'State this with clearness': an introduction to the Santiago Notebook

The Santiago Notebook takes its name from the city of Santiago (Saint James or 'St Jago'), the capital of Chile.1 It is probably the most closely studied of all the surviving Beagle field notebooks. It has been quoted from by many scholars in connection with the famous passage which until recently was believed to confirm that Darwin had thought out his coral reef theory before seeing a coral island, as he claimed in his Autobiography, p. 98. Partly for this reason, the Santiago Notebook has been displayed in recent years in some of the world's great museums.

The earlier theoretical pages of the Santiago Notebook record Darwin's transition from a view of crustal mobility dominated by his observations of elevation of the continental mainland, to a literally more balanced view, in which he came to see the oceans as predominantly areas of subsidence. By the time Darwin had sailed across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and was re-crossing the Atlantic, he was equating elevation with volcanoes and subsidence with coral reefs. These he linked respectively with the Tertiary and Secondary eras of geology of Europe, and was beginning to see how the 'Geology of the whole world will turn out simple' (Red Notebook, p. 72; see Rhodes 1991).

Stoddart 1976 reviewed the background to the scientific theories of coral reef formation prevalent at the time the Beagle's orders were drafted, and, fortunately for Darwin, these theories had been ably summarised for him by Lyell 1832. The development of Darwin's brilliant theory for the origin of coral reefs, starting with the passages written in the Santiago Notebook before the Beagle departed South American shores, has been analysed in some detail by Sulloway 1983. Darwin mentioned his theory in a letter to Caroline Darwin dated 29 April 1836 (Correspondence vol. 1, pp. 494-7 and footnote).

The Santiago Notebook coral passage is analysed in an appendix to the first volume of the Correspondence, and by Herbert 2005, Armstrong 2004 and Herbert 2005, in particular, have also shown how, in December 1835, Darwin, having seen some reefs and from extensive reading, worked up his theory into perhaps the first of the synthetic essays from the voyage to be almost ready for publication. This essay, headed 'Coral islands' and first published by Stoddart 1962 is now available on Darwin Online. The essay is now in DAR41.1-12, DAR41.13-23, and formed the basis for one of Darwin's first scientific papers, Darwin 1837, which in turn developed into his classic book Coral reefs. Stoddart 1976 also reviewed contemporary reactions to Darwin's theory and Rosen 1982 took this further to place the theory in the general context of global tectonics.

Against this background, we can now begin to look in more detail at the Santiago Notebook itself. The notebook is c. 8,400 words long and as such it is the fifth longest notebook, but has the lowest density of diagrams in proportion to text of any of them.

The Santiago Notebook is, as the lone example of Type 6, is physically unlike all the other field notebooks. The manufacturer's label shows that the notebook was made in France. Darwin may have purchased the notebook in St Jago.1 This is suggested by the fact that the Santiago Notebook is a unique type of notebook, and as Darwin had already filled the Valparaiso Notebook by the time he reached St Jago he would have needed another notebook for the rest of his circuit back to Valparaiso.

There is one other feature of the Santiago Notebook which sets it apart physically from the other field notebooks. All of them have a paper label gummed to the cover on which Darwin wrote in ink the names of the places described in the notebook. In the case of the Santiago Notebook there are two labels, one on each side, each bearing the name 'Santiago Book'. Darwin seems to have added identical labels to both sides of notebooks after the voyage. This is the case for the transmutation notebooks but none of the other field notebooks. However the Red Notebook has the same label on both sides. This indicates that Darwin himself 'archived' the Santiago Notebook differently from or at a different time than the other field notebooks. Evidence is presented below to argue that Darwin used the Santiago Notebook not only while in Chile, but in fact for several years after the voyage, by which time he was using his theoretical notebooks.

These differences between the Santiago Notebook and the other Beagle notebooks seem to tally with its unique position in being transitional between a typical field notebook (i.e. one used in the field to record observations on a day to day basis) and one used to record theoretical speculations. The notebook was used in the field in September 1834, pp. 1-67, but this includes a very long retrospective entry for 18 September, written in ink, which is more reflective than usual. There are then about five pages of 'theory' which it is tempting to imagine were prompted by Darwin's inability to get out and about by virtue of his illness during October, although they could have been written any time between September 1834 and February 1835. There is sometimes a subtle shift in Darwin's notebook style when he became more 'theoretical' and this shift can be detected in these pages. Darwin's field notes are always written in the first person (for example, 'I rode to…' or 'we ascended…'), whereas his 'theory' style tends to be in the third person.

The Santiago Notebook was next used in February 1835, pp. 73-87, although true field notes do not begin again until p. 79. This was around the time Darwin also made some notes in the B. Blanca Notebook, pp. 82b-end, and also just after he wrote his short but highly important essay on the extinction of the 'Mastodon' fossil which it is reasonable to guess was written between Chiloé and Valdivia around 7 February. See the introduction to the Port Desire Notebook. It is worth noting that the 'Mastodon' notes record Darwin's first theoretical break with Lyell, on the issue of extinction, and that it was during the following few months that Darwin broke from Lyell more forcefully on the issue of coral reefs. See Herbert 1982.

For the recording of field notes, Darwin then switched from the Santiago to the Galapagos Notebook for a few pages dated mid March but mainly to the St. Fe Notebook for his March-April expedition across the Andes. The view of Barlow 1945, p. 231, that a notebook dedicated to Concepción (late February to early March) is missing, seems unlikely.

Darwin continued, however, to use the Santiago Notebook from March 1835 for more speculative or theoretical notes and the remainder of the notebook, pp. 88-124, plus excised pages, which have not been found, became the precursor of the Red Notebook, as Sulloway 1983 was the first to show. The Red Notebook, which was the first notebook dedicated to theory, was apparently opened in May 1836 and used until it was supplanted in July 1837 by the famous 'theoretical notebooks' in which Darwin developed some of his greatest scientific theories (Barrett et al. 1987).

Previous workers who have studied the Santiago Notebook have concluded that it was the filling of the Santiago Notebook which caused Darwin to open the Red Notebook, or at any rate that the Santiago Notebook was not used after May 1836. We believe that the Santiago Notebook was only partially filled by May 1836 and was in fact used in parallel not only with the Red Notebook. It is even possible that it was used in parrallel with Notebooks A, B and C, and with the St Helena Model Notebook at least until the summer of 1838. We also believe that there may well be other important links between the Santiago Notebook and Darwin's post-voyage researches.

This chronology, if correct, will require some reappraisal of Darwin's scientific activities in the months leading up to his discovery of natural selection (for example, Rudwick 1982; Browne 1995).

St Jago to San Fernando to Valparaiso, September 1834

The Santiago Notebook was the last notebook to have been first used in 1834. We believe it was opened at the beginning of September 1834, rather than mid-August as Sulloway suggested (see footnote 1 in the introduction to the Valparaiso Notebook). The notes record Darwin's setting out southwards from St Jago, where he had spent a very enjoyable week relaxing after his two week northern circuit from Valparaiso, recorded in the Valparaiso Notebook.

Darwin's friend Corfield came up from Valparaiso to meet him in St Jago to 'admire the beauties of nature, in the form of Signoritas'. The two men stayed at an English hotel, and Darwin told FitzRoy that he could be contacted at the Fonda Inglese (letter of 28 August 1834; see Correspondence vol. 1, p. 406).

From St Jago Darwin went more or less south to Rancagua and San Fernando, then down the Rapel valley to Navedad on the coast and from there back up to Valparaiso. The whole August-September expedition itself gave Darwin an excellent geological overview of the outer ranges of the Andes. These he described in South America (mainly pp. 169-175), but he also published several papers dealing with the tectonics of the Chilean coast in which he used information collected on this expedition. The outer ranges are composed primarily of gneiss and granite, as Darwin showed, but today it is understood that they are the result of melting of the edge of the South American continental plate as it overrides the Nazca oceanic plate. Herbert 2005, p. 224, reproduces a small diagram of the coast range from Darwin's geological diary, DAR36.1.438, which gives a sense of how he saw the basic structure of the country.

Darwin became ill after leaving St Jago and by the time he was back in Valparaiso on 27 September he was in no state to travel any further (see introduction to the Port Desire Notebook). He was sufficiently ill to require the attentions of the Beagle's surgeon, Benjamin Bynoe (1804-1865). Darwin attributed his stomach disorder, in a letter to his sister Caroline (see Correspondence vol. 1, p. 410) to drinking chichi, the local Indian aguardiente, but historians including Keynes 2003 generally blame typhoid.3 Darwin drank the chichi at a gold mine around 16 September and seems to have become ill within 24 hours.

While it is obvious that Darwin had a miserable time getting back to Valparaiso in the last week of September, we do not agree with Barlow 1945, p. 228, that his handwriting at this time became any more 'wild and straggling' than usual. Neither do we detect the 'straggling hand of a sick and exhausted man' which Huxley and Kettlewell 1964, p. 40, used as a caption for a photograph of pp. 40-41 from the Santiago Notebook.

The notebook opens on p. 1 with a complex sequence of jottings almost certainly written in St Jago, starting with 'Biscatchas making a noise'. Darwin described the behaviour of this rabbit-like animal (Lagostomus trichodactylus), with great care in his Journal of researches, p. 143.

Several names appear on p. 1: Corfield, unsurprisingly, and Darwin's servant Covington. 'Mariano 7£' is no doubt a fee to Darwin's guide Mariano Gonzales but one can only guess why Darwin gave £12 to a man called Ramirez, perhaps for horses. Alexander Caldcleugh of St Jago (see introduction to the St. Fe Notebook) is mentioned in connection with a book and with the 'geology of Concepcion'. A Mr Conrad seems to have provided some evidence of the elevation of North America, which would have been highly interesting corroboration to Darwin of his emerging views on South America. Conrad's information is referred to in Darwin's 'February 1835' essay on the extinction of his 'Mastodon' (DAR42.97-9), and Conrad later provided Darwin with observations concerning erratic boulders in Alabama (see Journal of researches, p. 614).

John Wickham (1798-1864), First Lieutenant of the Beagle, is mentioned without explanation, although he had taken some charts to St Jago in August (Keynes 2004, p. 161); this is the only time Wickham's name appears in the notebooks. Finally there is Juan Ignacio Molina's name in connection with the behaviour of the Carrancha (a bird of prey, Polyborus brasiliensis; see Birds, pp. 9-12). Darwin's copy of Molina 1794-5 is inscribed 'Valparaiso 1834'.

The field notes proper start on 2 September on p. 2, with Darwin riding to a place northwest of St Jago beyond what is now Padahuel (which Darwin called 'Padaguel' in the notebook and 'Podaguel' in South America, p. 59, 'to see Limestone' . In the published version Darwin described this as a 'calcareous tuff' overlying sandstone with 'water lines' (that is, cross-bedding, caused by current action), all of which he was certain were of marine origin. In South America Darwin wrote that he found a similar rock on the summits of the San Lucía and San Cristóbal hills in St Jago, and mentioned that the barometric height of 2,690ft (c 900m) of San Cristóbal provided by Frederick Andrew Eck indicated dramatic elevation of the coast range. The measurements are to be found on a list in DAR35.1.232 (see Correspondence vol. 1, p. 407). They are dated September 1834 in Darwin's handwriting.

The visit to Padahuel seems to have been a day excursion, and it is unclear what else Darwin did until he left St Jago on 5 September: 'started gloomy day' and 'crossed bridge of Hide' (see introduction to the Valparaiso Notebook). That night they stayed at a 'nice Hacienda' where there were 'Signoritas', which became 'several very pretty Signoritas' with 'charming eyes' in the Beagle diary. In the Beagle diary Darwin recounted how he assured the signoritas that he was 'a sort of Christian', but in the notebook he wrote that they were 'astonished at clergyman marrying' and could not accept that Darwin's God was the same as theirs! Curiously there is more detail about this conversation out of date sequence on p. 18 of the notebook.

On 6 September, p. 4, Darwin continued to Rancagua on an 'interesting ride' across the 'great plain', p. 6, which was incised by rivers flowing rapidly from the Andes. Darwin noted the nest building habits of various birds and seemed to record that some 'talk' while others 'sing'. The habits of the 'Tapaculo and Turco' were eventually described at some length in Journal of researches, p. 329. Darwin also added an aide mémoire to check which names Molina 1794-5 gave to these birds and on the 7th he recorded the behaviour of a 'Goosander….runs quick. Very active in the rapids'. Darwin's note on the nest building of the 'Furnarius' on p. 9 is referred to in Natural selection, p. 504.

Darwin's party turned up the Cachapol [Cachapoal] valley to visit the hot baths at Cauquenes [Termas de Cauquenes]. Since the bridges were taken down every winter Darwin's party had to ride across the torrents and one 'could not tell whether horse moved or not'. Darwin was hugely impressed by the erosive power of the torrents which in summer could move 'fragments as big as cottages', p. 10. Because of heavy rain, the last he was to see for seven and a half months, Darwin stayed at the baths for five days, until 13 September.

In South America, p. 66-67, Darwin stated emphatically his view that the Cachapoal valley was sculpted by the sea and that the 'decided fringe …composed of pebbles', p. 9, marks a 'fossil beach' which was once at sea level. Darwin recalled in South America, p. 67, that to his mind:

This has been one of the most important conclusions to which my observations on the geology of South America have led me; for we thus learn that one of the grandest and most symmetrical mountain-chains in the world, with its several parallel lines, have been together uplifted in mass between 7,000 and 9,000 feet, in the same gradual manner as have the eastern and western coasts within the recent period.

Darwin's recognition of former sea beaches was reinforced by those he studied in 1835 near Coquimbo (see introduction to the Coquimbo Notebook). As is well known, he overstretched this explanation in 1839 by applying it to the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy in Scotland (Darwin 1839), which were soon afterwards shown to be glacial lake beaches, although the methodology he used at Glen Roy was scientifically impeccable (see Rudwick 1974, and Rudwick 2008).

The baths as Darwin found them were just 'miserable huts' and it was 'necessary to bring everything' to sample them, but there was a 'pretty view', p. 8. Today they are regarded as one of the most beautiful hot spring resorts in Chile, with marble baths and a mid-nineteenth century sala de baños and water around 45˚ C. Darwin noted that the springs were hotter in summer 'Some people can enter hottest', and he reported that 'M. Gay' (1800-1873), the 'zealous and able' French geologist (see Journal of researches, p. 323), 'say Muriat of Lime Spring flow through the pebbles cemented by Carb of Lime hence Gas', p. 11. Darwin met Claude Gay in St Jago, where he was Professor of Physics and Chemistry, but his information that the springs were partly hydrochloric acid obviously intrigued Darwin, who was especially keen that Henslow should get his sample of 'water and gaz' analysed (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 401).

On 8 September, Darwin noted that the 'strata may be seen gradually becoming more inclined till they are vertical', p. 14. On p. 15 he drew a sketch map showing Rancagua to the west and a southwest-trending spur of mountains coming off the Andes. The view was 'singular', with 'little wind – blue sky & clear – very few birds excepting an odd note from Tapacola or Turco – wonderful few insects, dryness of soil', p. 17.

On the 9th Darwin took a ride up the valley to a deep ravine where he could see for the first time close up the 'real Cordilleras', p. 19, and scrambled up 'a very lofty mountain' at least 6,000ft (2,000m) high. On p. 25 Darwin jotted 'Pinchero Pass' and in the Beagle diary he explained that it was through this pass that 'the Renegade Spaniard' Pinchero ravaged Chile. Darwin noticed a block of granite 'several hundred feet above bed of river' which he thought was 'placed in present place by former sea', p. 20. In South America, p. 66, recognising that blocks such as this one could not normally be moved by the sea, Darwin suggested as an alternative that they may have been moved by catastrophic floods consequent on the damming of rivers during earthquakes.

Thursday 11 September was a 'Miserable wet day', p. 30. On the 12th 'Have seen but few Condors – yet this morning 20 together soaring above' and a guasso told Darwin that this meant there was a 'Lion' (i.e. puma) guarding its prey. Since there was a bounty on pumas, the condors usually triggered a hunt using dogs. Darwin was impressed to hear that the pumas were as cunning as foxes and could escape 'by artifice of returning close to former track', p. 31. Pumas on this side of the mountains were obviously fiercer than on the east 'killed a woman & child lately & man at Jahuel!!', p. 31.

On p. 32 Darwin noted that the hot springs had stopped in 1822 (when there was a great earthquake) but were gradually returning and getting hotter again, as 'known by feathers coming from a fowl'. Darwin recounted in his Journal of researches, p. 321, how the locals at the baths estimated the temperature of the water by the ease with which they could pluck 'fowls' which had been scalded in the water.

On the 13th they 'At last escaped from our foodless prison – threatening day snow low down' and 'reached the Rio Claro by night', p. 33. The next day they rode on to San Fernando across a plain: 'to give an idea of its extent, the distant Cordillera only showed their snowy part, as over the sea', p. 35. Darwin here made the extraordinary speculation that this is how Tierra del Fuego might 'appear if elevated'. Furthermore he recalled, presumably from Humboldt, that Quito in Ecuador at 3,000m looked like this, so 'elevation decrease to South?', p. 36.

The dates in the notebook now jump to 18 September and the gap is presumably the four days ('during two of which I was unwell', according to the Beagle diary) when Darwin stayed at Mr Nixon's gold mine at 'Yaquil near Rancagua'. As Darwin drank the chichi at a gold mine, this means that became ill about the 16th. It seems, therefore, that the descriptions of the mines in the notebook are retrospective, which tallies with the fact that they are written in ink. Sulloway 1983, p. 373, suggests that Darwin may have used a travelling writing kit to write this section.

The literary style of the ink notes is more discursive than is usual in Darwin's field notebooks, as witnessed by the fact that the whole entry dated 18 September runs to fifteen pages, before pencil is used again on 19 September, p. 53. According to the Beagle diary Darwin 'took leave of Yaquil' on 19 September so it seems almost certain that the ink section dated the 18th represents the first use of the Santiago Notebook as a medium for recording reflections as well as observations.

On the first page dated 18 September Darwin described a 'Lizard with blackish tail basking on stones in sun', p. 37, which is probably Proctotretus tenuis (Reptiles, p. 7). He mentioned fungus on the 'Roble or oak tree' which (on p. 50) reminded him of England (see Armstrong 2004, p. 72, for photographs of this type of fungus). There follow several pages of geology, then on pp. 40-41 Darwin 'Saw the Descabozado & heard certainly of Peterra', two mountains to the south (see photographs of these pages in Huxley and Kettlewell 1964, p. 40). A series of pages follow in which Darwin recorded information about the geology of the Durazas and Cruzero mines which seems likely to be information direct from Nixon.

Proctotretus tenuis collected in Chile. Plate 3 from Reptiles.

On p. 50 Darwin 'Rode up to the Mine' and 'Saw lake of Tagua-tagua' which he noted in the Beagle diary had been described by Gay. Darwin was shocked to see the conditions endured by the miners who had to carry incredible loads up the crudest of ladders, with 'nothing but beans and bread' to eat, all for '6 & 7 dollars a month'. On p. 52 Darwin wrote 'feudal system of men' immediately followed by the word 'slaves'.

Darwin met the German naturalist Renous at Nixon's house, and on p. 52 he recorded what an 'Old Spanish la[w]yer' thought when Renous asked him for his views on Darwin's activities. After long consideration the old man declared 'no man so rich that he sends naturalist for pleasure – there is a "cat shut up here", do you think King of England allows man to explore stones & reptiles'. Renous related how he had been arrested by the superstitious folks in San Fernando for 'having snakes & feeding Caterpillars'!

The ink section ends with Darwin's surprise at the strength of that hybrid beast the mule: 'wonderful so slim an animal', p. 53, and he expanded on this in the Beagle diary with 'One fancies art has here out-mastered Nature'. The change from ink to pencil on pp. 52-53 is very clear in the photograph of these two pages reproduced together with Richard Keynes's transcription by Yudilevich and Le-Fort 1995, p. 26.

Darwin returned to writing in pencil on 19 September on p. 53 as his party began the descent down the Tenderirica [Tinguiririca] Valley. This eventually becomes the Rapel, towards San Antonio and the ocean (there is a small ink sketch of part of the valley on p. 71. No doubt Darwin was feeling rather ill and the 'miserable place where we slept (nothing but beans & milk)' cannot have helped. In the Beagle diary he noted that he was ill from 20 September to the end of October.

They crossed the plains west of Rancagua which Darwin concluded were 'without doubt', from their 'levelness & great size', p. 55, and 'barrancas upon Barrancas', p. 57, episodically upraised sea bed. He noted the 'Bishops Cave' which was a consecrated cavern in which Indian remains had been found. There were 'no trees' and the landscape reminded Darwin of the Pampas, p. 58.

The 21st was 'Rainy day & I very unwell stopped at kind Chilotan schoolmaster'. On the 22nd they 'Rode on to Navidad' which had a front 'very like Valparaiso – but longer', p. 60. The Beagle diary records that they stayed at the house near the sea of 'a rich Haciendero' and that on the 23rd Darwin was 'very unwell' but 'managed to collect many marine remains from beds of the tertiary formation'. These fossils were of great importance, and included plant material and 'Fishes teeth', p. 64. Many of them were figured by Sowerby in South America, in which book Darwin wrote, p. 127, 'though suffering from illness' he collected thirty-one species, all extinct and of genera no longer (i.e. in 1834) found living so far south.

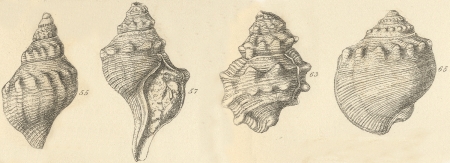

Fossil shells collected by Darwin in Navidad, Chile: Fusus figs. 55, 57, Triton 63; Cassis 65 from plate 4 of South America.

On the 24th and 25th they pushed on to Casa Blanca where they arrived on the 26th. Here Darwin had Covington arrange for a biloche (a kind of wagon; see Young 2007, note 155) to take him back to Corfield's House in the Almendral area of Valparaiso.

After the expedition there are a few pages difficult to date, pp. 68-72, which may represent the beginnings of Darwin's theorising, perhaps the result of being ill and not able to get about observing and collecting. The Zoology notes written at this time show that Darwin was not entirely incapacitated, and he was clearly still intrigued to hear of evidence of sea level change: 'It is said that the sea 70 years ago reached foot of Dr…..house', p. 71. These are the last entries in the Santiago Notebook which probably date from 1834. The notebook was then put aside for the southern summer, while Darwin went south, for the last time as it turned out (see introduction to the Port Desire Notebook), and was not used again until February 1835.

Valdivia, February 1835

Darwin next used the Santiago Notebook as a field notebook on his way back north from Chiloé, around 10 February 1835. This part of the Santiago Notebook covers the time in Valdivia on 20 February when he experienced a massive earthquake, and this may be the reason why a week or so later he started to record his theoretical speculations on crustal instability in the notebook. It has been estimated that the 1835 earthquake was of magnitude 8.5 on the Richter scale, although this is dwarfed by the Chilean earthquake of 1960 which was 9.5. For more information about the earthquake see Keynes 2003, p. 274 and for geological background see the introduction to the St. Fe Notebook, footnote 4.

It seems that Darwin spent the next two to three weeks examining the aftermath of the earthquake and the ensuing tsunamis at Talcahuano (the port of Concepción), but the details of this are not recorded in any extant notebook. Darwin often referred to Valdivia as 'Baldivia' at this time.

Darwin arrived near Valdivia in Chile's Lake District on 8 February, but he seems not to have landed until the 11th. The first entry in the notebook which is certainly from here is in ink and dated the 10th. It records sunset at 6.45pm and sunrise at 5.15am, p. 73). On p. 75 there commences a long list of Andean volcanoes, two of which are noted on p. 76 as having been added to a map 'reduced from one of Dalbe's Republic of Chili surveyed &c &c in 1819'. Page 77 has a piece of tracing paper gummed to it on which is traced a map of the rivers flowing down to a section of the coast about 25km long, with Valdivia at the top.

11 February is recorded on p. 79 'Went in Yawl to Valdivia', whence according to the Beagle diary he went for a ride. Darwin obtained a room from 'obliging Governor' then 'after crossing in a canoe a small river entered forest'. He mentioned the poison made by the Indians and noted the 'Upright Bamboos', p. 80. He recorded the easterly dipping mica slate overlain by clay with quartz pebbles 'as in Chiloe' (discussed in South America, p. 160). On p. 81 Darwin noted the 'Bright red soil' and referred to Febrés's 1765 'Spanish & Chilian & Peruvian' dictionary, which FitzRoy says he found very useful (Narrative 2: 397).

'After travelling some hours through forest (tormented by innumerable flee bites, pigs, dogs, & cats)' the country opened out: 'the curious fact of plains banishing trees', p. 82). Darwin explained in the Beagle diary how the Governor's house was so flea-infested that he actually preferred to sleep in the open. He thought the Llanos 'very pretty' and recorded having 'Heard great guns in the morning' - presumably from one of the coastal forts -, p. 83. On 12 February (his twenty-sixth birthday) Darwin stopped at the Mission of Cudico, where the 'Discontented padres [sic]' was teaching the 'very industrious' Indian children. Darwin expanded greatly on these ethnographic observations in the Beagle diary, where he expressed his opinion that the Padre was wasting his life for want of something more stimulating to do.

There follow some jottings about mines and earthquakes on p. 84; pp. 85-6 are excised. Darwin's activities in the ten days or so up to leaving Valdivia on 22 February are covered in the Beagle diary. On notebook p. 87 Darwin mentions the Padre who was distressed by the extermination of the Indians, then there is a note about a 'Fleet of whalers' and he noted 'There are Whalers cruising for fish' in the Beagle diary for 24 February, which is the date immediately following in the notebook. His experience of the earthquake of 20 February while 'on shore and lying down' is, therefore, not recorded in the notebook but given a memorable account in the Beagle diary.

Other authors, including FitzRoy in his Narrative, also wrote detailed accounts of the earthquake, compiled in the subsequent months. FitzRoy's initial report was 'communicated to the President' of the Geological Society of London (i.e. Lyell) by Captain Beaufort and was read on 18 November, immediately before Professor Sedgwick's reading from Darwin's letters to Henslow (see introduction to Cape de Verds Notebook). FitzRoy's report had been read at Portsmouth a month previously, to the Court Martial 'on Capt. Seymour and his Officers for the loss of His Majesty's Frigate Challenger'.4

The earthquake of 20 February came between 11am and noon (accounts differ regarding the exact time; Darwin refers to this in the Galapagos Notebook, p. 8b and in DAR36.424). It lasted about two minutes with the main shock which destroyed much of Concepción taking just six seconds, and there were several weeks of aftershocks. There were three tsunamis at Talcahuano, each one larger than the last, starting about half an hour after the earthquake. The island of Santa Maria was raised an average of about 3m, but seems to have subsided somewhat later in the year. The fact that the coast appeared to have been raised more than the Cordillera was a bit awkward for Darwin as he had come to expect the Andes to be the central axis of uplift.

Darwin arrived at the island of Mocha [Isla Mocha] on 24 February en route to Concepción, 'having sailed 22d' from Valdivia. This is the last dated entry in the notebook as on the next page, p. 88), in an entry written before reaching Concepción, Darwin embarks on the longest series of theoretical speculations in any of the field notebooks, a series which we believe did not end until the notebook was full several years later (see below).

The Beagle spent a week at Mocha (and returned once, without Darwin, on 27 March). Darwin wrote in South America, p. 124) that he never landed on Mocha but the officers collected some fossils for him. While there the ship felt a strange 'jerk' of the sea which Darwin noted in the Beagle diary snapped an anchor in two and must have been caused by an aftershock. FitzRoy resolved to head north as they were now dangerously short of anchors, and they reached Concepción on the 4 March where Darwin saw the terrible destruction of two weeks previously: 'the most awful yet interesting spectacle I ever beheld' (Beagle diary).

The Beagle sailed for Valparaiso on 7 March, arriving on the 11th. Darwin went to stay at the house of his good friend Corfield. The ship, with new anchors, headed back to Valdivia on the 17th and Darwin did not see her again until she returned on 23 April, by which time he had traversed the Andes, and was ready for another trek, this time northwards to Coquimbo where he experienced another earthquake, on 20 May (see the Coquimbo Notebook).

As a field notebook, the Santiago Notebook was replaced by the St. Fe Notebook on 12 March, but Darwin also made notes dated 14 March of his trip from Valparaiso to St Jago in the Galapagos Notebook. The entry in the Galapagos Notebook on p. 4a is 'Started for St Jago in a Birloches or gig' which appears almost verbatim in the Beagle diary. There are also notes which are obviously of a similar date at the back of the Galapagos Notebook. As recorded in the St. Fe Notebook Darwin made his Andean preparations while staying for a few days in mid March with Caldcleugh in St Jago. He also stayed with him for about four days when he returned to St Jago on 10 April (see introductions to the St. Fe Notebook and the Galapagos Notebook).

The fact that Darwin had at least two field notebooks (i.e. the St. Fe and Galapagos Notebooks) with him on his Andean traverse suggests that he may, for reasons of document security, have preferred to leave the Santiago Notebook on the Beagle around 11 March. If this was the case the pages after about p. 91 were probably not started until 23 April. If, on the other hand, he had had time – perhaps while at sea around the 7th to the 11th of March – to write up all his field notes from the Santiago Notebook, he might have decided to take it with him exclusively for theorizing. This seems unlikely, in view of the relatively short time available, but not impossible. Darwin wrote to Henslow on 18 April 1835 that he had sent 'With the Specimens, there is a bundle of old Papers & Note Books'. (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 444.) These may have included the field notebooks that were no longer used.

The 'theoretical' pages (?April 1835-September 1838?)

Pages 88-124 are completely undated discussion, with references to at least nineteen authors and notes of conversations with at least eight different people. There were in addition ten pages excised from the back of the notebook. Darwin wrote most of the pages, but not all, in ink and, uniquely in the field notebooks, added ink page numbers from p. 90 onwards. Darwin's page numbers are referred to by several scholars, but since we have assigned page numbers to all the pages of the notebook in our transcription we use our numbers, rather than Darwin's.

It is very difficult to present a summary of the subject matter dealt with in the theoretical pages, as a huge range of geological issues is dealt with and they nearly all relate to one another in complex ways. The unifying theme is vertical crustal mobility. Among other topics, they deal with the effects of earthquakes and the sea on the transportal of gravels and erratic boulders, pp. 88-94; this section includes the only diagram in this part of the notebook, showing the effects of elevation on the coast at Chiloé. There is some correspondence between the subjects touched on in these pages and those in the Galapagos Notebook, around p. 32a.

These earlier numbered pages in the Santiago Notebook contain the famous 'coral passage', in which Darwin sketches out the essentials of his coral reef theory, pp. 95-97. They also present Darwin's novel and completely unstudied analysis of the geological history of England in stratigraphical order - that is from older rocks to more recent, pp. 97-104. This was one subject Darwin chose never to tackle in print and his comparative ignorance of English geology was one of the main reasons he was reluctant, in 1837, to become Secretary of the Geological Society of London.

There follows a mixed discussion, partly in pencil and partly in ink, of conglomerates and related sediments, and of the geology of Rio. The conjecture 'I suspect that Granite heated at bottom of ocean', p. 107, is declared 'Very important ' on p. 109. This is reference on a slip of paper in DAR5.B73-B74 which, since it refers to 'p. 18' of 'Santiago note book' must postdate Darwin's numbering of the notebook. There is a subtle shift to even more general theorizing, such as the following which is surely the basis for Darwin's great 1838 paper on crustal mobility (Darwin 1838), p. 108:

Amplify on importance of proving extent & recency of upheavals & manner over whole America. Explaining generally Continental upheaval so important in understanding valleys, diluvial escarpements & successive lines of formations &c showing that they are not mere Local effects, as so many authors suppose.

Some passages belie a highly sophisticated, almost adversarial, approach to the marshalling of evidence according to strict logical principles. Examples include the layering of evidence 'that they have moved…that they have travelled…that this took place…that they thus travelled…', pp. 90-91. Darwin was to apply this technique in print, such as when arguing for the elevation of Patagonia in South America, p. 18. There are other, more conversational, examples in the notebook where Darwin was clearly expressing himself as if trying to persuade his peers, using such phrases as 'we may suppose...' and 'we know that…', p. 104.

Occasionally some contrary evidence seems to be discounted, as on p. 103 'land rose & allowed of numerous corall reef-forming coralls' which is deleted, perhaps because it tends to contradict the linkage of coral growth and subsidence? There is also some rhetoric: ' ؟Do not the successive terraces…', p. 109, 'Is not the presence…', p. 110. Darwin knew when to emphasise a point: 'It must be re re urged…', p. 118, and he did not want to waste his powers of persuasion by bad presentation: 'State this with clearness', p. 109.

Biological topics begin to appear around p. 110 with mention of 'Hydrophobia' (i.e. rabies) and 'If the Pacifick Islds have subsided there ought to be a peculiar vegetation', p. 110. This last conjecture bears comparison with the almost opposite entry in Red Notebook, p. 127, written around March 1837: 'my idea of Vol: islands. elevated. then peculiar plants created' (see Herbert 1980) and to Darwin's first published utterance on species in his 1837 paper on the oceans, also drafted in the spring of 1837:

That some degree of light might thus be thrown on the question, whether certain groups of living beings peculiar to small spots are the remnants of a former large population, or a new one springing into existence (Darwin 1837, p. 554).

There is an increasing number of references to the opinions of other people and a return to the effects of earthquakes, p. 112, and various new topics such as concretions, p. 115, and cleavage. On p. 116 there is another mixture of partly pencil, partly ink jottings on many subjects, some of which were certainly taken up in Darwin's theoretical notebooks (see dating discussion below). The discussions range far and wide and although centred on the Andes include several references to the Falklands and even a reference to the North Pole, p. 118.

The last extant geological entry, p. 124, is in pencil: 'S. America fundamentally & systematically different S. America; shows that the geology of the world cannot be taken from Europe.' This entry, which seems rather obscure, is so similar to one comparing the geology of America with Europe in Red Notebook, p. 18, (see Herbert 1980, p. 36) that we feel justified in suggesting that in the Santiago Notebook entry Darwin must have meant 'Europe' when he wrote either the first or the second 'S. America'.

Finally, there are some 'field' notes on the inside back cover which may date from the Beagle's visit to Mauritius in late April and early May 1836, as Darwin in the note calls it Isle of France as he sometimes did around the time of the visit (see Armstrong 2004 and introductions to the Despoblado and the Sydney Notebooks). The reference to 'Stokes a quire & a half of foolscap' (i.e. 36 sheets) may relate to Darwin's visit with John Lort Stokes to the house of the surveyor general and the purchase of paper on Mauritius (see below in connection with the dating of p. 116). 'I have about 900 pages' is another tantalising clue to dating of these notes, as this is almost exactly the number of pages Darwin had written in his geology diary at that point in the voyage (DAR38).

Sulloway 1983 has discussed the dating of the 'theoretical pages' in the Santiago Notebook in great detail in a pioneering attempt to apply his previously developed (Sulloway 1982) chronology of Darwin's spelling habits during the voyage. Taking all available evidence into consideration, approximate dates can be assigned to some pages:

p. 89: 'ask at Valparaiso and Concepcion', must have been written before 4 March.

pp. 88-91: These pages seem from subject matter (gravels and boulders), literature references (mainly to De La Beche but also to Playfair) and locutions, 'they have travelled on each side from Cordilleras', p. 88, 'they have travelled in opposite directions', p. 90, 'they thus travelled at two very different periods', p. 91, to have been written at the same time, that is before 4 March.

p. 95: Sulloway 1983, note 10 thought, reasonably in our view, that the reference to Caldcleugh having seen a guanaco 'near Cordovean range', p. 95, was a personal communication to Darwin, therefore dating that page to March or April 1835. We cannot, however, suggest any way to decide which of these two is most likely. Sulloway supported this dating with spelling evidence: on the same page Darwin uses 'Pacific', predating his switch to 'Pacifick' in July 1835, and 'corall' predating his switch to 'coral' in February 1836. Sulloway is careful to point out, however, that Darwin used 'Pacific' once later, in October 1835 (DAR37.2:791). The dating of this page and others up to p. 104 is also discussed in the Correspondence vol. 1, pp. 567-571 where it is concluded that the pages predate Darwin's September 1835 sailing to the Galápagos.

p. 105: 'If the circle of change has always gone' is similar to 'if the crust of the world goes on changing in a Circle', written to Henslow on 12 August (Correspondence vol. 1, p. 461). 'Alison's notes' probably refers to the letter from R. E. Alison received by Darwin after 19 July and now in (DAR36.427). See Correspondence vol. 1, pp. 450-3.

p. 110: 'Burchell says' probably dates this page to during or after Darwin's stop in South Africa in June 1836.

p. 111: 'a swelling of the fluid nucleus of the globe, to form the statical equili[brium] destroyed as Sir J. Herschel suggests', as for p. 110, although a related discussion occurs on p. 114 of Notebook A (see Barrett et al. 1987). That page was probably written in August 1838. The page in Santiago may, therefore, have been written around the time of Notebook A or may have inspired the passage of the latter notebook.

p. 113: 'I observed in K: George's Sound' unambiguously postdates the Beagle's visit there of March 1836 (not February as stated by Sulloway; see Armstrong 1985).

p. 116: 'Introduce in cleavage discussion' may refer, as Sulloway and Herbert have suggested, to the 'cleavage paper' (DAR41) Darwin apparently already began. See Herbert 2005 It was written on paper which Sulloway deduced was purchased in Mauritius in the beginning of May 1836. This is not the only possibility, however, as on p. 62 of Notebook A Darwin wrote 'In Cleavage discussion, state …', an entry perhaps dating to early 1838. The 'Mem: to tell Lyell about crocodile in South Sea Island' suggests that Darwin may have already met Lyell, which would date this page to at least late October 1836. It is certainly true that the subject matter here is picked up at several points in the transmutation notebooks, especially Notebook C, in passages dating to the spring and summer of 1838. The page in Santiago may, therefore, have been written around the same time or may have informed the transmutation notebooks.

p. 117: 'N.B. in general discussion introduce diluvium generally submarine' is similar to some entries in R. N. and so seems to have been written very late in or after the voyage.

p. 118: 'Introduce in cleavage paper', as for p. 116.

pp. 118-119: 'In discussion on Porph: Breccia, I should state to gain confidence, that it was sometime before I fully comprehended origin' and 'Introduce into my general discussion the gneiss & Quartz of central Patagonia, on coast' both imply that Darwin was preparing material for publication. While it is true that Darwin began this process as early as 1834 the general tone is also consistent with a post-voyage date.

p. 120: 'coral' in 'The Coral theory' suggests post April 1836.

p. 123: 'Before concluding the Cleavage paper. Consult the VI Vol. of [Humboldt's] Pers[onal] Narra.[tive]'. Again, this seems to link to the paper in DAR41, but it is undated so, as for p. 116, an 1838 date is possible. Herbert 2005, p. 403 note 132 makes clear that that volume of Humboldt was central to the argument of the cleavage paper.

p. 130: 'Wild dog of Australia copulates freely with the tame ones…' is similar to an entry on p. 26 of the St Helena Model Notebook, dated by Chancellor 1990 to August or early September 1838. A similar reference appears on p. 4, which was certainly written no earlier than 1837, of Darwin's Edinburgh Notebook (DAR118; see Barrett et al. 1987, p. 478).

In summary, the theoretical pages of the Santiago Notebook, left undated but paginated by Darwin, can - from context and by comparison with other Darwin manuscripts of more or less known date - can be dated with perhaps decreasing degrees of certainty. The earliest pages were written in March 1835, some eighteen months before the end of the voyage. The later pages, however, were written at various points towards the end of the voyage and began to overlap with entries in Red Notebook, the first notebook dedicated solely to theory.

It seems possible, however, that the Santiago Notebook was still being used after Darwin had replaced R. N. with his Notebook A devoted to geology, and his Notebooks B and C devoted to species. More accurate dating may be possible from chemical analysis of the various inks used in these notebooks. Unfortunately, until the excised pages are found, it is impossible to know exactly when the Santiago Notebook was finally put aside.

The Santiago Notebook is one of the most fascinating and problematic of all Darwin's notebooks and surely the only one in which we can trace in some depth the intellectual development of Charles Darwin, from field observer to published author. The precise dating of the theoretical passages has challenged scholars for decades and seems likely to remain elusive. We believe, however, that the analysis presented here will provide a firm foundation for further use of this remarkable document.

Gordon Chancellor and John van Wyhe

August 2008

'Santiago Book.' (9.1834; 2.1835-9.1838?). Text EH1.18 [English Heritage 88202338]

1 Darwin seems to have been uncertain what to call the Chilean capital, since he used 'St Jago' in his field notes and various Beagle diaries until at least May 1836 (Animal notes, p. 12; see Sulloway 1983, table 2). He mingled 'St Jago' with 'Santiago' in the ink lists of heights and distances in the St. Fe Notebook, pp. 60a-65a, in one case on the same page, p. 63a. These notes seem to have been written in Valparaiso and the question 'Was the great wave which destroyed Concepcion quite sudden' on p. 65a obviously post-dates 20 February 1835. The reminder 'to draw 261:2 at St Jago' narrows this to before he arrived there on 14 March 1835. It is worth noting that on the same page Darwin wrote 'Pencil note Book some in town', supporting our suggestion that he intended to buy a new notebook in St Jago. Curiously he used 'St Jago' on the label of the Valparaiso Notebook, probably indicating that the labelling of notebooks was not all done at the same time. It is unknown when Darwin labelled this as 'Santiago Book.' Even more curiously he used the spelling 'St Iago' in his correspondence during the voyage. He seems to have settled on 'Santiago' by the time he published Journal of researches, but reverted to 'St Jago' in South America.

2 We are aware that Armstrong 1985 dated the first use of the Red Notebook to just after the Beagle quit Australia in March 1836, but we believe that dating is unlikely in view of the evidence for a post-Mauritius first use.

3 There seems to be some confusion about chichi. Parodiz 1981, p. 120, says it is made from corn, whereas Covington (Young 1995, note 151) said it was made from cider.

4 Mention should be made at this point of the wreck of H.M.S. Challenger, which is an important part of the Beagle voyage. While Darwin was trekking from Coquimbo to Copiapó, FitzRoy was engaged in a successful mission to rescue the crew of the Challenger, which had been wrecked on the treacherous Dormido Shoal, near Araucho, c 30km south of Concepción. FitzRoy's account of his daring mission is told in Narrative 2: 428-80 and the whole story is covered by Keynes 2004, chapter 24. So while Darwin was in Copiapó the Beagle was under the command of Lt Wickham who collected Darwin on 5 July and took him to Iquique and Callao, at which latter place FitzRoy rejoined the Beagle on 9 August.

RN7