'Filled with astonishment': an introduction to the St. Fe Notebook

The St. Fe Notebook takes its name from Santa Fé, a town in northeastern Argentina, near the junction of the Paraná and Salado rivers, opposite the city of Paraná. It is one of the most interesting of all the Beagle field notebooks. Indeed, in some ways it can claim to be the most precious of them all, as it spans what was perhaps Darwin's geologically most prolific period of the voyage, and the one during which he committed to a Lyellian, or gradualistic, view of the geological history of South America. By the time he had crossed the Andes he had seen proof of their complex vertical oscillations, to be measured in thousands of metres over vast periods of time.

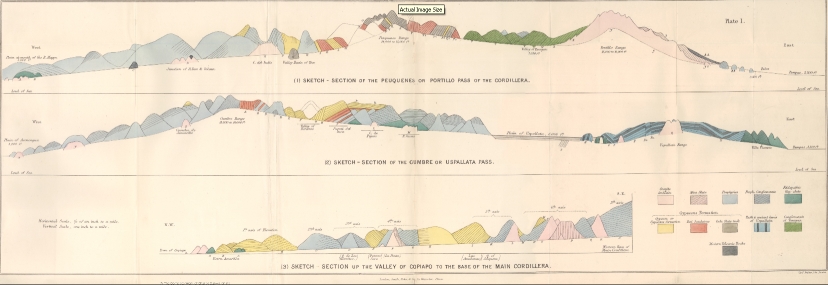

After the voyage Darwin was recognized as an authority on the geology of the Andes and he was confident in 1846, South America p. 248, in asking rhetorically 'how opposed is this complicated history of changes slowly effected, to the views of those geologists who believe that this great mountain-chain was formed in late times by a single blow'. Introducing his account, Darwin wrote with characteristic modesty: "Considering how little is known of the structure of this gigantic range, to which I particularly attended, most travellers having collected only specimens of the rocks, I think my sketch-sections, though necessarily imperfect, possess some interest." (South America, p. 176.)

Plate 1 from South America showing geological sections through the Andes. The first two show Darwin's southern and northern traverses between Santiago on the left and Mendoza on the right (c. 200km, 120 miles), the third showing the Copiapò [Copiapó] valley in northern Chile (c. 100km, 60 miles).

Thus Darwin, with characteristic modesty, justified publication of his classic geological sections through the Andes in South America, which have been shown by subsequent research to be remarkably trustworthy. See Morton 1995. The original field sketches, drawn on the spot, are in the St. Fe Notebook. The sections only needed to be 'stitched' end to end with minor adjustment to form the published sections.

Two of the most important field sketches, from the St. Fe Notebook, pp. 125a and 146a, were reproduced in Barlow 1945, plate 11. These two are instantly recognisable as the left and right halves of Darwin's published section no. 1. The published sections are coloured. Several pages of the St. Fe Notebook Notebook, around p. 195a, are smeared with paint of exactly the colours which appear in the published sections. So around 1845, when Darwin was preparing his fair copy sections (such as the one in DAR44.33 reproduced in Herbert 2005, pl. 7) he apparently tested the watercolours by dabbing his brush on the St. Fe Notebook.

The first part of the St. Fe Notebook covers what Barlow 1933 called 'expedition 3', Darwin's 1833 trek from Buenos Ayres to Santa Fé and Paraná and his return by boat. The second part of the St. Fe Notebook covers what Barlow called 'expedition 7', Darwin's great 1835 circuit across the Portillo and Uspallata Passes of the Andes, which he labelled prosaically 'Cordillera of Chile'. In fact most of the highest mountains are in Argentina.

The St. Fe Notebook presents the most dramatic contrasts between the many aspects of geology and natural history which Darwin encountered on both the Atlantic and Pacific margins of South America. It is significant also as a record of his health, as it covers the episode, from 2 October 1833, when he had an illness sufficiently protracted to force him to alter his travel plans. His plan had been to ride from Santa Fé to Monte Video across Entre Rios and Banda Oriental, but by 10 October he abandoned this idea in favour of taking a balandra (a type of barge) down the Río Paraná back to Buenos Ayres. The St. Fe Notebook also records how on 26 March 1835, when in the high Andes, he was bitten by the Benchuca [Vinchuca] bug from which it was first suggested by Adler 1959 he may have contracted Chagas's disease, although Keynes 2003, p. 284, cites good reasons for doubting this. Paradoxically, to judge from Darwin's exertions in the Andes, at the moment he was bitten he was perhaps fitter than at any other time in his life.

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of the St. Fe Notebook is the break of about 16 months between the first period of use, around 21 September to 13 November 1833, and the second, 12 March to 20 April 1835. This is by far the longest break in use of any of the notebooks, and means that in terms of content the St. Fe Notebook may almost be thought of as two separate notebooks. During the 'break' in use there is a complex sequence of use of six other notebooks and some loose notes.1

The St. Fe Notebook is physically different from all the other notebooks except the Banda Oriental Notebook. At c. 22,000 words, the St. Fe Notebook is by far the longest of the notebooks. It is twice as long as the next longest notebook (Coquimbo) and seven times longer than the shortest notebook (Sydney). Not only does it have many more pages than the other notebooks – but the number of words per page is also much higher than the others. Furthermore, there are far more diagrams in the St. Fe Notebook than in any other notebook except perhaps the Port Desire Notebook. All the diagrams in the St. Fe Notebook are in the 1835 part. The St. Fe and Banda Oriental Notebooks differ from the other notebooks in that they are the only two with W. BROOKMAN 1828 watermarks. We therefore class these two notebooks together, as Type 3 (see the general introduction). Like the Santiago Notebook they have the hinge on the long side, unlike the other notebooks, which all have their hinge on the short side. For this reason, perhaps Darwin found the St. Fe, Banda Oriental and the Santiago Notebook less easy to hold while writing than the other field notebooks. Another physical peculiarity of the St. Fe Notebook is that there is a piece of string attached to the clasp. One can only guess at the function of the string; perhaps it was once tied to the pencil as the St. Fe and Banda Oriental Notebooks have no integral pencil holder. Taylor (forthcoming 2009) provides a photograph of pp. 91a-92a which gives an excellent idea of the notebook's appearance.

Buenos Ayres to St Fe and Parana and return, September-November 1833

The earliest dated note in the St. Fe Notebook was made in Buenos Ayres on 27 September 1833, p. 9a, and follows on directly from where the B. Blanca Notebook left off. This note, which marks the start of expedition 3, is preceded in the front sequence by six pages of names, addresses, memoranda, shopping lists and sundry bits and pieces of information, and there are more such notes which seem to date from the same period in the brief back sequence, pp. 1b-5b. It is clear from his Beagle diary that at this time Darwin was staying with Mr Lumb at Calle de la Paz. See Winslow 1975.

There are references in these early pages to numerous contacts, such as the bookseller Steadman on p. 5a. There is a reference to Darwin's assistant Syms Covington (1816?-1861) on p. 4a. See Young 1995. Covington's assistance to Darwin may date back at least to September 1832 but was only officially recognized in June 1833. There are reminders to pay various people for various things, e.g. 'Tailors bill', p. 4a, and to buy items that would be needed on the planned expedition into the interior, e.g. 'Mice and rat traps', p. 5a. Darwin also intended perhaps to revisit the fossil collections in the Buenos Ayres Museum which was then as now one of the finest in South America. See Parodiz 1981.3 Darwin noted a 'Megatherium found at R del Animal', p. 7a and on p. 8a there is the first known mention of the Galápagos by Darwin.

As soon as Darwin got under way on his 500km trek to St Fé, '3 leagues [i.e. about 18 km] from Luxan [Lujan]' he met a gaucho who had travelled with Captain Francis Head (1793-1875). Head was a colonial governor who travelled in South America as manager of the Rio Plata Mining Association in the mid 1820s and Darwin referred to Head's description of Mendoza when he got there in 1835. See Head 1826.

Immediately Darwin started to note anything of interest, such as 'Biscatchas run badly', p. 9a. Very soon he was 'rather unwell', p. 10a and commenting on the vast numbers of horse and ox bones lying around. By p. 13a he was at Rozario [Rosario], future birthplace of the mid-twentieth century revolutionary Ché Guevara (1928-1967). The turbulent political history of the then emerging post-colonial states of South America visited by Darwin is described in the excellent but somewhat neglected Hopkins 1969.

There is a strange story to be told about the entry on p. 12a: 'horizontal variations in colour & hardness & some Tosca rock'. In South America, p. 87, Darwin described the geology of the banks of the Rio Paraná at San Nicolas de los Arroyos: 'when on the river I could clearly distinguish in this fine line of cliffs, 'horizontal lines of variation both in tint and compactness' and in a footnote to that page he added:

I quote these words from my note-book, as written down on the spot, on account of the general absence of stratification in the Pampean formation having been insisted upon by M. d'Orbigny as a proof of the diluvial origin of this great deposit.

It seems likely that by substituting the more poetic words 'tint and compactness' for his field words 'colour and hardness' Darwin was, perhaps subconsciously, creating a more striking description of the layering of the sediment, thus bolstering his view of gradual deposition against d'Orbigny's catastrophic interpretation. As discussed in the introduction to the Buenos Ayres Notebook, this is not the only mis-quotation by Darwin of his field notes.

It is as well to bear in mind that, quite apart from natural hazards, Darwin was at considerable risk on this expedition from 'very bad people', p. 16a. It was no joke when he 'found pistol stolen' at Rozario, p. 13a.

On 1 October at the 'Aroyo Saladillo', p. 15a on the Rio Tercero [Carcarána] he discovered in a soft sandstone 'a large rotten tooth & in the layer large cutting tooth', p. 16a. Owen, in Fossil Mammalia, pp. 17-18, identified one of these as from a Toxodon.2 It fitted precisely into the appropriate socket of an almost perfect skull Darwin purchased about six weeks later 300km away in Uruguay. Soon Darwin encountered 'immense bones of Mastodon', indicating the vast numbers of fossils which must exist by the Rio Paraná.

By p. 19a on 2 October Darwin noted that he was 'Unwell in the night, to day feverish, & very weak from great heat'. He was also in the midst of the Indian eradication programme: there was a 'dead one', p. 20a and 'Lopez other day killed 48', p. 21a.

Darwin eventually arrived exhausted at Santa Fé, p. 22a, and was obviously quite sick, though 'much better' by 6 October, p. 25a, having crossed the Paraná to Santa Fé Bajada [Paraná]. He found a limestone packed with fossil molluscs, brachiopods, fish bones and so on. On 7 October he carefully recorded, p. 29a, the behaviour of some spiders, one of which provided the following balletic spectacle when he saw it

Shoot several times very long lines from tail, these by slight air not perceptible & rising current were carried up-wards & outwards (glittering in the sun) till at last spider loosed its hold, sailed out of sight the long lines curling in the air.

By now Darwin had decided to sail back down to Buenos Ayres but was delayed by contrary winds and 'very timorous navigatons', p. 32a. On 9 October the temperature was 79º Fahrenheit (26º Celcius) at 8pm. Darwin was struggling to keep up with all the fossil mammals he kept finding: 'clearly two sorts of Megatherium…cotemporaneous with Mastodon: case of latter two or three inches thick', p. 30a. Obviously the 'case', i.e. carapace was from an armoured edentate, such as Hoplophorus and certainly not a Mastodon, and it is interesting that by p. 32a Darwin was going to see a very large 'Paludas [armadillo] case'.

He could not excavate the case from the bed which was 'unquestionably…above the limestone' but in compensation he 'found tooth of horse', p. 34a. This was a puzzling find. It was believed at the time that there had been no horses in the Americas before Europeans brought them over in the sixteenth century. Darwin wondered if the tooth had been 'washed down'? Sadly 'the Barranca being inclined precluded the final certainty of the question'. This little tooth had great significance for Darwin.

In Journal of researches, p. 149, Darwin was at pains to show that the taphonomic evidence – the state of preservation – 'compelled' him to believe that the horse was contemporaneous with the extinct Mastodon. Owen, in Fossil mammalia, was able not only to confirm that Darwin had indeed found remains of Mastodon, but also that the horse tooth, and one he found in Darwin's collection from Punta Alta, was a Precolumbian Equus curvidens, proving that horses had existed but gone extinct in the Americas before re-introduction from the Old World. This discovery, Owen wrote in Fossil mammalia, p. 109, was 'not one of the least interesting fruits of Mr. Darwin's palaeontological discoveries'.

But why had horses disappeared from a continent which, to judge from the way they had prospered in the short time since re-introduction, was an ideal environment for them? Had horses and all the other mammals been wiped out by some catastrophe? Or maybe 'species senescence' was the answer: 'as with the individual, so with the species, the hour of life has run its course, and is spent'. (Journal of researches, p. 212).

Darwin later used the tooth as the centrepiece for his mature discussion of extinction in Origin, p. 318:

No one I think can have marvelled more at the extinction of species, than I have done. When I found in La Plata the tooth of a horse embedded with the remains of Mastodon, Megatherium, Toxodon, and other extinct monsters, which all co-existed with still living shells at a very late geological period, I was filled with astonishment; for seeing that the horse, since its introduction by the Spaniards into South America, has run wild over the whole country and has increased in numbers at an unparalleled rate, I asked myself what could so recently have exterminated the former horse under conditions of life apparently so favourable. But how utterly groundless was my astonishment!

Origin, p. 319, explained that according to his evolutionary theory extinction is exactly what would be predicted. It did not, as 'some authors' supposed - one assumes Darwin here had the Italian palaeontologist Giovanni Battista Brocchi (1772-1826) in mind - require species to have internally limited longevities in the way that individual organisms obviously do. This did not mean that Darwin denied that different groups of organisms (e.g. molluscs and mammals) endured for different lengths of time, as it was common knowledge that species in some groups on average came and went more rapidly than in others. In fact it was the fossil groups, such as ammonites, with the shortest species longevities, which were most useful for dating rocks. Neither, in Darwin's view, did one have to postulate some catastrophe as the only explanation for extinction, even when it appeared to happen to large numbers of species simultaneously.

Thus extinction for Darwin in Origin was merely what happens when the number of organisms in a species dwindles to an unsustainable level due to unfavourable in conditions of life (he did not complicate the discussion by mentioning 'pseudo-extinction', when one species has evolved into another species and therefore ceases to exist). Furthermore, Darwin argued, it is usually impossible to be sure exactly what the unfavourable conditions were, and this argument must apply in the case of the horse in Precolumbian America. In other words, Darwin had come to accept Lyell's gradualistic view of extinction, in which the case of the horse in America was not unexpected. By 1859 where Darwin differed from Lyell was in his view of how new species originated in the first place.

In the second edition of Journal of researches (1845), p. 176, Darwin had already extended his discussion of extinction from the one he gave in the first edition but dropped any mention of species having fixed life spans. He concluded one of the most obviously evolutionary sections of his book, which included the enigma of the extinction of the Precolumbian horse, with a remarkable analogy:

To admit that species generally become rare before they become extinct – to feel no surprise at the comparative rarity of one species with another, and yet to call in some extraordinary agent and to marvel greatly when a species ceases to exist, appears to me much the same as to admit that sickness in the individual is the prelude to death – to feel no surprise at sickness – but when the sick man dies, to wonder, and to believe that he died through violence.

Ironically, perhaps, palaeontologists today believe that the more or less simultaneous extinction of about 80% of the larger South American mammals some 11,000 years ago was due to some extraordinary event, and was not just a series of co-incidental individual extinctions. See Benton 1990.

Darwin's understanding of extinction is further discussed in the introduction to the Port Desire Notebook, where one of the most intensively studied documents of the voyage is analysed. See for example Hodge 1985. This short essay, dated February 1835, in a file labelled 'scraps to end of Pampas chapter' in DAR42.97-99, in which for the first time Darwin referred to 'the gradual birth and death of species'.

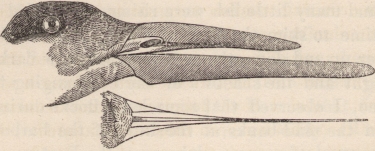

The St. Fe Notebook continues with many pages of observations, such as 'fresh & indupitable sigh [sic] of tigre' (i.e. the jaguar, Panthera onca) on p. 38a. Curiously Darwin spent 13 October 'in bed because cannot sit up'. Fear of tigers it seemed destroyed 'all pleasure in wandering about', p. 39a and tigers had replaced Indians as the main topic of conversation with his fellow passengers. At one point he took a boat and rowed it himself. This might mean that he did not even have his servant, or 'peon', with him, p. 41a; he watched the scissor bill bird Rhynchops nigra catching fish. Darwin's description of the bird's 'wild rapid' flight sharply observed but is not as beautiful as the published account:

Being at anchor in a small vessel, in one of the deep creeks between the islands in the Parana, as the evening drew to a close, one of these scissor-beaks suddenly appeared. The water was quite still, and many little fish were rising. The bird continued for a long time to skim the surface; flying in its wild and irregular manner up and down the little canal, now dark with the growing night and the shadows of the overhanging trees (Birds, p. 144).

The scissor-bill bird as depicted in Journal of researches, 2d ed, p. 137.

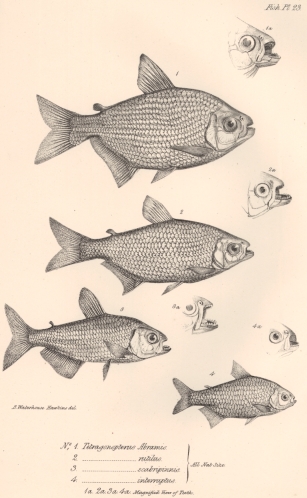

On pp. 43a-45a Darwin described various fish which can be recognised as the new species of Tetragonopterus described by Leonard Jenyns (1800-1893) and exquisitely drawn by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1889) in Fish, pl. 23.

On pp. 45a-46a Darwin recorded what he was told concerning the terrible drought, or 'gran Seco' of 1827-1830, when it became difficult to use the river because of the stench: 'hundred of thousands carcases dead on banks (fall down barrancas) float in water: could not pass many of the streams for smell – it would be said some great flood had killed all, especially as after it all rivers were very much flooded corresponding deposit'. In Journal of researches he made the point that this drought, followed by floods, had within a year washed down and buried thousands of skeletons:

What would be the opinion of a geologist, viewing such an enormous collection of bones, of all kinds of animals and of all ages, thus embedded in one thick earthy mass? Would he not attribute it to a flood having swept over the surface of the land, rather than to the common order of things? (Journal of researches, p. 157.)

By p. 47a he seemed to have heard of the uprising by Rosas's supporters against the Governor of Buenos Ayres, General Juan Balcarce (1773-1836), and when he got to the outskirts of the City on 20 October he had great difficulty in entering (see Parodiz 1981). He had to get ashore at Rio Las Conchas [Reconquista] and make a detour to Quilmas. 'I am in bad predicament', p. 52a, as even though Rosas's passport would eventually get him back into the City as if by magic, this might not have worked for his collections which were on the boat and might have been lost.

After a great deal of inconvenience, however, Darwin took the packet boat to Monte Video with 'many passengers women & children all sick' on p. 55a. Finally on 4 November, p. 55a, he got back to the Beagle but because she was not sailing for another month he took up residence on shore. By good fortune, Darwin's collections and other belongings somehow found their way to him in Monte Video.

On 6 November Darwin went on a short excursion, crossing the Rio St Lucia on horseback, to geologize, but he did not find any bones. By the following day he was back, and he then switched to using the Banda Oriental Notebook, not using the St. Fe Notebook again for almost a year and a half.

Valparaiso to Mendoza, March 1835

The bulk of the St. Fe Notebook, amounting to more than 180 pages, dates from about 12 March to 20 April 1835. These pages record geological observations and occasional notes on natural history and ethnography, of Darwin's great traverse of the Andean Cordillera from Santiago (which Darwin generally called St Jago; see footnote 1 to the Santiago Notebook introduction) to Mendoza via the 'Peuquenes or Portillo Pass', and the return via the more northerly 'Cumbre or Uspallata Pass'. These traverses are described in South America, pp. 187-207 and 175-187 respectively. For a summary of the geology and an excellent general account of the expedition see Keynes 2003. For a more detailed modern geological account of some of Darwin's localities see Morton 1995, and for a summary of the geology of the Andes see footnote 3 below.

The first dated page from 1835 is actually to be found on one of the pages which span the transition from the first sequence and the second sequence. Inevitably, since there are no blank pages, such a distinction in a notebook in which the pages were never numbered by Darwin, is somewhat arbitrary. The page is dated 12 March, was written in ink in Valparaiso, and among several other interesting notes seems to record Darwin's first interest in tropical corals: 'Corall in sea', p. 233a. Sulloway 1983 has discussed this issue in detail in connection with the 'coral passage' in the Santiago Notebook (see introduction to that notebook). Presumably the Sulloway 1983, p. 376 note 17, date of May 1835 for 'Corall' on this page should be March as no other evidence has been found for a May date for this page.

The first of the front pages from p. 60a are written in ink and appear to be notes in preparation for the trip to Mendoza. There are lists of places with what seem to be their heights in feet and distances in leagues. It is clear from the Beagle diary that by 14 March Darwin had come from Valparaiso to St Jago by coach, and was staying with Alexander Caldcleugh (d. 1858), who was probably the source of much of the information (see, for example, p. 64a). Darwin was already familiar with St Jago, having spent a week there in August-September 1834 (see introduction to the Valparaiso Notebook). Caldcleugh was a Fellow of the Royal Society and was a private secretary to the British minister at Rio de Janeiro, as well as a promoter of the Anglo-Chilean Mining Company. He was the author of what Darwin told his sister Susan were 'some bad travels in South America' (Caldcleugh 1825; see Correspondence vol. 1, p. 446) and Sulloway 1983, note 10, which contained a beautiful but very basic map of the geology across the precise part of South America covered by the St. Fe Notebook. Caldcleugh was obviously a great help to Darwin (see Herbert 1995).

In these early pages we see references to places on the Pacific coast such as Coquimbo and Concepcion, where the earthquake of just a few weeks previously on 20 February, which almost certainly had its epicentre under the ocean, had been felt severely (see the introduction to the Santiago Notebook). Pencil came back into use on p. 65a and Darwin asked about the tsunami: 'was the great wave which destroyed Concepcion quite sudden?'. It should be noted that Darwin also made some notes at this time in the Galapagos Notebook, including observations from his trip to St Jago from Valparaiso (see introduction to the Santiago Notebook).

The expedition seems to have begun by p. 66a which is dated 18 March. Here begins possibly the longest and most detailed geological note-taking sequence of the entire Beagle voyage. Barlow 1945, pp. 232-3, said she could 'give no impression of the pages of geological argument'. She did, however, make a brave stab at summarising the geology, and created a vivid picture of Darwin in the Andes: 'clambering over the rocks hammer in hand and with shortening breath from the great altitudes, riding in the icy winds and sleeping on the bare earth'. In fact Darwin wrote to his sister Susan on 23 April that he had carried a bed with him. (Correspondence , vol. 1, p. 445)

The first of many small diagrams is on p. 71a but the more serious section diagrams start on pp. 75a-78a and date to 20 March. The characteristic alphabetical listing of specimens begins to appear, as for example on p. 79a, with specimens J, G and H. Later in the notebook these become extensive lists which we have compared with the four specimen notebooks at the Sedgwick Museum, where Darwin's rock samples are kept. Very often it is easy to translate the alphabetical lists into the numbered lists in the Museum, which were obviously compiled when Darwin had leisure after his expeditions, and it is a great privilege now to be able to go from these lists directly to the actual specimens Darwin was collecting and recording in the St. Fe Notebook (see Herbert 2005). It is also a straightforward matter to compare some of the notebook lists to those published in South America, as for example the list in the notebook on pp. 196a-197a with South America, pp. 190-2.

There is a fascinating entry written on 20 March which begins on p. 83a 'Valley very curious higher up'. This is followed by a diagram and a description of a huge mass of 'Alluvium enormous angular fragments' separating two valleys on the approach to the Valle del Yeso. Darwin was 'greatly perplexed' by this mass which he could not believe had been laid down by river action: 'I hardly dare affirm these hills are alluvium', p. 84a. He described this 250m (800 ft) thick mass in his geological diary, but it was not until after the voyage that he realised that it was a glacial moraine (in Journal of researches, p. 389, he said it had dammed a lake but did not call it a moraine). In the surviving part of his chapter on geographical distribution in his 'big species book', Natural Selection, p. 545, Darwin referred to this moraine which was 'thousands of feet below the line where a glacier could now descend'. He quoted from his geological diary (DAR36.460) in a footnote, and cited the moraine as an illustration of the global Ice Age which by the 1850s was an accepted fact and must have had a dramatic affect on biogeography in geologically recent times. Darwin made a rare direct reference to his Beagle geology field work in a very clear short description of the moraine in Origin, p. 373.

Zoological notes occur from time to time in the notebook, such as what Darwin had been told about condors, but high in the mountains there was 'very little vegetation, no birds and insects', p. 88a. He noted the 'red snow' which showed up in the mules' hoof prints and was relieved to be told that as the winter was beginning to set in unless one heard thunder there was unlikely to be snow, p. 94a. The 'red snow' was described in more detail on p. 126a and in Zoology notes Darwin records that he placed some of the spores 'between the leaves of my Note-Book'. Keynes states that the 'spores' are the alga Chlamydomonas (Zoology notes, p. 286). In Journal of researches, p. 395, Darwin changed the phrase to 'pocket-book'.

Darwin was amused when told by the peons that the reason why his breakfast potatoes were rock hard after a night's boiling was not due to the thin air but to the cooking pot's choosing not to co-operate, p. 95a!

On pp. 103a-104a Darwin made the momentous discovery in some black calcareous shales at Peuquenes of fossil Gryphaea oysters, a univalve (snail), Terebratula brachiopods and 'a piece of an ammonite as thick as my arm'. These were later dated by Alcide d'Orbigny as of Neocomian (early Cretaceous) age, now dated to about 120 million years old. Around p. 115a Darwin started to use numbers to label his specimens.

The peons' 'strange ideas' about 'puna', or the affects of altitude, are noted on p. 129a. Darwin compared the 'tightness of head & chest' to 'running on frosty morning after warm – room'. 'Fossil shells forget' is explained in the Beagle diary as the way the excitement of finding the fossils completely overrode his awareness of difficult breathing. He noted the 'magnificent wild forms' and the 'resplendently clear' air. He said the view from the '1st ridge' was 'something inexpressibly grand', and on p. 131a, in one of the most moving lines in all the notebooks, Darwin thought he 'never shall forget the grandeur of the view from first pass'. The view may be the one he drew on p. 128a. Alexander von Humboldt, in a letter to Darwin dated 18 September 1839, singled out the passage in Journal of reaserches, p. 394, derived from these notes, as one of several 'belles pages' (Correspondence , vol. 2, p. 219).

By 22 March on p. 131a Darwin began the ascent of the eastern (Portillo) range, where, at an altitude of about 4,000m, he had a 'fine view of crater of Tupungata'. He was prevented by a snowstorm from collecting some of the rocks. (South America, p. 183) Within a few pages he is back down among 'flowers like Patagonia' and birds and 'very many mice', p. 133a. On 24 March he killed with his hammer a viviparous lizard with babies which 'soon died', and on p. 136a he caught a young snake. The lizard was mentioned by Darwin in his letter to Henslow of 18 April 1835 (see Correspondence , vol. 1, p. 445 note 7).

By p. 144a Darwin had a 'view of Pampas' from the west. Perhaps the 'line of glittering water lost in immense distance' was the Rio Plata, some 1000km away. On p. 145a there seems to be a reference to Indians being used as trackers, and Darwin noted his bivouac for the night of the 24th, after passing the only Estancia in the area.

There were some animals: 'Tufted Partridge ostrich Biscatcha Peechey', p. 149a. Darwin later realised that the differences between the zoology on the opposite sides of the Cordillera were highly significant. In the second edition of his Journal he wrote of the animals on the east side 'we here have the agouti, bizcacha, three species of armadillo, the ostrich, certain kinds of partridges and other birds, none of which are ever seen in Chile….'. In a footnote to this, which strikes us today as blatantly suggestive of his evolutionary perspective, Darwin referred to Lyell's interest in this link between geology and the distribution of species. (Journal of researches, 2d ed., p. 327.)

Darwin now turned north towards Mendoza and a vast cloud of locusts flying in the same direction near Luxan [Lujan] is described on p. 150-2a. That night he had the 'horribly disgusting' experience of being bitten by the 'Chinches' (Benchuca). On p. 153a there are descriptions of the 'sad drunken raggermuffins' of Luxan and the next day Darwin was in Mendoza which was not worth describing because 'nothing can be added to [Francis] Heads description'. This is a reference to Head 1826 (see also above). On 29 March Darwin mentioned the 'very fine grapes' which are today the basis of Argentina's wine industry. On p. 156a he slept at Villa Vicencio and on the next page started to record the geological section there.

Mendoza to Valparaiso, April 1835

On p. 163a Darwin was unimpressed by the 'very tame' scenery at Villa Vicencio which 'Mr Miers' had made notorious. John Miers (1789-1879) was a mining engineer who, like Caldcleugh, was scientifically minded. He was interested in botany and travelled in South America in the 1820s and 1830s. He was author of Miers 1826 which was in the Beagle library and referred to several times by Darwin (see Herbert 1995).

Darwin noted the date of 1 April on p. 164a, forgetting that March has 31 days. The section continued with a rapidly growing list of specimens as he visited some of the mines and pages were filled with extraordinarily detailed descriptions. At something like 200 words per page, these are possibly the most densely written pages in the field notebooks. Darwin was now at the easternmost extremity of his second published section. Herbert 2007, p. 317, reproduces a page from Darwin's geological diary which is derived from these pages (DAR36.508).

On the real 1 April, p. 178a, Darwin discovered the fossil forest at Agua del Zoro [Agua de La Zorra]: 'looking for silicified wood found in broken escarpment of green sandstone 11 silicified trees….' standing about 20º to the vertical. Darwin was immensely proud of this discovery which he reported in detail to Henslow in a letter dated 18 April 1835 (Correspondence 1, p. 442). This is one of Darwin's discoveries reported in the letters which Henslow decided to abstract and read to the Cambridge Philosophical Society on 16 November 1835, the printed pamphlet containing the abstracts constituting Darwin's first scientific publication from the voyage. (Darwin 1835) Henslow's action took Darwin completely by surprise when he found out about it while in the Atlantic in 1836, but was very important in preparing the scientific community to receive Darwin as a respected geologist when he returned to Britain in 1836.

Sedgwick also read the letters to The Geological Society two days after Henslow's reading, and this event was singled out by Charles Lyell in his Presidential Address to that august body in February 1836. Lyell realized that Darwin was going to be a great asset to him as a rare convert to his own gradualist principles.

In Journal of researches, p. 406, Darwin states that Robert Brown (1773-1858) identified the fossil trees as coniferous, and explained at great length how he believed the trees proved a complex history of uplift and re-emergence of the Andes. The age of the trees is now known to be late Triassic (about 245 million years old) and Darwin's discovery at this classic locality was commemorated in 1959 by the erection of a monument at the site (Morton 1995).

There follow many pages describing the traverse over the Uspallata range until on p. 188a Darwin entered the 'grand valley of Cordilleras' with 'Ostriches, Tuco Tuco, Pichy Paluda'. The landscape was 'extremely sterile'. On p. 189a he was told to beware the dangerous passes and to 'carry thick Worsted stockings'. On 3 April he was at the 'Paramillo', p. 190a, which is the Paramillo de Las Cuevas, one of the late eighteenth-century refuges on the Argentine side of the border where Darwin slept one night. See Morton 1995, p. 193 and fig. 7. By p. 196a Darwin was near the Puentes del Inca [Puenta del Inca], the famous, but in Darwin's view overrated, 'Inca's Bridge' or natural mineral archway over the river. Morton 1995, p. 193, fig. 6, provides a photograph.

Darwin recorded the Puenta del Inca section in great detail and on 6 [actually 5] April. On p. 201a he sketched the bridge itself, showing the 'crust of stratified shingle, cemented together by the deposits of the neighbouring hot springs' (Journal of researches, p. 409). This diagram was then copied into the margin of his Beagle diary, p. 319. The bridge is today a significant tourist attraction just south of the highway from Mendoza to Valparaiso, just east of the Argentine-Chile border.

Darwin's magnificent section through the mountains at this point, which forms the left central part of his published section 2, is illustrated by Morton 1995 who calls it 'the most classic section of the High Andes.' For comparison with Darwin's section Morton provides the more recent sections of Schiller 1926 and Ramos 1985, with a wonderful photographic panorama of the mighty Aconcagua fold and thrust belt taken by Ramos in 1994 (Morton 1995, p. 192, figs. 4 and 5).

On p. 199a Darwin mentioned the 'hot springs (and much gaz)' which he later described in South America, pp. 189-90 footnote. There is also some general interest in the notebook around these pages, such as the Lion and the humming bird and other birds Darwin saw at the bridge, and the high altitude 'Indian huts', p. 201a, which he speculated in his Beagle diary, pp. 189-190, implied a deterioration in the climate since the Incas left. On p. 209a he noted the 'remarkable electricity' and the 'transparency of air'.

Darwin made an intriguing but rather cryptic comment on p. 210a: 'immense degradation a consequent talus striking feature arguments of length of world from deluge applicable in each part since sea retired' [italics added]. The remark may mean that older arguments about the length of the world since the time of the Biblical flood, by Darwin's time no longer literally accepted by geologists, were sometimes based on the thickness of diluvial deposits. Darwin, by working out how the mountains had risen from beneath the sea and been eroded into valleys filled with immense amounts of talus, could see that each small event in his long chain of causes was equal to the old biblical timescale.

As Darwin made the gradual descent back to St Jago he noticed the cacti, p. 211a. He spent all of 7 April, p. 214a, searching for a mule, and on the next page he noted a 'Big Rat' in a 'high tree'.

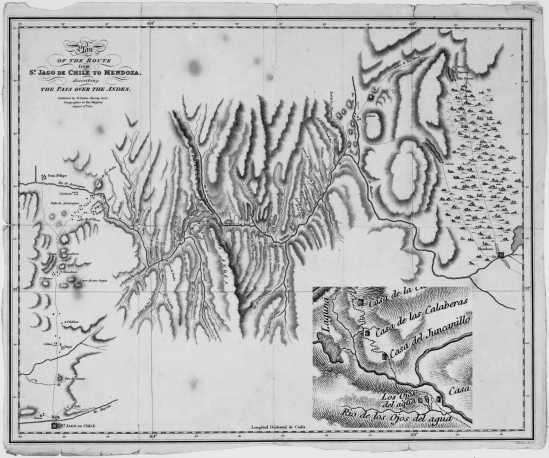

'Plan of the route from St Jago de Chile to Mendoza, describing the pass over the Andes'. Map from Darwin's collection and possibly carried with him in his 1835 traverse of the Andes. St Jago (i.e. Santiago) is at bottom left, Mendoza at far right. Published by W. Faden, London, 1823. A detail panel has been added on the lower right. (CUL-DAR 44.12).

Suddenly on p. 216a Darwin made a precise literature reference in ink, showing that he was back at St Jago, probably at Alexander Caldcleugh's house, and there is an outpouring of place names, dates and references to follow up. Then what must surely be a retrospective entry: 'all this time to Valparaiso not quite well saw nothing enjoyed nothing', p. 218a. On 15 April he 'started for Valparaiso – dead means [sic] heads on the poles', pp. 218-9a.

Finally, around 20 April, Darwin was back at the house of his old Shrewsbury School friend Richard Corfield (1811-1887) in Valparaiso. Corfield had looked after Darwin there when he was very ill, perhaps with typhoid, in 1834 (see introduction to the Santiago notebook). The last notes on p. 232a seem to be payments to Mariano Gonzales, Darwin's guide in Chile, '6 dollars' and to Covington 'on account 8 dollars'.

We have already noted that the entries in ink on p. 233a seem to be dated 12 March 1835, so appear to predate the previous page.

Thus ended the longest continuous sequence of notes in any of the field notebooks, in which Darwin recorded the first complete traverse by a geologist across the longest mountain range in the world. These notes were eventually published in greatly expanded form in his South America and remain to this day a classic account in the history of geology. They also provided Darwin with the raw material for his great theoretical paper linking earthquakes, volcanoes and the vertical movements of the earth's crust, and, perhaps most importantly, convinced him of the almost unimaginable immensity of geological time. (Darwin 1838) As he stated emphatically at the end of his account of the Portillo Range:

What a history of changes of level, and of wear and tear, all since the age of the latter Secondary formations of Europe, does the structure of this one great mountain-chain reveal! (South America, p. 187).

Gordon Chancellor and John van Wyhe

August 2008

'Buenos Ayres. St. Fe and Parana. — Cordillera of Chile' (9-11.1833; 3-4.1835). Beagle field notebook. Text EH1.13

1 The notebooks which fill the gap in use of the St. Fe are as follows: firstly Banda Oriental which followed on from the 1833 part of St. Fe directly with expedition 4; then Buenos Ayres very briefly, then Port Desire, B. Blanca briefly, Banda Oriental, B. Blanca, Valparaiso, Santiago, Port Desire, Galapagos, then some loose sheets of paper which are now in DAR35, then the Santiago Notebook before the St. Fe Notebook was used again in 1835, albeit with another brief interruption from Galapagos. This sequence is based only on datable passages and may not be the complete sequence. After the St. Fe Notebook was finally put aside, the Coquimbo Notebook took over for field notes, with the Santiago Notebook used for theory.

2 There is today on display in the lobby of the Exhibition Road entrance to London's Natural History Museum a cast of a complete skeleton of Toxodon platensis, the original of which is in the La Plata Museum which is almost certainly the museum visited by Darwin. The skeleton was not one of the 'petrifactions' he would have been able to see in 1833, as it was only excavated later in the century.

3 The Andes stretch some 9000km down the western side of South America and are the result of the subduction beneath the South American Plate of the Nazca Plate (and south of 49º of the Antarctic Plate). They are the result of tectonic plates, one oceanic, the other continental, moving in opposing directions.

Detailed structure varies considerably from north to south, but generally the Andes are at their widest and highest in the north of the continent, with an average elevation of 3.5 to 4km. Tectonic evolution of the Andes began in Palaeozoic times with accretion but accelerated in Mesozoic times with the opening of the Atlantic.

A section across the Andes which would include the sections examined by Darwin in the St. Fe Notebook (and to a lesser extent in the Copiapo and Valparaiso Notebooks) is broadly comparable to the rest of the chain, but differs in many details from sections to the north and south.

From the Ocean eastwards there is the Peru-Chile Trench, then the Coastal Range, built largely of granite batholiths, beneath which the Nazca Plate is melting. These are the areas where most major earthquakes would be expected, a point noted by Darwin (South America, p. 185 footnote). There is then a well-defined Central Valley where Santiago is situated.

About one third the way into the section are the Cordillera Principal (Darwin's Peuquenes Range, which he sometimes called the 'central range' (South America, p. 180). The Chile-Argentine border runs down the middle of this range which has some of the great peaks such as Aconcagua, at c. 6,960m the highest mountain in the world outside the Himalayas. Darwin described the porphyries, granites, slates, sandstones and Mesozoic fossils of this range.

FitzRoy determined the height of Aconcagua and was able to prove that it was higher than Chimborazo in Ecuador. Aconcagua was one of the chain of volcanoes that Darwin reported to have suddenly and simultaneously erupted on 20 January 1835 (Darwin 1838).

The middle of the section are the Cordillera Frontal (Darwin's Portillo or Eastern Range), which can perhaps be considered as a southern extension of the Altiplano plateau consisting mainly of granites, andesites and other igneous rocks partly thrust eastwards over the South American Shield. Darwin reported conglomerates in this range derived from the Cordillera Principal, implying that the latter had been uplifted first.

Next there is the fold and thrust belt of the Precordillera (Darwin's Cumbre and Uspallata Ranges) with a granite core and many complex structures. There are sections of spectacularly coloured Mesozoic and Tertiary sedimentary and volcanic rocks, such as the Puente del Inca section mentioned by Morton 1995, and the complex stories of crustal mobility exemplified by the Agua de La Zorra trees.

Darwin returned westward at this point but if he had continued east through the section he might have encountered some of the lower Pampean Ranges, a series of basement uplifts.

RN9