[page i]

NARRATIVE

OF A VOYAGE TO THE

SOUTHERN ATLANTIC OCEAN,

IN THE YEARS 1828, 29, 30,

PERFORMED IN H. M. SLOOP CHANTICLEER,

UNDER THE COMMAND OF THE LATE

CAPTAIN HENRY FOSTER, F.R.S. &c.

BY ORDER OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF THE ADMIRALTY.

FROM THE PRIVATE JOURNAL OF

W. H. B. WEBSTER,

SURGEON OF THE SLOOP.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to His Majesty.

1834.

[page ii]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Dorset Street, Fleet Street.

[page iii]

PREFACE.

THE peculiar objects of the Chanticleer's Voyage rendered it one of more than ordinary interest, and particularly desirable that a record of its general proceedings should be preserved. Had it not been for the melancholy event by which the expedition was deprived of its leader, there can be no doubt that a complete narrative of the voyage would long ago have been published. The present volumes have been drawn up from notes made with a scrupulous care.

The numerous observations resulting from the extraordinary exertions of Captain Foster, were placed by the Admiralty in the hands of men of science, who have done ample justice to

[page] iv

the merits of their Author: some of them have been given here, but their discussion, and the conclusions of these gentlemen, will be found in the transactions of the learned Societies to which they belong.

Besides this public testimony to the merits and high qualifications of Captain Foster, his admiring friends have erected a Monument to his memory in the sanctuary of his native village, Woodplumpton in Lancashire.

The monument consists of an Urn, from which the British flag hangs in negligent folds, and against which a sailor is leaning in the attitude of grief. An anchor and quadrant, and a few nautical and scientific instruments, are also introduced; and below the figure the following inscription is engraved in plain Roman capitals:

Sacred to the Memory of

HENRY FOSTER, R. N. F. R. S.

Distinguished as well for superiority of intellect

as urbanity of manners.

By a zealous and firm discharge of duty,

he gained the confidence and regard of his

brother officers, and by a successful

pursuit of knowledge attracted the

notice of men of science.

[page v]

For his philosophical experiments made in the

Arctic regions, the Copley medal of the

Royal Society

was presented to him on the 30th November,

1827; when the Lord High Admiral of

England, with an alacrity honourable

to himself and to the subject of his patronage,

instantly promoted him to the rank of

Commander.

In the year following he sailed on a

voyage of scientific research.

He had completed his astronomical observations

at Panama, and all things had prospered

in his hand; when, proceeding to his ship,

and anticipating a speedy return to his

native shore, he fell from a canoe, and

in a moment was lost to his country

and his friends.

His body, shrouded in the British flag, was

interred near to the fatal spot on the bank of

the river Chagres, in the Gulf of Mexico,

on the 5th of Feb. 1831, and in the 34th year

of his age.

This monument was erected by several

of his companions and friends, as a

memorial of the high esteem they

entertained for his character, and of the deep

regret they felt for his untimely death.

He was the son of the Rev. Henry Foster,

Incumbent of this Chapelry.

VOL. I. b

[page break]

[page vii]

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

CHAPTER I.

| Appointed Surgeon of the Chanticleer.—Objects of the Voyage.—Commander Foster.—Equipments.—Frazer's Stove.—Departure from Spithead.—The Eddystone Lighthouse.—Detained at Falmouth.—Final Departure.—Madeira.—Teneriffe.—Fry of the Whale.—St. Antonio.—Dolphins in chase.—Various kinds of Produce.—Sucking Fish.—Calms.—Touch at Fernando Noronha.—Abrolhos.—A suspicious Sail.—Arrive at Rio Janeiro. | Page 1 |

CHAPTER II.

| Some Account of Rio Janeiro. | 36 |

CHAPTER III.

| Continuation of the Voyage.—The Island of St. Catherine.—Produce.—People.—Peculiar quality of the Ferns.—Arrival at Monte Video.—Change of Temperature.—River La Plata.—Prepare for Pendulum Operations on Rat Island.—Military Operations going forward.—State of the Fortress.—Lieutenant Williams's Adventure.—An awkward position.—The Garrison in confusion.—A false alarm.—Excursion to a Quinta. | 54 |

[page] viii

CHAPTER IV.

| The town of Monte Video.—Miradors.—Cathedral.—Public Buildings.—Market.—Country Carts.—Gauchos.—Females of Monte Video.—Sheep for Fuel.—Cruel mode of putting Prisoners to death.—Spirit of Gambling.—Imports and Exports.—Climate.—Pamperos.—Native Birds.—A Culprit executed. | 73 |

CHAPTER V.

| Depart for the Southward.—Make Staten Island.—Bad weather.—Excellence of Frazer's Stove.—Anchor off Cape St. John.—Meet an American Sealer.—Moored in North Port Hatchett.—Staten Island.—Description of the Island.—Account of the Seal.—Various kinds, their nature and habits.—Penguins.—Albatross.—Scarcity of Fish.—Teredo Naval is.—Remarkable Medusæ.—Reflections.—Climate.—Prevailing Winds.—Harbours of the Island. | 94 |

CHAPTER VI.

| Departure from Staten Island.—Arrive at Wigwam Cove, Cape Horn.—Depart for New South Shetland.—First Iceberg seen.—Make Smith's Island.—Dirk Gherritz Land.—Whales.—Clarence Land.—Red Snow.—Beauties of an Iceberg.—Deceptive distance.—Proportion of the immersed part of Icebergs.—Their formation. | 132 |

CHAPTER VII.

| Deception Island.—The Chanticleer moored.—Comparison of Scenery.—Formation of the Island.—Hot Springs.—Jack's comparisons.—Birds of Deception Island.—Climate.—Its preserving nature.—Aurora Australis. | 144 |

[page] ix

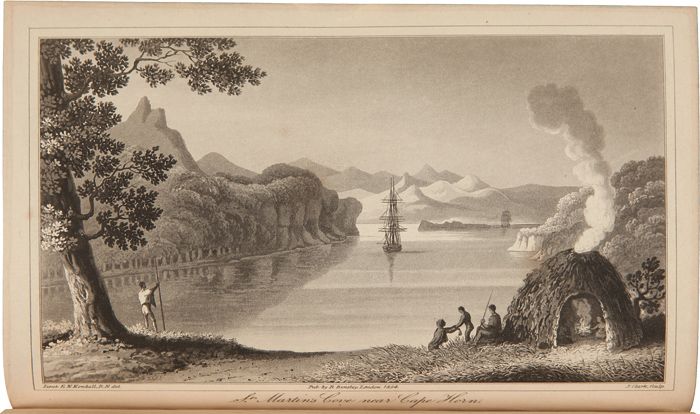

CHAPTER VIII.

| Difficulty of getting away from Deception Island.—Absence of Icebergs.—Passage to Cape Horn.—Anchor in St. Martin's Cove.—Fuegians.—Their feeble nature.—Fuegian Wigwam.—A bad Scholar.—Character of the Fuegian Indians.—Curious mode of catching Fish.—Canoes.—Deserted by the Fuegians.—Hermit Island. | 166 |

CHAPTER IX.

| Climate of Cape Horn.—Similar Parallels and dissimilar Temperatures.—Erroneous notions of Temperature.—Humming-birds in Snow Showers.—Equality of the Summer and Winter. | 189 |

CHAPTER X.

| Joined by his Majesty's Ship Adventure.—A Tribute to the memory of Cook.—Symptoms of Scurvy.—Donkin's Meat.—Depart from Cape Horn.—Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope.—Oceanic Companions.—Make the Land. | 205 |

CHAPTER XI.

| Bear up for Mossel Bay.—A Whaling Station.—Face of the Country.—Cape St. Blaize.—Sandstone Formations.—Car of Venus.—Oysters.—A Whale and her Cub.—Charcoal.—Formation of the Whale.—Whaling Seasons.—Cape Aloes.—Departure for Table Bay. | 216 |

CHAPTER XII.

| Moored in Table Bay.—Discovery of the Cape of Good Hope.—Cape Town.—The Heregracht, Churches, and Public Buildings.—Articles of Manufacture.—Amusements. |

[page] x

| —Inhabitants.—Boat and Horse Hire.—Public Library.—Carriages and their Drivers.—Cape Wines.—Management of the Vine.—The Observatory.—Capital Punishments.—Respect of the Malays to the Bishop of Calcutta.—Dutch Hospitality and Customs. | 232 |

CHAPTER XIII.

| A Trip into the Country.—Reception at a Farm-house.—Bees.—Garden.—The Kraal and its Keeper.—Cuds of Bones.—Cornucopiæ.—Sheep's Tails.—The Dormitory and its accompaniments.—Dutch mode of Living.—Crocuses.—A Hottentot Dance.—An Egg newly laid.—Sir John Truter.—Effects of Generosity.—An expected Feast.—Hottentots, their character and peculiar habits.—Poisoned Arrows.—Method of killing the Ostrich.—Comparative Anatomy.—Good works of Missionaries. | 263 |

CHAPTER XIV.

| Newlands and Country-seats.—Farms at the Cape.—Heights of Land.—Ascent of the Table Mountain.—View from the Summit.—Geological Formation.—Speculations concerning it.—Comparative Vegetation.—Beasts and Birds.—The Pelican's tricks.—Ostriches and Butcher-birds.—Snakes, their poison and method of invading nests.—The Chameleon.—Sun-fish.—Change in the colour of the Water.—Robben Island.—Simon's Town. | 290 |

CHAPTER XV.

| Seasons and Climate of the Cape.—Barometrical Pressure at the Cape and at Cape Horn compared.—Remarks on the Barometer.—Mirage.—Dew.—The Table-cloth.—Opinions of this phenomenon.—Meteors.—Temperature.—Emigrants.—Opinions of the Country. | 315 |

[page] xi

CHAPTER XVI.

| Departure from the Cape.—Land and Sea-breezes.—Appearance of St. Helena.—Anchor off James Town.—Discovery of the Island, and its first Possessors.—Relative Heights of its Peaks.—The Vale of Arno.—Some Account of James Town.—Roads of the Island.—Hailey Hill.—Diana's Peak.—Rating Chronometers. | 336 |

CHAPTER XVII.

| Napoleon's Grave.—Reflections.—Longwood.—Institutions at James Town.—Silk Establishment.—Potatoes.—Current Prices.—The China Fleet.—Absence of Lawyers.—Humid Climate.—Geology.—Cockroaches.—Sharks, their voraciousness.—Surfs. | 355 |

CHAPTER XVIII.

| Sail for Ascension in company with the Eden.—Anchor off George Town.—Character of the Island.—Establishment of George Town.—The Green Mountain and the Devil's Riding Ground.—Produce of the Island.—Dampier's Springs.—Turtle, their habits.—Method of taking them.—Male Turtle never obtained.—Insects. | 382 |

[page xii]

LIST OF MAPS AND PLATES.

VOLUME I.

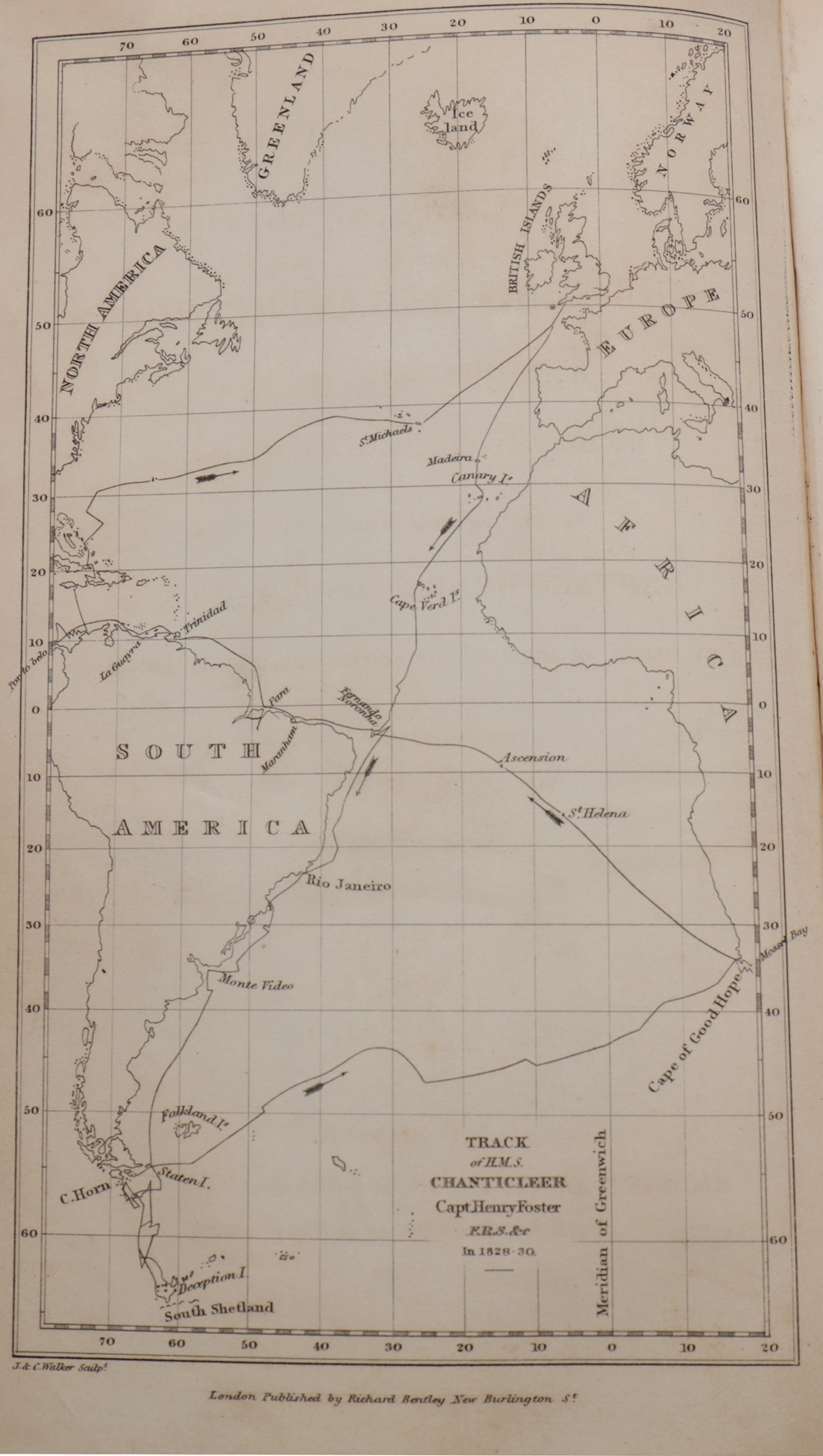

| Track of H. M. S. Chanticleer | To face Title-page. |

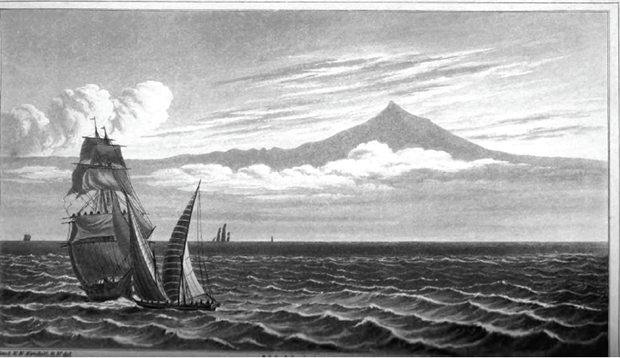

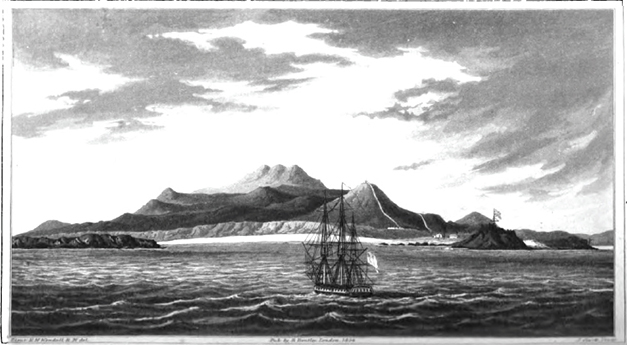

| Teneriffe, S. W. | 11 |

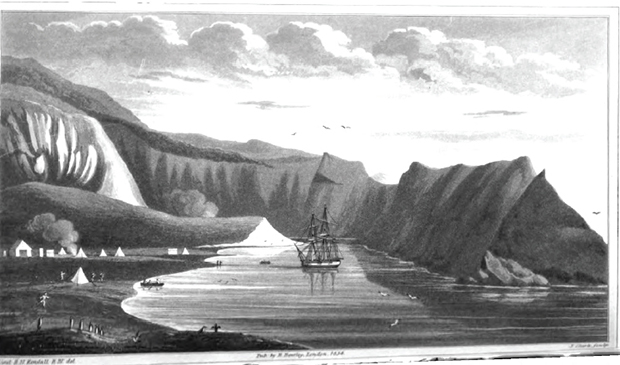

| Pendulum Station at Port Cook, Staten Island | 99 |

| Pendulum Cove, Deception Island, South Shetland | 147 |

| St. Martin's Cove, near Cape Horn | 177 |

| Ascension, Red Hill, S.E. by E. | 385 |

VOLUME II.

| The Isthmus of Darien | To face Title-page. |

[page 1]

VOYAGE

IN

HIS MAJESTY'S SLOOP

CHANTICLEER.

CHAPTER I.

Appointed Surgeon of the Chanticleer.—Objects of the Voyage.—Commander Foster.—Equipments.—Frazer's Stove.—Departure from Spithead.—The Eddystone Lighthouse.—Detained at Falmouth.—Final departure.—Madeira.—Teneriffe.—Fry of the whale.—St. Antonio.—Dolphins in chase.—Various kinds of produce.—Sucking Fish.—Calms.—Touch at Fernando Noronha.—Abrolhos.—A suspicious Sail.—Arrive at Rio Janeiro.

ON the 14th December 1827 my appointment of surgeon summoned me to repair on board His Majesty's sloop Chanticleer, commanded by Captain Henry Foster, F.R.S. Having reached Portsmouth on the 29th, I found the vessel preparing for a voyage, the principal object of which was to ascertain the true figure of the earth, by a series of pendulum experiments at various places in the northern and southern

VOL. I. B

[page] 2

hemispheres. This method of solving a problem which still occupies the attention of scientific men, depends on the force of gravity at different parts of the earth's surface in producing a greater or less number of vibrations of the pendulum in a certain space of time, which is found to vary according to the distance of the place of observation from the earth's centre. From these observations the radius of the earth is obtained in various northern and southern latitudes, from which its figure is inferred by calculation. Another object contemplated in the present voyage, and one of the first importance in navigation, was to measure accurately the meridian distances by means of chronometers between the various places visited by the Chanticleer. Several other inquiries, relating to meteorology, the currents of the ocean, magnetism, and the usual detail connected with navigation, were combined with the foregoing, and served to render the voyage highly interesting to men of science.

The valuable experiments made by Captain Foster in the polar regions, while serving as astronomer with Sir Edward Parry, had obtained him the Copley medal of the Royal

[page] 3

Society; and it was at the suggestion of the Council of this learned body that the present voyage was undertaken, and the care of it entrusted to Captain Foster by His Most Gracious Majesty, then Lord High Admiral.

In order to achieve the important objects above enumerated, which demanded a considerable range of scientific attainment, many instruments of the most expensive kind were supplied to Captain Foster. The ordinary mode of equipment was departed from at the dockyard in the internal arrangements of the vessel, and nothing was left undone which his experience, added to that of the first lieutenant, could suggest to render the Chanticleer in every respect fit to perform the extraordinary service on which she was about to be employed. By the express direction of His Royal Highness the Lord High Admiral, the same attention was paid to this as to the scientific department, and, when completed, the vessel presented a model which might justly be pointed out as a specimen of the skill and ingenuity of the age.

The Chanticleer was built in the year 1804, at the Isle of Wight, and was pierced for ten guns, her burthen being two hundred and

B 2

[page] 4

thirty-seven tons. For the present voyage two guns only were supplied, and she was rigged as a barque. The complement of the Chanticleer consisted of fifty-seven men, including fifteen officers and six marines.

The various equipments having been completed, and the instruments deposited on board, we left Portsmouth harbour on the 21st of April 1828, and on the following day the customary visit was paid to us by the Port Admiral, Sir Robert Stopford. This ceremony of visiting His Majesty's ships before they go to sea, and more particularly when preparing for a voyage like the present, forms an important part of the Port Admiral's duty. The object of it is to inspect the condition of the ship and her crew, the names of the latter being severally called over as they appear before him, and to ensure that the rating of each individual on the ship's books, according to which his pay is proportioned, shall be consistent with his merits. In addition to this, all classes on board, from the highest to the lowest, are brought under the immediate notice of their Commander-in-chief, a measure which is always attended with beneficial results. So complete

[page] 5

were the arrangements of the Chanticleer, and so much attention had been paid to them by Lieutenant Austin to whom the duty principally belonged, that the Admiral expressed himself well satisfied with the state of the vessel, and her efficiency formed the subject of a very favourable report to His Royal Highness the Lord High Admiral.

In the course of the voyage, Captain Foster was directed to make observations at sundry places in the Atlantic ocean near the equator, as well as in high southern latitudes, and these being of a nature to produce considerable delay, so as to prevent fresh provisions from being obtained, a large quantity of Donkin's preserved meat was supplied. Another acquisition deserves to be mentioned, as it proved of the utmost consequence in preserving the health of the crew in the cold and boisterous regions of South Shetland. This consisted in Frazer's stove, an article which has undergone a three years' trial on board the Chanticleer, and its good qualities have been the constant admiration of every one on board. The provisions were cooked by it in bad weather and in a boisterous sea equally as well as if the vessel

[page] 6

had been in harbour; and although the hatches might be battened down, no inconvenience whatever was experienced from it, an advantage which can only be fully appreciated by those who are accustomed to small vessels. The consumption of coals which served for the culinary purposes of the whole crew for one day amounted only to one bushel. As its efficiency depends on its retaining a certain degree of heat, any wood that is of a soft nature is not calculated for it when coals cannot be obtained; but we found the hard wood of tropical countries to answer perfectly well. The only objection which can be advanced against it is the wear of iron plates, and even this may be guarded against by taking spare ones. These plates are apt to crack and split, a fault which might perhaps be in some degree prevented by placing a bar of iron on them while in use. On the whole, Frazer's stove may be considered as a most valuable acquisition to a ship.

It was on the 27th of April that we commenced our voyage, in one of those delightful mornings of spring, when all nature is rejoicing and the heart is gladdened by the

[page] 7

cheering influence of a serene sky. The wind was light from the northward, not a cloud could be seen, and everything seemed auspicious to our voyage, while we silently glided from the vessels at Spithead. As we pursued our course down the Channel on the evening of the 30th of April, the Eddystone lighthouse was seen. In passing this solitary beacon, it is quite impossible to behold it without feelings of surprise and admiration. Distant nine miles from the nearest part of the coast of Devonshire, the rock on which it stands appears as if left by nature for the purpose to which the art of man has converted it. Firmly and proudly it stands amid the ocean's waves,

"Proof to the tempest's shock,"

at once the guide of the departing vessel, and the mariner who seeks to regain his native shore. The history of this lighthouse is well known. The first lighthouse was completed and lighted in the year 1698, and in 1703 it was swept away in a storm, with the architect who happened to be in it at the time superintending some repairs. The second (of wood) was completed in 1708, and in 1755 was destroyed by fire. The present superb edifice, which was

[page] 8

completed in 1759, being entirely composed of blocks of hewn stone and fastenings of massive iron, and put together under the direction of that celebrated engineer Smeaton, seems destined to resist the destructive violence of either element.

On the 1st of May we put into Falmouth, with the object of comparing the longitude as given by our chronometers with that determined by Dr. Tiarks, and to commence the chain of meridian distances at that place. The fine weather having afforded Captain Foster a good opportunity of complying with this part of his instructions, we attempted on the following morning to put to sea. A strong easterly wind made the sea run high, in consequence of which we broke our anchor. This unexpected event placed the vessel in danger, and obliged us to run for safety into Carrick roads, where we again anchored. Sailors are considered the most superstitious persons in the world, and those of the Chanticleer were certainly no exception. The accident was at once accounted for among them by our having attempted to sail on a Friday.

On the 3rd May, a fine favourable breeze

[page] 9

from the north-west enabled us to get to sea, and to make up for the delay occasioned by the misfortune of the previous day. We were soon outside of Falmouth pursuing our course to the southward. As our little vessel obeyed the impulse of her sails and darted swiftly through the water, the shores of our native land were less distinctly seen, and as they became mingled with the haze on the distant horizon, occasioned reflections which have fallen to the lot of many. Few and short are the moments for such reflections; the business of a ship is never done, and admits of little leisure for them; the sails, the course, the reckoning, and the weather demand incessant care, and the object of the voyage at length becomes the chief concern.

On Sunday May 10th, after an agreeable and pleasant passage, we saw the high land of Porto Santo, which at a distance appears to be a rocky barren island with rugged hills. It is thirty miles distant from Madeira, and is inhabited only by a few fishermen. In the afternoon we saw the Brazen Head, one of the headlands of Madeira. The lofty summit of this beautiful island, as usual, was enveloped in masses of dark clouds, the lower hills were half

[page] 10

concealed by haze, and as we skirted the rocky shore on our way to the anchorage off Funchal, no part of it presented any indication of that exuberant fertility that is naturally looked for in this land of vineyards. The island of Madeira has so often been the theme of panegyric, and described in such glowing colours by many persons who have visited it, that I had long dwelt in imagination on its beautiful scenery, and there was no place that I was more desirous of seeing. The "Paradise," and "Gem of the ocean," are names which have been lavished on Madeira; it is the usual portal to the tropics, and is generally visited by outward-bound ships, with a view to procure wine and refreshments.

Madeira has no good harbour; the anchorage in Funchal roads is open and exposed, and is considered by nautical men as very dangerous when the wind blows from the southward. The usual custom is to put to sea immediately on these occasions; but some of the old residents affirm that there is no danger in attempting to ride out a gale from this quarter, as it rarely continues long. It is said that no vessels with good ground tackle have

[page break]

[page break]

[page] 11

ever been lost by pursuing this plan, and that many in attempting to get away at the commencement of the gale have been driven on shore. Vessels of moderate size might anchor in safety under the Loo or Black-rock, where a small break-water might easily be formed. During the Chanticleer's stay at Madeira, the Duke of York steam-boat arrived from Lisbon, and made an excursion to the neighbouring island of Porto Santo. Many of the people of Funchal took the opportunity thus afforded them of visiting that island.

On the 17th May, our observations for the longitude of Funchal having been completed, we sailed for Teneriffe, and on the 19th we saw the celebrated peak of this island distant ninety miles. Great as this distance was, it is said to have been seen at one hundred and fifty miles; and its height would render it visible beyond this, if the atmosphere allowed.

The small town of Santa Cruz is situated on the south side of the island of Teneriffe, which at a distance presents a rugged and barren appearance. A series of elevated ridges and pointed peaks rise in succession above each other, with precipitous shelving sides divided

[page] 12

by deep fissures and ravines, forming altogether a most unequal surface of bare and sterile rocks with scarcely a sign of vegetation or a rill of water. Such was the appearance of the island as we approached the roadstead of Santa Cruz, where we anchored in the course of the forenoon of the 20th.

Although Santa Cruz is the principal seaport and capital of Teneriffe, the riches and fertility of the island are to be found at Oratava on the opposite side of it, where the wine is chiefly made and shipped when the weather allows. Santa Cruz is frequented by outward-bound ships for the purpose of obtaining a stock of wine, which can be procured at a cheaper rate and frequently of as good a quality as that of Madeira. At the time of our visit, the price of very good wine was 20l. the pipe of a hundred imperial gallons; this was called the 'London particular;' but the best old cargo wine is only 12l. the pipe, and in general cannot be distinguished from the ordinary wines of Madeira.

Santa Cruz has been often described: we met with much courtesy and civility, and were gratified by the attentions we received. The

[page] 13

market is well supplied; but the town is rather badly off for water, which is conducted by a wooden aqueduct across valleys and hills to a fountain near the Plaza Real. The whole of the Canary islands are in possession of the Spaniards; and the difference of costume between the people of Santa Cruz and those of Madeira is particularly striking to the visiter. The peasantry and poor class of the inhabitants appear to have very little to do, and are in a destitute condition, although better clad than those of Madeira. The dromedary is chiefly used as the beast of burden, and appears well adapted to the island.

We left Teneriffe on the 21st May, and were delayed by calms the two following days. On the morning of the 23rd, the surface of the sea was covered with very minute particles of something which appeared like dust or the shakings of hemp. Having obtained some of it in a vessel, on examination I found it to be composed of very small worms, extremely slender and delicate, and about the hundredth part of an inch in length. They were of a brown colour in general, and acuminated at each extremity, having also a slight bending

[page] 14

motion at times. Besides these, the water from which I had taken them contained a few hairy globules, about the size of a pin's head, which opened and contracted, having a bright glistening speck in their centre. There were besides these some little red capillary worms, bifurcated at one extremity, and some medusæ, of a chocolate colour, about the size of a pea. Captain Flinders, on his way out to Australia, mentions having observed a similar phenomenon. At page 92 of the first volume of his work, when in latitude 32° S. and longitude 104° E. he says there was a red scum on the water, some of which was examined with a microscope by Mr. Brown. It was found to consist of minute particles, half a line in length, composed of several cohering fibres; the fibres being of unequal length and the extremities appearing torn. These particles exhibited no motion when in salt water. Captain Chandler in 1766 says, "In some parts of the sea are parcels of matter of different colours, sometimes red, sometimes yellow, floating on the surface. It appears like the sawdust of wood, and sailors say it is 'the fry of the whale.' This appearance has been frequently observed by sailors.

[page] 15

The sea, particularly in warm climates, teems with myriads of animalculæ, and a calm is favourable for observing them. They are frequently found to cover a vast extent of surface. The phosphorescence of the sea, which has so often engaged the attention of naturalists, is sometimes connected with these animalculæ, and at other times is occasioned by medusæ (Medusæ scintillantes). I have repeatedly shaken a bottle of water in a dark place, and have observed little specks of light in it from the animalculæ it contained, when no medusæ could be detected even by the microscope."

On the morning of the 29th May, we made the island of St. Antonio, one of the Cape Verds, at which our orders directed us to stop for the purpose of including it in the chain of meridian distances, and thereby getting its correct longitude. The west point of this island is generally the last land seen by ships going round the Cape of Good Hope; and the establishment of it as a point of departure for them in particular, was an object of great importance. We had entered the limits of the trade winds in the latitude of 23°, but had carried a fine north-east wind from Madeira.

[page] 16

The weather now became hot, but at the same time it was not oppressive, and the nights were particularly delightful and refreshing. Saint Antonio is the northernmost of the Cape Verd islands, and, when approaching, it has the appearance of a rocky barren mountain risen abruptly from the ocean. The peak of the island was estimated on board the Chanticleer at 9700 feet high.

When we had approached the island sufficiently near, Captain Foster went on shore to make observations, while the Chanticleer remained under sail, waiting his return. He had no sooner landed than a solitary negro made his appearance from among the rocks and approached him, holding out a pumpkin for his acceptance. We had invaded his solitude, for this part of the island has no settlement, and he was naturally anxious to know the object of our visit. We soon made him comprehend that fish and vegetables would be acceptable, and the next minute he provided himself with a cane armed at one end with a nail, and to our surprise plunged into the sea. Here he continued floating and swimming about, supporting himself in the water with one hand, while

[page] 17

with the other he made use of his weapon among the finny tribe, employing each hand alternately in this manner. This was to us altogether a novel mode of fishing; but not so to him, for in the space of two or three hours which were occupied by the observations, he had caught six fine cavalloes, weighing about nineteen pounds, besides several other smaller fish. With these spoils and ten pumpkins he came to Captain Foster and offered them for sale. He was a fine well-made man, and, although entirely alone, he appeared to be perfectly satisfied with his solitary condition. Captain Foster accompanied him to his cave, near to which he had a small piece of ground under cultivation, and on this, with the produce of his fishing expeditions, he depended for subsistence. His cave was small and confined; it was ill calculated to afford shelter in any other than a tropical climate, and appeared to be the residence of some wild animal rather than that of a man. A few leaves answered the purpose of a bed, and some broken calabashes were the only utensils it contained. The shortness of our stay prevented us from learning the reason of his having chosen this extraordinary mode of

VOL. I. C

[page] 18

living, but we found that occasionally he visited the people on the opposite side of the island.

Saint Antonio, like the rest of the Cape Verd islands, is of volcanic origin; indeed most of those in the Atlantic are based on volcanic ridges, and the coral rocks are forced above the surface by this powerful agent. The island of Fogo, one of the Cape Verds, which is the cone of a volcano protruding above the surface of the sea, is constantly emitting smoke and ashes, and was so named in consequence of it. These islands are generally healthy; they are frequented by whalers and sealing vessels for salt, which is their principal article of commerce.

On the night of the 30th May, we were much gratified by a phenomenon of rather uncommon occurrence relating to the phosphorescence of the sea. It was about ten at night, while the vessel was sailing through the water at the rate of about five knots, the weather clear and the stars shining brightly above us, when our attention was suddenly attracted by a great number of dolphins sporting round the ship, and darting about in all directions with the swiftness of an arrow. The water was extremely brilliant, and appeared to be a sea of

[page] 19

stars, so numerous were the specks of light; and the wake of the vessel, as she passed through it, was marked by one continued train of light. But beautiful as this was, we had been in some degree accustomed to it, and our attention was directed to the dolphins. We could distinctly see their whole form to a considerable depth below the surface of the water, from the bright light which they emitted, and were delighted with their gambols. A train of vivid light, not unlike that left by a rocket in its flight, but more continuous, suddenly appeared, and marked the dolphins to be in pursuit of prey; a cracking noise was repeatedly heard in various directions on the surface of the water, and we soon found that it proceeded from the blowing of these fishes as we observed them again darting away in pursuit of their prey. I remember having seen a quantity of porpoises nearly in this place a few years ago in latitude 10° N. and longitude 26° W. and it is not unlikely that there may be some bank or other cause to make it their favourite resort. Labilliarde, who went in quest of the unfortunate Perouse, mentions his having met with a great many dolphins

C 2

[page] 20

about the same place. He found the ship among them as we had, and observes that it was easy to trace them by their luminous track.

By the 2nd June, we had fairly entered that part between the tropics which is known to sailors by the name of the variables, and, in a voyage where it is necessary to cross the line, is generally the most unpleasant part of it. Light airs and squalls of wind from every quarter, interrupted by calms, alternately succeed each other, attended with heavy rain and dark cloudy weather, the heat of which is very oppressive. This evening we observed lightning vivid in the extreme; and as the whole surface of the sea around us, as far as the horizon, became illumined by the successive flashes, the scene which presented itself was awful in the extreme, and was rendered still more so by the loud peals of thunder as they burst over our heads and died away in the distance. We were deluged with rain and compelled to be shut up below with the hatches battened down, in a close suffocating temperature of 86°, the atmosphere surcharged with moisture. The space which is occupied

[page] 21

by the variables is very uncertain, and depends on the position of the sun in the ecliptic. Sometimes they extend over six or seven degrees of latitude between the limits of the north-east and south-east trade winds, and at other times the limits of these winds are so near each other as to exclude the variables entirely. In crossing the variables, it is also the concern of the navigator to avoid being set over to the coast of America by the equatorial current, which runs to the westward sometimes a mile and a half per hour.

Day by day we were wafted a few miles; and on the 12th June, in latitude 2° N. we met a light breeze from the south-south-east, the first of the south-east trade. In the latitude of 6° N. as we lay becalmed, we observed the sea covered with the same dust, like the shakings of hemp, similar to that previously seen, but on examining the particles of it, they differed from the former and showed no signs whatever of animation.

During the long calms by which we were delayed in the vicinity of the equator, I had an opportunity of examining several kinds of medusæ, or the sea blubber. One day, while

[page] 22

some of our crew were bathing in a sail secured for the purpose by the side of the vessel, several of them were severely stung by these medusæ, and Mr. Miers, the carpenter, was so much injured by them as to be unable to swim. He suffered much pain and irritation in consequence, but nothing further. I have frequently handled them, and immediately afterwards, on applying my hands to my lips and face, have experienced some degree of pain, from which I am inclined to believe that it proceeded from the secretion of some acrid matter rather than from any electric property. I contracted a disease on my hands much resembling the itch in consequence of handling the medusæ and the physalis, or, as it is commonly called, the Portuguese man-of-war.

The medusa caravella was very common. The under surface had three pendulous arched processes joined to each other; and I am inclined to believe, that their food enters into the central or digestive cavity, around which is spread a loose delicate fimbriated membrane, tinged of a light pink colour, and which appears to serve at the same time the purpose of an intestine and aerating membrane. This

[page] 23

bears some analogy to the structure of the aphrodita aculeata, in which numerous minute tubes continued from the intestines, ramify through the body, and terminate in little oval cells or cæca in contact with the pulmonary vesicles. The medusa appears to be more simple From the edge of the under surface were four delicate annulated chains, which possessed great contractile power; the circumference of the medusa was capable of considerable motion of the same nature. On cutting open the medusa, I found a small worm in its cavity, and some curious brittle glasslike substances, nearly the tenth part of an inch in length. The purpose of these I could not discover, but conjectured that they might act as ventricular or stomach teeth, to lacerate and entangle the food. Medusæ, or blubber, are generally supposed to consist of slimy gelatinous matter, but they are merely hydrophanes or water cells, analogous to the vitreous humour of the eye, for when punctured and hung up to drain, the water runs from them and leaves an almost impenetrable shred of membrane; and yet this lives and is capable of considerable motion.

[page] 24

In the course of our examination of the blubber, we picked up some blue globose substances, armed with lateral processes, which they cast off with great rapidity, and prevented our investigation of them. While trying the rate of the current, on hauling up the lead a small sucking fish was found adhering to it. The size of this was not more than four inches long; it was of a blue slate colour, and the oval disc or sucker on its head had seven serrated laminæ. The tail of the fish was trifurcated, which distinguishes it from the known species of its genus, and I proposed to name it echeneis trianarus. These little creatures adhere to anything. On some parts of the coast of Africa these fish are very numerous. His Majesty's ship North Star, while on that station, had so many sticking to her bottom that her sailing was impeded by them; and as the most effectual mode of clearing them away, she went up one of the rivers, that the action of the fresh water might effect it. Columbus, it is said, in the course of his voyage among the West India islands, observed some natives fishing from a canoe, and was struck with the extraordinary means they adopted

[page] 25

This was nothing more or less than a sucking fish, which they allowed to fasten itself to a fish, and thus drew them both out of the water together.

At sunset, on the 4th June, we observed a radiated cone in the eastern horizon, the base of which extended towards the zenith. The general colour of the rays by which it was formed was pink, with intervening ones of bright blue, and those on the exterior of the cone were also blue of a green cast. At the time we observed this cone, the clouds in the western horizon were of a deep black, with rather a blue cast. This cone lasted about seven minutes, and was the most splendid of any that we saw. Between the tropics at sunset and sunrise, there is a tendency to form the zodiacal light, or diverging beams of a pink or roseate hue based in horizon.

During our passage through the variables, the mean temperature of the air was 80°, and that of the sea-water at the surface was the same. The temperature of the rain-water, which we frequently tried, was 76° to 78°, a near coincidence with the dew point, which, however, was a very difficult matter to obtain

[page] 26

in these regions with accuracy. The heavy rains that we experienced cooled the air, and brought down the thermometer two or three degrees, at the same time that it diminished the temperature of the surface water of the sea. In a warm atmosphere thus saturated with moisture, mildew formed with great rapidity. The foresail and awning became permanently dyed of a sooty colour, from the mildew which formed upon them in the open air; and in the short space of twelve hours, wet or washed linen, that was hung up for the purpose of drying, soon became spotted with mildew; black silk handkerchiefs in the officers' drawers became covered with red and ash-coloured spots; drawing paper was spoiled; shoes were covered with mildew, and in the space of a few hours were found with woolly filaments inside of them; the under side of the chairs on which we sat were mildewed; damp clothes in a dose place were quickly covered with fungi; the stains on the linen and cloth were permanent, and could not be effaced by washing, although the texture of the cloth was not injured: these results frequently employed our speculations.

[page] 27

During the calms we frequently sent down the sounding lead to a depth of four hundred fathoms, with Sykes's thermometer and Dr. Marcet's iron water-bottle attached to it. We invariably found the surface water to be 80°, and at four hundred fathoms below the surface it was 44° Fahrenheit. The water brought up in Marcet's bottle always indicated a higher temperature than Sykes's thermometer. The above experiments were made in a fathomless sea, one hundred miles from the equator. The sea at night frequently broke with a phosphoric flash, like that of sheet-lightning, but the scintillating appearance of the water was very much diminished.

On the morning of the 17th we saw St. Paul's rocks, distant fourteen miles from us; and on the 18th June we crossed the equator, and made the island of Fernando Noronha on the 20th. We were not long approaching the island, and anchored in Peak bay. Our stay during six days was employed in making observations, during which time we found some relief from the oppressive heat which we had lately experienced. The thermometer was generally at 80°, with a cool refreshing breeze.

[page] 28

As our orders directed us to return to this island, I have deferred my remarks on it for a future page.

Having sailed from Fernando Noronha on the 26th of June, by the 6th of July we had made sufficient progress to the southward to obtain soundings, on the Abrolhos bank in the latitude of 17° 35′ S. and long. 37° W. in twelve to sixteen fathoms. The question whether shoals and rocks produce any diminution in the temperature of the water near them now employed our attention, and we were very careful in making our observations on this bank; but with all our care we could discover no particular change, and concluded that the vicinity of shoals within the tropics is not denoted by any coolness in the water. We obtained some fuci and ulva of bright green colour, resembling that of grass; and in the course of our progress I could not detect any want of colour in sea weeds obtained from a depth of fifty fathoms, whatever may be the effect on them of the presence or deficiency of light at that depth.

At daylight, on the 11th of July, we observed a rakish-looking schooner bearing down upon us. Having neared us, she fired a gun,

[page] 29

and hoisted Brazilian colours; Captain Foster thought it best to disregard her motions, and accordingly we took no notice of her. But on seeing herself thus slighted, the schooner made sail after us, determined, apparently, to give us some trouble from the suspicious nature of her appearance. The Chanticleer was not intended for a fighting ship, having only two guns; nevertheless, we could take care of ourselves, which our companion did not seem to be aware of, and we accordingly beat to quarters, and prepared for action. By this time the schooner had gained upon us considerably; and having everything ready, we wore round and hove to the wind, to wait and give her as warm a reception as we could, with our two guns and a handful of marines.

Our preparations had not been unobserved, for as she came near us she altered her course on a sudden, and sheered off without even paying us the compliment of speaking, or ascertaining who we were. We had no intention of pursuing her, for the mission on which the Chanticleer was sent admitted of no such proceeding; therefore we continued on our course for Rio Janeiro, and in the evening we lost

[page] 30

sight of our new acquaintance. At ten P.M. some of the officers believed they saw lights, which we imagined could proceed from no other vessel than the schooner, and it was supposed that she was hovering about us to take the little Chanticleer by surprise. Determined on being prepared at all points, Captain Foster summoned his men again to their quarters; the sails were trimmed so as to be easily handled; and at the same time, to keep the vessel in command, the two guns were got ready and everything prepared for our troublesome visiter as before; and although we could not show so many teeth as he, yet in physical force we thought ourselves superior to him. We continued at quarters all night, but in the morning found no signs whatever of the schooner.

At about eighty miles from the coast we observed a change in the appearance of the water, which from a deep blue colour became of a dull green. On the 13th July we made Cape Frio, and experienced the long wave termed by seamen ground swell, which is a good indication of the vicinity of the land. Cape Frio is an important headland to navigators, being generally the last defined point of

[page] 31

the coast seen in leaving Rio and the first on going there, and its correct position is therefore an object of considerable importance. The cape is sixty-four miles from Rio Janeiro.

Having neared it sufficiently, Captain Foster left the vessel in his gig for the purpose of making observations on the Cape for its latitude and longitude. Having succeeded in obtaining these, he returned on board, and we pursued our course for the harbour of Rio Janeiro. There is very good and secure anchorage for ships of any size in the harbour formed by the island, the south point of which is Cape Frio. The largest entrance, which is that to the northward, has a depth of twenty-two fathoms. The country about is very mountainous, apparently well covered with wood and supplied with water. The island is rocky and covered with cactuses. The rock is principally formed of feldspar and quartz; the feldspar decomposing into beds of petunse, or porcelain clay. Some of the most perfect specimens of marine grotto work were obtained from it. The aggregation of shells and the deposit and incrustation of coral upon them produces a very beautiful appearance.

[page] 32

At day-break on the 16th we observed the islands at the mouth of the harbour of Rio. The sea breeze at this time of the year is very irregular in its arrival on the coast, and we lay becalmed during the greater part of the day. In the afternoon a light breeze wafted us slowly towards the harbour's mouth, and gave us ample opportunity for enjoying the magnificent scenery which presented itself. Mountains of steep and sudden declivity rose abruptly from the sea on every hand, their lofty summits terminating in peaks and ridges covered entirely with one dark mass of verdure. To a stranger, whose eye is familiar with the coast scenery of England, that of South America is peculiarly striking. The scale of Nature is totally different. He is lost in admiration at the lofty grandeur of the mountains, which in some places presenting abrupt high precipices, in others gradually subside into luxuriant valleys and fertile glens, rich in all the stores of vegetation and glowing with the beauty of eternal spring. Sequestered dells are alternately succeeded by extensive plains assuming every varied form, and the Corcovado mountain rears its lofty summit in proud pre-

[page] 33

eminence over the heights in the vicinity of Rio Janeiro. In going into the harbour a remarkable hill presents itself on the left, which, from the resemblance it bears to a sugarloaf, has received that appellation. It rises abruptly from the water to the height of one thousand and fifty feet. The entrance to the harbour is narrow, being guarded on the right by a strong fort called Santa Cruz, where an officer and party of men are stationed. It is the duty of these persons to hail every ship that passes, and a boat generally comes from it to ascertain what ship is entering the harbour. Immediately within the entrance of the harbour the shores on either side recede from each other to a considerable distance, leaving an extensive basin, which is generally considered one of the most magnificent harbours in the world.

Cheerful and animating as is the whole scenery which presents itself on entering the harbour, not only from the bounties of Nature, but the numerous vessels which are sailing about and at anchor, I felt some disappointment in beholding it. Some years ago I had visited this celebrated port, when my heart was light and life was in its spring. Well do

VOL. I. D

[page] 34

I remember how delighted I was then with the glorious scenery of Rio Janeiro; and I had fondly anticipated a renewal of such feelings. But my young fancy, then so vigorous, was now sear and in its yellow leaf; imagination. drooped her pinion; and I wanted that enthusiasm and high tone of feeling which is the accompaniment of youth. At first I satisfied myself with the belief that it was in the height of summer, when Nature wore her most resplendent robe, that I had contemplated the beauties of Rio with the fond attentive gaze of youth, and I persuaded myself that this was the winter. But alas, all around was as glorious as ever—the change was in myself; it was my own infirmity, and life's evening shades, which had induced a solemnity of thought, and deprived of its charm the scene that had once imparted the feelings of joy. I shall never forget the impression it made on my mind; it was the first time that I had known such a feeling.

"Still at our lot it were vain to repine;

Youth cannot return, nor the days of lang syne."

We dropped anchor in the harbour at six in the evening, and soon learned that the vessel

[page] 35

which we had met outside answered to the description of a well known pirate that had attacked some of our vessels on the coast. On one occasion her captain boarded a ship, and having bound the master of her, threatened to blow out his brains if he did not deliver up all his money, at the same time that his men were plundering his vessel. The master in this condition begged hard that his watch might be spared, as it was his mother's gift. "Fool," said the ruffian, "I thought you were old enough to have forgotten your mother—what will your mother's gift avail you if you lose your life, which you will forfeit by your obstinacy?" This privateer mounted twelve guns, and all her crew spoke English.

D 2

[page] 36

CHAPTER II.

Some account of Rio Janeiro.

THE city of Rio Janeiro stands on a dry gravelly soil, close to the southern side of a capacious bay. It occupies a space of nearly two miles in length, and about three-fourths of a mile in breadth. A ridge of lofty hills flank the city, and by surrounding the spacious basin which forms the harbour, imparts an air of grandeur to the whole scene, as it appears from the anchorage. On an eminence in the town, and near the harbour, stands a church, which was the first established at Rio, and from which the city obtained the original name of San Sebastian. The circumference of the basin forming the harbour is about thirty miles in extent, and is surrounded by lofty mountains. Among the principal of these is the Corcovado, which translated, signifies "Parrot's-beak." The peak of this mountain is two

[page] 37

thousand feet high. Beneath the Corcovado, in a lower ridge, are quarries of beautiful gneiss, which is used as a building stone at Rio. Close by these is the village of Bota Fogo, on the shore of a little tranquil bay, on one of the elevated points of which stands the church and convent of Gloria. Bota Fogo is delightfully situated, and contains several good houses, which are occupied by genteel families. The lofty and picturesque peaks of the Organ mountains appear over the inner part of the harbour, clothed with luxuriant foliage, and are three thousand two hundred and ten feet in height. The harbour of Rio Janeiro has but one fault, which is, that of being too large: ships of all nations are generally found in it, but on our arrival there was no British man-of-war at anchor there. Shortly afterwards, however, his Majesty's ship Ganges arrived, with the flag of Rear-Admiral Otway; and soon after his Majesty's ship Blossom, commanded by Captain Beechey, on his way home from the Pacific Ocean, whither he had been sent for the purpose of penetrating as far as he could up Bhering Strait, to meet the polar voyagers, Sir Edward Parry and Sir John Franklin.

[page] 38

Rio Janeiro is the metropolis of the great and important empire of Brazil. It is situated on the western side of the basin before mentioned, about three miles from the sea at its entrance. The site of the city is judiciously chosen, and is in every way adapted for the seat of government and commerce; but the city itself does not correspond with the splendid scenery by which it is surrounded, although it is large and populous, tolerably well built, and contains good commodious houses. The streets are very narrow. and lie at right angles to each other; they are well paved, but badly lighted. The houses are generally lofty, and the lower windows being covered with latticed work, give them very much the appearance of being shut up. The usual custom of the Portuguese is adopted here, of a particular street being occupied by those of a particular trade; and a stranger who has not paraded the streets of Lisbon, would be struck by seeing one filled with jewellers and silversmiths, another with milliners; indeed, so far is this regulation observed, that even the pork and beef butchers must have a street separate from each other. The various tradesmen appear to have a large

[page] 39

stock on hand, but the shops have in general a dirty slovenly appearance, not to be compared with the neatness and order of those even of the second class in London; and while the boards of the jewellers glitter with the amethyst, the topaz, and the diamond, a want of taste in their arrangement and finish in the gold and silver work materially lessens the effect which they are calculated to produce by their profusion and richness. Rio Janeiro is celebrated for the variety of its precious stones, the produce of the mines. The practice of numbering the houses, even on one side, and odd on the other, in the same manner as adopted in Regent Street of our metropolis, is observed here, a system which is attended with much convenience.

Like other foreign cities, Rio Janeiro, having no sewers, is very deficient, in point of cleanliness, and the houses are subject to the great inconvenience of a want of water. This article is supplied by means of an aqueduct built on two tiers of arches. At its commencement, which is a short distance from the city, the water gushes from a precipitous rock, and soon after passing beneath a convent, it is con-

[page] 40

ducted to various parts of the town. The large fountain is situated in the principal square of the city, named Largo do Paco, over which appears the following Latin inscription:

"Ignifero curru populos dum Phœbus adurit,

Vasconcellus aquis ejicit urbe sitim;

Phœbe, retro propera, et cœli statione relicta,

Præclaro potius nitere adesse viro;"

which may be thus translated nearly literally:

While Phœbus is riding in fiery car,

And fearfully scorching the earth at his will,

The horrors of thirst Vasconcello afar

Expels from this city of favoured Brazil.

Oh! Phœbus desist, relinquish thy throne,

And make the design of the hero thine own.

This fountain being by the sea-side, the boats from the shipping easily obtain water from it; and to supply the houses, forms a part of the duty of the numerous slaves who are in the city. It is the duty of these people also, to carry to the water-side all dirt from the streets and houses. But if filth were productive of disease, and malaria was the exciting cause of fever, Rio Janeiro surely would be severely visited, for heaps of filth are scattered about on the beach and in the suburbs; and yet the city is healthy, no virulent endemic is found there, and the general purity of the air seems to be unimpaired.

[page] 41

The grand square, which is immediately overlooked by the palace, adjoins the water-side, and contains the great public landing-place, so that a stranger enters immediately into the best part of the town. In the evening it forms an agreeable promenade, and has a parapet wall along the water-side, with stone seats for the accommodation of the public.

A stranger on landing at Rio Janeiro is immediately struck by the great number of slaves, which may be said to infest the streets. As he leaves the landing-place, his ears are assailed by their monotonous shouts and the rattling of chains which proceed from the various parties of them as they perform their work. These unfortunate creatures supply the place of the beasts of burden to the people of Rio, and are to be seen linked together drawing carts and sledges, and performing other laborious duties, with an apparent unconcern and a degree of hilarity which are hardly credible.

It is the custom of the slaves, and it appears to be general among negroes, to accompany their labours with their own native music, at least with such as their voices afford. This has no doubt the effect of inspiring them to

[page] 42

greater efforts; and the streets resound with the echo of their uncouth song and the rattling of their chains. They are accompanied and superintended in the performance of their duties by an armed military force; but their number now amounts to a fearful height, being two-thirds of the whole population of the city; and the inhabitants of Rio Janeiro, like those of imperial Rome, may one day suffer from the effects of their temerity. A precedent is afforded in the New World, and at no great distance from them; the awful tragedy of St. Domingo, with all its horrors, appalling as they are, may yet be repeated in the capital of Brazil.

Some of the slaves go about in these working parties entirely naked, exhibiting shocking proofs of ill-treatment on the back, face, and neck; and from the number of these scars which a slave carries about him, a tolerably correct opinion may be formed of his character, as well as that of his master. Among the slaves are the best artisans and mechanics which the country can boast, and many who are often entrusted with the business of their owners, and fill the office of confidential ser-

[page] 43

vants. Some lead a happy life in the quiet circle of their masters' families, others are not so fortunate; but the natural buoyancy of spirit which they all possess renders them capable of undergoing any kind of living; and in the midst of their hardships, and while labouring under the severity of their toils in a broiling sun, the joyful laugh, the animated gesture, and the song of mirth, characterize them as contented and happy.

So predominant is this feeling among them, that those still on board the vessels in the harbour, just torn from their native land, are equally as unconcerned for their condition. It is always painful to contemplate sights such as these, and we are prompted to ask of ourselves,

"Was man ordained the slave of man to toil,

Yoked with the brutes and fettered to the soil?"

But a benevolent Providence has made them contented with their lot; they know no repining, and appear happier than is imagined by our most considerate philanthropists.

The churches and convents of Rio Janeiro are numerous and very respectable. They are in general conspicuously placed, those of San Francisco and Candelaria being most worthy

[page] 44

of note. Many are handsomely, and some gaudily, decorated with images and paintings. This system is greatly objected to by some people, but for my own part I think that suitable and appropriate ornaments belong to the temple of God; not that they should in the least influence our conduct there, but that the devotion of worldly riches to such a purpose evinces our desire of honouring the mansion in which we assemble with the only means in our power, while we prostrate ourselves before our Creator. The service of the Catholic church, as seen here, appears to have as much reference to the ships in the harbour as to the people of Rio Janeiro, and to approach in some degree the ceremony of the Roman augurs. The Catholic religion has engrafted upon Christianity such an incongruous mass of forms and ceremonies, that the purity and simplicity of its divine precepts are overshadowed by the glittering of toys and images. It is a religion that works on the imagination without convincing the reasoning powers of man; it takes captive the homage of the simple and those of slender minds and an easy faith.

In Rio Janeiro, since the accession of Don Pedro, Catholicism has been shorn of its over-

[page] 45

weening influence, and the immense revenues of the churches have been much curtailed. As a proof of the progress of liberalism, we now find that the Bible is allowed to be circulated. A short time since, a person who might be found with a Bible in his possession was declared guilty of an offence, the punishment of which was transportation: but in addition to this progress in religious toleration, a protestant church has been erected, and the duties of it are duly performed by an English clergyman.

In the famous city of Rio Janeiro, not long ago, a bookseller's shop was rarely to be seen, but there are now several of very fair pretensions, although it must be acknowledged that the book-worm is as yet the greatest encourager of literature, by destroying the publications of Europe soon after they appear, and thereby increasing the demand for them. Two Journals are published every week; and an English school has lately been established in the city for the purpose of instructing the natives in our language.

The public gardens of Rio Janeiro are situated at Bota Fogo; but neither on account of their forming promenades, nor as possessing

[page] 46

great interest as gardens, are they kept in a decent condition. On the contrary, they are allowed to remain in a very neglected and slovenly state. The Botanic Garden is about nine miles from the city, and near the extraordinary mountain called the Sugar-loaf. The tea plant has been tried there on an extensive scale, but the experiment has not succeeded, the produce having been rejected as useless. Various other exotics are cultivated in this garden, such as cinnamon, nutmegs, &c.

Rio Janeiro is not without its hotels and caffés, among which are the Hôtel du Nord and Hôtel de l'Empire, where strangers may be accommodated. Soups, stews, and rich dishes, form the favourite articles of food; and they have a method of stuffing cabbages with forced-meat balls, a dish which, perhaps, even Dr. Kitchener's profound experience in the culinary art could not boast.

The Museum is well worth visiting, and contains some magnificent specimens of the riches of Brazil. The Opera-house is also well supplied with performers; but among the public places of Rio, the Campo d'Acclamacaõ forms an important feature, not on account either of

[page] 47

the buildings which surround it, or of any particular superiority belonging to it, but in consequence of its being the place where the independence of the Brazilian Empire was proclaimed in the year 1823. It is a large square, about a quarter of a mile in extent each way, and situated at the west end of the city. It is ornamented by a handsome public fountain, and a rostrum, which was regularly visited by the Emperor Don Pedro, on the anniversary of the independence, for the purpose of ratifying and renewing the contract between himself and the people.

The population of Rio Janeiro now amounts to about one hundred and fifty thousand Brazilians, Portuguese and slaves; but in this number is included a few French, German, and English merchants, of which the French are the most numerous class, and possess respectable stores of merchandise. The English residents are more wealthy, while the Germans are artisans and soldiers. But of the motley collection of persons living in this city, with principles and feelings as opposite as their dialects, it is difficult and almost impossible to convey a correct idea. Here law, indeed, may

[page] 48

be said to be scarce; but, unfortunately, justice is equally so, and a looseness of morals and carelessness of bringing offenders to trial prevail to a fearful extent. There is no public prosecutor, and the Government takes no cognizance of crime; the police is bad, and unless the unhappy victim of revenge were again brought to life, to act as the accuser, the sensation produced in the city at the account of his murder gradually wears away, and the assassin is secure. The laws may be good in theory, but if so, they are not practised. It is impossible to arrive at the amount of crime in Rio Janeiro. In England the press proclaims the good and bad, so that foreigners are surprised at the daily catalogue of delinquents; but the weak and servile writers of these parts care not who plunders or who assassinates, their press is neither employed in warning others of their danger, nor assisting to bring offenders to justice; instead of doing this, which would really benefit their country, they are engaged in forming some vehement and empty political declamation, or some useless and abstract theories of government which may happen to be the fashion of the day.

[page] 49

The commerce and revenue of so rich an empire as Brazil ought to be great. Vessels of all nations are to be found at her capital, but those of England are the most numerous. The imports from England are estimated at six millions sterling, and consist of all manner of dry goods. Flour is imported in large quantities from the United States; and this article, as long as it continues to be the staff of life, will be to that country a treasure greater than gold and silver mines are to Peru. Besides flour, candles and soap are also exported in large quantities from America. Tea, silks, and crapes are brought from China by American ships; and there is, besides, a considerable coasting trade.

Coffee is the staple commodity of Rio Janeiro, and its good qualities are well known; but the sugar is deficient of sweetness, and the indigo is so worthless, from being neglected, that it is entirely excluded from the market. The tropical fruits of the season are to be had here in great plenty, but oranges are to be met with in profusion nearly all the year round. It is usual for the crews of his Majesty's ships on the South American station,

VOL. I. E

[page] 50

and also on other warm stations, to be supplied with fruit; each man is allowed six oranges per day, but they may be bought at the rate of about three pence per hundred. Ipecacuanha is the principal drug to be had at Rio, and is the produce of the country; but I was much surprised to find that several others, for which the place is dependent on the northern parts of the empire, are dearer at Rio than in London, and that they are often procured from London in preference to Para. This appeared to me extraordinary; but such is the uncertainty of the conveyance, and the want of that immediate intercourse with the different parts of Brazil, which a few steam-boats would soon rectify.

The tree-ferns on the Corcovado (polypodium Corcovadense) may be classed among the most elegant productions in the vegetable kingdom. These ferns grow to the height of twenty feet, and are frequently entwined with lesser ferns, thus clothing their stems with all the elegance of ivy. The anvil bird (proenias ventralis) is perched on its branches, and repeats its singular note, which sounds like the blow of a hammer on an anvil. The beauty of plumage, which forms the peculiar feature in the birds of

[page] 51

Brazil, is well known; Nature may be truly said to have lavished her favours in decking out the feathered tribes of these regions, for they are all remarkably handsome, and objects of admiration to every visiter. The insects are equally so, particularly the various descriptions of butterflies, many collections of which are sent to Europe. Fireflies, beetles, grasshoppers, are plentiful; the webs of some of the spiders are strong enough to entangle a little bird; and ants are so large that they are fried and made into a delicate dish. Snakes are very common and plentiful; every variety of these creatures is to be had, from the boa-constrictor of thirty-five feet in length, to the little delicate green snake, the length of which does not exceed four inches. Rio is tolerably supplied with fish. The shrimps are very large, and when made into pies are an excellent dish.

In articles of country manufacture Rio has little to boast. All that I could discover consisted of a coarse cotton cloth which is worn by the slaves, and a small quantity of leather tanned with the bark of the mangrove. Nor are the naval concerns of the empire in a much more flourishing condition. The few ships of

E 2

[page] 52

war that the emperor had, were kept in repair at a small dockyard, but the expenses of it seemed to be greater than the people were inclined to afford. The caulkers are good workmen, and generally find employment on board our men-of-war, when they are fresh from England. A ship, although she may have left one of our dockyards in perfectly good order, generally requires caulking from the effects of the climate.

The country about Rio in a geological point of view has large claims to attention. Granite and gneiss are the prevailing formation. The large rock called the Sugar-loaf, at the entrance of the harbour, is composed of granite; and all the rocks I could find were either of granite or gneiss, the former being traversed in all directions by numerous veins of quartz. Some of the hills below the Corcovado mountain are of gneiss which contains small garnets in considerable numbers, and the quarries from which the building stone is obtained consist entirely of granite. The soil in general is a redcoloured clay having a burnt appearance, and is very fertile. The rocks in some parts are decomposed into sand and petunse; the sand

[page] 53

having been carried down into the plains, while the petunse remains, and forms extensive beds of porcelain clay admirably adapted for the use of the potter. The lower parts of the granite hills were found chiefly in this condition; the granite having crumbled into micaceous sand and greasy unctuous clay.

The currency of the country is generally in much confusion, varying in its value from political causes. There is a depreciated paper currency at fifty per cent. below par. Copper coin is at a high premium, and silver is the standard.

[page] 54

CHAPTER III.

Continuation of the voyage.—The island of St. Catherine.—Produce.—People.—Peculiar quality of the Ferns.—Arrival at Monte Video.—Change of temperature.—River La Plata.—Prepare for Pendulum operations on Rat Island.—Military operations going forward.—State of the fortress.—Lieutenant Williams's adventure.—An awkward position.—The Garrison in confusion.—A false alarm.—Excursion to a Quinta.

AFTER twelve days' stay at Rio Janeiro, we departed early in the morning of the 28th July, and were no sooner fairly at sea than we were enveloped in fog, the first we had experienced since leaving England. We had the advantage, however, of a smooth sea, the wind being light, from the north-east.

On our way to the southward we were fortunate in having fine weather, the days being remarkably clear, but the nights attended with copious dews, so heavy that the decks in the morning were as wet as if it had been raining all the previous night. The average

[page] 55

temperature of the day was 70°, and that of the night 64° of Fahrenheit.

At daylight on the 1st of August we were much gratified with the beautiful prospect presented by the island of St. Catherine, and the coast near it. A Brazilian brig-of-war, commanded by Captain Hayden, an Englishman, happened to be going to the anchorage, and we both ran down before a fine sea-breeze, and shortly found ourselves snugly at anchor in a safe and spacious bay formed by the island and the main land of South America. We had a visit from Captain Hayden as a matter of etiquette.

The island of St. Catherine is the acknowledged garden of the Brazils. There Nature deals out with an unsparing hand all her choicest treasures to supply the wants of man. The view from the anchorage is of the most interesting description. The island is about thirty miles in length; and rises in some parts abruptly, and in others gradually, to a considerable height. The sides of the hills are clothed with the most luxuriant foliage, which is broken here and there by cultivated patches of ground, enlivened with the whitewashed huts of the natives, appearing still whiter as they reflect

[page] 56

the powerful rays of the sun. The shores of the island are much indented, forming little cheerful bays, some of which afford safe anchorage to ships from every wind. The island varies from two to five miles in breadth.

It is rather remarkable that, notwithstanding the richness of the country about St. Catherine, and the peculiar advantages in point of agriculture which this island possesses, there should be no large town near it. A mere assemblage of a few huts, hardly deserving the name of a village, is to be found at the bottom of one or two of the bays, while the island is scattered with them here and there. The village is protected by a fort named Anhatorim, which commands the entrance to the anchorage. The island produces every kind of tropical fruit and vegetables, but is mostly celebrated for its coffee and rice, the former of which is held in great estimation. Sugar, cotton, tobacco, and indigo, are extensively cultivated; and in addition to these, the natives prepare jerked beef, as well as bacon, for exportation.

The employment of the men consists either in cultivation or fishing, while that of the women is making cloth of the cotton, besides

[page] 57

their domestic pursuits. The indigo serves them to dye with; the cassada root furnishes them with bread, flour, and starch; and the bark of shrubs is converted into twine. The women also employ themselves in making hats with a kind of sedge, which grows plentifully; and shoes are made of the raw hides of their cattle. We found the people remarkably civil; they live a very retired life, and have a more healthy appearance than the inhabitants of Rio Janeiro.

The shortness of our stay prevented our seeing much of them; and the few remarks I was enabled to make on subjects of natural history are reserved for another place. One remarkable circumstance which came under my observation I will mention. In the course of my ramble in the island, when gathering ferns, I was particularly struck by observing that each plant had formed for itself a bed of fine mould of several inches in depth and extent; beyond the circle of its own immediate growth was naked rock; and this appeared so general, that I could not help attributing the extraordinary circumstance to their power of decomposing the rock, their fibrous roots penetrating into

[page] 58

every crevice, and by expanding in growth, appearing to split it into the smallest fragments.

Artificial flowers of feathers are made there, and shells are even very tastefully employed for the same purpose, both of which were freely offered to us for sale at a moderate price, as well as the beautifully feathered skins of the toucan. While we stayed, the weather was cloudy, but very tranquil; the mean temperature of the air was 68°, and that of the sea 70° of Fahrenheit.

On the 6th of August we left the island of St. Catherine, and observed the light on Flores Island as we passed it rapidly with a strong north-east wind in the evening of the 15th. In fact, we entered the river La Plata, or Plate as it is commonly termed by sailors, in a thunder-storm; we found our way in safely, and came to an anchor a little before midnight off Monte Video. As we approached the river, a remarkable change was observed in the temperature of the atmosphere, and the thermometer indicated a decrease of 10°, and there was a decrease of 16° in that of the water. Our approach to the river was also indicated by a

[page] 59

change in the appearance of the water, which from a bright blue colour assumed that of a turbid and dull green, attended with a short breaking swell. The depth or height to which the waves rise and fall is still a matter of speculation, some attributing it to six feet rise and six feet fall, and others again according to their own individual observation, or their ideas of the bounds of probability. I have heard many experienced practical seamen estimate it at thirty feet, nor does this appear to me in the least degree an exaggeration; but there is a remarkable difference, well known to sailors, between the waves when they are influenced by the shallowness of the water, and those in the fathomless ocean; the former rise abruptly, breaking at short intervals, while the summits of the latter, being quite unobstructed, are farther apart from each other, and no doubt rise considerably higher.

The river La Plata owes its name to the Spaniards, who transferred the produce of the silver mines of Chili and Peru on its waters to the ocean, and thence to Europe. The gold and silver were brought from those provinces across the Andes to Buenos Ayres, from whence

[page] 60

it was shipped; but the extension of discovery no sooner opened the passage round Cape Horn, than the river Plata lost its original importance. In point of magnitude it is the third river of the New World; at its mouth it is a hundred miles wide; at Monte Video it is fifty miles wide, this town being seventy miles up its stream, where the water is fresh and the tide overcome by its rapidity. At Buenos Ayres, situated one hundred and seventy miles from its mouth, the width of the river is twenty-five miles; above which it takes its rise in numerous streams, distant about one thousand five hundred miles in the lofty equatorial regions of Brazil. The navigation of the river is much impeded by shoals between Monte Video and Buenos Ayres; and the depth of the water is so little at this latter place, that a strong southwest wind, called in the country a pampero, is sufficient to lay the bed of it dry more than a mile from its southern bank, and the ships which may happen to be there, of course take the ground. The banks on each side are the termination of vast plains, on which no villages are to be seen to cheer and adorn the scene;

[page] 61

and nought is found to break the solitude, save herds of cattle that own no master's stall.