Introduction to One hundred wonders of the world (1821)

Gordon Chancellor

In his Autobiography of 1876 Charles Darwin recalled that: "…early in my school-days a boy had a copy of the Wonders of the World, which I often read and disputed with other boys about the veracity of some of the statements; and I believe this book first gave me a wish to travel in remote countries, which was ultimately fulfilled by the voyage of the Beagle." (Autobiography, p. 44).

From the age of nine in 1818 Darwin boarded at Shrewsbury School1 until he left to join his brother at Edinburgh University in 1825, so his memories of Wonders of the World2 (PDF) probably date to around 1820. The significance of this book (hereinafter simply called Wonders) to his early development appears never to have been fully explored by Darwin scholars. How wonderful it would be if the actual copy he remembers was ever located.

Wonders was one of many by the prolific author and publisher of books and periodicals Sir Richard Phillips (1767-1840), a remarkable self-made man in his own right.3 As a young man he had planned to help in the rebellion against the Spanish in South America, leading to a lifelong interest in that continent about which he wrote at least two books. Politically he was a radical and an enthusiast for the French Revolution of 1789. In 1793 he was imprisoned for selling Thomas Paine's Rights of Man (1791-1792). He was also fiercely vegetarian and seems to have been an unorthodox businessman, prone to bankruptcy and some of his scientific views were distinctly odd, for example he had his own anti-Newtonian theory of gravity. Phillips published some of the books which Darwin read on the Beagle, including Josef de Vargas Poncé's Relacion del ultimo viage al estrecho de Magellanes (1788 PDF). Apart from Wonders, perhaps his own most significant book was A million of facts (1832), of which he announced in the 1840 edition that 'nothing else in literature…can compete with 9000 FACTS FOR A PENNY'. He numbered many radicals in his lists, including Humphry Davy, William Godwin and Samuel Coleridge, although he declined to publish Lord Byron and Walter Scott.

Richard Phillips, by James Saxon 1806 (National Portrait Gallery)

Wonders was a typically entertaining and informative book from Phillips's stable, in line with his passion for free public education and libraries. It is not a particularly rare book although there is no copy in Darwin's Library. It is not entirely clear when exactly the first edition appeared although it seems to have been in 1818. It went through at least 40 editions up to 1844, notwithstanding the cheap paper it was printed on.4 In 2010 Cambridge University Press reprinted the 1834 edition, attributed by that time to Phillips himself and originally published by Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper. The 'blurb' for this reprint describes the Wonders as: 'A vast and heterogeneous survey, which compiles natural and man-made curiosities across the world. The Himalayas and Mont Blanc share a chapter with the Peak of Derbyshire; famous rivers lead to mysterious subterranean forests; and Stonehenge is closely followed by St Paul's cathedral. Halfway between reference book and textbook, this richly illustrated volume is a fascinating catalogue of the world's wonders as perceived in the early nineteenth century.'

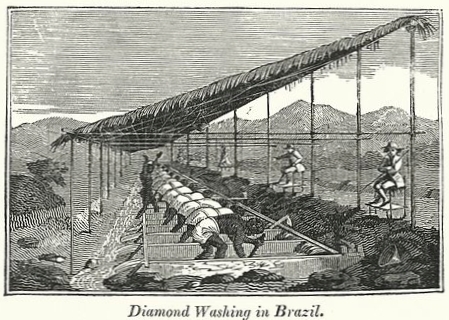

My own copy (which provides the page references cited here) is the 13th edition of 1821.5 It has 661 pages, plus adverts for Phillips's other educational books. Somewhat bizarrely, in 1821 the prolific French composer and author Catherine Joseph Ferdinand Girard6 published Les merveilles du monde, ou les plus beaux ouvrages de la nature et des hommes, repandus sur toute la surface de la Terre; ouvrage destine a l'instruction et l'amusement des jeunes personnes de l'un et l'autre sexe. That book is extremely similar to Wonders and covers almost identical subject matter, so the two books must be connected. Many of the plates, for example of St Peter's in Rome and of Brazilian slaves washing for diamonds (taken from Mawe 1812, see photos below), are identical.

Illustrations of slaves washing for diamonds in Brazil. The original is from Mawe (1812 Text) and is used in Wonders (1821) and in Les merveilles du monde (1821), see note 6.

Phillips published many books under pseudonyms, including Wonders which has the by-line 'Rev. C.C. Clarke',7 and Phillips also quotes extensively from his own remarkable A morning's walk from London to Kew (1817). Phillips makes many references to the 'interesting Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa' (p. 570) of 'the learned Dr Clarke'. We believe there is no connection between the apparently fictitious 'Rev. C. C. Clarke' and the real 'Dr Clarke', although of course there might be.

We have had some difficulty identifying the real Dr Clarke because there are two obvious candidates. The most likely is Edward Daniel Clarke (1769-1822) who certainly published the 'Travels' referred to by Phillips.. He was Professor of Mineralogy until his death in 1822 when Darwin's mentor Henslow was appointed as his replacement. The second candidate is Edward's brother James Stanier Clarke (1766-1834) who served in the Royal Navy and travelled extensively before becoming King George IV's Librarian. James has the distinction of having persuaded Jane Austen to dedicate her anonymous 1816 novel Emma to the then Prince Regent, which must have pleased John Murray8 – her publisher – no end!

To confuse the issue further, Phillips refers several times in Wonders to the exploits of a 'Captain Clarke' whose accounts of amazing places, including Kamchatka, feature strongly in the book. We believe that this gentleman was actually the famous Charles Clerke (this time with two 'e's) who sailed with Byron in the Pacific (1764-1766). Clerke claimed to have seen 'Patagonian giants' on the voyage, as in reports going back to Magellan's expedition in the 1520s, although their height was revised down to 6' 6" (1.98m) in the published account of 1773. Clerke later sailed on all three of Captain Cook's voyages (1768-1779) and took over command of the third voyage when Cook was killed in Hawaii in 1779. Clerke himself died of TB in Kamchatka later the same year.

The range of topics in Wonders is huge and includes many 'wonders' which Darwin encountered both before the Beagle voyage (1831-1836), such as Cader Idris in Wales and the River Severn in Shrewsbury (p. 362), and during thevoyage. In fact, Phillips's very first 'wonder' is The Andes, concerning the geology of which (on publication of South Americain 1846) Darwin became the world's second foremost authority (after Humboldt). The book features many topics which were of the highest importance to Darwin, such as 'geological changes of the Earth' (p. 208), coral reefs (p. 239), the fossil vertebrates described by his hero Cuvier (p. 223), the 'orang outan' (p. 489), bees (p. 508) and 'zoophytes' (p. 517). These were all topics which Darwin studied in great depth and were crucial to his emerging views about how life on Earth evolved. There is even a section in the book on 'the connexion of earthquakes and volcanoes' (p. 182) which is remarkably similar to the title of Darwin's longest paper on South American tectonics (as we call it today). (Darwin 1838 Text) Phillips also cites many of the great explorers and men of science whom Darwin referred to in his Beagle publications, notably of course Humboldt and Cuvier but also Juan, Kotzebue and Ulloa.

It is probably fanciful to imagine that Darwin was teased by his schoolmates about - but secretly proud of - the book's several quotations from his grandfather Erasmus's poems. Was the young Darwin so struck by his grandfather's lines from Loves of the plants (1791) on p. 69 that they sparked his lifelong quest to understand the role of sex in evolution? Because Darwin never explicitly mentioned Wonders in any of his writings (apart from his Autobiography) and there is no record of him owning or even re-reading a copy, we can only guess what impact it had on his life, although the fact that he remembered it fifty years after leaving school surely proves its importance. The only known 'reference' he ever made to it, albeit obliquely, is in a letter to his old school friend Charles Whitley of 23 November 1838 and now in Shrewsbury School archives: 'This is a marvellous world we live in, & I never cease marvelling at it. But just at this present time I marvel more at the prospect of having a real, live, goodly wife to myself than at all the hundred wonders of the world (emphasis added).' (Correspondence, vol. 2, pp. 125-6.)

February 2025

NOTES

1 Darwin's acquaintances at the School included (with years registered) the following boys who it is known had some contact with him or his family in later life: Jonathan Cameron (1823-1826), Richard Corfield (1816-1819; helped CD in South America), E. H. Cradock (1825-1828; there were two Craddock brothers, George and Thomas, at the School at the same time so it is not clear which one signed himself as E. H. Cradock. None are listed in CCD), Charles Hughes (1819-1825; helped CD in South America), Henry Johnson (1821-1825), Henry Pearson (1818-1823), John Price (1818-1822), Charles Whitley (1821-1826; see letter quoted above, now in the School Library). E. H. Cradock's recollections of Darwin are in Cambridge University Library DAR 112.A16-A17, Johnson's are in DAR 129 and Corfield's are in DAR 29.3.78. Given that CD says he read Wonders "early in my school-days" it seems unlikely that its owner was Cameron or either of the Cradock/Craddocks. Perhaps the fact that they both like CD travelled to South America as young men suggests that Corfield or Hughes are the likeliest book owners! We are very grateful to Naomi Nicholas, Archivist and Head of Special Collections at the Taylor Library, Shrewsbury School, for researching Darwin's school acquaintances for us and for sending us photos of the 1818 intake register.

2 The full title of the book was The hundred wonders of the world, and of the three kingdoms of nature, described according to the latest and best authorities, and illustrated by engravings. This was slightly changed for the 1834 edition to A hundred wonders of the modern world and of the three kingdoms of nature: described according to the best and latest authorities and illustrated by numerous engravings.

3 See the entry for Phillips by Pamela Clemit and Jenny McAulay in the Oxford dictionary of national biography. He is unlikely to be confused with the eponymous movie about Captain Richard Phillips, whose container ship was highjacked by pirates off Mogadishu in 2009, played by Tom Hanks (2013).

4 There are nine copies of the first edition listed on the JISC Library Hub and the Hathi Trust have online the first American edition of 1821 (published by Babcock & Sons of New Haven). Harvard College's 1821 American edition is on Google books and the Biodiversity Heritage Library has the 1825 18th edition. Herbert (2005) cites an Irish edition published by B. Smith in 1825.

5 This copy was owned by the Edwardian writer Evelyn St Leger (Savile) Randolph (1861-1944).

6 Otherwise known as Le Chevalier de Propiac.

7 Not to be confused with (but possibly inspired by) John Keats's oldest friend, the Shakespeare scholar Charles Cowden Clarke (1787-1877). See Roe (2012).

8 Thomas Egerton (1750-1830) published Austen's Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813). John Murray I (1778-1843) published Austen's Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1816), Northanger Abbey (1817) and Persuasion (1817), these last two after her death, as well as Lord Byron's poems and Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830-1833). His son John Murray II (1808-1892) published most of Darwin's books after 1845, including The Origin.

RN3