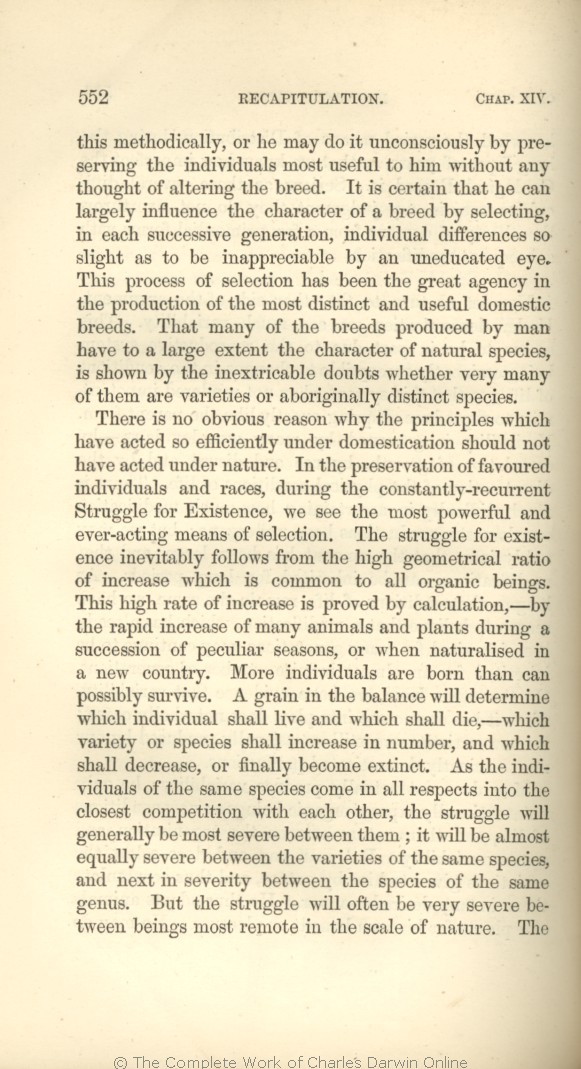

this methodically, or he may do it unconsciously by preserving the individuals most useful

to him | to him 1866 |

| to him at the time, 1859 1860 |

| to him at the time 1861 |

| or pleasing to him 1869 1872 |

| thought 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | intention 1869 1872 |

| ..... 1861 1866 1869 1872 | | quite 1859 1860 |

| by an 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | except 1869 1872 |

| uneducated 1859 1860 1861 1866 |

| by an educated 1869 1872 |

| process 1859 1860 1861 1866 1869 | | unconscious process 1872 |

| production 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | formation 1869 1872 |

| of the 1859 1860 1861 1866 | of the 1869 1872 |

| very 1859 1860 1861 1866 | very 1869 1872 |

| aboriginally 1861 1866 1869 1872 | | aboriginal 1859 1860 |

| distinct species. 1861 1866 1869 1872 | | species. 1859 1860 |

|

|

There is no

obvious | obvious 1859 1860 1861 1866 1869 | obvious 1872 |

| have acted 1859 1860 1861 1866 1872 | | act 1869 |

| preservation 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | survival 1869 1872 |

| the most 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | a 1869 1872 |

| means 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | form 1869 1872 |

| selection. 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | Selection. 1869 1872 |

| calculation,— 1860 1861 1866 1869 1872 | | calculation, 1859 |

| rapid increase of many animals and plants during 1860 1861 1866 1869 1872 |

| effects of 1859 |

| or when naturalised in a new country. 1860 1861 1866 |

| and by the results of naturalisation, as explained in the third chapter. 1859 |

| and when naturalised in a new country. 1869 |

| and when naturalised in new countries. 1872 |

| will 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | may 1869 1872 |

| individual 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | individuals 1869 1872 |

| individuals 1860 1861 1866 1869 1872 | | indi- viduals 1859 |

| But 1859 1860 1861 1866 | | On 1869 1872 |

| struggle 1859 1860 1861 1866 |

| other hand the struggle 1869 1872 |

| very 1859 1860 1861 1866 1869 | very 1872 |

| being 1866 | | beings 1859 1860 1861 1869 1872 |

| most 1859 1860 1861 1866 | most 1869 1872 |

|