[frontispiece]

[page i]

POLYNESIAN RESEARCHES,

DURING

A RESIDENCE OF NEARLY SIX YEARS

IN THE

SOUTH SEA ISLANDS;

INCLUDING

DESCRIPTIONS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY AND SCENERY OF THE

ISLANDS—WITH REMARKS ON THE HISTORY, MYTHOLOGY,

TRADITIONS, GOVERNMENT, ARTS, MANNERS,

AND CUSTOMS OF THE

INHABITANTS.

BY

WILLIAM ELLIS,

MISSIONARY TO THE SOCIETY AND SANDWICH ISLANDS, AND AUTHOR

OF THE "TOUR OF HAWAII."

"In so vast a field, there will be room to acquire fresh knowledge for centuries to come, coasts to survey, countries to explore, inhabitants to describe, and perhaps to render more happy." COOK E.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

FISHER, SON, & JACKSON, NEWGATE STREET,

M,DCCC,XXIX.

[page ii]

[page iii]

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

CHAP. I.

Voyage to Raiatea—Appearance of the coral reefs—Breaking of the surf——Islets near the passage to the harbours—Landing at Tipaemau—Description of the islands—Arrival at Vaóaara—Singular reception—Native salutations—Improvement of the settlement—Traditionary connexion of Raiatea with the origin of the people—General account of the South Sea Islanders—Physical character, stature, colour, expression, &c. Mental capacity, and habits—Aptness to receive instruction—Moral character—Hospitality—Extensive and affecting moral degradation—Its enervating influence—Longevity—Comparative numbers of the inhabitants—Indications and causes of depopulation—Beneficial tendency of Christianity Page 1 to 36.

CHAP. II.

Origin of the inhabitants of the South Sea Islands—Traditions—Legend of Taaoroa and Hina—Resemblance to Jewish history—Coincidences in language, mythology, &c. with the language, &c. of the Hindoos and Malays, Madagasse, and South Americans—Difficulty of reaching the islands from the west—Account of different native voyages—Geographical extent over which the Polynesian race and language prevail—Account of the introduction of animals—Predictions of their ancient prophets relating to the arrival of ships—Traditions of the deluge, corresponding with the accounts in sacred and profane writings Page 37 to 63.

CHAP. III.

General state of society—Former modes of living—Proposed improvement in the native dwellings—Method of procuring lime from the coral-rock—First plastered houses in the South Sea Islands—Progress of improvement—Appearance of the settlement—Described by Captain Gambier—Sensations produced by the scenery, &c.—Irregularity of the buildings—Public road—Effect on the surrounding country—Duration of native habitations—Building for public worship—Division of public labour—Manner of fitting up the interior—Satisfaction of the people—Chapel in Raiatea—Native chandeliers—Evening services Page 64 to 89.

CHAP. IV.

Schools erected in Huahine—Historical facts connected with the site of the former building—Account of Mai, (Omai)—His visit to England with Captain Furneux—Society to which he was introduced—Objects of his attention—Granville Sharp—His return with Captain Cook—Settlement in Huahine—His subsequent conduct—Present proprietors of the Beritani in Huahine—House for hidden prayer—Cowper's lines on Omai—Royal Mission Chapel in Tahiti—Its dimensions, furniture, and appearance—Motives of the king in its erection—Description of native chapels—Need of clocks and bells—Means resorted to for supplying their deficiency—Attendance on public worship—Habits of cleanliness—Manner of wearing the hair—Process of shaving—Artificial flowers—Native toilet Page 90 to 119.

[page] iv

CHAP. V.

Improved circumstances of the females—Instruction in needlework—Introduction of European clothing—Its influence upon the people—Frequent singularity of their appearance—Development of parental affection—Increased demand for British manufactures—Native hats and bonnets—Reasons for encouraging a desire for European dress, &c.—Sabbath in the South Sea Islands—Occupations of the preceding day—Early morning prayer-meetings—Sabbath schools—Order of divine service—School exercises—Contrast with idolatrous worship Page 120 to 148.

CHAP. VI.

Public assemblies during the week—Questional and conversational meeting—Topics discussed—The seat of the thoughts and affections—Duty of prayer—Scripture biography and history—The first parents of mankind—Paradise—Origin of moral evil—Satanic influence—A future state—Condition of those who had died idolaters—The Sabbath—Inquiries respecting England—The doctrine of the resurrection—Visits to Maeva—Description of the aoa—Legend connected with its origin—Considered sacred—Cloth made with its bark—Manufacture of native cloth—Variety of kinds—Methods of dyeing—Native matting—Different articles of household furniture Page 149 to 184.

CHAP. VII.

Station at Maeva—Appearance of the lake and surrounding scenery—Ruins of temples, and other vestiges of idolatry—General view of Polynesian mythology—Ideas relative to the origin of the world—Polytheism—Traditionary theogony—Taaroa supreme deity—Different orders of gods—Oro, &c. gods of the wind, the ocean, &c.—Gods of artificers and fishermen—Oramatuas, or demons—Emblems—Images—Uru, or feathers—Temples—Worship—Prayers—Offerings—Sacrifices—Occasional and stated festivals and worship—Rau-mata-vehi-raa Maui-fata—Rites for recovery from sickness—Offering of first-fruits—The Pae Atua—The ripening of the year, a religious ceremony—Singular rites attending its close Page 185 to 218.

CHAP. VIII.

Description of Polynesian idols—Human sacrifices—Anthropophagism—Islands in which it prevails—Motives and circumstances under which it is practised—Tradition of its existence in Sir Charles Sanders' Island—Extensive prevalence of Sorcery and Divination—Views of the natives on the subject of satanic influence—Demons—Imprecations—Modes of incantation—Horrid and fatal effects supposed to result from sorcery—Impotency of enchantment on Europeans—Native remedies for sorcery—Native oracles—Means of inspiration—Effects on the priest inspired—Manner of delivering the responses—Circumstances at Rurutu and Huahine—Intercourse between the priest and the god—Augury by the death of victims—Divination for the detection of theft Page 219 to 241.

CHAP. IX.

Increased desire for books—Application from the blind—Account of Hiro, an idolatrous priest—Methods of distributing the Scriptures—Dangerous voyages—Motives influencing to desires for the Scriptures—Character of the translation—Cause of delay in baptizing the converts—General view of the ordinance—Baptism of the king—Preparatory instructions—First baptism in Huahine—Mode of applying the water—Introduction

[page] v

of Christian names—Baptism of infants—Impression on the minds of the parents—Interesting state of the people—Extensive prevalence of a severe epidemic Page 242 to 269.

CHAP. X.

Former diseases in the islands comparatively few and mild—Priests the general physicians—Native practice of physic—Its intimate connexion with sorcery—Gods of the healing art—The tuabu, or broken back—Insanity—Native warm-bath—Oculists—Surgery—Setting a broken neck and back—The operation of trepan—Native remedies superseded by European medicine—Need of a more abundant supply—Former cruelty towards the sick—Parricide—Present treatment of invalids—Visits to Maeva—Native fisheries—Prohibitions—Enclosures—Salmon and other nets—Use of the spear—Various kinds of hooks and lines—The vaa tira—Fishing by torch-light—Instance of native honesty—Death of Messrs. Tessier and Bicknell—Dying charge to the people—Missionary responsibility Page 270 to 301.

CHAP. XI.

General view of a Christian church—Uniformity of procedure in the different stations—Instructions from England—Preparatory instructions Distinct nature of a Christian church—Qualifications and duties of communicants—The sacrament of the Lord's Supper—Formation of the first church of Christ in the Leeward Islands—Administration of the ordinance—Substitute for bread—Order of the service—Character, experience, and peculiarities of the communicants—Buaiti—Regard to the declarations of scripture—Instances of the power of conscience—Manner of admitting church members—Appointment of deacons—Great attention to religion Page 302 to 339.

CHAP. XII.

Government of the South Sea Islands monarchical and arbitrary—Intimately connected with idolatry—Different ranks in society—Slavery—The proprietors of land—The regal family—Sovereignty hereditary—Abdication of the father in favour of the son—Distinctions of royalty—Modes of travelling—Sacredness of the king's person—Homage of the people—Singular ceremonies attending the inauguration of the king—Language of the Tahitian court—The royal residences—Causes, &c.—Sources of revenue—Tenure of land—Division of the country—National councils—Forfeiture of possessions Page 340 to 364.

CHAP. XIII.

Power of the chiefs and proprietors of land—Banishment and confiscation—The king's messenger—The main, an emblem of authority—Ancient usages in reference to crime, &c.—Fatal effects of jealousy—Seizure of property—Punishment of theft—Public works—Supplies for the king—Despotic rapacity—Extortion of the king's servants—Unorganized state of civil polity—Desire a code of Christian laws—Advice and conduct of the Missionaries—Preparation of the laws—Public enactment by the king in a national assembly at Tahiti—Capital punishments—Manner of conducting public trials—Establishment of laws in Raiatea—Preparation of those for Huahine Page 365 to 390.

CHAP. XIV.

Pomare's proposed restrictions on barter, rejected by the chiefs of the Leeward Islands—Voyage to Eimeo—Departure for Tahiti—Danger during the night—Arrival at Burder's Point—State of the settlement—Papeete—Mount Hope—Interview with the king—Revision of the laws—Approval

[page] vi

of the queen—Arrival of the Hope from England—Influence of letters, &c—Return to Eimeo—Embarkation for the Leeward Islands—A night at sea—Appearance of the heavens—Astronomy of the natives—Names of the stars—Divisions and computation of times, &c.—Tahitian numerals—Extended calculation—Arrival in Huahine Page 391 to 425.

CHAP. XV.

Promulgation of the new code of laws in Huahine—Literal translation of the laws on Murder—Theft—Trespass—Stolen property—Lost property—Barter—Sabbath-breaking—Rebellion—Bigamy, &c.—Divorce, &c.—Marriage—False accusation—Drunkenness—Dogs—Pigs—Conspiracy——Confessions—Revenue for the king and chiefs—Tatauing—Voyaging—Judges and magistrates—Regulations for judges, and trial by jury—Messengers or peace-officers—Manner of conducting public trials—Character of the Huahine code—Reasons for dissuading from capital punishments—Omission of oaths—Remarks on the different enactments—Subsequent amendments and enactments relative to the fisheries—Landmarks—Land rendered freehold property—First Tahitian parliament—Regulations relating to seamen deserting their vessels—Publicity of trials—Effects of the beneficial laws Page 426 to 460.

CHAP. XVI.

Visit from the Windward Islands—Opposition to the moral restraints of Christianity—Tatauing prohibited by the chiefs—Account of the dye, instruments, and process of tatauing—Variety of figures or patterns—The operation painful, and frequently fatal—Revival of the practice—Trial and penalty of the offenders—Rebellion against the laws and government—Public assembly—Address of Taua—Departure of the chiefs and people from the encampment of the king's son—Singularity of their dress and appearance—Interview between the rival parties—Return of Hautia and the captives—Frequency of war in the South Sea Islands—Polynesian war-god—Religious ceremonies and human sacrifices, prior to the commencement of hostilities—National councils—Mustering of forces—Emblems of the gods taken to the war—Strength of their fleets or armies—The battle of Hooroto—Women engaging in war—Martial music—Modes of attack—Single combats, challenges, &c.—The rauti, or orators of battle—Sacrifice of the first prisoner—Use of the sling Page 461 to 491.

CHAP. XVII.

Singular custom of the chiefs in marching to battle—Sanguinary and exterminating character of their engagements—Desolation of the country—Estimation in which fighting men were held—Weapons—Dress—Ornaments—Various kinds of helmet, &c.—Ancient arms, &c. susperseded by the introduction of fire-arms—Former ideas respecting the musket, &c.—Divination or augury—Savage and merciless conduct of the victors—Existence of wild men in the mountains—Account of one at Bunauïa who had fled from the field of battle—Treatment of the captives and the slain—Division of the spoil, and appropriation of the country—Maritime warfare—Encampments—Fortifications—Instance of patriotism—Methods of concluding peace—Religious ceremonies and festivities that followed—Present sentiments of the people in reference to war—Triumph of the principles of peace—Incident at Rurutu Page 492 to 520.

[page] vii

CHAP. XVIII.

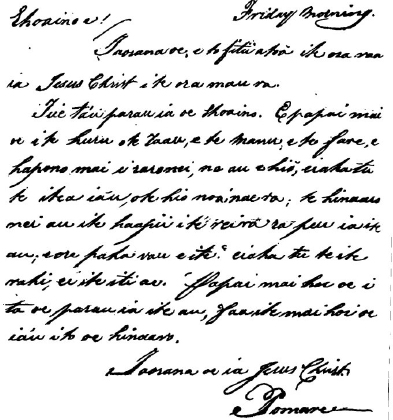

Arrival of the deputation at Tahiti—Visit to Huahine—Pomare's death—Notice of his ancestry—Description of his person—His mental character and habits—Perseverance and proficiency in writing—His letters to England, &c.—Fac-simile of his hand-writing, and translation of his letter on the art of drawing—Estimation in which he was held by the people—Pomare, the first convert to Christianity—His commendable endeavours to promote its extension—Declension during the latter part of life—His friendship for the Missionaries uniform—His aid important—Circumstances connected with his death—Accession of his son Pomare III. to the government—Coronation of the infant king—His removal to the South Sea academy—Encouraging progress in learning—Early and lamented death—The extensive use of letters among the islanders—Writing on plantain leaves—Value of writing paper, &c.—The South Sea academy, required by the state of native society—The trial peculiar to Mission families among uncivilized nations—Advantages connected with the visits of Missionaries' children to civilized countries Page 521 to 551.

CHAP. XIX.

Voyage to Borabora—Appearance of the settlement—Description of the island—Geological peculiarities of Borabora, Maurua, &c.—New settlement in Raiatea—Arrival of the Dauntless—Designation of native Missionaries—Voyage to the Sandwich Islands—Marriage of Pomare and Aimata—Former usages observed in marriage contracts—Betrothment—Ancient usages in the celebration of marriage—Resort to the temple—Address of the priest—Proceedings of the relatives—Prevalence of polygamy—Discontinued with the abolition of idolatry—Christian marriage—Advantageous results—Female occupations—Embarkation for England—Visit to Fare—Improvement of the settlement—Visit to Rurutu and Raivavai—Propagation of Christianity by native converts—Final departure from the South Sea Islands Page 552 to 576.

[page] viii

PLATES IN VOL. II.

| Idols worshipped by the Inhabitants of the South Sea Islands, (described p. 219) | to face the Title |

| Eastern part of Fa-re Harbour, in Huahine | 79 |

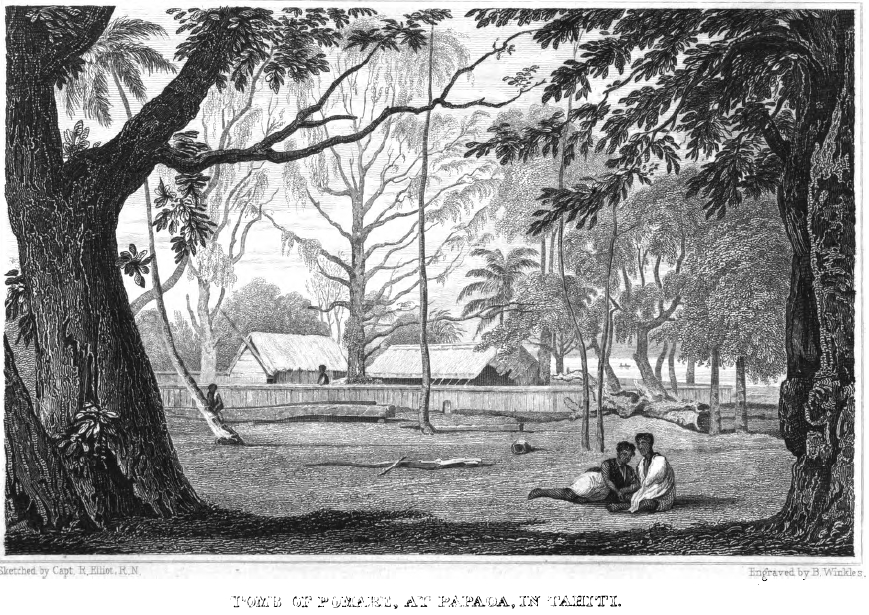

| Tomb of Pomare, at Papaoa, in Tahiti | 535 |

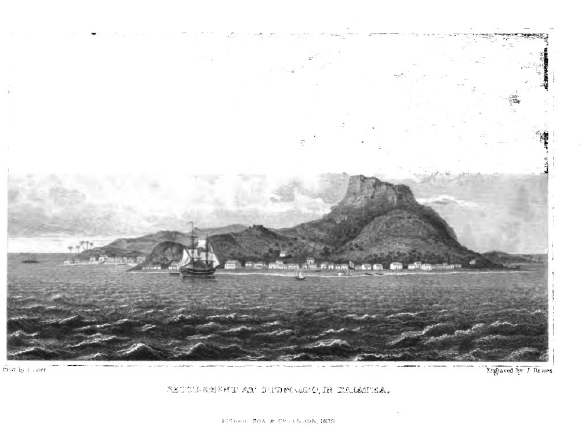

| Settlement of Utumaoro, in Raiatea | 556 |

WOOD ENGRAVINGS.

| Tahitian Cloth Mallet | in page 173 |

| Various Tools and Utensils | 181 |

| National Temple | 207 |

| Altar, with Offerings | 212 |

| Altar and Unus | 217 |

| Fishing Canoe | 297 |

| Fac-simile, and Translation, of Pomare's Letter | 530 |

[page 1]

POLYNESIAN RESEARCHES.

CHAP. I.

Voyage to Raiatea—Appearance of the coral reefs—Breaking of the surf—Islets near the passage to the harbours—Landing at Tipaemau—Description of the islands—Arrival at Vaóaara—Singular reception—Native salutations—Improvement of the settlement—Traditionary connexion of Raiatea with the origin of the people—General account of the South Sea Islanders—Physical character, stature, colour, expression, &c.—Mental capacity, and habits—Aptness to receive instruction—Moral character—Hospitality—Extensive and affecting moral degradation—Its enervating influence—Longevity—Comparative numbers of the inhabitants—Indications and causes of depopulation—Beneficial tendency of Christianity.

DURING the first years of our establishment in Huahine, frequent voyages were necessary; and, early in 1819, circumstances rendered it expedient that we should revisit Raiatea. As we expected to be absent for several weeks, Mrs. Barff and Mrs. Ellis accompanied us; Mr. Orsmond was returning to his station, and we embarked in his boat, although it was scarcely large enough to contain our party and half a dozen native rowers. The morning on which we sailed was fine; the sea gently rippled with the freshening breeze,

II. B

[page] 2

which was fair and steady, without being violent. Our voyage was pleasant; and soon after two in the afternoon of the same day, we entered an opening in the reef, a few miles to the northward of that leading to Opoa. This entrance is called by the inhabitants Tipae mau, True, or permanent, landing (place.)

The coral reef, around the eastern shores of Raiatea and Tahaa, often exhibits one of the most sublime and beautiful marine spectacles that it is possible to behold. It is generally a mile, or a mile and a half, and occasionally two miles, from the shore. The surface of the water within the reef is placid and transparent; while that without, if there be the slightest breeze, is considerably agitated; and, being unsheltered from the wind, is generally raised in high and foaming waves.

The trade-wind, blowing constantly towards the shore, drives the waves with violence upon the reef, which is from five, to twenty or thirty yards wide. The long rolling billows of the Pacific, extending sometimes, in one unbroken line, a mile or mile and a half along the reef, arrested by this natural barrier, often rise ten, twelve, or fourteen feet above its surface; and then, bending over it their white foaming tops, from a graceful liquid arch, glittering in the rays of a tropical sun, as if studded with brilliants. But, before the eyes of the spectator can follow the splendid aqueous gallery which they appear to have reared, with loud and hollow roar they fall in magnificent desolation, and spread the gigantic fabric in forth and spray upon the horizontal and gently broken surface of the coral.

In each of the island, and opposite the large valleys, through which a stream of water falls into the ocean, there is usually a break, or opening, in the line of reef

[page] 3

that surrounds the shore—a most wise and benevolent provision for the ingress and egress of vessels, as well as a singular phenomenon in the natural history of these marine ramparts to the islands. Whether the current of fresh water, constantly flowing from the rivers to the ocean, prevents the tiny architects from building their concentric walls in one continued line, or whether in the fresh water itself there is any quality inimical to the growth or increase of coral, is not easy to determine; but it is a remarkable fact, that few openings occur in the reefs which surround the South Sea Islands, excepting opposite those parts of the shore from which streams of fresh water flow into the sea. Reefs of varied, but generally circumscribed extent, are frequently observed within the large outer barrier, and near the shore, or mouth of the river; but they are formed in shallow places, and the coral is of a different and more slender kind, than that of which the larger reef, rising from the depths of the ocean, is usually composed. There is no coral in the lagoons of the large islands.

The openings in the reefs around Sir Charles Sander's Island, Maurua, and other low islands, are small and intricate, and sometimes altogether wanting, probably because the land, composing these islands, collects but a scanty portion of water; and, if any, only small and frequently interrupted streams flow into the sea. The openings in the reefs around the larger islands, not only afford direct access to the indentations in the coast, and the mouths of the valleys, which form the best harbours,—but secure to shipping a supply of fresh water, in equal, if not greater abundance, than it could be procured in any other part of the island. The circumstance, also, of the rivers near the harbours flowing

[page] 4

into the sea, affords the greatest facility in procuring fresh water, which is so valuable to seamen.

The openings in the reef, on the eastern side of Raiatea, are not only serviceable to navigation, but highly ornamental, adding greatly to the beauty of the surrounding scenery. At the Ava Moa, or Sacred Entrance leading to Opoa, there is small island, on which a few cocoa-nut trees are growing. At Tipaemau there are two, one on each side of the opening, rising from the extremity of the line of reef. The little islets, elevated three or four feet above the water, are clothed with shrubs and verdure, and adorned with a number of lofty cocoa-nut trees. At Te-Avapiti, several miles to the northward of Tipaemau, and opposite the Missionary settlement—where, as its name indicates, are two openings—there are also two beautiful, green, and woody islands, on which the lowly hut of the fisherman, or of the voyager waiting for a favourable wind, may be often seen. Two large and very charming islands adorn the entrance at Tomahahotu, leading to the island of Tahaa. The largest of these is not more than half a mile in circumference, but both are covered with fresh and evergreen shrubs and trees.

Detached from the large islands, and viewed in connexion with the ocean rolling through the channel on the one side, or the foaming billows dashing, and roaring, and breaking over the reef on the other, they appear like emerald gems of the ocean, contrasting their solitude and verdant beauty with the agitated element sporting in grandeur around. They are useful, as well as ornamental. The tall cocoa-nuts that grow on their surface, can be seen many miles distant; and the native mariner is thereby enabled to steer directly towards

[page] 5

the spot where he knows he shall find a passage to the shore. The constant current passing the opening, probably deposited on the ends of the reef fragments of coral, sea weeds, and drift-wood, which in time rose above the surface of the water. Seeds borne thither by the waves, or wafted by the winds, found a soil on which they could germinate—decaying vegetation increased the mould—and by this process it is most likely these beautiful little fairy-looking islands were formed on the ends of the reefs at the entrance to the different harbours.

We landed on one at Tipaemau, partook of some refreshment under the shade the shrubbery afforded, while out boat's crew climbed the trees, and afterwards made an agreeable repast on the nuts which they gathered. We planted, as memorials of our visit, the seeds of some large ripe oranges, which we had brought with us; then launched out boat, and prosecuted out voyage within the reef, towards the other side of the island, where the Missionary settlement was then established. This part of our voyage, for twelve or fourteen miles, was most delightful. The beauty of the wooded or rocky shores now appeared more rich and varied than before; the stillness of the smooth waters around was only occasionally disturbed by the passage of a light, nautilus-like canoe, with its little sail of white native cloth, or the rapid flight of a shoal of flying-fish, which, when the dashing of our oars or the progress of our boat intercepted their course or awakened their alarm, sprang from their native element, and darted along, three or four feet above the water.

[page] 6

Ioretea, the Ulitea of Captain Cook, or, as it is now more frequently called by the natives, Raiatea, is the largest of the Society Islands. Its form is somewhat triangular, and its circumference about fifty miles. The mountains are more stupendous and lofty than those of Huahine, and in some parts equally broken and picturesque. The northern and western sides are singularly romantic; several pyramidal and conical mountains rising above the elevated and broken range, that stretches along in a direction nearly parallel with the coast, and from one to three miles distant from the beach. Though the shore is generally a gradual and waving ascent from the water's edge to the mountain, it is frequently rocky and broken. At Mahapoto, about half way between Opoa, the site of their principal temple, the ancient residence of the reigning family, and Utumaoro at the north-east angle of the island, there is a deep indentation in the coast. The rocks rise nearly perpendicular in some places on both sides, and the smooth surface of the ocean extends a mile and a half, or two miles, towards the mountains. The shores of this sequestered bay are covered with sand, shells, and broken coral. At the openings of several of the little glens which surround it, the cottages of the natives are seen peeping through the luxuriant foliage of the pandanus, or the purau; while the cultivated plantations in various parts extend from the margin of the sea to the foot of the mountains. The rivers that roll along their rocky courses from the head of the ravines to the ocean below—and the distant mountains, that rise in the interior—combine to form, though on a limited scale, the most rich, romantic, and

[page] 7

beautiful landscapes. The islands in general are well supplied with water. The mountains are sufficiently elevated to intercept the clouds that are wafted by the trade-winds over the surface of the Pacific; being clothed with verdure to their very summits, while they attract the moisture, they also prevent its evaporation. Most of the rivers or streams rise in the mountainous parts, and though, from the peculiar structure of these parts, and the circumscribed extent of the islands, the distance from their source to their union with the sea is comparatively short; yet the body of water is often considerable, and the uneven ground through which they have cut their way, the rocky projections that frequently divide the streams, and the falls that occur between the interior and the shore, cause the rivers to impart a charming freshness, vivacity, and splendour to the surrounding scenery.

Next to Tahiti, Raiatea perhaps is better supplied with rivers, or streams of excellent water, than any other island of the group. Its lowland is extensive, and the valleys, capable of the highest cultivation, are not only spacious, but conveniently situated for affording to the inhabitants intercourse with other parts of the island. On the north-west is a small but very secure harbour, called Hamaniino. Most of the ships formerly visiting Raiatea anchored in this by no means capacious, but convenient and sequestered, harbour. Such vessels usually entered the reefs that surround the two islands, either at the opening called Teavapiti, a little to the southward of Utumaora, or at that denominated Tomahahotu opposite the south end of the island of

[page] 8

Tahaa. They then proceeded within the reefs along the channel between the islands, to the harbour.

Water and wood were at all times procured with facility from the adjacent shore; and supplies of stock, poultry, and vegetables might generally be obtained by barter with the inhabitants. The mountains of the interior sheltered the bay from the strong eastern and southerly winds; and the wide opening in the reef, opposite the mouth of the valley forming the head of the bay, favoured the departure of vessels with the ordinary winds. A small and partially wooded island on the north side of the opening in the reefs opposite the harbour, distinctly points out the passage, and is very serviceable to ships going to sea. A few miles beyond the harbour of Hamaniino, Vaóaara is situated, which was the former Missionary station, the residence of the chiefs, and principal part of the population. There are two open bays on the east side of the island, Opoa and Utumaoro. They were occasionally visited by shipping; and the latter has, since the removal of the Missionary station, become the general place of anchorage. But although they are secured from heavy waves by the reefs of coral that stretch along the eastern shore, they are exposed to the prevailing winds, excepting so far as they are sheltered by the islands at the entrance from the sea.

There are no lakes in Raiatea or Tahaa, but both islands are encircled in one reef which is in some parts attached to their shores, and in others rises to the water's edge, at the distance of two or three miles from it. The water within the reefs, is as smooth as the surface of a lake in a gentleman's

[page] 9

pleasure-ground, though often from eighteen to thirty fathoms deep. The coral reefs from natural and beautiful breakwaters, preserving the lowland and the yielding soil of the adjacent shore from the force and encroachment of the heavy billows of the ocean. Numbers of singular and verdant little islands are remarkably useful, as they are most frequently found at those points where the openings into the harbours are formed. They are, therefore, excellent sea-marks, and furnish convenient temporary residences for the fishermen, who resort to them during the season for taking the operu, scomber scomber of Linneus, and other fish, periodically visiting their shores. Here they dry and repair their nets while watching the approach of the shoals, and find them remarkably advantageous in prosecuting the most important of their fisheries.

The sun had nearly set when we reached the settlement. As we approached the shore, crowds of the natives, who has recognized some of our party, came off to meet us, wading into the sea above their waist, in order to welcome out arrival. While gazing on the motley group that surrounded our boat, or thronged the adjacent shore, and exchanging our salutations with those nearest us, before we were aware of their design, upwards of twenty stout men actually lifted our boat out of the water, and raised it on their shoulders, carrying us, thus elevated in the air, amid the shouts of the bearers, and the acclamations of the multitude on the shore, first to the beach, and then to the large court-yard in front of the king's house, where, after experiencing no small apprehension from this unusual mode

II. C

[page] 10

of conveyance, we were set down safe and dry upon the pavement. Here we experienced a very hearty welcome from the chiefs and people. Their salutations were cordial, though unaccompanied by the ceremonies that were formerly regarded as indispensable. Considering the islanders as an uncivilized people, they seem to have been the most ceremonious of any with whom we are acquainted. This peculiarity appears to have accompanied them to the temples, to have distinguished the homage and the service they rendered to their gods, to have marked their affairs of state, and the carriage of the people towards their rulers, to have pervaded the whole of their social intercourse, to have been mingled with their most ordinary avocations, and even their rude and diversified amusements. Their salutations were often exceedingly ceremonious. When a chieftain from another island, or from any distant part, arrived, he seldom proceeded at once to the shore, but usually landed, in the first instance, on some of the small islands near. The king often attended in person, to welcome his guest, or, if unable to do this himself, sent one of his principal chiefs.

When the canoes of the visitor approached the shore, the chiefs assembled on the beach. Long orations were pronounced by both parties before the guests stepped on the soil: as soon as they were landed, a kind of circle was formed by the people; the king or chiefs on the one side, and the strangers on the other; the latter brought their marotai, or offering, to the king and the gods, and accompanied its presentation with an address, expressive of the

[page] 11

friendship existing between them: the priest, or orators of the king, then brought the presents, or manufaiti, bird of recognition. Two young plantain-trees were first presented, one for te atua, the god; the other for te hoa, the friend. A plantain-tree and a pig were brought for the king, a similar offering for the god; this was followed by a plantain and a pig, for the toe moe, the sleeping hatchet. A plantain-tree and a bough were then brought for the taura, the cord or bond of union, and then a plantain and a pig for the friend.

In some of their ceremonies, a plantain-tree was substituted for a man, and in the first plantain-trees offered in this ceremony to the god and the friend, they might perhaps be so regarded. Considerable ceremony attended the reception of a company of Areois. When they approached a village or district, the inhabitants came out of their doors, and, greeting them, shouted Manava, Manava, long before they reached the place. They usually answered, Teie "Here," and so proceeded to the rendezvous appointed, where the marotai was presented to the king, and a similar offering to the god.

Our mode of saluting by merely shaking hands, they consider remarkably cold and formal. They usually fell upon each others necks, and tauahi, or embraced each other, and saluted by touching or rubbing noses. This appears to be the common mode of welcoming a friend, practiced by all the inhabitants of the Pacific. It also prevails among the natives of Madagascar. During my visit to New Zealand, I was several times greeted in this manner by chiefs, whose tataued countenances, and ferocious appearance, were but little

[page] 12

adapted to cherish any predisposition to so close a contact. This method of saluting is called by the New Zealanders Ho-gni, Honi by the Sandwich Islanders, and Hoi by the Tahitians. In connexion with this, the custom of cutting themselves with sharks' teeth, and indulging in loud wailing, was a very singular method of receiving a friend, or testifying gladness at his arrival; it was, however, very general when the Europeans first arrived.

In the court-yard of the king we were met by our friends Messrs. Williams and Threlkeld, who, considering the short time they had been among the people, had been the means of producing an astonishing change, not only in their habits and appearance, but even in the natural face of the district. A carpenter's shop had been erected, the forge was daily worked by the natives, neat cottages were rising in several directions, and a large place of worship was building. The wilderness around was cleared to a considerable extent; the inhabitants of other parts were repairing to Vaóaara, and erecting their habitations, that they might enjoy the advantage of instruction. A flourishing school was in daily operation, and a large and attentive congregation met for public worship in the native chapel every Sabbath-day. In the society of our friends we spent a fortnight very pleasantly, and having adjusted our public arrangements, returned to Huahine, in the Haweis, in which Messrs. Barff, Williams, and myself, proceeded to Tahiti.

The island of Raiatea is not only the most important in the leeward group, from its central situa-

[page] 13

tion and its geographical extent, but on account of its identity, in tradition, with the origin of the people, and their preservation in the general deluge. It has been celebrated as the cradle of their mythology, the seat of their oracle, and the abode of those priests whose predictions for many generations regulated the expectations of the nation. It is also intimately connected with the most important matters in the traditionary history and ancient religion of the people.

The inhabitants of the Georgian, Society, and adjacent isles, comprehended, according to the ideas they entertained prior to the arrival of foreign vessels, the whole of the human race. In the island of Raiatea, their traditions informed them, their species originated, and hither after death they repaired. In connexion with my first voyages to the spot, which many have been accustomed to consider as the birth-place of mankind, and the region to which their disembodied spirits were supposed to resort, it may be proper to introduce the facts and observations, in reference to their origin, physical, intellectual, and moral character, which have resulted from subsequent visits to the island, and more extensive acquaintance with the people.

The inhabitants of the South Sea Islands are generally above the middle stature; but their limbs are less muscular and firm than those of the Sandwich Islanders, whom in many respects they resemble. They are, at the same time, more robust than the Marquesans, who are the most light and agile of the inhabitants of Eastern Polynesia. In size and physical power they are inferior to the New Zea-

[page] 14

landers, and probably resemble in person the Friendly Islanders, as much as any others in the Pacific; exhibiting, however, neither the gravity of the latter, nor the vivacity of the Marquesans. Their limbs are well formed, and although where corpulency prevails there is a degree of sluggishness in their actions, they are generally active in their movements, graceful and stately in their gait, and perfectly unembarrassed in their address. Those who reside in the interior, or frequently visit the mountainous parts of the islands, form an exception to this remark. The constant use of the naked feet in climbing the steep sides of the rocks, or the narrow defiles of the ravines, probably induces them to turn their toes inwards, which renders their gait exceedingly awkward.

Among the many models of perfection in the human figure that appear in the islands, (presenting to the eye of the stranger all that is beautiful in symmetry and graceful in action,) instances of deformity are now frequently seen, arising from a loathsome disease, of foreign origin, affecting the features of the face, and muscular parts of the body. There is another disease, which forms such a curvature of the upper part of the spine, as to produce what is termed a humped or broken back. The disease which produces this distortion of shape, and deformity of appearance, is declared by the natives, to have been unknown to their ancestors; and, according to the accounts some of them give it, was the result of a disease, left by the crew of Vancouver's ship. It does not prevail in any of the other islands; and although such numbers are now affected with it,

[page] 15

there is reason to believe, that, except the many disfigurements produced by the elephantiasis, which appears to have prevailed from their earliest antiquity, a deformed person was seldom seen.

The countenance of the South Sea Islander is open and prepossessing, though the features are bold, and sometimes prominent. The facial angle is frequently as perpendicular as in the European structure, excepting where the frontal and the occipital bones of the skull were pressed together in infancy. This was frequently done by the mothers, with the male children, when they were designed for warriors. The forehead is sometimes low, but frequently high and finely formed; the eye-brows are dark and well defined, occasionally arched, but more generally straight; the eyes seldom large, but bright and full, and of a jet black colour; the cheek-bones by no means high; the nose either rectilinear or aquiline, often accompanied with a fulness about the nostrils; it is seldom flat, notwithstanding it was formerly the practice of the mothers and nurses to press the nostrils of the female children, a flat and broad nose being by many regarded as more ornamental than otherwise. The mouth in general is well formed, though the lips are sometimes large, yet never so much so as to resemble those of the African. The teeth are always entire, excepting in extreme old age, and, though rather large in some, are remarkably white, and seldom either discoloured or decayed. The ears are large, and the chin retreating or projecting, most generally inclining to the latter. The form of the face is either round or oval, and but very seldom exhibits any resemblance to the angular form of the Tartar visage, while their

[page] 16

profile frequently bears a most striking resemblance to that of the European countenance. Their hair is of a shining black or dark brown colour; straight, but not lank and wiry like that of the American Indian, nor, excepting in a few solitary instances, woolly like the New Guinea or New Holland negroes. Frequently it is soft and curly, though seldom so fine as that of the civilized nations inhabiting the temperate zones.

There is a considerable difference between the stature of the male and female sex here, as well as in other parts of the world, yet not so great as that which often prevails in Europe. The females, though generally more delicate in form and smaller in size than the men, are, taken altogether, stronger and larger than the females of England, and are sometimes remarkably tall and stout. A roundness and fulness of figure, without extending to corpulency, distinguishes the people in general, particularly the females.

It is a singular fact in the physiology of the inhabitants of this part of the world, that the chiefs, and persons of hereditary rank and influence in the islands, are, almost without exception, as much superior to the peasantry or common people, in stateliness, dignified deportment, and physical strength, as they are in rank and circumstances; although they are not elected to their station on account of their personal endowments, but derive their rank and elevation from their ancestry. This is the case with most of the groups of the Pacific, but peculiarly so in Tahiti and the adjacent isles. The father of the late king was six feet four inches high; Pomare was six

[page] 17

feet two. The present king of Raiatea is equally tall. Mahine, the king of Huahine, but for the effects of age, would appear little inferior. Their limbs are generally well formed, and the whole figure proportioned to their height; which renders the difference between the rulers and their subjects so striking, that some have supposed they were a distinct race, the descendants of a superior people, who at a remote period had conquered the aborigines, and perpetuated their supremacy. It does not, however, appear necessary, in accounting for the fact, to resort to such a supposition; different treatment in infancy, superior food, and distinct habits of life, are quite sufficient.

The prevailing colour of the natives in an olive, a bronze, or a reddish brown—equally removed from the jet-black of the African and the Asiatic, the yellow of the Malay, and the red or copper-colour of the aboriginal American, frequently presenting a kind of medium between the two latter colours. Considerable variety, nevertheless, prevails in the complexion of the population of the same island, and as great a diversity among the inhabitants of different islands. The natives of the Paliser or Pearl Islands, a short distance to the eastward of Tahiti, are darker than the inhabitants of the Georgian group. It is not, however, a blacker hue that their skin presents, but a darker red or brown. The natives of Maniaa, or Mangeea, one of the Harvey cluster, and some of the inhabitants of Rurutu, and the neighbourhood to the south of Tahiti, designated by Malte Brun, "the Austral Islands," and the majority of the reigning family in Raiatea, are not darker than the inhabitants of some parts of southern Europe.

II. D

[page] 18

At the time of their birth, the complexion of Tahitian infants is but little if any darker than that of European children, and the skin only assumes the bronze or brown hue as they grow up under repeated or constant exposure to the sun. Those parts of the body that are most covered, even with their loose draperies of native cloth, are, through every period of life, much lighter coloured than those that are exposed; and, notwithstanding the dark tint with which the climate appears to dye their skin, the ruddy bloom of health and vigour, or the sudden blush, is often seen mantling the youthful countenance under the light brown tinge, which, like a thin veil, but partially conceals its glowing hue. The females who are much employed in beating cloth, making mats, or other occupations followed under shelter, are usually fairer than the rest; while the fisherman, who are most exposed to the sun, are invariably the darkest portion of the population.

Darkness of colour was generally considered an indication of strength; and fairness of complexion, the contrary. Hence, the men were not solicitous either to cover their persons, or avoid the sun's rays, from any apprehension of the effect it would produce on the skin. When they searched the field of battle for the bones of the slain, to use them in the manufacture of chisels, gimlets, or fish-hooks, they always selected those whose skins were dark, as they supposed their bones were strongest. When I have seen the natives looking at a very dark man, I have sometimes heard them say, "Taata ra e, te ereere! ivi maitai tona:" The man, how dark! good bones are his. A fair complexion was not an object of admiration of desire. They never

[page] 19

considered the fairest European countenance seen among them, handsomer than their own; and sometimes, when a fine, tall, well-formed, and personable man has landed from a ship, they have remarked as he passed along, "A fine man that, if he were but a native." They formerly supposed the white colour of the European's skin to be the effect to illness, and hence beheld it with pity. This opinion probably originated from the effects of a disease with which they are occasionally afflicted—a kind of leprosy, which turns the skin of the parts affected, white. This impression, however, is now most probably removed by the lengthened intercourse they have had with foreigners, and the residence of European families among them.

The mental capacity of the Society Islanders has been hitherto much more partially developed than their physical character. They are remarkably curious and inquisitive, and, compared with other Polynesian nations, may be said to possess considerable ingenuity, together with mechanical invention and imitation. Totally unacquainted with the use of letters, their minds could not be improved by any regular or continued culture; yet the distinguishing features of their civil polity—the imposing nature, the numerous observances, and diversified ramifications of their mythology—the legends of their gods—the historical songs of their bards—the beautiful, figurative, and impassioned eloquence sometimes displayed in their national assemblies—and, above all, the copiousness, variety, precision, and purity of their language, with their extensive use of numbers—warrant the conclusion, that they possess no contemptible mental capabilities.

[page] 20

This conclusion has been abundantly confirmed since the establishment of schools, and the introduction of letters. Not only have the children and young persons learned to read, write, cipher, and commit their lessons to memory with a facility and quickness not exceeded by individuals of the same age in any civilized country; but the education of adults, and even persons advanced in years—which in England with every advantage is so difficult an undertaking, that nothing but the use of the best means and the most untiring application ever accomplished it—has been effected here with comparative ease. Multitudes, who were upwards of thirty or forty years of age when they commenced with the alphabet, have, in the course of twelve months, learned to read distinctly in the New Testament, large portions, and even whole books of which, some of them have in a short period committed to memory.

They acquired the first rules of arithmetic with equal facility, and have readily received the different kinds of instruction hitherto furnished, as fast as their teachers could prepare lessons in the native language. It is probable that not less than ten thousand persons have learned to read the sacred Scriptures, and that nearly an equal number are either capable of writing, or are under instruction. In the several stations and branch stations, many thousands are still receiving daily instruction in the first principles of human knowledge and Divine truth.

The following extract from the journal of a Tahitian, now a native Missionary in the Sandwich group, is not only most interesting from the intelligence it conveys, but creditable to the writer's talents. It was published

[page] 21

in the American Missionary Herald, and refers to the young princess of the Sandwich Islands, the only sister of the late and present king.

"Nahienaena, in knowledge and words, is a women of matured understanding. All the fathers and mothers of this land are ignorant and left-handed; they become children in the presence of Nahienaena, and she is their mother and teacher. Her own men, women, and children, those composing her household (or domestic establishment,) listen to the good word of God from her lips. She also instructs Hoapiri and wife in good things. She teaches them night and day. She is constantly speaking to her steward, and to all her household. Very numerous are the words which she speaks, to encourage, and to strengthen them in the good way.

The young princess has always been pleasant in conversation. Her words are good words. She takes pleasure is conversation, like a woman of mature years. She orders her speech with great wisdom and discretion, always making a just distinction between good and evil. She manifests much discernment in speaking to others the word of God, and the word of love. It was by the maliciousness of the people, old and young, that she was formerly led astray. She was then ignorant of the devices of the wicked. They have given her no rest; but have presented every argument before her that this world could present, to win her over to them.

Nahienaena desires now to make herself very low. She does not wish to be exalted by men. She desires to cast off entirely the rehearsing of names; for her rejoicing is not now in names and titles. This is what she desires, and longs to have rehearsed—'Jesus alone; let him be lifted up; let him be exalted; let all rejoice in him; let our hearts sing praise to him.' This is the language of her inmost soul."

On a public occasion, in the island of Raiatea, during the year 1825, a number of the inhabitants were conversing on the wisdom of God; which, it was observed, though so long unperceived by them, was strikingly exhibited in every object they beheld. In confirmation of this, a venerable and gray-headed man, who had formerly been a sorcerer, or priest of the evil spirit,

[page] 22

stretched forth his hand, and looking at the limbs of his body, said, "Here the wisdom of God is displayed. I have hinges from my toes to my finger-ends. This finger has its hinges, and bends at my desire—this arm, on its hinge, is extended at my will—by means of these hinges, my legs bear me where I wish; and my mouth, by its hinge, masticates my food. Does not all this display the wisdom of God?"

The above will shew, more clearly than any declaration I can make, that the inhabitants of these distant isles, though shut out for ages from intercourse with every other part of the world, and deprived of every channel of knowledge, are, notwithstanding, by no means inferior in intellect or capacity to the more favoured inhabitants of other parts of the globe. These statements also warrant the anticipation that they will attain an elevation equal to that of the most cultivated and enlarged intellect, whenever they shall secure the requisite advantages.

They certainly appear to possess an aptness for learning, and a quickness in pursuit of it, which is highly encouraging, although in some degree counteracted by the volatile disposition, and fugitive habits, of their early life, under the influence of which their mental character was formed.

The moral character of the South Sea Islanders, though more fully developed than their intellectual capacity, often presents the most striking contradictions. Their hospitality has, ever since their discovery, been proverbial, and cannot be exceeded. It is practised alike by all ranks, and is regulated only by the means of the individual by whom it is exercised. A poor man feels himself called upon, when a friend from a distance visits

[page] 23

his dwelling, to provide an entertainment for him, though he should thereby expend every article of food he possessed; and would generally divide his fish or his bread-fruit with any one, even a stranger, who should be in need, or who should ask him for it.

I am willing to afford them every possible degree of credit for the exercise of this truly amiable disposition; yet, when it is considered that a guest is not entertained day after day at his friend's table, but that after one large collection of food has been presented, the visitor must provide for himself, while the host frequently takes but little further concern about him—we are induced to think that the force of custom is as powerful in its influence on his mind, as that of hospitality. In connexion with this, it should be recollected, that for every such entertainment, the individual expects to be reimbursed in kind, whenever he may visit the abode of this guest. Their ancient laws of government, also, imperiously required the poor industrious landholder, or farmer, to bring forth the produce of this garden or his field for the use of the chiefs, or the wandering and licentious Areois, whenever they might halt at his residence; and more individuals have been banished, or selected as sacrifices, for withholding what these daring ramblers required, than perhaps for all other crimes. To withhold food from the king or chiefs, when they might enter a district, was considered a crime next to resisting the royal authority, or declaring war against the king; and this has in a great degree rendered the people so ready to provide an entertainment for those by whom they may be visited.

Next to their hospitality, their cheerfulness and

[page] 24

good nature strikes a stranger. They are seldom melancholy or reserved, always willing to enter into conversation, and ready to be pleased, and to attempt to please their associates. They are, generally speaking, careful not to give offence to each other: but though, since the introduction of Christianity, families dwell together, and find an increasing interest in social intercourse, yet they do not realize that high satisfaction experienced by members of families more advanced in civilization. There are, however, few domestic broils; and were fifty natives taken promiscuously from any town or village, to be placed in a neighbourhood or house—where they would disagree once, fifty Englishmen, selected in the same way, and placed under similar circumstances, would quarrel perhaps twenty times. They do not appear to delight in provoking one another, but are far more accustomed to jesting, mirth, and humour, than irritating or reproachful language.

Their jests and raillery were not always confined to individuals, but extended to neighbourhoods, or the population of whole islands. The inhabitants of one of the Leeward Islands, Tahaa, I believe, even to the present time furnish matter for mirthful jest to the natives of the other islands of the group, from the circumstance of one of their people, the first time she saw a foreigner who wore boots, exclaiming, with astonishment, that the individual had iron legs. It is also said, that among the first scissors possessed by the Huahineans, one pair became exceedingly dull, and the simple-hearted people, not knowing how to remedy this defect, tried several experiments, and at length baked the scissors in a native oven, for the purpose of sharpen-

[page] 25

ing them. Hence the people of Huahine are often spoken of in jest by the Tahitians, as the feia eu paoti, or people that baked the scissors. The Tahitians themselves were in their turn subjects of raillery, from some of their number who resided at a distance from the sea, attempting, on one occasion, to kill a turtle by pinching its throat, or strangling it, when the neck was drawn into the shell, on which they were surprised to find they could make no impression with their fingers. The Huahineans, therefore, in their turn, spoke of the Tahitians as the feia uumi honu, the people that strangled the turtle.

Their humour and their jests were, however, but rarely what might be termed innocent sallies of wit, and were in general low and immoral to a disgusting degree. Their common conversation, when engaged in their ordinary avocations, was often such as the ear could not listen to without pollution, presenting images, and conveying sentiments, whose most fleeting passage through the mind left contamination. Awfully dark, indeed, was their moral character, and notwithstanding the apparent mildness of their disposition, and the cheerful vivacity of their conversation, no portion of the human race was ever perhaps sunk lower in brutal licentiousness and moral degradation, than this isolated people. The veil of oblivion must be spread over this part of their character, of which the appalling picture, drawn by the pen of inspiration in the hand of the apostle, in the first chapter of the epistle to the Romans, revolting and humiliating as it is, affords but too faithful a portraiture.

The depraved moral habits of the South Sea Islanders undoubtedly weaken their mental energies, and enervate

II. E

[page] 26

their physical powers; and although remarkably strong men are now and then met with among them, they seem to be more distinguished by activity, and capability of endurance, than muscular strength. They engage in some kinds of work with great spirit for a time, but they soon tire. Regular, steady habits of labour are only acquired by long practice. When a boat manned with English seamen, and a canoe with natives, have started together from the shore—at their first setting out, the natives would soon leave the boat behind, but, as they became weary, they would relax their vigour; while the seamen, pulling on steadily, would not only overtake them, but, if the voyage occupied three or four hours, would invariably reach their destination first.

The natives take a much larger quantity of refreshment than European labourers, but their food is less solid and nutritive. They have, however, the power of enduring fatigue and hunger in a greater degree than those by whom they are visited. A native will sometimes travel, in the course of a day, thirty or forty miles, frequently over mountain and ravine, without taking any refreshment, except the juice from a piece of sugarcane, and apparently experience but little inconvenience from his excursion. The facility with which they perform their journeys is undoubtedly the result of habit, as many are accustomed to traverse the mountains, and climb the rocky precipices, even from their childhood.

The longevity of the islanders does not appear to have been, in former times, inferior to that of the inhabitants of more temperate climates. It is, however, exceedingly difficult to ascertain the age of individuals in a com-

[page] 27

munity destitute of all records; and although many persons are to be met with, whose wrinkled skin, decrepit form, silver hair, impaired sight, toothless jaws, and tremulous voice, afford every indication of extreme age; these alone would be fallacious data, as climate, food, and habits of life might have prematurely induced them. Our inferences are therefore drawn from facts connected with comparatively recent events in their history, the dates of which are well known. When the Missionaries arrived in the Duff, there were natives on the island who could recollect the visit of Captain Wallis: he was there in 1767. There are, in both the Sandwich and Society Islands, individuals who can recollect Captain Cook's visit, which is fifty years ago; there are also two now in the islands, that were taken away in the Bounty, forty years since; and these individuals do not look more aged, nor even so far advanced in years, as others that may be seen. The opinion of those Missionaries who have been longest in the islands is, that many reach the age of seventy years, or upwards. There is, therefore, every reason to believe, that the period of human life, in the South Sea Islands, is not shorter than in other parts of the world, unless when it is rendered so by the inordinate use of ardent spirits, and the influence of diseases, prevailing among the lower classes, from which they were originally exempt, and the ravages of which they are unable to palliate or remove.

The mode of living, especially among the farmers, their simple diet, and the absence of all stimulants, their early hours of retiring to rest, and rising in the morning with or before the break of day, their freedom from irritating or distressing cares,

[page] 28

and sedentary habits, which so often, in artificial or civilized society, destroy health, appear favourable to the longevity of this portion of the inhabitants, and present a striking contrast to the dissipated and licentious habits of the Areois, the dancers, and similar classes.

It is impossible for any one who has visited these shores, or traversed any one of the districts, to entertain the slightest doubt that the number of inhabitants in the South Sea Islands was formerly much greater than at present. What their number, in any remote period of their history, may have been, it is not easy to ascertain: Captain Cook estimated those residing in Tahiti at 200,000. The grounds, however, on which he formed his conclusions were certainly fallacious. The population was at all times so fugitive and uncertain, as to the proportion it bore to any section of geographical surface, that no correct inference, as to the amount of the whole, could be drawn from the numbers seen in one part. Captain Wilson's calculation, in 1797, made the population of Tahiti only about 16,000; and, not many years afterwards, the Missionaries declared it as their opinion, that this island did not contain more than 8000 souls; and I cannot think that, within the last thirty years, it has ever contained fewer inhabitants.

The present number of natives is about 10,000. That of Eimeo and Tetuaroa probably 2,000. The Leeward Islands perhaps contain nearly an equal number. The Austral Islands have about 5,000 inhabitants; 4,000 of whom reside in the islands of Rapa and Raivavai. Rarotogna, or Rarotoa, has a population of nearly 7,000; and the whole of the Harvey

[page] 29

Islands contain not less than ten or eleven thousand. Connected with these may be considered the Paumotu, or Pearl Islands, of whose population it is difficult to form any correct estimate, as there are no means of ascertaining their numbers, excepting from the reports of the natives, and the observations of masters of vessels, who generally make a very short stay among them. Anaa, or Prince of Wales's Island, is said to be inhabited by several thousands, and as the islands are numerous, though small, it is to be presumed that their population does not amount to less than thousand. From these statements it will appear, that the population of the Georgian and Society Islands, together with the adjacent clusters, with which the natives maintain constant intercourse, and to which Christianity has been conveyed by native or European teachers, comprises between forty-eight and fifty thousand persons. In this number, the Marquesas, to which native teachers have gone, and which one of the Missionaries has recently visited, are not included. Their population is probably about thirty thousand.

With respect to the Society and neighbouring islands, although no ancient monuments are found indicating that they were ever inhabited by a race much further advanced in civilization than those found on their shores by Wallis, Cook, and Bougainville; yet that race has evidently, at no very remote period, been much more numerous than it was when discovered by Europeans. In the bottom of every valley, even to the recesses in the mountains, on the sides of the inferior hills, and on the brows of almost every promontory, in each of the islands, monuments

[page] 30

of former generations are still met with in great abundance. Stone pavements of their dwellings and court-yards, foundations of houses, and ruins of family temples, are numerous. Occasionally they are found in exposed situations, but generally amidst thickets of brushwood or groves of trees, some of which are of the largest growth. All these relics are of the same kind as those observed among the natives at the time of their discovery, evidently proving that they belong to the same race, though to a more populous æra of their history. The stone tools occasionally found near these vestiges of antiquity demonstrate the same lamentable fact.

The present generations are deeply sensible of the depopulation that has taken place, even within the recollection of those most advanced in years, and have felt acutely in prospect of the annihilation that appeared inevitable. Their priests formerly denounced the destruction of the nation, as the greatest punishment the gods could inflict, and the following was one of the predictions: E tupu te fau, e toro te farero, e mou te taata: "The fau (hisbiscus) shall grow, the farero (coral) shall spread or stretch out its branches, but man shall cease."—The fau is one of the most spreading trees, and is of quickest growth; it soon over-runs uncultivated lands; while the branching coral, farero, is perhaps more rapid in its formation than any of the corallines that close up the openings in the reefs, and, wherever it is shallow, rise to the water's surface, so as to prevent the passage of the canoe, and destroy the resort of the fish. This was denounced as the punishment that would follow disobedience to the

[page] 31

junctions or requisitions of the priest, delivered in the name, and under the authority, of the gods. Tati, however, remarked to Mr. Davies, that it was the observing, not the neglecting of the directions of the priest, that had nearly produced its actual accomplishment.

At the time when the nation renounced idolatry, the population was so much reduced, that many of the more observant natives thought the denunciation of the prophet was about to be literally fulfilled. Tati, the chief of Papara, talking with Mr. Davies on this subject, in 1815, said, with great emphasis, that "if God had not sent his word at the time he did, wars, infant-murder, human sacrifices, &c. would have made an end of the small remnant of the nation." A similar declaration was pathetically made by Pomare soon after, when some visitors from England waited upon him at his residence. He addressed them to the following effect: "You have come to see us under circumstances very different from those under which your countrymen formerly visited our ancestors. They came in the æra of men, when the islands were inhabited, but you are come to behold just the remnant of the people." I have often heard the chiefs speak of themselves and the natives as only a small toea, remainder, left after the extermination of Satani, or the evil spirit; comparing themselves to a firebrand unconsumed among the mouldering embers of a recent conflagration. These figures, and others equally affecting and impressive, were but too appropriate, as emblems of the actual state to which they were at that time reduced. Under the depopulating influence of vicious habits—the dreadful devastation of diseases that followed, and the early destruction of health—the prevalence

[page] 32

of infanticide—the frequency of war—the barbarous principles upon which it was prosecuted, and the increase of human sacrifices, it does not appear possible that they could have existed, as a nation, for many generations longer.

An inquiry naturally presents itself in connexion with this subject, viz—To what cause is this recent change in the circumstances of the people to be attributed? It is self-evident, that if these habits had always prevailed among the Tahitians, they must long since have been annihilated. Society must, at some time, have been more favourable, not only to the preservation, but to the increase of population, or the inhabitants could never have been so numerous as they undoubtedly were a century or a century and a half ago. There is no question but that depopulation had taken place to a considerable extent prior to their discovery by Captain Wallis, and it is not easy to discover the causes which first led to it. Infanticide and human sacrifices, together with their wars, appear to have occasioned the dimunition of the inhabitants before the period alluded to. Whether war was more frequent immediately preceding their discovery, than it had been in earlier ages, we have not the means of knowing, nor have we been able to ascertain, with any great accuracy, how long the Areoi society had existed, or child-murder was practised. There is reason to believe that infanticide is not of recent origin, and the antiquity of the Areoi fraternity, according to tradition, is equal to that of the first inhabitants.

Human sacrifices, we are informed by the natives, are comparatively of modern institution, and were not admitted until a few generations antecedent to the discovery of the islands. They were first offered at

[page] 33

Raiatea, in the national marae at Opoa, having been demanded by the priest in the name of the god, who had communicated the requisition to his servant in a dream. Human sacrifices were presented at Raiatea and the Leeward Islands for some time before they were introduced among the offerings to the deities of Tahiti; but soon after they began to be employed, they were offered with great frequency, and in appalling numbers: but of this, an account will hereafter be given.

The depopulation that has taken place during the last two or three generations, viz. since their discovery, may be easily accounted for. In addition to a disease, which, as a desolating scourge, spread, unpalliated and unrestrained, its unsightly and fatal influence among the people, two others are reported to have been carried thither—one by the crew of Vancouver in 1790; and the other by means of the Britannia, an English whaler, in 1807. Both these disorders spread through the islands; the former almost as fatal as the plague, the latter affecting nearly every individual throughout all the islands of the group. The maladies originally prevailing among them, appear, compared with those by which they are now afflicted, to have been few in number and mild in character.

Next to disease, the introduction of fire-arms, which, although their use in war has not perhaps rendered their engagements more cruel and murderous than when they fought hand to hand with club and spear—they have undoubtedly cherished, in those who possessed them, a desire for war, as a means of enlarging their territory, and augmenting their power. Pomare's dominion would never have been so extensive and so absolute, but for the aid he derived, in the early

II. F

[page] 34

part of his reign, from the mutineers of the Bounty, who attended him to battle with arms which they had previously learned to use with an effect, which his opponents could not resist. Subsequently, the hostile chieftains, having procured fire-arms, and succeeding in attaching to their interest European deserters from their ships, considered themselves, if not invincible, at least equal to their enemies, and sought every opportunity for engaging in the horrid work of accelerating the depopulation of their country. Destruction was the avowed design with which they commenced every war, and the principle of extermination rendered their hostilities so fatal to the vanquished party.

Another cause most influential in the diminution of the Tahitian race, has been the introduction of the art of distillation, and the extensive use of ardent spirits. They had, before they were visited by our ships, a kind of intoxicating beverage called ava, but the deleterious effects resulting from its use were confined to a comparatively small portion of the inhabitants. The growth of the plant from which it was procured was slow; its culture required care; it was usually tabued for the chiefs; and the common people were as strictly prohibited from appropriating it to their own use, as the peasantry are in reference to the game of England. Its effects also were rather sedative, than narcotic or inebriating.

But after the Tahitians had been taught by foreign seamen, and natives of the Sandwich Islands, to distil spirits from indigenous roots, and rum had been carried to the islands in abundance as an article of barter, intoxication became almost universal; and all the demoralization, crimes, and misery, that follow in its train, were added to the multiplied sorrows and wasting

[page] 35

scourges of the people. It nurtured indolence, and spread discord through their families, increased the abominations of the Areoi society, and the unnatural crime of infanticide. Before going to the temple to offer a human sacrifice to their gods, the priests have been known to intoxicate themselves, in order that they might be insensible to any unpleasant feelings this horrid work might excite.

These causes operating upon a people, whose simple habits of diet rendered their constitutions remarkably susceptible of violent impressions, are, to a reflecting mind, quite sufficient to account for the rapid depopulation of the islands within the last fifty or sixty years.

The philanthropist, however, will rejoice to know, that although sixteen years ago the nation appeared on the verge of extinction, it is now, under the renovating and genial principles of true religion, and the morality with which this is inseparably connected, rapidly increasing. When the people in general embraced Christianity, we recommended that a correct account of the births and deaths occurring in each of the islands should be kept. From the operation of the causes above enumerated, for some years even after the crimes in which they originated had ceased, the number of deaths exceeded that of births. About the years 1819 and 1820, they were nearly equal, and since that period population has been rapidly increasing.

It was not till the account of deaths and births was presented, that we had an adequate idea of the affecting depopulation that had been going on; and if, for several years after infanticide, inebriation, human sacrifices, and war, were discontinued, the number of deaths exceeded that of the births; how appalling must that

[page] 36

excess have been, when all these destructive causes were in full operation! There is now, however, every ground to indulge the expectation that the population will become greater than it has been in any former period of their history; and it is satisfactory, in connexion with this anticipation, to know—that extent of soil capable of cultivation, and other rescourses, are adequate to the maintenance of a population tenfold increased above its present numbers.

[page] 37

CHAP. II.

Origin of this inhabitants of the South Sea Islands—Traditions—Legend of Taaoroa and Hina—Resemblance to Jewish history—Coincidences in language, mythology, &c. with the language, &c. of the Hindoos and Malays, Madagasse, and South Americans—Difficulty of reaching the islands from the west—Account of different native voyages—Geographical extent over which the Polynesian race and language prevail—Account of the introduction of animals—Predictions of their ancient prophets relating to the arrival of ships—Traditions of the deluge, corresponding with the accounts in sacred and profane writings.

THE origin of the inhabitants of the South Sea Islands, in common with other parts of Polynesia, is a subject perhaps of more interest and curiosity, than of importance and practical utility. The vast extent of geographical surface covered by the race of which they form an integral portion, the analogy in character, the identity in language, &c., the remote distance at which the different tribes are placed from each other, and the isolated spots and solitary clusters which they occupy in the vast expanse of surrounding water, render the source whence they were derived, one of the mysteries connected with the history of our species.

To a Missionary, the business of whose life is with the people among whom he is stationed, every thing relating to their history is, at least, interesting; and the origin of the islanders has often engaged our attention, and formed the subject of our inquiries. The early history of a people destitute of all records, and

[page] 38

remote from nations in whose annals contemporaneous events would be preserved, is necessarily involved in obscurity. The greater part of the traditions of this people are adapted to perplex rather than facilitate the investigation.

A very generally received Tahitian tradition is, that the first human pair were made by Taaroa, the principal deity formerly acknowledged by the nation. On more than one occasion, I have listened to the details of the people respecting his work of creation. They say, that after Taaroa had formed the world, he created man out of araea, red earth, which was also the food of man until bread-fruit was made. In connexion with this, some relate that Taaroa one day called for the man by name. When he came, he caused him to fall asleep, and that, while he slept, he took out one of his ivi, or bones, and with it made a woman, whom he gave to the man as his wife, and that they became the progenitors of mankind. This always appeared to me a mere recital of the Mosaic account of creation, which they had heard from some European, and I never placed any reliance on it, although they have repeatedly told me it was a tradition among them before any foreigner arrived. Some have also stated that the woman's name was Ivi, which would be by them pronounced as if written Eve. Ivi is an aboriginal word, and not only signifies a bone, but also a widow, and a victim slain in war. Notwithstanding the assertion of the natives, I am disposed to think that Ivi, or Eve, is the only aboriginal part of the story, as far as it respects the mother of the human race. Should more careful and minute inquiry confirm the truth of their declaration, and prove that this account was in existence among

[page] 39

them prior to their intercourse with Europeans, it will be the most remarkable and valuable oral tradition of the origin of the human race yet known.