'Cinnamon and port wine': an introduction to the Rio Notebook

When on board H.M.S. 'Beagle', as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species – that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers.

Origin of species, p. 1

With these words Darwin began his great work. He was referring to the lasting impression from encountering fossil bones of extinct mammals which were clearly similar in certain characters, such as bony armour, to living local species. Darwin was rapidly becoming familiar with South American creatures, such as the armadillo, which has bony armour, so the similarities between the fossil animals and the living ones were apparent and very curious. It is remarkable that this realisation dated from a very early stage in the voyage, in fact to September 1832, nine months after leaving England. In the Rio Notebook we find the absolute primary record of these first truly momentous encounters.

Darwin's Rio Notebook dates from 1832. Its name refers to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It covers Darwin's first serious work on the geology of the eastern side of the South American continent and records many of his rapidly evolving interpretations of what he saw. It also covers Darwin's first excavations of fossil mammals, several of which were of species new to science. Consideration of the links between these fossils and living species was one of the three main kinds of evidence that later convinced Darwin that life evolves. The fossils generated considerable excitement when they were unpacked in Cambridge and displayed at the British Association meeting in 1833, news of this reached Darwin, via Henslow, in March 1834. The fossils themselves were all described by Richard Owen in Fossil Mammalia (1838-1840).

Broadly speaking, the Rio Notebook covers April and the second half of 1832. The first entries date from the Beagle's arrival in Rio de Janeiro in April. Almost half the notebook is devoted to Darwin's first inland expedition (after which the Cape de Verds Notebook came back into use temporarily to cover the next six weeks of Darwin's stay in Rio, up to mid June.

Rio de Janeiro, April-June 1832

The first forty-one pages used in the Rio Notebook deal with Darwin's expedition to Patrick Lennon's estancia c. 250km ENE of Rio, with Darwin in 'a perfect hurricane of delight', see Correspondence vol. 1, p. 232. This first part of the Rio Notebook was exceptionally well covered by Barlow 1945, pp. 158-165. Darwin described the expedition at length in his Beagle diary which became an instant classic of travel writing when published as his Journal of researches.

The expedition started on 8 April 1832, p. 1b. Darwin had five travelling companions, including Lennon, who turned out, on reaching his estate, to be capable of great cruelty to his slaves. Darwin recorded the temperature at the start of the expedition as 104° F. in the shade at 3pm. There are pages of delightful descriptions of the forest. The phrase 'wonderful, beautiful flowering parasites' was quoted verbatim by Darwin from his 9 April entry, p. 9b in his Beagle diary and Journal of Researches and then he suddenly recorded the horrors of feeling seriously ill when a long way from home, p. 13b. Luckily, the next day, the 12th, 'Cinnamon and port wine cured me', p. 14b.

Darwin and his rather unsavoury fellow travellers stayed at the Socego [Sosego] coffee plantation for two nights before proceeding to Lennon's estate. On p. 16b Darwin attempted a sketch of the layout of the rooms at the Fazenda, which he described in his Beagle diary. He seems to have been rather taken with a certain Donna Maria, p.17b, the daughter of the Fazenda's owner Manoel Joaquem da Figuireda, and impressed by the conditions in which the slaves were kept.

The dangers of travelling so far from home are poignantly suggested by the way Darwin scratched out very emphatically the word 'villain' on p. 19b, presumably for fear of the entry being seen by Mr Laurie, the 'selfish, unprinciples man' referred to in the Beagle diary to whom the word applied. Darwin arrived at Lennon's estate on 15 April, p. 23b. He arrived back via the same route at Praia Grande in Rio on 23 April, p. 38b. Many of Darwin's books, instruments and gun cases were damaged by a swamping in the surf when Darwin moved into a cottage in what is now Rio's South Zone at Botofogo [Botafogo] on 25 April, p. 39b. But he clearly enjoyed the company there of some English gentlemen and their families, such as the Astons, p. 41a.

At this point, Darwin switched to the Cape de Verds Notebook for six weeks, until the Rio Notebook came back into use in mid June. Considering the two notebooks together we begin to see how Darwin became fascinated by the 'Primitive' metamorphic rocks around Rio. He noted, Cape de Verds Notebook, p. 77b; Rio Notebook, p. 41b the 'enormous blocks' at Tajeuka of gneiss caught up within another type of gneiss, but both types foliated in the same direction and cut by a dyke of granite, which are described in Volcanic islands p. 132 and South America p. 427. Unusually for Darwin, he shied away from attempting any explanation for this complex field relationship.

This part of the Rio Notebook covers the quite extraordinary occasion in Rio on 23 June when Darwin collected sixty-eight species of beetles in one day, Journal of researches, p. 38; see Darwin's insects, p. 58. Unfortunately his field notes are very sketchy for that week, and are most notable for the sketch on p. 43b of the gneiss mentioned above which strangely resembles a sketch of two human figures. If this is so, it may be Darwin's only surviving self-portrait.

The Beagle left Rio for Monte Video on 5 July, p. 47b. Darwin was seasick much of the next twenty-one days of sailing when the weather was bad, such as the terrible gale of 15 July, p. 49b, and he made a sketch of an unusual halo in the sky, p. 48b. He also recorded a Grampus whale, porpoises and flying fish, and on quieter days he wrote many now famous letters to his family, to old College friends and to Henslow.

The number of pages of the Rio Notebook covering the whole period from June to December 1832 is approximately equal to those used only for the April expedition, and this reflects the long periods when the Beagle was cruising up and down the coast, as the cool southern winter gradually gave way to the spring and summer. These cruises took Darwin from Rio down to Monte Video [Montevideo], 5-26 July, from Monte Video down to Bahia Blanca, 19 August-6 September, Bahia Blanca back to Monte Video and Buenos Ayres, 19 October-2 November and finally from Monte Video down to Tierra del Fuego, 26 November-16 December. On this last cruise Darwin had the new second volume of Lyell's Principles of Geology (1832) to read between bouts of seasickness.

Monte Video, July-August 1832

The Beagle arrived in Monte Video, in what was then the province of Banda Oriental [Uruguay] on 26 July, p. 52b, and stayed there until 19 August. In Monte Video Darwin immediately made notes on the mica slates and schists and did a sketch of Rat Island, p. 55b. His descriptions were eventually described in South America, pp. 145-7. On pp. 57b-59b he uses the word 'entangled' or 'intangled' at least three times, see introduction to Cape de Verds Notebook.

The Beagle crossed the Rio Plata to Buenos Ayres on 1 August but was prevented from landing by a quarantine for cholera, so Darwin spent more time collecting and geologizing in Monte Video. He was also caught up in the insurrection during the second week of August, but the notebook is silent on this. On p. 62b he mentioned the 'Capincha' (i.e. Hydrochoeris hydrochaeris) he shot on 15 August, see Zoology notes, p. 67, after which there are no entries until 22 September.

Bahia Blanca, September-October 1832

The Beagle left Monte Video for Bahia Blanca in Patagonia [now Argentina] on 19 August arriving there around 6 September, staying until about 17 October. It was during this period that Darwin first experienced the thrill of unearthing with his own hands fossil bones. This feat took three hours of hard labour, but was only the beginning of a process of packing up and shipment to England, research and eventual publication in Fossil mammalia. On pp. 63b-64b he recorded the cliff section and on the very next page made a momentous entry:

in the conglom[erate of pebbles and shells] teeth and thigh bone. Proceeding to the NW – there is a horizontal bed of earth, containing much fewer shells, but armadillo – this is horizontal but widens gradually hence I think conglomerate with broken shells was deposited by the action of tides earth quietly

This was a very significant discovery. Darwin was wondering if the conglomerate containing sea shells and bones had been formed in an estuary environment and was not a relic of some catastrophe.

When back on ship writing up his geological diary Darwin noted that it was 'impossible to behold [the conglomerate] without immediately saying that it is the mass of earth which a debacle tearing across the country would deposit' (DAR32.53). He also remarked: 'Some geologist [sic] have been surprised that the extinction of land-animals, has not occurred, without the destroying the inhabitants of the sea; this would seem to be a case in point' (DAR32.71-2). These important manuscripts need closer study, and we will return to a more detailed discussion of the fossils in the introduction to the Buenos Ayres Notebook.

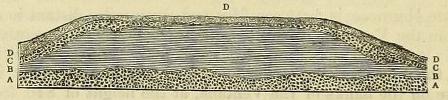

Darwin went back to his original field notebook view of Punta Alta seven years later in his Journal of researches, p. 95, and then in much more detail in South America, p. 82 et seq. where he published a woodcut version, see below, of the section drawn on notebook pp. 73b-75b, see also Herbert 2005, p. 100 for an intermediate state of this section and Manera de Bianco 1993 for a brief account of Darwin's section at Punta Alta as it is today. In South America the mollusc species, plus a barnacle and two coral species, were identified by that other great South American explorer, Alcide d'Orbigny (1802-1857), as species still living on the same coast. By that time Richard Owen had described and named all the mammal fossils from the voyage in Fossil mammalia and had proved beyond a doubt that most were extinct species, such as the Megatherium cuvieri referred to on p. 81a, closely related to the present day mammals of South America. Even today we are not sure why these species became extinct – although the arrival of North American predators and later of humans seems likely at least in some cases – but the point for Darwin was that a general catastrophe would surely have killed the marine species as well as the mammals.

SECTION OF BEDS WITH RECENT SHELLS AND EXTINCT MAMMIFERS, AT PUNTA ALTA IN BAHIA BLANCA.

In one of Darwin's first scientific papers, 'A sketch of the deposits containing extinct Mammalia in the neighbourhood of the Plata' read to the Geological Society on 3 May 1837, he referred to Bahia Blanca and indicated that he had accepted a gradualistic Lyellian explanation for the extinction of the mammals. He also accepted Lyell's view that species have 'life spans' and that molluscs have longer life spans than have mammals; he also stressed the universality of this 'law' which applied to South America as well as to Europe. On Lyell's view of species life-spans see Rudwick 2005, p. 98 et seq. and the introduction to the Banda Oriental Notebook.

On p. 79 there is a tiny drawing of a ship which occurs in a sketch map of Punta Alta. This ship is almost certainly the Beagle.

Monte Video, November 1832

The Beagle left Bahia Blanca for Monte Video on 19 October, arriving back at Monte Video around 26 October, then from Monte Video on 30 October to Buenos Ayres arriving there for the first time on 2 November, where the Buenos Ayres Notebook was used for one week. This apparently trivial point gains importance when considering J. W. Judd's firm belief that Darwin first became aware of the potential relevance of his fossils to the species question in November 1832, Judd 1909, p. 353.

It appears that the last pages of the 'back' sequence of the Rio Notebook, i.e. pp. 85b-86b, relate to Monte Video around 14-26 November, as they contain discussion of cleavage, but it is difficult to be sure. There is nothing in the Rio Notebook which obviously relates to Buenos Ayres. The Beagle was back in Monte Video on 14 November and Darwin probably received his copy of the second volume of Lyell's Principles there on 24 November.

Lyell focused in the first volume on the geological causes now in operation on the Earth's surface, but in the second volume he shifted focus to biological causes. So just at the time that Darwin was pondering on his extinct mammals, he was able to read Lyell's masterful review of all the evidence for the 'transmutation of species', which if it occurred would be a possible explanation for the fact that extinct species seemed to be replaced by new ones. Lyell examined the then current theories of transmutation, especially those of Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829), in order to reject them as untenable. Darwin might, therefore, have been disappointed that Lyell made no serious attempt to explain the origin of new species.

Tierra del Fuego, December 1832

The last entries in the Rio Notebook, i.e. pp. 19a-20a, which relate to Tierra del Fuego, tail off towards the end of 1832, although remarkably there is mention of three Australian places on p. 16a, Port Stephen, Jervis Bay and Bald Head. The last dated entry is for 20 December, before the Buenos Ayres Notebook takes over. Most of these pages have been excised and have not been found, unless they include those now in DAR35.328.

Gordon Chancellor and John van Wyhe

August 2008

'Rio de Janeiro excursion city. M. Video Bahia Blanca' (4.1832, 6.1832-10.1832). Text EH1.10 [English Heritage 88202330]

RN15