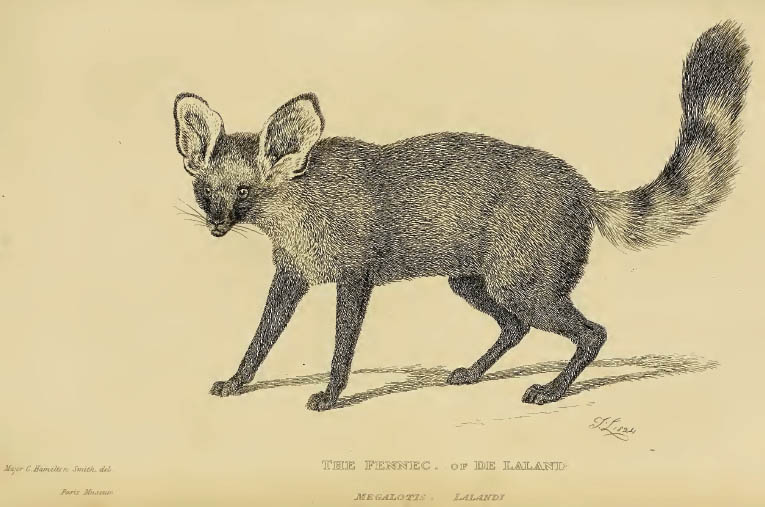

| Fennec of Delaland | 372 |

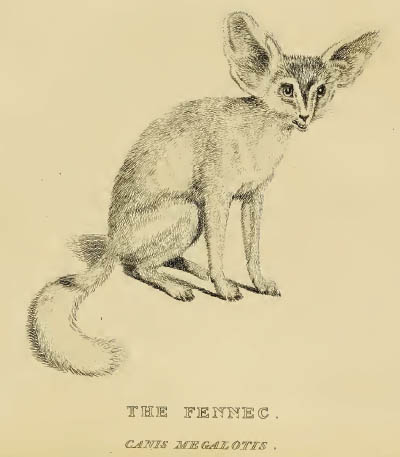

| Fennec | 374 |

| Hyæna Dog | 376 |

| Civet | 378 |

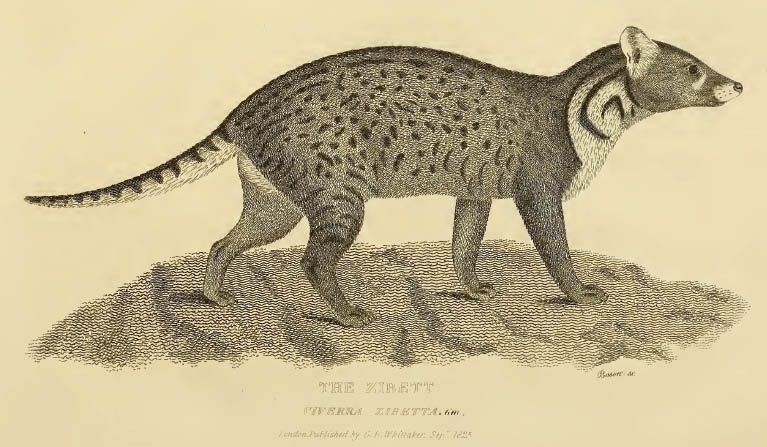

| Zibett | 381 |

[page break]

| Hyæna Genet | 390 |

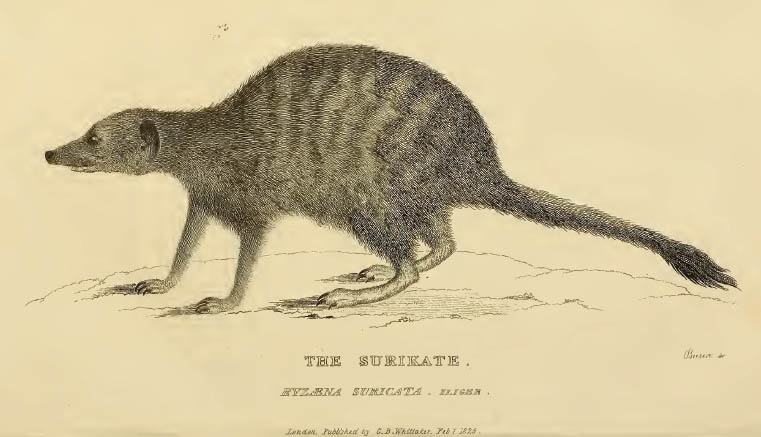

| Suricate | 399 |

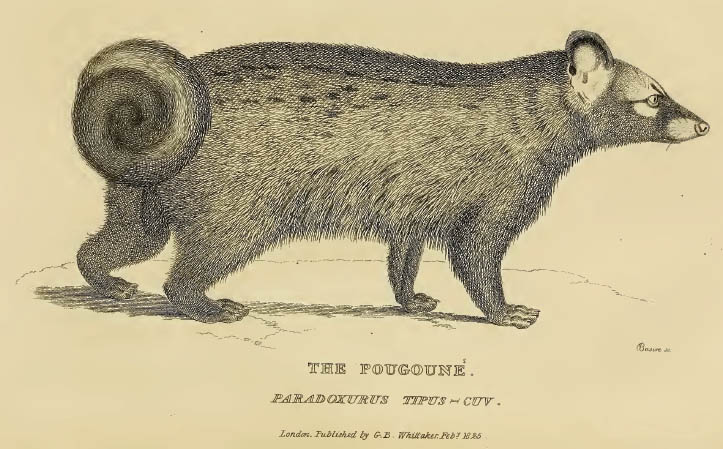

| Pougonné | 412 |

| Binturong | 417 |

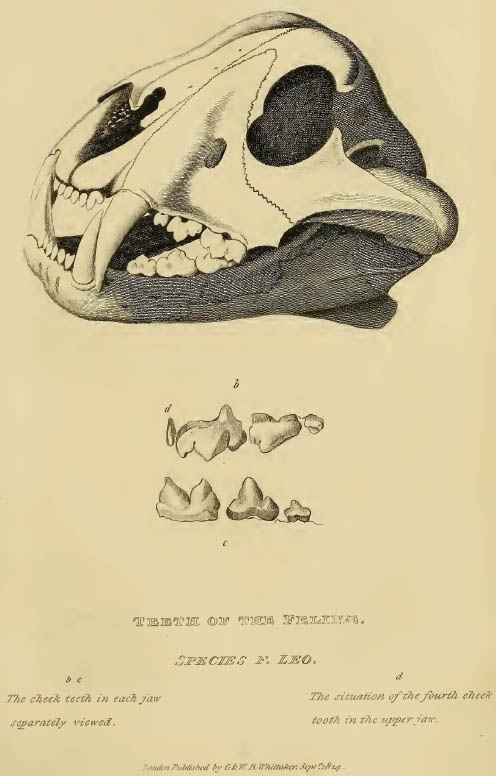

| Teeth of Felinæ | 422 |

| Lion | 428 |

| Tiger | 440 |

| White Tiger | 444 |

| Cubs bred between Lion and Tiger | 447 |

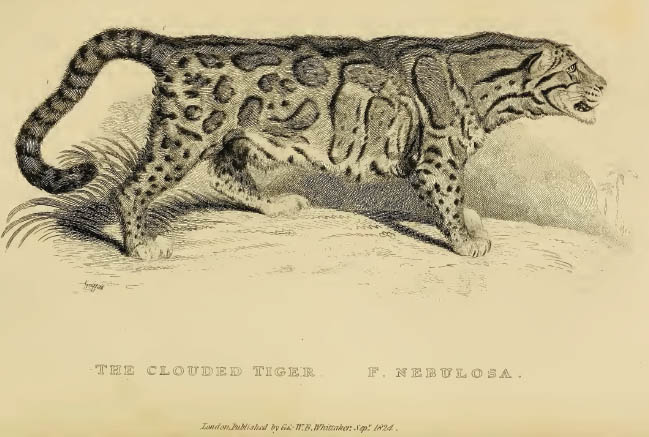

| Clouded Tiger | 450 |

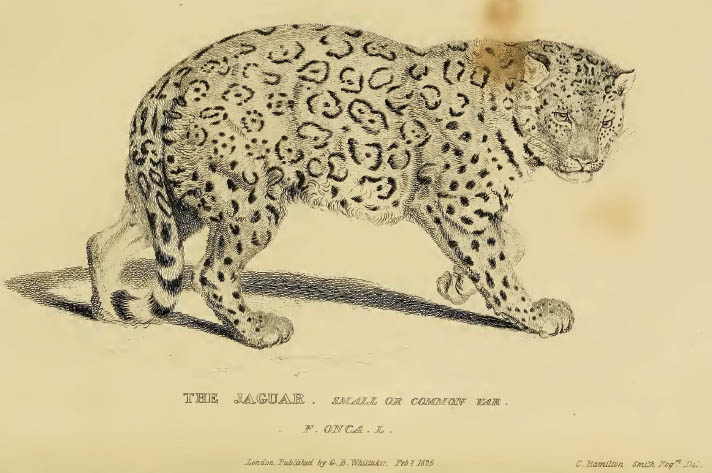

| Jaguar | 455 |

| Jaguar, small var | 456 |

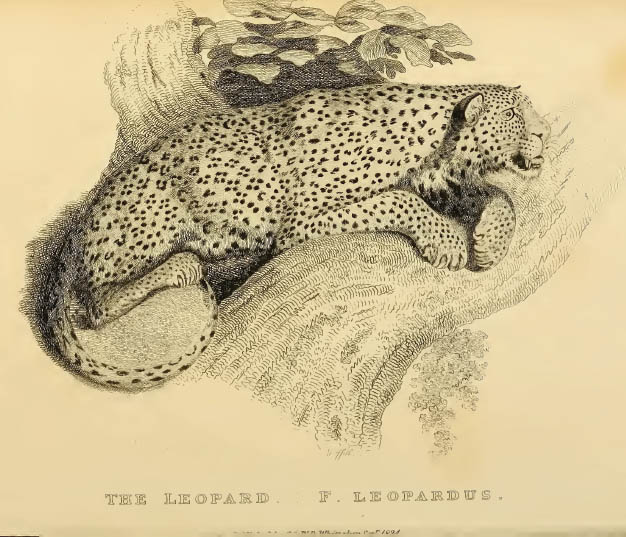

| Leopard | 459 |

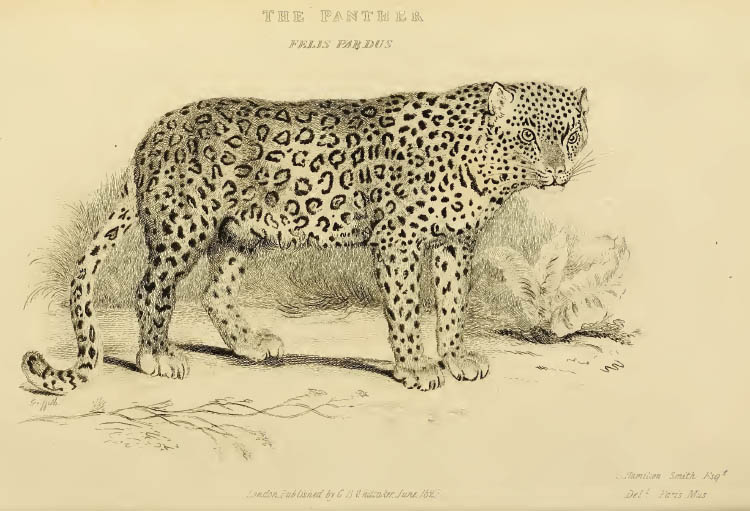

| Panther | 465 |

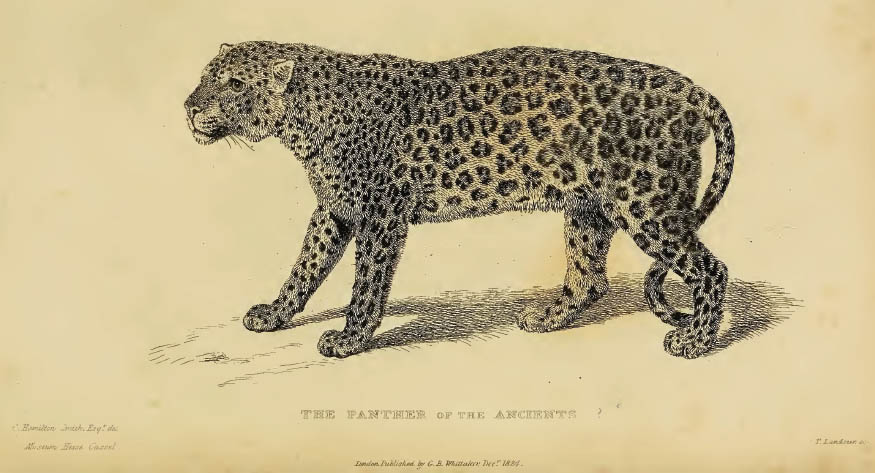

| Panther of the Ancients | 466 |

| Once | 469 |

| Felis Chalybeata | 473 |

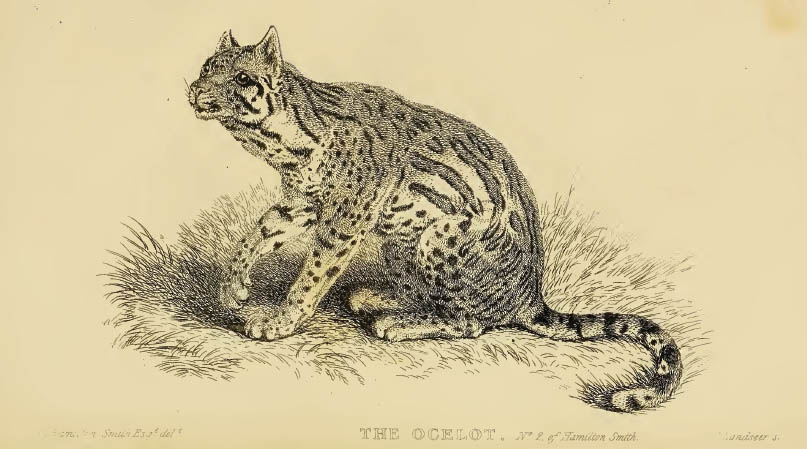

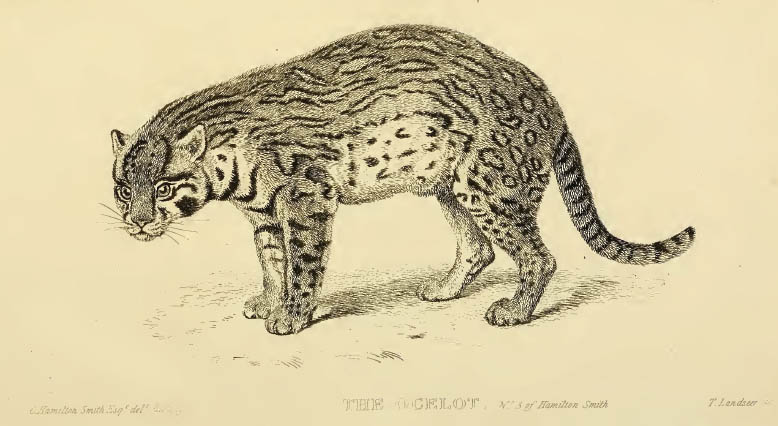

| Ocelot, No. 1. | 475 |

| Ocelot, No. 2. | 476 |

| Ocelot, No. 3. | 477 |

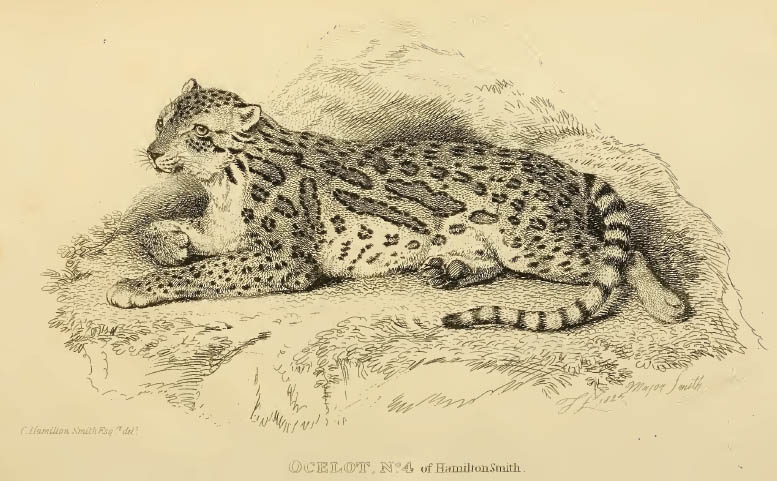

| Ocelot, No. 4. | 477 |

| Linked Ocelot | 478 |

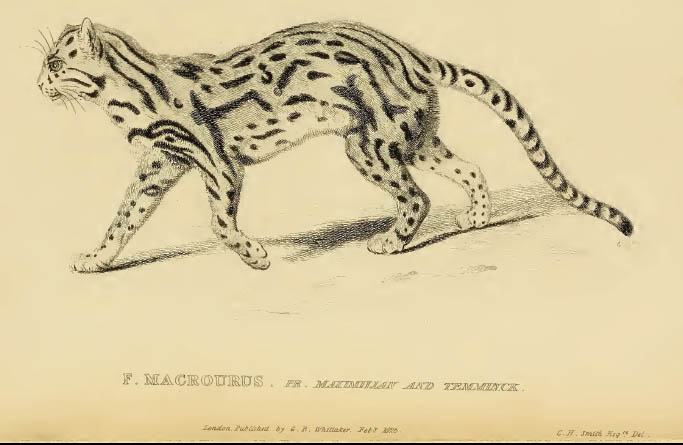

| Felis Macrourus | 478 |

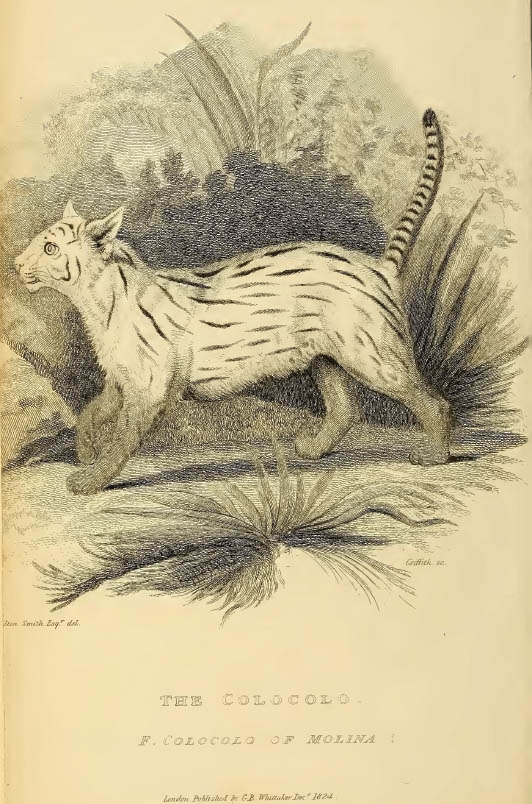

| Colocolo | 479 |

| Chati | 480 |

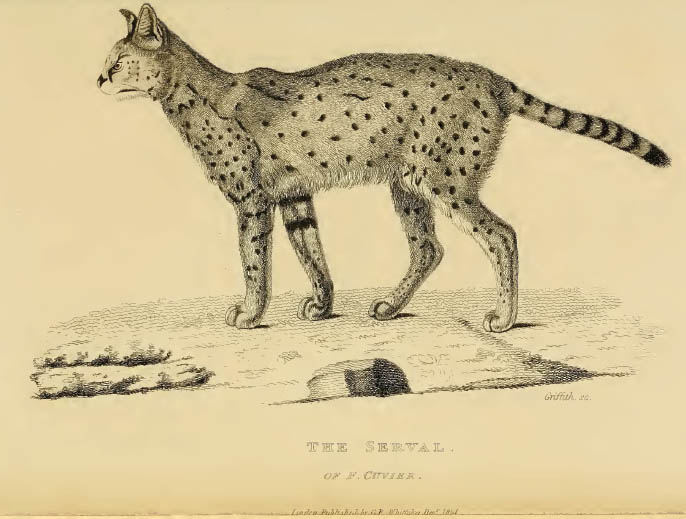

| Serval | 482 |

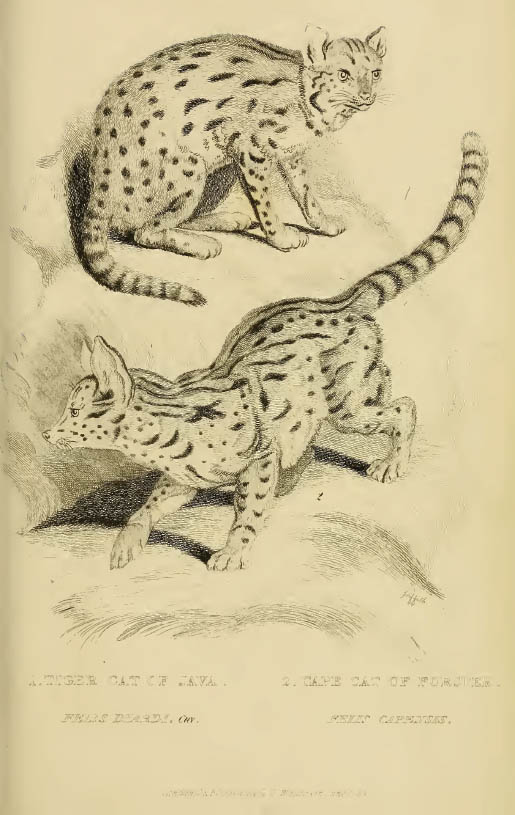

| Tiger Cat of Java and Cape Cat of Forster | 484 |

| Cape Cat of Forster and Yagaroundi | 486 |

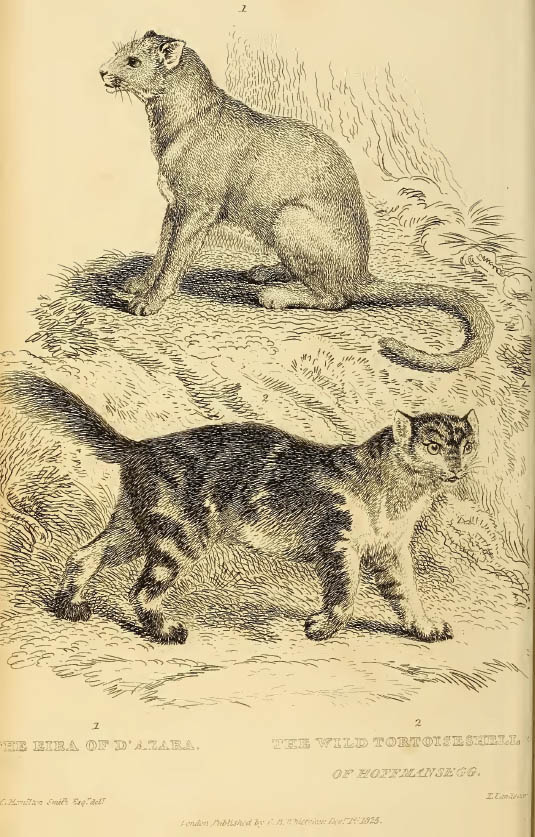

| Eira of D'Azara and Tortoishell Cat | 487 |

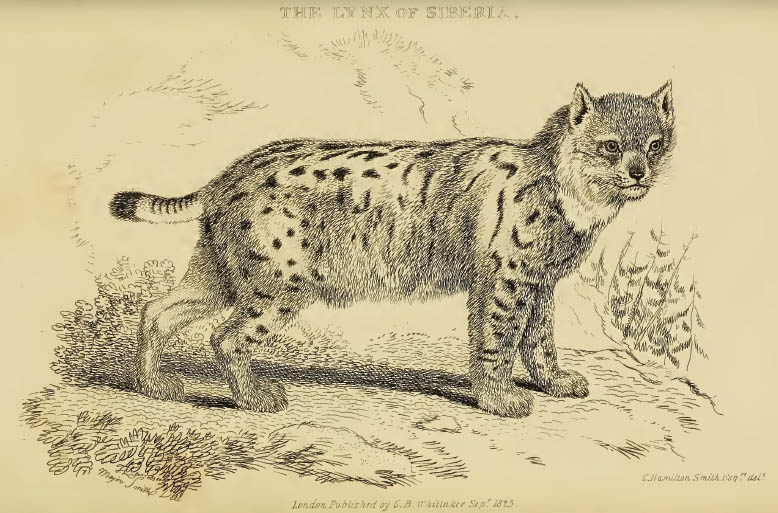

| Lynx of Siberia | 494 |

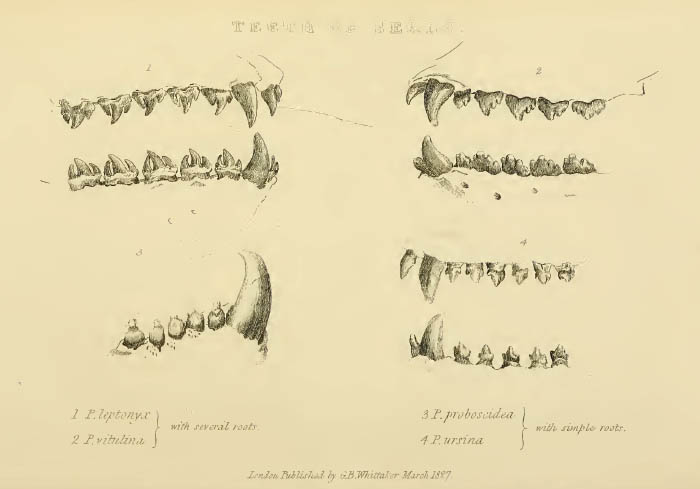

| Teeth of Seals | 497 |

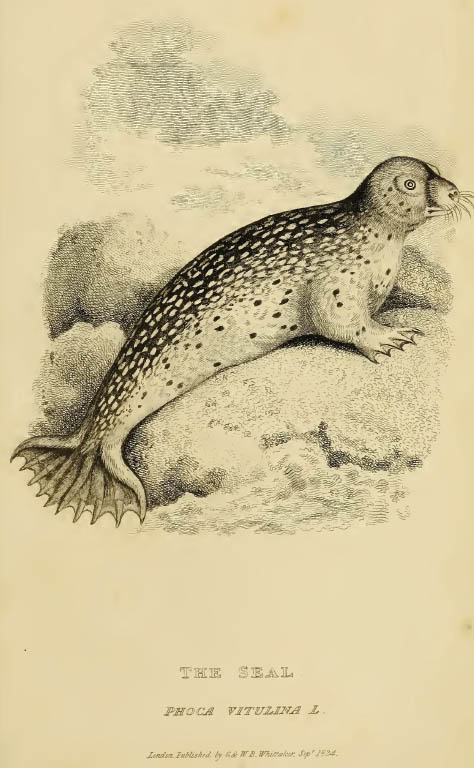

| The Seal | 498 |

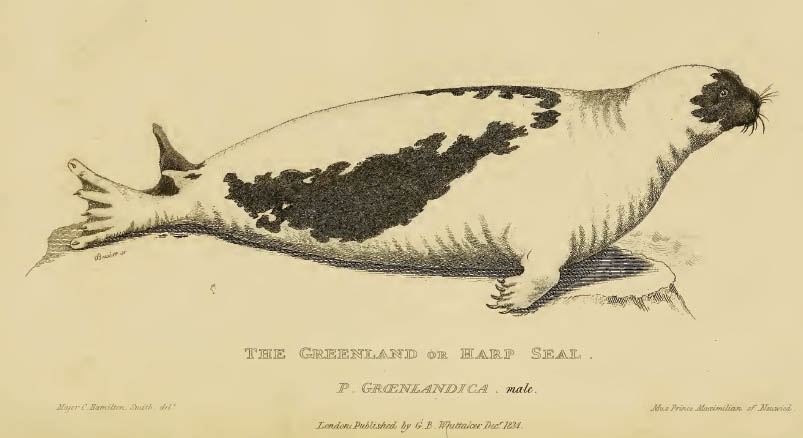

| Greenland or Harp Seal | 506 |

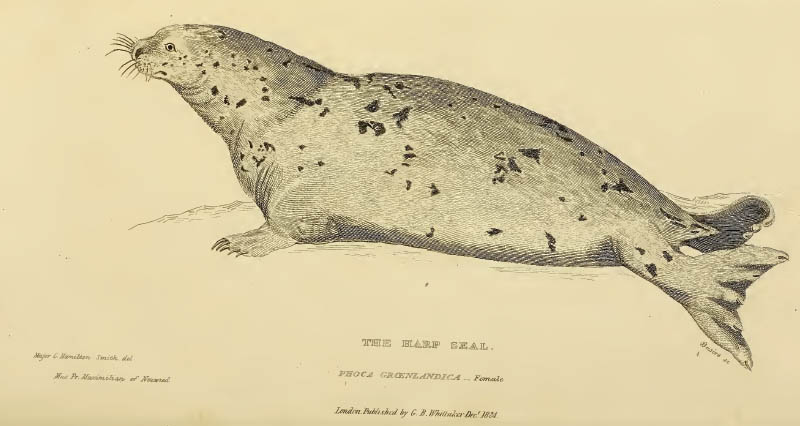

| Harp Seal | 507 |

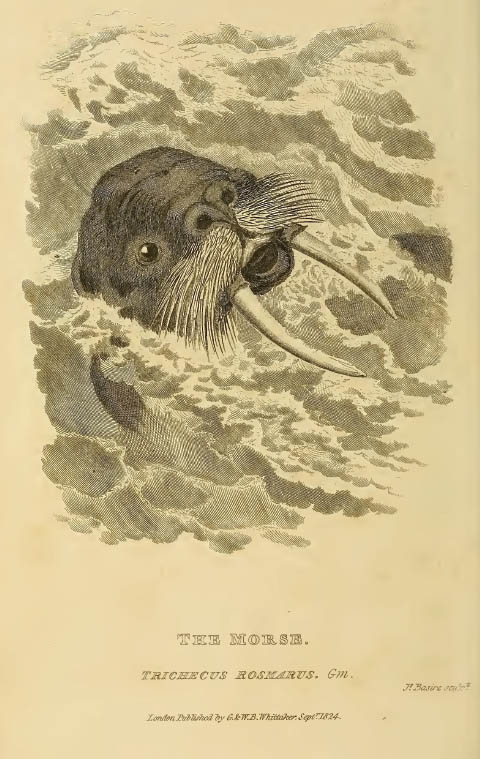

| Morse | 511 |

Erratum in Plates.

In Plate of "Teeth of the Felinæ," the letter d, referring to the fourth cheek tooth in the upper jaw, should have been placed over the first tooth on the LEFT instead of the RIGHT.

[page 1]

THE

THIRD ORDER

OF THE

MAMMALIA.

THE CARNASSIERS.

THESE form a considerable and very various assemblage of unguiculated quadrupeds, which, like man and the quadrumana, possess the three kinds of teeth. They all subsist on animal matter, and more exclusively so in proportion as their cheek-teeth are more of a trenchant character. Such of them as have these teeth altogether or in part tuberculous, also take more or less of vegetable substances, while those who have them bristling with conical points, principally subsist on insects. The articulation of their lower jaw, directed cross-wise, and clasping like a hinge, does not allow of any horizontal motion; it can only shut and open.

Their brain, although tolerably furrowed, has no third lobe, nor does it form a second covering for the cerebellum in these animals any more than in the families which succeed them. The orbit is not separated from the fossa temporalis in their skeleton. Their cranium is narrow, and the zygomatic

VOL. II. B

[page] 2

arcades are dispersed, and elevated, to give more volume and force to the muscles of their jaws. The predominant sense with these animals is that of smelling, and the pituitary membrane is usually extended over very numerous bony laminæ. Their fore-arm can turn, but with less facility than in the Quadrumana, and they have no thumbs on the forefeet opposable to the other fingers. Their intestines are less voluminous, in consequence of the substantial nature of their aliments, and to avoid the putrefaction that flesh must undergo if it remained for any time in an elongated canal.

In other particulars their forms and the details of their organization vary considerably, and produce analogous varieties in their habits to such a degree as to render it impossible to range their genera upon a single scale. We are therefore obliged to divide them into several families, which are variously connected together by very numerous relations.

THE FIRST FAMILY OF THE CARNASSIERS.

The CHEIROPTERA

Have still some affinity with the Quadrumana by the pendulous penis, and the mammæ situated on the breast. Their distinctive character consists in a fold of skin extended between their fore-feet and their fingers, which sustains them in the air, and even enables them to fly, when the hands are sufficiently developed for that purpose. This arrangement demanded powerful clavicles and large shoul-

[page] 3

der-blades to give the shoulder the requisite degree of solidity; but it was incompatible with the rotation of the fore-arm, which would have weakened the force of the impetus necessary for flight. All of these animals have four large canine teeth, but the number of the incisors vary. They have long been divided into two genera according to the extent of their organs of flying; but the first of these two requires many subdivisions.

The BATS (Vespertilio, Linn.)

Have the arms, the fore-arms, and the fingers extremely elongated, and those with the membrane which fills up the intervals between them, form real wings, as much extended as those of birds. Accordingly the bats fly to a considerable height and with great rapidity. Their pectoral muscles possess a thickness proportioned to the movements which they are designed to execute, and in the middle of the sternum is a ridge like that of birds, to form a point of attachment for these muscles. The thumb is short and armed with a hooked nail, which these animals make use of to hang by and to creep. Their hind-feet are weak, divided into five toes of equal length and all of them are armed with nails. There is no cæcum to their intestines. Their eyes are extremely little, but their ears are often remarkably large; and, together with their wings, form an enormous extent of membranous surface. This is almost naked, and so sensible, that the bats can di-

B2

[page] 4

rect themselves into all the nooks of the labyrinth in which they nestle, even after their eyes have been taken out, probably by the diversity of impulsions from the external air. They are nocturnal animals, and in our climates pass the winter in a lethargic state. During the day they remain suspended in obscure retreats. They generally have two little ones at a birth, which they hold clinging to their breasts, and the size of which is very considerable in proportion to that of their mother.

This genus is very numerous, and contains several subdivisions.

At first they must be divided into

The ROUSSETTES, (Pteropus, Briss.)

Which have sharp incisors in each jaw, and cheek-teeth with flat crowns, or more properly with two longitudinal and parallel projections, which are separated by a furrow, and wear away in course of time by attrition. From this conformation, as it might naturally be presupposed, they subsist principally upon fruits. They are, however, sufficiently dexterous in the pursuit of birds and the smaller quadrupeds. These are the largest of the bat-kind, and their flesh is used for food. Their habitat is the East Indies.

The membrane in this subdivision is sloped to a considerable depth between the legs. There is scarcely any tail. The fore-finger, about one half shorter than the middle, has a third phalanx and a little nail which is wanting in the other bats: but

[page] 5

the other lingers have only two phalanges. The nose is simple, the ears small, and without parotides, and the tongue furnished with prickles, bent backwards. The stomach is a sack considerably elongated and unequally inflated.

1. ROUSSETTES without tails, with four incisors in each jaw.

The Black Roussette, (Pterop. edulis, Geoff.)

Of a brownish black, deeper in the under parts. Near four feet from the extremity of one wing to that of the other. An inhabitant of the Sunda and Molucca islands, where these animals conceal themselves in caverns. The flesh is remarkably delicate.

The Roussette of Edwards, (Pter. Edwardsii, Geoff.)

Fawn-colour, with the back of a deep brown. Habitat, Madagascar.

The Roussette of Buffon, (Pterop. vulgaris, Geoff.) Buff. X. XIV.

Brown, the face and sides of the back fawn coloured. From the Isles of France and Bourbon, where they inhabit the trees in the forests.

The Collared Roussette. Rougette of Buffon. (Pter. rubricollis, Geoff.) Buff. X. XVII.

Greyish brown, the neck red. From the same isles, where it lives in the hollow trees.

[page] 6

2. ROUSSETTES with a small tail: four incisors in each jaw.

These comprehend all the species described for the first time by M. Geoffroy. One of them, woolly and grey, (Pter. Ægyptiacus,) lives in Egypt in the catacombs, vaults, &c. Another of a reddish hue, with a tail somewhat longer, and to a certain extent involved in the membrane, (Pter. Amplexicandus,) Geoff. Ann. Mus. t. XV. pl. IV., comes from the Archipelago of the East Indies, &c. To these may be added, the Pteropus Griseus, Geoff. Ann. Mus. tom. XV. pl. VI.; Pteropus Stramineus, Seb. I. LVII. 1, 2,; Pteropus Marginatus, Geoff, loc. cit. pl. V.; Pteropus Minimus, id.

3. Following the relations pointed out by M. Geoffroy, we shall moreover separate from the Roussettes the Cephalotes, which have cheek-teeth of the same character, but in which the index or fore-finger, though short and furnished like the preceding species with three phalanges, is, however, without a nail. The membranes of their wings, instead of being joined to the flanks, are both of them united together on the middle of the back, to which they adhere through the medium of a vertical and longitudinal partition. Very frequently they have but two incisors.

The CEPHALOTES of Peron, (Cephalotes Peronii, Geoff.) Geoff. Ann. Mus. XV. pl. IV.

Brown or red. Habitat, Timor.

When the Roussettes have been thus detached,

[page] 7

there will remain the genuine bats, which are all insectivorous, and all of which have cheek-teeth furnished with conical points. The index is never provided with a nail; and, with the exception of a single sub-genus, the membrane always extends between the two legs.

They must be divided into two principal tribes. The first has upon the middle finger of the wing three ossified phalanges, but the other fingers, and the index itself has but two.

To this tribe, which is altogether foreign, belong three sub-genera.

The MOLOSSI, (MOLOSSUS, Geoff. Dysopes, Illiger.)

Have a simple muzzle; ears large and short, originating from the angle of the lips, and uniting one to the other upon the muzzle; the parotis short, and not enveloped by the conch. We reckon but two incisors in each jaw. Their tail takes up the whole length of the interfemoral membrane, and often extends beyond it. All the species come from America, and are more or less brown. They were confounded by Gmelin under the common name of Vespertilio Molossus, but M. Geoffroy has already distinguished nine species, of which Buffon has only three, viz., the Molossus longicaudatus, the Molossus fusciventer, and the em>Molossus Guyanensis. The description of the others will be found in the Ann. du Mus. VI. 150.

The NYCTINOMES (Geoff.)

Have four incisors below; the upper lip is high, and

[page] 8

considerably sloped. In other particulars, they resemble the Molossi. To these belong the Nyctinome of Egypt, Geoff. Eg. mammif. 2, 2; Vespertilio acetabulosus, Herm. Obs. Zool. p. 19; Vespertilio plicatus, Buchannan.

The STENODERMES, (Geoff.)

The muzzle is simple, the interfemoral membrane sloped as far as the coccyx. The tail is wanting, and there are two incisors above and four below.

The NOCTILIONS, (Noctilio, Linn. Ed. XII.)

With a short muzzle, inflated, divided, and marked by warts and curious furrows. The ears are separated. They have four incisors above and two below. The tail is short, and unconnected above the interfemoral membrane.

There is but one species known, which belongs to America, and is uniformly of a pale fawn-coloured tint.

The PHYLLOSTOMES, (Phyllostoma, Cuv. and Geoff.)

The regular number of incisors is four in each jaw, but from the lower some of these teeth frequently drop out, being pushed aside by the growth of the canines. These animals are also distinguished by the membrane which, in the form of an upturned leaf, crosses the termination of their noses. The tragus of their ear resembles a little leaf, more or less indented. The tongue, which is capable of great

[page] 9

elongation, is terminated by papillæ, which seem to be arranged so as to form an organ of suction, and their lips also are provided with tubercles symmetrically disposed. All this tribe is American; they run on the earth with more facility than the other bats, and are accustomed to suck the blood of other animals.

1. PHYLLOSTOMES without a tail.

The Vampire, (V. Spectrum, L.) Andira Guaç of Brasil. Seb. LVIII. Geoff. Ann. Mus. XV. XII. 4.

The leaf is oval and hollowed in the form of a tunnel. This animal is reddish brown and about the size of a magpie. Habitat, South America. It has been accused of destroying men and animals by sucking their blood. But the truth appears to be, that it inflicts only small wounds, which may probably become inflammatory and gangrenous from the influence of the climate.

We may here add the Lunette, (Vespertilio perspicillatus, L.) spear-nosed bat. And three species given after Azzara, by M. Geoff. Ann. du Mus. XV. 181, 182.

2. PHYLLOSTOMES, with a tail involved in the interfemoral membrane.

Javelin Bat, (Vesp. Hastatus, L.) Fer de Lance, Buff. XIII. XXXIII.

The membrane of the nose very much resembles a javelin, or leaf of trefoil.

[page] 10

Here may be added Vespertilio Loricinus, (Anglicè leaf-nosed bat), Pall. Spic. Zool. fasc. III. pl. III. IV., cap. Schreb. XLVII.

3. PHYLLOSTOMES, with a tail unconnected above the membrane.

The indented Javelin Bat, (Ph. crenulatum, Geoff.)

The leaf of the nose is formed like a javelin, indented or furrowed at the side.

The second great tribe has but one ossified phalanx on the index, and the other fingers have each of them two.

This tribe is also divided into numerous subgenera.

The MEGADERMES, (Geoffr. Ann. du Mus. XV.)

These bats have on the nose a leaf more complicated than that of the Phyllostomes. The parotis is large, and most frequently forked or cloven; the shells or conchs of the ear are extremely ample and are united to each other on the summit of the head; the tongue and lips are smooth; the interfemoral membrane is entire, and there is no tail. They have four incisives below, but none have as yet been discovered above, and it would appear that their intermaxillary bone remains cartilaginous.

They all belong to the ancient continent, and are either African, as the Feuille (Mega. Vons. Geoffr.), with an oval leaf to the nose, almost as large as the head: of Senegal, or of the Indian Archipelago, as

[page] 11

the Spasm of Ternata (Vespert. Spasma, L. Seb. I. LVI.). The Lyre, Geoffr. Ann. Mus. XV. pl. XII. The Treffe of Java, Seb. ib. &c. The species are interdistinguished by the form of their leaves, like the Phyllostomes.

The RHINOLPHI (RHINOLPHUS, Geoffr. et Cuv.) vulgarly Horse-shoe Bats.

They have the nose furnished with membranes and crests exceedingly complicated, which are couched upon the forehead, and present in the gross the figure of a horse-shoe. The tail is long and placed in the interfemoral membrane. They have four incisives below, and two very small ones above, situated in an intermaxillary cartilaginous bone.

There are two species, very common in France, and discovered by Daubenton.

The Great Horse-shoe Bat (Vesp. Ferrum equinum, L.) Buff. or Rhinolphus bifer, Geoffr. Ann. Mus. XX. pl. V. and The Lesser (Vesp. hipposideros, Bechot.) Buffon VIII. XVII. 2, and XX. Geoffr. loc. cit.

They inhabit the quarries, remaining there isolated, suspended by the feet, and enveloped in their wings, so as to suffer no other part of their bodies to become visible*.

The NYCTERES (NYCTERIS, Cuv. et Geoffr.)

The forehead is hollowed by a small indenture

* Add the four other species represented. Geoff. Ann. Mus. XX. pl. V., one of which is the Vesp. Spcoris, Selin,

[page] 12

which is marked even upon the cranium, and the nostrils are surrounded by a circle of projecting laminæ. They have four incisors, without any interval above, and six below. Their ears are large, not joined, and their tail is comprised in the interfemoral membrane. These species belong to Africa. Daubenton has described one of them (Vesp. hispidus, Linn.) Bearded Bat. M. Geoffroy has found others in Egypt*.

The RHYNOPOMES (Geoffr.)

Have an indenture not so strongly marked, the nostrils at the end of the muzzle, and a small lamina above: their ears are joined, and their tail extends considerably beyond the interfemoral membrane. One species of this subgenus is known: it belongs to Egypt, and chiefly inhabits the pyramids †.

The TAPHIENS (THAPHOZOUS, Geoffr.)

Have also a small foss or indenture on the forehead; but the nostrils are devoid of the elevated laminæ, and they have but two incisors above and four below. Their ears are separated, and their tail free above the membrane. M. Geoffroy has discovered a species in the catacombs of Egypt ‡.

* Nyctere of Thebais, 29, Mammif. I. 2, 2.

† Rhinopome Microphyle, Geoff. Vespertillio Microphyllus, Schr.

‡ The Taphien Filet. Eg. Mamif. I. 1.1. The perforated Taphien, ib. III. L. the Vesp. lepturus.

[page] 13

The COMMON BATS (VESPERTILIO, Cuv. et Geoffr.)

Have the muzzle without leaves or other distinctive marks, the ears separated, four incisors above, separated into couples, and six below sharp-edged, and triflingly notched. The tail is comprised in the membrane. This sub-genus is the most numerous of all. Its species are to be found in every quarter of the globe. Six or seven are enumerated in France. The first has been known for a long period.

The ordinary Bat (Vesp. murinus, Linn.) Buff. VIII. XVI.

Grey, with oblong ears the length of the head. The other species have been discovered only by Daubenton.

The Serotine (Vesp. Serotinus, Linn.) Buff. VIII. XVIII. 2.

Fawn-colour, wings and ears blackish: the shell or conch of these is triangular and shorter than the head; the parotis pointed.

They are frequently found beneath the roofs of churches, and other unfrequented buildings.

The Noctule (V. Noctula, L.) Buff. VIII. XVIII. 1.

Brown, triangular ears, shorter than the head, parotis rounded. A little smaller than the preceding. Found in the hollows of old trees, &c.

The Pipistrelle (V. Pipistrellus, Gm.) Buff. VIII. XIX. 1.

The smallest species found in this country: brown, with triangular ears and parotis.

[page] 14

M. Geoffroy further separates from the Vespertiliones, or Common Bats,

The OREILLARDS or Great-eared Bats (PLECOTUS, Geoffr.)

Whose ears, larger than the head, are united to each other on the cranium, as is the case with the Megadermes, the Rhinopomes, &c.

The common species (Vesp. Auritus, L.) Buff. VIII. XVII. 1, is still more common here than the ordinary Bat. Its ears are nearly equal in size to its whole body. It inhabits the houses, kitchens, &c. We have another species discovered by Daubenton, called the Barbastelle (Vesp. Barbastellus, Gm.) Buffon VIII. XIX. 2. Brown, with ears much smaller.

The GALEOPITHECI (GALEOPITHECUS, Pall.) commonly Flying Cats,

Differ generically from the bats, because the fingers of their hands, all furnished with trenchant nails, are not more elongated than those of the feet; so that the membrane which occupies their intervals, and extends as far as the sides of the tail, can do little else than perform the functions of a parachute. Their canine teeth are indented and short, like the molars. Above are two incisors, also indented, and considerably separated from each other. Below are six cut into narrow divisions, like combs, a structure altogether peculiar to this genus. These animals live in trees in the Indian Archipelago, and pursue

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 15

insects there, and probably birds. If we may judge by the detrition which their teeth suffer in age, they would appear to subsist also on fruits. They have, a large cæcum.

We know but one species distinctly, the fur of which above is reddish grey, red below, varied and radiated with different greys in youth. This is the Lemur volans, Linn. Audeb. Galœop, pl. I. et II. It inhabits the Moluccas, the Sunda Islands, &c.

All the other Carnassiers have the teats situated under the belly.

THE INSECTIVORA,

Which form the second Family,

Have, like the Cheiroptera, cheek-teeth, with conical points, and lead a nocturnal or subterraneous life. They principally subsist on insects, and in cold countries pass the winter in a lethargic state. They do not possess lateral membranes like the bats, but notwithstanding this they are never destitute of clavicles. Their feet are short, and their motions feeble. The teats are situated under the belly, and the penis in a case. They have no cæcum, and all of them lean the entire sole of the foot on the ground in walking.

There are two small tribes of these, distinguished by the position and the relative proportion of their incisors and canine teeth.

The first have two long incisors in front, followed

[page] 16

by other incisors and canine teeth, all shorter than the molar. This kind of dentition, of which the Tarsiers, among the quadramana, have already furnished us with an example, approximates these animals in some degree to the rodentia.

The HEDGEHOGS (ERINACEUS, Lin.)

Have the body covered with prickles instead of hairs. The skin of their back., in bending the head and paws towards the belly, can close itself as if in a purse or bag, and present its prickly points on all sides to the adversary. The tail is very short, and all the feet have five toes. The two middle superior incisives are separated and cylindrical.

The common Hedgehog (Erinaceus Europœus) Buff. VIII. VI.

With short ears; sufficiently common in the woods and hedges; passes the winter in its burrow, and sallies forth from it in the spring, with the vesiculae seminales in a state of the most incredible amplitude and complication. To the insects which form its ordinary regimen it adds the fruits which to a certain age wear off the points of its teeth. Its skin was formerly made use of to hatchel hemp.

The Long-eared Hedgehog (Erinaceus Auritm.) Schreb. CLXIII.

Smaller than the common hedgehog, with ears as

[page] 17

large as two-thirds of the head; in other respects, like ours in form and habits. It is found from the north of the Caspian Sea as far as Egypt*.

The SHREWS (SOREX, Lin.)

Are animals generally much smaller than the hedge-hogs, and covered with simple hairs instead of prickles. On each flank, under the ordinary skin, is found a little band of stiff and close hairs, from which distils an odoriferous humour, produced by a peculiar gland.

The two middle incisors of the upper row are crooked and indented at the base. They remain in holes which they dig in the earth, seldom going out till towards evening, and live on worms and insects. But one species has for a long time been remarked in France.

The common Shrew, or Musette (Sorex Araneus, Lin.) Buff. VIII. X. I.

Gray, with a square tail as long as the body. They are found in considerable numbers in the country, in the meadows, &c. They have been accused of causing a malady among horses by their bite; but this imputation is false, and has probably originated in the fact, that though cats

* Pallas has remarked, as an interesting fact, that hedgehogs eat hundreds of cantharides with impunity, while a single one will cause such horrible torments to cats and dogs.

Vol. II. C

[page] 18

will kill these animals readily, they refuse to eat them, in consequence of their powerful odour.

Daubenton has made known another species.

The Water Shrew. (Sorex Fodiens, Gm.) Buff. VIII. XI.

Black above, white underneath; squared tail, as long as the body. When it plunges in the water the ear is almost hermetically sealed by means of three small valves which correspond with the helix, the tragus, and the antitragus. The small stiff hairs which border the feet afford it the facility of swimming, and accordingly its favourite haunts are the banks of rivulets.

Herman, M. Gall, and M. Geoffroy, have added some other species.

The DESMANS (MYGALE, Cuv.)

Differ from the shrews by two very small teeth, placed between the two large incisors below, and also by having the two upper incisors of a triangular form, and somewhat flattened. The muzzle is lengthened into a very small and flexible snout, which is in a state of continual agitation. Their long tail, scaly and flattened at the sides, and their feet with five toes all united together by membranes, constitute them aquatic animals. Their eyes aie very small and they have no external ears.

The Desman of Russia, vulg. The Russian Musk Rat. (Sorex Moschatus, Lin.) Buff. X. I.

Almost as large as a hedgehog, of an ashy-gray;

[page] 19

very common along the rivers and lakes of Southern Russia. It subsists on worms, on the larvæ of insects, and more especially on leeches, which it easily draws out of the mud with its mobile snout. Its burrow, dug within the bank, commences under the water, and is raised in such a manner that the bottom remains above the level in the largest waters. This animal does not come voluntarily to dry land, but is often taken in nets. Its musky odour arises from a sort of pommade, secreted in small follicles under the tail. This odour is communicated even to the flesh of pikes, which prey upon these animals.

A small species of this genus has been discovered in the streams of the Pyrenees, and made known by M. Geoffroy. Ann. du Mus. tom. XVII. pl. IV. f. I.

The SCALOPES (SCALOPS, Cuv.)

Unite to the teeth of the Desmans, and to the simply pointed muzzle of the Shrews, large hands, armed with strong nails, fitted for digging into the earth, and entirely similar to those of moles. Accordingly they lead the same sort of life.

The only species known is

The Scalope of Canada (Sorex aquaticus, Lin.). Schreb. CLVIII.

Appears to inhabit a considerable portion of North America along: the banks of rivers.

C 2

[page] 20

The CHRYSOCHLORES (CHRYSOCHLORIS, Lacep.)

Have, as well as the two preceding genera, two incisors above and four below; but the muzzle is short, large, and elevated, and their fore-feet have but three nails, of which the outer one is very large and the others diminish in proportion. The hind-feet have five nails. These are also subterraneous animals, and their fore-arm is supported, for the purposes of digging, by an additional bone placed under the cubitus.

The Chrysochlore of the Cape, vulg. Golden Mole. (Talpa Asiatica, Lin.) Schreb. CL VII., and better, Brown, III. XLV.

Somewhat less than our moles, without apparent tail. The only quadruped known which presentsany shade of those beautiful metallic reflections, which glitter in such a variety of birds, fishes, and insects. Its fur is green, changing to the colour of brass or bronze. Its ears have no conque, and its eyes are not perceptible*.

The second tribe of insectivora have four large

* The Red Mole of America, in Seba, I. pl. XXXII. f. 1, (talpa rubra, L.) is probably of this genus; but the tucan of Fernandes, ap. XXIV., which is confounded with it, appears rather a rat-mole, by its long teeth in each jaw, and its vegetable regimen. It is probably to this first tribe of insectivora that the long-tailed mole belongs. Penn. arct. Zool. No. 68; but its dentition is not sufficiently known to fix its place with accuracy.

[page] 21

canine teeth separated from each other, between which are small incisives, which is the most ordinary arrangement with the quadrumana and the carnassiers.

We find in this subdivision forms and habits analogous to those of the preceding tribe. Thus,

The TENRECS, Cuv. (CENTENES, Illig.)

Have the body covered with prickles like the hedge-hogs; but, not to mention the great difference of their teeth, the tenrecs do not possess the faculty of rolling themselves up in a globular form. They have no tail, and the muzzle is remarkably pointed. Three species have been found in Madagascar, the first of which has been naturalized in the Isle of France. They are nocturnal animals, and pass three months of the year in a torpid state, although inhabitants of the torrid zone. Bruguière assures us that it is even during the greatest heats that they sleep in this manner.

The Tenrec (Erinaceus Ecaudatus, Lin.) Buff. XII. LVI.

Covered with stiff prickles. Incisors sloping, and but four in number in the lower jaw. This is the largest of the three, and surpasses our hedgehog.

The Tendrac, (Erinaceus Setosus, Lin.) Buff. XII. LVII.

With more flexible prickles, more resembling hairs. Six sloping incisors in each jaw.

II *

[page] 22

The radiated Tenrec, (Erinaceus Semispinosus.)

Covered with hairs and prickles intermingled, radiated with yellow and black. Its incisors to the number of six, and the canines are slender and crooked. It is scarcely the size of a mole.

The MOLES, (TALPA., Lin.)

Are universally known by their subterraneous mode of existence, and their conformation eminently adapted to this kind of life.

An arm remarkably short, attached by a long shoulder-blade, supported by a vigorous clavicle and provided with enormous muscles, carries a hand extremely large, the palm of which is always turned upwards or behind. This hand is trenchant at its inferior edge: the fingers are distinguished with difficulty, but the nails which terminate them are long, strong, broad, and trenchant. Such is the instrument employed by the mole to tear the earth and push it back. The sternum, like that of birds and bats, has a ridge which gives to the pectoral muscles the magnitude necessary for their functions. To pierce the earth and throw it up, the mole uses its elongated and pointed head, the muzzle of which is armed at the end with a peculiar small bone. The cervical muscles are exceedingly vigorous, and the cervical ligament is even completely ossified. The hinder part of the mole is feeble, and the motions of the animal on the earth are as constrained and painful as they are rapid and vigorous below its surface. The sense of hearing

[page] 23

in these animals is extremely fine, and the tympanum remarkably large, though the external ear is wanting. The eye, however, is very small, and so much concealed by the hair, that its very existence was for a long time denied. The jaws of the mole are feeble, and its nutriment consists of insects, worms, and some tender roots. This tribe have six incisives above and eight below.

Our Common Mole, (Talpa Europœa, Lin.) Buff. VIII. XII.

Pointed muzzle, hair fine and black. Some individuals are found white, fawn-coloured, and pied. This animal is extremely troublesome from the derangement it causes in cultivated grounds.

The Star-muzzled Mole of Canada, (Talpa cristata, Sorex cristatus, Lin*.)

The two nostrils are surrounded with small points, cartilaginous and moveable, which when separated into radii, resemble a kind of star. It is less than our mole, blackish, and the tail, one half shorter than the body, is slightly covered with hair.

THE CARNIVORA

Will form a third family of the Carnassiers.

Though the epithet of Carnassiers is suitable to all unguiculated animals with three sorts of teeth, ex-

* We have satisfied ourselves by the inspection of its teeth that it is a true mole, and not a sorex. It is the condyliera of Illiger; but its characters, taken from the figure of La Faille and Buff, supp. VI. XXXVII., are false.

[page] 24

vigorous below its surface. The sense of hearing cepting the Quadrumana, inasmuch as they all subsist more or less on animal matter, still there are many of them, and especially the two preceding families, which are reduced by their weakness and the conic tubercles of their cheek-teeth, to live almost entirely on insects. It is in the family now before us that the sanguinary appetite is united with sufficient force to give it due effect. These animals have always four large and long canine teeth separated, and between them six incisives in each jaw, the second of which in the lower row has always its root more deeply seated than the rest. The molars are always either altogether trenchant or but partly mingled with blunt tubercles, and never bristling with conic points.

These animals are more exclusively carnivorous in proportion as their teeth are more completely trenchant, and their regimen may be nearly calculated from a comparison of the extent of the tuberculous surface of their teeth with the part which is trenchant. The bears which can subsist entirely on a vegetable diet have almost all their teeth tuberculous.

The anterior molars are the most trenchant; then comes a molar larger than the others, which is generally provided with a tuberculous heel of different degrees of magnitude, and behind it are found one or two small teeth entirely flat. It is with these small teeth at the bottom of the mouth that dogs chew the grass which they occasionally swallow. This large molar above, and the corresponding one

[page] 25

below, we shall call, with M. Frederic Cuvier, carnivorous teeth (carnassières), the anterior pointed teeth we shall call false molars, and the posterior blunt ones, tuberculous teeth.

It is easily to be conceived, that the genera which have the fewer molars, and whose jaws are the shortest can bite with the greatest force.

It is on these differences that the genera may be most securely established.

We must however unite to them a consideration of the hind foot.

Many genera, like all those of the two preceding families, rest the entire sole of the foot on the ground in walking or standing upright; and this peculiarity is easily perceived from the absence of hairs under this whole part.

Others, much more numerous, never walk except on the end of their toes, elevating the tarsus altogether. Their course is more rapid, and to this first difference they unite many others in their habits, and even in their internal conformation. Both have no clavicle except a bony rudiment suspended in the flesh.

THE PLANTIGRADES

Form the first tribe which walk on the entire foot, and by this means obtain a greater facility of raising themselves on their hinder legs. They participate in the slowness of motion and the nocturnal life of the insectivora, and, like them, are destitute of a cæcum. Most of the plantigrades which inhabit

[page] 26

cold countries pass the winter in a lethargic state; they have all five toes on every foot.

The Bears (URSUS, Lin.)

Have three large molars on each side in each jaw, entirely tuberculous; accordingly, notwithstanding their extreme strength, they seldom eat flesh except from necessity. The last but one in the upper row stands for the carnivorous tooth (la carnassière). The last, which is the tuberculous, is the largest of all. In front of the three is another pointed molar, and in the interval between it and the canine, one or two very small and simple teeth, which often fall without inconvenience.

These animals are large, clumsy in the body, thick in the limbs, and have a remarkably short tail. The cartilage of their nose is elongated and mobile. They dig caves or construct huts for themselves, where they pass the winter in a state of somnolency more or less profound, and without taking any aliment. It is in this retreat that the female brings forth.

The species are not easily interdistinguished by sensible or obvious characters. We reckon

The Brown Bear of Europe, (Ursus Arctos, Lin.) Buff. VIII. XXXI.

With convex forehead, and brown fur, more or less woolly. Some are seen nearly yellow, others of a sleek and glossy brown, with almost

[page] 27

a silvery reflection. The relative height of their limbs varies equally and without any constant analogy to the age or sex of the individual. The young bears are distinguished by a whitish collar. This animal inhabits the high mountains and large forests of Europe, and of a considerable part of Asia. The time of copulation is in June, and the birth takes place in January. Sometimes these bears lodge very high in trees. Their flesh, when young, is good for eating; but the paws at all ages are esteemed excellent.

Some think that it is possible to distinguish a black Bear of Europe. Those which had been exhibited as such, had a flat forehead, and the fur woolly and blackish, Also there has been mentioned a bear of the Indies, with blackish fur and a white spot on the breast, &c.

A species which we can with more certainty pronounce to be different, is,

The Black Bear of America, (Ursus Americanus, Lin.) Cuv. Menag. du Mus., in 8vo. II. p. 143.

Flat forehead, fur black and glossy, and fawn-coloured muzzle. We have always found in this species the small teeth behind the canine more numerous than in the bear of Europe. It has sometimes a fawn-coloured spot above each eye, and one of white or fawn-colour on the throat or chest. Individuals have been seen entirely fawn-coloured. It lives usually on wild

[page] 28

fruits, often lays waste the fields, and repairs to the sea-coast for the purpose of catching fish when they are in abundance. It seldom attacks quadrupeds but in the want of every other alimentary supply. Its flesh is in estimation.

It is said that there is also in America a gray bear, larger than the black one, but it has not been described with sufficient accuracy.

The White Bear of the Icy Sea, (Ursus Maritimus, Lin.) Cuv. Menage, du Mus. in 8vo. p. 68.

Is another very distinct species, characterized by its elongated and flattened head, and by its white and glossy fur. It pursues the seals and other marine animals. Exaggerated accounts of its voracity have rendered it very celebrated.

The RACOONS (PROCYON, Storr.)

Have three hinder tuberculous molars, and three small pointed molars in front, forming a continued series as far as the canines. The tail is long; but all the rest of their exterior represents that of the bear on a minor scale. They rest the entire sole of the foot upon the ground only when standing; in walking they raise the heel.

The Racoon of the Anglo-Americans, Mapach of the Mexicans. (Ursus Lotor, Lin.) Buff. VIII. XLIII.

Grayish-brown, with a white muzzle, a brown mark across the eyes; the tail ringed with brown and black. An animal about the size of

[page] 29

the badger, easily tamed, and never eating any thing without having first plunged it in the water. It comes from North America; subsists on eggs, insects, birds, &c.

The Racoon Crab-eater, (Ursus Cancrivorus.) Buff. Supp. VI. XXXII.

Of an ashy-brown colour, uniformly clear. The rings of the tail less marked. Habitat, South America.

The COATIS, (NASUA, Storr.)

Join to the teeth, the tail, the nocturnal life and dragging walk of the racoons; a nose singularly elongated and mobile. The feet are demi-webbed, and yet they climb trees. Their long nails serve them for digging. They come from the warm regions of America, and subsist much in the same way as our own martins.

The Red Coati, (Viverra Nasua, Lin.) Buff. VIII. XLVIII.

Reddish fawn-colour. The muzzle and rings of the tail brown.

The Brown Coati, (Viverra Narica, Lin.) Buff. VIII. XLVIII.

Brown, white spots on the eye and muzzle.

We can scarcely introduce more fitly than here the singular genus of the KINKAJOUS or POTTO, Cuv. (Cercoleptes, Illig.), which unites to the plantigrade motion a long and prehensile tail, like that of

[page] 30

the Sapajous, a short muzzle, a slender and extensible tongue; two cheek-teeth in front pointed, and three tuberculous ones behind.

There is known but a single species (Viverra caudivolvula, Gm.), Buff. Supp. III. L., from the warm parts of South America, and some of the great Antilles, where it is named poto. It is as large as a pole-cat, with woolly hair, of a grayish or brownish yellow. Nocturnal, of a disposition rather mild, and capable of subsisting on fruits, honey, milk, blood, &c.

The BADGERS, (MELES, Storr.)

Which Linnæus places like the racoons, in the genus of bears, have a very small tooth behind the canine; then two pointed molars followed above by one which we begin to recognise as the true carnivorous tooth (la carnassière), from the vestige of an edge discovered on its external side. Behind it is a squared tuberculous tooth the largest of all. Below the penultimus begins also to exhibit some resemblance to the inferior carnassières; but as it has on the interior side two tubercles as elevated as its edge, it performs the part of the tuberculous tooth. The last one is very small.

These are animals with a creeping walk and nocturnal mode of life, like all the preceding. The tail is short, the toes deeply involved in the skin, and they are eminently distinguished besides by a pouch situated under the tail, whence oozes a fat and fœtid humour. The nails of their fore-feet are consider-

[page] 31

ably elongated, and thus render them skilful in delving in the earth.

The Badger of Europe, (Ursus Meles, Lin.) Buff. VII. VII.

Grayish above, black underneath, a black band on each side of the head.

The GLUTTONS (GULO, Storr.)

Had also been placed in the genus of bears by Linnæus; but they approach more to the martins by their teeth, as well as by their entire constitution and character, resembling the bears only in their plantigrade motion. They have three false molars above and four below in front of the carnivorous tooth; and a small tuberculous one behind it, the upper of which is rather large than long. The upper carnivorous tooth has but a small tubercle. These animals have tails of moderate length, with a fold underneath instead of a pouch, and in other respects as to their gait, &c., they are sufficiently similar to the badgers.

The most celebrated species is the glutton of the north, rossomak of the Russians (Ursus gulo, Lin.) Buff. Sup. III. XLVIII. As large as our badger, usually with a beautiful fur of a deep marron, with a disk somewhat browner on the back, but sometimes of paler tints. It inhabits the coldest countries of the north, is esteemed to be remarkably cruel, hunts by night, does not sleep during the winter, and contrives to master the largest animals

[page] 32

by leaping downwards on them from a tree. Its voracity has been ridiculously exaggerated by some writers.

The Wolverene of North America (Ursus Luscus, Lin. Edw. CIII.

Does not appear to differ from the last by any permanent characters. Its tints are generally somewhat paler.

Warm climates produce some species which cannot well be ranged, except among the gluttons, not differing from them but by one false molar less in each jaw, and by a long tail. Such are those which the Spanish Americans name ferrets (hurons), and which, having in fact the teeth of our pole-cats and ferrets, have also the same mode of life. But they are distinguished from them by the plantigrade motion.

The Grison (Viverra Vittata, Lin.) Buff. Sup. VIII. XXIII. et XXV.

Black, the top of the head and neck gray; a white band extending from the forehead to the shoulders.

The Taira, (Mustela Barbara, Lin.) Buff. Sup. VII. LX.

Brown, top of the head gray, a large white spot under the neck. These two animals are found in all the warm regions of America, and diffuse a musky odour. Their feet are triflingly flat-

[page] 33

tened, and it would seem that they have some-times been taken for otters.

It is probable that the ratel (viverra mellivora, and viv. Capensis), an animal, about the size of a badger, should be placed at the end of the gluttons and Grisons. It is gray above, black underneath, having a white line between those two colours. It inhabits the Cape of Good Hope, and digs the earth with its long front talons to discover the honey there deposited by the wild bees. It is only known by an incomplete description of Sparrman.

The DIGITIGRADES

Form the second tribe of Carnivora, that which walks on the end of the toes.

There is a first subdivision of them which have but one tuberculous tooth behind the upper carnivorous one. These animals have been named vermiform, in consequence of the length of their bodies and shortness of their legs, which allows them to pass through the smallest apertures. Like all the preceding tribes they want a cæcum, but do not fall into a state of lethargy during the winter. Though small and feeble, they are exceedingly cruel and live peculiarly upon blood. Linnaeus makes but one genus of them, that of

The MARTENS, (MUSTELA, Lin.)

Which we shall divide into four sub-genera.

VOL. II. D

[page] 34

The POLECATS (PUTORIUS, Cuv.)

Are the most sanguinary of all. Their carnivorous tooth below has no interior tubercle; the tuberculous tooth above is more broad than long. They have only two false molars above and three below. As to their exterior, they may be easily recognised by their muzzle being rather shorter and more thick than that of the martens. They all diffuse an infectious odour.

The common Polecat (Mustelaputorius, L.) Buff. VII. XXIII.

Brown, the flanks yellow, with white spots upon the head. The terror of hen-roosts and warrens.

The Ferret. (Mustela furo, L.) Buff. VII. XXV. XXVI.

Yellowish, with red eyes, is perhaps only a variety of the polecat. In France we find it only in a domesticated state, and it is employed to pursue rabbits into their burrows. It comes to us from Spain and Barbary.

The Polecat of Poland, or Perouasca. (Mustela Sarmatica.) Pall. Spic. Zool. XIV. IV. 1, Schreb. CXXXII.

Brown, spotted all over with yellow and white. Its skin is much employed in the fur trade, on. account of its beautiful variegation. It inhabits all the southern part of Russia, Asia Minor, and the coasts of the Caspian Sea.

To the polecats also must be referred two small species of our climates.

[page] 35

The Weasel. (Mustela Vulgaris, L.) Buff. VII. XXIX. 1.

Altogether of an uniform red; and

The Ermine, (Mustela Ermine a, L.) Buffon, VII. XXIX. 2. XXXI. 1.

Which is red in summer, white in winter, with the tip of the tail always black. Its winter coat forms one of those furs most universally known.

It is probable that we must still refer to this race

The Polecat of Siberia. (Mustela Sibirica, Pall.) Spic. Zool. XIV. IV. 2.

Altogether of a clear uniform fawn-colour; and

The Mink, Norek, Noerz, or Polecat of the Northern Rivers. (Mustela Lutreola, Pall.) Spic. Zool. XIV. III. 1. Les Mem. de Stockh. 1739, pl. XI.

Which frequents the edges of the water in the north and east of Europe, from the Icy as far as the Black Sea, and subsists on frogs and crab-fish. The feet are triflingly flattened between the bases of the toes, but the teeth and the round tail approach it more to the polecats than to the otters. It is brown with a whitish jaw. Its odour is that of musk, and its fur is extremely fine.

The Polecat of the Cape. (Zorille of Buff. Viverra Zorilla, Gm.) Buff. XIII. XLI.

Radiated irregularly with white and black. It had been so long confounded with the mouffettes

D 2

[page] 36

that the name Zorillo (fox's cub), which the Spaniards applied to those fetid animals of America was given to it. It has, however, nothing in common with them except the nails adapted for delving. This circumstance indicates a subterraneous mode of life, which might induce us to distinguish this species from the other polecats.

The MARTENS, properly so called, (MUSTELA, Cuv.)

Differ from the polecats by an additional false molar above and below, and by a small interior tubercle in their carnivorous tooth below. Two characters which somewhat diminish the cruelty of their nature.

Europe has two species very nearly approaching to each other,

The common Marten (Mustela Martes, L.) Buff. VII. XXIII.

Brown, with a yellow spot under the neck; inhabits the woods.

The Fouine. (Mustela Foina, L.) Buff. VII. XVIII.

Brown, with all the upper part of the throat and neck whitish. Frequents houses. Both these species occasion much mischief.

One species is known in Siberia.

The Sable (Mustela Zibellina) Pall. Spic. Zool. XIV. III. 2. Schreb. CXXXVI.

So much celebrated for its rich fur. It is brown, with some spots of white on the head,

[page] 37

and is distinguished from the foregoing by having hair even under the toes. It likewise inhabits the most frozen mountains. The hunting of this animal in the midst of winter, through eternal snow, is one of the most painful of human labours. The pursuit of sables first gave occasion to the discovery of the eastern regions of Siberia.

Northern America produces also many of the marten tribe, which travellers and naturalists have pointed out under the ill-defined appellations of Pekan, Vison, Mink, Foutereau, &c.

The species to which we apply the name of Vison (Mustela Vison), is altogether brown, with the little point of the chin white. The fur is remarkably brilliant. It is found in Canada and the United States.

That which we shall name, Pekan, and which comes from the same countries, has the head, the neck, the shoulders, and the top of the back, mixed of gray and brown. The nose, the crupper, the tail, and the limbs, are blackish.

Both have hair even under the toes.

The MOUFFETTES (MEPHITIS) Cuv.

Have, like the polecats, two false molars above and three below, but their upper tuberculous tooth is very large and as long as broad, and their inferior carnivorous tooth has two tubercles on its internal side, which approximates them to the badgers, as the polecats approach the grisons and gluttons. The

[page] 38

mouffettes have, besides, like the badgers, the front nails long and proper for digging. The resemblance holds good even in the distribution of colours. In this family, so remarkable for its unpleasant odour, the mouffettes are distinguished for a stinking preminence above all the other species.

The mouffettes are usually radiated with white upon a black ground. But they appear to vary in the same species by the number of streaks, and they have not been interdistinguished with any sufficient accuracy. All those which come from America have a long and tufted tail, but M. Lechenaud has lately reported the existence of one species in the island of Java altogether destitute of this appendage.

The OTTERS (LUTRA, Storr.)

Have three false molars above and below, a strong talon on the upper carnivorous tooth, a tubercle on the internal side of the lower, and a large tuberculous tooth, almost as long as broad above. The head is compressed and the tongue partly rough. They are moreover distinguished from all the preceding sub-genera by their palmate feet, and their tail horizontally flattened; two characters which constitute them aquatic animals. They are supported on fish.

The common Otter. (Mustela lutra, L.) Buff. VII. XI.

Brown above, whitish beneath. Habitat, the rivers of Europe.

The Otter of America, (Mustela lutra Brasiliensis, Gm.)

Altogether brown or fawn-coloured, with a white or yellow neck, and somewhat larger than

[page] 39

our common otter. Of the rivers of the two Americas.

The Sea Otter, (Mustela lutris, L.) Schreb. CXXVIII.

Twice as large as ours, with a body considerably elongated, tail three times less than the body, hind feet extremely short. Its blackish covering as smooth and brilliant as velvet, is the most valuable of all furs. It frequently is whitish on the head. The English and Russians pursue this animal in all the northern parts of the Pacific Ocean, for the purpose of selling its skin to the Japanese and Chinese.

The second subdivision of the digitigrades has two flat tuberculous teeth behind the upper carnivorous tooth, which itself has a heel or protuberance tolerably broad. They are carnassiers, but without showing much courage in proportion to their strength. They frequently live on carrion. They have all a small csecum.

The DOGS (CANIS, L.)

Have three false molars above, four below, and two tuberculous teeth behind each carnivorous one. The first of these tuberculous teeth in the upper row is very large. The upper carnivorous tooth has but a single small tubercle within, but the lower one has its posterior point altogether tuberculous. Their tongue is soft. The fore-feet have five toes and the hinder four.

[page] 40

The domestic Dog. (Canis Familiaris, L.)

Is distinguished by a curved tail, and varies besides ad itifinitum as to size, form, colour, and the quality of the hair. The dog is the most complete, the most remarkable, and the most useful conquest ever made by man. Every species has become our property; each individual is altogether devoted to his master, assumes his manners, knows and defends his property, and remains attached to him until death; and all this proceeds neither from want nor constraint, but solely from true gratitude and real friendship. The swiftness, the strength, and the scent of the dog, have created for man a powerful ally against other animals, and were perhaps necessary to the establishment of society. He is the only animal which has followed man through every region of the earth.

Some naturalists think that the dog is a wolf, others a domesticated jackal. The dogs, however, which have become wild again in desert islands do not resemble either of these species. The wild dogs and those belonging to barbarous people, such as the inhabitants of New Holland, have straight ears, which would lead us to the belief that the European races, which approximate the most to the original type, are our shepherd's dog and our wolf-dog. But the comparison of crania points to a closer approximation in the mastiff and Danish dog: after which

[page] 41

come the hound, the pointer, and the terrier, which do not differ between themselves except in size and the proportions of the limbs. The greyhound is more lank, and its frontal sinuses are small and its scent more feeble. The shepherd's dog and the wolf-dog resume the straight ears of the wild dogs, but with a greater development of the brain, which proceeds increasing, with a proportionate degree of intelligence in the barbet and the spaniel. The bull-dog, on the other hand, is remarkable for the shortness and vigour of its jaws. The small chamber-dogs, the pugs, spaniels, shock-dogs, &c., are the most degenerate productions, and constitute the most striking marks of that power which man exercises over nature.

The dog is born with the eyes closed. He opens them the tenth or twelfth day. His teeth begin to change in the fourth month, and his growth terminates at two years of age. The female goes with young sixty-three days, and brings forth from six to a dozen young ones. The dog is old at five years, and seldom lives more than.twenty. The vigilance, the bark, the singular mode of copulation of this animal, and his striking susceptibility of a varied education, are universally known.

The Wolf. (Canis Lupus, L.) Buff. VII. I.

A large species with a straight tail; fur of a grayish fawn colour, with a black streak on the fore-limbs of the adults. It is the most mis-

[page] 42

chievous of all the carnassiers known in our countries. It is found from Egypt as far as Lapland, and appears to have passed into America. In northern regions its fur becomes white in the winter season. It attacks all our animals, but yet by no means displays courage in proportion to its strength. It often preys on carrion. Its habits and physical development have many close relations with those of the dog.

The Black Wolf. (Canis Lycaon, L.) Buff. IX. XLI.

Inhabits also in Europe, and is found even in France, but very rarely*. Its fur is of a deep and uniform black. It is said to be more ferocious than the common wolf.

The Red Wolf. (Canis Mexicanus, Lin.) Agoura-Gouazou of Azzara.

Of a fine cinnamon red, with a short black mane along the entire spine. Found in the marshes of all the hot and temperate regions of America.

The Jackal, or Golden Wolf. (Canis Aureus, Lin.) Schreb. XCIV.

Somewhat less than the three preceding; grayish brown, the thighs and legs of a clear fawn-colour; some red upon the ear. It inhabits in troops a great part of Asia and Africa, from India and the environs of the Caspian Sea

* I have seen four individuals taken or killed in France. It must not be confounded with the Black Fox, with whose synonymes Gmelin has mixed it up.

[page] 43

as far as Guinea. It is a voracious animal, which hunts after the manner of a dog, and seems to resemble him more nearly than any other wild species in conformation and facility of being tamed.

The Foxes may be distinguished from the wolves and dogs by a longer and more tufted tail, by a more pointed muzzle, by pupils calculated for nocturnal ision *, and by upper incisives less sloping. They diffuse a fetid odour, dig themselves burrows, and only attack weak animals. This sub-genus is more numerous than thepreceding.

The common Fox. (Canis Vulpes, L.) Buff. VII. VI.

More or less red, the end of the tail white. Is spread over most climates from Sweden even to Egypt. Those of the north are distinguished only by a more brilliant fur. We observe no constant difference between those of the Old Continent and those of North America. The Coal Fox (Canis Alopex) Schreb. XCI., which has the end of the tail black, and is found in the same countries as the common, and The Cross Fox (id. XCI. A), which is distinguished only by a streak of black along the spine and over the shoulders, are probably but varieties of the common fox. But the following species are very distinct.

* The Baron seems to conclude that elongated pupils are adapted for nocturnal habits, a conclusion which we have elsewhere ventured to think unfounded.—ED.

[page] 44

The Corsac, or Small Yellow Fox, (Canis Corsac, Gm.) Buff.. Supp. III. XVI., under the name Adive.

Of a pale yellowish gray, some blackish waves on the base of the tail. The end of the tail black, and the jaw white. Common in the vast heaths of Central Asia, from the Volga to the East Indies; possesses the habits of the common fox, and never drinks.

The Tri-coloured Fox of America, (Canis Cinereo-argentcus.) Schreb. XCII. A.

Ash-coloured above, white beneath, a band of cinnamon red along the flanks. Habitat, all the hot and temperate climates of the two Americas.

The Silvery or Black Fox *.

Black, but the ends of the hairs are white, except on the ears, shoulders, and tail, where they are purely black. The tip of the tail is altogether white. From North America. Its fur is one of the finest and most highly prized.

The Blue Fox, or Isatis, (Canis Lagopus), Schreb. XCIII.

Deep ashen colour; the under part of the toes furnished with hairs. It is often white in winter. From the north of Siberia. Likewise very much esteemed for the fur.

* Gmelin has confounded this with the black wolf, under the name of Canis Lycaon.

[page] 45

The Cape Fox, (Canis Mesomelas,) * Schreb. XCV.

Yellow on the flanks, the middle of the back black, mixed with white, and finishing in a point at the end †.

The CIVETS (VIVERRA),

Have three false molars above and four below, the anterior of which occasionally drop out; two tuberculous teeth, tolerably large above, one only below, and two projecting tubercles on the internal side of the lower carnivorous tooth in front, the rest of this tooth being more or less tuberculous. The tongue is covered with sharp and rough papillae. Their claws are partly straightened as they walk, and near the anus is a pouch more or less deep, where an unctuous and odoriferous matter exudes from peculiar glands.

They are divided into four sub-genera:

The CIVETS, properly so called, (VIVERRA, Cuv.)

In which the deep pouch situated between the anus and the organ of generation, and divided into two

* Gmelin has confounded it with the Adive of Buffon, a factitious species not differing from the Sachal.

† The Fennec of Bruce, which Gmel. names Canis Cerdo, and Uig. Megalotis, is too little known to be classified. It is a small animal of Africa, whose ears almost equal the whole body in size and which climbs trees. Neither the teeth nor toes have been described.

[page] 46

bags, is filled with an abundant unction, of a strongly-musked odour.

The Civet (Viverra Civetta, Lin.) Buff. IX. xxxiv.

Gray with brown or blackish spots, the tail brown, less than the body. Along the entire back and tail is a mane capable of elevation. This animal comes from the hottest parts of Africa.

The Zibeth, (Viverra Zibetha, Lin.) Buff. IX. XXXI.

Gray, shaded with brown, long tail tinged with black.

The Genets, (Genetta, Cuv.)

In which the pouch is reduced to a slight hollow formed by the projection of the glands, and almost without any sensible excretion although there is a most manifest odour.

The Common Genet, (Viverra Genetta, Lin.)Buff. IX. XXXVI.

Gray, with small round black spots, and a tail tinged with black. As large as a marten, and still more slender. Seems to inhabit from Southern France as far as the Cape of Good Hope*.

* The Civet of Malacca of Sonnerat, the Genet of the Cape, Buff., the Cape-Cat, Forster, the Bisaam-Cat of Vosmaer, of which Gmelin has made so many species, appear only common Genets. To this subdivision must be referred the radiated Pole-cat of India, Buff. Sup. VII, LVII. (Viv. fasciata, Gm.)

[page] 47

The Fossane of Madagascar, (Viv. Fossa,) Buff. XIII. XX.

Has those parts of a fawn colour which are black in the genet, and scarcely any rings to its tail.

The MANGOUSTES, Cuv. (HERPESTES, Iliger.)

In which the pouch is voluminous, simple, and has the anus bored in its depth.

The Mangouste of Egypt, so celebrated under the name Ichneumon, (Viverra Ichneumon, L.)Buff. Sup. III. XXVI.

Gray, with a long tail terminated by a black tuft; larger than our cats, as slender as our martens. It searches peculiarly for the eggs of crocodiles, but also subsists on all kinds of small animals. Domesticated in houses, it hunts mice, reptiles, &c. The Europeans at Cairo call it Pharaoh's rat, the people of the country Nems. What the ancients related of its jumping down the throat of the crocodile to put it to death, is fabulous.

The Mangouste of the Indies, (Viverra Mungos, L.) Buff., XIII. XIX.; and that of the Cape, (Viv. Cafra, Gm.) Schreb. CXVI. B.

Both have the tail pointed, and the fur gray or brown, but uniform in the latter, streaked crosswise with black in the former, which also has the jaws streaked with fawn-colour.

[page] 48

The mangouste of the Indies is celebrated for his combats with the most dangerous serpents, and by the fame of having made known the virtue of the ophiorhiza mongos against their bite.

The SURIKATES, (RYZÆNA, Iliger)

Which have a strong resemblance to the mangoustes, even to the very tints and transverse streaks of the fur, but which are yet distinguished from them and from all the Carnivora hitherto treated of, by having only four toes on all the feet. Their pouches extend into the anus like those of the preceding.

But one species is known, a native of Africa, (Viverra tetradactyla, Gm.) Buff., XIII. VIII., some-what smaller than the mangouste of India *.

The last subdivision of the digitigrades has no small teeth whatever behind the large molar below. It contains the most cruel animals, and the most decidedly carnivorous of the whole class. There are two genera:

The HYÆNAS, (HYÆNA, Storr.)

Which have three false molars above and four below, all conical, blunt, and singularly thick and clumsy. The upper carnivorous tooth has a small tubercle within, and in front. But the lower one has none, and presents only two strong trenchant points. This powerful apparatus enables the hyænas to break the

* The Zenik of Sonnerat, deuxiéme voy. pl. 92, does not seem to differ from the Surikate but by being ill-drawn.

[page] 49

bones of the' strongest animals which become their prey. Their tongue is rough. All their feet have four toes like the Surikates, and under the anus is a deep and glandulous pouch. They are nocturnal animals, voracious, living particularly on carcasses, and seeking them even in the tombs. There are many superstitious traditions relative to these animals. Two species are known:

The Striped Hyæ.na (Canis Hymia, Lin.) Buff. Sup. III. XLVI.

Gray, irregularly radiated across with brown or black. A mane along the nape of the neck and the back, which it elevates in the moments of anger. It inhabits from the Indies as far as Abyssinia and Senegal.

The Spotted Hyæna, (Canis Crocuta, Lin.) Schreb. XCVI. B.

Gray, spotted with black, from the South of Africa. It is the tiger-wolf of the Cape.

The CATS, (FELIS, Lin.)

Are of all the Carnassiers the most powerfully armed. Their short and round muzzle, their short jaws, and above all their retractile claws, which, drawn upwards and concealed within the toes by the effect of elastic ligaments when in a state of rest, thus never losing their point or edge, render them, especially the larger species, very formidable animals. They have two false molars above and two below. Their

VOL. II. E

[page] 50

upper carnivorous tooth has three lobes, and a blunt heel within, the lower two have pointed and trenchant lobes without any heel. Finally, they have but a very small upper tuberculous tooth, without any thing to correspond below. The species of this genus are very numerous, and very various in size and colour, although all similar in form. They cannot be subdivided but according to the somewhat unimportant characters of size and the magnitude of the fur.

At the head of this genus stands,

The Lion, (Felis Leo. Lin.) Buff. VIII. I. II.

Distinguished by its uniform fawn-colour, the tuft of hair at the tip of its tail, and the mane which clothes the head, neck, and shoulders of the male. This is the strongest and most courageous of all animals of prey. Formerly the species was spread through the three divisions of the old world, but at present it seems almost confined to Africa, and some neighbouring parts of Asia. The head of the lion is more squared than that of the following species.

The tigers are large species with smooth skin, very frequently marked with bright spots.

The Royal Tiger, (Felis Tigris,) Buff. VIII. IX.

As large as the lion, but with a more elongated body and rounder head. Of a bright fawn-colour above and pure white underneath, radiated ir-

[page] 51

regularly and cross-wise with black. The most cruel of quadrupeds and the most terrible scourge of the East Indies. So great are its force and swiftness that, during the march of armies, it has been known to snatch a horseman from his horse, and carry him off into the recesses of the woods without the possibility of rescue.

The Jaguar or American Tiger. The great Panther of Furriers. (Felis Onça, Lin.) d'Azzara, Voy.pl. IX.

Almost as large as the oriental tiger, and almost as dangerous. A bright fawn-colour above, marked along the flanks with four ranges of black spots in the form of eyes, that is, with rings more or less complete, with a black point in the middle. White underneath, radiated cross-wise with black.

There are some individuals black, on which the spots, of a still deeper hue, are visible only at certain points of exposition.

The Panther, (Felis Pardus, Lin.) The Pardalis of the Ancients. Cuv. Menag. du Mus. 8vo. I. p. 212;

Fawn-coloured above, white underneath, with six or seven ranges of black spots in the form of roses, that is to say, formed by an assemblage of five or six simple spots on each flank.

E 2

[page] 52

The Leopard,, (Felis Leopardus, Lin.)

Like the panther, but with ten ranges of smaller spots.

These two species are of Africa, and smaller than the Jaguar. Travellers and Furriers designate them indistinctly under the names of leopard, panther, African tiger, &c.*

The Guepard, or Hunting Tiger of India, (Felis jubata, L.) Schreb. CV.

Of a clear fawn-colour, with small black simple spots equally distributed. This animal is smaller than the panther, has greater height in the limbs, and longer hair on the nape of the neck. In India they are trained like dogs for the chase, for which purpose the panther is also employed in some countries.

The Couguar, Puma, or pretended American Lion. (Felis discolor, L.) Buff. VIII. xix.

Red, with small spots of the same colour a little deeper, and which are not easily distinguished. Of the whole of America.

* Buffon has mistaken the jaguar for the panther of the Old World, and has not well distinguished the panther and leopard. Therefore we forbear to cite him.

[page] 53

The Melas or Black Panther, (Felis Melas, Peron.)

Black, with simple spots of a deeper hue. Of the East Indies.

The Ocelot, (Felis pardalis, Lin.) Buff. XIII, pi. xxxv. xxxvi.

With lower limbs than the preceding. Gray, with large fawn-coloured spots bordered with black, and forming oblique bands on the flanks. Habitat, the whole of America.

Among the inferior species, the lynxes should be distinguished, which are remarkable for the brushes of hair with which their ears are adorned.

The Common Lynx (Felis Lynx. L.) Buff. VIII. XXI.

Reddish fawn-colour, most frequently spotted with blackish; tail very short. Of all the old continent. It was formerly found in France, and it is not long since the last of the race have disappeared from Germany.

The Lynx of Canada, (Felis Canadensis, Geoff.) Buff. Supp. III. XLIV.

Whitish gray with some spots of a pale brown.

It appears to form a distinct species.

The American Lynx, (Felis rufa. Guld.) Screb. CIX. B.

Reddish fawn-colour, patched with brownish. Brown waves on the thighs. Somewhat smaller than the lynx. Of the United States.

[page] 54

The Lynx of the Marshes, Booted Lynx, &c. (Felis Chaus. Giild.) Schreb. CX. Brace''s Travels, pl. XXV.

A yellowish gray brown; hinder part of the legs blackish. Inhabits the marshes of the Caucasus, of Persia, Egypt, and Abyssinia. Hunts water-fowl, &c.

The Caracal (Felis Caracal, L.) Buff. IX. xxiv. and Supp.III. XLV.

Of a vinous red nearly uniform. Inhabits Persia, Turkey, &c. Is the true lynx of the ancients.

The inferior species, the ears of which have no pencils of hairs, resemble more or less our domestic cat. Such are,

The Serval, (Felis Serval, L.) Buff. XIII. XXXV.

As large as a lynx. Yellowish, with irregular black spots.

The Jaguarondi, (Felis jaguarondi,) Azzara, Voy. pl. X.

Elongated, and altogether of a brownish black. Both these last live in the forests of South America.

The Common Cat, (Felis catus, L.) Buff. VI. i.&c.

Originally a native of our European forests. In its wild state it is grayish brown, with trans-

[page] 55

verse waves of a deeper colour. The under part is pale; the inside of the thighs and four paws yellowish. Three bands on the tail, and the lower third blackish. In a domestic state, it varies, as every one knows, in colour, in the length and fineness of the fur, but infinitely less so than the dog. It is also much less submissive and attached.

The AMPHIBIOUS ANIMALS

Will form the third and last of the small tribes into which we divide the Carnivora. Their feet are so short and so much enveloped in the skin, that they can use them on the earth for no purpose but creeping. But as the intervals of the toes are filled by membranes, they form excellent oars. These animals accordingly pass the most considerable portion of their life in the sea, and do not come to land except to bask in the sun, and suckle their little ones. Their elongated bodies, the great mobility of their spine, and the strength of its flexor-muscles, their narrow pelvis, their hair smooth and tightened, as it were, against the skin, are properties, which combined together, are well calculated to make them excellent swimmers; and all the details of their anatomy confirm this opinion, and correspond with the result of our first superficial observations.

But two genera have hitherto been distinguished, the Scals and the Morses.

[page] 56

The SEALS (PHOCA, L.)

Have four or six incisors above, four below, pointed canines and cheek teeth to the number of twenty, twenty-two, or twenty-four, all trenchant or conical, without any tuberculous part. Five toes on all the feet, those of the fore-feet decreasing gradually from the thumb or great toe to the little one; while, on the contrary, in the hind feet, the great and little toe are the longest, and the intermediate ones decrease in size. The fore-limbs are enveloped in the skin of the body as far as the wrist, the hinder nearly as far as the heel. Between them is a short tail. The head of the seals resembles that of a dog, and they likewise possess the kind and intelligent expression of countenance peculiar to that animal. They are easily tamed, and soon become attached to those who feed them. Their tongue is smooth, and sloping towards the end. The stomach is simple, the caecum short, the canal long, and tolerably equal. These animals live on fish; they eat always in the water, and can close their nostrils when they dive by means of a kind of valve. As they dive for a long time, it has been supposed that the botale foramen remained open in them as in the foetus. But this is not the case; there is, however, a large venous sinus in the liver which assists them in diving, and renders respiration less necessary to the circulation of the blood. Their blood is very abundant and extremely black.

[page] 57

The SEALS, properly so called, or without external ears,

Have pointed incisors, the external parts of which above are longer than the other teeth. They have trenchant molars with many points. All their toes possess a power of motion, and are terminated by pointed nails placed on the edge of the membrane which unites them.

The common Seal. (Phoca Vitidina, L.) Buff. XIII. XLV. and Supp. VI. XLVI.

From three to five feet in length: of a yellowish gray: more or less waved or spotted with brown according to the age. It becomes white in old age. It is common on our coasts and found to a considerable distance in the north. We are even assured that it is this species which inhabits the Caspian Sea, and the large lakes of fresh water in Russia and Siberia, but this assertion does not appear to be founded on a very exact comparison.

The Crescent Seal, or Swartside. (Phoca Groënlandica.) Egede Groenl. fig. A. pag. 62.

Yellowish gray, spotted with brown when young, marked afterwards with an oblique brown semilunar mark five feet long. Of the Icy Sea,

[page] 58

The White-bellied Seal. (Phoca monachus, Gm.) Buff. Supp. VI. pl. XIII.

From ten to twelve feet long. Blackish brown, with white belly. Of the Mediterranean, and more especially of the Adriatic Sea.

The Bottle-nosed Seal. (Phoca Leonina, L.) Sea-Lion of Anson; Sea-Wolf of Pernetty; Sea-Elephant of the English and of Peron. Peron, Voy. L. XXXII.

From twenty to twenty-five feet long; brown; the muzzle of the male is terminated by a wrinkled sort of horn or snout, which swells up when the animal is angry. It is common in the southern latitudes of the Pacific Ocean, in Terra-del-Fuego, New Zealand, and Chili. It is hunted on account of the abundant oil which it furnishes.

The Hooded Seal. (Phoca Crestata, Gm., Phoca Leonina, Fabricius.) Egede, Groenl.pl. VI.

Eight feet long. A sort of moveable cowl or crest attaches to the summit of the head, with which the animal covers its eyes and muzzle when threatened. Inhabits the Icy Sea.

The SEALS, with external ears. (OTARIES, Peron.)

Might deserve to form a genus apart, since, beside the external projecting ears, they have the four middle incisives in the upper row with double edges,

[page] 59