Emma Darwin's Recipe Book

An introduction by Janet Browne

Not so widely known as other notable Victorian women, Emma Darwin lived nearly the entire length of the nineteenth century. When she was born, in 1808, the ruling monarch was King George III. In that same year, Beethoven premiered his Fifth Symphony, Goethe published the first part of Faust, and Napoleon's armies were marching in ever widening arcs across Europe. By the time of her death in 1896, the world she knew was utterly transformed. The British Empire was rapidly expanding, science and technology were advancing in dramatic ways, and society and culture were very different from the days of her youth. As a girl, Emma traveled by horse and carriage and read Jane Austen. In the last decades of her life, she encountered the beginnings of modernity. She tried an early form of telephone, saw one of her sons stand for Parliament, read Robert Louis Stevenson, and wondered, with some misgivings, whether her granddaughters should ride bicycles in the street. Throughout, she remained a remarkable woman.

Married to her cousin Charles Darwin, she experienced many of these changes at first hand, for her own husband emerged as a central figure in the intellectual, biological, and theological revolutions of the nineteenth century. His writings on evolution by natural selection confronted everything that had previously been thought about the history and origins of living forms, and his book On the Origin of Species made him one of the most celebrated thinkers of his day. Through the years of controversy and debilitating private illness that followed his publication of this notorious volume, Emma Darwin cared for her husband with love, resilience, and a great deal of good humour. She provided the emotional security that Charles Darwin needed to bring his great intellectual project into the public domain.

But Emma Darwin should not be encountered merely as an appendage to her famous husband. Much of her lively character emerges in her letters, published after her death by her daughter Henrietta Litchfield. Naturally the round of family visits and daily life took precedence. Emma was the granddaughter of Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery manufacturer and industrialist, one of the most important individuals in revolutionizing European consumer taste in the eighteenth century. This branch of the Wedgwood family was prosperous and well connected, including close personal ties with the Darwin family of Shrewsbury. Josiah Wedgwood's daughter Susanna married Robert Waring Darwin in 1796, soon becoming parents to a large family that included Charles Darwin. Emma's marriage to her cousin Charles in 1839 strengthened an already tightly knit family community. She regularly exchanged letters with many members of the combined DarwinWedgwood circle, and increasingly with growing numbers of children, nieces, and nephews. These letters provide marvellous—and frequently amusing—insight into her life with Darwin. It could almost be said, too, that these letters describe what it might be like to live with science, for over the years she came to know many of Darwin's scientific friends and acquaintances, and often welcomed into her home his colleagues, such as Thomas Henry Huxley. She writes with humour about the activities of a large Victorian household and the village in which the family lived. Her letters indeed have much to tell historians about the structure of domestic life during the most formative years of the century.

Yet, like many other Victorian women of her social background, Emma had another voice, a voice that is less often heard because of the scarcity of archival materials. Emma Darwin ran the household and carried out many small charitable activities as was customary for women of her status. We know this, not just from Darwin's recollections, or from those of her children and friends, but more especially because Emma kept a set of domestic accounts for nearly fifty years that documented her kitchen expenditure and other household costs, including wages for the female servants. Her account books included categories for meat, candles, groceries, soap, loaf-sugar, tea, eggs, bread, and so forth, to a total of twenty headings.

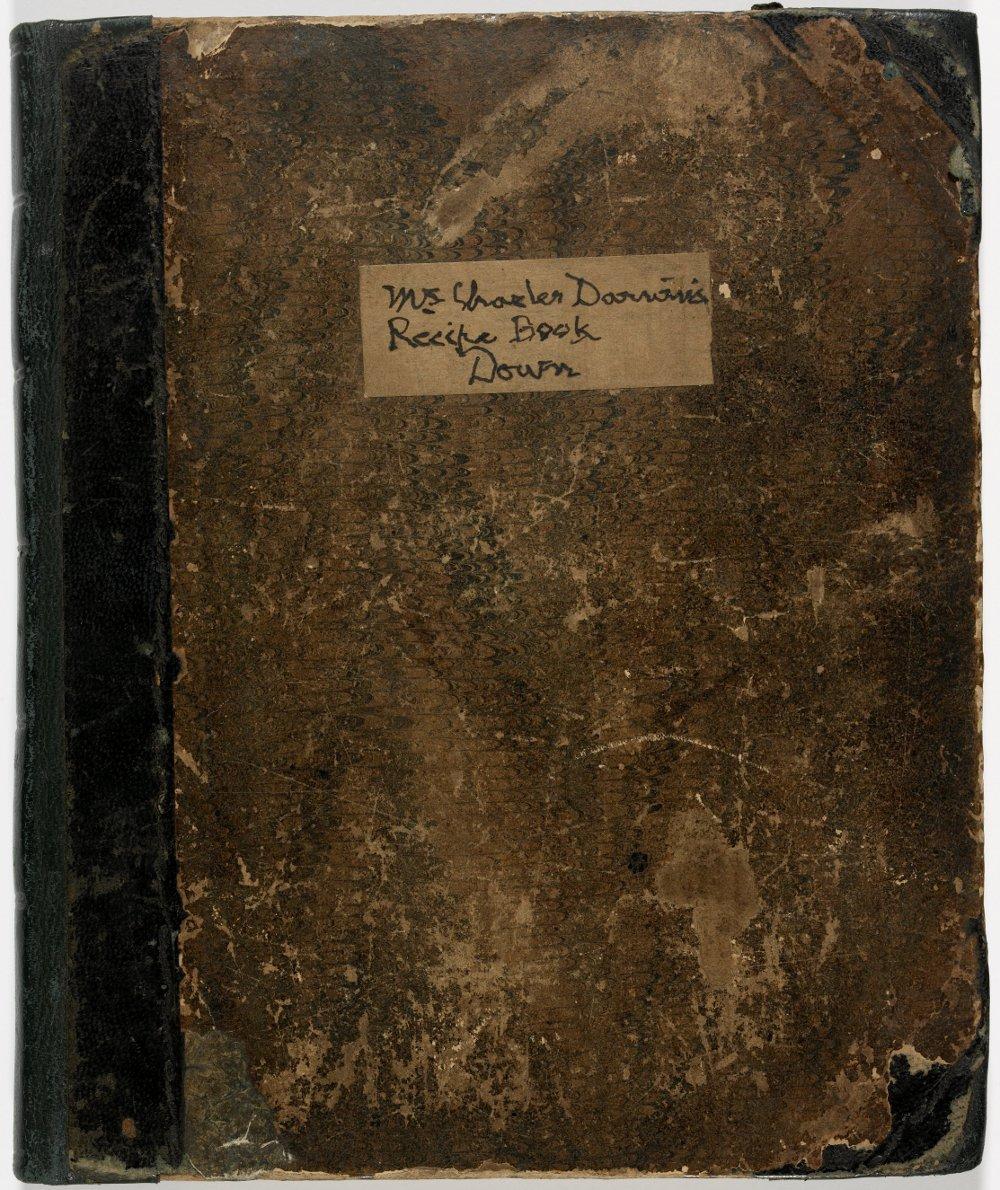

And […] she also kept a recipe book. This recipe book reflects her position as the individual responsible for feeding the family, entertaining, and maintaining the domestic space. While her husband kept a careful eye on the external financial affairs of the family, Emma Darwin directed the kitchen staff, kept accounts, and looked after the household concerns. To be able to read her recipes today is therefore to have remarkable access to the inner recesses of a prosperous Victorian home. Moreover, it has long been appreciated that food, and the serving of food, lies at the very heart of the social process. […]

Here we can almost see the Darwin family as they sit around the table. […] Over the years, a number of us working in the Darwin archives have attempted to give parties following Emma's instructions. Now guests will simultaneously be able to enjoy real food and the quirky pleasures of dining with history.

This text served as the preface to Bateson and Janeway, Mrs Charles Darwin's recipe book. 2009. Reproduced with permission of Janet Browne.