[page i]

THE

PALÆONTOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY.

INSTITUTED MDCCCXLVII.

MDCCLI.

[page ii]

[page iii]

A MONOGRAPH

ON THE

FOSSIL LEPADIDÆ,

OR,

PEDUNCULATED CIRRIPEDES OF GREAT BRITAIN.

BY

CHARLES DARWIN, F.R.S., F.G.S.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE PALÆONTOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY.

1851.

[page iv]

C. AND J. ADLARD, PRINTERS, BARTHOLOMEW CLOSE.

[page v]

PREFACE.

I HAVE great pleasure in returning my most sincere thanks to various naturalists, both for intrusting to me their collections of Fossil Cirripedia, and for allowing me, whenever it was advisable, to clear the specimens from their matrix. Although an entire stranger to many of the gentlemen to whom I applied, I have in every instance received the most courteous acquiescence to my demands. To Mr. Fitch, of Norwich, I here beg to return my thanks, for having allowed me to keep, during several months, his unrivalled collection of Cirripedia from the Upper Chalk of Norwich,—the fruit of twenty years' labour. Mr. Bowerbank has given me the freest use of his fine collection, rich in specimens from the Gault. Mr. Wetherell placed in my hands his beautiful and unique specimen of Loricula pulchella, and other species. Professor Buckman sent me, of his own accord, a fine series of the valves of Pollicipes ooliticus, the most ancient Cirripede as yet known, discovered and named by him. To Messrs. Flower, Searles Wood, F. Edwards, Harris, S. Woodward, Tennant, and other gentlemen, I owe the examination of several species new to me. Mr. Morris and Professor E. Forbes have, in their usual kind manner, supplied me with much valuable information, and with the loan of many specimens. To Mr. James de C. Sowerby I must express my thanks for the valuable aid rendered to me by the loan of the original specimens figured in the 'Mineral Conchology;' and for the pains exhibited in the drawings here published.

Professor Forchhammer, of Copenhagen, not only placed at my disposal many valuable specimens deposited in the Geological Museum of the University, but applied to Professor Steenstrup, who, in the most generous manner, sent me the collection in the Zoological department, including the highly valuable original specimens of his excellent Memoir on the Fossil Cirripedia of Denmark and Scania. Subsequently, Professor Steenstrup sent me a second large collection, the fruit of the indefatigable labours of M. Angelin, in

[page] vi PREFACE.

Scania: all these northern specimens have been of the greatest use to me in illustrating the British species. Having applied to Professor W. Dunker of Cassel, for some of the species described by various German authors, he not only sent me many specimens out of his own collection, but procured from Messrs. Roemer, Koch, and Philippi, other specimens of great value; and to these most distinguished naturalists I beg to return my very sincere thanks. Lastly, I may be permitted to state, that I hope very soon to have another and more appropriate opportunity of publicly expressing my gratitude to various gentlemen, who for many months together have left in my hands their large and valuable collections of recent Cirripedia, and who have assisted me in every possible way. I will here only state, that it was owing to the suggestion and encouragement of Mr. J. E. Gray, of the British Museum, that I was first induced to take up the systematic description of the Cirripedia, having originally intended only to study their anatomy. To all the foregoing gentlemen, I shall ever feel under the deepest obligations.

[page] 1

INTRODUCTION.

————————

THE CIRRIPEDIA, both recent and fossil, have been much neglected by systematic naturalists: the fossil species have, however, been more attended to than the recent. Professor Steenstrup has published1 an excellent monograph on the Danish and Scanian Cretaceous species: Mr. J. de Carle Sowerby has given good plates of several British valves in the Mineral Conchology; and F. Roemer2 has illustrated, by rather indifferent figures, though clear descriptions, various German forms. Other less important notices have appeared by several authors. As yet, however, no monograph has been produced on the whole group. The present volume is confined to the Lepadidæ or Pedunculated Cirripedia; and it so happens that the introduction, under the form of notes, of a few foreign species (which are necessary to illustrate the British species), serves to render this Monograph tolerably complete; that is, as far as the specimens collected on the Continent (judging from published accounts) serve for this end,—for we shall immediately see that certain valves are requisite in each genus.

It is unfortunate how rarely all the valves of the same species have been found coembedded; it is evident that, with the exception of some few species, the membrane which held the valves together, decayed very easily, as it does in recent Pedunculated Cirripedes. Hence, in the great majority of cases, the several valves have been found separate. Hitherto it has been the practice of naturalists to attach specific names indifferently to all the valves; and as in each species there are from three to five or six different kinds of valve, there would have been, had not the whole group been much neglected, so many names attached to each species. On the other hand, it has occurred in several instances, that many valves belonging to quite different species have been grouped together under the same name. To avoid these great evils, I have fixed on the most characteristic valves, one in each of the two main genera, and taking them as

1 Naturhistorisk Tidsskrift, af H. Kröyer, 1837 and 1839.

2 Die Versteinerungen des Norddeutschen Kreidegebirges, 1841.

a

[page] 2 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

typical, have never, except in one instance where several valves were known all to belong to the same individual, and in another instance in which a valve was very remarkable, attached a specific name to any other one. I have, however, in two cases retained names already given to certain other valves, as they presented remarkable characters, and were almost certainly distinct. In Scalpellum I have taken the Carina or Keel-valve (i. e. dorsal valve of most authors) as typical; and in Pollicipes, the Scuta (i. e. the inferior lateral valves of most authors): it would have been desirable to have taken the same valve in both genera; but it so happened that the Carina has been much more frequently collected than any other valve in Scalpellum, in which genus it is highly characteristic; whereas in Pollicipes, it is apt to present less striking characters than the Scuta, which are, moreover, commoner in most collections. In almost all the Lepadidæ the Terga (i. e. the upper or posterior lateral valves) are not characteristic, and are particularly liable to variation. Although only certain valves in each genus thus receive specific names, yet from the conditions of embedment, several of the other valves can often be safely attributed to the same species.

Much confusion in nomenclature will, I think, be avoided by the plan here adopted; but the study of Fossil Cirripedia must, I fear, owing to the variability of the valves, as seen in some fossil species, and as inferred from what so commonly occurs with recent species, ever remain difficult. In very many of those recent species, of which large series have passed through my hands, several of the valves have varied so much, that had I seen only certain specimens from the opposite poles of the series, I should unhesitatingly have ranked them as quite distinct species: on the other hand there are some recent forms—for instance, some species of Lepas, and again Pollicipes cornucopia, and elegans of Lesson—which are perfectly distinct, but which it would be hopeless to attempt discriminating when fossilized, without quite perfect specimens. It should be borne in mind, that the recognition of the Fossil Pedunculated Cirripedes by the whole of their valves and peduncle, is identical with recognising a Crustacean by its carapace, without the organs of sense, the mouth, the legs, or abdomen: to name a Cirripede by a single valve is equivalent to doing this in a Crustacean by a single definite portion of the carapace, without the great advantage of its having received the impress of the viscera of the included animal's body: knowing this, and yet often having the power to identify with ease and certainty a Cirripede by one of its valves, or even by a fragment of a valve, adds one more to the many known proofs of the exhaustless fertility of Nature in the production of diversified yet constant forms.

I must allude to one more unfortunate cause of doubt in the classification of the extinct Lepadidæ, namely, the difficulty in attributing the separated valves to the two main genera of Scalpellum and Pollicipes; for the chief distinction between these two close genera in the recent state, lies in the number of the valves, and this can very rarely be ascertained in fossil specimens. At first I determined to follow those authors who have united both genera under Pollicipes; but reflecting that I had twelve recent and

[page] 3 INTRODUCTION.

above thirty-seven fossil species, with almost the certainty—as we shall presently see—of very many more being discovered, this plan seemed to me too inconvenient to be followed. There are six recent species which I intend, in a future work, to include under Scalpellum. Four of them have been raised by Dr. Leach and Mr. Gray to the rank of genera; two other unnamed species have certainly equal, if not stronger, claims to the same rank; so again the six recent species of Pollicipes have similar claims to be divided into three genera, thus making nine genera for the twelve recent species of Scalpellum and Pollicipes. In the majority of cases it would be eminently difficult to allocate the fossil species in these nine genera; nevertheless, taking the characters necessarily used for the generic divisions of all the other recent Pedunculated Cirripedes, there can be no doubt that the formation of the above nine genera might be justified, that is, if we are allowed to neglect mere classificatory utility as an element in the decision, and further, if we are invariably bound to make as far as possible all genera of exactly the same value. As far as utility in classification is concerned, it appears to me clear that the institution of so many genera, until many more species are discovered, is highly disadvantageous: with respect to making all genera of exactly equal value, this, though eminently desirable, appears to me almost hopeless; I know not how to weigh the value of slight differences in different valves; or whether a difference in the maxillæ or mandibles be the more important: anyhow, in this particular case, if we raised the six recent species of Scalpellum into six genera, they assuredly would not be distinct to an exactly equal degree. Under these circumstances I have followed a middle term, and kept Scalpellum and Pollicipes distinct,—genera easy to be recognised in a recent state,—which renders the classification of the fossil species, though always difficult and liable to many errors, somewhat easier than if both genera were united into one, and much easier than if the above nine genera were admitted.

APTYCHUS.

Before passing to more general considerations, I must offer a few remarks on the genus Aptychus, or Trigonellites, inasmuch as quite lately a distinguished naturalist, M. D'Orbigny,1 has adopted, and with much ingenuity supported, the view that these anomalous bodies are Pedunculated Cirripedia. It cannot be denied that the general form and lines of growth closely resemble those of the Scuta or lateral inferior valves in Lepas or Anatifa: nor can it be denied, from what we know of recent species, that the Terga (upper lateral valves) and Carina (dorsal valve), which on M. D'Orbigny's view must be considered as absent, are the most likely valves to disappear from abortion. But there are points of difference which, as it appears to me, are of far greater importance than the

1 Cours Élémentaire de Paléontologie, 1849, vol. i, p. 254.

[page] 4 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

resemblance in mere outline. The peculiar cancellated structure, which is almost visible on the external surface even to the naked eye, is wholly unlike anything known amongst Cirripedia; a thin polished slice of the valves of Lepas and of Aptychus, viewed under a high power, are as unlike as anything can well be.1 In Aptychus the lines of growth are conspicuous on the inner or concave surface, and indistinguishable or not plain on the outer surface; whereas in Lepas exactly the reverse holds good. Again, in some specimens it appears, that additions are made to the shell on the exterior edge of the growing margin, instead of on the inner edge, as in Cirripedia. In Aptychus latus, there is a rather deep internal fold along the whole of that margin, through which the cirri are supposed to have been protruded, and this is unlike anything which I have met with in Cirripedes. In all the species of Aptychus, the two valves are much the most frequently, though not invariably, found widely opened, and attached together, either exactly or nearly so, by the two margins through which the cirri must have been protruded. Now in all true fossil pedunculated Cirripedes, the valves are found either separate, which is the commonest case, or when held together, those on the opposite sides almost exactly cover each other, for there is nothing in the structure of Cirripedia tending to open the valves like the ligament in bivalve shells. How comes it, then, that the specimens of Aptychus, even those found within the protected chambers of Ammonites, thus generally have their valves widely gaping? Even if we pass over this difficulty, is it not strange that the valves should always have been held together by that margin, which in the recent condition is supposed to have been open for a considerable portion of its length, for the exsertion of the cirri; whereas, in not one single instance, as far as I have seen, are the two valves held together by the opposite margin, which in the recent state, on the idea of Aptychus having been a Cirripede, must have been continuously united by membrane.

There is another argument against Aptychus having been a Cirripede, which will have weight, perhaps, with only a few persons: in Pollicipes, the main growth of all the valves is downwards; in Lepas or Anatifa, as well as in most of the allied genera, the main growth of the Scuta and of the Carina (i. e. lower lateral, and dorsal, or valves,) is in a directly reversed direction, or upwards. Now Pollicipes is the oldest known genus of Cirripedes, having been found in the Lower Oolite, whereas hitherto Lepas is not certainly known to have been discovered even in the newest Tertiary formation. So again within the limits of the genus Scalpellum, I know of only two cretaceous species in which the Scuta grow upwards and downwards, and only one case in which the Carina has this double direction of growth; whereas in the recent and one Miocene species, these valves usually grow both upwards and downwards. Hence it would appear that there is some relation between the age of fossil Lepadidæ and the upward or downward direction of

1 When I had the slices made, I did not know of H. von Meyer's paper on Aptychus, in the 'Acta Acad. Cæs. Leop. Car.,' vol. xv, Oct. 1829, tab. lviii and lix, fig. 13, in which perfectly accurate sections are given of the microscopical structure of Aptychus lævis.

[page] 5 INTRODUCTION.

the lines of growth in their valves. Aptychus, according to M. D'Orbigny, existed during the Carboniferous system, at a period vastly anterior to the oldest known Pollicipes, yet on the idea of its having been a Cirripede, the growth of its valves (Scuta) must have been upwards, as in the most recent forms; and it was allied to Lepas, that genus which, in the order of creation, and in the manner of growth, stands at the opposite end of the series from Pollicipes. From the several reasons now given, it does not appear to me that Aptychus, until weightier evidence is adduced, can be safely admitted as a Cirripede.

Geological History.— No true Sessile Cirripede1 has hitherto been found in any Secondary formation; considering that at the present time many species are attached to oceanic floating objects, that many others live in deep water in congregated masses, that their shells are not subject to decay, and that they are not likely to be overlooked when fossilized, this seems one of the cases in which negative evidence is of considerable value. Mr. Samuel Stuchbury, moreover, (to whom I am deeply indebted for much information, and the loan of his beautiful collection of recent species,) has assured me that vast numbers of fossil secondary corals have passed through his hands, and that he has carefully looked without success for those genera which commonly inhabit living corals. Sessile Cirripedes are first found in Eocene deposits, and subsequently, often in abundance, in the later Tertiary formations. These Cirripedes now abound so under every zone, all over the world, that the present period will hereafter apparently have as good a claim to be called the age of Cirripedes, as the Palæozoic period has to be called the age of Trilobites. There is one apparent exception to the rule that Sessile Cirripedes are not found in Secondary formations, for I am enabled to announce that Mr. J. de C. Sowerby has in his collection a Verruca (= Clysia, Clytia, Creusia, Ochthosia) from our English chalk: but this genus, though hitherto included amongst the Sessile Cirripedes, must, when its whole organisation is taken into consideration, be ranked in a distinct family of equal value with the Balanidæ and Lepadidæ, but perhaps more nearly related to the latter than to the Sessile Cirripedes. Hence the presence of Verruca in the Chalk is no real exception to the rule that Sessile Cirripedes do not occur in Secondary formations; on the contrary, it harmonises with the law, that there is some relation between serial affinities of animals, and their first appearance on this earth.

The oldest known pedunculated Cirripede is a Pollicipes, discovered by Professor Buckman in the Stonesfield Slate in the Lower Oolite: two species of the same genus have been described by Mr. Morris from the Oxford Clay, in the middle Oolite. I have

1 Dr. Petzholdt has described and figured (Jahrbuch, 1842, p. 403, tab. x), a Balanus carbonaria from the carboniferous system; but as neither the operculum, the structure of the shell, the number of the valves, nor their manner of growth, can be made out or are described, the evidence appears quite insufficient to admit the existence of this genus at so immensely a remote epoch. Bronn, in the 'Index Palæontologicus,' gives, under Tubicinella, a cretaceous species; I have unfortunately not been able to consult the original work cited.

[page] 6 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

not heard of any Cirripede having been as yet discovered in the Upper Oolite, or in the Wealden formation. During the deposition of the great Cretaceous System, the Lepadidæ arrived at their culminant point; there were then three genera, and at least thirty-two species, some occurring in every stage of this system. Besides the thirty-two certainly known cretaceous forms, and several other doubtful ones, I believe that very many more will yet be discovered; I infer this from the fact, that in almost every collection lent to me for examination, although very small, I have found some new species. I have three or four species from the Gault; from five to eight in the Lower Chalk, and from nine to twelve species in the Upper Chalk (not including the Faxoe, Scanian, and Maëstricht stage); and of these nine to twelve species, five have been found by one collector, Mr. Fitch, in one locality, namely near Norwich. In Scania M. Angelin has found no less than nine or ten species, all belonging to the upper or Maëstricht stage of the Chalk. These fossils, judging from the habits of recent species of the same genera, were probably attached to fixed, or nearly fixed, objects at the bottom of the sea. Now at the present day, of attached Pedunculata (reckoning even Crustacea and Echinidæ as fixed objects), the whole Mediterranean and New Zealand can boast each only of three species, in both cases including Alepas, which is destitute of calcified valves and therefore not likely to be fossilized; Australia has three species; Madeira has four species, including one with very small and imperfectly calcified valves; the great Phillipine Archipelago, however, has afforded, owing to the labours of Mr. Cuming, as many as five species, though including one with horny valves, and a Lithotrya which lives embedded on the beach. Therefore since we already have nine or ten fossil species from one locality, and from the same stage of the chalk, we may admit that the pedunculated Cirripedes arrived during the upper part of the Cretaceous system at their culminant point.

Although, for this family, the number of species were considerable during the Cretaceous period, the individuals were mostly rare. I infer this from the small number of specimens in all collections; for instance, Mr. Fitch, who has assiduously collected for twenty years in the chalk near Norwich, possesses in his entire collection only nine keel-valves of Scalpellum maximum, and six of S. fossula; he has two Scuta (and with regard to these valves, it must be remembered, that each individual had two) of Pollicipes striatus, two of P. fallax, and four of P. Angelini. This occasional want of a relation, within the same region, between the number of the species in any given genus, and of the individuals appertaining to such species, is a singular fact, and has been strongly insisted on by Dr. Hooker, in regard to the Coniferous trees of the southern hemisphere: one would naturally have expected, that where circumstances favoured the existence of numerous species of a genus, they would likewise have favoured the multiplication of the individuals in all or most of such species; but this, as we here see, has not always been the case.

In the Eocene, Miocene, and Pliocene Tertiary deposits, I know only of two species of Scalpellum, and two of Pollicipes, with indications of two or three other species, all distinct

[page] 7 INTRODUCTION.

from recent forms. It is a rather singular fact, considering the present wide distribution of the genus Lepas or Anatifa, and the frequency of the individuals, that not a single valve known certainly1 to belong to this genus, or to any of the closely-allied genera, has hitherto been found fossil.

The oldest known cirripede is, as we have seen, a Pollicipes from the lower Oolite, and it does not differ conspicuously from some of the recent species of the same genus; so, again, the cretaceous Scalpellum fossula, and the eocene S. quadratum are certainly very nearly related to the recent S. rutilum (nov. spec.). Loricula alone is a genus perfectly distinct from all living Cirripedia; and I may here add that of the Tertiary Sessile Cirripedes, I have hitherto not seen a single new generic form. This persistence of the same genera is somewhat remarkable, considering that amongst ordinary Crustacea nearly all the Secondary species belong to extinct genera;2 it should, however, be borne in mind that Limulus has survived from the Palæozoic period to the present day. The Oolitic, Cretaceous, Tertiary, and recent species of Lepadidæ are all different from each other. By looking at the annexed Table, and putting out of question the species of which the age is uncertain, we have five common to two stages of the chalk; that is assuming for the present that the classification of the stages of the chalk commonly used and here followed, is correct. Pollicipes glaber is common to three, and, I believe, to four stages. Scalpellum arcuatum occurs in the Chalk-marl, and upper Greensand, and therefore this species also extends through three stages; but there is a slight difference between the specimens from the upper and lower stages, which some authors might perhaps consider specific. If fossil cirripedia had, like most recent species, very wide horizontal or geographical ranges, then, in accordance with a law now generally admitted, a considerable vertical range in some of the species is not improbable.

I may here observe that I am assured by Professors Forchammer and Steenstrup, that the formations of Scania and Westphalia are equivalent to that of Faxoe; and hence to that of Maëstricht. I have called these formations the " Maestricht formation," to distinguish them from the common upper or white Chalk.

1 In a mere catalogue, published without descriptions, in the 'Jahrbuch' for 1831, p. 155, by Hoenninghaus, Anatifa cancellata is given as a tertiary species: Mr. G. B. Sowerby has stated, in his ' Genera of Shells,' that he has seen a Tertiary specimen of this genus, but he cannot remember which valve it was.

2 Pictet, Traité Élémentaire de Paléontologie, tom. iv. p. 4.

[page] 8 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

TABLE OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE SPECIES.

|

Tertiary. |

Faxoe, Scania, Maëstricht. |

Upper Chalk. |

Lower Chalk. |

Chalk Marl. |

Upper Greensand. |

Gault. |

Lower Greensand. |

Middle Oolite. |

Lower Oolite. |

|

| Scalpellum magnum... |

* |

|||||||||

| — quadratum.. | * |

|||||||||

| — fossula.... | — | — | * |

|||||||

| — maximum... | — | * |

* |

|||||||

| — lineatum... | — | — | — | * |

||||||

| — hastatum... | — | — | — | — | * |

|||||

| — angustum... | — | — | *? | *? | *? | |||||

| — quadricarinatum. | — | — | — | — | * |

|||||

| — triliniatum.. | — | — | — | — | * |

|||||

| — simplex... | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

||

| — arcuatum... | — | — | — | — | * |

— | * |

|||

| — tuberculatum.. | — | — | *? | *? | *? | |||||

| — solidulum ... | — | * |

||||||||

| — semiporcatum. | — | * |

||||||||

| — (?) cretæ.... | — | — | * |

|||||||

| Pollicipes concinnus... |

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

|

| — ooliticus... | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

| — Nilssonii... | — | * |

||||||||

| — Hausmanni.. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

||

| — politus .... | — | — | — | — | — | — | *? |

|||

| — elongatus... | — | — | * |

|||||||

| — acuminatus.. | — | — | — | * |

||||||

| — Angelini... | — | * |

* |

|||||||

| — reflexus... | * |

|||||||||

| — carinatus... | * |

|||||||||

| — glaber.... | — | *? |

* |

* |

* |

|||||

| — unguis.... | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

* |

||

| — validus.... | — | * |

||||||||

| — gracilis.... | — | — | * |

* |

||||||

| — dorsatus... | — | * |

||||||||

| — striatus.... | — | — | * |

|||||||

| — semilatus... | — | — | *? |

*? |

*? |

|||||

| — rigidus.... | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

|||

| — fallax.... | — | * |

* |

|||||||

| — elegans.... | — | * |

||||||||

| — Bronnii.... | — | — | — | — | — | * |

||||

| — planulatus... | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | * |

|

| Loricula pulchella.... | — | — | — | * |

||||||

| ———————————————————————————————————————————— | ||||||||||

| Total 38.... |

4 |

9—10 |

9—12 |

5—8 |

5—8 |

1 |

3—4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

[page] 9 INTRODUCTION.

NOMENCLATURE OF THE VALVES.

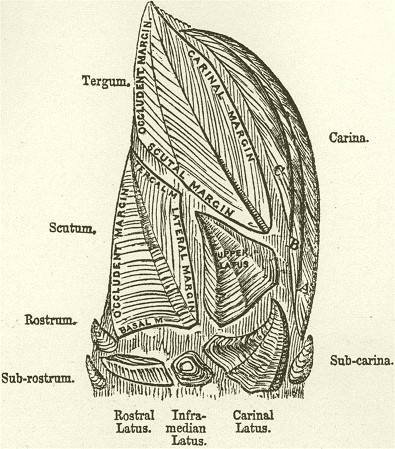

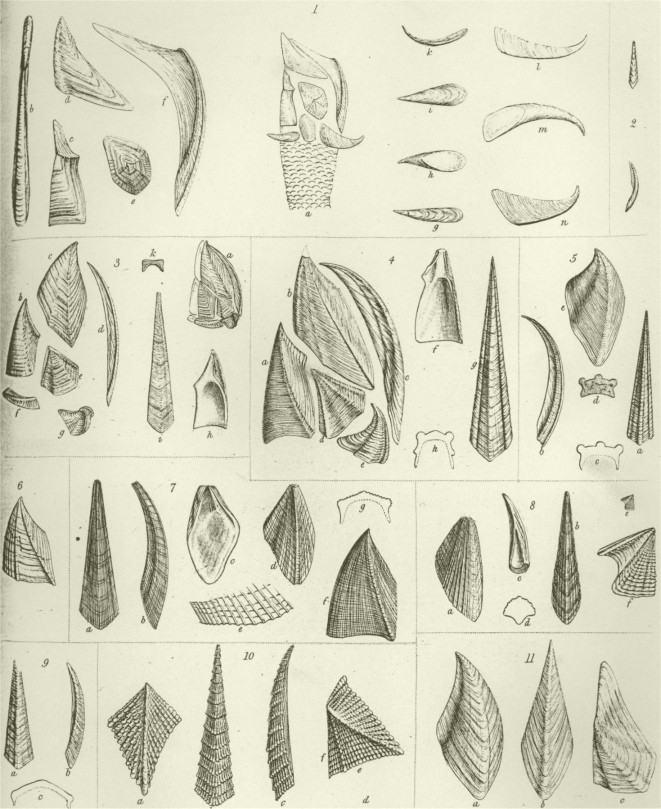

Figure I.

CAPITULUM.

PEDUNCLE.

————————

N.B.—In the Carina of Scalpellum, A is the tectum; B the parietes; C the intra-parietes.

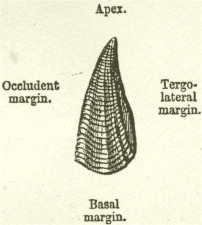

Figure II.

Scutum of POLLICIPES.

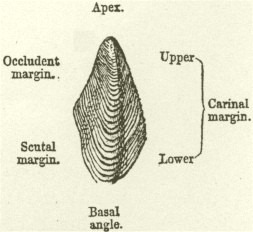

Figure III.

Tergum of POLLICIPES.

Whoever will refer to the published descriptions of recent and fossil Cirripedia, will find the utmost confusion in the names given to the several valves; thus, the valve named in the above woodcut, the Scutum, has been designated by various well-known naturalists as the " ventral," the " anterior," the " inferior," the " ante-lateral," and the " latero-inferior" valve; the first two of these titles have, moreover, been applied to the rostrum or rostral valve of Sessile Cirripedes. The Tergum has been called the " dorsal," the " posterior," the " superior," the " central," the " terminal," the " postero-lateral," and the " latero-superior" valve. The Carina has received the first two of these identical epithets, viz. the " dorsal" and the " posterior;" and likewise has been called the " keel-valve." The confusion, however, becomes far worse, when any individual valve is described, for the very same margin which is anterior or inferior in the eyes of one author, is the posterior or superior in those of another; it has often happened to me that I have been quite unable even to conjecture to which margin or part of a valve an author was referring. Moreover, the length of these double titles is inconvenient.

Hence, as I intend to describe all the recent and fossil species, I have thought myself

b

[page] 10 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

justified in giving short names to each of the more important valves, these being common to the Pedunculated and Sessile Cirripedes.

The title of peduncle, which is either naked or squamiferous, requires no explanation; the scales and lower valves are arranged in whorls, which I have called by the botanical term of Verticillus. The part supported by the peduncle, and which is generally, though not always, in recent species protected by valves, I have designated the Capitulum.

I have applied the term Scutum to the most important and persistent of the valves, and which can almost always be recognised by the hollow giving attachment to the adductor scutorum muscle, from the resemblance which the two valves taken together bear to a shield, and from their office of protecting the front side of the body. From the protection afforded by the two Terga to the dorso-lateral surface of the animal, these valves have been thus called. The term Carina is a mere translation of the name already used by some authors, of Keel-Valve: in the genus Scalpellum, in which this valve is taken as typical, I have found it quite necessary, with fossil specimens, to distinguish the roof (see Woodcut, I,) or exterior surface, as the tectum (A); the inflected sides, as the parietes (B); and in several species in the upper half of the valve, the intra-parietes (C): the expressions of apex, basal margin, and inner margin, as applied to the Carina, require no explanation. The rostrum has been so called from its relative position to the Carina or keel. There is often a sub-carina and a sub-rostrum.

The remaining valves have been called Latera; there is always one large upper one inserted between the lower halves of the Scuta and Terga, and this I have named the Upper Latus or Latera; the other Latera in Pollicipes are numerous, and require no special names; in Scalpellum, where there are at most only three pair beneath the Upper Latera, it is convenient to speak of them (vide Woodcut, I,) as the Carinal, Infra-median, and Rostral Latera.

As each valve, especially amongst the fossil species, requires a distinct description, I have found it indispensable to give names to each margin. These have mostly been taken from the name of the adjoining valve, (See Woodcut, I.) In Pollicipes the margin of the Scutum adjoining the Tergum and Upper Latus, is not divided (Woodcut, II,) into two distinct lines, as in Scalpellum, and is therefore called the tergo-lateral margin; a narrow portion or slip along this side of the valve may be seen (Woodcut, II,) to be formed of upturned lines of growth; this is often of service in classification, and I have called it the tergo-lateral slip or segmentum tergo-laterale. In Scalpellum (Woodcut, I,) these two margins are separately named Tergal and Lateral. The angle formed by the meeting of the basal and lateral or tergo-lateral margins, I call the baso-lateral angle; that formed by the basal and occludent margins, I call, from its closeness to the Rostrum, the rostral angle. In Pollicipes the Carinal margin of the Tergum (Woodcut, III,) can be divided into an upper and lower carinal margin.

That margin in the Scuta and Terga which opens and shuts for the exsertion and retraction of the cirri, I have called the Occludent margin.

[page] 11 INTRODUCTION.

During the periodical growth of the valves, especially when they are thick and massive, it happens in several species that the underlying corium deserts their upper ends or umbones, which consequently become marked by lines or ridges of growth, as I have called them, though perhaps lines of recession would have been more strictly correct. Such valves, consequently, have their upper ends projecting from and beyond the capitulum, and are said to project freely or liberè; this is often more especially the case with the Carina in Pollicipes, and in a lesser degree with the Terga.

From the peculiar curved position which the animal's body occupies within the capitulum, I have found it far more convenient (not to mention the confusion of nomenclature already existing) to apply the term Rostral instead of ventral, and Carinal instead of dorsal, to almost all the external and internal parts of the animal. Cirripedes have generally been figured with their surfaces of attachment downwards, hence I have termed the lower margins and angles the Basal, and those pointing in an opposite direction the Upper; strictly speaking, the exact centre of the usually broad and flat surface of attachment is the anterior end of the animal, and the upper tips of the Terga, the posterior end of that part of the animal which is externally visible; but in some cases, for instance in Coronula, where the base is deeply concave, and where the width of the shell far exceeds the depth, it seemed almost ridiculous to call this, the anterior extremity; as likewise does it in Balanus to call the united tips of the Terga, lying deeply within the shell, the most posterior point of the animal as seen externally.

[page 12]

CLASS—CRUSTACEA. SUB-CLASS—CIRRIPEDIA.

Family—LEPADIDÆ.

Cirripedia pedunculo flexili, musculis instructo: Scutis1 musculo adductore solummodô instructis: valvis cæteris, siquæ adsunt, in annulum immobilem haud conjunctis.

Cirripedia having a peduncle, flexible, and provided with muscles. Scuta1 furnished only with an adductor muscle: other valves, when present, not united into an immovable ring.

Besides the brief characters here given others might have been added, drawn from the softer parts of the animals, but as this Volume treats only of Fossil species, they would have been in this place superfluous. Nor have I thought it advisable to give here any definition of the Sub-class Cirripedia, or of the Order which contains both the Lepadidæ and Balanidæ, that is the Pedunculated and Sessile Cirripedes; for the characters would likewise have had to be derived almost entirely from the softer parts of the animal. It may, however, be worth stating, that by following the metamorphoses of the Cirripedia, it can be clearly shown that the capitulum together with the peduncle, in the Pedunculated Cirripedes, and that the shell together with the operculum in the Sessile Cirripedes, that is the whole of what is externally visible, consists simply of the first three segments of the head. In many Crustacea the carapace, formed by the backward production of the three anterior rings of the head, covers the dorsal surface of the thorax, and in some it encloses the limbs and mouth. This is likewise the case with the Cirripedia, and it is only the wonderful elongation of the anterior part of the head, its fixed condition, and the absence of external eyes and antennæ, which gives to the Cirripedia their peculiar character, and has hitherto prevented the homologies of these parts from having been recognised.2

1 The meaning of this and all other terms is given in the Introduction at page 9.

2 Nevertheless, in some Stomapoda, more especially in Leucifer of Vaughan Thompson, the anterior part of the head is only a little less elongated, compared with the rest of the body, than in the Cirripedia. That accomplished naturalist, M. J. D. Dana (Silliman's 'American Journal,' March, 1846,) has stated that " the pedicel of Anatifa corresponds to a pair of antennæ in the young:" although the peduncle or pedicel is undoubtedly thus terminated, this view cannot, I think, be admitted. In the larva, the part anterior to the mouth is as large, in proportion to the rest of the body, as in some mature Cirripedia: this anterior part supports only the eyes, antennæ, and two small cavities furnished with large nerves, which I

[page] 13 SCALPELLUM.

I may further state, that in the several Orders of Cirripedia such important differences of structure are presented, that there is scarcely more than one great character by which all Cirripedia may be distinguished from other Crustacea: this character is, that they are attached to some foreign object by a tissue or secretion (for at present I hardly know which to call it), which debouches, in the first instance, through the prehensile antennæ of the larva, the antennæ being thus embedded and preserved in the centre of the basis. The cementing substance is brought to its point of debouchement by a duct, leading from a gland, which (and this is perhaps the most remarkable point in the natural history of the Class) is part of and continuous with the branching ovaria. When we look at a Cirripede, we, in fact, see only a Crustacean, with the first three segments of its head much developed and enclosing the rest of the body, and with the anterior end of this metamorphosed head fixed by a most peculiar substance, homologically connected with the generative system, to a rock or other surface of attachment.

Genus—SCALPELLUM.

SCALPELLUM. Leach. Journ. de Physique, t. lxxxv, July, 1817.

LEPAS. Linn. Systema Naturæ, 1767.

POLLICIPES. Lamarck. Animaux sans Vertebres.

POLYLEPAS. De Blainville. Dict. des Sc. Nat., 1824.

SMILIUM (pars generis). Leach. Zoolog. Journal, Vol. 2, July, 1825.

CALANTICA (pars generis). J. E. Gray. Annals of Philosophy, vol. x, (2d series,) Aug. 1825.

THALIELLA (pars generis). J. E. Gray. Proc. Zoolog. Soc., 1848.

ANATIFA. Quoy et Gaimard, Voyage de l'Astrolabe, 1826-34.

XIPHIDIUM (pars generis). Dixon. Geology of Suffolk, 1850.

Valvis 12 ad 15: Lateribus verticelli inferioris quatuor val sex, lineis incrementi plerumque convergentibus; Subrostrum rarissime adest: Pedunculo squamifero, rarissime nudo.

suspect to be auditory organs; this part, therefore, I think, must unquestionably consist of the first two or three segments of the head: within it, even before the larva moults, the incipient striæless muscles and ovaria of the peduncle can be distinctly traced: immediately after the moult, we see this anterior part converted into a perfect peduncle; and for some time afterwards certain coloured marks, indicating the former position of the (so called) olfactory cavities and of the cast-off compound eyes, are still preserved. The prehensile antennæ are not cast off, for they are fastened down by the cementing substance, and are thus preserved in a functionless condition, with their muscles absorbed; after a time even the corium is withdrawn from within them. From the above and other coloured marks, and from the antennæ being preserved, it is easy to point out, in the peduncle of a young though perfect Lepas, the exact point which each part occupied in the head of the natatory larva.

Since the above was written, I find that Lovén has taken the same view of the homologies of the external parts of the Cirripedia: in his description of his Alepas squalicola, (Ofversigt of Kongl. Vetens., &c., Stockholm, 1844, pp. 192-4,) he uses the following words: " Capitis reliquæ partes, ut in Lepadibus semper, in pedunculum mutatæ et involucrum," &c.; his involucrum is the same as the Capitulum of this work.

[page] 14 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

CHARACTERES VALVARUM IN SPECIEBUS FOSSILIBUS.

Carina angusta, introrsùm arcuata, ab apice ad marginem basalem paululum dilatata; parietes valde inflexi, costis manifestis a tecto plerumque disjuncti; in multis speciebus intra-parietibus instructi: intra-parietes nonnumquam supernè producti ultra Umbonem, qui fit inde subcentralis: parietum lineæ incrementi perobliquæ. Scuta plerumque subconvexa et tenuia, trapezoidea; marginibus tergalibus lateralibusque angulo insigni disjunctis.

Sect. †. Subcarina adest (solummodò species recentes).

Sect. ††. Subcarina deest.

A. Valvæ quatuordecim: Carinæ umbone subcentrali.

B. Valvæ duodecim: Carinæ umbone ad apicem posito.

Valves 12 to 15 in number. Latera of the lower whorl, four or six, with their lines of growth generally directed towards each other. Sub-rostrum1 very rarely present. Peduncle squamiferous, most rarely naked.

CHARACTERS OF THE VALVES IN FOSSIL SPECIES.

Carina narrow, bowed inwards, widening but little from the apex to the basal margin, having parietes much inflected, and generally separated by distinct ridges from the tectum, and having in many species intra-parietes, which are sometimes produced upwards beyond the umbo, so as to make it sub-central; lines of growth on the parietes very oblique. Scuta generally only slightly convex and thin, four-sided, the tergal and lateral margins distinctly separated by an angle.

Sect. †. Subcarina present. (This section includes only recent species.)

Sect. ††. Subcarina absent.

A. Valves fourteen in number; Carina with the umbo subcentral.

B. Valves twelve; Carina with the umbo at the apex.

The first of the above two paragraphs contains the true Generic description (here leaving out the softer parts), as applicable to recent and, as far as known, to fossil species: the second paragraph has been drawn up to aid any one in classifying the characteristic valves, when found separated, as is most frequently the case with all fossil Pedunculata. The first or proper Generic characters would have been more precise, had it not been for the existence of one recent species, the S. villosum (Pollicipes villosus, Leach, Calentica Homii, J. E. Gray,) which leads into the next genus Pollicipes. I mention this species in order to confess, that had the valves been found separately, and their number unknown, they would certainly have been included by me under Pollicipes, although, taking the whole organisation into consideration, I have determined to include this species under Scalpellum. I need not

1 The meaning of this and all other special terms is given in the Introduction at p. 9.

[page] 15 SCALPELLUM.

here repeat the remarks made in the Introduction on the great difficulties in classifying the recent species, and still more the fossil species of Scalpellum. I may, however, here state that should the S. vulgare be hereafter kept distinct in a genus to itself, S. magnum would have to go with it. Should a recent species, which in a future work I shall describe under the name of S. rutilum, be generically separated, it will probably have to bear the name of Xiphidium, from its alliance to the Eocene X. quadratum of Sowerby, to which species the cretaceous S. fossula and several other forms are apparently closely allied. These latter species, however, are likewise closely allied to the Scalpellum ornatum, which Mr. Gray has already raised to the rank of a genus under the name of Thaliella. There are some fossil species, as S. arcuatum, and simplex and solidulum, which I cannot rank particularly near any recent forms. Mr. Sowerby founded the genus Xiphidium on the umbo in the Carina being situated at the apex, and on its growth being consequently exclusively downwards. This is likewise the case with the recent S. rutilum; but I shall have occasion to show, under S. magnum, that the upward growth of the Carina in that and other species of the genus, depends merely on the intra-parietes, which are present in many species, meeting each other and being thus produced upwards. Moreover, in the recent S. ornatum, the position of the umbo is variable, according to the age of the specimen; in half-grown individuals being seated at the apex, and in large specimens being sub-central, as in S. vulgare, magnum, and other species. I should have been very glad to have retained the genus Xiphidium, but taking into consideration the whole organisation of the six recent species, I can only repeat that we must either make six genera of them, or leave them altogether, and this latter has appeared to me the most advisable course.

Sexual Peculiarities.—For reasons stated in the Introduction, I have kept the genera Scalpellum and Pollicipes distinct; but I may mention, in order to call attention to a point of structure which may hereafter be discovered in some fossil species, that I was much influenced in this decision by some truly extraordinary sexual peculiarities in all six recent species of Scalpellum. Scalpellum ornatum is bisexual; the individual forming the ordinary shell, is female; each female has two males (a case of Diandria monogynia), which are lodged in small transverse depressions, one on each side, hollowed out, on the inner sides of the Scuta, close above the slight depressions for the adductor scutorum muscle; in S. rutilum (nov. spec.) two males are lodged in the same place on each side, but rather in concavities in the valve, than in distinct depressions. As these are the two recent species most nearly related to several Cretaceous and Eocene forms, we might expect to find similar depressions in some fossil species; but as yet I have not succeeded in distinctly finding such. The male cirripedes are very singular bodies; they are minute, of the same size as the full-grown larva; they are sack-formed, with four bead-like rudimental valves at their upper ends; they have a conspicuous internal eye; they are absolutely destitute of a mouth, or stomach, or anus: the cirri are rudimental and furnished

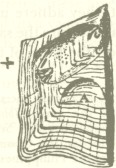

Inside view of the scutum in Scalpellum ornatum. (A) is the depression for the adductor muscle.

[page] 16 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

with straight spines, serving, apparently, to protect the entrance of the sack: the whole animal is attached, like ordinary cirripedes, first by the prehensile antennæ, and afterwards by the cementing substance; the whole animal may be said to consist of one great sperm-receptacle, charged with spermatazoa; as soon as these are discharged, the animal dies.

A far more singular fact remains to be told: Scalpellum vulgare is like ordinary cirripedes, hermaphrodite, but the male organs are somewhat less developed than is usual; and, as if in compensation, several short-lived males are almost invariably attached on the occludent margin of both Scuta, at a spot marked by a fold (not thus caused), as may be seen on the inside view of this valve in the fossil S. magnum, which, in all probability, was furnished with them. I have called these beings complemental males, to signify that they are complemental to an hermaphrodite, and that they do not pair like ordinary males with simple females. In Scalpellum vulgare, the complemental male presents only slight specific differences from the male of S. ornatum. It would be foreign to the purpose of this volume here to enter on further details; nor should I have touched on the subject, had I not wished specially to call attention to the presence of cavities on the under sides of the Scuta above the pits for the adductor muscle. I will only add, that in the other species of Scalpellum, the complemental males are more highly organised, and are furnished with a mouth and prehensile cirri; the valves are more or less rudimental in the different species; these complemental males are not always present, and are never attached to young hermaphrodites; when present, they adhere in such a position, that they can discharge their spermatozoa into the sack of the hermaphrodite: their attachment does not affect the form of the valves.1

Description of Valves.—It will, I think, be most convenient to confine the following description to the fossil species of the genus. No one specimen has been found quite perfect; but, judging from analogy, the capitulum was probably formed of fourteen valves in S. magnum, and of twelve in the remaining species. These valves are commonly smooth,

1 Exactly analogous facts are presented, though more conspicuously, by the two species of the genus Ibla. Before examining this genus, I had noticed the complemental males on Scalpellum vulgare, but had not imagined even that they were Cirripedia. Ibla Cumingii (as I propose to call a new species collected by Mr. Cuming, at the Philippines) is bisexual; one or two males being parasitic near the bottom of the sack of the female. These males are small, are supported on a long peduncle, but are not enclosed in a capitulum (such protection being here unnecessary), are furnished with a mouth, ordinary trophi, stomach, and anus: there are only two pair of cirri, and these are distorted, useless and rudimentary; the whole thorax is extremely small; there is no penis, but a mere orifice beneath the anus for the emission of semen; hence Ibla Cumingii is exactly analogous to Scalpellum ornatum. On the other hand, the closely allied Australian Ibla Cuvierii, like Scalpellum vulgare, is hermaphrodite, but has, in every specimen opened by me, a complemental male attached to near the bottom of the sack; this complemental male differs only about as much from the male of Ibla Cumingii, as the female J. Cumingii differs from the hermaphrodite form of I. Cuvierii. I intend hereafter to give detailed anatomical descriptions and drawings of the males and complemental males of Ibla and Scalpellum.

[page] 17 SCALPELLUM.

but in two or three species are marked with longitudinal ridges; they are generally rather thin; this, however, is a character which is variable even in the same species.

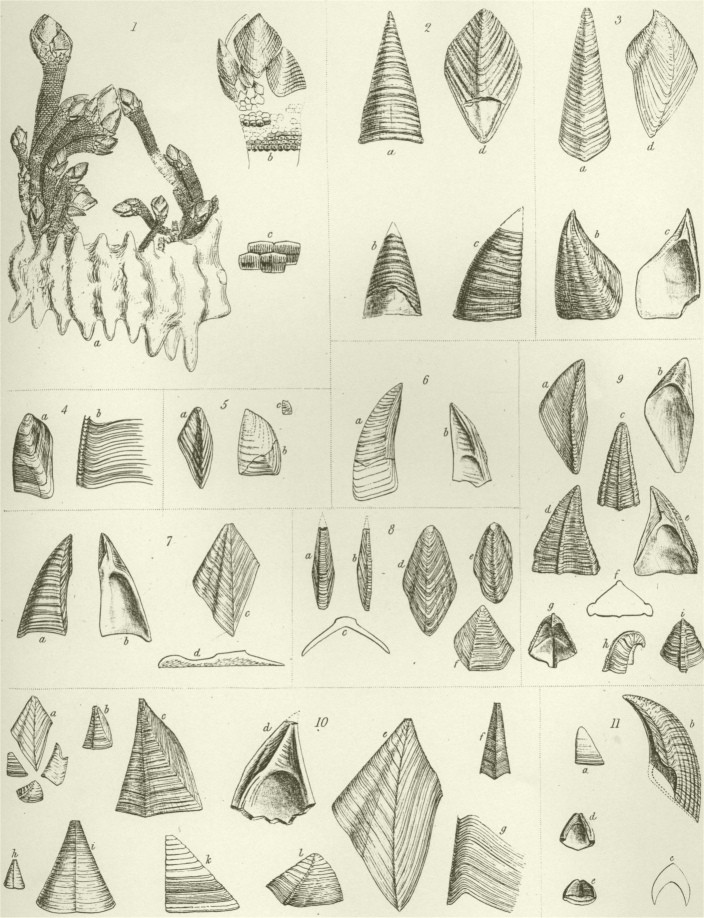

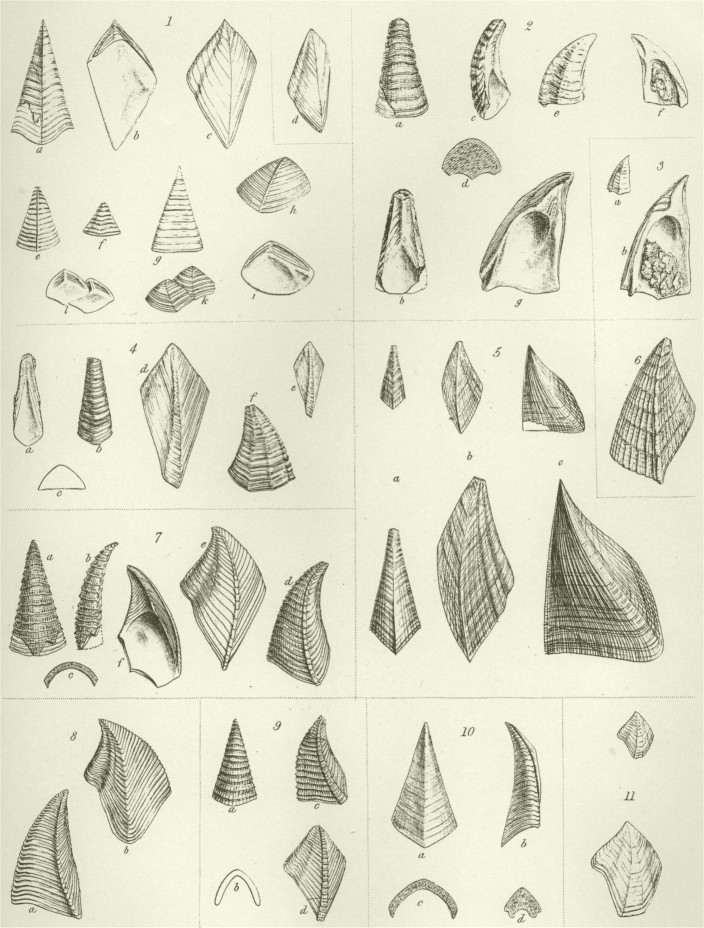

Carina narrow, widening but little from the apex downwards, slightly or considerably curved inwards, with the umbo seated at the uppermost point: S. magnum, however, must be excepted, for in it the umbo is sub-central, and the valve almost angularly bent, as will be described in detail under that species. The apex rarely projects freely; but this is a variable point in the same species; the basal margin is either pointed, rounded, or rarely truncated. The chief character by which this valve can be recognised, as belonging to the genus Scalpellum, is the distinct separation by an angle, (see woodcut, Fig. 1, in the Introduction,) often surmounted by a prominent ridge, of the tectum or roof, from the parietes, which are either steeply or rectangularly inflected; the lines of growth on these parietes are oblique. A still more conspicuous character is afforded by the part (when present), which I have called the intra-parietes; these give to the valve a pieced appearance, and seem let in, to fill up a vacuity between the upper part of the carina and the terga, and this is their real office; they are separated from the true parietes by a ridge, which evidently marks the normal outline of the valve. These intra-parietes are flat, and they have a striated appearance rather different from the rest of the valve; and the lines of growth on them are extremely oblique, almost parallel to the inner margins of the valve.

Scuta very slightly convex; four-sided; the tergal and lateral margins being divided by a slightly projecting point or angle; and this is the chief character by which the scuta of this genus can be distinguished from those of Pollicipes. The umbo is seated at the uppermost point, except in S. magnum, and in S. (?) cretæ (Tab. I, fig. 1 c, and fig. 11 c), in which species the lines of growth, instead of terminating at the angle separating the lateral and tergal margins, are produced upwards, so that the valve is added to above the original umbo. In S. tuberculatum (fig. 10 d), the scuta present an intermediate character between that in ordinary fossil species, for instance in S. fossula (fig. 4 a), and in S. magnum and cretæ. The occludent margin is nearly straight, or slightly curved; both it and the lateral margin form nearly rectangles with the basal margin, which is nearly straight. Internally the depression for the adductor scutorum is generally, but not always, very plain; sometimes the valve is filled up and rendered solid in the upper part above the adductor muscle. The apex sometimes projects freely, and is internally marked with lines of growth. The internal occludent margin, or edge, is also often marked by lines of growth, and the part thus marked, close above the adductor muscle, sometimes becomes suddenly wider; this is caused by some slight change in the position of the animal's body during growth.

Terga flat, either trigonal or rhomboidal, and, in the former case, sometimes so much elongated, with the carinal margin so much hollowed out, as to become almost crescent-shaped; a slight furrow often runs from the upper to the basal angle. Internally, in the upper part, there is in some species a little group of small longitudinal ridges, unlike anything I have seen in recent species, and serving, I apprehend, to give firmer attachment to the corium.

c

[page] 18 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

Rostrum unknown in any fossil species; but judging from recent species, it probably existed in all.

Upper latera known only in three species; in S. magnum it is irregularly oval, with the umbo central: in S. quadratum and fossula, five-sided, with the umbo at the upper angle: in the eocene S. quadratum, however, an inner ledge very slightly projects beyond the two upper sides, and first indicates a tendency to upward growth. Rostral latera, known only in S. magnum and quadratum, they are transversely elongated, narrow, and small. Infra-median latera unknown; they probably existed only in S. magnum. Carinal latera, known in S. magnum, quadratum, fossula, solidulum, and maximum; in the first species they are transversely elongated; in the three latter, of an irregular curved shape, and flat. In the fossil and recent species, the rostral and carinal latera grow chiefly in a direction towards each other; so that their umbones are close to, or even seated exteriorly to, the carinal and rostral ends of the capitulum. Peduncle, calcified scales are known only in one species, the S. quadratum; but they probably existed in all : the naked peduncle, however, of the recent S. Peronii must make us cautious on this head.

[A] Valvæ quatuordecem: Carinæ umbone sub-centrali.

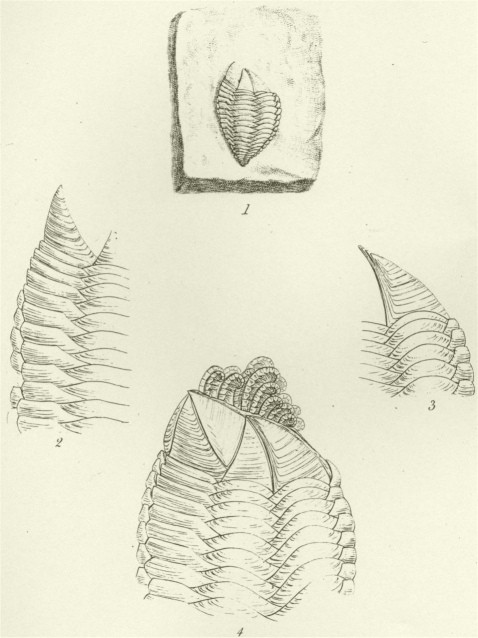

1. SCALPELLUM MAGNUM.1 Tab. I, Fig. 1.

S. Laterum carinalium et rostralium umbonibus liberè (sicut cornua) prominentibus, dimidiam seu tertiam partem longitudinis valvarum æquantibus.

Carinal and rostral latera, with their umbones projecting freely like horns, and equalling one half or one third of the entire length of these valves.

Coralline Crag (lower part). Sutton, Gedgrave, Sudbourne. Mus. S. Wood and Lyell.

From the close affinity between this species and the recent Scalpellum vulgare, we may confidently infer that the capitulum consisted of fourteen valves, which are all preserved in Mr. Wood's collection, with the exception of the infra-median latera and of the rostrum. This latter valve would, no doubt, be rudimentary, and it has been overlooked by naturalists even in the recent species. The chief difference, excepting size, between these two species, is in the form of the rostral and carinal latera, but unfortunately these valves are extremely variable. It might even be maintained, with some degree of probability, that S. magnum was only a variety of S. vulgare. The valves of S. magnum are all thicker, stronger, more rugged, and considerably larger than in S. vulgare. Taking

1 I have followed Mr. Morris in his Catalogue, in adopting this name from the MS. of Mr. Searles Wood, to whose kindness I am greatly indebted for having placed in my hands the whole of his large series of valves of this species.

[page] 19 SCALPELLUM.

the largest scutum, tergum, carina and upper latera in Mr. Wood's collection, they are very nearly double the size of the same valves in the largest specimen of S. vulgare seen by me, namely from near Naples, which had a capitulum eight tenths of an inch in length; and they are more than double the size of the same valves in any British specimen. Scalpellum magnum probably had a capitulum one inch and a half in length.

Carina (Tab. I, fig. 1 b and f) abruptly, almost rectangularly bent, with the umbo of growth seated just above the bend, at about one third or one fourth of the entire length of the valve from the upper point; form linear, with the lower part slightly wider than the upper. Exteriorly the surface is rounded with no central ridge, excepting near the umbo, where the narrowness of the whole valve gives it a carinated appearance; basal margin rounded. From the umbo two faint ridges run to each corner of the basal margin, separating the steeply-inclined parietes from the roof,—a character of some importance in the cretaceous species of this genus: outside of these two ridges there are other two ridges, not extending down to the basal margin, and separating the parietes from the intra-parietes, which latter being united at their upper ends, and produced upwards, form that part of the carina which is above the umbo. By comparing the lateral views of the carina of the cretaceous S. fossula (fig. 4 c), and of this species, it will be seen, that the apparently great difference of the umbo of growth being either at the apex, or, as in this species, sub-central, simply results from the lines of growth of the intra-parietes meeting each other, the valve being thus added to at its upper end. The carina of S. magnum, examined internally, is found often to be narrower under the umbo than either above or below it, a character I have not seen in the recent S. vulgare. The lateral width or depth of the valve (measured from the umbo to the inner edge) is also greater than in S. vulgare: this portion is internally filled up and solidified. No part of the apex of the valve projected freely. The longest perfect specimen which I have seen, is half an inch in length; but I have noticed fragments indicating even a greater size.

Scuta (fig. 1 c) much elongated, trapezoidal, slightly convex; umbo placed on the occludent margin at about one fourth of the entire length of the valve from the apex, so that the valve grows upwards and downwards. Occludent margin straight, slightly hollowed out above the umbo, forming rather less than a right angle with the basal margin, which latter is at right angles to the lateral margin. The tergal margin is separated from the lateral by a slight projection (beneath which the margin is a little hollowed out), and from this projection there runs a ridge, often very conspicuous, to the umbo. The part above the ridge, stands at rather a lower level than that below it, and the lines of growth on it are generally less distinct. This is connected with the fact, as ascertained in S. vulgare, that the valve, during its earliest stage, grows only downwards, the ridge thus indicating the original form of the valve and tendency of the lines of growth. On comparing that part of the scuta beneath the umbo and ridge, in the present species (Tab. I, fig. 1 c), with the whole valve in some other species, for instance in S. fossula (fig. 4 a), in which the umbo is seated at the apex, as it was in the first commencement of growth in S. vulgare and magnum, it

[page] 20 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

will be seen how closely the two valves resemble each other. The scutum of S. tuberculatum (fig. 10 d) is intermediate in its manner of growth between those of S. magnum and fossula. Internally, the impression for the adductor muscle is deep: on the occludent margin, close to the umbo, there is a deep fold, which is connected with the growth of the upper part of the valve being subsequent to that of the lower part. There is very little difference between this valve and that of S. vulgare; the upper part, however, appears to be always thicker. Length of largest specimen one eighth of an inch.

Terga (fig. 1 d) triangular, sometimes approaching to crescent-shaped; flat and thin, though the thickness of the valve varies. Carinal margin straight, or very slightly hollowed out; in its upper part there is a barely perceptible prominence marking the limit of the upward extension of the carina. Basal angle blunt, rounded; from it a line, formed by the convergence of the zones of growth, runs near and parallel to the carinal margin, up to the apex. Occludent margin about equal in length to the scutal; parallel to the former, a slip of the valve is rounded and slightly protuberant, and this portion projects a little on the scutal margin. A very small portion, or none, of the apex of the valve projected freely. This valve is somewhat narrower, and the scutal margin straighter, than in S. vulgare.

Rostrum unknown, no doubt rudimentary, probably quadrangular.

Upper latera (fig. 1 e) flat, oval, with the upper half a little pointed; the lower margin shows traces in a varying degree consisting of three sides. The surface, but chiefly of the lower half, is faintly marked with striæ radiating from the centre. The umbo lies in the middle, and from it two slight ridges, first bending down, diverge on each side. In Scalpellum vulgare this valve (which is very similar in shape to that of S. magnum) at the first commencement of its growth, as with the scuta, is added to only downwards; and thus the two diverging ridges mark the form which the valve originally tended to assume: bearing in mind that the basal margin tends to be three sided, if we remove that part of the valve above the ridges which have been superadded to the original form, we shall have a five-sided valve, essentially like that in the S. quadratum and S. fossula (fig. 3 e, and fig. 4 d).

Rostral latera (fig. 1, g to k) elongated, widening gradually from the umbo to the opposite end, which is equably rounded: umbonal half free, curling outwards; the internal surface of the other half (h) is nearly flat and regularly oval, with its end towards the umbo pointed; the freely projecting portion varies from nearly one half to one third of the entire length of the valve; but in one distorted specimen it was only one sixth of this length. The width, also, of the valve varies (g and h), compared to its length. This valve, compared with its homologue in S. vulgare, differs more than any of the preceding valves; it is proportionally larger, and the internal or growing surface is oval, instead of being oblong and almost quadrangular; and the umbonal or freely projecting portion in S. vulgare is only one sixth or one seventh of the entire length of the valve.

Infra-median latera unknown.

Carinal latera (fig. 1, l to n) narrow, thick, much elongated, widening gradually from the umbo to the opposite end, which is rounded and obliquely truncated. Surface, exteriorly

[page] 21 SCALPELLUM.

flat; internally convex. The umbonal, freely projecting portion is sometimes more than half, sometimes only about one third, of the entire length of the valve. This portion curls outwards and likewise upwards. The degree of curvature and the width (m and n), in proportion to the length, varies. The upper and lower margins are approximately parallel to each other; the umbonal end of the growing surface is bluntly pointed. This valve differs from its homologue in S. vulgare, in being larger, much narrower in proportion to its length, more massive, and with a far larger portion of the umbonal end freely projecting; also in the approximate parallelism of the upper and lower margins, and in the umbonal end of the growing surface being pointed instead of square. In S. vulgare the upper margin is much more curled upwards than the lower, and the freely projecting portion is only one fifth of the entire length of the valve.

Taking the largest specimens in Mr. Wood's collection, the freely projecting portions of the carinal latera must have stuck out like horns, curling from each other and a little upwards, for a length of a quarter of an inch. So again, the much flattened horns of the rostral latera, curving from each other, but not upwards, must have projected half an inch beyond the probably rudimentary rostrum. The capitulum must have presented a singular appearance, represented in the imaginary restored figure (fig. 1 a), with its pair of projecting horns at both ends.

Peduncle; calcareous scales unknown, but undoubtedly they existed.

Varieties: the variation in the rostral and carinal latera has already been pointed out. In Mr. Wood's collection there are numerous scuta, terga, carinæ, and carinal latera, from Sutton; and these are all smaller than those above described, which come from Sudbourne, and than some others in Sir C. Lyell's collection from Gedgrave. All these places, however, belong (as I am informed by Mr. Wood) to the same stage of the Coralline Crag. In the Sutton specimens the carinal latera show the same character as in those from Sudbourne, but the carina apparently is not internally so much narrowed in under the umbo; this, however, is a character which is conspicuous only in the larger Sudbourne specimens, and anyhow cannot be considered as sufficient to be specific.

I may take this opportunity of stating, that in Mr. Harris's collection of organic remains from the chalk detritus, at Charing, in Kent, I have found the upper part of a carina of a very young and minute Scalpellum, which cannot be distinguished from this species; but considering the state of the specimen, it would be extremely rash to believe in their identity. All the known cretaceous species have the umbo at the apex, so that the Charing specimen differs remarkably from its cretaceous congeners.

[page] 22 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

[B] Valvæ duodecem: Carinæ umbone ad apicem posito.

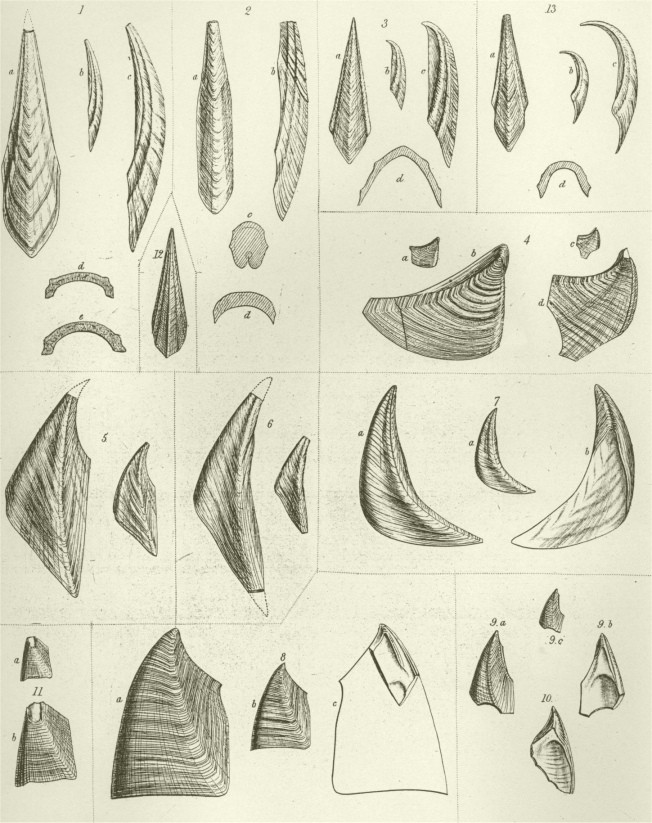

2. SCALPELLUM QUADRATUM. Tab. I, fig. 3.

XIPHIDIUM QUADRATUM. Dixon, in Sowerby's Mineral. Conch., Tab. 648; Geology of Suffolk, Tab. xiv, figs. 3 and 4.

POLLICIPES — ? J. Sowerby. Geolog. Trans., 2d series, vol. v, pl. 8, fig. 5.

S. tecto parietibusque carinæ planis, lævibus, simplicibus, margine basali feré rotundato; Lateribus superioribus quinque-lateralibus, lævibus.

Carina, with its tectum and parietes flat, smooth, and simple; basal margin almost rounded. Upper latera five-sided, smooth.

Eocene Tertiary. Bognor; Hampstead. Mus. S. Wood, F. Edwards, N. Wetherell.

My materials consist of a slab of rock, belonging to Mr. S. Wood, almost made up of the valves of this species, of two beautiful specimens in Mr. F. Edwards's collection, and of some excellent drawings from Mr. Dixon's specimens by Mr. James de C. Sowerby, in the Mineral Conchology.1 The valves in several of these specimens are nearly in their proper positions, though there is not one in which they have not slipped a little. Their relative positions are given, I believe nearly correctly, in Pl. I, fig. 3 a. Their number I have little doubt was twelve. This, however, includes a rostrum, probably almost rudimentary, the existence of which I infer only from the analogy of all recent species. Mr. J. Sowerby supposed that there were, as in S. vulgare, four pair of latera (and therefore fourteen valves in all), but I conclude, without hesitation, that there were only three pair, as in the recent S. rutilum (nov. spec.), to which the S. quadratum is much more nearly allied than to S. vulgare.

Capitulum: elongated, probably composed of twelve valves. Carina (fig. 3, d, i, k), rather narrow, slightly and regularly bowed and widening from the apex to the basal margin, which latter is bluntly pointed, or almost rounded; internally deeply concave; externally with the tectum and parietes flat, and at right angles to each other;—hence the carina is square-edged, and its specific name has been given to it. Scuta (fig. 3, b, h) oblong, occludent margin slightly arched, forming with the basal rather less than a right angle; tergal margin separated by a just perceptibly projecting point from the lateral margin, which latter is very slightly hollowed out; whole valve slightly convex, with a trace of a ridge running from the apex to the baso-lateral angle. Internally (h), there is a large pit for the adductor scutorum, above which there is a slight depression or fold marked with c urved lines of growth, and in this depression on each side complemental males

1 Some small fragments were found by Mr. Wetherell, and are noticed in his Paper in the fifth volume of the 'Geolog. Transactions,' entitled " Observations on a Well dug on the south side of Hampstead Heath."

[page] 23 SCALPELLUM.

were probably attached. Terga (fig. 3 c) triangular, large, flat, basal angle bluntly pointed; apex slightly projecting, as a solid horn; occludent margin very slightly arched. Rostrum unknown; judging from the narrowness of the umbones of the rostral latera, it was probably minute or rudimentary. Upper latera (fig. 3 e) large compared with the lower valves, flat, five-sided, with the two upper sides the longest; of the three lower sides, that corresponding with the end of the rostral latera is generally (especially in young specimens) the shortest. Umbo seated at the uppermost angle; but in full-sized specimens, a narrow ledge has been added, during the thickening and growth of the valve, along the two upper margins, and consequently round the apex. Rostral latera (fig. 3 f) extremely narrow, three or four times as long as wide; considerably arched, extending parallel to the basal margin of the scuta; widening gradually from the umbo to the opposite end, which is obliquely truncated in a line (as I believe) corresponding with the shortest side of the upper latera; inner surface smoothly arched; during growth, the narrow rostral half of the valve becomes much thickened, and at the same time added to along its upper margin, thus producing a solid, sloping, projecting edge; umbo slightly projecting. Carinal latera (fig. 3 g) almost flat, not elongated, of a shape difficult to be described; approaching to a triangle, with curved sides, and one angle protuberant.

Peduncle. The calified scales are apparently large in proportion to the valves of the capitulum; transversely elongated, pointed at both ends, and more or less crescent shaped.

Affinities. This species was generically separated from Scalpellum by Mr. Dixon, as I am informed by Mr. James Sowerby, solely owing to the umbo of growth in the carina being at the apex, instead of being sub-central, as in S. vulgare; but I need not here repeat the reasons already assigned for at present keeping all the recent and fossil species under the same genus. In the umbo of growth, in the carina and scuta being seated at their upper ends, in the square form of the carina, in there being only three pair of latera, and in the large size of the upper latera, this eocene species is much more closely allied to S. rutilum (nov. spec., of which the habitat is unfortunately not known,) than to any other recent species. In some respects, however, I may remark, S. rutilum is even more closely related to certain cretaceous forms. To S. ornatum, the nearest recent congener of S. rutilum, the present species is allied by the narrowness of the rostral latera, and by the large size and peculiar shape of the scales on the peduncle : the carinal latera perhaps rather more resemble those of S. vulgare than of any other recent species. Certainly, all the affinities in S. quadratum point to S. rutilum, ornatum, and vulgare, and these three recent species are characterised by having males or complemental males attached to the sides of the orifice of the sack, whereas, in the other species, they are elsewhere attached; hence it is that I believe that males were probably lodged in the slight depressions described on the inner sides of the scuta; but the depression is not here nearly so distinctly developed as it is in the recent S. ornatum, and more resembles the fold on the occludent edge of the valve in S. vulgare: I must add that folds of this nature do not necessarily imply the presence of males.

[page] 24 FOSSIL CIRRIPEDIA.

3. SCALPELLUM FOSSULA. Tab. I, fig. 4.

POLLICIPES MAXIMUS. J. Sowerby. Min. Conch., tab. 606 (a tergum), fig. 3.

S. carinâ inter-parietibus instructâ; tecto utrinque costis magnis, tumidis, superne planatis, marginato; margine basali obtusè acuminato. Lateribus superioribus quinquelateralibus; costis duabus modicis ab apice ad marginem basalem continuatis.

Carina, having intra-parietes, with the tectum bordered on each side by large, protuberant, flat-topped ridges; basal margin bluntly pointed; upper latera five sided, with two slight ridges extending from the apex to the basal margin.

Upper Chalk. Norwich; Northfleet, Kent. Mus. Fitch, J. de C. Sowerby, Wetherell.

General Remarks. My materials consist of two specimens, belonging to Mr. Fitch, most kindly lent me for examination; in which, taken together, the scuta, terga, carina, upper and carinal latera, are seen almost in their proper places. In Mr. J. Sowerby's collection there is a single scutum, also, from Norwich. From analogy with the eocene S. quadratum and the recent S. rutilum, I have little doubt that there were only three pair of latera; and that, probably, there was a rostrum. With respect to the exact position of the carinal latera, there is, as also in the case of the S. quadratum, some little doubt.

Capitulum narrow, elongated, probably composed of 12 valves, which are moderately strong, and apparently closely locked together. The length of the capitulum in the largest specimen was 1.1 of an inch.

Carina (fig. 4, c, g, h) strong, moderately bowed, extending far up between the terga, almost to their upper ends; rather narrow throughout, gradually widening from the apex to the base; lines of growth plain; no portion projects freely. The tectum or central portion is slightly arched, subcarinated, and bounded on each side by flat-topped, protuberant ridges: the tectum terminates downwards in a blunt point (the two margins forming an angle of rather above 90°), which projects beyond the bounding ridges; the tectum and the two bounding ridges all widen gradually from the apex towards the base. The parietes are channelled or concave; they do not extend so far down as the ridges bounding the tectum. In the upper half of the carina, we here first see the additional parietes, or intra-parietes, which appear as if formed subsequently to the other parts, and let in between the ordinary parietes of the carina, and the terga. It has been already shown, under S. magnum, that it is the intra-parietes produced upwards, which causes in that and some other species the umbo of the valve to be sub-central.

Scuta (fig. 4, a, f) oblong, the basal margin only slightly exceeding half the entire length of the valve; valve strong, rather plainly marked with lines of growth; basal margin at nearly right angles to the occludent margin; tergal margin separated by a slightly-projecting

[page] 25 SCALPELLUM.

point from the lateral margin, which in the lower half is slightly protuberant; tergal margin straight, with the edge thickened and slightly reflexed. A distinct, square-edged ridge (therefore formed by two angles) runs from the umbo to the baso-lateral angle, which is itself obliquely truncated. Internally (f), there is a large and deep pit for the adductor scutorum. Terga (fig. 4 b) triangular, flat, large, fully one third longer than the scuta; basal half much produced; basal angle pointed; from it to the apex or umbo there runs a narrow, almost straight furrow, at which the lines of growth converge—it runs at about one third of the entire width of the tergum (in its broadest part) from the carinal margin. Parallel to the occludent margin, and at a little distance from it, there runs a wide, very shallow depression up to the apex. The scutal margin is not quite straight, about a third part, above a slight bend corresponding with the apex of the upper latera, being slightly hollowed: from the above bend a very faint ridge runs to the apex of the valve. Upper latera (fig. 4 d) large, flat, with five sides, of which the two upper are much the longest; the basal side is next in length, and the scutal side much the shortest. As far as I can judge of the positions of the lower valves, with respect to the upper latus, I believe, that the rostral latera, probably, abutted against the shortest of the three lower sides; that the carina ran along the one next in length, and the carinal latera along the middle basal side, which I suppose extended in an oblique line, and not parallel to the base of the capitulum: the two upper long sides no doubt touched the scuta and terga. The umbo of growth is at the apex; there is, however, a trace of a projecting ledge added round the upper margins during the thickening of this upper part of the valve. Two slight ridges run from the apex to the two corners of the middle of the three lower sides. Carinal latera (fig. 4 e) : these are not quite perfectly seen: the umbo forms a sharp point, whence the valve rapidly expands and curves apparently downwards and towards the upper latera. Near one margin there is a very narrow furrow, and on the other a wide depression, both running and widening from the umbo to the opposite end, which is slightly sinuous. I imagine these carinal latera occupied a nearly triangular space between the middle of the three lower sides of the upper latera and the basal portion of the carina. Rostral latera, rostrum and peduncle unknown; the rostral latera must have been very narrow.