Geological specimen notebooks kept by Charles Darwin on HMS Beagle (CUL-DAR236)

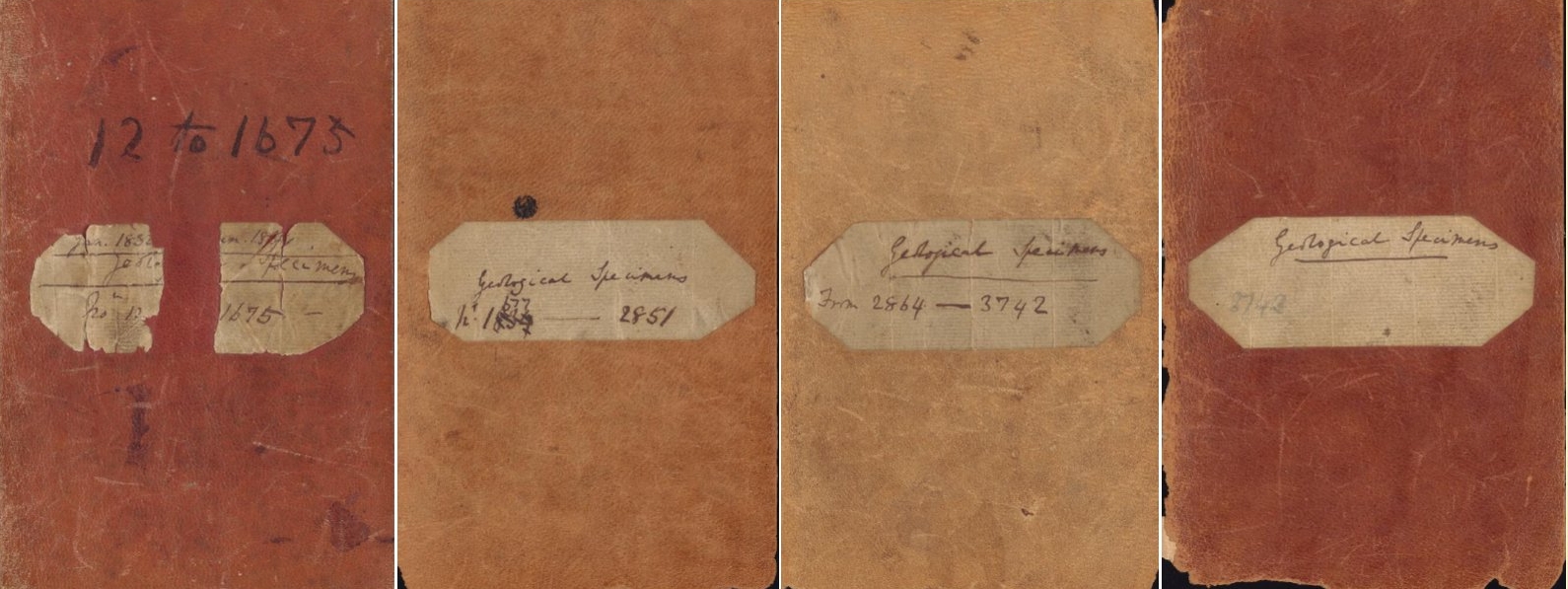

These four notebooks were used by Charles Darwin during the Beagle voyage (1831-1836) to record his geological specimens. The notebooks have been on deposit at CUL since 1981 from the Sedgwick Museum (Porter 1985). All four of notebooks are identical to the six now held by English Heritage at Down House, which Darwin used for living plants and animals as described and transcribed by Keynes in Zoology notes (2000). Darwin referred to what is now the geological notebooks as his 'Catalogue' in an August 1832 letter to Henslow (CCD1:251) or his 'Geological Book' (Zoology notes, p. 343). For a general description of the notebooks see CCD1:252, note 3. They have red leather covers, measure c. 18 x 11.5cm. As can be seen (e.g. on CUL-DAR236.4.16v) the paper is watermarked 'JOHN HALL 1831' (I am grateful to Elizabeth Smith of CUL for supplying images of the watermarks).

Every page of the notebooks is unruled but has one vertical left margin line. Darwin usually wrote the specimen number in the margin and used the rest of the page for the description of the specimen(s), but he also sometimes added symbols or short annotations in the margin. Occasionally, on pages where space was limited (e.g. CUL-DAR236.1.32v) Darwin's description starts in the margin. For readability we have not reproduced this detail in the transcriptions. Neither have we made any attempt to align the entries horizontally on the verso pages with the respective recto pages.

Gaps in the geological specimen numbers indicate where Darwin has applied those numbers to his 'zoology' specimens, as published by Keynes (2000). In fact, 'zoology' is a misnomer as Darwin simply listed all his living plants and animals (i.e. everything that wasn't geological) as either 'in spirits of wine' or 'not in spirits of wine'. As Herbert (2005) has detailed, Darwin used Fitton (1827) as his guide to collecting in geology. In his Journal of researches (1839, pp. 598-599) he explained his method of collecting and in his 'geology' chapter of 'The Manual of Scientific Enquiry' he recommended the following procedure for what he rather ambiguously called 'ticketting' specimens: "Every single specimen ought to be numbered with a printed number ...and a book kept exclusively for their entry." (Darwin 1849, p. 161). To judge from the specimen photographed in Pearn (2009, p. 15) bearing a printed number ('49') exactly like Darwin's, but collected by Adam Sedgwick during his field trip in Wales with Darwin in 1831, Darwin copied Sedgwick's method when preparing for the Beagle voyage. What Darwin should have made clearer, we suggest, is that he used temporary numbers in the field and often listed them in his field notebooks. It is actually these 'field numbers' which he says must be given to specimens immediately on collection and that these can be replaced by permanent numbers once back at base or on board ship when the collector has access to pen and ink and his specimen catalogues (in his case CUL-DAR236).

There are some lists made by Darwin showing both his temporary field numbers and permanent numbers for many specimens he collected in the Andes. These lists are indispensable because they give his 1835 field numbers alongside his final CUL-DAR236 numbers. The most important of these lists are DAR 39.147 which lists 118 rocks from 2598-2716 (with field numbers noted in the St. Fe Notebook) and CUL-DAR39.153-157 which lists 283 rocks from 2850 to 3133 (with field numbers noted in the Coquimbo, Copiapo and Despoblado Notebooks; see Chancellor and van Wyhe 2009). Darwin's notes from his discussions with Miller in CUL-DAR39.68-69 covering rocks from all parts of the voyage are also useful.

As with the lists transcribed by Keynes, Darwin listed his geological specimens in numerical order on the right-hand (recto) pages and then wrote any notes about the specimens on the facing left-hand (verso) page. The notes are tied to the specimens by the specimen number and sometimes there is more than one note for a particular specimen, indicating that the notes were written at different times, thus disrupting the 'correct' numerical sequence. In order to read CUL-DAR236 as the full continuous list of Darwin's specimens but ignoring the notes it is important ONLY TO READ THE RECTO PAGES.

CUL-DAR236 is almost all in ink in Darwin's hand except where pencil is noted. The major exception to this are five pages in pencil at the end of CUL-DAR236.4 and other exceptions are the marginal abbreviations L, M, R and H and the symbols v which are usually written in pencil. There are numerous interlineal pencil annotations which are often difficult to decipher. It seems very likely that everything in pencil is of post-voyage date. The symbol x is sometimes in ink and sometimes pencil and sometimes both, depending on whether the corresponding verso note is in ink or pencil. On CUL-DAR236.3.35r there are faint pencil 'x' marks against seven of the specimens listed on that page in addition to the two ink 'x' marks for notes on the left hand verso pages. The meaning of these pencil 'x' is obscure. There are a few instances of ink over pencil (e.g. CUL-DAR236.1.46v and the back pages of 236.4). There is a note at the back of 236.1 in Miller's hand relating to specimen 1018 (CUL-DAR236.1.50r). AJP's folio numbers have not been transcribed.

For definition of geological terms see the glossary in Lyell's Principles of Geology (vol. 3, 1833) which Darwin had from mid-1834. There are also many instances which show the facility with which Darwin used chemical names. Darwin's spelling, punctuation and capitalisation can be inconsistent (e.g. 'Felspar' for 'feldspar') but so far as possible it is transcribed as seen. At the time of the Beagle voyage 'felspar' was often used in books which were in the ship's library (e.g. Daubeny 1826; Henslow 1822; Jameson 1822; Phillips 1816) and it is spelt 'felspar' in Lyell's glossary ('Principles of Geology', vol.3, 1833), also available on the Beagle. 'Feldspar' was used by some authors available to Darwin (e.g. Aubuisson de Voisins 1819) but 'felspar' was still in use into the 1860s (e.g. Ramsay 1862). Darwin himself seems usually to have used 'felspar' (and its derivatives e.g. 'felspathic') but he did sometimes use 'feldspar' and it is also likely that when he was writing quickly the 'd' was intended but merged with the other letters and became invisible. There is a similar problem with the adjectives 'glassy' and glossy' which both can apply readily to feldspar, so certainty as to which was intended is elusive. Darwin's spelling of 'colour' as 'color' seems to be more consistent throughout the notebooks, although 'colour' seems to occur more often as the voyage nears its end. Darwin quite often used the Spanish reversed question mark but we have silently rendered all question marks as '?'. It is also often impossible to determine whether full stops (.) are punctuation or merely pen rests, so all have been transcribed. For general discussion of Darwin's spelling habits during the voyage see Sulloway (1983).

Whenever Darwin starts to list specimens from a new locality he names this at the head of the a recto page or occasionally under an ink line drawn across the page which we signify as --------------. He generally states the year in the left margin and sometimes the month on the right, before the locality. Although the month usually tallies with the dates given in his field notebooks (see Chancellor and van Wyhe 2009) occasionally the month is slightly later. This indicates that it represents the month in which he had leisure to list his specimens rather than the month of collection. The range of localities and dates covered in each notebook is as follows: CUL-DAR236.1: January 1832 (Cape Verdes) to January 1834 (Port Desire); CUL-DAR236.2: January 1834 (Port Desire) to June (?) 1835 (Coquimbo); CUL-DAR236.3: June (?) 1835 (Coquimbo) to July 1836 (Ascension); CUL-DAR236.4: July 1836 (Ascension) to September 1836 (Terceira).

CUL-DAR236 records 2,318 specimens of which approximately 1,750 are rocks and 390 are fossils, although it is sometimes difficult to decide whether a specimen is a rock or a fossil (e.g. a piece of sandstone with leaf impressions might be a rock or a fossil). Harker's 1907 manuscript transcription of CUL-DAR236 (held with Darwin's rock collection at the Sedgwick Museum and available in Darwin Online) is invaluable but it mainly relates to the Museum's rocks collected by Darwin (omitting most of the fossils) so is of limited application. Harker's list was not intended to be comprehensive but should be consulted for its accompanying notes and for its use of more modern names and descriptions of the rocks etc. Lister (2018) should be consulted for the fossils, most of which are in the Natural History Museum (NHM) although there are some plant fossils in the British Geological Survey (BGS) collections in Keyworth (Falcon-Lang 2012).

Some of Darwin's rocks are also at the BGS: there are 43 specimens from Ascension and, apparently, eight from the Galapagos and one from the Cape Verdes (Ramsay 1862), although not all have Darwin's numbers attached. There are reasons for believing that some of these letter nine specimens were misattributed to Darwin by Ramsey, who quotes co-ordinates for 'Chatham Island, Galapagos' which are those for Chatham Island, near New Zealand! I am grateful to Thalia Grant and Greg Estes for suggesting that at least some of the Galapagos specimens are from the Galapagos but were collected by officers of HMS 'Pandora' when they were surveying there in 1847. I am also very grateful to Louise Neep for sending me the list of Darwin's BGS specimens via Adrian Lister of the NHM.

There are also a few Darwin rock specimens in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (Chancellor et al. 1988) and since Darwin also sent some specimens to the micropalaeontologist Christian Ehrenberg (1795-1876), see for example Darwin's 'Voyage of the Beagle' (1845, p. 494), there may still be some in Berlin. Darwin also sent Alcide d'Orbigny (1802-1857) many fossils for identifications which were cited extensively in Darwin (1846) so it seems likely that they may be at the Paris Natural History Museum, although they have not yet been located, despite searches. There is also one fossil skull at the Royal College of Surgeons (specimen no. 821; see Lister 2018, p. 37). Finally, it is almost certain that the whereabouts of a few other specimens has yet to be discovered.

When searching the entry for a specimen with one of Darwin's attached printed paper numbers it is crucial to note the colour of the paper; white paper signifies 1-999, red 1000-1999, green 2000-2999, yellow 3000-3999. The specimens are distributed as follows: CUL-DAR236.1: specimens 12 to 1675; CUL-DAR236.2: 1677 to 2851; CUL-DAR236.3: 2864 to 3742; CUL-DAR236.4: 3743 to 3914. Since the sequence includes 'zoological' as well as geological specimens, the actual number of geological specimens is 3,914 minus the number of 'zoological'. The number of geological specimens collected on the Beagle is therefore approximately 2,138 distributed across the notebooks thus: 706 specimens in CUL-DAR236.1, 676 in CUL-DAR236.2, 614 in CUL-DAR236.3, 142 in CUL-DAR236.4. In their detailed study of Darwin's Galapagos geology, Herbert et al. (2009, p. 7, footnote 11; see also Gibson 2009) state that the Sedgwick Museum holds 1,390 of Darwin's specimens, i.e. 65% of the total of geological specimens listed by Darwin, which must leave c. 750 in other institutions or lost.

There are two lists in Darwin's autograph held by the Sedgwick Museum which relate to CUL-DAR236, although their history is not clear. SMES-TN-5578a is a foolscap sheet giving a list of mammal fossils. It includes many important specimens listed in CUL-DAR236.1 but also lists specimens which were numbered separately, probably because Darwin had to ship them home without time to list them properly. SMES-TN-5578b is a list of fossil wood specimens, all of which are listed in CUL-DAR236. It is a page from a notebook of exactly the dimensions of CUL-DAR236 and has a matching watermark, so was almost certainly torn from the back of CUL-DAR236.4. I am now working with Dr Adrian Lister of the NHM to publish these two important documents (Chancellor and Lister, in prep.).

Dr Liz Hide, Director of the Sedgwick Museum, prepared full transcriptions of the notebooks in preparation for the Museum's then new Darwin Bicentenary displays (see Hide 2007). Dr Hide collated Darwin's descriptions with the specimens and thin sections made from them now in the Museum's collections. She has kindly made some of her work available to me for comparison and we are continuing to work together to improve the quality of our transcriptions.

There is a huge literature on Darwin's activities during the Beagle voyage. For overviews of his geological collecting and research we recommend Armstrong (2004), Chancellor (2012), Chancellor and van Wyhe (2009), Herbert (2005), Lister (2018), Nicholas and Nicholas (1989) and Pearn (2009).

Information about this document

Extent: 4 notebooks and accompanying material.

Condition: Folios 2.1v and 2.2r are stuck together and have not been photographed or transcribed.

Foliation: Folio 1.30 has been accidentally omitted from foliation.

Glossary

Do/do Darwin's abbreviation of 'Ditto' (= as above). We assume the 'doo' at 236.6.28r is a mistake.

H Darwin's abbreviation for 'Henslow' (John Henslow 1796-1861) according to Judd (1910, p. 366).

L Darwin's abbreviation of 'Lost' (= specimen lost). Usually but not always in pencil.

M Darwin's abbreviation of 'Miller' (William Miller 1801-1880), according to Judd (1910, p. 366). The letter 'M' also seems to refer to Darwin's 'Book of Measurements' which as Judd (1910, p. 366) says appears to be lost, or to a 'paper with measurements' (see CUL-DAR236.2.1r). There are also many references to an 'appendix' which has also not yet been identified among the Darwin MSS. See 'Correspondence of Charles Darwin', vol. 2 (CCD2) and lists of specimens in CUL-DAR39.68-89.

R Darwin's abbreviation of 'Rock', usually added to the main entry in pencil, perhaps with the plan of facilitating preparation of a separate list of rocks, rather in the manner of his use of 'I' to help his servant prepare a list of insects (see Keynes 2000). 'R' occurs mainly in entries from 1832 but is still used sporadically into at least late 1834. Judd (1910, p. 366) thought Darwin used 'R' for specimens he sent to 'Reeks' (i.e. Trenham Reeks 1823-1879); this may apply where the 'R' is in the margin, although correspondence with Darwin in February 1845 in CCD3 lists specimen numbers which have no 'R' in CUL-DAR236 and vice versa. There is a list of specimens analysed by Reeks at CUL-DAR39.211-212.

v Darwin's symbol of uncertain meaning. Sometimes (e.g. 236.1.46r et seq.) it is written in ink and looks like a 'tick/check' symbol. Sometimes it may just be an over-hastily jotted 'x'. When in connection with fossil mammal specimens, it is often written in pencil and may mean 'vertebrate', as such cases are nearly all listed in Sedgwick Museum fossil mammal list TN 5578a, suggesting that the 'v' is where Darwin has 'ticked off' a specimen once it had been listed on TN5578a (Chancellor and Lister 2025).

x Darwin's symbol for a note to the main entry. 'xx' means there are two notes for that specimen. Darwin also used 'x' in his zoological specimen books. Keynes (2000) thought it was a reminder to look again at a specimen, but it only occurs on recto (i.e. right-hand) pages so in fact indicates that there is a note about the specimen on the previous verso (i.e. left-hand) page. Keynes opted to incorporate the note in the main description of the specimen, where in our transcription they remain separate.

Bibliography

Armstrong, P. 1985. Charles Darwin in Western Australia. Western Australia UP. in Darwin Online.

Armstrong, P. 1991. Under the blue vault of Heaven. Indian Ocean Centre for Peace Studies. in Darwin Online.

Armstrong, P. 2004. Darwin's other islands. Continuum. in Darwin Online.

Aubuisson de Voisins, J.F. d' 1819. Traite de geognosie. Strasbourg.

Bailie, R. H., Mhlanga, M. and Reinhardt, J. 2023. The Sea Point contact, Cape Town, South Africa: a geological site made famous by Charles Darwin's visit. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 543: ?-?

Banks, M. B. 1971. A Darwin manuscript on Hobart Town. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 105: 5-19. in Darwin Online.

Banks, M. B. and Leaman, D. 1999. Charles Darwin's field notes on the geology of Hobart Town - a modern appraisal. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 133: 29-50. in Darwin Online.

Chancellor, G. R., DiMauro, A., Ingle, R. and King. G. 1988. Charles Darwin's 'Beagle' collections in the Oxford University Museum. Archives of Natural History 15: 197-231. in Darwin Online.

Chancellor, G. R. 2012. Introduction to Darwin's geological diary. in Darwin Online.

Chancellor, G. R. 2023. Signal Post Hill and Agua de la Zorra: two geological sites studied by Charles Darwin on the 'Beagle' voyage and their contributions to geoheritage. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 543: 217-228.

Chancellor, G. R. and van Wyhe, J. 2009. Charles Darwin's notebooks from the voyage of the 'Beagle'. Cambridge UP.

Chancellor, G. R. and Lister, A. 2025. Two unpublished Darwin fossil lists in the Sedgwick Museum. Archives of Natural History

Darwin, C. R. 1831-: Beagle diary, Geological diary, Zoology of the Beagle (1838-1843), Journal of Researches (1839), Coral reefs (1842), Volcanic islands (1844), Voyage of the 'Beagle' (1845), South America (1846), Geology of the Falklands (1846), Manual of Scientific Enquiry (1849), Correspondence (1985-2023) etc. All available in Darwin Online and Darwin Correspondence Website.

Daubeny, C. 1826. A description of active and extinct volcanos. London. in Darwin Online.

Falcon-Lang, H. 2012. Fossil 'treasure trove' found in British Geological Survey vaults. Geology Today 28: 26-30.

Fitton, W. H. 1827. Instructions for collecting geological specimens. In King, P. P. Narrative...Coasts of Australia. London.

Gibson, S. 2009. Early settler: Darwin's geological formation. Geoscientist 19: 18-23.

Grant, K. T. and Estes, G. B. 2009. Darwin's notes on the geology of Galapagos. in Darwin Online.

Grant, K. T. and Estes, G. B. 2009. Darwin in Galapagos: Footsteps to a new world. Princeton UP.

Harker, A. 1907. Notes on the rocks of the 'Beagle' collection. Geol. Mag. (5)4: 100-106.

Henslow, J. S. 1821-1822. Geological description of Anglesea. Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc. 1: 359-452. in Darwin Online.

Herbert, S. 2005. Charles Darwin, geologist. Cornell UP.

Herbert, S. et al. 2009. Into the field again. Earth Sciences History 28: 1-31.

Hide, E. 2007. "Trust nothing to memory": Charles Darwin's geological specimen notebooks. Conference 8-11 February. Milan: Meseo di Storia Naturale de Milano. [unpublished]

Jameson, R. (trans.) 1822. Essay on the Theory of the Earth by M. Cuvier. Edinburgh.

Judd, J. W. 1910. Darwin and geology In A. C. Seward ed. Darwin and Modern Science. Cambridge UP. in Darwin Online.

Keynes, R. D. 2000. Charles Darwin's Zoological Diary and specimen lists from HMS 'Beagle'. Cambridge UP. in Darwin Online.

Lister, A. 2018. Darwin's Fossils. London: Natural History Museum.

Lyell, C. 1830-1833. Principles of Geology. London. in Darwin Online.

Nicholas, F. W. and Nicholas, J. M. 1989. Charles Darwin in Australia. Cambridge UP.

Pearn, A. M. ed. 2009. A voyage round the world. Cambridge UP.

Pearson, P. 1996. Charles Darwin and the origin and diversity of igneous rocks. Earth Science History 15: 49-67.

Pereira, J. N. G and Neves, V. 2009. Darwin nos Acores: diario pessoal com comentarios. Observatorio do Mar dos Acores.

Phillips, W. 1816. An elementary introduction to mineralogy. London.

Porter, D. M. 1985. The 'Beagle' collector and his collections. In Kohn, D. ed. The Darwinian heritage. Nova Pacifica.

Porter, D. M. and Graham, P. 2016. Darwin's Sciences. Wiley.

Ramsay, A. C. 1862. [Catalogue of rocks in the Museum of Practical Geology]

Richardson, C. 1933. Petrology of the Galapagos Islands. Bernice P. Bishop Bulletin 110: 45-67.

Rosen, B. R. and Darrell, J. G. 2010. A generalised historical trajectory for Charles Darwin's specimen collections. IN Stoppa, F. and Veraldi, R. eds. Darwin tra scienza, storia e societa: 150th anniversario della publicazione di Origine della Specie. Roma UP.

Smith, K. G. V. 1987. Darwin's Insects. Bull. Brit. Mus. Hist. Ser. 14: 1-143.

Stone, P. and Rushton, A. W. A. 2013. Charles Darwin, Bartholomew Sulivan etc. Earth Sciences History 32: 156-185.

Stone, P. and Rushton, A. W. A. 2023. Charles Darwin's discovery of Devonian fossils in the Falkland Islands, 1833, and its controversial consequences. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 543: 205-216.

Strzelecki, P. E. 1845. Physical description of New South Wales and van Diemen's Land. Longman's. London

Sulloway, F. J. 1983. Further remarks on Darwin's spelling habits and the dating of 'Beagle' voyage manuscripts. Journal of the History of Biology 16: 316-390. in Darwin Online.

Taylor, J. 2008. The voyage of the 'Beagle'. Conway.

Thomas, B. A. 2009. Darwin and plant fossils. The Linnean 25: 24-42.

Tilley, C. E. 1947. The Dunite-Mylonites of St Pauls' Rocks (Atlantic). American Journal of Science 245: 483-491.

Wyhe, J. van. 2009. Darwin. Andre Deutsch.

Whitehead, P. and Keates, C. 1981. The British Museum (Natural History). Scala/Philip Wilson.

Various papers in special issue 2009. Revista de la Asociacion Geologica Argentina vol. 64. in Darwin Online.

For the charts of the places visited by the 'Beagle' click on the 'finch logo' next to the entry for Darwin's Journal of Researches in Darwin Online.

* Reproduced with permission from https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-DAR-00236

RN5