Charles Darwin's Address Book

An introduction by John van Wyhe

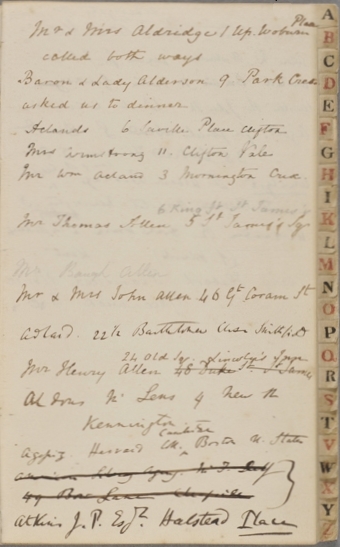

Published here for the first time, Darwin's Address Book is a fascinating document full of new information. The small 17x11cm brown leather-bound notebook is 48 pages long, with about 500 entries, and 4,300 words. Although undated, the entries were begun by Emma Darwin shortly after their marriage in January 1839 as the Darwins began their married life together in a rented house at 12 Upper Gower Street, London.

The entries at the start of many pages are therefore in Emma Darwin's pleasant rounded handwriting and refer to London friends, family and social visits in 1839-1840. Darwin wrote almost all other entries and used the Address Book to the end of his life. His handwriting is sometimes extremely difficult to read. The Address Book has been fully transcribed and enriched with notes and identifications to make it accessible and intelligible. Very many of the people and things in this little book occur nowhere else in Darwin's writings and have been identified here for the first time.

|

|

| The London house, 1839-1842. | Down House, Darwin's home from 1842-1882. |

Forgotten context

Address books are so obvious and familiar today that one would think they have always been around and need no explanation. But they were new in 1839. They didn't exist when Darwin was born in 1809 and both the concept and even the phrase 'address book' were changing from earlier meanings. Before this time an 'address book' was what today would be called a 'visitors book'. Indeed, this notebook does not have 'address book' anywhere on it. Instead, the spine is embossed with "VISITS ADDRESSES". It had no maker's label which was not uncommon.

With its exposed index-letter tabs printed in alternating black and red along the outer edge, Darwin's Address Book is so instantly recognisable to us today that it's difficult to appreciate that this was a recent innovation in 1839.

The word 'VISITS' on the spine betrays the older usage- keeping track of social visits in polite society. This is how Emma Darwin used the book initially, for example in an entry like this:

Mrs & Miss Shepley 2

128. Devonsh. Pl.

called on us. Called there Mar 13

A 'visiting card' could be left behind if someone was not at home, or handed over if they were. The name and address could then be copied into one's book. In earlier times, before printed cards, visitors would enter their name and address in the 'address book'.

'Address books' in the modern sense emerged around the time the penny post and first postage stamp (1840) came into use. Queen Victoria had only begun her reign two years before. Darwin used the book as an 'address book' in the modern sense as well as a place to take notes on a huge ranch of topics as he often used any paper within reach to record information.

The only references to an address book by Darwin that have been found in letters written on holiday saying he did not have an address book with him. Yet Darwin's surviving correspondence includes almost 2000 people, many more than are listed in this book.

Paper revolution

In the early 19th century when this notebook was manufactured, Britain had begun producing factory-made paper in industrial quantities and varieties unprecedented in human history. There followed an explosion of new kinds of paper products, many of which are still familiar including pocket almanacs (see Darwin's: 1839, 1840, 1847), pocket diaries/calendars (Darwin's 1826, Emma Darwin's 1824-1896) and notebooks sold with blank pages such as W. D. Fox's 1826 diary, Darwin's Beagle field notebooks, his 'Journal' (1838-1881) and the famous notebooks (1837-1841) in which he developed his theory of evolution. This Address Book came into use in the midst of this incredibly productive period of notebook use. Out of the jumble of little notebooks Darwin had at this time, only the 'Journal' and Address Book remained in use for the rest of his life.

New insights

What is perhaps most interesting about Darwin's Address Book is that there are so many people and other things not otherwise known in the vast literature on Darwin, especially after the 50-year-long Darwin correspondence project which produced thirty meticulously edited volumes which identify many thousands of people, publications and events. It is usually forgotten, however, that although the Correspondence of Charles Darwin includes almost 15,000 letters to and from Darwin, these are the surviving letters. Many thousands more once existed. Less of a surprise but nevertheless fascinating are the huge range of types of people included from wet nurses, cleaners, insect cabinet makers to lawyers, MPs and other men of science such as Alfred Russel Wallace.

This Address Book is a remarkable piece of social history which contains much more than names and addresses. It reveals many details about the life of a prosperous middle-class Victorian family and a private side of Charles Darwin. For example, it contains unique references to the Gardeners' Chronicle and Athenaeum that Darwin used for research as well as recipes to preserve fruit and especially on how to make rat poison. He noted recipes for cleaning animal skeletons for his research, how to make paste for scientific labels and ordering peat. This was likely to use as a soil conditioner in the gardens and to grow carnivorous plants in his greenhouse at Down House.

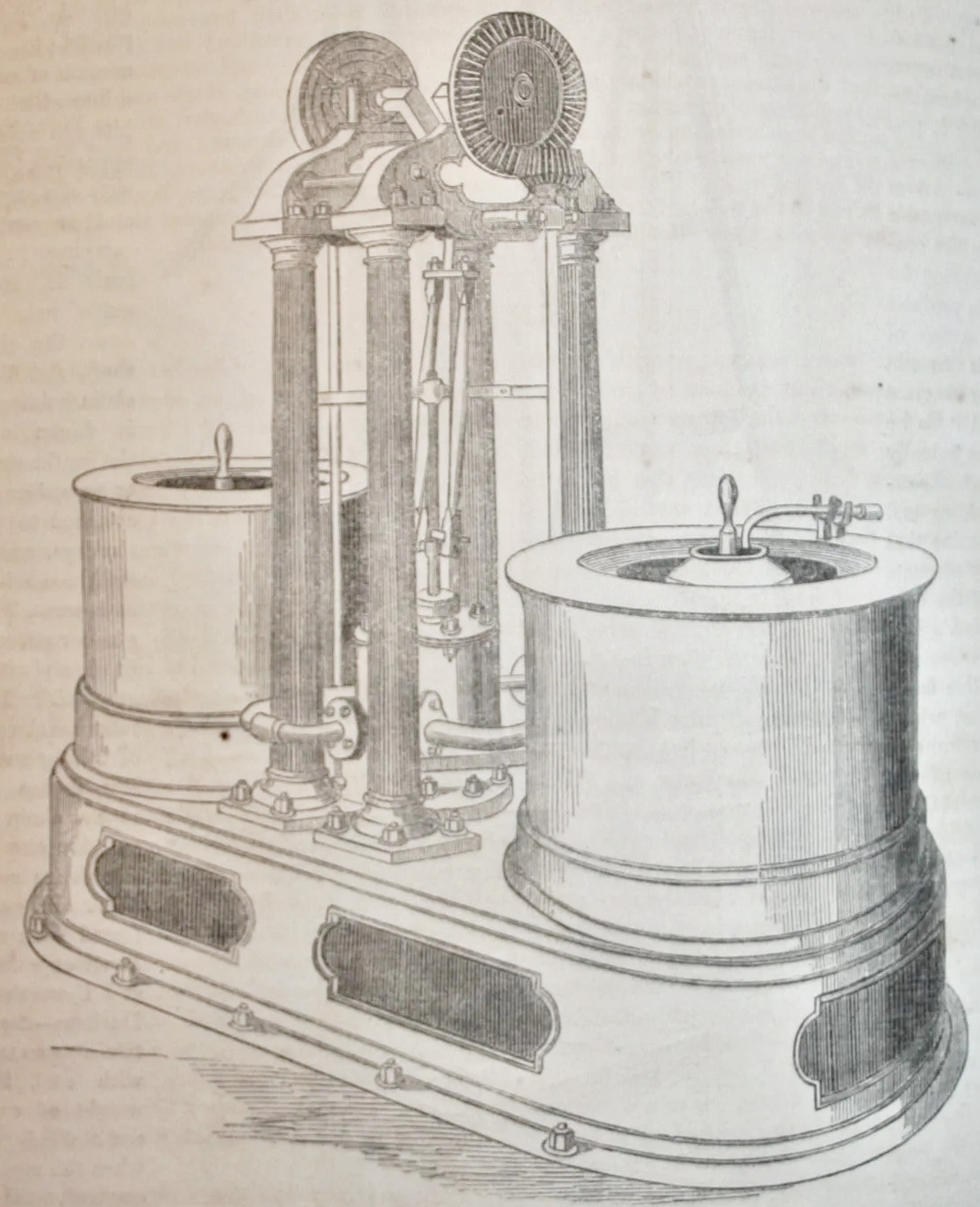

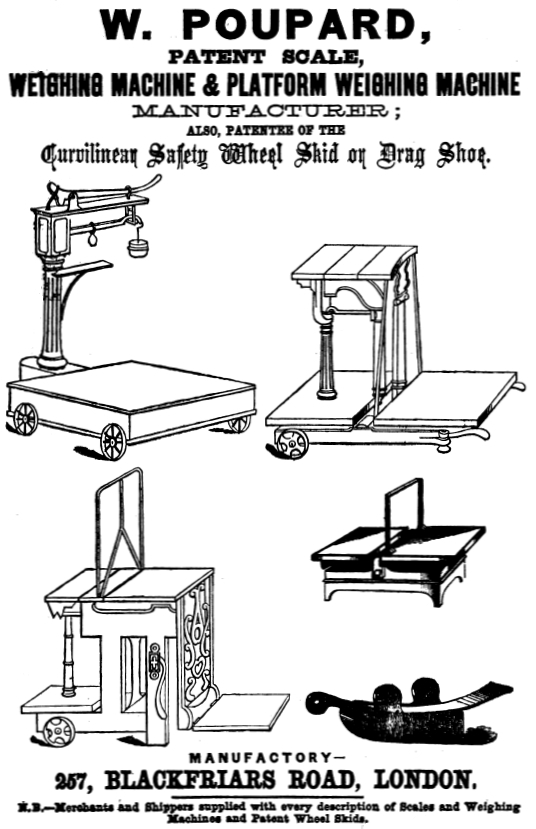

There are details for grocers, laundresses, tobacconists, piano tuners, dentists, tutors, dancing teachers, chimney sweeps, and details on where to order oranges, potatoes, coal, ice, a Shetland pony, papier mâché houses, razors, watch repairs, pens and pencils, buttons, weighing scales, waterproofing clay for his garden, an early lawn mower, and the world's first washer-dryer.

For his scientific work there are notes on buying a new microscope, nurserymen, translation services, illustrators and artists, photographers, printers, publishers, booksellers, Wardian cases, collection cabinets, bellglasses and netting for covering plants, drying paper for preserving plant specimens, insect pins, and water-heating equipment for the hothouse.

|

| Photograph by Darwin's son William of a lawn mower with gardeners Henry Lettington (right) and William Brooks (left) around the time Origin of species was published. |

There are some cryptic and almost undecipherable notes on buying fireworks (for a village display) and having a reliable man from Fenwick the manufacturer come down to prepare them (p. 13). Presumably Darwin didn't know that the manufacturer's son and an employee had been killed in an explosion nine years before. So dangerous was the profession that Fenwick himself and eight others, including his wife, would be killed in another explosion in 1873. Darwin's fireworks display was without casualties and can be dated by a record in his Account Books to July 1852.

Unsurprisingly, there are details of pigeon breeders and horse dealers, but with several names not found elsewhere. Among the list of pigeon breeders on p. 32 is a line about directions squeezed in later. It refers to an area of Battersea Park where there was regular sport shooting of pigeons and other birds. On advertised days gentlemen would meet for prizes, sweepstakes and other forms of betting. A live bird dealer would supply pigeons priced by the dozen. These were released one at a time for each shooter and the best shot would win the bet or prize, very often a silver-plated powder flask. (The electroplating was done by another firm in the Address Book.) Darwin's interactions with pigeon fanciers has long been discussed, but this entry refers to a place where pigeons were actually flown. Darwin's note reads "Roller after 4 oclock" meaning that called Roller pigeons, which have been selected to tumble or roll in flight, would be flown at that time. The birds for sport shooting were supplied by some of the men in Darwin's list, and these tend not to be the experienced breeders he would later cite in his books which is why their names have remained unseen.

|

|

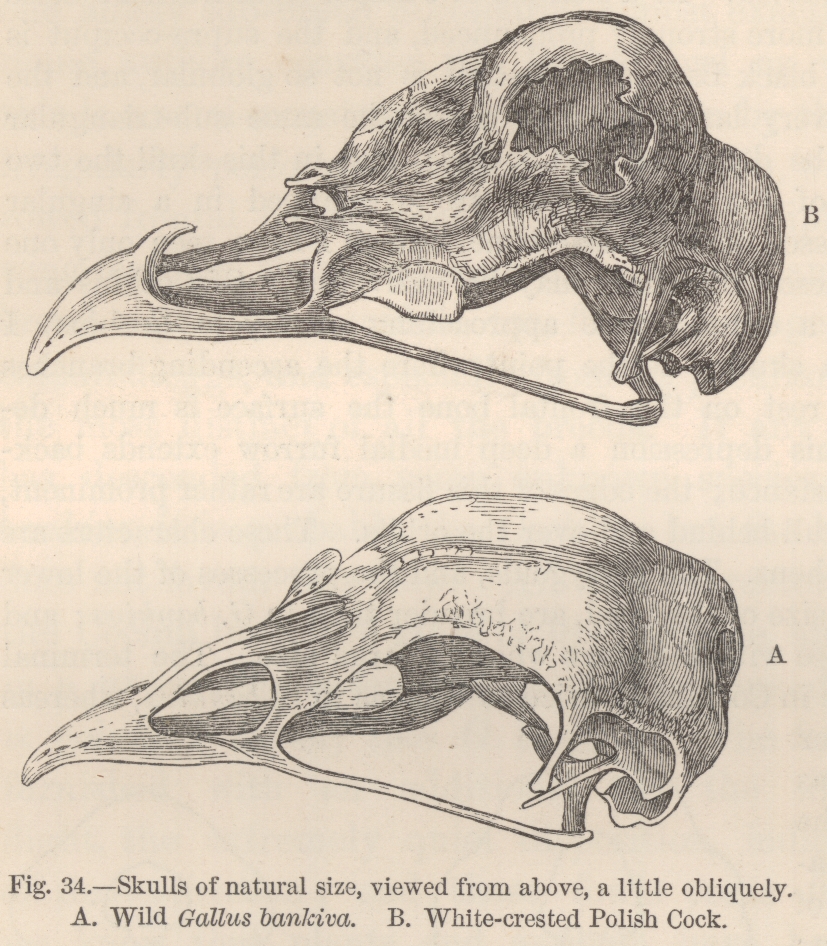

| Comparison of domestic and wild chicken skulls from Variation under Domestication (1868). | The 'Hydro-extractor, or centrifugal drying machine'. Some were steam powered, Darwin noted a smaller hand-powered model. Illustrated Exhibitor (1851) |

This is an overlooked area of social history. These were extremely popular open air events with huge crowds. (There was no pigeon pest problem in Victorian London. This is why 'clay pigeons' for target shooting of this name.) Darwin was not known before to be among them. His visits would probably have been to see specially bred birds such as tumblers flown to study the differences in behaviour that could be modified by selective breeding.

Another obscure pigeon man on Darwin's list was mentioned in Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (14 Jan. 1865), p. 8: "Mr Ovens will exhibit a pen of short-faced pigeons against any one in England, for £10." This is another part of the world of the pigeon fanciers Darwin was infiltrating: pride, competition, and lots of betting.

Darwin devoted almost a hundred pages of his book Variation under domestication to pigeons. "Man" he wrote, "may be said to have been trying an experiment on a gigantic scale; and it is an experiment which nature during the long lapse of time has incessantly tried." 1:3

Darwin learned a great deal from breeders and many other experts for use in his in-progress theory of evolution. According to the 1980s idea that Darwin's theory was a secret (now disproven) surely some of these breeders and other experts would have been very shocked or annoyed that there work had been used to support such a theory. On the contrary, as noted by James Secord in his article 'Darwin and the breeders: a social history' (1982) "there is no evidence that Darwin's sources among the breeders dried up after 1859. Far from feeling betrayed or incensed, the practical men seem to have been more eager than ever to help."

Other details in the Address Book include Darwin's tailors, with a note for his shirts "38 chest". One late entry is for an optician, Dixey & Son, who also provided eye wear to Napoleon, Queen Victoria and later Winston Churchill and is still in business today. Its records were sadly destroyed during the Second World War. The company was unaware, before we contacted them, that Darwin was one of their clients.

|

|

| Dixey & Son. Darwin's previously unknown optician. | Advert for a 'weighing machine' by Poupard. |

Darwin's Health

Darwin's ill health is well known. In the Address Book we find new details and about some of his alternative medical treatments, including his hydropathy or 'water cure'. He recorded a hydropathist named Mr Lovell, a name not found anywhere else in Darwin's writings. Which is just as well as Charles Henry Lovell was charged with manslaughter for killing a patient "by hydropathy"! Although he was acquitted, The London Medical Gazette (12 Feb. 1847) called Lovell a "sham doctor" not in the medical directory.

There is another medical man unknown in the Darwin literature, a surgeon at Down, Edward Ilott. It seems incredible that after thousands of publications on Darwin, and so many on his notorious ill-health, to find so many 'new' names.

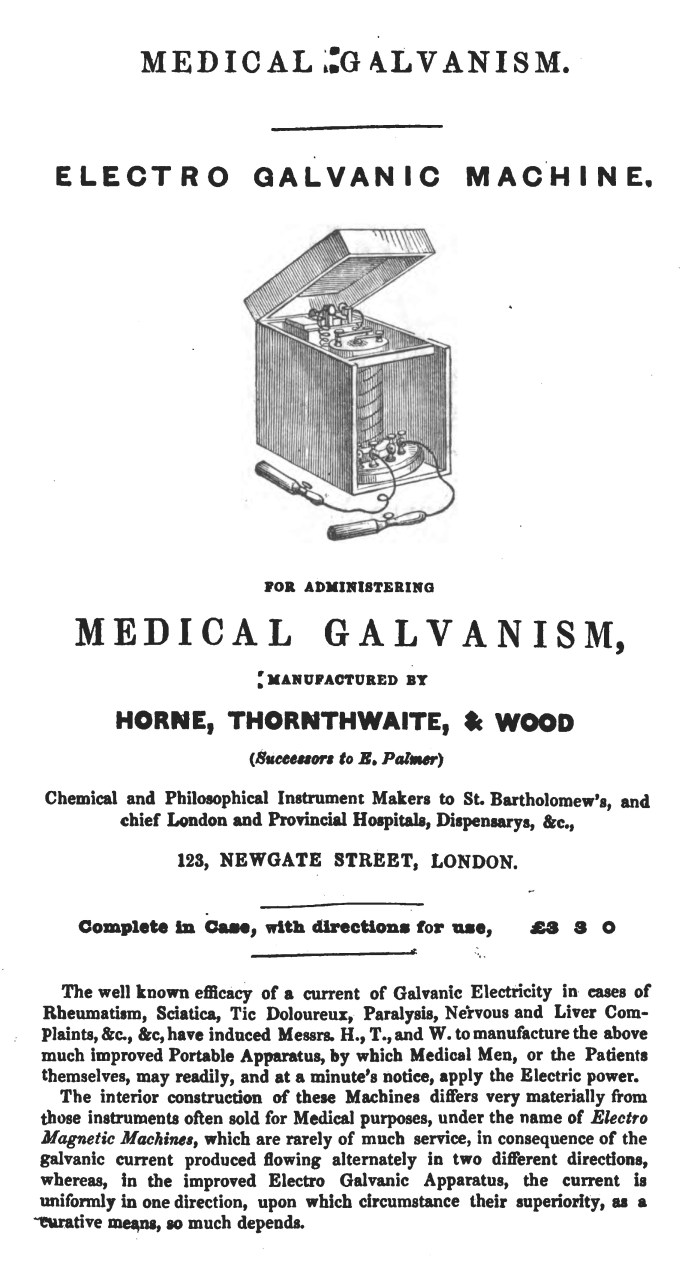

Darwin wrote to his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker in November 1845 "I have been unusually well for a week past, owing, I believe, to what sounds a great piece of quackery, viz twice a day passing a galvanic stream through my insides from a small-plate battery for half an hour." (Correspondence vol. 3.) The editors noted: "The application of a current from a voltaic battery was commonly known as 'galvanisation', and was a popular therapeutic treatment during the first half of the nineteenth century...[Darwin] does not mention galvanic treatment after 1846."

The specific 'Galvanic machine' - with a voltaic battery - that Darwin was referring to in this letter is detailed in the Address Book.

|

|

| 'Galvanic Machine' by Horne & Thornthwaite. Darwin touched his abdomen with the electrodes to treat his stomach complaints. (Flints auctions) | Advert from Thornthwaite, A guide to photography, 1845. See also a photograph and trade card of one at the Science Museum. |

There are so many people in the Address Book for whom no letters with Darwin survive or that we had no idea he had any contact with that to give a list of them would be almost as long as the Address Book itself. To name just a few there is William Robert Wills, the father of Oscar Wilde, Margaret Whelpdale, one of the first female physics lecturers and Octavia Hill, social reformer and founder of the National Trust.

One jumble of words that is particularly difficult to decipher, names an obscure farmer, John Searle in the village of Edenbridge, 18km south of Down. Searle is not known from any other Darwin document. The at first mysterious words scrawled around the address turn out to be the names for three varieties of apple tree. Presumably Darwin acquired sapplings or cuttings from Searle. Only one other Darwin document contains the same three tree varieties - his early 1840s 'Catalogue of Orchard Trees' at Down House. The list is now in a private collection and published in Darwin Online: PC-California

|

|

| A Rogers watercolour box c.1870. (Green & Stone auctions) | A seltzogene advertised by Phillips in 1866. |

One very brief entry is "Rogers Color 133 Bunhill Row". This was Joshua Rogers an art supplier at this address until 1878. Darwin may have purchased any number of products there, such a watercolour box as depicted here.

There is even a note (p. 28) on the word rate of Darwin's long-time copyist from 1856, Ebenezer Norman, a Down schoolmaster who copied many of Darwin's drafts such as the well-known sketch of Darwin's theory of evolution sent to American botanist Asa Gray in 1857. The rough draft of this was later included in the Darwin / Wallace papers read at the Linnean Society in 1858. This prompted the year-long condensation of Darwin's much longer book-in-progress and through a series of now almost lost drafts to create the epoch-making On the Origin of Species published on 24 November 1859.

The Address Book remained in the family after Darwin's death in 1882 along with most of his papers and manuscripts, the vast majority of which have in recent years been gathered together, transcribed and edited for the first time in Darwin Online (the non-correspondence of course).

In 1942 most of Darwin's papers were given to Cambridge University Library. In 1948 the Address Book was thought more appropriate for the public museum at his former home, Down House, as seen in a letter in CUL-DAR156. At one time the Address Book was on display to the public. See The Charles Darwin memorial at Down House (1981), p. 19.

When we picture Darwin writing his famous works, we need to include in that picture the range of objects he kept within reach: pens, ink wells, mechanical pencils, coloured crayons for highlighting, sealing wax, a postal scale, assorted types of writing paper and this humble address book.

John van Wyhe

24 November 2025

Darwin, C. R. & Emma Darwin. [1839-1881]. Address Book. Text & image EH88202575

Acknowledgements

The Address Book is reproduced by permission of William Huxley Darwin and English Heritage (Down House collection). Particular thanks are due to Sabrina Villani of English Heritage for generously helping with access to Darwin's papers at Down House and much other invaluable information and assistance and undertaking to facilitate help from the dedicated group of Down House volunteers.

Thanks also to Chiara Ceci, Edwin Rose, Simon Palmer for information about Dixey & Son, Clive Gravett of the Museum of Gardening for information about Victorian lawn mowers, Lesley Mary Close on button manufacturers, and Antony O'Rourke, head gardener at Down House, for many helpful insights into Darwin's references to gardening supplies and their uses. Moira McManus recognised Darwin's obscure reference to "Atkins" and supplied further information. Jie Ying Ong, Gordon Chancellor, David Clifford, Tony Larkum, Michael Barton, Renos Pittarides and Anke Timmerman kindly offered suggestions on hard-to-decipher passages and other assistance.

RN6