'A man who has seen half the world': Introduction to the Banda Oriental Notebook

The Banda Oriental Notebook takes its name from country through which Darwin travelled called Banda Oriental or 'East Bank' of the Rio de la Plata. Following independence in the late 1820s it gradually became known as the Republica Oriental de Uruguay. Today it is called Uruguay.

Banda Oriental covers two distinct periods of the voyage. The first period, November 1833, covers the Banda Oriental expedition (expedition 4 of Barlow 1933). The second period was April-May 1834 and covers the Santa Cruz expedition (expedition 5 of Barlow 1933), and some weeks which followed in Tierra del Fuego. As usual, the actual sequence of Darwin's note-taking was quite complex. The November section dates from the 14th, p. 5, to the 28th, p. 37, at about which point Darwin stopped making dated notebook entries, until he made a note dated 27 December in the Buenos Ayres Notebook.

The notebook was first used about one week after Darwin wrote p. 56a of the St. Fe Notebook. He probably switched notebooks at that point as he wanted to leave the St. Fe Notebook safe on the Beagle while he went off on a new expedition. January to April 1834 is covered in the Port Desire Notebook, then there is an entry in the B. Blanca Notebook dated 14 April, before the Banda Oriental Notebook is taken up again on 18 April for the Rio Santa Cruz expedition, followed by scattered notes en route to Port Famine, to about the end of May, pp. 38-111. After a large gap of over 120 blank and a few excised pages there are a few pages of notes which seem to be a partial continuation of the Santa Cruz sequence, pp. 240-1. The picture is not simple, however, as the B. Blanca Notebook was used on 8-15 May, pp. 73b-6b, before taking over properly on 2 June.

Darwin stopped using the Banda Oriental Notebook at the end of May 1834, at which point he had only used less than half of the notebook. So although the Banda Oriental Notebook is the fourth longest notebook in terms of number of words written in it, more than half of the notebook was never used.

Banda Oriental, November 1833

The first few pages of the notebook are blank, except for 'Charles Darwin H.M.S. Beagle' on p. 3. On p. 5 he recorded heading west from Monte Video with the intention of seeing the Rio Negro and Rio Uruguay, to take advantage of the extra month available to him once FitzRoy decided he needed more time to work up the charts he had already drafted, before rounding Cape Horn (see Keynes 1979, p. 170). Darwin's plan was to visit the estate of an Englishman, about whom we know very little except that his name was Mr. Keen, near Mercedes. Darwin spelled his name 'Keane' in Journal of researches, p. 181.

It is worth recalling that a few days before Darwin started his expedition, on 12 November 1833, he wrote to Henslow and dispatched a large consignment of specimens (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 351). Darwin was anxious to know what Henslow thought of his endeavours and Darwin did not receive the feedback he desired until the following March, just before the Santa Cruz expedition recorded in the second part of the Banda Oriental Notebook.

According to the Beagle diary, on 14 November Darwin slept 'in the house of my Vaqueano', i.e. cowboy, in Canelones, about 40km northeast of Monte Video. The next morning they 'started early', p. 5, but were hindered by flooded rivers. The following day Darwin recorded 'stomach disordered' so he had to spend a second night at a place called Cufré, but this did not stop him confirming that the rocks were 'granite and gneiss' and noting the minerals present in the granite. He also noted how this area had suffered in the 1820s during the war between the Argentines and the Brazilians.

Darwin saw an 'Owl killing snake' which is probably the one mentioned in Birds, p. 31, and he noted 'woodpecker nest in hole'. This was the bird called the campo flicker, Colaptes campestris, which was famously cited in Origin, p. 184:

On the plains of La Plata, where not a tree grows, there is a woodpecker, which in every essential part of its organisation, even in its colouring, in the harsh tone of its voice, and undulatory flight, told me plainly of its close blood-relationship to our common species; yet it is a woodpecker which never climbs a tree!

By the third edition of Origin in 1861 Darwin added the support of Azara 1809 to his assertion that the woodpecker never climbs a tree. In the copy of the 5th edition of Origin (1869) on Darwin Online, a sharp-pencilled previous owner wrote in the margin against Darwin's claim on p. 220 that the campo flicker never climbs trees, 'How could it, poor thing, when it is in a place where "not a tree grows"'.

By the sixth edition of Origin, p. 142, Darwin added reference to his hole-nesting observation in response to William Henry Hudson's (1841-1922) rather intemperate accusation in 1870 that Darwin had told a falsehood (see Darwin 1870 and Steinheimer 2004, p. 310):

Hence this Colaptes in all the essential parts of its structure is a woodpecker [....], yet, as I can assert, not only from my own observations but from those of the accurate Azara, in certain large districts it does not climb trees, and it makes its nests in holes in banks!

At the time, in Banda Oriental on 16 November 1833, Darwin noted with amusement that the postman had arrived a day late but was only carrying two letters. Darwin seems to have delivered these for him when he reached the town of Colonia [Colonia del Sacramento] the next day, 17 November: 'delivered my letters', p. 6. The old part of Colonia was established by the Portuguese in 1680 and is today a World Heritage Site. Darwin was also amused by the pride of local people in their political representatives who 'could all sign their own names', p. 7.

Darwin was intrigued by a mass of 'muscles', p. 10, (i.e. mussels) near the harbour and could not decide how they had been deposited '15 feet above high water' and mentioned them in South America, p. 2, as evidence of elevation. On pp. 11-14 of the Notebook he described the Tertiary Pampean Formation and the 'Primary' rocks which it overlays at Colonia, before making some fascinating notes about the cattle on the estancia of the Chief of Police, where he was staying.

On 18 November, on p. 13, Darwin recorded how he was able to recognise the same 'tosca' formation that he had seen far to the south at Bahia Blanca: 'eyes shut think I was in Patagonia'. On the 19th Darwin saw a white limestone quarried at the 'Calera de los Huerfanos' (Limekiln of the Orphans) which is marked on a modern map as a tourist attraction. 'Mortar formation. (V. Specimen) generally more white and pure', p. 15. From there he passed the Arroyo Las Vacas, a 'straggling thatched town' on the Riacho, p. 17, and then onto the Arroyo Las Vivoras to spend the night at the home of an American who worked at the Carmacho limekiln. By the 20th Darwin reached the Rio Uruguay at Punta Gorda and there occurs in the notebook a cryptic quote, p. 17, '"Sylvester Lellow complete collection of Banda Oriental"??!!'. Presumably Mr. Lellow was the American.

Darwin stayed the night of the 20th at the large estancia where a 90-year old woman lived who 'positively states that very early in her life no trees?! No trees except one orange tree', pp. 18-19. Darwin was told of quicklime bursting into flames in the quarry, causing great consternation amongst the superstitious locals. He searched for jaguars: 'Jaguar (went out hunting cut trees in each side with claws sharpening'. In his Beagle Animal notes, p. 27, Darwin recounted:

One day, when hunting on the banks of the Uruguay, I was shown certain trees to which these animals are said constantly to recur for the purpose of sharpening their claws. During the day, I saw three well known trees. In front the bark was worn smooth, & on each side there were deep scratches or rather grooves extending in an oblique line nearly a yard in length. The scars were of different ages. To go and examine these trees is a common method of ascertaining whether a Jaguar is in the neighbourhood.

The same lines occur in Journal of researches, p. 160.

Darwin recorded on p. 21 how the men at the estancia could perform extraordinary feats of killing and skinning mares (which they would not ride). In the evening Darwin went on towards Mercedes, and stopped at another estancia, which was in the charge of the landowner's nephew. Together they visited an army captain (See Parodiz 1981, p. 57). There then ensued one of the most delightful conversations recorded during the voyage. The army captain expressed 'great surprise at being able to go by land to N. America'. He then asked Darwin to '"answer me one question truly" are not the ladies of B[uenos] Ay[res] more beautiful than any others"', p. 22. Darwin replied '"Charmingly so"'. The interview continued, pp. 22-3:

One other question do ladies in any part of world wear bigger combs. I assured them not: They were transported & exclaimed "Look there, a man who has seen half the world says it is so. We only thought it to be the case.

The following day Darwin hired horses and 'Passed through immense (no Biscatchas) beds of thistles...often as high as mans head' with 'Very uncomfortable riding', pp. 23-4. The geology was out of the ordinary: 'soon after leaving white mortar rock arrive at bed of white jaspery rock marked with manganese containing nodules of milk agate', p. 25. (See South America, p. 93).

Darwin spent the night of 21 November at a 'small Ranches' then 'arrived very early at the Estancia of Mr Keen on the R Berquelo near Mercedes', p. 26. Almost immediately Darwin made (but at some point deleted) what was perhaps one of his earliest references to the relationships between animals on continents and neighbouring islands: '(are these black rabbits on West Falklands)'. Perhaps this was the subject of a discussion with Mr. Keen, who although out during the day returned that evening.

The following day, the 23rd, Darwin geologized. The next day he rode with Mr. Keen to a place called Perica Flaca, where there was a 15m cliff with extraordinarily coloured sediments containing some bones: 'The question is whether Bone occur in Tosca contemporaneous with Punta Garda [i.e. Punta Gorda] bed, or with Bajada [i.e. St Fé Bajada]', p. 31. Falconer 1937 explained that this section was of great significance as it led to a dispute between Darwin and Alcide d'Orbigny (d'Orbigny 1842). D'Orbigny doubted Darwin's observations, first published in Journal of researches, p. 171, that the white limestone (a marine deposit), first seen at Calera de los Huerfanos, overlay the Pampean Formation.

In South America, pp. 87-95, Darwin was at pains to substantiate his observations. Falconer reported that various geologists had revisited the sites in question in the early twentieth century in an attempt to determine the truth. The majority view was apparently that Darwin was seeing a formation under the limestone which only looked like the Pampean Formation. Falconer praised Darwin's pioneering geological description of the area, however, and he stated that Prof. Karl Walther, of Montevideo, had erected a granite obelisk at what he took to be the key section which he named Rincón Darwin. Winslow 1975 reported that a nearby village was then called called Villa Darwin, but Green 1999, who provides a photograph of the obelisk, states that the local people call it Sacachispas.

Darwin noted that the view of the Rio Negro from the cliff was 'decidely most picturesque for the last four months' and that the river was '2 severn' i.e. twice the width of the Severn, p. 32. On 25 November he 'Rode to dig out bones of giant' which had been found in place but had since washed under water. Richard Owen, in Fossil Mammalia, p. 57, described a rather battered skull as that of Glossotherium, a new genus of ground sloth, and there were pieces of what seemed to be a carapace. Darwin found the circumstances 'Interesting as connection between Casca & big bones', p. 33. Casca most likely meant armadillo-like case, as it is Spanish for 'shell' or 'helmet', and in Journal of researches Darwin reported that he found such a case near the Glossotherium.

The next day Darwin went to a house 'to see large head & bones washed out of Barranca & found after a flood. pieces here also of Casca', pp. 33-4. Winslow 1975 records how the beautiful skull had been used as target practice which had destroyed the teeth and jaw. Mr. Keen played a key role in securing this skull for Darwin for the price of eighteen pence and in arranging for safe shipment of the fossils to Mr. Lumb in Buenos Ayres, who sent them to Henslow in England (see Winslow 1975). The skull was later described in great detail as that of the new notoungulate genus Toxodon by Owen (Fossil Mammalia, p. 16).

Side view of the skull of Toxodon from the Rio Sarandis. Plate 2 from Fossil mammalia.

These pages are of interest with respect to the term 'diluvial', which Darwin gradually dropped during the voyage. On p. 34 he wrote 'most probably diluvial hence animal of Tosca & diluvial age', but then following a 'very bad night wet through; extraordinary thunder', pp. 34-5, Darwin recorded 'Granite in immense blocks' and seems to have changed his mind about the age of the tosca 'The white Tosca bed certainly different from the usual grand covering. Probably of a different date', p. 35.

On 27 November Darwin noted 'country whole distance Primitive gneiss' and on the 28th he 'Arrived in middle of day by same road to Monte Video.', p. 35. The remaining two pages are difficult to date as the next date in the notebook is 18 April 1834. Page 36 appears, however, to be concerned with some fossil bones in the possession of a 'Padre' (clergyman) at Las Pietras (Las Piedras) with a tail which Darwin drew and thought was an 'extraordinary weapon'. This must be the 'dasypoid quadruped' which Darwin mentioned as seeing near Monte Video in South America, p. 107.

Notebook p. 37 is highly significant as it is apparently an ink 'mini-essay' on the perplexing sections Darwin had just seen on the banks of the Uruguay and Negro. This page seems to indicate that Darwin realized that the estuarine conditions which created the Pampean Formation had occurred at least once previously, and that the last two such estuarine periods had been interrupted by a marine phase, thus supporting a view of the geology of the Pampas as one of repeated elevation and subsidence. A few months after his Banda Oriental expedition Darwin took this idea much further in his first of several geological essays written during the voyage. This first essay, which he headed 'Reflection on reading my Geological notes', is now numbered as DAR42.93-96 and was published with analysis in Herbert 1995. Herbert, p. 158, explains how the 'Reflection' essay, which she dates to around March 1834, shows Darwin beginning to speculate on how the elevation might be caused by 'swelling of the Globe', and which might result in land only recently risen from the sea having therefore only a limited stock of animal and plant species (i.e. biodiversity) due to 'no Creation having taken place'.

Darwin's second geological essay is headed 'Elevation of Patagonia' (DAR34.40-60) and since it contains references to Santa Cruz was almost certainly written a few months after 'Reflection', in mid 1834. It picks up on several of the themes in 'Reflection' and is discussed below.

Eight days after arriving back in Monte Video, Darwin set sail on the Beagle on her final departure from the River of Silver, bound for Port Desire and Port St. Julian in southern Patagonia in company with the Adventure. The next notebook entries are for Port Desire on 27 December (Buenos Ayres Notebook, pp. 87-8).

Santa Cruz River, April 1834

By the time the Beagle left the Falklands for the last time, at the beginning of April 1834, Darwin at the age of 25 was beginning to see himself as a geologist. As he wrote to his sister Catherine on the 6th:

There is nothing like geology; the pleasure of the first days partridge shooting or first days hunting cannot be compared to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue....I long to be at work in the Cordilleras, the geology of this side, which I understand pretty well is so intimately connected with periods of violence in that great chain of mountains. The future is indeed to me a brilliant prospect. (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 379).

About ten days after he wrote this letter, Darwin started on what Barlow called 'expedition no. 5', the grueling seventeen day struggle against the fierce flow of the Rio Santa Cruz, in a brave attempt, led by FitzRoy himself, to find its source 300km away in the Andes.

The expedition began on 18 April, with the first entries in the Banda Oriental Notebook on p. 38, and ended on 8 May on p. 103. The Beagle was by then ready to explore the Pacific coast. FitzRoy had chosen the Santa Cruz, with its large tidal range, as an ideal place to lay her ashore and repair some minor damage to the keel and damaged copper sheets, before re-entering tropical waters, 'where worms would soon eat through places on a vessel's bottom from which sheets of copper had been torn away.' (Narrative 2: 283).

'Beagle laid ashore, River Santa Cruz.' Engraving after Conrad Martens from Narrative 2.

The expedition did not achieve its primary aim of reaching the source of the river because the party was forced by dwindling rations to turn back downstream, having come tantalisingly close to Lago Argentino which was discovered, as Barlow 1945, p. 220, remarked, thirty-nine years later. However, the scientific observations made by FitzRoy and Darwin during the course of the expedition amply repaid their exertions and represent the high point of their collaboration. It took just three days for the expedition to return to the Beagle, the three whaleboats which had been so laboriously dragged upstream shooting almost dangerously fast back downstream.

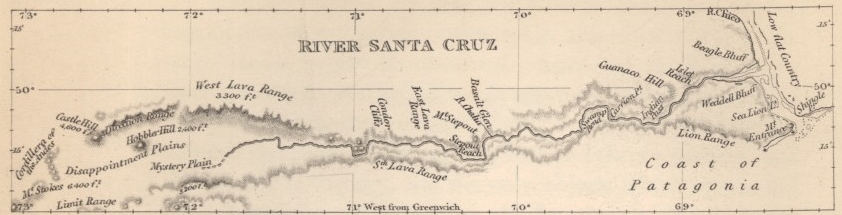

FitzRoy took a particular interest in the Santa Cruz and published a paper on the expedition in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society (FitzRoy 1837). He provided a chart of the mouth of the river and a map of the river itself, showing how it fizzles out in 'Mystery Plain', in Narrative 2: 338-9. FitzRoy seemed to refer specifically to the geology seen and no doubt discussed at length with Darwin on the expedition, in his notorious chapter 28 'A very few remarks with reference to the Deluge', pp. 657-82.

FitzRoy's map of the river Santa Cruz from Narrative 2.

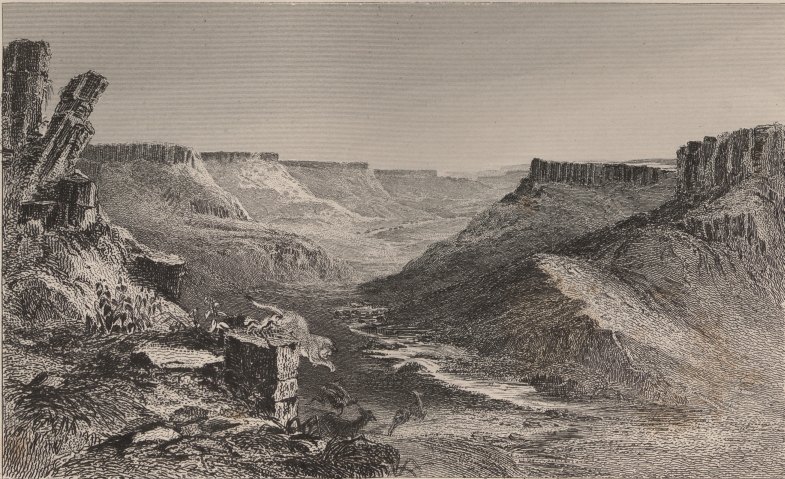

There are several superb drawings and watercolours of the expedition by Conrad Martens, such as 'Basalt Glen' (reproduced in Keynes 1979, p. 205). Some of these are enormously helpful in understanding the geology of the valley, which Darwin covered in South America, pp. 9-14, 112-117. Martens left the Beagle in September 1834 and arrived in Australia in April 1835. When Darwin visited Australia in January 1836 he commissioned Martens to paint a watercolour of the Santa Cruz expedition.

'Basalt Glen — River Santa Cruz.' Engraving after Conrad Martens from Narrative 2.

The Santa Cruz expedition was of great importance to Darwin's understanding not only of the geology of Patagonia but of the geology of the world. By the end of the expedition he had come to see the Santa Cruz river valley as an uplifted channel which was once under the sea, like the Beagle Channel today. This fitted his emerging understanding of the whole South American continent as one which is gradually emerging from beneath the waves due to vertical forces. He was deeply impressed by the vast extent of the several slightly sloping plains which he could trace for hundreds of miles, and this suggested to him a series of successive step-wise elevations on a truly continental scale, linked to the rise of the Andes. This was not exactly, as Lyell might have preferred, gradual elevation at a uniform rate. As Darwin wrote in South America, p. 10:

I think we must admit, that within the recent period, the course of the Santa Cruz formed a sea-strait intersecting the continent. At this period, the southern part of South America consisted of an archipelago of islands 360 miles in a N. and S. line.

It was at the end of the Santa Cruz expedition that Darwin read the third and final volume of Lyell's Principles of geology, and shortly after this Darwin wrote his second geological essay, entitled 'Elevation of Patagonia' (DAR34.1.40-60). (See Herbert 2005, pp. 160-6 for discussion). Darwin cited 'Lyell Vol III P. 64' on p. 109 of the notebook a few pages after the date 25 May; a rare instance where he actually cited what he was reading in the field notebooks. The same page reference occurs in an insertion in his earlier 'Reflection' essay (see Herbert 1995, p. 33 note 39).

Just before this reference to Lyell, on notebook p. 108, Darwin told himself to 'Reread Pampas Notes & copy out' which is perhaps the prompt to write the 'Elevation' essay. Darwin wrote to Henslow in July 1834 and told him how successful the expedition had been, and how 'you may guess how much pleasure [reading Lyell's third volume] gave me'. (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 399).

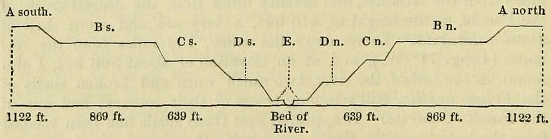

The account of the expedition in the Banda Oriental Notebook opens on p. 38 on 18 April: 'caught mouse: pleasant part cheerful running water'. The next day Darwin made a sketch of the river terraces which is similar to the one published in South America, p. 10, fig. 6 (reproduced below), although the latter represents a higher section through the valley. Darwin may not have been able easily to write while actually on the move, as he reported in what must have been a note made in the evening, 'day has been splendidly fine: but country terribly uninteresting; no living beings. Insects fish &c &c', p. 40.

'North and south section across the terraces bounding the valley of the R. S. Cruz, high up its course.' Fig. 6 from South America, p. 10.

It is not clear whether Darwin was routinely involved in helping to pull the boats. There are several references in FitzRoy's Narrative to Darwin going ahead of the party to scout and to make the best use of his marksmanship, and he was certainly often engaged in helping FitzRoy and John Lort Stokes (1812-1885), Assistant Surveyor, with the mapping of the valley. On the other hand, FitzRoy implies that everyone took their turn, and Darwin in his Beagle diary, p. 233, also says that 'every one' (his emphasis) did so.

By p. 41 Darwin reminded himself to investigate the 'Effect of Earthquake in Chili on river courses'. The party at this point was going beyond what the crew of the Beagle had managed on the first voyage: 'Beyond this Terra Incognita', but they did find a boat-hook lost on the earlier attempt.

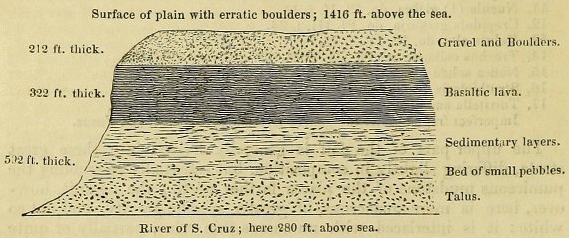

On 21 April they found a huge 'Quartzoic or Feldspathic' boulder, and Darwin eventually cited this and others in his paper 'On the distribution of the erratic boulders and on the contemporaneous unstratified deposits of South America' (Darwin 1842), which included a sketch section through the bank of the river. This section was republished in South America, p. 114, fig. 18 (reproduced below).

'Section of the plains of Patagonia, on the banks of the S. Cruz.' Surface of plain with erratic boulders; 1,416 ft. above the sea. Fig. 18 from South America, p. 114.

Darwin recorded catching a fish which was eventually described by Jenyns (Fish, p. 119) as the new species Mesites maculatus. This fish is now known as the Inanga (see Pauly 2005, p. 92).

There was evidence of Indians keeping track of the expedition, but they were never seen. A dead guanaco was found and eaten by most of the party, although FitzRoy recorded that some of them could not overcome their aversion to carrion.

By 22 April there were five sets of plains. Darwin caught a 'red-nosed mouse', p. 45, and noted having seen a 'Callandra', which was probably the Patagonian Mockingbird Mimus patagonicus. See Herbert 1980, p. 117, note 159. The next day there was a little leisure for collecting beetles. See Smith 1987, p. 80, who quotes the note made against the Santa Cruz entries in Darwin's insect list: 'where no white man probably ever before arrived'.

Darwin noted the 'immense quantity of gravel!' and the going was difficult because of cliffs, so they had to cross to the other bank. On p. 47 he recorded 'many Ostrae & great, red concretions, like at ship:'. On p. 49 occur the first of many barometric and angular readings which allowed him to estimate the heights of the plains, by leaving his shipmates while he went climbing, p. 50. On p. 51 there is a distinct fingerprint on the page, presumably Darwin's.

Darwin was by now fascinated by the regular series of vast plains at increasing altitude: 'My great puzzle. how a river could form so perfect a plain as 2d & cemented even in its highest parts — draining of sea ???', p. 51.

On p. 52 Darwin recorded seeing 'an ostrich about 2/3 size of common & much darker coloured exceedingly active & wild', which was obviously what Gould 1837 would name Rhea darwinii (see introductions to Buenos Ayres and B. Blanca notebooks). On the same page Darwin noted for the first time the lava flows which were such a feature of the higher reaches of the valley.

On the 26th, on p. 54, Darwin made a striking comparison with the volcanic scenery he had seen over two years previously at Port Praya in the Cape Verdes. On p. 55 he was convinced that the landscape 'must be effect of sea', but two pages later 'now I can hardly think this valley was formed & these beds deposited in it at bottom of sea'. An excellent sketch map of the plains occurs on p. 60.

On p. 61 Darwin remarked 'Boat injured bad days work: most interesting geology, distant hills', then follow several pages of geology and 'great hexagon column 12 feet each side', p. 67. He was obviously delighted to have 'Shot Condor! Length 3ft 8in tip to tip 8ft iris scarlet red. Pairs with young ones. Female: magnificent bird: good days tracking', p. 66. These notes eventually contributed to the account he wrote in his 'Ornithological notes', p. 45.

However, geology predominated, with Darwin convinced by p. 69 that the gravel above the lava 'must have been formed beneath the sea'. On the 28th he 'found Indian tripod, first signs of man since the ferry: small grave'. He remarked that the gravel all around made hunting with horses impossible. On p. 73 he drew a diagram showing 'A curious appearance of the lava where perhaps currents met or were stopped. Throwing up several waves. About 2. feet high; & broad as represented from a centre'. These he described in South America, p. 116.

The next day Darwin ascended 'some still higher lava cliffs' where the rock seemed to be different from lower down, p. 76, but still in his view submarine lava. He described the irregular surface of the lava and he noted what he thought to be evidence of 'much diluvial action' in the overlying gravel. On p. 78 he 'saw distant snowy mountains' and in the Beagle diary he recorded how this news was 'hailed with joy'.

On 30 April he recorded more giant boulders: 'one was 5 yards square & about 5 feet deep!', p. 80, and he speculated that 'perhaps the excessive alluvial action. (like St of Magellan?)' was 'consequent on retiring waters from hills formed the inland cliffs?', p. 81. He was puzzled about the beds he had seen containing oysters, and he confessed 'I do not understand the system of plains in this valley'. By now the Cordilleras were 'in full view' and he was very impressed by the vast spreads of porphyry pebbles which he guessed were from the mountains: 'How immense the period during which this bed of pebbles were formed', p. 87.

In his Journal of researches, p. 218, Darwin criticised former geologists who, in trying to explain the erosion of the lava and other rocks of the valley,

would have brought into play, the violent action of some overwhelming debacle; but in [the case of the Santa Cruz] such a supposition would have been quite inadmissible; because the same step-like terraces, that front the Patagonian coast, sweep up on each side of the valley. No possible action of any flood could have thus modelled the land in these two situations; and by the formation of such terraces the valley itself has been hollowed out....we must confess it makes the head almost giddy to reflect on the number of years, century after century, which the tides unaided by a heavy surf, must have required to have corroded so vast an area and thickness of solid rock.

By 1 May the going was very tough, and Darwin was intrigued to find petrified wood which he thought came from the same bed as the oysters: 'if Palms from Lat 50 very interesting', p. 90. Pebbles were of sizes 'from walnut & apples & some as big as 2 fists', p. 91. He felt ready to imagine a scenario for the formation of the valley: Perhaps plains and opening at head of river, might be explained by a strait, at very first elevation water in mountain cut it through in the channels, & so on till elevation stopped the passage & river commenced', p. 93.

On 2 May the Andes were 'in view all day' but the river was 'very tortuous', p. 94. Darwin recorded the peculiar way that guanacoes revisit the places where they have left dung; published this observation in Journal of researches and referred to it in Natural selection, p. 522. There were great blocks of slate and ancient conglomerate and Darwin could 'see a gap in the mountains', p. 97. By now he was sure that the plains had a marine origin. On the 3rd there were 'signs of Indians' such as a pointed stick and some ostrich feathers. By the 4th the Captain decided to take a party of fifteen armed men a few miles further but supplies were low and it was 'very cold' so they could go no further. They began their descent down the river on the 5th and on that one day covered the ground it had taken them '5 & 1/2 days tracking' to ascend, p. 101.

6 May was a 'pleasant day' with 'many guanacos' and 'many ostriches', and since the latter had not often been seen before this was 'proof of extreme wildness', p. 103. On the 7th Darwin drew a sketch section of the valley, and on the next day they 'arrived on board' the Beagle, which as Darwin records was 'repaired. False keel masts up' and describes in his Beagle diary as 'fresh painted, & as gay as a frigate'.

A gap of four days follows in the Notebook which is partly covered by a some entries in the B. Blanca Notebook, while Darwin and various crew members 'killed a lion & curious wild cat & 2 foxes & condors', p. 107. The 'curious wild cat' was probably the Gato payaro, described thus in the Beagle Animal Notes: '2036 Cat. In a bushy valley, when encountered, did not run away but hissed. S. Cruz, Patagonia.'

Felis pajeros, the Pampas cat, was described by Waterhouse in Mammalia, p. 18. The Santa Cruz specimen is mentioned by Darwin in his 'Reflection' essay, see Herbert 1995, note 38.

Felis pajeros from eastern South America. Plate 9 from Mammalia.

Tierra del Fuego, May 1834

On 12 May they put to sea 'hunting for L'Aigle rock' and the weather was severe. Darwin was 'sea sick as usual & miserable'. On the 16th they anchored 'close outside C. Virgins', p. 107. Keynes 2003, p. 229, explains how Darwin here found a new species of bryozoan (Caberea minima) which he called a Coralline and which showed some extraordinarily complex anatomy and behaviour.

The next entry in the Banda Oriental Notebook is dated 25 May in Tierra del Fuego and Darwin reminded himself to 'Reread. Pampas notes & copy out Gen observation Color T. del F map', p. 108. Perhaps the map referred to is the one now in DAR44.13 which was published in colour by Herbert 2007, p. 315.

On p. 109 Darwin noted Lyell's discussions of gypsum ('Vol III P. 64') and of Etna ('P. 77'), both references transferring directly to the 'Reflection' essay, see Herbert 1995, p. 33, note 39. Darwin also quoted Lyell's new word 'hypogenes' for the first time. See Pearson 1966 and the introduction to the B. Blanca Notebook.

There is then a long gap of blank pages in the notebook until on p. 240. There seems to be some field notes from the Santa Cruz expedition, as Darwin was clearly discussing the 'old diluvium' and 'new diluvium' which were the Pampas beds below and above the lava respectively, p. 241. There is a reference to the same boulder mentioned on p. 88, indicating that p. 241 was written on 1 May.

As Darwin reported to Henslow in the letter from July 1834, two months after the Santa Cruz expedition and just into the second half of the Beagle voyage, his scientific notes (i.e. the notes he wrote up on ship, not his field notebooks) amounted to some 600 foolscap pages. Up to this point in the voyage the geology and zoology notes were almost equally long, indicating that up to this point Darwin saw himself as much a zoologist as a geologist. Clearly he did not see himself as a botanist, as apart from specimen lists, Darwin did not keep separate botanical notes during the voyage.1

The Santa Cruz expedition contributed significantly to Darwin's emerging perception of himself as a geologist, as it was in the months after the expedition, during the southern winter of 1834, that he started to generate far more geology notes than zoology notes. By the end of the voyage there were about four times more geology notes than zoology notes: 1,383 geology pages, mainly in DAR32-8, compared to 368 zoology pages in DAR29-31; see Gruber and Gruber 1962. Having walked from the Atlantic to within sight of the Andes, and having unraveled at least in his own mind a very plausible geological history for the southeast part of South America, Darwin was beginning to formulate a grand theory linking elevation to mountain building.

As Pearson 1966 and others have pointed out, a key part of Darwin's success was his ability to see how a series of observable phenomena, if reiterated for sufficient time, could produce profound changes. Darwin achieved such a vision during the voyage in his understanding of the bewildering variety of igneous rocks, and in his brilliant explanation for the gradual series of coral reef formations.

The investigation of the Santa Cruz valley revealed how the southern portion of South America was rising from the sea due to massive subterranean forces, so that what began as a chain of islands was becoming successively a range of mountains and ultimately a continent. This sequence due to elevation ought, according to Lyell's view, to be compensated for by a reverse sequence, as some other hypothetical region of the world gradually subsides beneath the waves. It is evident in the Santiago notebook that before Darwin even left South America he seems to have realised that the Pacific Ocean would provide evidence of just such subsidence of the sea bed.

Gordon Chancellor and John van Wyhe

August 2008

'Banda Oriental S. Cruz.' Beagle field notebook. Text EH1.9

1 Beagle plants estimates that approximately 20% of Darwin's notes from the voyage are on botanical subjects. It is interesting to note that Darwin's scientific life may be seen as a gradual transition from geologist (1830s-1840s), to zoologist (1840s-1850s), to botanist (1850s-1870s). Although he claimed he never considered himself a botanist, in the latter decades of his life Darwin published a whole series of books on plants and made many fundamental contributions to plants science (Allan 1977).

RN7