[frontispiece]

[page iii]

FAUNA

BOREALI-AMERICANA;

OF THE

ZOOLOGY

OF THE

NORTHERN PARTS

OF

BRITISH AMERICA:

CONTAINING DESCRIPTIONS OF THE OBJECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY COLLECTED ON THE LATE NORTHERN LAND

EXPEDITIONS, UNDER COMMAND OF CAPTAIN SIR JOHN FRANKLIN, R.N.

BY

JOHN RICHARDSON, M.D., F.R.S., F.L.S.

MEMBER OF THE WERNERIAN NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY OF EDINRURGH, AND

FOREIGN MEMBER OF THE GEOGRAFHICAL SOCIETY OF PARIS,

SURGEON AND NATURALIST TO THE EXPEDITIONS.

ASSISTED BY

WILLIAM SWAINSON, ESQ., F.R.S., F.L.S., &c.

AND

THE REVEREND WILLIAM KIRBY, M.A., F.R.S., F.L.S., &c.

ILLUSTRATED BY NUMEROUS PLATES.

PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY OF

STATE FOR COLONIAL AFFAIRS.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

MDCCCXXIX.

[page iv]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLAM CLOWES,

STAMFORD-STREET.

[page v]

FAUNA

BOREALI-AMERICANA.

PART FIRST,

CONTAINING

THE QUADRUPEDS.

BY

JOHN RICHARDSON,

M.D., F.R.S., F.L.S., &c.

[page vi]

[page vii]

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LOED VISCOUNT GODERICH,

THE FOLLOWING WORK,

UNDERTAKEN UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF HIS LORDSHIP,

IS,

BY PERMISSION,

INSCRIBED WITH THE UTMOST RESPECT,

BY

HIS MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT,

JOHN RICHARDSON.

[page viii]

[page ix]

INTRODUCTION.

THE objects of Natural History collected by the last Overland Expedition to the Polar Sea, under the command of Captain Sir John Franklin, to which I was attached as Surgeon and Naturalist, being too numerous for a detailed account of them to be comprised within the ordinary limits of an Appendix to the narrative of the proceedings of the journey, I was desirous of making them known to the world in a separate work. As it was necessary, however, in order to render such a publication useful, that many of the subjects, particularly in the Ornithological and Botanical parts, should be illustrated by figures, the expense would have been an insurmountable difficulty, had not His Majesty's Government, actuated by a most laudable desire of encouraging science, lent a liberal aid to the undertaking. On an application, which had the approval of the Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs, the Treasury granted one thousand pounds, to be applied solely towards defraying the expense of the engravings. A moiety of that sum has been allotted to the illustration of the Quadrupeds and Birds, and the remainder to the Fishes, Insects, and Plants; and care has been taken, by employing only the first artists, to render the plates worthy of the high patronage the work has received; while their number will demonstrate the rigid economy with which the funds for their execution have been distributed*.

* There are twenty-eight plates in this part; and fifty admirable coloured ones, of birds, have also been executed. The botanical plates will likewise be numerous, and many of them are already finished.

b

[page] x

Having neither leisure nor ability to do justice to the different departments of such a work, without assistance, I have gladly availed myself of the aid of several kind friends and able naturalists,—the First Part, relating to the QUADRUPEDS, being the only one for which I am solely accountable. William Swainson, Esq., the able illustrator of the Ornithology of the Brasils, undertook to arrange and make drawings of the BIRDS, elucidate the Synonyms, furnish Remarks on the natural groups, and, in fact, to charge himself with the principal part of the Ornithology. The Reverend Mr. Kirby agreed to arrange and describe the INSECTS; and Dr. Hooker, Professor of Botany at Glasgow, relieved me entirely from the charge of describing the PLANTS. The number of specimens of these requiring that Dr. Hooker's part should extend to about two volumes of letter-press, it has been judged better to publish the Zoology and Botany in separate works,—the latter edited solely by Dr. Hooker, and as similar to the former in paper and type as possible*. The following introductory remarks are, therefore, drawn up principally with a view to the Zoölogical specimens.

First, with regard to the geographical limits of the country, whose ferine inhabitants are to be described.

The Expedition landed at New York, proceeded up the Hudson to Albany; from thence westward by the ridge-road to Niagara; then, after a short visit to the stupendous falls on that river, it crossed Lake Ontario to York, the capital of Upper Canada; and, passing by Lake Simcoe and the river Nattawasaga, it arrived at Penetanguishene, on the north-east arm of Lake Huron, in the beginning of April. Up to this place, owing to the early period of the year, and the mode of travelling, which was, for the greater part of our route, in carriages at a rapid rate, our collections were small, consisting, in Zoology, only of a few insects and serpents, and in Botany, principally of lichens

* Dr. Hooker is far advanced with his work, which will come out in parts; and Mr. Drummond has already, under his inspection, published two volumes of dried American mosses, containing two hundred and eighty-six species, collected by the Expedition.

[page] xi

and mosses. With these slight exceptions, the specimens brought to England were entirely collected to the north of the Great Canada Lakes, beyond the settled parts of Upper Canada, and, in fact, in a widely extended territory, wherein the scattered trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company furnish the only vestiges of civilisation. The following work may, therefore, be termed a Fauna; or, more properly, Contributions to a Faunaof the British American Fur Countries; or it may be considered, in a general view, as comprising what is known of the Zoology of that part of America, which lies to the north of the 49th parallel of latitude, and which, to the east of the Rocky Mountains, at least, is exclusively British. I have, however, included in it descriptions of a few specimens obtained a degree or two to the southward of that latitude on Lake Huron and on the River Columbia, in both of which quarters there are several fur-posts of the Hudson's Bay Company. After having travelled through the Fur Countries lying to the eastward of the Rocky Mountains, for seven summers, and passed five winters at widely distant posts, it will scarcely be thought that I arrogate too much in saying, that almost all the quadrupeds that are objects of chase or interest to the natives, and a very great proportion of the birds, either came within the scope of my own observation, or were mentioned in the many conversations I had with the white residents and native hunters, on the natural productions of the country. But, although my opportunities of ascertaining the number of species actually inhabiting the northern parts of America were so great, I must confess, that a journey like ours, in which natural history was only a subordinate object, and at many periods of which the shortest delay beyond that absolutely necessary for refreshment and repose, was inadmissible, did not afford much opportunity for studying the manners and habits of the animals with the attention I could have wished to have devoted to that subject. The present work, therefore, though fuller than any preceding one, is to be considered only in the light of a sketch, in which many omissions remain to be supplied and inaccuracies to be corrected by future observers. To render the list as complete as possible, I have included

b 2

[page] xii

those animals mentioned by preceding writers, which did not come under the notice of the Expedition; always carefully acknowledging the source of my quotations.

Sir John Franklin's narratives of his two journeys contain full information respecting the districts through which the Expedition travelled; but, to save reference, and to enable the reader of this work the more readily to discover the particular habitats, and to trace the geographical distribution of the species described in it, I have thought it proper to give a summary account of our route, followed by some compendious topographical notices.

The First of the two NORTHERN LAND EXPEDITIONS disembarked in the month of August, 1819, at York Factory, in Hudson's Bay, which is 90° of longitude east of the meridian of Greenwich. From thence, travelling between the 57th and 53d parallels of latitude, by Hayes' River, Lake Winipeg, and the Saskatchewan, it proceeded to Cumberland-house, situated beyond the 102d meridian, where it arrived towards the end of October. Early in January, 1820, the Commanding Officer, accompanied by Mr. (now Captain) Back, set out, to travel on snow-shoes up the Saskatchewan, nearly west-south-west to Carlton-house, in the 106th degree of longitude; and from thence, on a northerly and somewhat westerly course, by Green Lake, the Beaver River, Isle à la Crosse, and Buffalo lakes, across the Methy portage, and down the Elk River, to Fort Chepewyan, on the Athapescow or Athabascow Lake, or Lake of the Hills, as it is named by Sir Alexander Mackenzie. The other two officers of the Expedition (Lieutenant Hood and myself) stayed, during the remainder of the winter, at Cumberland-house; and after I had paid a visit in May to the plains of Carlton, and collected all the specimens of plants and animals I could procure at that season, set out in the month of June, to travel in canoe to Fort Chepewyan by the route of Beaver Lake, Missinippi or English River, Black-bear Island Lake, Isle à, la Crosse, Buffalo Lake and Elk River. Having rejoined our companions, the whole party left Fort Chepewyan on the 18th of July, 1820; and,

[page] xiii

descending the Slave River, crossed Great Slave Lake, and ascended the Yellow-knife River, to the banks of Winter Lake, situated in latitude 64½°, and in the 113th degree of longitude, which it reached on the 19th day of August. A winter of nine months' duration was spent at this place in a log building, which was named Fort Enterprise; and in the beginning of June, 1821, while the snow was still lying on the ground, and the ice covering the river, the Expedition resumed its march. After the baggage and canoes had been dragged over ice and snow for one hundred and twenty miles to the north end of Point Lake, we embarked on the Coppermine River on the 1st of July, and on the 21st of the same month reached the Arctic Sea, when, turning to the eastward, we performed a coasting voyage of six hundred and twenty-six statute miles, to Point Turnagain, which is, owing to the deep indentations of the coast, only six degrees and a half of longitude to the eastward of the mouth of the Coppermine River. The rapid approach of winter now rendered it necessary to abandon the further pursuit of the enterprise; and on the 22d of August we retraced our course as far as Hood's River, which we ascended for a short way, and then set out to travel overland to Point Lake, on our way back to Fort Enterprise. Winter, clothed with all the terrors of an arctic climate, overtook the party early in September: it suffered dreadfully from famine, no supplies were obtained at Fort Enterprise, the majority of the party perished, and the survivors were on the verge of the grave, when the Indians brought supplies of provision, and conducted them to Fort Providence, the nearest of the Hudson Bay Company's posts. The want of the means of carriage, even at the most flattering periods of this disastrous journey, prevented us from attempting to preserve any bulky objects of natural history; but all the plants gathered previous to our reaching the mouth of the Coppermine River were saved, having been given in charge to five of the party who were sent back from thence. Those collected on the sea-coast, after having been carried for many days through the snow, were at length, on our strength being completely exhausted, reluctantly abandoned. The

[page] xiv

winter of 1821-22 was passed at Fort Resolution, on the south side of Great Slave Lake; and the summer of 1822 was consumed in returning by the route we had before travelled to York Factory, where we embarked for England in the month of September. The most interesting of the quadrupeds and birds collected on this Expedition were described by Joseph Sabine, Esq., in the Appendix to Sir John Franklin's narrative, and I published a list of the plants in the same work.

The Second or Last NORTHERN LAND EXPEDITION commenced, as far as regards the objects of natural history described in this work, at Penetanguishene, on St. George's day, the 23d of April, 1825, and having performed a coasting voyage along the northern sides of Lakes Huron and Superior, arrived at Fort William, a post of the Hudson's Bay Company, situated in Thunder Bay of the last-mentioned lake. From thence it ascended the Kamenistiguia to Dog Lake, and crossing a height of land of no great elevation at the source of the Dog River, and only between twenty and thirty miles from the shores of Lake Superior, it descended by a series of rocky rivers, interrupted by numerous cascades and portages, to Rainy Lake, the Lake of the Woods, and Lake Winipeg. On entering the Saskatchewan River, which falls into the last-mentioned lake, on its east side, the Second Expedition came upon the route of the first one already described, which it kept till its arrival at Fort Resolution, on Great Slave Lake. At Cumberland-house, Mr. Drummond, the Assistant Naturalist, was detached up the Saskatchewan to examine the plains of Carlton, and the eastern declivity of the Rocky Mountains, near the sources of the Peace River. His labours will be more particularly mentioned hereafter: at present I proceed to trace the progress of the Expedition, which, on its arrival at Fort Resolution, instead of directing its course across Great Slave Lake, as on the first journey, turned to the westward, along the south shore of the lake, and entered the Mackenzie, by far the largest of all the American rivers which fall into the Polar Sea, and which originating in the same elevated part of the Rocky

[page] xv

Mountain chain with the Columbia, the Missouri, and the Saskatchewan, or Nelson Rivers, flows under the names of Elk, Slave, or Mackenzie River, on a north-north-west general course, through fifteen degrees of latitude, until it discharges itself into the sea by a mouth extending from the 133d to the 137th degree of longitude. When the Expedition reached the 65th degree of latitude in its descent of the Mackenzie, it turned to the eastward for seventy miles up a river to Great Bear Lake, where a winter residence was erected, on which the appellation of Fort Franklin was bestowed. Excursions were made down the Mackenzie and along Bear Lake while the navigation continued open, but the whole party were assembled at their winter-quarters on the 5th of September. The extent of country examined this first season may be judged of by the length of the route of the Expedition, from its leaving Penetanguishene in the month of April till its assembling at Great Bear Lake in September, which, including Mr. Drummond's journey to the Rocky Mountains, Sir John Franklin's voyage down the Mackenzie to the sea, and a voyage round Great Bear Lake by myself, exceeded six thousand miles. Towards the end of the month of June 1826, the Expedition left its winter-quarters, and proceeded down the Mackenzie to the sea; and the Commanding Officer, turning to the westward, sailed along the coast until he attained the 70½° of latitude, and nearly the 150th degree of longitude, when the lateness of the season prohibiting a further advance, he retraced his way to Great Bear Lake. In the mean time, a detachment under my charge had sailed from the mouth of the Mackenzie eastward, round Cape Bathurst, in latitude 71° 36′ north, to the mouth of the Coppermine River, whence it travelled on foot to the north-east end of Great Bear Lake, and from thence, in a canoe, to Fort Franklin. The extent of sea-coast examined by the two branches of the Expedition exceeded twelve hundred miles, and the whole distance travelled by them from the time of their departure from Fort Franklin till their return to it again, was upwards of four thousand miles. A collection of plants formed by Captain Back, who accompanied Sir John Franklin, is peculiarly

[page] xvi

interesting, as having been made principally on a coast skirting the northern termination of the Rocky Mountains. The Expedition returned to England the following summer; one division of it by way of Canada and New York, and the other by Hudson's Bay. I passed the early part of the winter at Great Slave Lake, where I obtained specimens of all the fur-bearing animals of that quarter, and afterwards travelled on the snow to Carlton-house on the Saskatchewan, where, with the assistance of Mr. Drummond, who joined me there, specimens of the greatest part of the birds frequenting that district were procured in the spring. I met Sir John Franklin at Cumberland-house in June, 1827, and accompanied him to Canada by the same route by which we came out, except that we went by the east side of Lake Winipeg, thus completing the circuit of that lake, and that instead of crossing Lake Ontario, on our way to New York, we gained the Uttawas from Lake Huron, by the route of the French River, and descended it to Montreal, whence we travelled to New York by way of Lake Champlain.

Having thus given in detail the routes of the other branches of the Expedition, it remains that I should mention the one pursued by Mr. Drummond, the Assistant Naturalist, to whose unrivalled skill in collecting, and indefatigable zeal, we are indebted for most of the insects, the greater part of the specimens of plants, and a considerable number of the quadrupeds and birds. This gentleman remained at Cumberland-house in the year 1825, after the rest of the party had gone to the north, collecting plants during the month of July, and then ascended the Saskatchewan for six hundred and sixty miles, to Edmonton-house, performing much of the journey on foot, and amassing objects of natural history by the way. Leaving Edmonton-house on the 22d of September, he crossed a swampy and thickly wooded country to Red Deer River, one of the branches of the Elk or Athapescow River, and along whose banks he travelled until he reached the Rocky Mountains, the ground being then covered with snow. Having explored the portage-road across the mountains to the Columbia River, for fifty miles, he hired an Indian hunter, with whom

[page] xvii

he returned to the head of the Elk River, on which he passed the winter making collections, under privations which would have effectually quenched the zeal of a less hardy naturalist. In the month of April, 1826, he revisited the Columbia portage-road, and remained in that neighbourhood until the 10th of August, when he made a journey to the head waters of the Peace River, during which he suffered severely from famine. Nothing daunted, however, he hastened back as soon as he obtained a supply of provisions, to the Columbia portage, with the view of crossing to that river, and botanizing for a season on its banks. He had reached the west end of the portage, when he was overtaken by letters from Sir John Franklin, acquainting him that it was necessary to be at York Factory in 1827. This rendered it necessary for him speedily to commence his return, which he did with great regret, for the view of the Columbia, whose banks are rich in natural productions, had stimulated his desire to explore them, and he remarks,—"The snow covered the ground too deeply to permit me to add much to my collections in this hasty trip over the mountains; but it was impossible to avoid noticing the great superiority of the climate on the western side of that lofty range. From the instant the descent towards the Pacific commences, there is a visible improvement in the growth of timber, and the variety of forest trees greatly increases. The few mosses that I gleaned in the excursion were so fine, that I could not but deeply regret that I was unable to pass a season or two in that interesting region." He now bade adieu to the mountains and returned to Edmonton-house, where he stayed some time, and then joined me at Carlton-house, as has been already mentioned. His collections on the mountains and plains of the Saskatchewan amounted to about "fifteen hundred species of plants, one hundred and fifty birds, fifty quadrupeds, and a considerable number of insects." He remained for six weeks at Carlton-house after I left that place, and then descended to Cumberland-house, where he met Captain Back, whom he accompanied to York Factory; but he had previously the pleasure of seeing Mr. David Douglas, who, after collecting specimens

c

[page] xviii

of plants for the Horticultural Society, for three years, on the banks of the Columbia and in North California, crossed the Rocky Mountains at the head of the Elk River, by the same portage-road that Mr. Drummond had previously travelled, and having spent a short time in visiting the Red River of Lake Winipeg, returned to England with that gentleman by way of Hudson's Bay. Thus, a zone of at least two degrees of latitude in width, and reaching entirely across the continent, from the mouth of the Columbia to that of the Nelson River of Hudson's Bay, has been explored by two of the ablest and most zealous collectors that England has ever sent forth; while a zone of similar width, extending at right angles with the other from Canada to the Polar Sea, has been more cursorily examined by the Expeditions.

Through the liberality of the Horticultural Society, and the influence of their learned Secretary, Joseph Sabine, Esq., ever readily exerted for the advancement of science, I have been permitted to examine and describe the specimens of quadrupeds collected by Mr. Douglas, and this gentleman, with a readiness to communicate the information he has acquired, that does him great credit, has kindly furnished me with some valuable notices of the habits of the animals which have been incorporated in this work. I have also had an opportunity of inspecting the specimens of quadrupeds obtained on the American coast of Behring's Straits, by Captain Beechey, on his late voyage in the Blossom; and the notes respecting them, made on the spot by Mr. Collie, Surgeon of that ship, by whom principally they were collected, have been submitted to my perusal. Previous to our setting out on the Second Expedition, Sir John Franklin addressed letters to many of the resident chief factors and traders of the Hudson's Bay Company, requesting their co-operation with our endeavours to procure specimens of Natural History, and their ready acquiescence with his desire was productive of much advantage to us. Not only were great facilities for the advancement of our pursuits afforded to us by Mr. John Haldane, Mr. James Leith, Mr. Alexander Stewart, Mr. John Prudens, Mr. Robert M'Vicar, and other gentlemen, whose posts lay on our line of route; but a collection of birds and quadrupeds,

[page] xix

of much interest, made at Fort Nelson on the River of the Mountains, a branch of the Mackenzie, was forwarded to us by Mr. Macpherson, together with some valuable specimens obtained in the same quarter by Mr. Smith, chief factor of that district. Mr. Isbister also had the kindness to prepare for us a copious collection of birds at Cumberland-house. These were not, however, the only channels through which the specimens described in the following pages were obtained. I have had ample opportunities for studying the specimens brought home by Sir Edward Parry, on his several expeditions; and much information was likewise derived from frequent visits to the museum of the Hudson's Bay Company, and from repeated examinations of the specimens imported by that Company from their posts on James's Bay, on the Columbia, and in New Caledonia, and presented by them to the Zoological Society and British Museum.

After this brief exposition of the various sources from whence the specimens were derived, I proceed to give a concise general view of the nature of the different tracts of the country, whose ferine inhabitants form the subject of the following pages. The most remarkable physical feature of the northern parts of America, is the great Mountain Ridge, which is continued under the appellation of the Rocky Mountains*, in a north-north-west direction from New Mexico, to the 70th degree of latitude, where it terminates within view of the Arctic Sea, to the westward of the mouth of the Mackenzie River. The course of this chain is tolerably straight, and its altitude, though various in different places, is everywhere far superior to that of any other mountains existing in the same parallel of the American continent. Like the Andes, of which they seem to be a prolongation, the Rocky Mountains lie much nearer to the Pacific coast than to the eastern shore of America, and they give rise to several very large rivers. Over an elevated portion of the chain, extending from the 40th to the 55th degree of latitude, are spread the upper branches and sources of the Columbia, which falls into the Pacific in the 46th parallel. If the principal arms of this river had not a very circuitous course, the nar-

* Pennant names them the "Shining Mountains."

c 2

[page] xx

rowness of the stripe of country which intervenes between the summit of the ridge and the coast would have caused it to be little better than a mountain torrent. As it is, its arms spread far and wide, and it carries a great body of water to the sea. The head waters of the Missouri interlock with those of the southern branches of the Columbia; but that river, precipitating itself down the eastern declivity of the mountains, takes a devious course to the south-east, receiving in its way several great tributaries, and joining the Mississippi, which rises at the west end of Lake Superior, in a comparatively low, but hilly country. Their united streams traverse the whole of Louisiana, and fall into the Gulf of Mexico, after a course of four thousand and five hundred miles, reckoned from the head of the Missouri. The Saskatchewan is the third great river which issues from the same elevated part of the mountains, its feeding streams spreading from the 47th to the 54th parallel of latitude, and the more southern ones being interposed betwixt the head waters of the two preceding rivers. The upper streams of the Saskatchewan, after descending from the mountains, form two principal arms, which flow through comparatively naked, sandy plains, under the names of the North and South Branches, and then unite a short way below Carlton-house. From thence the river, continuing its course through a wellwooded country, passes by Cumberland-house, where it receives a considerable tributary that originates on the immediate banks of the Missinippi, a parallel river, and afterwards, flowing through Lake Winipeg, changes its name to Nelson River, and falls into Hudson's Bay, near Cape Tatnam. The whole course of the Saskatchewan or Nelson River, from the mountains to the sea, may be estimated, windings inclusive, at one thousand six hundred miles. Lake Winipeg, besides other large streams, receives the River Winipeg, which rises on a ridge of land bordering closely on Lake Superior, and also the Red River, whose eastern branch has its sources on the same heights with the Mississippi, and whose western branch originates close to the banks of the Missouri, some distance above where that river begins to turn to the southward. By means of short portages, then, one may pass from the respective branches of the Nelson, by the

[page] xxi

Columbia, to the Pacific; by the Missouri or Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico; by the St. Lawrence to the Atlantic, and also by the Elk or Mackenzie River, whose upper streams approach the north branches of the Saskatchewan to the Arctic Sea. The fourth great river which takes its rise from the same quarter of the Rocky Mountain range is the one just mentioned,—the Mackenzie, which is the third of the North American rivers in respect of size, being inferior only to the Missouri and St. Lawrence. The two principal arms of the Mackenzie are the Elk and Peace rivers. One of the main streams of the former, the Red Deer River, issues from the vicinity of the northern sources of the Columbia and Saskatchewan, whilst other feeders interlock with the head waters of the Beaver, Missinippi, or Churchill river. Having passed through the Athapescow Lake, the Elk River is joined by the Peace River, which, originating somewhat further north in the mountains within three hundred yards of the source of the Tacootchtessè or Frazer's River, affords a canoe route to all parts of New Caledonia. It is a singular fact, that the Peace River actually rises on the west side of the Rocky Mountain ridge, and is a large stream navigable for boats at the place where it makes its way through a narrow gorge bounded by lofty mountains, which are covered with eternal snows. Nearer the source of the river, and between it and the Tacootchtessè, the mountains are less lofty and more distant, and the country has there much of the character of elevated table-land. After its union with the Peace River the Elk River assumes the name of Slave River, which, on passing through Great Slave Lake, becomes the Mackenzie. At a considerable distance below the last-mentioned lake, and where the Mackenzie makes its first near approach to the Rocky Mountains, it is joined by a large stream, which rising a little to the northward of the Peace River, flows along the eastern base of the mountains. It obtained the name of the River of the Mountains from Sir Alexander Mackenzie; but its magnitude has since gained it the appellation of the South branch of the Mackenzie from the traders. The Mackenzie receives several other large streams on its way to the sea, and among others Great Bear Lake River, whose head-waters rise on the banks of

[page] xxii

the Coppermine River and Peel's River, which issues from the Rocky Mountains, in latitude 67°. Immediately after the junction of Peel's River the Mackenzie separates into numerous branches, which flow to the sea through a great delta, composed of alluvial mud. Here from the richness of the soil, and from the river bursting its icy chains, comparatively very early in the season, and irrigating the low delta with the warmer waters brought from countries ten or twelve degrees further to the southward, trees flourish, and a more luxuriant vegetation exists than in any place in the same parallel on the American continent. In latitude 68° there are many groves of handsome white spruce firs, and in latitude 69°, on the shores of the sea, lofty and dense willow-thickets cover the flat islands; while currants and gooseberries grow on the drier hummocks, accompanied by some showy epilobiums and perennial lupins. The moose-deer, American hare, and beaver, accompany this display of vegetation to its limits. The whole course of the Mackenzie from the source of the Elk River to the sea, is about two thousand miles in length.

These are the principal rivers of the fur countries, but there are three others of shorter course, upon which some part of the collections of specimens were obtained, viz. Hayes River, which rises near Lake Winipeg, and holding an almost parallel course to Nelson's River, falls into the same part of Hudson's Bay. York Factory, which will be often mentioned in the following pages, stands on the low alluvial point that separates the mouths of these two rivers. The next river which I have to mention is the Missinippi, or, as it is occasionally named, the English River, which falls into Hudson's Bay at Churchill. Its upper stream, named the Beaver River, rises in a small ridge of hills, which separates the north branch of the Saskatchewan from a bend of the Elk River. The Coppermine is the last river which requires a particular notice. It has its origin not far from the east end of Great Slave Lake, and, taking a northerly course, flows through the Barren-grounds to the Arctic Sea. It is a stream of no great magnitude in comparison with some of the branches of the Mackenzie: there are few alluvial deposits on its banks, and there is not, conse-

[page] xxiii

quently, that richness of vegetation, which on the Mackenzie attracts certain quadrupeds to very high latitudes.

The Rocky Mountains have been crossed in four several places. first, by Sir Alexander Mackenzie, in the year 1793, at the head of the Peace River, between latitudes 55° and 56°. His route was followed, in 1806, by a party of the North-west Company, sent to make a settlement in New Caledonia, and is still occasionally used by the Hudson's Bay Company. Lewis and Clark, in the year 1805, crossed the Mountains in latitude 47°, at the head of the Missouri, in their way to the mouth of the Columbia River. For several years subsequent to that period, the North-west Company were in the habit of crossing in latitude 52½°, at the head of the North branch of the Saskatchewan, between which and one of the feeding streams of the Columbia there is a short portage; but of late years, owing to the hostility of the Indians, that route has been deserted, and the Hudson's Bay Company, who now have the whole of the Fur Trade of that country, use a portage of considerable length between the northern branch of the Columbia and the Red Deer River, one of the branches of the Elk or Mackenzie River. Some attempts have very recently been made to effect a passage in the 62nd parallel of latitude; but although several ridges of the mountains were crossed, it does not appear that any stream flowing towards the Pacific was reached.

The whole of the country lying to the eastward of the Rocky Mountains, and north of the Missouri and Great Lakes, is settled, or more or less frequently visited by the Hudson Bay Company's traders, and is well known to them, with the exception of the vicinity of the Polar Sea, and a corner bounded to the westward by the Coppermine River, Great Slave, Athapescow, Wollaston, and Deer Lakes, to the southward by the Churchill or Missinippi River, and to the northward and eastward by the sea. This north-eastern corner of the American continent is often mentioned in the following pages by the appellation of the Barren-grounds, which it has obtained from the traders on account of its being destitute of wood, except on the banks of some of the larger rivers that traverse it. The prevailing rocks in

[page] xxiv

the district are primitive, and in one or two places only do they rise so as to deserve the name of a mountain-ridge, their general form being that of an assemblage of low hills with rounded summits, and more or less precipitous sides separated by narrow valleys. The soil of the latter is sometimes an imperfect peat earth, and in that case it nourishes a few stunted willows, glandular dwarf-birches, black spruce-trees, or larches; but more generally the soil consists of the debris of the rocks, which is a dry coarse quartzose sand, unfit to support any thing but lichens. All the larger valleys have a lake of very transparent water, often of great depth in their centre, and occasionally these lakes are perfectly land-locked, though they all contain fish. More generally one lake discharges its waters into another, through a narrow gorge, by a rapid and turbulent stream, and most of the rivers which flow through the Barren-grounds are little more than a chain of narrow lakes connected in this manner. The small caribou or rein-deer, and the muskox, are the principal and characteristic inhabitants of these lands, and the description by Linnæus, of the Lapland deserts frequented by the rein-deer, applies with perfect accuracy to this corner of America. "Nullum vegetabile in tota Lapponia tanta in copia reperitur ac hæc Lichenis species, (Cenomyce rangiferina) et quidem primario in sylvis, ubi campi steriles arenosi vel glareosi, paucis Pinis consiti; ibi enim non modo videbis campos per spatium unius horas, sed sæpe duorum triumve milliarium*, nivis instar albos, solo fere hocce lichene obductos." "Hi Lichene obsiti campi, quos terram damnatam diceret peregrinus, hi sunt Lapponum agri, hæc prata eorum fertilissima, adeo ut felicem se prædicet possessor provinciæ talis sterilissimæ, atque lichene obsitæ." Being destitute of fur-bearing animals, no settlements have been formed within the Barren-grounds by the traders, and a few wretched families of Chepewyans, termed, from their mode of subsistence, "Caribou eaters," are the only human beings who reside constantly upon them. Were any one to penetrate into their lands, they might address him with propriety in the words used by the

* The Swedish mile is 5½ English miles.

[page] xxv

Lapland woman to Linnæus, when he reached her hut, exhausted by hunger and the fatigue of travelling through interminable marshes. "O thou poor man, what hard destiny can have brought thee hither, to a place never visited by any one before! This is the first time I ever beheld a stranger. Thou miserable creature! how didst thou come, and whither wilt thou go*?" Parties of Indians occasionally cross these wilds in going from the Athapescow to Fort Churchill, but they almost always experience great privations, and very often lose some of their number by famine. Hearne, in his first and second journeys, traversed them in two directions; Sir John Franklin, in his first journey, travelled within their western limits; and Sir Edward Parry, in his second voyage, obtained specimens of the animals of Melville peninsula, which forms the North-east corner of the Barrengrounds. The Chepewyans, Copper Indians, Dog-ribs, Hare-Indians, and Esquimaux visit them annually for a short period of the summer season, in quest of caribou.

The following quadrupeds are known to inhabit the Barren-grounds:

| Ursus arctos? Americanus. | More or less carnivorous or piscivorous. They prey much on the animals in the following section. |

| „ maritimus. | |

| Gulo luscus. | |

| Mustela (Putorius) erminea. | |

| „ „ vison. | |

| Lutra Canadensis. | |

| Canis lupus, et varietates ejus variæ. | |

| „ (Vulpes) lagopus. | |

| „ „ „ var. fuliginosa. | |

| Fiber zibethicus. | herbivorous. |

| Arvicola xanthognathus. | |

| „ Pennsylvanicus. | |

| „ borealis. | |

| „ (Georychus) trimucronatus. | |

| „ „ Hudsonius. | |

| „ „ Grœnlandicus. | |

| Arctomys (Spermophilus) Parryi. |

* Lachesis Lapponica, p. 145.

d

[page] xxvi

| Lepus glacialis. | Principal food the dwarf-birch. |

| Cervus tarandus, var. arctica. | Graminivorous, or more commonly lichenivorous. |

| Ovibos moschatus. |

A belt of low primitive rocks extends from the Barren-grounds to the northern shores of Lake Superior. It is about two hundred miles wide, and as it becomes more southerly, it recedes from the Rocky Mountains, and differs from the Barren-grounds, principally in being clothed with wood. It is bounded to the eastward by a narrow stripe of limestone, and beyond that there is a flat, swampy, partly alluvial district, which forms the western shores of Hudson's Bay. As far as regards the distribution of animals, the whole tract, from the western border of the low primitive rocks to the coast of Hudson's Bay, may be considered as one district, with the exception that the sea-bear seldom goes further inland than the swampy land which skirts the coast. The whole may be named the Eastern district, and the followins animals inhabit it:—

Vespertiliones, species duo vel tres ignotæ.

Sorex palustris.

„ Forsteri.

Scalops, species ignota.

Ursus Americanus.

„ maritimus. (Does not go further from the seashore than one hundred miles.)

Meles? Gulo luscus.

Mustela (Putorius) vulgaris.

„ „ erminea.

„ „ vison.

„ martes.

„ Canadensis.

Mephitis Americana, var. Hudsonica.

Lutra Canadensis.

Canis lupus, varietates variæ.

„ (Vulpes) lagopus.

„ „ fulvus.

„ „ „ var. decussata.

„ „ „ „ argentata.

Felis Canadensis.

[page] xvii

Castor fiber. Americanus et ejus varietates.

Fiber zibethicus et ejus varietates.

Arvicola xanthognathus.

„ Pennsylvanicus.

„ (Georychus) Hudsonius.

Mus leucopus.

Meriones Labradorius.

Arctomys empetra.

Sciurus (Tamias) Lysteri.

„ Hudsonius.

Pteromys Sabrinus.

Lepus Americanus.

Cervus alces.

„ tarandus, var. sylvestris.

The district just mentioned is bounded to the westward by a very flat limestone deposit, and the line of junction of the two formations is marked by a remarkable chain of rivers and lakes, among which are the Lake of the Woods, Lake Winipeg, Beaver Lake, and the middle portion of the Churchill or Missinippi River, all to the southward of the Methy portage; and the Elk River, Athapescow Lake, Slave River, Great Slave Lake, and Martin Lake, to the northward of it. The whole of this district is well wooded; it yields the fur-bearing animals most abundantly; and a variety of the bison, termed from the circumstance the wood bison, comes within its western border, in the more northern quarter. This animal has even extended its range to a particular corner, named Slave Point, on the north side of Great Slave Lake, which is also composed of limestone. The following animals may be found in the limestone tract:—

Vespertilio pruinosus.

Sorex palustris.

„ Forsteri.

Condylura longicaudata. (Southern parts only.)

Ursus Americanus.

Gulo luscus.

Mustela (Putorius) vulgaris.

„ „ erminea.

„ „ vison.

d 2

[page] xxviii

Mustela martes.

„ Canadensis.

Mephitis Americana, Hudsonica.

Lutra Canadensis.

Canis lupus occidentalis, var. grisea.

„ „ „ atra.

„ „ „ nubila.

„ „ „ Sticte.

„ (Vulpes) fulvus.

„ „ „ var. decussata.

„ „ „ argentata.

Felis Canadensis.

Castor fiber, Americanus et varietates ejus nigræ, variæ, et albæ.

Fiber zibethicus, colore interdum varians.

Arvicola xanthognathus.

„ Pennsylvanicus.

Mus leucopus.

Meriones Labradorius.

Arctomys empetra.

„ (Spermophilus) Hoodii (in the south-western limits of the district.)

Sciurus (Tamias) Lysteri (in the southern part of the district.)

„ „ quadrivittatus (middle parts of the district.)

„ Hudsonius.

„ niger (southern border of the district.)

Hystrix pilosus.

Lepus Americanus.

Cervus alces.

„ tarandus, sylvestris (only m a few spots.)

Bos Americanus.

Between this limestone district and the foot of the Rocky Mountains, there is an extensive tract of what is termed Prairie land. It is in general level, the slight inequalities of surface being imperceptible when viewed from a distance, and the traveller in crossing it must direct his course by the compass or the heavenly bodies, in the same way as if he were journeying over the deserts of Arabia. The soil is mostly dry and sandy, but tolerably fertile, and it supports a pretty thick sward of grass, which furnishes food to immense herds of the bison. Plains of a similar character, but still more extensive, have been described by the American writers as existing on the Arkansaw

[page] xxix

and Missouri Rivers. They gradually become narrower to the northward, and in the southern part of the fur countries they occupy about fifteen degrees of longitude, extending from Maneetobaw or Maneetowoopoo, and Winepegoos Lakes to the foot of the Rocky Mountains. They are partially intersected by some low ridges of hills, and also by several streams, the banks of which are wooded, and towards the outskirts of the plain there are many detached clumps of wood and picturesque pieces of water, disposed in so pleasing a manner as to give the country the appearance of a highly cultivated English park. In the central parts of the plains, however, there is so little wood that the hunters are under the necessity of taking fuel with them on their journeys, or in dry weather of making their fires of the dung of the bison. To the northward of the Saskatchewan, the country is more broken, and intersected by woody hills; and on the banks of the Peace River, the plains are of comparatively small extent, and are detached from each other by woody tracts; they terminate altogether in the angle between the River of the Mountains and Great Slave Lake. The abundance of pasture renders these plains the favourite resort of various ruminating animals. They are frequented throughout their whole extent by buffalo and wapiti. The prong-horned antilope is common on the Assinaboyn or Red River, and south branch of the Saskatchewan, and extends its range in the summer to the north branch of the latter river. The black-tailed deer, the long-tailed deer, and the grisly bear, are also inhabitants of the plains, but do not wander further to the eastward.

The following list will shew the peculiarity of the group of ferine animals which frequent the district:—

Ursus ferox.

Canis latrans.

„ (Vulpes) cinereo-argentatus.

Arctomys (Spermophilus?) Ludovicianus.

„ „ Richardsonii.

„ „ Franklinii.

„ „ Hoodii.

[page] xxx

Geomys? talpoides.

Diplostoma?

Lepus Virginianus.

Equus caballus.

Cervus alces.

„ strongyloceros.

„ macrotis.

„ leucurus.

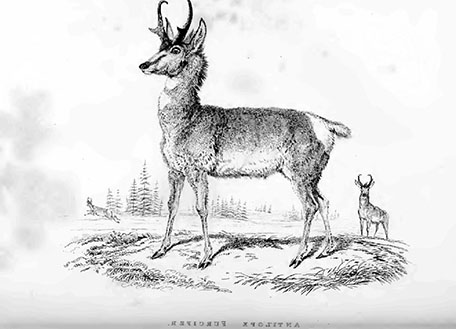

Antilope furcifer.

Bos Americanus.

The fur-bearing animals also exist in the belts of wood which skirt the rivers that flow through the plains; and the wolverene wanders over them as it does through every part of the northern extremity of America. The mephitis Americana Hudsonica breeds freely there; and the raccoon is found on the banks of the Red River, which is its most northern limit.

The following animals are found on the Rocky Mountains:—

Vespertilio subulatus.

Sorex palustris.

Ursus Americanus.

„ ferox.

Gulo luscus.

Mustela (Putorius) erminea.

„ „ vison.

„ martes.

„ Canadensis.

Mephitis?

Lutra Canadensis.

Canis lupus et ejus varietates.

„ (Vulpes) fulvus et ejus varietates.

Felis Canadensis.

Castor fiber, Americanus.

Fiber zibethicus.

Arvicola riparius.

„ xanthognathus.

„ Novoboracensis.

„ (Georychus) helvolus.

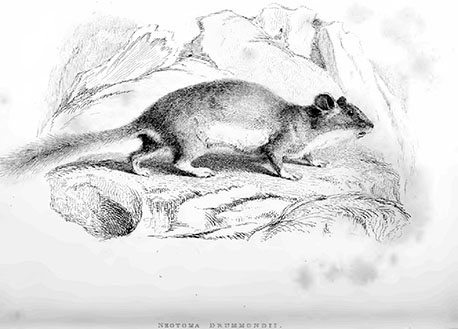

Neotoma Drummondii.

Mus leucopus.

[page] xxxi

Arctomys empetra.

„? pruinosus.

„ (Spermophilus) Parryi, var. erythrogluteia.

„ „ „ phæognatha.

„ „ guttatus?

„ „ lateralis.

Sciurus (Tamias) quadrivittatus.

„ Hudsonius.

Pteromys Sabrinus, var. alpina.

Hystrix pilosus.

Lepus Americanus.

„ glacialis.

Lepus (Lagomys) princeps.

Cervus alces.

„ tarandus? (A large kind of caribou is said to frequent the mountains, but I have seen no specimens either of the animal or of its borns.)

„ macrotis.

Capra Americana (on the highest ridges.)

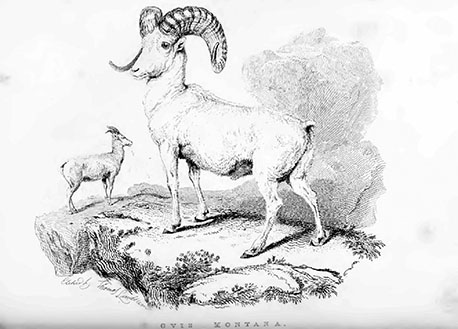

Ovis montana (on the eastern side of the ridge.)

BOS Americanus (in particular passes only.)

The country lying between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific is in general more hilly than that to the eastward; but there are some wide plains on the upper arms of the Columbia which have much of the character of the plains of the Missouri and Saskatchewan, and are inhabited by the same kind of animals. In particular the ursus ferox, canis latrans, canis cinereo-argentatus, the braro (perhaps meles Labradoria), cervus macrotis var. β. Columbiana, cervus leucurus, and aplodontia leporina, are enumerated by Lewis and Clark. Mr. Douglas also observed the condylura macroura, and several species of Felis and of Geomys and Diplostoma in that quarter. The sea-coast at the mouth of the Columbia is frequented by a species of fox very like the European one, or the red-fox of the Atlantic states of America. The Arctomys brachyurus and the Arctomys Douglasii also inhabit the banks of the Columbia; and the Arctomys Beecheyi, a species nearly allied to the latter, is found in the adjoining parts of California. The bison are supposed to have found their way across the mountains only very recently, and they are still comparatively few in numbers, and confined to certain spots.

[page] xxxii

The following brief description of New Caledonia, another district on the west of the Rocky Mountains, is extracted from Mr. Harmon's journal:—

"New Caledonia was first settled by the North-West Fur Company in 1806, and may extend from north to south about five hundred miles, and from east to west, three hundred and fifty or four hundred. The post at Stuart's Lake is nearly in the centre of it, and lies in 54½° north latitude, and 125° west longitude. In this large extent of country, there are not more than five thousand Indians, including men, women, and children. It is mountainous, but between its elevated parts there are pretty extensive valleys, along which pass innumerable small rivers and brooks. It contains a great number of lakes, one of which, Stuart's Lake, is about four hundred miles in circumference; and another, Nateotain Lake, is nearly twice as large. I am of opinion that about one-sixth part of New Caledonia is covered with water. There are but two large rivers. One of these, Frazer's River, is sixty or seventy rods wide, rises in the Rocky Mountains within a short distance of the source of the Peace River, and is the river which Sir Alexander Mackenzie followed for a considerable distance when he went to the Pacific Ocean in 1793, and which he took to be the Columbia. The other large river of New Caledonia is Simpson's River, which takes its origin in Webster's or Bear Lake, and, after passing through several considerable lakes, falls into Observatory Inlet. The mountains of New Caledonia are not to be compared, in point of elevation, with those that skirt the Peace River between Finlay's Branch and the Rocky Mountain portage, though there are some which are pretty lofty, and on the summits of one in particular, which is visible from Stuart's Lake, the snow lies during the whole year.

"The weather is not severely cold, except for a few days in the winter, when the mercury is sometimes as low as 32° below zero of Fahrenheit's thermometer. The remainder of the season is much milder than it is on the other side of the mountains in the same

[page] xxxiii

latitude. The summer is never very warm in the day-time; and the nights are generally cool. In every month in the year, there are frosts. Snow generally falls about the 15th of November, and is all dissolved by the 15th of May. About M'Leod's Lake the snow is sometimes five feet deep, and I imagine that this is the reason that none of the large animals, except a few solitary ones, are to be met with.

"There are a few moose; and the natives occasionally kill a black bear. Caribou are also found at some seasons. Smaller animals likewise occur, though they are not numerous. They consist of beavers, otters, lynxes, fishers, martins, minks, wolverines, foxes of different kinds, badgers, polecats, hares, and a few wolves. The fowls are, swans, bustards (anas Canadensis), geese, cranes, ducks of several kinds, partridges, &c. All the lakes and rivers are well furnished with excellent fish. They are, sturgeon, white-fish, trout, sucker, and many of a smaller kind. Salmon also visit the streams in very considerable numbers in autumn. The natives of New Caledonia we denominate Carriers; but they call themselves Tâ-cullies, which signifies people who go upon water. "

Captain Cook, in his third voyage, saw raccoons, foxes, martins, and squirrels, alive, on the coast of New Caledonia, and obtained skins of the following animals:—

Black-bear, brown-bear, glutton, grey wolf, arctic or stone fox, black fox, foxes of a yellow colour with a black tip to the tail, foxes of a deep reddish yellow intermixed with black, raccoon, land-otter, sea-otter, ermine, martins of three kinds: the common one, the pine-martin, and a larger one with coarser hair (mustela Canadensis?), lynx, spotted marmot, hares, and skin of an animal named wanshee by the natives. In addition to this list, Meares mentions moose-deer skins, and the skin of a very small species of deer, as among the articles of trade in possession of the natives at Nootka Sound.

To the north of New Caledonia there is a large projecting corner, which belongs to Russia, and has been traversed by the servants of the

e

[page] xxxiv

Fur Company of that nation; but of which no account has been given to the world, except of the coast, respecting which some information may be obtained from the narratives of Captain Cook, Kotzebue, and other voyagers. The few Indians of Mackenzie River, who have crossed the Rocky Mountains, report that, on their western side, there is a tract of barren grounds frequented by caribou and musk oxen; and the furs procured by the Russian Company indicate that woody regions, similar to those to the eastward of the mountains, also exist there.

Langsdorff gives the following list of skins contained in the principal magazine of the Russian Fur Company, on the island of Kodiak, most of them collected on the peninsula of Alaska, Cook's River, and other parts of thecontinent.

Brown and red bears, black bears, foxes black and silver-gray, (the stone fox, canis lagopus, is not found to the southward of Oonalaska), glutton, sea, river, and marsh otters, lynx, beaver, zizel marmot, common marmot, hairy hedge-hog (erinaceus ecaudatus), rein-deer, American wool-bearing animal.

The quadrupeds which inhabit the shores of the Polar Sea, are the same that are comprised in the list of the animals of the Barren Grounds. On the remote North Georgian Islands, in latitude 75°, there are nine different species of mammiferous animals, of which five are carnivorous, and four herbivorous. The following is Captain Sabine's list of them:—

| Ursus maritimus. | |

| Gulo luscus. | |

| Mustela erminea. | |

| Canis lupus. | |

| Canis lagopus. | |

| Lemmus Hudsonius. | |

| Lepus glacialis. | |

| Bos moschatus | These two animals are only summer visitors. They arrive on Melville Island towards the middle of May, and quit it on their return to the South in the end of September. |

| Cervus tarandus |

I have not enumerated the seals, moose, or whales, in any of the lists; nor have I attempted to give a description of any of them in the text, because my opportunities of examining them were too limited to

[page] xxxv

enable me to record any new facts; neither had I the means of correctly ascertaining the species.

I have, in the text, described the different species of animals, from nature, as correctly as I could; and I have chosen rather to subject myself to the charge of proxility than to become obscure by aiming at too great conciseness, because, in the course of my researches, I have felt the difficulty of ascertaining the species, from the brief characters assigned to them by the old writers. I have for the same reason in many instances repeated some of the generic characters in the account of a species, particularly in cases where any doubt respecting the genus or sub-division of the genus existed. In the account of the manners of the animals, I have borrowed freely from preceding writers; and from none more frequently or more copiously than from Captain Lyons, whose "Private Journal" contains a great fund of information respecting the northern animals. I wish it to be understood, however, that in all cases, unless where a doubt is actually expressed, or where I state that I have had no opportunity of personal observation, the remarks I have quoted are sanctioned by the information I collected on the spot. The nomenclature of colours, made use of in the description, is a modification of Werner's, contained in Mr. Syme's useful little work*. Before closing this introductory chapter, I have to discharge the agreeable duty of expressing my obligations to many gentlemen who have fostered the progress of the work. To the Right Honourable Lord Viscount Goderich my gratitude is especially due. To his attachment to the sciences I am indebted for that patronage and aid, which his high situation in his Majesty's Government enabled him to bestow, and without which this work could not have appeared. To the Right Honourable Thomas Frankland Lewis, also, I am under great obligations for the interest he has shewn in the advancement of the work, and for his kindness in forwarding my views. My gratitude is not less owing to the present Treasury Board, for the readiness with which they made the grant of money available; and to the late and

* Werner's Nomenclature of Colours, with Additions. By PATRICK SYME, Flower Painter. Edinburgh, 1821.

e 2

[page] xxxvi

present Secretaries of State for Colonial Affairs, for their kindness in forwarding my applications through their department. I have next to express my best thanks to the Governor and Committee of the Hudson's Bay Company, for granting me free access to their museum, and to the manuscript accounts of the Fur Countries, in their possession, and for the strong recommendations they transmitted to the resident Chief Factors and Chief Traders, to forward the views of the Expedition, with respect to Natural History. To Mr. Garry, the Deputy Governor of that Company, I have to offer my thanks in an especial manner, not only for his general kindness and good offices, but for the free use of his valuable library, particularly rich in the works of the early travellers in America. I have also to mention my deep sense of the kindness of the Council of the Horticultural Society, and of Joseph Sabine, Esq., Secretary to that Institution, for the opportunity of examining and describing Mr. Douglas's specimens. To Charles Koenig, Esq., of the British Museum, I am under much obligation, for the facility he afforded me of examining the specimens in that collection; and I am equally indebted to N. A. Vigors, Esq., of the Zoological Society, for his aid in the consultation of the museum under his charge. I have, lastly, to express my gratitude to Sir John Franklin, and to the Officers associated with me under his command. To the former, for the kindness with which he embraced every opportunity during the progress of the Expedition, of forwarding my views with respect to that branch of its objects, which was more particularly intrusted to me; and to Captain Back, Lieutenant Kendall, and Mr. Dease, for their active assistance in the collection of specimens. Indeed, I may, with propriety, embrace this opportunity of saying, that I had the happiness of being placed under an Officer, who was endowed with the rare union of devoted attention to the duties of his profession, and of the most sincere attachment to the interests of general science,—and that, in him, and in the Officers under his command, I met with, kind friends, whose agreeable society beguiled the tedium of a lengthened residence in the Arctic wilds.

[page xxxvii]

EXPLANATION

OF THE

REFERENCES TO AUTHORS.

| BARTON | Medical and Physical Journal, edited by Professor Barton, Philadelphia. (This work is quoted after M. Say.) |

| BEWICK | Bewick's History of Quadrupeds. 1st and 2nd editions, with wood cuts. |

| BILLINGS | Expedition to the Northern Parts of Russia, by Commodore Joseph Billings, 1785 to 1794; narrated by Martin Sauer. London, 1802. |

| BLAINVILLE | Bulletin des Sciences par la Société Philomatique, 1791 et seq. Paris. |

| BRISSON | Le Règne Animal Divisé en ix. Classes. 1 vol. in 4to. Paris, 1756. |

| BUFFON | Histoire Naturelle, Generale et Particuliere, avec la Description du Cabinet du Roi. Paris, 1749. 36 vols. in 4to. |

| CARTWRIGHT | Journal of Sixteen Years' Residence in Labrador, by G. Cartwright. 1 vol. 8vo. London. |

| CARVER | Travels in North America, by J. Carver, Esq., in the Years 1766, 1767 and 1768. London, 1778. |

| CATESBY | The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, by Mark Catesby. 2 vols. fol. with App. London, 1731 and 1743. |

| C. HAMILTON SMITH | Vide SMITH. |

| CHAMPLAIN | Voyages du Sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois. 1613. |

| CHAPLEVOIX | Histoire de la Nouvelle France, avec le Journal d'un Voyage dans l'Amerique, Septentrionale, par le P. Pierre Francois Xavier de Charlevoix, a Paris an 1777. 12mo. tom. 5. |

| CLERK of the CALIFORNIA | Vide SMITH and DRAGE. |

| CLINTON | Transactions of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York, instituted in the Year 1814. Introductory Discourse by the Hon. De Witt Clinton, LL.D., &c. 4to. New York, 1815. |

| COOK | Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, in 1776—1780, performed under the Direction of Captain Cook. London, 1784. 4to. 3 vols. |

| COXE | Account of Russian Discoveries between Asia and America, by William Coxe, A.M., F.R.S. London, 1787. |

[page] xxxviii

| CUVIER, or CUVIER, Baron | Tableau Elementaire de l'Histoire Naturelle des Animaux. 1 vol. in 8vo. Paris, |

| „ „ „ | 1798. Leçons d'Anatomie Comparée, Recueilles et Publiées, par MM. Dumeril et Duvernay. 5 vols, in 8vo. Paris, 1803—1805. |

| „ „ „ | Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles de Quadrupedes. 4 vols, in 4to. Paris, 1812. |

| „ „ „ | Le Règne Animal Distribue d'après sur Organisation, par M. Le Chr. Cuvier. 4 vols. 8vo. Paris, 1817. |

| CUVIER, FRED | Histoire Naturelles des Mammifères. En folio. |

| DE MONTS | Vide MONTS. |

| DENYS | Histoire de l'Amerique. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| DESMAREST | Mammalogie en Description des Especes des Mammifères, par M. A. G. Desmarest. 4to. Paris, 1820. |

| DIXON | A Voyage round the World, in the Years 1785, 1786, 1787, and 1788, by Captain George Dixon. London, 1789. |

| DOBBS | An Account of Hudson's Bay, by Arthur Dobbs, Esq. London, 1744 |

| DRAGE | Vide SMITH and CLERK of the CALIFORNIA. |

| DUDLEY | Philosophical Transactions, January, 1727. Of the Moose-deer in America, by Paul Dudley, Esq. |

| DU PRATZ | Vide PRATZ. |

| EDWARDS | Natural History of Birds and other rare undescribed Animals, by George Edwards. 7 vols. 4to. London, 1743. |

| ELLIS | Voyage to Hudson's Bay in the Dobbs and California, by Henry Ellis, in the year 1746 and 1747. London, 1748. 8vo. |

| ERXLEBEIN | Systema Regni Animalis. 8vo. Leipzick, 1777. |

| FABRICIUS | Fauna Groenlandica Othonis Fabricii. 1 vol. 8vo. Hafniæ et Lipsiæ, 1780. |

| FERNANDEZ | Historia Animalium, auctore Francisco Fernandez, Phillippi Secundi Primario Medico. 1 vol. 4to. An. 1651, Roma. |

| FLEMING | The Philosophy of Zoology, by John Fleming, D.D. 2 vols. 8vo. Edinburgh, 1822. |

| FORSTER | Philosophical Transactions, vol. 62. An. 1777. Descriptions of Specimens of Animals brought from Hudson's Bay, by J. Reinhold Forster. |

| FRANKLIN | Narrative of an Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea, in the Years 1819,1820, and 1821, by John Franklin, Capt. Royal Navy. 1 vol. 4to. London, 1822. |

| „ | Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1825, 1826, and 1827, by John Franklin, F.R.S., Captain Royal Navy. 1 vol 4to. London, 1828. |

| GASS | Journal of the Travels of a Corps of Discovery under Captain Lewis and Captain Clarke to the Pacific Ocean, in the Years 1804, 1805, and 1806. 8vo. By Patrick Gass. 1 vol. 8vo. London, 1808. |

| GEOFFREY | Geoffroy St. Hilaire, Annales du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris. 20 vols. in 4to. De 1822 a 1823. |

| GMELIN | Systema Naturæ Linnei, ed. 13. An. 1790. J. F. Gmelin. |

[page] xxxix

| GODMAN | American Natural History, by John D. Godman, M.D. 3 vols. 8vo. Philadelphia, 1826. |

| GRAHAM | Vide HUTCHINS. |

| GRIEVE | History of Kamskatcha, translated from the Russian of Krascheninikoff, by James Grieve, M.D. Gloucester, 1764. |

| GRIFFITH | The Animal Kingdom, by Baron Cuvier, translated by Edward Griffith, and Others. 8vo. London, An. 1827 et seq. |

| GULDENSTED | Novi Commentarii Petropolitani, 1749—1775. 20 vols. |

| HAMILTON SMITH | Vide SMITH. |

| HARLAN | Fauna Americana, being a Description of the Mammiferous Animals inhabiting North America, by Richard Harlan, M.D. 8vo. Philadelphia, 1825. |

| HARMON | A Journal of Voyages and Travels in the Interior of North America, between the 47th and 58th Degrees of Latitude, by Daniel William Harmon, a Partner in the North West Company. Andover, 1820. |

| HEARNE | Journey to the Northern Ocean, by Samuel Hearne, in the Years 1769, 1770, 1771, and 1772. London, 1807. |

| HENNEPIN | Nouvelle Decouverte d'un Tres grand Pays situè dans l'Amerique, par R. P. Louis de Hennepin. Amsterdam, 1698. |

| HENTRY | Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories, by Alexander Henry, in the Years 1760—1776. New York, 1809. |

| HERIOT | Travels through Canada, by George Heriot, Esq. London, 1807. |

| HERNANDEZ | Rerum Medicarum Novæ Hispaniæ Thesaurus Francisci Hernandez, Reccho Editore. Roma, 1651. |

| HISTOIRE DE L'AMERIQUE. | Histoire de l'Amerique Septentrionale. Tom. 2, 12mo. Amsterdam, 1723. |

| HONTAN | Vide LAHONTAN. |

| HUTCHINS | MS. Account of Hudson's Bay, written about the year 1780. Mr. Hutchins furnished much intelligence to Pennant respecting the Zoology of Hudson's Bay. In a few first sheets of this work Mr. Graham is through mistake quoted as the author of these manuscript notices. |

| JAMES | The dangerous Voyage of Captain Thomas James, for the Discovery of a North-West Passage. London, 1633, reprinted 1740. |

| JAMES | Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, under the Command of Major Long, by Edwin James. 3 vols. London, 1823. The American edition is also quoted occasionally. |

| JAMESON | Transactions of the Wernerian Society of Edinburgh, vol. iii. p. 306. Account of the Rocky Mountain Sheep, by Professor Jameson. |

| JEREMIE | Voyage au Nord. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| JOSELYN | New England. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| JOUTEL | Voyage to Mexico, by Mr. Joutel, translated from the French. London, 1719. |

| KALM | Peter Kalm's Travels in North America, translated by J.R.Foster. The abridgement in Pinkerton's collection of voyages is also quoted. |

[page ix]

| KLEIN | Isaac Theodore Klein, Quadrupedum Dispositie. 4to. Lipsiæ, 1751. |

| KRASHENINIKOFF | Vide GRIEVE. |

| LAHONTAN | Voyages dans l'Amerique de M. La Baron de la Hontan. Vol. 2 en 12mo. A la Haye, 1703. |

| LANGSDORFF | Voyages and Travels to various Parts of the World, in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, and 1807, by G. H. von Langsdorff. 2 vols. London, 1813. |

| LAWSON | History of Carolina. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| LEACH | Leach, W. Elford. Zoological Miscellany. |

| „ „ „ | Appendix to Ross's Voyage to Baffin's Bay. 1819. |

| LESSON | Manuel de Mammalogie, par Réne Primeverre Lesson. 12mo. Paris, 1827. |

| LEWIS and CLARKE | Travels to the Pacific Ocean in 1804, 1805, and 1806, by Captains Lewis and Clarke. 3 vols. 8vo. London, 1807. |

| LICHTENSTEIN | Voyage a Boukhara, par M. Le Baron Georges de Meyendorff, en 1820. Paris, 1826. Description, par M. Lichtenstein des Animaux Recueilles dans le Voyage, par M. Eversman. |

| LINN | Systema Naturæ, Carolo a Linnè. Ed. xii. 1766. |

| „ „ „ | Fauna Suecica. 8vo. 1746. |

| LINN. GMELIN | Systema Naturæ Linnei. Ed. xiii. Cura Gmelini, Leipsig, 1788. |

| LONG'S JOURNEY | Vide JAMES. |

| LYON | Private Journal of Captain G. F. Lyon during a Voyage of Discovery under Captain Parry. 8vo. London, 1824. |

| MC GILLIVRAY | New York Medical Repository, vol. vi. p. 238. Account of the Mountain Ram, by William Mc Gillivray. 1803. |

| MACKENZIE (SIR ALEX.) | Travels to the Polar Sea and to the Pacific Ocean, in the Years 1789—1791, by Alexander Mackenzie. London. |

| MACKENZIE (SIR GEORGE) | Travels in Iceland. |

| MARTEN | Voyage to Spitzbergen and Greenland, by F. Marten. 8vo. London, 1711. |

| MEARS | Voyages to the North-West Coast of America in 1788 and 1789, by John Meares, Esq. 4to. London, 1790. |

| MEYENDORFF | Vide LICHTENSTEIN. |

| MITCHILL | Medical Repository of New York. An. 1821. (Quoted from M. Say.) |

| MONTS, DE | Nova Francia. The three last voyages of Monsieur de Monts, of M. Pontgrave, and of M. De Poutrincourt, into La Cadia. London. |

| ORD | Guthrie's Geography, American Edition. Philadelphia. (Quoted from Harlan.) |

| „ | Journal of the Academy of Sciences of Philadelphia. Vol. iv. p. 305. |

| PALISOT DE BEAUVAIS | Bulletin des Sciences par la Société Philomatique depuis, 1791. Paris. |

| PALLAS | Novæ Species Quadrupedum e Glirium Ordine. Erlang. In 4to. |

| „ | Spicelegia Zoologica. Berolini, 1767—1780. |

| „ | Voyage dans Plusieurs Provinces de l'Empire de Russie. 8 vols, in 8vo. Paris. |

[page] xli

| PARRY | Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, performed in the Years 1819, 1820, in His Majesty's Ships the Hecla and Griper, by William Edward Parry, R.N., F.R.S. 4to. London, 1821. |

| „ | Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage in the Years 1821, 1822, 1823, in the Fury and Hecla, by Captain William Edward Parry, R.N. F.R.S. London, 1824. |

| PENNANT | History of Quadrupeds. 3d Edition. 2 vols. 4to. London, 1793. |

| „ | Arctic Zoology. 2 vols. 4to. 1784. |

| PIKE | Travels on the Missouri and Arkansaw, by Lieutenant Pike, in 1805 and 1806. Edited by T. Rees, Esq. London, 1811. |

| PRATZ, DU | Voyage de Louisiana. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| RAFINESQUE or RAFINESQUE-SMALTZ. | Annals of Nature. (Quoted from Desmarest.) |

| „ „ | American Monthly Magazine, (Ditto). |

| „ „ | Precis, les Decouvertes Somiologiques. En 18mo. Palerme, 1814. |

| RAY | Raii Synopsis Methodica Animalium. 8vo. Londini, 1693. |

| RICHARDSON | Appendix to Captain Parry's Second Voyage. London, 1824. |

| „ | Zoological Journal. 1828, 1829. London. |

| SABINE, (JOSEPH) | Franklin's First Journey. Zool. Appendix. London, 1822. |

| „ „ | Linnean Transactions, vol. xiii. |

| SABINE, (Capt. EDWARD) | Supplement to the Appendix of Captain Parry's First Voyage in 1819, 20. London, 1824. |

| SAGARD-THEODAT | Vide THEODAT. |

| SAUER | Vide BILLINGS. |

| SAY | His Zoological Notices, in the Notes to Long's Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, are quoted. Vide JAMES. |

| SCHOOLCRAFT | Travels to the Sources of the Mississippi River, by H.R. Schoolcraft. Albany, 1821. |

| SCHREBER | Histoire des Mammifères. In 4to. Erlangen, 1775, et suiv. |

| SHAW | General Zoology, by George Shaw, M.D., F.R.S. 16 vols. 8vo. London, 1800–1812. |

| SMITH, (CAPTAIN) | Voyage by Hudson's Straights, in the California, by Captain Francis Smith; by the Clerk of the California, in 1746 and 1747. (The Clerk's name was Drage. Ellis, the Agent for the Proprietors in the Dobbs, the consort of the California, gives another account of the voyage, but less full on points of Natural History.) Vide Ellis. |

| SMITH, (C. H.) | His papers in the Linnean Transactions, and in Griffith's Translation of Cuvier, are quoted. |

| STELLER | Acta Petropolitana. |

| TEMMINCK | Monographies de Mammalogie et Tableau Methodique des Mammifères. 4to. Paris, 1827. |

f

[page] xlii

| THEODAT | Histoire du Canada, par le F. Gabriel Sagard-Theodat. 12mo. Paris, 1636. |

| TRAILL | Voyage to Greenland, by J. Scoresby. Appendix. |

| UMFREVILLE | Present State of Hudson's Bay, by Edward Umfreville. London, 1790. 8vo. |

| ULLOA | Voyage. (Quoted from Pennant.) |

| WARDEN | Account of the United States of North America. Edinburgh, 1819. |

| VOYAGE DE L'AMERIQUE | Voyage de l'Amerique dans le Vaisseau Pelican. En 1697. Amsterdam, 1723. |

[page xliii]

SYSTEMATIC LIST OF THE SPECIES.

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | VESPERTILIO PRUINOSUS. The Hoary Bat | 1 |

| 2. | „ SUBULATUS. Say's Bat | 3 |

| 3. | SOREX PALUSTRIS. The American Marsh-Shrew | 5 |

| 4. | „ FORSTERI. Forster's Shrew-Mouse | 6 |

| 5. | „ PARVUS. The Small Shrew-Mouse | 8 |

| 6. | SCALOPS CANADENSIS. The Shrew-Mole | 9 |

| 7. | CONDYLURA LONGICAUDATA. The Long-tailed Star-nose | 13 |

| 83. | „ MACROURA | 284 |

| 8. | URSUS AMERICANUS. The American Black Bear | 14 |

| 9. | „ ARCTOS? AMERICANUS. The Barren-ground Bear | 21 |

| 10. | „ FEROX. The Grisly Bear | 24 |

| 10bis | „ MARITIMUS. The Polar or Sea Bear | 30 |

| 11. | PROCYON LOTOR. The Raccoon | 36 |

| 12. | MELES LABRADORIA. The American Badger | 37 |

| 13. | GULO LUSCUS. The Wolverene | 41 |

| 14. | MUSTELA (PUTORIUS) VULGARIS. The Common Weasel | 45 |

| 15. | „ „ ERMINEA. The Ermine, or Stoat | 46 |

| 16. | „ „ VISON. The Vison-Weasel | 48 |

| 17. | „ MARTES. The Pine-Marten | 51 |

| 18. | „ CANADENSIS. The Pekan or Fisher | 52 |

| „ var. alba. White Pekan | 54 | |

| 19. | MEPHITIS AMERICANA, HUDSONICA. Hudson's Bay Skunk | 55 |

| 20. | LUTRA CANADENSIS. The Canada Otter | 57 |

| 21. | „ (ENHYDRA) MARINA. The Sea Otter | 59 |

f 2

[page] xliv

| PAGE | ||

| 22. | CANIS LUPUS, OCCIDENTALS. The American Wolf | 60 |

| var. A. LUPUS GRISEUS. The Common Gray Wolf | 66 | |

| B. „ ALBUS. The White Wolf | 68 | |

| C. „ STICTE. The Pied Wolf | 68 | |

| D. „ NUBILUS. The Dusky Wolf | 69 | |

| E. „ ATER. The Black American Wolf | 70 | |

| 23. | CANIS LATRANS. The Prairie Wolf | 73 |

| 24. | „ FAMILIARIS. The Domestic Dog | 75 |

| var. A. BOREALIS. The Esquimaux Dog | 75 | |

| B. LAGOPUS. The Hare-Indian Dog | 78 | |

| C. CANADENSIS. The North American Dog | 80 | |

| D. NOVÆ CALEDONIÆ. The Carrier Indian Dog | 82 | |

| 25. | CANIS (VULPES) LAGOPUS. The Arctic Fox | 83 |

| var. β. FULGINOSA. The Sooty Fox | 89 | |

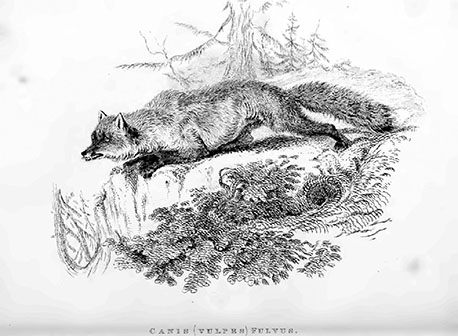

| 26. | CANIS (VULPES) FULVUS. The American Fox | 91 |

| var. β. DECUSSATA. The American Cross Fox | 93 | |

| γ. ARGENTATA. The Black or Silver Fox | 94 | |

| 27. | CANIS (VULPES) VIRGINIANUS. The Gray Fox | 96 |

| 28. | „ (VULPES VULGARIS,) VULPES? The Fox | 97 |

| 29. | CANIS (VULPES) CINEREO-ARGENTATUS. The Kit Fox | 98 |

| 30. | FELIS CANADENSIS. The Canada Lynx | 101 |

| 31. | „ RUFA. The Bay Lynx | 103 |

| 32. | „ FASCIATA. The Banded Lynx | 104 |

| 33. | CASTOR FIBER, AMERICANUS. The American Beaver | 105 |

| var. B. „ NIGRA. The Black Beaver | 113 | |

| C. „ VARIA. The Spotted Beaver | 114 | |

| D. „ ALBA. The White Beaver | 114 | |

| 34. | FIBER ZIBETHICUS. The Musquash | 115 |

| var. B. „ NIGRA. The Black Musquash | 119 | |

| C. „ MACULOSA. The Pied Musquash | 119 | |

| D. „ ALBA. The White Musquash | 119 | |

| 35. | ARVICOLA RIPARIUS. The Bank Meadow-Mouse | 120 |

| 36. | „ XANTHOGNATHUS. The Yellow-cheeked Meadow-Mouse | 122 |

[page] xlv

| PAGE | ||

| 37. | ARVICOLA PENNSYLVANICUS. Wilson's Meadow-Mouse | 124 |

| 38. | „ NOVOBORACENSIS. The Sharp-nosed Meadow-Mouse | 126 |

| 39. | „ BOREALIS. The Northern Meadow-Mouse | 127 |

| 40. | „ (GEORYCHUS) HELVOLUS. The Tawny Lemming | 128 |

| 41. | „ „ TRIMUCRONATUS. Back's Lemming | 130 |

| 42. | „ „ HUDSONIUS. The Hudson's Bay Lemming | 132 |

| 43. | „ „ GRŒNLANDICUS. The Greenland Lemming | 134 |

| 44. | NEOTOMA DRUMMONDII. The Rocky Mountain Neotoma | 137 |

| †. | MUS RATTUS. The Black Rat | 140 |

| †. | „ DECUMANUS. The Brown Rat | 141 |

| †. | „ MUSCULUS. The Common Mouse | 141 |

| 45. | „ LEUCOPUS. The American Field-Mouse | 142 |

| 46. | MERIONES LABRADORIUS. The Labrador Jumping-Mouse | 144 |

| 47. | ARCTOMYS EMPETRA. The Quebec Marmot | 147 |

| 48. | „? PRUINOSUS. The Whistler | 150 |

| 49. | „ BRACIIYURUS. The Short-tailed Marmot | 151 |

| †. | „ MONAX. The Wood-Chuck | 153 |

| †. | „ (SPERMOPHILUS?) LUDOVICIANUS. The Wistonwish | 154 |

| 50. | „ „ PARRYI. Parry's Marmot | 158 |

| Var. β. ERYTIIROGLUTEIA | 161 | |

| „ γ. PHÆOGNATHA | 161 | |

| 51. | ARCTOMYS (SPERMOPHILUS) GUTTATUS? The American Souslik | 162 |

| 52. | „ „ RICHARDSONII. The Tawny Marmot | 164 |

| 53. | „ „ FRANKLINII. Franklin's Marmot | 168 |

| †. | „ „ BEECHEYI. Beechey's Marmot | 170 |

| 54. | „? „? DOUGLASII. Douglas's Marmot | 172 |

| 55. | „ „ LATERALIS. Say's Marmot | 174 |

| 56. | „ „ HOODII. The Leopard Marmot | 177 |

| 57. | SCIURUS (TAMIAS) LYSTERI. The Hackee | 181 |

| 58. | „ „ QUADRIVITTATUS. The Four-banded Pouched-Squirrel | 184 |

| 59. | „ HUDSONIUS. The Chickaree | 187 |

| „ Var. β. The Columbian Pine-Squirrel | 190 | |

| 60. | „ NIGER. The Black Squirrel | 191 |

[page] xlvi

| PAGE | ||

| 61. | PTEROMYS SABRINUS. The Severn River Flying Squirrel | 193 |

| Var. β. ALPINA. The Rocky-Mountain Flying-Squirrel | 195 | |

| GEOMYS. Generic characters | 197 | |

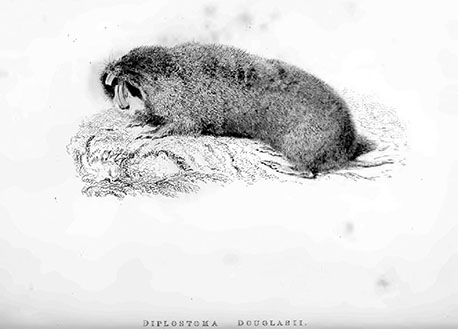

| 62. | „ DOUGLASII. The Columbia Sand-Rat | 200 |

| †. | „ UMBRINUS. Leadbeater's Sand-Rat | 202 |

| 63. | „? BURSARIUS. The Canada Pouched-Rat | 203 |

| 64. | „? TALPOIDES. The Mole-shaped Sand-Rat | 204 |

| 65. | DIPLOSTOMA BULBIVORUM. The Camas-Rat | 206 |

| APLODONTIA. Generic characters | 210 | |

| 66. | APLODONTIA LEPORINA. The Sewellel | 211 |

| 67. | HYSTRIX PILOSUS. The Canada Porcupine | 214 |

| 68. | LEPUS AMERICANUS. The American Hare | 217 |

| 69. | „ GLACIALIS. The Polar Hare | 221 |

| 70. | „ VIRGINIANUS. The Prairie Hare | 224 |

| 71. | „ (LAGOMYS) PRINCEPS. The Little-Chief Hare | 227 |

| †. | LIPURA HUDSONIA. The Tail-less Marmot | 230 |

| 72. | EQUUS CABALLUS, The Horse | 231 |

| 73. | CERVUS ALCES. The Moose-Deer | 232 |

| 74. | „ TARANDUS. The Caribou | 238 |

| Var. α. ARCTICA | 241 | |

| „ β. SYLVESTRIS | 250 | |

| 75. | „ STRONGYLOCEROS. The Wapiti | 251 |

| 76. | „ MACROTIS. The Black-tailed Deer | 254 |

| Var. β. COLUMBIANA | 257 | |

| 77. | „ LEUCURUS. The Long-tailed Deer | 258 |

| 78. | ANTILOPE FURCIFER. The Prong-Horned Antilope | 261 |

| 79. | CAPRA AMERICANA. The Rocky Mountain Goat | 268 |

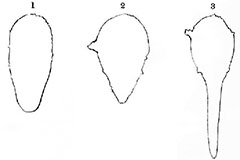

| 80. | OVIS MONTANA. The Rocky Mountain Sheep | 271 |

| 81. | OVIBOS MOSCHATUS. The Musk-Ox | 275 |

| 82. | Bos AMERICANUS. The American Bison | 279 |

[page break]